- Wilf Malcolm Institute of Educational Research, The University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand

In this paper, we report on a project conducted in a New Zealand primary school that aimed to enhance the writing achievement of primary school boys who were achieving just below the national standard for their age or level through the use of peer feedback and information and communication technologies (ICTs). The project involved a teacher collaborative inquiry approach where all seven teachers in the school and the school principal participated to achieve the project aim. We adopt an ecological approach as a lens to offer a holistic and comprehensive view of how peer assessment and use of ICTs can be facilitated to improve writing achievement. Data were collected through teacher interviews and written reflections of practice and student learning, teacher analysis of student work, team meeting notes, classroom observations, and student focus group interviews. Findings from the thematic analysis of textual data illustrate the potential of adopting an ecological approach to consider how teacher classroom practices are shaped by the school, community, and wider policy context. At the classroom level, our ecological analysis highlighted a productive synergy between commonplace writing pedagogy strategies and assessment for learning (AfL) practices as part of teacher orchestration of an ensemble of interdependent routines, tools, and activities. Diversity, redundancy, and local adaptations of resources to provide multiple pathways and opportunities—social and material and digital—emerged as important in fostering peer assessment and ICT use in support of writing achievement. Importantly, these practices were made explicit and taken up across the school and in the parent community because of whole staff involvement in the project. The wider policy context allowed for and supported teachers developing more effective pedagogy to impact student learning outcomes. We propose that an ecological orientation offers the field a productive insight into the contextual dynamics of AfL as classroom practice that is connected to the wider community and that has long-term value for developing student independence and learning outcomes.

Introduction

In this paper, we combine insights from research on ecological systems with insights from sociocultural views of learning to describe and theorize teachers’ experiences of establishing peer assessment that incorporated information and communication technologies (ICTs). Students developing the capacity for peer and self-assessment is a key aspect of Assessment for Learning (AfL). To achieve this, instructional programs aim to provide students with the opportunities and resources they need to monitor, reflect on, and regulate the quality of their understanding and work during its production. Research on writing, which is the focus of student learning in this paper, advocates many of these same ideas indicating a potential for productive synergy between AfL and writing practices. This said, understanding and enacting commonly recommended AfL practices as a coherent whole rather than a collection of individual strategies is known to pose a challenge for teachers.

This paper reports on a project that aimed to enhance the writing achievement of boys who were achieving just below the national standard for their year level, through an explicit focus on peer feedback and ICTs. The school was a middle sized Years 1–8 (students aged 5–12 years) in a medium-sized regional town. All the teachers and the principal participated in the project. Across the 18 months of the project, teacher individual and group interviews and team meeting commentary indicated they orchestrated peer assessment through the use of an ensemble of interdependent routines and tools which, to their delight, also developed student agency and discernment in monitoring their writing. Using an ecological framing allowed us to understand the importance of diversity, redundancy (multiple opportunities and pathways), and local adaptation in the activities and resources the teachers used to support peer assessment, especially for their students who were struggling to write. It highlighted for us, and the teachers, the interdependence of different strategies and resources they deployed. An ecological analysis assisted us in explaining how teacher actions were mediated by factors emanating from outside the classroom (Bronfenbrenner, 1979): the teachers were clear that their whole school approach, the resourcing and framing of the project, and wider government policy influenced their practice. This ecological analysis resonated with the teachers because it offered them a comprehensive and holistic explanation of their practice. We propose that it offers the field with a productive metaphor for understanding the conceptual, relational, material, temporal, and contextual dynamics of AfL classroom practice. In what follows, we illustrate the various aspects of an ecological approach, with its focus on the dynamics within and between multiple elements and levels of influence, to argue it has the potential to inform teacher practice and policy in AfL as integral to teacher support for student writing learning and achievement.

Theoretical Background and Framing

We conceptualize AfL as comprised of the everyday classroom practices that teachers, students, and peers use to generate, interpret, and act on information arising from dialog, demonstration, and observation with the aim of enhancing student learning, during the learning process (Cowie and Bell, 1999; Moss, 2008; Klenowski, 2009). With AfL, the ultimate goal is that students develop the capacity for self-assessment and self-monitoring (Sadler, 1989). In the short term, this relies on them developing and having the opportunity to exercise learning autonomy, agency, and discernment within and through day-to-day classroom activities (Cowie and Moreland, 2015). For this to happen, as Sadler wrote over 25 years ago, students need to come to hold and value a concept of quality roughly similar to that held by their teacher, to be able to monitor the quality of their understanding or what they are producing during the act of production itself, and to have a repertoire of moves or strategies they can use to progress their learning. From this description, we can see that student self-monitoring involves a set of interdependent activities which when combined support and enable students to evaluate and extend their own learning (Swaffield, 2011; Willis, 2011). For teachers, these student actions require that they support students to take responsibility for their learning by sharing or preferably co-constructing the goal(s) for learning and what constitutes quality, by providing students with opportunities to provide and receive feedback and incentives to self-monitor and to act on feedback from others. When combined, these AfL practices construe both learning and teaching as social and shared responsibilities, and they distribute authority. They highlight the need for resources that support discernment and decision making and empower students as autonomous and accountable learners (James and Pedder, 2006; Marshall and Drummond, 2006; Swaffield, 2011; Cowie et al., 2013). Unfortunately, there is ample evidence that teachers tend to enact AfL as a series of isolated practices rather than a coherent whole.

The strategies and activities initially proposed as central to formative assessment or AfL (Sadler, 1989; Black and Wiliam, 1998) can be seen as providing generic advice applicable to any year level and in any subject. More recently, it has been recognized that it is worthwhile considering how different curriculum learning areas and disciplines have different affordances and constraints for these practices (Coffey et al., 2011; Cowie and Moreland, 2015). Writing, which is the focus of this paper is a complex activity that has particular cognitive, metacognitive, and affective aspects. The substantial body of research on AfL within writing typically indicates the need to involve students in the creation, evaluation, revision, and editing of texts during production (Hawe and Dixon, 2014). It is not surprising then that studies focused on effective writing pedagogy suggest that the ways in which learning goals, success criteria, rubrics, and feedback are developed and enacted influence students’ understanding of writing and the writing process (Hawe et al., 2008; Timperley and Parr, 2009). Teacher modeling, reference to carefully selected exemplars, and substantive discussions around exemplars and the nature of writing are recommended as providing students with important insights into what constitutes “good” work (Parr and Limbrick, 2010). Ward and Dix (2004) illustrated that through dialog students and teachers can jointly construct achievement and the skills and understandings critical to students developing their writing practice. Authentic evaluative activities, enacted through peer feedback and student self-monitoring, can support writers to assess the value and efficacy of the texts they are composing while they are being created (Hout and Perry, 2009; Topping, 2010). For younger writers in particular writing also relies on technical skills such as capability with handwriting, spelling, and grammar (De Smedt and Van Keer, 2014), and these aspects also need to be developed. For all this to happen, teachers need to embed both formal and informal opportunities for peer assessment, peer response, and self-monitoring into writing lessons (Ward and Dix, 2004). However, how we understand these practices and AfL as whole is underpinned by how we view learning.

