- 1Educational Psychology Department, The University of Oklahoma, Norman, OK, United States

- 2Department of Culture, Curriculum, and Teacher Education, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, United States

The purpose of this research is to examine teachers’ capacities and the role trust plays in the professional lives of teachers during the transition to a new team of three administrators in an elementary school located in a low-income urban community in the United States. Twenty-seven teachers’ surveys and interviews showed that the transition caused some level of instability and uncertainty; however, teachers had a positive sense of efficacy, social capital, resilience, and emotions. The four themes that emerged from the interviews—common goals and vision for students, beliefs in colleagues’ competence, emotional safety and comfort, and being vulnerable with colleagues—appear to function as conditions to build trust among colleagues. The trusting relationships seem to help teachers withstand the challenging transition by providing a safe space where teachers can learn and grow. Implications for school administrators and district offices were discussed.

Introduction

School cultures and climates that foster teachers’ learning and development are considered key contributors to students’ achievement and ongoing progress (Thoonen et al., 2012; Liu et al., 2016). Establishing a positive and motivating school culture does not happen overnight; rather, it requires deliberate and long-term effort necessitating stable leadership. In particular, existing research has noted the significant role of school administrators in shaping norms, values, and structure of the school, which consequently impact student learning (Leithwood et al., 2004). This impact on student learning is considered “indirect,” as they do this by developing a school culture, vision, and organizational structure, in which effective teaching and learning are supported (Hallinger and Heck, 1998; Heck and Hallinger, 2009). Thus, investing in establishing and sustaining a school culture and social context that are conducive for teacher learning and teacher development is a worthwhile effort (Bryk et al., 2010; Leithwood et al., 2010).

However, despite the need for and importance of stable school leadership, schools often experience frequent principal turnover. While statistics vary depending on the study site and data collection methods, the turnover rates of school administrators were between 11% and 28%. According to the Principal Follow-up Survey that consisted of principals in public and private schools across the United States, 7% of school principals moved to a different school (movers), and 12% left the principalship altogether after 1 year (leavers; Golding et al., 2014). According to the accumulated data at the state level, the percentage of movers after 5 years was approximately 31%, and leavers were 21%, which constitute a turnover rate of over 50% (Fuller et al., 2007; Plecki et al., 2017).

When schools have administrator turnover, they become vulnerable. Depending on the culture and climate the former administrators established, and the way incoming administrators develop relationships with teachers, the school could be on the upswing or the change could catalyze a downward spiral. The new administrators may be able to improve school culture and morale by revitalizing the school vision and goals and addressing issues that have not been the focus of the former administration. On the contrary, the school climate and morale may begin to decline due to inconsistencies in the past and current school vision and communication or decreased teacher satisfaction and well-being. As such, principal succession and transition generate complex dynamics within the school.

Studies that have unpacked this complexity and addressed the impact of school administrator change on school culture are sparse. Only a few studies have provided empirical evidence regarding the change of school culture during the transition of school administrators. Meyer and Macmillan have conducted several studies (e.g., Macmillan et al., 2004; Meyer et al., 2009, 2011) and found that, generally, principal turnover contributed to a decrease in teachers’ efficacy, trust, and morale, although some schools maintained their status quo. While these studies provide insights into the impact of school administrator change on school culture, much remains unknown about how teachers respond to the change and transition, and the ways this kind of change influences teachers’ well-being. In particular, studies that investigated shifts in school culture during transition are rare. To fill this gap, in this study we focused on an urban elementary school in the United States during an overhaul of the administrative team including the principal and two assistant principals. By examining various aspects of teacher capacity and the interpersonal dynamics within the school, this study aims at unpacking the complexities of school climate during the transition time.

Capacity Building and Trusting Relationships

As opposed to the “outside” view that addresses externally developed reform efforts and its impact on schools (Thoonen et al., 2012), capacity building is considered an “inside” view (Sleegers et al., 2010), as it focuses on the professional growth of teachers and the collective strength that derives from individual and collective reflection on their beliefs and practices. Thus, capacity building includes various aspects of individual teachers’ growth such as teacher efficacy, resilience, and emotions, as well as collective strength of the group such as social capital and trust building. As numerous studies noted (e.g., Tschannen-Moran and Hoy, 2001; Klassen et al., 2011), teachers’ sense of efficacy, which is a “teacher’s belief in his or her capability to organize and execute courses of action required to successfully accomplish a specific teaching task in a particular context” (Tschannen-Moran et al., 1998, p. 233), has a positive association with teachers’ emotional well-being (Skaalvik and Skaalvik, 2007), job satisfaction (Klassen et al., 2009), and commitment (Klassen and Chiu, 2011). As a context dependent construct, teachers’ self-efficacy is formed and changed in relation to various contextual factors that are fluctuating and changing. This implies that it is important for teachers to be situated in professionally nurturing environments in order to support teaching excellence. However, given the current reality of administrative instability, teachers must have not only self-efficacy but also a sense of resilience “to adapt to changing demands, to recover, and to remain vigorous after the changes have occurred” (Schelvis et al., 2014, p. 631). As a multidimensional and socially constructed concept, resilience provides a useful lens to unpack how and why teachers maintain their motivation and commitment in their everyday lives (Day and Gu, 2014). In addition to teachers’ self-efficacy and resilience, teachers’ emotional well-being is another key component of their professional lives. Teaching is fundamentally emotional work, and the type and intensity of emotions teachers experience impact their job satisfaction, teaching effectiveness, and overall well-being (Schutz and Zembylas, 2009).

