- 1Section of Neonatology and Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, Department of Biomedical Science and Human Oncology, “Aldo Moro” University of Bari, Bari, Italy

- 2Pediatrics Department, Umberto I Hospital, Sapienza University, Rome, Italy

- 3Department of Pediatric, Ospedale “F. Del Ponte”, University of Insubria, Varese, Italy

- 4Pediatric Unit, Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences, University “Magna Graecia” of Catanzaro, Catanzaro, Italy

- 5Department of Interdisciplinary Medicine, “Aldo Moro” University of Bari, Bari, Italy

Background: Allergic diseases are a major public health burden worldwide. Evidence suggests that early nutrition might play a key role in the future development of allergies and the use of hydrolyzed protein formulas have been proposed to prevent allergic disease, mainly in term infants with risk factors.

Aim: To evaluate the preventive effect of a hydrolyzed protein formula vs. an intact protein formula on allergy development in preterm infants with or without risk factors.

Methods: We performed a 3-year follow-up study of a previous triple-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial. Evidence of atopic dermatitis, asthma and IgE-mediated food allergies were evaluated according to a validated parental questionnaire (Comprehensive Early Childhood Allergy Questionnaire). Food sensitization was also investigated by skin prick test at 3 years of chronological age.

Results: Of the 30 subjects in the intact protein formula group and 30 in the extensively hydrolyzed formula group, respectively 18 and 16 completed the 3-year follow-up and entered the final analysis. No group differences in the incidence of atopic dermatitis, asthma, IgE-mediated food allergies, and food sensitization were found.

Conclusion: Despite the small number of cases, extensively hydrolyzed protein formula seems to be ineffective in allergic diseases prevention in preterm neonates. Further adequately powered, randomized controlled trials evaluating hydrolyzed protein formula administration to prevent allergic diseases in preterm neonates are needed.

Introduction

Allergic rhinitis (AR), asthma, eczema, and food allergy are some of the most common pediatric chronic conditions worldwide and have a major impact on children health and quality of life (1).

Allergic diseases are genetically determined but also influenced by several factors such as environmental pollution, smoke, aeroallergens, and early feeding pattern (2). To date, a tailored approach seems to be the best strategy to hamper the so-called “atopic march” (3). In this perspective, standard operative procedures to prevent allergy have become a priority in managing public health and infant feeding is considered the most important modifiable factor that can be targeted (4).

World Health Organization (WHO) states that breast milk is the best source of nutrients for both term and preterm infants, and there is some evidence of its role in decreasing the risk of allergy development (5, 6). Unfortunately human milk is not always available and the challenge for many pediatric societies remains to draw up standardized and definitive guidelines to recommend the most effective infant formula in allergy prevention (7).

More recently, hydrolyzed formulas (HF) have been proposed for prevention of allergy and many studies suggested the use of these formulas in formula-fed infants with a family history of allergic diseases (8).

The main differences between each HF are the degree and method of hydrolysis, with consequent different immunological, clinical, and nutritional effects: extensively hydrolyzed formulas (eHF) contain mostly peptides ≤3 kD, while partially hydrolyzed formulas (pHF) ≤5 kD (9).

Despite preterm infants could be at higher risk for food allergy because of their increased intestinal permeability and their possible higher food antigen uptake, they do not show higher incidence of allergic diseases when compared to term infants (10, 11).

At the moment, human milk represents the best source of nutrients for preterm infants for its bioactive effect (12). On the contrary, there is limited evidence regarding nutritional preventive action against the future development of allergies in this vulnerable population (13). This paper describes the follow-up results of a previous published triple-blind, controlled, clinical trial, in preterm neonates fed with either intact protein formula or extensively hydrolyzed formula (14, 15).

Methods

Study design, inclusion and exclusion criteria, randomization and study group allocation, and feeding protocol are thoroughly described in the previous articles (14, 15).

In brief, all mothers were encouraged to exclusively breastfeed and to have an unrestricted diet during lactation. At birth all eligible preterm neonates, regardless family history of allergy, were randomized to receive one of two different blinded formulas: either preterm intact protein formula [IPF: marketed Enfamil® Premature, Mead Johnson Nutrition (MJN), Evansville, IN, USA] or infant extensively hydrolyzed protein formula (eHF: marketed Pregestimil®, MJN, Evansville, IN, USA). When breastfeeding was not sufficient, one of the two formulas, according to randomization, was given for 2 weeks. The research protocol was approved by the ethical committee of “Azienda Ospedaliero—Universitaria Consorziale Policlinico” (number 4122—date 17/2/2016). Parents or legally authorized representatives provided written informed consent prior to enrolment.

