- 13rd High School of Argyroupolis, Athens, Greece

- 2I.E.K. Ilioupolis Public Vocational Training Institute, Athens, Greece

The introduction of sustainability education into the educational reality in recent decades to raise student’s awareness of environmental, social and cultural issues has gradually led to a change in the perception of school as an organization at all levels of its function. The traditional approach of school is receding and the concept of sustainable school is emerging, transforming school into a factor of change of attitudes and behaviors, into a major lever of transforming society toward sustainability, leading to the revision of leadership and organization views. In Greece, sustainable school is a utopian image in an ideal society. The efforts made are fragmented and incomplete, as the narrow legal framework which is determined by the state. A number of practices are strictly followed on issues that cover the whole spectrum of the educational process, such as the appointment of school principals, teacher placements, teaching instructions, funding and financial management of the school unit, limiting the margin of the school administration to achieve a sustainable use of the available resources in order to continuously develop and improve school as an educational organization. The Greek educational system, through the uniformity of laws in all its fields, inhibits the implementation of sustainable school by lifting cobblestones and obstacles that this article attempts to illuminate.

Introduction

Sustainability has become an essential issue for an organization as it is directly linked to every aspect of human activity. Behaviors consistent with sustainability have been adopted by organizations at an increasing rate given the economic recession that has occurred in most countries (Audebrand, 2010), including Greece. Since the beginning of the century educational organizations have been turning to sustainability, initially focusing on its environmental component and then on its social and economic one. Tertiary education institutions around the world have already been following sustainable practices as, besides their environmental concerns, they look forward to gaining competitive advantage. Secondary and primary education institutions have followed suit, too. In Greece, prospects of sustainability are not integrated into the administrative responsibilities and strategic orientation of school units. This fact has its roots in the character of the Greek educational system and its philosophy regarding the position and responsibilities of the school head.

The Greek school principals as well as the school teachers have a reduced capacity of intervention in the operation of the school unit (Kaparou and Bush, 2015). The number of laws, the gap between the legislation and its practical application, contribute to this (Saiti, 2009). In Greece, principals usually want teachers to be involved in the decision-making process, but they are limited to executing orders (Papakonstantinou, 2008). In the Greek school there is a lack of communication between the staff of the unit leading to the degradation of the school climate (Liberis, 2012). Formalism leads to a reduction in teacher performance (Iordanidis et al., 2010). The evaluation of the school unit and the work of the principal are insignificant as the educational and administrative functions such as the appointments and detachments of teachers, the selection of principals etc. are determined by the central government with formal criteria (Saiti, 2009; Matsopoulos et al., 2018).

The implementation of sustainability is also sought in education, and this can only be accomplished when the organization is run by a visionary leader, able to inspire and defend the organization’s perspective (Christofi et al., 2015). Sustainable leadership presupposes the participation of teachers in decision-making and their implementation. It requires long-term planning and implementation so that the school as an organization can interact with its external environment (Dyer and Dyer, 2017). The school, regardless of its needs, must implement the instructions of the central administration and not adapt them. The principal is responsible for the observance of the official orders and the teachers for the implementation of the educational policy without deviations from the central line (Polyzopoulou, 2019). This study aims to present why the principles of sustainable management are not followed by the head teachers of Greek schools through the examination of the structure of the Greek education system and the norms that organize it. It focuses on specific educational and administrative practices followed by the Greek educational system and demonstrates the role they play in inhibiting the implementation of sustainable leadership.

The Concept of Sustainability

The concept of sustainability signifies a broad approach of the balance between the framework of human activity and the quality of the environment. Contemporary understanding of the concept derives from the Brundtland report, which states that the present generation should manage natural resources in such a way so as to meet its needs without, however, depriving the next generations of this possibility based on equality and justice. The interaction between three different pillars, the environment, economy and society plays a dominant role for sustainability. Environmental sustainability is the maintenance of natural capital through rules of production and consumption of goods. It defines a set of limitations for the human economic subsystem that regulate mainly the use of renewable and non-renewable sources (Goodland, 1995). Social sustainability refers to the preservation of the characteristics of a society that compose the values, attitudes and culture of individuals focusing on areas of social life such as participation in decisions and actions, human rights and the total of the components that generally constitute the “social capital” (Dempsey et al., 2011). Economic sustainability does not follow the conventional definition of the economy or economic development as it is not cut off from society and the environment. It interacts with them; it does not define them but participates with them in a common way. In addition to the traditional three pillars, bibliography advances the adoption of three new pillars: the cultural pillar or the pillar of cultural diversity, the political or institutional pillar and the spiritual pillar (Leal Filho et al., 2015). The complexity of the issues that sustainable development approaches is an inhibiting factor in its understanding and that makes its accurate description impossible (Tilbury and Stevenson, 2002).

The Interaction of Sustainability Pillars

The tri-partite model of sustainability supports the interaction between its three pillars, through balances and compensations, as they are considered to have distinct boundaries (Purvis et al., 2019). The synergy of the pillars requires the participation of theories and techniques from diverse domains of knowledge as sustainability is an interdisciplinary field that aims at problem solving (Leal Filho et al., 2015). Environmental problems are not static but mainly represent social problems that have economic and institutional aspects while their solution leads to a holistic culture that is structured by pre-existing knowledge that is integrated into the conceptual framework of a sustainable society (Munck and Borim-de-Souza, 2012). Every aspect of human activity is organized by the interconnected principles of sustainability. For example, environmental quality and biodiversity in an area allow, through tourism, the economic growth of the local community and consequently its balanced social development (Hansmann et al., 2012). Similarly, the conservation of fish stocks in one area can lead, via rational fisheries, to the holistic development of the local community (Asche et al., 2018). Similar synergies between sustainability pillars at the urban level are reported to the literature, having at the forefront the organization of offices and the use of mild forms of transportation (Vyas et al., 2019). The holistic approach is gradually gaining ground in the organization’s viability such as companies, universities and non-profit organizations. The three pillars converge on the formation of organizational abilities that lead to the social-economic development of the organization with respect to the environment (Munck and Borim-de-Souza, 2012).

The Sustainable School

The decade, 2005–2014 was named by the UN as “Decade of Education for Sustainable Development (DESD).” Sustainability Education (ECD) has adopted a new philosophy that supports participation of the entire school community, an approach called the “whole school approach.” It consists of innovative practices and involvement of the school unit in environmental and social issues, essentially exceeding the narrow boundaries of the traditional curriculum and making its change or radical restructuring imperative. In the context of transforming the philosophy of the school as an organization, new concepts emerge, such as co-operation to achieve common goals and new values and attitudes, as well as changes appear in various aspects of the educational process, such as school leadership or school infrastructure. This trend, briefly described as “sustainable school,” is considered as the complete implementation of the three pillars of sustainability in the school community. Achieving organizational sustainability supposes the adoption of sustainable practices in a numerous themes regarding school as organization, as the engagement of the employees in a common sustainable path (Samul, 2020).

The Sustainable School Approach Levels

The Sustainable School Approach extends to four levels (Mogensen and Mayer, 2005) that combine the well known three pillars of sustainability in addition with cultural and spiritual pillar.

(a) Cognitive – Pedagogical. It provides the necessary knowledge and skills that lead to critical thinking and as a consequence sustainable-friendly attitudes and values that are adopted. It promotes interdisciplinarity and focuses on recognizing and resolving the problem.

(b) Educational policy and school organization. It cultivates the will to communicate and participate not only among students but across the school community. Participation in decision-making leads to the differentiation of relations between students and teachers, promoting experience in democratic processes, mutual respect and cooperation.

(c) Infrastructure, resources. Changes are made to the building’s equipment and construction to reduce its environmental footprint. An effort is made to use renewable energy sources while it is involved in the management of natural resources and waste through sustainable approaches such as recycling.

