- 1School of Health, Medicine and Applied Sciences, Central Queensland University, Cairns, QLD, Australia

- 2College of Medicine and Dentistry, James Cook University, Cairns, QLD, Australia

- 3School of Education and Professional Studies, Griffith University, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

- 4The Cairns Institute, James Cook University, Cairns, QLD, Australia

- 5Transition Support Service, Queensland Department of Education and Training, Parramatta State School, Cairns, QLD, Australia

- 6Apunipima Cape York Health Council, Cairns, QLD, Australia

Introduction: Education provides a key pathway to economic opportunities, health, and well-being. Yet, limited or no locally available secondary schooling in remote Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities requires more than 500 Indigenous students to transition to boarding schools. We report baseline quantitative data from the pilot phase (2016) of a 5-year study to explore a multicomponent mentoring approach to increase resilience and well-being for these students.

Materials and methods: An interrupted time series design is being applied to evaluate levels of change in Indigenous students’ resilience and well-being. Surveys were collaboratively developed, with questions adapted from the Child and Youth Resilience Measure (CYRM-28), Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K5), and questions which identified upstream risk factors for self-harm. They were completed by 94 students from five randomly selected schools (2 primary and 3 secondary) and one remote community.

Results: Pre-transition, most primary school students reported high levels of resilience, but only a third reported moderate–high levels of psychological well-being. Secondary students attending a boarding school reported lower scores on resilience and psychosocial well-being measures. Students who transitioned back to community after being from boarding school reported a lower sense of connection to peers and family, and they reported even lower resilience and psychosocial well-being scores.

Learning outcomes: Students have many strengths and can be adaptable, but their levels of resilience and psychosocial well-being are affected by the schooling transitions they are required to navigate. The findings are informing the development of intervention strategies to enhance student resilience and well-being.

Introduction

In Australia, as in other parts of the world, students from rural and remote communities have lower educational outcomes than their urban counterparts (Lamb et al., 2014). Education is a cornerstone of human development (UNESCO, 2016) and one of the most important mechanisms associated with economic opportunities, improved health, and well-being (Calma, 2008). Yet for the almost one quarter of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (hereafter respectfully, Indigenous) Queenslanders, who reside in remote or very remote communities (Office of Economic and Statistical Research, 2013), there is limited or no locally available secondary schooling. More than 500 Indigenous students from remote Cape York and Palm Island communities in Queensland, therefore, have to leave their community and country1 to attend boarding school for secondary education (Department of Education and Training, 2016; McCalman et al., 2016). These students are a subset of 4,000 Indigenous adolescents across Australia who attend boarding schools (Pearson, 2011; Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2013a,b).

Transition to Secondary Schools

Indigenous students who transition from remote community primary schools to mostly urban secondary boarding schools undergo major transitions in: where they live; how they live; the culture they live in (including language/s used); educational standards; roles, responsibilities, and expectations; parental influence; personal freedom; and relationships (Mellor and Corrigan, 2004; Benveniste et al., 2015; Mander et al., 2015a,b). While at boarding school, adolescent students undergo physiological changes, face increased peer pressure, and are potentially involved in risky health behaviors such as alcohol and drug consumption and sexual activity. Indigenous students can also be confronted with institutional discrimination and racism. Impacts on the mental health and well-being of Indigenous students include an increased risk of depression and other upstream factors that can increase risk of self-harm (Roeser et al., 2000; Mander et al., 2015c).

The Transition Support Services (TSS), Department of Education and Training, is a service of the Queensland Government. In response to concerns raised by parents in Cape York communities in 2004, a pilot transition service for Cape York Indigenous students was funded through a combination of State and Commonwealth resources (Indigenous Education and Training Futures, 2010). This service was expanded and now supports students and families from 12 Cape York communities and Palm Island to transition to boarding schools. TSS has approximately 20 staff who provide support across three service streams: primary into secondary school transition; secondary school transition; and re-engagement for students who are expelled (Department of Education and Training, 2016). TSS staff previously used a case management approach, based on a skilled helper mentoring model. Informed by research (2015–2016), the service is shifting to an ecological, resilience-focused approach (Kitchener and Jorm, 2008; Tsey et al., 2010; Ungar and Liebenberg, 2011; McCalman et al., 2016). In addition to working with students, TSS staff engage with families, boarding schools, and partner services to support students’ adjustment, orientation, and students’ ongoing stay at boarding school.

The Resilience Study

The 5-year Resilience Study was developed in partnership with TSS in response to identified self-harm and suicide risk for transitioning students (McCalman et al., 2016). It was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council from December 2014. Informed by the internationally significant work of Ungar (2008), the Resilience Study is investigating the impact of an enhanced multicomponent mentoring intervention to enhance psychosocial resilience of remote Indigenous students from Cape York and Palm Island who are compelled to relocate to boarding schools across Queensland. The underpinning definition of resilience is:

“In the context of exposure to significant adversity…. both the capacity of individuals to navigate their way to the psychological, social, cultural, and physical resources that sustain their well-being, and their capacity individually and collectively to negotiate for these resources to be provided in culturally meaningful ways” (Ungar, 2016).

In this paper, we report pilot data from a baseline survey of student resilience and risks to psychosocial well-being. These pilot data were collected from five schools and one remote community in 2016. These data inform researchers as how best to frame the development of a resilience-focused mentoring intervention for students. The survey will be readministered post-intervention with the pilot sample, and pre- and post-intervention with two additional clusters of students, to assess the impact of the enhanced intervention.

