- School of Education, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen, United Kingdom

This case study explores how pupils might address the issues of bullying and friendships during primary-secondary transition through drama conventions. The research was implemented on the west coast of Scotland during the final four weeks of primary education in three associated primary seven classes. Research methods included pupil questionnaires (primary and secondary school), teacher observations, researcher’s diary, semi-structured interviews (teachers) and a focus group (pupils). The data suggest that some pupils conceptualized their primary-secondary transition as ‘moving up’. However, as the drama developed pupils recognized the multiple and multi-dimensional aspects of their transition. In addition, pupil and teachers indicated that when pupils engage with a drama transition curriculum, it supports the promotion of friendships while diminishes fears and provides strategies for those who might encounter bullying.

Conceptualization of Primary-Secondary Transition

Globally, school aged children and young people encounter transitions throughout their schooling and lives. As such, transitions are an ongoing and dynamic psychological process requiring multiple social and educational adaptations over time, due to changes in context, relationships and identity which require ongoing support (Jindal-Snape, 2018). Educational transitions often consist of a normative transfer from primary (or its equivalent) to secondary school and happens, for most people, at the same time in their lifespan (Symonds, 2015). For example, primary-secondary transition coincides with the pre-adolescence or adolescence stage (10–14 years old), with pupils experiencing both physiological and psychological changes, marking the end of their physical childhood and commencement of adolescence (Ng-Knight et al., 2016). Therefore, some might conceptualize transitions as a status passage with pupils changing schools to become a different type of pupil (e.g., a ‘secondary pupil’). This change in status is sometimes termed the ‘Big Fish Little Pond Effect (BFLPE)’, where pupils were once the biggest in primary and then become the smallest in secondary, and suggests that transition is focused on the movement between schools (Seaton et al., 2009). However, according to Multiple and Multi-dimensional Transitions (MMT) theory, individuals can experience multiple transitions, in several domains (e.g., social and academic) and contexts (e.g., school and home) at the same time. In turn, each transition can impact and interact with others, resulting in multiple and multi-dimensional transitions (e.g., one parent gets a new job, in a different location, which causes the family to relocate house and school) (Jindal-Snape, 2016). Therefore, transitions are complex, non-linear, ever evolving and require a holistic understanding (Jindal-Snape, 2016). Few primary-secondary studies outline pupil conceptualization of transitions (Jindal-Snape et al., 2020).

Primary-Secondary Transition - A Theoretical Perspective

International literature suggests that primary-secondary transitions can be a satisfying, fulfilling and successful process for many pupils (Galton, 2010). Indeed, many pupils look forward to experiencing larger and better equipped facilities, and having increased responsibility (Scottish Executive, 2007). An example of increased responsibility, for secondary pupils, might include navigating and understanding their individual timetables, managing subject equipment and traversing to multiple classrooms (Symonds, 2009). As a result of, and due to the specialist subject nature of secondary education, pupils often experience multiple teaching styles with the potential for increased pedagogical challenge and depth (Robinson and Fielding, 2007). However, some pupils might experience negative and mixed feelings toward primary-secondary transition (Jindal-Snape and Miller, 2008). For example, pupils moving from the generally smaller and more familiar primary environment, to that of the larger and unfamiliar secondary, can result in them missing their primary teacher (City of Birmingham Education Department, 1975). Additionally, pupils might develop anxieties about getting lost as they navigate and adapt to the larger school building (Caulfield et al., 2005). Pupil navigation of their new school terrain requires adjustment to longer school days, timetabling (Hallinan and Hallinan, 1992), new subjects, multiple teaching styles and pedagogical approaches (Robinson and Fielding, 2007). Consequently, pupils might be concerned about increased academic pressure, workload and becoming overwhelmed (Karagiannopoulou, 1999).

Alongside pupils’ workload concerns, they might become anxious about maintaining/establishing peer friendships (Weller, 2007). Peer friendships can be important due to pupils hearing negative transition myths passed down across the generations. These myths include having one’s head flushed down the toilet, being bullied by older pupils (Symonds, 2009) and encountering humiliating experiences (Delamont, 1991). All of which can culminate in attainment dips (Alexander, 2010). Consequently, pupils might experience increased stress levels during (and due to) their primary-secondary transition which, for some, could be described as traumatic (Jindal-Snape and Miller, 2008). However, initial transition anxiety often subsides once pupils settle into their new school (Rice et al., 2011). Waters et al. (2014) suggests that pupils’ who have a positive transition attitude are likely to have successful transitions.

Transitions can be multiple and simultaneous which might result in people feeling that they have little autonomy. Self-determination theory suggests that individuals have three innate psychological needs: competence (one feels capable and effective), autonomy (one’s control of their actions) and relatedness (the development and creation of close personal relationships). It is how these needs are satisfied which helps to support one’s motivation and well-being (Ryan and Deci, 2000). For example, relationships can be in flux during primary-secondary transitions due to leaving established friendships while also having to make new ones. In addition, pupils might question their competence to maneuver the changes to their new secondary context and relationships while feeling that their voice isn’t being heard. Jindal-Snape (2012) suggests that educators should find meaningful opportunities for pupil voice in transitions e.g., creative approaches like drama (Jindal-Snape, 2016).

To support successful primary-secondary transition in Scotland, The Scottish Government commissioned a systematic literature review, authored by Jindal-Snape et al. (2019). The review reported a decline in education outcomes upon entering secondary school, with dips in pupil motivation and school engagement and increased levels of absence/school dropout. Moreover, it highlighted that transitions can negatively impact pupils’ sense of school belonging and their social, emotional and mental health with higher levels of anxiety and depression. Although the review indicates that the literature mainly focuses on negative aspects, it also suggests that pupils can experience mixed and positive emotions surrounding transitions. The review made nine recommendations to support successful school transitions by developing a sense of belonging in primary before moving to secondary school through peer networks and buddy schemes; this should be extended into secondary. Pupils should develop secure attachments with peers and secondary school staff via activities in the new school and residential experience(s). Primary and secondary staff should have an ongoing dialog regarding the pedagogical approaches between sectors, with staff collaborating and learning alongside one another. Pedagogically, pupils should experience a problem based pedagogy which focusses on emotional and social skill development. There should be a national level policy overview on curricular structures and the creation of resources required to facilitate successful transitions. Finally, equal partnership with parents in transition planning and preparation and tailored transition supports for pupils with additional support needs should be implemented.

Identity and Friendships During Primary-Secondary Transition

Some international transition researchers might view primary-secondary transition as a status passage, where individuals change into new social roles and identities that could be more responsible, mature or demanding (Glaser and Strauss, 1971). These new roles and identities are shaped through pupils’ interactions with their peers; friendships are a concern during the transition process (Galton, 2010). Friends and peers, who are also experiencing the transition process together, become mechanisms of support by offering advice (including emotional support) to one another (Bokhorst et al., 2010). For example, during the transition process, pupils evaluate friendships based on shared interests (Symonds, 2009). In doing so, they might initially use previous friendships as support mechanisms and discard them in favor of new ones (Lucey and Reay, 2000). Once in a new friendship, pupils are introduced to likeminded individuals and thus a ‘snowball effect’ ensues which increases their social capital (Weller, 2007).

Bullying During Primary-Secondary Transition

Bullying is a universal phenomenon (Joronen et al., 2012). It is defined as intentional and repetitive negative behaviors aimed at individuals or groups who cannot defend themselves (Olweus, 2013). Bullying tends to peak during late childhood and early adolescence which often coincides with primary-secondary transition (Cross et al., 2018). Notwithstanding the biological changes that pupils often experience around this time, and the increase status of peer relationships (Pellegrini and Long, 2002), school transition itself appears to independently add to an increase in bullying (Rigby, 1996).

