- 1Department of Art and Media, Federal University of Campina Grande, Campina Grande, Brazil

- 2Departments of Communication and of Science & Technology Studies, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, United States

- 3Independent Scholar, Brasilia, Brazil

Our case study situates science communication within the interaction of the COVID-19 disease, scientific research about the disease, public statements by relevant officials, media messages, political actions, and public opinion. By studying these interactions in the Brazilian context, we add to the understanding of science communication complexity by studying a context less easily available to the English-speaking research community. Methodologically, we identified key moments in Brazil during the pandemic using tools such as Google Trends, and content analysis of influencers' Twitter and Instagram accounts and digital newspapers. These episodes are then explored as case studies, using both quantitative and qualitative content analysis of messages to identify message emphasis frames and political agendas. The results introduce issues rarely explored in previous science communication research, especially ones associated with nationalism and political populism and national inequalities of privilege, income, and trust.

Introduction

Different countries have responded to the SARS-CoV-2 virus and COVID-19 pandemic in diverse ways. Many factors have affected how people have responded to the crisis, such as traditional and cultural habits, their level of trust in science, the statements of political leaders, influencers and media, and official health institution guidance. In order to understand these factors, we must first have a clear picture of who was presenting information, what information they were presenting, and how that information correlated with events and expressions of public opinion. This article seeks to establish those baselines for the case of Brazil.

Understanding the landscape of pandemic information is particularly important for understanding public communication of science because of the rapid changes in how information becomes available to public audiences—through news organizations, through pre-print and open-access publishing platforms, through direct education sites (such as TED talks), and especially through social media both as a tool for spreading all the other sources and as sites for discussion of those sources. Science communication is based on the idea that experts have knowledge to which publics need access in order to combine it with other information and with personal and national values in a process of making meaning (Gilbert and Stocklmayer, 2013). Yet various aspects of the pandemic have complicated the process of assessing what information comes from experts and the degree to which it should be trusted—aspects such as direct access to pre-prints, reduced time for experts to respond to public concerns (de Oliveira and de Oliveira, 2020), changing statements from trusted organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC), and in some countries the politicization of information about the pandemic.

Brazil has been one of the countries most damaged by the COVID-19 pandemic. During the pandemic, many Brazilians failed to take protective measures, despite scientific and public health consensus. Anecdotally, these failures appeared to be responses to several statements made by WHO officials and by the Brazilian president, Jair Bolsonaro. There were also demonstrations of disrespect by members of the financial and educational elite toward scientific and public health officers, health controllers, and peaceful protestors seeking greater public response.

This context allows us to explore a context too little studied in science communication research: a major industrialized country outside of North America and Europe. For this analysis, we have chosen to use the concept of “emphasis framing” (Scheufele and Iyengar, 2015). Importantly, we have taken note of recent critiques attempting to clarify the theoretical meaning and use of framing (Cacciatore et al., 2016). We are not claiming that emphasis frames lead directly to public responses (media effects). We are focused on describing those frames as they were produced by multiple sources, following D'Angelo and Kuypers (2010, p. 5) who “regard frames as embedded in a web of culture, an image that naturally draws attention to the surrounding cultural context and the threads that connect them.”

Our definition of emphasis frames addresses the wide range of sources that produce information about the virus and the pandemic, ranging from individual scientists, to research institutes, to science-based national and international government agencies (such as WHO and local public health organizations), to political, economic, and social leaders. We follow Reese (2001, p. 11), defining emphasis frames as “organizing principles that are socially shared and persistent over time, that work symbolically to meaningfully structure the social world.” This definition suggests that emphasis frames manifest themselves in a number of different sites and across a number of domains, including policy, journalism, and public expression (D'Angelo and Kuypers, 2010).

For this study, we begin with a qualitative identification of events in Brazil that have impacted the society because of their political and cultural appeal during the COVID-19 pandemic. In examining this series of episodes in Brazil, we expect to see particularly the interweaving of emphasis frames and political agendas. We hypothesize that various elements of national culture (such as patriarchal expectations) and political ideology (such as populism) will appear frequently in both official and media messages. We will be especially observant of messages linked with misinformation, political oppression, and science denial.

Because our analysis seeks to link emphasis frames with aspects of Brazilian culture, we need to introduce key aspects of Brazilian history that have been identified by historians, anthropologists, sociologists, and other social scientists. Invaded (not discovered) in 1500 C.E. Brazil carries in its roots the structure of a Portuguese colonial and agrarian society based on economical exploitation and slavery—first subjugating indigenous people and later afrodescendents—when “the masters (…) in exercise of a political or administrative elevated position had the simple and pure violent and perverse taste of command” (Freyre, 1980, p. 54). After the abolishment of slavery was declared—but not strictly implemented—the focus of the economy switched from rural areas to urban ones. And with this change, the Big House mentality entered the cities1. “Stereotyped by long years of rural life, the mentality of the big house thus invaded the cities and conquered all professions, without excluding the most humble” (Holanda, 1969, p. 55, 56).

Today, “the rigid social hierarchy and the monopoly of information, in the hands of a few, explain[s] the arrogance and authoritarianism of the ruling class” (de Sousa et al., 2020, p. 23). This elite perspective dominates public discourse, even as people beyond the elites gain political power. As Freire (2014, p. 44) indicates, when there is not liberating education, the oppressed want to become in turn oppressors.

A few other key issues in thinking about Brazil: Inequality is extreme—in 2019, the poorest 10% had <1% of the monthly household income per capita, while the richest 10% had 43% of the household income. The income of the population's richest 1% was more than 33 times greater than that of the poorest half (IBGE—Agência de Notícias, 2019)2. The situation has gotten worse in recent years: According to a recent study, Brazil in 2019 dropped five positions in the Human Development Index ranking3. These economic issues have a direct effect on the course of the pandemic in Brazil: “The poorest 20% of the population had twice the risk [of infection] than the richest 20%—even though the pandemic arrived in Brazil through airports, by people of higher socioeconomic status” (Hallal et al., 2020). As mentioned, Brazil in 1888 was the last country in the western world to abolish slavery—in theory—but in practice it still exists: From 1995 to 2020, according to the Ministry of Labor of Brazil (2020), 55,004 workers were released from contemporary slave labor in the country. Thus, the social structure of elites controlling parts of the population is part of the culture. This also connects to issues of violence: Although overall violence in Brazil is about average for countries worldwide, homicides in particular are very high, reinforcing images as a violent crime-ridden country (Muggah and Aguirre Tobón, 2018; Cerqueira and Bueno, 2020). In 2019, women held only 15% of parliamentary positions (Women in Parliaments: World Classification, 2019). Among the 50 most important national media outlets in Brazil (TV, radio, print, and Internet), 31 belong to just eight groups. “The media system indicates high concentration of audience and ownership, high geographic concentration, lack of transparency, besides religious, political and economical interference” (Reporters Without Borders, 2020).

Many factors have contributed to one of the most chaotic national responses to the new coronavirus. As of December 2020, Brazil occupied the third position in absolute confirmed cases, second in number of deaths, and ninth in deaths per 100,000 population4. We do not claim that specific media emphasis frames led to this chaos. But we suspect that patterns in those frames help us understand the ways the Brazilian population responded to political leaders' statements, to protests intended to raise awareness of social distancing or the use of masks, and to how official statements have been misinterpreted to favor science denial “arguments.” To assess these issues, we pose the following questions:

1) How did traditional and social media address the importance of following health measures toward COVID-19?

2) What kinds of different emphasis frames appear in main media outlets, especially from key or influential actors during the pandemic?