Materials and Methods

This paper reports pilot study results of the surveys facilitated with Indigenous boarding students. The aim was to co-generate an information base of resilience measures and upstream risk factors for boarding students. This baseline would inform TSS-led interventions and be used to monitor and assess the progress of an intervention and its effectiveness during implementation and after completion. The paper is thus the first of a larger set of papers, that once concluded, will describe the intervention and its effects.

The Researchers: Who Are We?

Our research team is led by a Gungarri Aboriginal woman from South Western Queensland. The remaining team members comprise non-Indigenous researcher allies, committed to supporting Indigenous and decolonizing approaches to research. Consistent with the resilience focus of the study, we report findings as positive, rather than deficit-focused indicators. Walter (2016) p 80 challenge researchers to reverse the “analytical lens to generate data conceptualized through an Indigenous methodological framework.” By changing the way we re-port and re-present data, we seek to challenge the “deficit data/problematic people” and reframe the data to enable new ways of understanding Indigenous health and well-being (Lovett and Walter, 2016; Walter, 2016).

Settings: Where Students Come From?

Participants from 11 Cape York communities and Palm Island, QLD, Australia, participated in a survey to assess their psychosocial resilience, risk for self-harm and service use. Cape York is a remote northern region of Queensland; 51% (8,566) of residents are Indigenous (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2012). These communities were formed from the late 1800s to early 1900s as result of the removal and relocation of Indigenous people to mission settlements. Each community has a distinctive history, tribal population groups, and church influence. Many Indigenous residents experience socioeconomic disadvantage, with low levels of skilled occupations, high rates of unemployment and low incomes. Primary schools exist in communities, but there is limited or no secondary schooling provision.

Palm Island, located 65 km North West of Townsville, was established as a settlement for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people from over 40 different language groups. These people were forcibly removed and relocated from all around Queensland as a result of colonial social policies (Watson, 1994). Inhabited by Manbarra people pre-European contact (Palm Island Aboriginal Shire Council, 2016), Palm Island Aboriginal people now identify as Bwgcolman (Geia, 2012), meaning “all the tribes in one” (Garond, 2014). Palm Island has two primary schools and one state high school.

Where Students Go to Secondary School?

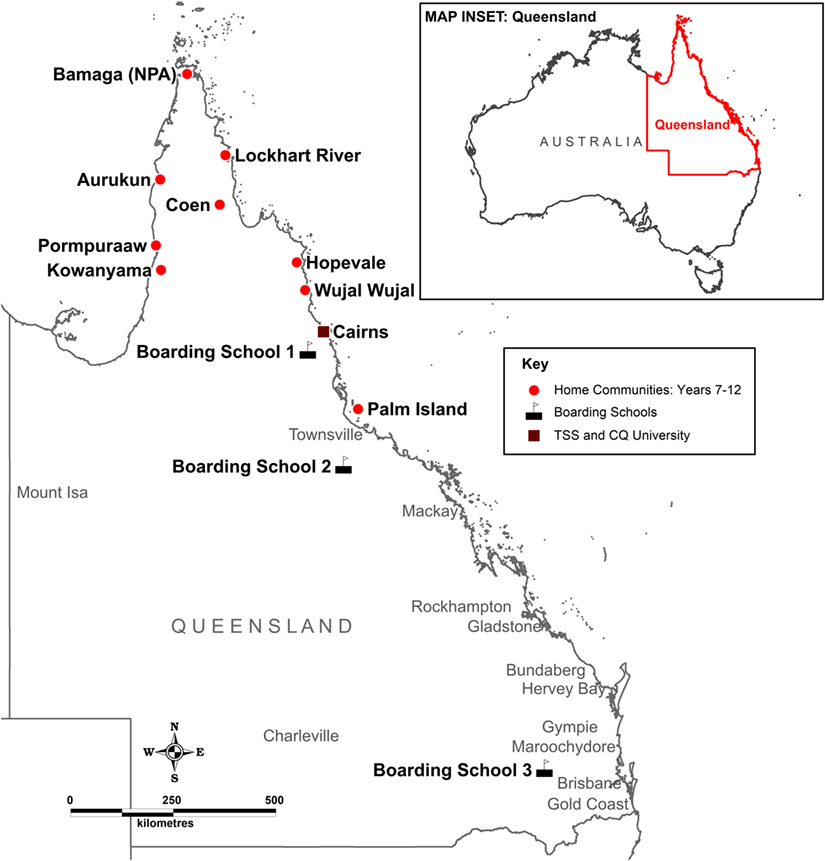

TSS supports students (and their families) in the transition to more than 30 destination boarding schools across Queensland, from Weipa in the north to Brisbane in the south. These schools are predominately based in urban areas. Destination boarding schools are run by Cape York Academy, Christian churches, and Queensland Education.

Study Participants

School students were surveyed at three points in their education journey: (i) primary school grade 6 students who were preparing to transition to secondary schools; (ii) current secondary school students in boarding facilities; and (iii) secondary school students who had been de-enrolled from boarding schools but were being supported by TSS to reengage. Characteristics of the students are summarized in Table 1. Secondary students were selected based on their enrollment at randomly selected schools. Criteria for participating boarding schools included (1) having at least 10 TSS-supported students enrolled and (2) being representative of the three TSS regions (far northern, northern, and southern Queensland). Two primary feeder schools and one community in which a TSS officer worked with students who were de-enrolled were also randomly selected (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Map of students’ home communities and destination boarding schools (Kelly, 2016).

The five school principals were then approached and all agreed that their schools could participate in the study. Parental consent for all students participating in the study was gained. Students were asked for their consent at the start of the survey.

