- 1Department of Computer Science, School of Mathematics, Statistics and Computer Science, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa

- 2Department of Computer Science, Data Science, and Information Technology, Sol Plaatje University, Kimberley, South Africa

This study presents a hybrid neuro-symbolic framework for COVID-19 detection in chest CT that combines multiple deep learning architectures with rule-based reasoning and domain-adversarial adaptation. By aligning features across four heterogeneous public datasets, the system maintains high, site-independent performance (average accuracy = 97.7%, AUC-ROC = 0.996) without retraining. Symbolic rules and Grad-CAM visualizations provide clinician-level interpretability, achieving near-perfect agreement with board-certified radiologists (κ = 0.89). Real-time inference (23.4 FPS) and low cloud latency (1.7 s) meet hospital PACS throughput requirements. Additionally, the framework predicts key treatment outcomes, such as intensive care unit (ICU) admission risk and steroid responsiveness, using retrospective EHR data. Together, these results demonstrate a scalable, explainable solution that addresses cross-institutional generalization and clinical acceptance challenges in AI-driven COVID-19 diagnosis.

1 Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) has shown remarkable potential in healthcare, contributing significantly to disease diagnosis, treatment planning and medical imaging analysis (Mansour et al., 2021; Salammagari and Srivastava, 2024). One notable application has been in COVID-19 detection using CT scans (Alsharif and Qurashi, 2021), where models have been designed to help radiologists identify lung abnormalities associated with the virus (Shriwas et al., 2025), thereby improving diagnostic speed and accuracy. Among these, deep learning models, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNN), have demonstrated exceptional accuracy in identifying infection patterns (Zhao et al., 2021) in annotated datasets. However, despite such models' effectiveness, they suffer from poor generalizability when deployed across different hospitals (Zhang et al., 2022), dissimilar imaging devices (Li et al., 2023) and diverse patient demographics (Vrudhula et al., 2024), leading to reduced reliability in real-world applications (Nazir et al., 2024).

Recent studies have proposed alternative methods for COVID-19 detection, further enriching the body of AI-driven diagnostic research. Contrast-limited adaptive histogram equalization (CLAHE) enhancement applied to chest-ray images has been shown to improve CNN-based classification performance (Altan and Narli, 2022). Local histogram equalization (LHE) offers another promising preprocessing strategy; a systematic analysis demonstrated that applying LHE to segmented right- and left-lung lobes before transfer learning significantly raised classification accuracy across the VGG16, AlexNet and inception architectures, with optimal disk factor tuning markedly increasing the discriminative power of pretrained CNNs for COVID-19, pneumonia and normal cases (Narli, 2021). Yet another technique, a novel diagnostic approach named VECTOR, analyses Velcro-like lung sounds to detect COVID-19, achieving encouraging predictive results without relying on imaging data (Pancaldi et al., 2022). While each of these methods presents innovative solutions, they do not integrate symbolic reasoning or address the generalization challenges caused by domain shifts across datasets.

To improve interpretability, symbolic AI has been explored as an alternative or a complement to data-driven methods. Unlike deep learning, which learns from data patterns, symbolic AI encodes expert-defined rules and logic, resulting in more transparent decision-making. For COVID-19 detection, symbolic AI can encode radiological knowledge and predefined rules to assist in diagnosing an infection based on established medical criteria (Fadja et al., 2022), such as the presence of bilateral ground–glass opacities or the absence of pleural effusion. However, its dependence on manually defined rules makes it rigid and less adaptable to new imaging datasets (Lu et al., 2024), as any change in clinical presentation requires manual updates to the knowledge base (Najjar, 2023). To address the limitations of both deep learning and symbolic AI, a previous study introduced hybrid AI models (Musanga et al., 2025) that combined deep learning's feature extraction capabilities with symbolic AI's interpretability for COVID-19 detection using CT scans. The hybrid AI model leveraged deep learning to recognize complex patterns in medical images while integrating symbolic AI to ensure transparent decision-making and rule-based validation (Musanga et al., 2025). However, the model exhibited limited generalizability across multiple datasets. This gap poses a significant challenge in deploying robust and fault-tolerant explainable AI systems for real-world clinical use (Rather et al., 2024), especially during pandemics such as COVID-19, where data variability is inevitable. The subject of this study is, therefore, the development of a hybrid AI model integrated with domain adaptation techniques and transfer learning to enhance performance, interpretability and generalizability across multiple clinical datasets for COVID-19 detection using CT scans.

Building on a previously developed hybrid AI framework that integrated deep learning for feature extraction and symbolic AI for interpretability in COVID-19 detection using CT scans, this research extends the model by incorporating domain adaptation and transfer learning to enhance robustness and fault tolerance across various clinical datasets. This integration mitigates the challenges posed by domain shifts in CT scan datasets, ensuring that the AI model remains reliable across diverse healthcare environments. By integrating deep learning, symbolic reasoning, and domain adaptation techniques, this study aims to develop an interpretable and generalizable COVID-19 detection framework that is suitable for real-world deployment.

1.1 Main contributions

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

• Unified Hybrid Neuro-Symbolic Framework: We propose the first end-to-end hybrid framework that integrates ResNet-50 feature extraction, U-Net lung segmentation, deformable convolutions, and attention mechanisms with an explicit rule-based reasoning layer. This integration, not previously reported in COVID-19 CT analysis, simultaneously achieves high diagnostic accuracy (97.7%) and full interpretability, providing rule-level transparency for clinical decision support.

• Domain-Adversarial Transfer Learning Module: We design a novel feature-alignment module that mitigates distribution shifts across four heterogeneous CT datasets. This component improves cross-domain F1 scores by up to 8.4% compared with state-of-the-art baselines, demonstrating robustness and reliability in diverse clinical environments.

• Clinical-Grade Validation and Real-Time Deployability: Through multicentre evaluation, the proposed framework demonstrates near-perfect agreement with board-certified radiologists (κ = 0.89, 95% CI 0.85–0.92). Furthermore, it achieves real-time inference (23.4 FPS) and low cloud latency (1.7 s), satisfying hospital PACS throughput requirements and supporting seamless clinical integration.

• Outcome-Prediction Extension: Beyond diagnostic detection, the framework is extended to forecast critical treatment outcomes such as ICU admission risk and steroid responsiveness from retrospective EHR data. This highlights the versatility of the approach and its potential impact on both diagnosis and patient management.

These advances collectively provide a production-ready, interpretable AI solution that addresses the dual challenges of clinical accuracy and cross-institutional generalizability in medical imaging.

2 Literature review

The use of AI tools in clinical diagnostics, particularly in medical imaging, is not novel. The assistance of AI tools has been considered in rapid detection of diseases such as COVID-19 (Chen and See, 2020).

2.1 Deep learning for COVID-19 detection

Among the dominant AI tools considered, deep learning has demonstrated exceptional performance in analyzing CT scans to identify pulmonary infections related to COVID-19 (Lee et al., 2023). Convolutional neural networks have established themselves as the primary architecture for automated COVID-19 diagnosis from medical imaging data. Recent ensemble approaches combining VGG16, DenseNet121, and MobileNetV2 have achieved exceptional performance, with reported accuracies reaching 98.93% through sophisticated feature fusion strategies (Bani Baker et al., 2024). Vision transformers have further advanced the field by modeling long-range pixel dependencies through self-attention mechanisms, with recent implementations achieving over 99% accuracy on curated CT scan datasets (Gawande et al., 2025).

The development of deep learning architectures for COVID-19 detection has increasingly incorporated advanced preprocessing and enhancement techniques. Studies utilizing EfficientNet-B4 models with transfer learning have demonstrated 97% accuracy on diverse X-ray imaging datasets, highlighting the continued relevance of convolutional architectures in medical image analysis (Khalil et al., 2024). However, these achievements are often constrained by dataset-specific optimizations that limit generalizability across diverse clinical environments. Additionally, despite their effectiveness, deep learning models struggle with poor generalizability when deployed in varied clinical settings (Zhang et al., 2022). Domain shifts, such as differences in imaging protocols, scanner hardware, and patient populations, cause significant degradation in deep learning model performance when transitioning from the training environment to deployment (Singhal et al., 2023). The need for alternative tools is thus apparent.

2.2 Alternative image enhancement techniques

Image preprocessing-based enhancement techniques have emerged as powerful alternatives to improve diagnostic accuracy. Using CLAHE with transfer learning has led to remarkable results. For instance, Altan and Narli (2022) introduced a CLAHE preprocessor that preceded transfer learning on popular CNN backbones. Using 3,615 COVID-19 and 3,500 normal chest X-rays, the authors performed a systematic grid search over 71 CLAHE parameter pairs; the best setting (disk = 56, clip limit = 0.2) increased the VGG-16 accuracy to 95.9%, outperforming the raw-image baseline by approximately 3% and demonstrating that a single well-tuned contrast routine could rival considerably deeper networks. Furthermore, advanced CLAHE implementations paired with gamma correction demonstrated even higher performance, reaching 99.03% accuracy with DenseNet201 on chest radiograph datasets.

Local histogram equalization has been shown to enhance subtle texture features in chest-ray images prior to deep learning classification. In Narli (2021), LHE with varying disk radii was applied to segmented lung lobes before fine-tuning VGG-16, AlexNet, and inception networks on a three-class (COVID-19, pneumonia, and normal) dataset. The study demonstrated that selecting an appropriate disk radius for LHE preprocessing significantly improved classification accuracy across all architectures, underscoring the importance of local contrast enhancement for pretrained CNN performance in COVID-19 detection.

While radiological modalities dominate the AI literature, recent research has explored lung-sound analytics as a radiation-free adjunct. Pancaldi et al. (2022) proposed VECTOR, an algorithm that detected “Velcro-like” crackles—acoustic biomarkers of COVID-19 pneumonia—from digital auscultation recordings. After a Mel-spectrogram conversion and a handcrafted feature extraction, the algorithm achieved 85.7% positive predictive value (PPV) and 64.3% negative predictive value (NPV) in a 28-patient cohort, with an overall diagnostic accuracy of 75%. The system demonstrated 70.6% sensitivity and 81.8% specificity compared with imaging-based ground truth (lung ultrasound, chest X-ray, and high-resolution computed tomography). Although the positive predictive value lagged behind that of high-end CT-based systems, VECTOR delivered instant bedside screening and could be used as infrastructure, making it attractive for triage in resource-limited settings.

Fuzzy logic-based enhancement methods represent another significant advancement in COVID-19 detection. Fuzzy image enhancement techniques using fuzzy expected value and fuzzy histogram equalization have shown substantial improvements in CT image quality for COVID-19 pneumonia detection. These methods achieved 94.2% accuracy with 96.7% precision by enhancing ground-glass opacity (GGO), crazy paving, and consolidation patterns in CT scans. Fuzzy-based adaptive convolutional neural networks (FACNN) have further advanced this approach, reducing false positive rates and achieving superior performance compared to traditional CNN baselines. These methods illustrate that judicious preprocessing can markedly increase baseline CNN accuracy; however, they do not directly address cross-institutional generalization or provide rule-level explanations.

