- Leeds Beckett University, Leeds, United Kingdom

As black women leaders within the 21st century sharing our stories, reflections and contributions remain an area of high anxiety, reluctance and resistance. The fear of these contentions can elicit feelings of invisibility, voicelessness, rejection and reprisal. Black women’s experiences of leadership are, at times, visualized metaphorically as a single bare thread. A thread that maneuvers and meanders aimlessly, not through choice, but by navigating their way through institutional systems. Their journeys are fueled with micro aggressions, convoluted racial barriers and systemic obstacles placed within their paths while attempting to reach and sustain their leadership positions. In her research (Curtis, 2014, 2017), has sought to connect these threadbare yet bonded experiences by weaving the participants counter-narratives into a collective quilt. A quilt designed and developed to show their stories of leadership. This methodology displays their strengths and commands visibility while displaying vibrant, passionate social justice leadership within these symbolic colorful, tired and tangled yarns. Black women’s survival in leadership positions is often not one of centrality within mainstream literature. These experiences are not commonly championed or celebrated by those who hold dominance within society. However, within this research, black women’s survival is one in which their resilience hangs solitary at times by a threadbare yarn. Using these threads to authenticate connectedness and weaving their journeys of leadership has utilized a bond and created an opportunity to share with other black women leaders their often isolated experiences. The research expands their expressive, creative liberation using the lens of Critical Race Theory and black feminism to explore the women’s cultural identities as educational leaders.

Introduction – Black Women’s Leadership

Despite the lack of representation of black women as leaders, history shows that they have managed to become successful leaders in many disciplines and have been able to maintain their positions (Alston, 2005; Bass, 2009). Black women have historically diverse strategies for survival and for maintaining their emotional wellbeing (Maddox, 2013). These leadership experiences have created a collective identity for the women, one that seeks to work beyond the traditional expectations of leaders, and which seeks to provide a sense of community, support and development.

This journal article is an opportunity to present the strengths demonstrated in black women leaders’ collective presence while sharing their collective voice. The dominant discourse contained in the wider body of management and educational research presents a patriarchal view of leadership, and this partial view is recognized by the silence of women’s voices in research, as well as those who are marginalized and excluded as the ‘other’ (Lorde, 1984). Those who work toward eradicating oppression and inequality have developed a shared understanding of marginalization and have been seen to adopt a race-centered approach to their leadership (Gillborn and Mirza, 2000; Santamaria, 2013). CRT sets the context within an ahistoricism that has dominated empirical research by minimizing the academic space in which alternative histories could be told (Gillborn, 2008; Roberts, 2013).

Black women’s identities are described as multifaceted, and are presented in the literature from a dominant viewpoint which Maya Angelou (cited in Bush, 2000) has termed the ‘fabulous fiction of black women’s identities.’ This description highlights the stereotypes of black women which are highly gendered or depicted as contradictory representations, and presents a view from a very different lens. Bush (2000) describes how this conflicting representation of black women shows inconsistencies and racist stereotypes of black women. However, within this research, by relating a shared understanding of the women’s experiences; the researcher shares the sentiments as expressed by Bell-Scott who states:

“When you share our stories and seek to unshroud the lives of women who have come before us, the telling empowers us all” (Bell-Scott and Johnson-Bailey, 1999, p. xiv).

Non-traditional writing genres have been used by black feminists, as well as by critical race theorists (Alexander-Floyd, 2010), to give voice to those who are marginalized and excluded. By exploring the intersections of race and gender, this method provides the freedom of collectivity in the safety of a created black women-centered space. Curtis (2014, 2017) reveals how black women, normally isolated from each other, share their experiences, which include the daily barriers, struggles and adversities that have helped to shape collective identities (Shelby, 2002; Bass, 2009). Within educational research, Witherspoon and Mitchell (2009) examined the neglected notion of black women in educational leadership, and revealed that black women’s experiences had been silenced by other, more dominant leadership narratives. According to Johnson (2012) and others, black women often adopt a tenacious, resilient model of leadership which has remained absent in mainstream research (Alston, 2005; Patterson and Kelleher, 2005; Johnson, 2012). This method presents their voices by sharing counter-narratives that examine their cultural wealth and knowledge by acknowledging different practices and analyzing histories (Delgado and Stefancic, 1995; Solórzano and Yosso, 2001; Villapando, 2003).

Traditionally, quilting is embedded in women’s everyday lives, and has been used to document a rich history (Wilson, 1999). This method helped to complement feminist values that include a historical context for social and political redress (Johns, 2011). The history of quilts has been traced back as far as ancient Egypt and China. Quilt-making traditions have given women the space to be together, to find their voice and to share their feminine knowledge (Alexander-Floyd, 2010). Black women leaders need to be empowered to tell their own stories. This also supports the notion that:

“Stories give the opportunity to re-theorize Eurocentric and patriarchal frameworks, with a focus on the liberation of people of color from the historical legacy of colonization and the hegemony of white society” (Rodriguez, 2006, p. 1071).

Stories are powerful tools used to readdress these imbalances and the inequalities faced by those whose voices have been stifled into silent submission. The research process includes five phases (discussed within this article). The third phase of the research was the development of the quilt. An emergent stage influenced through the impact of their shared counter- narratives and the powerful transference of their stories that influenced the fluidity of this critical phase.

Theoretical Framework

Critical Race Theory (CRT) sets the context in this research (Curtis, 2014) to incorporate the history of black feminism and the understanding of the various forms of oppression experienced by black women. Further exploration examines some of the commonalities black women share as women; however, the overlapping intersections of race and gender have affected black women’s leadership experiences, as highlighted in this journal article. The concept of CRT and its application provide a standpoint that effectively establishes a critical framework for this research (Hooks, 1990): a framework that demonstrates a culturally sensitive approach that explores the influence of race and gender.

Critical Race Theorists have challenged educational institutions in regard to issues of inequality, privilege, and color blindness (Delgado and Solórzano, 2001). The ideas of fair play, equality and democracy devoid of the significance of ‘race’ support the notion of a color-blind approach. Color blindness as challenged by CRT theorists is the idea that race and the effects of racialization are not considered in education. This absence renders policy and practice void, because of the belief that we all have an equal chance starting from the same point in life, including equal access to employment and education, disregarding any systems of inequality and discrimination (Gillborn and Mirza, 2000).

The main reason for choosing to use a black feminist research methodology was to ensure that the method enables the black women leaders to be visible narrators of their own counter-narratives of their own lived realities, as expressed in their own voices (Delgado, 1989; Matsuda, 1989; Solórzano and Yosso, 2001).

Bell-Scott and Johnson-Bailey (1999) looks at the use of narratives, journals, poetry and quilting, as well as a number of other useful media resources that are instrumental to the black women she believes are struggling to find their voices. This positive approach to CRT as used within this research includes the promotion of storytelling. Adams-Wiggan’s (2010) study supported the value of counter-stories. Her work has focused on black professional women and their experiences of biculturalism. She studied the effects on these women emotionally, professionally and personally. Through counter-story telling, she allowed the participants to voice their own realities, sharing sensitive data on the impact on their daily lives caused by living with this internal and external conflict. Delgado (1989, p. 2439) asserted that only through listening can the conviction of seeing the world in one way be challenged: “one can only acquire the ability to see the world through others’ eyes.”

Curtis (2014, 2017) aimed to capture the women’s thoughts, their thinking and some of the essence of their identity through their eyes, by the production of a visible, collective leadership quilt.

