- 1College of Computer Science and Technology, Huaqiao University, Xiamen, China

- 2School of Computer Science and Engineering, Changsha University, Changsha, China

Introduction: While Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) enhances language models, its application to long documents is often hampered by simplistic retrieval strategies that fail to capture hierarchical context. Although the RAPTOR framework addresses this through a recursive tree-structured approach, its effectiveness is constrained by semantic fragmentation from fixed-token chunking and a static clustering methodology that is suboptimal for organizing the hierarchy.

Methods: In this paper, we propose a comprehensive two-stage enhancement framework to address these limitations. We first employ Semantic Segmentation to generate coherent foundational leaf nodes, and subsequently introduce an Adaptive Graph Clustering (AGC) strategy. This strategy leverages the Leiden algorithm with a novel layer-aware dual-adaptive parameter mechanism to dynamically tailor clustering granularity.

Results: Extensive experiments on the narrative QuALITY benchmark and the scientific Qasper dataset demonstrate the robustness and domain generalization of our framework. Our full model achieves a peak accuracy of 65.5% on QuALITY and demonstrates superior semantic validity on Qasper, significantly outperforming the baseline. Comparative ablation studies further reveal that our graph-topological approach outperforms traditional distance-based, density-based, and distribution-based clustering methods. Additionally, our approach constructs a dramatically more compact hierarchy, reducing the number of required summary nodes by up to 76%.

Discussion: This work underscores the critical importance of a holistic, semantic-first approach to building more effective and efficient retrieval trees for complex RAG tasks.

1 Introduction

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) has emerged as a powerful paradigm for enhancing Large Language Models (LLMs) (Brown et al., 2020; Chowdhery et al., 2023) by providing them with external, up-to-date, and verifiable knowledge (Lewis et al., 2020). This approach mitigates issues of hallucination and allows LLMs to reason over information not present in their training data (Jiang et al., 2020). However, as the length and complexity of source documents increase, standard RAG systems face significant challenges (Barnett et al., 2024), primarily due to the fixed context window of LLMs and the difficulty of identifying relevant information scattered across long texts (Liu et al., 2024).

The RAPTOR framework (Sarthi et al., 2024) introduced an innovative solution to this problem by proposing a tree-structured, hierarchical approach to document representation. Through a recursive “embed-cluster-summarize” process, RAPTOR creates a multi-layered abstraction of the text, enabling efficient retrieval of information at varying levels of granularity, from specific details to high-level themes. This architecture has demonstrated significant potential for long-document question answering.

Despite its novel design, the effectiveness of the RAPTOR tree is contingent upon two fundamental stages, both of which present opportunities for significant improvement. The first is the leaf node generation. RAPTOR’s reliance on a fixed-token chunking strategy is oblivious to the semantic boundaries of the text, often resulting in the fragmentation of coherent logical units. This creates a weak and semantically disjointed foundation for the entire tree. The second limitation lies in the hierarchical clustering process itself. The use of conventional clustering algorithms, such as Gaussian Mixture Models (GMM), with static parameters is often suboptimal for the complex, non-spherical manifolds of text embeddings. A rigid clustering strategy struggles to adapt to the different levels of semantic abstraction required at different depths of the tree.

To address these dual limitations, we propose a comprehensive, two-stage enhancement framework for RAPTOR. First, we replace the fixed-token chunking with a semantic segmentation strategy, ensuring that the foundational leaf nodes are semantically coherent and self-contained. Second, we introduce a novel adaptive graph clustering methodology. This approach leverages the state-of-the-art Leiden algorithm for community detection and incorporates a layer-aware dual-adaptive parameter strategy, which dynamically adjusts the clustering granularity to match the level of abstraction at each layer of the tree.

The main contributions of this work are as follows:

• We introduce a holistic, two-stage enhancement framework that optimizes both the foundational leaf nodes and the internal hierarchical structure of the RAPTOR tree.

• We demonstrate that employing semantic segmentation for initial chunking provides a superior foundation, leading to significant performance improvements in downstream retrieval tasks.

• We design and implement an adaptive graph clustering algorithm that constructs a more compact, efficient, and semantically meaningful hierarchy, showing a strong synergistic effect when combined with high-quality leaf nodes.

• Through extensive experiments on both the narrative QuALITY benchmark and the scientific Qasper dataset, we validate the robustness and domain generalization of our framework. Our results show that the full model consistently outperforms the original RAPTOR baseline. Furthermore, a comparative ablation study against distance-based (Agglomerative) and density-based (HDBSCAN) clustering methods demonstrates the superior efficacy of our graph-topological approach in organizing complex semantic information.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related work in text chunking and clustering. Section 3 details our proposed two-stage methodology. Section 4 presents our experimental setup, results, and analysis. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper and discusses future work.

2 Background

2.1 The chunking challenges in RAG

The performance of RAG systems hinges on how documents are segmented into chunks. An effective strategy must balance two competing demands:

Relevance: Small chunks improve retrieval precision by reducing noise.

Contextual Integrity: Overly fine-grained chunks lose logical connections between paragraphs.

Existing methods attempt to address this trade-off with varying limitations. Fixed-size chunking simply splits text by token count, often breaking semantic units (Zhang et al., 2023). While recursive chunking relies on heuristic, rule-based delimiters like paragraphs or sentences, semantic chunking methods (Chen et al., 2024a) leverage embeddings to quantify coherence through cosine similarity, dynamically aligning chunks with topic boundaries.

Traditional semantic chunking methods mainly rely on lexical cohesion (Hearst, 1997) to detect discourse boundaries. However, these methods perform poorly on text paragraphs with rich lexical variations but consistent themes. With the development of deep learning, modern text segmentation techniques have generally shifted towards semantic representation methods based on pre-trained language models (PLMs). The core idea within this paradigm is to encode text units (such as sentences or paragraphs) into high dimensional dense embedding vectors (Karpukhin et al., 2020) through language models like BERT or Sentence-BERT (Reimers and Gurevych, 2019; Nair et al., 2023). These embedding vectors map the semantic content of the text to specific coordinates in the vector space, enabling semantic associations to be quantified through the geometric relationships between vectors. When quantifying the semantic coherence between adjacent text units, cosine similarity has become a de-facto standard metric. It measures the consistency in semantic direction between two embedding vectors by calculating the cosine of the angle between them. Its formal definition is as follows:

The key advantage of cosine similarity lies in its magnitude invariance. This means that it only focuses on the direction of vectors (i.e., the theme), while ignoring differences in vector magnitude caused by factors such as sentence length or lexical complexity. This makes it particularly robust when comparing texts with varying levels of detail but consistent themes.

Based on this, researchers typically use cosine distance, which is defined as

transforming the similarity problem into a distance metric. A smaller distance value indicates a high degree of semantic continuity. When the distance value exceeds a certain preset threshold or a local peak occurs, it is considered that semantic discontinuity has occurred. Based on this signal, the algorithm can infer the boundaries of paragraphs at the corresponding positions. Although other metrics such as Euclidean distance (L2 Norm) can also be used, due to their sensitivity to vector magnitude, they are not as widely applied in the field of text semantic analysis as cosine distance. This segmentation strategy based on semantic distance has become one of the mainstream techniques for text chunking in current long document understanding, information retrieval, and Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG) systems.

2.2 Clustering methods for text representation

Clustering is a fundamental unsupervised learning technique for organizing text documents by grouping semantically similar items (Aggarwal and Zhai, 2012). The choice of algorithm is crucial as it directly influences the quality of the resulting topical hierarchy.