To all participants, complementary feeding was recommended after the age of 4 months, without restriction of possible allergenic foods and with intact protein milk formulas in case of insufficient breast milk. To compare the allergy-preventive effect of eHF vs. IPF, all infants were followed-up 6-monthly until 3 years of chronological age, for evidence of atopic dermatitis, asthma, and IgE-mediated food allergies according to a validated parental questionnaire (Comprehensive Early Childhood Allergy Questionnaire) (16). Food sensitization, based on positive skin prick tests at 3 years of chronological age, was also investigated.

Statistical Analysis

Participant characteristics at enrolment were compared by Student t-test (gestational age and birth weight) or chi-square test (gender, birth type, cesarean section). Outcomes such as evidence of atopic dermatitis, asthma, and IgE-mediated food allergies were analyzed by chi-square test. All participants who met study entrance criteria and completed the 3 years follow-up period were evaluated. A subset analysis was carried out to assess participants at high-risk for allergy. High-risk infants were defined as having at least one parent or a single first-degree relative with a history of allergic disease. All tests were conducted at α = 0.05. All analyses were conducted using IBM® SPSS® Statistics 23.

Results

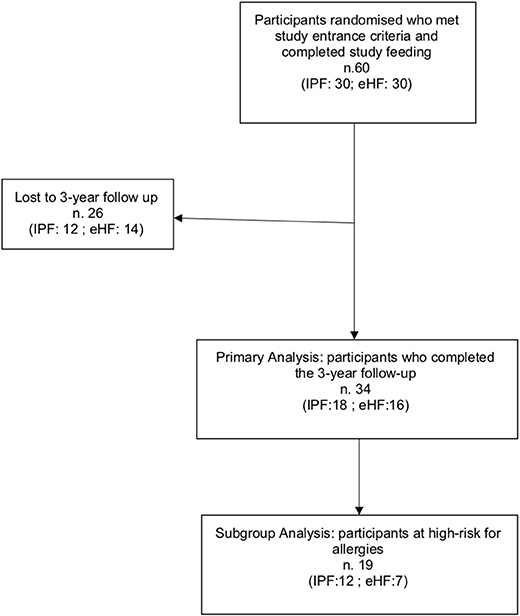

A total of 34/60 (56.6%) participants completed the 3-year follow-up study (IPF: 18; eHF: 16) and were included in the primary analysis. Dropouts occurred in 26 children due to protocol violation (3 patients) and voluntary withdrawal by parents during the follow-up period (23 patient) (Figure 1).

A subset analysis among infants at high risk for allergy included 19 participants: IPF n = 12 (66.7%); eHF n = 7 (43.8%); p = 0.17. Study flow chart is shown in Figure 1.

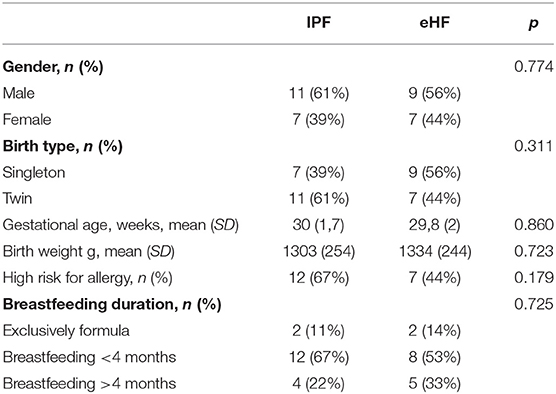

Infant characteristics at 3 years of chronological age were similar between groups (Table 1).

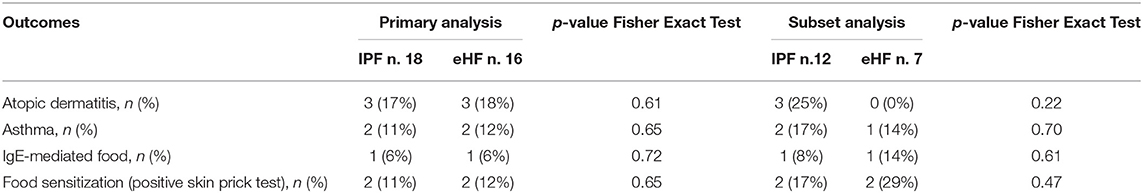

No difference in incidence of atopic dermatitis, asthma, IgE-mediated food allergies and food sensitization (positive skin prick test) were detected (primary or subset analysis) between groups (Table 2).

