Abstract

Introduction:

Animation transfers human races into animals, serving as a prime site for speciesism and racism.

Methods:

Testing this observation on recent examples, our quantitative/qualitative study delves into a nine-year (2016-2024) span of Oscar-nominated animated feature and short films. We theorize how to make incisive, quantitative/qualitative, balanced trans-species intersectionality the foundation of critical research on racism and speciesism. We offer the Media Analysis of Racism and Speciesism Test (MARS test), a practical tool accessible to scholars, creators, and general viewers for analyzing character portrayals and interactions, helping identify and challenge normalized racist and speciesist storylines.

Results:

Insufficient number of films yielded transspecies allyship.

Discussion:

The MARS test is for anyone who is interested in ways film and other media offer questionable implications regarding racism and speciesism that call for accountability.

“...[E]ven the most exciting scholarship to emerge … does not address animality as … a humanist construct that is also or especially … race/ist.”

― M. Shadee Malaklou, “Critical Animal Studies has a Race Problem.” (2020).

“Animals show the truth about a country. … If people behave brutally toward Animals, no form of democracy is ever going to help them, in fact nothing will at all.”

― Olga Tokarczuk, Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead (2009).

1 Introduction

1.1 Audiences have changed. Have the Oscars lagged?

Racist and speciesist tropes are deeply interdependent. When Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse won the Oscar in the category of feature animation (91st season, 2019), critics praised the movie for its remarkable plot and technical qualities. But why was the first Black Spider-Man (Miles Morales, voiced by Shameik Moore) introduced together with the character of Spider-Ham, who is ridiculed for being a pig? To what extent did having a Black main character nudge the movie over the edge to win the Oscar? Was its win a window dressing reminiscent of Denzel Washington’s iconic comment on his and Halle Berry’s 2002 wins (Oscars, 2002; Simpson, 2003)?

Spider-Man’s development stage (circa 2014-2017) coincided with vigorous debates on the racism of the Oscar awards after two years of all white nominees. In 2015, when David Oyelowo was snubbed from nomination for playing Martin Luther King in Selma, the hashtag #OscarsSoWhite exploded; the following year, Al Sharpton accused the Academy of having a “fraudulent progressive and liberal image” (“Lifetime Voting, 2016; Reed, 2016). A week later, the Academy committed to doubling the number of diverse members by 2020 (“Lifetime Voting”), hoping to end its public identity crisis. Indeed, recent scholarship exposes the Oscars as an institution mired in racism, from the films it nominates to the industry it celebrates (Hudson, 2022; Sinckler, 2014; Vliet, 2021). Despite declining viewership, the awards still matter. Yet, even with historic wins, like the first Asian American (2023) and first Indigenous (2024) actors, racism remains embedded in Oscars politics.

A similar identity crisis looms for animal actors. Messi, the border collie actor in the winner Anatomy of a Fall, clapped from his own seat at the 96th 2024 Oscar awards. Even though the Academy tweeted that “the Oscar for bestest boi goes to Messi” (Tweet, 2024), there has been public discontent that his and other animal actors’ performances are not eligible for a nomination in any category (Rosenberg, 2023; Thompson, 2012). In 2023, Josh Rosenberg awarded Esquire’s first annual Best Animal Actor award to Jenny the Donkey from Banshees of Inisherin. Even though Rosenberg claims such an award is “the only respectful thing to do” (2023), his comparisons to dog shows and Kennel Club dog parades betray conceiving of dogs as prized possessions (objects of entertainment) rather than subjects of their own lives. So far only PETA has spotlighted nonhuman animals’ wellbeing and standpoint with its first Oscat awards (2018) for best animated film, best picture, best actor, etc., honoring movies and stars promoting “kindness to animals through positive story lines and … use of computer-generated imagery (CGI)” (Toliver, 2018). Despite being accepted as one of the Spider superheroes, Spider-Ham’s character does not embody this kindness to animals. Quite the opposite, it resuscitates a 40-year-old speciesist caricature that itself hearkens back to the 1930’s wall painting of sausages labeled “Dad” in Disney’s animated film, Three Little Pigs.

A Fandango survey found over half of moviegoers want vegan and healthy snacks options (Daniels, 2022). Gen X, Millennial, and Gen Z audiences are increasingly influenced by Vegemovies (e.g., Cowspiracy or Fishspiracy) to change their diets and lifestyles (Aguilar, 2025). More people in developed countries like the U.S. and European nations have companion animals than ever before, while entire new industries cater to companion animals as family members, from law to health insurance to cremation. More moviegoers than ever are interested in animal wellbeing and welfare. Yet, as we show, aside from a few films (Flow; Kitbull) contemporary mainstream animated films do not reflect such evolution (Green and Alon 2024; Vento, 2024; Wolfe, 2022).

What do we make of the complex, ambiguous, and unexamined interdependence between racist and speciesist tropes embedded in the most prestigious global film awards? How do we theorize this interdependence in film and media more broadly? We explore these questions through the lens of Oscar-nominated animation films (one of two main genres featuring plenty of nonhuman animals). Why pay attention to animation in the first place? In analyzing historical wartime animé, Thomas Lamarre (2010) observes that animation transfers human races into animals, serving as a prime site for speciesism and racism. Testing this observation on recent examples, our quantitative/qualitative study delves into a 9-year (2016-2024) span of Oscar-nominated animated feature and short films.

Examining how animated films convey racism and speciesism is crucial because this genre serves as a source of early socialization for children, subtly perpetuating biases through stereotypes and character roles. Our research then can inform educational policies, including media literacy programs teaching critical analysis of media consumed by children. Animated films may seem like harmless children’s entertainment, but being made by and often also for adults, they have a darker side connected to the suasory functions of graphic art that demand scrutiny (Alehpour and Abdollahyan, 2022; Arnold et al., 2020; BBC, 2020; Cole and Stewart, 2014, 2017; Salny and Voychenko, 2021). Twentieth century portrait caricature, war posters, and comics provide chilling examples of nationalistic, racist dehumanization of enemies (Keen, 1986; Gombrich, 1971). In the 2000s, fascist politics, Islamophobia and anti-ecological movements also used cartoons as deadly propaganda tools to spread racist and speciesist ideologies, portraying human enemies as animal species—cockroaches, pigs, monkeys, rats, etc. (see also Smith, 2011; Patterson, 2002). Social media, handheld devices, cartoons, and animated films, just like advertising, promote symbolic violence against disenfranchised humans and nonhuman species alike (Adams, 2010). Given this history, key questions this article poses include: How can we theorize animated films in which racialized human characters are animalized, or animals stand in for marginalized human groups? How can we address theoretical challenges of analyzing the intersection of speciesism and racism in animation? And is there a meaningful connection between racism and speciesism in the first place?

1.2 Racism/speciesism intersections

This section argues that racism (bias and unequal treatment because of someone’s race) and speciesism (bias and unequal treatment because of someone’s species) intersect structurally and symbolically in ways that reinforce the suffering of humans and nonhuman animals. We show that without acknowledging speciesism, we can wrongfully attribute racism to the ways humans relate to other humans alone rather than seeing its roots in broader systems of domination over (human and nonhuman) animal life.

One aspect of this intersection concerns the historical roots of human-animal hierarchies. Conceptual systems imposing order on biology like Aristotle’s Great Chain of Being or scala naturae have long ranked human groups depending on race or ethnicity, placing some closer to nonhuman animals. Biological hierarchies deny intrinsic moral worth to nonhuman animals, making any closeness to them a basis for the dehumanization and discrimination of racialized human groups. These ideas still shape material relations, justifying the exploitation of racialized human groups as well as nonhuman animals, denying the shared biology and common descent of all animal species (Albersmeier, 2021; Rigato and Minelli, 2013). Colonialism, for example, did not just exploit racialized peoples; it also reorganized human-animal relations leading to the increase of racial oppression (Boisseron, 2018; Plec, 2024). This reorganization resulted in the material entanglements of human and nonhuman suffering (see below our discussion of Wolfwalkers).

