Abstract

During communication, speakers commonly rotate their forearms so that their palms turn upward. Yet despite more than a century of observations of such palm-up gestures, their meanings and origins have proven difficult to pin down. We distinguish two gestures within the palm-up form family: the palm-up presentational and the palm-up epistemic. The latter is a term we introduce to refer to a variant of the palm-up that prototypically involves lateral separation of the hands. This gesture—our focus—is used in speaking communities around the world to express a recurring set of epistemic meanings, several of which seem quite distinct. More striking, a similar palm-up form is used to express the same set of meanings in many established sign languages and in emerging sign systems. Such observations present a two-part puzzle: the first part is how this set of seemingly distinct meanings for the palm-up epistemic are related, if indeed they are; the second is why the palm-up form is so widely used to express just this set of meanings. We propose a network connecting the different attested meanings of the palm-up epistemic, with a kernel meaning of absence of knowledge, and discuss how this proposal could be evaluated through additional developmental, corpus-based, and experimental research. We then assess two contrasting accounts of the connection between the palm-up form and this proposed meaning network, and consider implications for our understanding of the palm-up form family more generally. By addressing the palm-up puzzle, we aim, not only to illuminate a widespread form found in gesture and sign, but also to provide insights into fundamental questions about visual-bodily communication: where communicative forms come from, how they take on new meanings, and how they become integrated into language in signing communities.

Introduction

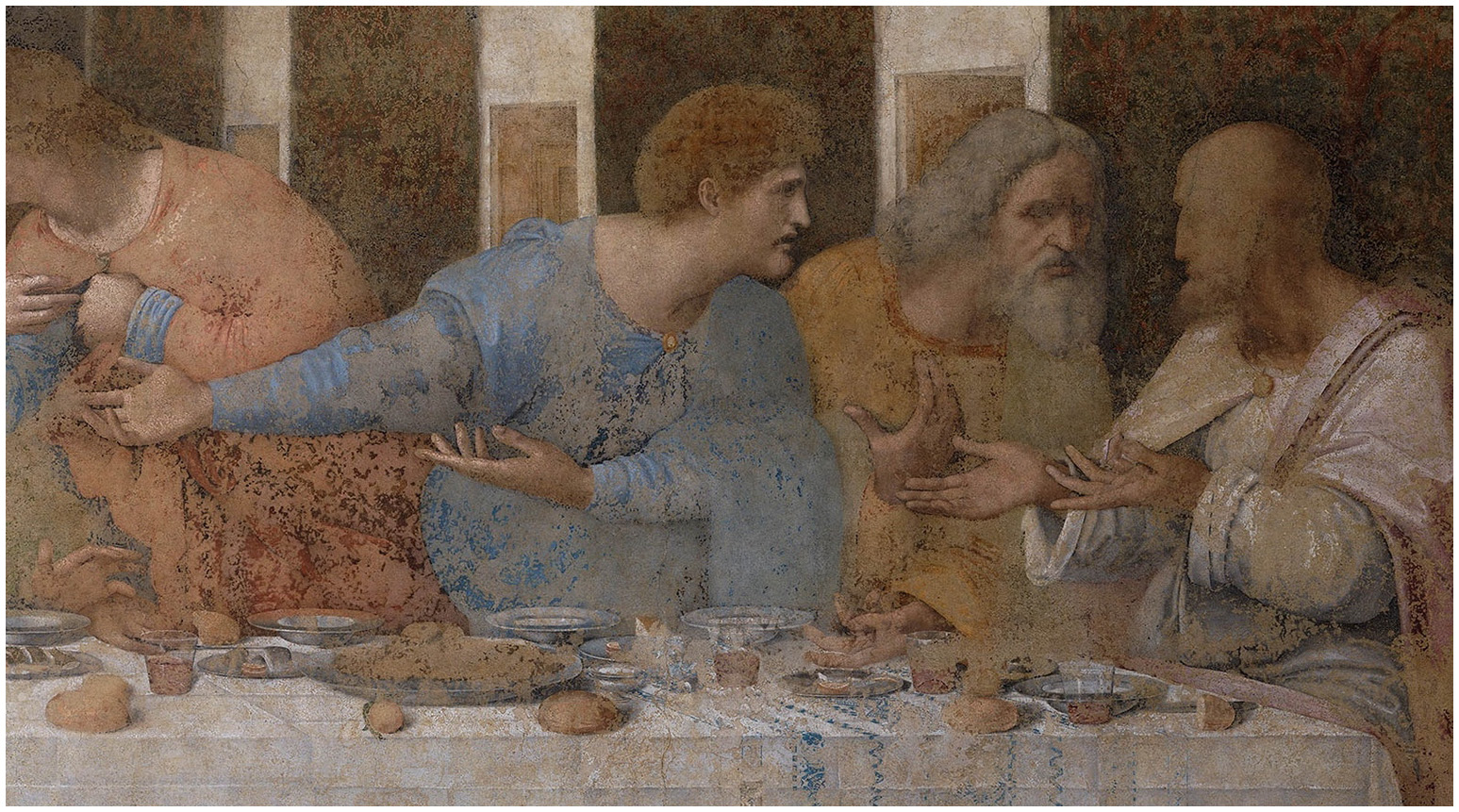

Centuries ago in Italy, a keen observer took notes on a conversation unfolding nearby. He inventoried a number of movements and gestures. He writes, for example: “Another with arms spread open showing the palm, shrugs his shoulders up to his ears and makes a grimace of astonishment” (qtd. in Isaacson, 2017, p. 283). The observer was Leonardo da Vinci, and his careful observations of the role of the body in everyday communication—including observations of a deaf associate—informed his painting (Isaacson, 2017; see also Streeck, 2003). In The Last Supper, a panoramic buffet of gestural expression, Leonardo would capture the same gesture he described as “showing the palm.” The three apostles on the far right of the panel—Matthew, Thaddeus, and Simon—all produce some version of this form as they react to Jesus's announcement that there is a traitor in their midst (Figure 1). The meaning of these palm-up gestures is impossible to pin down with precision, of course, but, in broad strokes, it is hard to mistake: the three men are taken aback and trying to make sense of what has just happened. What? Who? Could it be? Across half a millennium and despite peeling paint, the gestures still convey meaning.

Figure 1

Detail from Leonardo da Vinci's The Last Supper, a mural from the late fifteenth century, showing three figures producing gestures with the palms turned up.

Palm-up gestures remain ubiquitous today, and yet their meanings are still difficult to pin down precisely; they are generally interpretable and yet confoundingly elusive, much as in Leonardo's rendering. The present paper shines a spotlight on this family of forms, exposing a puzzle of form and meaning that is bigger and thornier than previously appreciated. We are hardly the first to note the prominence of palm-ups in communication. Indeed, observations about the form stretch back to antiquity, and a growing number have been made in recent decades. Unfortunately, these observations have sometimes been made in mutual isolation from each other, often using different analytic frameworks and pursuing different ends. Work on palm-ups as used by speakers, for instance, has often been carried out independently from work on palm-ups as used by signers. An important goal of the present paper is to bridge these literatures and present a comprehensive synthesis of research on palm-ups in both spoken and signed communication. Another goal looms perhaps larger: shedding light on palm-up forms stands to shed light also on general questions about where bodily communicative forms come from, how they take on new meanings through processes of semantic and pragmatic extension, and how they become integrated into language in signing communities. That is, palm-ups—in all their ubiquity and multiplicity of meanings—present a critical case study for scholars of visual-bodily communication.

Part of what makes palm-ups a compelling phenomenon of study is their sheer pervasiveness. The largest study of the gestures accompanying spoken English to date, an analysis of 8000 gestures produced by 129 speakers, found that two gesture types involving the palm-up form together accounted for 24% of all gestures (Chu et al., 2013). Such ubiquity has also been reported in analyses of signed communication. A large-scale corpus study of British Sign Language (BSL) reports that the palm-up, glossed by the authors as a discourse marker meaning WELL, is the second most frequent sign (after the first-person pronoun) (Fenlon et al., 2014). A comparably sized corpus study also found the palm-up to be the second most frequent sign in the sign language of Australia (Auslan) (Johnston, 2012), as did a smaller corpus study of New Zealand Sign Language (NZSL) (McKee and Wallingford, 2011); and it was the third most frequent sign in a corpus study of Swedish Sign Language (SSL) (Börstell et al., 2016).

There is little reason to think the prominence of palm-up forms is a quirk of communication in Anglophone and European communities. As we review later, speakers from communities in Asia, Africa, South America, and elsewhere also produce this same form family—and one “family member” in particular—to express a number of meanings. Several of these meanings seem at first blush quite distinct from each other—sometimes even contradictory—and yet, intriguingly, the same cluster of meanings pops up in culture after culture. Moreover, signers from far-flung signing communities produce the palm-up form to express a similar cluster of meanings. Palm-ups are also used in emerging languages, including the so-called “shared” sign systems of villages with high rates of hereditary deafness (Nyst, 2012) and the idiosyncratic communication systems innovated by profoundly deaf people who grow up without access to conventional sign language, called homesigners (e.g., Franklin et al., 2011). These observations invite two preliminary points. First, if a community uses a single form to cover two or more meanings—and, if other communities also use a single form to cover the same meanings—these meanings are most likely related to each other. The task of the analyst—and the task we take up here—is to articulate these links. Second, if different communities use the very same form for a particular set of meanings, there is probably a motivated relationship between form and meaning, however obscure this motivation may be to the casual observer (for arguments of this type in sign, see Aronoff et al., 2005; Wilbur, 2010). The challenge for the analyst—and, again, the challenge we take up here—is to try to discern that motivation.