Materials and Methods

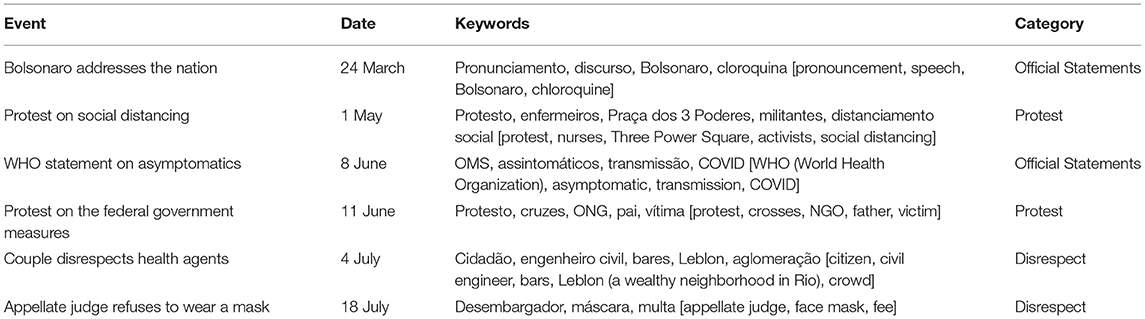

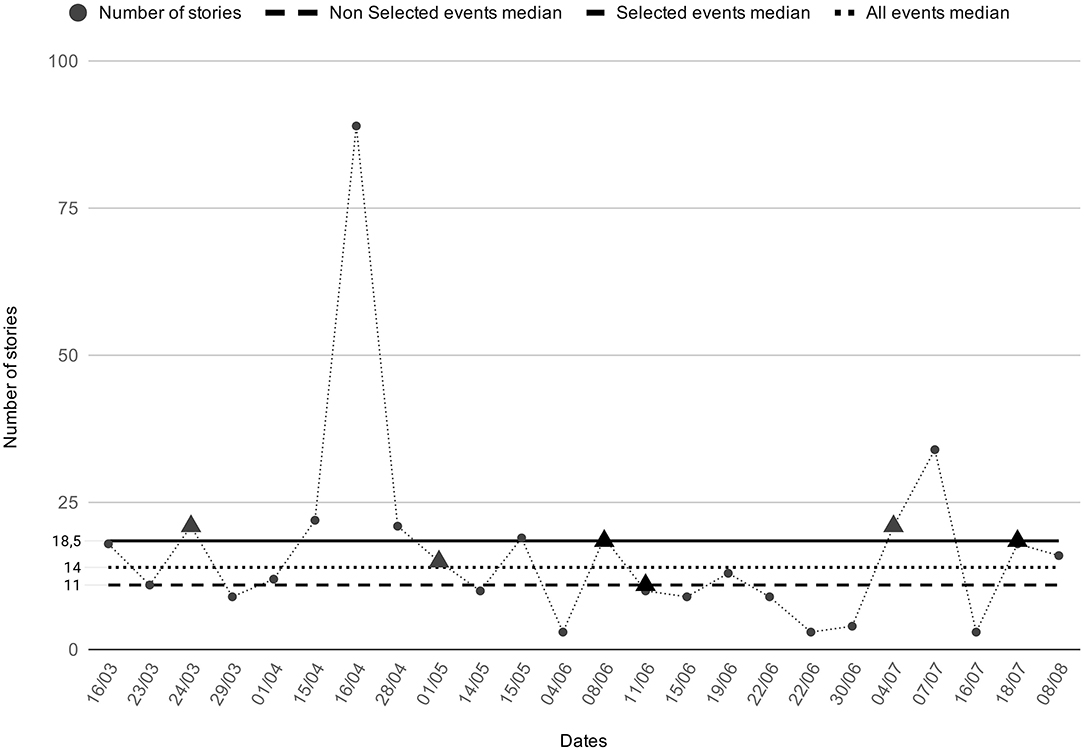

Our study draws primarily on qualitative methods, though we also use quantitative data as one dimension of our understanding of the context. First, we identified from our own experience as dedicated (even obsessive!) media-watchers more than 20 events during the period March-August 2020 (in practical terms, the first 6 months of the pandemic's presence in Brazil) that stood out as important moments in the Brazilian context (see Supplementary Material for full list). We then collected the number of news stories about those events appearing in the three main traditional newspapers in Brazil—Folha de São Paulo, O Globo, and O Estado de São Paulo—using the official database from each newspaper. Acting on the methodological principle that controversies reveal strains in social processes that are usually hidden (Bartlett, 2019), we identified six events (Table 1) that both stood out as being above the median number of overall articles (Figure 1) and also where the media stories went beyond simply reporting of events—the six events had some element of controversy or disagreement that was part of the public discussion. We focused our more detailed case studies on those six events, which we classified in three categories: statements by political leaders or institutions; major protests; and attacks on public health and civil agents.

Figure 1. Media references to 24 key events regarding the pandemic in Folha de São Paulo, O Globo, and O Estado de São Paulo, March–August 2020. Overall median is 14 stories; median for stories about six selected events (marked with triangles) is 18.5, median for all other stories is 11.5.

For each of the six events, we collected: number of keyword searches on Google related to each event (using Google Trends); posts on Twitter and Instagram from media influencers addressing the events; and also the news stories we had already collected from the three main traditional newspapers in Brazil. To identify influencers or key people, we used a report ordered by the Brazilian Government from a communication company in which 81 professors, influencers and journalists were ranked as “detractors,” “neutral,” or “favorable” [to the Government]5. We complemented the list with another 75 profiles identified by the Ideological GPS based on a methodology proposed by Barberá et al. (2015)6. We downloaded the social media content on Twitter and Instagram from these influencers, creating a textual database with 580,629 posts. From this database, we identified 361 items related to the six key events, using the same event keywords to identify the influencers' content. The items generated 2,045,740 “likes,” with similar patterns of engagement on Twitter and Instagram.

Overall our goal was to understand the ways that traditional and social media were used to discuss the pandemic and potential vaccines. Thus, we read qualitatively to identify the main topics—politics, science, national focus, worldwide pandemic, danger, hope, and so on. We also identified more specific frames such as national culture (patriarchal expressions), and political ideology (populism). We did not use formal coding or grounded theory to identify the topics and frames.

Results

Political Leader Provides Guidance and Disinformation Based on World Health Organization Statement

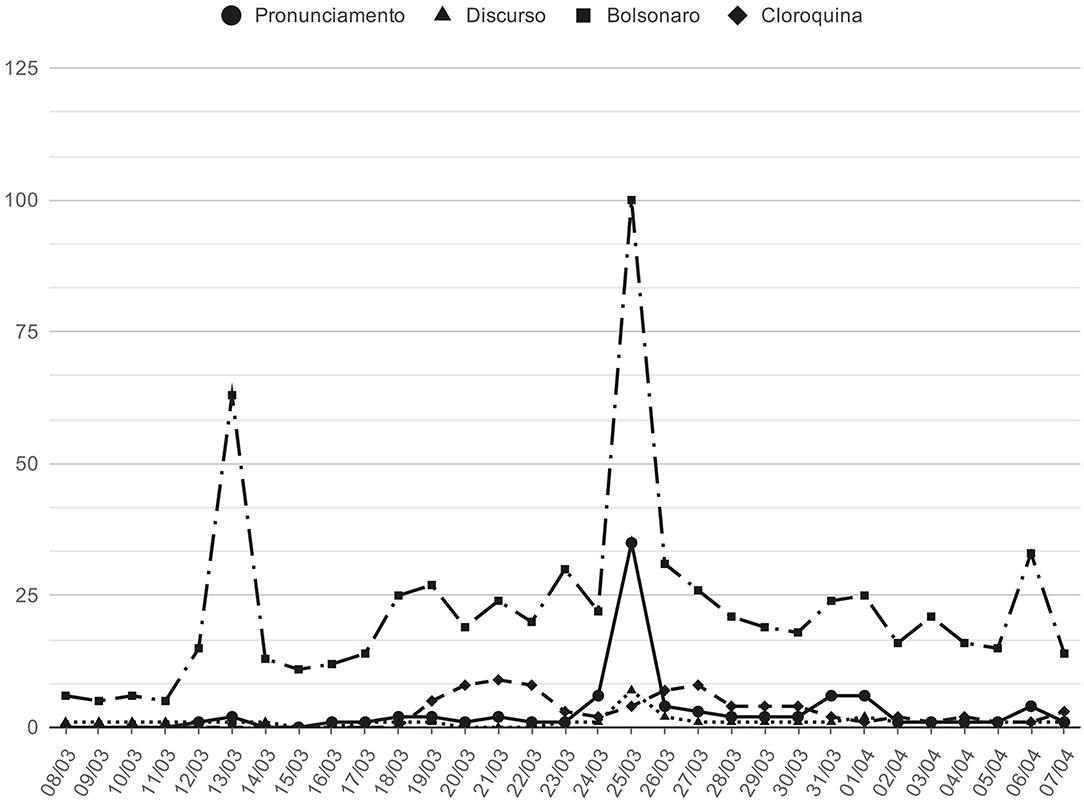

Jair Bolsonaro's Second Speech During the Pandemic: A Sequence of Wrong Interpretations of Science

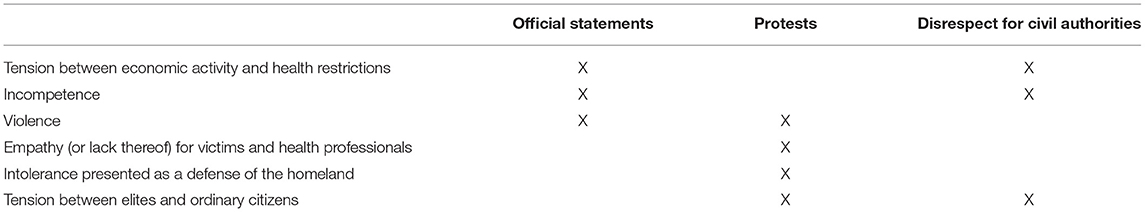

After the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the new coronavirus pandemic, on 11 March 2020, political leaders had the opportunity to raise awareness and limit risk, spread and impact. The first substantial media linkage of Brazilian President Bolsonaro with the pandemic occurred the next day (Figure 2), when he acknowledged the WHO as acting “in a responsible manner” (the Google Trends data in Figure 2 and in subsequent figures documents that the general keywords shown in Table 1 coalesce around the particular event). In the same speech, he announced that the government was handling the situation, cited the Public Brazilian Health System (SUS) and its capacity to meet the demands, and encouraged people to avoid crowds—including mass gathering organized to support him scheduled for 15 March 2020. That seemed a reasonable response to a serious situation.

Figure 2. Web Search for “Pronouncement,” “Discourse,” “Bolsonaro,” and “Chloroquine” (in Portuguese) between 3/8/20 and 4/7/20. Google trends impact: https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=2020-03-08%202020-04-07&geo=BR&q=pronunciamento,discurso,Bolsonaro,Cloroquina.

However, 12 days later, on 24 March 2020 Bolsonaro addressed the nation for the second time and changed his tone dramatically7. This time, the social media postings based on his speech (from him and others) framed the pandemic as a media exaggeration and as creating a false dichotomy between choosing the economy or choosing restrictions8. Beyond his declarations on the political measures of his government, he blamed the press for “spreading fear by announcing the large number of victims in Italy, a country with a huge number of ancient people and with a totally different weather.” Bolsonaro also argued against social distancing that experts argued was needed to preserve the economy. “Life must go on and employment must be maintained. Livelihood must be preserved. Yes, we must get back to normality.” As a possible treatment for the new coronavirus disease, Bolsonaro introduced to the public debate in Brazil the drug chloroquine.

Bolsonaro's second speech was strongly criticized in the three main newspapers. O Estado de São Paulo produced at least 10 stories criticizing misinformation in the speech and highlighting political dimensions: the panelaços [protests using the noise of pots and pans9] in the largest cities, criticism from influential politicians—both opponents and supporters—of the misinformation, and the insensitivity of his frame of economy vs. lockdown: “Unfortunately some deaths will happen. Patience, it happens, and let's move on.”

Bolsonaro's speech was widely reported on social media. We found 120 tweets or Instagram posts from 43 different influencers. But the 10 most liked tweets and posts on Instagram came largely from Bolsonaro and his supporters. Bolsonaro's own post announcing his speech was liked more than half a million times on Instagram and his son's post on Twitter added another 150,000 likes.