In addition to individual teachers’ capacities, relational dynamics within the school also shape the culture and climate of the school (Fullan and Hargreaves, 1992; Gu, 2014). Hargreaves and Fullan (2012) addressed the importance of relationships using the concept of social capital. Social capital is conceptualized as “how the quantity and quality of interactions and social relationships among people affects their access to knowledge and information; their senses of expectation, obligation, and trust; and how far they are likely to adhere to the same norms or codes of behavior” (Hargreaves and Fullan, 2012, p. 90). A key aspect of social capital is that social resources are exchanged through the relationships (Bourdieu, 1986; Goddard, 2003). In the school setting, strong and positive relationships teachers have can result in the exchange of beneficial social resources such as trust, care, and support.

While all relational dynamics matter within the school, teachers’ relationships with colleagues have been recognized as one of the key conditions in enabling teachers to develop competencies and professional capacities (e.g., Fullan, 2003; Hong, 2010; Hong and Looney, 2019). This is why numerous studies across various school contexts have addressed the importance of building a supportive, encouraging, and collaborative teacher community (e.g., Sammons et al., 2007; Vescio et al., 2008; Day and Gu, 2010). As Gu (2014) emphasized, without the mutual effort, collaborative connections, and shared sense of commitment, individual teachers are less likely to manage various challenges and hardships successfully.

Among many qualities that define relational dynamics, this study foregrounded trusting relationships among teachers during transition time. Trust is often defined as “a teacher’s willingness to be vulnerable to another party based on the confidence that the latter is benevolent, reliable, competent, honest, and open” (Hoy and Tschannen-Moran, 1999, p. 189). As this definition shows, trust is not a quality that resides within an individual; rather, it is a quality developed through interpersonal dynamics and fluctuates as relationships change over time in various contexts (Lee et al., 2011). Thus, it is critical to study trust not only at the individual level but also at the interpersonal and organizational levels. When trusting relationships are developed within the school, it might provide teachers opportunities to exchange necessary resources, to challenge themselves and each other with a sense of security, and to enhance their sense of efficacy, resilience, and emotional well-being. Thus, trust has been recognized to improve teacher motivation (Li et al., 2016), professional learning (Thomsen et al., 2015), and collaboration focused on school improvement (Bryk and Schneider, 2002), all of which contribute to developing a positive and healthy school culture.

Given the significance of trusting relationships on the quality of teachers’ professional lives, we focused on examining the role trust played in the professional lives of teachers to unpack the complexities during the transition to a new team of three administrators.

Research Questions

• What are teachers’ capacities (including efficacy, resilience, emotions, and social capital) during administrator transition?

• What role does trust play in how teachers experience their relationships among colleagues during administrator transition?

Materials and Methods

The study employed a mixed methods case study design (Creswell and Plano-Clark, 2017), which includes both quantitative data and qualitative data from a defined case. The bounded system of this study is an elementary school (pseudonym: Highland Elementary School) located in a low-income urban community in the United States, where all three school administrators changed at the same time. The data were collected between 1–3 months after a new administrative team joined the school. Ethics review board approval was obtained prior to the data collection, and ethical standards and procedures were followed by getting informed consent forms, using pseudonyms, and storing data in secured and password protected computer devices.