The Survey Instruments

The survey was developed collaboratively with TSS and piloted with students, using questions drawn from two validated scales—the Child and Youth Resilience Measure (CYRM-28) (Ungar and Liebenberg, 2011) and the Kessler 5 (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2009). In addition, three “upstream” risk questions for self-harm were asked of students (McCalman et al., submitted).2 The CYRM-28 is based on three dimensions of resilience (individual, caregivers and context) and has been tested internationally with low-risk and complex high-risk youth (Ungar and Liebenberg, 2011). Minor adaptions in wording and the assessment response scales were undertaken to reflect the lived experience of students. Secondary school students responded on a standard 1–5 scale, ranging from: 1 (none of the time) to 5 (all of the time).

Primary school and re-engaged students responded on 3-point scales: for the primary from 1 (no); 2 (sometimes); and 3 (yes) and for the re-engaged group, 1 (none of the time); 2 (some of the time); and 3 (all of the time). Students were also asked three questions that could indicate upstream risk factors for self-harm: (1) I know someone close to me who died in the last year; (2) I know someone who committed suicide in the last year; (3) I had problems with the Police or court or had legal issues in the last year. Response options were yes or no. Finally, as used in previous Indigenous health studies, questions from the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K5) were included to assess students’ levels of psychosocial distress (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2009). Kessler scores were based on five statements relating to being without hope, restlessness, nervousness, everything being an effort and sadness. Response options ranged from (1) none of the time to (5) all of the time for all students. Total possible scores were between 5 and 25.

Data Collection and Cleaning

Based on the availability of internet and iPads at each site, data were collected either electronically using SurveyMonkey, QuickTap (a plug-in application that enables published SurveyMonkey surveys to be administered offline) on iPads (n = 80), or a hard copy (n = 14). TSS staff facilitated administration of the surveys in partnership with a university researcher. The majority of the students completed the survey independently, although some younger students in year 6 and/or those who had lower levels of literacy, completed the surveys in a group. This meant the TSS worker would read out the questions and wait for students to make an individual response before moving onto the next question. Data were downloaded directly into Microsoft Excel from both electronic instruments and, for the hard copy surveys, entered manually. Data entered manually were reviewed by a second researcher for systematic errors by comparing the data in the Excel file to the hard copies of surveys. Every fourth entry in the spreadsheet was checked with the corresponding paper survey. No systematic errors were identified.

Data Analysis

The Excel file was then exported into SPSS (v23) for analysis. The analysis was exploratory and descriptive. We summarized and compared responses from the three groups with regard to their background characteristics and views about their home and community, where relevant, experiences at boarding school and their reporting on risk and resilience items. K5 scores were calculated for each respondent by summing items. Respondents were rated against recognized levels of low to moderate (5–11) and high to very high levels of psychological distress (12–25) (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2013a,b). Given the high numbers in the high to very high range, these ratings were further separated into high (12–16) and very high (17–25). No further statistical analysis was undertaken for this initial descriptive baseline presentation of data.

Ethics Approvals

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from James Cook University Human Research Ethics Committee (H5964), Central Queensland University Research Ethics Committee (H16/01-008), Department of Education, and Training, Queensland Government (File No. 50/27/1646). This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of these Ethics Committees.

Results

Student responses are presented to evidence (1) students’ pre-transition resilience and risk at primary schools in their home communities; (2) the transition experiences of resilience and risk for secondary school students’ at boarding schools; and (3) students’ transition resilience and risk for those returning to community after they have been excluded from boarding school. Reported are primary, secondary and re-engaging students’ demographics; responses to questions from CYRM-28; views on school and boarding; risk factors; and measures of psychological distress, including responses to Kessler 5 questions.

Demographics

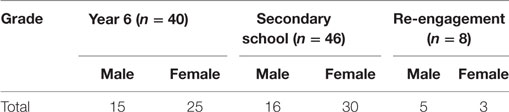

Initial baseline responses were provided by 94 primary, secondary, and re-engaging students from six sites (5 schools and 1 community). Over 60% of the group were female (Table 2), with a range of ages from 11 to 18 years, and current grades from 6 to 12.

The number and spread of males and female secondary students was different across the primary and secondary schools, with more females in the primary and secondary cohorts, and less females than males in the re-engaging group.