Discussion

The results of our study indicated that eHFs did not provide any preventive effects of allergy in preterm infants. Despite the low number of patients and the inadequate sample size, our findings are in keeping with the most recent meta-analysis regarding HF effect on allergy prevention in term neonates. In 2015, Boyle et al. found no consistent evidence to support the use of HF formula for reducing risk of allergic diseases (17). Similarly, Osborn et al. in a 2018 Cochrane found no difference in allergic diseases such as asthma, eczema, rhinitis, and food allergy in infants fed with a HF compared to IPF (18).

Only another randomized, double-blind study was conducted in high-risk preterm infants by Szajewska et al. (19). They failed to demonstrate a decrease in the incidence of allergic diseases, yet highlighted only a preventive effect of eHF on atopic dermatitis (AD) during a short follow-up of 12 months.

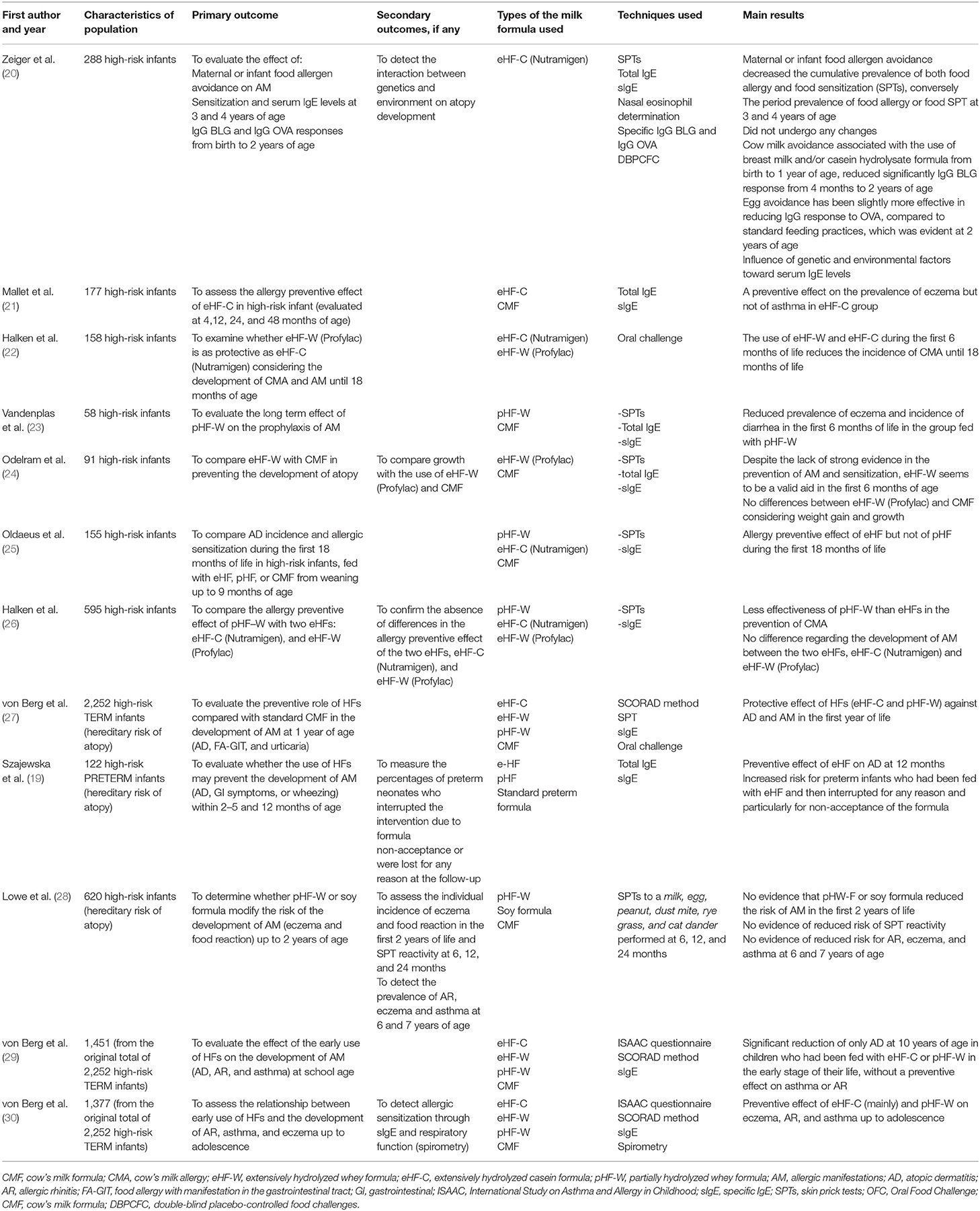

Conversely, several studies have been conducted in the last decades to investigate the preventive role of HFs on allergy development in term infants (Table 3).

A preventive effect of eHF both on food allergy and sensitization was first outlined in 1992, in the RCT conducted by Zeiger et al. on 288 high-risk infants (20).

This result, despite the lack of strong evidence, was later confirmed by Odelram et al. (24) and Oldaeus et al. (25). Mallet et al. in their study on 177 high-risk infants found a preventive effect on eczema linked to the early use of eHF, without any effect on asthma (21).

Similar results on eczema were found by Vandenplas et al., in a RCT on 58 high-risk infants (23).

Another RCT on 158 high-risk infants was conducted by Halken et al., who found a reduction of CMA in the first 6 months of life associated to the early use of eHFs (whey or casein) (22).

Subsequently these results were confirmed by the same authors in a larger study on 595 high-risk infants randomized to receive eHF-W, eHF-C, or pHF (26).

The German Infant Nutritional Intervention (GINI) study is to date the largest, spontaneous, quasi-randomized trial in which 2,252 children (with a family history of allergic diseases) were randomized to receive extensively hydrolyzed casein formula (eHF-C), extensively hydrolyzed whey formula (eHF-W), partially hydrolyzed whey formula (pHF-W), or standard cow's milk formula, in order to evaluate the possible preventive role of these formulas in the development of allergic diseases during a long term follow-up (27, 29–32). They