Our attempt to understand palm-ups thus engages long-standing questions about form and meaning common to the study of all communication—spoken, signed, or gestured. The “palm-up puzzle” of our title can be crystallized as having two parts. First, how are the seemingly distinct meanings of palm-ups related? And, second, why is the palm-up form used to express them? Adding to the difficulty of our task, there are complexities of interpretation that make the puzzle thornier than it first appears. Most critically, there is not one palm-up form but a family of forms, and whether this form family has important finer divisions within it remains contested. Moreover, palm-ups often co-occur with other bodily forms, including facial expressions, head shakes, and, notably, shoulder shrugs, as we discuss in detail later. Terminological profusion further complicates matters. Gestures exhibiting the palm-up form have been called “hand shrugs” (Johnson et al., 1975), “palm-revealing” gestures (Chu et al., 2013), “hand flips” (Ferré, 2011), “palm up open hand” (PUOH) gestures (Müller, 2004), the “open hand supine” gesture family (Kendon, 2004), and the “rotated palms” gesture family (Gawne, 2018) (see also Givens, 2016, p. 1–2). Gesture researchers have variously classified palm-ups as “emblems” (e.g., Johnson et al., 1975), “recurrent gestures” (Müller, 2017), “pragmatic gestures” (Kendon, 2004), “interactive gestures” (Bavelas et al., 1992), “metaphorics” (e.g., Parrill, 2008), and beyond. Sign researchers have described palm-ups as having both grammaticalized uses as a sign and uses as a co-sign gesture (McKee and Wallingford, 2011). When used as a sign, grammatical classification varies; some describe palm-up signs as discourse markers (Engberg-Pedersen, 2002), others as particles (Conlin et al., 2003). Palm-up forms have been described as serving a suite of functions—cohesive, modal, and interactive—all within individual sign languages (Engberg-Pedersen, 2002; McKee and Wallingford, 2011; Volk, 2017). There are also clear cases where frozen signs, such as interrogative markers and indefinites, incorporate the palm-up form (e.g., Zeshan, 2004). In short, in both gesture and sign, palm-ups exhibit wide diversity in form, puzzling multiplicity in meaning, and vexing variability in the terminology and frameworks used to characterize them.

Our plan for taking on the palm-up puzzle is as follows. We begin by collating existing observations about how palm-up forms are used by gesturers (next section) and by signers (following section). As will become clear, our focus is not on the entire family of palm-up forms, but on a particular gesture within the family that is widely used in both gesture and sign: what we call the palm-up epistemic gesture. This particular palm-up presents a puzzle all on its own, and we consider it in detail: we discuss the meanings that have been most widely associated with this gesture across speaking and signing communities, and we propose a meaning network to account for how these meanings are related to each other. Recognizing the provisional status of this proposal, we also discuss the types of new evidence that would be most useful in testing and refining it. Finally, before concluding, we evaluate two accounts of the ultimate origins of the palm-up epistemic gesture—that is, accounts of what motivates the use of this form for this set of meanings. Ultimately, by treating this particular palm-up gesture in detail, we aim to shed light on the meanings and origins of the entire palm-up form family.

Palm-ups in gesture

Preliminaries

Before cataloging observations about use of the palm-up form in gesture, it will be helpful to briefly introduce our perspective on gestural form and meaning. Here, we use the term “form” to refer to features of handshape and movement irrespective of meaning, and reserve “gesture” for particular conventional pairings of form and meaning (for discussion, see Cooperrider and Núñez, 2012). Take the “thumbs up”: speakers may produce a number of gestures involving a thumbs-up form, but the “thumbs-up gesture” refers to a conventional pairing of that form with a particular meaning. The form/gesture distinction is even more critical in light of the fact that conventional gestures, like language, sometimes exhibit cases of apparent “homonymy” in which the same form is associated with distinct meanings (for discussion, see Sherzer, 1973). As an illustration, consider two conventional gestures involving an extended index finger. On one occasion, a speaker may hold up this finger vertically to raise an objection; on another, the vertical finger may serve to ask an interlocutor to wait a second. These uses share a common form, but they have different meanings and motivations. In short, they are different gestures.

With this perspective in mind, we now turn to several sticking points in the palm-up literature. The first and biggest of these is the question of whether all forms that exhibit an upturned palm should be considered one inter-connected family of gestures, a family but with key divisions, or perhaps several distinct gestures related in form only. Researchers broadly agree that the family of palm-up forms is sprawling; they disagree on how the family should be divided or whether it should be. Kendon (2004, pp. 273–281), for instance, divides the family based on differences in motion pattern. One variant—the “palm lateral”—involves rotating the forearms so that the palms face upward and moving the hands apart. A second—the “palm presentation”—involves moving the upturned palm toward the listener, as if “presenting” something. Other authors have echoed such divisions. Chu et al. (2013), for example, distinguish between “palm-revealing gestures” (comparable to Kendon's “palm lateral”) and “conduit gestures” (comparable to his “palm presentation”). In motivating such a split, these researchers argue that formational features can generally (though not always) distinguish between these two variants, and that these variants express different kinds of meanings.

Other authors make no such divisions, seeing the palm-up as a large extended gesture family, a set of related forms paired with related meanings. For instance, Müller (2004) considers these formational variants together under a unified semantic theme, as we discuss later. Streeck (2009) would seem to similarly lump together uses, describing some uses that seem akin to Kendon's “palm presentation” and others akin to the “palm lateral.” Other researchers follow this lumping approach while also taking the presentational variant of the gesture as the central explanandum (e.g., McNeill, 1992; Parrill, 2008). In the sign literature, to which we turn later, Engberg-Pedersen (2002) echoes this focus on the presentational use, as do other researchers to lesser degrees (e.g., McKee and Wallingford, 2011). Part of what makes this sticking point particularly sticky is that researchers are not always explicit about how, if at all, they divide up the palm-up form family.

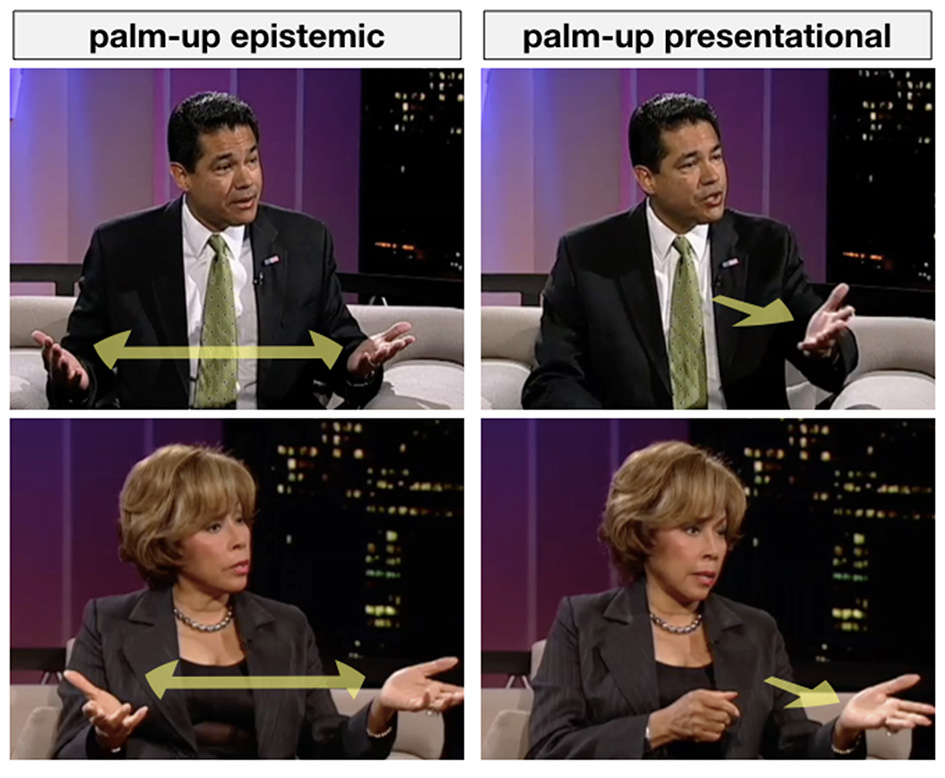

Our own strategy here will be a splitting one. Similar to the proposals of Kendon (2004) and Chu et al. (2013), we draw a key distinction within this extended form family between what we term “palm-up epistemic”1 gestures (comparable to Kendon's “palm lateral” and Chu et al.'s “palm-revealing”) and “palm-up presentational” gestures (comparable to Kendon's “palm-presentation” and Chu et al.'s “conduit gestures”) (Figure 2). There are certainly uses of palm-up forms that do not fall into either category, but we narrow our analysis to these2. For clarity, we label these gestures with reference to the most salient aspect of their form (“palm-up” in both cases) and the most salient aspect of their meaning (“epistemic” or “presentational”). In their prototypical versions in Anglophone and European cultures, these gestures appear to exhibit differences in form: in the protoypical palm-up epistemic gesture, the palm or palms are turned upward and moved outward; in the prototypical palm-up presentational, the palm is directed toward the interlocutor3. However, we caution that form is not a foolproof guide to meaning (see also McKee and Wallingford, 2011; Chu et al., 2013). In many tokens of palm-up gestures, interlocutors—and analysts—will need to assign meaning based on context in addition to form, and some tokens may be compatible with either an epistemic or presentational meaning.

Figure 2

Examples of two gestures within the palm-up form family. In English speakers, depicted here, these gestures prototypically involve different motion patterns. Palm-up epistemic gestures (Left) involve a lateral separation of the hands (or a lateral movement of one hand), and are used to express epistemic meanings. Palm-up presentational gestures (Right) prototypically involve a movement toward the interlocutor as if “presenting” an idea. Images reproduced under fair use.