Primary Students

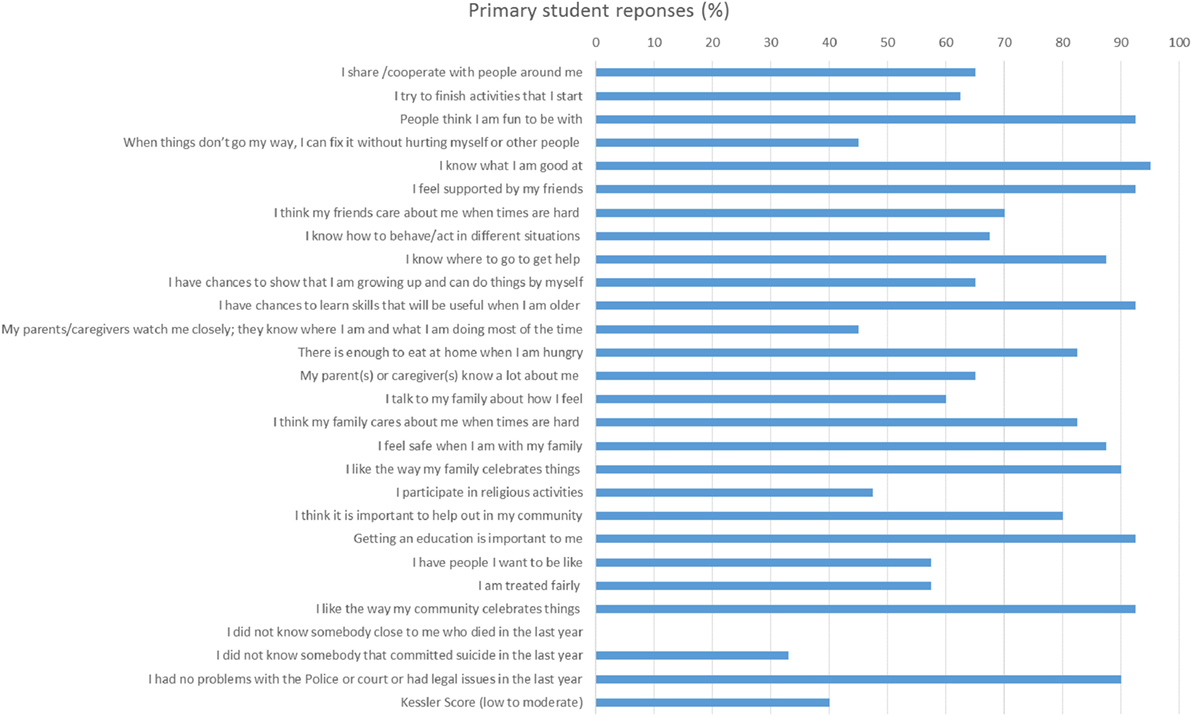

Figure 2 reports responses from primary students for the CYRM-28 questions, along with a number of additional items of interest to TSS staff included in the survey, Kessler 5 scores (low-moderate) and questions relating to upstream risk factors.

Prior to transitioning from primary to secondary boarding school, primary students said their family cares for them when times are hard (82.5%), they feel safe with their family (87.5%); they like the way community celebrates events (92.5%); and they know their language, totem, clan group, or traditional country (80.0%). These results reflect strong positive feelings about family and community. Primary students, however, reported limited role models in their community, with only 30% saying they had people they wanted to be like, and only 55% reporting that they could fix a problem without hurting themselves or someone else. Before leaving community, 40% of primary students reported low-moderate categories of psychological distress. All primary students reported that they knew a person close to them who had died in the last year and more than three quarters (77.5%) reported knowing someone who had suicided in the last year.

Secondary Students

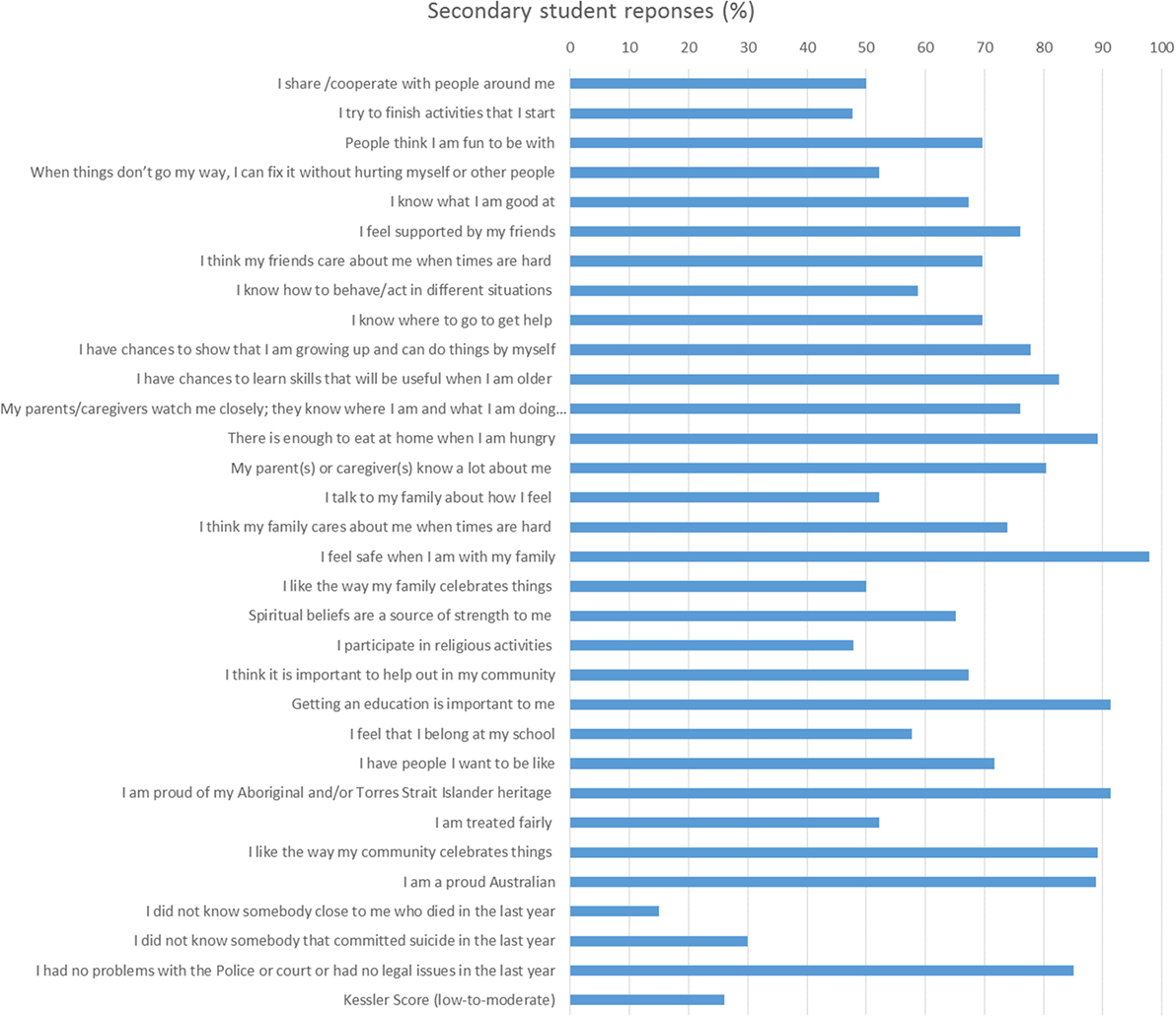

Figure 3 reports responses from students who have transitioned from primary to secondary school by the CYRM-28 questions, Kessler 5 scores (low-moderate) and risk factors.

