- School of Humanities, Education, Justice & Social Sciences, Lasell University, Newton, MA, United States

In this study, school professionals provided a rich context for understanding how collaboration can lead to learning when educating a child with deafblindness. Analysis of the collaboration of five professionals during an academic year showed that although they thought it was critical that they learn from each other, only one sub-set engaged in ways that led to rich learning opportunities. The findings from this study suggest that professional collaboration and learning, which is a hallmark of supporting learners with dual sensory loss, may be elusive even when it is a valued and mandated practice. In addition, professional learning more readily occurs when teachers are open to educating all children yet are also focused on how to best teach children with deafblindness.

From Fragmented Practice to Rich Professional Learning: the Collaborative Work of Teachers of Learners With Deafblindness

Teacher collaboration is often seen as a worthy practice because it is assumed that when teachers share knowledge and coordinate their individual practice, they exceed what they could do alone (Little, 2002; Brownell et al., 2006). This highly valued view of teacher collaboration is prevalent in the education of learners with deafblindness, a low-incidence disability with few teachers who have specific expertise and training (Luckner et al., 2016). Throughout the literature on deafblindness, professionals are called upon to share their specific disciplinary knowledge (e.g., expertise in special education or in a specific impairment such a vision or hearing) and coordinate efforts with their colleagues accordingly (Council for Exceptional Children, 2015; Parker and Nelson, 2016). The underlying assumption is that when teachers, therapists, and related service providers have limited specific content knowledge or pedagogical practices in deafblindness, they will learn from each other and this learning will lead to improved services and student outcomes (Giangreco et al., 1999).

Children with deafblindness are a low-incidence population of students with severe disabilities who typically receive services from large special educational teams (Giangreco et al., 1997, 1999). The U.S. federal definition of deafblindness is “concomitant hearing and visual impairments, the combination of which causes such severe communication and other developmental and educational needs that cannot be accommodated in special education programs solely for children with deafness or children with blindness” (Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act, 2004). This definition highlights the uniqueness of combined vision and hearing impairment. The senses of hearing and vision are critical to receiving information, especially information presented at a distance. When vision is impaired, often the sense of hearing is used in teaching to compensate for the loss and vice versa. However, if both of these sensory systems are impaired, it will be more difficult to compensate for the loss of information, and the child's access to critical information needed for development and learning is drastically reduced (Bruce, 2005).

Children who experience deafblindness from birth or from a very early age may have limited access to the kinds of opportunities that foster the development of early competencies. As a result, they need extensive educational support (Luckner et al., 2016) from different types of educational professionals. It is likely that these educators, therapists, and related service providers may not have an understanding of the unique nature of combined hearing and vision impairments (Parker and Nelson, 2016). Accordingly, they must be able and willing to work with each other to figure out how their individual knowledge and skills can be integrated to educate the student. For example, consider professionals who are teachers of students with visual impairments and blindness (TVIs) providing educational services to a child with deafblindness. TVIs will have expertise in how vision impairments affect learning and what kinds of individualized educational services or supports might help a learner with a visual impairment. It is not expected that all TVIs will have past experience or expertise in deafblindness, but they will be expected to collaborate with other professionals to learn about how deafblindness affects learning. Given the assumption that professionals, like TVIs, will need to learn from their colleagues it is worth asking, how do professionals learn from each other when they collaborate to provide educational services to a student with deafblindness?

Teacher Collaboration in Special Education, A Solution or Problem?

Research on professional collaboration when educating children with multiple disabilities and deafblindness has shown that teachers have faced many challenges. One study of educational teams of children with deafblindness found that these professionals' attitudes, views, and practices differed in ways that affected collaboration (Giangreco et al., 1997). The researchers asked 119 professionals on 20 teams whether they agreed or disagreed with 20 exemplary collaborative practices, for example, making decisions about how educational and related services should be delivered for children with deafblindness. On each team, there was evidence of significant differences in members' perceptions of collaboration. Some team members supported a less collaborative approach to services, which valued individual teacher expertise and encouraged members of the team to retain their autonomy, provide only direct services, and work on separate goals. Other team members thought that services for students with deafblindness should be more integrated and transdisciplinary.

In addition to differences in values, collaboration is hampered not only by the large number of teachers who serve children with deafblindness but also by their short tenure on the team. In 1999, Giangreco et al. examined the membership in 18 educational teams that served children with deafblindness by analyzing survey data. They found that, on average, each team consisted of 21 people (SD = 5.06), that 55% of team members changed each year, and 78% changed over in 3 years. Although there are no data to determine if such a percentage of turnover is atypical, it is reasonable to assume that this percentage of turnover year-to-year may hinder team development of the distributed expertise needed to effectively educate children with deafblindness.

Further compounding team member turnover, professionals who serve children with deafblindness may have limited or emerging knowledge of educating deafblind children (McLetchie and MacFarland, 1995). McLetchie and MacFarland found that only 6% of the teachers who work with students with deafblindness had specialized training in the field of deafblindness. A few years later, Corn and Ferrell (2000) found that the number of teacher education programs in deafblindness had decreased while the number of school-aged children with deafblindness had increased. All in all, the findings of these studies indicate that professionals in teams serving children with deafblindness may have little specialized training, may be on teams for a short amount of time, and may only learn about deafblindness as they provide service to children with deafblindness.