Other influencers did question Bolsonaro's statements, introducing frames of incompetence and even criminality. A comedian and former supporter said that Bolsonaro didn't deserve the chair of the President because he was concerned with his self-image and not with people. A liberal journalist called Bolsonaro's statement “criminal” and his acts a “genocide.” A left-wing politician said that Bolsonaro “debauched” people and called his statements “irresponsible.” Another journalist—considered “neutral” by the Government itself—described a panelaço protest in the wealthy neighborhood of Higienópolis, in São Paulo.

The frame arguing that a lockdown would not protect economic activity appeared quickly: Allan dos Santos, a conservative blogger, wrote: “Exactly: #BrazilcantstopBrazil”10. This hashtag was also shared by Bolsonaro's sons and five other profiles from our sample. Posts in this frame argued that social distancing or lockdown would provoke a decrease in economic activities that would be worse than the virus spread itself. These posts also argued against the framing of Bolsonaro's actions as a “genocide.” Camila Abdo, another conservative blogger identified in the government report as “favorable” to them, said “The president is trying to save the economy. It is unacceptable to be called a genocide when the income of slum dwellers has fallen by 70%. This is fair? Genocide advocates that people die of hunger.” None of the posts from supporters of Bolsonaro contained scientific evidence.

On the other hand, posts criticizing Bolsonaro's speech often used science-based arguments. Debora Diniz, a well-known anthropologist and law professor at the University of Brasilia, said: “If I were Bolsonaro's health minister, today I would make a statement, in which I would read the president's speech, correcting it with each line. It would show the health impact of errors”11.

Another influencer, Átila Iamarino, a biologist who defines himself on his Twitter account12 as a “science communicator and world explainer by choice,” responded to a question about what to recommend with a frame of competence: “Constant pronouncement from everyone at the federal level recommending that people distance themselves and wear a mask. Recommending that they avoid contracting the virus, instead of thinking that it can be treated early. The mantra has a reason.”

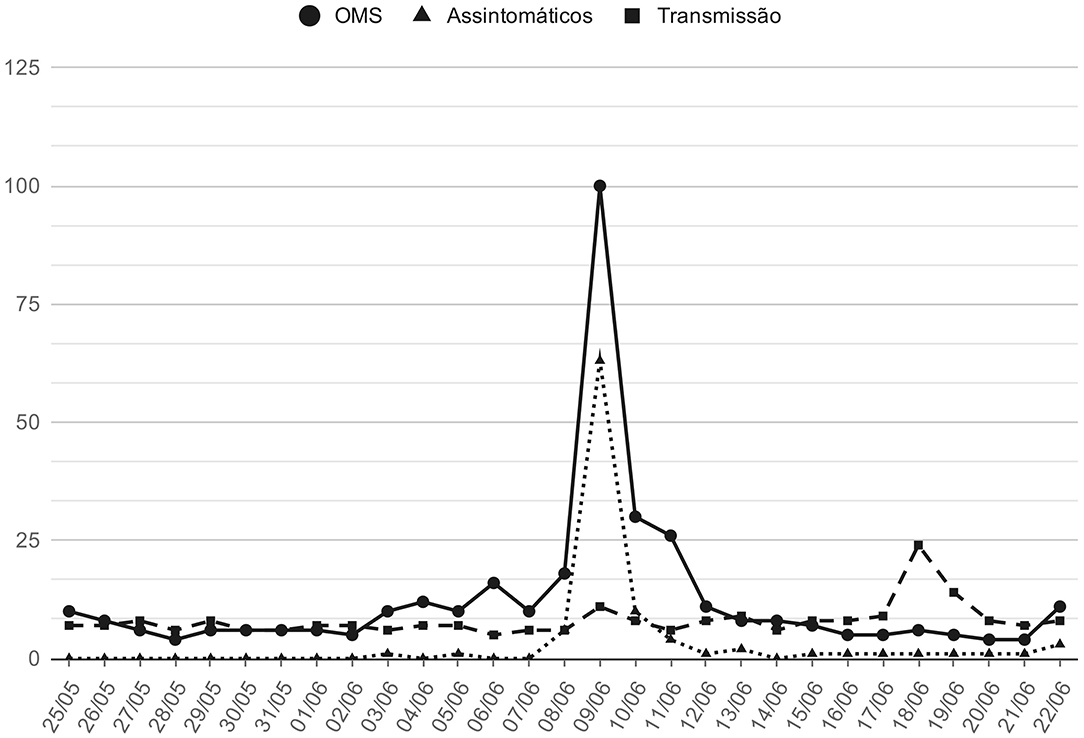

The WHO Statement on Asymptomatic Transmission

Two months later, on 8 June 2020, WHO official Maria Van Kerkhove triggered confusion13 and questions among outside experts and health officials when she said that: “From the data we have it still seems to be rare that an asymptomatic actually transmits onward to a secondary individual.” The next day, she made a “clarification” that “some estimates” had found between 6 and 40% of the population of transmission may be due to asymptomatic transmission. This confusion led to Bolsonaro and his supporters circulating misinformation (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Web Search for “World Health Organization,” “asymptomatics,” and “transmission” between 5/25/20 and 6/22/20. https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=2020-05-15%202020-06-30&geo=BR&q=OMS,Assintom%C3%A1ticos,transmiss%C3%A3o.

For this event, we found 82 tweets or Instagram posts from 35 different influencers. The top 10 most liked posts and tweets almost all supported Bolsonaro's narrative that simultaneously accepted a misinterpreted version of WHO's information while questioning the competence of WHO. Bolsonaro's own tweet on the subject had almost 85,000 likes. Bolsonaro claimed to be right about the use of hydroxychloroquine as a treatment for COVID-19 and stated that the WHO “concludes that asymptomatic patients (the vast majority) have no potential to infect others.” He once more framed the debate as being about a choice between the economy and restrictions. He was supported by eight out of the next nine top posts in our sample from Instagram and Twitter, often with a frame questioning the competence of WHO. Carla Zambelli, a conservative congresswoman, posted a meme in which Bolsonaro appears as the person who was trying to keep people from being deceived14. “He warned!” she wrote. Another conservative congresswoman, Bia Kicis, showed a 10-minute clock in which each minute contradicts the previous one regarding: the severity of coronavirus, the use of masks, the use of hydroxychloroquine, lockdowns, and the transmission by asymptomatics. The only voice that tried to interpret Van Kerkhove's words came from Átila Iamarino. He said the studies were not confirmed and the statement was “missing a lot, like the difference between asymptomatic and pre-symptomatic.” Iamarino posted a long thread on Twitter trying to explain his points, but it never had the same number of likes and sharings and nor the power to make people assimilate its content as the meme oversimplifications.

Iamarino's long Twitter thread demonstrated the difficulty of addressing oversimplifications on social media. But the three main traditional newspapers in Brazil did try to explain the misunderstanding generated by the WHO. Folha de São Paulo developed the first fact checking agency in Brazil: Lupa (“magnifier glass”). The journalist Jaqueline Sordi wrote a detailed timeline about the studies available at the time and added: “Van Kerkhove explained that her speeches were based on personal interpretations of the latest update to the WHO Guide to Wearing Masks, published on June 5”15. O Globo published a story with a list of researchers and scientists who criticized Van Kerkhove's declarations. O Estado de São Paulo went beyond and reported other situations where WHO staff declarations were taken out of context16.

All three main Brazilian newspapers addressed the frames that Bolsonaros was using: the question of WHO competence, and the false dichotomy between economic activity and pandemic restrictions. Folha de São Paulo, O Estado de São Paulo and O Globo published 19 stories during the 7 days immediately following Van Kerkhove's declarations. They reported that the Brazilian president threatened to remove Brazil from WHO because “it lacks reliability” and “looks like a political party” (the “WHO competence” frame). At the same time, throughout the week after Van Kerkhove's statements, they reported on Bolsonaro's declarations that the head of the emergency program would shorten containment policies in Brazil, such as isolation and lockdown; on this issue, the coverage highlighted the “economy vs. lockdown” frame. The articles quoted Bolsonaro: “Who knows? After that declaration [from WHO about asymptomatics], we may be able to return to the normality that we had earlier this year,” he said. “This information will certainly change the orientation of governors and mayors about isolation and confinement.”

Protests to Raise Awareness About Different Aspects of the Pandemic

A Protest for Better Work Conditions and Promoting Social Isolation

Around the globe, health workers on the front lines of the pandemic took risks and struggled with bad conditions and lack of equipment17. In Brazil, on 1 May 2020, a group of 60 nurses held a silent and peaceful protest to raise awareness of the dire situations at hospitals and to warn people about the importance of social distancing for decreasing the number of hospitalizations and deaths. Peaceful protests are a resource (Lipsky, 1968) and “linked to themes that are inscribed in the culture or invented on the spot or—more commonly—can blend elements of convention with new frames of meaning” (Tarrow, 2011, p. 29). At Praça dos Três Poderes in the capital city of Brasília—a square surrounded by the Brazilian Parliament, the Executive Leader Palace and the Supreme Court—the group, dressed in lab coats and wearing protective masks, stood in rows, holding crosses and respecting the recommended distance of at least 6 feet between each person. The nurses held posters with phrases such as “Nursing in mourning for professionals who are victims of the COVID-19” or “Stay at home.” The act also paid homage to the memory of the 55 nurses, technicians, and assistants who had already lost their lives on the front lines due to coronavirus.

During the peaceful protest, a group of Bolsonaro supporters arrived and yelled angrily at the protesters, calling them “shameless,” “cowards,” and “functional illiterates.” “We smell your person and we know that you don't shower properly,” yelled a woman against one of the women protesters. One of the attackers made a video and posted on social media, saying that the protest was “fake news,” that homeless people had been approached and convinced to wear white coats to pass for doctors. After exceeding 20,000 views, the video was deleted, according to the Regional Nursing Council of the Federal District (Coren-DF). The provocateurs were identified by the Coren-DF and sued. “The episode portrays the sad reality of thousands of nursing professionals, who work to save lives and suffer violence in hospitals in the country, silently, silently, with no chance to defend themselves,” stated Coren-DF.

