- 1Net Media Lab & Brain R&D, National Center of Scientific Research “Demokritos”, Institute of Informatics and Telecommunications, Athens, Greece

- 2Department of Special Education, University of Thessaly, Volos, Greece

- 3Department of Primary Education, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Athens, Greece

- 4Department of Information and Communication Systems Engineering, University of the Aegean, Karlovasi, Greece

Emerging technologies, assistive technology, and STEM approaches have emerged as important knowledge-acquisition instruments in contemporary educational practices. These resources support individualized education for those with disabilities, such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), as well as those who are typically developing. Since parents can provide vital information about a child’s temperament, learning preferences, and developmental needs, parental participation has been acknowledged as a significant determinant in children’s educational success. With educational goals in mind, serious games (SGs) provide dynamic and captivating learning environments that improve skill development. The role of parental participation in STEM education and in co-creating serious games for people with ASD is methodically investigated in this scoping review. Twenty of the 334 studies that were reviewed in accordance with PRISMA guidelines met the inclusion criteria. The findings show that active parental involvement empowers parents and children, encourages individualized learning, and increases the efficacy of educational initiatives. A promising strategy for enhancing learning, socializing, and quality of life for people with ASD is the integration of STEM, serious gaming, and parental involvement.

1 Introduction

In the new educational process, the development of emerging technologies, the use of assistive technology and the integration of STEM approaches (Science, Technology, Technology, Technology, Technology, Technology, and Educational Technologies) are becoming essential tools for the acquisition of knowledge. These innovations increasingly support both individuals within formal education and those with developmental or learning differences, as they remove barriers and enhance learning adapted to the interests and characteristics of each individual. STEM, as an interdisciplinary approach that combines Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics, promotes problem solving, collaboration and creative thinking - skills essential for success in the 21st century.

In addition, parents play a decisive role in the education of their children, especially children with autism, as they have valuable knowledge about their child’s temperament and abilities, contributing to the development of personalized and effective learning programs. Collaboration between parents, educators, and technology, along with the active participation of parents in the co-design of educational tools and serious games, reflects the direction that contemporary educational policy seeks to promote (Chaidi et al., 2021; Kefalis et al., 2020, 2024, 2025). Parental involvement in the learning process, combined with STEM-based approaches and the use of serious games, has shown promising results for individuals with disabilities - especially those on the autism spectrum—enhancing learning engagement and improving the quality of life for both the child and the family.

However, as highlighted in “Trends in instructional technologies used in education of people with special needs due to intellectual disability and autism,” a significant research gap remains in the lack of primary empirical studies evaluating emerging and advanced technologies (such as artificial intelligence, personalized learning, and hybrid or virtual reality) in the education of people with intellectual disabilities or autism. Existing studies focus primarily on communication and social skills, leaving other critical areas—such as academic learning, daily living skills, and autonomy, particularly among adolescents and adults—largely unexplored. This gap highlights the need for future research that incorporates adaptive AI-based systems and smart learning environments to enhance inclusion and personalization in education for people with disabilities (Kalemkuş, 2025).

1.1 Stem and parental involvement

Parental involvement has long been recognized as a critical contributor to student success, with numerous studies highlighting its positive impact on academic achievement, motivation, and long-term educational outcomes across diverse subject areas (Fan and Chen, 2001). In STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) education, where students often face complex problem-solving tasks and conceptual challenges, supportive home environments and parental engagement can play a vital role in sustaining interest and enhancing learning (Garriott et al., 2014).

Simultaneously, serious games—digital games designed with educational objectives—have emerged as a powerful tool in STEM education. These games aim to foster engagement, conceptual understanding, and skill development by integrating curriculum content into interactive and often playful environments (Kangas et al., 2016). Serious games have been shown to support inquiry-based learning, promote collaborative problem-solving, and bridge formal and informal learning contexts (Qian and Clark, 2016).

However, while the literature on serious games in STEM education has grown rapidly over the past decade, relatively little attention has been paid to the role of parents within these game-based learning environments (Hidayat, 2022). Most studies focus on the interaction between students and technology, overlooking the potential influence of parents as facilitators, co-players, motivators, or even learning partners in serious game settings. This is particularly noteworthy given the increasing prevalence of home-based or hybrid learning models, which inherently position parents closer to the learning process (Gülhan, 2023). Understanding how parental involvement intersects with the use of serious games in STEM education is crucial for both researchers and practitioners aiming to design inclusive, effective, and sustainable educational interventions.

1.2 Parental involvement in the education of individuals with ASD

The education of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) poses significant challenges for both parents and educators, requiring acceptance, patience, and collaborative engagement to foster social integration and autonomy. Parental participation is widely recognized as critical, with parents acting as “experts” on their child’s behaviors, routines, and needs, providing essential insights for diagnostic, educational, and therapeutic processes (Chaidi and Drigas, 2020). In Greece, Law 3699/2008 mandates parental involvement in the development of Individualized Education Programs (IEPs), while internationally, IDEA requires collaboration at all stages of planning. Active parental participation ensures that goals are aligned with real needs, enhances home-school communication, and supports continuous monitoring of progress. Typical forms of engagement include attending meetings, providing feedback, and receiving training for home-based interventions.

Parents play a pivotal role in the development of Individualized Education Programs (IEPs), contributing unique knowledge of their child’s strengths, needs, and daily routines. Their participation allows for the establishment of individualized goals, facilitates continuous monitoring of behaviors, and strengthens collaboration between educators and families. Moreover, parents support the adaptation of educational programs to align with the child’s personal, cultural, and emotional context, thereby enhancing both the relevance and efficacy of interventions.

1.2.1 Serious games and ASD

Serious games (SGs) have emerged as innovative tools for promoting education, social inclusion, and emotional empowerment among children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) (Carneiro et al., 2024; Stasolla et al., 2025). Given the heterogeneous profiles of this population, personalization is essential (Chaidi et al., 2024). Parental involvement in SG design increases the functional relevance and engagement of such interventions, enabling games to provide stimulating and adaptive learning environments, structured and safe practice spaces for social and communication skills, and targeted opportunities to develop emotion recognition, attention, and anxiety regulation. Furthermore, games can be adjusted to each child’s learning pace and profile, optimizing individualized support (Bravou et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2024).

1.2.2 The role of parents in SG co-design

Parents’ insights regarding sensory sensitivities, emotional triggers, and communication patterns inform the design of tailored game features, promoting engagement and facilitating the generalization of skills to real-world contexts. Key principles guiding co-design include personalized customization (content, rewards, esthetics, pacing), skill generalization (integration of in-game learning into daily activities), predictability and structure (clear objectives and consistent feedback), sensory regulation (adjustment of audiovisual settings to prevent overstimulation), and facilitation of communication and joint attention through collaborative interactions.

Parental involvement in SG development is commonly operationalized through participatory design frameworks, encompassing workshops, iterative prototype testing, and proxy participation for children with severe challenges (El Shemy et al., 2023; Wang et al., 2023). Notable examples include SALY, which enhances attention and emotional understanding (Stasolla et al., 2025); Secret Agent Society, supporting social–emotional skill acquisition through co-designed missions (Beaumont et al., 2021); and New Horizon, SpaceControl, ECHOES, and TEO, all developed collaboratively with parents and therapists to reduce anxiety and support communication.

2 Methodology and objectives

2.1 Objectives

This paper aims to present the results of the parental involvement in the educational process with the help of STEM, the role of STEM, as well as research related to parental involvement in designing programs for the education of individuals with educational problems.

Particular emphasis is placed on how STEM can act as a bridge between school and home, strengthening collaboration between parents and teachers through activities that can be used together, adapted to the needs of children.

Also, the objectives of this paper are: to analyze how parental involvement in education can enhance the development of skills of people with disabilities, to explore the application of STEM as an educational tool for people with learning disabilities, to examine the development of a serious game that will support the learning and socialization of people with ASD, and the application of technological tools (STEM and serious games) to improve the educational process.

2.2 Method

This paper conducts a scoping review according to PRISMA guidelines from literature databases that explored research studies in five areas: STEM, engaging parents, and educating people with impairments. Also, research on the involvement of parents in the education of individuals with educational needs, but also in SG design.

Will be used:

a. Qualitative and quantitative methods to examine parental involvement and the use of STEM in the education of people with disabilities.

b. Presentation of the process of designing a serious game for people with autism syndrome, focusing on the features that make the game suitable for supporting educational needs.

c. Exploring how serious games and STEM influence the learning process and parental involvement.