Who Are These Leaders in This Research?

The sample consisted of eight black women: Amara, Aaliyah, Esther, Eleanor, Tallah, Michaela, Estella and Carmen. Individually (stage 1 analysis) and collectively (stage 2) they explored their experiences with regard to their leadership journeys and developments. When designing the research, it was intended that the women would be self-identified black women working as Children Centre leaders, or curriculum leaders providing services for children up to the age of five. As the research progressed, other types of leaders emerged, this also seemed relevant and consideration was given for their inclusion in the research sample. As part of the recruitment and selection a number of organizations were contacted, including professional black women’s establishments, such as the Black Women’s Leaders Network and the NPQICL (National Professional Qualification in Integrated Centre Leadership), and also including newly qualified black women leaders as well as the Black Women Voices network based in London at that time.

Introducing the Research Participants

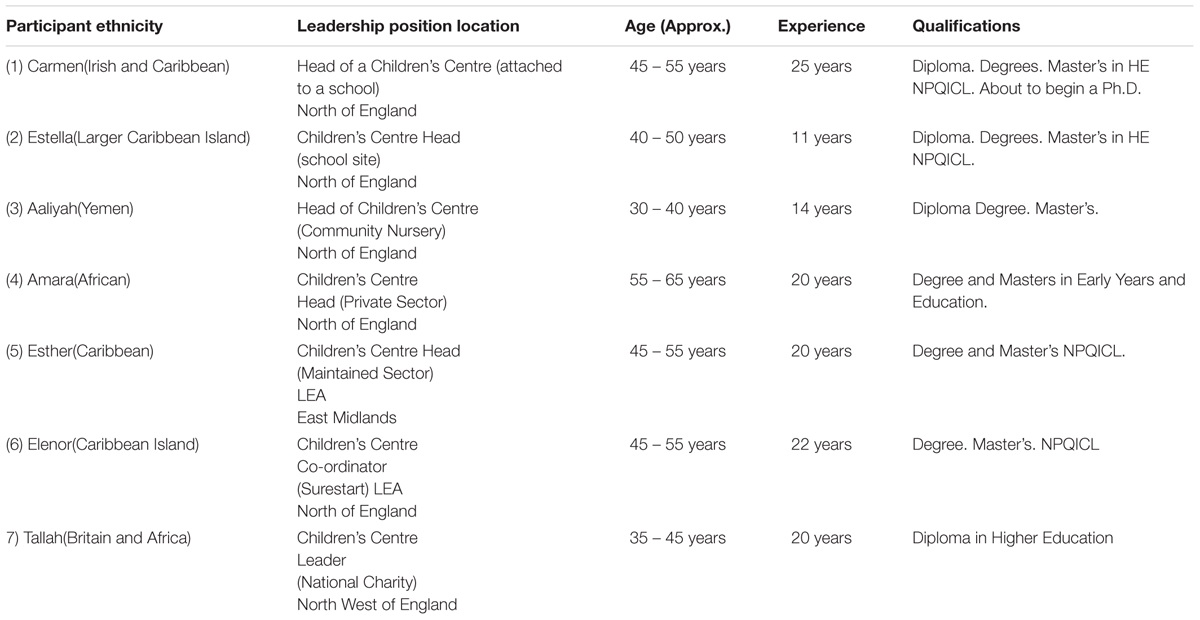

The eight participants have different backgrounds, including their ethnicities, ages and experiences; however, some of the commonalties are shown as follows (see Table 1):

Table 1. The eight participants and their leadership experience, heritage, locations and level of leadership.

The women in the study’s average experience in leadership is between 15 – 20 years.

The participants came from diverse backgrounds but all identified themselves as black the majority came from various Caribbean islands. The Women have also completed a degree and six leaders have completed their Master’s degrees in education. These women are well established leaders with many years of educational leadership. The following section will show how the research methods have been used and will provide the opportunity to examine the data. This article will present the 2nd stage of the data analysis.

Data Collection and Methodological Approach

The research design for this study incorporated qualitative research techniques that enabled the researcher to extract aspects of the participants’ leadership experiences that have not been well-documented in the current literature (McCall, 2005; Campbell-Stephens, 2009; Johnson, 2012; Santamaria and Santamaria, 2012). There are clear underlying principles that have guided the methodology in support of a Black Feminist epistemology that steers away from generalizations and is, therefore, set within the context of a historical ontology (Delgado and Stefancic, 2001).

The traditional feminist approach in which black women did not have a voice has attracted some contention with regard to the use of methods and the arguments for having a feminist methodology. Hammersley (1992) concluded that this methodology was not distinct from non-feminist research, and had drawn on many of the ideas already in existence within non-feminist literature.

“Much feminist theory emerges from privileged women who live at the center whose perspectives on reality rarely include knowledge or awareness of the lives of women who live in the margin” (Hooks, 1984, p. 1).

As a theoretical framework, black feminist thought supports the use of qualitative methods of inquiry (Hooks, 1984; Collins, 1990). Adjustments taken from the pilot have been made to the semi-structured interview (divided into two interview schedules). The interview at the pilot stage had numerous questions, causing the interview to exceed the 2-h time limit. Adaptations have also been added to the methods by interpretative critical analysis using triangulated methods to ensure the representation of a rich tapestry of findings that exemplify the experiences of a cross-section of black women leaders nationally (Johnson-Bailey, 1991; Gibson and Abrams, 2003). Research shows that a triangulated approach to the study (Denzin, 1989) helps the researcher to compare the findings through the use of various approaches. This approach used throughout the five phases has given a more comprehensive insight into the main issues that affect black women leaders. The research design focused on three research questions; however, in this article I will present the data collected and related specifically to question one:

(1) What experiences are black women leaders encountering in achieving leadership roles in early years education?

The five phases are as follows:

• Initial one-to-one interview – this is an introductory interview to find out their individual timelines and journeys, their backgrounds and their personal developments.

• Walk-and-talk interview – this was an introduction to their work settings presented in their early years’ centers, as well as an opportunity for an introduction to their team.

• Final one-to-one interview – the opportunity to revisit their transcripts, to share their experiences of the research in the design of the quilt and their reflections as leaders.

• Presentation of the quilt – a two-way process in which the researcher presented the women with the completed quilt and for the group to express their final thoughts as a collective and as individuals.

• Final interview – a last opportunity for individual participants to collate their final thoughts and to share advice for new black women leaders.

As race and gender were central in this research, it was important to look critically at the impact on the data analysis presented through the lens of a black woman researcher engaged in a participatory relationship researching the experiences of other black women.

Using Reflexivity With the Researcher as an Insider or an Outsider

By demonstrating the richness of reflexivity in this research further opportunities are provided to engage in the understanding of these women’s lives as leaders. Reflexivity is seen as an increasingly popular methodological self-consciousness that gives qualitative researchers a new paradigm (Seale, 1999, p. 160). This process offers the opportunity for the researcher to be willing to learn about his- or herself and to explore the purpose of the research and his or her positionality within the social world (Brown, 2012). As the researcher listening to these stories, their words touched upon my internal reflections while encouraging me to examine my own journey through the process of analyzing the women’s stories. Bell (2003, p. 16) believes that ‘Stories are one of the most powerful and personal ways that we learn about the world passed down from generation to generation.’ I should share that, when I was first asked to explain my research, I placed the emphasis of my work collectively on “all women” in leadership. My awareness at that time was that this seemed to receive a more receptive, response within the sector. A degree of safety was created by the generic use of the word “women” in leadership. However, I am now consciously aware that burying issues of race is about not creating waves and being “othered” by dominance (Collins, 1990) or labeled as “one of those people” who raise difficult conversations.