(d) The cooperation networks and external relations developed by the school.

In a learning organization, leader’s role differs from that of the charismatic decision maker. School leaders are designers, teachers, and referees. Supovitz et al. (2019) argues that the ability to build shared vision, the formation of influence without the use of power is required by the head teacher. In sustainable management, the school principal knows the material and human resources at his disposal and uses them to improve the school (Clark, 2017). With his/her personality and skills, he/she encourages all members of the school community to engage in improvement practices while creating a climate of trust, honesty, and acceptance. It promotes participation in decision-making processes by skillfully handling possible conflicts that arise as the creative forces necessary for continuous improvement are released (Supovitz et al., 2019). According to Blewitt (2017), the head teacher must communicate not only vertically but also horizontally while believing that the innovation from below should be encouraged. He/she creates a cognitive environment that goes beyond the formal curriculum and the rigid instructions of the central management. Finally, he/she promotes the school’s communication with its external environment.

In countries such as Britain (Sustainable Schools) and Australia (Australian Sustainable School Initiatives, AuSSI), sustainable school is implemented in cooperation with the central education administration. Studies on teacher reeducation are funded; educational material is included in the curriculum, as well as participation in actions of local and wider society. The linkage of the school as an organization with local social actors is promoted while emphasis is placed on issues such as natural resource management, equality, equal opportunities, poverty, respect for diversity, etc. School turns into a tool for sustainable development, obeys and participates in it as a school community (Huckle, 2009). It combines different learning approaches that link principles and action escaping from the traditional form of education, such as “plane based education” and the holistic approach. The former goes beyond traditional educational contexts as it has a more practical character and seeks workable solutions to issues that combine the environment and society completing the holistic approach (Gough, 2005).

Sustainable Leadership

Sustainable leadership is a new approach to organizational leadership (Suriyankietkaew and Avery, 2016; Dalati et al., 2017; Al-Zawahreh et al., 2019). The concepts of sustainability and leadership have much in common and are both widely used in global scientific discourse as well as in everyday life (Fien, 2014). Sustainable leadership is a multidimensional theoretical framework, as it is holistic and incorporates many of the elements that make up leadership theories (Suriyankietkaew and Avery, 2016). Although there are characteristics of sustainable leadership that exist in other leadership approaches and overlapping practices such as employee engagement in a vision and democratic decision-making, it retains its own identity as a concept (Peterlin et al., 2015). Sustainable leadership focuses on the human factor, it considers the organization as a tool for offering to society, thus enhancing its effectiveness and increasing its survival prospects (Avery and Bergsteiner, 2013).

Sustainable leadership approaches, are aiming at the long-term resilience of the organism through practices and are characterized by time resistance, transformation ability and moral character, thus exceeding the limits of the three pillar model of sustainability (Suriyankietkaew and Avery, 2016). Sustainable leadership becomes part of the organization’s culture when leaders incorporate its practices into leadership development activities by staff (Bottomley, 2018). Organizational sustainability is not the responsibility of an individual or a manager working in a top-bottom hierarchical system, no matter how effective he is (Sanford et al., 2019), but is managed by a wide group of individuals (Çayak and Çetin, 2018). Hargreaves and Fink (2003) note that sustainable leadership concerns: (a) the maintenance of learning, (b) tackling social justice issues, (c) the rational use of natural and human resources, (d) the continuous effort and success, (e) the actions to preserve the environment, (f) the environmental diversity, and (g) the collective leadership. The organization’s values have an important role in sustainable leadership, so sustainable leaders must bring these values to life by using and transforming them along with the members of the organization in order to achieve its goals (Gerard et al., 2017). The interaction of individuals with each other, with the elements that compose the culture of the organization and with its internal and external environment has a decisive effect on it’s the efficiency and the way it distributes its resources (Avery and Bergsteiner, 2013). Fullan and Sharratt (2007) consider that organization’s path to sustainability is not linear but presents ups and downs. They believe that a sustainable organism accepts the obstacles to its development over time, but shows the ability to recharge. It is characterized by perseverance and confidence in its abilities and that it will eventually gain more than it will lose following the course it has set.

Sustainable Leadership in Education

The concept of sustainable leadership, in terms of education, is in its infancy (Lambert et al., 2016) because sustainability, as a concept, undergoes constant transformations. Davies (2007) argues that sustainable leadership aims at the success of all members of the school unit through the continuous and unremitting development and success of the school while Nartgün et al. (2020) in their research findings note that sustainable leadership is an important indicator for achieving school effectiveness. Hargreaves and Fink (2004) formulate seven principles for the school unit sustainable leadership. They state that learning should have a meaning that lasts and that engages students morally, spiritually and socially, creating veritably positive benefits for everyone, for the present and the future. The duration of success is ensured by the sustainable leadership when it has been developed and shared in groups and not individually. Thus, leadership succession does not refer to the outgoing head teacher but to the entire leadership team. Sustainable leadership benefits all students without exception and nourishes school resources without sacrificing them on the altar of success. It develops environmental diversity and is committed to environmental activism. The school as a whole is engaged in continuous improvement following human values and formulates six principles that compose the framework of sustainable leadership (Lambert et al., 2016). This framework stipulates that:

(i) Teachers must have the opportunity to develop management skills and best practices.

(ii) Teachers need to be encouraged to get involved in leadership-related activities.

(iii) Respect for the past, as a source of learning, is a prerequisite for improvement.

(iv) The installation of a learning climate is required, through multiculturalism and the creation of conditions of acceptance and coherence.

(v) The school’s orientation toward cooperation and joint actions with the external environment lead to the satisfaction of the needs of the community to which the school belongs.

(vi) Long-term goals should be combined with short-term goals in order to increase the efficiency of available resources.

Sustainable Leader’s Key Features

Sustainable leadership requires that the leader have the ability to think and be familiar with his/her personality and inner motivations. He/she will have to set up practices and traditions that will reflect the school’s culture and can be followed by his/her successors (Hargreaves and Fink, 2012). He/she applies his vision and ideas in collaboration with other members of the school community, a collaboration that will not be required but will be achieved through dialog. The sustainable leader works toward school adaptation into the changing external environment by sharing responsibilities, avoiding tensions and job exhaustion (Sink, 2009). Dalati et al. (2017) argues that sustainable leader is an ethical, visionary, reliable and fair team worker, who promotes communication and building relationships. He/she fosters school’s extroversion, the connection to its external environment and makes plans that lead to success as he/she has ingenuity and self-efficacy. School sustainability is organized internally but is directly influenced by external factors such as the central administration of education. Fullan and Sharratt (2007) suggest that sustainability in education creates the conditions for continuous improvement of students but it cannot be implemented if the school leaders and the central administration do not work in the same direction. They argue that school and central administration leaders’ cooperation is two-way, multidimensional and constantly under scrutiny while school’s sustainability subjects to indeterminate changes if the central line alter its direction. A sustainability-oriented organization consists of individuals or groups whose actions will promote sustainable development (Stavropoulos and Baginetas, 2015). They should follow strategic decision-making on issues related to strategic sustainability, product and program sustainability, staff sustainability and economic viability. Peterlin et al. (2015) believe that for an organization, the journey to sustainability goes through strategic leadership and strategic decision-making.

Strategic Leadership

The international educational literature for more than half a century is dominated by the question of the effectiveness of educational institutions and improving their results. Studies suggesting that student support, low negativity, trust, ethics, learning and respect are positive associated with the level of school performance (Lee and Louis, 2019; Paweenwat et al., 2019). These elements that are forming a compact school culture that will sustain and lead to school improvement, are intertwined with leadership and educational change (Taşçı and Titrek, 2019).