Again, while we aim to shed light on the entire palm-up form family, our particular focus in much of what follows is the epistemic variant. This is for a few reasons. Both types of palm-up gestures are common in spoken communication (e.g., Chu et al., 2013) and both appear to be used in signed communication (e.g., Engberg-Pedersen, 2002), yet the palm-up epistemic appears to be much more widely incorporated into sign language grammars (e.g., as question-markers or modals). A likely reason for this difference is that the palm-up epistemic gesture has several highly conventional, readily glossable uses (e.g., “I don't know”); it may thus be considered a “holophrastic emblem” in that it can serve as a communicative turn all on its own4. Much research suggests that highly conventional gestures, including holophrastic emblems, are ripe for incorporation into sign systems (Wilcox, 2004; Pfau and Steinbach, 2006; Spaepen et al., 2013; Haviland, 2015). The palm-up presentational gesture, by contrast, is used to underline the presentational function of speech rather than replace speech, and does not appear to have an easily glossable, holophrastic meaning. Another reason for our focus on the palm-up epistemic is that it is perhaps the more puzzling of the two gestures. Though the palm-up presentational gesture is not as easily glossed, its meaning appears to be consistent across uses—it underlines the presentational aspect of speech. The palm-up epistemic, however, is widely associated with a seemingly disparate set of meanings beyond its most conventional ones.

Our division between palm-up epistemic gestures and palm-up presentational gestures makes all the more sense in light of a second sticking point in the literature: the shrug. Though this fact sometimes goes unmentioned, there is a clear affinity between the palm-up epistemic gesture and shoulder shrugs—indeed, the two commonly co-occur, and some have even considered them functionally interchangeable (e.g., Chu et al., 2013). Palm-up presentational gestures, meanwhile, have no such affinity with the shrug. Research on the shrug is scarcer than research on palm-ups, but detailed observations go back to Darwin (1998/1872), who considered the shrug a “gesture natural to mankind” (p. 269), and there are also a handful of more recent studies (Givens, 1977, 1986; Debras, 2017; Jehoul et al., 2017). As we will argue later, understanding the relationship between the shrug and the palm-up epistemic gesture may be critical to understanding the broader palm-up puzzle.

A third and final sticking point concerns what kind of gestures palm-ups are. If researchers agree on anything, it is that palm-ups are interactional in nature—that is, they are not like pointing or depicting gestures that relate to the content of what is being described. Some thus describe them as “interactive” (Bavelas et al., 1992), “speech-handling” (Streeck, 2009), or “pragmatic” (Kendon, 2004) gestures. Some researchers also consider them fundamentally metaphoric, as gestural expressions of the “conduit metaphor” (McNeill, 1992). Another point of disagreement concerns whether palm-ups should be considered conventional “emblems,” “recurrent gestures” (see Müller, 2017), or more idiosyncratic in nature. Evidently, they run the whole gamut: like emblems, they sometimes have a readily glossable meaning (Johnson et al., 1975), but like “recurrent” or idiosyncratic gestures, they can also be layered atop utterances to add shadings of meaning (Gawne, 2018). With these sticking points in mind, we can now move to an overview of observations about palm-up forms, with a focus on the meanings that have been ascribed to the palm-up epistemic gesture.

Discussions of palm-ups in gesture

Observations about palm-ups have a long history (reviewed in Müller, 2004). Quintillian mentions them briefly in his classic discussion of gesture in oratory; John Bulwer notes how a palm-up form is used when “begging;” and Andrea de Jorio describes several contexts in which Neapolitan speakers make use of the form family. The first detailed treatments, however, can be found in Kendon (2004) and Müller (2004). Kendon's (2004) discussion characterizes how the gesture is used by English speakers in Britain and Italian speakers in Naples. As noted earlier, a key feature of his treatment is the separation of the larger family of palm-up forms into three distinct variants: the “palm lateral” (in our terms, the “palm-up epistemic”), the “palm presentation” (in our terms, the “palm-up presentational”), and the “palm addressed” (which we do not discuss). Our focus, again, is on the first of these, the palm lateral, which corresponds most closely to what we term the palm-up epistemic gesture. Kendon distinguishes five uses of this variant: (1) unwillingness or inability on the part of the speaker; (2) that a proposition is obvious; (3) as part of a question that cannot or need not be answered (i.e., a rhetorical question); (4) that a proposition “could be;” (5) the availability of the speaker for service. He discerns an over-arching theme of “non-intervention” running through these uses5. Interestingly, Kendon does comment on the apparent affinity between certain of these uses and the shoulder shrug (p. 265), but he does not dwell on the question of what might explain this affinity.

Müller (2004) presents a rich history of observations about palm-ups—or, in her terms “palm-up open hand” (PUOH) gestures—as well as examples of their use in Spanish speakers. She sees the PUOH as part of an extended family of gestures, but, unlike Kendon, she does not tease out major subdivisions of the family based on motion pattern. For Müller, this family is rooted in practical actions of giving and receiving objects. Thus, she sees PUOH gestures as fundamentally metaphorical in that they treat the abstract objects of discourse—propositions, ideas, questions, answers—like the physical objects of everyday life in that they can be held up, offered, requested, exchanged, and so on.

The giving-related senses Müller identifies for the PUOH center around the idea that there is an imaginary object presented on the palm. These senses include: (1) presenting an abstract object as visible or even obvious; (2) presenting an abstract object for joint inspection; (3) proposing a shared perspective on an abstract object. The receiving-related senses Müller identifies center around the idea that the palm is shown to be empty. These include: (1) to plead for an abstract object; (2) to request an abstract object; (3) to express openness to the reception of some abstract object; (4) to express the fact of not knowing. As noted, Müller does not highlight the contrasts in motion pattern that Kendon (2004) keys in on, nor does she dwell on the affinity between some palm-ups and the shrug. Müller's treatment thus combines uses of the palm-up that Kendon treats as distinct and gives them a single overarching motivation. In some cases, this leads the two authors to different conclusions about what motivates the use of this form. For example, Müller relates the use of the PUOH to express “obviousness” to the idea that some imaginary object is presented forcefully and thus “obviously” on the palm, whereas Kendon relates this use to the idea of non-intervention, that “nothing further can be said” (p. 265).

A more recent analysis by Streeck (2009) combines elements of Kendon's and Müller's accounts. Like Kendon, for instance, he notes the affinity of meaning between certain uses of the palm-up and the shrug. Like Müller, he emphasizes the grounding of palm-up gestures in practical actions. His treatment is also more explicitly steeped in the idea that palm-ups embody metaphors, in particular the “conduit metaphor” (Reddy, 1979; McNeill, 1992), according to which conversation is conceptualized as the exchange of abstract objects through a channel, or “conduit.” A distinctive aspect of Streeck's treatment is his attention to use of palm-ups in certain types of interactive moves, also a focus of some sign language analyses (e.g., Engberg-Pedersen, 2002). For instance, one of the uses he discusses is the “weak offering” in which the palm-up suggests that some idea is being offered up, but without particular conviction or assertiveness.

The only large-scale quantitative analysis of palm-up gestures to date comes from a study by Chu et al. (2013) on individual differences in gesture production. The authors separate out “conduit gestures” (corresponding to Kendon's “palm presentation” variant and our “palm-up presentational” gesture) from what they term “palm-revealing gestures” (corresponding to Kendon's “palm lateral” and our “palm-up epistemic” gesture). They ascribe three primary uses to the palm-revealing variant: to express uncertainty, to express resignation, or to show that the speaker has nothing more to say. Interestingly, they also note a possible motivation for the link between the palm-up form and the meanings they ascribe to it: that the hand is shown to be “empty.” Thus, like Streeck, they echo Müller's interpretation that the palm-up embodies metaphors of giving and receiving. Interestingly, more than other authors to date, Chu et al. (2013) emphasize the affinity of palm-revealing gestures with the shrug. In their coding scheme, for example, shoulder shrugs produced without a palm-up were considered palm-revealing gestures if “used for the same purposes” (p. 700). Finally, they are notably cautious about the possibility of distinguishing these two types of palm-up gestures on the basis of form alone. Though Kendon's description of the “palm lateral” suggests outward movement is always present, Chu et al. note that their “palm-revealing” gestures do not always “move laterally and the palm may not always face upward” (p. 700).

Finally, we turn to the most thorough analysis of a palm-up gesture in a non-European language—Syuba, a Tibeto-Burman language of Nepal (Gawne, 2018). Gawne discusses in particular the “rotated palms gesture family,” which in Syuba is associated with a theme of interrogativity. One of the most interesting aspects of this palm-up gesture—which we take to be a version of the palm-up epistemic gesture—as it is used by Syuba speakers is that it involves a distinctive handshape not reported elsewhere: the index finger and thumb are extended and the remaining fingers curled back into the palm to various degrees. Moreover, the Syuba version does not prototypically involve a lateral movement of the hands, or any other distinctive motion pattern. In terms of its meaning, the emblematic form of the gesture is produced without speech to ask, “What are you doing?” “What to do?” or “What to say?” Such emblematic uses, Gawne notes, are widely attested across India and Nepal and are likely related to formationally similar interrogative signs in the sign languages of the region (see next section). Gawne also observes substantial variation in the gesture's form—it may involve one or two hands, more or less curling-in of the fingers, and a substantial hold or no hold at all. To the gesture in its co-speech uses, Gawne ascribes meanings of interrogativity, uncertainty, and—intriguingly— hypotheticality. Finally, Gawne notes that the gesture is sometimes accompanied by a shrug, particularly in its emblematic meaning of “What to do?”