Participants

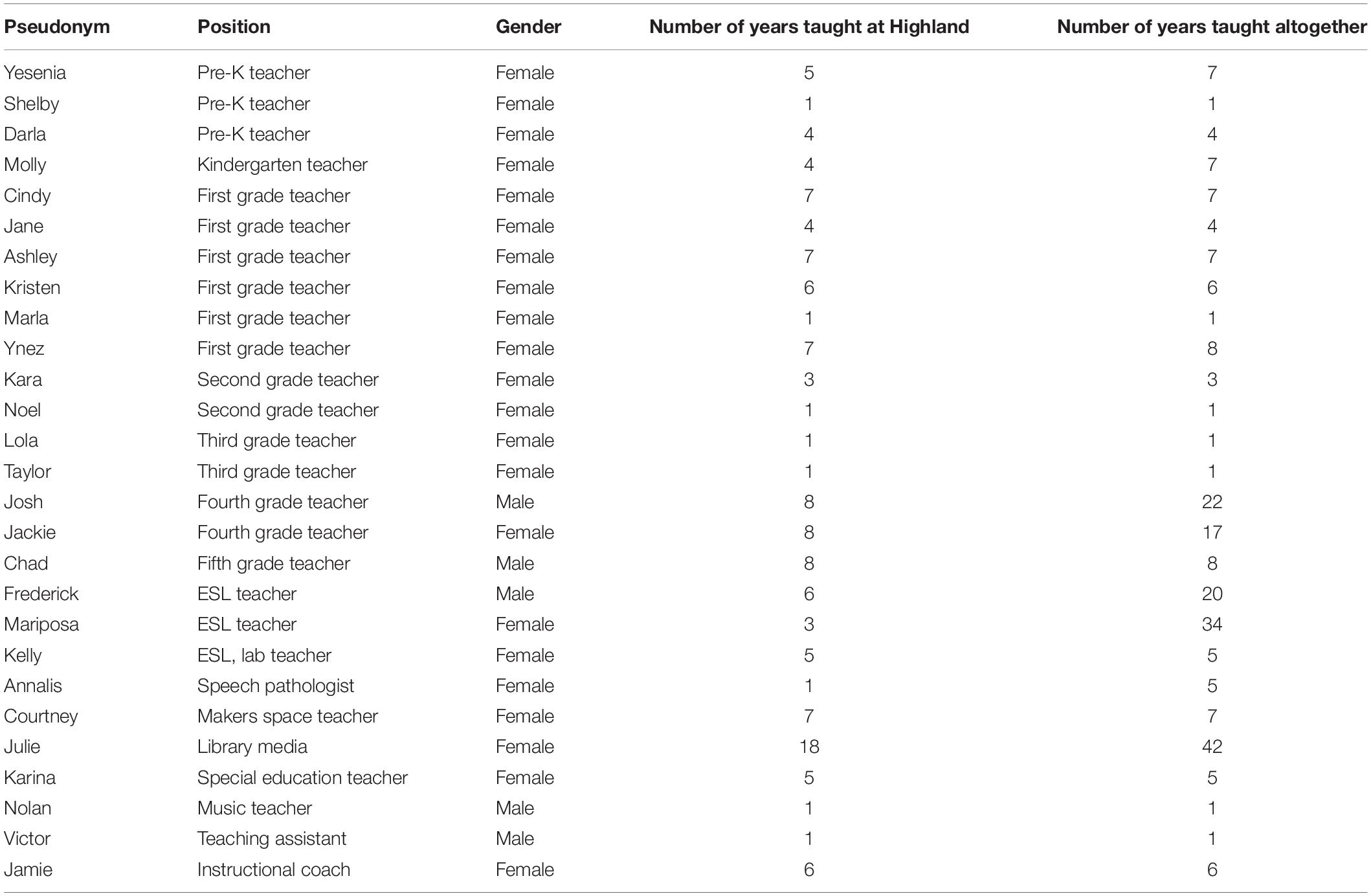

Twenty-seven teachers (pre-k through fifth-grade teachers and resource teachers) working in the Highland Elementary School volunteered to participate in this study following the start of three new school administrators. Table 1 summarized the participants’ background information.

Data Sources

Quantitative Survey

We employed the following four measures: (1) a 12-item Teacher Self-Efficacy scale developed by Tschannen-Moran and Hoy (2001) in order to measure teachers’ perceived competence about student engagement, instructional strategies, and classroom management; (2) a 15-item Teacher Social Capital survey developed by Hargreaves and Fullan (2012) to capture the collective power of the group; (3) a 20-item Achievement Emotions Questionnaire – Teachers (AEQ-T) scale developed by Frenzel et al. (2010) and modified by Hong et al. (2016). This survey measures five discrete emotions: pride, frustration, anger, anxiety, and excitement; and (4) a 23-item Teacher Resilience Scale developed by Hong et al. (2018) that consisted of two sub-constructs of managing emotional well-being and seeking social support. All measures used five-point Likert scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), except the Teacher Self-Efficacy scale that had a nine-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (nothing) to 9 (a great deal).

Qualitative Interview

Semi-structured interviews were conducted to further unpack the quantitative outcomes. Interview questions were designed to capture teachers’ perceptions and experiences of developing trusting relationships among colleagues by asking questions about interpersonal dynamics and communication among teachers as well as ways to seek help, exchange social resources, and address instructional and emotional concerns. Interviews lasted between 45 to 110 min and were audio-recorded, then fully transcribed verbatim.

Data Analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics to summarize scores for each survey. In order to explain the quantitative outcomes, qualitative data were analyzed using both inductive analysis (LeCompte and Preissle, 1993) to reduce the extensive texts into core meaning units, and constant comparison methods (Strauss and Corbin, 1998) to compare similarities and differences of the participants. In order to ensure trustworthiness, multiple researchers triangulated data analysis and constructed emergent matrices. Overall themes from the analyses and variations that emerged from the matrices were summarized into narrative forms.

Results

Teacher Capacity

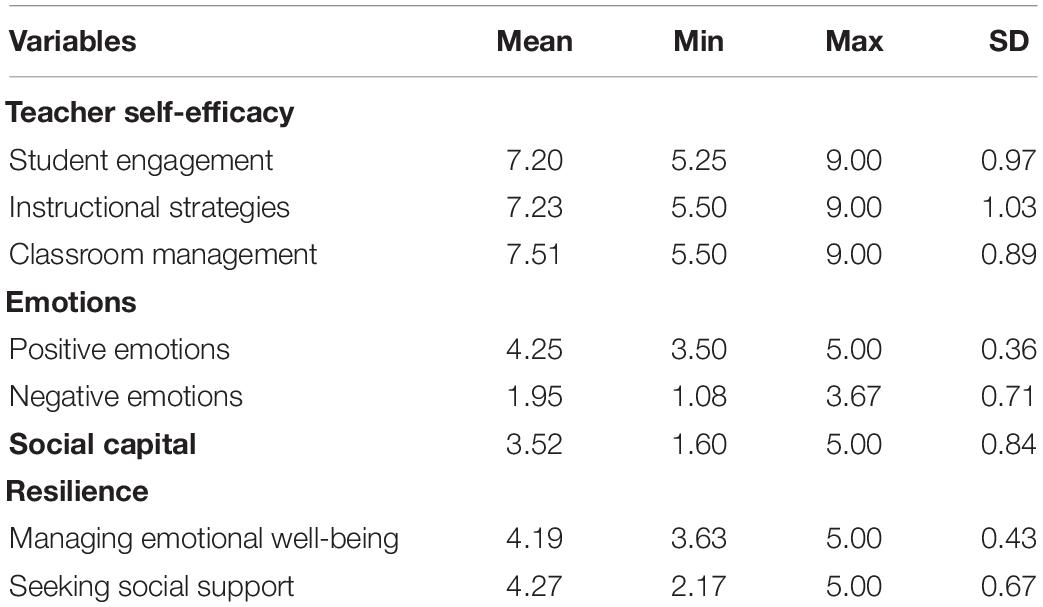

As shown in Table 2, quantitative data of this study showed that teachers working in Highland Elementary School had high levels of self-efficacy for all three sub-constructs of student engagement, instructional strategies, and classroom management; demonstrated strong social capital; tended to show more positive emotions than negative ones; and had a strong sense of resilience.