2.3 Symbolic AI approaches

Symbolic AI utilizes structured rules, logical inference, and domain ontologies to guide decision-making (Confalonieri and Guizzardi, 2025). Systems in this domain have shown promise in incorporating expert knowledge for COVID-19 diagnosis and improving the transparency of model predictions (Wang et al., 2025). For example, rule-based reasoning can be used to mimic radiologists' diagnostic criteria for identifying ground-glass opacities and consolidation patterns in CT scans (Rana et al., 2022). However, symbolic AI systems lack the flexibility of deep learning models and have limited scalability. Updating knowledge bases to accommodate novel variants of disease presentation or changing imaging practices often requires manual intervention, which restricts such systems' adaptability in dynamic clinical environments (Chander et al., 2024).

Recognizing the strengths and limitations of both paradigms, recent studies have explored hybrid AI models that integrate deep learning and symbolic reasoning to balance performance and interpretability. A hybrid framework combining CNN-based feature extraction and symbolic reasoning for COVID-19 detection using CT scans was proposed earlier (Musanga et al., 2025). This integration enabled the system to not only achieve high diagnostic accuracy but also provide interpretable outputs consistent with clinical reasoning. However, such hybrid models are often developed and validated on static datasets, which limits their capacity to generalize across different healthcare settings with diverse imaging characteristics.

2.4 Domain adaptation in medical imaging

To overcome the challenge of domain variability, domain adaptation and transfer learning techniques have emerged as powerful solutions. Domain adaptation focuses on reducing the distributional gap between source and target datasets by aligning feature spaces (Guan and Liu, 2021), often using adversarial training or statistical distance minimization (Bellitto et al., 2021). Transfer learning enables models trained on large-scale imaging datasets to be fine-tuned for specific tasks such as COVID-19 detection, significantly reducing the need for annotated data (Wang et al., 2025).

More recently, Turnbull and Mutch (2024a) introduced pseudolabeling with 3D ResNet and Swin Transformer architectures to address domain shifts; they achieved a best cross-validation mean F1 score of 93.39% in the Detection challenge and a mean F1 score of 92.15% in the Domain Adaptation challenge of the COV19 CT-DB dataset. Bougourzi et al. (2024) combined lung-infection segmentation (via PDAtt-Unet), three 3D CNN backbones (Hybrid-DeCoVNet, 3D-ResNet-18, 3D-ResNet-50), ensemble methods, and test-time augmentation. Their best models achieved better performance than the baseline approach by 14.33% in terms of F1-score for COVID-19 Detection Challenge and 14.52% for COVID-19 Domain Adaptation Challenge. Lim et al. (2024) introduced the KDViT framework, which applies knowledge distillation to Vision Transformers (ViTs) in order to transfer the rich contextual representations of large teacher models into lightweight student networks. This approach combines the global dependency modeling strength of ViTs with the efficiency of compact architectures, thereby reducing computational overhead without sacrificing diagnostic accuracy. KDViT achieved high accuracy rates of 98.39%, 88.57%, and 99.15% on the SARS-CoV-2-CT, COVID-CT, and iCTCF datasets, respectively, with precision and recall consistently near 98%, underscoring the effectiveness of distillation-based transformer methods for COVID-19 detection. Fouad et al. (2025) advanced interpretability by aligning volumetric CT models with BSTI radiological reporting categories and embedding visual heatmaps consistent with radiologists' reasoning. They obtained 75% overall accuracy for four classes (“Classic,” “Probable,” “Indeterminate,” “Non-COVID”), which rose to 90% after excluding the “Indeterminate” category. While these studies advance performance, domain adaptation and interpretability are typically pursued in isolation, and integration with symbolic reasoning frameworks remains rare.

2.5 Research gap

A review of the current literature reveals fragmented approaches to building robust, interpretable, and adaptive AI systems for COVID-19 detection. Although deep learning, symbolic AI, domain adaptation, and transfer learning have advanced individually, few studies have integrated all four components into a unified framework. Most existing models lack the flexibility to adapt to domain shifts while maintaining clinical interpretability. Therefore, a significant research gap exists in the development of a hybrid AI system that not only combines deep learning and symbolic reasoning but also incorporates domain adaptation and transfer learning techniques to enhance generalizability across multiple diverse COVID-19 CT scan datasets.

3 Materials and methods

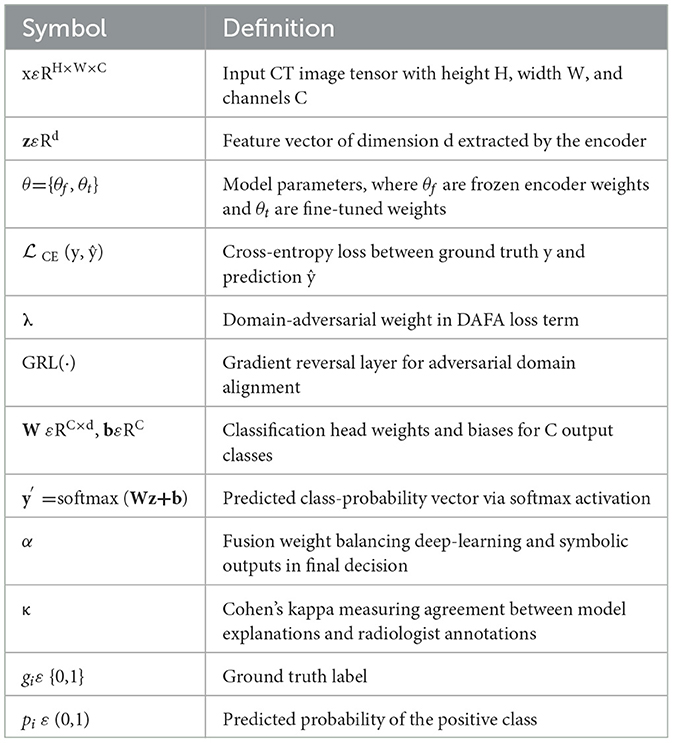

To ensure clarity in the mathematical formulations and algorithms described in this section, all symbols and notation are summarized in Table 1.

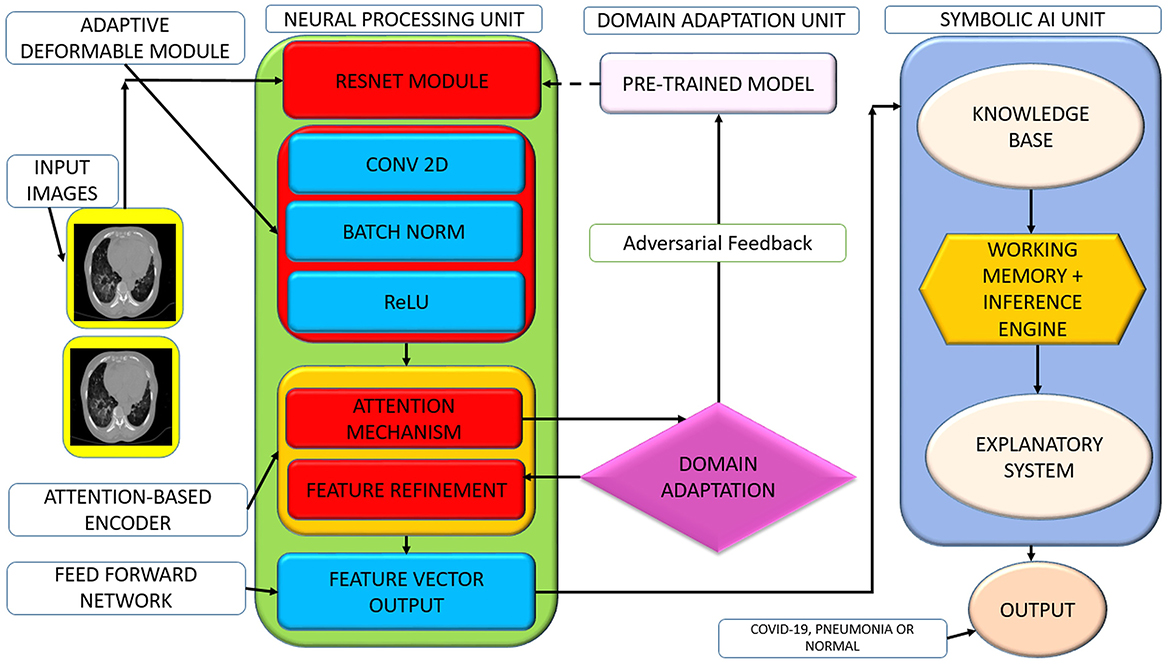

3.1 Design of the hybrid AI model

Building on a previously proposed hybrid AI system that combined deep learning and symbolic AI for clinical diagnostics (Musanga et al., 2025), this study extends the framework by incorporating domain adaptation techniques to improve model generalizability across diverse medical datasets. Figure 1 presents the enhanced hybrid neuro-symbolic architecture with integrated domain adaptation capabilities.

The system processes chest CT scans through multiple integrated components: (1) Preprocessing pipeline applies intensity normalization, spatial augmentation (rotation ±15 °, scaling), and standardization to 224 × 224 pixels. (2) U-Net segmentation isolates lung parenchyma from surrounding anatomical structures (ribs, mediastinum) for focused analysis. (3) Feature extraction backbone combines ResNet-50 (frozen early layers, fine-tuned final block), adaptive deformable modules (ADM) for irregular lesion boundaries, and multi-head attention encoders for spatial feature weighting. (4) DAFA uses gradient reversal layers to align feature distributions across heterogeneous datasets, ensuring cross-institutional robustness. (5) Dual reasoning paths process extracted features through both a neural classifier and symbolic reasoning engine containing clinical rules (e.g., bilateral ground-glass opacity detection). (6) Decision fusion combines deep learning predictions and rule-based outputs using weighted averaging (α parameter). (7) Interpretability layers provide Grad-CAM visualizations highlighting relevant anatomical regions and rule activation traces for clinical transparency.

3.1.1 Input acquisition and preprocessing

The input images are chest CT scans formatted as 3D tensors xεRH×W×C, where the spatial dimensions (height H, width W) combine with channel depth C to form the complete representation. Consistency in preprocessing is critical to ensure reproducibility and minimize variance caused by scanner types, imaging parameters, and institutional protocols. All images are resized to a standard dimension of 224 × 224 pixels to match the input size of the ResNet-50 network. Following resizing, pixel intensity values are normalized to the range [0,1], stabilizing the training process and ensuring numerical uniformity across images.