2.3 Stem (PRISMA)

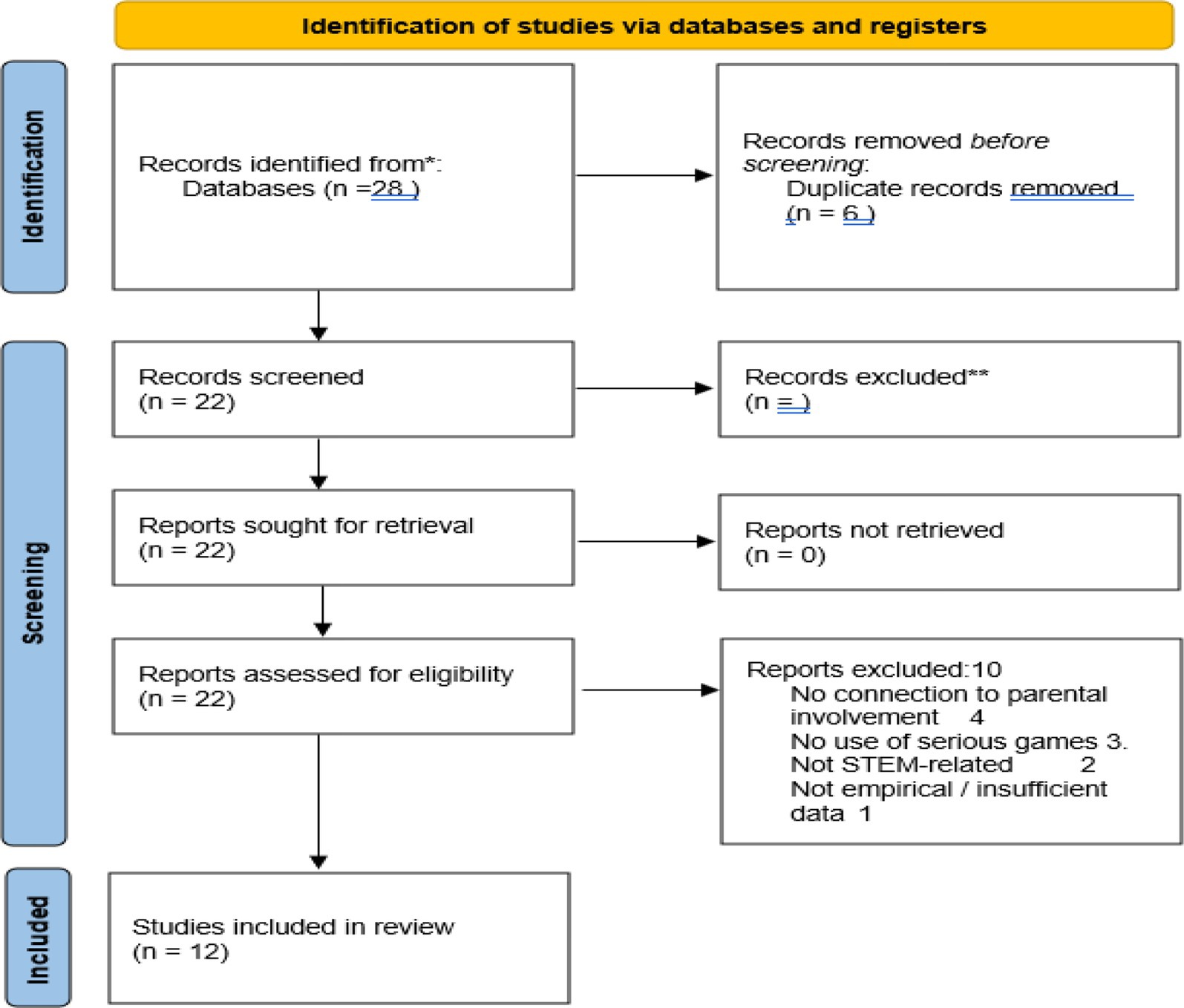

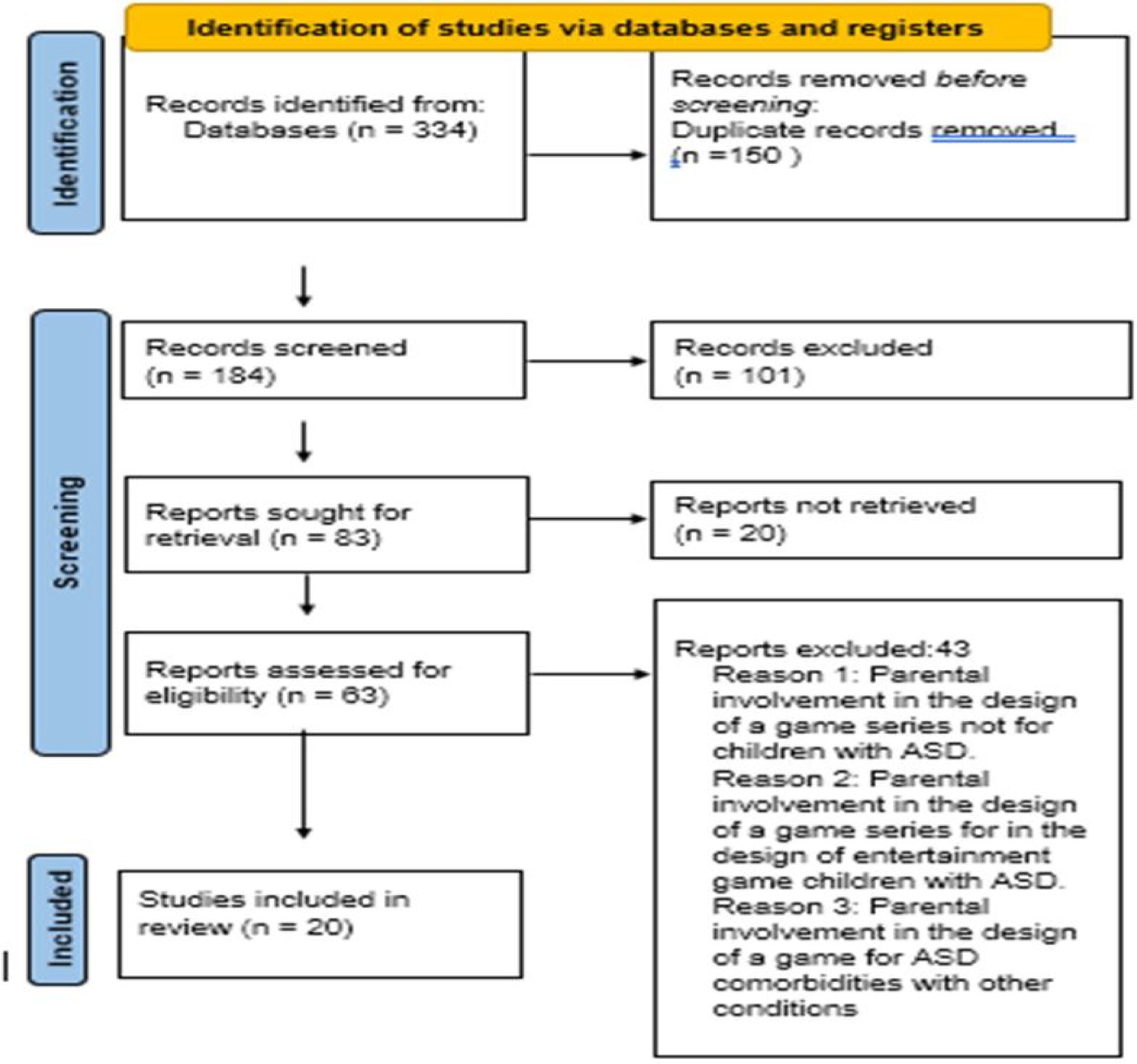

This study follows the PRISMA (Figure 1) (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) methodology (Page et al., 2021) to identify and analyze peer-reviewed research articles on parental involvement in STEM education using serious games.

Figure 1. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram foe STEM (Page et al., 2021).

Relevant literature was identified through structured searches in five academic databases: Scopus, ERIC, Web of Science, and ACM Digital Library. The search was conducted in June 2025, targeting publications from January 2015 to June 2025. The following Boolean search string was used and adjusted according to the syntax of each database:

> (“serious games” OR “educational games”) AND (“parental involvement” OR “parent engagement” OR “family participation”) AND (“STEM education” OR “science” OR “technology” OR “engineering” OR “mathematics”).

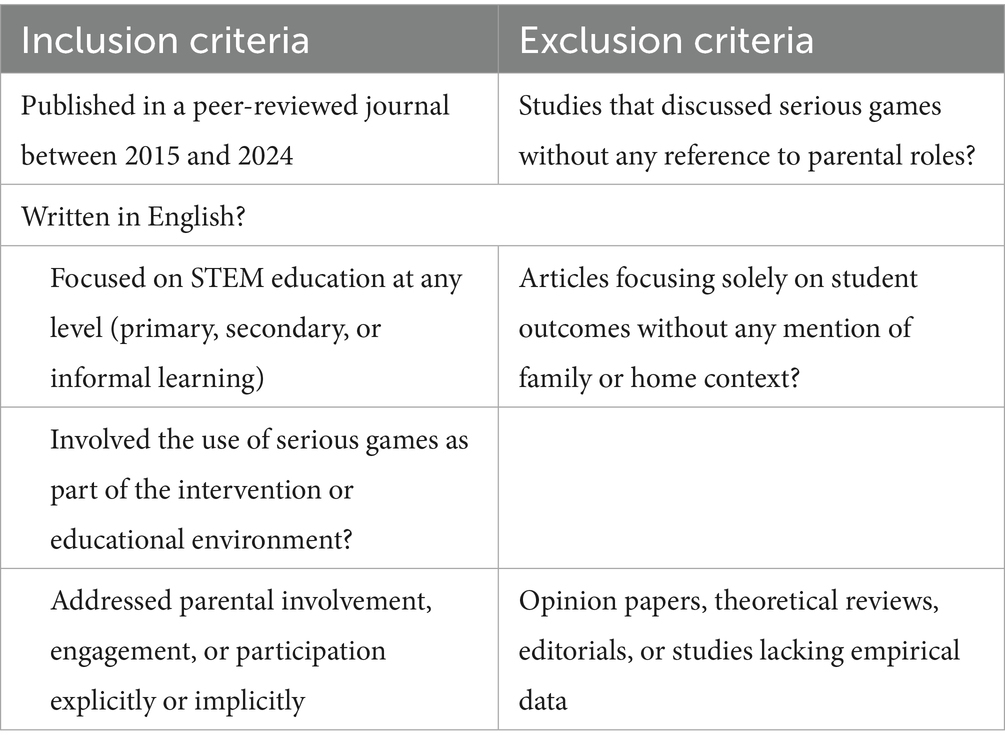

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they met all of the predefined criteria listed above, while studies that did not fulfill these requirements were excluded (Table 1).

