Abstract

Bilingualism might help children develop Theory of Mind, but the evidence is mixed. To address the disagreement in the literature, a meta-analysis was conducted on studies that compared bilingual and monolingual children on false belief and other Theory of Mind tests. The meta-analysis of 16 studies and 1,283 children revealed a small bilingual advantage (Cohen's d = 0.22, p = 0.050). A secondary analysis was conducted on studies (k = 8) that statistically adjusted the Theory of Mind scores to correct for a bilingual disadvantage in language proficiency. This secondary analysis indicated a medium-size bilingual advantage (Cohen's d = 0.58, p < 0.001). There was no evidence for publication bias in either analysis. Taken together, the results provide support for a beneficial effect of acquiring two languages on mental state reasoning. Explanations for this bilingual advantage, which include bilingual-monolingual differences in executive functioning, metalinguistic awareness, and socio-pragmatic abilities, are discussed.

Introduction

Bilingualism research in the modern era has been dominated by a potential bilingual advantage in executive functioning. This advantage, which is supported by many studies (Bialystok, 1999; Bialystok et al., 2004; Costa et al., 2008), has been communicated to the general public through significant media coverage (Bhattacharjee, 2012; Reville, 2014). Yet, several recent studies have failed to replicate this finding (Morton and Harper, 2007; Paap and Greenberg, 2013; Antón et al., 2014), leading many researchers to doubt its validity (de Bruin et al., 2015; Paap et al., 2016), and creating a division in the bilingualism research community between believers and skeptics (Bak, 2016; Bialystok, 2016; Titone et al., 2017). This ambiguous state of the literature is not limited to executive functioning. It extends to other aspects of mental functioning, such as Theory of Mind, a socio-cognitive ability that is thought to be closely linked to executive functioning (Devine and Hughes, 2014).

In the research addressing whether bilingual children have an advantage over their monolingual peers in the development of Theory of Mind, the answer has been mixed (Goetz, 2003; Kovács, 2009; Kyuchukov and De Villiers, 2009; Fan et al., 2015; Gordon, 2016; Dahlgren et al., 2017), often even within a single study (Bialystok and Senman, 2004; Chan, 2004; Nguyen and Astington, 2014; Diaz and Farrar, 2018). To help disambiguate the ambiguous literature, the current study statistically combined data from many previous studies through a meta-analysis. To provide the background for the meta-analysis, the rest of the Introduction describes the concept of a Theory of Mind and common tests of this ability, followed by reasons for why bilingual children might perform better than their monolingual peers on these tests.

Theory of Mind refers to the ability to attribute mental states to other people and to predict and explain other people's behavior on the basis of those attributed mental states. This ability is often assessed through a false belief test, such as the unexpected-transfer test (Wimmer and Perner, 1983; Baron-Cohen et al., 1985) and the unexpected-contents test (Hogrefe et al., 1986; Perner et al., 1987).

In a popular version of the unexpected-transfer test, known as the Sally-Anne test (Baron-Cohen et al., 1985), participants see a character, who is named Sally, put a marble into a basket. Sally then leaves the scene, and while away, a second character, who is named Anne, removes the marble from the basket and puts it into a box. Next, Sally returns to the scene to retrieve the marble. The key question for the participant is: “Where will Sally look for the marble?” The correct answer is that Sally will look for the marble in the basket, which is where she put it (and not in the box, where it currently is). Answering correctly requires assigning the correct mental state to Sally (namely, the false belief that the marble is in the basket) and predicting her behavior on the basis of that assigned mental state (namely, that she will look in the basket because she falsely believes that the marble is in the basket).

In another commonly-used assessment of Theory of Mind called an unexpected-contents test (Hogrefe et al., 1986; Perner et al., 1987), participants are shown, for example, a tube of Smarties candies and are asked what the tube contains. Participants invariably answer “Smarties” but when the tube is opened, pencils unexpectedly appear (rather than the anticipated Smarties candies). Participants are then asked what someone else, such as a classmate, would predict is contained in the Smarties tube. The correct answer, which is Smarties candies (rather than pencils), requires assigning the correct mental state to someone else (namely, the false belief that the tube contains Smarties candies) and predicting a person's behavior on the basis of that assigned mental state (namely, that the person will say that they think Smarties are contained in the tube).

These false belief tests and other Theory of Mind tests are failed by many children before they turn four years old (Wellman et al., 2001), but there is significant variability among children. For example, many children on the autism spectrum fail to pass these tests even when they are several years older than four (Happé, 1995). Even among typically developing children, there is detectable variability, such as differences across cultures. For example, meta-analyses have revealed faster Theory of Mind development for children from mainland China, Canada, and the United States relative to children from Hong Kong (Liu et al., 2008), and for children from Australia and Canada relative to children from Austria and Japan (Wellman et al., 2001), differences that are thought to be related to certain environmental factors, such as the child's linguistic environment. These cultural differences in the rate of Theory of Mind development suggest that Theory of Mind is malleable and could potentially be facilitated by a dual-language (i.e., bilingual) environment.

Consistent with this line of thinking, previous studies have provided evidence that bilingualism accelerates Theory of Mind development (Goetz, 2003; Farhadian et al., 2010; Han and Lee, 2013; Diaz and Farrar, 2017). For example, Kovács (2009) found that more than twice as many 2 and 3 year-old Romanian-Hungarian bilingual children passed an unexpected-transfer test than intelligence-matched 2 and 3 year-old Romanian monolingual children.

There are three main accounts for why bilingual children might pass Theory of Mind tests earlier than monolinguals: the “executive functioning” account (Goetz, 2003; Bialystok and Senman, 2004; Kovács, 2009; Greenberg et al., 2013), the “metalinguistic awareness” account (Goetz, 2003; Diaz and Farrar, 2017), and the “socio-pragmatic” account (Goetz, 2003; Fan et al., 2015).