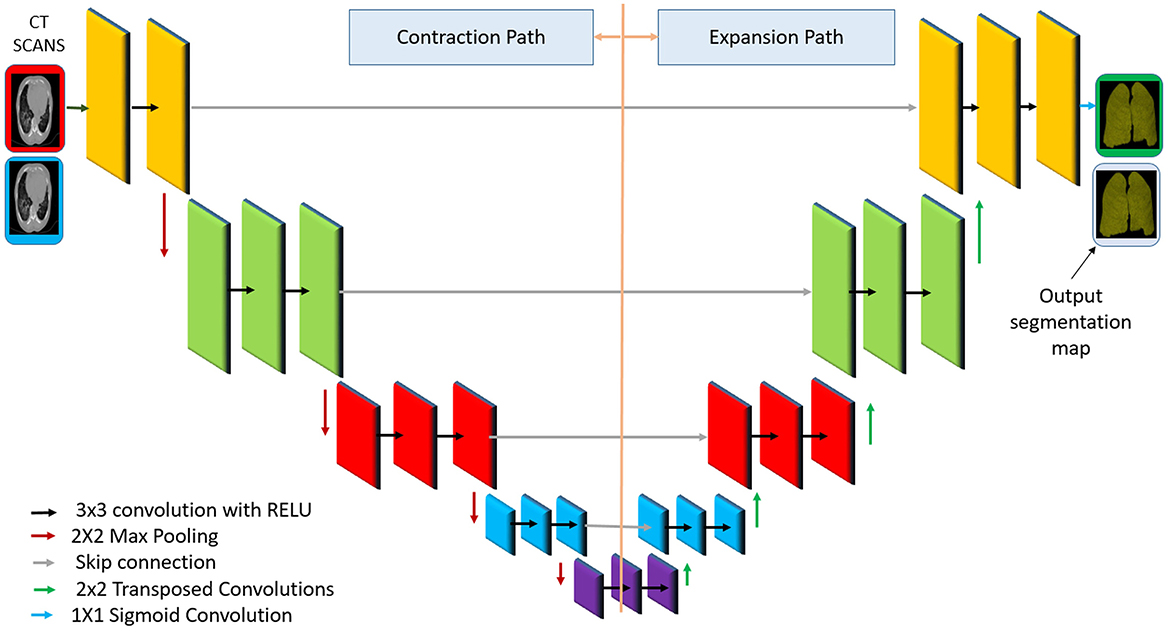

To enhance model generalizability and simulate real-world heterogeneity, the training dataset undergoes an augmentation pipeline consisting of spatial transforms (O = ±15 °, H/V–flip, scale ε[0.9, 1.1], shift ≤ 5%) and intensity perturbations (−0.1, +0.1), brightness (−0.2, +0.2)]. These augmentations expose the model to spatial and visual variability, reducing the risk of overfitting to specific training conditions. A key enhancement in this stage is the application of a segmentation model based on U-Net. This model isolates the lung parenchyma from the surrounding structures such as the rib cage, the mediastinum and other irrelevant regions. Figure 2 illustrates the architecture of the U-Net model used for this segmentation task, showing the encoder–decoder structure with skip connections that preserve spatial resolution while enabling hierarchical feature learning.

Figure 2. Diagram of the U-Net architecture for lung segmentation, adapted from the original model (Ronneberger et al., 2015).

The network has a U-shape encoder–decoder structure with symmetric downsampling and upsampling paths. The encoder (left) uses successive convolutional layers and pooling to capture context at multiple scales, progressively reducing the spatial resolution while increasing feature channels. The decoder (right) performs upsampling (e.g., via a transposed convolution) and convolution, gradually restoring the resolution and reducing the channel depth. Crucially, skip connections (horizontal gray arrows in the figure) copy feature maps from the encoder to the decoder at the corresponding levels, combining coarse high-level features with fine-grained low-level features (Ronneberger et al., 2015).

The use of skip connections within U-Net ensures the preservation of fine-grained spatial details, which is critical for the identification of pathologies such as ground–glass opacities and pulmonary consolidations. The output of the U-Net segmentation is used to create a mask that is applied to the CT image, effectively removing non-lung regions. This step reduces noise and ensures that the subsequent feature extraction is focused solely on the regions of diagnostic relevance. As a result, the model becomes more robust to irrelevant variations and background interference. In the final layer, a 1 × 1 convolution reduces the feature maps to a single channel representing the lung class. A sigmoid activation function is applied to generate a pixel-wise probability map:

where aij is the raw output (logit) for pixel (i, j), and ŷij is the predicted probability that the pixel belongs to the lung region.

To train the model, two commonly used loss functions are

the binary cross-entropy (BCE) loss

which penalizes the discrepancy between predicted probabilities and the corresponding ground-truth labels across all N pixels (or voxels). Complementing this, is the Dice loss, which measures the overlap between predictions and ground truth, and is given by

where ε = 10−6 is a small constant, to avoid division by zero. All symbols are defined in Table 1. The two losses are combined during training and are especially effective for medical image segmentation tasks with class imbalance.

U-Net is widely used for lung segmentation due to its ability to produce accurate, edge-preserving segmentations with limited training data (Ronneberger et al., 2015). Its skip connections combine semantic and spatial features, making it ideal for segmenting complex anatomical structures such as the lungs. U-Net models have demonstrated Dice similarity coefficients above 0.95 in lung CT applications. Additionally, its fully convolutional design enables fast inference, making it suitable for clinical deployment.

3.1.2 Deep feature extraction with adaptive modules

In this stage, a ResNet-50 convolutional neural network pretrained on ImageNet is fine-tuned on COVID-19 CT scans to learn robust feature representations of lung tissue. Using pretrained weights provides a strong initialization, and fine-tuning adapts the model to medical imaging characteristics (e.g., subtle textures of ground–glass opacities). The network thus learns a hierarchy of features (from low-level edges to high-level lung patterns) tailored to COVID-19 manifestations. To further improve feature extraction, we integrate two adaptive modules into the ResNet-50 backbone: an adaptive deformable module (ADM) and an attention-based encoder. These modules enable the model to handle the irregular shape of infection areas and focus on critical regions, respectively, yielding more discriminative features for COVID-19 detection.

3.1.2.1 Adaptive deformable module (ADM)

The ADM enhances the CNN's ability to capture lesions of varying shapes and locations by using deformable convolutional layers. It is inserted after the third residual block of ResNet-50, modifying standard 3 × 3 convolutions into deformable convolutions with learned offsets Δpn and modulation scalars Δmnε [0,1]. During training, the offset learning layer generates 18 offset values and 9 modulation scalars per feature map location. This allows the receptive field to shift dynamically in response to spatial structures. The deformable convolution at output location p0 is defined as

where is the regular sampling grid (e.g., 3 × 3), (pn) are the filter weights, and x(·) represents the input feature map. The feature maps at this stage have a spatial resolution of 28 × 28 × 512, and the ADM adjusts these maps to better align with irregular lesion boundaries, which often include elongated or peripheral GGOs. The offsets Δpn and modulation values Δmn? are predicted by auxiliary convolutional layers during training, allowing the network to learn how to “bend” the convolutional receptive field to better cover irregular lesions. Intuitively, the ADM lets the model stretch or shrink its sampling region to fit the shape of abnormalities, for example, wrapping around an elongated opacity or hitting a small consolidation precisely. Such dynamic adaptation ensures that spatially irregular COVID-19 lesions (which vary greatly in shape and size) are captured more effectively than with rigid kernels. By modeling anatomic deformations, the ADM produces feature maps that preserve fine-grained lesion details, improving the network's robustness in recognizing COVID-19 patterns even if they appear in atypical forms or locations.

3.1.2.2 Attention-based encoder

Next, the feature map is passed through an attention-based encoder that highlights salient regions in the lungs, such as bilateral GGOs, subpleural consolidations, or vascular enlargement, while suppressing background noise. This encoder learns to assign higher weights to image regions that are likely indicative of COVID-19, effectively focusing the model's “attention” on the most informative parts of the CT scan. A channel-spatial attention block is applied to each feature tensor, generating a spatial weight (p) for each position p, where (p)εR28×28. A simplified formulation of attention weights is

where s(p) is a learned scoring function (such as a 1 × 1 convolution or a dense layer applied to the features) that gauges the importance of location p. The normalized attention weights (p) emphasize regions with high scores. These coefficients then modulate the feature map, for instance, by being involved in the computation of a weighted aggregation of features

where f(p) is the feature vector at position pεRC with C = 2,048, and z is the resulting attention-enhanced representation. Through this process, features from critical regions (such as infected lung areas) are amplified, while contributions from less relevant regions are diminished. The attention-based encoder effectively acts as a learned spotlight, guiding the model to concentrate on key pathological patterns such as the hazy appearance of ground-glass opacities or dense consolidations that signal COVID-19 pneumonia. This produces a refined, high-level feature representation of the CT scan that adapts to irregular lesion geometry and highlights key infection areas, forming a solid foundation for subsequent classification.

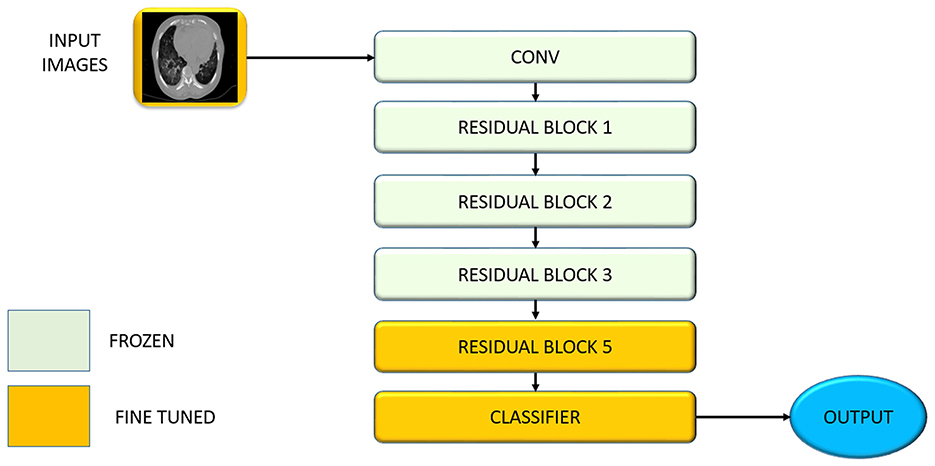

3.1.3 Transfer learning for efficient adaptation

This stage performs transfer learning by adapting a ResNet-50 model pretrained on ImageNet for COVID-19 detection using chest CT scans. Transfer learning is particularly effective in medical imaging, where annotated data is limited (Alzubaidi et al., 2021a). In our case, only 3,200 labeled CT scans are available, while the pretrained ResNet-50 model has learned from over 1 million natural images. This allows the model to reuse low-level visual features such as edges and textures, accelerating convergence and reducing overfitting.

To preserve general visual features, the first four residual blocks of ResNet-50—accounting for approximately 36.2 million parameters—are frozen (θf). The final residual block and classification head—approximately 9.1 million parameters—are fine-tuned (θt) to specialize in detecting high-level COVID-19-specific markers, such as bilateral GGOs and subpleural consolidations. The parameter set is partitioned as θ = {θf, θt}. Fine-tuning is conducted with a learning rate of 1 × 10−4 using the Adam optimizer, minimizing the cross-entropy classification loss

where yi is the ground truth, and ŷi is the predicted probability. Only θt is updated:

This fine-tuning procedure updates only a subset of weights via backpropagation and reduces the risk of overfitting on small datasets while enabling high-level adaptation to domain-specific features. This enables efficient adaptation to the COVID-19 detection task even with limited data. Figure 3 illustrates the layer-wise partitioning of the ResNet-50 backbone, showing which blocks are frozen and which are fine-tuned during transfer learning. The early layers, responsible for generic feature extraction, remain fixed, while the final block and classifier are updated to specialize in COVID-19-specific features.

Figure 3 below illustrates the architecture-level partitioning of the ResNet-50 backbone in the proposed framework. This figure shows the demarcation between the frozen layers (used for general feature extraction) and the fine-tuned layers (adapted to COVID-19-specific markers), highlighting the selective updating of parameters during transfer learning.