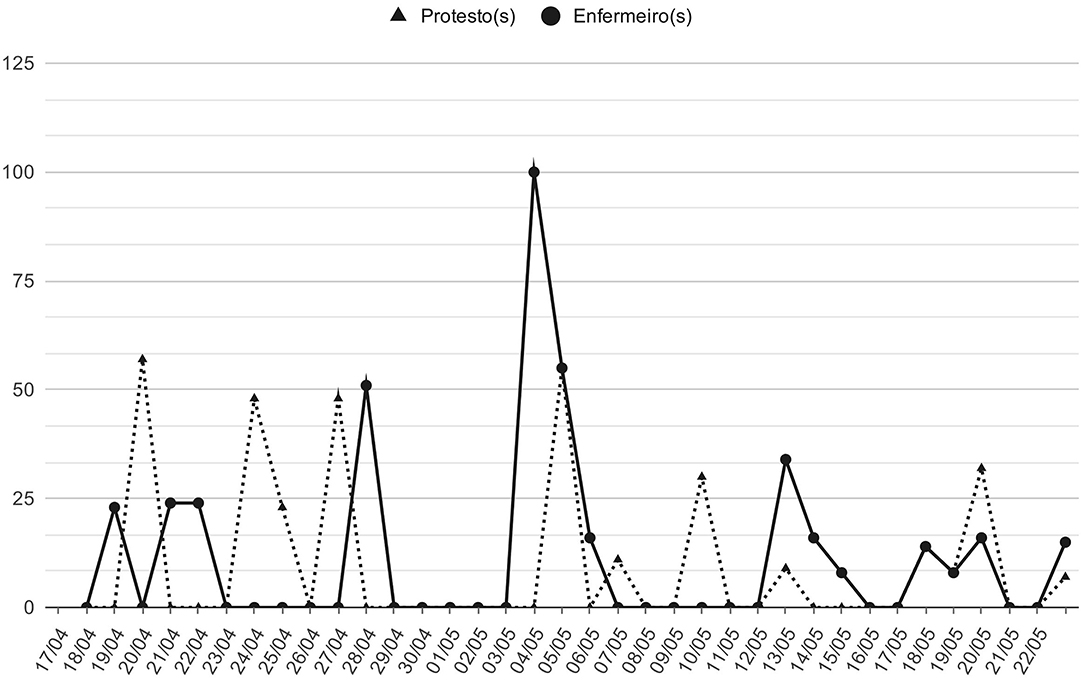

To document Internet-based interest, for this event we found that assessing YouTube searches on Google Trends worked best. We suspect that people wanted to see the images of the protest rather than reading news stories. As Figure 4 shows, searches on Google Trends (YouTube) for “nurses” and “protests” surged 2 days after the protest took place. The search for “nurses” became constant during the pandemic, when compared to previous years.

Figure 4. Google Trends YouTube Search for “protest+protests” and “nurse+nurses” between 4/17/20 and 5/22/20. https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=2020-04-01%202020-05-20&geo=BR&gprop=youtube&q=protesto%20%2B%20protestos,enfermeiros%20%2B%20enfermeiro.

We identified 48 tweets and Instagram posts from 22 individual influencers. Among the top 10 posts, the majority came from individuals identified with left wing politics. Two of the individual influencers (Jean Wyllys and Debora Diniz) had experienced extreme hostility, having to leave the country because of frequent threats from the far right18. All of the top 10 posts on this issue—even one from a far right-wing representative, Joice Hasselmann, who was until 2020 a Bolsonaro supporter—used a frame showing that intolerance disguised as love for homeland allowed political radicalism to overcome humanity or compassion. A related frame highlighted the lack of empathy toward professionals who should be acknowledged as heroes.

The particular issue of peaceful vs. violent protests is also interesting, because of the way different sides framed what constituted “violence.” Protests that turn violent are frequently denounced by Bolsonaro's supporters as an illegitimate form of raising awareness. In both this specific event and the next one, the protests were peaceful until attacked by the president's defenders. The traditional media described the violence as coming from Bolsonaro's supporters: “The silent protest ended after supporters of President Jair Bolsonaro verbally assaulted the professionals,” said O Globo. “Nurses are attacked by Bolsonarists during a silent act for social isolation,” published Estadão. On the other hand, Bolsonaro offered a different frame: “I ordered to investigate if there was a criminal offense (by the nurses), he [the real aggressor] didn't ask for that. So, if there was aggression, it was verbal, which they do to us all the time. There was zero aggression”19.

Protest Against the Brazilian Government Actions Toward the Pandemic

Another peaceful protest became violent 5 weeks later, this time in Rio de Janeiro20. On 11 June 2020 the non-governmental organization Rio de Paz (Rio of Peace) dug graves and stuck 100 crosses at Copacabana Beach, symbolizing the overwhelmed cemeteries and 38,406 deaths from COVID-19 until that day in Brazil21. The NGO was asking for assistance for families in vulnerable situations, for a medical professional to be in charge of the Ministry of Health22, and for a clear plan with explicit goals for combating the disease to be issued by federal, state and municipal governments. But then a 78-year-old man, Héquel da Cunha Osório, knocked down the crosses. Media stories highlighted his framing of the issue as being about public spaces: “I'm going to take this one out. If they have the right to put it… The beach is public. I have the right to take it out. This is an attack on people. This is a terror. It's creating panic. Using the crosses… The cross of Jesus to terrorize the people,” he said. The next day, in a WhatsApp group, da Cunha Osório explicitly tied his act to partisan politics: “Has anyone seen my indignation, dropping crosses that the lefties mounted in Copacabana today? I couldn't resist”23. One of the 10 most liked tweets was from Hildgard Angel, a journalist ranked as a “detractor” by the Brazilian Government. In her post she shared a news story press showing that Héquel's son, Hequel Pampuri Osório, was condemned for the misuse of privileged information, the so-called insider trading, which is a crime in Brazil, adding to a frame about the special privileges given to elites.

An alternative frame of respect for victims was also available: Immediately after da Cunha Osório knocked down the crosses, Marcio Antonio, the father of a coronavirus victim, replaced them. Antonio had lost his 25-year-old son on 18 April 2020 and was surprised—according to him in a positive way—to see the demonstration while walking on the boardwalk.

“I was not protesting at all, so it was just a father's emotion. I was so happy, because I said: hey, a tribute, a tribute for the victims. I felt that nostalgia a little in my heart. When someone arrives and kicks a representation of a person, a victim… This is not freedom of expression. This is just anger, hate, I don't even know the name for it.”

Although this second protest did not lead to a noticeable spike on Google Trends (Figure 5), social media posts explicitly linked the event with the protest that took place in Brasilia 45 days earlier. Overall, 26 tweets or Instagram posts were created from 13 different influencers. Tweets and posts on Instagram compared the events—both were initially peaceful, both were attacked by the president's defenders, and both were trying to raise awareness of the importance of taking health measures. Nine out of 10 Instagram posts or tweets highlighted the empathy frame, pointing out that the statements by Bolsonaro's supporters showed “contempt” or “disrespect” for life and suffering. “The same contempt of Jair Bolsonaro for the dead and the pain of their families. It's too inhuman. Followers of the president attacked a demonstration by [NGO] Rio de Paz on Copacabana beach and took out the crucifixes placed in honor of the Brazilians who lost their lives,” said Marcelo Freixo. Debora Diniz called attention to the phrase used by the father in Copacabana: “Respect people's pain!” She said:

Figure 5. Web Search for “protest,” “Copacabana,” and “Rio de Vida” between 5/28/20 and 6/25/20. https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=2020-05-11%202020-07-11&geo=BR&gprop=youtube&q=protesto,Copacabana,Rio%20de%20Vida.

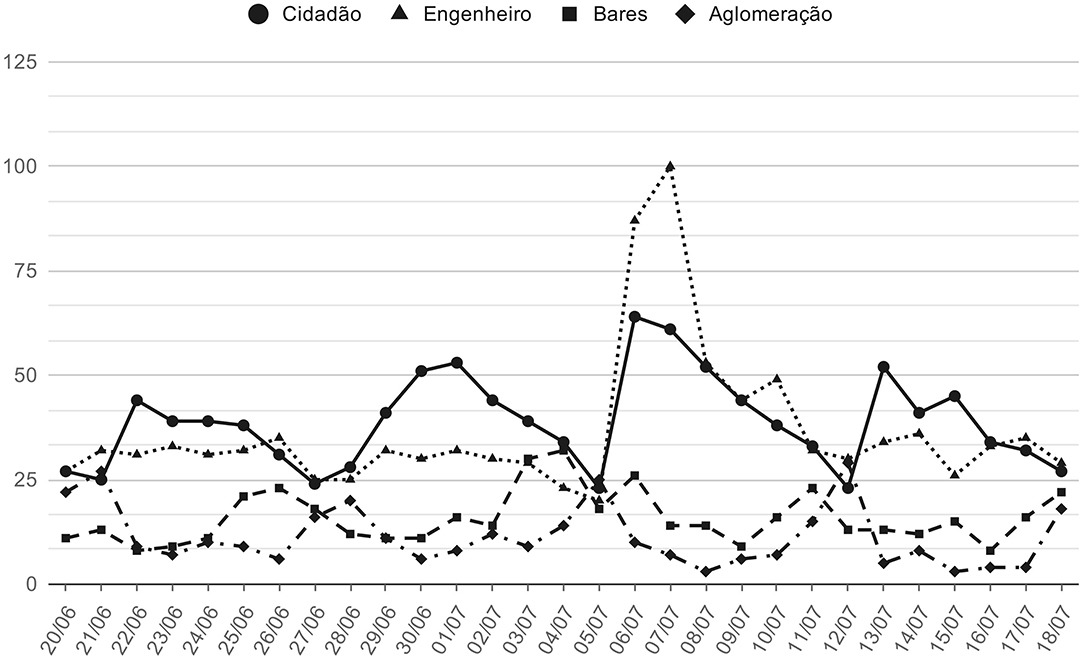

Figure 6. Web Search for “citizen,” “engineers,” “bars” and “overcrowding” between 6/20/20 and 7/18/20. https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=2020-07-01%202020-08-10&geo=BR&q=cidad%C3%A3o,engenheiro,bares,aglomera%C3%A7%C3%A3o.