The first account, “executive functioning,” is based on evidence that bilingualism improves executive functioning (Carlson and Meltzoff, 2008; Bialystok and Viswanathan, 2009) and that level of executive functioning is a significant predictor of Theory of Mind performance (Devine and Hughes, 2014). The supposed enhanced attentional control abilities of bilinguals could be used to down-regulate their own mental state (i.e., their own beliefs and knowledge) while up-regulating someone else's mental state. The second account, “metalinguistic awareness,” is based on evidence that bilingualism enhances metalinguistic awareness (Ben-Zeev, 1977; Bialystok, 1988) and that metalinguistic awareness is linked to Theory of Mind development (Doherty and Perner, 1998; Doherty, 2000). Bilinguals' metalinguistic understanding that there are two labels for the same concept (i.e., one label in each language) might facilitate the understanding that two people can have a different mental state in relation to the same event (and thus that someone else's mental state can differ from their own). The third account, “socio-pragmatic,” is that bilinguals come to understand that some people speak only one of their languages (either language A or language B) and some people speak both of their languages (languages A and B). This understanding that two people can have different (or similar) language knowledge may transfer to the more general understanding that two people can have a different (or similar) mental state.

All three of these accounts predicts a bilingual advantage in Theory of Mind development. This prediction has received support both from studies that have used traditional false belief tests, such as the unexpected-location and unexpected-contents tests (Goetz, 2003; Kovács, 2009; Farhadian et al., 2010), as well as studies that have used non-traditional Theory of Mind tests, such as tests that assess the ability to take someone else's visual-spatial perspective when it differs from one's own visual-spatial perspective (Greenberg et al., 2013; Fan et al., 2015). In contrast, several other studies have failed to find a bilingual advantage, both on traditional false belief tests (Kyuchukov and De Villiers, 2009; Pearson, 2013; Nguyen and Astington, 2014; Gordon, 2016; Dahlgren et al., 2017) and non-traditional Theory of Mind tests (Gordon, 2016; Dahlgren et al., 2017).

The inconsistent results across individual studies make it difficult to draw a conclusion about the effects of bilingualism on Theory of Mind development. To help draw a conclusion, the current study statistically combined data from many studies through a meta-analysis. Specifically, a main analysis was conducted, which involved aggregating raw Theory of Mind scores across studies that have compared bilingual and monolingual children on Theory of Mind tests. A secondary analysis was then conducted on the subset of these studies that reported Theory of Mind scores that were statistically adjusted to account for a bilingual disadvantage in language proficiency. It has been argued that bilinguals' lower receptive language proficiency hurts their performance on language-based Theory of Mind tests, thereby concealing a bilingual advantage that would have otherwise emerged (Chan, 2004; Nguyen and Astington, 2014; Diaz and Farrar, 2017, 2018). Thus, the current study presents a main meta-analysis on raw Theory of Mind scores and a secondary meta-analysis on language-adjusted Theory of Mind scores.

Method

Literature search

To identify eligible studies, a three-step process was planned. First, a search through the databases PsycARTICLES, PsycINFO, and MEDLINE was to be conducted using the search terms “bilingual,” “Theory of Mind,” and “false belief.” Second, after identifying eligible articles through the database search, the reference lists of these eligible studies were to be scanned for additional studies that might not have been detected in the database search (i.e., cited studies were to be searched). Third, after eligible articles were identified through both the database search and the reference list search, the studies that cited these eligible studies were to be checked for eligibility (i.e., cited-by studies were to be searched). (Then, in a re-iterative process, the reference lists of the studies identified in the second step and the reference lists and citations of the studies identified in the third step were to be checked.) After completing the search plan in March-May of 2018, a total of 2,032 studies had been considered (though a small subset were duplicates), of which 16 satisfied the inclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

To be eligible for inclusion, a study had to satisfy the following requirements: the study (1) tested bilinguals and monolinguals, (2) tested children rather than adults, (3) tested spoken language users rather than sign language users, and (4) tested participants on a valid Theory of Mind test1. Included studies also provided sufficient data to compute an effect size and were reported in a journal (k = 13) or a dissertation (k = 3).

The 16 studies that were included in the main analysis (i.e., the analysis of raw Theory of Mind scores) are shown in Table 1. (Note that the order of the studies in the table was arranged to duplicate the order in Figure 1.) Collectively, the 16 studies tested 1,283 participants (655 monolinguals, 628 bilinguals). A subset of these studies (k = 8) was included in a secondary analysis (i.e., the analysis of language proficiency adjusted Theory of Mind scores). This secondary analysis used studies that reported Theory of Mind data that were statistically adjusted to account for the confounding variable of bilinguals' reduced language proficiency. These 8 studies, which included 569 participants (311 monolinguals, 258 bilinguals), are marked with an asterisk in Table 1.

Table 1

| Monolingual N | Bilingual N | Monolingual languages | Bilingual languages | Theory of Mind Tests | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diaz and Farrar, 2018* | 33 | 32 | English | English & Spanish | Unexpected-Transfer, Unexpected-Contents, Other |

| Kyuchukov and De Villiers, 2009a | 60 | 60 | Bulgarian | Bulgarian & Romani | Unexpected-Transfer, Unexpected-Contents |

| Pearson, 2013 | 40 | 28 | English | English & Spanish | Unexpected-Transfer |

| Bialystok and Senman, 2004*b | 52 | 43 | English | English & Other | Other |

| Gordon, 2016*c | 26 | 26 | English | English & Spanish | Unexpected-Transfer, Unexpected-Contents, Other |

| Dahlgren et al., 2017 | 14 | 14 | Swedish or Slavic | Swedish & Slavic | Unexpected-Transfer, Other |

| Nguyen and Astington, 2014* | 48 | 24 | English or French | English & French | Unexpected-Transfer, Unexpected-Contents |

| Diaz and Farrar, 2017*d | 35 | 38 | English | English & Spanish | Unexpected-Transfer, Unexpected-Contents, Other |

| Kovács, 2009e | 28 | 28 | Italian | Romanian & Slovenian | Unexpected-Transfer, Unexpected-Contents |

| Chan, 2004* | 29 | 31 | English | English & Chinese | Unexpected-Transfer, Unexpected-Contents, Other |

| Goetz, 2003* | 64 | 40 | English or Chinese | English & Chinese | Unexpected-Transfer, Unexpected-Contents, Other |

| Han and Lee, 2013 | 60 | 73 | Korean | English & Korean | Other |

| Greenberg et al., 2013 | 45 | 37 | English | English & Other | Other |

| Kovács, 2009 | 32 | 32 | Romanian | Romanian & Hungarian | Unexpected-Transfer, Other |

| Farhadian et al., 2010 | 65 | 98 | Persian | Persian & Kurdish | Unexpected-Transfer, Unexpected-Contents |

| Fan et al., 2015* | 24 | 24 | English | English & Other | Other |

Studies included in main analysis.