A prevalent category of algorithms, including K-Means and Gaussian Mixture Models (GMMs), operates on geometric or distributional assumptions. These methods aim to partition the embedding space into clusters that are geometrically compact or fit a predefined probability distribution. However, they often presuppose convex or ellipsoidal cluster shapes, a constraint that is frequently violated by the complex, manifold-like structures of thematic groups in textual data (McInnes et al., 2018). Furthermore, their efficacy can be limited in the high-dimensional spaces of modern text embeddings, where geometric assumptions may not hold (Aggarwal et al., 2001; Aljaloud et al., 2024).

An alternative and more robust paradigm is graph-based clustering, often framed as community detection. Advanced topic modeling frameworks like BERTopic (Grootendorst, 2022) similarly leverage the rich representations from deep embeddings to uncover complex structures, moving beyond simple geometric assumptions. This approach models documents as nodes in a graph, with edge weights representing semantic similarity. The objective is to identify densely interconnected communities of nodes. This method is agnostic to cluster shape and is thus highly effective at uncovering complex thematic structures. The Leiden algorithm (Traag et al., 2019) represents the state-of-the-art in this domain, recognized for its efficiency and its ability to yield well-connected, high-quality communities, making it particularly suitable for discovering latent topics in large text corpora.

2.3 RAPTOR system

To address the challenge of long-document understanding, the RAPTOR system (Sarthi et al. 2024; Cao and Wang, 2022) introduces a tree-structured indexing approach. It hierarchically organizes information through a recursive “embed-cluster-summarize” process. The system first generates leaf nodes from initial text chunks, and then recursively groups them using clustering algorithms such as Gaussian Mixture Models (GMM). The nodes in each cluster are then summarized by a large language model to form a parent node at a higher level of abstraction (Gidi and Cohen, 2022). This architecture effectively creates a multi-layered semantic hierarchy, from fine-grained details to high-level themes.

While this framework is powerful, its performance is highly dependent on the quality of both its foundational leaf nodes and its structural integrity. This exposes two potential limitations. First, its reliance on a fixed-token chunking strategy can fragment semantically coherent text units, compromising the quality of the leaf nodes. Second, as discussed in Section 2.2, the use of a conventional, distribution-based clustering algorithm like GMM may not optimally capture the complex, non-spherical thematic structures often present in text embedding spaces.

These limitations in both the leaf node generation and the hierarchical clustering stages motivate our work. In this paper, we propose a two-stage enhancement to build more semantically robust and structurally sound retrieval trees.

3 An enhanced RAPTOR tree construction framework

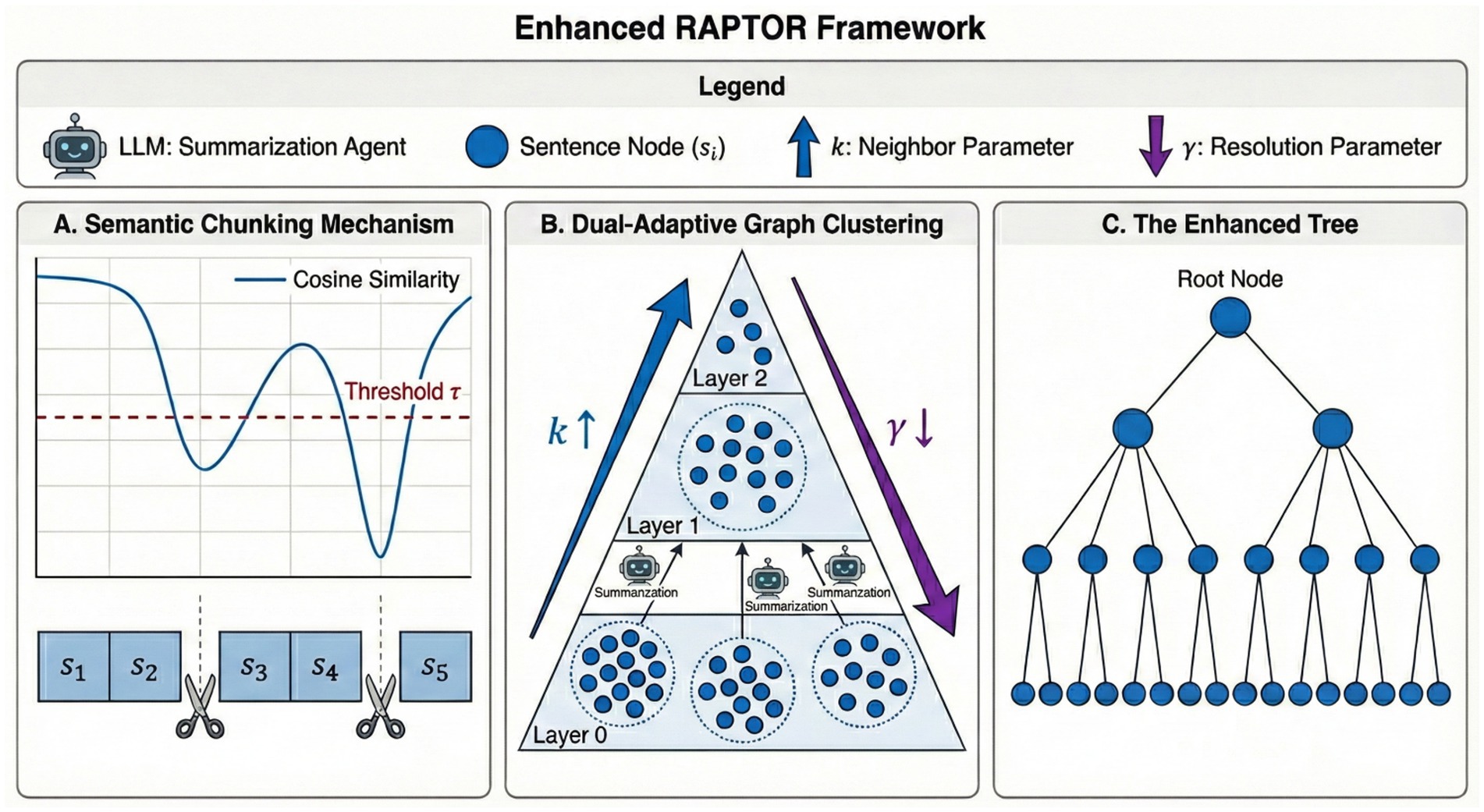

In this section, we present our two-stage framework for enhancing the RAPTOR tree construction process. Our approach is designed to build a more semantically robust and structurally coherent retrieval tree by optimizing both the foundational leaf node generation and the subsequent hierarchical clustering. Figure 1 illustrates the overall workflow of our proposed method.

Figure 1. The architecture of the enhanced RAPTOR framework. (A) Semantic chunking mechanism: illustrates the “Leaf Node Generation” stage using semantic segmentation. The system calculates the cosine similarity between adjacent sentence embeddings. A segmentation boundary (indicated by the scissor icons) is established only when the similarity drops below the predefined semantic threshold τ (e.g., 0.7). This dynamic strategy preserves “coherent logical units,” effectively preventing the “context fragmentation” often caused by fixed-token chunking. (B) Dual-adaptive graph clustering: depicts the construction of the hierarchical structure using the Leiden algorithm driven by a layer-aware dual-adaptive parameter strategy. As the hierarchy ascends from the bottom (Layer 0) to the top: 1. The neighbor parameter (k) increases linearly (blue arrow) to expand the topological receptive field and capture broader global relationships. 2. The resolution parameter ( ) decreases linearly (purple arrow) to coarsen granularity and encourage high-level thematic aggregation. Detected communities are summarized by an LLM Agent to form parent nodes for the subsequent layer. (C) The enhanced tree: shows the final “multi-layered semantic hierarchy.” This structure integrates the semantically robust leaf nodes from Panel A with the optimized topological clusters from Panel B, creating a compact and efficient index for top-down retrieval.