Strategic leadership is an important parameter for developing school as an organization and enhancing its effectiveness in all its dimensions. In the literature referring to school administration and leadership, especially after the 1970s, decentralization tendencies have emerged in the educational systems of many mainly developed countries. It is common practice to take short-term initiatives to improve school. Lately, growing interest has been noticed in the sustainability of these initiatives, with emphasis on the strategic dimension of leadership (Davies, 2007). Leaders tend to face short-term and urgent management obligations. They seek to organize the functioning of the school so that it can satisfy directly the expectations that exist for it from a number of diverse teams located within and outside the organization such as students, parents, state and local government control mechanisms as well as groups of pressure of local society (Papakonstantinou, 2008; Matsopoulos et al., 2018). The limited time of the head teacher transforms the strategy outline for future actions that will lead to the upgrading of the school organization in both the short and medium term into a secondary process. It would be ideal for both categories of action to be carried out by the manager-leader simultaneously to achieve effectiveness at the present time, ensure the continuity of good practices and enhance the development of the school as an organization.

Strategic leadership focuses on the actions of the leaders and the way that they lead. A series of actions are linked to strategic leadership such as decision-making, managing more than one activity at the same time, enhancing the abilities and capabilities of the organization, conjuring up a vision and communicating it, adopting a mindset and attitudes that both serve its aim and contribute to its advancement, the effective organization and functioning of the tasks as well as their preservation for as long as they fulfill the accomplishment of the goals set (Boal and Hooijberg, 2000). Strategic leadership also focuses on the people who are generally responsible for the organization, including not only a leader but a leading group responsible for the organization and its operation (Finkelstein et al., 2009). According to “upper echelons theory” this group is a small one and has a decisive impact on the organization’s results (Strand, 2014). It focuses on the traits of the individuals who have strategic leadership and are responsible for the course and direction of the organization (Mintzberg, 1979).

Personality and Skills of the Strategic Leader

In the literature there is a set of fundamental features that refer to both the organizational skills and the personality of a strategic leader. Strategic leaders have the organizational ability to explore their future choices, both in the medium and long term, in other words, they are strategically oriented (Davies and Davies, 2004). They understand the environment in which the organization operates. They evaluate the potential of the organization for transformation in conjunction with the changing trends of the environment and they create the necessary framework for strategic decisions to be translated into guidelines that are consistent, operational and applicable by the members of the organization by translating strategy into action (Davies and Davies, 2004). Strategic leaders are the change agent that, when implementing their decisions, will deal with interests and prejudices that have been established in the organization for a long time. They should overcome resistance to change stemming from structural inertia. A strategic leader aligns people and organization so that it consistently follows a particular philosophy creating a character that reflects the personal values and attitudes of the leader (Davies, 2007). Everybody is bound by a common system of values, which is substantially identical to that of the leader. Consequently, self-knowledge is necessary for the leaders in order to communicate their personal beliefs and be able to quickly recognize the upcoming change and evaluate it. Thus they will be able to decide whether to follow it by creating new strategic approaches to their goal. In this way, they determine the effective intervention points, that is the times or situations that signal the change of direction of the organization as new ideas and visions emerge (Davies and Davies, 2004). Leaders have absorptive capacity, i.e., they learn and absorb new knowledge critically and use it for the benefit of the organization, so as either to strengthen their action plan or to transform it in order to reach the goal (Cohen and Levinthal, 1990). The ability to exploit new knowledge is a crucial element for the introduction of innovative actions and is largely correlated with the organization’s pre-existing knowledge potential. It is also important for the head teacher to develop strategic capabilities, especially when the organization does not have significant material resources such as a public school. Collaboration and teamwork can help develop ways and techniques to solve problems and deal with challenges that appear for the first time or rarely. Using strategic thinking, they choose how to use existing resources (Theodore, 2014) in a way that is different from the one used or that is more effective, always in the context of the changing environment.

The leader’s personality influences the organization’s strategy decisively as it is reflected in his/her character and philosophy. An important aspect of the strategic leader’s personality is to have a vision. Like all organizations, school units have completed a period of existence during which they have acquired and incorporated a series of social, cultural and spiritual elements that have formed their character. The leaders envision the future of the school with respect to the past and the present so that their vision will be compatible with the philosophy of the organization. Boal and Bryson (1988) believe that a vision has both a cognitive and affective component. The former concerns the goals and means for their achievement and affects the pattern of work and the learning of new approaches. The latter focuses on the beliefs and values of the organization and its members that organize a reference framework for employee loyalty and mobilization (Shamir et al., 1994). The two components are jointly determinant for the sustainability of the actions required to realize leader’s vision. It is important that leaders can change their behavior according to the conditions prevailing in an organization. Hooijberg (1996) believes that behavioral complexity helps them adopting different leadership roles, and as a result, they are considered both by their subordinates and superiors to be more effective and able to inspire. Similarly, cognitive complexity and capacity give to the leaders the power to differentiate their behavior and their approach to the problems and issues that arise in the organization and which they are called upon to resolve. Complex cognitive people are effective in their collaborations as they are receptive to feedback and crisis management. They can make good use of a large amount of information and use existing resources for the benefit of their organization. Finally, the principal of a school unit comes into contact with a series of groups of people with different characteristics and different queries. Leaders must have communicative skills but also social intelligence in order to understand the feelings of others and differentiate them. Possession of skills such as empathy can enable the leaders to perceive personal aspects of people but also to interpret the social environment in which they operate. Leadership personality elements are key elements of effective sustainable leadership as they affect issues such as decision-making processes, organizational progress and its continuity that is feasible only when leaders inspire and persuade the rest of the staff to follow and serve their vision. The quality of school leader directly reflects on the quality of school as, according to Bush et al. (2018) it is the second most important school based factor which determines school outcomes. It also influences a number of school life factors such as teachers’ job satisfaction (Samancioglu et al., 2020). An effective leader is supportive to others, not only to the teachers but also to students in order to obtain the best outcomes (Berjaoui and Karami-Akkary, 2019).

The Character of the Greek Educational System

The Evolution of the Greek Educational System Toward Centralism

The Greek Educational System, as an official creation of the Greek state, coincides with the establishment of the Ministry of Education in 1833, whose responsibilities include its structure, its administration and its operation. Since its establishment has presented two main vulnerable points that affect it until our days. It was instituted on the basis of laws that copied the corresponding legislation of foreign states, but in which different social, economic and cultural conditions prevailed over those of Greece, and since its appearance to the present day it has been a field of political controversy and pursuit (Stamelos, 2007). The Greek Educational System originally had a different character from the present one. From 1833 to 1895 it was decentralized. The system of administration of education was complex and multi-faceted, following the character of the public administration. At the end of the 19th century, the central government gradually assumed the administration of education until the full weakening of the role of local society (Athanasoula-Reppa, 2008). The current form of the Greek educational system is due to a series of laws introduced during the reform of 1976 and thereafter. Liberis (2012) argues that decentralized movements began to appear in the 1980s as the views on participatory management, the reorganization of existing sectors, and the widening of autonomy with the main objective of the efficiency of the school increased. Law 1566/85 reflects these views as it established the creation of collective local bodies where individuals from local government were involved, mainly in school property management. At the same time, the vertical structure of the educational system was organized, which includes four distinct levels of responsibility (Saitis, 2014) making decisions at national, regional and local level (Liberis, 2012).