The screening process was carried out in two stages. First, duplicates were removed, and the remaining titles and abstracts were screened for relevance. Second, full-text screening was conducted to determine eligibility based on the inclusion criteria. The researchers independently reviewed and discussed any discrepancies in study selection.

2.4 Serious game (PRISMA)

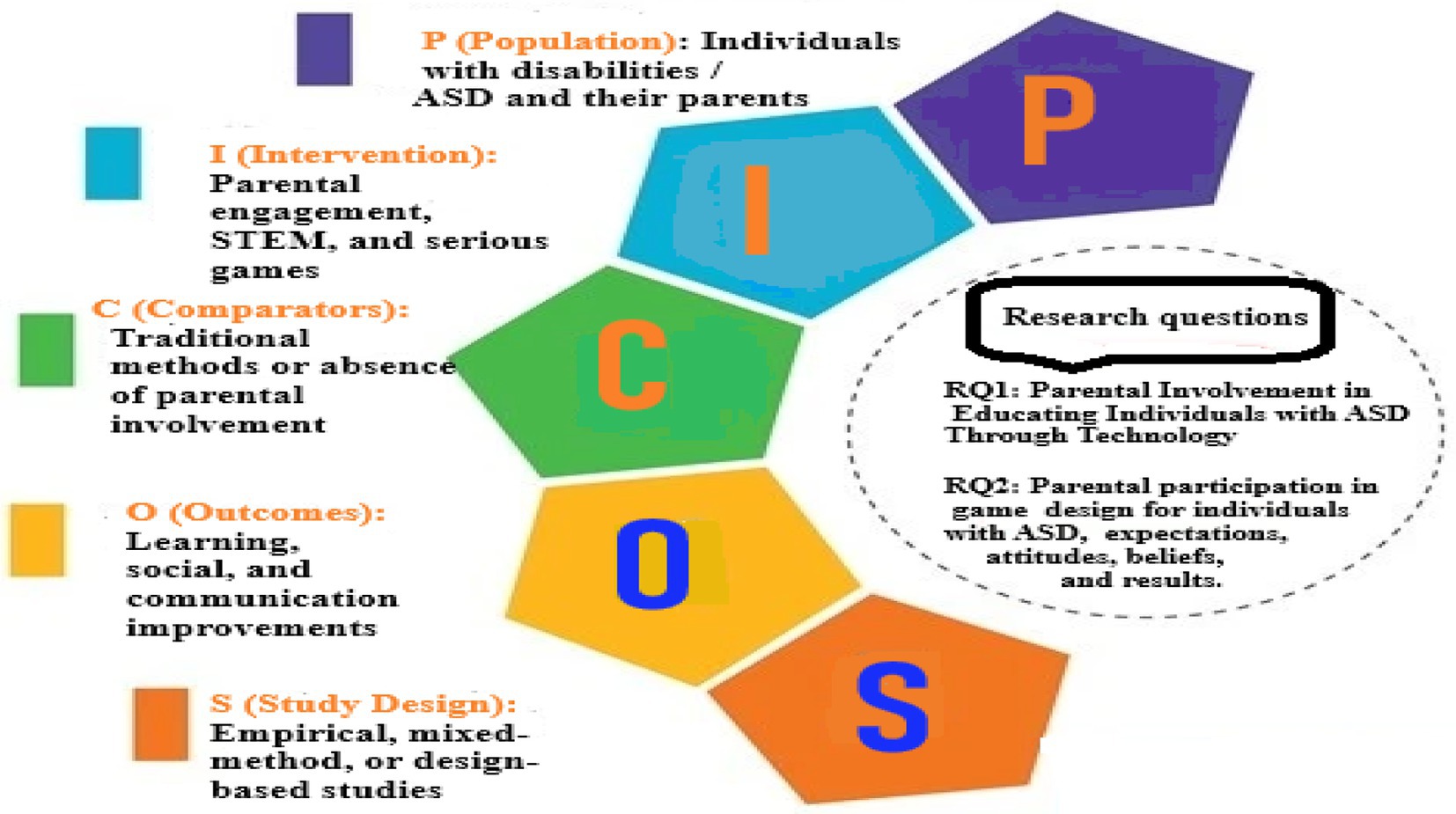

RQ1: Parental involvement in educating individuals with ASD through technology.

RQ2: Parental participation in game design for individuals with ASD, expectations, attitudes, beliefs, and results.

A comprehensive literature review on serious games was conducted, with particular attention to parental engagement in the development of serious educational games. The selected databases provided access to a wide range of academic publications, offering valuable perspectives on the active involvement of parents in designing serious games for the education of individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

This study aimed to provide a comprehensive overview of current trends in parents’ active involvement in the development of serious educational games (SEG) for individuals with ASD. The focus was to highlight recent research reflecting the growing role of parents in planning special education needs (SEN) for these individuals. Over the past 15 years, this field has expanded significantly, recognizing that SEN tools can support the education of people with ASD. Moreover, increasing evidence confirms that parental involvement plays a crucial role in their children’s learning and development. The selected studies offer updated insights into how parents contribute to the design and development of serious games for their children.

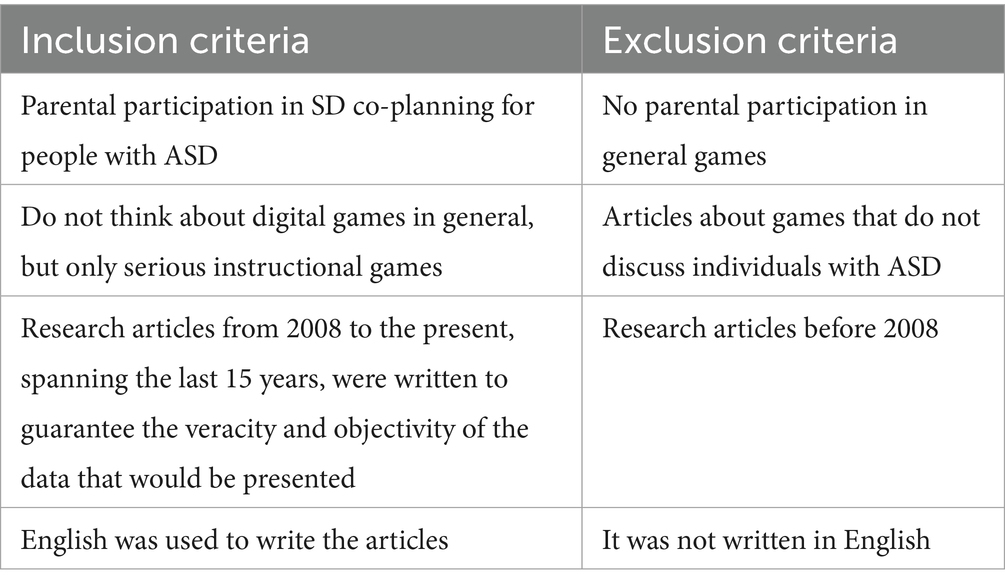

Research questions were generated with PICO (Figure 1) and for the systematic collection of articles for this review, using a precise and thorough search strategy, a PRISMA 2020 (Figure 2) was employed in five prestigious academic databases: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Medline, and Google Scholar. The research questions were developed to systematically gather articles for this review. “Serious Games,” “Autism Spectrum Disorder,” “Research Review,” “Serious Game Development,” “Serious Game Design,” “Parental Involvement,” and “Education of Individuals with Disabilities” were the specific search terms that were used.

After applying the processing, inclusion, and representativeness criteria for the main part (n = 20) to the final selection for additional analysis and data extraction, n = 334 articles were found and screened for the final selection of included articles in accordance with the selection criteria used in this literature review. Analysis of the literature took place from 2008 to May 2025. The process of exclusion began with the creation of eligibility criteria. To start the database search, a list of keywords was also made. Boolean operators and other search filters were utilized to get the most results. Following the removal of duplicate studies (n = 150), Title and abstract selection was used to make the choice based on the qualifying requirements (n = 184). Following the elimination of (n = 101) articles, the process moved on to full-text selection (Figure 3). A thorough screening was performed on the remaining studies (a total of 83). Seven papers, regrettably, could not be obtained for full-text evaluation. Two independent reviewers examined the full texts of n = 63 publications as part of the final selection process, and they also talked about how the eligibility criteria should be applied. Due to their failure to satisfy the qualifying standards, the remaining n = 43 entries were eliminated (Table 2). The final list thus consists of n = 20 entries. A overview of the findings is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 3. PRISMA 2020 flow diagram (Page et al., 2021).

3 Results

From the bibliographic references of the articles, it will be possible to:

a. Presentation of the results of parental involvement in the educational process and their participation in the use of STEM for people with disabilities.

b. Analysis of the effectiveness of serious games in the development of social, communication, and cognitive skills of individuals with autism syndrome.

c. Evaluation of the improvement of learning and socialization of people with disabilities through the implementation of STEM and the use of serious games as an impact on education.

3.1 Analysis articles for STEM

The initial database search yielded 28 records: 14 from ERIC, 6 from Scopus, 5 from Web of Science, and 3 from the ACM Digital Library. After removing 6 duplicates, 22 unique records remained. These were screened based on titles and abstracts, followed by full-text assessment according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. A total of 12 studies were ultimately included in the final synthesis. These studies examined various forms of parental involvement within STEM educational contexts that utilized serious games, either as part of formal curricula or through informal and home-based learning environments.