3.1 Leaf node generation via semantic segmentation

The structural integrity and retrieval accuracy of the entire RAPTOR tree are fundamentally dependent on the quality of its foundational leaf nodes. The original method employs a fixed-token chunking strategy (e.g., 100 tokens per chunk), which, while simple, is oblivious to the underlying semantic structure of the text. This can lead to the fragmentation of coherent logical units, severely impacting the performance of subsequent clustering, summarization, and retrieval tasks.

This limitation is starkly illustrated by an example from the QuALITY dataset, in the text “LOST IN TRANSLATION By LARRY M. HARRIS.” The fixed-token chunking method partitions a single, causally-linked conversation into three separate chunks (107, 108, and 109). This division severs the logical connection between the premises of the conversation and its conclusion. Consequently, a retrieval query is likely to fetch only the chunk containing the final conclusion (109), while missing the crucial context from the preceding chunks. This results in an incomplete and misleading context for the language model, leading directly to an incorrect answer for the associated question.

To overcome this critical issue, we propose a semantic segmentation strategy for initial node generation. Instead of relying on arbitrary token counts, this method identifies and preserves semantically coherent blocks of text. The core of this approach is to partition the document based on its intrinsic thematic shifts. The process first decomposes the input text into sentences and generates their corresponding vector embeddings. It then iteratively calculates the semantic distance between adjacent sentence embeddings to detect topic boundaries. A new chunk is formed whenever this distance exceeds a predefined threshold, τ, or a maximum token limit is reached.

When applied to the aforementioned example, our semantic segmentation method correctly groups the entire related conversation into a single, cohesive chunk. By preserving the logical integrity of the text, this approach provides the language model with the complete context necessary for accurate inference. As a result, our enhanced model successfully provides the correct answer to the question that the original RAPTOR failed. The detailed chunking results for this specific example, comparing both methods, can be found in Appendices A, B.

This semantic-first approach ensures that each leaf node represents a coherent and self-contained unit of information, providing a high-quality foundation for the subsequent clustering stage. The complete process is formalized in Algorithm 1.

3.2 Construction of the hierarchical structure

With a robust foundation of semantically coherent leaf nodes established in Stage 1, we proceed to construct the tree’s internal hierarchical structure. This stage introduces a novel methodology that replaces conventional clustering techniques with a more sophisticated and adaptive graph-based approach, designed to better capture the complex relational structure of textual data.

3.2.1 Graph-based clustering via community detection

Traditional clustering algorithms, such as GMM, operate under geometric or distributional assumptions that often fail to adequately model the complex, non-spherical manifolds where text embeddings reside. To overcome this, we reframe the clustering problem as a community detection task.

For any given layer of nodes, we first construct a k-Nearest Neighbor (k-NN) graph. In this structure, nodes represent text units (chunks or summaries), and edges signify the semantic proximity between them. The choice of cosine similarity as the edge weighting metric is deliberate. In high-dimensional embedding spaces, Euclidean distance becomes less discriminative due to the curse of dimensionality (Aggarwal et al., 2001) and is often sensitive to vector magnitude, which correlates with sentence length rather than meaning. In contrast, cosine similarity captures the directional alignment of semantic vectors. This ensures that our graph topology relies purely on thematic consistency independent of text length, providing a robust foundation for community detection.

We then employ the Leiden algorithm (Traag et al., 2019) to partition this graph. Unlike traditional methods, Leiden is agnostic to cluster shape and guarantees well-connected communities. Specifically, we utilize the RBConfigurationVertexPartition method, which optimizes a Potts model and allows for precise control over community density—a feature we exploit in our adaptive strategy. Each detected community is then treated as a single cluster, and its constituent nodes are summarized by a Large Language Model to form a parent node in the subsequent, higher layer of the tree.

3.2.2 Dual-adaptive strategy for multi-resolution clustering

A central innovation of our framework is the recognition that a single, static clustering granularity is suboptimal for a multi-layered hierarchy. We introduce a dual-adaptive strategy to dynamically adjust the resolution of the clustering process in correspondence with the level of semantic abstraction.

Our guiding hypothesis is that different layers of the tree demand different notions of semantic proximity. At lower layers, containing specific granular content, the system must prioritize local, strong connections to form tight thematic clusters. Conversely, at higher layers composed of abstract summaries, the system must expand its scope to identify broader, long-range relationships that connect disparate sub-topics into a cohesive whole.

To implement this multi-resolution clustering, we first dynamically adjust the number of neighbors, k, as a linear function of the tree’s layer depth (layer_id):

In this formulation, defines the initial fine-grained connectivity for the leaf layer, while controls the rate at which the topological search radius expands as the tree ascends. We employ this linear progression strategy as a heuristic to model the “Cone of Abstraction” inherent in document hierarchies. As the tree ascends, the semantic “field of view” required to aggregate sub-topics naturally widens. While more complex functions could be hypothesized, a linear increase represents the most parsimonious and robust assumption for general discourse structures, providing a stable expansion of the receptive field without introducing the overfitting risks associated with higher-order hyperparameters.

Complementing this topological adaptation, we simultaneously introduce a dynamic resolution parameter, γ, for the Leiden algorithm. While the k-value dictates the connectivity of the graph, γ controls the granularity of the community detection itself. We initialize γ at a higher value to strictly partition local details at the bottom and linearly decay it to encourage the merging of broader communities at higher levels.

This dual-adaptive mechanism ensures that the structural organization of the tree is contextually sensitive to the level of abstraction at each layer, resulting in a more logically sound and semantically meaningful hierarchy. Integrating the graph-based community detection detailed in Section 3.2.1 with the adaptive parameter strategy proposed above, we present the comprehensive workflow for our tree construction. This iterative process, which transforms semantic leaf nodes into a unified hierarchical structure, is formalized in Algorithm 2.

4 Experiments

4.1 Experimental setup

To rigorously evaluate the proposed framework’s performance and generalization capabilities, we conducted experiments across two distinct datasets representing different domains and task formats.

4.1.1 Datasets

QuALITY (Narrative Long-Context Understanding): We utilize the QuALITY dataset (Pang et al., 2022) as our primary benchmark for evaluating narrative comprehension. This dataset consists of long-form documents (average 5 k tokens) with complex, cross-paragraph questions requiring reasoning over disparate parts of the text. The task is formatted as multiple-choice question answering.

Qasper (Scientific Literature QA): To assess the model’s domain generalization and robustness in processing highly structured, logic-dense text, we extend our evaluation to the Qasper dataset (Dasigi et al., 2021). Qasper focuses on information-seeking questions over full-text computer science research papers. Unlike QuALITY, Qasper requires open-ended question answering, challenging the retrieval system to synthesize precise answers from technical content containing formulas, figures, and complex citations.