A number of other observations have been made across cultures about what appear to be uses of the palm-up epistemic gesture. Many are in-passing comments, but it is nonetheless striking that most of the uses of the gesture just discussed have also been described in other, often unrelated communities. Discerning such commonalities in meaning involves interpretation on our part, as researchers do not always use the same descriptors for different uses of the gesture. This caveat aside, we group these observed uses into six meaning categories: absence of knowledge, ability, or concern; uncertainty; interrogatives; hypotheticality; obviousness; and exclamatives (Table 1; see also Appendix 1 in Supplementary Material for a reorganization of the same data, along with additional details from primary sources).

Table 1

| Meaning category | Communities |

|---|---|

|

Absence of knowledge, concern, or ability

Example glosses: “I don't know” “What can I do?” |

Arabic (Barakat, 1973) Catalan (Payrató, 1993) English (American) (Ekman and Friesen, 1972; Johnson et al., 1975; Bavelas et al., 1992; Streeck, 2009) English (British) (Kendon, 2004; Chu et al., 2013) Farsi (Iran) (Sparhawk, 1978) Italian (Neapolitan) (Kendon, 2004) Kenya (Creider, 1977) Russian (Monahan, 1983) Spanish (Colombia) (Saitz and Cervenka, 1972) Spanish (Spain) (Müller, 2004) Syuba (Nepal) (Gawne, 2018) Yoruba (Nigeria) (Agwuele, 2014) Zulu (South Africa) (Brookes, 2004) |

|

Uncertainty

Example glosses: “I'm not sure” “Maybe” |

Arabic (Barakat, 1973) Catalan (Payrató, 1993) English (American) (Johnson et al., 1975) English (British) (Chu et al., 2013) French (Ferré, 2011) Syuba (Nepal) (Gawne, 2018) |

|

Interrogatives

Example glosses: “What?” “Where?” “Who?” “Are you coming?” |

English (American) (McNeill, 1985) English (British) (Chu et al., 2013) Italian (Neapolitan) (Kendon, 2004) Kenya (Creider, 1977) Portuguese (Brazilian) (Rector, 1986) Spanish (Colombia) (Saitz and Cervenka, 1972) Spanish (Spain) (Müller, 2004) Syuba (Nepal) (Gawne, 2018) |

|

Hypotheticals

Example glosses: “I hope he will come.” |

Syuba (Nepal) (Gawne, 2018) |

|

Obviousness

Example glosses: “Of course he did” |

Dutch (Jehoul et al., 2017) English (British) (Kendon, 2004) French (Calbris, 1990) Italian (Neapolitan) (Kendon, 2004) |

|

Exclamatives

Example glosses: “Whatever!” |

Portuguese (Brazilian) (Rector, 1986) |

Observed uses of the palm-up epistemic in gesture.

As suggestive as the evidence is about the pervasiveness and recurring meanings of the palm-up epistemic, it also has limitations. For one, many of these treatments do not include fine-grained descriptions of form, so we cannot be sure that the prototypical motion pattern of the gesture described earlier is found more broadly—in at least one case, a palm-up gesture with epistemic meanings uses a different prototypical form (Gawne, 2018). Further, given that many of these sources do not attempt an exhaustive treatment of the gesture, the lack of mention of any particular meaning should not be taken as evidence that the meaning is absent from a community. A final limitation of the literature is that, even among the extended treatments of the palm-up, quantitative methods are rare (but see, e.g., Chu et al., 2013; Jehoul et al., 2017). Nevertheless, the widespread use and apparent semantic regularities in the palm-up epistemic are striking. A natural further question is whether the palm-up form is universally used to express these meanings—that is, is the palm-up epistemic gesture found in all communities? Any attempt to answer this question would be premature, and absolute universals are notoriously difficult to demonstrate. What we can say, however, is that use of the gesture to express a recurring set of meanings strongly suggests (a) that the meanings are related and (b) that the use of the palm-up form to express them is motivated. We revisit the puzzle presented by these observations later, after first considering comparable evidence from the palm-up in sign.

Palm-ups in sign

Preliminaries

The palm-up form in sign languages has also been widely studied. Though this line of research often nods to possible relations between the gestural and signed uses of the form (see, e.g., Zeshan, 2004, p. 23; Van Loon et al., 2014), little work has directly engaged with both sizeable literatures at once. Several of the sticking points bedeviling work on palm-up forms in gesture are evident here, too—for instance, whether there is more than one form-meaning pairing at work, whether palm-ups are related to the shrug in some way, and how palm-ups should be classified. This last sticking point takes on new significance in the sign literature because one's choice of terminology is bound up with fraught empirical and theoretical issues. Whether palm-ups are considered lexical items, discourse markers, or co-sign gestures has implications—not only for the analysis of this particular form—but for general questions about differences between sign and gesture (e.g., Goldin-Meadow and Brentari, 2017), and about how sign languages may draw on gestures from surrounding speaking communities. In what follows, we focus on the most extended and focused discussions of palm-ups in sign; we begin with palm-ups in well-established sign languages and then turn to homesign systems.

Discussions of palm-ups in sign

One of the earliest in-depth treatments of the palm-up in sign is Conlin et al.'s (2003) analysis of the form in American Sign Language (ASL). The authors note that the form has clear lexical incarnations—such as in the signs WHAT and MAYBE—as well as uses as a discourse particle indicating uncertainty of different kinds. They focus, in particular, on a use of the particle to mark “indefiniteness.” Though difficult to lexically gloss, the addition of the palm-up can turn a sign sentence that means “A boat sank off Cape Cod” into a sentence with a more indefinite meaning, such as “Some boat or other sank off Cape Cod” or “Some kind of boat sank off Cape Cod” (p. 8). Depending on its position, the palm-up may also express indefiniteness, or uncertainty about the proposition as a whole, e.g., “A boat sank off Cape Cod I think” (p. 10). Such uses of the palm-up thus allow one to sidestep conversational norms limiting contributions to those known to be true (Grice, 1975). Conlin and colleagues also briefly describe uses of the palm-up form for emphasis, as in “John does not know the answer!” (p. 13), noting that such an utterance implicitly asks the question, “How could you have thought he would?” And, finally, they characterize several uses of the form in sentences with HOPE and WISH. They link these uses to the broader theme of uncertainty; but, as discussed later, we group these with hypotheticals and other statements of possibility.

Aboh et al. (2005) also pursue a particle analysis for a palm-up sign glossed as G-WH (general WH-word) in Indian Sign Language (IndSL, also called Indo-Pakistani Sign Language; see Zeshan, 2003, where the sign is labeled as KYA:). As in the “rotated palms” gesture in Syuba, the palm-up particle in IndSL has a notable handshape, with the index finger and thumb extended and the other fingers curled slightly into the palm. This sign form can also be used as a sentence-final discourse particle signaling hesitation and as an indefinite marker. The interrogative and indefinite uses of the form also share other syntactic characteristics. Though g-wh is the only specifically interrogative sign in IndSL, it combines with other signs to express more specific interrogative meanings. For example, FACE G-WH can be used to ask “Who?” (Aboh et al., 2005). Similarly, the palm-up form can be combined with the sign MAN to form the indefinite SOMEONE/SOME MAN (Zeshan, 2003). This use of a specific word or morpheme to form paradigms of indefinite and WH-expressions is common across spoken languages.

Around the same time, Engberg-Pedersen (2002) analyzed the palm-up form in Danish Sign Language (Dansk Tegnsprog, DTS). She describes it as fundamentally “presentational,” a “materialization of the conduit metaphor” (p. 143). Like Conlin et al. (2003), she notes that the form appears to be present in certain clearly lexical DTS signs, such as WHAT and WHERE. Her focus, however, is on uses of the form as a “gesture;” she primarily focuses on analyzing how the form is placed in interactive sequences, rather than on identifying its invariant meanings. Though this is not her goal, many of the uses she illustrates bear a clear relation to those identified in ASL and IndSL. These include cases where the signer is expressing uncertainty or tentativeness, or is asking a question. However, it should also be noted that she describes a number of other uses for the palm-up that are hard to square with the observations of other sign researchers. A possible reason for this discrepancy is that Engberg-Pedersen explicitly treats presentational and epistemic uses of the palm-up under the same umbrella, in the same way that some gesture researchers do (e.g., Müller, 2004).

More recently, McKee and Wallingford (2011) have analyzed the palm-up in NZSL, characterizing it as a “frequent and multi-functional item” (p. 240). They are explicit about the thorniness of classifying this “item,” alternately describing it as a “gesture,” a “sign,” or simply a “form.” They note, too, that the palm-up form exhibits wide formational variation; and they report NZSL signers' intuitions that such “variations are neither consistent in usage, nor necessarily contrastive in meaning” (p. 220). Their data consist of a corpus of conversational signing, produced by 20 signers, totaling more than 5,000 signs. They find that the palm-up form accounts for 5% of all signs, making it the second most frequent sign in their corpus [comparable to what has been reported for BSL (Fenlon et al., 2014) and Auslan (Johnston, 2012)]. Following Engberg-Pedersen (2002), the authors focus on the sequential positioning and functioning of the form rather than on its invariant meanings. However, they too note a number of uses for the form that align with those epistemic uses reported elsewhere, including: expressions of uncertainty, interrogatives, hypotheticals, expressions of obviousness, and exclamatives. Intriguingly, they also note an “elaborative” use of the form, in circumstances that resemble the use of English “which” to introduce free relative clauses (p. 229).