Once students had transitioned from primary to secondary school, there were some notable changes in their responses to CYRM-28, psychological distress and risk questions. Although secondary students continued to be proud of their Indigenous heritage (88.9%), and felt like family cared for them when times are hard (74%), only half of the students reported feeling they were treated fairly (52.2%), and that their family knew a lot about them (52.2%). Consistent with primary school students, half of the boarding school students (52.2%) reported being able to fix things without hurting themselves or others when things did not go their way. One quarter (26%) reported low-moderate psychological distress (down by 15% compared to the primary school students). Most of the secondary students (85%) reported that they knew a person close to them who had died in the last year and 70% reported knowing someone who had suicided in the last year. The majority of students had no problems with the Police or court or had no legal issues in the last year (85%).

Re-Engaging Students

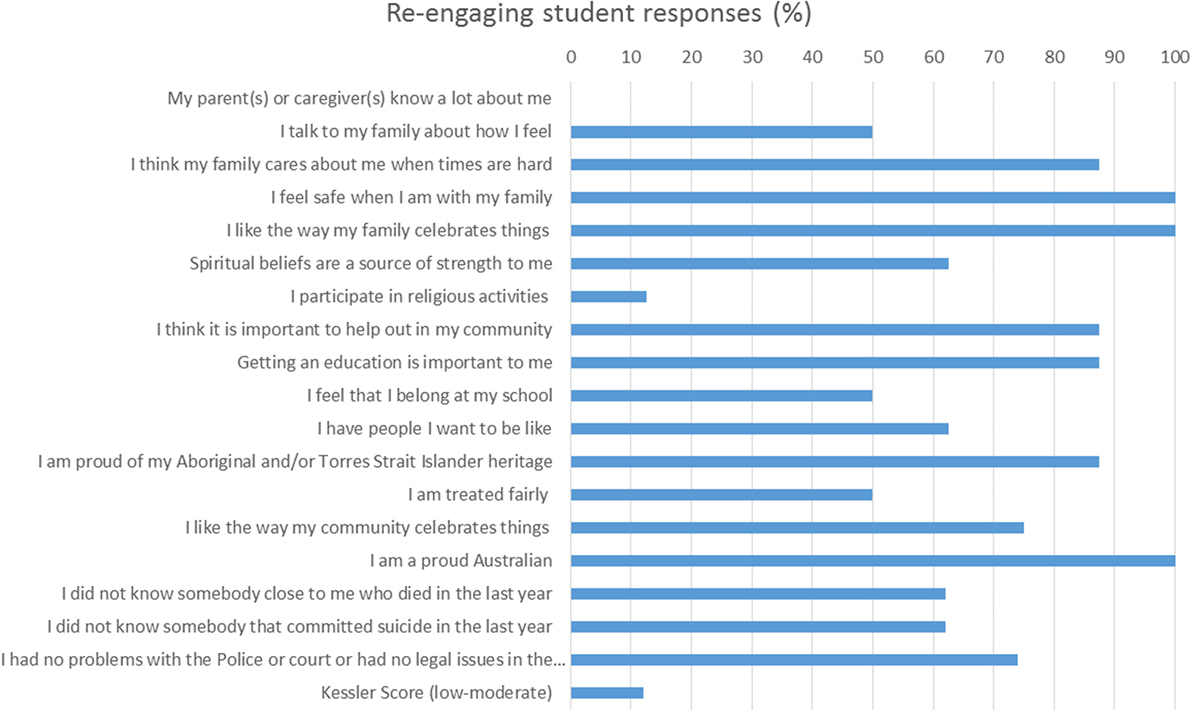

Figure 4 depicts the survey responses from re-engaging students who have transitioned from primary to secondary school and then back to their home community following exclusion from boarding school.

The re-engaging students who participated in this pilot phase reported feeling safe with family (100%) and that family cares about them when times are hard (87.5%). Only one quarter (25%) of the re-engaging students reported being able to fix things without hurting themselves or others when things did not go their way. All of the re-engaging students reported that their parents/caregivers did not know a lot about them (e.g., like what I like to do) (100%). Only 12.5% were in the low to moderate categories of psychological distress; the majority (87.5%) reporting high levels of distress. Of this cohort of students, two-thirds (62.5%) did not have someone close to them who had died or had suicided in the last year. Three quarters (75%) had no problems with the Police or court or legal issues in the last year. The re-engaging students’ scores suggest these students are at greater risk of psychological distress, given their responses in the survey.

A Comparison

Psychological Well-being, Including Kessler Psychological Distress Scale Scores

There were very similar response patterns from the three groups of students to many of the caregiver subscale of the resilience questions, including: enough to eat at home (83% or above); my family cares about me when times are hard (74% and above); I feel safe when with my family (88% and above); I like the way my family celebrates (90% and above). All of these measures seem to reflect strong positive feelings about family and community.