4.1.2 Evaluation metrics

Given the differing nature of the tasks, we employ task-specific metrics:

Accuracy (for QuALITY): Following standard benchmarks, we report Accuracy as the primary metric for the multiple-choice questions in QuALITY.

Lexical and Semantic Metrics (for Qasper): For the open-ended generation tasks in Qasper, we adopt a dual-faceted evaluation strategy:

• Lexical Overlap Metrics: We utilize Token F1 Score, ROUGE-1, and ROUGE-L to quantify the surface-level lexical match between the generated answers and the ground truth. ROUGE-1 assesses information coverage (unigram overlap), while ROUGE-L evaluates structural coherence (longest common subsequence).

• LLM Score (Semantic Evaluation): Recognizing that lexical overlap metrics may penalize semantically correct but phrased-differently answers, we introduce a model-based metric, LLM Score. We employ DeepSeek-V3 as an expert evaluator to rate the generated answer against the gold reference on a 5-point Likert scale (1: Bad to 5: Perfect). This metric specifically prioritizes information completeness and logical correctness over mere string matching. The specific evaluation prompt used is detailed in Appendix C.

4.1.3 Implementation details

Models: We utilize the BAAI/bge-m3 model (Chen et al., 2024b) for all text embeddings. The deepseek-v3-0324 model is accessed via its official API to perform both the summarization of clusters and the final question-answering tasks. The specific prompt templates used for these tasks are detailed in Appendix C.

Clustering Configuration: For the adaptive graph clustering stage, we employed the Leiden algorithm utilizing the RBConfigurationVertexPartition method to optimize the community structure. The graph construction relies on a k-Nearest Neighbor (k-NN) approach where edges are weighted by the cosine similarity between node embeddings. To implement our dual-adaptive parameter strategy, we configured the parameters as follows:

• Adaptive Neighbors (k): We set the initial neighbor count for the leaf layer, increasing by for each subsequent layer to expand the topological receptive field.

• Adaptive Resolution ( ): We initialized the resolution parameter at and linearly decayed it by per layer (minimum 0.1) to encourage broader semantic aggregation at higher levels.

• Constraints: To manage the context window limits of the summarization model, we imposed a strict maximum cluster size of 100 nodes. Any community exceeding this threshold was recursively re-clustered using the same adaptive logic.

To ensure reproducibility, we fixed the random seed to 224 for all sampling, clustering, and embedding processes.

4.1.4 Comparative configurations

We evaluate three distinct configurations to isolate the contributions of each component:

• Original RAPTOR (Baseline): Employs fixed-token chunking (100 tokens) and its default GMM-based clustering.

• RAPTOR + SC: Integrates our semantic chunking (SC) method. We test a range of semantic thresholds τ ∈ {0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8}.

• Our Full Model (RAPTOR + SC + AGC): Our complete model, combining semantic chunking with our adaptive graph clustering (AGC) algorithm, utilizing the dual-adaptive parameter settings described above. We also evaluate a variant (Fixed Chunking + AGC) on the Qasper dataset to verify the independent effectiveness of the graph clustering algorithm.

4.2 Performance on narrative long-context QA (QuALITY)

4.2.1 Impact of semantic segmentation

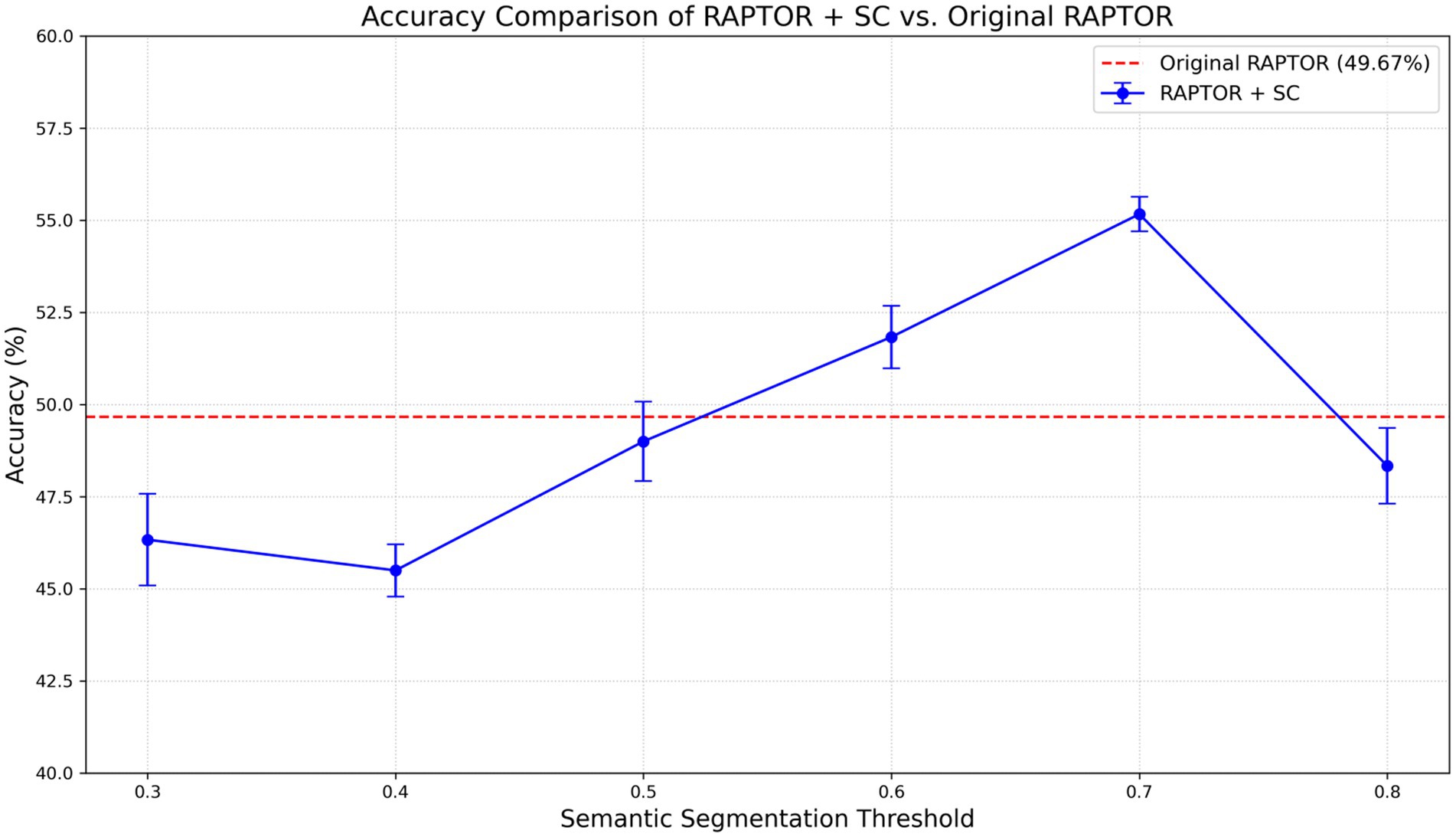

To isolate the effect of our first contribution, we first replace RAPTOR’s fixed-token chunking with our semantic segmentation approach. We conducted a parameter sweep across various semantic thresholds (τ) to identify the optimal configuration. The results are presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Model accuracy on the QuALITY dataset as a function of the semantic segmentation threshold. The dashed line represents the Original RAPTOR baseline.