“Respect the pain of mourning for the 41,058 people who died of covid in the country. • The @riodepaz act was peaceful. Crosses in pits on Copacabana beach. The gesture called for silence. To symbolize a country that burns with longing for lost love, there was a flag on the crosses. • The flag became a bolsonarista property. A free pass for the hatred of people who operate by the spectacle of shouting, force and intimidation. A Bolsonarist avenger stood to take down the crosses, as if he were operating for the squad that hides the numbers of the dead. • The father raised each cross with the anger of those who suffer. With each cross of the cross in the sand, a cry. The cry of insomniacs for the mourning of a tragedy. • Leave the crosses. Let the father scream. He mourns the longing for his 25-year-old son driven by the pandemic”24.

Joice Hasselmann—who right after being elected congresswoman in 2018 with the largest margin of votes in history said “I want to be Bolsonaro in skirts”25—had two posts on Instagram among the top 10 about this event. The hashtags framing her posts included #grief #respect #solidarity #pain #losses #family #sensitivity #solidarity and #empathy. The only tweet to ridicule the protest was made by former rock band leader and conservative Roger Moreira. He brought into the debate a recurrent frame used by Bolsonaro's supporters: if someone is not at their side, this person is an enemy of the homeland. In this case, the content of the post labeled the opponent as a communist, but the perspective was the same.

In traditional media, O Globo quoted Antonio Carlos Costa, the president of Rio de Paz, the NGO that organized the protest installation. His comments addressed the violence frame “We were hearing many expressions of hate on the boardwalk, people teasing us. But even when a man decided to knock over the crosses, we didn't react”26. Folha de São Paulo's use of the violence frame also contrasted the protestors with the attackers: “According to Lucas Louback, project coordinator and activist at Rio de Paz, none of the organization's volunteers tried to stop the man who knocked over the crosses”27. “Our act was intended to signal a representation of the chaos that has become the health care system and we represent that through the ditches. Some interpreted it as an act of a political character and started to attack us.”

Attacks on Public Health and Civic Officials

Officials From the Brazilian Sanitary Agency Attacked After Dispersing Crowds in Bars in Rio

On 4 July 2020, inspectors for the Brazilian Sanitary agency tried to disperse crowds gathering in bars in the wealthy districts of Leblon and Barra da Tijuca in Rio—it was the first opening after 3 months of lockdowns28. One couple who weren't wearing masks, Leonardo de Barros and Nivea Valle, tried to intimidate the agents. The following dialogue took place:

Leonardo: You're not going to talk to your boss, are you?

Nivea: We pay you, son. Your salary comes out of my pocket.

Leonardo: Where's your tape measure? I want to know how you measured without a tape measure.

Agent Flávio Graça: Okay, Citizen.

Nivea: Not a citizen. Civil engineer, trained. Better than you.

The confrontation was captured by a Globo TV program called “Fantástico” and broadcast that night. The health agent, Flavio Graça, is a professional in the Secretariat for Sanitary Surveillance and Zoonosis Control (SUBVISA), a veterinarian with multiple degrees and a researcher in the area of animal health. Due to a national outcry about the lack of respect for an official, Valle was fired the next day from a private company. Her dismissal was celebrated on social media as the term #unemployed went to trending topics on Twitter. de Barros was fired 3 days later and the press found out that he, while employed, had asked for and received at least once emergency aid—R$ 600 (around 115 USD monthly)—intended for people who lost jobs because of the pandemic. That request, too, led to an outcry29.

The day before this event, another inspector, Jane Loureiro, had also been cursed and threatened with being fired30. According to Loureiro, commercial establishments in the area where she worked (a wealthy region in Rio) are more hostile: “They have always been more arrogant in the way they treat us. We have always suffered.” Again, her quotes that appeared in the media presented a frame of conflict between the economy and restrictions.

People came over saying that I was a bad person, that I was taking jobs from waiters, food from waiters' children, and that what I was doing was mean. One came up and said that his father was an attorney, that I was going to lose my job. It was very embarrassing and scary the level of aggressiveness of people.

This event generated 29 tweets or Instagram posts from 19 different influencers. Most of the posts addressed the conflict of a self-perceived elite claiming authority over public agents executing their duties. Interestingly, though, the post with the most “likes” was a fake video from Bolsonaro's son, Eduardo, comparing the crowded bars in the elite neighborhoods where the confrontations took place with a “baile funk” (a funk party) in the poorer Mangueira area of Rio31. This single fake item had more “likes” than the next nine posts combined. But it, too, led to comments about the conflict between elites and public agents. Felipe Neto, a digital influencer with more than 13 million followers on Instagram and 12 million on Twitter, acknowledged in the second most-liked tweet an anger toward the bourgeoisie. “They defeated me. I can no longer not wish to harm others after today's images [of the disrespect] in Leblon. I failed as a human being.” Gregorio Duvivier, a humorist, described the situation as “the personification of bolsonarism in 13 s,” as he shared a video highlighting the snobbish phrases addressed to the health inspector.

The critical posts explicitly framed the events as being expressions of particularly Brazilian culture. Utilizing elements from discourse analysis, semiotics and Brazilian history, professor Debora Diniz posted on Instagram an analysis of the scenes, their connections to specific Brazilian behaviors, and how the impact on spread of the virus:

The Bolsonaro male supporter takes “citizen” as an offense. He has as his spokesman a person next to him who says “not just a citizen, a civil engineer.” Who were they talking to? To a health inspector who asked the couple to wear a mask on the streets. • The moment is like a vision for those who see human stupidity through a keyhole. It can be analyzed from politics to chauvinism, from female subordination to the mandonism patriarchy of Brazilian culture. To me, it is interesting to pause at the absurdity of those who are offended when the “citizen” speaks out to them. • To be a citizen is to be someone with rights. The body that screamed in response claimed that “a civil engineer [is] better than you.” It was not a black body or one from the peripheries. If it were, the way to claim power would be different: perhaps it would be just saying “hey, you.” That would be if there was just speech and not a physical blow. • It was a white body white-washed by its own values, magnified by the power of the country's president who judicially disputes the obligation to wear masks. The anonymous and subordinate type reproduces, as in a herd, his master's mantra: alienation32.

In this case, we see again the frames identified in earlier cases: individualism opposed to the collective good (individual liberty against local/state guidelines obedience); the expectations of the elite for superiority, in the particular Brazilian form called mandonism. Elio Gaspari, a well-known journalist, captured this point: “Cameras have become an effective remedy to combat those who fear democracy, those who are ready to pull rank on ‘the other’, on people who they believe to be inferior. To ‘do you know who you are talking to?’, it is progress to respond with ‘do you know you're being filmed?’”33.

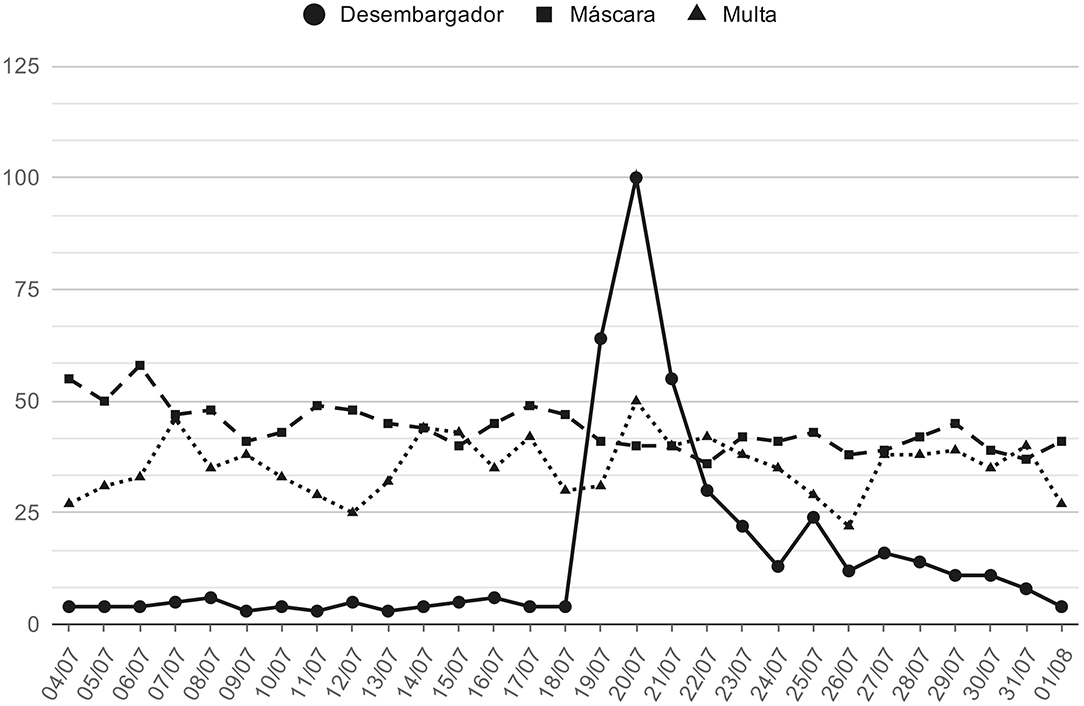

The Appellate Judge Who Humiliated a Municipal Officer in Santos After Refusing to Wear a Face Covering

The final example of disrespect for civil authorities also highlights the frame of a particularly Brazilian response to tensions between elites and civil authorities34,35. On 18 July 2020, appellate judge Eduardo Siqueira was caught on video excoriating a municipal civil guard in Santos, on the coast of São Paulo, after being fined for not wearing a mask while walking on the beach. The mask was mandatory in the city and violators subject to a R$ 100 [around 18 USD] fine. The viral video shows the judge calling the municipal officer “illiterate” and trying to intimidate him by calling the Municipal Secretary of Public Security, Sérgio Del Bel. “Del Bel, I'm here with an illiterate, a Military Police Officer of yours here, a boy. I am walking without a mask. I'm just here on the beach. He's here doing a ticket [against me],” said the judge on the phone. In the conversation, the judge insisted that the municipal decree does not have the force of law to compel residents to wear a mask. “I explained it again, but they [civilian guards] can't understand it,” he said. When the call ended, Siqueira took the ticket, tore the paper, threw it on the ground and walked away.