Being bullied in secondary school is a fear for many causing stress and anxiety (Symonds, 2015). A Scottish study by Zeedyk et al. (2003) indicates that although most secondary pupils reported school to be better than expected, concerns about being bullied were more prevalent than in a comparison group of primary pupils. Focusing on bullying post transfer to middle school in the United States of America (USA), Nansel et al. (2007) indicate that more than half of sixth graders stated that they were involved in bullying and victimization during the middle-school transition. In addition, they found that pupils who were classed as bullies, or bully victims during sixth grade displayed poorer school adjustments over their non-involved peers (Nansel et al., 2007). Furthermore, bullying and victimization continued over time, with more than half of pupils who were involved in bullying and/or victimization in sixth grade also reporting continued involvement in seventh grade. As a result, the study suggests that involvement in bullying others or being a victim of bullying may be a risk factor for poorer adjustment in the transfer school (Nansel et al., 2007). Similarly, a USA study by Farmer et al. investigating the continuity and change in pupils’ involvement in bullying across the transition from primary to middle school, found that pupils who have increased levels of externalizing and internalizing problems in primary are at greater risk of being involved in bullying behaviors (either as a bully or a victim) in their next school (Farmer et al., 2015). Pellegrini and Long (2002) USA study suggests that post transition alters group dynamics and promotes bullying in males (by threatening other males with physical violence – they tend not to target females) and in females (by verbally taunting other females). Generally, incidents of bullying and aggression tended to increase with the transition to middle school and subsequently decline. This might be due to using bullying acts to manage peer dominance and relationships in social groupings during transitions (Pellegrini and Long, 2002).

Cross et al. (2018) three year Australian study of 3,462 pupils (mean age 13) sought to reduce bullying by encouraging its non-acceptance, increase bully victims supports from staff and peers, improve empathy and social competence, increased friendships and school connectedness, and reduce negative behaviors, absenteeism and loneliness. They indicate that bullying incidents reduced the year following the pupils’ transition to secondary school and suggest that pupils’ knowledge of peer support networks lowered bullying anxiety as well as increasing school connectedness and pro-victim attitudes (Cross et al., 2018). Cross et al. (2018), suggest that primary-secondary transition is a time where pupils require additional support to reduce bullying. They recommend the end of primary and the beginning of secondary as a suitable time to support pupils in their non-acceptance of bullying (Cross et al., 2018).

Creative Education and Transition Research

Creative pedagogies support successful transition as they develop pupils’ self-esteem, agency and voice (Jindal-Snape, 2012). Furthermore, using creative approaches increases levels of confidence, imagination and ability to face challenge, resilience motivation, engagement and health and wellbeing (irrespective of age) (Bancroft et al., 2008; Toma et al., 2014). Despite the literature supporting the use of creative pedagogies during primary-secondary transition, Symonds (2015: 14) suggests that pupils might view play-based approaches as ‘childish behaviors from primary’ which they require to surpass. However, by stopping playing, pupils might negate the potential benefits of play (Whitebread and Basilio, 2013). Vygotsky (1974) argues that play was central to children’s communication, meaning making and self-regulation. In addition, Bruner (1986) suggests that play, which is voluntary, self-initiated and focused on the process, develops pupils’ problem-solving skills relevant to their interests. Therefore, pupils (and secondary teachers - see Symonds, 2015) might limit opportunities for a meaningful and play-centered transition pedagogy due to negative internal and external perspectives on playing.

Play, Playfulness and Drama

Play, a forerunner to drama, requires pupils to accept and create a fictional world through a sense of ‘playfulness’ (Winston, 2004). Playfulness is a form of social interaction which empowers pupils to symbolically transform objects and actions into new meanings (Neelands and Goode, 2015). Consequently, pupils manipulate language, objects and space to establish new realities giving voice to issues which might have previously been voiceless (Neelands, 2012). Thus, pupils’ playfulness is shaped by their individual and collective understanding of the cultural environments. It is from a child’s innate capacity for play, and the knowledge they develop from their participation in and on the play, that dramatic activity is created (Winston and Tandy, 2009). For example, as play develops it becomes structured by the dramatic form (either through devising or scripted activities) while still maintaining its playfulness. However, there should be a balance between mindfulness (the ability to be metacognitive of the drama work by taking the human content and context seriously) and playfulness during the creation of the drama activity. Resultantly, pupils must be cognizant as to how the drama experience might change people and the world which they share and shape (Neelands, 2012).

Drama

Drama is a socially constructed medium which empowers participants to explore and problem-solve issues central to the human condition. Working collectively in the drama framework, participants enter ‘as if’ scenarios which require emotional, cognitive and physical responses. Participants use their real-world knowledge to influence the fictional narrative by rehearsing alternative possibilities through role-play (Neelands and Goode, 2015).

Role playing requires pupils to adopt the attitudes and beliefs of a role and develop their understanding of another person’s stance (Özbek, 2014). Although role players do not require the skills of an actor, they nevertheless draw upon human experience and the skills of living itself. Vygotsky’s construct of perezhivanie (Vygotsky, 1994) (which is interpreted as ‘lived experience’ or ‘emotional lived experience’) is useful in drama education as the learning focuses on human experience and emotions. When in role, pupils cultivate the ‘lived emotional experience’ through dramatic action by interpreting the actions (and reactions) of their role in relation to those around them, and, by default, provides the opportunity to alter their behaviors in action (Davis and Dolan, 2016). Therefore, using the lived experience of the role and the environmental situation of the drama (perezhivanie) empowers participants to broaden their experience and make new understandings through the dramatic form (Heathcote, 1984).

One approach to support the creation of new understanding, through the dramatic form, is via Drama Conventions (Neelands and Goode, 2015). Drama Conventions are focusing structures or forms which suspend the usual relationships of people, place and time. Such structures develop dramatic form and content by enabling pupils to scrutinize, analyze and understand human behavior and actions in the ‘here and now.’ Even though the drama may be set in the future, the action is unfolding in the metaphorical present (Neelands and Goode, 2015). The resulting metaphorical present echoes meanings from the actual present which creates a felt knowledge (Clark et al., 1997) and universal understanding (McGregor et al., 1977).

Universal understanding does not mean universality of agreement, as participants might interpret metaphors and symbols differently. Bolton (1986) explains this through the construct of the dramatic metaphor with its meaning created in the dialectic setup between the actual and fictional context. Dramatic metaphor requires participants to operate on two levels of emotion. The first level refers to emotions drawn from the fiction which represents those in the real world, and the second, which does not require the expression of real first-order emotions, focuses on the ambivalence of being sad, yet not sad, happy, yet not happy, angry, yet not angry (Bolton, 1986). Vygotsky (1974: 548) labeled this as the ‘dual affect’ explaining, ‘the child weeps in play as a patient, but revels as a player.’ The dual affect is like Boal (1995) ‘metaxis’; ‘the state of belonging completely and simultaneously to two different, autonomous worlds; the image of reality and the reality of the image’ (43). Carroll (1988): (13) offers a further elaboration of metaxis as, ‘a mental attitude, a way of holding two worlds in mind, the role and the dramatic form, simultaneously in the drama frame.’ Framing is used to show the multiple possibilities and perspectives for role interpretation and event relationship. Therefore, dual affect, metaxis and dramatic metaphor provides a fictional safety-net for participants to understand and rehearse possible futures without ever accruing the consequences of those actions in the real world (Goode, 2014).

Safety in Drama

Although, the emotions experienced by pupils through role play are a result of the life conditions explored in the drama, some educators, in the Anglo-American cultural tradition, might refrain from engaging in strong emotions in teaching, and in doing so miss important learning opportunities (Nimmo, 1998). For example, some educators might be concerned about pupil protection and safety when adopting roles that are close to themselves. This is understandable as when pupils engage in socially constructed learning activities, they come into conflict with their preconceptions, which can cause some anxiety and confusion (Heyward, 2010). Thus, when pupils challenge one another’s ideas they undertake a process of cognitive conflict which is central to Piaget’s theories of cognitive development (Hamilton and Ghatala, 1994). In turn, pupils’ interactions supports their understanding of multiple perspectives, which is conducive to cognitive development, as they attempt to understand the emotional confusion and disturbance engendered by differing views (New, 1998). Reflecting on multiple perspectives enables pupils to challenge dominant stances (Alton-Lee, 2003), which can lead to change and new understanding (Landy and Montgomery, 2012). Therefore, protection should not solely focus on protecting pupils from the emotion, as without emotion engagement there might be limits to the learning potential, and instead centre on protecting learners into the emotion. Consequently, educators should structure drama work to ensure that any risks are perceived rather than actual (Bolton, 1984).