In contrast, other research has shown that specific types of collaborative practice can lead to positive teacher and student outcomes. For example, researchers (e.g., Goetz and O'Farrell, 1999; Janssen et al., 2003) have suggested that effective interventions for children with deafblindness need to be ongoing and emerge systematically from collaboration among educational team members. These researchers have found that collaborative practice led to improved outcomes when team members had: (a) access to training, (b) administrative support for collaboration, (c) regular team meetings, (d) development and implementation of action-based strategies, (e) mutually defined goals, (f) accountability, and (g) strong leadership and interpersonal skills.

Hunt et al. (2002, 2003) found that when teacher collaboration to support learners with deafblindness included evidence-based practices, including attending frequent meetings, discussing ongoing issues, and creating support plans, teachers felt positive about their collaboration and stated that collaboration improved student outcomes. In both studies, the researchers examined the effect of the collaborative teaming process on the teachers by analyzing interview data that elicited team members' perspectives. The researchers also measured levels of engagement and interaction patterns of the students using a multiple baseline design across students. The results indicated that teachers' participation in collaborative processes was associated with improved professional outcomes, in addition to improved outcomes for their students. Teacher collaboration was beneficial when teachers shared their expertise so that intervention was ongoing and implemented across various contexts. The authors suggested that school leadership should set an expectation for such collaboration and clearly create regularly scheduled opportunities and incentives for collaboration. In addition, these studies showed that collaboration among a smaller group of people within the larger educational team leads to positive teacher and child outcomes.

In sum, the research on teachers' work to support children with multiple disabilities, including deafblindness, has found that collaboration can be both a constructive and challenging endeavor. When teachers' work is sustained over time, supported, and clearly organized, learners and teachers benefit. On the other hand, there are many challenges teachers face when supporting children with deafblindness and not all collaboration leads to best or desired practice. Which raises the question, how can professionals better understand their collaboration as a context for learning about deafblindness?

What Do Professionals Learn From Collaboration?

Researchers (e.g., Little, 2002; Ainscow et al., 2003; Horn, 2007) have found that teachers' everyday learning (i.e., the kind of learning that occurs on the job in groups or communities) is an overlooked part of their professional practice because it is seen as being inherently beneficial. These researchers have suggested that Wenger's (1998) Communities of Practice (CoP) is a useful framework that may clarify how teachers interact with each other in school contexts. In addition, researchers have found that analysis using this framework has allowed them to investigate how teacher practice leads to learning in the workplace. Wenger (1998) stated that the relationship between practice and learning is not one in which practice is merely a context for learning. Instead, it is something deeper; learning occurs when people sustain enough mutual engagement in pursuing work together over time. In other words, learning is an ongoing social process in which we develop our practice and ability to negotiate meaning. Learning is not just the rote acquisition of knowledge or a static object to obtain and then pass down from one person to the next. Rather, it is the process of engaging and participating in ongoing practice. This is not to say that everything we do is learning, but rather that learning should be understood as the process of sustaining a specific practice.

Horn's (2005) research on the social nature of high school math teachers' beliefs used the CoP framework to research teacher interactions and how these led to learning in practice. One of Horn's findings was that the teachers had established a normative way of sharing stories about their classroom experiences. The sharing of stories allowed teachers in the group to analyze practice and appropriate responses. Moreover, it provided a way in which teachers could apply and examine their general values and principles, which supplemented, and in some cases supplanted, learning in formal professional development activities. Horn's research provided an important example of how the use of the CoP framework can assist in our understanding of how professionals learn from each other through their everyday practice.

In this study, the CoP framework was used to understand teacher collaboration as a context for professional learning about deafblindness. The research question of this study was, what kinds of collaborative practice led to professional learning about educating children with deafblindness? To answer this question, I examined the everyday practice of a group of professionals who lacked formal training in deafblindness education, but were tasked with coming together to provide comprehensive educational services for a learner with deafblindness across an academic year. Instead of assuming that teacher collaboration of various professionals leads to the integration of specific content knowledge or pedagogical practices in deafblindness, this study explored how teachers collaborated with each other and then how this collaborative practice either led to or hindered opportunities to learn about deafblindness.

Methods

This study was part of a larger comparative case study on the collaborative practice of two separate IEP teams supporting learners with deafblindness (see Hartmann, 2016). Whereas, the previous study focused on comparing and contrasting collaborative practice of two very large groups of professionals, this study focused on professional learning within one small subset of professionals on one team educating a learner with deafblindness. A case study method of inquiry was chosen because it was flexible in exploring the phenomena within its natural context, so as to gain insights into all of the inherent complexity of collaborative practice and the fundamental social and interpersonal dynamics and processes that shape and affect professional learning across an academic year. Similar to findings of previous research on professionals who serve children with deafblindness (Giangreco et al., 1999) the professionals were varied in their training, experience, and identity. In addition, the professionals had little or no training or past experience in teaching children with deafblindness and, as such, they provided an instrumental case to best understand how and what professionals learn about deafblindness from each other.