A number of researchers have traced the implications for AfL of how learning is viewed, see, for example, Black and Wiliam (1998), Elwood (2006), Hickey (2015), Shepard (2000), and Shepard et al. (2016). In our work, we employ a sociocultural understanding of learning and classroom assessment (Cowie and Moreland, 2015). This view acknowledges the social, relational, material, and temporal dimensions of learning and what counts as valid and valued knowledge and action (Gipps, 1999; Lemke, 2000; Moss et al., 2008b). More specifically, it acknowledges the extent to which interactions and student agency and action are contingent on and entangled with established patterns of participation and the conceptual and material and virtual resources that happen to be at hand (Cowie et al., 2013). Moss (2008) sums up our understanding in her claim that learning, assessment, and the exercise of agency cannot be separated from how the classroom learning environment is resourced with “knowledgeable people, material and conceptual tools, norms and routines, and evolving information about learning” (Moss, 2008, p. 254). Similarly, we agree with Moss et al. (2008a) that for teachers assessment should not only be about supporting student learning but also about teachers learning how to do this more effectively and how to support one another’s learning (p. 295). For the purposes of this paper, however, we have added insights from an ecological framing of educational settings to our sociocultural understanding. We found these additions were necessary to allow us to more fully account for teacher descriptions and explanations of their AfL actions and interactions.

Ecological understandings are increasingly being used in educational research in fields as diverse as those concerned with equity of opportunity and outcome (Lee, 2010, 2017), second language learning (e.g., Van Lier, 2010), the impact of the incorporation of ICTs on classroom learning (e.g., Zhao and Frank, 2003; Luckin et al., 2013) and the role of both informal and formal learning settings and opportunities (Russell et al., 2012; Falk et al., 2015). Ecological understandings of action and interaction have much in common with sociocultural theories in that both recognize the importance of context, including social, material, temporal aspects of the interaction between people and their environment. They both acknowledge this interaction as one that involves a process of mutual shaping and are interested in development over the longer term. In addition, however, and drawing on studies in biology, ecological explanations pay more explicit attention to the interdependence of the social, material, relational, and conceptual aspects of any setting. They emphasize the role and contribution of diversity, variability, or local adaptation as well as the importance of redundancy or multiple entry points and pathways across the various elements in a setting.

Useful for our purposes, an ecological theoretical approach pays explicit attention to the influence on individuals of context at different levels of proximity, including more distant factors. Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) work has been particularly influential in understanding the layers of context. The first level in Bronfenbrenner’s ecological framing includes the structures with which a child or person has direct relationships and interaction. For children, this includes family, friends, and teachers. His next (meso) layer provides the connection between these structures and includes relations between, for example, teachers and parents. Other, more distant layers, encompass the larger social systems that the shape family, school, school community, and wider societal values and practices. Bronfenbrenner notes that although a child may not be directly involved at these levels they nonetheless experience positive or negative impacts from the cascade of influence that arise through the interactions of the various layers. An example would be the extent to which the responsibility for education lies with teachers or is shared with parents. For our purposes, teachers in the context of classrooms are considered nested within schools and school communities and subject to influence from the wider policy and societal context.

In the following sections, we detail the research design that is underpinned by a sociocultural and ecological perspective to show how AfL practices come together as a coherent whole rather than a collection of individual strategies.

The Research Design

The project that informs this paper involved a case study of a whole school staff (seven teachers and the school principal) for 18 months as they collaborated to introduce peer assessment and greater use of ICTs as means to raise the writing achievement of boys within their school who were achieving just below the New Zealand national standards. The school provided evidence of a persistent challenge in reducing the number of boys in this category as part of gaining funding for the project. Over the 18-month period the teachers worked through three cycles of collaborative inquiry (Cycles 1–3) based on the APEX model (Thompson et al., 2009). The project received human ethical approval from our university ethics committee and all participants (students and their caregivers and teachers) consented to participating in the study voluntarily; all names are pseudonyms.

The APEX model begins with time spent identifying an aspect of student learning that is considered important enough to focus on for a sustained period (Windschitl et al., 2011). In our case, the focus was delimited by the research and development contract the school had been awarded— enhancing the writing of their boys who were achieving “just below” the “national standard” for their age or level by focusing on peer feedback and the use of ICTs. New Zealand has a system of National Standards (Ministry of Education, 2011) for reading, writing, and mathematics. Schools from Years 1–8 (students aged 5–12 years old) are required to report on student achievement against these standards at least once a year. Students are assessed being above, at, just below or well below the standard for their year level. In the project the school chose to focus on students achieving “just below” the standard because they had struggled to lift the writing achievement of students in this group over the previous 3 years.

During the first full team meeting for the project, the teachers reviewed the project goals and, as per the APEX model, negotiated a shared understanding of the key constructs—writing, feedback, and the possible contribution of ICTs. Statements for each of these aspects were posted in the school board room so that they were available for reference by the teachers and the school governors. Lessons were taught to all students but student work samples and notes on student interactions were collected from three target students per class over the three cycles of planning, action, and analysis.

The APEX model relies heavily on teacher data collection and analysis of target student work over time. Teachers collected writing samples from their target students for each of the three cycles of collaborative inquiry. The contract provided time for teachers to individually analyze and reflect on data from their classrooms and the practices that contributed to the data then come together to share and compare insights and identify patterns and trends across their practices and students’ responses and achievements. Following this analysis, possible teaching strategies for the next cycle were discussed and agreed. In addition to four dedicated team project meetings, the teachers discussed the approaches they were using and student responses and achievements as part of routine whole school staff meetings.

Teacher team meetings were audiotaped and teachers were interviewed beginning, middle, and at the end of the project. Teacher written reflections of own practice and student learning including analysis of student work were further collected as data. Data were also generated through student focus group discussions midway and at the end of the project and a small number of classroom observations. These data are not the focus of this paper given its focus on teacher views of the development of peer feedback within their classes.

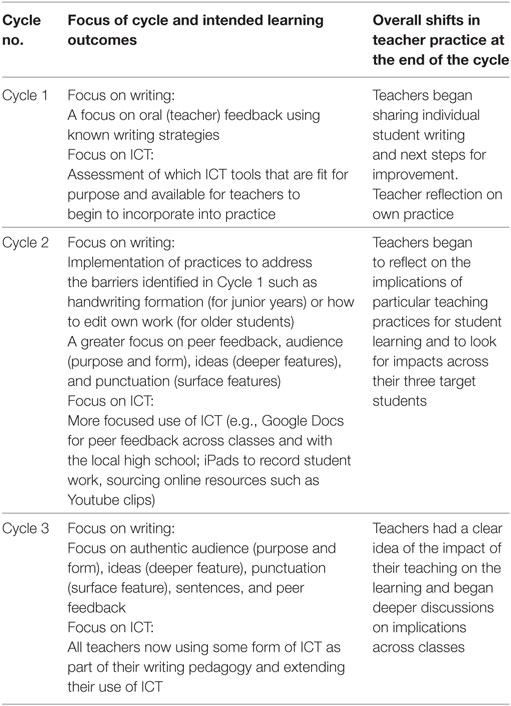

Each cycle encompassed the five phases of the APEX model and focused on a particular theme to offer multiple opportunities for students to write texts for authentic purposes and audiences and receive feedback (see Table 1).

Initially, we employed a thematic deductive approach to the analysis of the transcript data (Braun and Clarke, 2006) drawing on Moss’ (2008) proposition that we need to consider how the classroom learning environment is resourced with (i) norms and routines—we paid particular attention to the commonplace AfL and writing practices the teachers described, (ii) knowledgeable people—we considered how these people might be peers, teachers, family, and community members, (iii) material and digital tools and resources, and (iv) evolving information about learning—we considered developments in teacher and student actions over the course of the project. While scrutinizing the data for insights into these aspects, we noted that the teachers’ in their descriptions of their practice emphasized that they made deliberate use of multiple and interconnected activities and resources to scaffold peer feedback. These descriptions, along with teachers’ reflections on the value of a whole school approach and the influence of the parameters of the project contract, alerted us to the need for a more holistic and multi-layered analysis consistent with an ecological understanding of the enactment of AfL in their classrooms and school.