To support creative and structured risk-taking educators should offer source materials that are rooted in human experience. This enables pupils to connect with the source and locate it in either their personal or collective experience. Therefore, it is important that initial bullying discussions are dealt with sensitively and at a slow pace. Pupils should be offered the opportunity to step out of the discussions (and subsequent drama activity) if they do not feel ready to discuss these emotions (Fisher and Smith, 2010). Indeed, it is the teacher’s responsibility to establish the drama and support pupil ongoing engagement with the creation of the fiction (O’Neill, 1995). When the teacher works in role, pupils feel protected within the fiction as they help to create the drama while scaffolding the learning experience (Heathcote and Bolton, 1994) and establishing its rules within it (O’Neill, 1995). Central to these rules is the concept that participants acknowledge that the drama is being lived at life rate in an agreed place, time and circumstance through multiple roles (Wagner, 1976). This means that the roles become more recognizable to the pupils and a relationship begins to form between the drama and the real world (Neelands and Goode, 2015). However, although the drama is being run at life rate, this does not mean that pupils are consistently in role. Indeed, it is important that pupils are given the opportunity to reflect in and on the action throughout the drama experience (Neelands and Goode, 2015). Consequently, there requires to be a clear divide between the drama and real world by ensuring that pupils’ de-role and de-brief (O’Toole and Dunn, 2002). For example, if a pupil feels that they are blurring the boundaries between the role and reality, they might wish to assume a spectator function outside of the drama world, thus assuming various levels of commitment within the drama activity (Heyward, 2010).

Drama, Bullying and Pupil Connectedness

An overarching aspect of drama is to support pupils in their ability to make sense of the world and to effect behavioral change (Bolton and Heathcote, 1998). This is because drama provides pupils with the distance to see themselves as others do while enabling them to experience ‘reality’ from multiple perspectives (Bagshaw and Lepp, 2005). As such, drama empowers pupils to explore issues relevant to their lives and investigate how their autonomy and interconnectedness creates positive changes for society (Neelands, 2009).

A relevant issue which globally impacts pupils is school bullying. To counter the impact of bullying, schools might traditionally discuss the topic. However, pupils prefer to use drama (in comparison to other pedagogical approaches) to investigate these issues (Crothers et al., 2005). Johnson (2001) argues that drama provides pupils with a safe fictional context to create conflict themed scenarios to explore, reflect upon and develop their understanding of bullying. Therefore, learning within and reflecting on the fiction enables pupils to process their thoughts and emotions while creating solutions for bullying. This is achieved when pupils listen to and share their anxieties, and make connections to others’ experiences/opinions, without directly engaging in negative behaviors themselves (Johnson, 2001).

Goodwin et al. (2019) Irish study required pupils to watch a one-act scripted performance, which highlighted the roles of the bullying bystanders, focusing on a bullying incident in the school playground. Pupils, aged between 12–15 years, then conceptualize their understanding of bullying and participated in drama workshops to generate bullying prevention strategies for their school. Data indicates that the drama intervention enabled pupils to explore their understanding of the topic of bullying in a non-threatening and sensitive manner. Moreover, the researchers suggest that drama bullying prevention strategies should be facilitated with multiple year groups (not just one particular year set), and that schools should incorporate pupils’ solutions for bullying in their anti-bullying policies (Goodwin et al., 2019).

Joronen et al. (2012) Finish study implemented a drama program using control and intervention groups with 190 primary school pupils. The study aimed to enhance social relationships and minimize school bullying using drama sessions, follow-up activities at home and three parents’ evenings focusing on social well-being issues. Questionnaire data was obtained pre and post intervention and resulted in improvement in social relationships and a decrease in the number of bully victims (Joronen et al., 2012). Drama was also used in Graves et al. (2007) USA study to build social skills, self-control, understanding of emotions and conflict resolution. This study was implemented over 12 weeks with 2, 440 students in public middle and high schools (Graves et al., 2007). Pupils displayed a decrease in their relational physical aggression levels and increased their knowledge and strategies to deal with bullying (Graves et al., 2007). This is like Beale and Scott (2001) findings where they sought to understand the causes of bullying through drama and noted a decrease in aggressive incidents post drama intervention. The researchers indicate that this might be due to drama’s ability to develop positive social relationships between peers, while also enabling them to generate effective ways of dealing with bullying behaviors (Beale and Scott, 2001).

Burton (2015) international study ‘Acting Against Bullying’, used drama techniques to regress bullying in associated primary and secondary schools. A key aspect to Burton (2015) study was the adaptation of Boal’s (1995) Forum Theatre (FT). FT involves either a predetermined scenario or one that is developed with the participants. In both approaches, the actions of the oppressor(s) results in the scenario ending in an undesirable way for the protagonist. An oppressor is a person/structure/belief system that presents a challenge to the oppressed. The play is performed to spect-actors (audience is both spectator ‘spect’ and ‘actor’) and then a facilitator (also known as a Joker) asks the spect-actors to discuss the play. The play is re-performed, enabling the spect-actors to intervene, when they notice a challenge for the protagonist. Thereafter, the spect-actor might swap roles with an actor, offer alternatives or questions. As such, the spect-actor attempts to change the scenario while the antagonist seeks to remain resolute to the original performance (Boal, 1995). Instead of the FT being one scene, Burton (2015) adapted it to be performed over three with peer teaching – he terms this enhanced FT. Pupils observered all three scenes and then provided alternative solutions to de-escalate the conflict between the characters. Using a mixed-method research design, the researcher’s suggest that pupils increased their understanding of why people bully and its consequences, while also noting a decline in school bullying incidents and an increase in self-confidence and esteem amongst those being bullied (Burton, 2015). Due to data on using drama to investigate bullying, Ross and Nelson (2014) recommends that therapists adopt it to address social functioning, peer-relationships and conflict management with school pupils.

Previous Studies Using Drama During Primary-Secondary Transitions

Few studies have adopted a drama pedagogy during primary-secondary transition (Jindal-Snape et al., 2011). Those studies that have adopted drama approaches suggest it creates an emancipatory transition pedagogy developing pupils’ well-being, social skills, agency and motivation (Walsh-Bowers, 1992; Jindal-Snape et al., 2011; Hammond, 2016). Walsh-Bowers (1992) Canadian study, used drama to support 103 rural incoming junior high school pupils (from 8 schools) which minimized their transition anxiety. They concluded that it had a positive experience on social-development, emotional understanding, motivation, and reduced stress levels (Walsh-Bowers, 1992). Jindal-Snape et al. (2011) used creative drama approaches to investigate primary-secondary transition which involved 357 pupils, 12 teachers and 4 drama professional facilitators. The study suggested that the drama intervention effectively supported pupils’ understanding of the emotional issues relating to transition due to the establishment of an emotional safety-net. In addition, their study indicated that drama enabled pupils to create realistic scenarios, with a degree of anonymity, while empowering them to rehearse real life transition contexts and creating an engaging learning environment irrespective of academic ability (Jindal-Snape et al., 2011). Hammond (2016) used FT to understand how pupils and teachers made sense of, and overcame, transition barriers. His study concluded that FT supports pupils’ transition by promoting their assertiveness, self-talk, resilience, ability to make friends and have discussions with adults (Hammond, 2016).

Summary of Literature

Primary-secondary transition research highlights that transition can be an emancipatory experience. However, for some pupils, primary-secondary transition can negatively impact learning and social well-being (Jindal-Snape, 2016). While it is important to recognize the experiences of all pupils (positive and negative), Jindal-Snape et al. (2019) literature review suggests that transition research predominantly focuses on negative rather than positive transition experiences. Therefore, it could be argued that it is important to discuss and support pupils through a pedagogy that focuses on their voice and promotes the positive aspects of transition. In doing so, educators might begin to scaffold pupils, by enabling them to discuss their transition issues in a secure space without it ever becoming a comfort zone (Neelands, 2009). Unfortunately, there are few studies reporting on using drama (in its multiple forms) at transition. This is unusual as play, the forerunner to drama, is a natural mode of communication for many pupils (Hammond, 2016).

