- Department for Deafblindness, Institute for Special Needs, University of Education Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Germany

CHARGE Syndrome is a genetic syndrome with a recognized pattern of features, and involves extensive medical and physical challenges. It is recognized as the most common cause of congenital deafblindness. This case study focuses on the development of identity of individuals with CHARGE Syndrome which is of concern to individuals with CHARGE Syndrome, their parents and the various professionals that provide support and service. A review of the literature demonstrates that the vast majority of research regarding CHARGE Syndrome focuses on the medical, developmental, and family structures. However, identity research shifts the paradigm to the individual and their unique personality, which encourages professionals to apply their support or services to the human being rather than the disability. This study introduces a method with which it was possible to collect differentiated data from individuals with CHARGE Syndrome themselves through a guided creation of pictorial collages and a specialized interview technique based on their collages. The methodological approach used in this study included structured interviews embedded within the Collage Life Story Elicitation Technique. The CLET (Collage Life Story Elicitation Technique) is a protocol to support individuals in their efforts to create their own life story. Analysis of the resulting data was viewed according to several theoretical frameworks applied to the core narrations and the resources. This provided different avenues to the construction of meaning that formed an understanding of identity from the voices of individual themselves. This research initiative uses a single case study of a young man: Janosch. It becomes clear that Janosch does not associate his core identity with CHARGE Syndrome but rather from alternate origins of self. Janosch demonstrated through this research process that the relevance of animals and the topic of tolerance take a leading role in the formation of his identity. Furthermore and unexpected, Janosch's participation in the Mangas community serves as a primary source of social and emotional support, forms his construction of “togetherness” and strongly influences his concept of the relevance of family. This is in contrast to the role in which friends often impact these components of ones' own identity. The specialized methodology used in this study demonstrates that individuals with CHARGE Syndrome can be active participants in identity research that realize rich and accurate data.

Introduction and Purpose

This study focused on issues of identify in emerging adults with CHARGE Syndrome. CHARGE Syndrome is a complex genetic syndrome which often results in Deafblindness. When individuals with CHARGE Syndrome do not present with Deafblindness they often benefit from similar approaches in education and habilitation (Brown, 2005). For a clinical diagnosis of the syndrome, three or four majors or two major and three minor features of CHARGE Syndrome must be present (Blake et al., 1998 modified by Davenport et al., 1986). The four major features are coloboma, choanal atresia, cranial nerve anomalies (nerves 1, 7, 9, 10) and the unique characteristic “CHARGE ear” involving physical shape of the outer ear and abnormalities to the midde and inner ear. The seven minor features are congenital heart defect, cleft lip or palate, growth deficiency, TE fistula or esophageal atresia, unique facial features, genital hypoplasia, and upper body hypotonia. Since 2004, a genetical diagnosis in about 2/3 of the cases is possible as one major causative gene—CDH7 on chromosome 8—for CHARGE was identified (Vissers et al., 2004).

Although identity development remains relevant during the entire lifespan (Grob and Jaschinski, 2003), psychosocial theory suggests, identity is primarily formed during the period of adolescence, and emerging adulthood (Grob and Jaschinski, 2003). Therefore, it is understandable that this case study focused on a youth age, 22 years.

The vast majority of research and professional literature related to CHARGE Syndrome focuses on the medical aspects of the syndrome; and the voices of individuals with CHARGE Syndrome are rarely included. The literature is nearly absent of reflections from individuals with CHARGE Syndrome other than from a position on medical and therapeutic aspects of their experience. However, if more was known about these individuals from their perspective as to how they would like to live their lives, we could better judge whether our educational approaches and our programs for individuals and families are appropriate. This study focuses on yielding accurate information to understand young people with CHARGE Syndrome by providing an opportunity for them to give their voice space and provide a means of expression regarding who they are and how they see themselves beyond their diagnosis. Understanding who these individuals are beyond their diagnosis of CHARGE Syndrome could provide new information relavent to the provision of support and intervention. This single case research study entitled: “This Is Me” is an effort to achieve this goal.