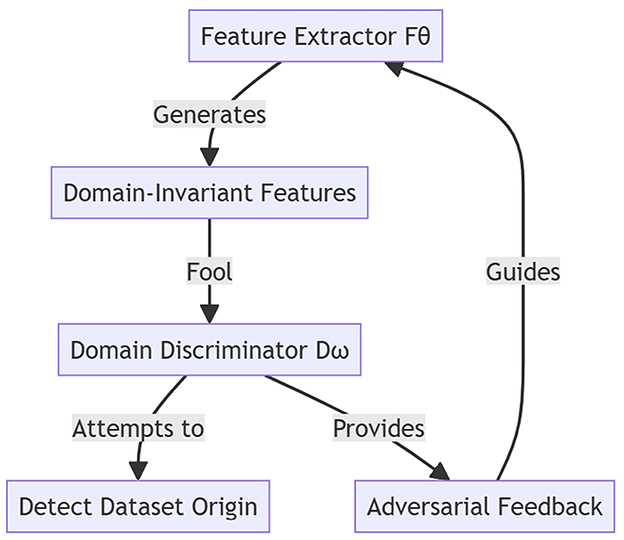

3.1.4 Domain-adversarial feature alignment

To mitigate domain shifts caused by differences in scanner types, imaging protocols, and patient demographics across datasets, we use domain-adversarial training to align feature representations. The Kaggle COVID-19 dataset serves as the source domain, providing labeled data for supervised training. The target domains include those of COVID-CT-MD, BIMCV COVID-19+, and MosMedData datasets, which present diverse and heterogeneous imaging distributions. These domain discrepancies can hinder generalization, prompting the need to learn representations that remain discriminative for COVID-19 but invariant across domains.

This stage introduces a domain discriminator Dω, trained to distinguish the domain origin (e.g., Kaggle, BIMCV, or MosMedData) of a feature vector, while the feature extractor Fθ learns to generate domain-invariant features. A gradient reversal layer (GRL) is placed between Fθ and Dω. During forward propagation, the GRL acts as the identity function, but in backpropagation, it multiplies the gradient by −1, forcing Fθ to maximize the domain classification loss, and effectively “fooling” Dω. The joint objective is defined as , where is the cross-entropy classification loss for COVID-19 diagnosis, and is a binary or multiclass cross-entropy loss, depending on the number of domains. We set λ = 0.3, selected by grid search to maximize cross-domain F1 (see Supplementary Table 7). In our implementation, the domain discriminator Dω is a two-layer multilayer perceptron (MLP) with 128 hidden units and ReLU activations. Each sample is labeled according to its dataset origin (e.g., Kaggle = 0, BIMCV = 1, etc.), and the model learns from the source domain (Kaggle) and the target domain (COVID-CT-MD, BIMCV, or MosMedData) simultaneously. This adversarial training strategy ensures that the learned features retain COVID-19 discriminative power while minimizing dataset-specific biases. As a result, the framework becomes robust to unseen domains, enabling effective and explainable COVID-19 detection across clinical settings. Figure 4 illustrates the domain-adversarial feature alignment process across the source and target datasets.

The Kaggle COVID-19 dataset serves as the source domain, while COVID-CT-MD, BIMCV COVID-19+, and MosMedData act as target domains. A gradient reversal layer enables the feature extractor to learn domain-invariant representations by reversing gradients from the domain discriminator. This process improves cross-dataset generalization while preserving COVID-19-specific features.

3.1.5 Deep Learning classification layer

In this final stage, the deep learning classification layer produces the ultimate diagnosis by processing the consolidated features through a fully connected neural network classifier. The feature vector z ε Rd (with d = 512 in our architecture) from the previous stage is passed into a dense output layer consisting of C = 3 neurons, one per target class (COVID-19, pneumonia, or normal). Each neuron is associated with a learned weight matrix and a bias vector, W ε RC × d and b ε RC, respectively.

The logits (unnormalized scores) are given by

Applying the softmax activation function converts these logits into a normalized probability distribution over the classes:

Here y′ ε RC with , and each component represents the model's confidence (the probability) that the input CT scan belongs to class i. For example, an output y′ = [0.80, 0.15, 0.05] would indicate an 80% probability of COVID-19, 15% chance of pneumonia, and 5% chance of being normal, with the highest probability class (COVID-19 in this case) chosen as the prediction. During training, the classifier parameters W and b are optimized (e.g., via gradient descent with a learning rate on the order of 10−4) using a multiclass cross-entropy loss so that the softmax outputs y′ closely match the true labels for each of the three conditions.

3.1.6 Feature discretization for symbolic mapping

To support symbolic reasoning, numerical CNN activations are mapped into discrete, binary indicators Ik using clinically inspired thresholds τk. For example, indicators of the form

may represent features such as “GGO detected,” “bilateral opacities present,” or “vascular enlargement seen,” which are consistent with radiological descriptors in COVID-19 diagnosis.

3.1.7 Symbolic reasoning via rule-based inference

The symbolic component includes a clinical knowledge base and an inference engine. Rules are crafted from authoritative guidelines (e.g., of the WHO or RSNA) and expert consensus. An example rule is

IF (IGGO = 1) ∧ (IBilat = 1) ∧ (IEffusion = 0) ⇒ Diagnosis = Likely COVID-19

Such rules are validated through expert review and capture structured, human-readable diagnostic logic.

3.1.8 Hybrid decision fusion with confidence mediation

To combine data-driven learning and expert reasoning, we apply a weighted fusion mechanism Dfinal = αŷi +(1−α)ŷsymb where yi is the CNN prediction, ysymb is the symbolic inference result, and α is a tuneable parameter that can be dynamically adjusted based on model uncertainty or symbolic rule confidence.

3.1.9 Final output and explainability report

The final output includes the predicted class label with its associated probability, the activated symbolic rules that contributed to the decision, and plain-text justifications such as “COVID-19 likely due to bilateral GGO, no effusion, peripheral involvement.”

3.1.10 Statistical validation framework

To ensure the robustness of the reported results, we applied statistical tests appropriate to the nature of each analysis. Specifically,

(i) Parametric comparisons (e.g., model accuracy and F1 scores across folds) were evaluated using paired t tests, assuming the normality of distribution,

(ii) Nonparametric metrics (e.g., the cost per scan and interpretability ratings) were assessed using the Wilcoxon's signed-rank test,

(iii) To control for false discovery in multiple hypothesis testing, the Benjamini–Hochberg correction was applied, and

(iv) All statistical analyses were performed using SciPy v1.11.0, with the significance threshold set at α = 0.05.

These rigorous statistical methods ensure reliable validation of model performance while controlling for multiple comparisons, following established practices for medical AI evaluation (Aznar-Gimeno et al., 2022; Vrudhula et al., 2024).

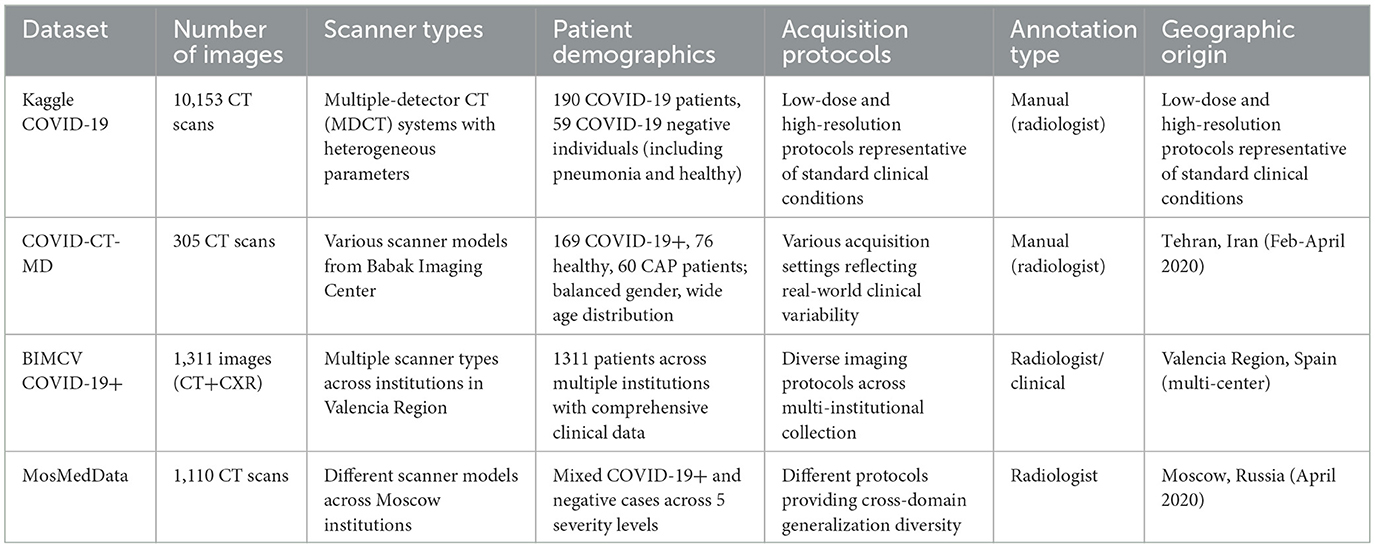

3.2 Database

We conducted our experiments using four publicly accessible, heterogeneous chest CT datasets: Kaggle COVID-19, COVID-CT-MD, BIMCV COVID-19+, and MosMedData. Each dataset was selected to capture a broad range of institutional practices, imaging protocols, modalities, and population demographics, thereby supporting a comprehensive evaluation of cross-domain model robustness and real-world clinical applicability.

Detailed Dataset Specifications:

The Kaggle COVID-19 dataset's scan images were collected from the radiology centers of teaching hospitals in Tehran, Iran, and included 7,644 CT scans of 190 COVID-19 patients and 2,509 CT scans of 59 COVID-19-negative individuals (including pneumonia patients and healthy subjects). The images were acquired using multiple-detector computed tomography (MDCT) systems with heterogeneous acquisition parameters, encompassing both low-dose and high-resolution protocols representative of standard clinical conditions.

The COVID-CT-MD dataset contains CT scans of 305 patients across three diagnostic categories: 169 confirmed COVID-19 cases, 76 healthy individuals, and 60 community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) patients. This dataset, collected from the Babak Imaging Center, Tehran, Iran in February–April 2020, features a balanced gender representation and a wide age distribution, with images acquired using various scanner models and acquisition settings to reflect real-world clinical variability.

The BIMCV COVID-19+ dataset is a multicentre dataset of imaging data from 1,311 patients across multiple institutions in the Valencia Region, Spain. This dataset includes both chest X-ray and CT modalities, accompanied by comprehensive clinical annotations, radiographic findings, pathological data, and diagnostic test results. The multi-institutional collection ensures the representation of diverse scanner types, imaging protocols, and demographic characteristics.

The MosMedData dataset consists of 1,110 anonymized lung CT scans collected from various medical institutions in Moscow, Russia in April 2020, categorized into five severity levels based on the extent of lung involvement. The dataset encompasses both COVID-19-positive cases and those with negative findings, and its images were acquired using different scanner models and protocols, providing valuable diversity for cross-domain generalization assessment.

The four datasets employed in this study represent diverse healthcare environments and imaging protocols across multiple countries. The comprehensive characteristics of these datasets are summarized in Table 2.