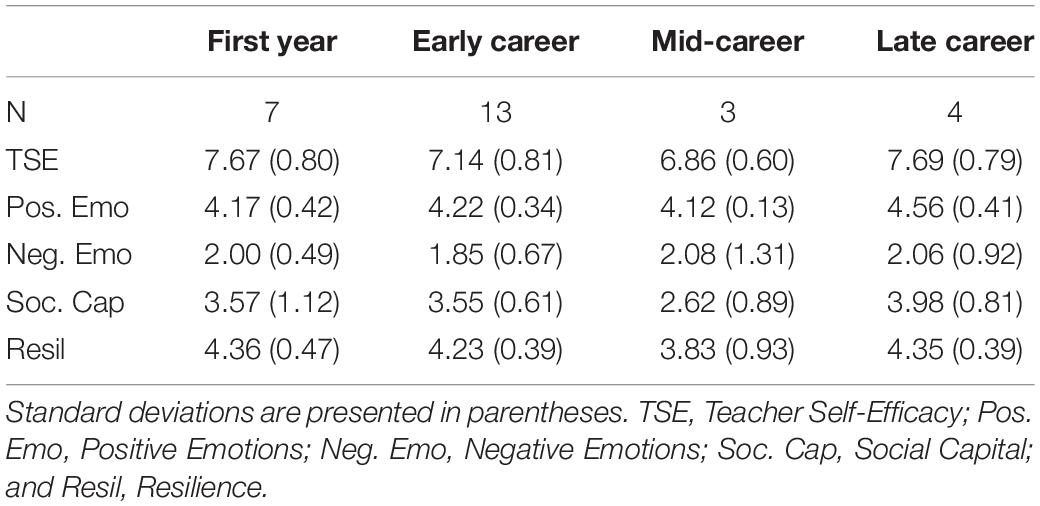

We further analyzed the quantitative data based on the teachers’ years of experiences, as existing research suggested that length in the profession impacts teachers’ perceptions of themselves and overall capacity (Huberman, 1995; Day et al., 2007). Aligned with previous research, we categorized them into four groups: first year, early career (2–7 years), mid-career (8–20 years), and late career (20 + years). Table 3 shows each group’s mean and standard deviation for teacher self-efficacy, positive emotions, negative emotions, social capital, and resilience. While the sample size is small and uneven across the four groups, the three mid-career teachers showed slightly lower self-efficacy, less positive emotions, more negative emotions, and weaker social capital and resilience than other teachers. This is aligned with the notion of a “mid-career crisis” (Huberman, 1989) or “detachment/loss of motivation” (Day et al., 2007), which describe when teachers became disengaged and disenchanted with the teaching career.

These quantitative findings are echoed by qualitative findings. Teachers often addressed their strong self-efficacy about “interacting with the kids” or “relationship with kids,” which seems to help them have better classroom management, student engagement, and instructional strategies. For instance, Marla, a first-grade teacher, noted, “I just feel like I’m doing a really good job with building a relationship with each and every one,” and then explained further how it helped her students being engaged, “I know them very well and I know what can make them laugh or make them calm down or get them to start working again.” In terms of teachers’ emotions, although teachers addressed both positive (e.g., excited, enjoyment) and negative emotions (e.g., overwhelmed, fatigued), their experiences that induced negative emotions were often alleviated by colleague teachers’ emotional support. Victor commented how his colleagues reassured him of his abilities whenever challenges arose and he doubted the impact he made to his students.

“They [colleague teachers] tell me like every single day just how well that I’m doing and how much of an impact I have on the kids…sometimes I feel like I don’t have a strong impact… but they tell me like ‘the kids really look up to you’… when I hear stuff like that, it just warms me.”

Emotional support from colleagues was often addressed as one of the key features of social capital, which encouraged teachers to seek and give help, and collaborate. Kristen described her strong team dynamic and support.

“We always help each other out. We plan together. If we ever have a question about something, we’re always willing to help academically or even behavior-wise. So, any situation. If we’re unsure how, what, how to deal with a parent or a student, we’re always there to help each other and give advice.”

Many other teachers at Highland Elementary also often addressed the collaborative and nurturing culture, which seemed to increase their collective power and agency. Consequently, colleague support and help became sources of strength that helped them to adapt to challenges, be resilient, and stay “committed to the process, and believe in what we’re doing.”

The positive and strong teacher capacity that were evidenced in both quantitative and qualitative data in this study contrasts existing studies that have reported a negative school atmosphere, such as cynicism, among teachers and lack of commitment when administrators changed (e.g., Fink and Brayman, 2006; Mascall and Leithwood, 2010).

Relationship With Administrators

In order to further investigate this unusual and interesting phenomenon, in-depth individual interviews were analyzed to determine the ways teachers at Highland Elementary described their experiences and relationships within the school. First, we asked how they felt about the transition and relationships with their new administrators, including one principal and two assistant principals. Teachers generally felt frustrated due to lack of communication among the new administrators and between teachers and administrators. Courtney, a science/maker space teacher, noted that there was broken communication between teachers and administrators, especially when decisions were made in a top-down manner.

“I wished communication was better. Coming from an administration to us about decisions made or the change of location of a faculty meeting. I mean just the communication I feel like it is not there. Decisions that are made and then you find out last minute from an email that should have been sent days before, but it got sent last minute.”

Consequently, the lack of communication often made teachers feel hesitant to reach out to the administrators for help, or even if they did, no help was provided. For instance, Kristen and Karina commented, respectively, “It can be hard for us to communicate or talk to them because we don’t feel like we’re very supported in certain situations,” and “There are teachers that call for help and no one comes… So, it’s not just me. It is a school-wide feeling of a lack of support.” The rough transition teachers experienced was well-summarized by Kelly, an ESL teacher, “I think it [supportive school culture] kind of started going down a little bit. We were definitely feeling there wasn’t as much leadership as we have had in the past.”

Relationship With Colleagues

While teachers described the rough transition with new administrators, their collegial relationships were clearly positive, demonstrating several characteristics of trusting relationships. These trusting relationships seemed to help teachers effectively navigate the chaotic transition. Four themes emerged from the interviews that showed various aspects and dynamics of trusting relationships among colleagues: (i) common goals and vision for students, (ii) beliefs in colleagues’ competence, (iii) emotional safety and comfort, and (iv) being vulnerable with colleagues.