The results illustrate a distinct non-monotonic relationship between model performance and the chosen semantic threshold. Accuracy improves steadily as τ increases from 0.3, peaking at τ = 0.7 with an accuracy of 55.17%, before declining at τ = 0.8. This peak represents a significant 5.5 percentage point improvement over the fixed-token baseline (49.67%).

The peak performance at τ = 0.7 suggests that this threshold represents an optimal equilibrium point between granularity and coherence:

• Below 0.7 (Over-segmentation): At lower thresholds (τ ≤ 0.6), the segmentation algorithm is overly sensitive to minor lexical changes. This triggers excessive splitting, shattering coherent logical units—such as a narrative event or a premise-conclusion pair—into disjoint fragments. This fragmentation forces the retrieval system to piece together scattered context, significantly increasing the risk of missing critical links required for complex reasoning.

• Above 0.7 (Semantic Drift): Conversely, at higher thresholds (e.g., τ = 0.8), the chunking becomes too lenient. The algorithm fails to detect subtle topic shifts, allowing distinct, unrelated themes to merge into noisy, multi-topical blocks. This semantic drift dilutes the specific embedding of the leaf node, making precise retrieval more difficult.

• Optimal (τ = 0.7): Therefore, τ = 0.7 appears to align most closely with the natural semantic pulse of human-written text. It effectively captures complete reasoning chains within a single node while maintaining thematic purity, providing a high-quality foundation for the subsequent clustering stage.

This analysis validates the general effectiveness of the semantic chunking approach and identifies as its optimal operating point. In the following section, we will evaluate our full model, which incorporates adaptive graph clustering, across this same range of thresholds to assess its cumulative impact and consistency.

4.2.2 Combined effect with adaptive graph clustering

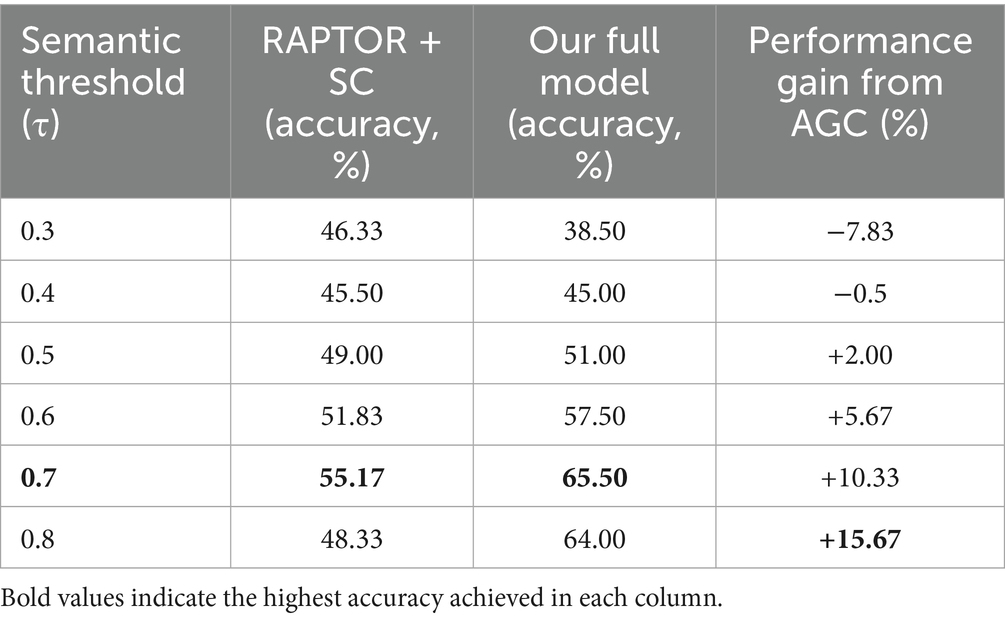

Having established the efficacy of semantic chunking, we now evaluate our full model, which integrates adaptive graph clustering (AGC) on top of this foundation. To provide a comprehensive comparison, we test both the RAPTOR + SC model and Our Full Model (RAPTOR + SC + AGC) across the full range of semantic thresholds. The results are presented in Table 1.

The results reveal several crucial insights:

Consistent Improvement in Optimal Range: When the semantic threshold is within a reasonable range (τ ≥ 0.5), our full model consistently outperforms the RAPTOR + SC model. This demonstrates that the adaptive graph clustering provides a significant performance enhancement when operating on a foundation of well-formed, coherent leaf nodes.

Peak Performance and Synergistic Effect: The performance of our full model also peaks at τ = 0.7, reaching a final accuracy of 65.5%. At this optimal operating point, the introduction of AGC yields an absolute performance gain of 10.33 percentage points over semantic chunking alone. This substantial improvement strongly suggests a synergistic effect: the adaptive graph clustering algorithm is able to fully capitalize on the high-quality semantic chunks, leading to a much more effective retrieval hierarchy than either enhancement could achieve in isolation.

Behavior at Extreme Thresholds: At lower thresholds (τ < 0.5), where semantic chunking leads to over-segmentation, the performance of the full model degrades. This is expected, as even a superior clustering algorithm cannot effectively group overly fragmented and context-poor leaf nodes. Interestingly, at a very high threshold (τ = 0.8), while the performance of RAPTOR + SC drops, our full model maintains a high accuracy. This suggests that the robust graph clustering mechanism may be more resilient to the noise introduced by slightly over-lenient chunking compared to the default GMM.

Overall, our complete model, integrating both enhancements, significantly outperforms the original RAPTOR baseline (49.67%) by a margin of 16.83 percentage points, confirming the substantial value of our two-stage optimization framework.

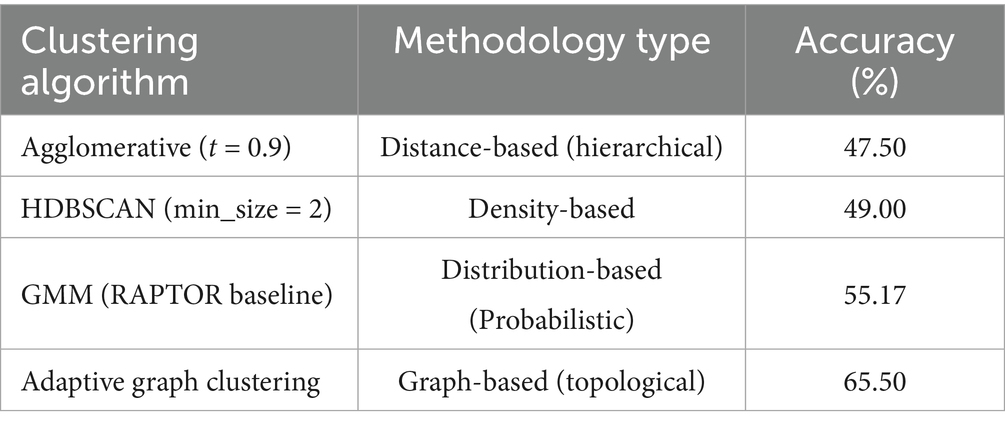

4.2.3 Impact of clustering strategy (ablation study)

To validate the necessity of our proposed Adaptive Graph Clustering (AGC), we conducted an ablation study comparing it against other prevalent clustering algorithms. To ensure a fair comparison, all methods were evaluated using the same high-quality leaf nodes generated by Semantic Chunking with the optimal threshold (τ = 0.7).

We compared the following clustering methodologies:

Agglomerative Clustering: A standard bottom-up hierarchical approach (distance threshold = 0.9).