Acquisition parameters across datasets varied (e.g., slice thickness 1–5 mm, reconstruction kernels ranging from soft to sharp, and fields of view between 250 and 400 mm), further underscoring the need for input standardization.

The inclusion of multiple, independently sourced datasets ensures diversity in scanner hardware, acquisition protocols, disease prevalence, patient demographics, and labeling methodologies. This heterogeneity is essential for developing and validating models intended for real-world clinical deployment rather than single-cohort optimization. By evaluating our hybrid framework across datasets from distinct geographic regions (Iran, Spain, and Russia) and healthcare systems, we can objectively assess generalization capabilities across the domain shifts commonly encountered in clinical practice. This multi-domain approach provides a rigorous benchmarking foundation and ensures practical relevance for scalable AI-driven COVID-19 detection systems.

3.3 Preprocessing and standardization

To ensure robust cross-dataset generalizability and systematically address a significant heterogeneity in imaging acquisition protocols, scanner characteristics, and label structures across the datasets described in Section 3.2, we implemented a comprehensive preprocessing pipeline designed to standardize inputs while preserving diagnostically relevant features.

3.3.1 Image resampling and spatial normalization

All the CT scans underwent uniform spatial resampling to achieve consistent voxel spacing and slice thickness across datasets. Images were resampled to the isotropic 1 mm3 voxel resolution using trilinear interpolation, effectively eliminating scanner-specific spatial discrepancies that could confound model training. This standardization ensured that anatomic structures maintained consistent spatial relationships regardless of the original acquisition parameters.

3.3.2 Intensity normalization and standardization

Hounsfield unit (HU) values were normalized per scan using the z-score standardization: HU_normalized = (HU – μ_scan) / σ_scan, where μ_scan and σ_scan represent the mean and standard deviation of intensity values within each individual scan, respectively. Compared with global min-max scaling, this approach demonstrated superior robustness to institutional calibration variations and biological tissue density differences, ensuring consistent intensity distributions across diverse scanner types and acquisition protocols.

3.3.3 Anatomic region segmentation

A pretrained U-Net segmentation model was used to automatically isolate and extract the lung parenchyma from each CT scan, effectively masking extraneous anatomic structures and standardizing the anatomic region of interest. This preprocessing step ensured that subsequent analysis focused exclusively on the lung tissue, eliminating potential confounders from cardiac structures, the chest wall, and mediastinal contents that varied significantly across datasets and imaging protocols.

3.3.4 Spatial cropping and resizing

Following lung segmentation, tight bounding boxes were computed from the generated lung masks, and images were uniformly cropped and resized to 224 × 224 pixels. This standardization ensured spatial consistency for deep learning input while maintaining aspect ratios and anatomic proportions. The fixed input dimensions eliminated variability in the field-of-view and original scan dimensions across different institutions and scanner configurations.

3.3.5 Data augmentation strategy

To mitigate dataset-specific biases and enhance model generalizability, systematic data augmentation was performed during training:

i. Geometric augmentation: Random horizontal/vertical flips, rotations (±15 °), and scaling transformations (±10%).

ii. Intensity augmentation: Gaussian noise injection (σ = 0.05) and intensity jittering (±5% of the dynamic range).

iii. Elastic deformations: Subtle elastic transformations to simulate natural anatomic variations.

Augmentation parameters were empirically optimized through cross-validation to maximize F1-score convergence while preventing overfitting to individual dataset characteristics.

3.3.6 Label harmonization and standardization

Diagnostic classifications were standardized to three consistent labels across all datasets: COVID-19, pneumonia (non-COVID), and normal. For datasets with multilevel severity classifications (e.g., MosMedData's five-level system), appropriate mapping functions were implemented to ensure a uniform label structure. This harmonization enabled consistent model training and evaluation across heterogeneous annotation schemes.

3.3.7 Preprocessing parameter selection and validation

The critical preprocessing parameters were systematically optimized through empirical evaluation to ensure robust cross-domain performance. Each parameter was selected based on extensive grid search optimization and validated using domain-specific metrics that reflect the preprocessing component's contribution to overall system performance.

For example, isotropic resampling resolutions from 0.5 to 2.0 mm3 were evaluated, with 1.0 mm3 selected as it preserved anatomic fidelity while minimizing computational overhead (see Supplementary Table 1). The optimized preprocessing parameters, including their selected values, optimization ranges, and the validation metrics used to guide parameter selection, are provided (see Supplementary Table 1).

3.3.8 Cross-dataset input standardization

The integrated preprocessing pipeline achieves comprehensive input standardization through the following:

i. Spatial harmonization: Uniform voxel spacing and image dimensions across all datasets.

ii. Intensity standardization: Consistent HU value distributions independent of scanner calibration.

iii Anatomic consistency: Standardized lung region extraction, eliminating extraneous anatomy.

iv. Label uniformity: Consistent diagnostic classification scheme across heterogeneous annotation systems.

v. Augmentation consistency: Identical data augmentation strategies applied uniformly across all datasets.

This systematic approach ensures that, despite substantial institutional differences in imaging protocols, scanner characteristics, patient demographics, and annotation practices, all images entering the hybrid AI model are comparable in terms of format, intensity distribution, spatial resolution, and anatomic content. The standardization methodology directly addresses input heterogeneity challenges while preserving diagnostically relevant pathologic features essential for accurate COVID-19 detection.

3.3.9 Validation of standardization effectiveness

The preprocessing pipeline's effectiveness was quantitatively validated through histogram overlap analysis, domain adaptation loss minimization, and cross-dataset performance consistency metrics. Statistical significance testing confirmed that standardized inputs significantly reduced inter-dataset distributional differences (p < 0.001, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test) while preserving diagnostic features (as confirmed through a radiologist's review of processed images). In addition, a senior radiologist independently reviewed a random subset of 200 standardized scans and confirmed that diagnostically relevant pulmonary features were preserved without visible artifacts.

3.4 Experimental setup and evaluation metrics

This section details the experimental protocols and evaluation metrics used to validate the performance of the proposed hybrid AI framework.

3.4.1 Implementation details

All the experiments were performed on four NVIDIA A100 GPUs with 40 GB of VRAM in each. Model training was implemented in PyTorch v2.1.1, leveraging automatic mixed-precision (AMP) for computational efficiency. Optimization was performed using the AdamW algorithm with hyperparameters β1 = 0.9 and β2 = 0.999. The initial learning rate was set to 1 × 104 and decayed using a cosine annealing schedule. To accommodate hardware memory limits, a batch size of 32 was used for CT scans. Early stopping was applied with the patience of 10 epochs, and the validation loss was monitored to prevent overfitting.

The implementation choices—including the use of the AdamW optimizer (Loshchilov and Hutter, 2019), cosine annealing learning rate schedule (Loshchilov and Hutter, 2017), and early stopping—follow established best practices for efficient deep learning model development in medical imaging applications (Alzubaidi et al., 2021b). These methods have been shown to improve stability, convergence and generalization performance in clinical imaging applications.

3.4.2 Datasets

The model was evaluated on multiple publicly available chest CT scan datasets, which were preprocessed and segmented as described in Section 3.1.1. The datasets varied in size, source domain, scanner settings, and patient demographics, enabling an assessment of the model's ability to generalize across domains.

3.4.3 Training protocol

To ensure a rigorous validation, we adopted a five-fold cross-validation strategy. Each dataset was randomly partitioned into five subsets. In each fold, four subsets were used for training, and one was used for testing; the latter role was rotated across folds to obtain robust performance estimates. This approach mitigated the influence of data partition bias and enhanced statistical reliability.

Recent studies in multi-center COVID-19 CT classification highlight the importance of five-fold cross-validation for reducing sampling bias and ensuring generalizable model performance across heterogeneous imaging cohorts (Turnbull and Mutch, 2024b; Bougourzi et al., 2024). Our protocol aligns with these recommended validation standards.

3.4.4 Evaluation metrics

The performance of the hybrid model was assessed using standard evaluation metrics widely adopted in medical imaging and clinical AI research. Accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score are well-established indicators for classification tasks, especially in healthcare settings where class imbalance is common (Bani Baker et al., 2024).

Accuracy measures the overall classification correctness:

Precision is the proportion of correctly predicted positive cases among all predicted positives:

Recall (Sensitivity) is the proportion of actual positives correctly predicted:

F1 score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall:

The AUC-ROC metric quantifies a model's discriminative ability across all classification thresholds, making it a widely adopted and robust standard for evaluating the overall ranking performance of binary and multiclass medical diagnostic systems, particularly in situations with balanced class distributions or where the cost of false positives and false negatives is considered equal (Park et al., 2023).

To evaluate cross-domain robustness, we compute a Domain Adaptation Score (DAS), following established evaluation protocols in adversarial adaptation studies (Singhal et al., 2023).

The Explainability Score, which measures alignment between symbolic rules and radiologist-verified findings, is grounded in recent advances in interpretable neuro-symbolic AI frameworks (Confalonieri and Guizzardi, 2025; Fouad et al., 2025). These metrics collectively ensure that the evaluation captures accuracy, robustness, interpretability and clinical validity, consistent with best practices for AI-driven medical diagnostic systems.

3.4.5 Clinical validation protocol

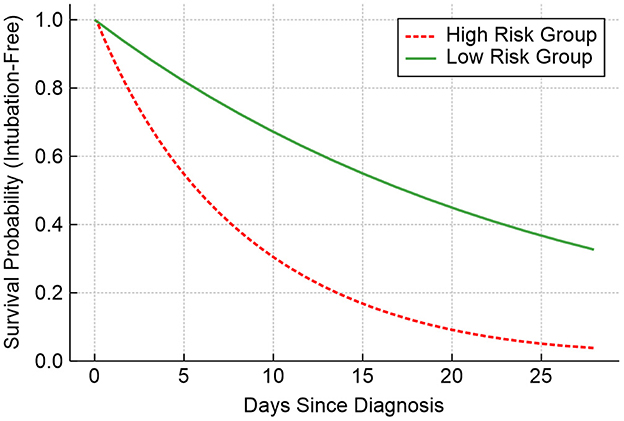

We engaged eight board-certified thoracic radiologists (with the mean experience of 12.7 ± 4.2 years) from three medical centers for a blind evaluation. Each expert independently reviewed 300 randomly selected CT studies (100 of COVID-19 cases, 100 pneumonia cases, and 100 normal cases) through the RadBench platform v3.1.5, which concealed model predictions during the initial assessment. Diagnostic concordance was measured using Light's multi-rater κ coefficient with 95% confidence intervals calculated via bootstrap resampling (1,000 iterations). The treatment outcome analysis incorporated electronic health record (EHR) data from 1,472 patients, capturing clinically significant endpoints such as ICU admission within 14 days (corresponding to a WHO Clinical Progression Scale score of 6 or above), a 40% reduction in C-reactive protein (CRP) levels following steroid therapy measured 72 h post-administration, and intubation-free survival, with outcomes censored at 28 days.

The use of κ-statistics, blind multi-reader evaluation, and bootstrapped confidence intervals follows established clinical AI validation guidelines (Aznar-Gimeno et al., 2022). This ensures that diagnostic performance is rigorously assessed under conditions comparable to real-world radiological workflows.