Findings

The findings are described using an ecological lens that focuses on the level of the classroom, the school and school community, and the ways the wider context play out and are interconnected to support AfL writing pedagogical practices focused on peer assessment and ICTs to enhance struggling boys’ writing achievement. Findings are exemplified with teacher and student quotes.

Classroom Level: Elaborating the Elements of the Classroom Ecological System for AfL

Norms and Routines within Classrooms: Activating AfL and Disciplinary Patterns of Participation

Feedback through “two stars and a wish”: The development of student peer assessment was a main goal of the project. As part of the first project meeting, the teachers decided to focus on “two stars and a wish” for junior students and “two medals and a mission” for older students as the strategy and routines they would use for peer feedback. This strategy was first introduced by Black and Wiliam (1998) (see also William, 2011) and is promoted by a number of professional development providers of AfL and writing in New Zealand. The consensus among the teachers was that the combination of affirmation for what students had done well and identification of what they could do next fitted with their teaching philosophy. They also anticipated that the strategy would be acceptable and manageable for their students, which it proved to be. The teachers were clear that they would need to assist their students to understand and make links to success criteria and to students’ provision of feedback. The need to support this connection was discussed in meetings 2–4.

Jacob (a teacher), in his end-of-project individual interview, identified the combination of the “two medals and a mission” and clear and co-constructed success criteria as one of the most effective approaches he had used, and one he would definitely continue to use:

Definitely the Two Medals and Mission, and using feedback as part of the [writing] process. That’s something I think as a school, we’ll continue doing and I will be most definitely doing. For the Two Medals and a Mission, it’ll be specific to what the focus is for that particular piece of writing. … For the students to give feedback, they need to know what to look for. And if students need to find evidence in their own writing of where they’ve made changes it focuses them in on what makes it a better piece of writing. So it (feedback) needs to be very specific about it. I’ll continue to make peer feedback more meaningful. We’d have to go back to co-constructing the success criteria. You need that buy-in from them from the start so that in the peer feedback they will be able to make the links between, ‘How did we start this off? What is it new that we wanted to learn? And what can we now feedback on?’ There needs to be the link between the success criteria and the feedback.

We can see from this comment Jacob considered his students needed to provide specific, rather than general or vague peer feedback. He was also clear about his own responsibilities in supporting this, “I can see that the children needed clearer guidelines and criteria and explicit examples of the kinds of feedback they can give their buddy.” In this comment, he also highlighted the interdependencies between student co-construction and ownership of success criteria, vision for where they have come from, and what sort of feedback that could add value to learning.

Caroline, another junior class teacher, also emphasized the link between feedback and success criteria and the need for feedback to be specific. She described how she prompted her students with, “Let’s look at what the criteria is. You know, what is our piece of writing? What’s the purpose of that? Did they use, you know, some alliteration? Like we were doing some in writing recently and did they do that?” Gina, yet another teacher, explained that when the two medals Raymond’s [a target student] new buddy had given him in his peer feedback were for the same thing (descriptive language) she had taken “the opportunity to coach him on how to be more specific.” And, “we talked about a mission has to be something specific that your buddy can action or do to improve their writing.”

The teachers were conscious of the diversity in the needs and strengths of their students. They provided examples of how they adapted materials and provided a range of resources to ensure their students had access to a range of different modes and means for giving and receiving feedback. Jacob explained his approach as follows:

With the more able writers the language and phrasing they use shows they’ve taken on board some of the models and examples I have shared with them this cycle. Two of the target students have been able to use the models and are giving better quality feedback, however, Roger [a target student] still struggles to verbalize his thinking at times. One idea I would like to try is giving him a bank of comments to use rather than expecting him to come up with his own ideas.

He reported he encouraged his students “to use iPads to film themselves reading out their work to a partner, feedback was then given verbally, and recorded on the same video clip” as another strategy to address his students’ needs and interests (Teacher reflection, December 2016). Margaret, with her Year 2 students, had developed a series of symbols to support her students to provide peers with “two stars and a wish.” The visual symbols helped remove the barrier of copious writing for young students. They also fostered their knowing what kinds of feedback to offer:

We’re starting to use lots of symbols with things. So children needn’t write copious sentences, or anything. We’ve got symbols for capital letters, and full stops. So they can start to use those symbols just as a Star and a Wish.

By the end of the project, the teachers were emphatic that they needed to allow time for students to think about and act on feedback. This was a practice that they had come to value more over the course of the project. Some teachers had changed their writing program to include a dedicated time to respond to feedback at the start of a writing session and or a session was set aside for responding to (peer) feedback. Debbie, the principal, summarized this shift as follows:

They have to look at it [feedback], read it, think about it, reflect on it, before they start their writing. So it had just become a part of that cycle. … now there’s a little bit more personal accountability. What we’ve done is we’ve raised the importance of that peer feedback, we’ve given it a real value [by] prioritizing time for it. (End-of-project interview)

Looking across this snapshot of teacher reflection on their peer assessment practices, we can see that they have raised many of the ideas and issues that are already to be found in research but through their own inquiries the teachers had, in the principal’s view, brought these research suggestions “to life.”

Re-visioning commonplace writing strategies: The teachers at the first team meeting recalled, reframed, and revisited a number of writing pedagogical strategies including the author’s chair, writing circles, and whole class teacher modeling. These strategies and their constituent norms and routines were common knowledge across the school because they had been a focus of previous professional development. They were not, however, being explicitly emphasized at the beginning of the project. Debbie, the principal explained in her end-of-project interview:

So within the first inquiry, that’s what I saw—lots of revisiting of all the good things that they [teachers] knew. And I think that was a really, really good place to start. So we were building on their knowledge and their confidence. So it wasn’t new, but they were remembering things. They went back and they re-read stuff. They started talking about, ‘Oh remember Gail [a person who had provided professional development for writing to the school staff] used to talk about ‘knee-to-knee,’ and the ‘Author’s Chair,’ and the importance of peer feedback.’

Teachers in their Cycle 1 meeting (Meeting 2) highlighted that practices such as the “Author’s Chair,” Mccallister (2008) “Writing circles” (Graves, 2003), and “knee-to-knee” had been effective in providing their young writers with an authentic audience and peer feedback. During her end-of-project interview Margaret, reflected on her own learning that even her young (age 5 years) target students were able to benefit from opportunities for sharing their writing and for feedback as part of the “Author’s Chair” strategy:

Five-year olds do have something to say. And they can say it in their own writing. But for me now, it’s another level of, ‘Yes I’ve got something to say, but I’ve also got something to say about your writing.’ I’ll definitely keep going with the peer feedback. I’ll keep going with my Author’s Chair, as we’ve done it. We’ll also keep celebrating those good things that we see in the writing.

The teachers, including Margaret, often followed up the Author’s Chair whole class activity by asking students to sit “knee-to-knee” and read their writing to each other (see Dix and Bam, 2016). This combination was thought to assist the students as reader–writers to stand back consider their own writing from an audience point of view and to think about the storyline within a peer’s writing and what suggestions for improvement they might offer.