Why is the focus of this study specifically on CHARGE Syndrome? First of all, CHARGE Syndrome is one of the most common causes of congenital deafblindness. However, regardless of the presence or severity of dual sensory loss, approaches effective with deafblindness are appropriate to individuals with CHARGE Syndrome (Brown, 2011). Secondly, CHARGE is a syndrome, which means that the individuals with CHARGE share similar characteristics that enable researchers to consider them a distinct group. However, it can also be noted that individuals with CHARGE Syndrome—although there are shared characteristics and attributes—are a hetrogenic group. But at the same time people with CHARGE Syndrome are an extremely heterogenic group. Despite the unique commonalities as well as the variety among individuals with CHARGE Syndrome, the overaching inquiry of this study is: “Do they nevertheless have something in common when referring to their identity development?

It is recognized that individuals with CHARGE Syndrome do present with common behavioral characteristics (Hartshorne, 2011) and often demonstrate autistic-like behaviors described in a behavioral phenotype and an increased level of autistic-like behaviors (Hartshorne et al., 2005). Central to this study is the question, what does all that mean for the development of identity? The concept of identity is not clearly conceptualized in the literacture, but there is a consensus that identity addressing such questions as “Who am I?” Am I the one with autistic-like behavior? Am I the one demonstrating challenging behavior? These essential questions are central in discerning if the common characteristics and attributes of individuals with CHARGE Syndrome are a fundamental factor in identity development. The purpose of this study is gaining new insights into these aspects of identity. With the analysis and presentation of this single case study, some progress can be demonstrated in figuring out the role of this diagnosis to ones' understanding of self. Of course, the limitation of a single case or sample of one coupled with the hetergenous nature of the population, generalizations can not yet be made.

Theoretical Frame

The theoretical framework for the understanding of identity formation and social networks in this research project is based on Bourdieu's Theory of Capital; with the term “capital” referring to resources. According to Ahbe (1997), subjective resource management which is defined as an individual's perception of available and unavailable resources; and the resulting identity work can be readily viewed through the lens of Capital Theory. Bourdieu (1983) differentiates between economic, social, and cultural resources; three primary types of resources that can be transformed into one another. Economic capital refers to material assets that are 'immediately and directly convertible into money and may be institutionalized in the form of ownership rights' (Bourdieu, 1986, p. 242). Economic capital can be any kind of item or possession. According to Keupp et al. (2002) it is a strategic resource that can be leveraged to increase the likelihood of accumulating additional resources (ibid.), which are more closely tied to the process of everyday identity formation.

Cultural capital exists in three forms: incorporated, objective, and institutionalized. Incorporated cultural capital consists of attitudes and skills (Bourdieu, 1983). These are embodied tasks that require internalization, which entails time and effort that cannot be delegated to another person and therefore must be invested in personally. Objective personal capital (books, texts, paintings) can be transferred materially, assuming the non-delegable acquisition of incorporated cultural capital. Institutionalized capital (academic titles or the completion of schooling) relieves the bearer of the need to repeatedly prove their incorporated cultural capital (ibid.). Adolescents gain access to cultural and economic capital primarily through their families, as long as both—parent and child—actively participate in the transfer of this capital within the family. The success of this transfer depends on the “value of the available capital within the home” (Bourdieu, 2015, p. 72), as well as on the time available (ibid.). Incorporation requires purposeful contact with adults and the conscious passing down of this capital (Youniss et al., 1994). We can assume that significantly more time is required for the transfer of cultural capital in communication between hearing parents and deaf children. The young man who is the focus of this case study, Janosch, describes his subjective feeling that his family usually has too little time.

Additionally, it should be noted that (the transfer of) culture can be very different for deaf and hearing people. The inner-family conditions for the transfer of cultural capital are quite particular. Within these family situations, the individual's development depends on receiving cultural capital from other sources which requires a high degree of individual effort. According to Keupp et al. (2002) a lack of resources can prevent identity development.