The study was included in the secondary analysis

Bilinguals were tested in both their L1 and L2. The L1 test scores were used to compute the effect size so that Theory of Mind scores for both monolinguals and bilinguals were based on their native language performance.

In the secondary analysis, only the appearance results of the appearance-reality test were used to compute an effect size because the reality questions did not require a Theory of Mind.

Gordon's dissertation Millett, 2010 was used to extract additional data that were not included in the journal version.

A subset of participants was tested a second time but for a more accurate statistical calculation only time 1 data were included in the effect size calculation.

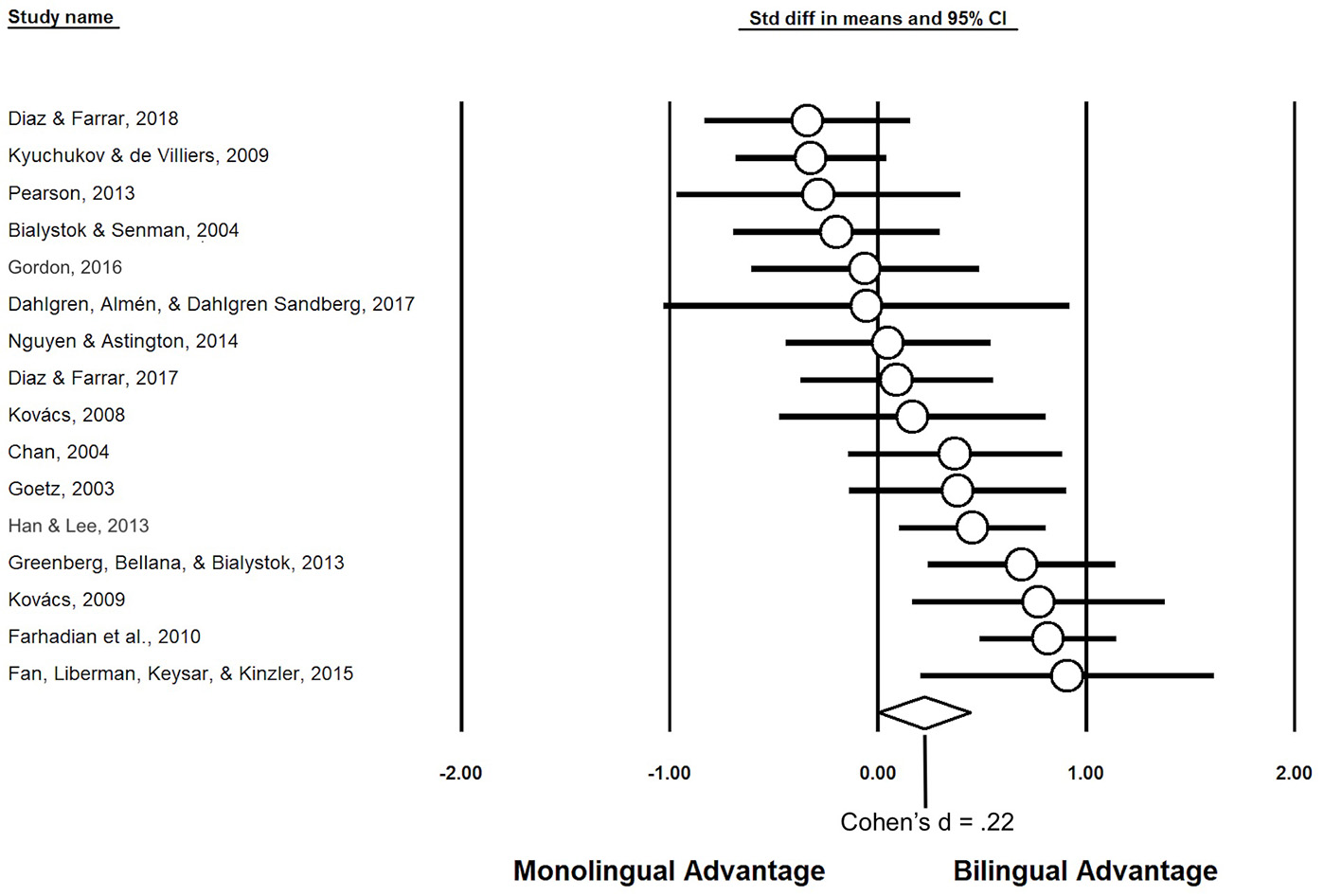

Figure 1

A plot of effect sizes for each of the 16 studies in the main analysis, with the summary effect size of 0.22 at the bottom.

Most of the studies in the meta-analyses used a version of the unexpected-location or unexpected-transfer false belief test, but some studies used non-traditional Theory of Mind tests (see Table 1; Greenberg et al., 2013; Han and Lee, 2013; Fan et al., 2015). Additionally, most of the studies tested English-speaking monolinguals and bilinguals, but some tested non-English speakers (see Table 1; Kovács, 2008, 2009; Kyuchukov and De Villiers, 2009; Farhadian et al., 2010; Dahlgren et al., 2017). Furthermore, most of the studies tested children between the ages of 3 and 5, but there were some exceptions (Greenberg et al., 2013; Fan et al., 2015; Dahlgren et al., 2017).