found a protective effect of eHF-C and pHF-W against AD at 1 year follow-up and a significant reduction of AD at 7–10 years of age in children. However, no preventive effect against asthma or AR was shown. These results were confirmed in the 15-year follow-up study, where the authors reported also fewer diagnoses of AR and asthma in those children fed with hydrolysates (mainly eHF-C) in their early stages of life, as if the preventive effects of HF on these two pathologies had occurred later in time. Throughout the follow-up period eHF-W did not show any preventive effects toward allergic diseases and none of the HF had influence on IgE sensitization.

Differently from GINI study, the Melbourne Atopic Cohort Study, conducted on 620 high-risk infants randomized to pHF-W, soy formula or cow's milk formula, showed neither significant difference in allergic outcomes (eczema and food reactions) in the first 2 years of life nor evidence of reduced risk of SPT reactivity and of lower risk for AR, eczema and asthma up to 6–7 years of age (28).

Furthermore, in an observational population-based study, Goldsmith et al. examined the possible association between the development of food allergy at 1 year of age and either duration of exclusive breastfeeding or use of pHF (33). They found that the incidence of food allergy was not reduced by either the duration of exclusive breastfeeding or by the use of pHF, suggesting that allergen avoidance may not be helpful in allergy prevention.

Pooling data on HF in meta-analyses is problematic due to the heterogeneity of HF products and the different sources of proteins, hence different HF should not be considered equivalent. For this reason, Szajewska et al. conducted a meta-analysis taking into consideration exclusively studies using a unique 100%-whey pHF. They found a preventive effect against all allergic diseases and eczema (34). Based on all data from the literature, use of pHF-W formula has been considered safe in healthy term neonates (35, 36).

At present, the conclusions of guidelines and meta-analysis on the role of HF for prevention of allergic diseases differ in term of recommendations, outcomes, and target population. According to some pediatric Societies the use of pHF is still indicated in infants at high risk of allergy, when mother's milk is not available or is insufficient (37, 38). Differently, other Societies, based on emerging evidence, changed their previous recommendations and no longer proposed HF for prevention of allergic diseases (39–41).