Choices not to speak are often well-intentioned and psychologically protective, motivated by concerns for people’s feelings and by an awareness of the realities of one’s own and others feelings’ (Gilligan, 1993). CRT and black feminism empowered me to place race firmly on the agenda. Bell (2010, p. 4) clearly expresses that race matters, ‘it provides a roadmap for tracing how people make sense of social reality, helping us to see where we connect with and where we differ from others in our reading of the world.’ Collins (1990) highlighted that black women need to relate their lived experiences through their own culture and set within their own contexts that moves away from the deficit models of research that included stereotypes. Gibson and Abrams (2003) had shared views as one black and one white researcher whose study engaged black women in qualitative research, and revealed that:

“We consider it our responsibility to examine our own perspectives and experiences as insiders and outsiders who collect and relay stories about black women’s lives” (Gibson and Abrams, 2003, p. 491).

Being open and self-aware of the impact of this work has been just as important in my role as a researcher, guided by using my intuitive self-reflection (Rogers, 1986). Particularly, as the researcher, delving into each of their individual stories and by critically moving throughout the five phases of research and analysis.

The Thematic Findings

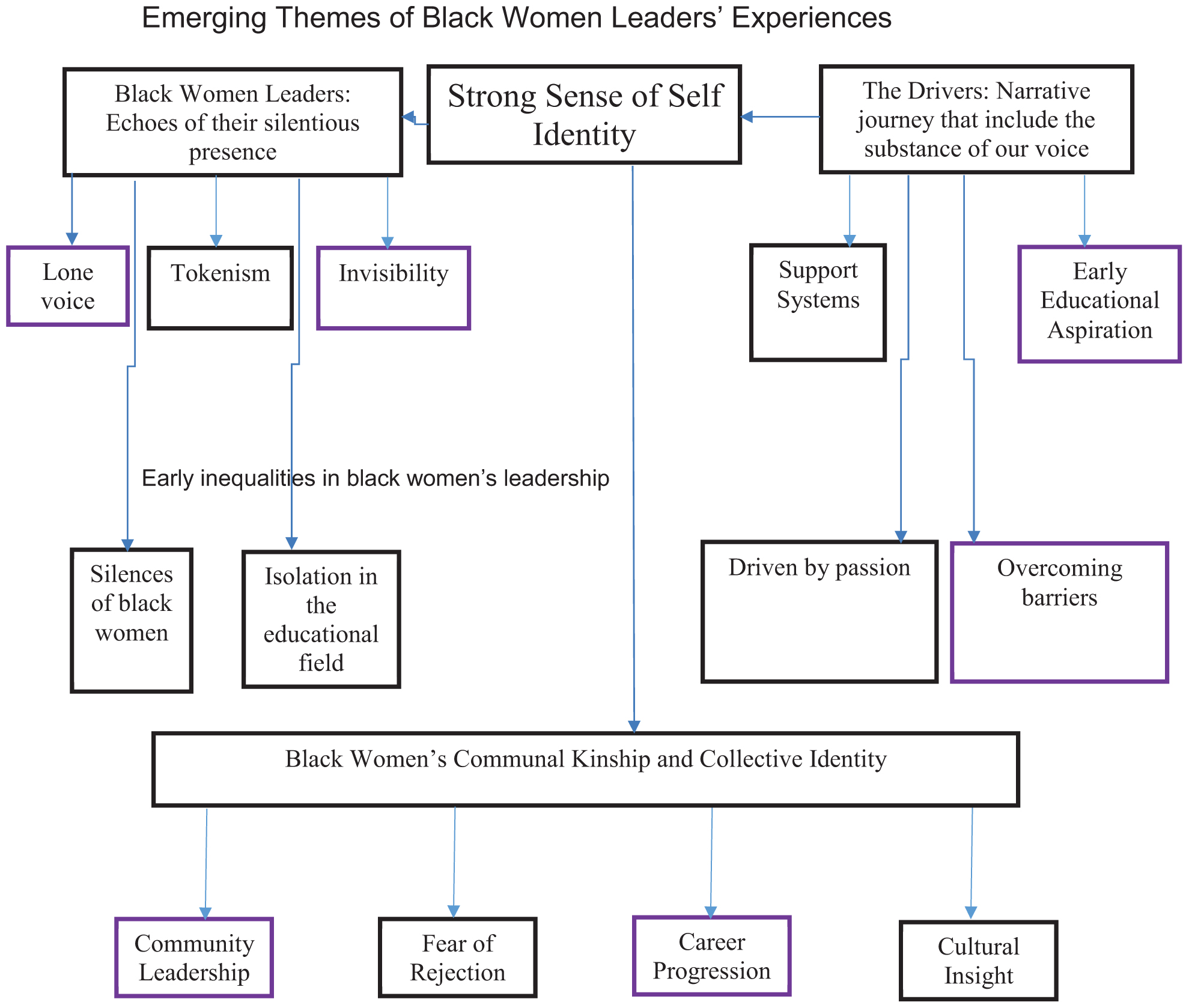

A total of 16 one-to-one interviews took place and all have been transcribed and coded. In addition to the use of eight walk-and-talk interviews in which a tape recording and notes were taken on the day. Supported by the transcription taken from the two focus lasting approximately 4 h with an hour’s break for lunch. The five phases was completed after a period of 18 months. The 14 identified themes highlighted below (see Figure 1) have been refined by further thematic analysis (in stage 2) of the collated data. This article combines these refined overarching themes and presents these three concise themes to represent the participants’ experiential knowledge as follows:

(1) Echoes of their silentious presence – have been described by the Women in their journeys as one of representing a silent presence in which these women represented as tokenism or completely invisible, silent, lone voices, isolated in the educational field.

(2) The drivers – and their narrative journeys – the women describe their personal drivers as their aspirations to stay in the field overcoming barriers, attending meetings and working on panels, and higher leadership positions and how they have striven to create their own supportive networks.

(3) Communal kinship and collective identity – The ability to work as social justice advocate and commitments given to the community using their cultural insights and cultural competence to provide services that deal with issues of race, and the importance of their strong sense of self.

Focus Group One – (Quilt Development: Phase 3)

At this stage in the research, the participants had completed the first two phases of the data collection, which included the initial interview and their walk-and-talk interview. Focus groups have a collective nature, providing collective power to marginalized people, as well as for feminist activists. They are used successfully in social science and in cross cultural research (Liamputtong, 2011). Madriz (2003) used focus groups as a methodology, as a means to advance her cause, creating data from women’s voices and providing safety in order to give the group the opportunity to share, and for the researcher to obtain richer information. It felt important to give something back to the participants for their commitment and involvement in the research. Each participant was given the opportunity to design a small quilt patch that identified their own values in leadership. The process used to produce the quilt has varied slightly in the production, in that the women designed their quilt patch, but did not physically sew the quilt together. The researcher, through her own family values and traditions, engaged the help and support of her aunt in Nova Scotia, an experienced quilt-maker, who agreed to support their ideas and designs and complete their work. The process was time limited and involved a community of committed quilters in Canada. On its completion, 7 months later, the researcher traveled to Canada to collect their collective narratives and stories of leadership. These women built a bond through participation and involvement in this research, and it evoked a shared, empathetic understanding.