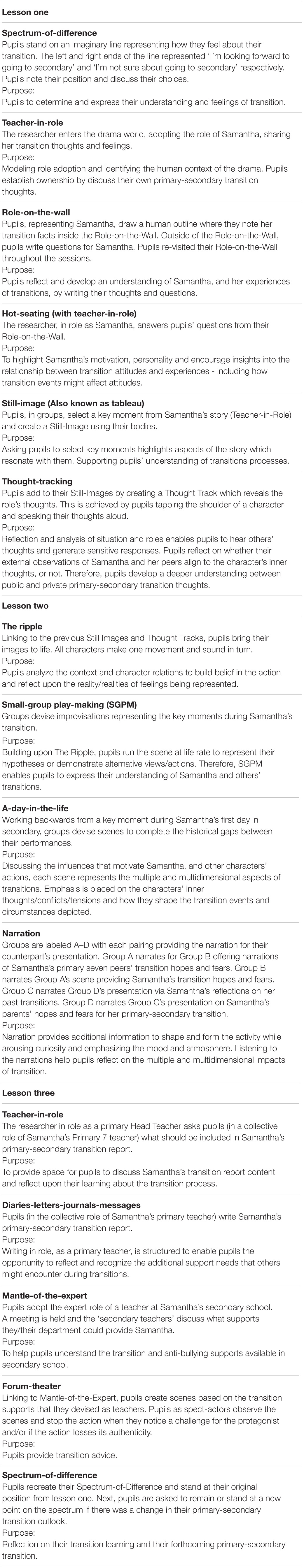

Drama Conventions Structured in This Study

Three one-and-a-half-hour drama lessons were facilitated in each primary school. The stimulus centered on a fictional character called Samantha which included her hopes and fears for making friends, not fitting in, moving to a bigger school and getting lost, gaining greater independence, experiencing new subjects/teachers and challenging herself academically.

Methodological Approach and Methods

This study was implemented in three primary schools and their associated secondary school on the west coast of Scotland. In Scotland, pupils move to secondary between the ages of 11.5 and 12.5; therefore, pupil participant ages ranged from 11 to 13.5 years old. Unlike previous studies using drama at transition (Walsh-Bowers, 1992; Jindal-Snape et al., 2011; Hammond, 2016), this study gathered data in three ethnically diverse urban primary schools, with high levels of multiple deprivation, and the associated secondary. Furthermore, the researcher was a participant-observer (Bryman, 2012) working alongside the pupils/teachers in role via the drama convention Teacher-in-Role or Teacher-out-of-Role (Neelands and Goode, 2015). Several sources of data were used to crystallize the complexity of multiple perspectives offered (Richardson and St Pierre, 2005).

Sample and Recruitment

Pupils

Final year primary pupils enrolled in the study irrespective of whether they were intending to move to the associated secondary school or not. This ensured that any potential benefits were experienced by all pupils and, as the study was implemented during the school day, limited cover issues for pupils and staff. The researcher organized an information sharing event in each school and issued pupil research booklets, consent forms, answered questions and reminded pupils of their rights, including that of withdrawal; no pupil exercised this right. The questionnaire was issued at the end of the final lesson and all pupils, who attended the associated secondary school, completed a subsequent questionnaire at the end of the first academic semester. A pupil focus group was undertaken in each primary school with six randomly chosen pupils.

Teachers

Each of the three primary school’s final year primary seven teachers participated in the study as partial participant observers (Bryman, 2012). All three teachers completed an observation protocol sheet during the lessons and participated in a one-to-one semi-structured interview.

Research Design, Methods, Analysis and Ethics

A multiple case study approach was adopted. Case studies are bound in a specific time and place where the researcher gathers data, from multiple sources, which are rich in context (Creswell, 2014). They are easily understood by a wide range of audiences due to the ability of the writer to describe the study’s unique features and events (often spontaneous and uncontrollable) (Nisbet and Watt, 1984). This means that results are not generalizable and can be prone to observer bias despite attempts toward reflexive practice by the researcher (Nisbet and Watt, 1984). In addition, participants’ memories may bias their interpretation of events (Shaughnessy et al., 2003). Despite these issues, case studies are used by drama education researchers due to the methodology striking a chord, ‘…with the forms of knowledge created by the art form of drama itself’ (Winston, 2006: 43). Therefore, the flexibility offered in a case study approach meets the special condition of drama education by responding, in real time, to pupils’ actions and meaning making.

Questionnaires

Open questionnaires were designed to enable pupils to write freely without the limitations of pre-set answers, thus allowing detailed and fuller responses (Cohen et al., 2011) and providing ‘illuminating clarification’ (Bucknall, 2014: 76). Questions were phrased to prevent any leading responses and used appropriate language (Munn and Drever, 1990). A questionnaire was issued at the end of lesson three and recorded pupils’ reflections over the lessons. An example question was ‘What does transition mean to you?’ which aimed to understand pupils’ conceptualization of transitions. A secondary school questionnaire was issued at the end of the first academic semester to consider pupils’ reflections of primary-secondary transition in the secondary context. An example question was ‘Have you experienced, or seen anyone experience, bullying like Samantha encountered? If so, what was it and did the drama lessons help you deal it?’, which aimed to understand if pupils recognized Samantha’s experiences in their own primary-secondary transition, and if they used the supports outlined in the drama in the real world.

Teacher Semi-Structured Interviews

Menter et al. (2011) suggests that the conversational tone of a semi-structured interview, enables interviewees to develop a narrative based on their specific experiences. In turn, the researcher matched questions to the teachers’ observations. However, as the researcher was a colleague of the teachers it meant that extra emphasis was required to promote the ethical safeguards surrounding confidentiality and anonymity. Observation protocol sheets were used, during the 45-min interview, to stimulate the discussion. Interview notes, written by the researcher (specific to the teacher) were provided for member checking. An example question was ‘How did the drama work support pupils to navigate their primary-secondary transition hopes and fears?’ which aimed to understand the teachers’ thoughts on using drama to support pupils’ primary-secondary transition.

Pupil Focus Groups

Focus groups enable pupils to discuss their views, attitudes and experiences relating to the research (Menter et al., 2011). A focus group of six pupils (three males and females - randomly chosen by the teacher to limit researcher bias) was convened in a breakout area after the third lesson and lasted approximately thirty minutes. Pupils were reminded of their research rights and offered the recording equipment to control. General questions on the drama were asked followed by more specific ones on primary-secondary transition. The researcher notes were summarized and offered for member checking. The purpose of the focus group was to support the other data sets by gaining a deeper understanding of pupils’ experiences of using drama before their transition to secondary school. An example question was, ‘Bullying was an important topic in your drama, why was this and what have you learned about bullying through drama?’, which aimed to understand the relevance of bullying in the drama and how this related to pupils’ real world experiences.

Teacher Observations of Sessions

As the researcher was participating alongside the pupils it was necessary for the teacher to record the lesson events in a protocol sheet (Creswell, 2014). This study adopted a similar protocol sheet to the one used by McNaughton (2008), which was separated into each section of the drama (Creswell, 2014).

Researcher Diary

Research diaries have been used widely in drama education to record and explore participants’ voices and support teacher-researcher’s analysis of the drama process (Taylor, 1998). Therefore, the diary approach adopted in this study was to log and reflect on the activities (Bryman, 2012). This enabled the researcher to dialog with himself surrounding the emerging issues in the drama and were written-up after each session (Taylor, 1998).

Data Analysis

Data analysis commenced after each data collection point. Using Miles et al. (2014) framework for qualitative analysis, the researcher initially familiarized himself with the data at each stage by reading the collective response and drilling down into individual responses. Next, the data was transcribed and assigned first level descriptive codes for sorting. Second level pattern codes were used to group the first level codes together to form emerging patterns. Thereafter, the pattern codes were mapped, and points of communality emerged as themes which unified the codes.

Results

See Table 1 for an overview of the named conventions.

Primary-Secondary Transition Conceptualization

Pre-transition Data

During Spectrum-of-Difference teachers noted that most pupils looked forward to secondary,

Most children on plus side a minority on minus side. Good justification–losing friends/new friends. Dislike of primary. New subjects. (Teacher L, Observation protocol sheet).

The majority of pupils stated that they were excited about their transition,

I feel excited because it is going to be different from [primary school] (School L, questionnaire pupil 4).

However, some pupils remarked that,

I am a little bit worried to go to [secondary school] (School P, questionnaire pupil 18)

While others commented that they had a mixture of emotions,

I’m excited cause you can do art and music and my brother is in second year. But I’m kinda sad about leaving [primary school’s name] cause I’ll miss my friends and [class teacher’s name] says that the work is harder and I need help with my work so I’m not sure about it (School G, questionnaire pupil 21).

The researcher noted that some pupils’ position on the line didn’t reflect their transition feelings,

It was interesting to see that the pupils didn’t always stand on the Spectrum-of-Difference which bore a true reflection of their feelings. One pupil said, “I just didn’t want to upset my friends who aren’t looking forward to going because I was happy to go” (Researcher’s diary - notes on school L pupil 9’s comments).