Social capital is the sum total of current and potential resources that come along with belonging to longstanding networks of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual awareness and recognition (Bourdieu, 1983, p. 190f), in other words, the experience of belonging to a group. “The extent of a person's social capital is determined by the breadth of the relationship network the individual can mobilize, as well as the scope of the economic, cultural, and symbolic capital of the other people within that relationship network” (ibid., p. 191). Social capital assumes a “quasi-real existence” through a constant exchange between people in a relationship. There is a danger when a individual does not meet their agreed obligation to another person, since this rarely is solved unilaterally (ibid.). Keupp et al. (2002) states that identity develops through a process of dialogic acknowledgment in social relationships.

Within the theoretical frame, core narrations were used to further identify, analyze and organize findings, and represented a means of triangulation (to be discussed in methodology). Gergen and Gergen (1988) define core narrations as those parts of identity in which the subject on one side tries to ‘get to the point’ and on the other side tries to tell this to others. A well-formed core narration has five characteristics: meaningful end point, focus on relevant events, narrative order of events, occurance of causal links, and boundary signs for beginning and end. Core narrations represent the personal meaning of identity areas.

Method

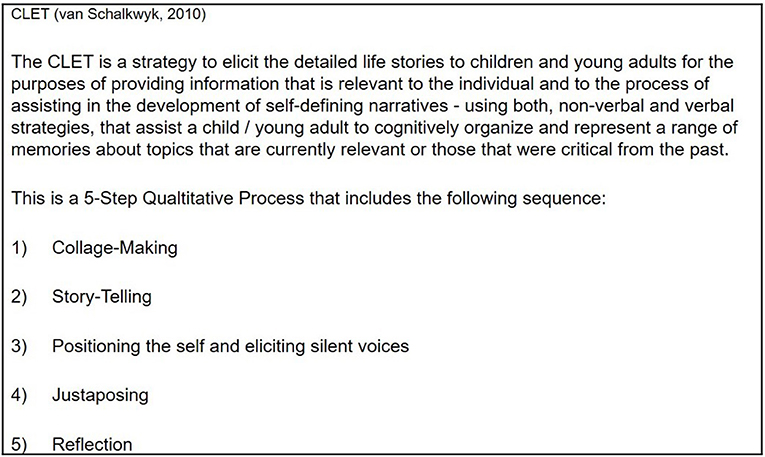

The primary strategy for data collection in this study was the use of the Collage Life Elicitation Technique (CLET) from Schalkwyk, where the subjects tell their own life story through a protocol in which the individual renders their meaningful life experiences (van Schalkwyk, 2010). This structured approach fosters expressing physical, cognitive, and affective changes that result in psychosocial consequences. It identifies the development of dialogical relationships between individuals (Marková, 2003), groups and cultures as well as the dialogue of multiple internal voices (Hermans, 2001). This allows the expression of different I-positions. An individual can develop an alternative point of view or perspective as they are guided to remember their own life story and as a result their story may be reconstructed and coordinated with social expectations and personal goals.

CLET is a tool that serves in collecting life stories and analyzing self-defined memories. This method utilizes scaffolding memories of ones' own life story and helps to overcome typical obstacles in autobiographical memories and in narratives of life stories (Raggatt, 2006). One of the primary vehicles to stimulate memories within the CLET is the use of graphic representation. The reason for the use of pictures or text fragments is to have additional sources and modiality other than the dialogue-based conversation of an individual's life story. This seemed to be very suitable for this subject with CHARGE Syndrome since pictures or text fragments are a visual-based system and a sustainable form of expression (van Schalkwyk, 2010). Creating a collage is seen as a valid social action, a representation or narrative performance in which talking and thinking as well as not conscious acting is implemented. CLET is based on the theory of social constructivism, symbolic interactionsm, and the authority of images; it serves a deeper understanding of symbolism informing the narrative meaning making process (van Schalkwyk, 2010). This means that CLET reflects a post structural view on narrations.