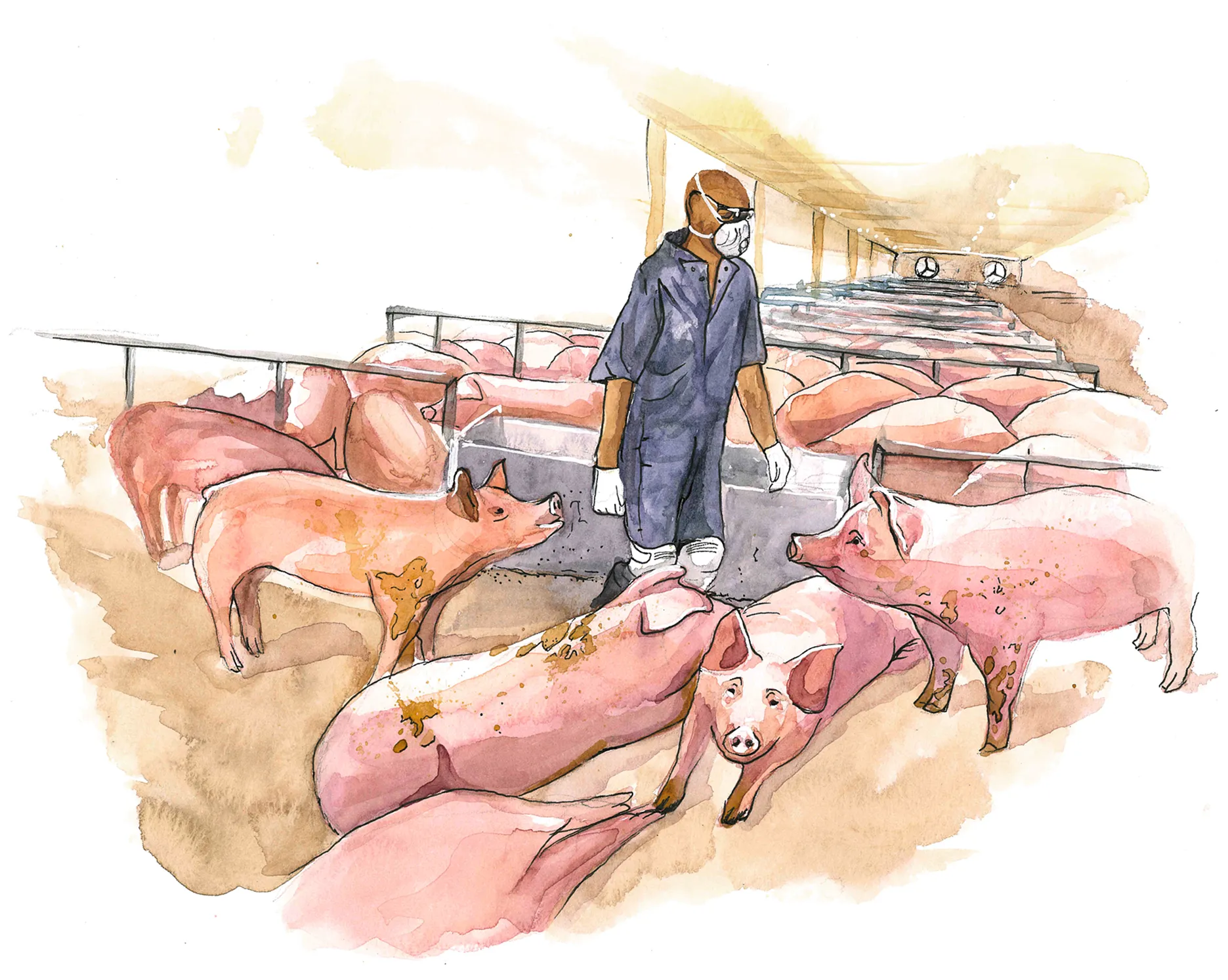

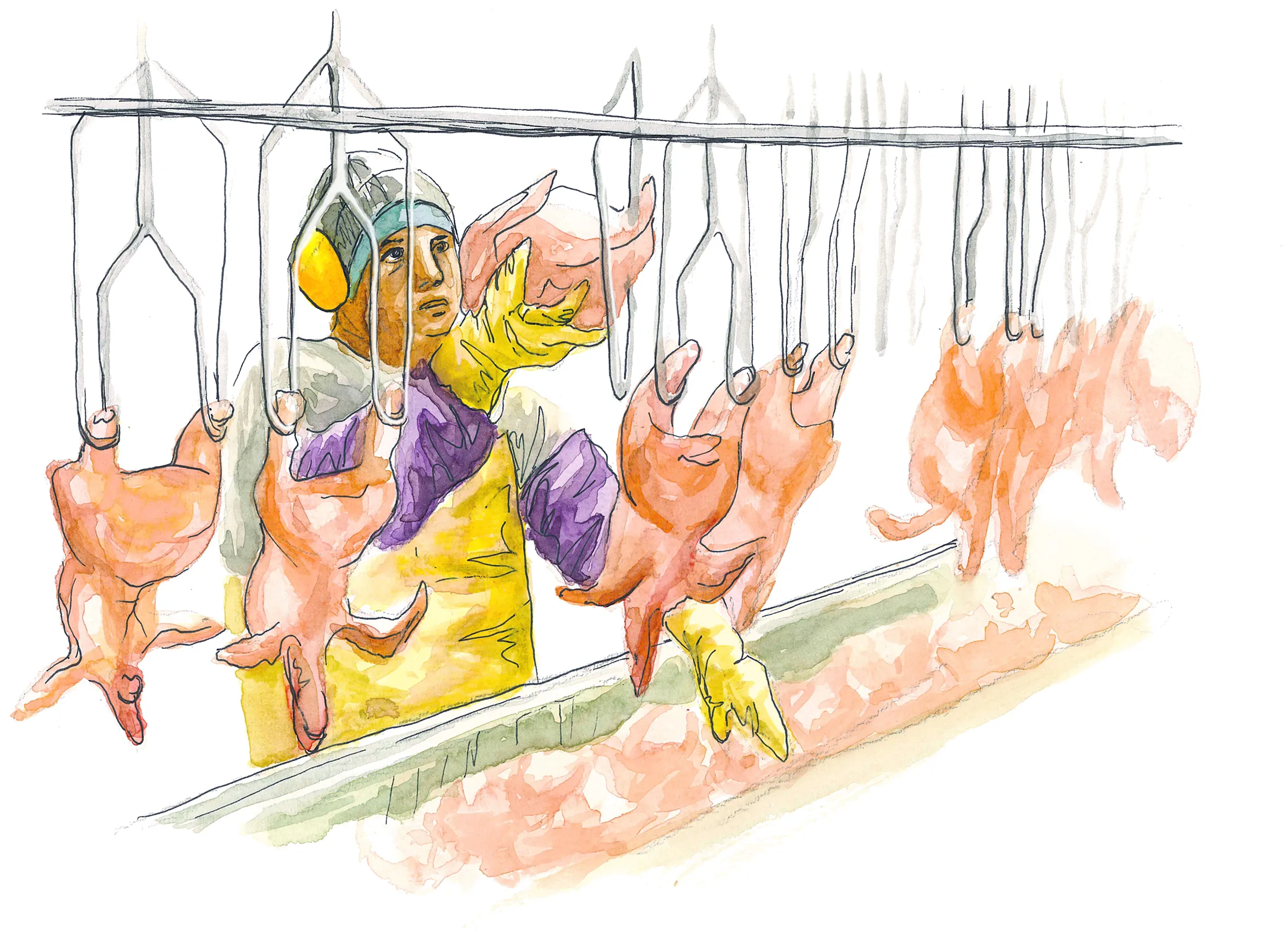

Another aspect of this intersection pertains to animal industries and racialized labor. Capitalism and politics merge the suffering of racialized laborers, like refugees and immigrants, with that of nonhuman animals in animal slaughter-to-meat production, where all species face exposure to illness (COVID-19; bird-/swine-flus, etc.) and violence (Khazaal, 2021; Yang, 2024). Refugees and immigrants do most of the labor in the meat industry. Yet they have little recourse to political protection in dead-end jobs faced with immigration enforcement raids, injury rates three times higher than the average American employee, low wages, no childcare, poor housing, and no employment insurance (Yang, 2024; Human Rights Watch, 2004). The meat industry places both human laborers and nonhuman victims in a Twilight-zone of inclusion–exclusion, law-violence, life-death, where all degrade into economic units (Khazaal, 2021).

A third aspect involves environmental racism, borders, and species displacement. Intensified animal agriculture pumps up greenhouse gases, deteriorates ecosystems, displaces Indigenous people and free-living animals, increasing species extinction (American Public Health Association, 2019; Lowry, 2024; Walton and Jaiven, 2020). These processes affect global racialized communities who “bear a disproportionate burden of [a] nation’s air, water, and waste problems” (Bullard, 1993). Racialized and migrant laborers in agribusiness are often poisoned by toxic pesticides and herbicides and live in areas disproportionately exposed to environmental hazards, such as factory farms’ waste sites and industrial runoff (Cannon et al., 2024; Cannon, 2024). Border walls like the US-Mexico wall prevent refugees from seeking safe haven while blocking the migratory paths of animal species, leaving many to suffer or die from dehydration, starvation, or displacement (Palazzo, 2025; Pearce, 2022; Yeo, 2024; Schlyer, 2017). Surveillance vehicles and patrols designed to detect and deter migrants destroy habitats and injure free-living animals, demonstrating the interdependence of anti-immigrant and speciesist violence (Perret, 2021; Schlyer, 2017).

A fourth aspect deals with the histories of legal exclusion, surveillance, captivity, and incarceration. Racialized humans and nonhuman animals have been excluded from personhood, denied rights, and treated as property to be bought, sold, and exploited (Osman and Redrobe, 2022). Where these forms of exclusion intersect most visibly is in controversial, racialized animal practices—e.g., animal markets, dogfighting, or halal slaughter—which simultaneously harm racialized communities and nonhuman animals (Kim, 2015).

In addition, the exploitation of non-consenting nonhuman animals as tools of oppression against racialized human groups has a long history: from bloodhounds trained to hunt colonized humans (Jalata, 2013), to horses and dogs used to track escaped slaves, to police dogs deployed during Jim Crow, and in political wars on drugs and terror (with Black and Brown suspects referred to as “dog biscuits”) (Swistara, 2022). While performing the aggression that they have been violently trained to carry out, dogs and other nonhumans become victims themselves—placed in the line of fire against their will, treated as dispensable. Captivity and incarceration employ similar mechanisms of oppression against both racialized humans and nonhuman animals, including protection of state actors through qualified immunity. Prisoners are incarcerated—some experimented on—while enslaved humans have been paraded for the entertainment of audiences. Likewise, nonhumans are held in captivity in kill shelters and laboratories, subjected to experimentation, and displayed for entertainment in circuses, talent shows, and zoos.

The last aspect concerns discourses of intersectional violence and dehumanization. Speciesism has become a framework for dehumanizing racialized communities and individuals—in other words, conceptualizing them as less than human and on a “lower” level, together with nonhuman animals (Khazaal, 2021). Dehumanization is often enacted via species-based terms to refer to racialized groups, such as beasts, mad dogs, Jew pigs, snakes, wolves, swine, gorillas, animals, rats, parasites, vermin, apes, and others (Smith, 2011; Patterson, 2002). While animalesque language fuels this discrimination and injustice against racialized communities, it simultaneously reinforces nonhuman-animals’ marginalization and exclusion, denying them moral consideration. The symbolic violence of derogatory animal metaphors merges with material violence to strengthen the connections between speciesism and racism.

Understanding these historical, multidimensional intersections between racism and speciesism matters for animation because they shape how we see and value or devalue human and nonhuman lives. These representations aren’t just symbolic; they help normalize real-world violence, justify injustice, and erase the suffering of marginalized humans and nonhuman animals. Because animated films reflect and shape ideas and practices harmful to justice across species and identities, it is essential to explore them critically.

1.3 Contributions: theoretical and practical tools for race and species intersectionality

With the above considerations in mind, this article addresses in theory and in practical applications the need for a deep, quantitative/qualitative, balanced trans-species intersectionality. The term trans-species refers to issues encompassing human and nonhuman animals, with intersectionality in this context broadened, expanding its original, human-bound prism, enabling recognition of ranges between relative privilege (i.e., greater concern for gorillas than racialized humans in war) to oppression (e.g., little or no consideration for pigs’ suffering in agribusiness, prioritizing humans’ cheap bacon) (Matsuoka and Sorenson, 2018; for more examples, see analysis below and Appendix A).

Our first main contribution is to theorize how to make incisive, quantitative/qualitative, balanced trans-species intersectionality the foundation of critical research on racism and speciesism. To address racism and speciesism is difficult separately, let alone as a combined set of amplified harms. For example, shared oppressions between black women and nonhuman animals raised/killed for their body products has been addressed convincingly (e.g., Sistah Vegan’s Black ecofeminist perspective, Harper, 2010; Souza and Hoff, 2022). Nonetheless, the humanist theorizing of critical animal studies still suffers from two major flaws. The first is its whiteness and racial disempowerment (Pimentel-Biscaia, 2022; Malaklou, 2021), the second a focus on overcoming prevailing binary thinking that human rights advocacy always supersedes that of other animals (Cordeiro-Rodrigues, 2022). These flaws deform the study of the overlapping crises of racism and speciesism into a zero-sum game, missing the main point of their interconnected and mutually constituted arising (Cordeiro-Rodrigues, 2022, p. 1076). The result is not just theoretical failure but more importantly practical harm. For instance, animal-fats heavy diets wreak greater havoc on the health of communities of color, while also harming nonhuman animals in the industrial food complex (Harper, 2010).

Given these flaws, we avoid treating human and nonhuman oppression as separate issues. Instead, we recognize that animated films are sites illustrating how racism and speciesism are co-evil. For instance, we propose that the study of the intersectionality of race and species should reflect a balance in joint research, and acknowledgment of their relative magnitude. To achieve such balance, we theorize that animation has habitually portrayed marginalized human groups as inferior, while using nonhuman animal characters to normalize the former’s alleged inferiority, with harms inflicted on both groups. Analyzing the intersectional representations of race and species enables us as critical animal and media researchers (as well as scholars in related fields) to have a more substantive perspective on intersectionality.

Our second main contribution is the development of a practical tool grounded in our theoretical framework. We have created the Media Analysis of Racism and Speciesism Test, or MARS Test, to assist viewers, researchers, and stakeholders in identifying and connecting key aspects of animated films that are trans-species and intersectional. The test is designed to guide users in recognizing the interconnectedness of oppression against humans and other animals. It promotes a balanced approach to simultaneous racism/speciesism research while acknowledging the relative magnitude of these interconnected forms of oppression. The test is described and detailed below.

Our third main contribution is testing how the tool we created (the MARS test) performs in a quantitative/qualitative media analysis that balances trans-species intersectionality. We show the commonalities of oppression when Oscar-nominated animation uses dehumanization and animalization involving people of color and nonhuman animals (for trans-species dehumanization, see Khazaal, 2021; Malaklou, 2020, 2021). We analyze such occurrences in their most egregious to more subtle forms, including when people of color and nonhuman animals appear irrational or when films “define black persons and nonhuman animals alike as things–sentient, but still things–that are seen but not seeing” (Malaklou, 2021, p. 75; italics in original).

Having established the rationale for simultaneously studying racism/speciesism, we turn next to summarizing how the MARS test works as a heuristic.

2 Theoretical framework: stretching standpoint theory, exploring racism/speciesism intersectionality

2.1 Transspecies perspectives and standpoint theory

This article argues for a transspecies perspective on human-animal relations in animated films, which differs from multi- and interspecies perspectives. In scholarly debate, multispecies perspectives acknowledge the coexistence of multiple species within a given study but maintain distinct boundaries between human and nonhuman perspectives (Stokols, 2006). In this approach, humans and other species are treated as separate entities, analyzed independently, and connected only by the overarching topic. Similarly, interspecies perspectives acknowledge interactions between species, however, the human perspective remains the organizing principle, limiting the depth of conceptual integration.

By contrast, transspecies perspectives represent a more deeply integrated framework, akin to transdisciplinarity (Stokols, 2006). This perspective transcends the foundation of multispecies and interspecies approaches, which engage with nonhuman experiences as subsidiary. By developing a shared conceptual framework that more fully incorporates nonhuman agency and ways of being, transspecies researchers study other species while fundamentally reconfiguring their own understanding of knowledge production by centering nonhuman standpoints and epistemologies. This approach offers a transformative lens for rethinking interspecies relationships, challenging anthropocentric hierarchies and species-specific paradigms, and advancing a more equitable understanding of human-animal relationships.