The aim of this paper was to analyse the effect of HF on allergy prevention in preterm infants using follow-up data of a previous randomized, triple-blind, placebo-controlled study. To our knowledge, this is the first long-term follow-up paper concerning allergy prevention with HF in preterm infants. We acknowledge a possible limitation of our literature search due to the search restriction for preterm infants. In fact, using Medical Subject Headings-Terms for preterm infants, we could have missed studies in which subgroup analysis of preterm infants have been carried out, but not mentioned in the title or abstract. However, in our view, publication bias could be negligible. The main limitations of the present study can be considered the underpowered number of preterm enrolled, the short period of eHF administration, the drop-out rate and the lack of quantitative diagnostic methods used to diagnose allergy other than a validate questionnaire and SPT.

To sum up, further well-designed large studies in preterm infants should be conducted to address the preventive effects of HF for allergic diseases and the nutritional non-inferiority of preterm HF compared to modern preterm IPF in these vulnerable population. Moreover, data on long term safety of HF in preterm infants and cost/benefit ratio analysis are needed.

Evidences of hypersensitivity have been described also as predisposing factor in patients with functional gastrointestinal diseases (42), whose high prevalence have been recently found in preterm newborns (43). Despite self-limited diseases, a preventive intervention for FGIDs, especially for high-risk population, might have important clinical, and socioeconomical effects (44, 45). HFs have been investigated as dietary modification for management of these conditions with inconsistent evidences, despite some authors suggested a decreased incidence in infants fed with pHF (46, 47).

Finally, bio-effective agents such as probiotic have been recently added to HF to enhance their putative role in allergic disease prevention (48) and should be evaluated since preterm infants could be considered a strategy population for their well-known dysbiosis-related conditions (49, 50).

Conclusion

To date many rigorous systematic reviews and meta-analyses evaluating term infants concluded that evidence is not robust to support the use of HF to prevent atopic diseases. Our data did not show any allergy preventive effect of eHF in a small cohort of preterm infants and highlighted the need of further large studies to better clarify the possible role of HF for allergy disease prevention in this population.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Policlinico di Bari Ethics Committee. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants' legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

MB conceptualized and designed the study. MT and NLae assessed study participants and collected study data. MF performed statistical analyses. AD interpreted data and drafted the initial manuscript. GB and AZ performed literature search. MC, LP, SS, and RP revised the manuscript. NLaf coordinated and supervised all activities. All authors contributed to the intellectual content, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and approved the final version. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that this study received funding from Mead Johnson Nutrition in order to independently enroll infants and coordinate the original study. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article, or the decision to submit it for publication.

Abbreviations

AD, atopic dermatitis; AR, Allergic rhinitis; CM, Cow's milk; CMA, Cow's milk allergy; eHF-C, extensively hydrolyzed casein formula; eHF, extensively hydrolyzed formula; FGIDs, functional gastrointestinal diseases; HF, hydrolyzed formula; HM, human milk; IPF, intact protein formula; pHF-W, partially hydrolyzed whey formula; pHF, partially hydrolyzed formula; RCT, randomized controlled trials; SPT, skin prick test; VLBW, very low birth weight; WHO, World Health Organization.

References

1. Asher MI, Montefort S, Björkstén B, Lai CK, Strachan DP, Weiland SK, et al. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC Phases One and Three repeat multi country cross-sectional surveys. Lancet. (2006) 368:733–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69283-0

2. Halken S. Prevention of allergic disease in childhood: clinical and epidemiological aspects of primary and secondary allergy prevention. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. (2004) 15:9–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2004.0148b.x

3. Mastrorilli C, Caffarelli C, Hoffmann-Sommergruber K. Food allergy and atopic dermatitis: prediction, progression, and prevention. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. (2017) 28:831–40. doi: 10.1111/pai.12831

4. D'Auria E, Mameli C, Piras C, Cococcioni L, Urbani A, Zuccotti G, et al. Precision medicine in cow's milk allergy: proteomics perspectives from allergens to patients. J Proteomics. (2018) 188:173–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2018.01.018

5. Järvinen KM, Martin H, Oyoshi MK. Immunomodulatory effects of breast milk on food allergy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. (2019) 123:133–43. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2019.04.022