With regard to the individual subscale, primary and secondary students those who reported strong personal skills, also reported strong confidence in friends support, even in times of need (70%). There were consistently strong responses among all students regarding the importance of getting an education (primary 92.5%; secondary 91.3%; re-engaging 87.5%) and pride in their Indigeneity (secondary 91.3%; re-engaging 87.5%). Students reported they like the way their community and school celebrate important events, such as Sorry Day or National Aboriginal and Islander Day Observance Committee week. Almost two-thirds of secondary and re-engaging students reported spiritual beliefs were a source of strength (secondary 65.3%; re-engaging 62.5%). When asked if they were treated fairly, 57.5% of primary students, just over one half (52.2%) of secondary students and one half (50%) of re-engaging students reported being treated fairly. Responses regarding respect for and from teachers and boarding staff were relatively consistent between the secondary boarding and re-engaging students of around 70% agreement to each item.

There were also some differences between the three groups experiencing transition. Primary students could identify where in the community to gain help (87.5%), but fewer secondary students knew where to seek help (69.6%). When asked if people thought they were fun to be with, 92.5% of primary students and 69.6% of secondary students agreed, but only one half of re-engaging students had this perception (50%). Almost all (92.5%) of primary students and three quarters (76.1%) of secondary students felt supported by their friends but only 37.5% re-engaging students indicated friends would stand by them when things were difficult. In addition, re-engaging students reported that they felt their family did not knew them well (100%). 40% of current secondary and 25% of re-engaging students found it hard to keep up with school work. There was a moderate response regarding participation in religious activities from current students (47.5% and 47.8% from primary and secondary school students), with a response of only 12.5% from re-engaging students. Secondary students currently in boarding school indicated a positive response to school celebrations (87%), although only a third (37.5%) of re-engaging students agreed with this statement, perhaps related to their exclusions from school.

A few extra questions were asked of students, additional to the CYRM-28, K5, and risk questions. These included questions about feeling safe at school and in boarding (for secondary students). The responses were potentially concerning, are the two items that address perceived safety. Current students expressed a feeling of safety of 78.3% for both school and the boarding house. However, these assessments were lower for those re-engaging with boarding schools, with 62.5% of this group feeling safe at school and 75% in the boarding house. Students should be feeling high levels of safety in these environments, and these findings indicate a need for further exploration to understand what type of issues are of concern.

Discussion

Attaining an education contributes to greater economic opportunities, and improved health and well-being (Calma, 2008). For Indigenous students, gaining an education is more difficult because they are separated from their traditional country, from family and community support and are immersed in new cultural and social expectations. Positive family connections are a critical protective factor for successful transitions to adulthood (Boden et al., 2016). The data reported in this paper show that the resilience measures, along with psychological and well-being indicators are affected by the transitions students navigate.

Resilience is defined as how well one can “navigate their way to the psychological, social, cultural, and physical resources that sustain their well-being, and their capacity individually and collectively to negotiate for these resources to be provided in culturally meaningful ways” (Ungar, 2008, p. 225). The pilot data show that Indigenous students have many strengths such as pride in their identity as an Indigenous young person and strong connection to family which they draw upon as they transition from primary schools in their home communities into secondary boarding schools. As reported elsewhere, Indigenous students can be adaptable, despite the transitions undertaken and the relatively high psychosocial distress and exposure to risk factors (McNamara et al., 2014).

As evidenced by the data, transitioning from primary to secondary school is challenging. There is a need for schools and communities to support primary students to develop coping strategies prior to the transition from primary to secondary boarding school (Stewart and Lewthwaite, 2015). Informed by an ecological and culturally sensitive understanding of resilience, any interventions need to support the development of individual skills (personal, peer, and social skills) and the students’ relationship with the primary caregiver/s and their place in their context—spiritual, education, and cultural (Ungar et al., 2007; Ungar, 2008).

Primary and secondary students require intervention activities for that will assist them to respond when things go wrong without causing harm to themselves or others and that will enhance peer and educational connections. That some secondary students reported feeling they were unfairly treated at school suggests this needs to be explored further. We do not know how much of this issue of safety is related to the students’ experiences of formal schooling, living in a boarding facility or because of cultural differences between boarding staff and the Indigenous students.

Students re-engaging with the education system after exclusion from boarding schools, in particular, face many challenges. Only a third of re-engagement students reported trying to finish activities they started. This is a group of students that reported their family did not know much about them, and they were less likely to feel socially connected to their peers. Family and community connections are a key contributor to student resilience (Boden et al., 2016). More re-engaging students had been in contact with the police, or had legal issues. These results are not surprising given that these students have not had obvious success in the education system. This group of re-engaging students requires greater, targeted strategies to create an environment that enables them to re-adjust to any new boarding school and community, or alternative schooling options. As a result of preliminary data being reported from this study, students from boarding schools and in their communities in Cape York will now be referred to a local Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service for specialist support (Wenitong, personal communication).3

Psychological distress among and between the student groups supported by TSS is higher than reported by students in the general population. McNamara et al. (2014) in a report about older Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians found that 20.9% of all participants experienced high to very high levels of stress, with the proportion experiencing high to very high levels far higher in the Aboriginal than non-Aboriginal group (21% to 7%). In comparison, we found that 72.9% of Indigenous primary and secondary students reported high to very high levels of psychological distress. High exposure to risk factors such as someone close to the student dying, the student knowing someone who has suicided, and in particular for the re-engaging students, having contact with the police or juvenile justice system in the last year points to high levels of psychological distress and upstream risk factors for self-harm.