Given its critical importance to transspecies approaches, the concept of nonhuman standpoints is central to our study. Standpoint theory offers a framework for understanding the social positioning of human subjects and how these positions shape knowledge production, perspectives, and the distribution of social power (Harding, 2008). In Sandra Harding’s account, the knower’s social location (e.g., class, race, gender) influences their perspective on social reality, and of issues like gender-based discrimination, racial bias, and intersectional understanding of oppression (Harding, 2008; Collins, 2000).

Adding the concept of animal standpoint from Critical Animal Studies (CAS) broadens Harding’s standpoint theory by acknowledging nonhuman animals as sentient beings, incorporating their experiences, needs, and perspectives as foci of study. We build on this broader theory as it offers us a way to expose the power dynamics in human-animal interactions and social structures that enable animal exploitation. A true animal standpoint theory avoids anthropomorphizing nonhuman animals (Horsthemke, 2018/2024); rather it takes animals’ experiences as subjects of history as a fundamental premise. This premise would make it impossible to claim using the animal standpoint but talk only about the role animals play within human history, or the damages humans suffer as a result of their abuse of animals.

Even though scientific knowledge still has an incomplete grasp of animal standpoints and subjective reality, we urge researchers to take what Chouliaraki (2013, p. 203) calls an “imaginative move towards the standpoint of the other,” in this case, nonhuman animals. Human filmmakers have no foolproof method of directly ascertaining the standpoints of nonhuman animals. In this sense, animal standpoints remain a human construct. Nonetheless, it is possible to work toward approximating such standpoints bolstered by the enormous evidence about the bio-psychological needs and traits of other species coming from the burgeoning scientific literature. Movies could focus on nonhuman animal experiences as sentient beings with their own viewpoints instead of using animals merely as background to human narratives or as metaphorical and symbolic elements. Movies could also highlight the plights of animals who lack rights or wellbeing within broader environmental issues. A caring focus would redefine animal standpoints as a beneficial construct, which is open to refining when new scientific evidence emerges. We term this concept “a constructed animal standpoint.”

Finally, to fully incorporate animal standpoints within a transspecies approach requires exploring how the standpoints and representations of nonhuman animals and humans across race (or gender, etc.) categories are interconnected. C. Richard King et al. (2009) have given us a prime example in Animating Difference: Race, Gender, and Sexuality in Contemporary Films for Children where they show how different ethnic categories are represented in adversarial stereotypes in animal characters and exaggerated predator–prey conflicts.

The transspecies approach illuminates and acknowledges interconnectedness among different forms of oppression. Just as Harding’s standpoint theory links the marginalization of human groups to broader social structures, animal standpoint theory within a transspecies approach connects the exploitation of nonhuman animals to systems of power and domination that also oppress marginalized human groups. This perspective encourages a more holistic approach to social and environmental justice, considering both human and nonhuman animals.

2.2 Speciesism in animation: the missing nonhuman animal standpoint

Animal characters present a paradox in animation. Animated films are one of the two primary modes for representing nonhuman animals (the other being nature documentaries). This makes animation a primary medium for children’s engagement with other animals; however, adults view these films, too. The paradox is that the closer many species are driven to extinction (caused by anthropogenic factors) and the faster species are disappearing from our world, the more animation abounds in nonhuman animals (Yong et al., 2011). Is there anything special about animation that informs this trend? In other words, how do we interrogate material differences in media to shed light on this paradox?

Feature films and nature documentaries are expected to exhibit realism and verisimilitude, but animation is not. That’s why the former face public pressure to abstain from harming nonhumans who are forced to perform as unpaid actors, but there is no such requirement for animation (Lamarre, 2008, I). Given these differences, the qualities of the medium are the basis of eliciting the experience of speciesism in the viewer, with lasting effects (Lamarre, 2011, III). Animation films (from classic Disney to modern Pixar to manga) rely on technical factors to represent characters, such as deformation, realism in motion, and fixed camera. Take, for example, the “squash and stretch” technique that flattens a character/object at impact with a solid surface, stretching the character/object right before and after impact. While this technique simulates an experience of motion in the viewer, it also deforms perceptions of actual animate objects since they do not squash when touching solid surfaces, nor stretch before/after contact. Techniques like these give rise to a new attribute of cartoon animals named “plasmaticity” for being malleable like plasma (Eisenstein, 2012; Lamarre, 2008, I). This quality is “beyond any image, without an image, beyond tangibility—like a pure sensation” (Eisenstein, 2012, p. 46). As a consequence, viewers experience this.

…as an animal force, as vitality, as life itself. Such an experience is not, as so many commentators would have it, an illusion of life. It is a real experience of a force wherein the technical and the vital are inseparable. … call it techno-animism or techno-vitalism, provided we do not take the ‘ism’ to imply that this is … an ideological construction or illusion. It is a new experience of life (Lamarre, 2008, III, 114).

This plasmatic techno-vitalism encourages cruelty via violent deformation of the animal body, inviting viewers to sense, experience, and expect animals’ invulnerability and immortality (Lamarre, 2008, I). Such insensitive portrayal in animation differs greatly from nature documentaries or feature films, which tend to focus on animals’ fragility (e.g., battle scenes with horses, or depictions of predators capturing and killing their prey).

Another prevalent animation technique that helps create the experience of speciesism is the Bambi effect, or drawing animal characters in stylized, anthropomorphic ways so they appear cuter and more child-like (Lutts, 1992). For example, they have a larger humanoid head, big, front-facing eyes, expressive mouth, softer skin, clumsier behavior, higher vocal pitch, and human speech (Dydynski and Mäekivi, 2021). These stylistic choices make cartoon animals’ bodies appear more recognizable to humans and their behavior appears, albeit misleadingly, easier to understand. The same choices also allow filmmakers to incorporate human stereotypes when they represent nonhumans, fusing a mixture of racism and speciesism (Baker, 1993).

Production companies maximize such stylistic techniques in animation as a medium. Cuter animals who never die or get injured ensure audiences’ entertainment and secure companies’ financial profit. But what are the side effects of this deal? How does this new experience of life as altered consciousness (misperception of the natural world) affect a distracted audience, focused on entertainment? Even though animal characters are metaphors, audiences, especially children, do not perceive them as such (Dydynski and Mäekivi, 2021). In fact, cartoon animals form audiences’ sole referent of a particular species, given that many of us are raised in urban environments. Because of audiences’ unfamiliarity with most real animals, cartoon animals create unrealistic expectations about the nature of their referents (real animals), which are heavily influenced by cartoon animals’ plasmaticity and cuteness. Human audiences are thereby invited to expect real animals to look, behave, and communicate like their cartoon representations.

Another effect is the harmful treatment of nonhumans. Unrealistic expectations of cute immortal animals skew human perceptions (and expectations) of interspecies relations. Audiences often envision friendships between predators and prey as well as positive interactions between humans and endearing, soft, easy to understand nonhumans. Expectations of anthropomorphized animal communication shapes human interactions with real nonhumans, with serious consequences for nonhuman animals. Some consequences may be positive, such as the anti-hunting movement inspired by the movie Bambi or increased donations for nonhumans featured in movies (Fukano et al., 2020).

But many if not most portrayals of nonhuman animals are negative, even deeply injurious to them. For instance, 101 Dalmatians (Geronimi et al., 1961; Geronimi et al., 1996) led to many Dalmatian dogs being abandoned or killed, for being ill suited to households with children—the very audiences of the films. Ratatouille (Bird and Pinkava, 2007) triggered a demand for companion rats. Increased demand for certain companion species (e.g., rats, turtles, lemurs, etc.) tends to be harmful to these species as they are often abandoned, with total disregard for their welfare after they age, or when humans discover they are not as cuddly and humanoid as expected. Legal or illegal overbreeding, wildlife trafficking, institutionalized display in zoos, and confinement in private zoos have similar negative consequences. For example, after the movie Madagascar (Darnell and McGrath, 2005), the number of lemurs kept as illegal companions rose sharply, appealing to tourists (Reuter and Schaefer, 2017). Animation, then, often yields negative real-world effects on diverse animals, domesticated and free-living, from petting-zoos or poaching to taxidermy.

Among the most severe effects, however, is disregard for each animal’s life world. If “sensibilization for life’s fragility” is the fundamental ethical and didactic goal for developing a relationship with other animal species, then this goal tends to be compromised in virtual domains (Schmauks, 2000, p. 322). After all, cartoon animals can be neglected, abused, tortured, or killed without any consequences. Animated normalization of violence can worsen audiences’ “alienated attitude towards living beings” (Dydynski and Mäekivi, 2021, p. 758). Perhaps the most severe effect of cartoon animals is disregarding real animal agency, standpoint, and Umwelt, the “species-specific life worlds … comprising all … the animal is capable of perceiving and acting upon” (Dydynski and Mäekivi, 2021, p. 760; Uexküll, 1982). In sum, while it’s presently impossible to incorporate a nonhuman animal standpoint unfiltered through human perception, animation seldom even attempts to come close.

2.3 Racism and racist portrayals in animation

Not only are animation films a uniquely impactful medium for humans’ engagement with other animals, but they are also an important means to either perpetuate or critique racial ideologies, negative stereotypes, and discriminatory outcomes. Here we define racism in animation as a persistent problem of stereotypical, inaccurate, often negative representations of historically marginalized humans or their discrimination in the process of creating animation.

Hollywood’s cartoons and animated films have forged a checkered path in harnessing white privilege and recycling racist cultural narratives (Suñer, 2021; Sperb, 2012). For example, while Lion King (Allers and Minkoff, 1994) invites audiences to perceive Black people as inferior to whites (Betty, 2020; Oudah and Abbas, 2023), A Goofy Movie elevates Blackness to a cultural icon (Dial, 2021; Roy and Saharil, 2020). Overall, though, animation has struggled to eliminate negative stereotypes and the unfair treatment of racial minorities.

Historical stereotypes in cartoons and animated films depicted racialized minorities as villains, noble savages, lazy, exotic, shifty, immoral, sexualized, etc., especially based in Blackface minstrelsy (Ahmed, 2018; Oudah and Abbas, 2023; Leon-Boys, 2023; Valdivia, 2021; Suñer, 2021; Garrett, 2017; Sperb, 2012). In fact, Blackface minstrelsy—which featured white gloves, blackened faces, bulging eyes, disheveled hair, and “huge, carefree tooth-baring” grins (Taylor and Austen, 2012, p. 12)—became the most popular genre of entertainment and “the foundation of American comedy, song, and dance” (Taylor and Austen, 2012, p. 4). By WWII, Blackface minstrelsy largely disappeared, but its typical negative portrayals of minorities seamlessly transferred into new and established mass media like film, radio, and television. Overtly racist images in cartoons were displaced by covert alternatives when vocal anti-racist advocacy created general public awareness of racism, and when increasing production costs and competitive pressure from the new medium of television forced studios to avoid offensive topics. In many cases, studios responded to these pressures by scrubbing cartoons from offensive racial material and de-facto erased Black characters.

In the late 20th century, racist representations in animation acquired a new level of subtlety (Klein and Shiffman, 2006; Green and Alon, 2024), including tokenism, body switches, post-racial or ambiguous narratives. For instance, tokenism is the addition of a character of color as a token, usually a sidekick or a friend. Although it “dips a character in chocolate” (depicting the character’s physical features or some mannerisms), tokenism typically leaves out the character’s inner lifeworld and positionality, making the racial inequalities faced by the character’s community invisible. Similar omission takes place in stories involving a body switch, or where a human person of color is transformed into a nonhuman animal, e.g., princess into a frog, a spy into a pigeon, etc. Once they become nonhuman animals, human characters lose the specificity of their social position as the plot no longer deals with any forms of real discrimination their community faces. Color-blind racism and post-racial narratives also obscure modern racial inequalities in media, because they depict an imagined world beyond racism (Hasinoff, 2008). There, animation frames racism as personal prejudice and avoids labeling it as structural oppression, which masks existing discrimination (Chew, 2019; Goldberg, 2013; Flores et al., 2006; Lu, 2009; Giroux, 2013). In many cases, racist portrayals are subtle because they are just so ambiguous. There is clearly a racial component, but it is unclear exactly what it conveys.

In addition to stereotypes, structural racism is a “categorical reality” in the animated film industry (Kim and Brunn-Bevel, 2023, p. 510). Issues facing voice-over actors of color include barriers to hiring and equitable pay, whereas mainstream distribution marginalizes directors of color and films made by Black or minority creators. From staffing to script production and filming, the animated films industry remains largely white- and male-run (Katatikarn, 2024).

