- 1Department of Educational Leadership & Sport Management, Washington State University Tri-Cities, Richland, WA, United States

- 2Department of Educational Leadership & Sport Management, Washington State University, Spokane, WA, United States

- 3Department of Educational Leadership & Sport Management, Spokane, WA, United States

- 4Department of Educational Leadership & Policy Studies, The University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN, United States

The current study utilizes feminist life course theory to examine the perspectives of women who have aspired or have entered into the superintendency in the United States. Life course theory suggests that our “role histories” often inform our choices about careers. The role histories reflect instantaneous responses to the social cues of our external world. Consequently, it offers opportunity to understand how patterns of socialization may impact real-life decisions over career possibilities (and impossibilities) and the historical conditions in which career decisions are made. Using survey responses from current and aspiring female superintendents (n = 133), we engaged in descriptive and inferential statistical analyses. We contextualized these findings further through the four principles of life course theory, historical time and place, timing in lives, linked lives, and human agency. Our findings indicate women’s perspectives on the accessibility of the superintendency have shifted as narratives around women’s executive leadership roles have also changed. Importantly, the women in this study view accessibility to the superintendency as a largely contingent decision – a strategic, individual-level assessment focusing on the favorability of district work conditions to their success as leaders. Simultaneously, we see where issues of social networking, leadership “tapping,” and district “fit” emerge as normative expectations for accessing leadership roles as well as the preferred conditions upon which such choices are made. This reflects an encouraging perspective shift in which women are focusing less on “feasibility” than on “fit.” We conclude by offering recommendations for practice.

Introduction

Over the last half century, women have surpassed men in educational achievement and postsecondary degree completion (National Center for Education Statistics [NCES], 2016). Women now earn 60% of all undergraduate degrees along with 60% of all master’s degrees and represent 49% of the college-educated workforce nationwide, including 52% of all professional-level jobs (Warner et al., 2018). These advancements in women’s educational achievement should signify new opportunities and new potential entry points into more elite leadership roles. Yet, the reality is a far different one with aggregated gains in educational achievement failing to translate into professional advantages for women – and particularly for those aspiring to positions of leadership. To this point, the Warner and Corley (2017) recently reported that among those currently employed at S&P 500, 44% are women, yet they make up only 35% of all mid-level managers, 25% of senior or executive-level leadership, and 6% of all CEO’s. How and why these disparities exist is certainly up for debate. The “glass ceiling” (Loden and Rosener, 1991) of gender-based leadership disparities, particularly in high profile S&P 500 positions has been well documented (Warner et al., 2018). Yet, we see these same patterns hold remarkably true for other similar high prestige leadership positions in fields like medicine, law, and importantly education (Warner et al., 2018).

Within United States’ K-12 educational system, the school superintendent represents the preeminent leadership position within a regional school district. As chief visionary, advocate, communicator, and negotiator, the school superintendent wields tremendous influence over the quality of teaching and learning that occurs under his/her stewardship (DuFour and Marzano, 2011). This alone justifies the need for greater gender diversity within these senior leadership positions. Yet, it remains the case that, the school superintendency represents one of the most male dominated executive positions among all the professions (Glass et al., 2000; Dowell and Larwin, 2013; Searby et al., 2015; Burton and Weiner, 2016; American Association of School Administrators [AASA], 2016) – and indeed the numbers appear to back this up. As of 2015, for example, 73% of all district superintendents were male (Robinson, 2015), yet 77% of all teachers identified as women (Taie and Goldring, 2017). While women have made impressive gains at all levels of school leadership within the US, representing 52% of all principals and 78% of all central office administrative positions, they still make up less than 25% of district superintendents nationwide (Glass and Franceschini, 2007). Prior research offers any number of differing rationales for why these barriers continue to exist, suggesting that they are: (1) a reflection of the structural inequalities that serve as intentional and unintentional gatekeeping within the superintendent pipeline (Grogan, 2000; Tallerico and Blount, 2004; Ward et al., 2015), (2) unofficially sanctioned gender discrimination intended to stave off women’s encroachment in what has been a historically male-only senior leadership role (Brunner, 2000; Skrla et al., 2000; Garn and Brown, 2008), (3) a perceived incompatibility between the work expectations of the superintendency and women’s dual commitments to career and family (Hill et al., 2017); and (4) the mismatching of women’s managerial and leadership styles with the demands of a district’s chief executive position (Grogan and Shakeshaft, 2011).

Whether it is the strain of family commitments, a predilection to certain leadership styles and dispositions, or the multiple derailments that characterize the leadership “labyrinth” (Eagly and Carli, 2007), there is a tendency to frame women’s career trajectories, including that of the superintendency, as a juxtaposition and/or tension between women’s private and professional worlds. Feminist scholars, however, have also pushed back on this overly reductionist characterization of women’s lives (Kanter, 1977; Lopata, 1993; Hoyt, 2010; Schultheiss, 2013), suggesting that it diminishes the range of work women engage in, fails to account for the various influences that inform women’s career choices, and important to this study, fails to account for the historical shifts in social sentiment about a women’s place in the world. Rather than point to a supposed contentiousness between women’s public and private lives, feminist voices instead suggest that women’s professional choices are in many ways deliberated, negotiated, and ultimately constructed in accordance with the prevailing gender norms around women’s paid work over time (Strober and Tyack, 1980).

Along these very same lines, the current study seeks to further engage with this last point by exploring the relationship between historical sentiment on women’s professional leadership and how those sentiments inform women’s perspectives on the superintendency. We analyzed data collected from 133 established and aspiring superintendents affiliated with one statewide professional superintendent association in the state of Washington located in the northwest region of the United States. Survey questions asked women to reflect on perceived challenges they have faced in navigating the pathway to the superintendency. Consistent with our study aims, we analyzed data collected through life course theory (Elder, 1998). Life course theory suggests life pathways are historically, socially, and culturally situated. As such, decisions, choices, aspirations, and failures are a product of more than individual circumstance, disposition, or personal preference. Rather, these pivotal life moments are responses to external cues reflecting the social patterns, values, and norms of a particular historic moment. Our use of life course theory in the context of this specific study places gender at the center of these analyses, suggesting that women’s decisions are aligned with gendered social patterns, values, and norms. By extension, it suggests that, in the context of life course theory, career choice is less a balance between private and professional spheres and more a negotiation of the social and cultural factors that inform women’s decision-making.

In keeping with these ideas, we also sought to understand how a cross-section of aspiring and currently seated superintendents felt about barriers to entering this most senior leadership role. However, we did so by relying upon the explanatory power of life course theory to make sense of these barriers. As is customary, the remainder of this paper proceeds in five sections. The subsequent section offers an overview of existing research that has examined the macro-historical shifts in perspective on women and work as well as women in the superintendency and the identified barriers to such access. We then transition to a more in-depth discussion on life course theory, its origins and relevance to the present study. The fourth section describes the data and methodological approach utilized in analyzing the cohort data. The fifth and final section will reconsider women’s perceptions in light of life course theory and the implications for leadership educators who seek to encourage more women to the superintendency.

The present study serves in many respects as a continuation of the original longitudinal work by Sharratt and Derrington (1993) and Derrington and Sharratt (2009a, b). Their groundbreaking efforts to document how cohorts of aspiring and seated women superintendents within the state of Washington have perceived the barriers to their profession over time, sets the stage for our current work. In using a subsequent wave of 2016 cohort data via a slightly modified version of their original survey questionnaire, we take advantage of this prior work to further situate our understanding of the normative shifts that have taken place in how women come to view the superintendency. We will, of course, return to this point in the next section.

Literature Review

An important goal of this study is to understand how sociohistorical forces may shape women’s professional decision-making. The history of the superintendency is, in many ways, a reflection of these tensions. Indeed, the percentage of women in the superintendency has risen and fallen in surprising fashion over the course of history in the United States. Tallerico and Blount (2004) suggested that the evolution of women’s entry into district-level leadership followed three distinct integration patterns. In the 20th century, the superintendency was a nearly exclusive male occupation. During this period, men occupied from 85–96% of all executive leadership positions in the nation. Starting, in 1910 through 1930, however, districts experienced a surprising uptick in women leadership within the ranks of the superintendency, jumping from the 9% of all superintendents in 1910 to 11% in 1930. Shakeshaft (1989) and Blount (1998), Shakeshaft (1999) reason that this surge was, in fact, a byproduct of the women’s suffrage movement and the fact that some county and state superintendents were elected to posts as opposed to being appointed (Tallerico and Blount, 2004).

This period of growth was short lasting, however, as state legislative changes eliminated these elected superintendent positions and suffragists moved on to more pressing issues. A number of other factors contributed to overall decreases in women leadership from 1930 to 1970. After 1930, shifting expectations for the position required candidates to have specific training and certifications. This “credentialing” of the profession also coincided with a national push to educate a largely male population of veterans returning from World War II (Tallerico and Blount, 2004, p. 643). Lastly, school districts across the country went through a period of consolidation leading to a net loss in the total number of superintendent positions. Given that women represented only 3% of the nation’s superintendents in 1970, this consolidation clearly benefited men (Tallerico and Blount, 2004, p. 644).