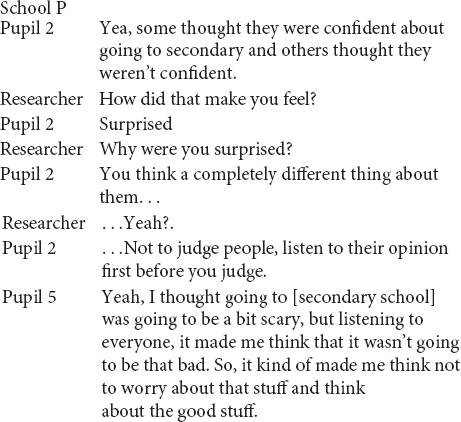

During the focus group, pupils were surprised at their peers’ location on the Spectrum-of-Difference,

Teachers noted that Spectrum-of-Difference helped to hear transition perspectives,

The line thing, it was also good for the ones who had negative feelings knowing that there were other people who felt the same as them (Teacher L - Semi-structured interview).

However, some pupils’ stance on the Spectrum-of-Difference surprised them,

It was more the line about who was going to be sad to go and who wanted to go as there were quite a few boys who wanted to stay that surprised me - how honest they were about their feelings (Teacher P - Semi-structured interview).

Teacher P (Observation protocol sheet) indicated that the drama was,

…effective in exploring and developing the story and understanding their mixed emotions and what transition meant to them.

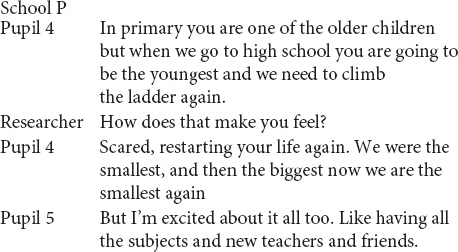

During the pupil focus group some pupils reflected that the drama supported their changing status in relation to the ‘Big Fish Little Pond Effect (BFLPE)’ (Seaton et al., 2009),

Pupils’ conceptual understanding of transitions advanced during ‘A-Day-in-the-Life’,

When we did the 24 h (sic) thing, you gotta see how one bit hit another bit and how your mum and dad feel and the teacher, cause (sic) they can get sad about you going to [secondary school] and they don’t want you to be sad, and they’ve got other stuff happen (sic) as well like my little sister and going to work and how she will get me there (sic) [school]. So it’s like just showing you how going to [secondary school] can hit everyone. I dinny (sic) really think that me going to [secondary school] done that (School G – questionnaire pupil 8).

Understanding transition consequences and pupils’ hopes and fears was discussed through Forum Theater,

Post-transition Data (Secondary Questionnaire Data)

Pupil 4 reflected that their Tableaux (an alternative name for Still-Image) helped their understanding of others’ transition thoughts,

It was very fun (sic) and we all did tableaus (sic) and helped Samantha. We learned how some people react in secondary school and need help fitting in.

Pupil 31 noted that the drama helped alleviate their concerns around the ‘BFLPE’ (Seaton et al., 2009) by developing their confidence,

I was worried about moving up to [secondary school]. I think that now I am more confident and my thoughts are that it made me feel better.

Pupil 26 reflected that the drama work also advanced their understanding of transitions,

I thought it was good because it helped me get ready for [secondary school] and that we are all doing transitions all the time.

Friendships

Pre-transition Data

Pupils recognized that friendships alter during transitions,

I will miss my friends cause some of my friends are going to a different school (School G pupil 16 - Questionnaire 1).

Friendships were discussed during Teacher-in-Role,

Once the researcher de-roled the pupils questioned Samantha, which focused on social emotional issues,

It was interesting that the pupils centered their questions to Samantha on social emotional issues - “Do you still have your primary school pals?” “Have you ever been bullied?” – were these questions based on their own hopes and fears? (Research diary - notes of questions asked by pupils 7 and 14 School L)

Hot-Seating helped pupils devise relevant transition questions and offer advice,

Generating good qs to ask Sam - Good feedback too. Great advice offered: “Everyone feels like this. We can make new friends together. We are all human.” (Teacher G - Observation protocol sheet).

By asking relevant questions pupils suggested that,

While recognizing the importance of maintaining friends during transition,

Children identify that friendships are important for a successful transition (Teacher L - Observation protocol sheet).

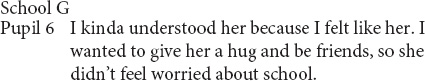

During the Still-Images, pupils created a caring image of students gathered around Samantha

Once the pupils performed their Still-Image I asked the class what they thought was happening in the image. One pupil responded, “They just want to be pals together, sir, so that they are all going to help each other when they get to [secondary school].” I was struck at the importance the pupils placed on having strong friendship bonds going into secondary school – was this their way of highlighting the importance of social and emotional aspects of primary-secondary transitions? (Researcher diary - School G.).

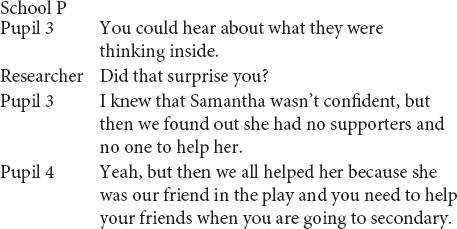

In School P, pupils layered a Still-Image with Thought Tracking to gain a greater understanding of their character’s transition thoughts,

Teachers felt that layering Still-Images and Thought Tracking developed pupils’ understanding of friendships by vocalizing internal dialogs,

I think it is a good thing for the transition. I think when you touched them on their shoulders, they were able to speak in role, you could see the Thought Tracking and you could see they were very in tune with the character. You could see the empathy toward their friends (Teacher L - Semi-structured Interview).

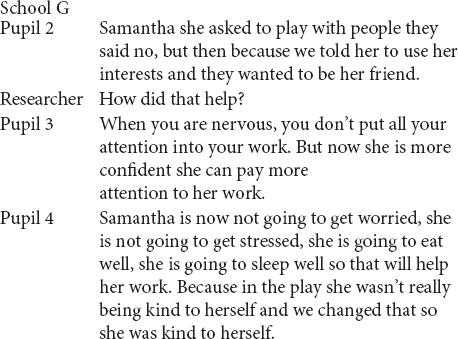

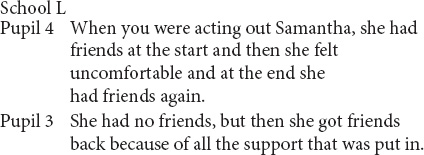

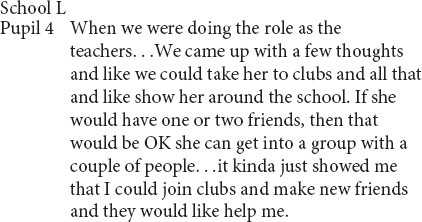

During Mantle of the Expert pupils explained ways for Samantha (and themselves) to make friends in secondary school,

Post-transition Data (Secondary Questionnaire Data)

Developing friendships through drama was noted by pupil 32,

You get used to the school and you have your old friends and we all help each other. I got lost in the corridors and [teacher’s name] helped me find my class and you make new friends because there are nice people in [secondary school] so it’s good to have friends.

The impact of this was highlighted by pupil 4,

In primary I done a play about Samantha coming to [secondary school] and it helped me now (sic) how to make new friends and no (sic) worry if ma (sic) old friends stop being ma (sic) friends becose (sic) I can make new ones.

Bullying

Pre-transition Data

Some pupils indicated fears of being bullied,

I’m nervous because people say that you get bullied (School L pupil 11’s comments).

The theme of bullying became a central component during Still-Images,

My favorite part was when we did the images about Samantha getting bullied because I now (sic) what it feels like to be bullied (School P pupil 2 - Questionnaire 1).

Small-Group Play-Making built upon pupils’ Still-Images and Thought Tracks and were used to create short rehearsed improvisations on the bully’s motivations. The pupils indicated that the bullies bullied Samantha to increase their status,

Acting in groups – because it’s telling you how some people treat others just because they want to be popular or cool (School G pupil 2 - Questionnaire 1).

The bully’s motives were discussed during the pupil focus groups,

Pupils suggested that A-Day-in-the-Life helped them understand the available anti-bullying supports,

Teacher L (Teacher L - Observation protocol sheet) noted,

I liked it when there seemed to be quite a lot about bullying and when they had to be the teacher. I think that seemed to cause more of a dilemma for them because, while they always want to be the teacher and be in charge, I think when they had to come up with solutions, they found this difficult. I think that is good because it’s making them have to think and see something from a different perspective and try and empathize as well.