Progressive pro-justice portrayals that challenge colonial narratives are still rare exceptions. In stark contrast to critiques that mainstream animation re-inscribes racism, there are glimmers of justice-oriented change in animated films. For instance, Indigenous animated filmmakers and story tellers represent an important precedent in disrupting settler narratives of colonial genocide (Vellino, 2020). One example is Amanda Strong’s film, Four Faces of the Moon, which restores cultural memory to the cultural memory to the Métis-buffalo interspecies kinship. This movie animates the spiritual connections between Métis and buffalo, recognizing tribal restoration efforts of species and ecosystems in the real world.

3 Methods

The data collection for this article began with identifying all Oscar-nominated films in two categories: “animated feature film” and “short film (animated)” over a period of nine years, from 2016 to 2024. We derived the list of movies from the official website of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.1 The initial sample consisted of 90 films: 45 feature films and 45 short films. We next winnowed to films based on our criteria [see Media Analysis of Racism and Speciesism Test (MARS test) questions, explained below], resulting in a final sample of 52 films. While many films in the final sample have both human and nonhuman characters and were subjected to the full MARS test, some films have only human characters while other films only nonhuman characters. The latter two groups were tested for all MARS questions pertaining to them and excluded from nonapplicable questions. This led to variable tallies for each question but did not affect the total tally of our final sample.

To analyze our final sample, we used a blended method, combining quantitative and qualitative analysis. Our quantitative analysis is based on the new tool we created, the MARS Test, explained below. The qualitative analysis is enhanced by textual readings of the films arising from applying the MARS test. This blended analysis yielded results extracting common themes from movies, illustrating instances of intertwined racist and speciesist harms.

3.1 The MARS test

To aid our quantitative analysis, and to guide subsequent qualitative textual analysis, we developed a new heuristic tool we call Media Analysis of Racism and Speciesism, or MARS Test. It was inspired by the Bechdel Test on gender inequality; the DuVernay Test on racial inequality (

Tucker-Smith, 2022); Debra Merskin’s and Carrie Freeman’s (

Merskin and Freeman, 2020) “Guidelines [on mediated nonhuman animals] for Entertainment Media Producers” and “General Public”; last, we noted extant guidelines on upsetting content, and humane treatment of animals (Doesthedogdie.com, 2025; Humane Hollywood, 2024;

Vaucher, 2024). The MARS test identifies key aspects in which racism and speciesism operate to reinforce cultural and political acceptance of discriminatory and violent actions with real world implications for human audiences’ attitudes and behaviors. To our knowledge, a comparable racism/speciesism intersectionality-focused test is not available. Using guidelines from the above references, we crafted a concise list of 15 questions incorporating intersectional, multidirectional flows of racism and speciesism in media. The questions are organized into three parts, with five questions each: (1) Nonhumans, (2) Humans, and (3) Intersections. After we created the initial MARS test, we tested it on our sample, then made refinements. The MARS test ( see

Table 1) allows researchers, audiences or creators to pass or fail a movie easily. Every question with a YES answer incrementally puts a movie into “yes, this movie is racist/speciesist” (i.e., numerous “yes” answers yield a failed test). “No” answers will help it pass the test, indicating racism and speciesism are low or absent in that movie. Different researchers may have varying answers based on their awareness of racism and speciesism. (“Racialized characters” connote historically marginalized, underrepresented, oppressed, or racialized human characters.)

Part 1: Animated Nonhuman Animals

1.1 Are the nonhuman characters deprived of inner emotional lives and personalities?

1.2 Are the nonhuman characters deprived of their own, species-appropriate goals, i.e., serving humans, solving human problems, or functioning as symbols?

1.3 Are the nonhuman characters captive or treated with violence?

1.4 Do the nonhuman characters fulfill speciesist stereotypes as pests, threats, game, or cute animals/charismatic megafauna?

1.5 Does the film ignore/misrepresent (human and other) threats to nonhuman habitats and welfare?

Part 2: Animated Humans

2.1 Are the racialized characters mostly background or symbols?

2.2 Are the racialized characters whitewashed, deprived of their own goals separate from the white characters?

2.3 Do the racialized characters fulfill harmful, simplistic, or racist stereotypes?

2.4 Do the racialized characters lack depth and complexity?

2.5 Is the lead creative team (e.g., director, writer, producer, production designer, main voice-over actors) unrepresentative of the story’s culture?

Part 3: Animated Intersections

3.1 Does the movie devalue characters in a way where race and species intersect?

3.2 Is the hierarchy of worth of all beings left intact?

3.3 Does the movie hide or make light of the role of animal agriculture in racial oppression?

3.4 Does the movie ignore or downplay the shared roots of racial and species-based oppression?

3.5 Does the movie imply that the struggles against racial oppression and those against species-based oppression are incompatible or in competition with one another?

An important contribution of the MARS test is that it diverges from complex analytical practices. In contrast to common methods of media research, it is simple and accessible. It can be applied by researchers, students, film critics and creators, advocacy organizations, and members of the public (In Appendix A we briefly explain, illustrate, and provide examples of how to apply, each question).

Table 1

| MARS test questions and associated illustration | |

|---|---|

| Part 1: Animated Nonhuman Animals | |

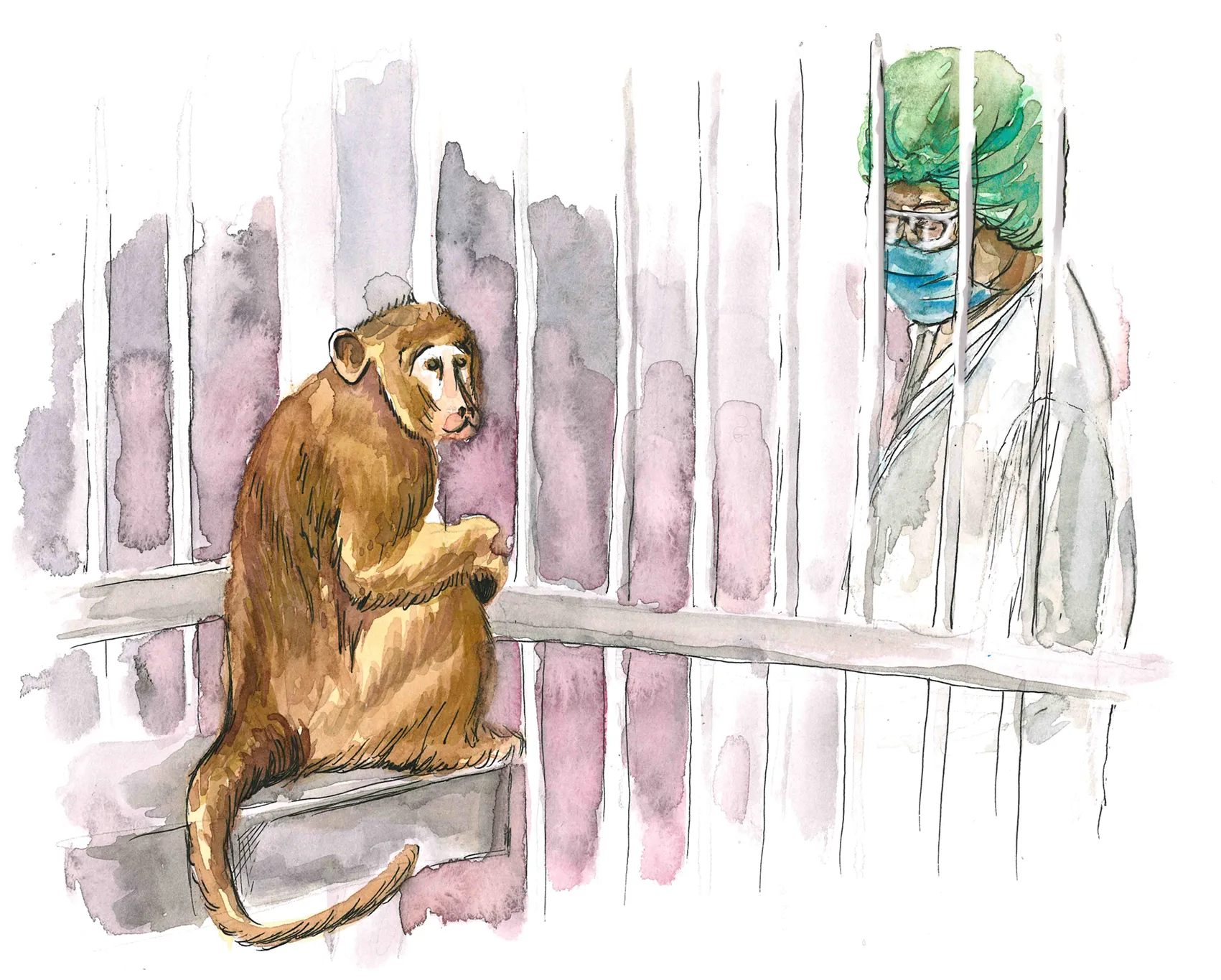

MARS 1.1 Are the nonhuman characters deprived of inner emotional lives and personalities? | |

MARS 1.2 Are the nonhuman characters deprived of their own, species-appropriate goals, i.e., serving humans, solving human problems, or functioning as symbols? | |

MARS 1.3 Are the nonhuman characters captive or treated with violence? | |

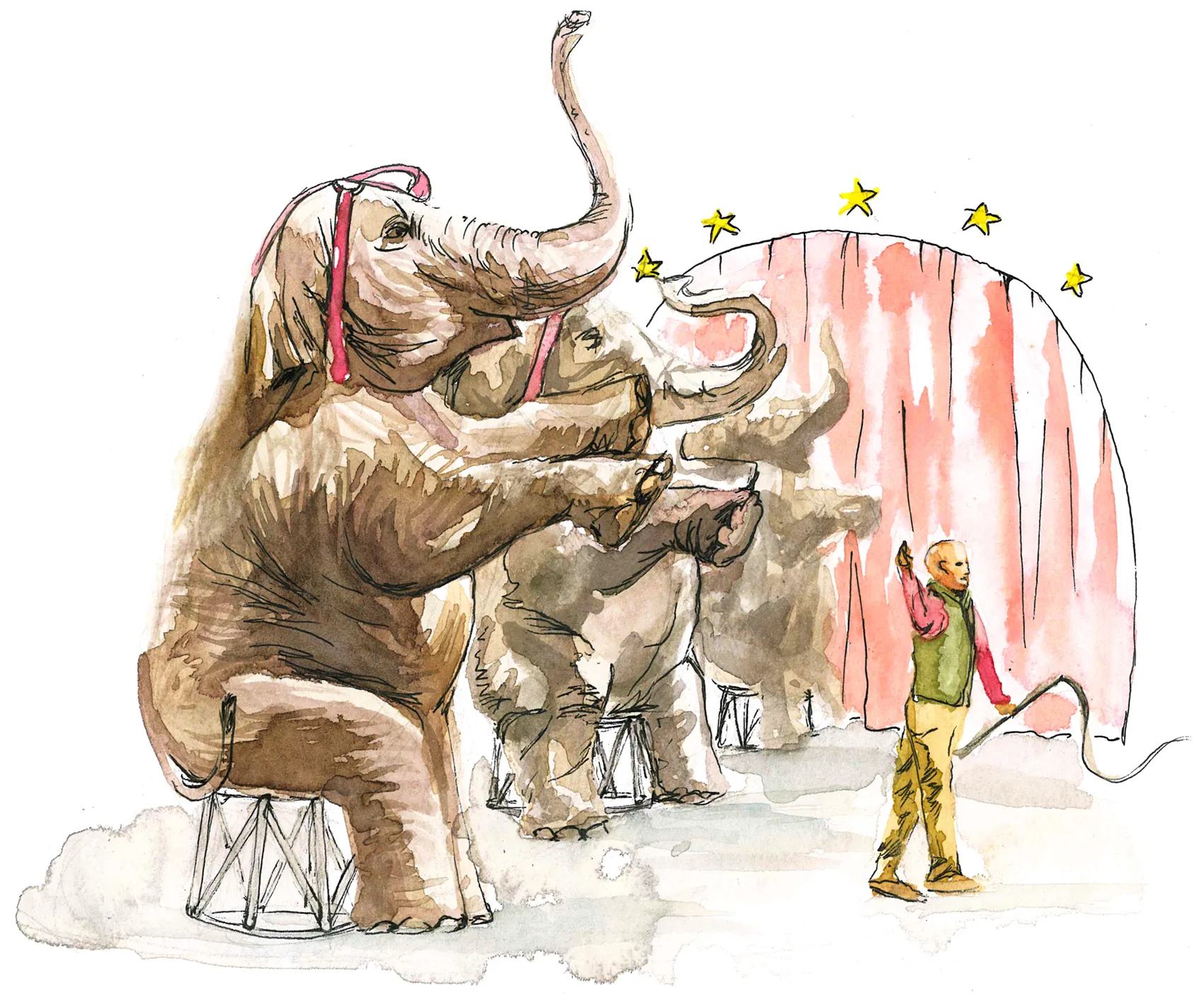

MARS 1.4 Do the nonhuman characters fulfill speciesist stereotypes as pests, threats, game, or cute animals/charismatic megafauna? | |