The Artifact: Introducing the Facets of Their Leadership

As an ice-breaker, the women were invited to a central location for the first focus group and asked to bring with them an object of their choice, an object that they felt would symbolize their leadership, and that represented facets of who they are as leaders. Potential risks were possible as the result of taking them from their own safe spaces and having them meet each other face to face in a new unfamiliar space. I demonstrated the use of an artifact as a means of introduction as I shared my own artifact, which represented my own distinct traits in my leadership role within the group.

“The making of meaning is an inherently therapeutic activity as well as a qualitative research activity. This caring concept, therefore, bridges the line that some authors attempt to draw between the researcher and participant” (Kahn and Eide, 2008, p. 202).

Each participant was given the opportunity to contribute to the discussion, and only two of the women hesitated before proceeding. This article shares Carmen’s object, who brought with her a pyramid-shaped paperweight. This was a transparent object containing blue liquid with a variety of differently colored bubbles floating inside. She explained:

I brought this as my artifact because I was thinking… that it was more than just a pyramid. You have got the base, but you have to reach up to the top! If I’m at the top, how have I got there?

Stable foundations are important in leadership; thus, Carmen describes the importance of being able to reach up to the top. She did not choose a solid object, but chose one that was clear and transparent. In her leadership role, there are tensions in regard to her position; she used the metaphor of the perilous glass lift or escalator in the ascendancy to her leadership position. More importantly, she shared her journey, and was able to trace systematically how she reached her position of leadership. In the focus group Aaliyah also shared her understanding by using the glass metaphor when she said that the ‘glass ceiling represents the fact that you still have got to break through a glass ceiling in your difficult journey.’ Similarly, the view adopted by Crenshaw (1991) shares this metaphor as one of social disadvantage. The question she asks is: if you manage to reach the glass ceiling which woman makes it through the trapdoor? These visual metaphors illustrate how some groups can see other people’s routes to success at the top, but are unable to join them on the glass escalator. Bagilhole (2006) suggests that the glass escalator means that some women see others going up, but are not sure how to get on. Black women leaders, therefore, need to elevate themselves by ensuring that they become careful, skilled communicators, creating strong, strategic networks to enhance their skills, and by not being afraid to promote their own work. Carmen is comfortable sharing her journey using the pyramid and feels she has had some success. The other women share this commitment through similar stories that emphasize the significance of managing “race” and ethnicity in their daily work:

I’m a head teacher, who just happens to be black, and I’m very aware, but sometimes you have to make that clear, and also our multiple identities. (Estella)It is a unique question about which camp do I sit in because of the color of my skin. (Aaliyah)

Historically, racial and gender discrimination have been described separately within social research. More recently, race and gender issues have been interconnected; however, a more critical understanding of black women leaders’ experiences for this research has to include the various intersections of identities (Crenshaw, 1991; Collins, 1998). Esther clearly struggles with the rejection as a black female leader and states:

Within the education system which doesn’t allow for anybody else who is not personally invited to join “our gang”: so where do the black women fit within this structure? (Esther)

The women shared their various stories of difference that included their race, their class, their understanding and valuing of their religion, and their complex identities. Such shared and common values define the group by constituting its ‘distinctive character and self-conception’ (Shelby, 2002, p. 237). Earlier discussions during their initial introductions were referred to and Carmen made a connection with the group when she stated that, as black leaders, they do not actually fit into the “traditional boxes,” Carmen feels that she remains an outsider. The group supported Carmen’s feelings of exclusion: ‘For me, it’s proving who I am and what my purpose is and my purpose is and always will be maintaining my principles throughout and my integrity’ (Estella). ‘And it’s the constant thing of proving yourself… like all throughout life I’ve shown myself to be different and it’s good to be different!!’(Aaliyah).

Collins (2000) is clear that these tensions shared in their narratives can represent a common standpoint. Community cultural wealth viewed through the lens of CRT, as described by Yosso (2005), highlights the positive contribution that leaders develop from ‘the array of cultural knowledge, skills and abilities possessed by socially marginalized groups that often go unrecognized and unacknowledged’ (Yosso, 2005, p. 69). Estella’s description of her working environment attributed her thoughts to her own culture and the incongruence she felt when working in an environment that she described as incompatible, unaccepting and causing her to feel oppressed. Kvasny et al. (2005) echoed these feelings when stating:

“You experience the subtle and not so subtle forms of gender, class, racial inequalities that can’t but make you perceptive. You see and feel things that others can’t recognize, yet you are constantly reminded of your otherness” (Kvasny et al., 2005).

The focus group created the opportunity to connect their feelings of otherness and to gain validations in relation to their intersectional complexities and the impact this had on their psyches. Each participant took their turn and shared their object before meeting again to unveil the quilt.

Unveiling the Quilt

This was the fourth phase of the research (an emergent phase), Esther shared that she had never had the opportunity to sit with black women leaders as she had experienced during the first focus group, and was “blown away” by the stories shared. She wanted the others in the group to know that ‘bwoy that first group encounter had touched me in so many ways.’ Amara’s heartfelt reflection shared openly was very different to the rest of the group, as she is the owner of a private daycare:

I am fortunate that I don’t have to be harassed, bullied and accountable to anybody, and so I feel for these women (sigh) who give a lot of time. I mean, one of them was even saying that she got ill, and went into work so no one would know… and I didn’t think things like that existed. (Amara)

The morning session of the second focus group had given them the opportunity to re- group. Their feelings in the room were of high spirits, rekindled experiences and a shared understanding of each other’s stories.

“It is often within groups that persons who would normally not feel comfortable voicing their views or concerns come together in strength and with new possibility for action” (Meyerson, 2003, p. 121).

The afternoon session began with the women in jocular spirits, lively and upbeat. I took this opportunity to go and collect their individual photos of their quilt patch. As I began to leave the room to collect the photographs, the women spontaneously decided to sing. One of the women began to play the piano that was situated in the room. As I walked along the corridor, I heard the melodic sounds of “reach out and touch.” When I re-entered the room, the women were shaking each other’s hands almost as a gesture of camaraderie. Shelby (2002) explores the notion of group solidarity and sees this as a tendency of the group members to identify with each other, or with the group as a whole.

A small discussion took place regarding their eagerness to see the quilt. As Estella expressed, ‘I’m looking forward to seeing it… how it looks.’ The emotional time and space within this particular moment was important and acknowledged by the depth of the emotions that mingled in the room. Earlier that day, one of the women had tearfully shared a personal loss of a close loved one, but explained that ‘I just felt I had to come.’ Another personal thought and reflection verbalized by Esther was ‘can I carry the load much longer in my work?’ Even those who had pressing concerns in the real world outside this space made the decision to remain and to share in the unveiling. As the researcher, I had certain expectations, but I was not prepared for the immediacy of the silence that fell as all eyes turned toward the quilt as it was unveiled. Although I had asked for a moment of reflection (this was first to gather my own thoughts), I turned to see many tear-filled eyes, and expressions of amazement as well as bewilderment. At this time, the participants echoed that they found it difficult to speak, something that had not been hard for this group of individuals before now. The room was hushed and reticent and the participants’ voices had become shaky and incoherent. Slowly, after a period of time, the women were able to move from their chairs to go over and to touch the quilt in its entirety.