The Structure of the Greek Educational System

An administrative system in the form of a pyramid is formed which is a characteristic of centralized systems. The Ministry of Education is at the top level. At this level are a limited number of top managers, the executives of the political and staff leadership that are responsible for the development of educational policy. Moving to lower hierarchical levels, administrative responsibilities are reduced, resulting in the Director of the school, to be an executive tool with no essential responsibility (Andreou and Papakonstantinou, 1994). The middle level can be divided into two sub-levels, the regional sub-area of the Regional Education Directors and the hierarchically lowest level of prefecture, to which the Education Directors belong. Finally, at the lower level of the school unit, principals and vice principals are included. At each level of government, the degree of authority and responsibility varies to the opposite of its position (Saitis, 2014). Unlike power, the number of executives at each level is rising as we move toward the base and the work is severely fragmented. There is essentially a source of power, the top. The transmission of decisions is made with downward communication to the inferior levels that are simply recipients of the decisions of the central authority (Liberis, 2012), with little intervention and a negligible degree of power, while employees have little involvement in decision making as it is their duty to comply with the orders of the top (Iordanidis et al., 2010).

The Consequences of Centralism

The Greek educational system is characterized by clear hierarchical relations and formalism (Koutouzis, 2012). It is organized through an extensive framework of laws and regulations that interact with complex relationships minimizing the scopes of introducing innovation and effective administration. Centralization acts oppressively in the educational world (Andreou and Papakonstantinou, 1994) and in the school administration as they turn it into an executive body depriving it of creativity and removing the right to design the future of the school unit. Centralization does not take into account the social and economic conditions in the geographical area of the school (Kučerová et al., 2020). Centralization of education has been more widely used in previous decades mainly by countries characterized by low levels of human capital (Cappelli and Vasta, 2019). However, it cannot allocate material resources according to the actual needs of the school as it is characterized by uniformity in all areas, resulting in ineffective management and stagnation of school material capital (Andriani et al., 2019). This implies poor quality educational services as they are characterized by high complexity that is not served by standardization underlining the need for organizational and administrative decentralization (Villanueva and Cruz, 2019). The formalism created by centralization exerts negative pressure on a set of processes (Iordanidis et al., 2010) and any revision is likely to be treated as a threat to the existing balance and power, leaving zero scope for the head teacher to apply the principles of sustainable leadership. The intervention of the hierarchy is presented in a series of subjects that are components of the school life of the sustainable school.

The Selection System of School Head Teachers

The centralized and bureaucratic nature of the Greek educational system often leads to malfunctions (Bakas, 2007), which have a negative impact on the implementation of strategic leadership. The central administration decides on a number of issues related to curricula, books, equipment and the operation of schools. Among these issues, the choice of school unit head teacher is considered important. The choice of education staff is an administrative work that presents increased complexity and a high degree of difficulty, as the characteristics of a school principal can be a point of friction between different educational philosophies and systems.

Despite being inferior to the educational hierarchy, school principal is important to the educational process. He/she does not develop educational policy, but is the one with the closest proximity to the production of education, to pupils and generally to the microsystem of the school having a catalytic role in any expression of it. According to Rentifis (2016), leaders’ position is complex as they are appointed administrative officers but also they are educators who should shape their own internal policy.

The objective obstacles faced by the head teacher selection process are due to the difficulty of describing the work to be performed, the inability to safely assess the expected performance of the candidates in the administrative tasks and the subjective judgment of the evaluation committee as to their personality (Saitis, 2014). There is no single and objective way of assessing the moral, cultural and intellectual components of a personality, especially when they are not evaluated within the school workplace. At the same time, the influences that school receives as a multidimensional organization from its internal and external environment make it harder to predict the stability, autonomy and efficiency of the administration (Andreou and Papakonstantinou, 1994). Traditionally, seniority and experience were the main criteria for choosing head teachers. However, in recent years, enrichment has been attempted with formal qualifications such as scientific competence, relevant training, communication skills, views and vision (Mademlis, 2014). The basic prerequisite for participation in the selection process is the fact that candidates will have to be active teachers with at least 8 years of service in accordance with the criteria applied in the last selection procedure in 2017.

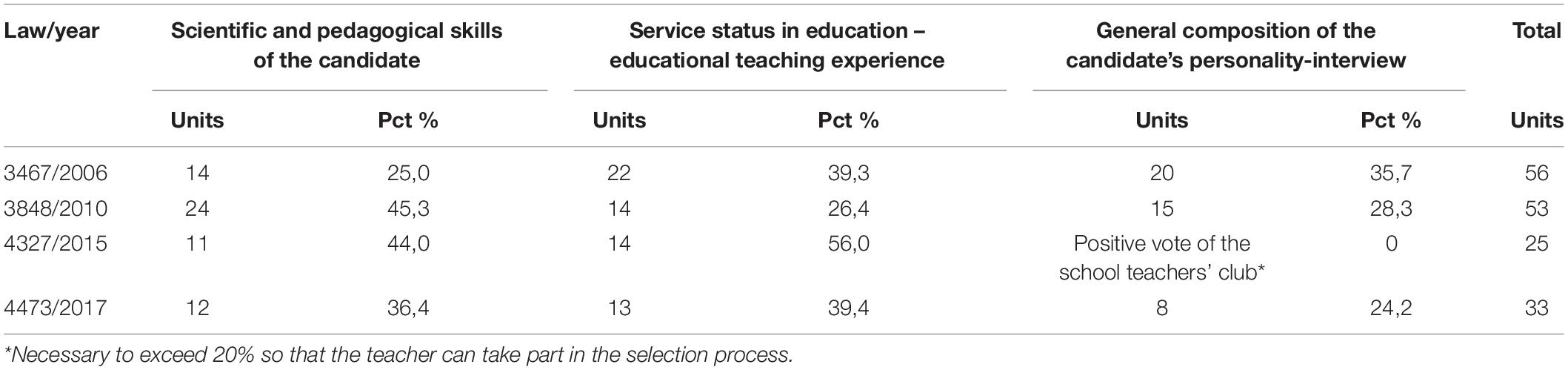

The way of choosing the staff of education is determined and shaped by the central administration through constant changes in selection criteria over the years. It is noteworthy that no school director’s selection process was repeated, which, according to Andreou and Papakonstantinou (1994), demonstrates the catalytic role of the state and its aspirations. Over the last 20 years, the selection has been made by different composition assessment committees and with different criteria, which were not characterized by institutional stability. This is interpreted by the desire of the political leadership to change the composition of executives applying education policy to effectively control administrative supervisory and guidance mechanisms (Papakonstantinou, 2012). Table 1 shows the changes in the weight of the general criteria, of the three general fields assessed during the last four school unit head teacher selection procedures. Noteworthy is the fact that these fields are taken into account over time with a different gravity, with the consequence that their reliability is considered low as it is time limited.

Continuous changes in criteria and their weight for the selection process are obviously a powerful obstacle to the leader’s ability to convey to the school community his/her vision of school, namely his/her thought to achieve a better future than the current situation. Strategic leaders have a vision to determine the direction of an organization, anticipate changes and lead it to growth. Through Strategic Thinking and Strategic Intent they attempt to influence the organization and engage early and long-term members of the school community in sustainable practices in the short term (Farver, 2013). Developing an organized structure by making continuous, small, distinct changes, attempts to upgrade its level without seeking to solve a visible problem directly. In order for the upgrading to be sustainable, time-based approaches that focus on changing the behavior and attitudes of the members of the organization are required (Avery and Bergsteiner, 2013). The selection of executives in public education is more difficult than in private. The creation of an employee hierarchy of specific, changing characteristics is a question of central authority. This leads to various legislative arrangements that theoretically aim at “meritocracy” and “upgrading” public education or other “informal” criteria (Kanellopoulos, 1995). It is characteristic that every change of law mentioned in the selection process coincided with the existence of different governments (Mademlis, 2014). Law changes often cause the discontinuation of actions that lead to the sustainability of change as the head teacher is likely to be forced to leave his/her position during the next selection process. One factor that magnifies the specific short-term problem of a principal in a school is the increased importance of the criterion of seniority as it gives a significant advantage to candidates who are usually close to their retirement while reducing the chances of selection to younger ones who possibly have specialized administration studies and higher qualifications.