Two especially valuable sets of observations about epistemic uses of the palm-up come from studies of homesigners, profoundly deaf individuals raised without access to a conventional language (e.g., Goldin-Meadow and Mylander, 1984; Goldin-Meadow, 2003). The first of these is a study of an adult homesigner (and her hearing associates) from the Enga region of Papua New Guinea (Kendon, 1980). Kendon describes a number of uses of what he calls “the double palm present” and its cousin the “lateral hand flip,” which have related meanings. These are used as a question marker [example utterance: “Whose father is coming?” (p. 276)]; to indicate the absence of knowledge [“I don't know” (p. 277)]; and, less commonly, in a “whether” statement [“Whether he will… that's his business” (p. 276)], which is similar in meaning to uses of the palm-up for hypotheticals reported elsewhere. Kendon discerns a theme running through these uses—“absence of knowledge” (p. 278)—and notes in passing that the double palm present is likely related to the shrug. Finally, he also observes that the form is used in certain contexts to express negation.

The second set of observations focused on a child homesigner in the United States (Franklin et al., 2011). The researchers analyzed 208 uses of the “flip,” as they call the palm-up epistemic, which were observed in a corpus of 3,080 gestured utterances that the signer, David, produced between the ages of two and four. Three primary uses of the gesture were observed. A first was to mark questions [e.g., “Why is the car there?” (p. 8)]—indeed, 92% of questions in the dataset involved a flip, while others were marked by a facial expression or, interestingly, a shrug. Of comparable frequency was the use of the flip as an exclamative—that is, to mark heightened affect. Examples included cases in which David was showing frustration (“Whatever!”) or expressing surprise. Under the umbrella of exclamative use, the researchers also included expressions of “doubt,” a use of the palm-up epistemic observed in hearing gesturers and already discussed. Finally, a rarer but intriguing use of the form turned up in David's expressions about location. In one example, David combined a palm-up form with a pointing sign to create an utterance glossed as “The place where the puzzle goes is the toy bag” (p. 407). The authors interpret this use as analogous to what are sometimes called “free relative” expressions. In fact, as the authors observe, these three uses—interrogatives, exclamatives, and relatives—are tacitly connected in English and other spoken languages through their common use of interrogative words.

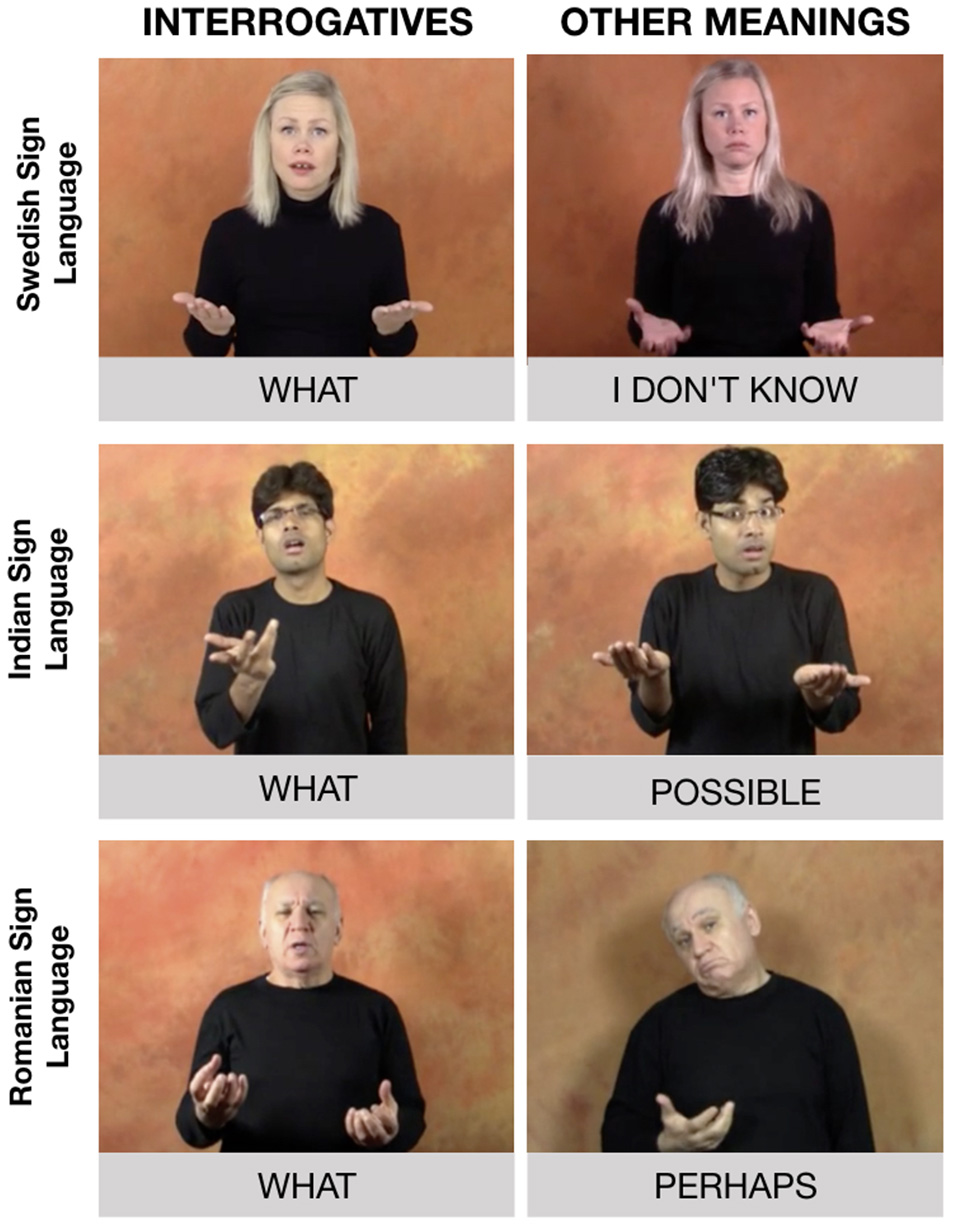

A number of further observations have been made about what appears to be the palm-up epistemic in other signing communities (Table 2; see Appendix 2 Supplementary Material for a reorganization of the same data, with additional details), though often in passing. Most interesting for our purposes, these observations, taken together, touch on all of the meaning categories ascribed to the palm-up epistemic in co-speech gesture and discussed earlier: expressions of absence of knowledge, concern, or ability; expressions of uncertainty; interrogatives; hypotheticals; expressions of obviousness; and exclamatives (for examples, see Figure 3). Several other meanings ascribed to the palm-up epistemic in sign do not have a clear counterpart in the existing gesture literature, however. For example, the use of the palm-up for indefinites (someone, somewhere, somehow) has been described in both ASL (Conlin et al., 2003) and IndSL but not in any hearing community to date. These uses may be closely related to the interrogative uses of the palm-up. After all, though not the case in English, it is common cross-linguistically for indefinite expressions to be formed out of question words (Ultan, 1978; Haspelmath, 1997), as noted above in the discussion of g-wh in IndSL. Further, several authors also note that the palm-up is used to express negation in certain contexts, a phenomenon observed in Turkish Sign Language (Zeshan, 2006b), Inuit Sign Language (Schuit, 2014), and Enga homesign (Kendon, 1980). Finally, observations of the palm-up in ASL (Conlin et al., 2003) and in US homesign (Franklin et al., 2011) note uses of the palm-up in non-restrictive and free relative clauses—intriguingly, both places where interrogative words are used in English and other spoken languages. Thus, though the palm-up epistemic may be used for a wider set of meanings in sign than in gesture, these additional uses appear to be extensions of the interrogative meaning that is attested in gesture. In delving into the meaning of the palm-up epistemic in the next section, we focus on the six categories where there is clear attested overlap between gesture and sign.

Table 2

| Meaning category | Communities |

|---|---|

|

Absence of knowledge, concern, or ability

Example glosses: “I don't know” “What can I do?” |

Enga homesign (Papua New Guinea) (Kendon, 1980) |

|

Uncertainty

Example glosses: “I'm not sure” “Maybe” |

American Sign Language (Conlin et al., 2003) Danish Sign Language (Engberg-Pedersen, 2002) Indo-Pakistani Sign Language (Zeshan, 2003) Inuit Sign Language (Schuit, 2014) New Zealand Sign Language (McKee and Wallingford, 2011) Sign Language of the Netherlands (Van Loon, 2012) Turkish Sign Language (Zeshan, 2006b) US homesign (Franklin et al., 2011) |

|

Interrogatives

Example glosses: “What?” “Where?” “Who?” “Are you coming?” |

American Sign Language (Conlin et al., 2003) Danish Sign Language (Engberg-Pedersen, 2002) Enga homesign (Papua New Guinea) (Kendon, 1980) Finnish Sign Language (Zeshan, 2004) Indo-Pakistani Sign Language (Zeshan, 2003) Inuit Sign Language (Schuit, 2014) Israeli Sign Language (Meir, 2004) New Zealand Sign Language (Zeshan, 2004) Providence Island Sign Language (Washabaugh et al., 1978) Sign Language of the Netherlands (Van Loon, 2012) Tanzania Sign Language (Zeshan, 2013) Turkish Sign Language (Zeshan, 2006b) US homesign (Franklin et al., 2011) Yucatec Maya Sign Language (Shuman and Cherry-Shuman, 1981) Yolngu Sign Language (Bauer, 2015) |

|

Hypotheticals

Example glosses: “I hope he will come.” |

American Sign Language (Conlin et al., 2003) Enga homesign (Papua New Guinea) (Kendon, 1980) New Zealand Sign Language (McKee and Wallingford, 2011) |

|

Obviousness

Example glosses: “Of course he did” |

New Zealand Sign Language (McKee and Wallingford, 2011) |

|

Exclamatives

Example glosses: “Whatever!” |

American Sign Language (Conlin et al., 2003) New Zealand Sign Language (McKee and Wallingford, 2011) US homesign (Franklin et al., 2011) |

Observed uses of the palm-up epistemic in sign.