The group then began making the connections around their own individual stories and journeys. Carmen turned to me and said ‘Do you know what you have done?’ I felt that this was a rhetorical question and I thought it was important for the space to continue so that the women could gather their feelings. As a result of the work, the women felt a much stronger connection than the first time they met, describing each other as friends, exchanging lots of hugs and reassuring touches, in addition to sharing a box of tissues by the end of the day. This experience Shelby (2002) describes as having a special bond, in which each of the women could identify with a fellow group member seen as an extension of themselves. In support of this extension and unspoken sense of relief, Patricia Bell- Scott in Flat Footed Truths shares the depth of their emotions as she says:

“There was so much longing and relief, grief and joy, in our silent tears: Relief that the silence was being breached, longing for all the life stories forever silenced. We were grieving with and for our foremothers for the creativity so many were unable to express” (Bell-Scott and Johnson-Bailey, 1999, p. xv).

This powerful “collective consciousness,” derived from an ancestral feel presented a real sense of their foremothers past and present, was tinged with joy by the release of their tears that are so often hidden. This collective consciousness described by Collins (2000) refers to black women coming to terms with their lived experiences, a shared understanding of group dynamics and recurring situations. This can be seen as issues passed down through generations by creating new counter- stories through, art, music and religion (Few et al., 2004). The collective group identity gave the women the safety to exhale and support each other as part of their communal kinship.

A New Era – Collective Voices and the Quilt Analysis

The quilt developed in this research created the opportunity to view a wider vision and a shared collection of voices surrounding the experiences of black women leaders in early years’ education. In hearing these women’s stories, primary methods of data analysis were applied after the transcripts had been manually coded (Strauss and Corbin, 1998). This coding was applied by linking key concepts and related experiences of leadership from black women through the literature review. The research process also involved returning transcripts and discussing the narratives presented with the participants for their approval, as well as to seek further clarification. The use of selective coding (Strauss and Corbin, 1998) to analyze the data was applied. The 14 themes identified by the women express their lone voices and their isolated experiences in groups and in education. In the stage 2 data analysis, the women revealed their spirituality, sharing strong aspirational messages received in their childhood and their own identified support systems that have maintained their resilience through their strong sense of self-identity in order to survive.

However, after candidate six, it was clear that in being insightful and knowledgeable about their communities, and that their drivers to continue were their passion for the work, two more emergent themes were added to the key, namely cultural insight and driven by passion.

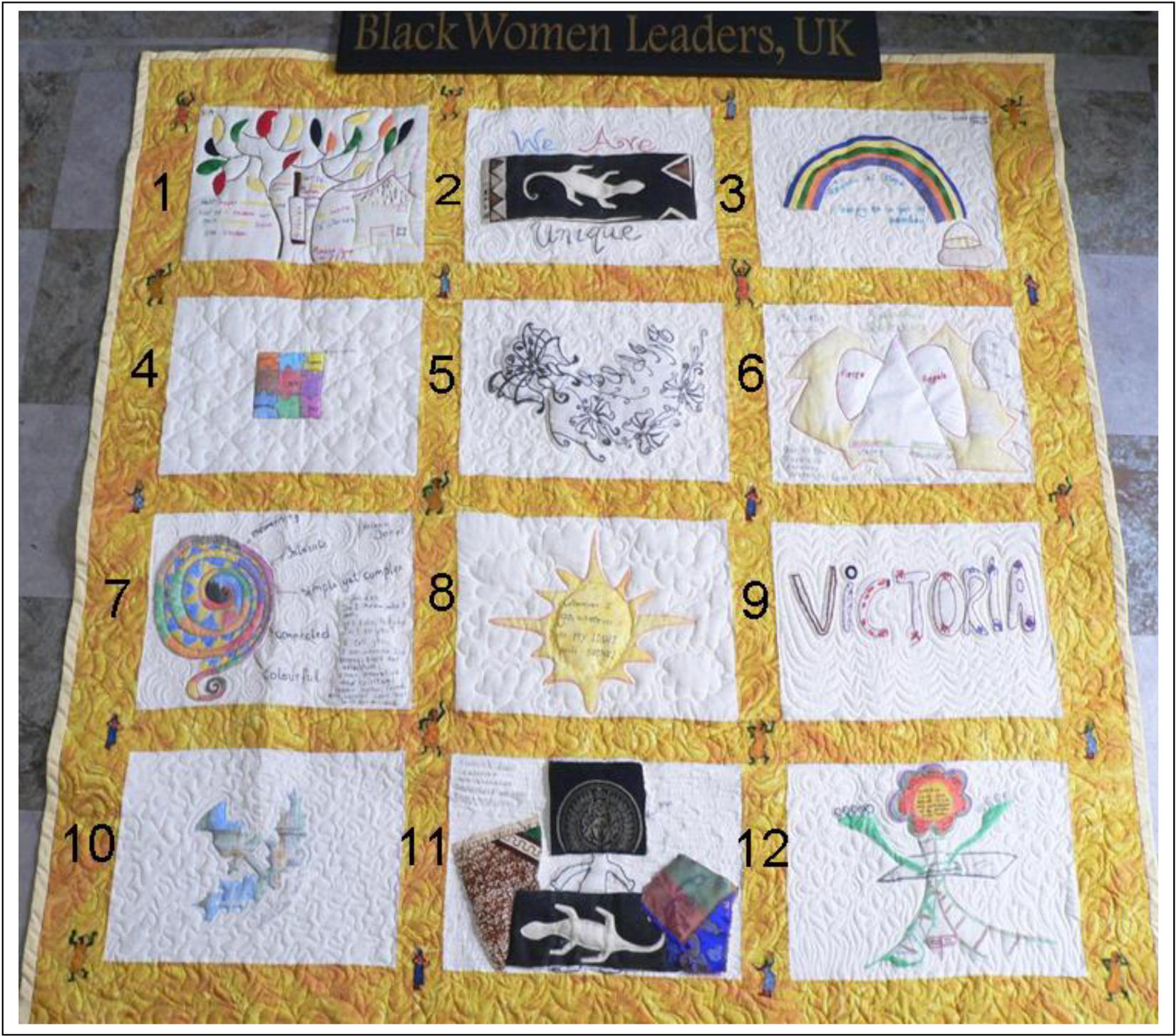

The final panels reveal the women’s own journeys, which combine their flavors of the Caribbean, Asia, the Yemen, India, Europe and Africa. The quilt-maker’s own stamp has been added in completing this collective identity, which includes a cross-cultural understanding of Jamaica and a national dimension representing Canada, using Scottish tartan to highlight Nova Scotia (see Figure 2). The creation of a quilt gave the women the essence of a tradition which was, at that time, symbolic of care. Estella and the other women have described their leadership and the importance of this as carers and nurturers: ‘I really do care about the job that I do and as a leader I hoped that that would come through.’ The women shared their understanding of the quilt, and Carmen, Estella and Aaliyah felt:

Figure 2. The quilt. Square creators and themes: (1) Esther, Home of strength. (2) Amara, We are unique. (3) Eleanor, Rainbow of hope. (4) Tallah, Jigsaw of love. (5) Michaela, Butterfly of growth. (6) The Researcher, Fierce angels. (7) Carmen, Colorful and descriptive. (8) Estella, The big sun. (9) Non-participant. (10) No theme. (11) Non-participant, no theme. (12) Aaliyah, Two journeys.