The Educational Process

The sustainability of an organization like school depends not only on the econometric aspects of its operation but also on the quality of services it provides both in the cognitive and pedagogical fields. Historically, the main purpose of education is both to provide knowledge and to educate students according to human ideals. Nowadays, this holistic approach is more and more akin to the concept of sustainability, resulting in world-class education models such as education for sustainable development (ESD). Holistic and participatory character of ESD differs from the teaching model that has prevailed in Greece over the past 50 years. The formal school curriculum does not foresee the participation of sustainability as an autonomous teaching subject assigned to specific teacher competencies as is the case with existing subjects. The formal position of the administration of education is supportive, it does not detract from the importance of the subject, but for institutional reasons it does not introduce it into the curriculum. A series of factors that prevent the incorporation of new objects into school daily routines such as (i) pressures from educational interests; (ii) the separation of the academic directions for the school system in its own right; (iii) the pressures received by teachers from the central management and society to emphasize the so-called “basic” subjects such as composition, physics, and mathematics; (iv) the established subject matter of the lessons taught; and the lack of flexibility in teaching; (v) the policy and competition of “special interest” groups who wish to be represented in the school curriculum; (vi) the philosophy and policy of the educational institute or body that sets the educational policy in the adoption of innovations and the promotion of new knowledge (Powers, 2004). This has the consequence that the application of ESD is short, fragmented and discontinuous, making it incompatible with its objective purpose, which is the internalization of a viable behavioral model. It is based primarily on school or teacher’s initiatives, other than the curriculum guidelines or parallel to that (hidden curriculum) whenever possible (Gough, 2005).

The Standardization of the Educational Process

The school principals have a significant influence on the day-to-day life of the school (Adebiy et al., 2019) as they oversee the observance of guidelines derived from the technostructure to the teachers. However, they can not intervene in the curriculum or the syllabus as the state organizes the educational process through a stifling network of rules and instructions that standardize all the processes that concern it. The Greek educational system obeys organizationally to what Mintzberg (1979) mentions as machine bureaucracy as it has its basic characteristics that are standardization of work processes and technostructure. The last is one of the five basic characteristics of a modern organization. Strategic apex is the highest hierarchical level of the organization. They set their policy on the basis of the organization’s effectiveness in fulfilling its mission while serving the needs of those who control it, such as the state. The commands arrive at the operating core of the organization, which are the teachers who perform the basic tasks to produce a product downstream through the middle line of managers with official authority. Downstream information and control is facilitated by support staff that supports the process from a position outside the intermediate line. The technostructure has analysts serving the organization, influencing the work of teachers. They are distancing themselves from the flow of work and make plans to increase work efficiency. The technostructure translates the policy of strategic apex into rules on issues such as teaching timetable, curriculum, student assessment, teacher’s role, etc. In Greece, the role of the technical structure was taken over mainly by the Pedagogical Institute (Papakonstantinou, 2008) and later, by the Institute of Educational Policy, which by Law 3966/2011 constituted its successive structure. Pedagogical Institute was founded in 1964. It comes from the transformation and merger of older advisory bodies and provided opinions and suggestions in all courses of education. It operated as an independent public service. It was the oldest research and consulting body in the field of education and with its work it has significantly contributed to the design of educational policy by the Ministry of Education, carrying out pedagogical and educational work (Goupou, 2018). The school unit and the teachers are not involved in shaping the educational policy, so they are asked to implement it without having any opinion on any changes (Bakas, 2007), thus, they have no significant responsibility for the failure of educational system practices, resulting in the failure of substantive teacher evaluation (Matsopoulos et al., 2018).

The Quest for Innovation in a Context of Uniformity

According to Papakonstantinou (2008), the Greek education system seeks the highest standardization in order to achieve uniformity, that is to say the school to be the same for all pupils throughout the country. Thus, in theory, equal opportunities in education for students are achieved while at the same time teachers are provided with the ability to cope with all their tasks. Moreover, the absolute uniformity that is attempted gives the control mechanisms and the supporting structures the ability to easily and quickly detect any deviation from the standardized process. Such mechanisms that ensure the uniformity of the product of the educational process are the multiple and of specific characteristics exams that each student has to take in order to pass to the next educational level. Teachers understand the procedures by studying the rules and circulars, and in addition, they attend training and experiential seminars (Saiti, 2015; Pappas and Iordanidis, 2017). The system restricts the tendency for initiatives and innovation, and when these take place, they are part of the action defined by the hierarchy. Teachers, following the procedures as they are designed by the technostructure, are relieved of most of their responsibilities, thus operating in a security regime. They are not responsible for the failure of the system as the whole educational process and its objectives are prescribed. Consequently, their achievement to a satisfactory degree is assured. This, combined with the ambiguity that exists in the evaluation of the educational product, makes the assessment of the operational core unnecessary. The limits for deviations from the rules are minimal. The principal is required, as a first level of control, to ensure that the educational procedures provided by the Teaching Structure are followed. The requirement for strict adherence to timetables and subject matter to be taught is understood at the beginning of each academic year when the teaching instructions for each subject are sent to the school unit. These determine the chapters of each book to be taught, the teaching objectives to be attained, and the time in the teaching hours required for the teaching of each chapter. The sum of the teaching hours provided in the instructions for teaching a course coincide with the annual course hours available, creating a stiff time frame for the teacher. This leads to the frustration of teachers’ and school management’s ambitions for innovative object approaches or differentiations from the curriculum. The solution used as an alternative is the work of teachers, over the school hours, beyond their formal duties. Teachers receive a series of trainings that are organized by the technostructure with the main purpose of standardizing the way in which results are produced. They are given the impression they can take initiatives and implement innovative actions that are a small part of the curriculum (Papakonstantinou, 2012), but they actually carry out pre-defined and ex-approved actions that differ in the teaching method in relation to the usual instructional approach applied to the classroom. Teachers, through the Greek school’s tendency to respond to modern pedagogical developments, take action in the context of innovative environmental education, cultural programs, reading, health education, etc. the axes of which are determined by the central authority. Although these programs offered a different, more interesting, perspective in the educational process, they did not gain the appreciation of both teachers and students (Goupos, 2005). This is contributed by a series of negative elements that characterize the overall process, such as the realization of programs outside school hours. The busy student program, as well as the lack of incentives for teachers, is an obstacle to the implementation of the programs. At the same time, the fragmented way in which knowledge is offered, the absence of a link to the curriculum and the evaluation of the participants as well as the voluntary basis of actions reinforce the view that Sustainability Education is a less important process than that which takes place in school hours (Katsakiori et al., 2008). Finally, the lack of resources has an impact on the support of the educational process as it leads to fragmentary and untimely planning of teacher training programs and limited production of material that will help the educational process (Saiti, 2012).