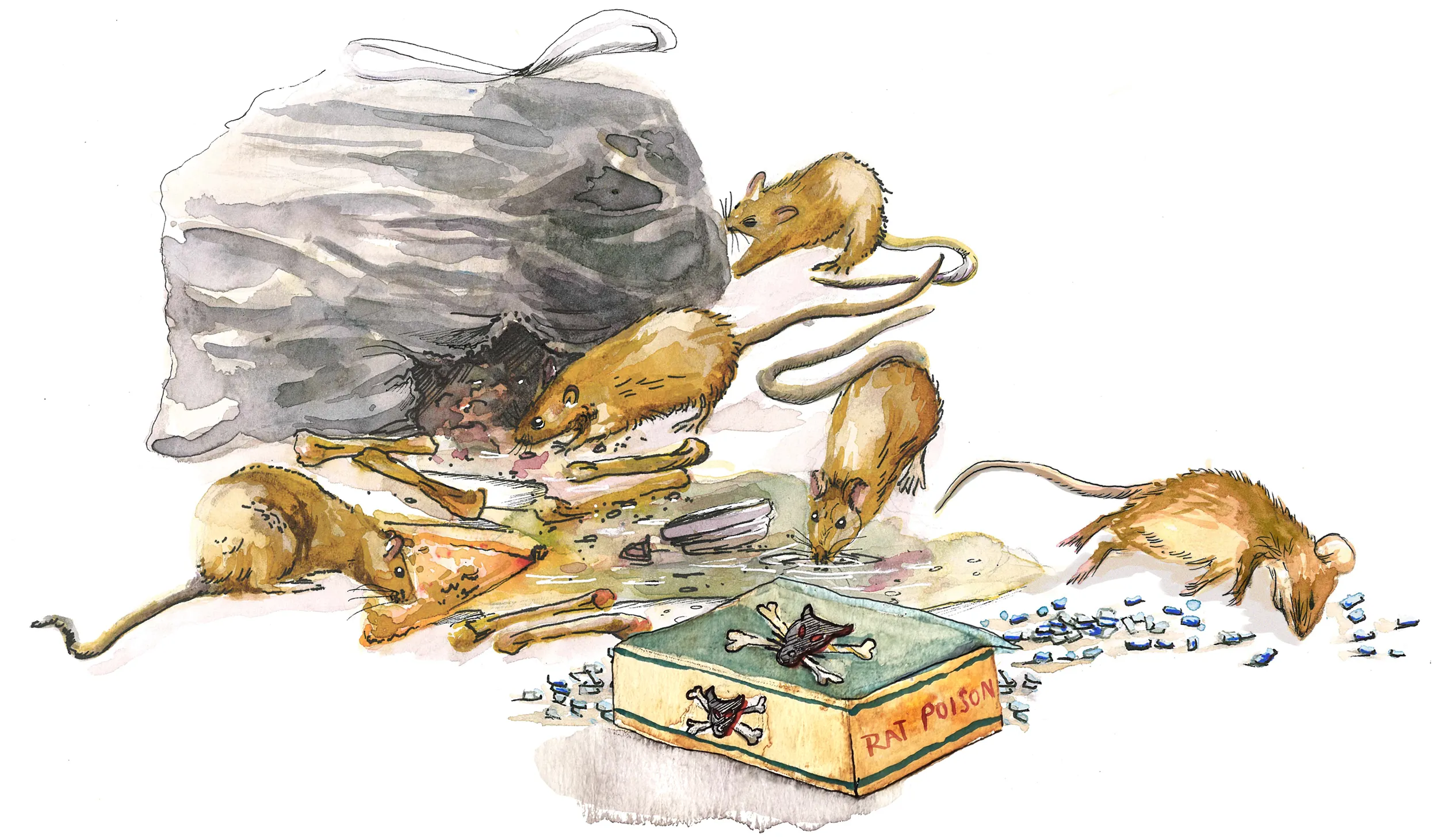

MARS 1.5 Does the film ignore/misrepresent (human and other) threats to nonhuman habitats and welfare? | |

| Part 2: Animated Humans | |

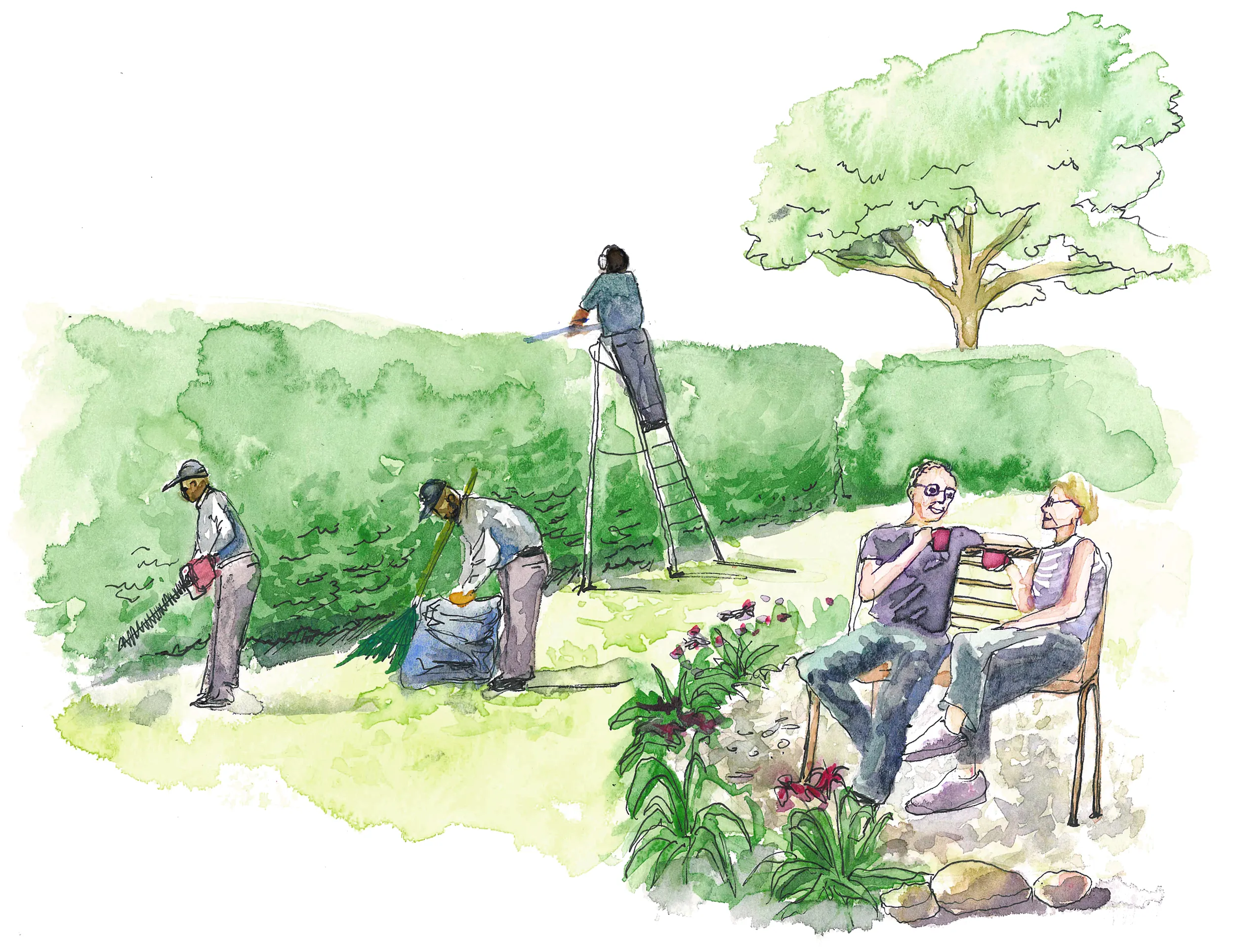

Mars 2.1 Are the racialized characters mostly background or symbols? | |

MARS 2.2 Are the racialized characters whitewashed, deprived of their own goals separate from the white characters? | |

MARS 2.3 Do the racialized characters fulfill harmful, simplistic, or racist stereotypes? | |

MARS 2.4 Do the racialized characters lack depth and complexity? | |

Mars 2.5 Is the lead creative team (e.g., director, writer, producer, production designer, main voice-over actors) unrepresentative of the story’s culture? | |

| Part 3: Animated Intersections | |

MARS 3.1 Does the movie devalue characters in a way where race and species intersect? | |

MARS 3.2 Is the hierarchy of worth of all beings left intact? | |

MARS 3.3 Does the movie hide or make light of the role of animal agriculture in racial oppression? | |

MARS 3.4 Does the movie ignore or downplay the shared roots of racial and species-based oppression? | |

MARS 3.5 Does the movie imply that the struggles against racial oppression and those against species-based oppression are incompatible or in competition with one another? | |