Participant Selection and Context

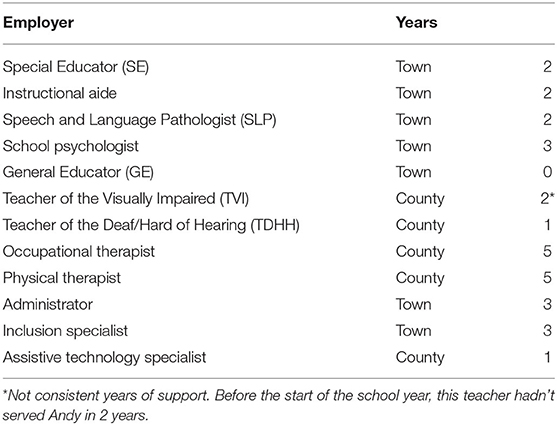

Purposeful maximal sampling was used to select a group of professionals who would engage in the kind of collaborative practice needed for in-depth analysis of how team members learn from each other. The professionals chosen for this study supported Andy, a first grader with deafblindness who was taught in a general education classroom at his neighborhood school located in a suburb of a major metropolitan city. Andy's elementary school served children from pre-school to 5th grade and according to state accountability data, all teachers were fully credentialed to teach. Academic performance indicators suggested that Andy's school was one of the highest performing in the state. Andy's educational team included his mother, father, and professionals from his local school district as well as the county office of education (see Table 1). The majority of team members were from Andy's local school district and included a special educator/instructional support teacher (SE), speech language pathologist (SLP), school psychologist, general educator (GE), instructional aide, administrator, and inclusion specialist. Professionals employed by the county office included a teacher of students who are visually impaired (TVI), a teacher of the deaf/hard of hearing (TDHH), an occupational therapist, a physical therapist, and an assistive technology specialist. This case was bounded to the collaborative practice of five professionals, the SE, GE, SLP, TVI, and TDHH. This subset of professionals was chosen for two reasons: (a) all were licensed teachers who had never taught a child with deafblindness before Andy, and (b) each of these team members were required to provide consultation services to each other as per his individualized education plan. Thus, these five professionals were required to engage in the kinds of practice that may lead to learning about deafblindness.

Table 1. Professional profiles of Andy's team: employer and years supporting Andy at the start of the school year.

Data Collection

Multiple sources of evidence were collected to converge and characterize the practice of these five professionals and create a triangulation of evidence of their learning across the school year (Yin, 2018). I focused analysis specifically on how these professionals engaged in collaborative practices that led to learning over time because Wenger's (1998) contended that learning is the history of practice. Data sources included: (a) observational data of interactions, (b) interviews with all of Andy's team members, (c) review of relevant school, classroom, and child-specific documents, and (d) artifacts of collaboration, including teachers' e-mails, and notes. Data collection began at the start of the school year as these five professionals reconnected with each other after their summer vacation to discuss upcoming goals and plans. The first phase of data collection lasted 3 months and entailed consistent contact with the participants via interviews, observations, phone conversations, and e-mail exchanges. After, an initial analysis of the data identified salient issues related to the participants' learning together, a second phase of data collection began that lasted ~3 months. During this time, the processes of data collection and analysis overlapped, which improved the efficiency and efficacy of both activities. Data collection concluded when the themes found during analysis of the data were repeating instead of extending. For example, in the second phase of data collection, the SE and SLP were interviewed and asked specifically about how their collaboration led to learning given what was found in the earlier phase of data collection.

Analysis

Data analysis began in October with careful organization and referencing of the data sources. All data were organized, referenced, and analyzed using HyperRESEARCH version 2.7, software for qualitative analysis. Early stages of analysis included an iterative process of coding and writing memos that clarified the decisions made when classifying and coding the data. These memos were brief documents about aspects of the data set and included insights, questions, concerns, emerging thoughts or striking events (Miles et al., 2014). Wenger's characteristics of a CoP that lead to learning: (a) evolving forms of mutual engagement, (b) understanding and adjusting enterprise, and (c) developing repertoire, styles, and discourses, were used to make fruitful passes through the large data set and defined segments that led to further in-depth analysis. For example, the first round of coding helped to identify whom among the participants were engaging in collaborative practice and what specifically that collaborative practice looked like over time. Following MacQueen's et al. (1998) stages for coding, the second round of coding relied on emic categories (i.e., categories defined by the words of the participants), which distinguished the voice of the participants from my own. The utility of the coding schemes created in this stage were evaluated by writing reflective memos and measuring the intercoder agreement on selected texts. For example, the second round of coding helped to identify how the collaborative practice of certain participants led to learning about deafblindness. A graduate student in the field of special education served as the peer coder. Our coding was compared for over 25% of the transcripts analyzed. These activities were useful in identifying weakly defined and/or ineffective codes. Reliability was measured by dividing the total number of coding agreements by total number of agreements added to the total number of disagreements. Intercoder agreement of the selection of transcripts was measured at 93%.

Trustworthiness

The strategies of data triangulation, feedback, and member checks to deal with validity threats were used with the aim to increase the integrity of the study's findings. A critical part of data triangulation was the act of writing memos periodically in an analytic journal that explicitly detailed decisions, justified them, and clarified the analytic process. Soliciting feedback from other stakeholders, researchers, and knowledgeable others was another strategy used to guard against validity threats. Informal member checks were collected during interviews by summarizing findings for participants for them to see if the summary was accurate. During observations, the professionals on Andy's team were asked if initial hunches or perspectives on relevant issues were similar to their own. For example, after I observed a quick, collaborative exchange between the SE and SLP that reflected all three aspects of Wenger's CoP framework, I asked them if this kind of informal discussion was common to their everyday practice or a new practice in their repertoire. Lastly, I conducted three formal member checks with the SE, who organized and supervised most of the consultation time on Andy's team after the early stages of analysis.