Statistical analyses

For both the main and secondary analyses, Cohen's d, also known as the Standardized Difference in Means, was used as the effect size measure (Cohen, 1992). The main analysis used raw means and variances to compute Cohen's d, whereas the secondary analysis used statistically adjusted means and variances (typically from an Analysis of Covariance) to compute Cohen's d. When a study used multiple Theory of Mind tests, the effect sizes were pooled together to create a single grand effect size for each study. The Cohen's d effect sizes were entered into a random-effects model. The computing of the effect sizes and the running of the random-effects model were performed in the software Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (Borenstein et al., 2005).

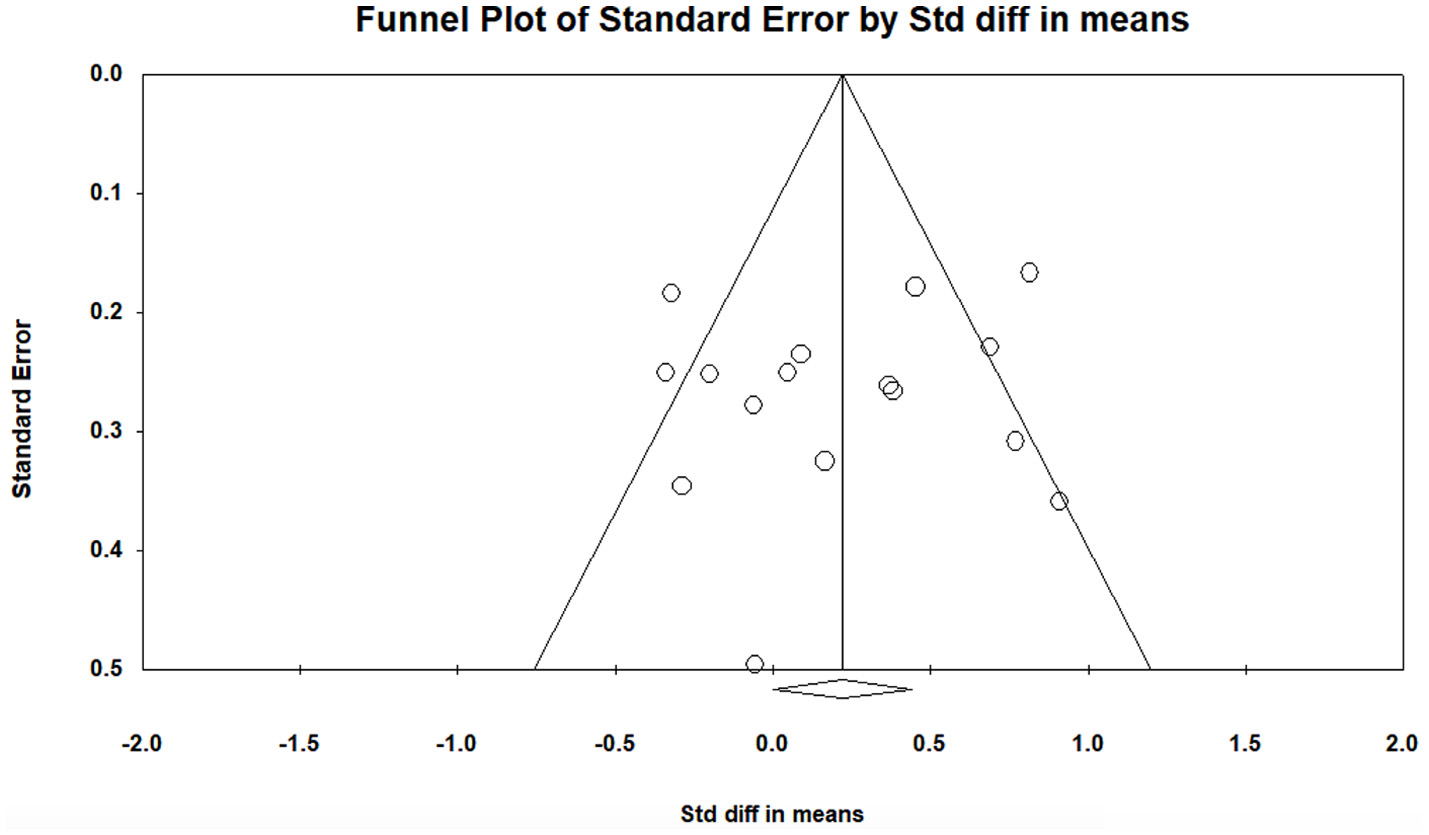

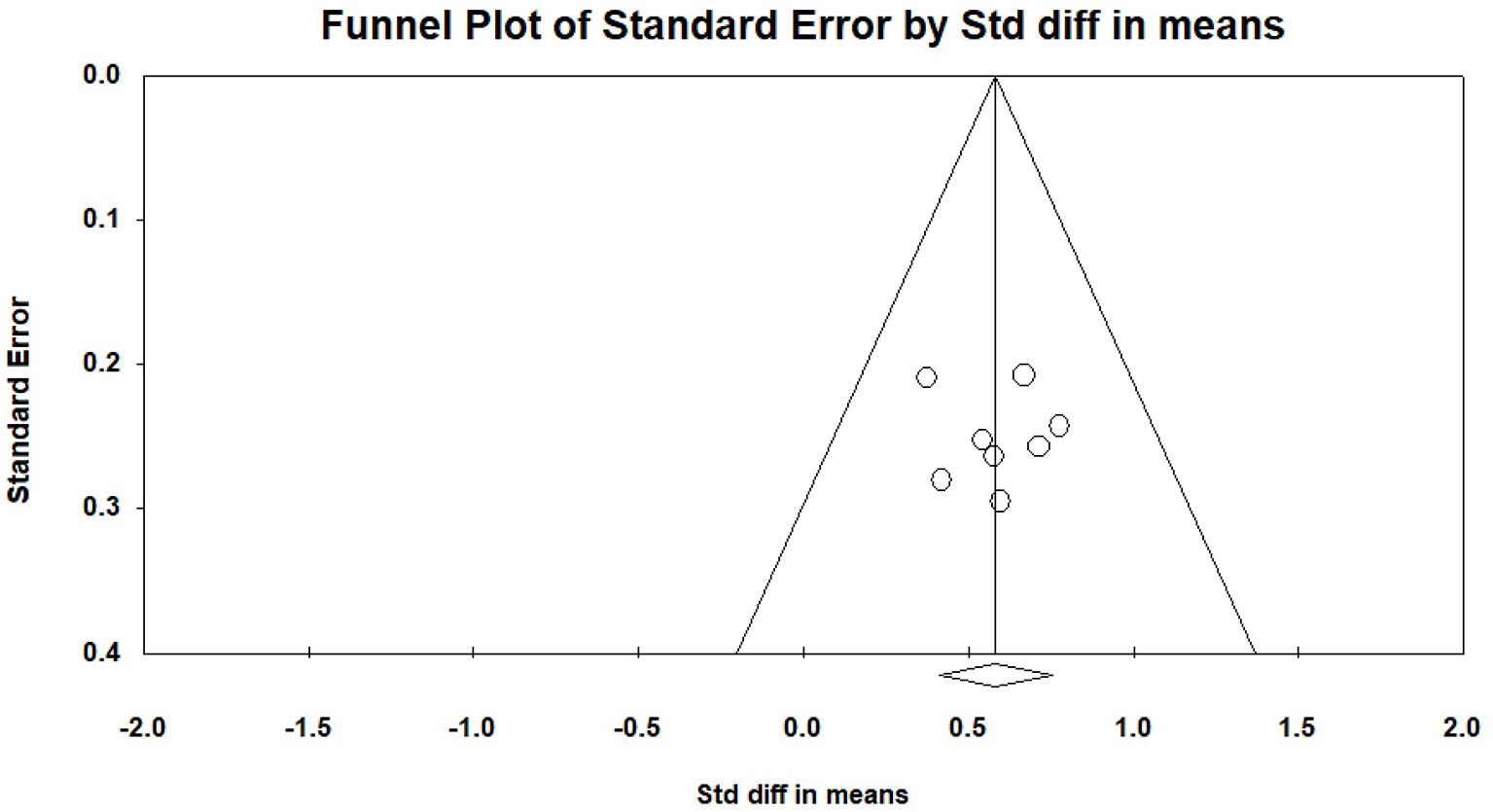

In addition to analyses of effect sizes, potential publication bias was also examined. To this end, a funnel plot with effect sizes and standard errors was visually inspected for symmetry. Following visual inspection, Egger's regression intercept test (Egger et al., 1997) was conducted. The software Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (Borenstein et al., 2005) was used to complete the tests of potential publication bias.

Results

Main analysis: raw scores

The meta-analysis of raw Theory of Mind scores from the 16 studies indicated a small bilingual advantage, Cohen's d = 0.22, p = 0.050, z = 1.96, SE = 0.11, 95% Confidence Interval = 0.00-0.44. A plot of the effect sizes for each of the 16 studies and the summary effect size (Cohen's d = 0.22) is displayed in Figure 1.

To assess the possibility of publication bias, a funnel plot was generated. See Figure 2 for the plot. There is no apparent asymmetry in the plot, suggestive of no publication bias. Confirming the lack of publication bias, the Eggers regression intercept test was not significant, t(14) = 0.65, p = 0.53.

Figure 2

A funnel plot to assess potential publication bias in the main analysis.