The background helps highlight the elite vs. citizen frame. The officer, Cícero Hilário Roza Neto, 36, has degrees in public security and educational law. The diplomas, he said later, “only helped me do my job better.” According to Roza Neto, it was thanks to his upbringing and his education that he stood firm in the face of the worst insult he had ever received. “I was called illiterate. And I heard that from a very educated person.… He wanted to intimidate me in every way.” On August 25th, the National Justice Council decided to remove the judge and subject him to disciplinary proceedings36. This case is very similar to the previous one: disrespect for a civil servant, the attempt to intimidate, drawing on the idea of mandonism.

Again the case drew lots of attention, with a clear peak in searches for “Appellate Judge” (Desembargador, in Portuguse). We analyzed 58 tweets from 26 different influencers. Only one influencer, the conservative representative Kim Kataguiri, defended the judge: “For me the wrong thing is the guard who, without having anything to do, instead of hunting a thief goes after a citizen (who was walking alone).” In contrast, Flávio Martins, professor of Constitutional Law, denounced the judge for receiving a wage (more than that of a Supreme Court judge) incompatible with his duty.

This case also showed the interaction of multiple frames and media: Átila Iamarino, the science communicator, had one of the most liked tweets when he promoted his own article in Folha de São Paulo. Titled “100 thousand deaths, and we are opening schools,” his article argued that “in order to open a school, we have to take measures and control the situation outside them”37. He particularly criticized the attacks on public health and civic officials: “Deaths became less of a concern. Those who pay the bill for our strategy, or the lack of a strategy to combat the pandemic, are not the ones who decide. They are mere citizens who die. They are not judges, residents of Alphaville [a franchise of wealthy neighborhoods in large cities in Brazil] or engineers.” Iamarino also drew on the frame of incompetence, condemning the lack of official guidelines and measures. “We don't have official pronouncements, we don't have a Minister of Health, we don't have contact tracking, we don't have a federal strategy, we don't have, we don't have and we don't have.”

Similarly, Monica Bergamo, another digital influencer with a presence in traditional media, drew on the frame criticizing the elites and mandonism. Sharing a post from another journalist, Fabio Pannunzio, Bergamo wrote: “Another idiot who thinks he is Napoleon Bonapart. A Judge who does not know that the law is for everyone. Imagine what this troglodyte does in case files.” Highlighting Judge Siqueira's elite status, traditional journalists learned that he had been cited for the same issue in the past38, that his salary was above the limit, and that the current judge of the São Paulo Court of Justice had sued him for injury and defamation in 1990.

Data Summary

Overall, we identified six recurring emphasis frames in the material we analyzed. Those frames are summarized in Table 2. Of the six, half appeared in two different categories of events.

As noted above, the data presented in Figures 2–7 confirm that the general topics/keywords associated with the specific events were concentrated on those events.

Figure 7. Web Search for “Judge,” “Mask,” and “Fee” between 7/4/20 and 8/1/20. https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?date=2020-06-10%202020-07-31&geo=BR&q=Desembargador,M%C3%A1scara.

Discussion

Our goal in this study was to learn: (1) How traditional and social media in Brazil addressed the health measures associated with COVID-19? and (2) What kinds of different emphasis frames appeared in main media outlets, especially from key or influential actors during the pandemic? By examining some of the most prominent events during the first 6 months of the official pandemic in Brazil, we have documented the recurring tension between the President of Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro (and his supporters), and those who opposed him both politically and on health measures. In the process, we have identified a series of emphasis frames that recurred in both traditional media and social media:

• Tension between economic activity and health restrictions

• Incompetence

° For some, this was the incompetence of those who did not believe in the danger of the pandemic

° For others, this was the incompetence of WHO

• Violence

• Empathy (or lack thereof) for victims and health professionals

• Intolerance presented as a defense of the homeland

• Tension between elites and ordinary citizens.

An important aspect of this study was that we expected some of the emphasis frames to be particular to the Brazilian context. Although some studies of science communication have explored contexts outside of North America and Western Europe, we believe that many more such studies are needed, to learn whether science communication concepts need to be expanded or modified as we apply them in new contexts.

As we don't yet have many studies of COVID-19 science communication (save those in this special section, which we haven't seen as we write this article), we leave to future analysis a more direct comparison of frames. But several of the emphasis frames we found stand out.

First, we know from our own reading of media worldwide that three of the emphasis frames have appeared elsewhere: the tension between economic activity and health restrictions, incompetence, and empathy. Future studies might want to explicitly compare how these emphasis frames appeared in different places.

Second, we know from some preliminary studies in the United States and China that the issue of nationalism and ethnic identity was present in many discussions of COVID-19 (Lu, 2020; Xi and Jia, 2020; Zhou, 2020). Thus, the emphasis frame we found of “intolerance presented as a defense of the homeland” is one we expect could be found in other contexts. This frame points to the role of national identity in science communication, an area that has not been well-studied.

Finally, two of the emphasis frames do speak to Brazilian issues. The extremes of inequality and poverty in Brazil, combined with a very high homicide rate, often lead to a perception of the country as violent and crime-ridden. Thus, the frame of violence, while perhaps not unique to Brazil, may have particular resonance there. Most clearly, we found that many articles and posts drew on the particularly Brazilian concept of “mandonism” in an emphasis frame highlighting the tension between elites and civilians. While neither of these frames is specifically Brazilian, their resonance and language again suggest that individual national contexts can play a role in science communication. Future studies should explore these contexts more carefully.

Overall, our study confirmed that although many emphasis frames likely appeared both in Brazil and elsewhere, some of those frames had specific cultural resonance in Brazil. This confirms our initial suggestion that studying responses to COVID in national contexts would show connections between the cultures of those nations and the local media responses. Obviously, our study only covers a fraction of a complex phenomenon. Available data, for example, did not allow us to connect traditional and social media coverage with public opinion data. Nor were we able to study the fake content circulated both on social media and through messaging systems such as WhatsApp39. Our study was also limited because we do not know the demographic distribution of media and social media audiences, including differences of region or wealth.

Nonetheless, our study helps illustrate some of the forces that let Brazilian authorities ignore established health measures, protocols, guidelines and science in responding to the pandemic. The inequality, racism, and authoritarianism that are fundamental to Brazilian culture are also directly opposed to what science communication aims to do: help humanity understand itself and its environment and find the best way to improve well-being.

By examining both traditional and social media, we can see how, since Bolsonaro's first speech, he, his sons, and their supporters used their strong presence on social media to undermine the key institution needed during the pandemic: official health organizations. Throughout the pandemic, starting in March and continuing past the time of our study, up through recent events (December 2020) when many countries have started vaccinations, Bolsonaro encouraged people to change their primary doctors if they refused to prescribe hydroxychloroquine, defended in court his right to not wear a mask in public, and provided support for patients who experienced side effects from vaccinations. In October, Folha de São Paulo reported a study from Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro that compared information about the expansion of the disease with the result of the first round vote in the 2018 presidential elections in 5,570 municipalities40. The conclusion: there is a correlation between the preference for President Jair Bolsonaro and the expansion of COVID-19. According to the survey, for every 10 percentage points more votes for Bolsonaro, there is an increase of 11% in the number of cases and 12% in the number of deaths.

The importance of understanding emphasis frames and their relationship with real-world outcomes is clear. Bolsonaro's strategy of questioning the severity of COVID-19 is working well for himself, but is a disaster for Brazil. A survey released on 13 December 2020 showed that Bolsonaro's popularity is at its highest level since the beginning of his term in January 201941. Around 37% of Brazilians consider Bolsonaro's first term as “optimal” or “good.” His best approval rate is among employers, at 56%. At the opposite end, students disprove of Bolsonaro the most: 49%.

On 12 December 2020, data from DataFolha—the survey institute of the newspaper Folha de São Paulo—showed that 22% of respondents said they did not want a vaccine against COVID-19, while 73% said they will participate. The change is dramatic from a national survey in August 2020, which showed that only 9% did not intend to be vaccinated, against 89% who said they did. In all, 33% of Brazilians who say they always trust President Jair Bolsonaro said they will not get vaccinated, while that number drops to 16% among those who say they never trust the President42.

An important aspect of our findings is that the protests and the examples of disrespect were perpetrated by (and framed as actions by) those who saw themselves as an elite, acting against those they considered as inferior people or groups. Both traditional media and social media directly tied these actions to Brazilian culture derived from the historical inequalities present since colonization and slavery. This elite/mandonism frame is linked to the emphasis frame that equated protests or law enforcement against Bolsonaro's perspective as an attack on Bolsonaro himself, and therefore as an attack on the homeland (this is despite the fact that the person or group demanding respect was often the group disrespecting and breaking the law, such as obstructing a legal and peaceful protest).

Our results also point to the importance of social media as a very powerful and influential tool for disputing political narratives. It is particularly noticeable, from a science communication perspective, that many of the highly “liked” influencers are professors or politicians with a scientific background—such as Debora Diniz (Social Service and Law), Jean Wyllys (Communication), and Marcelo Freixo (History).