The teachers repeatedly endorsed the value of their public modeling of the construction and deconstruction of text (Alamargot and Fayol, 2009; Parr, 2011) as a strategy for providing students with insights into the writing process and into the kinds of suggestions that would be useful as peer feedback. Typically, they described thinking aloud while writing in the class-modeling book. Margaret summed up the rationale for this process as follows:

Through modeling I was able to ‘show how’ and demonstrate how ideas might be selected, discarded, and organized coherently. By thinking out-loud, I demonstrated for students the decisions involved in the feedback process.

Modeling the provision of feedback using student work samples (with permission) was said to be more engaging for students than teachers composing texts that would benefit from critique. Caroline, explained:

Using their work has been really good. Getting their permission, ‘Are you okay? I’d love you to share your writing.’ ‘Can we use this?’ Rather than me doing all the time my kind of intentional errors and that sort of thing.

Teachers recorded task success criteria, both pre-specified and negotiated, in the class-modeling book. Relevant vocabulary, rules for punctuation, ideas for sentence starts were also recorded in the modeling book. In each classroom, the modeling book was stored in a prominent and easily accessible place, typically on an easel at the front of the room. Employed within a norm of voluntary access the class-modeling book was an important and widely used resource in support of independent peer feedback and self-assessment. It acted as a reference point that students could use to check, “What is good about ‘our’ writing?” (Teacher Meeting 2 comment).

Access to Knowledgeable People

Knowing the needs and expectations of the audience for a piece of writing is fundamental. For the project, the teachers’ intention was that their students would have opportunities to communicate with a wider audience. Pritchard and Honeycutt (2007) point out that when students write for and receive feedback from an authentic audience, writing becomes a purposeful communication rather than a task to be completed for the teacher. The teachers’ focus on authentic audience created a generative environment for student engagement in both writing and feedback. We have already set out some of the ways peers acted as an audience and source of feedback within the writing process. Here, we present further commentary on the value of ready access to peer feedback as part of writing and AfL. In line with our ecological stance, we also detail the contributions of those from outside the classroom—family and students from other schools.

The teachers each commented very positively on the way their students engaged in peer review conversations and also how this had allowed them to move around the class to give more individualized feedback. Gina summed up their experience as follows:

It has been amazing to see the conversations between the children, the support that they’ve been given by the tutors [selected peers] working with the writers. They’ve become more confident in their writing, they feel more sure of themselves and there’s no negativity toward the writing process. The one-to-one support in the peer editing has meant they don’t feel pressured or judged. The children have their goals, which they have glued in the front of their writing books and they are aware of working toward these. This has given me more opportunities to move around the class, working and supporting where I see the need.

Students from Jacob’s class were enthusiastic about the value of feedback from their friends because:

Child 1: When you have just finished your writing, you can’t see what you need to work on. And then friends see it, and they see lots you need to work on.

Child 4: Because next time you write it, it makes your writing better. (End-of-project focus group interview)

The use of ICTs to support students’ writing was one of the main foci for the project and all the teachers, with the exception of Margaret who taught 5-year olds, used Google Docs in their writing program. Google Docs was chosen as a promising ICT tool to use to facilitate student collaboration and feedback as the school had begun investigating ways to take advantage of internet, mobile, and cloud-based networked services in preparation for rolling out a school-wide ‘bring your own device’ initiative. Using Google Docs simultaneously expanded the audience for student writing and those who were able to provide feedback. Among the teachers, Deborah made the most use of Google Docs—she taught a senior class and she and her class began the study with the most experience and expertise in its use. Deborah’s use of Google Docs for feedback highlighted both benefits and challenges. For example, Deborah began by “giving feedback via Google Docs instantly, but I stopped doing that and gave it at the end—the end of a session, the end of the day” (Teacher reflection, December 2016). She gave two reasons for this. First, she found it was impossible to give feedback to more than a few children within a lesson, and second, she found that her feedback interrupted the flow of students’ writing because they stopped and responded to her feedback. Hannah, another teacher who also taught senior students, had not used feedback on Google Docs prior to the project commented similarly that, “At first it was quite invasive, and it took over and it disrupted the flow of writing, but now it seems to be quite automatic that they [students] resolve those things and act on them straightaway, and just move on” (End-of-project interview).

Students reported the use of Google Docs extended the opportunities they had to work on their writing and the pool of readers who were the audience for and could provide feedback on their writing. Some students were now writing at home and sharing their writing with siblings and parents. These students said they appreciated being able to access input from their peers, teacher, or parents outside of school hours:

Child 2: If you’ve got this writing that you don’t really understand, you could ask your parents to help you. And you can always contact the teacher.

Child 3: And my Mum and Dad, they’ll read it, and they’ll say, ‘This doesn’t make sense’ so I could change it because you have even more feedback, feedback from your parents.

As part of the project, Sally’s class used Google Docs to share their writing with a senior class at the local high school. The senior high-school students acted as “critical friends” and provided Sally’s students with feedback on their work. Three pieces of writing were shared via Google Docs. Sally commented that her students were always keen to ensure their writing was of the highest quality before they sent it to their critical friend. She considered this need had produced a qualitative shift in students’ motivation to evaluate and improve their writing, and consequently in the quality of writing they shared with her for her feedback. Examples of peer feedback that the students received from their critical friend ranged from those that focused on surface features and those that focused on deeper features of writing. An example of a student reflection on his critical friend’s feedback was, “He taught me how to use some descriptive words and where to put them. He also helped me change my words around to make them sound better.” The high-school students were in overwhelming agreement that the partnership had been productive for them and that it should be continued with more frequent writing feedback contact between the two schools in the next year. Sally’s primary school students also wanted to see the exchange continue.

Overall, teacher comments on the increase in student confidence in and willingness to provide and receive feedback can be seen as an indication that trusting relationships had been established between peers and with their teachers. They can also be taken as an indication that the classroom culture had become one where peer and self-assessment was expected and accepted as part of a commitment to learning as a shared and social process.

Material and Virtual Resources

Discussion of AfL tends to focus on the role of dialog (e.g., Harrison, 2006) but material artifacts provide scenarios and resources for AfL interactions (Cowie et al., 2013). Teacher commentary indicated that they developed and used both material or virtual and digital resources to support their students’ involvement in peer and self-assessment. We have already detailed the important role class-modeling big books played in informing and coordinating student participation in peer and self-assessment. In addition to this well-known writing pedagogical tool, the teachers developed other resources to support their students’ learning. In her end-of-project interview Caroline explained how, by the second cycle, she realized she needed to develop resources that would support student independence:

After Cycle Two, I realized I needed to go back and ‘unpack’ or ‘revisit’ how we recraft or edit our writing and also the ‘peer editing’ process. I went on the hunt for suitable examples and models. These have been introduced to the class, modeled, used and are always made available to the children during our writing sessions.

The material Caroline developed and used included phonics cards, cards with lists of word to assist with spelling, with example sentence structures and with ideas for writing. She co-constructed with her students a checklist for the process of peer assessment and printed this off for students to refer to when editing their own work. Her students were also able to access PowerPoints and videos. Caroline explained that her next step would be to collate a range of resources into folders that children could keep in their desks to “pull out” whenever they were writing. This proposition gained support from other teachers at the final meeting, who indicated they had similar plans.