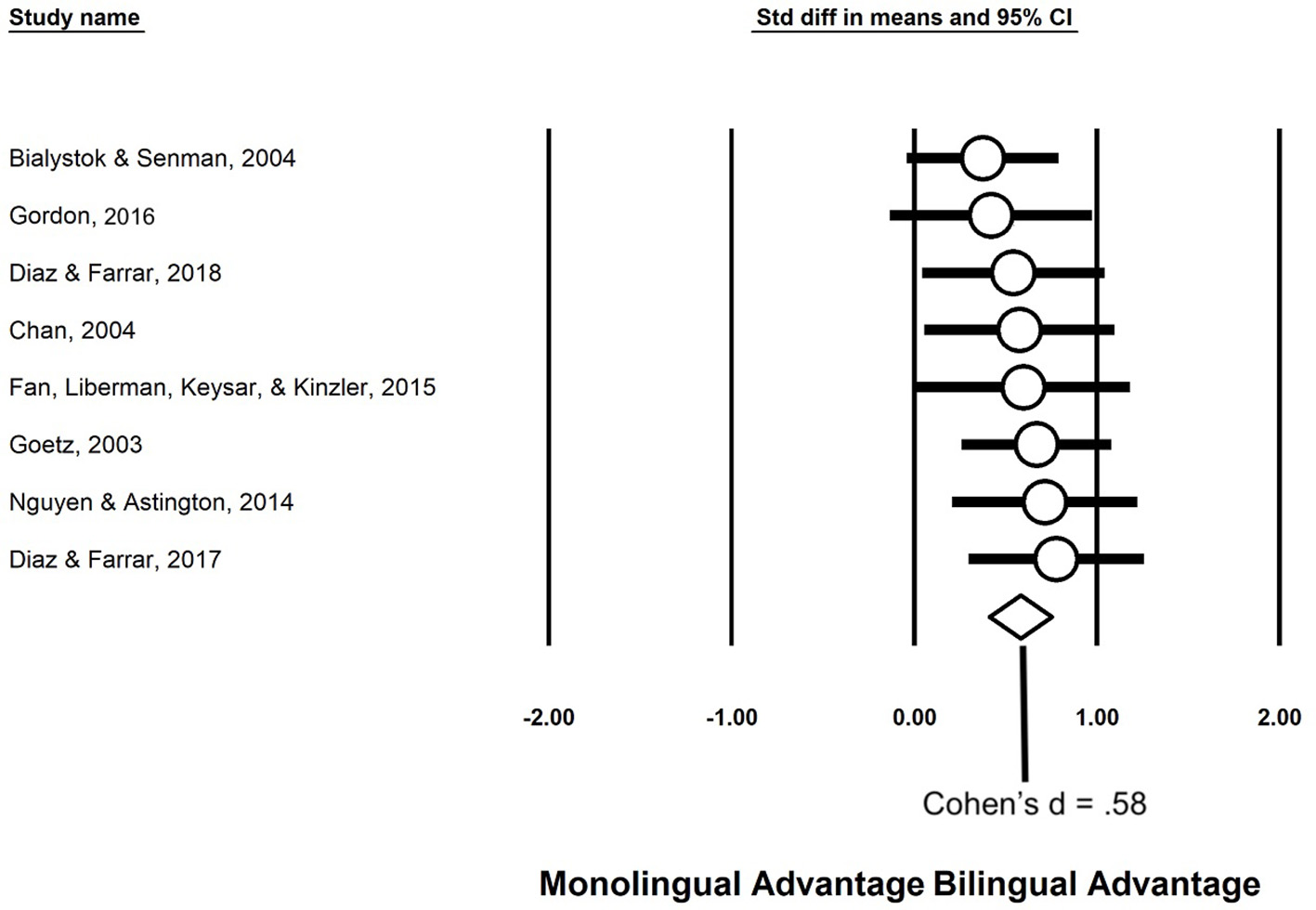

Secondary analysis: language proficiency adjusted scores

The secondary meta-analysis was conducted on the 8 studies that reported Theory of Mind scores that were adjusted for bilingual-monolingual differences in language proficiency. This analysis indicated a medium-size bilingual advantage, Cohen's d = 0.58, p < 0.001, z = 6.70, SE = 0.09, 95% Confidence Interval = 0.41–0.75. See Figure 3 for a plot of the effect sizes.

Figure 3

A plot of effect sizes for each of the 8 studies in the secondary analysis, with the summary effect size of .58 at the bottom.

A funnel plot, which is displayed in Figure 4, was created to check for potential publication bias. There is no obvious asymmetry in the plot, implying no publication bias. Eggers regression intercept test also indicated no publication bias, as the test was not significant, t(6) = 0.17, p = 0.87.

Figure 4

A funnel plot to assess potential publication bias in the secondary analysis.

Discussion

The main meta-analysis, which compared bilingual and monolingual children's raw Theory of Mind scores, revealed a small bilingual advantage. The size of this bilingual-monolingual difference (i.e., a Cohen's d in the “small” range) is similar to the effect of early education interventions on cognitive, school, and social outcomes (Camilli et al., 2010). The secondary meta-analysis, which used transformed Theory of Mind scores that were adjusted for language proficiency, revealed a medium-size bilingual advantage. This secondary analysis, however, should be interpreted with caution, given that these studies may have violated assumptions of the Analysis of Covariance (Miller and Chapman, 2001; Paap et al., 2015). Even with skepticism for the secondary analysis, the main analysis provides evidence that acquiring two languages helps Theory of Mind development.

This meta-analytical finding of a bilingual advantage would have less validity if evidence for publication bias had been found. Indeed, in the high-profile meta-analysis by de Bruin et al. (2015), a bilingual advantage in executive functioning was revealed, but so was a publication bias. Using the same method as de Bruin et al. (i.e., the Eggers test), there was no evidence for publication bias in either the main analysis or the secondary analysis.

While the current study indicates a bilingual advantage in Theory of Mind, it does not address the reasons why. In the Introduction, three accounts for why bilinguals might have an advantage in mental state reasoning were laid out—i.e., the “executive functioning” account, the “metalinguistic awareness” account, and the “socio-pragmatic” account. Though future research is needed to determine the relative contributions of these accounts and others, some of the studies included in this meta-analysis provide germane preliminary evidence. Regarding the “executive functioning” account, evidence for this account comes from the Kovács (2008) finding that a bilingual advantage emerges when the Theory of Mind test has high inhibitory demands but not when it has low inhibitory demands. However, evidence against this account comes from several other studies that have found that measures of executive functioning (such as the dimensional change card sorting test) do not statistically mediate the bilingual advantage in Theory of Mind (Nguyen and Astington, 2014; Fan et al., 2015; Diaz and Farrar, 2017, 2018). Regarding the “metalinguistic awareness” account, Diaz and Farrar (2017) and Chan (2004) found that measures of metalinguistic awareness (such as symbol substitution, synonym judgment, and homonym selection) statistically mediate the bilingual advantage. Regarding the “socio-pragmatic” account, while there is no statistical mediation evidence, Fan et al. (2015) found a Theory of Mind advantage in children who were not bilingual but were exposed to a second language. The performance by these children suggests that Theory of Mind may be augmented by learning that one's linguistic knowledge can be different from that of other people.

Regardless of the source, this bilingual advantage is likely to have meaningful real-world consequences. On the one hand, an enhanced Theory of Mind may help in the development of prosocial behavior. For example, a recent meta-analysis of 20 studies revealed that children who scored higher on Theory of Mind tests were more popular among their peers (Slaughter et al., 2015). On the other hand, negative effects of an enhanced Theory of Mind are possible. For instance, a recent study found that Theory of Mind training led honest children to begin lying (Ding et al., 2015).

In sum, the current study took a meta-analytical approach to the question of whether learning two languages has a positive impact on mental state reasoning. The results indicated a small- or medium-size positive effect (depending on the analysis), an effect that may carry real-world implications for bilingual children's social competence. Though plausible accounts of this bilingual advantage have been put forward, future research is needed to determine more precisely why a dual-language environment is helpful for Theory of Mind development.