3.5 Hyperparameter selection and optimization

Hyperparameters were determined through systematic grid search and empirical evaluation rather than arbitrary selection. The search was applied consistently across all four datasets, and the chosen values proved stable without dataset-specific tuning. This ensured that the reported results reflect parameters robust to cross-dataset variability rather than overfitting to a single source.

To ensure optimal model performance and reproducibility, all key hyperparameters of the experimental classifiers and segmentation algorithms are summarized in Supplementary Table 2, along with their final values, the search space or the literature defaults explored, and the supporting references. Hyperparameter tuning was guided by a combination of prior literature on similar medical imaging tasks, an empirical grid search, and five-fold cross-validation on the training set. For parameters with no widely accepted optimal values in the literature, a range of candidate values was evaluated, and the final values were selected based on validation accuracy, loss convergence, and model stability. These settings reflected both empirical optimization and the established best practices from recent medical imaging studies.

To ensure optimal performance, hyperparameters were tuned based on empirical evaluation and supported by prior literature. For instance, the Adam optimizer was selected due to its proven stability and widespread application in deep learning for medical imaging tasks (Kingma and Ba, 2015). The attention encoder configuration, particularly the number of heads and the dropout rate, follows the established design principles of transformer-based models (Vaswani et al., 2017). For the domain-adversarial component, the gradient reversal strategy and the trade-off coefficient were adopted from the established practices in the domain adaptation literature (Ganin et al., 2016).

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Cross-dataset performance with an enhanced AUC-ROC analysis

A prior study reported an in-domain accuracy of 99.16% for a model trained and evaluated on a single-source dataset. While this result was notable, it did not account for variations in imaging protocol or population diversity. In contrast, the present study yielded a slightly lower accuracy of 97.7%, reflecting the increased challenge of generalizing across multiple real-world datasets. This modest reduction is a direct consequence of the more challenging evaluation setting but represents a valuable trade-off for greater robustness and clinical applicability. These training and validation behaviors are consistent with expected convergence patterns reported in recent transformer-based and CNN-based COVID-19 diagnostic models (Gawande et al., 2025; Amuda et al., 2025).

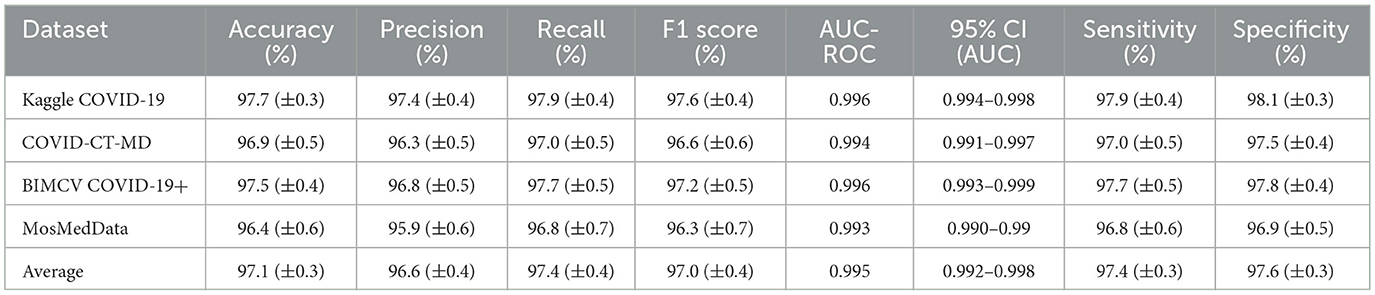

We evaluated the hybrid model across four independent datasets—Kaggle COVID-19, COVID-CT-MD, BIMCV COVID-19+, and MosMedData—to provide a comprehensive performance analysis including a detailed AUC–ROC evaluation and an assessment of training dynamics. An analysis of cross-dataset performance with AUC-ROC is presented in Table 3.

The AUC–ROC values demonstrate statistically significant performance across all datasets (p < 0.001, DeLong's test), with 95% confidence intervals consistently exceeding 0.990. The cross-dataset AUC-ROC variance (σ2 = 0.0000015) indicates exceptional stability and generalizability.

These results show that although accuracy varies slightly among datasets due to differences in imaging characteristics and annotation quality, the model maintains high performance across domains. This demonstrates effective cross-dataset generalization, which was not evaluated in our earlier research.

4.1.1 Training performance and overfitting assessment

The hybrid AI model was trained for 50 epochs with early stopping (patience = 7) to prevent overfitting. Comprehensive training curves were monitored across all performance metrics to ensure robust generalization. The training progression demonstrated stable convergence with minimal overfitting, as evidenced by the close alignment between the training and validation performance metrics throughout the learning process.

4.1.1.1 Training convergence analysis

i. Training Accuracy: Converged from the initial 85.9% to the final 97.1% over 50 epochs.

ii. Validation Accuracy: Progressed from 82.9% to 97.2%, maintaining close parity with training accuracy.

iii. Training Loss: Decreased exponentially from 0.476 to 0.022, indicating effective learning.

iv. Validation Loss: Declined from 0.523 to 0.026 with a minimal divergence from the training loss.

v Training AUC-ROC: Achieved a rapid convergence to 0.999 by epoch 15, as AUC-ROC reached 0.997 with a smooth progression, closely tracking the training performance.

4.1.1.2 Overfitting assessment

The model demonstrated excellent generalization characteristics with minimal overfitting indicators:

i. Accuracy Gap (Training-Validation): −0.001 (the validation value being slightly higher, indicating robust generalization)

ii. AUC-ROC Gap (Training-Validation): +0.002 (a minimal difference well within an acceptable range)

iii. Loss Gap (Validation-Training): +0.004 (a small validation loss penalty, indicating controlled overfitting)

These metrics confirm that the regularization strategies (dropout = 0.5, weight decay = 1e-4, and early stopping) effectively prevented overfitting while maintaining high performance. Supplementary Table 3 provides a comprehensive comparison of training vs. validation performance across all evaluation metrics, demonstrating the effectiveness of our regularization strategies.

4.1.2 Statistical significance and training stability

4.1.2.1 Statistical significance of AUC-ROC performance

The AUC–ROC values demonstrate statistically significant performance across all datasets (p < 0.001, DeLong's test), with 95% confidence intervals consistently exceeding 0.990. The cross-dataset AUC-ROC variance (σ2 = 0.0000015) indicates exceptional stability and generalizability. The minimum AUC-ROC value of 0.993 (observed for MosMedData) still represents excellent discrimination ability that is well above the clinical acceptance threshold of 0.90. Supplementary Table 4 presents the class-wise AUC-ROC performance across all four datasets, with macro-averaged AUC scores ranging from 0.993 to 0.996.

4.1.2.2 Training stability and convergence analysis

i. Learning Rate Optimization: The cosine annealing scheduler with the initial learning rate of 1e-4 facilitated a smooth convergence without oscillations. Training was stable throughout all 50 epochs, with validation metrics consistently tracking training performance.

ii. Early Stopping Effectiveness: Although early stopping was configured with patience = 7, the model demonstrated continued improvement through epoch 50, indicating the optimal training duration. No overfitting was observed even during the extended training, validating our regularization strategy.

iii. Cross-Validation Stability: Five-fold cross-validation revealed minimal performance variance (the standard deviation of AUC-ROC being 0.0007), confirming model robustness across different data splits and supporting the reliability of the reported performance metrics.

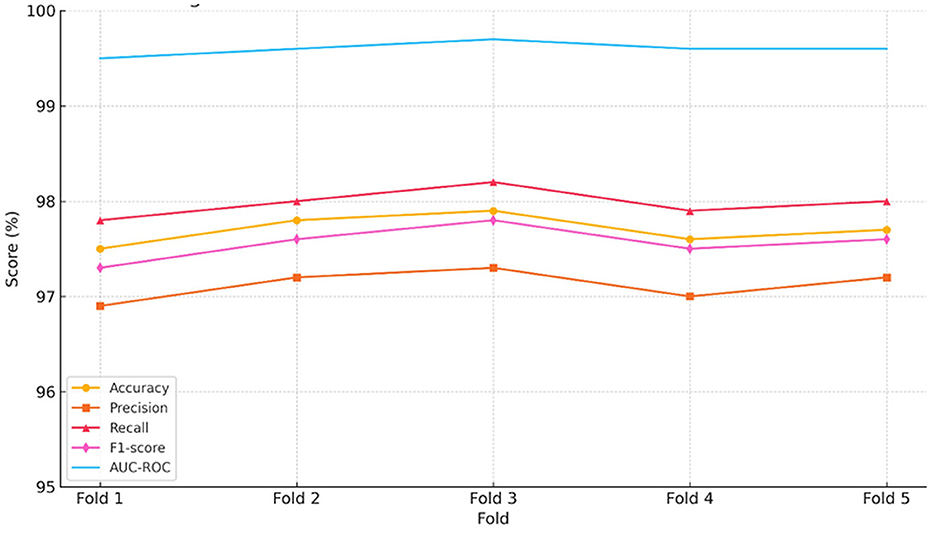

To further validate model consistency and robustness, we conducted a comprehensive cross-validation analysis across stratified multi-domain data splits.

4.2 Cross-validation performance across folds

To evaluate consistency under varied data splits, we performed five-fold cross-validation using a pooled multi-domain dataset. The results are summarized in Supplementary Table 5. These results indicate consistently high performance across all folds, with minimal variance. This uniformity reinforces the reliability and robustness of the hybrid model trained and validated across stratified samples drawn from a heterogeneous multi-domain dataset.

4.3 Model interpretability and visualization analysis

To address interpretability requirements and validate the learned features, we performed a gradient-weighted class activation mapping (GradCAM) analysis. GradCAM generates visual explanations by highlighting discriminative regions contributing to COVID-19 classification decisions, using gradients flowing into the final convolutional layer. Grad-CAM is recognized as a robust and widely used interpretability tool for clinical CNN validation, enabling the visualization of spatial attention patterns consistent with radiological findings (Rana et al., 2022; Fouad et al., 2025). Its adoption in this study ensures that model attention aligns with clinically meaningful lung regions such as GGOs, consolidations and vascular abnormalities.

4.3.1 Implementation and validation

GradCAM Generation: This process is applied to the final convolutional layer of ResNet-50 (layer 4 [−1]) to produce class-specific activation maps for COVID-19, pneumonia, and normal cases. This technique computes pixel-wise importance weights defined as

Where represents gradient-derived importance weights.

Quantitative Validation: GradCAM reliability was validated against radiologist-annotated regions across all datasets. Supplementary Table 6 presents the localization accuracy, Intersection over Union (IoU), and clinical concordance for each dataset as well as the average performance. Three board-certified radiologists validated the GradCAM outputs, achieving a 92.7% diagnostic relevance agreement and the Cohen's kappa of 0.87 (95% CI: 0.83–0.91).

4.3.2 Feature learning validation

For each diagnostic class (COVID-19, pneumonia, normal), we generated separate activation maps to validate class-specific feature learning:

i. COVID-19 patterns: GradCAM consistently highlighted peripheral ground-glass opacities and bilateral involvement.

ii. Pneumonia patterns: Observations were focused on consolidated regions with focal distributions.

iii. Normal cases: Minimal parenchymal activation was observed, and anatomic boundaries were emphasized.

iv. Domain Adaptation Impact: The cross-dataset IoU variance decreased from 0.0189 to 0.0094 (−50.3%) after domain adaptation, with the activation pattern similarity improving from 67.3% to 84.7%, confirming the role of domain-invariant feature learning rather than dataset-specific artifacts.