3.1.1 Educational level

The 12 studies included in the final synthesis span a range of educational levels, with a strong emphasis on early childhood and primary education. Four studies focused exclusively on preschool settings (Lange et al., 2021; Linder and Emerson, 2019; Schenke et al., 2020; Young et al., 2023), five targeted primary school contexts (Amelia et al., 2023; Chiu and Zhu, 2025; Poddar et al., 2024; Shivraj et al., 2018; Sýkora et al., 2021), and two addressed both preschool and primary levels (Bustamante et al., 2020; Yu et al., 2021). Only one study involved secondary education (Mangram and Solis Metz, 2018). This distribution reflects a growing interest in involving parents during the early stages of STEM education, where foundational skills are first developed and family involvement tends to be more prevalent and influential (Salvatierra and Cabello, 2022).

3.1.2 STEM subject

Regarding subject focus, all 12 studies included mathematics as a core component of their serious game interventions. Eight studies focused exclusively on mathematics (Chiu and Zhu, 2025; Lange et al., 2021; Linder and Emerson, 2019; Mangram and Solis Metz, 2018; Schenke et al., 2020; Shivraj et al., 2018; Sýkora et al., 2021; Young et al., 2023), while four integrated mathematics with other domains such as science, literacy, computer fluency, or computational thinking. Specifically, two studies addressed both mathematics and science (Bustamante et al., 2020; Poddar et al., 2024), and two others combined mathematics with areas such as literacy, digital fluency, or computational thinking (Amelia et al., 2023; Yu et al., 2021). This notable emphasis on mathematics highlights its prominence in early STEM education, as well as its adaptability to serious game formats that emphasize symbolic reasoning, logical thinking, and quantitative problem-solving (Papadakis et al., 2018).

3.1.3 Game type classification

The analysis revealed a wide variety of game formats used across the 12 studies. Three studies employed digital serious games, including one based on virtual reality (VR) (Chiu and Zhu, 2025; Schenke et al., 2020; Sýkora et al., 2021). Another three utilized partially digital environments, such as educational apps with game-based features or interactive voice response (IVR) games (Amelia et al., 2023; Poddar et al., 2024; Yu et al., 2021). The remaining six studies relied on non-digital or analog serious games, including board games (Mangram and Solis Metz, 2018), number-based bingo (Shivraj et al., 2018), and other physical or paper-based formats (Bustamante et al., 2020; Lange et al., 2021; Linder and Emerson, 2019; Young et al., 2023). In these cases, the games were designed to promote specific mathematical or logical skills while incorporating play-based elements aligned with serious game principles. This distribution indicates that while digital serious games are increasingly present in STEM education, many interventions involving parents still rely on low-tech or hybrid approaches—likely due to accessibility, age-appropriateness, or the informal nature of family-based learning contexts (Zucker et al., 2024).

3.1.4 Typologies of parental involvement

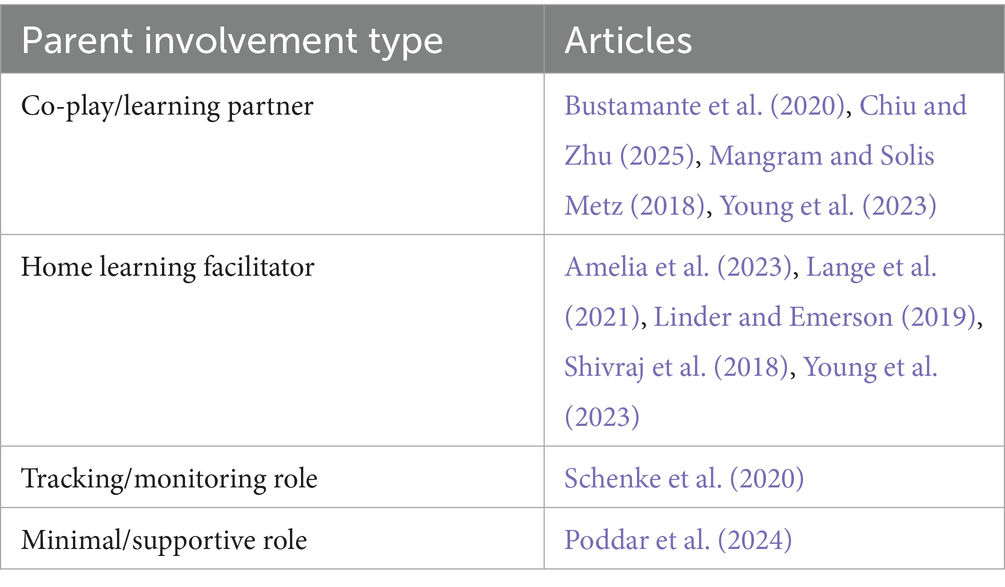

The reviewed studies exhibited a variety of parental involvement roles, which were categorized into four main types.

3.1.4.1 Co-play and learning partner (n = 4)

In these cases, parents participated directly in the gameplay or associated learning tasks. Activities included structured co-play, reflective conversations, and joint exploration of educational content.

3.1.4.2 Home learning facilitator (n = 5)

Parents supported their children’s learning at home, often using resources provided by teachers (eg, math kits, mini-books, or digital instructions). Their role was to reinforce learning in informal or semi-structured home settings.

3.1.4.3 Tracking and monitoring role (n = 1)

In one study, parents used companion apps, sticker charts, or surveys to track children’s progress or provide basic data. These tools enabled light-touch engagement without active instructional participation.

3.1.4.4 Minimal or supportive role (n = 2)

In a few cases, parental involvement was limited to basic logistical or safety-related tasks—such as installing apps or being present during digital activities—without participating in the educational experience itself (Table 3).

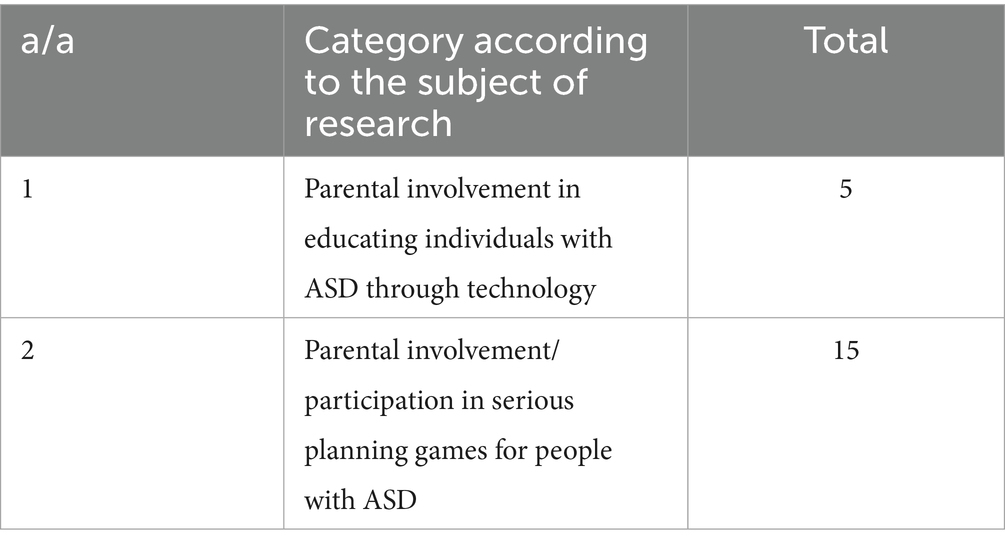

3.2 Analysis of articles on parental involvement in the education of individuals with ASD via serious game—classification of bibliographic sources for parental involvement in serious games for children with ASD

The collected research papers, a total of 20, were grouped into the following 2 categories according to the subject of research:

RQ1: Parental involvement in the education of individuals with ASD through technology, attitudes, beliefs, results.

Active parental involvement in the education of individuals with ASD is a very important factor for the improvement, development, and progress of individuals with ASD.

Thus far, research has documented the significance of parental involvement in their children’s education (Askari et al., 2015; Chaidi and Drigas, 2020), the focus on psycho-educational support for parents (e.g., Magaña et al., 2017), the evaluation of parental involvement in therapies and educational programs (Clancy, 2017), the perception of parental involvement in school and IEP (Goldman and Burke, 2019; Kurth et al., 2020), and the impact of parental involvement on child development (Fernández Cerero et al., 2024; Müller et al., 2024). Research demonstrates that parental support and involvement in their children’s education is critical to their development and social empowerment. Parents gain cognitive and emotional strength and become important collaborators in their children’s development through psychoeducational programs, therapy participation, and active involvement in educational processes (such IEPs). The success of interventions depends on the systematic support of parents, despite any institutional, cultural, or communication barriers.