Figure 3

Examples of signs involving palm-up forms, taken from three unrelated sign languages. Signs in the left column have interrogative meanings; signs in the right column have other epistemic meanings, such as absence of knowledge. All images, glosses, and language classifications are from the “Spread the Sign” dictionary (https://www.spreadthesign.com). Images reproduced with permission.

On a cautionary note, there are limitations to the existing literature on the palm-up epistemic in sign, and these parallel the limitations of the gesture literature. For one, many of the observations collated above are drawn from brief mentions, and do not always include fine-grained descriptions of form. It is thus unclear whether the palm-up epistemic in sign resembles the prototypical form of the gesture discussed earlier—indeed, beyond the core palm-up aspect of the form, there appears to be considerable variation across languages (see Figure 3). Further, since interrogatives have become a topic of interest in sign language typology (Zeshan, 2004, 2006a), a number of sources comment on the palm-up in this context without venturing observations about wider usage. Finally, as in the gesture literature, there are only a handful of quantitative corpus treatments, making it difficult to assess, for instance, how commonly the palm-up is used to express the various meanings ascribed to it. Thus, as in gesture, further research is warranted.

The palm-up puzzle

We now turn to the puzzle highlighted in our title. The broader puzzle concerns the meanings and origins of the entire palm-up form family. But a smaller and especially perplexing puzzle concerns the meanings and origins of the palm-up epistemic gesture in particular. This second, smaller puzzle has two parts. First, how are the six superficially distinct meanings for the palm-up epistemic gesture related, if indeed they are? Second, why is this form used for these meanings? In this section, we take these questions in turn.

How are these meanings related?

Several of the meaning categories just discussed appear obviously connected, others less so. Why should we assume that these meanings are related in the first place? In making this assumption, we follow an inference commonly made in the study of linguistic polysemy: when one form covers the same meanings in different languages, there is most likely a conceptual link between those meanings, however distinct they may seem on the surface (e.g., Jurafsky, 1996; Evans and Wilkins, 2000). Indeed, so-called “accidental homophony” is usually considered an explanatory last resort. Given that the palm-up epistemic is associated with each of the six meaning categories in more than one community, we thus assume there are conceptual links between these meanings.

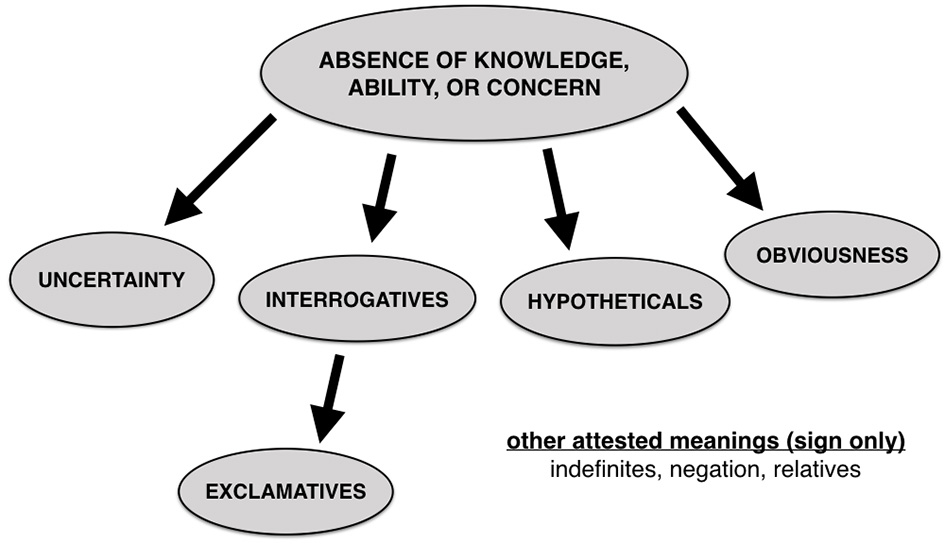

In trying to make sense of these links, we take inspiration from other accounts of cross-linguistic tendencies in meaning extension, such as Jurafsky's (1996) account of the sprawling meanings of diminutives. Such accounts posit a core meaning and then show how other observed meanings can be understood as extensions from that core, or as extensions from extensions. Together these nodes and extensions comprise what might be called a meaning network. We take the core meaning of the palm-up epistemic to be the expression of absence—of knowledge (“I don't know”), ability (“I can't”), or concern (“I don't care”)—on the part of the speaker (for similar proposals, see Kendon, 1980; Zeshan, 2013). Importantly, the form is not widely used to convey the objective absence of some external entity, substance, or quality in the world (“There is none” or “There are none”) (but see footnote 2). Rather, it is used to convey the absence of some inner state or attitude. This meaning—which, for simplicity, we gloss as absence of knowledge—is among the most widely attested cross-linguistically, and each of the five other meaning categories ascribed to the palm-up can be considered extensions from this core. Here we discuss each of these extensions in turn, beginning with the more intuitive ones (e.g., how the absence of knowledge meaning motivates uncertainty-related meanings) and proceeding to the more surprising ones (e.g., how the absence of knowledge meaning motivates exclamative meanings). We summarize this meaning network in Figure 4, leaving aside for now meanings documented only in sign. Importantly, the fact that these extensions are attested across communities does not imply that the palm-up epistemic will exhibit all of these extensions in every community; it does imply, however, that communities will not skip over nodes in the network.

Figure 4

Proposed meaning network connecting the most broadly attested meanings of the palm-up epistemic in gesture and sign, with a core meaning of absence of knowledge, ability, or concern.

ABSENCE OF KNOWLEDGE > UNCERTAINTY

The expression of absence of knowledge can take different forms. Most basically, it can take the form of a confident statement that one lacks relevant knowledge, a simple assertion of “I don't know.” However, language users are often unsure about whether they remember a fact correctly, fully grasp a concept, or completely agree with a statement, and, accordingly, they distance themselves from the truth of their statements. Such expressions of uncertainty can be conceptualized as a higher order absence of knowledge—that is, a lack of knowledge about one's own knowledge or belief. Speakers have a range of resources for conveying uncertainty, including linguistic resources discussed under the banners of “modality” (Palmer, 1986) or “epistemic stance” (Du Bois, 2007), and a range of gestural resources beyond palm-ups (Roseano et al., 2014). In English, available linguistic resources include modal words like “maybe,” “perhaps,” or “could,” as well as so-called hedges, such as “I'm not sure,” “I guess,” “Well…” and so on. Linguistic hedges have been described as devices for distancing oneself from the truth (or falsity) of a proposition, giving language users the resources to express things that aren't quite true, aren't quite false, or aren't quite true or false (Lakoff, 1973). Gestural hedges like the palm-up epistemic seem to perform the same function. The uncertainty category may partially account for why palm-ups are highly frequent in corpus studies of signed communication—the form, among its other functions, seems to be a favored pragmatic hedge in some sign languages (e.g., NZSL). Interestingly, instances of the palm-up sign used as a pragmatic hedge or hesitation marker tend to be classified as “gestural”—that is, part of signed communication but not part of the grammar or lexicon (e.g., McKee and Wallingford, 2011).

ABSENCE OF KNOWLEDGE > INTERROGATIVES

Another of the meaning categories most widely associated with the palm-up epistemic is interrogatives. While some authors describe the form as being associated with particular subtypes of questions (e.g., rhetorical; Kendon, 2004), most link it to the broader category of interrogatives. The link between absence of knowledge and interrogative meanings is perhaps intuitive. A question, after all, can be thought of as doing two things: first, implying that the questioner lacks relevant knowledge, and, second, putting it to the addressee to supply that knowledge (Wierzbicka, 1977; Kendon, 1980; Franklin et al., 2011). Thus, much as the gesture may be used when the speaker is expressing absence of knowledge, it may also be used when the speaker is both expressing absence of knowledge and asking the interlocutor to supply that knowledge. Interestingly, it is the interrogative uses of the palm-up epistemic that appear to be the best studied and documented in sign languages (see Zeshan, 2004; Table 2); but whether the interrogative use is indeed the one most often lexicalized across sign languages remains a question for future work.

ABSENCE OF KNOWLEDGE > HYPOTHETICALS

The absence of knowledge sense also extends to hypotheticals, such as those associated with the palm-up epistemic in Syuba (Gawne, 2018); statements in the subjunctive mood (“I wish…”), such as those associated with the palm-up particle in ASL (Conlin et al., 2003); and “whether” statements, such as those associated with the sign in Enga (Kendon, 1980). For simplicity—and lack of an appropriate general term—we refer to these uses together as “hypotheticals.” The link to absence of knowledge is, again, relatively intuitive: when speakers describe a state of affairs that has not happened and may or may not happen, they implicitly convey an absence of knowledge about that state of affairs. Interestingly, these and other uses of the palm-up epistemic appear to fall under the umbrella of irrealis (e.g., Elliott, 2000). This is a broad category, covering statements of all kinds about events or facts that are not “real” in the sense that they have not yet happened; in some accounts, it includes hypotheticals, interrogatives, imperatives, and more. But, importantly, the palm-up epistemic does not appear to be associated with the entire irrealis category—for example, there is no evidence for an association between palm-ups and imperatives.