HDBSCAN: A density-based algorithm (min_cluster_size = 2) known for handling noise.

Gaussian Mixture Models (GMM): The probabilistic clustering method used in the original RAPTOR framework.

Adaptive Graph Clustering (Ours): Our proposed graph-based community detection method.

The results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Accuracy comparison of different clustering algorithms on the QuALITY dataset (fixed semantic chunking τ = 0.7).

The substantial performance gap between the algorithms highlights the critical role of structural organization in hierarchical retrieval:

Failure of Distance and Density Metrics: Both Agglomerative Clustering (47.50%) and HDBSCAN (49.00%) underperformed significantly, falling below the GMM baseline. Agglomerative clustering suffers from the rigidity of fixed distance thresholds in high-dimensional embedding spaces. Similarly, HDBSCAN’s mechanism of classifying sparse data points as “noise” is detrimental in the RAG context, as outliers often contain unique, query-specific details that are essential for retrieval. Discarding them leads to information loss.

Limitations of Geometric Assumptions: While GMM (55.17%) performs respectably due to its soft-clustering nature, it is constrained by the assumption that semantic topics form spherical Gaussian distributions—a simplification that often fails to capture the complex, irregular manifold of natural language representations.

Superiority of Graph Topology: Our Adaptive Graph Clustering (65.50%) outperforms the next best method (GMM) by over 10 percentage points. This improvement stems from the method’s ability to model semantic relationships as a topological graph structure rather than geometric clusters. By leveraging the Leiden algorithm with our dual-adaptive strategy, it preserves the connectivity of the semantic manifold and ensures that every node is meaningfully integrated into the hierarchy, avoiding both the information loss of density methods and the rigid assumptions of geometric methods.

4.3 Generalization on scientific literature (Qasper)

To investigate the domain generalization capabilities of our framework, we extended our evaluation from the narrative texts of QuALITY to the highly technical and logic-dense scientific papers of the Qasper dataset. This experiment aims to verify whether our proposed enhancements—Semantic Chunking (SC) and Adaptive Graph Clustering (AGC)—maintain their effectiveness in retrieval scenarios that require synthesizing information from complex academic discourse.

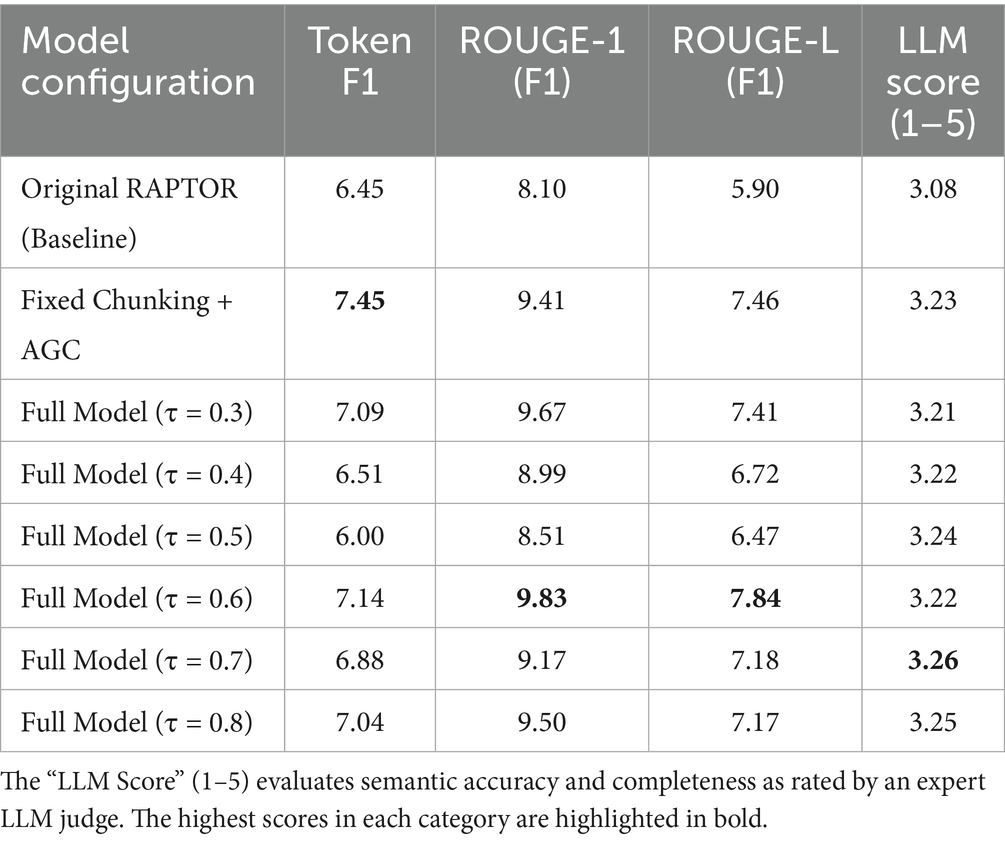

4.3.1 Performance comparison

We evaluated the Original RAPTOR baseline, an ablation model utilizing Fixed Chunking with AGC, and our Full Model across a range of semantic thresholds (τ). Table 3 presents the performance comparison using both lexical overlap metrics (Token F1, ROUGE) and the semantic-aware LLM Score.

4.3.2 Analysis of results

The experimental results on Qasper reveal three critical insights regarding the structural and semantic advantages of our framework:

Efficacy of Adaptive Graph Clustering: Comparing the Original RAPTOR baseline with the Fixed Chunking + AGC ablation model demonstrates the independent contribution of our clustering algorithm. Even without semantic segmentation, replacing GMM with Adaptive Graph Clustering significantly improves performance across all metrics, raising the LLM Score from 3.08 to 3.23 and Token F1 from 6.45 to 7.45%. This confirms that the graph-based hierarchical structure is intrinsically better suited for organizing the complex, non-spherical topic manifolds found in scientific literature, resulting in better information retrieval regardless of the chunking strategy.

Robustness of the Optimal Threshold (τ = 0.7): Consistent with our findings on the QuALITY dataset (Section 4.2), the Full Model achieves its highest semantic performance (LLM Score: 3.26) at a threshold of τ = 0.7. This recurrence suggests that τ = 0.7 represents a robust equilibrium point for text segmentation across different domains, effectively balancing the granularity required for detail retrieval with the coherence needed for logical reasoning.

Divergence between Lexical and Semantic Metrics: A notable observation in Table 2 is the divergence between exact-match metrics (Token F1, ROUGE) and the semantic LLM Score. While Fixed Chunking + AGC achieves the highest Token F1 (7.45%), it falls short in the LLM Score (3.23) compared to the Full Model at τ = 0.7 (3.26). This discrepancy highlights the limitation of N-gram overlap metrics in complex QA tasks. Fixed-token chunking often severs semantic dependencies (e.g., separating a hypothesis from its result), leading to retrieved contexts that contain correct keywords (high F1) but lack logical continuity. In contrast, our semantic segmentation ensures that retrieval units are self-contained logical blocks. Although this may result in slightly lower surface-level lexical overlap, it provides the generation model with a more coherent context, enabling it to synthesize answers that are semantically superior and more logically accurate, as reflected by the expert LLM evaluation.

In conclusion, the Qasper experiments validate the domain generalization of our framework. By prioritizing semantic integrity through segmentation and structural optimization through graph clustering, our model outperforms the baseline in generating high-quality, logic-driven answers for scientific queries.