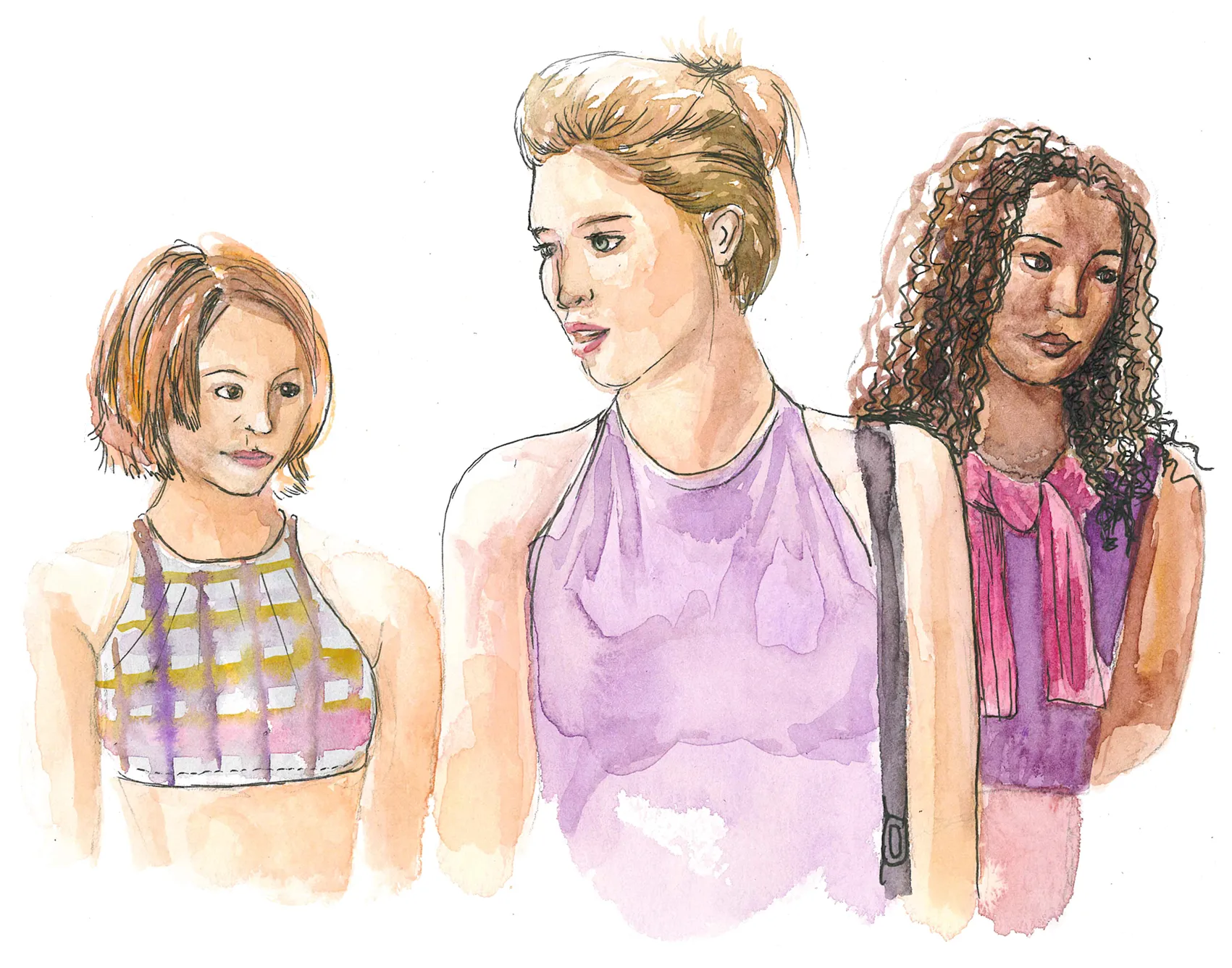

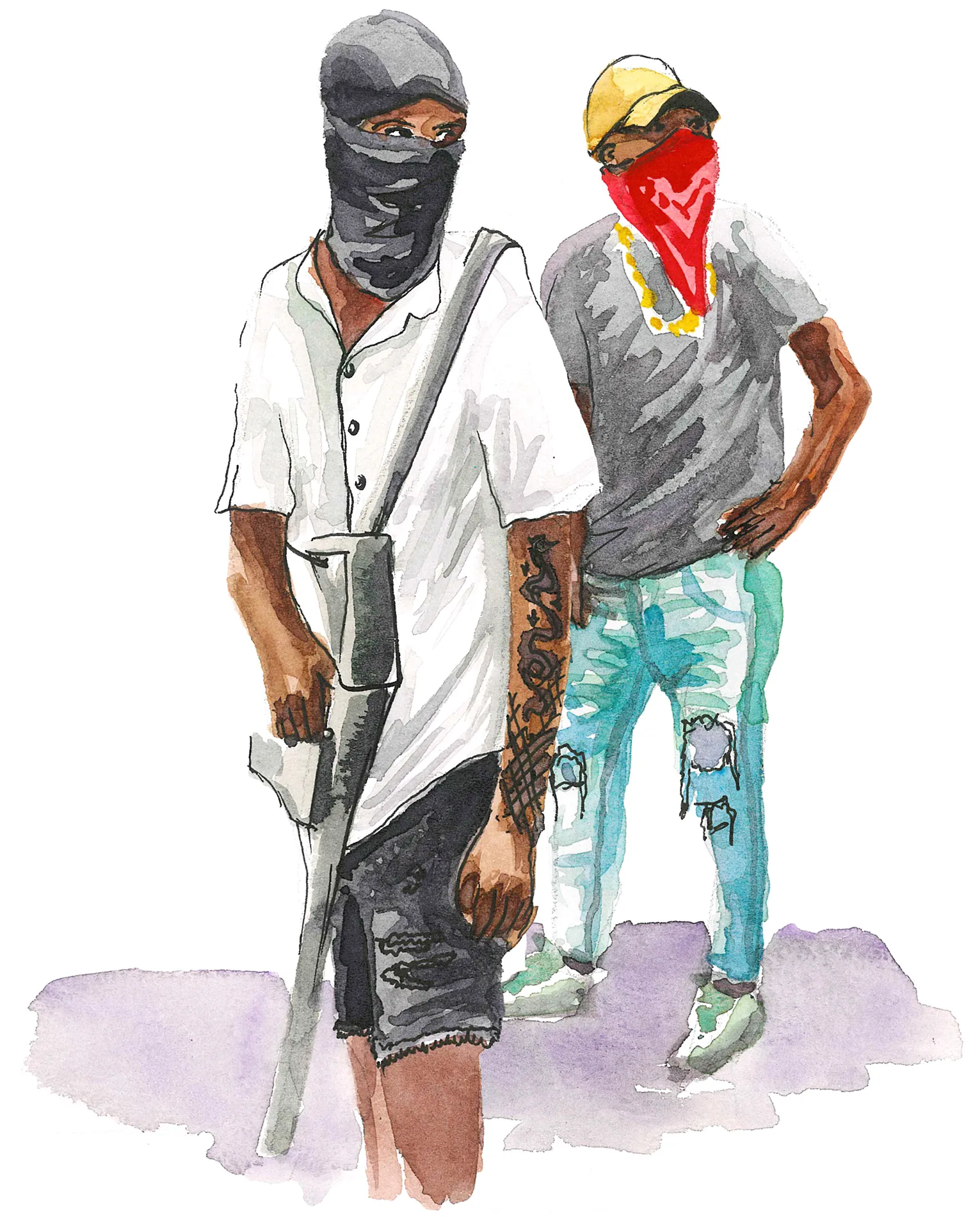

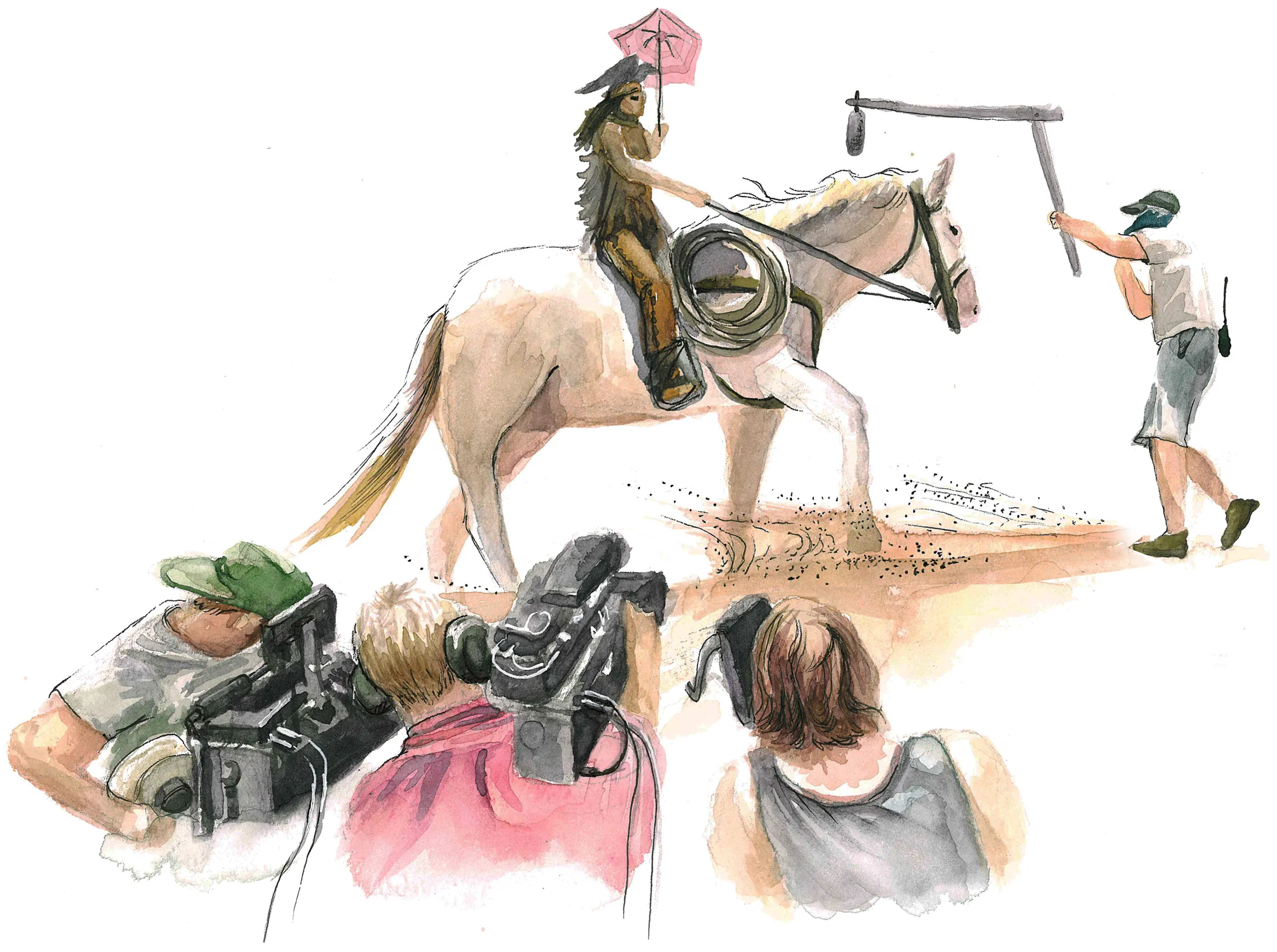

The MARS Test. Copyright of MARS Test (2025): Khazaal, N.; Gorsevski, E; Linné, T.; Copyright of MARS Test drawings (2025): R. Shen.

4 Discussion

This section demonstrates the validity of the MARS test by applying it to our sample in quantitative and qualitative analysis. The former includes all movies in the sample, while the latter focuses on a select few to illustrate implications of the interdependence of racism and speciesism in animated film.

4.1 Applying the MARS test in quantitative analysis: visible difference between racist and speciesist frames

Nonhuman characters in 48% of the final sample lacked inner emotional lives or distinct personalities, contradicting findings from ethological sciences on animal behavior and cognition. About 44% of the movies studied portrayed nonhuman characters having a personal and emotional depth, with Kitbull being a notably constructive example in this category.

In 69% of the films, nonhuman characters did not pursue their own species-appropriate goals independent of humans. Instead, they mimicked human intentions, served humans, or were (mis)portrayed as aiming to harm humans. Only 21% depicted species-appropriate goals, e.g., in Garden Party, Kitbull, and Isle of Dogs.

Being beaten, hunted, tortured, poached, killed, exploited, or captive was the fate of approximately 65% of the nonhuman characters. In contrast, 29% of the films avoided depicting such violence or captivity, showing nonhuman characters as free.

Also 83% of the films reinforced speciesist stereotypes, portraying nonhuman characters as pests, threats, game, cute companions, food, sacrificial objects, or symbols of violence. Only approximately 10% challenged these harmful stereotypes. In the final sample, 71% of the films ignored or misrepresented threats to nonhuman habitats and welfare, such as habitat loss, environmental degradation, poaching, captivity, overfishing, and the effects of global warming. Only around 17% acknowledged these threats and more accurately portrayed serious impacts of human activities on nonhuman animals.

The test results from the questions on racism showed that in approximately 15% of the films in the sample, racialized characters mostly functioned as background and/or symbols. In approximately 39%, racialized characters clearly pursued their own goals separate from white characters, serving the latter’s goals in around 19% of films in the sample. In 40% of the films, racialized characters did not fulfill harmful stereotypes. However, in approximately 24% of the films, some racialized characters were portrayed as simpletons or through cultural clichés. In about 19% of the films, characters of color were found lacking in depth and complexity. Regarding the creative (human) teams behind film-making, 75% of the films had directors, writers, and creators representative of the story’s (human) culture.

Approximately 35% of the films in the sample devalued characters in ways reflecting the intersection of race and species. More than double—77% of the films—never challenged hierarchies of worth that position white male humans at the top of the scale of all beings and nonhuman animals at the bottom. Nearly 39% of the sample either obscured or trivialized the role of animal agriculture in racial oppression. A disregard for, or minimization of, shared roots of racial and species-based oppression appeared in roughly 58% of the films, while only 4% explicitly addressed this issue. Additionally, about 39% of the films suggested that struggles against racial oppression and those against species-based oppression are either incompatible or in competition with one another, while a mere 13% suggested they were interdependent and compatible.

During the nine-year period we examined (2016-2024), some progress was made in reducing racial bias in Oscar-nominated animated films. An increase in non-white main characters and multicultural settings and supporting characters was trending. Their ethnic and racial identity is seldom marked as different, so audiences are invited to identify with them, their lives, struggles, desires, and goals. Greater cultural diversity and sensitivity to cultural specificities are typically normalized through a universal message or experience that the characters go through. For instance, Over the Moon centers on a little girl in a Chinese family, but one of her main problems is that her dad wants to remarry—a problem that many children can potentially identify with. There was an increase in (East) Asian-related or affiliated films, particularly noticeable in the 2019 Oscar season (91st Academy Awards, n.d.), with five nominations (Isle of Dogs, Mirai, Bao, One Small Step, and Weekends). Over the entire period, there were 16 nominations, averaging roughly 1.77 per year (see Table 2: Increase in Oscar Nominated and/or Awarded East Asian-related/Affiliated Animated Films). In the preceding 14 years (2002-2015) since the addition of the animated feature film category in 2002, there were 12 total nominations, averaging 0.85 per year, mostly dominated by Japanese anime and the Kung Fu Panda series. This reflects an approximately 108% increase in nominations in our study period, and if we exclude Kung Fu Panda, then the increase is 149%.