Further research into the relations between science, disinformation and social media are necessary to understand the relationships among science communication, citizenship, democracy, and social justice. The pandemic—which is far from being over, especially in poor countries with restricted access to vaccines—showed the costs of populism and deceit. We must learn how to use education and science-based information for all to avoid such suffering in the future.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2021.646445/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^The casa-grande (“big house”) refers to the slave owner's residence on a sugarcane plantation, where whole towns were owned and managed by one man. The senzala (“slave quarters”) refers to the dwellings of the black working class, where they originally worked as slaves, and later as servants (Wikipedia Contributors 2020).

2. ^Agência de Notícias (2019).

3. ^United Nations Development Program (2020).

4. ^Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center (2020).

5. ^UOL (2020a).

7. ^Planalto (2020).

8. ^Six days after Bolsonaro's speech, Cássia Almeida from O Globo published a news story “Estudo Mostra Que Isolamento Social Leva à Recuperação Econômica Mais Rápido.” O Globo. March 30, 2020. https://oglobo.globo.com/economia/estudo-mostra-que-isolamento-social-leva-recuperacao-economica-mais-rapido-24338226 based on Correia et al. (2020).

9. ^Similar to cacerole is a form of popular protest which consists of a group of people making noise by banging pots, pans, and other utensils in order to call for attention. In Brazil it's made not in the streets but from inside apartments and houses.

10. ^Twitter (2020a).

11. ^Twitter (2020b).

12. ^Twitter (2020c).

13. ^World Health Organization (WHO) (2020a).

14. ^The post by representative Carla Zambelli shows two headlines:

(1) Bolsonaro: people will discover that they were deceived about COVID-19. President again affirmed that there is an exaggeration in the measures to fight coronavirus

(2) Transmission of COVID-19 by patients without symptoms appears to be rare, says WHO. The head of the World Health Organization (WHO) emergency program, Maria van Kerkhove said that transmission of COVID-19 by patients without symptoms appears to be “rare”

She ends her post by writing:

HE WARNED!

15. ^Sordi (2020).

16. ^For example, such as occurred to Michael Ryan, the epidemiologist specialising in infectious disease and public health Director of the WHO Health Emergencies Programme. His phrase “economies have to open up, people have to work, trade has to resume” said on July 27th “does not represent a change in WHO's discourse nor an immediate guidance for the suspension of quarantine measures as misleading posts on social media make believe” (Estadão, 2020a).

17. ^Estadão (2020b).

18. ^Jean Wyllys is a journalist, a lecturer, and Brazil's second openly gay member of parliament and the first congressman who was a gay-rights activist. Debora Diniz is a law professor at Universidade de Brasília.

19. ^Estadão (2020c).

20. ^G1 (2020c).

21. ^World Health Organization (WHO) (2020b).

22. ^Luiz Henrique Mandetta, Bolsonaro's first Minister of Health (1 January 2019–16 April 2020) was succeeded by Nelson Teich (17 April−15 May 2020). Both are medical professionals and were fired due to disagreements on the use of chloroquine as a treatment to COVID-19. General Eduardo Pazuello—an expert in logistics—became acting Minister on 2 June and assumed office on 16 September 2020. In October, O Globo reported that the Ministry of Health had distributed <10% of the hydroxychloroquine received as a donation. Mariz (2020).

23. ^O Globo (2020a).

24. ^“Debora Diniz on Instagram: “Respeitem a Dor Das Pessoas”. Ele Falava Da Prpria Dor. Respeitem a Dor Do Luto Pelas 41.058 Pessoas Que Morreram de Covid No Pas. •….” 2018. Instagram.com. 2020. https://www.instagram.com/p/CBVMR4Tl_Pp/.

25. ^Balloussier (2018).

26. ^O Globo (2020b).

27. ^Folha de S.Paulo (2020b).

28. ^G1 (2020a).

29. ^Globo (2020).

30. ^G1 (2020b).

31. ^UOL (2020b).

32. ^“Debora Diniz on Instagram:” O Macho Bolsonarista Toma “Cidado” Como Ofensa. Tem Como Porta-Voz, Um Corpo Que Fala Ao Seu Lado. 2020. Instagram.com. https://www.instagram.com/p/CCSHYUMFZ6A/.

33. ^Gaspari (2020).

34. ^G1 (2020d).

35. ^Maia (2020).

36. ^Pauluze (2020).

37. ^Folha de S.Paulo (2020c).

38. ^In May, another Civic Guard asked the judge Siqueira to wear a mask. Sigueira got angry and affirmed that Santos City Hall would not have legislative competence over the city's beaches. The guard explained that the intention was to make the population aware. “You are much more enlightened than all of us here,” said the officer, who is soon interrupted by the judge, who agreed (“Of course I'm!”) and began to speak in French, again, trying to diminish the authority of the Municipal Civil Guard. This second video also went viral in Brazil (G1, 2020e).

39. ^2020. Secom.Gov.Br. 2020. http://whatsapp.secom.gov.br/whatsapp/.

40. ^Garcia (2020).

41. ^Gielow (2020).

42. ^Amâncio (2020).

References

Agência de Notícias (2019). Nordeste é Única Região Com Aumento Na Concentração de Renda Em 2019. IBGE. Available online at: https://agenciadenoticias.ibge.gov.br/agencia-noticias/2012-agencia-de-noticias/noticias/27596-nordeste-e-unica-regiao-com-aumento-na-concentracao-de-renda-em-2019

Amâncio, T. (2020, December 12). Cresce Parcela Que Não Quer Se Vacinar Contra COVID-19, e Maioria Descarta Imunizante Da China. Folha de S.Paulo. Available online at: https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/equilibrioesaude/2020/12/cresce-parcela-que-nao-quer-se-vacinar-contra-COVID-19-e-maioria-descarta-imunizante-da-china.shtml

Balloussier, A. V. (2018, October 18). 'Quero Ser o Bolsonaro de Saias', Diz a Deputada Eleita Joice Hasselmann. Folha de S.Paulo. Available online at: https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/poder/2018/10/quero-ser-o-bolsonaro-de-saias-diz-a-deputada-eleita-joice-hasselmann.shtml

Barberá, P., Jost, J., Nagler, J., Tucker, J., and Bonneau, R. (2015). Tweeting from left to right. Psychol. Sci. 26, 1531–1542. doi: 10.1177/0956797615594620

Bartlett, A. (2019). “Controversy studies in science and technology studies,” in SAGE Research Methods Foundations, eds P. Atkinson, S. Delamont, A. Cernat, J. W. Sakshaug, and R. A. Williams. Retrieved from: https://methods.sagepub.com/foundations/controversy-studies-in-science-and-technology-studies (accessed December 11, 2020).

Cacciatore, M. A., Scheufele, D. A., and Iyengar, S. (2016). The end of framing as we know it … and the future of media effects. Mass Commun. Soc. 19:23. doi: 10.1080/15205436.2015.1068811

Cerqueira, D., and Bueno, S., (eds.). (2020). Atlas da Violência. Brasília: Instituto de Pesquisa Econo͡mica Aplicada – Ministério da Economia. doi: 10.38116/riatlasdaviolencia2020

Correia, S., Luck, S., and Verner, E. (2020). Pandemics Depress the Economy, Public Health Interventions Do Not: Evidence from the 1918 Flu. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3561560. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3561560

D'Angelo, P., and Kuypers, J. A. (2010). Doing News Framing Analysis: Empirical and Theoretical Perspectives. Communication Series. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203864463

de Oliveira, D. L., and de Oliveira, G. A. (2020). “Jornalismo Científico e Sociedade em Tempos de COVID-19,”, in Brasil Pós-Pandemia: reflexões e propostas, eds R. Santos and M. Porchmann (Embu das Artes: Alexa Cultural), 261–281.

de Sousa, C. M., Theis, I. M., and Barbosa, J. L. (Org.). (2020). Celso Furtado: a esperana militante. Campina Grande: EDUEPB.

Estadão (2020a, July 31). Boato Distorce Fala Da OMS Sobre Retomada de Atividades Durante Pandemia Estadão Verifica. Available online at: https://politica.estadao.com.br/blogs/estadao-verifica/boato-distorce-fala-da-oms-sobre-retomada-de-atividades-durante-pandemia/

Estadão (2020b, May 2). Bolsonaristas Que Agrediram Enfermeiros Em Brasília São Identificados e Serão Processados – Política. Estadão. Available online at: https://politica.estadao.com.br/noticias/geral,bolsonaristas-que-agrediram-enfermeiros-em-brasilia-sao-identificados-e-serao-processados,70003290410

Estadão (2020c, May 5). Bolsonaro Diz Que Não Houve Agressão Em Manifestação: 'Zero' – Política. Estadão. Available online at: https://politica.estadao.com.br/noticias/geral,bolsonaro-diz-que-nao-houve-agressao-em-manifestacao-zero,70003292849

Folha de S.Paulo (2020a, November 11). A Posição Ideológica de 1,8 Mil Influenciadores No Twitter Em 2020 Baseado Em Seus Seguidores. Folha de S.Paulo. Available online at: http://temas.folha.uol.com.br/gps-ideologico/reta-ideologica-2020/a-posicao-ideologica-de-1-8-mil-influenciadores-no-twitter-em-2020.shtml

Folha de S.Paulo (2020b, June 11). Homem Derruba Cruzes e Ataca Homenagem a Vítimas Da COVID-19 No Rio. Folha de S.Paulo. Available online at: https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/cotidiano/2020/06/homem-derruba-cruzes-e-ataca-homenagem-a-vitimas-da-COVID-19-no-rio.shtml

Folha de S.Paulo (2020c, August 9). 100 Mil Mortes, e Abrimos Escolas. Folha de S.Paulo. Available online at: https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/colunas/atila-iamarino/2020/08/100-mil-mortes-e-abrimos-escolas.shtml

Freire, P. (2014). Pedagogy of the Oppressed: 30th Anniversary Edition. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Academic & Professional.

Freyre, G. (1980). Casa-Grande & Senzala: Formação Da Família Brasileira Sob o Regime Da Economia Patriarcal. Rio de Janeiro: José Olympio.