6. Baldassarre ME, Bellantuono L, Mastromarino P, Miccheli A, Fanelli M, Laforgia N. Gut and breast milk microbiota and their role in the development of the immune function. Curr Pediatr Rep. (2014) 2:218–26. doi: 10.1007/s40124-014-0051-y

7. D'Auria E, Abrahams M, Zuccotti G, Venter C. Personalized nutrition approach in food allergy: is it prime time yet? Nutrients. (2019) 11:359. doi: 10.3390/nu11020359

8. Cabana MD. The role of hydrolyzed formula in allergy prevention. Ann Nutr Metab. (2017) 70:38–45. doi: 10.1159/000460269

9. Salvatore S, Vandenplas Y. Hydrolyzed proteins in allergy. Nestle Nutr Inst Workshop Ser. (2016) 86:11–27. doi: 10.1159/000442699

10. Indrio F, Riezzo G, Cavallo L, Di Mauro A, Francavilla R. Physiological basis of food intolerance in VLBW. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. (2011) 24(Suppl. 1):64–6. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2011.607583

11. Liem JJ, Kozyrskyj AL, Huq SI, Becker AB. The risk of developing food allergy in premature or low-birth-weight children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2007) 119:1203–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.12.671

12. LoÅNnnerdal B. Bioactive proteins in human milk-potential benefits for preterm infants. Clin Perinatol. (2017) 44:179–91. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2016.11.013

13. Zachariassen G, Faerk J, Esberg BH, Fenger-Gron J, Mortensen S, Christesen HT, et al. Allergic diseases among very preterm infants according to nutrition after hospital discharge. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. (2011) 22:515–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2010.01102.x

14. Baldassarre ME, Di Mauro A, Montagna O, Fanelli M, Capozza M, Wampler JL, et al. Faster gastric emptying is unrelated to feeding success in preterm infants: randomized controlled trial. Nutrients. (2019) 11:1670. doi: 10.3390/nu11071670

15. Baldassarre ME, Di Mauro A, Fanelli M, Capozza M, Wampler JL, Cooper T, et al. Shorter time to full preterm feeding using intact protein formula: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. (2019) 16:2911. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16162911

16. Minasyan A, Babajanyan A, Campbell D, Nanan R. Validation of a comprehensive early childhood allergy questionnaire. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. (2015) 26:522–9. doi: 10.1111/pai.12415

17. Boyle RJ, Ierodiakonou D, Khan T, Chivinge J, Robinson Z, Geoghegan N, et al. Hydrolysed formula and risk of allergic or autoimmune disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. (2016) 352:i974. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i974

18. Osborn DA, Sinn JK, Jones LJ. Infant formulas containing hydrolysed protein for prevention of allergic disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2018) 10:CD003664. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003664.pub6

19. Szajewska H, Mrukowicz JZ, Stoinska B, Prochowska A. Extensively and partially hydrolysed preterm formulas in the prevention of allergic diseases in preterm infants: a randomized, double-blind trial. Acta Paediatr Oslo Nor. (1992) (2004) 93:1159–65.

20. Zeiger RS, Heller S, Sampson HA. Genetic and environmental factors affecting the development of atopy through age 4 in children of atopic parents: a prospective randomized controlled study of food allergen avoidance. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. (1992) 3:110–27.

21. Mallet E, Henocq A. Long-term prevention of allergic diseases by using protein hydrolysate formula in at-risk infants. J Pediatrics. (1992) S95–100.

22. Halken S, Høst A, Hansen LG, Østerballe O. Preventive effect of feeding high-risk infants a casein hydrolysate formula or an ultrafiltrated whey hydrolysate formula. A prospective, randomized, comparative clinical study. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. (1993) 4:173–81.

23. Vandenplas Y, Hauser B, Van den Borre C. The long-term effect of a partial whey hydrolysate formula on the prophylaxis of atopic disease. Eur J Pediatr. (1995) 154:488–9.

24. Odelram H, Vanto T, Jacobsen L, Kjellman NI. Whey hydrolysate compared with cow's milk based formula for weaning at about 6 months of age in high allergy-risk infants: effects on atopic disease and sensitization. Allergy. (1996) 51:192–5.

25. Oldaeus G, Anjou K, Björkstén B, Moran JR, Kjellman NI. Extensively and partially hydrolysed infant formulas for allergy prophylaxis. Arch Dis Child. (1997) 77:4–1.