Limitations

We were unable to administer the Kessler questions with one primary school, due to a technical error. However, the practical survey administration experiences have provided useful information for the next round of post-intervention surveys. Different question scales were used depending if the students were in primary or secondary school. The primary students used a 3-point rating scale while the secondary students used a 5-point scale, following advice from TSS about the impact of age and/or cognitive capacity to differentiate points on a scale. This has reduced comparability of data across student groups.

A further limitation of survey data is the interpretation required to extricate the extent of social desirability bias. There are some reciprocal values, such as plenty to eat at home and feeling safe with family. Given the historical colonial context of families being punished or separated because of these types of indicators, it might be important for students to report the family as strong and “okay.” Data reported are sourced from survey data, and different students could interpret these questions from different perspectives. The planned intervention activities with boarding students, and qualitative component of the study will assist to contextualize these responses and may provide some insights as to the motivation for student responses.

Despite randomization of the participating schools and community, the low numbers of students, particularly in the third re-engagement group of post-secondary school students (n = 8), means that we cannot confidently assume that these students are representative of the entire student population. This paper reports pilot baseline data from a multiple baseline study that will survey students from a further 14 boarding schools and additional communities over three further years. These results provide a flag for further exploratory research using qualitative and quantitative methods.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the pilot baseline data show that students have many strengths and can be adaptable. However, the study also shows a need to create supportive environments that will enhance the likelihood of increased resilience of students, in partnership with schools and boarding facilities, students’ families, and communities. The data from this Resilience study provide evidence that informs a resilience-based mentoring intervention. Acknowledging student strengths is key to enhancing resilience and getting the interventions activities right (Mander and Fieldhouse, 2009), along with identifying and addressing upstream risk factors for self-harm.

The context in which the students go into, or live in, is critical. Beyond the scope of interventions planned for the purposes of this study, there would be benefit in embedding activities that promote the resilience of primary students and their families in the years prior to them leaving their community. There is a role for targeted activities that connect boarding facilities and schools with communities and parents to create a more supportive, resilience-promoting educational experience.

Author Contributions

MR-M, HK, JM, and RB made substantial contributions to the conception of the work. MR-M, JM, SR, KR, and RB contributed to the acquisition of data. HK analyzed the data, and MR-M, HK, JM, and MW contributed to its interpretation. MR-M drafted the manuscript, and all the other authors revised it critically for important intellectual content. All the authors approved the final version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of its accuracy and integrity.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the students who shared so freely during this study and to their parents for giving permission for their children to be involved. Thanks to all TSS staff who co-developed and co-administered the survey and to the school teachers and support staff for assisting TSS and CQUni researchers to work with the student ts. Thanks to Vicki Saunders for reviewing an early draft of the paper. Approval to publish this paper was provided by Research Services of the Queensland Department of Education and Training.

Funding

This manuscript was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council as part of project grant 1076774. The funding body played no role in design, collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; writing of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

- ^Traditional place of family origin.

- ^McCalman, J., Bainbridge, R., Redman-MacLaren, M., Russo, S., Rutherford, K., Hunter, E., et al. The collaborative development of a survey instrument to assess Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students’ resilience and upstream risk factors for self-harm. Front Educ. (submitted).

- ^Wenitong, M. (2016). Students from boarding schools and in their communities in Cape York will now be referred to a local Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Service for specialist support. J. McCalman. (personal communication).

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2012). 2011 Census Counts—Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples in Indigenous Regions. Canberra, Australia: A. B. o. Statistics.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2013a). Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Survey: Users’ Guide, 2012–13. Canberra: ABS.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2013b). Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander and Non-Indigenous Population, Remoteness Areas, Single Year of Age (to 65 and over), 30 June, 2011. Canberra: ABS. 3238.0.55001.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2009). Measuring the Social and Emotional Wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. Cat. no. IHW. Canberra: AIHW.

Benveniste, T., Dawson, D., and Rainbird, S. (2015). The role of the residence: exploring the goals of an Aboriginal residential program in contributing to the education and development of remote students. Aust. J. Indig. Educ. 44, 163–172. doi:10.1017/jie.2015.19

Boden, J. M., Sanders, J., Munford, R., Liebenberg, L., and McLeod, G. F. H. (2016). Paths to positive development: a model of outcomes in the New Zealand Youth Transitions Study. Child Indic. Res. 9, 889–911. doi:10.1007/s12187-015-9341-3

Calma, T. (2008). ‘Be Inspired’: Indigenous Education Reform. Melbourne, VIC: Victorian Association of State Secondary Principals.

Department of Education and Training. (2016). Transition Support Services. Available at: http://indigenous.education.qld.gov.au/community/Pages/tss.aspx

Garond, L. (2014). ““Forty-plus different tribes”: displacement, place and tribal names in Australia,” in Belonging in Oceania: Movement, Place-Making and Multiple Identifications, eds E. Hermann, W. Kempf, and T. van Meijl (New York: Berghahn Books), 49–70.

Geia, L. K. (2012). First Steps, Making Footprints: Intergenerational Palm Island Families’ Indigenous Stories (Narratives) of Childrearing Practice Strengths. Ph.D. thesis, James Cook University, Townsville.

Indigenous Education and Training Futures. (2010). Evaluation Report for Transition Support Services. Brisbane, QLD: Queensland Government Department of Education and Training.

Kelly, G. (2016). Map of Queensland, Communities and Schools in Pilot Phase of Resilience Study, 2016. Coffs Harbour, NSW: Gerard Kelly.