Table 2

| Year of award and total number for that year of east Asian-related / affiliated films | Animated feature films | Animated short film |

|---|---|---|

| 2003 (2) | Spirited Away | Mt. Head |

| 2005 (1) |

| Birthday Boy |

| 2006 (1) | Howl’s Moving Castle | - |

| 2009 (2) | Kung Fu Panda | La Maison en Petits Cubes |

| 2012 (1) | Kung Fu Panda 2 | - |

| 2013 (1) |

| Adam and Dog |

| 2014 (2) | The Wind Rises | Possessions |

| 2015 (2) | Big Hero 6; Tale of the Princess Kaguya | |

| * 2016 (1) | When Marnie Was There | Sanjay’s Super Team |

| * 2017 (2) | Kubo and the Two Strings; The Red Turtle | - |

| * 2018 (1) | The Napping Princess | Negative Space |

| * 2019 (5) | Isle of Dogs; Mirai | Bao; One Small Step; Weekends |

| * 2020 (1) | - | Sister |

| * 2021 (2) | Over the Moon | Opera |

| * 2022 (1) | Raya and the Last Dragon | - |

| * 2023 (1) | Turning Red | - |

| * 2024 (2) | The Boy and the Heron | War Is Over |

Increase in Oscar nominated and/or awarded east Asian-related/affiliated animated films.

*Denotes during our study period.

There was noticeable growth in multicultural and Latin/a/x representation, mainstreaming this demographic. This trend normalizes Mexican and South American settings, the Spanish language, and musical influences of a mainstream family sing-along repertoire. Often such films present a minoritized main character, while other characters represent various ethnic and cultural backgrounds. For example, Turning Red features a diverse cast that promotes empowerment beyond ethnic boundaries. Encanto features a female lead with magical powers, potentially empowering for young girls. Critical response to Encanto claims that because of films like Encanto, West Side Story, Being the Ricardos, “Latino voices are having a moment in U. S. cinema, injecting a diverse set of cultures long ignored by TV, books, movies, video games, stage shows and news media” (Wenzel, 2021). Coco showcases strong Latin/Latina: and Chicano/Chicana representation with its homage to Mexican folk culture and the significant roles of animals, especially as spirit guides or “alebrijes,” inspired by Mexican folk art. Similarly, Puss in Boots: The Last Wish costars a hot-tempered Latina/x character, Kitty Softpaws, voiced by Salma Hayek.

Films like Moana pay tribute to native/Indigenous cultures, with animals ensconced in the film’s cultural setting, reflecting everyday life in Pacific Islander communities. Maui’s transformations into native species emphasize his demigod status and connection to nature. While imperfect, Moana nonetheless represents a significant step forward in Disney’s portrayal of non-Western cultures. Short films like Kitbull portray acceptance and the philosophy of care within multicultural/racially-mixed relations. Zootopia is another example, portraying an idealized multicultural society where different species coexist, while critiquing racism and addressing intersectional issues. The character Hopps faces both gender and species-based discrimination, reflecting the layered nature of prejudice. Additionally, multicultural voice-over work and directing/production roles in animation increased, with films like Turning Red, Elemental, and Over the Moon.

Although African-American and Black characters did not see as much improvement as East Asian and Latin/a characters, there were notable successes. For example, Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse featured a Black central character, Miles Morales, and a multicultural hero cast. Animated shorts, like Oscar winner Hair Love, which inspired a children’s book and spin-off TV show, embrace Afro-hair to counter the discrimination of Black hair styles and racist attitudes casting ethnic hairdos as unprofessional or socially unacceptable. The movie promotes individual and community self-respect, normalizing hair diversity as an expression of civil rights, with a history of losing anti-discrimination court battles but eventually winning social opinion.

While some progress has been made in the representation of diverse characters in Oscar-nominated animated films, significant challenges and biases remain. There are instances where Blackness stands out as more animal than non-blackness, as in Onward’s portrayal of the Manticore (a recognizably Black character, right) versus elf brothers Barley and Ian (recognizably whiter characters, left, as shown at the 20 minutes mark).

One persisting issue in the realm of racial representation in animated films is dehumanization and the unexamined use of nonhuman symbolism. For example, as Table 3 below shows, many animated films (feature films and shorts) from our sample contain biased portrayals of marginalized characters representing humans, nonhuman animals, or hybrids, or other combination beings.

Table 3

| Dehumanizing metaphors, metonymies, nonhuman- symbolism | Animated feature film | Short animated film |

|---|---|---|

| 2016 | Shaun the Sheep - only Shaun is portrayed as agentic and wise (other sheeps misportrayed as dumb). | Boy and the World (urban spaces are full of animal-machine hybrids) |

| 2017 | Moana (her jewel represents phosphorescent seas, and life itself) | The Head Vanishes (fish swim about an elderly lady’s head); Inner Workings (id and ego are creatures living inside each of us) |

| 2018 | Rango (gecko symbolizes modern, urbanized humans needing nature but instead wrecking it with warfare) | Garden Party (frogs frolicking symbolize nature’s return after humans’ violent domination era/Anthropocene ends) |

| 2019 | The Missing Link (Gamu, a mean-spirited yak herder with a chicken on her head as her not-to-be-spoken-of extension; her body union with a nonhuman is reminiscent of dehumanizing portrayals of non-whites and minorities) | Animal Behavior (group therapy of animal characters who talk about sex issues, people with mental health woes are symbolically dehumanized as animal characters) |

| 2020 | Soul (Joe Gardner, a wanna-be jazz player and part-time music teacher, gets trapped into the body of a cat because according to the creators this would allow him to “look at his own life from a different perspective”; while not explicitly dehumanizing, this symbolism doesn’t transcend the boundaries of speciesism as Gardner is uninterested in the cat’s own perspective, just in looking at himself from an outside angle) | Sister (a lonely goldfish in a tiny sterile bowl represents devastating familial loss stemming from the one-child Chinese government policy on population control; the alternative—having a human sister—is represented by adding a second goldfish in an impossibly small bowl, stripping the goldfishes’ experience of captivity, depravity, and physical and emotional pain consuming it as symbolic ornament for human enjoyment turned into symbolic critique of human population control—the very thing that actually would diminish the exploitation of goldfishes and other nonhumans) |

| 2021 | - | Genius Loci (Renee—a Black female—transforms into a disturbed, aggressive dog, and needs the human touch of her sister to resume her human form; a light-skinned vagrant is simultaneously a black horse; non-human are the alter-egos of both Renee and the vagrant, which may be seen as free but also having negative connotations) |

| 2022 | Encanto (Bruno, who is feared by the community for his powers, has curly black hair, a big, prominent nose, and is portrayed with rats or as a rat, which seems to echo WWII Nazi portrayals of Jews) Spider-man Across the Spider-verse (his aunt appears in an alternate universe as a scary pig with sharp, vampire teeth, which is equally racist, speciesist, and sexist) | The Windshield Wiper (doves fly off in a suicide scene as a mere symbol of a human death due to unrequited love, rather than noting that birds’ numbers worldwide are decreasing in part due to birdstrikes into glass skyscrapers, which birds’ vision cannot discern, causing mass bird casualties in real life) Affairs of the Art (the suffering of a pet mouse and death of family dog is made fun of, trivialized) Robin Robin (a unified attack on the family cat is (mis)portrayed as something that is funny. In real life, cats suffer horrible violence at humans’ hands, and are abandoned in large numbers in cities and towns worldwide) Bestia (the protagonist’s otherwise seemingly good natured dog is forced to attack political prisoners being tortured in Chile, circa 1970s dictatorial regime) |

| 2023 | Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio (the Terrible Dogfish is portrayed as a whale-like villain deserving to be blown up at sea, whereas in real life, many species of whales are endangered globally; also in real world actual dogfish are docile, nonthreatening fishes) | The Boy the Mole the Fox and the Horse (Fox, a sly, archetypal character in many racist Jim Crow narratives, voiced by Idris Elba; while this story line is different, the putatively ‘colorblind’ or inadvertent result of this casting of a Black actor as a fox seems to harken to earlier racist narratives in animation) |

| 2024 | Boy and the Heron (Birdman, the flightless human-looking creature inside the heron; at times Birdman appears as a caricature of Blackface, e.g., in one scene he displays huge, round human-like teeth (which birds in real life don’t have) and grins stupidly, like early images of Blackface stereotyping prevalent during the U.S. segregation/Jim Crow era) | In Pachyderme, the cracked tusk symbolizes violence against the human girl, but does not appear to convey the harm to the creature killed for their tusk. |

Examples of Animated Feature and Short Films with Biased, Symbolic Portrayals

Another notable problem is that characters of color are frequently relegated to secondary roles, often portrayed as the Black friend or sidekick. For instance, Corey the Manticore only rediscovers her own unique passion and true self after assuming the position of a sidekick.

The most significant finding from the quantitative application of the MARS test is the clear disparity between a high frequency of speciesist frames versus a much lower occurrence of racist frames in the sample. While animation creators and storylines have become more representative of a given human culture (especially East Asian and Latin), Black creators and storylines have faced greater barriers resulting in fewer gains in challenging racist frames or neglect.

4.2 Applying the MARS test in qualitative analysis

The central findings from our quantitative analysis, that speciesist representations vastly outnumber and surpass racist ones in discursive violence, vilification, and distortion, and that Black narratives face greater representational challenges than those of other minorities, led us to discover key thematic clusters, described below, in our qualitative analysis of the interdependence between racism and speciesism, guided by the MARS test.

Recent data about trending anti-immigrant rhetoric, hate speech, disinformation campaigns, and populist policies (Docquier and Rapoport, 2025) demonstrate their definitive role in the massive global rise of social divisions (Vasist et al., 2023). Through highly segmented media outlets, people no longer see the same reality. Arguably to represent a reality that could appeal to all and increase sales, a number of the Oscar nominees in our sample harken back to the past or gesture toward a mythical refuge. We discuss these choices as two theme clusters—the racial erstwhile and elsewhere bound. Both clusters demonstrate how racism intersects with speciesism by dehumanizing racialized human characters, treating species and races in discriminatory ways that mirror each other, protecting the hierarchy of worth between humans and nonhuman animals, and reaffirming human dominance over other animals. Most importantly, we show that the solidarity between racialized humans and nonhuman animals in these movies is hardly more than a palatable utopia undermining a true nonracist/nonspecialist alliance. The third cluster—the body switch—reflects how deeply the physical representation of Black characters depends on speciesism. We uncovered a number of other clusters, which we do not discuss here for lack of space.

4.2.1 The racial erstwhile

The racial erstwhile is nostalgia for a mythic past of racial homogeneity, that avoids grappling with humans’ inability to deal constructively with racism. Take for instance, Luca, the story of two amphibian boys who shift to human form in order to integrate into human society on the Italian Riviera. Described by creator Enrico Casarosa as a “metaphor for feeling different” (Desowitz, 2021), the movie is also an allegory for immigrants assimilating into racially white Italy. When it came out in 2021, more than 5 million immigrants resided in the country, about 10% of the population, a vast majority of whom had come by sea (Macchi, 2025). Set in the 1950s, the time of Italy’s economic boom when it was still a country of emigrants with very low immigration inflows (Holloway et al., 2021), Luca’s protagonists’ integration is rather simple—they take humanness and whiteness to be the superior, desirable forms of being and are thus finally accepted by the human society. As they let go of the primacy of their fish-like form and embrace human society, the boys’ newfound loyalty helps accelerate the depletion of sea life as they guide human fishermen away from overfished dead zones to new abundant spots. The cost, however, is steep—white cannibalizes racialized, human eats nonhuman species.

Consider another example more thoroughly. In a trailer-type promotion for Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, Sony Pictures features the comic relief character Spider-Ham—voiced by comedian John Mulaney—with dialogue from the movie that includes a remake of the franchise’s original theme song:

JM: My name is Peter Porker.