Common Goals and Vision for Students

Teachers in Highland Elementary School consistently mentioned the shared goal of “teaching for the better.” These ideals were expressed in the ways they communicated with each other, with the students, and also in their decision-making and actions. Courtney and Marla commented on their mindset and approach to working with students, respectively, “We’re always pushing students to better themselves. I mean, we have high expectations for our students and their achievement,” and “They [teachers] are truly here to teach for the better and teach for the future and teach for our kids.” The teachers had high expectations for their students and organized their classrooms and interaction with the students in ways that are aligned with this perspective. This collective belief in the capabilities of their students and knowing that they were a part of a larger community with this shared vision motivated the teachers to focus on their goals and work hard. These common goals seemed to serve as a secure foundation that provided cohesion and stability despite fluctuations in leadership or daily happenings.

A valued aspect of this working environment was that teachers did not just talk about these ideals in ways that were isolated from action. Having these shared goals and acting accordingly helped foster this sense of “team-ness,” where they felt and acted in ways that overtly supported each other. For example, teachers collectively worked to enlist greater parental participation and to improve communication with parents, share instructional materials and strategies, discuss students’ behaviors and learning outcomes, and support by “giving each other advice” and “offer help.” Shelby’s comments exemplified this “team-ness”: “We work really, really well together. We all are not afraid to talk to each other, we communicate really well. I guess kind of like the biggest thing for us, we’re together, we’re a team… we’re able to collaborate really well.” As such, the shared goals were visible in teachers’ collective actions, which consequently helped them improve their teaching.

Beliefs in Colleagues’ Competence

Highland teachers also consistently mentioned their beliefs in colleagues’ competence and professionalism. Valuing their colleagues’ expertise was described in two ways: confidence in being able to share the work and students, and exchanging expertise. Josh gave an example of how teachers shared the work, students, and classes, which was possible because of the confidence they had that their colleagues were competent.

“We try to be pretty tight in sharing things, we do that together. Building inquiry, common assessments with that. For a few years, we would flex across the grade level with different reading groups. You have four classes and four or five classrooms and you share class, students. Kids were reading at this level and this one. we can have time to collaborate from like eight-fifty to ten-ten. Work together. Share data. Go over common assessments.”

Likewise, Ynez answered how teachers in the first grade trusted each other’s expertise and collaborated to help students.

“We take a different portion of our lessons and we input that into our lesson plans and then we talk about it… And in small groups we actually divide our classroom kids up into levels, so some of my kids go to small groups with another teacher, and then they come to me. We have two small group rotations.”

Also, teachers’ beliefs in colleagues’ competence seemed to be a foundation to build collective capacity and social capital that allowed teachers to exchange beneficial resources. For example, Mariposa described her appreciation of being able to draw on the expertise of a more experienced and knowledgeable colleague. She said, “I feel very comfortable especially with Fred, because he’s been doing this for a long time and I can go and ask him questions and all that.” For Mariposa, she valued her colleague’s experience and the opportunity to get his input on issues and the ease with which she was able to do that.

Yesenia echoed this point, “How do we get the ones that don’t know how to get it? What are we doing wrong, or what else can we do? Because I might teach something a certain way and she might teach something a little different, so maybe I should try it her way and maybe that will get my low students to do it.” For Yesenia, she appreciated being in an environment where there were multiple valuable approaches to attending to student learning. There was comfort in knowing that if her strategy failed, she had intellectual resources from which she could readily draw to address the problem. The confidence in colleagues’ competence and professionalism seemed to subsequently contribute to the sense of emotional safety and comfort, which is the next theme discussed below.

Emotional Safety and Comfort

Teachers in this school also reported a strong sense of emotional support from colleagues. The feelings of comfort and belongingness within their grade level teams allowed some teachers to bond in friendship. As Jane described, she considered her colleagues friends and expressed that this relationship was a central reason she stayed at the school, “I would call them probably some of my best friends. That’s the only reason why I’m here, is because of them.” Ynez specified the aspects of the relationship with her team that made her feel supported and safe and that she was a part of a family.

“First grade has a great team. We collaborate, we work together, we spend time outside of school hanging out, and it’s like a family here. Openness is really important. Honesty is important. If I tell them something that’s private, they understand that and respect that.”

Similar to experiences of nurturing friendships and familial relationships, Ynez valued the support she received in attending to and resolving both work and personal issues, the ability to be honest, and the freedom she felt in the opportunities to be open when issues arose. As exemplified in Ynez’s comment, openness and honesty were highly valued among the teachers, along with the support they received when they did share, “I know that I can go to them [other first grade teachers] for anything if I’m having a personal issue or a conflict with a student, I have their support.”

Central to these relationships was affection, the feelings of care that were expressed and felt by the teachers within the groups. Ashley elaborated on the closeness she felt with her colleagues and how helpful it was to be able to share teaching-related experiences and rather than being judged, receive understanding, empathy, and encouragement.

“If I’m talking to them about an issue or something that happened that day, having the emotional support of, ‘Yeah, me too,’ or ‘It was a really rough day for me too.’ And then I’m thinking, ‘Oh, okay. There must be something in the air. It must be a full moon, it’s not just me.’ And so, it’s helpful to just have that kind of [support].”

Across the descriptions of the teachers, we see the interconnectedness of care, openness, and honesty as core aspects of professional support and supportive feelings of emotional safety. Within this community of care, teachers talked about the love they felt toward the profession, their students, and colleagues as well as the ways in which their team provided safety and support despite the challenges they had faced during the leadership transition. It was clear that even if administrators’ transition came with uncertainty, inconsistency, and lack of support, the caring, open, and honest relationships among colleagues continued to stay stable to provide emotional safety and comfort that empowered teachers to be effective. Such emotional comfort is closely connected to the last theme, being vulnerable with colleagues.