All the teachers made use of videos or YouTube clips to stimulate student interest and to provide examples of different genres such as how to write a report, a scientific description, and give an informative and entertaining speech. Jacob provided the most expansive description of these strategies. He began the sequence of lessons that would culminate in students giving a speech by discussing with the class what judges would be looking for in a speech. Most of the students had given speeches before but some indicated they had not been aware of what judges looked for. Jacob went through what he would be looking for noting that content was only part of the effectiveness of a speech. The class brainstormed some criteria and then watched three sample speeches on YouTube. They discussed what had made the speeches interesting and added these ideas to their list of criteria. The criteria were recorded in the class-modeling book. Students used these to review and make changes to their speech during its development. Jacob commented that this process allowed his students “to discover among themselves success criteria that they can add to what they’ve already got. It’s not me telling them, ‘Oh I want you to include asking rhetorical questions’.” Jacob’s example illustrates the role (material and virtual) resources can play in supporting student agency and ownership of criteria.

Evolving Understanding about Learning

In the final team meeting and their end-of-project interviews teachers offered evidence that their students were now taking responsibility for monitoring and acting to improve their writing. As a group, we identified this as a goal the teachers shared albeit it had not been a direct focus for the project. The teachers considered that their focus on peer assessment had, in many cases, supported students’ proactive and discerning participation in self-assessment because students were able to make independent use of the routines and resources that had been developed. Put another way, they were of the view that their focus on peer assessment had made what was involved in the process of monitoring their own writing more transparent to students (Black et al., 2003). When students participated in reciprocal peer feedback (Tsivitanidou et al., 2017), that is, they provided and received feedback as listeners/readers and as writers, they gained access to new ideas and approaches and deepened their understanding of their own writing. Just as importantly, teacher comments indicated this process had scaffolded students to a view that their writing could be enhanced and that the improvement process was a social one.

Margaret, in her end-of-project individual interview, commented as follows on the shift in her students’ actions. She stated:

I think Cycle Three was just doing more of what we had initiated in Cycle Two and the children were becoming more adept at it. It was becoming the norm. They were up and along the line (to talk with her), they would buddy up even if it wasn’t their feedback buddy, they would pair up, they’d read each other’s writing first, and then come to me, I wasn’t having to ask them ‘Okay now, could you read yours,’ and, ‘Could you read and share.’ It was just part of our writing process now. So we’ve come a long way with our feedback and also with our self-editing.

Comments similar to this from other teachers also suggested their students had come to appreciate that writing was usefully undertaken as a social process in which they gave, received, and acted on feedback.

Sally’s senior students were clear that it was their access to different view points that made the “two medals and a mission” process productive:

Interviewer: You’ve mentioned Two Medals and a Mission. Do you think that’s a good idea to use?

Multiple voices: Yes.

Child 1: Like you get both sides of the thing [writing] fed back. They don’t have to just say what you have been doing good. You know what to go back and do.

Child 2: You get good feedback and just feedback to improve your story.

Child 3: And because if you don’t really know what you’ve done wrong, the other person helping you can detect what’s wrong.

Child 4: And if more people look at it, you get to make more sense with it.

Further evidence of the shift in student understanding came from teacher reports that students were spontaneously sharing their work with others outside of writing sessions. Caroline explained how her students’ independent activation of peer feedback support had transferred to other curriculum learning areas:

Caroline: It took Cycle Three for me to really know, ‘Now I think we have got somewhere with this, now it’s become autonomous. Now they just expect it.’ They get up from finishing their work and it’s just, without me going, ‘What’s the next step?’ They know now [to go and talk to someone else]. So what’s been lovely is, it’s not just the writing, not just like when you do a piece of writing, but it might be something that they do with reading.

Researcher: Oh, so it’s transferable?

Caroline: It has transferred. In Science, you know, with our inquiry, when we’ve written some of our thinking, our predictions, or our thoughts they’ll go and find someone else. And they will sit down and, you know, they’re not trying to do Two Stars and a Wish for it but they’re, ‘I’m going to go and share this with someone.’ It’s not just written for the sake of writing. So that’s been quite lovely. There was always buddy work going on in, in my classrooms, but this has stepped up, its’ a nice surprise for me.

Researcher: And has it stepped up in terms?

Caroline: How it has lifted a level is that they’ve (students) taken ownership of it. It’s not me directing them how to and telling them what they should do. And I just think it’s giving them that independence. I would see that as life-long learning. That they’re taking this now, that they’ve been drawn into a sort of way of approaching their work. (End-of-project interview)

Student spontaneous use of peer assessment in other learning areas suggests that they recognized learning is a social process within which they could exercise agency and which came with responsibilities to assist others (Marshall and Drummond, 2006). They had developed the discernment needed to be able to make productive use of the range of available resources—social-relational as well as material and virtual.

The Classroom as an Ecological Setting where the Whole Is More than the Sum of the Elements

To this point, we have provided a description of the different elements of the classroom ecology for AfL as understood by the teachers but the particular value of an ecological approach is its strong emphasis on the whole being more than the sum of the parts—on the interdependence of elements. An ecological view also foregrounds the value of diversity and redundancy among the elements as well as developments over time (Lee, 2010, 2017; Gutiérrez et al., 2017). When reflecting on their classrooms, the changes they had made to their practice and the practices they would retain and or seek to develop further, all seven teachers described a constellation of inter-related practices, routines, and resources, as can be seen in the examples presented earlier. Importantly, the different strategies and activities they detailed offered students a diverse range of material and digital resources and social supports to draw from, often without the need for teacher direction and or permission. These provided multiple entry points and opportunities to employ success criteria and feedback. In reflecting on the development of their class’s capacity to engage in peer feedback the teachers emphasized that while students had become competent, student facility with any one idea or practice could not be taken for granted. The following comment by the Debbie summarized their view:

The children got better at peer feedback I think but it’s something that has to be. You can’t just assume that because they did it well this time, because next time they’ll hold back. So it’s something you’ve got to continue—they’ll slip back and forwards, and back and forwards.

All in all the teachers’ comments suggested that they were keenly attuned to the integrative developmental and temporal nature of AfL for students—strategies needed to be revisited, adapted, elaborated, and refined as topics and genres changed, and as students gained expertise.

School and Community Level: Considering the Influence of the Local Context

Proponents of a systems view of assessment assert the need to consider how stakeholders at all levels of the system influence practice (e.g., Stiggins, 2006). Moss et al. (2008a) writing within a sociocultural frame, acknowledge the need to consider the school, and wider context. Those working within an ecological view argue that to understand the functions of one level of the educational ecosystem it is useful to look up and down one level as well as across time scales (Lemke, 2001; Gutiérrez et al., 2017; Lee, 2017). In this section, we present themes from the teacher reflections that link to the project’s whole school approach and involvement with the school community.

Looking beyond the level of their individual classrooms, the teachers were pleased that they were involved in the project as whole school staff. The day spent at the beginning of the project coming to a shared understanding, “vision statement” of what would count as “good” writing, the nature of effective feedback and possibilities for ICTs use was seen as vital to the success of the project despite the fact that at the beginning of the first meeting day the teachers considered they already had a shared understanding of these constructs. The discussion on feedback and peer feedback in particular was important. It drew on empirical studies of writing and AfL (Tunstall and Gipps, 1996; Pritchard and Honeycutt, 2007; Dix and Cawkwell, 2011) and it explored why praise does not count as feedback (Black and Wiliam, 1998). Teacher consensus was that effective feedback directs attention to the intended learning, helps students see what they know and what they need to keep working on, and requires students to know success criteria. The time teachers spent coming to a shared understanding of these key constructs meant that these understandings or visions became a conceptual resource that teachers could draw on to coordinate their actions and as a platform to anchor and inform their analysis and discussions. Debbie, the principal noted in her-end-of-project interview with us:

So when we talked about feedback. They all felt that they knew a lot about feedback, and that we do that anyway. And it’s really interesting because that’s what I’ve noticed. Our understanding now of feedback is so much different than what it was at the beginning. But at the beginning, they thought that they were doing it. … But again, they [feedback strategies] weren’t evident in the classroom…. There wasn’t a consistency across the school.