G1 (2020a, July 6). Fiscais sofrem ataques ao reprimir aglomerações em bares do Rio; veja flagrantes. G1. Available online at: https://g1.globo.com/fantastico/noticia/2020/07/05/fiscais-sofrem-ataques-ao-reprimir-aglomeracoes-em-bares-do-rio-veja-flagrantes.ghtml

G1 (2020b). Um Dia Antes de 'Cidadão, Não. Engenheiro Civil, Formado', Outra Fiscal Da Prefeitura Do Rio Sofreu Ameaça Durante Inspeção. G1. Available online at: https://g1.globo.com/rj/rio-de-janeiro/noticia/2020/07/08/um-dia-antes-de-cidadao-nao-engenheiro-civil-formado-outra-fiscal-da-prefeitura-do-rio-sofreu-ameaca-durante-inspecao.ghtml

G1 (2020c, June 15). Não resisti', diz mensagem que seria de aposentado que derrubou cruzes em ato por vítimas da COVID-19 em Copacabana. Available online at: https://g1.globo.com/rj/rio-de-janeiro/noticia/2020/06/15/nao-resisti-diz-mensagem-que-seria-de-aposentado-que-derrubou-cruzes-em-ato-por-vitimas-da-COVID-19-em-copacabana.ghtml

G1 (2020d, July 19). Desembargador humilha guarda após multa por não usar máscara em SP: 'Analfabeto'. G1. Available online at: https://g1.globo.com/sp/santos-regiao/noticia/2020/07/19/desembargador-humilha-guarda-apos-multa-por-nao-usar-mascara-em-sp-analfabeto.ghtml

G1 (2020e, July 19). Desembargador que humilhou guarda em SP por conta de máscara já havia ameaçado inspetor. G1. Available online at: https://g1.globo.com/sp/santos-regiao/noticia/2020/07/19/desembargador-que-humilhou-guarda-em-sp-por-conta-de-mascara-ja-havia-ameacado-inspetor-video.ghtml

Garcia, D. (2020, October 12). ‘Efeito Bolsonaro’ Sobre Alta Nos Casos de Coronavírus Surpreende Pesquisadores. Folha de S.Paulo. Available online at: https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/mercado/2020/10/efeito-bolsonaro-sobre-alta-nos-casos-de-coronavirus-surpreende-pesquisadores.shtml

Gaspari, E. (2020, July 8). Cidadão, Não. Engenheiro Formado. O Globo. Available online at: https://oglobo.globo.com/opiniao/cidadao-nao-engenheiro-formado-24520587

Gielow, I. (2020, December 13). Avaliação de Bolsonaro Se Mantém No Melhor Nível, Mostra Datafolha. Folha de S.Paulo. Available online at: https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/poder/2020/12/avaliacao-de-bolsonaro-se-mantem-no-melhor-nivel-mostra-datafolha.shtml

Gilbert, J., and Stocklmayer, S. (2013). Communication and Engagement with Science and Technology. New York, NY: Routledge.

Globo, J. O. (2020). Casal Do 'cidado No, Engenheiro Civil' Diz Que Neo Se Arrepende. YouTube. Available online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a3DwQc9XiTo

Hallal, P. C., Hartwig, F. P., Horta, B. L., Silveira, M. F., Struchiner, C. J., Vidaletti, L. P., et al. (2020). SARS-CoV-2 antibody prevalence in Brazil: results from two successive nationwide serological household surveys. Lancet Global Health. 8, 1390–1398. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30387-9

Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center (2020). Mortality Analyses. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. Available online at: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/mortality

Lipsky, M. (1968). Protest as a resource. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 62, 1144–1158. doi: 10.2307/1953909

Lu, H. (2020). “Motivations for and consequences of U.S.-Dwelling Chinese's Use of U.S. and Chinese Media for COVID-19 information,” in World Conference on Science Literacy, Forum on Science Literacy and Public Health (Beijing).

Maia, D. (2020, July 20). ‘Não Sai Da Minha Mente’, Diz Guarda-Civil Sobre Ofensa de Desembargador. Folha de S.Paulo. Available online at: https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/cotidiano/2020/07/nao-sai-da-minha-mente-diz-guarda-civil-sobre-ofensa-de-desembargador.shtml

Mariz, R. (2020, October 9). Saúde Distribuiu Menos de 10% Da Hidroxicloroquina Recebida Como Doação. O Globo. Available online at: https://oglobo.globo.com/sociedade/saude-distribuiu-menos-de-10-da-hidroxicloroquina-recebida-como-doacao-24686406

Ministry of Labor of Brazil (2020). Available online at: https://sit.trabalho.gov.br/radar/ (accessed December 16, 2020).

Muggah, R., and Aguirre Tobón, K. (2018). Citizen Security in Latin America: Facts and Figures. Rio de Janeiro: Igarapé Institute.

O Globo (2020a, June 15). Veja Quem é o Homem Que Invadiu Local de Ato Por Vítimas Da COVID-19 Em Copacabana e Derrubou Cruzes. O Globo. Available online at: https://oglobo.globo.com/rio/veja-quem-o-homem-que-invadiu-local-de-ato-por-vitimas-da-COVID-19-em-copacabana-derrubou-cruzes-1-24480035

O Globo (2020b, June 11). 'Vocês Têm Que Respeitar a Dor Das Pessoas', Lamenta Pai Que Perdeu Filho Com COVID-19 Ao Recolocar Cruzes de Protesto Em Copacabana. O Globo. Available online at: https://oglobo.globo.com/rio/voces-tem-que-respeitar-dor-das-pessoas-lamenta-pai-que-perdeu-filho-com-COVID-19-ao-recolocar-cruzes-de-protesto-em-copacabana-24474620

Pauluze, T. (2020, August 25). CNJ Decide Afastar Desembargador, Que Responderá a Processo Disciplinar Por Ofender Guarda Em SP. Folha de S.Paulo. Available online at: https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/cotidiano/2020/08/cnj-decide-afastar-desembargador-que-respondera-a-processo-disciplinar-por-humilhar-guarda-em-sp.shtml

Planalto (2020). Pronunciamento Do Presidente Da República, Jair Bolsonaro. YouTube. Available online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vl_DYb-XaAE (accessed March 24, 2020).

Reese, S. D. (2001). “Prologue—Framing public life: A bridging model for media research,” in Framing Public Life: Perspectives on Media and Our Understandings of the Social World, eds S. D. Reese, O. H. Gandy Jr., and A. E. Grant (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum), 7–31.

Reporters Without Borders (2020). Available online at: https://brazil.mom-rsf.org/en/ (accessed November 3, 2020).

Scheufele, D. A., and Iyengar, S. (2015). “The state of framing research: a call for new directions,” in Oxford Handbook of Political Communication, eds K. Kenski and K. H. Jamieson (New York, NY: Oxford University Press), 619–632.

Sordi, J. (2020, June 12). Lupa Na Ciência: Entenda a Confusão Sobre Transmissão Da COVID-19 Por Quem Não Tem Sintomas. Agência Lupa. Available online at: https://piaui.folha.uol.com.br/lupa/2020/06/12/lupa-na-ciencia-assintomaticos-transmissao/

Tarrow, S. G. (2011). Power in Movement: Social Movements and Contentious Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Twitter (2020a). Available online at: https://twitter.com/allanldsantos/status/1242613767365636120 (accessed December 17, 2020).

Twitter (2020b). Available online at: https://twitter.com/Debora_D_Diniz/status/1242794010835640320 (accessed December 17, 2020).

Twitter (2020c). Available online at: https://twitter.com/oatila?lang=en (accessed December 17, 2020).

United Nations Development Program (2020). Human Development Report. The Next Frontier Human Development and the Anthropocene. Available online at: http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/hdr2020.pdf (accessed December 15, 2020).

UOL (2020a, December). Veja a Lista de Jornalistas e Influenciadores Em Relatório Do Governo. UOL. Available online at: https://noticias.uol.com.br/colunas/rubens-valente/2020/12/01/lista-monitoramento-redes-sociais-governo-bolsonaro.htm

UOL (2020b, July 12). Eduardo Ironiza Festa Em Favela, Mas Vídeo Foi Feito Antes de Pandemia. UOL. Available online at: https://noticias.uol.com.br/saude/ultimas-noticias/redacao/2020/07/11/eduardo-ironiza-festa-em-favela-mas-video-foi-feito-antes-de-pandemia.htm

Women in Parliaments: World Classification (2019). Available online at: http://archive.ipu.org/wmn-e/classif.htm (accessed October 4, 2020).

World Health Organization (WHO) (2020b). Brazil: WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. Available online at: https://covid19.who.int/region/amro/country/br

World Health Organization (WHO) (2020a, 08 June). Live from WHO headquarters – COVID-19 Daily Press Briefing. YouTube. Available online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dZoIOyiZnt8

Xi, L., and Jia, H. (2020). “I wear a mask for my country: how nationalism and trust shaped Chinese public's preventive measures against COVID-19,” in World Conference on Science Literacy, Forum on Science Literacy and Public Health (Beijing).

Keywords: media representations, political action, Brazil, COVID-19, pandemic, emphasis frames

Citation: Lopes de Oliveira D, Moreno E and Lewenstein BV (2021) Media Representations of Official Declarations and Political Actions in Brazil During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Commun. 6:646445. doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2021.646445

Received: 26 December 2020; Accepted: 09 March 2021;

Published: 09 April 2021.

Edited by:

Anabela Carvalho, University of Minho, PortugalReviewed by:

Junxiang Chen, University of Pittsburgh, United StatesIain Cruickshank, Carnegie Mellon University, United States

Copyright © 2021 Lopes de Oliveira, Moreno and Lewenstein. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bruce V. Lewenstein, Yi5sZXdlbnN0ZWluQGNvcm5lbGwuZWR1

Diogo Lopes de Oliveira

Diogo Lopes de Oliveira Erick Moreno

Erick Moreno Bruce V. Lewenstein

Bruce V. Lewenstein