Song: Spider-Ham, Spider-Ham, friendly neighborhood Spider-Ham, spins a web, that’s the gig, kinda weird ‘cause he’s a pig. Look out! Here comes the Spider-Ham. Life is a plate of bacon; when trouble’s in the making, you’ll find a Spider-Ham.

Spider-Gwen: What a pig!

JM: I’m right here!

Although Peter Porker joined the multicultural cast of Spider-persons from alternative universes, his Spider-alters question his belonging in their superhero community. The bantering, tongue-in-cheek speciesist parody (“plate of bacon,” “what a pig,” “Spider-Ham,” “Peter Porker”) matches the comic strip character of Spider-Ham, who fended off animal-based insults while fighting injustice. The character first appeared in Marvel comic books in 1983 with other anthropomorphic animalized characters like Captain Americat, Hulk-Bunny, and Goose Rider before featuring in a solo series called Peter Porker, the Spectacular Spider-Ham (circa 1983-1987). Despite Spider-Ham’s central role, he was portrayed in speciesist terms, always reducing him to a commercial food product, (issue 26, 1993), which calls him “Spider-Ham 15.88”—a pun on ham’s price, marked down from $20.99. Like the original character, the movie also reifies this nonhuman superhero alter as a commercial food product with an attitude (“I’m right here!”).

The character of Spider-Ham invites audiences to adopt an outlook built on four important features conveying moral ambiguity that are captured in questions 3.2, 3.3, 3.4 and 3.5 of the MARS test (lower status in the hierarchy, human dominance over other animals, ridicule, stereotyping, exclusion from rights, incompatibility of a joint struggle). First, Spider-Ham is stereotyped as uncivilized, uncultured, crude, greedy, gluttonous, dirty, and repulsive—“What a pig”—projecting negative human traits onto caricatured, biologically inaccurate notions of animal behavior (MARS 3.2). Second, he’s expected to aid the human characters and share their responsibilities, yet remains marked as a commodity, reduced to a crude joke (bacon, ham, pork) (MARS 3.3; 3.5). Third, he is met with superficial acceptance but covert rejection—though included in the superhero cast, he is verbally rejected by his supposed equals (MARS 3.2). And last, such denigration mirrors the historical playbook of racist stereotyping where racialized humans are portrayed with animal features and labels (MARS 3.4). Despite his seemingly progressive inclusion, Spider Ham’s character hearkens back to times before animal rights and welfare were on anyone’s explicit agenda, when moral silence and collective denial looked like social harmony. It reaffirms the deep-rooted nature of speciesism and the latter’s profound entanglement with racism.

But this entanglement does not stop at Spider Ham’s character. SpiderVerse invites audiences to adopt a similar morally ambiguous outlook to the lead character Miles—the biracial son of an African-American dad and a Puerto Rican mom. First, Miles is negatively stereotyped—he’s introduced in the movie together with a nonhuman animal, a trope traditionally used to dehumanize Black and racially mixed people as animal-like (MARS 3.1).

Second, he’s marked as a biracial character, “an ambassador for diversity” (McWilliams, 2013). Miles shares the responsibilities of the franchise’s hero but not his idealized status. Miles’s race became controversial among “a previously unknown demographic of racist comic-book readers” (Adalian, 2010). To appease the backlash to racial diversity that Miles channeled, the franchise ensured his “continuous subordination” in multiple ways (Jeffries, 2023). For instance, the original Spiderman, the white Peter Parker, crashes Miles’s movie to question Miles’s adequacy as superhero and the lead of a franchise flick, diminishing him from the Spiderman to a Spiderman (Jeffries, 2023). The end result is to harken back to a time when Black superheroes did not exist, idealizing the institutionalized racism of 1960s America (Pumphrey, 2020) (MARS 3.2).

Third, Miles is met with superficial acceptance but covert rejection. SpiderVerse’s release coincided with waves of Black Lives Matter protests sparked by the police shootings of Tamir Rice, Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Freddie Gray, Philando Castile and deaths in police custody like that of Sandra Bland. At first glance, Miles’s inclusion as a lead is a victory, presenting a Black kid as a hero for everyone. But for him to fully embody that role, both he and his dad must undergo a social transformation. In the original comic strip, the dad is a reformed criminal brought up in an underprivileged community with limited opportunities, which leads him to embrace anti-racist activism and community organizing. SpiderVerse, however, whitewashes the dad as a by-the-book police officer who pursues criminals. In the original comic strip, Miles grapples with mixed feelings about attending a gifted school, following a lottery admission. In the movie, however, he enters the school based on meritorious achievements. Both character edits erase the experience of institutionalized inequities for Black communities (Jeffries, 2023) (MARS 3.4).

Last, the moral ambiguity in SpiderVerse obscures and perpetuates the interdependence between racism and speciesism. On the surface, it suggests that progress such as Miles’s and Spider-Ham’s inclusion in a cast of multicultural characters does question the hierarchy of worth from human/white/male to nonhuman animal and evoke a broader equality among all human races and between humans and other animals. However, beneath this veneer, the movie dangles the subordination and exclusion for any individual or group, whether racialized human or nonhuman as an imminent threat to reassure privileged viewers that the hierarchy remains intact. Of course, the difference in the severity of discursive violence, vilification, and distortion between Spider-Ham as a commercial food product destined for slaughter and consumption and Miles’s whitewashing is undeniable. And such type of difference is reflected across our sample. Their nominal alliance, although significant in its occurrence, is distracting because it fails to jointly address the systemic injustices faced by them.

4.2.2 Elsewhere bound

Like the racial erstwhile, our second thematic cluster—elsewhere bound—helps demonstrate that we cannot look at racism (dehumanization) without also critiquing speciesism. Fewer than one in five movies in our sample acknowledge the threats to nonhuman animals’ wellbeing, habitats, and survival, particularly the anthropogenic causes behind them. Among those that do, Wolfwalkers masterfully reflects the deep common roots of racial and speciesist oppression. But even these movies offer fantastical solutions to the problems they represent.

Wolfwalkers depicts the most traumatic period of Irish history—the 17th century—when English colonial expansion under Oliver Cromwell disrupted Irish society, landholding systems, and local culture. Depicting Irish rebels as shapeshifting wolfwalkers (e.g., the girl Mebh), the plot addresses the simultaneous colonial encroachment on local forests and the extermination of wolves. The Lord Protector—modeled after the historical Cromwell—explicitly reveals how colonial powers perceive Irish rebels and wolves as a unified threat:

Do not fear wild girls [Irish rebels like Mebh] and wolves because tonight we put an end to this. I will burn this forest to the ground. I will lead cannons to the den of these beasts and send them all to hell. We shall prevail […] What cannot be tamed must be destroyed.

The colonial parallel between the Irish rebels and the wolves portrays resistance as equally dignified, regardless of species. The movie depicts the Irish as free-spirited people fighting for independence and freedom, with deep connection to and extensive knowledge of nature—all symbolically represented through the wolves and their struggle to survive in their native forests. This clearly shows how the marginalization of Irish culture under English rule is inseparable from the threat the colonizers pose to wolves. The parallel is embodied in Mebh, who seamlessly bridges both Irish and wolf identities, embodying traits from both species.

The movie also captures the zeal of Irish villagers as they persecute wolves, whom they perceive as a menace to their lives and livelihoods from animal agriculture, as their song reflects:

Wolf, wolf

Kill the wolf

Hunt them far and yonder

Wolf, wolf

Kill the wolf

Till all the wolves are done for

Despite scientific evidence that wolf packs closely resemble human family structures, wolves have been demonized by fear-inducing myths. Historically, after centuries of persecution, wolves were driven to extinction in Western Europe. Only after Poland banned wolf hunting in the 1990s, efforts have been underway to reintroduce them into environments where populations may survive.2

The human-driven threats to wolves in Wolfwalkers realistically mirror broader historical forces that have reshaped mammalian populations worldwide. This transformation began with the extermination of the megafauna, accelerated by rising plant and animal agriculture around 11,000 years ago, which intensified during colonial expansion (15th-19th centuries) and the Industrial Revolution. By the 20th century, industrial animal agriculture, dominated by Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (CAFOs), became the primary food-production mode. As a result, human activity has driven an 85% decline in free-living mammals, leaving them at just 4% of total mammalian biomass, while humans and farmed animals (latter raised for slaughter)—now make up 96%.

With its parallel of wolves and Irish rebels, Wolfwalkers embraces current interests in the more sustainable relationships of local cultures and Indigenous societies with nature and other animals, relationships not exclusively focused on order, dominion, and control, but on respect and co-existence. Coexistence turns on its head the idea of an invasive species/group. In the clash between Indigenous cultures and colonial forces, it is the latter that are invasive and destructive.

Despite Wolfwalkers’ realistic portrayal of wolves’ plight, the film implies that simply relocating them elsewhere—ensuring they no longer cross paths with villagers—can serve as a sufficient alternative to the wolves’ extermination. Continued human encroachment into habitats of free-living animals—especially with rapid expansion of urban areas since the 19th century—has made relocating wolves elsewhere a utopian solution. There is no remaining land on Earth, free from human ownership, that can truly separate wolves from humans. That’s why the wolf song’s rewrite at the end of Wolfwalkers may allow viewers to feel a sense of justice prevailing, while ringing hollow considering the impractical “solution” it references:

Wolf, wolf, howls the wolf

Wolf, wolf, run free

If the movie’s wolves and Irish rebels of colonialism are ultimately one, then is not there a place for them after we survive colonialism?

Similarly, How to Train Your Dragon: The Hidden World portrays threats to fictional dragons that closely mirror the perils wolves experience. Dragons in the movie are coerced into submission, captured, exploited as weapons or for profit, and relentlessly hunted to the brink of extinction. As human territories expand, dragons are driven deeper into hiding. Yet, despite their retreat, human hunters persist in tracking them down. The film suggests that the only viable solution is for dragons to vanish from human spaces entirely, seeking refuge in a hidden world elsewhere beyond human reach.

Instead of confronting human culpability for habitat destruction and species extinction, these narratives absolve humanity, suggesting nonhumans must simply flee. This solution imagines animals as willing refugees, erasing the trauma of their forced displacement and the harm they suffer at the hands of humans.

4.2.3 The body switch

Our last cluster—the body switch—is an issue because it is a subtle expression of racist/speciesist representation in animation. It robs the racialized characters of their social position and may hide real forms of discrimination that the characters or their communities face. Because it is so often connected to the Black community, to some degree, it has become a measure for its advancement toward racial justice. There are as many instances of white character body-switch (Nimona, Luca, Wolfwalkers) in our sample as there are of racialized characters (Soul, Turning Red, Genius Loci). In addition, in some movies like Encanto, the co-habitation and intimacy between racialized humans (Bruno) and nonhuman animals (rats) resemble the body switch. Although this 50/50 split may seem like equal representation, it falls short for two key reasons. First, Black characters appear in two of the six movies, which shows how closely they continue to be associated with animality. Given box office profits, even these instances are problematic, calcifying historical associations between Blackness and animality.

Second, body switching empowers characters differently depending on their race. It helps white characters amplify their abilities, paving their paths to success. For example, Nimona turns into various megafauna to demolish confined spaces, evade her chasers, and aid wrongfully convicted Ballister Blackheart; while Luca (who resembles aquatic salamander in water but turns human on land) uses his sea powers to guide fishermen to spots with plenty of fishes. In Wolfwalkers, Robyn gains strength, speed, bravery, and an inner moral compass whenever she switches into a wolf.

By contrast, the body switch disables racialized characters. When Soul’s Joe Gardner turns into a cat, he loses his vocal cords and the ability to articulate words and his fingers and the ability to play the piano, breaking his commitment to join renowned jazz musician Dorothea Williams. Turning Red’s Mei Lee becomes a giant panda when she gets angry or emotional, losing control and wreaking havoc, while Genius Loci’s Black character Reine turns into a snarling dog after a white friend accuses her of theft. No longer able to make sense of the confusing and menacing cityscape as a dog, Reine loses her ability to speak, just like Joe. She appears aggressive and threatening to those around until her sister helps her regain human form and overcome her feelings of powerlessness and alienation. In all these cases, the protagonists lose an essential human ability, rather than gaining nonhuman strength. Instead of gaining super-power, they gain super-deficiency. This difference is a fundamental obstacle to racially sensitive representation.