The teachers saw advantages in them all focusing on peer feedback through a two affirmations and one suggestion for next steps strategy. For example, they were expecting their collective focus on this strategy would have benefits when students changed classes and or teachers because “the kids coming through will be more knowledgeable” (Debbie, Principal, End-of-project interview).

The APEX model as a process of collaborative inquiry provided an anchor when teachers were struggling with the challenge of changing their practice. Heidi explained how the APEX phases supported their working toward the same goals for enhancing their pedagogy and student learning.

It is a lot of work, to be prepared, but it is very valuable. And it is really important when you work together to have a clear structure. Something clear that everyone understands and can work toward. I really liked how we had teaching for 6 weeks and gathering the data and the samples, and the annotation and then the coming together and talking about it, and then working out what was going well, and what our next steps were. And then working on that for a few weeks and coming back. I think we worked really well collaboratively as teachers. The team meetings were great, the moderation—moderating—was so helpful. We are all, we are all on the same page.

Mutual accountability based on sharing classroom work and reflections is part of the APEX model. Because the project was a whole school project time was allocated to talking through ideas and progress at staff meetings alongside and in addition to the formal project meetings. Heidi explained:

So it was really important that we had opportunities to talk through our understandings. Every, possibly three weeks, we would have an opportunity where we would put boys’ literacy project on the agenda. ‘How are we going? What’s our next thing?’ We’d quickly share how the writing samples were going.

The project strengthened trust, collaboration, and the learning culture across the staff as a whole. The following excerpt from the final teacher meeting at the end of the project evidenced this shift:

Teacher 1: I think having the project as a platform has opened up the communication for me. So you can come here and give your reflections and not feel threatened. You know, people are going to ask questions, or give advice, and it’s done in a constructive manner.

Teacher 2: And trends, trends too, it’s not just focused on your kids.

Teacher 3: We [teachers] were all working in our separate little rooms, in areas but when we come together, as the first one starts [first teacher began to share analysis of student work], straight across the board, we’ve all noticed, picking up so many common trends and things.

This segment of conversation also illustrates the value for teachers of opportunities to identify trends and patterns in student writing and what was effective pedagogically and thus might be useful to try.

Also relevant, information about the project was displayed in the school meeting room where the school board of governors, which included parents, met regularly. The project was featured in the local newspaper and the teachers shared their findings with other schools in the local area. These actions, in conjunction with students sharing their writing via Google Docs, linked the project and teachers into the wider school community as both a support and source of expectations.

Wider Policy Level: The Contract as a Mediational Means

The project that forms the basis for this paper was a Teacher Led Innovation Fund (TLIF) project and part of the government’s Investing in Educational Success initiative that aims to lift student achievement and to offer new career opportunities for teachers and principals (see http://goo.gl/tJGA45). The fund requires teachers to put up a proposal to investigate an initiative that will address a challenge their school faces. In our study, the TLIF contract provided a reference point when teachers queried the purpose of their involvement and the effort this entailed. In her end-of-project interview, the principal elaborated on how she used their whole school commitment to the contract to motivate and re-energize teachers:

I was pushing it from the point of view [of] this is a contract, this is what we are contracted to deliver, nothing’s changed, we agreed to it, you know, in June last year. I kept revisiting, you know? Our purpose, why we’re doing it, what we agreed to do. … I just kept going back to purpose, our shared understanding—just to re-energize them [teachers], that this is our work.

A key aspect of the TLIF fund is that time for teachers to be released from class is built in. Our TLIF contract provided time for individual and collective reflection and analysis. Deborah, a senior teacher, explained how in her view that time for quiet reflection had been integral to her professional learning and development:

A lot of the stuff in the middle [of lessons] happens but once you’ve had time to actually stop and think about it, and you’ve started thinking what you could do better, what could I change—that reflection part of it was probably the most important. So having that time to reflect is essential.

Having time for discussion together was also essential, as Deborah explained:

Allowing time for those discussions, because I think that’s what we learnt with the Teacher Only Day. We only got through a quarter of what we needed to do. I think then that was really important, to have time. And then remember we extended our project for another cycle, because of it. So I think that was really good.

The teachers considered that the project timeline allowed them, and their students, the time they needed to develop the various knowledges and skills involved in making productive use of peer feedback processes. Table 1 above details how their focus and actions shifted over the three cycles as insights from one cycle provided a springboard for action in the next cycle.

The TLIF model for inquiry projects requires schools to make use of an “expert” to inform their project. We, the authors of this paper, acted in this role along with a colleague whose research was in writing pedagogy. We provided research articles for the teachers to read and attended the team meetings where our main function was to pose questions to assist teachers to deeper personal reflection on their professional practice and to see links across their experiences. In this way, our role was consistent with Timperley et al. (2007) recommendation that external experts can act to challenge assumptions and to present teachers with new possibilities and keep the focus on students and their learning.

Concluding Comments and Limitations

In this study, we worked with all the teachers in a small primary school using the APEX model’s cycles of inquiry approach to enhance struggling boys’ writing. The teachers had posited that a combination of peer feedback and the use of ICTs would enhance the writing of their students, the boys who were struggling in particular. As part of the TLIF project they re-introduced, re-visioned, and introduced a range strategies aimed at developing student capacity and motivation to provide useful feedback to peers, and to self-assess. Their reflections on their classroom practices and student actions resonated with the notion of them having established a classroom culture where student and student initiated peer and self-assessment were valued and supported. Student provision of and action on feedback was made possible through routines and norms that supported interaction and initiative, easy access to a range of knowledgeable people, to material and virtual resources, and contributed to an evolving understanding of learning as a social process and joint responsibility (Marshall and Drummond, 2006; Moss, 2008). Important to us students’ spontaneous use in other curriculum learning areas of the peer assessment practices used for writing indicated that they were developing capacities and inclinations that carried over to other times, places, and learning areas. This context appeared to provide the resources that supported student discernment and decision making and empowered them as autonomous and accountable learners (Cowie et al., 2013).

Adopting an ecological view allowed us to put forward an explanation of teacher experience of AfL that recognized that the interactions between the elements of the classroom process constituted a whole that was greater than the sum of the parts. Our viewing these elements from an ecological perspective, rather than a solely sociocultural perspective highlighted that teacher orchestration of the interaction and interdependence between these elements can support student engagement and develop student capacity and willingness to provide peer feedback and to self-assess. Diversity, redundancy, and a degree of local classroom adaption of supports for learning and peer assessment were integral to teacher provision of multiple entry points and genuine choices for students when accessing and providing help. Student access to different people as an audience and source of feedback was one aspect of this diversity and redundancy. So too was the way feedback was made available—verbal, written, video recorded, via Google Docs. Students’ ready access to an abundance of social and material resources is significant if a classroom is to provide an equitable and resilient ecology for student learning. When students can access a phlethora of resources it becomes more likely that the classroom context will accommodate and activate the diversity within and across student needs, interests, and capabilities as a resource for learning (Lee, 2017).