Being Vulnerable With Colleagues

Teachers uniformly mentioned their appreciation for the expertise of more experienced and knowledgeable colleagues, and felt comfortable drawing on the strengths of their colleagues to support their work, even in cases where it meant admitting to weaknesses in their own ability. It was shown most explicitly when teachers sought help from each other without hesitation. Shelby, a new teacher in pre-k, was not afraid to ask questions to her colleagues when she needed help,

“They’re great. Because they’ve really kind of taken me under their wing, they’re really helpful. I can go to them for any questions. We talk all the time about different things and I’ll be like, ‘I need help’ and they’re like ‘Okay, let’s see about trying this.’”

Nolan also described how his skills and those of his colleagues complemented each other and that he felt comfortable drawing on this expertise if it meant helping a student.

“I mean, she’s [a colleague] very quiet and I’m not. I know that where I might have difficulty with a student just because my personality is more outgoing, she might have more success because her natural tendencies are another direction so it’s helpful for me to find those, find those points.”

This acutely demonstrates how open teachers felt with being vulnerable with their colleagues which attests to the feelings of professional safety and trust teachers felt within their community. Like Nolan, Taylor felt comfortable admitting she did not know something and asking for help. “I’ll send a desperate text being like, ‘Okay, I don’t get this,’ or ‘I don’t understand how to do this,’ and somebody’ll end up answering and helping me out.”

It seemed teachers at Highland Elementary felt secure to show their vulnerability to their colleagues whenever they needed help, and it was evident that every time they disclosed their vulnerability, their colleagues were supportive and facilitated their professional growth as a teacher, which contributed to teachers’ feeling of professional safety and trust.

Discussion and Implications

Given the unique setting of this study where data were collected close to the change of the administrative team, this study captured valuable perspectives. While the findings of this study echo the existing literature that emphasized the significance of trusting relationships for teacher development and school improvement (e.g., Kruse et al., 1995; Bryk and Schneider, 2002), it also shows how teachers build and sustain trusting relationships by sharing common goals and vision, building emotional safety and comfort, cultivating beliefs in colleagues’ competence, and being vulnerable, that allowed them to preserve their positive efficacy, social capital, and resilience, regardless of the instability of the administrator change.

Findings of this study also provide great insight to school administrators who may be transitioning to a new school. Although there are a limited number of empirical studies, the existing research focused on administrator transition identified that building trusting relationship and collaborative school-wide culture should be the top priority for incoming principals (Decman, 2005; Kosch, 2007; McCarty, 2007). As Clayton and Johnson (2011) study echoed, changes can only be effective when school leaders take time to learn, understand, and build the school culture. For staying and outgoing principals, it is important to establish an infrastructure that supports the development of nurturing teacher relationships as a way to enhance teacher well-being, but also to foster sustained feelings of safety and stability whether or not high-impact changes occur.

It is also important to note that the broken communication or lack of support might partly be due to the fact that the three former school leaders in Highland Elementary School neither left the profession nor voluntarily moved to different schools. Instead, they were asked to relocate without adequate preparation or advance notice. From a district level, this would suggest making collaborative and thoughtful decisions regarding administrators’ relocation in consultation with the schools and gauging the collegial relationship climate as information to guide the timing of administrative shifts. Districts often rotate principals as a way to improve school effectiveness, because principal rotation is expected to rejuvenate principals themselves and school staff, and bring fresh perspectives to tackle challenges in schools (Boesse, 1991; Hart, 1993). However, the evidence to prove the effectiveness of principal rotation is rather inconclusive and lacks rigorous empirical studies (e.g., Fink and Brayman, 2006). As Macmillan cautioned, “the policy of regularly rotating principals within a system is a flawed one, perhaps fatally so. When leadership succession is regular and routinized, teachers are likely to build resilient cultures which inoculate them against the effects of succession” (Macmillan, 2000, p. 68). In particular, when principal rotation occurs without carefully setting goals, understanding each school’s needs, and developing systematic support to facilitate communication between outgoing and incoming principals as shown in the current study, the abrupt and chaotic transition can cause frustration and instability for teachers.

Although the long-term effect of the transition at Highland Elementary School is currently unknown, findings of this study showed that when the administrative team changed without much preparation, despite the rough transition, trusting relationships among colleagues helped them to weather the storm. It seemed that the common goals and visions for students tied the teachers at Highland Elementary closely together to professionally strive for the best. Because of the shared vision for students, teachers valued each other’s expertise and believed in colleagues’ competence, which facilitated teachers developing trusting relationships. Such relationships provided teachers with a strong sense of emotional safety and comfort, as teachers knew that their colleagues are more than willing to help them in the case of difficulties. Also, trusting relationships allowed teachers to feel comfortable enough to be vulnerable, admit their weakness, and draw on their colleagues’ expertise, which in return further strengthened those relationships.

While this study presented valuable insights, there were also limitations in design. These limitations provide useful information about the design and implementation of future studies. First, as we did not collect data prior to the administration team change, we were unable to fully compare and track changes before and after the leadership shift. Incorporating a pre-post comparision design for future research investigating leadership transition and its impact would afford a fuller understanding of the impact of transition on multiple aspects of the school environment. Second, this study included one elementary school in the Midwestern United States, which has unique characteristics and contexts. Thus, the findings of this study may not be representative of all types of schools in different regions. A multi-site design which includes different school types and contexts may capture a wide-range of variations and commonalities. Despite these limitations, this study shows the power and significance of cultivating and managing trusting relationships and a collaborative school culture, as it facilitates the improvement of educational activities and processes for student learning, and provides stability for times of change.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets presented in this study are included in the article.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Oklahoma IRB Board. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

JH and DC designed the project and developed the conceptual framing of this manuscript. JH, QW, LL, AP, and CN collected data. All authors analyzed data through triangulation and contributed to writing and editing this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Boesse, B. (1991). Planning how to transfer principals: a Manitoba experience. Educ. Can. 31, 16–21.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). “Forms of capital,” in Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, ed. J. C. Richards, (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press), 241–258.