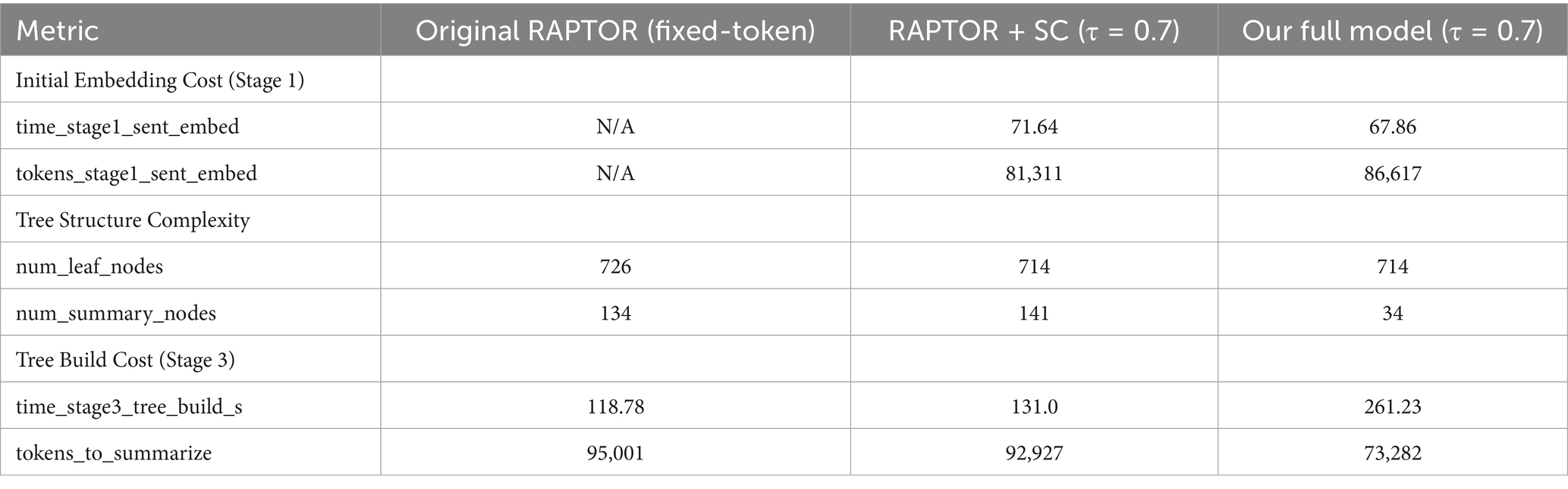

4.4 Computational cost analysis

To assess the practical implications of our proposed enhancements, we conducted a detailed analysis of the computational costs associated with the tree construction process. We logged time and token consumption across three different document lengths (~6 k, ~18 k, and ~65 k tokens) for both the RAPTOR + SC and our Full Model configurations. The key findings are summarized in Table 4, focusing on the most challenging ~65 k token document as a representative case.

Table 4. Computational cost comparison for a ~65 k token document at the optimal threshold (τ = 0.7) versus the fixed-token baseline.

Based on the empirical data and theoretical modeling, we analyze the cost-performance dynamics from three perspectives:

Empirical Cost Breakdown: The introduction of semantic chunking incurs an upfront computational cost (Stage 1), increasing the initial processing time from negligible in the baseline to approximately 68 s. This is due to the necessity of embedding all sentences to detect semantic boundaries. However, this investment yields a dramatic return in structural efficiency. The Adaptive Graph Clustering (AGC) constructs a significantly more compact hierarchy, requiring only 34 summary nodes compared to 141 in the baseline, a 76% reduction. Consequently, the token consumption for LLM summarization (Stage 3), which is typically the most expensive component of the RAPTOR tree construction, drops from 95,001 to 73,282 tokens.

Theoretical Complexity Analysis: To understand the scalability of our approach, we analyze the time complexity with respect to the document length N (in tokens). Let C denote the number of chunks, where .

• Embedding ( ): Our semantic segmentation requires passing the full text through the embedding model, introducing a linear complexity . This explains the upfront time cost observed.

• Clustering ( ): The graph construction involves a k-NN search, theoretically scaling as , followed by the Leiden algorithm with near-linear complexity . While appears computationally intensive, C represents chunks rather than tokens(e.g., C ≈ 700 for N = 65 k). Thus, the actual computation time is trivial compared to LLM inference.

• Summarization ( ): The dominant factor in total latency is the LLM summarization, scaling as , where is the total number of summary nodes. Our Dual-Adaptive strategy minimizes , effectively reducing the coefficient of the most expensive term in the total cost equation.

The Strategic Trade-off: Prioritizing Structure for Efficiency

While our Full Model incurs a higher upfront time cost due to semantic embedding and graph construction, this represents a deliberate optimization of the RAPTOR framework: allocating more resources to the low-latency structuring phase to improve the efficiency of the high-latency generation phase.

• Cost-Efficiency: By leveraging the Leiden algorithm to construct a denser hierarchy, we exchange a modest increase in CPU-based clustering time for a favorable reduction in API token consumption. This shift effectively lowers the computational burden on the most expensive component of the pipeline, the LLM summarization.

• Information Density: The enhanced clustering process serves to improve semantic coherence. Instead of summarizing text fragments that may be arbitrarily segmented, our method guides the LLM to process well-grouped, thematically related communities. This likely mitigates the propagation of noise and increases the informational value of each generated summary node.

• Performance ROI: Crucially, this investment in structural integrity translates into substantial retrieval improvements. The peak accuracy gain of 15.83% over the RAPTOR baseline suggests that a refined tree structure is highly beneficial for complex reasoning tasks, effectively justifying the additional preprocessing overhead.

5 Conclusion and future work

5.1 Conclusion

In this work, we enhanced the RAPTOR framework by addressing limitations in context fragmentation and hierarchical organization. We proposed a two-stage approach integrating Semantic Segmentation to preserve logical units and Adaptive Graph Clustering (AGC) to optimize tree topology.

Extensive evaluations on both the QuALITY (narrative) and Qasper (scientific) datasets demonstrate the robustness and generalization of our method.

Performance: Our model achieved a peak accuracy of 65.5% on QuALITY 1 and demonstrated superior semantic validity (LLM Score: 3.26) on the Qasper benchmark, consistently peaking at a semantic threshold of τ = 0.7.

Structural Efficacy: Ablation studies confirm that our graph-topological approach significantly outperforms traditional distance-based (Agglomerative), density-based (HDBSCAN), and distribution-based (GMM) clustering methods.

These results underscore the efficacy of a “semantic-first” strategy, proving that optimizing both foundational leaf nodes and structural organization yields a more coherent and efficient retrieval hierarchy for complex RAG tasks.

5.2 Future work

While our proposed framework has demonstrated significant improvements on both narrative and scientific datasets, the critical role of the clustering structure revealed in our experiments suggests several promising avenues for future research:

Optimization of Adaptive Parameter Strategies: Our ablation studies confirmed that the topological structure of the retrieval tree is a decisive factor in performance. Currently, our dual-adaptive strategy employs a heuristic linear function to adjust the neighbor count (k) and resolution ( ). Future work should investigate non-linear adaptation schemes (e.g., exponential or logarithmic scaling) to better model the “Cone of Abstraction.” Furthermore, we propose exploring data-driven adaptation, where clustering parameters are dynamically tuned based on the intrinsic density or manifold curvature of the specific document’s embeddings, rather than relying on fixed layer-based rules.