There is vibrancy to the quilt: it feels full of life,[it] shows energy, the colors are bright and engaging. (Carmen)I feel a representation of earthiness, something wholesome and warm. (Estella)I see the tree, the rainbow and puzzle: they are all representations of growth and new life. (Michaela)

The completion of this quilt helped to give more depth and understanding to their world. Some quilts can give clues to the past, some quilts provide a sense of heritage, whilst others give enjoyment, color and a sense of completion (Frye, 1983; Higgs and Radosh, 2012; Koelsch, 2012). This quilt demonstrates the weaving and constructing of the leaders’ common values, expressed within this article. It seems that stories encourage creativity, assist in dealing with emotions and help to make sense of puzzling situations (Allan et al., 2002, p. 10). An important analytical thread of identity and self has run throughout the research, drawing together each sub-theme. Quilts represent warmth as well as comfort, but, more importantly for this research, they are a visual expression of the women’s leadership. Collective experiences represent the historical, political and cultural positionality of black women; the women in this group have shared their experiences of race, gender, isolation and segregation in the educational field (Beauboeuf-Lafontant, 2002). However, one of the benefits of this research has been the freedom of expression. This freedom of expression is a means:

“to connect with other women, to celebrate and appreciate connections with women who have produced quilts in the past, and to experience tension relief and self-renewal; the quilting process is central to resistance to the identity-stripping elements of contemporary life” (Stalp, 2001, p. 20).

The collation of this quilt was an intergenerational achievement, with strong family connections personally for the researcher, and the final touches interwoven with the wisdom and experience of an experienced quilt-maker. Smith (1997) is clear that, through diligent efforts, the quilt in all its forms is gaining acceptance as a serious medium (Smith, 1997, p.5).

Throughout history, quilts have been enjoyed for various reasons. Estella stated:

Really for me there is no doubt that the representation was from black women. OK.… Collectively, I see black women’s strength. I see lots of different journeys; people have come through very different journeys. I see hope and I see common threads as well… someone who sees potential in other people going through there.… Courageous black women and… really… resilient women. (Estella: 8th square)

Their connectedness in the group when completing this quilt, and the power of their stories, alongside their shared experiences as black women leaders, presented a wider collective voice to the research, as they co-operated in interweaving and connecting their own strands of the story.

“Through the quilt the voices of the past survive, the stories trace a path of connections between oral traditions, storytelling, the invention of meaning, and the preservation of cultural memory” (Barrett-Ferrier, 2007, p. 27).

Aaliyah’s quilt patch is a large colorful flower (12th square); she was careful and concise when she explained:

I have done two different stems. They don’t join in the middle. There is not a choice, so you start off in the direction of a difficult path, but the end premise is you can go to the top. Of course it is a difficult journey, but you will get there, albeit by having to take slightly longer steps. The thing in the middle is the glass ceiling: it can be broken and you can continue above. (Aaliyah: 12th square)

Aaliyah is clear that her path has lacked the privileges of access and opportunity and she understands why her journey will be longer, harder and tougher, but she has the stamina and resilience to get there. Gabriel’s description of storytelling is that it is seen as ‘an art of weaving, of constructing the product of intimate knowledge’ (Gabriel, 2000, p. 1). This knowledge presents their hopes, spirituality and drivers and the strength of their resilience in their leadership journeys. These celebratory threads have linked these women’s past journeys, as Amara explained:

I think I see a collective response really. That’s what I see. I don’t know what to say at the moment and in relation to what I have written here… it’s amazing… (very softly) it’s amazing. (Amara)Do you want me to talk about what it means to me now at this stage or what I just think of what I did? I think, looking at all of that energy that is there and what we are doing here, this has given me so much hope… I’m sorry, I can’t talk coherently about this at the moment. (Eleanor)

Amara and Eleanor were touched by what they saw. Esther tried to share her thoughts:

Looking broadly at some of them, it is the journey, and I think a lot of the people’s squares represent a journey. The one in the middle feels like it is similar to mine as it represents going through life and growing, and again the one with the snaky pattern on it, and I think, just looking across the board at the different people, [they] are all about our work and going on. (Esther)

This collective identity reveals thread by thread the combined, mutual and co-operative stories of their experiences of leadership. Carmen (7th square) asks in her quilt patch ‘You ask do you know who I am? (She replies) yes I do, but who am I to you?’ (Quilt patch number 7). Carmen is clear that she knows herself well, but do others see her as she sees herself?

The quilt was used for the purpose of extracting quality data through building and maintaining a trusting alliance between the two parties (Hayman et al., 2012). Tallah made her own connections to the collectivity of the group:

Just that it all fits together and that the different aspects of our characters are all there.… To be a good leader, we need to be fierce at times, and gentle (laughter). You need to be just like the jigsaw thing because things do fit together when they are done, and the cricket bat thing: I didn’t see it until you pointed it out (laughs). I saw the tree not the cricket bat; I saw the growth and the beauty. Thank you. (Tallah)

This quilt is less traditional and is not developed through symmetrical balancing or using materials which have had to follow already predetermined patterns. The colors are chosen by the women themselves and the patches are individually designed. Analysis of their quilt is taken from the analysis of the discourse shared when they discussed the completion of the quilt. The analysis provides a process of socialization in which these women were able to share their sense of self. Collins (1991) supports the theme of self-definition for black women who need to speak for themselves, to express their lived realities, which Collins feels is essential for their empowerment. Amara at this point expressed the need for flexible leadership which is eclectic in nature and does not follow Eurocentric models. Estella, similarly, shared the values of her light:

The reason I did a sun shining out is because… Well, I’ve just made a few notes on mine. Regardless of the circumstance I am in, the circle of circumstances I am standing in… I will always let my light shine. Those qualities to me would always shine regardless of the circumstances. So it’s almost a kind of act of defiance: almost “you don’t dictate to me what I do and who I am.” (Estella: 8th square)

The women are looking at their roles as leaders. Estella is clear that the illumination of her sun has to shine brightly; there are elements of hope that are shared in the collective vision of light, and the women begin to make the connections for themselves. There are pictures of suns, candles and rainbows that all illuminate their hopes for brighter futures with rewards at the end of the rainbow within the quilt. This opportunity to present themselves without barriers and to reveal genuinely who they are as leaders is seldom offered to a group of black women leaders. Esther says: ‘If barriers are presented we will go round them, under them or over them in order to achieve: we won’t stop at the barriers.’ Esther (1st square) in her quilt is using the cricket bat as a symbol of strength. She explains that the bat is able to maneuver individuals toward achievements so that they finally reach their goal. Esther’s leaves on the tree represent only half of the work that can be done. She has shared the feeling that good teamwork is gaining strength from one another. She depicts a house much smaller than the tree, in which she shares her thoughts ‘this is a home of strength: please come in.’ Her home life is important and she has recently inherited the family home where she grew up with her siblings; she feels that within her home there is a real fount of knowledge.

These women are faced with enormous responsibility. I share the sentiments of Parks (2010), who regards black women as shooting stars, fierce angels, unafraid to share their difficult moments or to articulate them, absorbed within their spiritual wisdom. Dillard (2012, p. 93) explains ‘that such spiritual wisdom and strength must be seen in our formation of community as arising from those who have experienced subordination and subjugation.’ In the midst of this is the turmoil represented by the whirlwind in my quilt, significant for me as it represents the continued struggles to rise. I acknowledge in the quilt patch black women’s history and the strength of our ancestry, enriched with the enormous energy of courageous women connected by the drive to develop new ideas and systems and creative ways of working.