Statements

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and approved it for publication.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Viorica Marian and the Northwestern Bilingualism and Psycholinguistics Research Group for helpful discussions of this topic.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

1.^ Two studies (Berguno and Bowler, 2004; Yow and Markman, 2015) did not use a measure of Theory of Mind that was deemed valid for the current purpose and were thus not included in the meta-analysis. Berguno and Bowler (2004) did not use any Theory of Mind tests that assessed the attribution of mental states to others (only to oneself). Because this study did not assess the key component of Theory of Mind, it was not included in the meta-analysis. Yow and Markman (2015) used a word learning test that included a Theory of Mind component. Because there is evidence for a bilingual advantage in word learning (Kaushanskaya et al., 2014), better performance on the word learning test might not reflect a bilingual advantage in Theory of Mind per se. Due to this confound, this study was not included in the meta-analysis. It is important to note, however, that the results of both of these studies were consistent with the results of the meta-analysis (i.e., a bilingual advantage).

References

1

Antón E. Duñabeitia J. A. Estévez A. Hernández J. A. Castillo A. Fuentes L. J. et al . (2014). Is there a bilingual advantage in the ANT task? Evidence from children. Front. Psychol.5:398. 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00398

2

Bak T. H. (2016). Cooking pasta in La Paz. Linguisti. Approach. Bilingualism. 6, 699–717. 10.1075/lab.16002.bak

3

Baron-Cohen S. Leslie A. M. Frith U. (1985). Does the autistic child have a “theory of mind?”Cognition21, 37–46.

4

Ben-Zeev S. (1977). The influence of bilingualism on cognitive strategy and cognitive development. Child Dev.48, 1009–1018. 10.2307/1128353

5

Berguno G. Bowler D. M. (2004). Communicative interactions, knowledge of a second language, and theory of mind in young children. J. Genet. Psychol.165, 293–309. 10.3200/GNTP.165.3.293-309

6

Bhattacharjee Y. (2012). The benefits of bilingualism. Available online at: https://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/18/opinion/sunday/the-benefits-of-bilingualism.html

7

Bialystok E. (1988). Levels of bilingualism and levels of linguistic awareness. Dev. Psychol.24, 560–567. 10.1037/0012-1649.24.4.560

8

Bialystok E. (1999). Cognitive complexity and attentional control in the bilingual mind. Child Dev.70, 636–644. 10.1111/1467-8624.00046

9

Bialystok E. (2016). The signal and the noise. Linguisti. Approaches Bilingualism6, 517–534. 10.1075/lab.15040.bia

10

Bialystok E. Craik F. I. Klein R. Viswanathan M. (2004). Bilingualism, aging, and cognitive control: evidence from the Simon task. Psychol. Aging19:290. 10.1037/0882-7974.19.2.290

11

Bialystok E. Senman L. (2004). Executive processes in appearance-reality tasks: the role of inhibition of attention and symbolic representation. Child Dev.75, 562–579. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00693.x

12

Bialystok E. Viswanathan M. (2009). Components of executive control with advantages for bilingual children in two cultures. Cognition112, 494–500. 10.1016/j.cognition.2009.06.014

13

Borenstein M. Hedges L. Higgins J. Rothstein H. (2005). Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Version 2. Englewood, NJ: Biostat.

14

Camilli G. Vargas S. Ryan S. Barnett W. S. (2010). Meta-analysis of the effects of early education interventions on cognitive and social development. Teach. Coll. Rec.112, 579–620.

15

Carlson S. M. Meltzoff A. N. (2008). Bilingual experience and executive functioning in young children. Dev. Sci.11, 282–298. 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00675.x

16

Chan K. T. (2004). Chinese-English Bilinguals' Theory-of-Mind Development, Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, University of Toronto, Toronto, CA.

17

Cohen J. (1992). A power primer. Psychol. Bull.112, 155–159. 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155

18

Costa A. Hernández M. Sebastián-Gallés N. (2008). Bilingualism aids conflict resolution: evidence from the ANT task. Cognition106, 59–86. 10.1016/j.cognition.2006.12.013

19

Dahlgren S. Almén H. Dahlgren Sandberg A. (2017). Theory of mind and executive functions in young bilingual children. J. Genet. Psychol.178, 303–307. 10.1080/00221325.2017.1361376

20

de Bruin A. Treccani B. Della Sala S. (2015). Cognitive advantage in bilingualism: an example of publication bias?Psychol. Sci.26, 99–107. 10.1177/0956797614557866

21

Devine R. T. Hughes C. (2014). Relations between false belief understanding and executive function in early childhood: a meta-analysis. Child Dev.85, 1777–1794. 10.1111/cdev.12237

22

Diaz V. Farrar M. J. (2017). The missing explanation of the false-belief advantage in bilingual children: a longitudinal study. Dev. Sci.21:e12594. 10.1111/desc.12594

23

Diaz V. Farrar M. J. (2018). Do bilingual and monolingual preschoolers acquire false belief understanding similarly? The role of executive functioning and language. First Lang. 38, 382–398. 10.1177/0142723717752741

24

Ding X. P. Wellman H. M. Wang Y. Fu G. Lee K. (2015). Theory-of-mind training causes honest young children to lie. Psychol. Sci.26, 1812–1821. 10.1177/0956797615604628

25

Doherty M. Perner J. (1998). Metalinguistic awareness and theory of mind: just two words for the same thing?Cogn. Dev.13, 279–305.

26

Doherty M. J. (2000). Children's understanding of homonymy: metalinguistic awareness and false belief. J. Child Lang.27, 367–392. 10.1017/S0305000900004153

27

Egger M. Davey Smith G. Schneider M. Minder C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Br. Med. J.315, 629–634.