The third and final shift in the make-up of the superintendency began following the low of 1970 through to the current day. Racial integration followed the 1970 low, resulting in a second uptick in the total number of superintendents. This period marked only the second time in the 20th century where we begin to see increasing numbers of women entering the superintendency. Despite the surge in the gross number of district superintendencies, women remained largely under-represented in these leadership roles. This, of course, continues to the present day.

Shifting Perceptions Over Barriers to Entry

While the post-1970 expansion in the superintendency created more opportunities for women to take on these leadership roles, there remained substantive barriers to entry that have continued to constrain women’s aspirations. Research focusing on women’s ascendency (and lack thereof) to senior district roles have pointed to such things as gender bias, the relative absence of role models and mentoring/support networks for women, familial obligations, and professional gatekeeping as key barriers to entry for aspiring women leaders. We summarize some of the key research that focuses on these barriers in the discussion that follows.

Gender Bias Against Women

Numerous studies have pointed to the inherent gender bias that aspiring women face along the path toward the superintendency (Kowalski and Stouder, 1999; Glass, 2000; Skrla, 2000; Banuelos, 2008; Hoff and Mitchell, 2008; Goffney and Edmonson, 2012). As is the case in other fields and other elite positions, gender bias has moved from explicit and rampant to nuanced and subtle (Brunner, 2000; Polnick et al., 2007; Banuelos, 2008). Banuelos (2008) and Goffney and Edmonson (2012) both reported on the impact that gender bias played in the professional pathways of aspiring women superintendents. In addition to experiencing emotional distress because of these perceived slights, gender bias tended to be more impactful than race or ethnic bias for women en route to the superintendency (Tallerico, 1999a,b). Recognition as to the presence of gender bias in such things as recruitment and hiring is not limited to women alone, of course, as men are also keenly aware of the challenges women routinely face (Tallerico, 1999a,b; Garn and Brown, 2008). “Old boys” networks, reward structures, and highly gendered notions of the “ideal” worker1 are widely recognized by men and women alike as having an indelible effect on women’s professional lives.

Mentors and Networks

Research has also pointed to the ways in which women’s pathways are also constrained by the relative absence of strong mentoring and extensive network support (Campbell-Jones and Avelar-Lasalle, 2000; McNulty, 2002; Katz, 2006; Garn and Brown, 2008; Lane-Washington and Wilson-Jones, 2010; McGee, 2010; Goffney and Edmonson, 2012). The reasons for why this may occur are simple: Effective mentorship includes the capacity by mentors to call upon their professional experiences, professional networks, and depth of understanding for the field in support of their mentee’s growth and development (Alsbury and Hackmann, 2006; Copeland and Calhoun, 2014). If women are under-represented within the superintendency, the number of women mentors will be similarly under-represented. Similarly, networks of available support may also be constrained by the lack of available female resources (McNulty, 2002; Katz, 2006; Goffney and Edmonson, 2012). While networks are rarely gender exclusive, the lack of female role models within the field has an inevitable cooling effect – particularly for those women who find themselves aspiring to move into a district leadership role.

Women’s Outsized Familial Obligations

Family obligations are yet another identified complication for women seeking the superintendency (Barrios, 2004; Sharpe et al., 2004; Dana and Bourisaw, 2006; Goffney and Edmonson, 2012). This can take form in any number of ways: tempering of career aspirations and potential advancement for the sake of the family, concerns over the impact of demanding professional obligations on quality time spent with family, and placing undue pressure on a spouse or partner in order for women to pursue career advancement (Sharpe et al., 2004; Goffney and Edmonson, 2012). The obligation to relocate for the sake of career advancement is yet another identified barrier for women aspiring to the superintendency. Sharpe et al. (2004) as well as Dana and Bourisaw (2006), Hoff and Mitchell (2008), and most recently Sperandio and Devdas (2015) point to mobility (or the lack thereof) as a factor in whether a woman pursued and/or accepted a superintendency position. McGee (2010) also found that women’s perceived “boundedness” constrained the available sets of options available to a women aspiring to become a superintendent. Concerns over family wellbeing may therefore complicate women’s aspirations and/or temper them as a result.

Professional Gatekeeping

Another frequently identified barrier for women seeking the superintendency comes in the form of professional gatekeeping (Shakeshaft, 1989; Shoemaker, 1991; Skrla, 1999; Tallerico, 1999a; Glass et al., 2001; Tallerico and Blount, 2004; Newton, 2006). The history of the superintendency is in many ways a history of legislative steps, board maneuverings, and credentialing challenges that all serve to undermine access and entry for women and people of color (Tallerico, 1999a; Young and McLeod, 2001; Dana and Bourisaw, 2006). Dana and Bourisaw (2006) speak to the role that school boards and male-dominated selection committees have played in recruitment/hiring process. They suggest that the impact of largely white male dominated selection processes have led to the perpetuation of white male leadership within school districts. Bernal (2019) in her small-scale study of search firms found that while consultants believed that they conducted searches in an unbiased fashion, there were indications that unconscious biases were often at play in how they went about the search process. Gender stereotypes, beliefs surrounding gendered leadership styles and other biases were often viewed as detrimental to the hiring chances of women.

As part of a sweeping study of superintendent pathways within the state of Texas over a 15-year period, Davis and Bowers (2019) found that women and educators of color were often required to prove themselves as compared to their white male counterparts in pursuit of the superintendent role. For example, white men were more likely to make the dramatic professional leap from the principalship into the superintendency, whereas women and people of color tended to transition from higher ranked assistant superintendent positions. Consequently, the pathways for women and people of color were more extensive and required higher level experience prior to transition. Interestingly, when looking at the intersections between race, ethnicity, and gender, Bradley and Bowers determined that, controlling for all other variables, gender had the greatest impact upon whether or not someone went on to become a superintendent, suggesting once again that structural factors play a significant role in women’s professional pathways.

A substantial body of literature has not only looked at composite trends and patterns that make up a successful pathway to the superintendency but also at the structural barriers that inhibit women’s progress (Glass, 2000; Sharpe et al., 2004; Hoff and Mitchell, 2008). Research evidence, for example, appears to suggest differences as to when men and women decide to pursue administrative careers (Sharpe et al., 2004). Studies by Young and McLeod (2001), Hoff and Mitchell (2008), and Sampson et al. (2015) present evidence to suggest that men are much more apt to view themselves as leadership material much earlier in their careers than women. Shakeshaft’s well cited 1989 study suggests that men, on average, decide on an administrative path nearly 10 years before women. These decisions have severe consequences, as early career decision-making leads to more intentional career choices for men that may result in substantially different, more strategic pathways to leadership roles. Unequal career qualifications/experiences inevitably place late-emerging women at a substantial disadvantage on the job market (Shakeshaft, 1989).

Sharpe et al. (2004) point to the type of administrative experience as also salient to successful advancement to the superintendency, with the principalship and district office positions being the most important steppingstones of all. Interestingly, not all leadership roles, particularly within the principalship, are equally valued despite representing a critical stop en route to the superintendency (Ellerson, 2015; Maranto et al., 2018; Davis and Bowers, 2019). We know, for instance, that the role of high school principal and central office roles represent particularly important proving grounds for future district leaders given the range of student, fiscal, personnel, and regulatory responsibilities that uniquely fall within these positional domains. And while women are increasingly finding themselves in district level positions, they are often cloistered in areas related to curriculum, while men are focused on human resources and fiscal responsibilities (Sharpe et al., 2004). Likewise, women are more apt to serve as principals in elementary and middle school settings as opposed to high school (Sharpe et al., 2004). Such experiential differences, while still valuable, place women at a distinct disadvantage when they wish to make the more difficult transition into district leadership.

Summary

In sum, the history of women’s entry into the superintendency is a relatively long and complicated one. While women have certainly made significant advances in professionalization resulting in greater leadership opportunities, they still remain under-represented at the highest levels of district leadership. Answering the question as to why these intractable patterns exist has been the focus of a vast body of research. From this body of work, we know that there are a wide and varied number of factors that contribute to women’s under-representation. These include cultural factors (gender biases), social norms (women’s role as family caretaker), and structural constraints (gatekeeping at all phases of the recruitment and selection process). The current study reconsiders these barriers within the context of the current sociohistorical context via the use of life course theory.

Theoretical Framework

For this study, we used life course theory as presented by Loder (2005) and originated by Elder (1992, 1998) to help frame our findings. Life course theory allows us, as feminist researchers to situate our participants’ perspectives on their career pathways within the larger social world in which those choices are made. It does so by connecting macro level social-historical dynamics to the micro-level perspectives of our study participants.