ABSENCE OF KNOWLEDGE > OBVIOUSNESS

A meaning category that is less intuitively related to the absence of knowledge is obviousness. Indeed, this extension is, at first blush, puzzling: Why would the very same gestural form sometimes be used to convey a lack of certainty and, other times, to convey a conviction that something is so certain as to be obvious? One straightforward account of this link is that expressing that something is obvious amounts to expressing that “I don't know what else I could say about it” (Jehoul et al., 2017, p. 7). The use of the palm-up epistemic to express obviousness resembles a similarly counter-intuitive extension of gestural meaning observed in the case of headshakes: speakers commonly shake their heads while making extreme positive evaluations (e.g. “It was marvelous”; Kendon, 2002, p. 172–3). A possible explanation is that, in such cases, the speaker is rejecting an implicit assumption that something is ordinary or unremarkable. In a similar way, when using palm-ups to express obviousness, speakers may be reacting to an implicit assumption that more could or should be said—they are asserting that, in fact, they do not know more, do not care more, or are not able to say more. Another account of the link between absence of knowledge and obviousness would consider it a less-direct extension, mediated by interrogative uses of the palm-up epistemic. On this account, the statement that something is obvious can be seen as entailing an implicit question, such as “How could it be otherwise?” “How could you not know this?” or “What else could one say?” More data are needed to adjudicate between these possible paths of extension; for now, we default to the more parsimonious assumption that obviousness extends directly from absence of knowledge. Regardless of the extension path, this use of the gesture is distinct from the others discussed so far in that it expresses something about the speaker's affective state. Here the palm-up serves what is sometimes described as an expressive function (e.g., Cruse, 1986; Potts, 2007) in that it changes the affective coloring of the utterance but not the information it conveys—that is, its assertive content.

INTERROGATIVES > EXCLAMATIVES

Another meaning category less obviously connected to the others is exclamatives. Exclamatives are statements exhibiting a high degree of affect, whether positive or negative (in this category we include uses of palm-ups as part of “emphatic statements”; Rector, 1986; Conlin et al., 2003). As with the category of obviousness, there is something initially puzzling here. Why would the same gesture be sometimes used to convey a lack of certainty or concern and, other times, to convey extreme certainty or concern? And, again, as with the category of obviousness, exclamative uses of the palm-up epistemic are fundamentally expressive. We interpret the association of palm-ups with exclamatives as an extension of their association with interrogatives. This extension path parallels the cross-linguistically robust phenomenon in spoken languages whereby interrogative words are used to form exclamatives (e.g., Bolinger, 1972; Wierzbicka, 1977; Espinal, 1995). Examples in English include expressions such as “How rude!” and “What a jerk!” Further, though cross-linguistically less common (Rett, 2008), exclamatives may also be derived from polar interrogatives (e.g., “Boy, did she run!”). The precise semantic-pragmatic motivation for this repurposing of interrogative structures in exclamatives remains a matter of theoretical discussion (e.g., Rett, 2008). These clear links to interrogatives notwithstanding, it should also be noted that exclamatives can be marked in a number of ways—that is, utterances with exclamative force are not uniformly couched in a particular structure. In a similar way, the palm-up epistemic gesture appears to be associated with exclamations generally (e.g., “That's great!”), whether or not they involve interrogative words or other interrogative structures.

Evaluating the proposed extension paths

The meaning network just proposed crystallizes a hypothesis, one that remains to be tested and refined. Doing so will require more data—in particular, more detailed, systematic, quantitative analyses from across languages, both spoken and signed. Here we highlight several kinds of data that would be especially useful in assembling a clearer picture.

A first type of data that would be useful are observations over the lifespan, that is, developmental data. Knowing how children use the palm-up epistemic gesture initially, for instance, may shed light on its core meaning. Though we have proposed that the core of the gesture is absence of knowledge (see also Kendon, 1980; Zeshan, 2013), there are other possibilities. For instance, the gesture could have roots in the expression of external, objective absence, rather than absence of knowledge, ability, or concern. The emblematic “all gone” gesture—used to remark on objective absence—is well attested in children's early communication and in child-directed speech (see footnote 2). Indeed, some observations suggest that this gesture may emerge before epistemic uses of the palm-up form (e.g., Beaupoil-Hourdel and Debras, 2017). Whether such observations contradict our proposal, however, is unclear. The distribution of the “all gone” gesture is currently unknown. Such a convention may occasionally arise because objective absence is a more accessible meaning for young children than absence of knowledge. That is, the “all gone” gesture could be a kind of a gestural “back formation” that becomes conventionalized in some communities. More cross-linguistic developmental data will be needed to explore this possibility.

Developmental data would also shed light on particular paths of meaning extension. We would not necessarily expect children to use the palm-up for all of the attested meanings in the network—much as we would not expect all communities to use the palm-up for all meanings in the network—but, again, we would expect children not to skip over nodes in the network. Thus, if our proposed path from absence of knowledge to interrogatives to exclamatives is correct, children may not use the palm-up epistemic exclamatively until they have already begun to use it interrogatively; in turn, they may not use it interrogatively until they have already begun to use it to express a lack of knowledge. In practice, such semantic extensions may be hard to detect because several meanings may emerge within a narrow time frame. Developmental analyses of this sort have recently begun to shed light on how other bodily forms of communication take on new meanings (for the case of negation, see Andrén, 2014; Beaupoil-Hourdel et al., 2016). And one recent study throws some valuable initial light on developmental changes in how palm-up forms are used. Graziano (2014) examined the emergence of “palm lateral” (in our terms, the palm-up epistemic) and “palm presentation” (in our terms, the palm-up presentational) gestures in Italian children between the ages of 4 and 10. She found that palm-up epistemic gestures were present in the youngest children, but that palm-up presentational gestures did not emerge until later ages. Moreover, she noted that children first used the palm-up epistemic along with “crystallized expressions” (p. 311), such as “I don't know,” and only later used them more flexibly as adults do, e.g., to express obviousness. This finding is consistent with our suggestion that obviousness is an extension of absence of knowledge, and thus should emerge later. Further studies of the developmental changes in use of the palm-up form family would be valuable, including studies in different speaking communities and with even younger children.

Another important source of data would be additional studies with adult speakers and signers, both corpus-based and experimental. A corpus-based analysis using the categories of meanings described above, for instance, could shed light on which meanings are most common within and across languages. At present, our understanding of the relative prominence of these different meanings is sketchy at best, based largely on the number of communities in which they have been reported. Corpus studies may also reveal additional recurring meanings of the palm-up epistemic beyond the six we have focused on. There have already been several insightful corpus-based treatments of the palm-up in sign, but especially valuable would be further studies that compare use of the form in different sign languages using the same analytic criteria and theoretical framework. Such an approach would be critical in distinguishing cross-linguistic patterns from language-specific particulars.

Experimental studies in both speakers and signers would provide complementary insights. Elicitation tasks would be helpful in discerning the strength of association between particular meaning categories and the palm-up epistemic. In gesturers, a well-devised elicitation task might tell us whether, for instance, speakers associate the gesture more strongly with expressions of absence of knowledge than with expressions of obviousness, as might be predicted from the fact that absence of knowledge is the proposed core. In signers, similar tasks could shed light on which uses of the palm-up epistemic are strongly tied to certain contexts—and thus, by hypothesis, are more grammaticalized—and which are less strongly tied—and thus are more gestural, or affective. Judgment tasks with both groups could also be illuminating. Do listeners find palm-up epistemics in certain discourse contexts—or co-produced with certain words (e.g., interrogative words)—to be more natural than others? Such studies could shed crucial light on the shadings of meaning that palm-ups add when conjoined with certain kinds of discourse content or when produced in certain conversational positions.

Why this form for these meanings?

The second part of the palm-up puzzle is why these meanings are associated with this form in particular. We assume there is indeed a motivation behind the pairing of these meanings with this form simply because of the recurrence of the pairing across communities. This inductive inference is parallel to one commonly made in studies of figurative language and grammaticalization: if the same target concept is expressed using the same source concept in more than one speech community, there is likely a motivated relationship between to the two concepts (e.g., Brown and Witkowski, 1981; Sweetser, 1990; Heine, 1997). But it is also possible, of course, that there really is no motivation to explain. On this skeptical account, the palm-up epistemic could be merely a “catchy convention” that has spread far and wide, emanating perhaps from some centuries-old source in European culture. We think this scenario is unlikely. The wide distribution of the gesture—a distribution matched only by a few other bodily communicative forms, such as headshakes, index-finger pointing, and certain facial expressions—suggests independent development in different communities. And independent development, in turn, suggests an underlying motivation. There can be little doubt that there are conventional aspects to the palm-up. That is, part of why people use it in the ways that they do (e.g., with the distinctive handshape used in Syuba) is that others in their community use it in these ways. Crucially, however, just because a communicative form has conventional aspects does not mean it is unmotivated (e.g., Jakobson, 1972; Enfield, 2009). Here we consider two explanations for the underlying motivation between the palm-up form and the meaning it is so widely associated with—absence of knowledge, which we take to be its core meaning. As will become clear, questions about the origins of palm-up gestures are impossible to separate from a sticking point with which we started: whether there is one interconnected family of palm-up gestures or separate gestures with similar forms.