Summary and Conclusion

There are key socioeconomic factors which have affected black women’s experiences of leadership (Moosa, 2009). These women’s intersectional identities are crucial in understanding the effects of these overlaps on their experiences and outcomes. Messages engraved on their psyche serve as a negative reminder of dual oppression throughout their history (Beal, 1969; King, 1988). By promoting individual and collective marginalized voices to share these stories it is possible to understand black professionals’ experiences and approaches to leadership, to improve service delivery, and to influence changes in policy direction. This different experience takes into account the women’s strong cohesive partnerships and connections to the community, as they lead by their inspiring vision and the need to influence and implement change (Kim and Kunreuther, 2009). Social justice leadership has to face the challenges presented to families, and to demand that the organizational culture and policy implementation have to be consciously challenged. The women shared their early aspirations, obtained during childhood through their traditions in their homes and close links with extended families. This article includes a descriptive analysis of the data and ways in which conclusions were reached on completion of the analysis as part of this critical qualitative study. There is a need for more research to provide reliable statistical data which outline the workforce profile, both nationally and in local education authorities (Nut-brown, 2012). The lack of such information has made it impossible to identify the number of black women who lead within the early years field nationally. There is a need to implement policies and practices that respect the need for communal support within and beyond the workplace. Challenges to dominant discourses need to include diverse voices and experiences that instill the values of a race-conscious model of leadership (Alston, 2005; Santamaria and Santamaria, 2012). Further recommendations include the use of support networks to provide early leadership coaching to help black women successfully confront challenges of inequality and negative stereotypes in their work settings (Alston, 2005; Johnson and Campbell-Stephens, 2010).

This thematic analysis has been used to identify some of the real issues faced by black women leaders in the 21st century. This article touches upon some of the important outcomes taken from the second stage of data analysis supporting their collective identity as black women leaders. It shares their spirituality, laughter and resilient selves, including their strong sense of identity demonstrated in the two focus groups. I share the view of DeVault (1996) in that the researcher should have a strong understanding of the social group and its experience of disadvantage. Mirza and Joseph (2010) strongly advocated for research and researchers that represent a multiplicity and polyvocality of black women’s lives, particularly when investigating race, class and gendered boundaries. Those who take on the role of researchers should have an informed understanding with regard to the variations that exist amongst cultural groups. An interpretive approach was chosen for this research, as it gives more insight into and promotes the value of these stories. These theories clearly acknowledge that race is central to this research. The findings and the voices expressed through the women’s stories will add to the increasing body of literature. This will transparently convey these leaders’ experiences, helping the educational field to understand key issues in the lives of black women leaders whilst dispersing traditional assumptions. For me as a black women researcher this study has been an engaging and up-lifting and during each phase of the research I have reflected on the impact on my own practice. In particularly I take with me the women’s warmth openness and care. These positive interactions as well as the women’s ability to share their own painful experiences as well as successful achievements have given value to the research. Their exchange of information and sharing their fountain of knowledge has moved the group forward as skillful educators. The researcher has shared in their sensitive, personal stories of being racialised as leaders and how they have overcome barriers to become successful in children’s and family services. In addition to these adversities, the women also shared how their laughter has helped to start a process in which they are beginning to heal from daily micro-aggressions and micro assaults.

The theme identified as the women’s silent presence, highlights leaders that are present but not seen or heard. The acceptance of remaining a silent presence begs the question as Hooks (1989) asks are we ever really alone, or are we connected through the kinship and spirituality of others, namely our foremothers. My understanding from this research is our “aloneness” is guided by the kinship, sense of self and histories of our ancestors, which add support and protection in these spaces. One in which the sharing of these collective stories and their ‘strong sense of self’ confidently connected their own threads so that they are no longer threadbare BUT bonded.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Leeds Beckett University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Adams-Wiggan, K. T. (2010). Realities, Risks And Responsibilities: A Critical Narrative Inquiry And Auto-Ethnographic Exploration Of Bi-Culturality Among Black Professional Women. Ph.D. thesis, Appalachian State University, Boone.

Alexander-Floyd, N. G. (2010). Critical race black feminism: a jurisprudence of resistance and the transformation of the academy. Signs J. Women Cult. Soc. 35, 419–426.

Allan, J., Fairlough, G., and Heinzen, B. (2002). The Power Of The Tale: Using Narratives For Organisational Success. Habokken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Alston, A. (2005). Tempered radicals and servant leaders: black females persevering. Educ. Admin. Q. 41, 675–688. doi: 10.1177/0013161x04274275

Bagilhole, B. (2006). Not a glass ceiling more a lead roof: experiences of pioneer women priests in the Church of England. Equal Opport. Intern. 25, 109–125. doi: 10.1108/02610150610679538

Barrett-Ferrier, M. (2007). Patchwork Culture: Quilt Tactics and Digi Textuality. Orlando, FL: University of Central Florida.

Bass, L. (2009). Fostering of Ethnic Care In Leadership: A Conversation With Five African American Women. London: SAGE.

Beal, F. (1969). “Double jeopardy: to be black and female,” in The Black Woman, ed. T. Bambara (New York, NY: New American Library).

Beauboeuf-Lafontant, T. (2002). A womanist experience of caring: understanding the pedagogy of exemplary black women teachers. Urban Rev. 34, 71–86.

Bell, L. (2003). Telling tales: what stories can teach us about race and racism. Race Ethnic. Educ. 6, 3–28. doi: 10.1080/1361332032000044567

Bell, L. A. (2010). Storytelling For Social Justice: Connecting Narrative and the Arts in Antiracist Teaching. New York, NY: Routledge.

Bell-Scott, P., and Johnson-Bailey, J. (1999). Flat-Footed Truths: Telling Black Women’s Lives. Australia, PA: Owl Publishing Company.

Brown, E. (2012). Negotiating the insider/outsider status: black feminist ethnography and legislative studies. St Louis Univ. J. Femin. Scholarsh. 3, 19–34.

Bush, B. (2000). Sable venus: she devil or drudge? British slavery and the fabulous fiction of black women’s identities. Women Hist. Rev. 9, 761–789. doi: 10.1080/09612020000200262

Campbell-Stephens, R. (2009). Investing in diversity: changing the face (and the heart) of educational leadership. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. Form. Sch. Organ. 29, 321–331. doi: 10.1080/13632430902793726

Collins, P. (1998). Fighting Words: Black Women And The Search For Justice. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press.

Collins, P. (2000). Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness And The Politics Of Empowerment, 2nd Edn, New York, NY: Routledge.

Collins, P. H. (1990). Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness And The Politics Of Empowerment. New York, NY: Routledge.

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins of intersectionality: identity politics and violence against women of colour. Stanford Law Rev. 43, 1241–1299.

Curtis, S. E. (2014). Black Women Leaders in Early Years Education. Ph.D. thesis, Beckett University, Leeds.

Curtis, S. E. (2017). Black women’s intersectional complexities: the impact on leadership. Manag. Educ. BELMAS 31, 94–102. doi: 10.1177/0892020617696635

Delgado, R. (1989). Storytelling for oppositionists: a plea for narratives. Michig. Law Rev. 87, 2411–2441.

Delgado, R., and Stefancic, J. (1995). Critical Race Theory: The Cutting Edge, Vol. 79, (Philadelphia: Temple university press), 461–516.

Delgado, R., and Stefancic, J. (2001). Critical Race Theory: An Introduction, 1st Edn, New York, NY: New York University Press.