Life course theory by name alone suggests an emphasis on temporality. Time is certainly a feature of life course, and in fact, it bears noting that Elder himself spoke to the emergence of life course research as product of important advances in longitudinal design (Elder et al., 2003). That said, life course does not operate exclusively within the longitudinal realm. Rather, it serves as a rejection of the “timeless realm of the abstract” (Nisbet quoted in Elder et al., 2003). In other words, it suggests that life trajectories are perpetually developmental in nature and that our social pathways, nay our life pathways, are persistently shaped by the “socio-historical conditions” of the external worlds in which we are embedded (Elder, 1998; Elder et al., 2003).

Elder et al. (2003) argue that the study of careers, and career choice, may be particularly well served by life course theory. Our choices about careers are often founded upon what may be best characterized as “role histories” made up of near instantaneous responses to the multiple roles and social cues of our externalworld. In other words, career research, as framed through life course, offers the opportunity to understand how espoused norms, values, and patterns of socialization may impact real life decisions and perceptions related to career possibilities and impossibilities.

In keeping with this idea of life course as a theoretical lens for examining human behavior in context, Elder (1998) offers a set of four empirical reference points or principles for operationalizing the theory into practice. These principles serve as guides for how we might better understand the interplay between the career perspectives of our study population and realities they face (or have faced) in navigating the superintendency pathway. These four principles are: (1) Historical Time and Place; (2) Timing in Lives; (3) Linked Lives; and (4) Human Agency. We will address each in turn.

Historical Time and Place

Stephen Covey once famously stated that (Covey et al., 1995), “priority is a function of context (pg. 154)” What he meant by that was that our behaviors, and ultimately our choices, are a product of the moment in which they are formed. This also extends to historical context. Life course theory suggests that our decisions are shaped and informed by history as history, at its essence, is the study of context (Elder et al., 2003). Generational research serves as a perfect example of this intersection between choice and context. Countless studies have tried to bring meaning to the responses that different generations make in response to time honored life decisions. A recent example of this type of research is the ongoing debate around so-called “millennials” willingness to purchase cars2. In effect, “historical time and place” acknowledges the value of time-stamping as a means for understanding collective sense-making, particularly when examining a population cohort’s life experiences and choice inclinations. Similarly, insights can be drawn to the role of historical context in the framing of our study sample’s perspectives on the superintendency – and how that might differ substantially depending upon their place along their career pathway.

Timing in Lives

Life transitions reflect pivotal moments in the life course when choices are made and ultimately acted upon. By consequence, they are rich in significance and imbued with meaning reflective of both the social and cultural freedoms as well as perceived constraints reflective of the moment. Life course theory suggests that in naming these moments of constraint or freedom, we bring insight to micro and macro-level decision-making as well as the choice sets upon which those decisions are made. For example, the ways in which we might interpret perceived barriers by aspiring and established superintendent within this existing cohort of respondents would, according to life course theory, need to be considered in relation to where they were located along the pathway to the superintendency.

Linked Lives

Relational interconnectedness serves as yet another central feature of life course theory. Elder et al. (2003) suggest that social context has particular bearing upon interpersonal relationships and that the quality and quantity of those relationships can often be influenced by larger social changes. Likewise, social change can have a rippling effect on each individual within a given network of people, moving and recalibrating the nature and terms of those relationships. Consequently, advantages or disadvantages rendered through those networks are inevitably mediated by larger social forces and therefore must be accounted for when examining and rationalizing social phenomena in empirical settings. If we consider, for instance, the role that relationships play in the formation of career aspirations or the reliance many men and women place on networks to navigate complicated career pathways, it follows that such relationships are critical feature of career progress. It also follows that these relationships may be, in part, conditioned by the realities and expectations of the historical moment.

Human Agency

While the social context cues, values, and norms have a conscious or unconscious effect over our potential choice-sets and ultimately our life paths, we are not passive actors in those pivotal moments. Human agency plays are particularly powerful role in the course we set for ourselves. Most anyone has engaged in some form of life planning, whether it be our educational pathways, parenthood, where to live, and so on. Life course theory doesn’t discount the importance of agency in the life course process. However, it does suggest that planning can be shaped in accordance with expectations of that particular historical moment. A half century ago, it was unlikely that a woman might even aspire to becoming a superintendent, much less expect to serve in that capacity. Time, circumstances, shifting norms around women’s role in the home and in the larger economy have changed the ways in which women (and men) view themselves and their career possibilities. Consequently, human agency and the historical moment are inextricably connected – particularly in the context of career-related perspectives.

The four principles of life course theory provide us with points of reference as we consider the perspectives of women, both established superintendents as well as those still seeking the superintendency. What they believe are the key drivers to success for women? How do they come to understand the roadblocks? And in what ways might these perspectives reflect on the social contexts, norms, values of the historical moment in which they are embedded? These serve as the basis for our discussion to follow.

Data and Methods

This study focuses on women’s viewpoints on the superintendency. Given our interest in understanding the navigational barriers women face as they ascend to executive level positions, we relied upon survey responses as a primary source of insight into their thinking about women’s leadership pathways. Our intention in collecting this data emerged from an interest in assessing current and aspiring women superintendents’ beliefs about the relative accessibility of this most senior leadership role for women.

All findings represented in this study came from survey responses provided by women-identified members of the Washington Association of School Administrators (WASA) located in the state of Washington. Some members of our research team have been members in and/or have maintained a long-standing relationship with WASA in their roles as district leaders and later as researchers and leaders of superintendent preparation programs. WASA has served the state as the premier advocate and professional resource for superintendents over the last sixty years.

Study Population

Our population of interest for the current study were women in the State of Washington who were either aspiring or seated school superintendents. In each case, we used purposeful sampling. With the support of association leadership, we were able to administer an online Qualtric survey to WASA members in fall 2016. Respondents were subscribers to the professional job listing service offered to members through the association. A total of 540 women subscribers received the solicitation with 133 subscribers completing the survey, resulting in a 25% response rate. Of the 133 women who responded to our survey solicitation, 42 (31.5%) were current superintendents and 91 (68.5%) were in administrative positions in a district (to include assistant superintendents, directors, coordinators, principals and others within the administrative structure).

Background on the WASA Superintendent Survey

As stated earlier, the data collected for the current study represents the latest administration of a survey originally developed by Sharratt and Derrington (1993) and Derrington and Sharratt (2009a, b). The intent of the original survey, first administered in spring of 1993, was to learn more about how women educators within the state of Washington understood the barriers before them, particularly as they attempted to advance their careers as educational leaders within the state.3 In February of 2007, the same researchers sent the questionnaire to approximately 140 WASA women subscribers.4 The survey questions were identical to the 1993 version as it continued to have participants rate the extent to which barriers negatively influenced their desire or ability to reach the superintendency. A third administration of this survey was administered to WASA membership in the Fall of 2016. We once again used Derrington and Sharratt’s survey items with one additional question focusing on family and pipeline barriers. Analyses for the current study focus exclusively on responses collected as part of the 2016 administration of the survey.

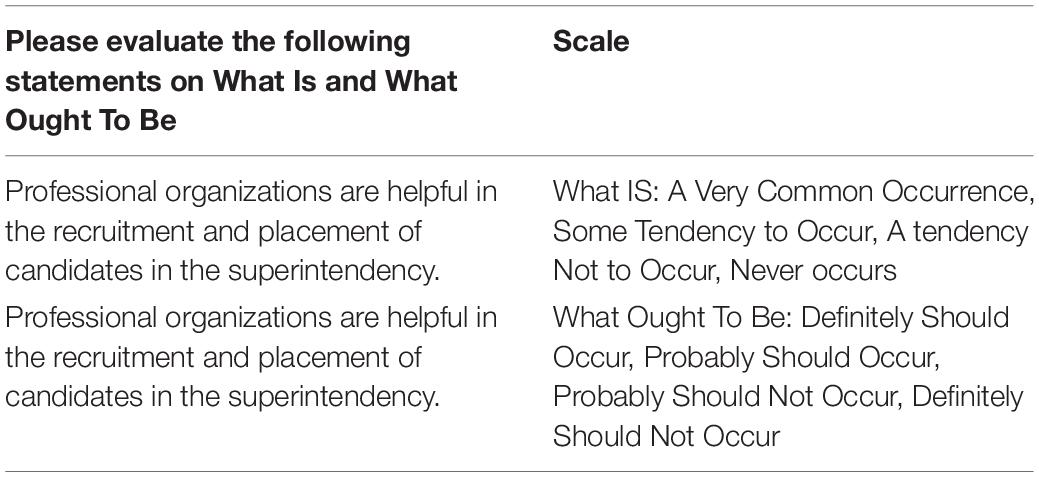

The questionnaire reflects a combination of likert, rating, and ranking scale items in combination with basic demographic information such as their total years of experience in the field of education, educational attainment, current position, and career goals. The original construction of the survey instrument was designed to follow a discrepancy model format whereby respondents would be required to draw normative conclusions regarding the current state of “accessibility” for women seeking advancement into district leadership positions. Accordingly, respondents were asked to compare current conditions for women’s advancement (“what is”) compared to the most optimal conditions (“what ought to be”) when reflecting upon self-reported barriers that they felt limited their advancement. This questionnaire was based upon the “actual-ideal discrepancy model” (AID) originated by James back in 1980 (James, 2007). This assessment approach was designed to illuminate differences between a respondent’s self-perception of a given subject domain as compared to idealized standards for that domain. Table 1 offers an illustration of a typical discrepant item in which we asked respondents to evaluate specified field conditions of the superintendency as follows:

In this instance, respondents could discern current supports offered by professional organizations against what they would ideally wish to see. This afforded the research team opportunities to then determine how perceptions over the conditions for access to the field may have shifted with time. Likewise, we are able to assess differences in understanding between seated versus aspiring superintendents within a given cohort. Face validity and pilot testing of survey items occurred prior to the 1993 administration of the survey.