Teacher G felt that the drama helped pupils discuss their behaviors at transition,

The drama allowed them to understand her behavior and relate it to their own transition. I don’t think they would have been able to do this without the drama (Observation protocol Sheet - Teacher G).

In summary, Teacher G (Observational Protocol sheet) suggest that learning about bullying through drama,

…was good because it was making them think more critically rather than being told, sort of making them explore and investigate rather than just listen.

Post-transition Data (Secondary Questionnaire Data)

Pupils indicated that drama helped them recognize bullying behaviors at transitions,

It was good because it helped us about bullying and if anyone was being bullied to help them (pupil 6).

And that they would support peers by asking them,

what’s wrong and try to help because telling feelings to someone might stop something wrong happening (pupil 21).

Pupils reflected that the drama supported their empathetic skills,

Yes, a little bit because I kind of knew what it must be like for her (pupil 9).

Pupil 2 noted that the drama taught him/her what to do when witnessing bullying,

I saw a boy called [pupil’s name] getting bullied and I told him to go to the office to go see the HT. It did help me because we told Samantha to tell a teacher.

Some pupils that had encountered bullying suggested,

A boy called [pupil’s name] was being mean to me and it made me think about Sam and that I shouldn’t just take it and that nobody should be treated that way because it is not fair to the person who’s getting bullied. So, after a bit I told and Mr. [teacher’s name] and he said to [pupil’s name] and he hasn’t been mean to me since (pupil 17).

However, some pupils noted that the bullying scenarios didn’t transfer into reality,

I thought that many people bullied and pushed to the side and nobody should be treated that way but it doesn’t happen (pupil 27).

Pupil 38 suggested that the drama helped their transition learning,

When you are acting it out you are experiencing it, and then when the teacher tells you it just sounds like a bunch of words, but when you are experiencing it, you feel it.

Discussion

See Table 1 for an overview of the named conventions.

Pupil Primary-Secondary Transition Conceptualization

Jindal-Snape et al. (2020) argue that few primary-secondary studies have sought to understand pupils’ conceptualization of primary-secondary transition transition. In addition, often international transition studies often focus on the negative discourses (Jindal-Snape et al., 2020). However, when pupils were asked about their primary-secondary transition, the majority indicated that they were looking forward to the new opportunities such as making friends and experiencing new subjects. This supports Jindal-Snape et al. (2020) findings that transitions do not necessarily translate to negative prospect for all pupils. Though, this is not to say that pupils did not have any negative or mixed transition feelings. Indeed, the drama activity supported pupils’ understanding of the range of transition perspectives. For example, when pupils discussed their conceptualization of primary-secondary transition, through Spectrum- of-Difference, they indicated that they viewed their transition, and their changing status, through the construct of ‘Big Fish Little Fish Effect (Seaton et al., 2009). This resulted in some pupils voicing their mixed feelings toward transition and concerns of being the biggest pupils in primary to the smallest in secondary. Also, some pupils voiced concerns regarding being bullied in secondary school and missing their teacher; these issues are often discussed in the international literature (Symonds, 2015). Some pupils’ opinions regarding their transitions surprised their teacher. This raises questions as to how the pupil/learner voice was heard before the drama intervention. Indeed, if pupils were previously voiceless during their transition learning, then there is a chance that their needs might not have been supported as the teacher did not anticipate any additional support needs for said pupils. However, as Jindal-Snape et al. (2019) suggest, the process of primary-secondary transition can cause additional support needs (ASN) for pupils irrespective to whether they have an ASN record or not. Therefore, it is important that pupils can explore and express their transition conceptualization and understanding before any move. In doing so, this might afford pupils the opportunity to express their feelings and discuss supports with peers and teacher(s) (Jindal-Snape, 2012).

Although most pupils indicated that they were looking forward to their transition, during the Spectrum-of-Difference some deliberately stood at points which didn’t reflect their transition feelings. When asked why, pupils indicated that they didn’t wish to upset peers, who were worried about the transition, as they were looking forward to their own transition. While this displays empathy and a recognition of their peers’ needs, it also highlights that some pupils did not view transition as a single event that only impacted them. Instead, pupils recognized the interconnectedness of the transition process, and that some of their peers would require additional support (Neelands, 2009; Jindal-Snape, 2016).

As pupils structured the drama work, their understanding of the multiple and multidimensional transitions which influence their primary-secondary transition developed (Jindal-Snape, 2016). For example, during ‘A-Day-in-the-Life’ pupils collectively worked through timeframes in their school day - breakfast (with their family), getting to school, first period, lunchtime with peers and going home/spending time with their family. School G pupil 8 recognized that the protagonist’s transitions exacerbated other transitions for his/her family. In doing so, the pupil was cognizant that his/her transition would impact his/her mum, dad and teacher’s feelings. Moreover, the pupil was also alert to how his/her transition would impact on travel arrangements and childcare implications for his/her sibling. Therefore, pupil 8 conceptualization of transitions possibly developed due to his/her involvement in the drama activity (Jindal-Snape, 2016).

During Forum Theater, pupils recognized their influence on the success of their transition. By stopping the action and offering alternatives, pupils discussed how they could alter Samantha’s transition through reflection, collaboration and compromise (Boudreault, 2010). By problem solving Samantha’s transition issues, pupils merged their thoughts and feelings collectively to create multiple realities for the characters and in turn related these to their own lives. Therefore, during the drama conventions pupils collectively and individually found a way to have their views listened to and actioned, in a meaningful manner, which is essential for their self-determination (Deci and Ryan, 2010).

Friendships

A support network is important during primary-secondary transition and having friends to guide one another through the process can contribute to positive mental health (Miller et al., 2015). Pupils indicated, during Spectrum-of-Difference, that moving with friends to their secondary school is important for a successful transition (Jindal-Snape, 2019). During Teacher-in-Role, pupils highlighted how losing friends might negatively impact Samantha’s (and their own) transition. This is not surprising as friends become just as important as parents/carers for offering social support and advice during transitions (Bokhorst et al., 2010). For example, during the Still-Images pupils advanced their understanding of the transition narrative by focusing and reflecting on a key moment in Samantha’s transition journey which focused on her need for secure friendships (Woolland, 2014). This suggests that the pupil used Still-Image to enact their ideas and visualize their thinking around the need for secure friendship during transition (Hertzberg, 2001).

The theme of friendships during transitions was furthered when pupils layered their Still-Images through Thought-Tracking. In doing so, pupils pledged their friendship toward Samantha and stated that they would help others experiencing similar situations. It appears that pupils were suggesting that a ‘snowball effect’ would be created to establish new friendships (Weller, 2007). This was furthered during Mantle of the Expert when pupils, playing the role of teacher, suggested creating groups for Samantha to join, enabling her to have likeminded individuals to play alongside. Symonds (2015) suggests that when teachers group pupils together, based on their subject interests, it offers them a homogenous group of peers to establish new friendships. Therefore, the pupils’ suggestions during Mantle of the Expert was akin to what would happen in the real world. This suggests that pupils based their fictional ideas on their understanding of transition supports, prior experiences of groupings and empathy for peers. Furthermore, by attempting to solve Samantha’s friendship concerns, pupils were also aiming to alleviate their own worries on this matter (Prendiville and Toye, 2007). This might be due to the drama’s ability to provide pupils with opportunities to test themselves in imaginary scenarios and rehearse issues which are concerning them through the guise of a character. When pupils are in character it provides a degree of anonymity as they can discuss their transition concerns as if it were the character speaking and not themselves (Jindal-Snape et al., 2011). Therefore, drama provides an imaginative frame to test themselves within the fictional world, gain insights and provide hope to their real-world pursuits (Barton and Booth, 1990).

The drama may have enabled pupils to develop closer bonds with their friends in primary and provided them with strategies to make new ones in secondary school. Indeed, pupils throughout the drama declared that they would help one another in their move to secondary school. This might have created a sense of solidarity between the pupils (Garcia, 1998) and a second order identity as people grappling together (Neelands, 2007). For example, pupils created scenarios where they offered one another protection from social isolation and victimization. In doing so, pupils attempted to understand others’ needs and values while reflecting on their wants (Neelands, 2007). Therefore, by walking in someone’s shoes, pupils paused their own world to act ‘as if’ in order to problem solve while developing their empathetic skills (Hammond, 2016). Hammond (2016) suggests that pupils can develop their empathetic skills through reflection and discussion by considering the context, cultural beliefs, social norms and personal experiences investigated in the work. This supports teacher L’s comments that the pupils were ‘in tune’ with the characters and thus developed a greater connection with their friends before transition. High quality friendships and good relationships with classmates help to support pupil self-esteem and resilience during transitions (Symonds, 2015). This was confirmed through the secondary questionnaires which suggested the drama helped them to maintain their primary friendships, and provided them with the confidence to make new friends in secondary.