26. Halken S, Hansen KS, Jacobsen HP, Estmann A, Christensen AE, Hansen LG, et al. Comparison of a partially hydrolyzed infant formula with two extensively hydrolyzed formulas for allergy prevention: a prospective, randomized study. Pediatric Allergy Immunol. (2000) 11:149–61. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3038.2000.00081.x

27. von Berg A, Koletzko S, Grübl A, Filipiak-Pittroff B, Wichmann HE, Bauer CP, et al. The effect of hydrolyzed cow's milk formula for allergy prevention in the first year of life: the German Infant Nutritional Intervention Study, a randomized double-blind trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2003) 111:533–40. doi: 10.1067/mai.2003.101

28. Lowe AJ, Hosking CS, Bennett CM, Allen KJ, Axelrad C, Carlin JB, et al. Effect of a partially hydrolyzed whey infant formula at weaning on risk of allergic disease in high-risk children: a randomized controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2011) 128:360–5.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.05.006

29. von Berg A, Filipiak-Pittroff B, KraÅNmer U, Hoffmann B, Link E, Beckmann C, et al. Allergies in high-risk schoolchildren after early intervention with cow's milk protein hydrolysates: 10-year results from the German Infant Nutritional Intervention (GINI) study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2013) 131:1565–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.01.006

30. von Berg A, Filipiak-Pittroff B, Schulz H, Hoffmann U, Link E, Sussmann M, et al. Allergic manifestation 15 years after early intervention with hydrolyzed formulas - the GINI Study. Allergy. (2016) 71:210–9. doi: 10.1111/all.12790

31. von Berg A, Koletzko S, Filipiak-Pittroff B, Laubereau B, Grübl A, Wichmann H-E, et al. Certain hydrolyzed formulas reduce the incidence of atopic dermatitis but not that of asthma: three-year results of the German Infant Nutritional Intervention Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2007) 119:718–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.11.017

32. von Berg A, Filipiak-Pittroff B, KraÅNmer U, Link E, Bollrath C, Brockow I, et al. Preventive effect of hydrolyzed infant formulas persists until age 6 years: long-term results from the German Infant Nutritional Intervention Study (GINI). J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2008) 121:1442–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.04.021

33. Goldsmith AJ, Koplin JJ, Lowe AJ, Tang M, Matheson M, Robinson M, et al. Formula and breast feeding in infant food allergy: a population-based study. J Paediatr Child Health. (2016) 52:377–84. doi: 10.1111/jpc.13109

34. Szajewska H, Horvath A. A partially hydrolyzed 100% whey formula and the risk of eczema and any allergy: an updated meta-analysis. World Allergy Organ J. (2017) 10:27. doi: 10.1186/s40413-017-0158-z

35. Vandenplas Y, Alarcon P, Fleischer D, Hernell O, Kolacek S, Laignelet H, et al. Should partial hydrolysates be used as starter infant formula? A working group consensus. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. (2016) 62:22–35. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001014

36. Vandenplas Y, Latiff AHA, Fleischer DM, Gutiérrez-Castrellón P, Miqdady MS, Smith PK, et al. Partially hydrolyzed formula in non-exclusively breastfed infants: a systematic review and expert consensus. Nutrition. (2019) 57:268–74. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2018.05.018

37. Muraro A, Halken S, Arshad SH, Beyer K, Dubois AEJ, Du Toit G, et al. EAACI food allergy and anaphylaxis guidelines. Primary prevention of food allergy. Allergy. (2014) 69:590–601. doi: 10.1111/all.12398

38. Koletzko S, Niggemann B, Arato A, Dias JA, Heuschkel R, Husby S, et al. Diagnostic approach and management of cow's-milk protein allergy in infants and children: ESPGHAN GI Committee practical guidelines. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. (2012) 55:221–9. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31825c9482

39. Greer FR Sicherer SH Burks AW Committee on Nutrition; Section on Allergy and Immunology. The effects of early nutritional interventions on the development of atopic disease in infants and children: the role of maternal dietary restriction, breastfeeding, hydrolyzed formulas, and timing of introduction of allergenic complementary foods. Pediatrics. (2019) 143:e20190281. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-0281

40. Joshi PA, Smith J, Vale S, Campbell DE. The Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy infant feeding for allergy prevention guidelines. Med J Aust. (2019) 210:89–93. doi: 10.5694/mja2.12102