Survey items reflected previous research on the superintendency (Shakeshaft, 1985, 1987). In keeping with the discrepant model format, survey items captured four areas of specific inquiry: individual factors that led respondents to pursue the superintendency, factors that would determine whether a respondent would apply to a particular district, internalized barriers that they felt served as substantive roadblocks to them and/or other women accessing the superintendency, and conditions that would (or wouldn’t) optimally serve women in their current or past pursuit of the superintendency. Importantly, we had respondents offer not only insights into the internal conditions that served to undermine their aspirations (or those of other women), but also the external, structural conditions that they represented formidable roadblocks en route to the superintendency.

Data Analysis

The research team conducted descriptive and inferential analyses on the 2016 survey data collected in order to identify trends and patterns in response within the more current cohort of WASA respondents. In order to compare meaningfully across the two within-cohort comparison groups, seated and aspiring superintendents, we completed two-tailed t-tests so that we might calculate a more robust comparison of group means. This also permitted us to determine patterns of difference between the two groups as well as to determine statistical significance among those differences. In doing so, the research team was able to draw general conclusions regarding points of agreement and disagreement within the 2016 cohort on a host of different topics related to conditions for access to the superintendency.

The research team was responsible for all data analysis work, the outcomes of which support the findings for this paper. Team members looked for relevant patterns within the collected data. Likewise, our team analyzed data results independently and collectively. We drew upon the life course theory framework in the formulation of our study conclusions.

History as a Secondary Data Source

While the data collected and presented in this study certainly offers a compelling story as to how women have perceived and negotiated the pathway to the superintendency, our use of life course theory demanded that we also contextualize those analyses within the historical moment in which women are responding to the survey instrument. Consequently, we utilize social, cultural, and political history to bring further meaning to the findings generated from the participants’ survey responses. Consequently, history serves as an inflection in each of the four life course domains: (1) Historical Time and Place; (2) Timing In Lives; (3) Linked Lives; and (4) Human Agency.

Study Limitations

Certainly, we must place the analytical reach of this study in context. First, respondents to our survey belonged to one professional association located in one region within the United States. It is, however, noteworthy that the percentage of women superintendents found in Washington state is very consistent with national AASA data. Women make up 26.7% of superintendents nationally (AASA, 2020), while women make up 26% of all superintendents in the state of Washington (H. Paroff, personal communication, February 10, 2020). We also acknowledge that the decisions and sense-making around professional choice is often an intersectional one informed by multiple and overlapping identities (i.e., race, social class, sexual identity, age, among others) (Crenshaw et al., 1994; Özbilgin et al., 2011). While our intention through this study was to look at the impact of socio-historical context on the gendering of life choices, we do not suggest that these choices occur outside of other salient identities (Crenshaw, 1990). Our point is instead to consider the potential contributions that an examination of this interplay between social history, gender, and professional choices offers, particularly in so intractable a career entry point as the superintendency is for women across dimensions of race, ethnicity, age, social class, and sexuality. As stated previously, generalizability was not a primary goal of this study – the major purpose was to offer insight into the perceived barriers to entry among both seated and aspiring women superintendents.

Study Findings

The women who responded to the 2016 administration of the WASA survey had much to say about the challenges they believe stood as barriers for women entering the superintendency. In this section, we offer an overview of these findings as framed through the four principles of life course theory: (1) Historical Time and Place; (2) Timing in Lives; (3) Linked Lives; and (4) Human Agency.

Historical Time and Place

Elder (1998, 2005), Elder et al. (2003) principle of historical time and place focuses on the cognitive imprint of a historical moment on the normative decision-making of a cohort of individuals. How do events of the present-day shape and inform collective sense-making? And how does that then impact our sample population’s assessments over what is possible for women as it relates to the superintendency? Before we answer these questions, it’s important to take stock of the normative conditions for such an assessment as depicted in the political and cultural events of 2016.

2016: A Year of Promise and Disappointment for Women

In their December 2016 retrospective entitled, “The 15 Best Moments for Women in 2016,” Harper’s Bazaar5 highlighted the momentous year that 2016 was for women. The most significant development for women that year was, of course, Hilary Clinton’s nomination as the Democratic candidate for the US presidency on July 26, 2016. Clinton, a collector of many firsts in American politics, represented what many had hoped would be a final break in the omnipresent glass ceiling for American women. Even she acknowledged the historical moment as such by famously stating in her nomination speech that she was, “(s)tanding here as my mother’s daughter, and my daughter’s mother, I’m so happy this day has come.6”

Hilary Clinton’s success as the nominee and de facto leader of the Democratic party was only a partial depiction as to how far women had come. 2016 also marked the entry of a powerful cadre of diverse women to the halls of the US Senate. While Clinton’s campaign for president was ultimately unsuccessful, electoral success came for the likes of Kamala Harrris, Tammy Duckworth, and Catherine Cortez Masto. These women joined forces with powerful senatorial mainstays like Elizabeth Warren D-MA (first elected in 2012), Amy Klobuchar D-MN (elected in 2006), Barbara Mikulski D-MD (elected in 1986), and others following the 2016 election cycle. According to Rutgers University’s Center for American Women in Politics (CAWP)7, a total of 105 women representing both political parties held seats in the United States Congress, reflecting 19.6% of the 535 members. Among the 105 congressional leaders; 21 women (21%) serve in the United States Senate, and 84 women (19.3%) serve in the United States House of Representatives. Not included in the count were the additional five women who served as delegates to officially unrepresented US territories and districts (American Samoa, the District of Columbia, Guam, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands) co-located in Congress’ House of Representatives. While there remains mixed opinion about the overall success of the 2016 election cycle on women’s political leadership, it is undisputed that the election outcomes galvanized women to run for elected office and/or support pro-women legislation. According to one 2017 Washington Post article, EMILY’s List, the political action committee that recruits and trains progressive women political candidates reported at one point that over 11,000 women representing all 50 states had expressed interest in running for political office8.

While Hilary Clinton’s campaign was ultimately unsuccessful, the presidential campaign served as a catalyst for a new and powerful cultural transformation in the context of US gender relations. The ignominious moment when Clinton’s then-opponent, Donald Trump was caught on camera bragging about his keen ability to “grab p∗∗∗y” served as a powerful political and cultural inflection point for women as longstanding issues like sexual assault, women’s self-determination and sexual autonomy coalesced into a new form of gendered consciousness within the United States that would eventually be captured in the soon-to-evolve “#MeToo” movement that followed. Powerful cultural and political moments like Beyonce’s visual album/short, “Lemonade” and First Lady Michelle Obama’s speech on rape culture further captured the country’s imagination by placing female strength and resistance at the forefront of the national conversation on gender and gender relations. Likewise, new feminist voices also emerged in 2016, changing, expanding, and redefining how we come to think about women in US society. The award-winning Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, for example, released her book entitled, “We Should All Be Feminists”; a treatise calling for a more pluralistic feminism that would be needed in order to reflect the diverse needs of modern women in today’s society. Likewise, Roxanne Gay spoke equally as powerfully in 2014 and then later in 2017 about the importance of valuing the alterity of diverse women’s lives. Whether it be trauma, body image, sexuality, or race, Gay brought new expression to difference – and importantly, to the dignity of such difference in the wake of prevailing and often oppressive societal norms.

In this same period, the Economist published its fifth annual “glass ceiling index” combining data on higher education, workforce participation, pay and representation in senior jobs into a measure of where women have the best and worst chances of equal treatment in the workplace (Data Team, 2017). The United States was listed well below the international average with 63% of women participating in the US workforce yet representing a little over one third of the well-paid, high-status jobs. Similarly, AASA reported in 2015 that women made up 76% of teachers, 52% of principals, and 78% of central-office administrators, but only accounted for less than one quarter of superintendents leading the nation’s 14,000 districts (Finnan et al., 2015).

In sum, we can perhaps best describe the political and cultural moment of 2016 as a grappling process over women’s place in public and private life. It also represented a harbinger for the normative shifts to come as later depicted in the #MeToo movement that was soon to follow. Importantly, these conversations were not limited to white, heteronormative, women, but was increasingly inclusive of a wider diversity of voices, experiences, and positionalities. It’s against this backdrop that we administered the WASA survey and 133 women reflected upon the state of the superintendency for women.