Bullying

Most scenes centered around the theme of bullying. This isn’t surprising as international transition research indicates that bullying concerns can be a significant stressor during the primary-secondary transition process (Pellegrini and Long, 2002). However, during the discussion and reflection on the drama, most pupils indicated that they didn’t think that they would be bullied in secondary school, though they did wish to help those who were being bullied. This is unsurprising as pupils often take a strong stance regarding the justice and fairness of the drama they are creating (Neelands, 1992). It appears that working collectively to problem-solve the central issue of bullying, helped pupils to be supportive of one another (Baldwin, 2012). Similarly, Burton (2015) indicates that drama is a suitable approach to use to investigate the complexities of bullying in a safe and secure manner. Indeed, Jindal-Snape (2012) highlights that using drama to create and investigate transition issues like bullying helps develop pupils’ self-esteem, confidence and resilience.

Through the creation of bullying scenes, pupils challenged their beliefs on the issue being investigated (Bolton and Heathcote, 1998). As such, pupils developed empathy toward the bully victims and their understanding of the consequences of bullying. This is like Joronen et al. (2012) findings where drama helped pupils’ understanding of the causes of bullying. Indeed, pupils indicated that due to their participation in the drama, and reflection on it, that they were able to effectively deal with bullying incidents in secondary school (Burton, 2015).

To effectively deal with potential bullying incidents, pupils discussed their feelings around bullying with one another and sought to activate change. Their actions within the drama world became a template as to how they might react in similar scenarios within the real world. For example, during the Still-Images pupils discussed a bullying moment in Samantha’s life outside of the fiction and then created this in the drama world. In doing so, pupils discussed their bullying concerns in a secure space and then attempted to crystallize their understanding through the fiction. The pupils then layered the Still-Image with a Thought Track to increase their understanding of the character’s purpose in the scene. Therefore, pupils created an approach to articulate their character’s thoughts by giving a psychological commentary of the physical action (Neelands and Goode, 2015).

Increasing pupil understanding of character’s psychological make-up empowered pupils to suggest supports to be actioned in secondary school. This was most notable during the Mantle of the Expert activity where pupils assume expert roles as teachers in order to effect positive change for Samantha. For example, pupils wrote in role explaining what they would do as teachers to support Samantha’s transition. The teachers and pupils reported that this developed their understanding of the collective supports available during the transition process and helped minimize their bullying anxieties. This concurs with Baldwin and Fleming (2003) suggestion that when pupils write in role they begin to empathize with others and experience multiple behaviors.

In secondary school, most pupils indicated that they didn’t directly experience bullying themselves, though did notice others being bullied or bullying. The pupils suggested that the drama work helped them recognize bullying incidents and how to support those being bullied by showing kindness by advocating for the bully victim. Pupils indicated that enacting the scenarios supported them in offering advice and directing a bully victim to the Head Teacher. In addition, some pupils indicated that they had encountered bullying incidents and due to their involvement in the drama, they were reminded of what Samantha did to end it. This suggests that the pupils were linking their learning in the fiction to the real world and positively benefitted as a result. The pupils’ experience helped to socially construct a shared understanding of what bullying is, and how this comes to impact people individually or as part of a wider grouping, and how they can stop and prevent it from continuing (Neelands, 2009). Therefore, due to pupils’ engagement and creation of the drama world, based on their transition questions, they explored issues which were meaningful to their needs (Rousseau et al., 2007). It appears that using drama to create a problem-solving pedagogy enabled pupils to collectively respond to universal concerns like bullying. This then created a pedagogy where pupils could enact fiction based on their hopes and concerns by providing meaningful child-centered responses which could be reflected and actioned in the real world (Mavroudis and Bournelli, 2016). In turn, pupils reported that using drama helped reduce their bullying concerns and provided them with strategies to use in secondary school.

Conclusion

Using drama conventions appears to be a suitable problem-based pedagogy focusing on pupil emotional and social skill enhancement. It creates a positive transition discourse by empowering pupils to establish a sense of belonging with peers before moving to secondary. This was achieved by pupils creating peer networks, generated through drama group work, which continued during the first term of secondary school. Pupil exploration of transition hopes and diminishing bullying fears and friendships during primary-secondary transition was developed in a sensitive and non-threatening manner. This is due to pupils working together, through an aesthetic medium, to increase their understanding and respect for others’ perspectives. For example, the use of a metaphorical emotional safety-net, through the process of acting ‘as if,’ supported a felt understanding which provides pupils with role anonymity to express their transition thoughts and feelings. In turn, this enabled pupils to advance their understanding of abstract transition constructs through a fictional lens, which empowers them to collectively meaning make and support one another’s transition process. Pupils suggest that this was an appropriate way to learn about primary-secondary transition, and the issues surrounding bullying and friendships; more so than traditional teaching approaches. For example, pupils offered tangible pupil-led strategies to reduce bullying during their transitions and maintain/forge new friendships in secondary school. In addition, pupils developed their friendships, which is a significant aspect for a successful transition, and reported that working alongside their peers helped them to alleviate their transition concerns. Furthermore, pupils’ conceptualization of primary-secondary transition appears to have developed from a movement between sectors to an ongoing process. Therefore, the use of drama conventions to support the teaching and learning regarding primary-secondary transition, particularly the issues surrounding bullying and friendships, should be undertaken in primary classrooms and potentially meets, in part, the recommendations outlined by Jindal-Snape et al. (2019).

Recommendations for Future Research

Drama research is required to discuss the implication of this study in a mixture of locations (rural and urban). Future research should adopt drama strategies in both primary and secondary settings via a bridging unit exploring pre and post primary-secondary transition issues. However, due to the conceptualization of transitions as multiple and multidimensional, research should also investigate how drama might support ongoing transitions throughout the school and wider life. In addition, in recognition to Jindal-Snape et al. (2019) recommendations, this should include a full range of participants (e.g., pupils, teachers and parents – including those with additional support needs), to provide a rich interpretation of multiple transition perspectives. Furthermore, multiple perspectives should also include pupils who are looked after by the state and those with English as an additional language. In doing so, additional longitudinal data, via a mixture of qualitative and quantitative designs, could be gathered to show any impact and insight for a wide range of pupils from multiple contexts and (potentially) social-economic backgrounds.

Limitations

There are limitations to this study. The sample size altered between primary and secondary - this was mainly due to pupil absenteeism and transitioning to an alternative secondary school. However, as Jindal-Snape and Cantali (2019) indicate, attrition is inevitable in studies where pupils volunteer. This study was implemented in one Scottish Local Authority with one secondary and its three associated primary schools. A case study design means that the findings cannot be generalized; despite the issues raised being like the limited studies using drama at transitions and wider international literature. The participants’ views were given freely, and data recordings were shared with them for member checking. However, due to the power imbalance between a participant and researcher, it is feasible to suggest that the trustworthiness of their views might have been affected. There was no drama intervention implemented in the secondary school. Although this study addresses Jindal-Snape et al. (2011) suggestion for a longitudinal study it does not provide data for ongoing transitions throughout secondary education. No data was gathered from parents/carers or pupils with additional support needs.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of Strathclyde. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The handling Editor declared a past co-authorship with the author.

References

Alexander, R. (ed.) (2010). Children, their world, their education: Final report and recommendations of the Cambridge Primary Review. New York, NY: Routledge.

Alton-Lee, A. (2003). Quality Teaching for Diverse Students in Schooling: Best Evidence Synthesis. Wellington, New Zealand: Ministry of Education.

Bagshaw, D., and Lepp, M. (2005). Ethical considerations in drama and conflict resolution research in Swedish and Australian schools. Conflict Resolut. Q. 22, 381–396. doi: 10.1002/crq.109

Baldwin, P. (2012). With drama in Mind: Real Learning in Imagined World, 2nd Edn. Stafford: Network Educational Press Ltd.

Baldwin, P., and Fleming, K. (2003). Teaching Literacy through Drama. New York, NY: Routledge Falmer.

Bancroft, S., Fawcett, M., and Hay, P. (2008). Researching Children Researching the World: 5 × 5 × 5 = Creativity. Stoke-on-Trent: Trentham Books.