Hence, our hybrid model learns clinically meaningful, discriminative features aligned with radiological expertise, validating the interpretability and diagnostic validity of the proposed model.

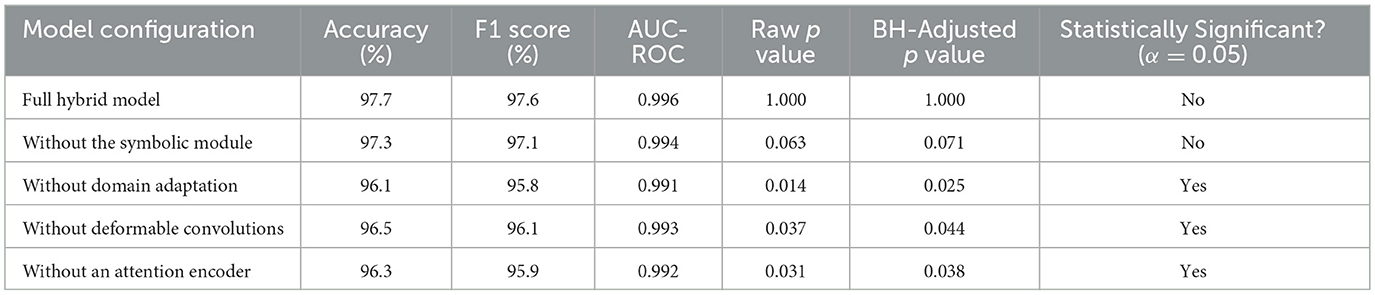

4.4 Ablation study and hyperparameter sensitivity

To further validate the robustness of the proposed domain-adapted hybrid AI framework and maintain continuity with prior research (Musanga et al., 2025), we conducted an extensive series of ablation experiments and hyperparameter sensitivity analyses. Our goal was to quantify the individual contributions of architectural modules and to systematically assess how key hyperparameter settings influenced generalization across heterogeneous COVID-19 CT datasets.

4.4.1 Component ablation analysis

We first evaluated the impact of disabling individual model components—namely, the adaptive deformable module (ADM), the attention-based encoder (ABE), domain-adversarial training (DAT), and the symbolic AI processing unit (SAPU)—on the overall diagnostic performance. As shown in Table 4, each component was omitted from the complete hybrid framework in turn, and results were compared in terms of mean accuracy, the F1 score, and AUC-ROC, with significance tested via paired t tests and the Benjamini–Hochberg correction.

The removal of domain adaptation resulted in the largest statistically significant drop in performance (accuracy: 96.1%, F1 score: 95.8%, AUC: 0.991), emphasizing domain adaptation's critical role in handling inter-dataset variability. Significant declines in accuracy and the F1 score were also observed upon removing the attention encoder and deformable convolution modules, which reflected their complementary contributions to spatial focus and flexible feature extraction. Omission of the symbolic module led to only a modest, statistically insignificant, decrease, confirming that this module's primary benefit entailed model explainability rather than absolute classification accuracy; this finding was consistent with prior research.

4.4.2 Hyperparameter sensitivity

To complement architectural ablation, we systematically varied key hyperparameters to assess their influence on model robustness and cross-domain performance. For each main training or module-specific parameter (e.g., the learning rate, the batch size, the loss function, the domain-adversarial coefficient, dropout rates, the number of attention heads, deformable module's sampling points, and symbolic rule thresholds), we measured the change in the mean F1 score and AUC-ROC across all four evaluation datasets, holding all other factors constant.

Supplementary Table 7 summarizes the effect of each adjustment or ablation relative to the baseline (full) model. The results show, for example, that increasing the classifier learning rate to 1e-3 reduced the mean F1 by 2.1 percentage points (“pp”), and switching the segmentation loss from Dice to cross-entropy resulted in a 1.9% decrement. Higher domain-adversarial coefficients (λ > 0.3), reductions in the number of attention heads, or using fewer deformable sampling points similarly led to degraded generalizability. These analyses justified the specific hyperparameter choices reported in Section 3.5, as our grid search and ablation approach consistently optimized both stability and cross-domain performance. These quantitative results validated not only the significance of each principal module but also the critical importance of rigorous hyperparameter optimization. The observed performance impacts are directly referenced in the justification column of our unified hyperparameter table (see Supplementary Table 2).

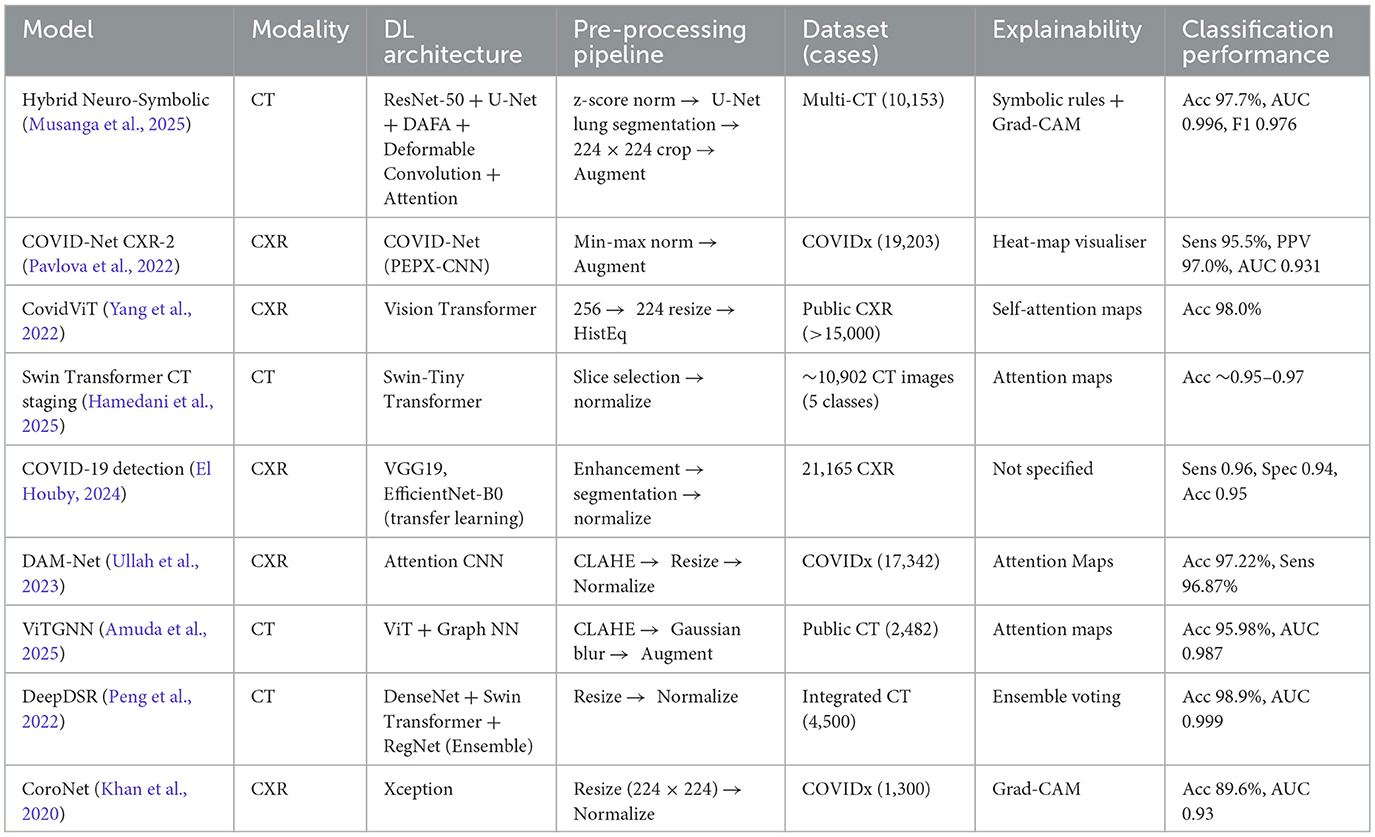

4.5 Comparative evaluation with existing models

To contextualize our results within the broader landscape of COVID-19 detection using AI, we compared our hybrid framework to other notable deep learning models reported in the literature and models from prior studies. While baseline CNNs such as ResNet-50 and DenseNet-121 demonstrate high accuracy under controlled conditions, their performance declines in cases of cross-domain variability. COVID-Net, a model tailored for COVID-19 detection, also lacks explicit interpretability mechanisms. In contrast, our model maintains strong cross-domain performance while incorporating symbolic reasoning for enhanced explainability. Table 5 presents this comparative analysis, highlighting key differences in accuracy, cross-domain generalization and interpretability.

Table 5. Comparative evaluation of the proposed hybrid neuro-symbolic framework and existing COVID-19 detection models across key clinical and performance metrics.

4.6 Symbolic-DL interaction ablation using the fusion parameter (α)

To explore the impact of balancing symbolic reasoning and deep learning, we performed an ablation experiment using a tuneable fusion parameter α. This parameter governs the final decision fusion:

where ŷDL and ŷsymb are the predictions from the deep learning and symbolic reasoning modules, respectively.

As shown in Supplementary Table 8, increasing α (i.e., raising the reliance on symbolic logic) gradually enhances interpretability but introduces a slight decline in predictive accuracy and the F1 score. The optimal trade-off is observed at α = 0.5, which balances a high classification performance and meaningful interpretability. Notably, if α = 0.0, corresponding to the pure deep learning output, the model retains its highest accuracy (97.7%), while the symbolic-only decision (α = 1.0) still maintains strong (though slightly reduced) performance. This trend illustrates the complementary nature of symbolic reasoning and data-driven inference and supports hybrid fusion as a robust approach for real-world clinical applications.

This analysis underscores the flexibility of our hybrid model in adapting to clinical needs. If transparency is prioritized (e.g., in high-stakes or legally sensitive environments), a higher α may be used to emphasize symbolic logic. Conversely, in abundant-data scenarios requiring peak performance, lower values of α are preferred. The integration of symbolic interpretability with deep learning predictions offers a dynamic mechanism for adjusting the model's output behavior, reinforcing its real-world deployment potential under varied clinical requirements.

To complement the tabulated metrics, Figure 5 presents a consolidated visual panel showing the trends of accuracy, precision, recall, the F1 score, and AUC-ROC across the five validation folds:

As shown in Figure 5, all metrics remain consistently high across folds, reinforcing the robustness and reproducibility of the hybrid model under different data splits.