WASA Women’s Perspectives on Barriers: Comparing 1993, 2007, and 2016 Cohort Responses

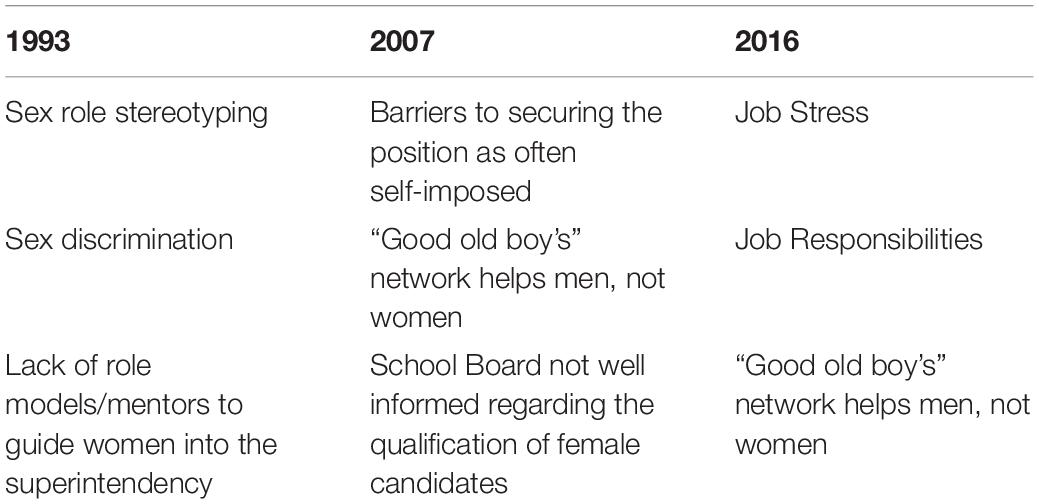

In order to understand the interplay between historical time and place and the perspectives as shared by our WASA respondents, we must place their understandings in the context of prior cohorts. Table 2 offers a comparative snapshot of the top three barriers to the superintendency as named by the three responding cohorts (1993, 2007, and 2016). What’s immediate obvious is that perceptions over what has served as barriers is consistently different across the three cohorts.

In 1993, the three top barriers identified (“sex role stereotyping,” “sex discrimination,” and “lack of role models/mentors”) mirrors in many ways the sociohistorical context of the time. As we know, women maintained only a marginal presence in top district leadership. Moreover, our understanding both empirically and anecdotally of the forces that resulted in this gender imbalance was emergent and largely focused on the underlying biases that inhibited women’s advancement into any number of senior leadership positions across any number of fields. Interestingly, when looking at the combined barriers identified by the 1993 group, the emphasis is on inadequate structures of support and gatekeeping.

By comparison, the 2007 cohort tells a somewhat different tale. This group named their top three barriers as being (1) self-imposed; (2) a product of women’s outsider status; and (3) a product of a school board failure. Once again, we see a recognition of gatekeeping as a barrier to access. What’s most interesting about the 2007 responses, however, is the selection of “self-imposed barriers” as a foremost constraint, indicating a sense of individual agency over whether women are able to access superintendent positions or not.

Finally, the cohort of greatest interest to this study, 2016’s 133 respondents named (1) job stress; (2) job responsibilities; and (3) Good old boy’s network as their top three barriers. These barriers reflect an emergent connection first alluded to by the 2007 group between professional access and agency. In this case, however, the 2016 cohort have taken it a step further by suggesting that the constraints on their entry into the superintendency aren’t a product of gender-based bias or an unlevel playing field. Rather, the named barriers are instead a reflection of the normative conditions of the position. In other words, women within the 2016 cohort found that the challenging aspects of advancement into the superintendency remained fundamentally structural. However, these structural constraints aligned with the actual conditions of the position rather than actual barriers to access. This suggests a far more intrinsic understanding of the barriers that exist for women as it suggests that women may no longer see themselves as “frozen out” of a district leadership role as much as the role may not, in their minds be a good fit (due to stress and/or duties as assigned). While this rationale certainly seems feasible given the barriers identified by this cohort, it’s also notable that “good old boy’s network” continues to appear as a top constraint across all three cohorts. Clearly, there is still a belief that women remain outsiders to this most senior leadership position. Whether this is a product of the significant and ongoing underrepresentation of women to the position is unclear. However, it’s notable that, while attitudes may be shifting about a woman’s potential as a district leader, questions remain over the fairness of the system and the potential gatekeeping that may result in kind.

Table 3 outlines the identified factors that contributed to whether an aspiring woman would pursue the superintendency. This question focused less on barriers or constraints to entry for women and more on the ideal conditions that would be required for entry into the profession. Comparative data from across the three cohorts finds that there is only one common condition identified, namely the need to ensure a good match between individual and the hiring district (noted in gray). This would seem reasonable given the high stakes nature of the position and the commitment, both in time and in energy, to such a demanding position. Comparing across cohorts, we also find that the 1993 and 2007 groups identify strikingly similar conditions for pursuing the superintendency. Besides the question of match, additional choice factors identified by both groups include, “stable and visionary/proactive board,” “stable financial outlook for district,” and “potential for district success is good.” Through their selections, the 1993 and 2007 cohorts appear to emphasize the alignment of different district-level factors to decision-making. In a slight departure from this, the 2016 cohort focus, once again, on the alignment of individual choice factors, i.e., spousal employment opportunities, professional growth, the opportunity to follow in the footsteps of talented district leadership9.

Tables 2, 3 provide some interesting distinctions in terms of the 2016 cohort’s list of identified barriers to entering the superintendency. Both tables suggest that 2016 respondents are less afraid of gatekeeping constraints than they are of fit and match. As such, the idea of the superintendency (and their chances of assuming such a role) are more contingent upon their own assessments of the position as opposed to believing that such decisions are outside their control. In this way, we see a shift from barriers as extrinsic challenges to named barriers as fundamentally intrinsic determinations. Based upon the momentous shift reflected in the current historical moment for women (i.e., Clinton nomination, increases to female political leadership, #MeToo), it should come as no surprise that women were increasingly more optimistic, empowered, and open to the possibilities of career advancement – and particularly in historically male-dominated domains. The existing social norms, while always evolving and dynamic, offered in this case an expansion in what was possible for women in their private and public worlds. It follows then that the professional decision-making operates as a reflection of the historical time and place in which these decisions occur.

Timing in Lives

Elder (1998, 2005), Elder et al. (2003) speaks of the second principal, “timing in lives,” as a function of individual context and timing. When placed in the context of such things as career and career choice, timing becomes particularly salient to decision-making. When, how, and where we are in our lives inevitably drives individual level assessments over what career options are possible, the palatability of risk-taking, degrees of self-efficacy, and so on. Therefore, it is important to consider how timing may also drive women’s perceptions about the superintendency. To what extent does timing factor into feasibility for these women?

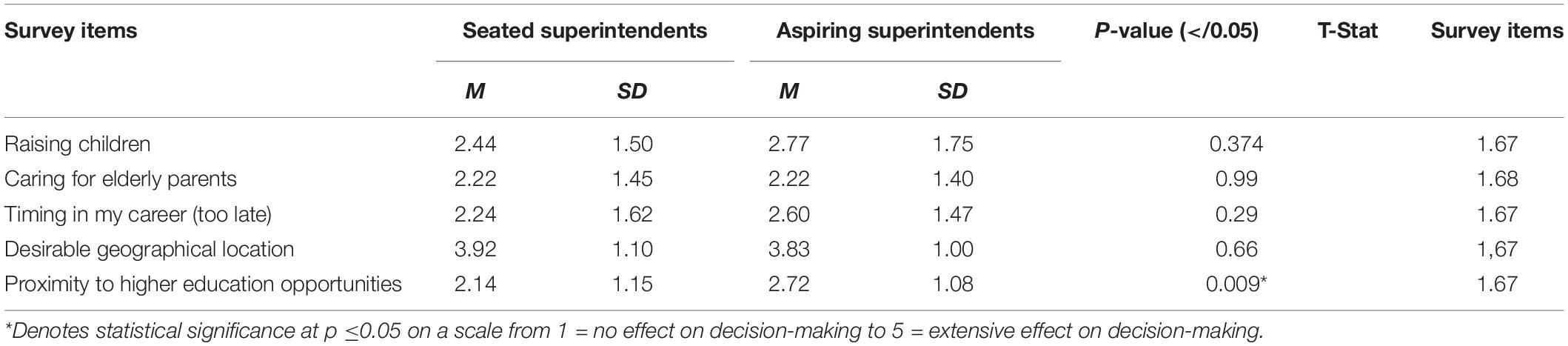

To answer these questions, we considered a number of survey items that took into account a host of timing considerations. We summarize these items in Table 4 below:

Each of the items identified reflect key intersections between women’s private and professional lives. Importantly, however, they also reflect moments in which the private may impact and/or supersede the professional. The timing speaks to key moments in the lifespan where familial obligations may be greatest. This is commonly the case for women who are cast in the role of caretaker to immediate and/or extended family.