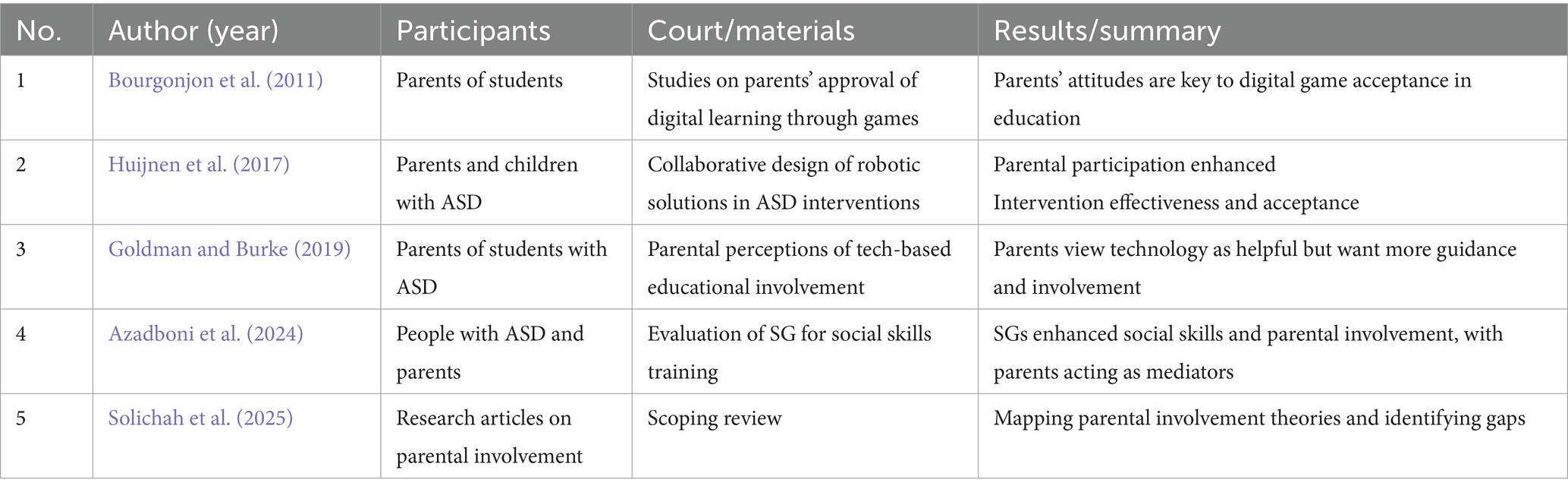

Parental involvement in the education of individuals with ASD is also provided through technology (Table 4).

The success and sustainability of interventions for individuals with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) increasingly depend on parental involvement in their education through technology. Numerous studies indicate that when parents actively participate, children are more likely to engage with technological tools and adapt them to their individual needs. Research examining parental involvement in technology-based education for students with ASD highlights that when parents understand and engage with digital educational games and robotic interventions, their acceptance of these methods increases. Furthermore, professional guidance and consideration of parental perspectives enhance the effectiveness of technology-based therapies, including serious games.

Bourgonjon et al. (2011) note that when parents recognize the educational value of digital media, their acceptance of digital games rises, facilitating their integration into classroom settings. Huijnen et al. (2017) extend this perspective, showing that co-creation in robotic interventions—where parents help define objectives and strategies—enhances both efficacy and acceptance. Co-design thus emerges as a strategy for tailoring interventions to meet the unique needs of each child. Similarly, Goldman and Burke (2019) reports that while parents generally hold positive views toward classroom technology, they seek more active involvement and professional guidance, underscoring the importance of building trustful relationships with professionals and providing relevant parental support and education.

Research by Azadboni et al. (2024) highlights serious gaming as a tool for developing social skills while positioning parents as active mediators in the learning process rather than passive observers. Solichah et al. (2025), in a retrospective study, map theoretical frameworks for parental participation and emphasize the need for further research on models that integrate technology and collaborative learning.

Overall, evidence demonstrates that technological support in the education of individuals with ASD is maximized when parents: are informed about available technology, participate in designing or implementing interventions, recognize their contributions to their children’s development, and collaborate with professionals while trusting the process. Strong family-professional collaboration and parental trust in technology are therefore essential to ensure that technology-based interventions for individuals with ASD are effective, personalized, and sustainable.

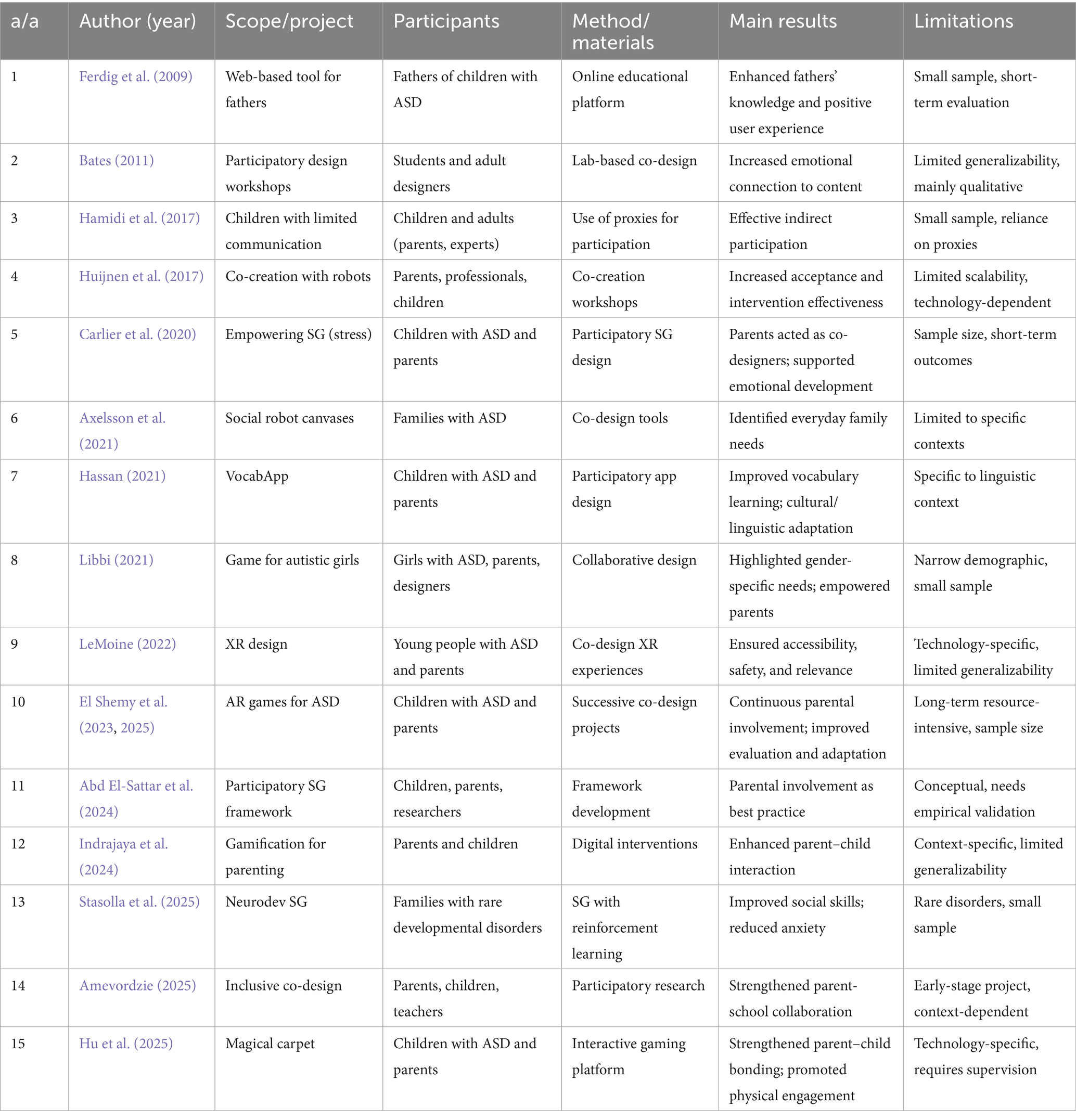

RQ2: Parental involvement in game design for individuals with ASD, expectations, attitudes, beliefs, and results.

Educational games, particularly Serious Games (SGs), are increasingly recognized as technological applications for learning in individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). Recent research highlights their potential as both educational and therapeutic tools, supporting the development of social and emotional skills (de Carvalho et al., 2024; Grossard et al., 2017), managing anxiety and stress (Carlier et al., 2020), reinforcing motor skills (Müller et al., 2024), and integrating into complex intervention models such as reinforcement learning (Stasolla et al., 2025). Studies focus on areas including game design for social skills and emotional learning (Grossard et al., 2017), new digital health interventions through serious games (Vacca et al., 2023), systematic reviews of SGs for children with ASD (Carlier et al., 2020; de Carvalho et al., 2024), stress management through game design (Carlier et al., 2020), the combination of artificial intelligence with SGs (Stasolla et al., 2025), and linking parental involvement with educational outcomes (Fernández Cerero et al., 2024; Müller et al., 2024). Parental participation is a critical factor for the success of these interventions, offering personalized support and improving the transfer of learned skills to daily life. In the co-design of serious games for individuals with ASD, parents contribute essential knowledge, sensitivity, and experience, ensuring that SGs are realistic, developmentally appropriate, and acceptable to children. Participatory design enhances pedagogical relevance, usability, and personalization while fostering psychological empowerment, as parents recognize the tangible impact of their contributions. Emerging trends in inclusivity—considering gender, age, and preferences—along with the adoption of technologies such as AR, VR, and XR, further expand opportunities for innovation and inclusion in the field.

Parental involvement in planning Serious Games (SGs) for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is crucial for creating meaningful, functional, and widely accepted interventions. Participatory and co-design approaches, including co-creation workshops (Huijnen et al., 2017), design tools like “canvases” (Axelsson et al., 2021), and engagement in interactive environments (Hu et al., 2025), ensure that SGs address everyday challenges, are culturally appropriate (Hassan, 2021), and enhance social interaction (Stasolla et al., 2024). Projects such as Empowering SG (Carlier et al., 2020) and AR Games for ASD (El Shemy et al., 2023, 2025) demonstrate that continuous parental participation improves adaptability and sustainability, while approaches like Inclusive Co-Design (Amevordzie, 2025) promote collaboration among parents, children, and schools. Attention to gender (Libbi, 2021), linguistic and cultural diversity (Hassan, 2021), and rare neurodevelopmental disorders (Stasolla et al., 2024) further supports differentiated and inclusive practices. Additionally, digital gamification shows promise for strengthening parent–child relationships (Indrajaya et al., 2024), highlighting its potential to enhance emotional connection alongside learning outcomes.