Kitchener, B. A., and Jorm, A. F. (2008). Mental Health First Aid: an international programme for early intervention. Early Interv. Psychiatry 2, 55–61. doi:10.1111/j.1751-7893.2007.00056.x

Lamb, S., Glover, S., and Walstab, A. (2014). Educational Disadvantage in Regional and Rural Schools. Melbourne, VIC: ACER Research Conference.

Lovett, R., and Walter, M. (2016). “Good methodology in analysis of data on Indigenous health and wellbeing,” in The Lowitja Institute International Indigenous Health and Wellbeing Conference (Melbourne, VIC: The Lowitja Institute).

Mander, D. J., Cohen, L., and Pooley, J. A. (2015a). A critical exploration of staff perceptions of Aboriginal boarding students’ experiences. Aust. J. Educ. 59, 312–328. doi:10.1177/0004944115607538

Mander, D. J., Cohen, L., and Pooley, J. A. (2015b). ‘If I wanted to have more opportunities and go to a better school, I just had to get used to it’: Aboriginal students’ perceptions of going to boarding school in Western Australia. Aust. J. Indig. Educ. 44, 26–36. doi:10.1017/jie.2015.3

Mander, D. J., Lester, L., and Cross, D. (2015c). The social and emotional well-being and mental health implications for adolescents transitioning to secondary boarding school. Int. J. Child Adolesc. Health 8, 131–140.

Mander, D. J., and Fieldhouse, L. (2009). Reflections on implementing an education support programme for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander secondary school students in a non-government education sector: what did we learn and what do we know? Aust. Community Psychol. 21, 84–101.

McCalman, J., Bainbridge, R., Russo, S., Rutherford, K., Tsey, K., Wenitong, M., et al. (2016). Psycho-social resilience, vulnerability and suicide prevention: impact evaluation of a mentoring approach to modify suicide risk for remote Indigenous Australian students at boarding school. BMC Public Health 16:98. doi:10.1186/s12889-016-2762-1

McNamara, B. J., Banks, E., Gubhaju, L., Williamson, A., Joshy, G., Raphael, B., et al. (2014). Measuring psychological distress in older Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders Australians: a comparison of the K-10 and K-5. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 38, 567–573. doi:10.1111/1753-6405.12271

Mellor, S., and Corrigan, M. (2004). The Case for Change: A Review of Contemporary Research on Indigenous Education Outcomes. Camberwell, Victoria: Australian Council of Educational Research.

Office of Economic and Statistical Research. (2013). Census 2011: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Population in Queensland. Brisbane, QLD: Queensland Treasury and Trade, Queensland Government.

Palm Island Aboriginal Shire Council. (2016). History of Palm Island. Available at: http://www.piac.com.au/documents/doc_HistoryofPalmIsland.pdf

Roeser, R. W., Eccles, J. S., and Sameroff, A. J. (2000). School as a context of early adolescents’ academic and social-emotional development: a summary of research findings. Elem. Sch. J. 100, 443–471. doi:10.1086/499650

Stewart, R., and Lewthwaite, B. (2015). Transition from remote Indigenous community to boarding school: the Lockhart River experience. Etropic 14, 91–97.

Tsey, K., Whiteside, M., Haswell-Elkins, M., Bainbridge, R., Cadet-James, Y., and Wilson, A. (2010). Empowerment and Indigenous Australian health: a synthesis of findings from Family Wellbeing formative research. Health Soc. Care Community 18, 169–179. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2524.2009.00885.x

UNESCO. (2016). Education 2030: Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action. Available at: http://www.uis.unesco.org/Education/Documents/incheon-framework-for-action-en.pdf

Ungar, M. (2016). What is Resilience? Available at: http://www.resilienceproject.org/

Ungar, M., Brown, M., Liebenberg, L., Othman, R., Kwong, W. M., Armstrong, M., et al. (2007). Unique pathways to resilience across cultures. Adolescence 42, 287–310.

Ungar, M., and Liebenberg, L. (2011). Assessing resilience across cultures using mixed methods: construction of the child and youth resilience measure. J. Mix. Methods Res. 5, 126–149. doi:10.1177/1558689811400607

Walter, M. (2016). “Data politics and Indigenous representation in Australian statistics,” in Indigenous Data Sovereignty: Toward an Agenda, Vol. Research Monograph No. 38, eds T. Kukutai and J. Taylor (Canberra: Australian National University Press), 79–98.

Keywords: resilience, well-being, Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander, remote, boarding school, Indigenous, suicide prevention

Citation: Redman-MacLaren ML, Klieve H, Mccalman J, Russo S, Rutherford K, Wenitong M and Bainbridge RG (2017) Measuring Resilience and Risk Factors for the Psychosocial Well-being of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Boarding School Students: Pilot Baseline Study Results. Front. Educ. 2:5. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2017.00005

Received: 12 December 2016; Accepted: 15 February 2017;

Published: 07 March 2017

Edited by:

Colette Joy Browning, RDNS Institute, AustraliaReviewed by:

Iffat Elbarazi, United Arab Emirates University, United Arab EmiratesMargo Bergman, University of Washington Tacoma, USA

Copyright: © 2017 Redman-MacLaren, Klieve, Mccalman, Russo, Rutherford, Wenitong and Bainbridge. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Michelle Louise Redman-MacLaren, bS5yZWRtYW5AY3F1LmVkdS5hdQ==

Michelle Louise Redman-MacLaren

Michelle Louise Redman-MacLaren Helen Klieve

Helen Klieve Janya Mccalman

Janya Mccalman Sandra Russo5

Sandra Russo5 Mark Wenitong

Mark Wenitong Roxanne Gwendalyn Bainbridge

Roxanne Gwendalyn Bainbridge