Results

Wenger's (1998) conceptualization of CoP provided a useful organization for understanding how collaborative practice can lead to learning. Wenger stated that if professionals are learning through their practice with each other, then we would expect three processes to be evident: (a) evolving forms of mutual engagement, (b) understanding and adjusting their enterprise, and (c) developing of repertoires, styles, and discourses. These three processes will be used to organize the results and identify teacher learning within collaborative practices over time. In general, the strongest evidence of learning was found in the professional and collaborative practice of the SE and SLP and the weakest evidence of learning was found in the fragmented practice of the TVI and TDHH.

Evolving Forms of Mutual Engagement

Wenger (1998) stated that in order for people to learn through the process of practice, they need to discover how to interact with each other and develop through mutual relationships. This includes figuring out who is involved, what they know, and how they help or hinder the work of the team. For these five professionals, there was a clear boundary between those who engaged with each other in meaningful ways and those who did not. The three professionals who had mutual engagement that developed throughout the year were the GE, SE, and SLP.

At the time of data collection, Andy was a first grader and participating in his third year at Lake Nevis Elementary (LNE). In the 2 years prior, he was a student in the preschool and kindergarten classes on campus. The SE and SLP supported his transition from preschool to kindergarten and then his subsequent transition to first-grade. The GE was new to Andy's team at the start of the school year, but had a history of working with the SE and SLP. Thus, the GE, SE, and SLP had a history of practice to draw from to learn about Andy and his deafblindness. When asked about how they learned through their practice, the SLP stated in an interview:

One thing I'd like to add is that when we're working together, we're looking to learn from each other. “What experiences did you have with any student?” It's not just members of Andy's team, “What experiences did you have this week? Was it any different from the week before? Was it something we could tap into? Was it something that was fleeting?” So, we're always looking to learn something new and share it, at least this team. I can't say it's always been that way with other teams I've worked with in the past.

It was clear that the LNE professionals had a broader history of learning from each other and were empowered to ask each other for support. They were committed to working with each other, improving their practice, and doing their best for their students. Their time spent in collaborative practice far exceeded what was defined in Andy's IEP. In an interview, the administrator at LNE discussed why she felt that the SE, SLP, and GE teachers were so open to learning from each other:

Well, the bottom line is, the reason that they work so well together is, that just about everybody I've hired, and I've hired just about the entire special education department in this district, is hired with the understanding and the philosophy that we serve all kids. So I don't have hardly anyone in the district who doesn't understand that when they come in. There are lots of special [education] people who consider themselves to be single disability or single activity kinds of folks, you know, “I only do learning disabled kids,” or “I only do this,” or “I only do that,” or “That's what I do,” and in a small district serving with the vision from the school board down to the superintendent to everybody, our vision and our mission is that we're going to serve all of our kids, we're going to offer that to families.

In contrast to these three professionals of LNE, the TVI, and TDHH were employed by the county and did not have the same history working together or with the others at LNE. When the TVI and TDHH were asked about their evolving mutual engagement, they discussed brief consultations, one-off meetings which was in stark contrast to the ongoing informal practice of the other professionals. For example, when the TDHH was asked in an interview about how she has learned from others she replied,

So, when I first had him last year, I read the report to learn more about what he had. And I actually, to talk about collaboration, I actually consulted with, you know he also has a TVI. I believe [the TVI services are] on a consult level as well. And they're from our office, so I knew them. So I did talk with his VI teacher last year to clarify, you know, have her explain to me what his issues were. And then again, at the IEP meeting, it was interesting I got to hear her report and hear her recommendations.

One factor that contributed to the TVI and TDHH's history of limited engagement was the limited time they had to consult. As per Andy's IEP, the TDHH provided 30 min of consultation to the team a month. She stated that she would go over her allotted time if necessary but did not during the academic year of this study. In an interview, Andy's mother noted that the limited services of the TDHH presented some challenges:

And that's probably why not having taken the time to get to know this other gal, [Andy's DHH] you know, we had another—a guy—what was his name?—[Andy's Previous DHH], for a while. And, yeah, and I don't know, it was—it's been one of those things where I feel like that is one area that I wish there was some more time spent at it. I feel like the time that the person has is so limited to just kind of checking the [hearing aids], or, you know, just little quick ins and outs, that's it hard for them: (a) to get to know Andy, and then (b) to just really have any other recommendations.

The TVI had just started serving Andy—although she had worked with him for a short time when he was 3 years old. As per the IEP the TVI was to provide Andy with 45 min of combined consultation and direct services each week. At the start of the year she was unable to coordinate her schedule so that she could meet with other team members. For the first 2 months, as evidenced by multiple observations and interview data, the TVI was not providing direct services to Andy or consultation to his team. After reworking her schedule, she would come every other Friday to pull Andy out of his class for a half-hour of instruction. In an interview the TVI stated, “The biggest frustration is that time doesn't allow me to–I'd love to meet with his classroom teacher, but I don't know when I'd do that.” As the year progressed, the TVI fell into a pattern of providing only 30 min of direct services to Andy every other week with very limited consultation with the SE lasting only a few minutes before or after teaching Andy.