School Unit Funding

The financial autonomy of the Greek school units is limited due to the provision of financial expenses by the central administration, thus reducing their efficiency, strengthening the bureaucracy and influencing their sustainability (Saitis, 2008; Saiti, 2012). At the same time, there is underfunding of the Greek education system, which is mainly the result of the deep recession in which the country, as well as the whole of Europe, has entered since 2010. During the years 2010–2012, in Greece there were reduction of more than 5% in educational expenditures (European Commission, 2015). This has resulted in the deterioration of the material and technical infrastructure of the school units. At the same time, the number of school units decreased by 2.8% (Avgitidou et al., 2016). Avgitidou et al. (2016) state that Greek teachers recognize as structural constraints the inadequacy of building infrastructure and the lack of daily necessities. In the same study, teachers acknowledge the increased professional stress created by educational policy (e.g., school mergers) as well as financial issues. In the latter we should emphasize the salary cuts that teachers suffered in three stages, at the beginning of 2010 by 12% (Law 3833/2010), in June of the same year by 8% with simultaneous abolition of allowances (Law 3845/2010) and in 2011 when there was a change in the salary classification and freeze on wage increases (Law 4024/2011). School funding is not only affected by the state’s economic policy but also by the way credits are distributed. Saiti (2012) notes the existence of two factors that slow the movement of credit to schools, jeopardizing the ability of a school to meet its needs which are the existence of a series of stages of approval of educational budgets and the weakness of the central administration to be aware of the special needs of each school unit. For this reason, the economic decentralization of education was attempted, but it did not substantially increase the financial autonomy of the school unit, as stated in a survey on the views of Greek teachers about the autonomy of the school unit (Lazaridou and Antoniou, 2017). Since 1989, by the joint Ministerial Decision Δ4/162/1989 (Ministries of Interior, Finance and Education), the property of the public school units has been transferred to the local self-government organizations (OTA). The school committee is the body responsible for managing the funds that will be allocated for the educational process (Saitis, 2011). The school committees have replaced by Law 1566/85 (article 52) the school financial services that operated since 1931 (Law 5019/1931). Their current operation obeys Law 1894/90 (article 5) while their formation is determined by a decision of the mayor of the city. The school principal is a member of the school committee (Law 2130/1993, article 11) as well as one representative of the parents’ association and at least three other members, depending on the number of schools belonging to the committee. Any citizen may be appointed by the mayor as a member of the committee. Understandably, the selection of school committee members does not follow meritocratic criteria, raising doubts about the committee’s ability to exercise effective management and social control (Saitis, 2011). Therefore, in Greece, which is characterized by “high” demand for education at all levels (Magoula and Psacharopoulos, 1999), the school principal and teachers of the school are bounded by the financial dependence of the school by factors that do not belong to its internal environment, thus influencing substantially the educational process (Lazaridou and Antoniou, 2017).

Staffing, Teacher Mobility, and School Climate

The head teacher’s effort to convey his/her vision as a strategic leader for the educational process is mainly addressed to teachers willing to work voluntarily. The role of head teacher in guiding the teaching staff is mainly limited to the formal control of compliance with the rules. The composition of the teaching staff is such that it does not allow it to be effective. School staffing is done through objective procedures (Law, 2525/1997) as the state has the obligation to allow those who wish and have the necessary qualifications to participate in the selection procedures without exclusions. However, according to Alexopoulos (2019), the selection process does not seem to be sufficient to ensure the staffing of public education with the appropriate human resources. It presents weaknesses such as the fact that it does not take into account the personality traits of the candidate teacher but only strictly objectively measured criteria (Rogari et al., 2015). This has led to criticism of the selection system. The conclusion that the Greek system is not suitable for the appointment of capable teachers has set its change as a priority (Darra et al., 2010; Rogari et al., 2015; Saiti, 2015). Creating an effective staff selection system as well as the calculation of the actual number of teachers needed to staff schools, will increase the effectiveness of the Greek education system (Saiti, 2012). Additionally, the staff selection, which is mainly made through tendering (Law 2525/1997, article 6), has been suspended for over 10 years. Many teachers are nearing or have reached the retirement age. A significant number of teachers do not have a permanent position at school and is alternated. A series of bureaucratic procedures that govern the movement and placement of the educational staff are based mainly on Laws 1566/1985 and 3848/2010 and Presidential Decrees No 50/1996, 100/1997 and 39/1998. The procedures begin at June and last for more than 4 months. The teachers’ mobility is an objective process that follows specific criteria such as service time, marital status, place of residence, co-service with spouse, postgraduate studies and serious health reasons of teachers, spouses, children, or parents. In order to be transferred, an educator must have served at the school for 12 months, or up to 3 years, if the school has been designated by the Ministry of Education as “difficult to be accessed” or if the school is the first placement of a newly appointed teacher (Saitis and Eliophotou-Menon, 2004; Darra et al., 2010; Saiti and Papadopoulos, 2015). The transfer of the teacher is decided by the competent department of the Ministry of Education under the necessary condition that there is a certified by the local educational administration, vacancy (Saiti, 2012). Thus many teachers will teach at school for less than one academic year and then drop out. The constant changes of the human resources of schools act as a deterrent to the creation of cohesive groups, negatively affecting the school climate and having a negative impact on teachers commitment to achieve school goals (Darra et al., 2010; Saiti, 2015). This circumstances not only undermine the principle of collegial unity in Greek public schools but also the ability of the head teacher to mentoring, coaching and inspire.

The leader has to deal with the bureaucracy pathology that Scott (1998) identifies on four issues: alienation, strict adherence to rules, lack of flexibility, and lack of sensitivity that negatively affect employees in an organization, especially if they are teachers. Strict adherence to the rules detracts from the pedagogical role of teachers, reduces job satisfaction, leading them to frustration and consequently loss of interest in decision-making which is a key component of strategic leadership and sustainability (Hirschhorn, 1997). This is the reality that Greek teachers are experiencing according to Sarikas (2017) where in a quantitative research he conducted, he found that teachers, in their working reality, do not experience the leadership behavior they would like by the head teacher and they are differentiated from it. Greek teachers see leadership as a factor in determining school climate and effectiveness (Stavropoulos and Xafakos, 2020). They believe that collaborative management is positively related to their commitment (Stavropoulos, 2018) and conflict resolution (Doxiariotis and Stavropoulos, 2019). Baginetas and Stavropoulos (2010), in a qualitative study they performed, found that head teachers believe that three of the principles of sustainable leadership, vision conduction, participatory management, and delegation cannot be applied to the Greek education system as they are hampered by factors such as the head teacher selection system, the lack of stable staff in the school unit and the reluctance of teachers to participate in decision-making.

Conclusion

This paper reached the conclusion that the structure of the Greek education system as well as its centralized character creates obstacles that hinder the implementation of sustainable leadership. In the reality of Greek educational units, the school principal is often called upon to implement an innovation designed or imposed by others. Rarely will the existing legal framework and the structure of educational administration give the school principal the opportunity to take innovative initiatives. Despite the efforts that have been made to decentralize education (Laws 1566/1985, 2043/1992, 2817/2000, 2986/2002), the reduction in the vertical dependence of schools on central administration was not accompanied by an integration of the school into the local community. The question of the school’s participation in the formation of the educational policy is done with fragmentary reports and opportunistic searches. It could be described as almost non-existent, mainly on the part of the educational society, which behaves either as if it does not concern her or as if she is satisfied by the relative decentralization achieved after 1985 (Papakonstantinou, 2012). The head teacher should communicate the instructions of the central administration to the teachers and jointly apply them (Law 1566/85, article 11). He/she is the one who should organize efficient group meetings in order to achieve the administrative objectives. At the same time, however, the sustainable leader must, within a collaborative climate, lead teachers to participate in decision-making and commitment to a common vision. This presupposes the creation of a cohesive group of teachers which will be able to work together and manage the tensions and conflicts in which pluralism leads (Saiti, 2015). This cohesive team is difficult to be formed in the current educational legal environment. A head teacher does not know whether he/she will remain as a head teacher or whether he/she will stay as the head teacher at the current school because the as principal selection procedures are each subject to a different law. None of the last four procedures for selecting head teachers followed the same selection criteria (Laws 3467/2006, 3848/2010, 4327/2015, 4473/2017). The next selection process was scheduled for June 2020, when the 3-year term of the current school principals expires. This selection process has been postponed indefinitely by Law 4692/2020 (article 52) without knowing the time that will take place and the selection criteria that will be followed. In addition, the other members of the school unit, the teachers, are transferred from school to school (Law 1824/1988, articles 5 and 7) or they are temporary detached (Law 1566/1985 articles 16 and 54) due to decisions taken at the ministry level (Saiti, 2009). Consequently, a cohesive team that can make long-range plans and work consistently to accomplish them thus bringing sustainable improvement to the school unit, cannot be formed. The absence of this group creates obstacles in the communication between the colleagues and consequently in the decision-making process, in the creation of a positive climate (Saitis and Saiti, 2018) but also in the integration of the newly recruited teachers. The last ones, since they do not have substantial training for their work at school, they rely on the supportive climate of the school they will serve and the guidance of the head teacher (Alexopoulos, 2019). Quality in education is also related to school funding. The limited availability of material resources requires their utilization with the greatest possible efficiency. Gradually, views have emerged that it is necessary to seek funding for the education beyond that of the state, even if it is more student-centered (Saiti, 2012). The so-called “free education” in Greece is a utopia, as Greek families fund forms of education that carry out parallel work with the public school in order to cover the inadequacy it presents (Magoula and Psacharopoulos, 1999). In any case, in a changing socio-economic environment the financial autonomy of Greek school may be sought as it cannot continue to be economically based on the same sources on which it has depended for the last 150 years.