What are the timing factors of greatest concern to seated superintendents? One not so surprising result was the issue of geography. “Desirable geographical location” stood out as the biggest factor in their decision-making with a mean score of 3.92. This was, in fact, the only factor in which seated superintendents appeared to eclipse their aspiring counterparts. This may be suggestive of any number of things: location is more critical to seated superintendents assessments over what’s may be of greatest benefit spouse or offspring, quality of life concerns, or perhaps considerations related to the make-up or proximity of a particular community. The second greatest impact factor for seated superintendents was “raising children” followed by “timing in my career.” Given that women are so often called upon as caretakers, it should be no surprise that these factors are most concerning to women superintendents.

When we cross-reference the identified factors of seated superintendents with those of aspiring superintendents, we see some notable patterns. For one, aspiring superintendents are concerned with very similar things as their seated counterparts, particularly given that most mean differences between our two comparison groups were not statistically significant except in the case “proximity to higher education opportunities.” One could surmise that aspiring superintendents place more value on being closer to higher education institutions for any number of reasons, including the need for continued training/professional development. What we learn from these findings is that timing does indeed seem to matter to women when assessing barriers to advancing into a superintendent role. “Timing in Lives” gives recognition to the role that the life cycle plays in career determinations as it places emphasis on life context as a factor. Likewise, it is also a point at which internal tensions over private commitments may shape and inform professional choices. In the case of seated and aspiring women, the timing of decision-making is an important consideration en route to the superintendency.

Linked Lives

Relational interconnectedness is a valuable feature of our social and intimate lives. How we draw connection from others often has direct bearing upon, not only personal well-being, but on our professional successes as well. To this point, research on the benefits of networks and interconnectivity to career pathways and advancement speak to the multiple ways our social ties render tremendous personal and group benefits (Seibert et al., 2001; Feeney and Bozeman, 2008) and especially so in the case of women (Ibarra, 1993; Perriton, 2006; Wang, 2009; Friebel et al., 2017). These benefits include such things as reassurance and trust in others, a sense of belonging, information sharing, reciprocity, and opportunities to create expanding ever more extensive networks and network ties (Coleman, 1988; Putnam, 2000; Seibert et al., 2001; Friebel et al., 2017; Lin, 2017). In light of these known advantages, how women place value, sustain, and rationalize particular relationships speaks to the ways in which relationships inform how they may make sense of the superintendency.

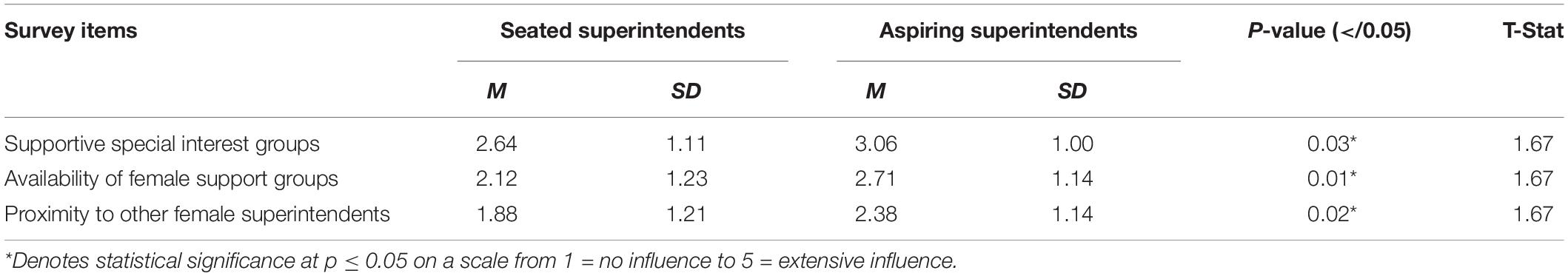

Table 5 provides a summary of items that details how connection and connectivity factor into the decision-making of seated and aspiring superintendents. In the case of seated superintendents, relationships with key individuals and groups play a less of a role in terms of what they deem favorable conditions for success within a district. In the case of the three different relational connections assessed by respondents, special interest groups, female support groups, and/or other female superintendents, seated women believed special interest groups of greatest value to their professional success. By contrast, aspiring superintendents view support special interest groups as having an outsized role in a superintendent’s success. This may be in recognition of the importance that such constituencies can have on overall district performance. Likewise, it may be that aspiring superintendents are less aware as to how female colleagues/supporters may be able to support their successes once they are installed in a superintendent role. Nevertheless, it remains interesting that, at least in the case of aspiring superintendents, there are dramatic differences over which linkages are of greatest value as compared to those of seated superintendents. Whether these differences are a product of abstract versus experience- based understandings of needed support is certainly a question for further consideration.

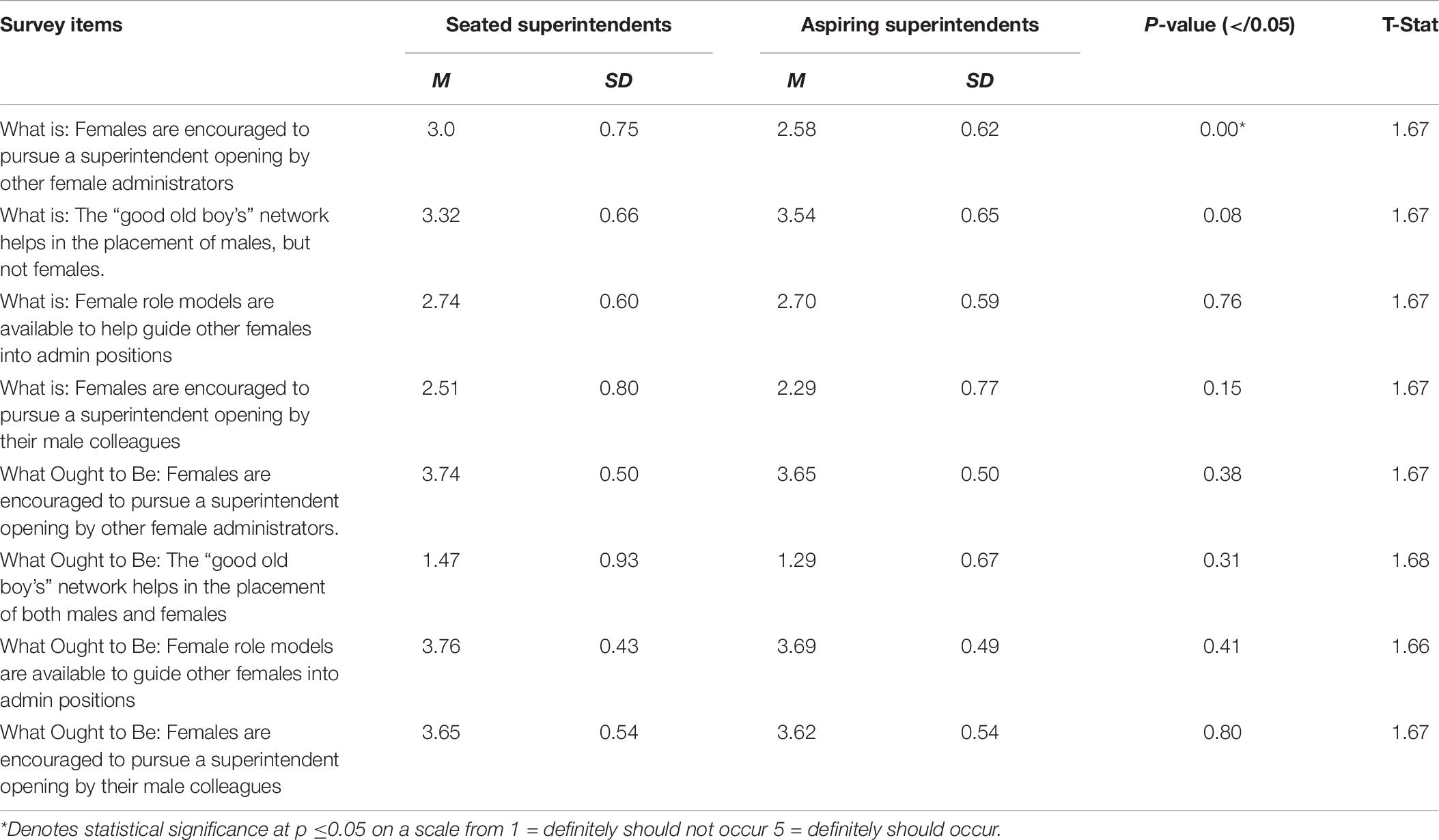

Also notable is the fact that the differences between the two groups were statistically significant across all items. Such an outcome is not surprising given that aspiring superintendents would naturally assume that diverse networks would be an asset to entering an otherwise competitive job market as well as to receiving the necessary supports for success once hired. Table 6 summarizes the outcomes of the discrepancy model questioning embedded in our 2016 survey instrument. With these questions, we not only sought to have respondents name barriers, but to also offer their sensemaking around the current state of “accessibility” for women to the superintendency. To this end, we had them assess what is the state of accessibility on a number of different dimensions for women seeking the superintendency. In juxtaposition to what they perceive to be the current state of things, we also asked them to assess what should be in order for there to be a level playing field for women in navigating the precarious pathway to the superintendency. We discuss these sets of findings in turn.