Understanding and Adjusting Enterprise

Wenger (1998) stated that members of a CoP learn from each other through a process of negotiating the meaning of their work and aligning themselves with it. In addition, they must learn to become accountable to the work of the group and hold others accountable to it. They may struggle to define their work and resolve conflicting interpretations of their teaching. It was important for Andy's team to understand their work as teachers of a child with deafblindness because all members felt that they lacked specific expertise or experience in educating students with deafblindness and they were taking a learn-as-you-go approach. Again, a clear boundary emerged from analysis between the LNE professionals (i.e., the GE, SE, and SLP) and the county professionals (TVI and TDHH). It was clear the LNE professionals, despite having limited specific knowledge or practice in deafblindness education, relied on each other to learn how to best educate Andy. For example, when I asked if Andy was representative of students she had taught at LNE, the SLP replied,

I would say Andy, with his needs, he is more of an outlier of the standard services that are provided by a school speech and language therapist. A lot of my kids are verbal. I only have one other student who is non-verbal and also wheelchair access. The other majority of my kids I work with articulation therapy and language therapy. We're working on using language in an efficient and effective way. To work with Andy is to draw away from that expertise and focus in on a very specialized area, for him.

In the absence of formal training in educating children with deafblindness, The SLP noted that her work with the SE has been important in developing her practice:

In writing his goals for this last IEP we had in the spring, both the SE and I were like “Oh, goodness, where do we want to take him?” And we had been to the [conference in deafblindness], I guess in the winter of last year, and came away with some good ideas and thought “Okay, we have some snippets of ideas of where we want Andy to go,” based on just stories and stories we'd heard from other people. Because Andy is so unique in his needs and it's not something that we've had hands-on training on how to work with him, so just pulling from everywhere.

In interviews, the SE, SLP, and GE noted that when they joined the team they needed to learn from each other in order to effectively understand how to best serve Andy's educational needs. They also noted that they had expertise or knowledge that they were able to contribute immediately, in the absence of knowing about specific approaches to teaching children with deafblindness. They had never taught a student like Andy before, but they trusted and supported each other professionally to figure it out. Ultimately, they believed that Andy was a student whom they could educate, which in turn provided the foundation for figuring out the parts that they didn't know yet. Throughout the year, these three professionals were observed engaging in many informal discussions, which occurred almost daily. These impromptu discussions, often not lasting more than 5 min, were rich with problem solving and the negotiating of new meaning about Andy's deafblindness.

In contrast, the teachers from the county hesitated to learn from the others on the team. Both the TVI and TDHH stated in interviews that they didn't have enough time to learn about deafblindness or the necessary background to help others learn. When the TDHH was asked about her previous experiences with teaching children with deafblindness she stated,

The biggest thing is I don't have a lot of experience in deafblind and lots of times people—and that's pretty common. A lot of—I would say there are, you know, most the people in deaf education are not trained in deafblind. That's more of a specific field, and a lot of time it is the itinerants who have gone into visual impairment that end up being experts on the deafblind. They started with the blind and visual impaired and then add [expertise in deaf/hard of hearing], not the reverse. You don't see it as much, it does happen. So, we're not really trained in that. So that is a new area for me.

The TVI and TDHH were not observed in problem-solving discussions. Rather than seeing small moments as opportunities for collaborative practice to learn and develop the collective work of the team, they used their time with the other team members to plan procedural matters, such as when they would see Andy next.

Developing Repertoire, Styles, and Discourses

Wenger (1998) stated that the process of learning in CoPs involves the renegotiation of peoples' repertoire and style, including their use of terms, stories, routines. Only two professionals on Andy's team, his SE and SLP, showed evidence of changing discourses and routines because of their collaboration. It is important to note that this change in practice was first sparked by a conference on deafblindness that the SE and SLP attended the previous year which was followed by on-site technical assistance by a local deafblindness agency. The conference included lectures on best-practices and sessions where the SE and SLP could talk with other educators and family members about Andy's program. In an interview, Andy's mother fondly recalled the event:

And then last year, I was so impressed, in February the [organization for the blind] hosts a workshop like on a Saturday, like an all-day thing, … it was just really nice to think that all these people would, you know, take their Saturday off to go to this for one student, and I think it was real beneficial to them cause they got a lot of information out of it, but it was real neat to have them there. And so that was just—that's a good example of just showing kind of the commitment.

The SLP also recalled how the conference helped her:

It was so good. Lots of parents with children who are deafblind, lots of professionals, all sharing things and tools they use for their kids, things they've made themselves and have found successful. Lots of horror stories, “this didn't work for us, maybe you want to try it but it didn't work for us.” It was really a nice group of low key, to the point, “I understand this but we can take this home and try it kind of group.”

Two visits by a deafblind educational specialist that occurred the year before this study were also important in the SE's and SLP's learning. During the site visits, the deafblind specialist interviewed the teachers and parents, observed Andy's program, and then met with several team members at the end of the day to discuss his findings and recommendations. Several members of the team noted that these experiences were critical in confirming that they were doing a good job educating Andy. The SLP discussed how the experience brought her and the team confidence and pride in their practice.

He has come and has helped us work with Andy and he is just so complimentary in saying, “Everything you're doing is great, I've never seen a student with Andy's needs included as he is in his program” and it just makes us feel good because, not that we don't know what we're doing but we're not sure that what we're doing is right. But Andy's team really works together, which I think is what the [specialist] said, “Wow, this is really good; this is a good place for Andy to be.” So, even though none of us are experts in deafblind students, we know special education, and that's Andy.