41. di Mauro G, Bernardini R, Barberi S, Capuano A, Corerra A, De Angelis G, et al. Prevention of food and airway allergy: consensus of the Italian society of preventive and social pediatrics, the Italian society of pediatrics allergy and immunology, and italian society of pediatrics. World Allergy Organ J. (2016) 9:28. doi: 10.1186/s40413-016-0111-6

42. Pensabene L, Salvatore S, D'Auria E, Parisi F, Concolino D, Borrelli O, et al. Cow's milk protein allergy in infancy: a risk factor for functional gastrointestinal disorders in children? Nutrients. (2018) 10:1716. doi: 10.3390/nu10111716

43. Salvatore S, Baldassarre ME, Di Mauro A, Laforgia N, Tafuri S, Bianchi FP, et al. Neonatal antibiotics and prematurity are associated with an increased risk of functional gastrointestinal disorders in the first year of life. J Pediatr. (2019) 212:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.04.061

44. Indrio F, Di Mauro A, Riezzo G, Cavallo L, Francavilla R. Infantile colic, regurgitation, and constipation: an early traumatic insult in the development of functional gastrointestinal disorders in children? Eur J Pediatr. (2015) 174:841–2. doi: 10.1007/s00431-014-2467-3

45. Indrio F, Di Mauro A, Riezzo G, Panza R, Cavallo L, Francavilla R. Prevention of functional gastrointestinal disorders in neonates: clinical and socioeconomic impact. Benef Microbes. (2015) 6:195–8. doi: 10.3920/BM2014.0078

46. Gordon M, Biagioli E, Sorrenti M, Lingua G, Moja L, Banks S, et al. Dietary modifications for infantile colic. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2018) 10:CD011029. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011029.pub2

47. Vandenplas Y, Salvatore S. Infant formula with partially hydrolyzed proteins in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Nestle Nutr Inst Workshop Ser. (2016) 86:29–37. doi: 10.1159/000442723

48. Zuccotti G, Meneghin F, Aceti A, Barone G, Callegari ML, Di Mauro A, et al. Probiotics for prevention of atopic diseases in infants: systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy. (2015) 70:1356–71. doi: 10.1111/all.12700

49. Baldassarre ME, Palladino V, Amoruso A, Pindinelli S, Mastromarino P, Fanelli M, et al. Rationale of probiotic supplementation during pregnancy and neonatal period. Nutrients. (2018) 10:1693. doi: 10.3390/nu10111693

Keywords: preterm/full term infants, infant formula, hydrolyzed protein formula, hypersensitivity, allergy

Citation: Di Mauro A, Baldassarre ME, Brindisi G, Zicari AM, Tarantini M, Laera N, Capozza M, Panza R, Salvatore S, Pensabene L, Fanelli M and Laforgia N (2020) Hydrolyzed Protein Formula for Allergy Prevention in Preterm Infants: Follow-Up Analysis of a Randomized, Triple-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study. Front. Pediatr. 8:422. doi: 10.3389/fped.2020.00422

Received: 10 April 2020; Accepted: 18 June 2020;

Published: 30 July 2020.

Edited by:

Gianvincenzo Zuccotti, University of Milan, ItalyReviewed by:

Francesco Cresi, University of Turin, ItalyFlorence Campeotto, Hôpital Necker-Enfants Malades, France

Carlo Caffarelli, University of Parma, Italy

Copyright © 2020 Di Mauro, Baldassarre, Brindisi, Zicari, Tarantini, Laera, Capozza, Panza, Salvatore, Pensabene, Fanelli and Laforgia. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Maria Elisabetta Baldassarre, bWFyaWFlbGlzYWJldHRhLmJhbGRhc3NhcnJlQHVuaWJhLml0

Antonio Di Mauro1

Antonio Di Mauro1 Maria Elisabetta Baldassarre

Maria Elisabetta Baldassarre Giulia Brindisi

Giulia Brindisi Anna Maria Zicari

Anna Maria Zicari Nicla Laera

Nicla Laera Raffaella Panza

Raffaella Panza Silvia Salvatore

Silvia Salvatore Licia Pensabene

Licia Pensabene Margherita Fanelli

Margherita Fanelli Nicola Laforgia

Nicola Laforgia