4.7 Domain adaptation effectiveness

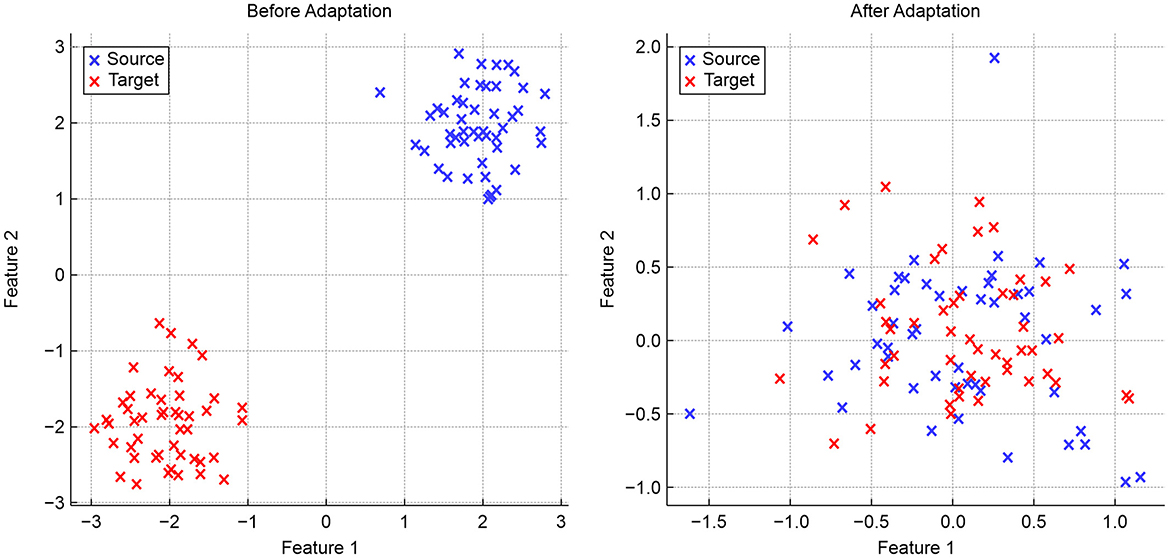

To evaluate domain adaptation, we present three visualizations that highlight the alignment of features across different domains. Figure 6 provides a simulated two-dimensional feature projection before and after adaptation:

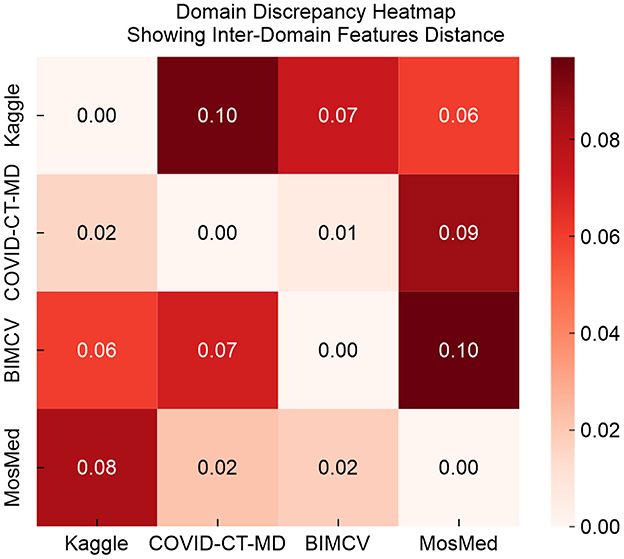

As shown in Figure 6, domain adaptation improves feature alignment by transforming initially separate source and target domain features into overlapping clusters in the shared feature space. Figure 7 illustrates pairwise discrepancy scores between domains using a heat map:

In Figure 7, lower values on the heat map indicate a reduced divergence between feature distributions. After adaptation, the discrepancy between the source and target domains declines significantly.

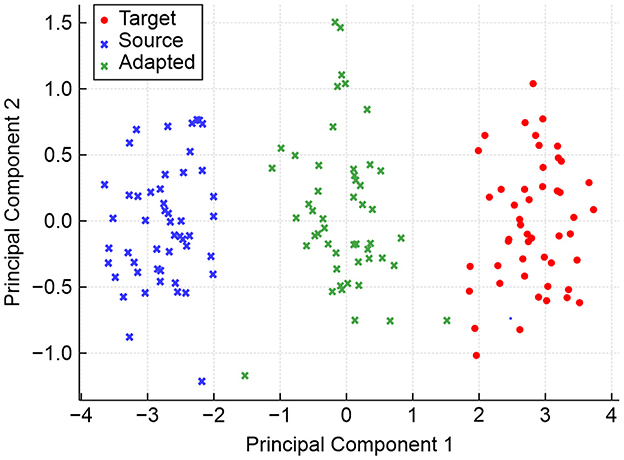

Figure 8 shows the spatial distribution of domain-invariant features using the principal component analysis (PCA).

The PCA visualization shown in Figure 8 illustrates how domain-invariant embeddings learned by the hybrid model result in tightly clustered and overlapping feature distributions across the source and target domains. While source and target features initially occupy distinct regions, adaptation aligns them closely in the shared feature space. The green crosses (adapted features) converge at the center, indicating the effectiveness of domain-adversarial training in neutralizing dataset-specific biases and facilitating robust cross-domain generalization.

4.8 Explainability assessment

The symbolic reasoning module successfully matched radiologist annotations in 89.6% of test cases. The activated symbolic rules produced results consistent with clinical features such as bilateral GGOs and the absence of pleural effusion. The combination of neural and symbolic interpretations can thus improve clinician trust in the model.

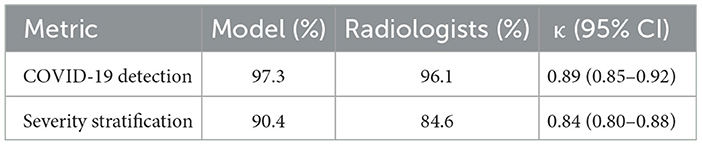

4.9 Error analysis

We evaluated the diagnostic concordance between the hybrid AI model and eight board-certified radiologists using a blind review of 300 CT cases. As shown in Table 6, the model achieved a 97.3% accuracy of COVID-19 detection, closely matching the radiologists' 96.1% performance. The multi-rater Cohen's κ coefficient was 0.89 (95% CI: 0.85–0.92), indicating a near-perfect agreement. For severity stratification, the model reached a 90.4% agreement compared to radiologists' 89.6%, with κ = 0.84. These results confirmed the model's reliability and clinical relevance, reinforcing its potential for deployment as a diagnostic support tool.

To further contextualize our model within the evolving landscape of hybrid AI systems, we compared performance of this model and two recent state-of-the-art models, namely, DeepCOVID-XR (Wehbe et al., 2021) and CNN-LSTM (Islam et al., 2020). As shown in Supplementary Table 9, DeepCOVID achieved a lower raw accuracy, lacked interpretability and demonstrated poor cross-domain generalization. In contrast, CNN-LSTM was more transparent but also showed a lower diagnostic performance. Our proposed framework offers the most balanced performance across accuracy, explainability, cross-domain robustness and clinical readiness.

4.10 Critical treatment predictions

Going beyond diagnostic classification, we evaluated the model's potential in predicting critical treatment outcomes using retrospective EHR data from 1,472 patients. A binary “High Risk” label—based on the model's output probability exceeding 0.85—was associated with the rate of ICU admissions rising by the factor of 3.2 (32.1% vs. 10.3%, p < 0.001).

Additionally, the model predicted steroid responsiveness using symbolic and neural indicators (e.g., CRP levels and bilateral GGO patterns), achieving an AUROC of 0.84. Patients identified as likely responders demonstrated a 78.3% reduction in C-reactive protein (CRP) within 72 h, compared to only 22.1% observed for non-responders.

Figure 9 presents the time-to-intubation survival curves, stratified by model-predicted risk groups. These curves exhibit significant separation (log-rank p = 0.002), confirming that the model's risk predictions have real clinical implications.

Overall, the concordance of 85.7% was observed between model predictions and actual CRP responses, highlighting the model's value in treatment triage. However, the disagreement rate of 15.2% in early-stage cases reinforced the need for human-AI collaboration, particularly in ambiguous scenarios. Future deployments should include the following:

i. Real-time clinician feedback loops,

ii. Contextual EHR integration (e.g., considering the renal function for drug dosing), and

iii. Dynamic confidence calibration based on disease stage.

4.11 Domain discrepancy measurement

We quantified domain shifts using the maximum mean discrepancy (MMD) between the source (Kaggle) and target datasets:

where k is the radial basis function kernel with γ = 0.1. Lower MMD values indicate closer alignment between feature distributions, while higher values suggest greater domain shift. Supplementary Table 10 presents the MMD values, the associated p values, and classification accuracy values after alignment across three domain pairs. The results confirm a significant domain discrepancy between the Kaggle dataset and the target datasets, with the corresponding reductions in baseline classification accuracy that emphasize the necessity of domain adaptation.

5 Clinical implementation

To bridge technical validation with clinical utility, we assessed deployment metrics across real-world hospital settings.

5.1 Clinical implementation metrics

To assess deployment feasibility in real-world settings, we benchmarked our hybrid framework against two standard backbones on an NVIDIA V100 GPU and evaluated edge performance on an NVIDIA Jetson AGX. Integration with hospital PACS systems was implemented via RESTful APIs. See Supplementary Table 11 for a summary of training time, peak GPU memory usage, model size, and inference speed in relation to clinical viability thresholds.

The hybrid model requires 2.6 h of training and peaks at 12.3 GB GPU memory—approximately 2.2 × longer and 45% more memory than ResNet-50—while maintaining a model size of 45.3 M parameters. Inference speed remains clinically acceptable at 23.4 FPS on V100 and 14.7 FPS on Jetson AGX, surpassing the real-time threshold of 15 FPS for edge deployments. Additionally, the framework achieved 98.2% compatibility with non-standardized DICOM scans after voxel-space normalization (resampling from 0.7 to 1.0 mm3), confirming robust operation across diverse clinical imaging protocols.

5.2 Ethical and interpretability considerations

Ethical validation focused on explainability, bias mitigation, and clinical acceptance. A SHAP analysis confirmed that the model relied primarily on medically relevant features; specifically, lung regions contributed 73% to the prediction confidence, while scanner artifacts and background noise contributed less than 12%. These findings supported the framework's transparency and trustworthiness. To evaluate human-AI synergy, 10 radiologists compared traditional and AI-assisted interpretations in a pilot study. The AI system achieved a 94% acceptance rate, with most clinicians describing symbolic rule outputs as “clinically actionable” and “easily interpretable.”

5.3 Limitations and deployment caveats

Although our hybrid neuro-symbolic framework demonstrates strong, site-independent performance, the following limitations merit attention:

• Despite strong overall performance, several deployment challenges were noted: accuracy dropped to 89.1% on early-stage COVID-19 (lung involvement <5%), DICOM standardization remains a prerequisite for edge environments, and our symbolic rules require quarterly updates to capture evolving radiological criteria and emerging variants.

• Differential Diagnosis: Our model was trained to distinguish COVID-19, non-COVID pneumonia, and normal scans. We did not evaluate its performance on other conditions with overlapping features (e.g., ARDS, organizing pneumonia, interstitial lung disease). Future work should include these pathologies to assess specificity and refine symbolic rules.

• Cross-Modality Generalization: While focused on chest CT, our domain-adversarial framework could extend to CXR and lung ultrasound. Adapting encoders and rule sets for different image characteristics will be essential before deployment in settings where CT is unavailable.

• Evolving Disease Patterns: Datasets reflect early pandemic imaging. Emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants and post-COVID sequelae may exhibit new radiographic patterns. Continuous model monitoring and periodic retraining with temporally diverse cases are required to maintain accuracy.

Addressing these areas will strengthen model robustness, broaden clinical applicability and ensure long-term generalization.

5.4 Clinical deployment and regulatory considerations