The metaphorical account

A first of account of the origins of the palm-up epistemic gesture is that it is a kind of metaphorical action, rooted in practical actions of giving and receiving physical objects (e.g., Müller, 2004; see also McNeill, 1992; Engberg-Pedersen, 2002; Parrill, 2008; Streeck, 2009). On this account, the gesture expresses the “conduit metaphor” (Reddy, 1979; McNeill, 1992), in which discourse is understood as object exchange: ideas are presented and requested much as real objects are in routine activities. In line with this metaphor, palm-ups generally can be seen as representing that the hands are metaphorically full, and a discourse object is being offered to the listener, or that the hands are metaphorically empty, and a discourse object is being requested. Intuitively, if palm-ups sometimes represent empty hands, we have a plausible motivation for what we take to be the core meaning of the palm-up epistemic: that the speaker lacks some knowledge, internal state, or attitude (e.g., Chu et al., 2013). In a similar way, when using the palm-up in the course of asking a question, the speaker may be showing that the hand is “empty” of knowledge, or, perhaps, inviting the listener to put some knowledge into that empty hand (e.g., Müller, 2004). Kendon (2004) also describes the gesture as rooted in practical action but keys in on a different aspect of the gesture's form: he sees the lateral movement as indicating that “whatever has been presented is being withdrawn from” (p. 265). There are certainly appealing features of this type of metaphorical account. The general idea that many discourse-related gestures are rooted in practical actions has explanatory power and intuitive plausibility. In the case of the headshake used for negation, for instance, researchers have made a plausible case that its motivations lie in the practical action of averting the face from a food source (Darwin, 1998/1872; Beaupoil-Hourdel et al., 2016), and many recurrent gestures seem to be related to action schemas (e.g., Müller, 2017).

However, there are also limitations to such a metaphorical account as it applies to palm-ups. Most importantly, the account is mum about the widely observed relation between palm-up gestures and shrugs. As has been widely observed, palm-ups and shrugs are frequently co-produced and overlap in meaning (as noted in Kendon, 1980, 2004; Franklin et al., 2011; Chu et al., 2013). And, yet, people do not shrug their shoulders as part of the routine exchange of objects. The shrug seems to demand an explanation outside of the realm of practical action, and so, too, may the palm-up epistemic. The second explanation for the gesture's motivation centers on its relation to the shrug.

The reduced shrug account

A different account sees the palm-up epistemic as derived from the shrug. The shrug—as described originally by Darwin (1998/1872) and by several observers since (Givens, 1977, 2016; Streeck, 2009; Debras, 2017; Jehoul et al., 2017)—is a multifaceted display that very often involves rotating the forearms so that the palms turn upward. It has been attested in a range of cultures, in both speakers (e.g., Creider, 1977; Feldman, 1986; Agwuele, 2014) and signers (e.g., Zeshan, 2006b; McKee and Wallingford, 2011; Schuit, 2014), and is sometimes considered a “candidate gesture universal” (Streeck, 2009, p. 189). Interestingly, the meanings of the shrug are less controversial than the meanings of palm-ups. Observers broadly agree that the shrug is used primarily to indicate absence of knowledge, ability, or concern—the same meaning we have described as the core meaning of the palm-up epistemic gesture—and that it can also be used to indicate both uncertainty and obviousness (Debras, 2017; Jehoul et al., 2017), two of the other meaning categories commonly associated with the palm-up epistemic6. But what motivates the connection between the shrug and these meanings? As noted already, the shrug is not a component of practical actions involving object exchange. Darwin (1998/1872) explained its origins in a different way, by invoking his “principle of antithesis.” According to this principle, a certain meaning will sometimes be expressed with a certain bodily form, not because that bodily form itself naturally expresses the meaning, but because it contrasts with another bodily form that naturally expresses the contrasting meaning. In other words, a form of expression may be motivated in that its “antithesis” is motivated. The widespread use of the head nod for affirmation may be described in just this way: it is not naturally connected to affirmation, but in its vertical movement pattern it contrasts with the lateral pattern of the head shake, which many have argued is naturally connected to negation because it emerges out of the act of refusing food. For Darwin, to understand why the shrug means what it does we must first understand its bodily opposite: an aggressive, fighting stance, which involves making fists, squaring the shoulders, and making the arms rigid. By bodily contrast with this assertive posture, the shrug embodies a non-assertive, non-aggressive attitude. A related proposal is that the shrug is rooted in a primordial crouching posture (Givens, 1986). Both explanations highlight the non-assertiveness of the shrug, and might thus plausibly account for why the gesture would be used widely to express absence of knowledge, ability, or concern and, by extension, the other meanings reviewed earlier.

As others have noted, the palm-up epistemic when produced on its own can be described as a reduced, or manual-only version of the shrug. Darwin (1998/1872) himself noted that shoulder movement is an optional component; he describes, for instance, a shrug that takes the form of a “mere turning slightly outwards of the open hands” (p. 266). One group of researchers refers to palm-ups, in fact, as “hand shrugs” (Johnson et al., 1975). Another group, in investigating the prevalence of different bodily components of the shrug display, reports that the palm-up form is, in fact, a more frequent component of the shrug than shoulder action (Jehoul et al., 2017, p. 3). More generally, many researchers since Darwin have noted connections between the shrug and the palm-up (Givens, 2016; Debras, 2017), and some have described them as functionally interchangeable (Chu et al., 2013). Regardless of whether one endorses Darwin's account of the antithetical origins of the shrug in its particulars, a strength of the reduced shrug account is that it takes seriously the clear affinity between palm-up epistemics and shrugs, rather than ignores it.

But the reduced shrug account is not without limitations. Notably, the meanings of the shrug and of the palm-up epistemic, while clearly overlapping, do not appear to be completely co-extensive. Absence of knowledge, uncertainty, and obviousness have all been attributed to both gestures. But, notably, shrugs do not appear to be widely used for interrogative functions (though see Franklin et al., 2011). How might we account for this partial dissociation? A possible explanation concerns how readily different bodily actions can be produced to overlap with speech. Shoulder shrugs with palm-ups, shoulder shrugs without palm-ups, and palm-ups without shoulder shrugs can all be used to good effect on their own—that is, without co-occurring speech, or as prefaces or end-caps on utterances. However, the palm-up and shrug are not equally suited to spanning over long stretches of talk. In order to be salient, the shoulder-hunching component of the shrug requires a relatively quick up-and-down movement of the shoulders. Shoulder shrugs are thus not easily held in a way that spans across speech. Palm-ups, by contrast, do not have this limitation, as they remain salient when held. Intriguingly, one recent study noted a marked difference in how long different components of the shrug (e.g., shoulder action, palm-up form, and head tilt) were held (Jehoul et al., 2017, p. 8). Speculatively, if the palm-up form is a component of the full-blown shrug display better suited for spanning over speech, it may be more strongly associated with functions that take scope over an utterance (e.g., interrogatives).

To be sure, the ultimate origins of this form-meaning pairing are hard to pin down decisively. Part of the difficulty in adjudicating between the “metaphorical” and “reduced shrug” accounts just sketched is that they tend to have different explanatory targets. Many proponents of the metaphorical account do not observe a distinction, as we and others do (Kendon, 2004; Chu et al., 2013; Graziano, 2014), between what we have called palm-up presentational gestures and palm-up epistemic gestures. Rather, they have in mind a broader family of palm-up forms with a broader family of meanings, built around a “presentational” core (Engberg-Pedersen, 2002; Müller, 2004; Parrill, 2008). A compelling possibility, in our view, is that the metaphorical account best explains the palm-up presentational, whereas the reduced shrug account best explains the palm-up epistemic. On this account, the palm-up presentational and palm-up epistemic gestures may be best thought of as “false friends”—that is, communicative forms that look deceptively alike, but actually have quite different meanings and origins. But, certainly, to begin to adjudicate between possible origin stories, we first need a better handle on the relationship between these two proposed gesture variants. Other observations could also tip the balance in favor of one or the other of the origin stories outlined above. If the reduced shrug account is correct, we would not expect to find the palm-up epistemic gesture in broad use except in those cultures where the shrug is also in broad use. We might also expect to find that, developmentally, the shrug precedes, or at least co-occurs with, the palm-up epistemic. The metaphorical account does not predict either of these patterns.

Conclusion

One of the most common gestural forms that speakers produce in everyday communication involves rotating the forearms so that the palms face upward. Palm-up forms are captured in the paintings of Renaissance masters and in the GIFs and emoji of contemporary social media; they are produced by gesturers and signers the world over. In their pervasiveness, cross-linguistic spread, and frequent incorporation into sign language grammar, palm-up forms may be surpassed only by pointing and head gestures. And yet palm-ups remain puzzling. They vary considerably from one use to the next, even in sign languages; they go by different labels; they resist current gesture classification schemes and elude existing linguistic categories. In fact, it is not even clear what the palm-up form family consists of—one sprawling family of interconnected meanings, a family with salient divisions, or perhaps a pair of “false friends.” A number of meanings have been attributed to palm-ups, not always obviously connected to each other, and sometimes even contradictory. And fundamentally different accounts have tried to explain the fact that this particular form—however we label, classify, or circumscribe it—is used for similar meanings in culture after culture.

Here, we have tried to find some clarity amid these complexities. Following others, we proposed a distinction between the palm-up presentational and the palm-up epistemic, and focused our attention on the latter. We showed that, in the existing literature, at least six meaning categories have been recurrently associated with this variant of the palm-up in both gesture and sign. Examining what we have described as the first part of the palm-up puzzle—how these meanings are related—we showed that this set can be understood as extensions from a kernel meaning of absence of knowledge. Examining the second part—why this form is associated with this set of meanings—we sketched two accounts, a “metaphorical account” and a “reduced shrug account.” This does not mean, of course, that we can now pronounce the palm-up puzzle solved. But the first step in solving any puzzle is to figure out what the pieces are—and we hope to have made progress toward this more modest goal. We have also made concrete suggestions for where research on palm-ups could go next. Part of our interest in this puzzle has little to do with the palm-up form family per se. Rather, it has to do with meaning generally: with how bodily forms come to express abstract meanings; how meanings extend to new meanings; and how bodily forms combine with language—as in the case of co-speech or co-sign gestures—or even become grammaticalized—as in the case of sign. Future efforts to illuminate palm-ups will throw much-needed light on this broader puzzle too.

Statements

Author contributions