The support from the deafblind educational specialist helped the team to reflect back on their practice, which in turn, shaped their identity as professionals of a child with deafblindness and encouraged them to engage with deafblind educational resources and strategies. Observations and emails revealed how the discourse and practice between the SE and SLP had changed because of these deafblind educational resources and support from the specialist who reassured them that they were not just doing “basic good practice, with everyone doing their jobs conscientiously and really trying to work as a team,” but “outstanding, unusually good practice.” The specialist's remarks reaffirmed to the SE and SLP that they could come together in ways that effectively support Andy's educational program.

The GE, TVI, and TDHH were not part of these deafblind specific activities. The GE had access to the information and resources through his informal discussions with the SE and SLP, but there was no evidence of change in his discourse as a result. Instead, he deferred to the SE and SLP to make changes to Andy's educational program and instruction. This deference was also found in the practice of the TVI and TDHH. At the start of the year, the inability of the TVI and TDHH to develop a repertoire with the others was overlooked but as the school year progressed, it increasingly caused tension. The SE, in particular, began to talk about how the TVI and TDHH did not seem to have enough time to get to know Andy's educational needs, even those needs related to their specific expertise of visual and hearing impairment. As a result, two important shifts in collaborative learning occurred. First, the SE and SLP openly discussed how they had lost hope in the abilities of the TVI and TDHH to help them better understand Andy and his deafblindness. Second, the SE and SLP began to primarily interact with each other to discuss how to best meet Andy's educational needs.

In sum, the daily practice of Andy's team members was paramount to how they learned about and met Andy's unique educational needs due to his deafblindness. Wenger's conceptualization of learning through practice, or more specifically the processes of evolving mutual engagement, understanding and adjusting their enterprise, and developing of repertoires, styles, and discourses was useful in showing how some team members learned about deafblindness while others did not. The professionals who had experiences problem-solving and receiving feedback on their work developed a sense that they were able to adequately meet the needs of Andy, and thus developed knowledge and skill in deafblind education through their practice. They began the year with an openness to their work together to teach Andy, which led to a focused desire to learn about deafblindness. In contrast, those who did not consistently or effectively engage with each other or integrate the new knowledge about deafblindness into their discourse were slowly disconnected from the collaborative practice of the team and thus disconnected from opportunities to learn about deafblindness.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to gain a better understanding of how professional collaboration provides a way for school-based teachers and therapists to learn about deafblindness. On Andy's team, analysis from the data of these five professionals using Wenger's (1998) CoP framework showed that professional learning about deafblindness was not tied to a specific role or even expertise, but rather tied to two important aspects of professionals practice: (a) an openness to educate all learners, and (b) a commitment to learn and implement strategies of educating a child with deafblindness. To this end, the findings from this study can inform how to support professional collaboration, especially on teams with limited expertise or knowledge in deafblindness.

An Openness to Educate All

The SLP and SE understood their roles as team members of a child with deafblindness because they held the broad viewpoint that it was their job to educate all children in their district, regardless of their needs or disability categories. They were quick to note that they did not have expertise in deafblindness, but also acknowledged a willingness to learn and try new instructional strategies because of the support they received from each other. They expected that their practice for teaching all students would always encompass learning, which created an expectation that the teachers would support each other and align themselves to each other's practice. The GE had the same philosophy toward educating all children with special needs because of his previous practice with another team supporting a child with multiple disabilities in his classroom, and his history working and learning with the SE and SLP.

In contrast, the TDHH and TVI claimed they were open to learning about Andy, despite their reservations of how unique he was compared to other children on their caseload, but even in their limited interactions with other team members they failed to show this same willingness to figure out how to best meet Andy's educational needs. Consequently, as the year progressed, the TVI and TDHH were engaged less and less by the other team members and were not given access to collaborative learning opportunities. What was the key difference between the three LNE and two county professionals that led to learning? The LNE professionals were willing to engage with each other and have discussions that allowed them to figure out how to best meet Andy's educational needs. In contrast, the TVI and TDHH, were overly focused on their disability-specific roles which limited their opportunity to learn and integrate new approaches (Giangreco et al., 1999). Perhaps if they saw the opportunity of educating Andy to extend their knowledge and skill in teaching a broad range of learners with multiple impairments, and not solely those learners with primarily visual or hearing impairments, they would have been more valued on the team and have had greater access to professional collaboration.

One solution to this problem might be to help professionals, especially those with disability-specific identities, to understand the importance of looking at the intersectionality among their expertise and the other disabilities of the children they educate. Although it is important for these specialists to leverage their expertise, there is much to be learned from the open and broad “we educate all children” approach of the LNE professionals. The LNE professionals communicated frequently, sought out information to bring back with the team, and were extremely positive about their shared commitment to learn from each other. This finding aligns with research on learning in work-based teams in business that has found that team success is predicted by how members communicate and not necessarily individual traits such as their expertise or skills (Kim et al., 2012; de Montjoye et al., 2014; Pentland, 2014). When professionals are energetic in their work with each other and clearly show a shared commitment to the creative practice, they are more likely to be successful.

In addition, it is critical for professionals who support learners with deafblindness to carefully consider if they have adequate time to engage and learn with their colleagues, especially if their expertise or knowledge in deafblindness is limited. Adequate time for collaboration is needed to integrate work to ensure that the child's multiple needs are being met in a systematic manner that best suits the child and the many professionals on the child's team (Council for Exceptional Children, 2015). For example, Andy's TDHH could have evaluated her 30 min of consultation time after a couple of months of school and asked herself if she was able to engage with other professionals in ways that helped them and herself learn about deafblindness. If professionals are to benefit from their collaborative practice in ways that lead to learning about deafblindness, they need the time and inclination to figure it out, even if that means that they need to think, problem-solve, and act in new ways (Hartmann, 2016; Bruce et al., 2018).