The school is a cell in an educational system contributing to the production of the learning process. In order for this cell to be alive and viable, it should be able not only to perform its defined functions, but also to be able to receive and transmit messages, to remain stable, but also to be structurally and functionally differentiated when it is desirable from the environment. The nucleus of the cell is the strategic leader and his/her team, are the ones who will make the right quality decisions at the right time to transform the DNA of the school in order to maximize the benefits for the school community and local society more widely. The Greek educational environment is characterized by stability, which derives not from its effective functioning but from the complex, dense network of laws and the typist rule that follows it. Educational trends and innovations are slow to assimilate into such an established environment while their introduction is in such a way that they do not disturb the existing situation by following the unparalleled rule of uniformity. The sustainability of the Greek school in every sector has been taken over by the central authority by interpreting it in such a way as to turn it into a passive element. Conservation is a primary objective for the state, while less interest is brought by the change, adaptability and action that ensure sustainability in modern organizations. In the constantly changing global economic environment, fixed positions are changing. The status quo of the educational process ceases to exist as it undergoes changes in its pursuit of social, cultural, and technological development. The economic crisis of recent years has revealed the considerable possibility that the state may not be able to utterly guarantee the sustainability of educational institutions. It is therefore imperative for the Greek education system to be disconnected from the economic and organizational stereotypes of previous decades that are hindering its development and jeopardize its sustainability.

Recommendations and Suggestions for Future Research

Strategic leadership can transform an organization into a sustainable one through the commitment to sustainable practices. This requires a manager who is a leader, free from the legal burdens that prevent him/her from leading the school out of formalities, open up doors to society and turn into a tool that promotes sustainability. We consider necessary the creation of a mandatory training cycle for the candidate head teachers, on issues related to the management and sustainability of school units, analogous to those already in place for other subjects such as the use of computers. Additionally, we deem that the tenure of the school principal must last for at least 4 years. He/she will thus be able to communicate his/her vision and influence the culture of the organization. The criteria of the head teacher selection process are necessary not to be changing following the educational perceptions of each Minister of Education or Government but must follow the international educational developments. We also believe that in our digital age it is inappropriate for teachers to be placed and moved to schools through the convergence of regional councils. The staffing status of the country’s educational potential is fully electronic and updated on a monthly basis. Therefore, teacher mobility is a matter of timely scheduling; it should be automated and not dependent on repetitive meetings that impede the process. At the same time, there is a need for a gradual change in a range of practices followed by central administration on issues regarding flexibility in the use of material capital and educational credits as well as partial disconnection of the learning process from the central line. The yearly planning of the lessons, page by page of the school textbook can be replaced by assigning to the educators the teaching of specific thematic units, delegating them the obligation to determine the time planning and the educational approach that they deem appropriate. In this way educators will be transformed from a passive element into a fertile factor in the production of educational work. Thus, the state will oversee the educational process while allowing teachers to take part in promoting the innovation and connection of the school with the local community.

There are limitations to this paper since its content is not based on primary empirical data. Research analysis in educational aspects such as school funding, teacher mobility, the implementation of innovative action, collaborative school climate, the selection of head teachers is needed in order to ascertain the writers’ professional opinion and the conclusions that are stated. Although the researchers of education have dealt with numerous aspects that affect the everyday life in the Greek school, we know very little about the views of school principals on issues related to educational legislation and its points that they believe that are limiting factors for their work. Therefore, a broad quantitative study that would include the principals’ suggestions for practices that would facilitate their work and consequently the operation of the educational units could be a useful tool for the central administration in order to improve and upgrade the Greek school. Also, since the form of the educational process is a field of interest for the researchers of education, teachers’ opinion on the issues mentioned is of utmost importance, while at the same time significant attention should also be paid to the views of students and their parents in order to create a comprehensive tool for the development and evolution of educational policy.

Author Contributions

KK and JE have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Adebiy, D. O., Adebiyi, T. F., Daramola, A. O., and Seyi-Oderinde, D. R. (2019). The behaviours and roles of school principals in tackling security challenges in Nigeria: a context-responsive leadership perspective. J. Educ. Res. Rural Commun. Dev. 1, 74–88.

Alexopoulos, N. (2019). Resolving school staffing problems in greece: a strategic management approach. Front. Educ. 4:130. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00130

Al-Zawahreh, A., Khasawneh, S., and Al-Jaradat, M. (2019). Green management practices in higher education: the status of sustainable leadership. Tertiary Educ. Manage. 25, 53–63. doi: 10.1007/s11233-018-09014-9

Andreou, A., and Papakonstantinou, G. (1994). Power and Organization – Administration of the Educational System. Athens: Nea Synora-Livani. (in Greek).

Andriani, D. E., Clarke, S., and O’Donoghue, T. (2019). “7. Charting primary school leadership in Indonesia: from centralisation to decentralisation,” in New Directions In Research On Education Reconstruction In Challenging Circumstances, eds T. O’Donoghue and S. Clarke (Kingston, ON: Queen’s University Library), 101–121.

Asche, F., Garlock, T. M., Anderson, J. L., Bush, S. R., Smith, M. D., Anderson, C. M., et al. (2018). Three pillars of sustainability in fisheries. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115, 11221–11225.

Athanasoula-Reppa, A. (2008). Educational Management and Organizational Behavior. Athens: Hellin. (in Greek).

Audebrand, L. K. (2010). Sustainability in strategic management education: the quest for new root metaphors. Acad. Manage. Learn. Educ. 9, 413–428. doi: 10.5465/amle.9.3.zqr413

Avery, G., and Bergsteiner, H. (2013). “Sustainable leadership practices: enhancing business resilience and performance,” in Fresh Thoughts in Sustainable Leadership, eds G. Avery and B. Hughes (Melbourne, VIC: Tilde University Press), 3–17.

Avgitidou, S., Kominia, E., Lykomitrou, S., Alexiou, V., Androussou, A., Kakana, D., et al. (2016). Dealing with the effects of the crisis on education: views and practices of principals and principals in primary education. Res. Educ. 5, 172–185. doi: 10.12681/hjre.10784

Baginetas, K., and Stavropoulos, V. (2010). “Understanding the meaning and principles of sustainable leadership in education. A case study of principals serving in formal and non formal education school settings,” in Proceedings of the 4th Panhellenic Symposium “The Sustainable School of the Present and the Future”, Athens, 11–27.