Van Schalkwyk describes five steps for the use of the CLET method. In the first step the participant is producing a collage that represents dominant experiences and events in his or her personal life referring representing the past and the present by the use of pictures/images. The leading question for the participant is “Do these pictures/images represent significant or important experiences in my life so far?” In the following steps the participant reflects upon and comments on the collage with the support of an interviewer who makes sure that the next steps are looked at: Step two is story telling where the participants “(a) tell a story about each picture/image on the collage, (b) describe as best they can what each picture/image means to them, and (c) how it contributed to their development as a person.” (van Schalkwyk, 2010, p. 679) Within step three they are asked to position the self and elicit silent voices: “The participant has to (a) position her or himself on the collage where she or he sees her or himself now (at the time of doing the task); and (b) describe an image she or he could not find but would have liked to add to the collage.” (van Schalkwyk, 2010, p. 679). In step four the participant engages in justaposing the different narrative voices and inter-subjectivities portrayed in the collage. This gives the opportunity to “reflect upon and explore the many I-positions adopted in the dialogue between voices that are part of the outside or the inside world of the dialogical self” (van Schalkwyk, 2010, p. 679–670). Van Schalkwyk called the last step reflection and means a self-reflection on the process of making the collage. This provides a space in which a sense of coherence amongst many I-positions can be created. Van Schalkwyk describes different possibilities of instruction for the interview based on the CLET techniques, also referring a written or spoken access.

After the subject made a collage, an interview was conducted and transcribed. As a result, a three-step analysis was conducted that included the following:

(1) An inventory of detonations and metaphors for the collage was created.

(2) The transcript of the interview was conducted and a summary of the key elements of each collage image was identified.

(3) A story grid for each of the images was created. There were three columns in this story grid. In the first the denotational inventory is noted, in the second it's the metaphor and in the third it's the participant's self-defining memories.

The analysis of CLET data aims to explore the ways in which the collage reflects or represents something of the maker's identity and augments the textual data (narratives) (Franz, 2005; Weber, 2008). Therefore, content analysis of the CLET starts with a process of text reduction before continuing with the identification of important themes and clusters of meaning. The sense-making process (analysis) unfolds in different phases as one organizes the data for an in-depth thematic analysis (Miles and Huberman, 1994) and interpretation of the rich and vivid autobiographical memories in the strategic presentation (performative) of the embodied self in verbal and the observations of non-verbal communication.

As it is common and unavoidable in qualitative research, the process of analyzing the collage and the transcript of the collage is subjective. Van Schalkwyk states—referring reflexivity, trustworthiness and credibility—that “analyzing CLET data has to take into account the complexities of qualitative data collection and analysis, and involves different perspectives to address issues not easily explained. The researcher should therefore adopt a critical reflective position when analyzing CLET protocols, and check and re-check interpretations with the original collage, textual material and literature on the topic. (…) Ideally, a group of collaborators should conduct the analysis in order to ensure investigator triangulation, reduce biases to the minimum, and gain a fuller contextualized picture of the autobiographical memories represented in the CLET. To enhance credibility, triangulation with various data sources and theories (…) facilitate richer and potentially more valid interpretations.” (van Schalkwyk, 2010, p. 685).

Data Collection

This study used a single case study approach, using one subject to conduct an in-depth analysis of the emerging identity of a young man with CHARGE syndrome. Using the CLET technique (see Figure 1), Janosch (name changed to protect confidentiality), was studied for the purposes of gathering critical information to describe his current and past life journey which is refered to as an “identity project.” It must be noted that Janosch was one of 13 individuals between the ages of 15–32 years that participated in a CLET process during the German CHARGE Conference in 2019.