Bryk, A. S., and Schneider, B. (2002). Trust in Schools: A Core Resource for Improvement. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Bryk, A. S., Sebring, P. B., Allensworth, E., Luppescu, S., and Easton, J. Q. (2010). Organizing schools for improvement: Lessons from Chicago. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Clayton, J. K., and Johnson, B. (2011). If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it: a new principal is in town. J. Cases Educ. Leadersh. 14, 22–30. doi: 10.1177/1555458911432964

Creswell, J. W., and Plano-Clark, V. L. (2017). Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research, 3rd Edn. New York, NY: SAGE Publications.

Day, C., and Gu, Q. (2014). Resilient Teachers, Resilient Schools: Building and Sustaining Quality in Testing Times. Abingdon: Routledge.

Day, C., Sammons, P., Stobart, G., Kington, A., and Gu, Q. (2007). Teachers Matter: Connecting Lives, Work and Effectiveness. London: Open University Press.

Decman, R. S. (2005). A Study of Principal Priorities During the Transition Period (Publication No. 3173583). Doctoral dissertation, Northern Illinois University, Illinois.

Fink, D., and Brayman, C. (2006). School leadership succession and the challenges of change. Educ. Admin. Q. 42, 62–89. doi: 10.1177/0013161X05278186

Frenzel, A. C., Pekrun, R., and Goetz, T. (2010). Achievement Emotions Questionnaire for Teachers (AEQ-teacher) - User’s manual. University of Munich, Munich.

Fullan, M. (ed.) (2003). The Moral Imperative of School Leadership. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin press.

Fullan, M., and Hargreaves, A. (1992). “Teacher development and educational change,” in Teacher Development and Educational Change, eds M. Fullan, and A. Hargreaves, (Brighton: Falmer), 1–9.

Fuller, E., Young, M. D., and Orr, T. (2007). Career Pathways of Principals in Texas. Chicago, IL: American Educational Research Association 2007.

Goddard, R. D. (2003). Relational networks, social trust, and norms: a social capital perspective on students’ chances of academic success. Educ. Eval. Policy Ana. 25, 59–74. doi: 10.3102/01623737025001059

Golding, R., Taie, S., and Riddles, M. (2014). Teacher Attrition and Mobility: Results from the 2012–13 Teacher Follow-Up Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics.

Gu, Q. (2014). The role of relational resilience in teachers’ career-long commitment and effectiveness. Teach. Teach. 20, 502–529. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2014.937961

Hallinger, P., and Heck, R. H. (1998). Exploring the principal’s contribution to school effectiveness: 1980-1995. Sch. Effect. Sch. Improv. 9, 157–191. doi: 10.1080/0924345980090203

Hargreaves, A., and Fullan, M. (2012). Professional Capital: Transforming Teaching in Every School. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Hart, A. W. (1993). Principal Succession: Establishing Leadership in Schools. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Heck, R. H., and Hallinger, P. (2009). Assessing the contribution of distributed leadership to school improvement and growth in math achievement. Am. Educ. Res. J. 46, 659–689. doi: 10.3102/0002831209340042

Hong, J., and Looney, K. (2019). “Building and sustaining social capital: first year teachers’ sense of agency”, in Opportunities and Challenges in Teacher Recruitment and Retention, eds C. R. Rinke and L. Mawhinney (Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing). 3–23.

Hong, J., Greene, B., Roberson, R., Cross Francis, D., and Rapacki Keenan, L. (2018). Variations in pre-service teachers’ career exploration and commitment to teaching. Teach. Dev. 22, 408–426. doi: 10.1080/13664530.2017.1358661

Hong, J., Youyan, N., Heddy, B., Monobe, G., Ruan, J., You, S., et al. (2016). Revising and validating achievement emotions questionnaire - teachers (AEQ-T). Int. J. Educ. Psychol. 5, 80–108. doi: 10.17583/ijep.2016.1395

Hong, J. Y. (2010). Pre-service and beginning teachers’ professional identity and its relation to dropping out of the profession. Teach. Teach. Educ. 26, 1530–1543. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2010.06.003

Hoy, W. K., and Tschannen-Moran, M. (1999). Five faces of trust: an empirical confirmation in urban elementary schools. J. Sch. Leadersh. 9, 184–208. doi: 10.1177/105268469900900301

Huberman, M. (1995). “Professional careers and professional development: some intersections,” in Professional Development in Education: New Paradigms & Practices, eds T. R. Guskey, and M. Huberman, (New York, NY: Teachers College Press), 193–224.

Klassen, R. M., Bong, M., Usher, E. L., Chong, W. H., Huan, V. S., Wong, I. Y., et al. (2009). Exploring the validity of a teachers’ self-efficacy scale in five countries. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 34, 67–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2008.08.001

Klassen, R. M., and Chiu, M. M. (2011). The occupational commitment and intention to quit of practicing and pre-service teachers: influence of self-efficacy, job stress, and teaching context. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 36, 114–129. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2011.01.002

Klassen, R. M., Tze, V. M., Betts, S. M., and Gordon, K. A. (2011). Teacher efficacy research 1998–2009: signs of progress or unfulfilled promise? Educ. Psychol. Rev. 23, 21–43. doi: 10.1007/s10648-010-9141-8

Kosch, G. (2007). New Principals in a Turnaround Middle School: Analysis of the Transition Period (first 90 days) (Publication No. 3261825). Doctoral dissertation, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA.

Kruse, S. D., Louis, K. S., and Bryk, A. S. (1995). “An emerging framework for analyzing school-based professional community,” in Professionalism and community: Perspectives on reforming urban schools, eds K. S. Louis, and S. D. Kruse, (Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin), 23–44.