Barton, B., and Booth, D. (1990). Stories in the Classroom: Storytelling, Reading Aloud and Roleplaying with Children. Markham. Ontario: Pembroke Publishers Ltd.

Beale, A. V., and Scott, P. C. (2001). “Bullybusters”: using drama to empower students to take a stand against bullying behavior. Prof. Sch. Counsel. 4, 300–305.

Bokhorst, L. C., Sumter, R. S., and Westenberg, M. P. (2010). Social support from parents, friends, classmates, and teachers in children and adolescents aged 9 to 18 years: who is perceived as most supportive? Soc. Dev. 19, 417–426. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00540.x

Bolton, G., and Heathcote, D. (1998). “Teaching culture through drama,” in Language Learning in Intercultural Perspective. Approaches through Drama and Ethnography, eds M. Byram and M. Fleming (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 158–177.

Boudreault, C. (2010). The benefits of using drama in the ESL/EFL Classroom. Internet TESL J. 16, 139–143.

Bruner, J. (1986). Two Modes of Thought Actual Minds, Possible Worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 11–43.

Bucknall, S. (2014). “Doing qualitative research with children and young people,” in Understanding Research with Children and Young People, eds A. Clark, R. Flewitt, M. Hammersley, and M. Robb (London: Sage), 69–84. doi: 10.4135/9781526435637.n5

Burton, B. (2015). “Drama, conflict and bullying: working with adolescent refugess,” in How Drama Activates Learning Contemporary Research and Practice. London and, eds M. Anderson and J. Dunn (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc), 64–77.

Caulfield, C., Hill, M., and Shelton, A. (2005). The Experiences of Black and Minority Ethnic Young People Following the Transition to Secondary School. Edinburgh: Scottish Council for Research in Education.

City of Birmingham Education Department (1975). Continuity in Education: Junior to Secondary. Birmingham: Birmingham Education Development Centre.

Clark, J., Dobson, W., Goode, T., and Neelands, J. (1997). Lessons for the Living: Drama and the Integrated Curriculum. Newmarket, ON: Mayfair Cornerstone.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., and Morrison, K. (2011). Research Methods in Education, 7th Edn. New York, NY: Routledge.

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th Edn. California: Sage Publications, Inc.

Cross, D., Shaw, T., Epstein, M., Pearce, N., Barnes, A., Burns, S., et al. (2018). Impact of the Friendly Schools whole-school intervention on transition to secondary school and adolescent bullying behaviour. Eur. J. Educ. 53, 495–513.

Crothers, L. M., Field, J. E., and Kolbert, J. B. (2005). Navigating power, control, and being nice: aggression in adolescent girls’ friendships. J. Counsel. Dev. 83, 349–354. doi: 10.1002/j.1556-6678.2005.tb00354.x

Davis, S., and Dolan, K. (2016). Contagious learning: drama, experience and “Perezhivanie”. Int. Res. Early Childhood Educ. 7, 50–67.

Deci, E. L., and Ryan, R. M. (2010). “Self-determination,” in The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology, eds C. Nemeroff and W. E. Craighead (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons), 1–2. doi: 10.1007/978-1-349-24918-3_1

Delamont, S. (1991). The HIT LIST and other horror stories: sex roles and school transfer. Sociol. Rev. 39, 238–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-954x.1991.tb02980.x

Farmer, T. W., Irvin, M. J., Motoca, L. M., Leung, M. C., Hutchins, B. C., Brooks, D. S., et al. (2015). Externalizing and internalizing behavior problems, peer affiliations, and bullying involvement across the transition to middle school. J. Emot. Behav. Disord. 23, 3–16. doi: 10.1177/1063426613491286

Fisher, T. A., and Smith, L. L. (2010). First do no harm: informed consent principles for trust and understanding in applied theatre practice. J. Appl. Arts Health 1, 157–164. doi: 10.1386/jaah.1.2.157_1

Galton, M. (2010). “Moving to secondary school: what do pupils in England say about the experience?’,” in Educational Transitions: Moving Stories from around the world, ed. D. Jindal-Snape (New York: Routledge), 107–124.

Garcia, L. (1998). Creating community in a university production of Bocon! Res. Drama Educ. 3, 155–166.

Goode, T. (2014). Exploring the fictions of reality. Drama Nordisk Dramapedagogisk Tidsskrift 3, 26–27.

Goodwin, J., Bradley, S. K., Donohoe, P., Queen, K., O’Shea, M., and Horgan, A. (2019). Bullying in schools: an evaluation of the use of drama in bullying prevention. J. Creat. Ment. Health 14, 329–342. doi: 10.1080/15401383.2019.1623147

Graves, K. N., Frabutt, J. M., and Vigliano, D. (2007). Teaching conflict resolution skills to middle and high school students through interactive drama and role play. J. Sch. Violence 6, 57–79. doi: 10.1300/j202v06n04_04

Hallinan, P., and Hallinan, P. (1992). Seven into eight will go: transition from primary to secondary school. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 9, 30–38. doi: 10.1017/s0816512200026663

Hammond, N. (2016). Making a drama out of transition: challenges and opportunities at times of change. Res. Pap. Educ. 31, 299–315. doi: 10.1080/02671522.2015.1029963

Heathcote, D. (1984). “Dorothy Heathcote’s notes,” in Dorothy Heathcote: Collected Writings on Education and Drama, eds L. Johnson and C. O’Neill (London: Hutchinson), 202–210.

Heathcote, D., and Bolton, G. (1994). Drama for Learning: Dorothy Heathcote’s Mantle of the Expert Approach to Education. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Hertzberg, M. (2001). Using Drama to Enhance the Reading of Narrative Texts. Available: http://www.proceedings.com.au/aate/aate_papers/105_hertzberg.htm (accessed March 2, 2020).

Heyward, P. (2010). Emotional engagement through drama: strategies to assist learning through role-play. Int. J. Teach. Learn. High. Educ. 22, 197–204.

Jindal-Snape, D. (2012). Portraying children’s voices through creative approaches to enhance their transition experience and improve the transition practice. Learn. Landsc. 6, 223–240. doi: 10.36510/learnland.v6i1.584

Jindal-Snape, D. (2018). “Transitions from early years to primary and primary to secondary,” in Scottish Education, Fifth Edn, eds T. G. K. Bryce, W. M. Humes, D. Gillies, and A. Kennedy (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press), 281–291.

Jindal-Snape, D. (2019). “Primary-secondary transition,” in Learning to Teach in the Secondary School: A Companion to School Experience, 8th Edn, eds S. Capel, M. Leask, and T. Tuner (Abingdon: Routledge), 184–197.

Jindal-Snape, D., and Cantali, D. (2019). A four-stage longitudinal study exploring pupils’ experiences, preparation and support systems during primary-secondary school transitions. Br. Educ. Res. J. 45, 1255–1278. doi: 10.1002/berj.3561

Jindal-Snape, D., Cantali, D., MacGillivray, S., and Hannah, E. (2019). Primary to Secondary School Transitions: Systematic Literature Review. Edinburgh: The Scottish Government.

Jindal-Snape, D., Hannah, F. S. H., Cantali, D., Barlow, W., and MacGillivray, S. (2020). Systematic literature review of primary secondary transitions: international research. Rev. Educ. 8, 526–566. doi: 10.1002/rev3.3197

Jindal-Snape, D., and Miller, D. J. (2008). A challenge of living? Understanding the psycho-social processes of the child during primary-secondary transition through resilience and self-esteem theories. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 20, 217–236. doi: 10.1007/s10648-008-9074-7

Jindal-Snape, D., Vettraino, E., Lowson, A., and McDuff, W. (2011). Using creative drama to facilitate primary–secondary transition. Int. J. Primary Element. Early Years Educ. 39, 383–394. doi: 10.1080/03004271003727531

Johnson, C. (2001). Helping children to manage emotions which trigger aggressive acts: an approach through Drama in School. Early Child Dev. Care 166, 109–118. doi: 10.1080/0300443011660109

Joronen, K., Konu, A., Rankin, H. S., and Åstedt-Kurki, P. (2012). An evaluation of a drama program to enhance social relationships and anti-bullying at elementary school: a controlled study. Health Promot. Int. 27, 5–14. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dar012

Karagiannopoulou, E. (1999). Stress on transfer from primary to secondary school: the contributions of A-trait, life events and family functioning. Psychol. Educ. Rev. 23, 27–32.