In detail:

Integrating parents into planning Serious Games (SG) for children with ASD has emerged as crucial to the success of such interventions. The study by Ferdig et al. (2009) demonstrated the effectiveness of an online training tool for fathers of children with ASD, enhancing knowledge and providing a positive user experience. Similarly, Bates (2011) work highlighted that involving students and adults in SG design through workshops increases emotional connection to the content.

Hamidi et al. (2017) approached children with limited communication using proxies such as parents and experts, demonstrating that indirect participation is feasible and effective. In the same year, Huijnen et al. (2017) highlighted the importance of co-creation using robots, where parental involvement increased families’ acceptance of the technology.

The Empowering SG project (Carlier et al., 2020) focused on the anxiety of children with ASD and highlighted the value of parents as co-designers, while Axelsson et al. (2021) developed tools such as “canvases “to identify everyday needs of families with ASD. Hassan’s (2021) VocabApp demonstrated how parents can identify linguistic and cultural parameters useful in the design of educational tools.

Libbi’s (2021) study, the need for gender-specific game design for girls with ASD was highlighted, while LeMoine (2022) leveraged parental involvement in the design of XR experiences, ensuring accessibility and safety. El Shemy et al. (2023, 2025) offered a long-term example of the gradual development of AR games, with consistent parental involvement in evaluating and improving the tools.

Abd El-Sattar et al. (2024) proposed a developmental SG framework that incorporates parental involvement as a best practice, while Semwaiko (2024) presented digital gamification as a means of strengthening the parent–child relationship. Stasolla et al. (2024) used reinforcement learning in families with rare neurodevelopmental disorders, with positive results in the children’s social skills.

Amevordzie (2025) highlighted the value of participatory research in SG co-design, improving educational responsiveness and strengthening the parent-school relationship. Finally, Hu’s Magicarpet and al (2025) was an interactive platform that enhanced the physical and emotional child–parent connection through play.

Studying the above articles leads us to the conclusion that:

1. Parental involvement in all stages of planning (idea, implementation, evaluation) enhances the relevance of the content and acceptance by the child (Carlier et al., 2020; Hamidi et al., 2017; El Shemy et al., 2023, 2025).

2. Parents act as “translators” of needs, especially when children have limited communication, facilitating inclusive design (Hamidi et al., 2017; Axelsson et al., 2021).

3. Participatory planning with parents leads to personalized interventions that take into account socio-emotional and linguistic factors (Hassan, 2021; Libbi, 2021).

4. Technological tools (XR, AR, RL) particularly benefit from parental involvement, as safety, appropriateness, and accessibility are ensured (LeMoine, 2022; Stasolla et al., 2024).

5. It is proposed to develop models of parental participation in collaboration with specialists, educators, and designers, to enhance systematicity and knowledge transfer (Abd El-Sattar et al., 2024; Amevordzie, 2025).

Overall, all of the above projects confirm that meaningful parental participation in SG design not only improves the functionality and acceptance of applications but also strengthens the parent–child relationship and the social integration of children with ASD.

In conclusion, the active participation of parents in SG planning is recognized as crucial for enhancing the effectiveness, acceptance, and emotional connection of the child with the game.

4 Discussion and critical analysis

4.1 Reported outcomes (STEM)

Out of the 12 studies reviewed, 10 explicitly reported outcomes related to parental involvement in STEM education through serious games or game-based interventions. The nature and specificity of these outcomes varied considerably.

Several studies documented positive changes in parental behavior and engagement. For instance, the take-home math bag intervention (Linder and Emerson, 2019) reported a marked increase in parent–child math interactions, along with improved parental awareness and role adaptation. Similarly, a five-session workshop-based intervention (Mangram and Solis Metz, 2018) led to improved parental engagement and greater child participation in mathematical practices. The study “More Than Just a Game” (Bustamante et al., 2020) observed increased caregiver–child interaction and STEM-related language use during gameplay.

Other studies focused on learning outcomes for children, while still acknowledging the parents’ role. The “Measure Up!” iPad study (Schenke et al., 2020) found gains in children’s measurement understanding but no added benefit from the parent tracking app, likely due to low usage. A study combining classroom and home math activities (Young et al., 2023) showed significantly greater math gains in children, particularly when both components were present. Another study (Ramani and Siegler, 2008) linked higher exposure to number games with improved numerical identification and verbal counting, although no effect was attributed to the home component due to implementation issues.

Some research explored factors influencing parental roles, such as technology acceptance or facilitation strategies. For example, one study (Chiu and Zhu, 2025) analyzed the factors shaping parental acceptance of educational VR, while another (Yu et al., 2021) identified four facilitation patterns (designing, managing, instructing, resourcing) adopted by parents during pandemic-driven digital learning. The study on designing culturally relevant home materials (Shivraj et al., 2018) emphasized the co-development of resources to support family learning at home.

A further study (Amelia et al., 2023) found a positive correlation between maternal involvement and student engagement in digital learning tools. In contrast, two studies (Poddar et al., 2024; Sýkora et al., 2021) did not report parent-related outcomes: one focused primarily on child engagement and narrative features, while the other emphasized teacher observations without examining parental behavior.

Overall, while the majority of studies included some form of outcome related to parental involvement, the methodological rigor and depth of outcome analysis varied widely across the literature.

4.2 Reported outcomes (SG)

4.2.1 Parental involvement in the education of individuals with ASD through technology, attitudes, beliefs, results

The analysis of studies (Table 4) on parental involvement in the education of individuals with.

ASD through technology highlights the pivotal role of parents in the acceptance and effectiveness of interventions. Bourgonjon et al. (2011) and Goldman and Burke (2019) report that parents generally view digital tools positively but express a need for guidance and greater engagement. In contrast, Huijnen et al. (2017) and Azadboni et al. (2024) demonstrate that active parental participation in the design or implementation of technological solutions enhances both intervention effectiveness and acceptance.

Despite these positive findings, notable methodological gaps exist. Study designs range from quantitative perception surveys to participatory design approaches, often with small and specific samples, limiting generalizability. Long-term evaluation of parental involvement impacts is rare, and qualitative insights into parents’ experiences remain limited. Scoping reviews, such as Solichah et al. (2025), often face restricted database coverage and language biases.

Future research should combine quantitative and qualitative methods with larger, multicenter samples, evaluate long-term educational and socio-emotional outcomes, and consider cultural, linguistic, and socioeconomic factors influencing parental involvement.

4.2.2 Parental involvement in game design for individuals with ASD, expectations, attitudes, beliefs, and results

The reviewed studies (Table 5) provide robust evidence on the value of parental involvement in the education of children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) through serious games (SGs) and technological tools. Active parental participation consistently enhances learning outcomes, social and emotional development, and the acceptance and personalization of interventions. However, a closer examination of the literature reveals several points of divergence and methodological limitations that warrant discussion (Table 6).

4.2.2.1 Conflicting findings

While most studies highlight positive outcomes of parental involvement (e.g., Fernández Cerero et al., 2024; Stasolla et al., 2024), some reports indicate variability in effectiveness depending on the level of engagement, socio-economic factors, or prior technological familiarity of parents (Goldman and Burke, 2019). Differences also emerge regarding the impact of SGs on stress management or motor skills, suggesting that not all games achieve intended objectives equally.

4.2.2.2 Methodological gaps

Several studies rely on small sample sizes or case studies, limiting generalizability (Ferdig et al., 2009; Bates, 2011). There is also a lack of standardized evaluation frameworks, making comparisons across studies challenging (Stasolla et al., 2025; Hijab et al., 2023). Furthermore, few studies systematically examine long-term effects or retention of learned skills, and cultural and linguistic diversity are not consistently addressed, potentially introducing bias.

4.2.2.3 Quality and limitations of studies

The studies included demonstrate heterogeneity in research design, participants, and outcome measures. Some rely primarily on parental self-report or subjective evaluation, which may introduce reporting bias. Additionally, the role of teachers and professionals is not always clearly integrated into the research design, limiting understanding of tripartite collaboration between parents, children, and educators.

4.2.2.4 Future research directions

Based on these limitations, future research should:

• Develop standardized, evidence-based frameworks for assessing SGs and parental involvement.

• Examine long-term efficacy, skill generalization, and sustainability of interventions.

• Include diverse populations to address cultural, linguistic, and socio-economic variability.

• Explore the mechanisms through which parental participation directly affects educational outcomes, particularly in technology-mediated interventions.

In conclusion, while parental involvement in SGs for children with ASD is clearly beneficial, methodological heterogeneity, small sample sizes, and limited standardization underscore the need for more rigorous, systematic research. Addressing these gaps will strengthen evidence-based recommendations and optimize the design and implementation of inclusive, effective, and sustainable digital interventions for children with ASD.

5 Findings—suggestions

Indicatively, studies demonstrate that the integration of STEM activities, such as educational robotics, simple experiments, or programming applications, can enhance student participation and application, while parental involvement in these activities enhances support and continuity of learning in the family environment.

More specifically regarding:

a. Parental Involvement: Parental involvement increases the success of educational efforts and enhances learning through STEM, as it provides a solid base of support.

b. Results of Serious Games: Serious games offer personalized learning, encourage collaboration, and offer an interactive experience that enhances socialization and communication skills.

c. Identification of the Need for Individualization: Specially adapted tools and strategies, based on the needs of individuals with autistic syndrome, improve outcomes and enhance parental participation.