28

Fan S. P. Liberman Z. Keysar B. Kinzler K. D. (2015). The exposure advantage: early exposure to a multilingual environment promotes effective communication. Psychol. Sci.26, 1090–1097. 10.1177/0956797615574699

29

Farhadian M. Abdullah R. Mansor M. Redzuan M. Gazanizadand N. Kumar V. (2010). Theory of mind in bilingual and monolingual preschool children. J. Psychol.1, 39–46. 10.1080/09764224.2010.11885444

30

Goetz P. J. (2003). The effects of bilingualism on theory of mind development. Bilingualism Lang. Cogn.6, 1–15. 10.1017/S1366728903001007

31

Gordon K. R. (2016). High proficiency across two languages is related to better mental state reasoning for bilingual children. J. Child Lang.43, 407–424. 10.1017/S0305000915000276

32

Greenberg A. Bellana B. Bialystok E. (2013). Perspective-taking ability in bilingual children: extending advantages in executive control to spatial reasoning. Cogn. Dev.28, 41–50. 10.1016/j.cogdev.2012.10.002

33

Han S. Lee K. (2013). Cognitive and affective perspective-taking ability of young bilinguals in South Korea. Child Stud. Div. Contexts3, 69–80. 10.5723/csdc.2013.3.1.069

34

Happé F. G. (1995). The role of age and verbal ability in the theory of mind task performance of subjects with autism. Child Dev.66, 843–855. 10.2307/1131954

35

Hogrefe G. Wimmer H. Perner J. (1986). Ignorance versus false belief: a developmental lag in attribution of epistemic states. Child Dev.57, 567–582. 10.2307/1130337

36

Kaushanskaya M. Gross M. Buac M. (2014). Effects of classroom bilingualism on task-shifting, verbal memory, and word learning in children. Dev. Sci.17, 564–583. 10.1111/desc.12142

37

Kovács Á. M. (2008). Learning Two Languages Simultaneously: Mechanisms Recruited for Dealing With a Mixed Linguistic Input. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, SISSA, Trieste.

38

Kovács A. M. (2009). Early bilingualism enhances mechanisms of false-belief reasoning. Dev. Sci.12, 48–54. 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00742.x

39

Kyuchukov H. De Villiers J. (2009). Theory of mind and evidentiality in romani-bulgarian bilingual children. Psychol. Lang. Commun.13, 21–34. 10.2478/v10057-009-0007-4

40

Liu D. Wellman H. M. Tardif T. Sabbagh M. A. (2008). Theory of mind development in Chinese children: a meta-analysis of false-belief understanding across cultures and languages. Dev. Psychol.44:523. 10.1037/0012-1649.44.2.523

41

Miller G. A. Chapman J. P. (2001). Misunderstanding analysis of covariance. J. Abnorm. Psychol.110, 40–48. 10.1037/0021-843X.110.1.40

42

Millett K. R. G. (2010). The Cognitive Effects of Bilingualism: Does Knowing Two Languages Impact Children's Ability to Reason about Mental States?. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

43

Morton J. B. Harper S. N. (2007). What did Simon say? revisiting the bilingual advantage. Dev. Sci. 10, 719–726. 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2007.00623.x

44

Nguyen T.-K. Astington J. W. (2014). Reassessing the bilingual advantage in theory of mind and its cognitive underpinnings. Bilingualism Lang. Cogn.17, 396–409. 10.1017/S1366728913000394

45

Paap K. R. Greenberg Z. I. (2013). There is no coherent evidence for a bilingual advantage in executive processing. Cogn. Psychol.66, 232–258. 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2012.12.002

46

Paap K. R. Johnson H. A. Sawi O. (2015). Bilingual advantages in executive functioning either do not exist or are restricted to very specific and undetermined circumstances. Cortex69, 265–278. 10.1016/j.cortex.2015.04.014

47

Paap K. R. Johnson H. A. Sawi O. (2016). Should the search for bilingual advantages in executive functioning continue?Cortex74, 305–314. 10.1016/j.cortex.2015.09.010

48

Pearson D. K. (2013). Effect of Language Background on Metalinguistic Awareness and Theory of Mind. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Stirling, Scotland.

49

Perner J. Leekam S. R. Wimmer H. (1987). Three-year-olds' difficulty with false belief: the case for a conceptual deficit. Br. J. Dev. Psychol.5, 125–137.

50

Reville W. (2014). The Bilingual Brain Is More Nimble And Efficient. Available online at: https://www.irishtimes.com/news/science/the-bilingual-brain-is-more-nimble-and-efficient-1.1764064

51

Slaughter V. Imuta K. Peterson C. C. Henry J. D. (2015). Meta-analysis of theory of mind and peer popularity in the preschool and early school years. Child Dev.86, 1159–1174. 10.1111/cdev.12372

52

Titone D. Gullifer J. Subramaniapillai S. Rajah N. Baum S. (2017). “History-inspired reflections on the bilingual advantages hypothesis,” in Growing Old with Two Languages: Effects of Bilingualism on Cognitive Aging, eds E. Bialystok and M. D. Sullivan (Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing), 265–295.

53

Wellman H. M. Cross D. Watson J. (2001). Meta-analysis of theory-of-mind development: the truth about false belief. Child Dev.72, 655–684. 10.1111/1467-8624.00304

54

Wimmer H. Perner J. (1983). Beliefs about beliefs: representation and constraining function of wrong beliefs in young children's understanding of deception. Cognition13, 103–128.

55

Yow W. Q. Markman E. M. (2015). A bilingual advantage in how children integrate multiple cues to understand a speaker's referential intent. Bilingualism Lang. Cogn.18, 391–399. 10.1017/S1366728914000133

Summary

Keywords

bilingualism, Theory of Mind, false belief, executive functioning, cognitive development

Citation

Schroeder SR (2018) Do Bilinguals Have an Advantage in Theory of Mind? A Meta-Analysis. Front. Commun. 3:36. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2018.00036

Received

28 June 2018

Accepted

27 July 2018

Published

24 August 2018

Volume

3 - 2018

Edited by

Roberto Filippi, University College London, United Kingdom

Reviewed by

Ellen Bialystok, York University, Canada; Greg Poarch, Universität Münster, Germany

Updates

Copyright

© 2018 Schroeder.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Scott R. Schroeder scott.r.schroeder@hofstra.edu

This article was submitted to Language Sciences, a section of the journal Frontiers in Communication

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.