Bakas, T. (2007). “The regional administration of education. Weaknesses-deficiencies-prospects,” in Proceedings of the Conference Primary Education and the Challenges of Our Time, Organization and Administration of the Educational System, Ioannina, 49–54. in Greek.

Berjaoui, R. R., and Karami-Akkary, R. (2019). Distributed leadership as a path to organizational commitment: the case of a Lebanese school. Leadersh. Policy Sch. 1–15. doi: 10.1080/15700763.2019.1637900

Blewitt, J. (2017). “12 Leadership for sustainable development education,” in Professional Development and Institutional Needs, eds G. Trorey and C. Cullingford (Milton Park: Taylor & Francis), 207. doi: 10.4324/9781315245966-12

Boal, K. B., and Bryson, J. M. (1988). “Charismatic leadership: a phenomenological and structural approach,” in International Leadership Symposia Series. Emerging Leadership Vistas, eds J. G. Hunt, B. R. Baliga, H. P. Dachler, and C. A. Schriesheim (Lexington, MA: Lexington Books), 11–28.

Boal, K. B., and Hooijberg, R. (2000). Strategic leadership research: moving on. Leadersh. Q. 11, 515–549. doi: 10.1016/S1048-9843(00)00057-6

Bottomley, K. S. (2018). “Developing sustainable leadership through succession planning,” in Succession Planning, eds P. Gordon and J. Overbey (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan), 1–10. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-72532-1_1

Bush, T., Hamid, S. A., Ng, A., and Kaparou, M. (2018). School leadership theories and the Malaysia education blueprint. Int. J. Educ. Manage. 32, 1245–1265. doi: 10.1108/IJEM-06-2017-0158

Cappelli, G., and Vasta, M. (2019). Can school centralization foster human capital accumulation? A quasi−experiment from early twentieth−century Italy. Econ. Hist. Rev. 73, 159–184. doi: 10.1111/ehr.12877

Çayak, S., and Çetin, M. (2018). Sürdürülebilir liderlik ölçeği: geçerlik ve güvenirlik çalışması. [Sustainable leadership scale: validity and reliability study]. Electron. Turk. Stud. 13, 1561–1582. doi: 10.7827/TurkishStudies.13703

Christofi, M., Leonidou, E., and Vrontis, D. (2015). Cause-related marketing, product innovation and extraordinary sustainable leadership: the root towards sustainability. Glob. Bus. Econ. Rev. 17, 93–111. doi: 10.1504/GBER.2015.066533

Clark, A. J. (2017). Sustainable school improvement: suburban elementary principals’ capacity building. J. Leadersh. Instruct. 16, 5–8.

Cohen, W. M., and Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive capacity: a new perspective on learning and innovation. Adm. Sci. Q. 35, 128–152.

Dalati, S., Raudeliu¯nienė, J., and Davidavičienė, V. (2017). Sustainable leadership, organizational trust on job satisfaction: empirical evidence from higher education institutions in Syria. Bus. Manage. Educ. 15, 14–27. doi: 10.3846/bme.2017.360

Darra, M., Ifanti, A., Prokopiadou, G., and Saitis, C. (2010). Basic skills, staffing of school units and training of educators. Nea Paideia 134, 44–68. in Greek,Google Scholar

Davies, B. (2007). Developing sustainable leadership. Manage. Educ. 21, 4–9. doi: 10.1177/0892020607079984

Davies, B. J., and Davies, B. (2004). Strategic leadership. Sch. Leadersh. Manage. 24, 29–38. doi: 10.1080/1363243042000172804

Dempsey, N., Bramley, G., Power, S., and Brown, C. (2011). The social dimension of sustainable development: defining urban social sustainability. Sustain. Dev. 19, 289–300. doi: 10.1002/sd.417

Doxiariotis, G., and Stavropoulos, V. (2019). “Investigating the relationship between the leader’s leadership behavior and the commitment of teachers to the school they serve, with the selected conflict management strategies: study in secondary education teachers,” in Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on the Promotion of Educational Innovation, Vol. 2, Larissa. 329–336.

Dyer, G., and Dyer, M. (2017). Strategic leadership for sustainability by higher education: the American College & University Presidents’ climate commitment. J. Clean. Prod. 140, 111–116. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.08.077

European Commission (2015). Education and Training Monitor 2015. Country Analysis. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Farver, S. (2013). Mainstreaming Corporate Sustainability: Using Proven Tools to Promote Business Success. Evesham: GreenFix.

Fien, J. (2014). “From locust to honey bee: towards leadership philosophies for sustainability,” in Intergenerational Learning and Transformative Leadership for Sustainable Futures, eds P. B. Corcoran, B. P. Hollingshead, H. Lotz-Sisitka, A. E. J. Wals, and J. P. Weakland (Wageningen: Wageningen Academic Publishers), 33–48.

Finkelstein, S., Hambrick, D., and Cannella, A. (2009). Strategic Leadership: Theory and Research on Executives, top Management Teams, and Boards. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fullan, M., and Sharratt, L. (2007). “Sustaining leadership in complex times: an individual and system solution,” in Developing Sustainable Leadership, ed. B. Davies (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE), 116–136. doi: 10.4135/9781446214015.n7

Gerard, L., McMillan, J., and D’Annunzio-Green, N. (2017). Conceptualising sustainable leadership. Ind. Commer. Train. 49, 116–126. doi: 10.1108/ICT-12-2016-0079

Goodland, R. (1995). The concept of environmental sustainability. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 26, 1–24. doi: 10.1146/annurev.es.26.110195.000245

Gough, A. (2005). Sustainable schools: renovating educational processes. Appl. Environ. Educ. Commun. 4, 339–351. doi: 10.1080/15330150500302205

Goupos, T. (2005). “Types of environmental education programs developed by primary and secondary education teachers,” in Proceedings of the 1st Conference of Environmental Education Programs, (Lesbos: University of the Aegean). in Greek.

Goupou, D. (2018). The Pedagogical Institute From its Foundation to its Abolition: A Theoretical and Empirical Investigation. Athens: Kyriakidis publications. in Greek.

Hansmann, R., Mieg, H. A., and Frischknecht, P. (2012). Principal sustainability components: empirical analysis of synergies between the three pillars of sustainability. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 19, 451–459. doi: 10.1080/13504509.2012.696220

Hargreaves, A., and Fink, D. (2004). The seven principles of sustainable leadership. Educ. Leadersh. 61, 8–13.

Hargreaves, A., and Fink, D. (2012). Sustainable Leadership, Vol. 6. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Hirschhorn, L. (1997). Reworking Authority. Leading and Following in the Post-Modern Organization. London: MIT Press.

Hooijberg, R. (1996). A multidirectional approach toward leadership: an extension of the concept of behavioral complexity. Hum. Relat. 49, 917–946. doi: 10.1177/001872679604900703

Huckle, J. (2009). Sustainable schools: responding to new challenges and opportunities. Geography 94, 13–21.

Iordanidis, G., Tsakiridou, E., and Parfesta, S. (2010). Bureaucratic structures in elementary school as a factor in promoting or inhibiting the work of teachers and their function. Soc. Sci. Tribune 15, 235–258.

Kaparou, M., and Bush, T. (2015). Instructional leadership in centralised systems: evidence from Greek high-performing secondary schools. School Leadersh. Manag. 35, 321–345. doi: 10.1080/13632434.2015.1041489

Katsakiori, M., Flogaiti, E., and Papadimitriou, B. (2008). Education in Greece Today – Environmental Education Centers. Thessaloniki: Wetland Center, 148. in Greek.

Koutouzis, M. (2012). Management – Leadership – Efficiency: Seeking Scope in the Greek Educational System. Modern Issues of Educational Policy. Athens: Epikentro, 211–225. in Greek.