Parental involvement is crucial for the success of serious games (SGs) for children with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), yet several challenges remain. Translating parental knowledge into game mechanics requires close collaboration with developers (Fletcher-Watson et al., 2016), while ensuring usability and accessibility depends on incorporating parental feedback into sensory-friendly and clear designs (Beaumont et al., 2021). Participatory planning demands significant time and effort from both parents and professionals (El Shemy et al., 2023; Cohrdes et al., 2021). Further limitations include the lack of standardized evaluation frameworks (Stasolla et al., 2025; Hijab et al., 2023), technical barriers in implementing parental observations (Tsikinas and Xinogalos, 2020), and potential obstacles such as limited parental time, insufficient guidance from educators, or cultural biases.

Future directions emphasize collaborative relationships between teachers and parents. Encouraging parental participation, providing clear instructions, and adapting SGs to family-specific needs ensure relevance, cultural appropriateness, and developmental alignment. Co-design empowers families, enhances skill generalization, and strengthens the parent–child relationship. Moving forward, standardized, evidence-based co-design methodologies will be essential for creating inclusive, effective digital tools for children with ASD.

6 Conclusions and recommendations

Parental involvement in the learning process and the use of STEM, combined with the development of serious games, seem to offer positive results in the education of individuals with disabilities, specifically those with autism.

Parental involvement in designing serious games for children with ASD is not just desirable – it is fundamental, it is essential. It encourages personalized, effective, and emotionally attuned learning environments. Their active involvement enhances usability, promotes emotional safety, and allows the integration of real experiences into the playful learning process. The examples presented in the table demonstrate that parents are not simple users but co-creators.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

IC: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CKe: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LB: Data curation, Investigation, Software, Validation, Writing – original draft. AD: Data curation, Investigation, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing. CKa: Data curation, Investigation, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomp.2025.1693666/full#supplementary-material

References

Abd El-Sattar, H. K. H., Omar, M., and Mohamady, H. (2024). Developing a participatory research framework through serious games to promote learning for children with autism. Front. Educ. 9:1453327:1453327. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1453327

Amelia, R., Mustadi, A., Ghufron, A., and Suriansyah, A. (2023). Parental involvement in digital learning: mother’s experiences of elementary school students. Int. J. Interact. Mob. Technol. 17, 118–135. doi: 10.3991/ijim.v17i10.38253

Amevordzie, E.A. (2025). Inclusive co-design and co-creation: Enhancing inclusive design for learning practices through parental and student engagement.

Askari, S., Anaby, D., Bergthorson, M., Majnemer, A., Elsabbagh, M., and Zwaigenbaum, L. (2015). Participation of children and youth with autism spectrum disorder: a scoping review. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2, 103–114. doi: 10.1007/s40489-014-0040-7

Axelsson, M., Oliveira, R., Racca, M., and Kyrki, V. (2021). Social robot co-design canvases: a participatory design framework. ACM Trans. Hum. Robot Interact. 11, 1–39. doi: 10.1145/3472225

Azadboni, T. T., Nasiri, S., Khenarinezhad, S., and Sadoughi, F. (2024). Effectiveness of serious games in social skills training to autistic individuals: a systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 161:105634. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2024.105634

Bates, M. (2011). Student participation in serious games design. United Kingdom: Nottingham Trent University.

Beaumont, R., Walker, H., Weiss, J., and Sofronoff, K. (2021). Randomized controlled trial of a video gaming-based social skills program for children on the autism spectrum. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 51, 3637–3650. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04801-z,

Bourgonjon, J., Valcke, M., Soetaert, R., De Wever, B., and Schellens, T. (2011). Parental acceptance of digital game-based learning. Comput. Educ. 57, 1434–1444. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2010.12.012

Bravou, V., Oikonomidou, D., and Drigas, A. (2022). Applications of virtual reality for autism inclusion. A review (Aplicaciones de la realidad virtual Para la inclusión del autism. Una revisión). Retos 45, 779–785. doi: 10.47197/retos.v45i0.92078

Bustamante, A. S., Schlesinger, M., Begolli, K. N., Golinkoff, R. M., Shahidi, N., Zonji, S., et al. (2020). More than just a game: transforming social interaction and STEM play with Parkopolis. Dev. Psychol. 56, 1041–1056. doi: 10.1037/dev0000923,

Carlier, S., Van der Paelt, S., Ongenae, F., De Backere, F., and De Turck, F. (2020). Empowering children with ASD and their parents: design of a serious game for anxiety and stress reduction. Sensors 20:966. doi: 10.3390/s20040966,

Carneiro, T., Carvalho, A., Frota, S., and Filipe, M. G. (2024). Serious games for developing social skills in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. Healthcare (Basel) 12:508. doi: 10.3390/healthcare12050508

Chaidi, E., Kefalis, C., Papagerasimou, Y., and Drigas, A. (2021). Educational robotics in primary education. A case in Greece. Res. Soc. Dev. 10:e17110916371. doi: 10.33448/rsd-v10i9.16371

Chaidi, I., and Drigas, A. (2020). Parents’ involvement in the education of their children with autism: related research and its results. Int. J. Emerg. Technol. Learn. 15, 194–203. doi: 10.3991/ijet.v15i14.12509

Chaidi, I., Pergantis, P., Drigas, A., and Karagiannidis, C. (2024). Gaming platforms for people with ASD. J. Intelligence 12:122. doi: 10.3390/jintelligence12120122,

Chiu, M.-S., and Zhu, M. (2025). Parents’ perspectives on using virtual reality for learning mathematics: identifying factors for innovative technology acceptance. Educ. Inf. Technol. 30, 779–799. doi: 10.1007/s10639-024-12935-1

Clancy, K. M. (2017). Assessing parent involvement in applied behavior analysis treatment for children with autism. Detroit, Michigan: Wayne State University.

Cohrdes, C., Yenikent, S., Wu, J., Ghanem, B., Franco-Salvador, M., and Vogelgesang, F. (2021). Indications of depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany: comparison of national survey and twitter data. JMIR Ment Health. 8:e27140. doi: 10.2196/27140

de Carvalho, A. P., Braz, C. S., dos Santos, S. M., Ferreira, R. A. C., and Prates, R. O. (2024). Serious games for children with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic literature review. Int. J. Hum. Comput. Interact. 40, 3655–3682. doi: 10.1080/10447318.2023.2194051

El Shemy, I., Jaccheri, L., Giannakos, M., and Vulchanova, M. (2025). Participatory design of augmented reality games for word learning in autistic children: the parental perspective. Entertain. Comput. 52:100756. doi: 10.1016/j.entcom.2024.100756

El Shemy, I., Urrea Echeverria, A. L., Erena-Guardia, G., Saldaña, D., Vulchanova, M., and Giannakos, M. (2023). “Enhancing the vocabulary learning skills of autistic children using augmented reality: a participatory design perspective” in Proceedings of the 2023 symposium on learning, design and technology, 87–96.

Fan, X., and Chen, M. (2001). Parental involvement and students’ academic achievement: a meta-analysis. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 13, 1–22. doi: 10.1023/A:1009048817385

Ferdig, R. E., Amberg, H. G., Elder, J. H., Valcante, G., Donaldson, S. A., and Bendixen, R. (2009). Autism and family interventions through technology: a description of a web-based tool to educate fathers of children with autism. Int. J. Web-Based Learn. Teach. Technol. 4, 55–69. doi: 10.4018/jwbltt.2009090804

Fernández Cerero, J., Montenegro Rueda, M., and López Meneses, E. (2024). The impact of parental involvement on the educational development of students with autism spectrum disorder. Children 11:1062. doi: 10.3390/children11091062,

Fletcher-Watson, S., Petrou, A., Scott-Barrett, J., Dicks, P., Graham, C., O’Hare, A., et al. (2016). A trial of an iPadTM intervention targeting social communication skills in children with autism. Autism 20, 771–782. doi: 10.1177/1362361315605624

Gabrielli, S., Cristofolini, M., Dianti, M., Alvari, G., Vallefuoco, E., Bentenuto, A., et al. (2023). Co-design of a virtual reality multiplayer adventure game for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: mixed methods study. JMIR Serious Games 11:e51719. doi: 10.2196/51719,

Garriott, P. O., Flores, L. Y., Prabhakar, B., Mazzotta, E. C., Liskov, A. C., and Shapiro, J. E. (2014). Parental support and underrepresented students’ math/science interests: the mediating role of learning experiences. J. Career Assess. 22, 627–641. doi: 10.1177/1069072713514933

Goldman, S. E., and Burke, M. M. (2019). The perceptions of school involvement of parents of students with autism spectrum disorders: a systematic literature review. Rev. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 6, 109–127. doi: 10.1007/s40489-019-00157-y

Grossard, C., Grynspan, O., Serret, S., Jouen, A.-L., Bailly, K., and Cohen, D. (2017). Serious games to teach social interactions and emotions to individuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Comput. Educ. 113, 195–211. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2017.05.002

Gülhan, F. (2023). Parental involvement in STEM education: a systematic literature review. Eur. J. STEM Educ. 8:5. doi: 10.20897/ejsteme/13506

Hamidi, F., Baljko, M., and Gómez, I. (2017). “Using participatory design with proxies with children with limited communication” in Proceedings of the 19th international ACM SIGACCESS conference on computers and accessibility, Baltimore Maryland USA 250–259.