DeVault, M. L. (1996). Talking back to sociology: distinctive contributions of feminist methodology. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 22, 29–50. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.22.1.29

Dillard, C. B. (2012). Learning to Remember The Things We’ve Learnt to Forget: Endarkened Feminisms, Nature of Research and Teaching, Black Studies and Critical Thinking. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Few, A., Stephens, D., and Rouse-Arnett, M. (2004). Sister to sister talk: transcending boundaries and challenges in qualitative research with black women. Fam. Relat. 52, 205–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2003.00205.x

Gabriel, Y. (2000). Storytelling In Organizations: Facts, Fictions, and Fantasies. Oxford: Oxford University.

Gibson, P., and Abrams, L. (2003). Racial difference in engaging, recruiting and interviewing African American women in qualitative research. Qual. Soc. Work 2, 457–476. doi: 10.1177/1473325003024005

Gillborn, D. (2008). Racism and Education: Coincidence or Conspiracy? Whiteness, policy and the persistence of the black/white achievement gap. J. Educ. Rev. 60, 229–248.

Gillborn, D., and Mirza, S. (2000). Mapping Races, Class And Gender: A Synthesis Of Research Evidence. London: Institute of Education.

Gilligan, C. (1993). In A Different Voice: Psychological Theory And Women’s Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hammersley, M. (1992). What’s Wrong With Ethnography? Methodological Explorations. Abingdon: Psychology press.

Hayman, B., Wilkes, L., Jackson, D., and Halcomb, E. (2012). Story-sharing as a method of data collection in qualitative research. J. Clin. Nurs. 21, 285–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.04002.x

Johns, M. (2011). Tenacious Threads: Crazy Quilts As An Expressive Medium For Making Art. Ph.D. thesis, Georgia State University, Atlanta.

Johnson, B. (2012). African American Female Superintendents: Resilient School Leaders. Ph.D. thesis, University of Minnesota: Minneapolis, MI.

Johnson, L., and Campbell-Stephens, R. (2010) Investing in Diversity in London Schools: Leadership preparation for black and global majority educators. Urban Educ. 45, 840–870. doi: 10.1177/0042085910384353

Johnson-Bailey, J. (1991). The ties that bind and the shackles that separate race, gender, class and colour in a research process. Qual. Stud. Educ. 12, 659–670. doi: 10.1080/095183999235818

Kahn, D., and Eide, P. (2008). Ethical issues in the qualitative researcher–participant relationship. Nurs. Ethics 15, 2199–2207.

Kim, H., and Kunreuther, J. (2009). Vision for Change: A New Wave Of Social Justice. New York, NY: Leadership Building Movement Project.

King, D. K. (1988). Multiple jeopardy, multiple consciousnesses: the context of a black feminist ideology. J. Women Cult. Soc. 14, 42–72. doi: 10.1086/494491

Koelsch, E. (2012). The Virtual Patchwork Quilt: A Qualitative Feminist Research Method. London: Sage.

Kvasny, L., Greenhill, A., and Trouth, E. (2005). Giving voice to feminist projects in management information systems research. Intern. J. Technol. Hum. Interact. 1, 1–18. doi: 10.4018/jthi.2005010101

Maddox, T. (2013). Professional women’s well being: the role of discrimination and occupational characteristics. Women Health 53, 706–729. doi: 10.1080/03630242.2013.822455

Madriz, E. (2003). “Focus group on feminist research,” in Qualitative Methods, eds N. Denzin and Y. Lincoln (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage).

Matsuda, M. (1989). When the first quail calls: multiple consciousness as jurisprudential method. Women’s RTS. L. Rep. 11:7.

Meyerson, E. (2003). Tempered Radicals: How People Use Difference To Inspire Change At Work. Waterown, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Mirza, H., and Joseph, C. (eds) (2010). Black and Postcolonial Feminisms In New Times: Researching Educational Inequalities. New York, NY: Routledge.

Moosa, Z. (2009). Lifts And Ladders: Resolving Ethnic Minority Women’s Exclusion From Power. London: Fawcett Society.

Nut-brown, C. (2012). Foundations for Quality: The Independent Review Of Early Education And Childcare Qualifications. London: Government of the United Kingdom.

Parks, S. (2010). Fierce Angels: The Strong Black Women in American Life and Culture. New York, NY: One World.

Patterson, J., and Kelleher, P. (2005). Resilient School Leaders: Strategies For Turning Adversity Into Achievement. Alexandria, VA: Association for supervision and curriculum development.

Roberts, L. (2013). Critical Race Theory as a Space of Interdisciplinary. Manchester: >ESRI Manchester metropolitan University.

Rodriguez, D. (2006). Un/Masking identity: healing our wounded souls. Q. Inq. 6, 1067–1090. doi: 10.1177/1077800406293238

Rogers, C. R. (1986). Carl rogers on the development of the person-centered approach. Person Cent. Rev. 1, 257–259.

Santamaria, J., and Santamaria, A. (2012). Applied Critical Leadership in Education: Choosing Change. New York, NY: Routledge.

Santamaria, L. J. (2013). Critical change for the greater good: multicultural dimensions of educational leadership toward social justice and educational equity. Educ. Admin. Q. 50, 347–391. doi: 10.1177/0013161x13505287

Shelby, T. (2002). Foundation of Black Solidarity: Collective Identity Or Common Oppression. Ph.D. thesis, University of Chicago, Chicago.

Smith, D. (1997). Identity, Self and Other in the Conduct of Pedagogical Action: Action research and Living Practice. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Solórzano, G. D., and Delgado, D. (2001) Examining Transformational Resistance Through a Critical Race and Latcrit Theory Framework: Chicana and Chicano Students in an Urban Context, Vol. 36. Thousand Oaks, CA: >Sage publishing.

Solórzano, G. D., and Yosso, J. T. (2001). Critical race methodology: counter-storytelling as an analytical framework for education research. Q. Inq. 8, 23–44. doi: 10.1177/107780040200800103

Stalp, B. M. (2001). Women Quilting, and Cultural Production: The Preservation of Self in Everyday Life. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University.

Strauss, A., and Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of Qualitative Research Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Villapando, O. (2003). Self- segregation or self preservation? critical race theory analysis of findings: a longitudinal study of Latino Students. Intern. J. Q. Stud. Educ. 16, 619–649.

Wilson, S. (1999). Fragments On Art-Based Narrative Inquiry. Ph.D. thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver.

Witherspoon, N., and Mitchell, W. R. (2009). Critical race theory as ordinary theology of African American principals. Intern. J. Q. Stud. Educ. 22, 655–670. doi: 10.1080/09518390903333871

Keywords: social justice leadership, Critical Race Theory, black feminism, collective identity, sense of self, black feminism, intersectionality

Citation: Curtis S (2020) Threadbare BUT Bonded—Weaving Stories and Experiences Into a Collective Quilt of Black Women’s Leadership. Front. Educ. 5:117. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00117

Received: 04 February 2020; Accepted: 15 June 2020;

Published: 26 October 2020.

Edited by:

Victoria Showunmi, University College London, United KingdomReviewed by:

Judy Alston, Ashland University, United StatesDaniel D. Liou, Arizona State University, United States

Copyright © 2020 Curtis. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sharon Curtis, U2hhcm9uQGVsbGVzbWVyZWNjLm9yZy51aw==

†Present address: Sharon Curtis, Educational Consultant, Leeds, United Kingdom

Sharon Curtis

Sharon Curtis