A Focused Commitment to Deafblindness

A critical moment in the learning of the professionals on Andy's team came when they attended a deafblind-focused conference and then were supported by a specialist in deafblindness. The conference provided Andy's SE and SLP with access to other professionals who they learned from through informal social conversations. The deafblind specialist provided the team with deafblind-specific resources that certain team members quickly circulated among themselves. These specific resources taught the SE and SLP about the individual learner characteristics of children with deafblindness and helped to deepen their collaborative practice. The SE and SLP began to talk more about deafblindness needs and instructional strategies as they problem solved how to best teach Andy. This led to changes in their practice with Andy.

Clearly the SLP and SE's access to specific knowledge and resources related to deafblindness was also an important factor in their learning about Andy and his deafblindness. Because the SE and SLP had a strong collaborative practice, and a willingness to learn from each other, these deafblind-specific supports were quickly disseminated, discussed, and integrated into their collaborative practice. What is notable of this integration of deafblind-specific teaching strategies is that it didn't require that Andy be taught by a teacher of deafblindness, but it did necessitate that his professionals receive high-quality support from a specialist and access to other professionals with deafblind experience. Given the shortage of teachers with experience and demonstrated effectiveness in teaching learners with deafblindness, this is perhaps the most hopeful finding from Andy's case. This finding suggests that it is important for teachers, families, and therapists to have opportunities to learn about deafblindness, whether it be through a conference where one can learn from others or through other deafblind-specific agencies. In turn, this finding might also be useful to those organizations who provide deafblind-specific services and supports. When identifying professionals who would benefit from learning about deafblind-specific support, do not solely look at whether the professional has low-incidence or disability specific qualifications, but rather whether the professionals have a commitment to learning from each other from which to build. As with the LNE professionals, this commitment might first manifest broadly, as an openness to teach all learners which then leads to a more focused goal of learning about deafblindness.

Limitations

There were several limitations to this study of professional learning in collaborative practice. First, this study used an existing framework, CoP, as an analytic tool. This evidence-based framework provided a useful structure to early analysis, but it may have led to findings that are confirmatory rather than generate new practices. This risk was mediated, as much as was possible, through triangulating data. Although it is not the goal of a case study findings to be generalized to other contexts, it is also worth noting that this study is of one small group of professionals and these professionals do not represent all of their colleagues who hold similar titles or engage in similar work. The best use of the findings is in advancing theories of professional learning about deafblindness. Lastly, this study occurred over the course of one academic year, and although data from previous years was considered whenever possible, the scope of this study was limited. A prolonged period of study might have led to a richer analysis and different findings.

Conclusion

The collaborative practice of teaching a child with deafblindness provides the school-based professionals in this case study with many opportunities to learn from each other, but it can't be assumed that all professionals will benefit in similar ways. On Andy's team, professionals who maintained a broad view about their work as teachers of all learners were also the ones that most benefited from their collaboration and were more likely to learn about deafblind educational strategies. Their embrace of a process-oriented approach primed them to receive deafblind specific resources and implement strategies provided by other professionals with deafblind expertise. These findings support previous research on teacher collaboration in the context of educating children with multiple and complex disabilities, such as deafblindness (Giangreco et al., 1997, 1999; Hunt et al., 2002, 2003; Ruppar and Gaffney, 2011). The findings also support an approach to developing professional expertise in deafblindness that is both broad and deep. A broad approach embraces teaching all children well, regardless of their labels, etiologies, or identities. A deep approach embraces teaching children with deafblindness well through engaging with deafblind-specific knowledge and instructional strategies. Both approaches necessitate a commitment to collaboration (Parker and Nelson, 2016).

In conclusion, although this research suggests that it is possible for professionals to learn from each other in ways that empower their own understanding and skill in deafblindness education, this high-level collaborative practice is more difficult to engage in than professionals expect it to be. This research relates to effective instructional strategies in deafblind education, how professional collaboration can be improved on large educational teams, and how informal professional development on deafblindness can be used to better meet the needs of learners with deafblindness. This research shows promise for empowering teams as they learn together to develop effective collaborative practice and high-quality educational programs for children with deafblindness.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by University of California at Berkeley. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Ainscow, M., Howes, A., Farrell, P., and Frankham, J. (2003). Making sense of the development of inclusive practices. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 18, 227–242. doi: 10.1080/0885625032000079005

Brownell, M. T., Adams, A., Sindelar, P., Waldron, N., and Vanhover, S. (2006). Learning from collaboration: the role of teacher qualities. Except. Child. 72:169. doi: 10.1177/001440290607200203

Bruce, S. M. (2005). The impact of congenital deafblindness on the struggle to symbolism. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 52, 233–251. doi: 10.1080/10349120500252882

Bruce, S. M., Bashinski, S. M., Covelli, A. J., Bernstein, V., Zatta, M. C., and Briggs, S. (2018). Positive behavior supports for individuals who are deafblind with CHARGE syndrome. J. Vis. Impair. Blind. 112, 497–560. doi: 10.1177/0145482X1811200507