Hassan, A.O. 2021 Interactive vocabulary learning application for children with autism Spectrum disorder: A participatory design study (master’s thesis). Hamad Bin Khalifa University, Qatar.

Hidayat, I. K. (2022). Teachers’ and parents’ viewpoints of game-based learning: an exploratory study. KnE Soc. Sci. 2022, 77–84. doi: 10.18502/kss.v7i13.11647

Hijab, M. H. F., Banire, B., Neves, J., Qaraqe, M., Othman, A., and Al-Thani, D. (2023). Co-design of technology involving autistic children: a systematic literature review. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. doi: 10.1080/10447318.2023.2266248

Huijnen, C. A. G. J., Lexis, M. A. S., Jansens, R., and de Witte, L. P. (2017). How to implement robots in interventions for children with autism? A co-creation study involving people with autism, parents and professionals. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 47, 3079–3096. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3235-9,

Hu, Y., Peng, Y., Gohumpu, J., Zhuang, C., Malambo, L., and Zhao, C. (2025). Magicarpet: a parent-child interactive game platform to enhance connectivity between autistic children and their parents. ArXiv 250314127. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2503.14127

Indrajaya, M., Chao, W.-H., Semwaiko, G. S., Pusparani, Y., and Yang, C.-Y. (2024). Enhancing parent-child interaction through the gamification of parenting: an exploration of digital interventions. E-Learn. Digit. Media. doi: 10.1177/20427530241310505

Kalemkuş, F. (2025). Trends in instructional technologies used in education of people with special needs due to intellectual disability and autism. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 25, 237–261. doi: 10.1111/1471-3802.12723

Kangas, M., Koskinen, A., and Krokfors, L. (2016). A qualitative literature review of educational games in the classroom: the teacher’s pedagogical activities. Teach. Teach. 23, 451–470. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2016.1206523

Kefalis, C., Kontostavlou, E. Z., and Drigas, A. (2020). The effects of video games in memory and attention. Int. J. Eng. Pedagogy 10, 51–61. doi: 10.3991/ijep.v10i1.11290

Kefalis, C., Skordoulis, C., and Drigas, A. (2024). The role of 3D printing in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education in general and special schools. Int. J. Online Biomed. Eng. 20, 4–18. doi: 10.3991/ijoe.v20i12.48931

Kefalis, C., Skordoulis, C., and Drigas, A. (2025). Digital simulations in STEM education: insights from recent empirical studies, a systematic review. Encyclopedia 5:10. doi: 10.3390/encyclopedia5010010

Kurth, J. A., Love, H., and Pirtle, J. (2020). Parent perspectives of their involvement in IEP development for children with autism. Focus Autism Other Dev. Disabil. 35, 36–46. doi: 10.1177/1088357619842858

Lange, A. A., Brenneman, K., and Sareh, N. (2021). Using number games to support mathematical learning in preschool and home environments. Early Educ. Dev. 32, 459–479. doi: 10.1080/10409289.2020.1778386

LeMoine, J. (2022). XR in health and wellbeing: Establishing a new, Inclusivley designed participatory practice using augmented reality helpers to support teens and Young adults with autism Spectrum disorder to address life challenges.

Libbi, C.A. (2021). When life gives you lemons: Designing a game with and for autistic girls. (Master’s thesis, University of Twente)

Linder, S. M., and Emerson, A. (2019). Increasing family mathematics play interactions through a take-home math bag intervention. J. Res. Childhood Educ. 33, 323–344. doi: 10.1080/02568543.2019.1608335

Liu, L., Yao, X., Chen, J., Zhang, K., Liu, L., Wang, G., et al. (2024). Virtual reality utilized for safety skills training for autistic individuals: a review. Behav. Sci. 14:82. doi: 10.3390/bs14020082,

Magaña, S., Lopez, K., and Machalicek, W. (2017). Parents taking action: a psycho-educational intervention for Latino parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Fam. Process 56, 59–74. doi: 10.1111/famp.12169,

Mangram, C., and Solis Metz, M. T. (2018). Partnering for improved parent mathematics engagement. Sch. Community J. 28, 273–294. Available online at: http://www.schoolcommunitynetwork.org/SCJ.aspx

Müller, A., Bába, É. B., Židek, P., Lengyel, A., Lakó, J. H., Laoues-Czimbalmos, N., et al. (2024). The experiences of motor skill development in children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) reflected through parental responses. Children 11:1238. doi: 10.3390/children11101238,

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

Papadakis, S., Kalogiannakis, M., and Zaranis, N. (2018). Educational apps from the android Google play for Greek preschoolers: a systematic review. Comput. Educ. 116, 139–160. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2017.09.007

Poddar, R., Naik, T., Punnam, M., Chourasia, K., Pandurangan, R., Paali, R. S., et al. (2024). Experiences from running a voice-based education platform for children and teachers with visual impairments. ACM J. Comput. Sustain. Soc. 2, 1–35. doi: 10.1145/3677323

Qian, M., and Clark, K. R. (2016). Game-based learning and 21st century skills: a review of recent research. Comput. Hum. Behav. 63, 50–58. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2016.05.023

Ramani, G. B., and Siegler, R. S. (2008). Promoting broad and stable improvements in low‑income children’s numerical knowledge through playing number board games. Child Dev, 79, 375–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01131.x

Salvatierra, L., and Cabello, V. M. (2022). Starting at home: what does the literature indicate about parental involvement in early childhood STEM education? Educ. Sci. 12:218. doi: 10.3390/educsci12030218

Schenke, K., Redman, E. J., Chung, G. K., Chang, S. M., Feng, T., Parks, C. B., et al. (2020). Does “measure up!” measure up? Evaluation of an iPad app to teach preschoolers measurement concepts. Comput. Educ. 146:103749. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103749

Semwaiko, G. (2024). Enhancing parent-child interaction through the gamification of parenting: An exploration of digital interventions. E-Learning and Digital Media. 1–18.

Shivraj, P., Geller, L. K., Basaraba, D., Geller, J., Hatfield, C., and Näslund-Hadley, E. (2018). Developing and refining usable, accessible, and culturally relevant materials to maximize parent_child interactions in mathematics. Glob. Educ. Rev. 5, 82–105. Available online at: https://ger.mercy.edu/index.php/ger/article/view/433?utm_source=chatgpt.com

Solichah, N., Fardana, N. A., and Samian, S. (2025). Theoretical framework used in parental involvement research: a scoping review. Int. J. Eval. Res. Educ. 14:758. doi: 10.11591/ijere.v14i1.29392

Stasolla, F., Akbar, K., Passaro, A., Dragone, M., Di Gioia, M., and Zullo, A. (2024). Integrating reinforcement learning and serious games to support people with rare genetic diseases and neurodevelopmental disorders: outcomes on parents and caregivers. Front Psychol, 15, 1372769.

Stasolla, F., Curcio, E., Passaro, A., Di Gioia, M., Zullo, A., and Martini, E. (2025). Exploring the combination of serious games, social interactions, and virtual reality in adolescents with ASD: a scoping review. Technologies 13:76. doi: 10.3390/technologies13020076

Sýkora, T., Stárková, T., and Brom, C. (2021). Can narrative cutscenes improve home learning from a math game? An experimental study with children. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 52, 42–56. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12939

Tsikinas, S., and Xinogalos, S. (2020). Towards a serious games design framework for people with intellectual disability or autism spectrum disorder. Educ. Inf. Technol. 25, 3405–3423. doi: 10.1007/s10639-020-10124-4

Vacca, R. A., Augello, A., Gallo, L., Caggianese, G., Malizia, V., La Grutta, S., et al. (2023). Serious games in the new era of digital-health interventions: a narrative review of their therapeutic applications to manage neurobehavior in neurodevelopmental disorders. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 149:105156. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2023.105156,

Wang, C., Li, S., and Su, Y.-S. (2023). Impact of academic stress by parent-proxy on parents’ learning-support-services: a moderated-mediation model of health anxiety by parents’ educational level. Libr. Hi Tech 41, 192–209. doi: 10.1108/LHT-07-2022-0329

Young, J. M., Reed, K. E., Rosenberg, H., and Kook, J. F. (2023). Adding family math to the equation: promoting head start preschoolers’ mathematics learning at home and school. Early Child Res. Q. 63, 43–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2022.11.002

Yu, J., Granados, J., Hayden, R., and Roque, R. (2021). Parental facilitation of young children’s technology-based learning experiences from nondominant groups during the COVID-19 pandemic. Proc. ACM Hum. Comput. Interact. 5, 1–27. doi: 10.1145/3476048

Keywords: engaging parents, educating persons with impairments, STEM education, developing a serious game, people with ASD

Citation: Chaidi I, Kefalis C, Bakola LN, Drigas A and Karagiannidisn C (2025) STEM, serious games, and parental involvement in special education: a systematic review. Front. Comput. Sci. 7:1693666. doi: 10.3389/fcomp.2025.1693666

Edited by:

Andrej Košir, University of Ljubljana, SloveniaReviewed by:

Sodel Vazquez Reyes, Autonomous University of Zacatecas, MexicoFatih Kalemkuş, Kafkas University, Türkiye

Copyright © 2025 Chaidi, Kefalis, Bakola, Drigas and Karagiannidisn. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Irene Chaidi, aXJoYWlkaUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Irene Chaidi

Irene Chaidi Chrysovalantis Kefalis1,3

Chrysovalantis Kefalis1,3 Lizeta N. Bakola

Lizeta N. Bakola Athanasios Drigas

Athanasios Drigas Charalampos Karagiannidis

Charalampos Karagiannidis