Automated Hyperparameter Tuning: Our experiments identified τ = 0.7 as a robust threshold across domains. However, manual grid search is inefficient for diverse real-world applications. Developing a lightweight, unsupervised metric to automatically estimate the optimal segmentation threshold (τ) and clustering density for unseen domains would be a significant advancement.

Scalability and Efficiency: Although effective, the exact k-NN graph construction in our approach incurs a computational cost of . Integrating Approximate Nearest Neighbor (ANN) algorithms, such as HNSW, could dramatically accelerate graph construction with negligible accuracy loss, making the framework scalable to massive corpora.

Impact of Embedding Manifolds: Since graph topology is derived from embedding similarities, the choice of the embedding model fundamentally dictates the cluster quality. Future research should systematically evaluate how different embedding architectures (e.g., dense vs. sparse, general vs. domain-specific) interact with our graph clustering algorithms to further optimize the semantic structure.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. The QuALITY dataset can be found at: https://github.com/nyu-mll/QuALITY. The Qasper dataset can be found at: https://allenai.org/data/qasper. The source code presented in this study is publicly available at: https://github.com/Xin5643/Graph-raptor.

Author contributions

YL: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Project administration. XX: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. XW: Software, Visualization, Writing – review & editing, Validation. YP: Writing – review & editing, Data curation, Formal analysis. CW: Funding acquisition, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study was supported by Fujian Province (2024HZ022013), Xiamen (XJK2025-1-2), and Quanzhou (2025QZNS001, 2023GZ5).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that Generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomp.2025.1710121/full#supplementary-material

References

Aggarwal, C. C., Hinneburg, A., and Keim, D. A. (2001). On the surprising behavior of distance metrics in high dimensional space. In Database Theory — ICDT 2001: 8th International Conference London, UK, January 4–6, 2001 Proceedings 8, pp. 420–434.

Aggarwal, C. C., and Zhai, C. (eds.) (2012). “A survey of text clustering algorithms” in Mining text data (Boston, MA: Springer), 77–128.

Aljaloud, A. S., Al-Dhelaan, A. M., and Al-Rodhaan, M. A. (2024). Deep clustering: a comprehensive survey. IEEE Trans. Neural Networks Learn. Syst. 36, 5858–5878. doi: 10.1109/TNNLS.2024.3403155

Barnett, S., Cohn, T., and Baldwin, T. (2024). Seven failure points when engineering a retrieval augmented generation system. arXiv:2401.05856 [cs.CL]. doi: 10.1145/3644815.3644945

Brown, T., Mann, B., Ryder, N., Subbiah, M., Kaplan, J. D., Dhariwal, P., et al. (2020). Language models are few-shot learners. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 1877–1901. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2005.14165

Cao, S., and Wang, L. (2022). HiBiRds: attention with hierarchical biases for structure-aware long document summarization. Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Dublin, Ireland, pp. 786–807.

Chen, J., Goldberg, Y., and Zbib, R. (2024a). From chunks to propositions: meaning-based content representation for RAG. arXiv:2405.02503 [cs.CL].

Chen, J., Xiao, S., Zhang, P., Luo, K., Lian, D., and Liu, Z. (2024b). BGE M3-embedding: multi-lingual, multi-functionality, multi-granularity text embeddings through self-knowledge distillation. arXiv:2402.03216 [cs.CL]. doi: 10.18653/v1/2024.findings-acl.137

Chowdhery, A., Narang, S., Devlin, J., Bosma, M., Mishra, G., Roberts, A., et al. (2023). PaLM: scaling language modeling with pathways. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 24, 1–113. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2204.02311

Dasigi, P., Lo, K., Beltagy, I., Cohan, A., Smith, N. A., and Gardner, M. (2021). A dataset of natural language queries, answers, and citations over NLP papers. Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Online, pp. 235–245.

Gidi, C., and Cohen, S. B. (2022). Query-focused abstractive summarization: a survey. Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, pp. 3236–3248.

Grootendorst, M. (2022). BERTopic: neural topic modeling with a class-based TF-IDF procedure. arXiv [Preprint]. arXiv:2203.05794. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2203.05794

Hearst, M. A. (1997). Texttiling: a quantitative approach to discourse segmentation. Comput. Linguist. 23, 33–73.

Jiang, Z., Xu, F. F., Araki, J., and Neubig, G. (2020). How can we know what language models know? Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 8, 423–438. doi: 10.1162/tacl_a_00324

Karpukhin, V., Oguz, B., Min, S., Lewis, P., Wu, L., Edunov, S., et al. (2020). Dense passage retrieval for open-domain question answering. Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pp. 6769–6781.

Lewis, P., Perez, E., Piktus, A., Petroni, F., Karpukhin, V., Goyal, N., et al. (2020). Retrieval-augmented generation for knowledge-intensive NLP tasks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 33, 9459–9474. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2005.11401

Liu, N. F., Lin, K., Hewitt, J., Paranjape, A., Bevilacqua, M., Petroni, F., et al. (2024). Lost in the middle: how language models use long contexts. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 12, 157–173. doi: 10.1162/tacl_a_00638,

McInnes, L., Healy, J., and Melville, J. (2018). UMAP: uniform manifold approximation and projection for dimension reduction. J. Open Source Softw. 3:861. doi: 10.21105/joss.00861

Nair, I., Garimella, A., Srinivasan, B. V., Modani, N., Chhaya, N., and Karanam, S. (2023). A neural CRF-based hierarchical approach for linear text segmentation. Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EACL 2023, Dubrovnik, Croatia, pp. 883–893.

Pang, R. Y., Parrish, A., Joshi, N., Nangia, N., Phang, J., Chen, A., et al. (2022). QuALITY: question answering with long input texts, yes! Proceedings of the 2022 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Seattle, WA, pp. 5336–5358.

Reimers, N., and Gurevych, I. (2019). Sentence-BERT: sentence embeddings using Siamese BERT networks. Proceedings of the 2019 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and the 9th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing, Hong Kong, China, pp. 3982–3992.

Sarthi, P., Abdullah, S., Tuli, A., Khanna, S., Goldie, A., and Manning, C. D. (2024). RAPTOR: recursive abstractive processing for tree-organized retrieval. Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, Vienna, Austria.

Traag, V. A., Waltman, L., and van Eck, N. J. (2019). From Louvain to Leiden: guaranteeing well-connected communities. Sci. Rep. 9:5233. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-41695-z,

Keywords: adaptive clustering, graph clustering, hierarchical retrieval, RAPTOR, retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), semantic segmentation

Citation: Liu Y, Xie X, Wan X, Pan Y and Wang C (2026) Enhancing RAPTOR with semantic chunking and adaptive graph clustering. Front. Comput. Sci. 7:1710121. doi: 10.3389/fcomp.2025.1710121

Edited by:

Marlon Santiago Viñán-Ludeña, Catholic University of the North, ChileReviewed by:

Esmaeil Narimissa, University of Liverpool, United KingdomZihan Wang, Helmholtz Association of German Research Centres (HZ), Germany

Copyright © 2026 Liu, Xie, Wan, Pan and Wang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaodong Xie, WGlhb2Rvbmd4aWVAaHF1LmVkdS5jbg==

Yan Liu1

Yan Liu1 Xiaodong Xie

Xiaodong Xie Xin Wan

Xin Wan Cheng Wang

Cheng Wang