LeCompte, M. D., and Preissle, J. (1993). Ethnography and Qualitative Design in Educational Research, 2nd Edn. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press, 30–55.

Lee, J. C. K., Zhang, Z., and Yin, H. (2011). A multilevel analysis of the impact of a professional learning community, faculty trust in colleagues and collective efficacy on teacher commitment to students. Teach. Teach. Educ. 27, 820–830. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2011.01.006

Leithwood, K., Loui, S. K., Anderson, S., and Wahlstrom, K. (2004). How Leadership Influences Student Learning. New York, NY: The Wallace Foundation.

Leithwood, K., Patten, S., and Jantzi, D. (2010). Testing a conception of how school leadership influences student learning. Educ. Admin. Q. 46, 671–706. doi: 10.1177/0013161X10377347

Li, L., Hallinger, P., and Walker, A. (2016). Exploring the mediating effects of trust on principal leadership and teacher professional learning in Hong Kong primary schools. Educ. Manag. Admin. Leadersh. 44, 20–42. doi: 10.1177/1741143214558577

Liu, S., Hallinger, P., and Feng, D. (2016). Supporting the professional learning of teachers in China: does principal leadership make a difference? Teach. Teach. Educ. 59, 79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2016.05.023

Macmillan, R. (2000). “Leadership succession, cultures of teaching and educational change,” in The Sharp Edge of Educational Change, eds A. Hargreaves, and N. Bascia, (Brighton: Falmer), 52–71.

Macmillan, R. B., Meyer, M. J., and Northefield, S. (2004). Trust and its role in principal succession: a preliminary examination of a continuum of trust. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 3, 275–294. doi: 10.1080/15700760490901993

Mascall, B., and Leithwood, K. (2010). Investing in leadership: the district’s role in managing principal turnover. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 9, 367–383. doi: 10.1080/15700763.2010.493633

McCarty, C. (2007). The Transition Period Principals—The First 90 days: A Case Study (Publication No. 3278353). Doctoral dissertation, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA.

Meyer, M. J., Macmillan, R. B., and Northfield, S. (2009). Principal succession and its impact on teacher morale. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 12, 171–185. doi: 10.1080/13603120802449660

Meyer, M. J., Macmillan, R. B., and Northfield, S. (2011). Principal succession and the micropolitics of educators in schools: some incidental results from a larger study. Can. J. Educ. Admin. Policy 117, 1–26.

Plecki, M. L., Elfers, A. M., and Wills, K. (2017). Understanding Principal Retention and Mobility in Washington State. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Center for the Study of Teaching and Policy.

Sammons, P., Day, C., Kington, A., Gu, Q., Stobart, G., and Smees, R. (2007). Exploring variations in teachers’ work, lives and their effects on pupils: key findings and implications from a longitudinal mixed-method study. Br. Educ. Res. J. 33, 681–701. doi: 10.1080/01411920701582264

Schelvis, R. M., Zwetsloot, G. I., Bos, E. H., and Wiezer, N. M. (2014). Exploring teacher and school resilience as a new perspective to solve persistent problems in the educational sector. Teach. Teach. 20, 622–637. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2014.937962

Schutz, P. A., and Zembylas, M. (2009). Advances in Teacher Emotion Research: The Impact on Teachers’ Lives. Berlin: Springer Publishing.

Skaalvik, E. M., and Skaalvik, S. (2007). Dimensions of teacher self-efficacy and relations with strain factors, perceived collective teacher efficacy, and teacher burnout. J. Educ. Psychol. 99, 611–625. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.99.3.611

Sleegers, P. J., Leithwood, K., Peterson, P., Baker, E., and McGaw, B. (2010). “School development for teacher learning and change,” in International Encyclopedia of Education, eds P. L. Peterson, E. L. Baker, and B. McGaw, (Oxford: Oxford), 557–562. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-08-044894-7.00661-8

Strauss, A. L., and Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques, 2nd Edn. New York, NY: Sage.

Thomsen, M., Karsten, S., and Oort, F. J. (2015). Social exchange in Dutch schools for vocational education and training the role of teachers’ trust in colleagues, the supervisor and higher management. Educ. Manag. Admin. Leadersh. 43, 755–771. doi: 10.1177/1741143214535737

Thoonen, E. E., Sleegers, P. J., Oort, F. J., and Peetsma, T. T. (2012). Building school-wide capacity for improvement: the role of leadership, school organizational conditions, and teacher factors. Sch. Effect. Sch. Improv. 23, 441–460. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2012.678867

Tschannen-Moran, M., and Hoy, A. W. (2001). Teacher efficacy: capturing an elusive construct. Teach. Teach. Educ. 17, 783–805. doi: 10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00036-1

Tschannen-Moran, M., Hoy, A. W., and Hoy, W. K. (1998). Teacher efficacy: its meaning and measure. Rev. Educ. Res. 68, 202–248. doi: 10.3102/00346543068002202

Keywords: teacher capacity, trust, school leadership transition, teacher relationships, school climate

Citation: Hong J, Cross Francis D, Wang Q, Lewis L, Parsons A, Neill C and Meek D (2020) The Role of Trust: Teacher Capacity During School Leadership Transition. Front. Educ. 5:108. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00108

Received: 22 April 2020; Accepted: 05 June 2020;

Published: 10 July 2020.

Edited by:

Gary James Harfitt, The University of Hong Kong, Hong KongReviewed by:

Balwant Singh, Partap College of Education, IndiaGloria Gratacos, Faculty of Education, Complutense University of Madrid, Spain

Copyright © 2020 Hong, Cross Francis, Wang, Lewis, Parsons, Neill and Meek. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ji Hong, anlob25nQG91LmVkdQ==

Ji Hong

Ji Hong Dionne Cross Francis

Dionne Cross Francis Qian Wang1

Qian Wang1