When analyzing the current state of the superintendency for women, seated as well as aspiring superintendents are in general agreement as to what they view as relational resources considered to be most effective to supporting and/or curtailing women’s district leadership success. Examined closely, one of the important patterns of note relates to women’s rather dim view of men as supporters of women’s advancement to the superintendency. Both very clearly view the “good old boy’s” network as a constraint on women’s access to district leadership roles. Likewise, there appears to be a consensus that women do not readily receive male support and encouragement. Taken together, it seems that women continue to see male dominance within the field as an ongoing barrier to entry for women. This finding is not surprising given the large-scale gender disparities among current superintendents and in school board membership. Interestingly, in contrast to the findings presented in Table 5, seated and aspiring superintendents seem to disagree as to the extent to which current women leaders identify (“tapping”) and encourage emergent women leaders. While seated superintendents felt that women leaders were helping to advance other women in the field, aspiring superintendents did not feel similarly. We may be able to explain this in any number of ways. First, seated superintendents are perhaps more personally aware of this type of support given their own experiences in successfully advancing to the superintendency. They may also be more aware of their own efforts to support other aspiring women. While the current state of female-to-female leadership tapping may be in dispute, both groups appear to agree strongly that such support should exist. It should also be noted that, while not an overwhelming response, both seated and aspiring superintendent groups felt that women, regardless of role, generally supported one another’s aspirations and that such support should ideally continue.

In the case of “what ought to be” we again see some interesting patterns as to what women’s view as important relational resources for their success. While our findings seem to suggest that, for the women surveyed, the current state of the playing field may be one in which male support falls short of expectation, these women are not necessarily letting men “off the hook.” In fact, the evidence suggests the opposite. In looking at the results in their totality, what we see is an interest in male advocacy. For both seated as well as aspiring superintendents, it’s clear that male support is a necessary condition for women’s career advancement. Perhaps more interesting still, the women surveyed seem to suggest that women’s advocacy of other women is even more necessary to their success. Why this is the case may be explained in any number of ways. Perhaps those surveyed view women’s advocacy and encouragement as necessary to ensuring women’s advancement into senior leadership roles. In this sense, women believe that women leaders should maintain a sense of obligation to supporting other aspiring women. As such, it is perhaps even more imperative that they be outspoken in their support of others.

In sum, we see that connectivity is an important frame of reference for understanding how women come to view the barriers before them. Support, encouragement, and advocacy are critical benefits that come from diverse sets of relationships. Based upon the evidence presented, how and in what way those benefits are rendered has bearing upon women’s perceptions over what is possible in terms of career advancement. It follows that the notion of linked lives plays an important role in how these women perceive the playing field and what they view as needed for their success.

Human Agency

The fourth and final principle of human agency suggests that individual determinations over “what is possible” is in many ways dictated by the historical moment we’re living in. Social norms, expectations, cultural values all shape and inform how we go about determining our existing sets of options. Rational decision-making is therefore an assessment over what is of greatest benefit to us individually or in service to others. In terms of career decision-making the principle of human agency is expressed as an individual assessment in which the individual makes determinations over what will enhance his/her chances for career success. As Elder (1998, 2005), Elder et al. (2003) suggests, these “agentic determinations” are profoundly influenced by the historical moment in which decisions are made. For example, determinations over the ideal organizational structures, personnel mix, district leadership legacies, politics, financial outlooks etc. are informed by shared, collective thinking over what makes for an ideal setting and working context.

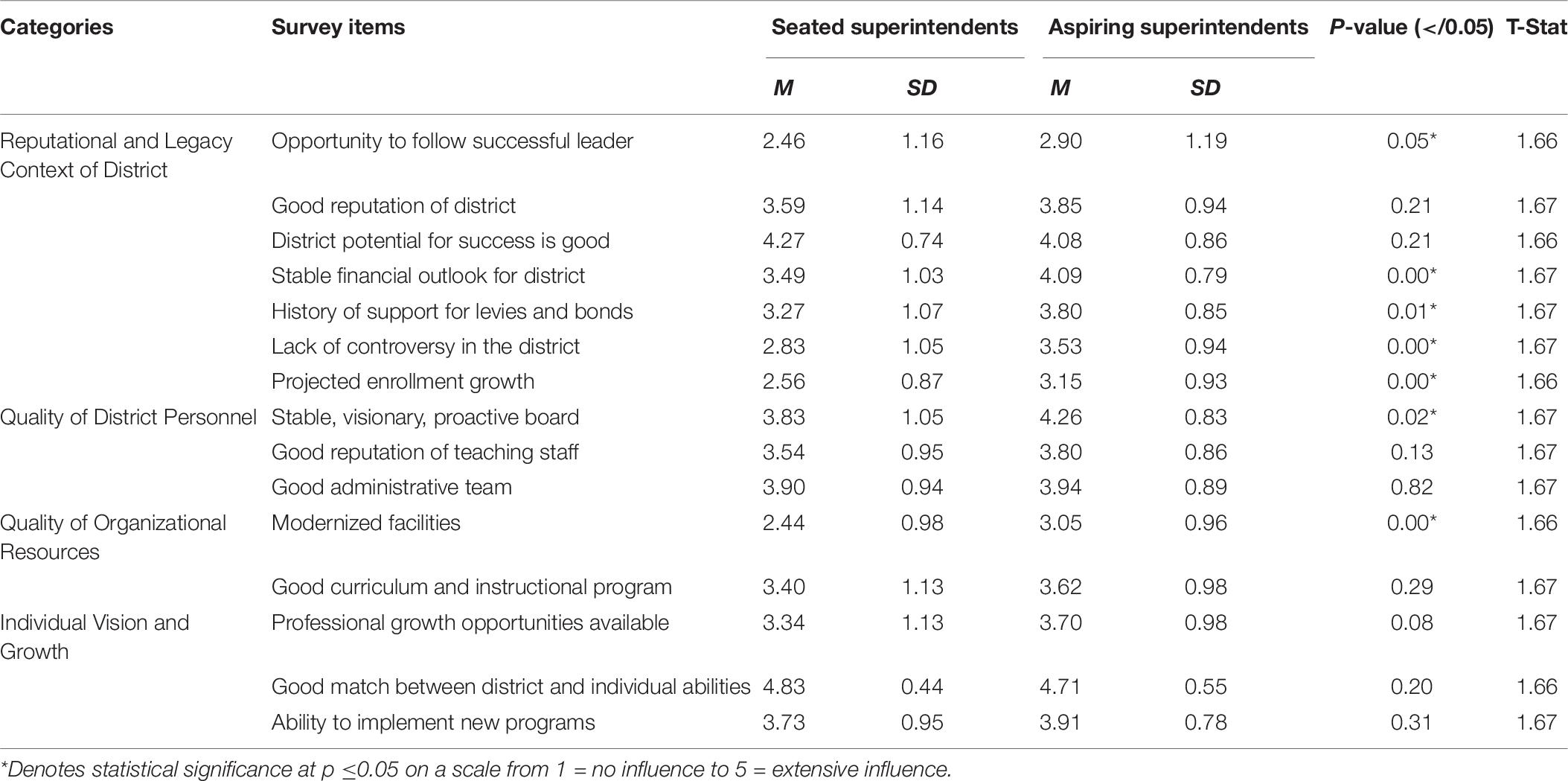

What are the ideal work contexts as identified by our 133 respondents? Table 7 provides a summary of key items that represent district-related conditions that weighed upon both seated and aspiring women. Items were categorized into four separate domains, (1) Reputational and Legacy Context of District”; (2) Quality of District Personnel; (3) Quality of Organizational Resources; and (4) Individual Vision and Growth. Looking at each domain individually, we are able to identify key patterns related to how seated and aspiring superintendents engage in “agentic determinations” related to their assessment of optimal conditions for district leadership success.

Table 7. Comparison of seated and aspiring superintendents determinations over district conditions for their success.

Reputational and Legacy Context of District

The first domain focusing on district reputation and historical legacy has respondents weigh in on a number district reputational concerns they would consider if given an offer of employment. The two items most commonly selected among seated and aspiring superintendents are, unsurprisingly, “district potential for success is good,” good reputation of the district,” and “stable financial outlook” albeit in different ranking order. Certainly, this speaks to the common assumptions regarding the importance of smooth transition and optimal conditions once engaged in the on-boarding process. One finding of note was the extent to which the aspiring group found “stable financial outlook” to be an important feature of a district. Mean differences on this measure were significant compared to their seated counterparts. While there could be multiple reasons for this, the most obvious rationale would be to suggest that orderly district finances are critical to an incoming superintendent’s short and long-term success.