Corn, A. L., and Ferrell, K. A. (2000). External funding for training and research in University programs in visual impairments: 1997-98. J. Vis. Impair. Blind. 94, 372–384. doi: 10.1177/0145482X0009400603

Council for Exceptional Children (2015). What Every Special Educator Must Know: Professional Ethics and Standards. Arlington, VA: CEC.

de Montjoye, Y. A., Stopczynski, A., Shmueli, E., Pentland, A., and Lehmann, S. (2014). The strength of the strongest ties in collaborative problem solving. Sci. Rep. 4:5277. doi: 10.1038/srep05277

Giangreco, M. F., Edelman, S. W., MacFarland, S. Z. C., and Luiselli, T. E. (1997). Attitudes about educational and related service provision for students with deaf-blindness and multiple disabilities. Except. Child. 63, 329–342. doi: 10.1177/001440299706300303

Giangreco, M. F., Edelman, S. W., Nelson, C., Young, M. R., and Kiefer-O'Donnell, R. (1999). Changes in educational team membership for students who are deaf-blind in general education classes. J. Vis. Impair. Blind. 93, 166–173. doi: 10.1177/0145482X9909300305

Goetz, L., and O'Farrell, N. (1999). Connections: Facilitating social supports for students with deaf-blindness in general education classrooms. J. Vis. Impair. Blind. 93, 704–715. doi: 10.1177/0145482X9909301103

Hartmann, E. S. (2016). Understanding the everyday practice of individualized education program team members. J. Educ. Psychol. Consult. 26, 1–24. doi: 10.1080/10474412.2015.1042975

Horn, I. S. (2005). Learning on the job: a situated account of teacher learning in high school mathematics departments. Cogn. Instr. 23, 207–236. doi: 10.1207/s1532690xci2302_2

Horn, I. S. (2007). Fast kids, slow kids, lazy kids: framing the mismatch problem in mathematics teachers' conversations. J. Learn. Sci. 16, 37–79. doi: 10.1207/s15327809jls1601_3

Hunt, P., Soto, G., Maier, J., and Doering, K. (2003). Collaborative teaming to support students at risk and students with severe disabilities in general education classrooms. Except. Child. 69, 315–332. doi: 10.1177/001440290306900304

Hunt, P., Soto, G., Maier, J., Mueller, E., and Goetz, L. (2002). Collaborative teaming to support students with augmentative and alternative communication needs in general education classrooms. AAC 18, 20–35. doi: 10.1080/aac.18.1.20.35

Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (2004). Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act of 2004. 20 U.S.C. § 1401 et seq. Available online at: https://sites.ed.gov/idea/

Janssen, M. J., Riksen-Walraven, J. M., and Van Dijk, J. P. M. (2003). Toward a diagnostic intervention model for fostering harmonious interactions between deaf-blind children and their educators. J. Vis. Impair. Blind. 97, 197–214. doi: 10.1177/0145482X0309700402

Kim, T., McFee, E., Olguin, D. O., Waber, B., and Pentland, A. (2012), Sociometric badges: using sensor technology to capture new forms of collaboration. J. Organ. Behav. 33, 412–427. doi: 10.1002/job.1776

Little, J. W. (2002). Locating learning in teachers' communities of practice: opening up problems of analysis in records of everyday work. Teach. Teacher Educ. 18, 917–946. doi: 10.1016/S0742-051X(02)00052-5

Luckner, J. L., Bruce, S. M., and Ferrell, K. A. (2016). A summary of the communication and literacy evidence-based practices for students who are deaf or hard of hearing, visually impaired, and deafblind. Commun. Disord. Q 37, 225–241. doi: 10.1177/1525740115597507

MacQueen, K. M., McLellan, E., Kay, K., and Milstein, B. (1998). Codebook development for team-based qualitative analysis. Cult. Anthropol. Methods 10, 31–36.

McLetchie, B. A. B., and MacFarland, S. Z. C. (1995). The need for qualified teachers of students who are deaf-blind. J. Vis. Impair. Blind. 89, 244–248. doi: 10.1177/0145482X9508900309

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., and Saldana, J. (2014). Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Parker, A. T., and Nelson, C. (2016). Toward a comprehensive system of personnel development in deafblind education. Am. Ann. Deaf. 161, 486–501. doi: 10.1353/aad.2016.0040

Pentland, A. (2014). Social Physics: How Good Ideas Spread–The Lessons from a New Science. New York, NY: Penguin.

Ruppar, A. L., and Gaffney, J. S. (2011). Individualized education program team decisions: a preliminary study of conversations, negotiations, and power. Res. Pract. Person Severe Disabil. 36, 11–22. doi: 10.2511/rpsd.36.1-2.11

Keywords: dual sensory loss, deafblindness, professional learning, collaboration, communities of practice

Citation: Hartmann ES (2020) From Fragmented Practice to Rich Professional Learning: The Collaborative Work of Teachers of Learners With Deafblindness. Front. Educ. 5:573033. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.573033

Received: 15 June 2020; Accepted: 11 November 2020;

Published: 03 December 2020.

Edited by:

Timothy Scotford Hartshorne, Central Michigan University, United StatesReviewed by:

Andrea Wanka, Heidelberg University of Education, GermanySusan Margaret Bashinski, Missouri Western State University, United States

Copyright © 2020 Hartmann. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Elizabeth S. Hartmann, ZWhhcnRtYW5uQGxhc2VsbC5lZHU=

Elizabeth S. Hartmann

Elizabeth S. Hartmann