Viewing AfL from an ecological perspective had value in understanding the way student AfL experience is nested with and influenced by the school and wider community. For students, the use of Google Docs played a key role in breaching the classroom walls. Their use allowed students to interact with teachers, peers in another school, and parents and siblings outside of class time. Student learning was thus supported by their ready access to a wider range of “knowledgeable people” from both inside and outside the classroom as both an audience and sources of feedback. This is important in the New Zealand policy context where parents are positioned as partners with teachers and students in the (AfL) assessment policy (Ministry of Education, 2011) and practiced (Cowie and Mitchell, 2015) context.

Our adoption of an ecological framing directed our attention to the influence on teacher classroom practice of multiple levels of context. At the level of the school, teacher commentary indicated their participation as a whole staff in an inquiry process based around analysis of student work and mutual accountability via regular sharing of student work and the context of its production ensured all teachers experienced a level of challenge and support for change. They were able to learn from each other about the impact of different practices. They were able to identify trends and patterns in ways that appeared to fast-forward their learning. Teacher commentary indicated that, as Moss et al. (2008a) recommend, their participation involved them in learning about how to better support student writing through AfL and it provided opportunities, incentives, and understandings of how to support each other’s learning. It is of note that they depicted their participation as a learning experience that incorporated many of the recommended features of AfL/peer assessment: a clearly articulated and shared goal for development and learning, opportunities for action and sharing of experience, with the latter aspect doubling as an occasion for giving and receiving feedback that affirmed particular actions and highlighted potential next steps. Wider school community support was important to them, especially the positive feedback they received from peers when they reported on the project. At the level of policy, the TLIF contract as part of the government’s Investing in Educational Success (http://goo.gl/a15ZYw) scheme provided an agenda and resources for the teachers’ interactions—collegial and pedagogical.

In putting forward a multi-layered ecological view to frame understandings of AfL, we acknowledge the work of Carless (2005), Cooper and Cowie (2010), Hickey et al. (2006), and Xu and Brown (2016). What we believe is new is our explicit consideration of the interactions within and across the layers of context when a whole school staff aims to enact a particular aspect of AfL—in this study peer assessment that incorporates ICT. Adopting a holistic-systemic ecological perspective allowed us to consider how AfL was enacted in a classroom and how other stakeholders and levels of the system influence teacher classroom practice and student experience. We propose that an ecological orientation offers the field a productive insight into the contextual dynamics of AfL as classroom practice that is connected to the wider community and that has long-term value for developing student independence and learning outcomes. With Gutiérrez et al. (2017), we consider that by paying careful attention to the breadth of tools and support systems available to teachers, and students, we are likely to be better able to design arrangements and tools that foster learning in the present for the future. We hope this paper will contribute to further ideas for effective educational practice and policy.

Ethics Statement

Ethics Committee, Te Kura Toi Tangata Faculty of Education, The University of Waikato. Participation in the research was voluntary. All participants gave informed consent—both parents and children gave signed consent. The choice to participate or not was explained to the children at the beginning of each interview. Teachers and students were also advised as to how their data might be used—in reports to teachers, as part of conference presentations and in articles.

Author Contributions

We contributed equally to the data collection, analysis and reporting, and preparation of this paper.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge funding support from the Teacher Led Innovation Fund (TLIF), New Zealand Ministry of Education for the project titled Enhancing boys’ writing through transformational eLearning pedagogy.

Funding

Data were collected as part of a New Zealand Ministry of Education Teacher Led Innovation Fund project.

References

Alamargot, D., and Fayol, M. (2009). “Modelling the development of written composition,” in Handbook of Writing Development, eds R. Beard, D. Myhill, M. Nystrand, and J. Riley (London, England: SAGE), 23–47

Black, P., Harrison, C., Lee, C., Marshall, B., and Wiliam, D. (2003). Assessment for Learning: Putting it Into Practice. Berkshire, England: Open University Press.

Black, P., and Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assess. Educ. 5, 1. doi: 10.1080/0969595980050102

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3, 2. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Carless, D. (2005). Prospects for the implementation of assessment for learning. Assess. Educ. 12, 39–54. doi:10.1080/0969594042000333904

Coffey, J. E., Hammer, D., Levin, D. M., and Grant, T. (2011). The missing disciplinary substance of formative assessment. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 48, 1109–1136. doi:10.1002/tea.20440

Cooper, B., and Cowie, B. (2010). Collaborative research for assessment for learning. Teach. Teach. Educ. 6, 979–986. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2009.10.040

Cowie, B., and Bell, B. (1999). A model of formative assessment in science education. Assess. Educ. 6, 101–116. doi:10.1080/09695949993026

Cowie, B., and Mitchell, L. (2015). Equity as family/whānau opportunities for participation in formative assessment. Assess. Matters 8, 119–141. doi:10.18296/am.0007

Cowie, B., and Moreland, J. (2015). Leveraging disciplinary practices to support students’ active participation in formative assessment. Assess. Educ. 22, 247–264. doi:10.1080/0969594X.2015.1015960

Cowie, B., Moreland, J., and Otrel-Cass, K. (2013). Expanding Notions of Assessment for Learning. Rotterdam: Sense. doi:10.1007/978-94-6209-061-3

De Smedt, F., and Van Keer, H. (2014). A research synthesis on effective writing instruction in primary education. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 112, 693–701. doi:10.1016/j.sbosbourspro.2014.01.1219

Dix, S., and Bam, M. (2016). Writing about bugs: teacher modelling peer response and feedback. Teach. Curric. 16, 1. doi:10.15663/tandc.v16i1.131

Dix, S., and Cawkwell, G. (2011). The influence of peer group response: building a teacher and student expertise in the writing classroom. English Teach. 10, 41–57.

Elwood, J. (2006). “Views of assessment, learning and mind: exploring the links and implications for emerging trends and perspectives on assessment,” in Paper presented at 32nd Annual Conference, International Association for Educational Assessment (Singapore).

Falk, J., Dierking, L., Osborne, J., Wenger, M., Dawson, E., and Wong, B. (2015). Analyzing science education in the United Kingdom: taking a system-wide approach. Sci. Educ. 99, 145–173. doi:10.1002/sce.21140

Gipps, C. (1999). Sociocultural aspects to assessment. Rev. Educ. Res. 24, 353–392. doi:10.2307/1167274

Graves, D. H. (2003). Writing: Teachers and Children at Work (20th anniversary ed.). Portsmouth, New Hampshire: Heinemann.

Gutiérrez, K., Cortes, K., Cortez, A., DiGiacomo, D., Higgs, J., Johnson, P., et al. (2017). Replacing representation with imagination: finding ingenuity in everyday practices. Rev. Res. Educ. 41, 30–60. doi:10.3102/0091732X16687523

Hawe, E., and Dixon, H. (2014). Building students’ evaluative and productive expertise in the writing classroom. Assess. Writ. 19, 66–79. doi:10.1016/j.asw.2013.11.004

Hawe, E., Dixon, H., and Watson, E. (2008). Oral feedback in the context of written language. Aust. J. Lang. Literacy 3, 43–58.

Hickey, D. (2015). A situative response to the conundrum of formative assessment. Assess. Educ. 22, 202–223. doi:10.1080/0969594X.2015.1015404

Hickey, D., Zuiker, S., Taasoobshirazi, G., Schafer, N. J., and Michael, M. (2006). Three is the magic number: a design-based framework for balancing formative and summative functions of assessment. Stud. Educ. Eval. 32, 180–201. doi:10.1016/j.stueduc.2006.08.006

Hout, B., and Perry, J. (2009). “Toward a new understanding for classroom writing assessment,” in The SAGE Handbook of Writing Development, eds R. Beard, D. Myhill, J. Riley, and M. Nystrand (Los Angeles: SAGE), 423–436.