Interestingly, the item reflecting the greatest difference of opinion between seated and aspiring superintendents is “projected enrollment growth.” While it’s unclear how or why this factors so differently for the two groups, one might suspect that aspiring women may be interested in seeking out districts that are able to demonstrate long-term growth and/or financial health. In addition to projected enrollment growth, we see additional differences related to the degree of prior “controversy in the district,” “history of levies and bonds,” and once again, “stable financial outlook.” Clearly, these items are of greatest concern to aspiring superintendents as these mean differences emerged as significant by comparison to the seated group.

Quality of District Personnel

Quality of District Personnel appears to be an important domain for both populations of women respondents. Here we see the role that the existing human capital of a district plays into the assessments over match and fit. The data seems to indicate that aspiring superintendents place a higher value on stable and visionary school boards above all other personnel groupings. This outcome may be either the result of perceived anxieties by aspiring women given the high stakes associated with the school board-superintendent relationship or perhaps as a harbinger of district growth and possibility. We see greater value given by seated superintendents to the quality of the district administrative team, suggesting a prioritization on the quality of available support to carry out short and long-term planning and vision.

Quality of Organizational Resources

The third domain of particular interest to the respondents focuses on the quality of organizational resources. This domain considers the importance of physical resources to our respondents’ determinations over the necessary conditions for their success. We see that “modernized facilities” appears as the one significant difference between groups, with aspiring superintendents placing greater emphasis on the condition of districts facilities as compared to current superintendents. That said, both groups indicated a high degree of emphasis on good “curriculum and instructional programs.” It may be that this is a product of what prior research has considered women’s continued association with curriculum and curriculum-related issues (Brunner and Kim, 2010).

Individual Vision and Growth

The final domain focuses on individual vision and growth. This domain includes the most frequently cited conditions for success between the two populations of respondents. Certainly, the importance of individual growth opportunities speaks to the value placed on fit and match when entertaining district employment offers. Second to concerns around match is the “ability to implement new programs.” This is an interesting finding in that it suggests once again that the potential for district growth, innovation, and success are important considerations when women weigh district employment offers. Fit and potential for district growth/success speaks to a notable shift from extrinsic to intrinsic control over what they need to ensure their success as district leaders.

In sum, agentic determinations over the conditions for career success are consistent across the two groups. What we see is that women, both seated and aspiring, have some minor differences in areas related to finances and prior/current governance. However, there is general agreement as to the link they make between a district’s overall position and the likeliness of success for an incoming superintendent. What’s clear from these results is that agency comes from their understanding over what they have intrinsic control over. Likewise, agency also comes from an awareness of the social and normative conditions of school districts and their awareness over the importance of fit and match. This is a marked distinction from the 1993 and 2007 cohorts before them.

Discussion and Implications

On the whole, our findings indicate shifts over time in the types of barriers that have limited women’s entry into the superintendency, Findings from Sharratt and Derrington’s original 1993 survey results, for example, identified sex role stereotyping, sex discrimination, and lack of role models/mentors as the three main barriers to access. By comparison, our analyses of the 2016 data suggests the main barriers to be factors related to job stress, the unappealing nature of the job responsibilities, and the “good old boy’s” network. We argue that these shifts in attitudes around the superintendency are a direct reflection of the historical contexts that drive individual level decision-making for these women. Put simply, the historical times matter and these now documented attitude shifts form the basis for our study’s conclusions.

It should also be noted that comparisons between seated and aspiring superintendents suggest a good deal of agreement between the two groups on such things as the relative importance of timing to a woman’s decision over when to enter into the superintendency, the importance of networks and social connections to successfully navigating paths to the superintendency, and what these women perceive to be the most favorable district-wide conditions for both their short and long-term success. While these two groups of women are in very different places in the career trajectory, the uniformity of response suggests that historical context has a place in the process by which women make their life choices. Where historical context may offer its greatest inflection, is in the shared perspectives and collective sensemaking Elder et al. (2003) spoke of in his articulation of life course theory.

Our findings also suggest that the principles of life course theory provide a robust way to analyze women’s professional choices. In the case of our 2016 cohort responses, we were able to deconstruct the data according to each life course principle, and could more clearly see points of agreement and disagreement regarding the barriers and challenges as well as the misconceptions and myths of the superintendency as expressed by our women respondents. When using the life course theory principle of “timing in lives” as a lens, for instance, there is evidence to suggest that timing is salient to the professional life choices of these women, particularly when placed in the context of women as the historical caretaker. In this case, timing has the potential to constrain a woman’s choice to enter into a superintendency position or not. These findings are also echoed in prior work by Hill et al. (2017) where women shared their concerns over moving school age children, having husbands unable to relocate because of their employment, worrying about their current age and whether it would be a good move financially.

In sum, life course theory and research alert us to this real world, a world in which lives are lived and where people work out paths of development as best they can. It tells us how lives are socially organized in biological and historical time, and how the resulting social pattern affects the way we think, feel, and act (Elder, 1998, 2005; Elder et al., 2003).

Study Implications

Given the inextricable link between the world of work and the socio-historical contexts that inform perceptions of that work, we need additional longitudinal studies on the superintendency in order to understand changes in aspiring females’ perceptions over time. This study was able explore to how a cohort of women perceived accessibility to the superintendency to key aspects of a woman’s life cycle and life history. However, future studies could take this approach a step further by establishing more direct causal links between women’s professional work choices and normative contexts for those choices. In addition, further studies might examine perceptions of aspiring male superintendent candidates so that differences and similarities between males and females might be investigated.

The particular contributions of this study, however, lend to deepened understanding of the role that life history has in the formation (and execution) of superintendent pathways for women. As our findings seem to indicate, regardless of the historical contexts, women school leaders are still susceptible to the dichotomization of their life and professional choices. The demands of home often circumscribe aspirations. Pursuant “mythologies” around the superintendency role continue to constrain women’s option sets to an either/or Sophie’s choice between family and profession.

In conclusion, we posit the following recommendations for how the field might influence women’s life choices in such a way as to increase the overall number of women superintendents.

Highlight the Stories of Successful Women Superintendents and the Life Course Strategies That Have Enabled Them to Combine Work and Family

Just as our findings seemed to suggest, establishing connections between seated women superintendents and the next generation of aspiring district leaders is critical (Wallace, 2014). This may come through direct encouragement or by modeling life balance. Seated women superintendents who have chosen to be both superintendents and mothers have found creative ways to manage the conflicts resulting from combining parenting and superintending. While research tells us that the overwhelming responsibility for managing family falls largely on women10. Successful female superintendents have found ways around this. Some have worked with family to transfer responsibility to spouse and children. Others have relied on parents and grandparents to assist with family responsibilities. We expect that highlighting women superintendents’ life choices and life strategies, and giving public voice to their life journeys will provide successful models for aspiring female administrators. Opportunities for women superintendents to tell the stories can be offered through professional development programs, networking infrastructures, and publications.

Reframing the Negative Mythologies Associated With the Superintendency

The superintendency is so often talked about in negative terms. This negativity does a disservice to the many superintendents who love their work and revel in the opportunity to support children. Effective superintendents are visible and engaged school and community leaders. We argue for viewing the superintendent’s job as a composite of school and community tasks and responsibilities, and moving away from the notion that the job requires uninterrupted and unending seat time that precludes family time. These myths only serve to dissuade women from seeking the superintendency. Work autonomy and work-time flexibility can help to offset the substantive demands of the superintendency.

We posit that successful early and mid-pipeline administrators have demonstrated a skill set that uniquely qualifies them for the superintendency (Ward et al., 2015). Their female colleagues who serve in the role need to demystify the job and present it in ways that highlight the rewards—which often more than offset the investment required to pursue higher degrees and certification. They need to highlight the personal satisfaction and joy that comes from influencing an agenda for the benefit of all children.

Women Need to Form Networks to Mentor and Tap Other Women in Early and Mid-Career Stages to Influence Life Choices in a Positive, Timely Fashion

Mentoring and “tapping” are critical to recruiting talented women to enter superintendent preparation programs. However, mentorship from senior level professional peers is not always available. Or it often comes too late to allow women to make the prerequisite life choices necessary to pursue the superintendency. All too often, we see that male leadership mentoring fails to account for the different types of demands placed upon women. Likewise, male leadership “tapping” may or may not be inclusive of women who could be excellent candidates for the superintendency. The implication of these findings is that the focus on women’s career development needs to address the advancement of women through mentoring programs with specific emphasis on and awareness of gender related issues and the life choice decisions implicit with these issues. Women superintendents need to support and advocate for their female colleagues as they make critical life choice decisions that will either move them toward or away from the superintendency.

Design Superintendent Certification and Doctoral Programs in Such a Way That Early and Mid-Career Women Administrators Can Participate While Balancing the Demanding Roles of Family and Work

Doctoral and credential programs need to be coordinated in order to provide an opportunity for candidates to complete programs in an efficient and timely manner. Programs should schedule offerings in ways that minimize time away from family and work. This might include weekend seminar formats, on-line options, and summer session flexibility.

Design Superintendent Certification and Doctoral Programs to Provide Maximum Opportunity for Job Embedded Learning and Network Building