James, M., and Pedder, D. (2006). Beyond method: assessment and learning practices and values. Curric. J. 17, 2. doi:10.1080/09585170600792712

Klenowski, V. (2009). Assessment for learning revisited: an Asia-Pacific perspective. Assess. Educ. 16, 3. doi:10.1080/09695940903319646

Lee, C. (2010). Soaring above the clouds, delving the ocean’s depths. Educ. Res. 39, 643–655. doi:10.3102/0013189X10392139

Lee, C. (2017). Integrating research on how people learn and learning across settings as a window of opportunity to address inequality in educational processes and outcomes. Rev. Res. Educ. 41, 88–111. doi:10.3102/0091732X16689046

Lemke, J. (2000). Articulating communities: sociocultural perspectives on science education. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 38, 296–316. doi:10.1002/1098-2736(200103)38:3<296::AID-TEA1007>3.0.CO;2-R

Lemke, J. (2001). The long and the short of it: comments on multiple timescale studies of human activity. J. Learn. Sci. 10, 17–26. doi:10.1207/S15327809JLS10-1-2_3

Luckin, R., Clark, W., and Underwood, J. (2013). “The ecology of resources: a theoretically grounded framework for designing next generation technology-rich learning,” in Handbook of Design in Educational Technology, eds R. Luckin, S. Puntambekar, P. Goodyear, B. Grabowski, J. Underwood, and N. Winters (New York, NY: Routledge), 33–43.

Marshall, B., and Drummond, M. (2006). How teachers engage with assessment for learning: lessons from the classroom. Res. Papers Educ. 2, 2. doi:10.1080/02671520600615638

Mccallister, C. A. (2008). “The author’s chair” revisited. Curric. Inquiry 38, 455–471. doi:10.1111/j.1467-873X.2008.00424.x

Ministry of Education. (2011). Ministry of Education Position Paper: Assessment (Schooling Sector). Wellington, New Zealand: Learning Media.

Moss, P. (2008). “Sociocultural implications for assessment: classroom assessment,” in Assessment, Equity, and Opportunity to Learn, eds P. Moss, D. Pullin, J. Gee, E. Haertel, and L. Jones Young (New York: Cambridge University Press), 222–258.

Moss, P., Girard, B., and Greeno, J. (2008a). “Sociocultural implications for assessment II: Professional learning, evaluation, and accountability,” in Assessment, Equity, and Opportunity to Learn, eds P. A. Moss, D. C. Pullin, J. P. Gee, E. H. Haertel, and L. Jones Young (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 295–332.

Moss, P., Pullin, D., Gee, J., Haertel, E., and Young, L. (2008b). Assessment, Equity, and Opportunity to Learn. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Parr, J. (2011). Supporting the Teaching of Writing in New Zealand Schools: Scoping Report to the Ministry of Education. Wellington, New Zealand: Learning Media.

Parr, J., and Limbrick, E. (2010). Contextualising practice: hallmarks of effective teachers of writing. Teach. Teach. Educ. 26, 583–590. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2009.09.004

Pritchard, R., and Honeycutt, R. (2007). “Best practices in implementing a process approach to teaching writing,” in Best Practices in Writing Instruction, eds S. Graham, C. A. MacArthur, and J. Fitzgerald (New York: The Guilford Press), 28–49.

Russell, J. L., Knutson, K., and Crowley, K. (2012). Informal learning organizations as part of an educational ecology: lessons from collaboration across the formal-informal divide. J. Educ. Change 14, 259–281. doi:10.1007/s10833-012-9203-4

Sadler, D. (1989). Formative assessment and the design of instructional systems. Instruc. Sci. 18, 119–144. doi:10.1007/BF00117714

Shepard, L. (2000). The role of assessment in a learning culture. Educ. Res. 29, 7. doi:10.3102/0013189X029007004

Shepard, L., Penuel, W., and Davidson, K. (2016). Using Formative Assessment to Create Coherent and Equitable Assessment Systems. Boulder: University of Colorado Boulder.

Stiggins, R. J. (2006). Balanced Assessment Systems: Redefining Excellence in Assessment. Princeton, NJ: Educational Testing Service.

Swaffield, S. (2011). Getting to the heart of authentic assessment for learning. Assess. Educ. 1, 4. doi:10.1080/0969594X.2011.582838

Thompson, J., Braaten, M., Windschitl, M., Sjoberg, B., Jones, M., and Martinez, K. (2009). Examining student work: evidence-based learning for students and teachers. Sci. Teach. 76, 48–52.

Timperley, H., Wilson, A., Barrar, H., and Fung, I. (2007). Teacher Professional Learning and Development: Best Evidence Synthesis Iteration (BES). Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Timperley, H. S., and Parr, J. M. (2009). What is this lesson about? Instructional processes and student understandings in writing classrooms. Curric. J. 20, 1. doi:10.1080/09585170902763999

Topping, K. J. (2010). “Peers as a source of formative assessment,” in Handbook of Formative Assessment, eds H. L. Andrade and G. J. Cizek (Abingdon: Routledge), 61–74.

Tsivitanidou, O., Constantinou, C., Labudde, P., Ronnebeck, S., and Ropohl, M. (2017). Reciprocal peer assessment as a learning tool for secondary school students in modeling-based learning. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 33, 51–73. doi:10.1007/s10212-017-0341-1

Tunstall, P., and Gipps, C. (1996). Teacher feedback to young children in formative assessment: a typology. Br. Educ. Res. Assoc. 22, 4. doi:10.1080/0141192960220402

Van Lier, L. (2010). The ecology of language learning: practice to theory, theory to practice. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 3, 2–6. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.005

Ward, R., and Dix, S. (2004). Highlighting children’s awareness of their texts through talk. set 1, 7–11.

Willis, J. (2011). Affiliation, autonomy and assessment for learning. Assess. Educ. 18, 4. doi:10.1080/0969594X.2011.604305

Windschitl, M., Thompson, J., and Braaten, M. (2011). Ambitious pedagogy by novice teachers? Who benefits from tool-supported collaborative inquiry into practice and why. Teach. Coll. Rec. 113, 1311–1360.

Xu, Y., and Brown, G. T. L. (2016). Teacher assessment literacy in practice: a reconceptualization. Teach. Teach. Educ. 58, 149–162. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2016.05.010

Keywords: assessment for learning, writing, feedback, ecological perspective, whole school approach, collaborative inquiry, ICTs

Citation: Cowie B and Khoo E (2018) An Ecological Approach to Understanding Assessment for Learning in Support of Student Writing Achievement. Front. Educ. 3:11. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2018.00011

Received: 09 May 2017; Accepted: 06 February 2018;

Published: 23 February 2018

Edited by:

Susan M. Brookhart, Duquesne University, United StatesReviewed by:

Chad M. Gotch, Washington State University, United StatesLeslie Ann Eastman, Lincoln Public Schools, United States

Copyright: © 2018 Cowie and Khoo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bronwen Cowie, YnJvbndlbi5jb3dpZUB3YWlrYXRvLmFjLm56

Bronwen Cowie

Bronwen Cowie Elaine Khoo

Elaine Khoo