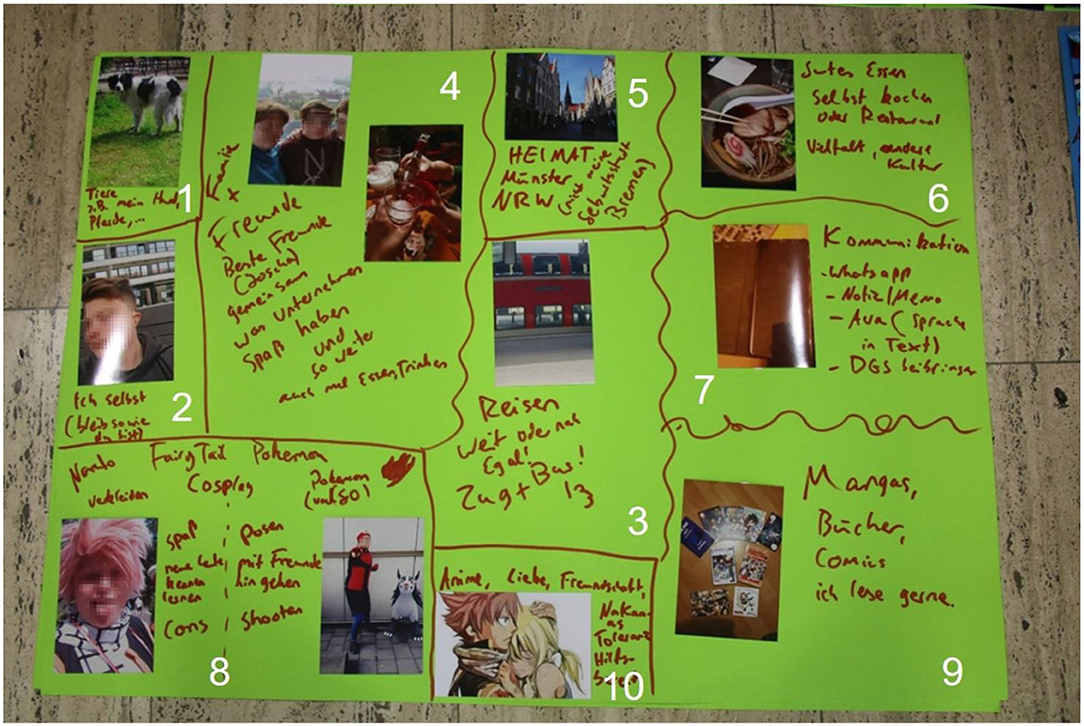

This single case study, Janosch, progressed through the CLET process (see Figure 2) by creating one collage that combines the past and present. He selected 12 pictures that represented significance within his current and past life (see Figure 3). Following the creation of Janosch's collage, he participated in a 50 min interview. This in-depth interview used the services of a sign language interpreter and was video taped with his permission.

Prior to the in-person meeting, Janosch was sent a letter and asked to produce a collage. In the letter an example of a collage was provided which included an explanation of how to submit the content of the pictures. He was asked to produce a collage or if he felt that he needed help with the production, we could do it together when we would meet in-person. Janosch produced the collage on his own in advance of the meeting and indicated that we can proceed with the next step when we meet in-person. An interview was conducted during this in-person meeting during a German CHARGE Family Conference. The research protocol for step two of the CLET included a story-telling protocol that posed the following questions: Why did you chose this picture for your collage?; What does it mean to you?; and How did it contribute to the person you are today?. Although the CLET process would include a second step which would be Positioning the Self and Eliciting Silent Voices, however, it was determined that the energy and depth that focuses on personal topics for long periods of time, this step would be inappropriate. However, the thoughtful work that Janosch put into the creation of his expanded collage and the focused attention he exhibited during the interview, the researcher was satisfied with the outcome.

Therefore, Step four Justaposing, involved the subject (a) chosing two pictures from his collage which have a similar meaning, this may be positive or negative; and (b) chosing one picture with a contradictionary meaning—answering the questions: What are the similarities?, What are the differences? and Why do you find these similar or different? Step Five Reflection, had Janosch thinkg about the process of collage-making and respond to the questions: How was the experience? What were your feelings? What were your thoughts? How did this experience influence you? and Is there anything you would like to say or something you would like to add to your collage?

The data collection phase of this study involved creating a collage and a semi-structured interview process. The interview was transcribed according to the rules of semantic transcription which structures methodical decisions within the transcription process (Dresing and Pehl, 2018). Following the data collecton phase of this research, a story map and a story grid was created as the primary vehicle of the data analysis process. The final phase data analysis was viewing the subject's social resources and networks to example the process of identity forming (Keupp et al., 2002). In order to analyze the core narratives the lead questions included: Which resources relevant to identity forming are derived from Janosch's social network? and How does Janosch's abilities to act in social networks position him?

Analysis Process

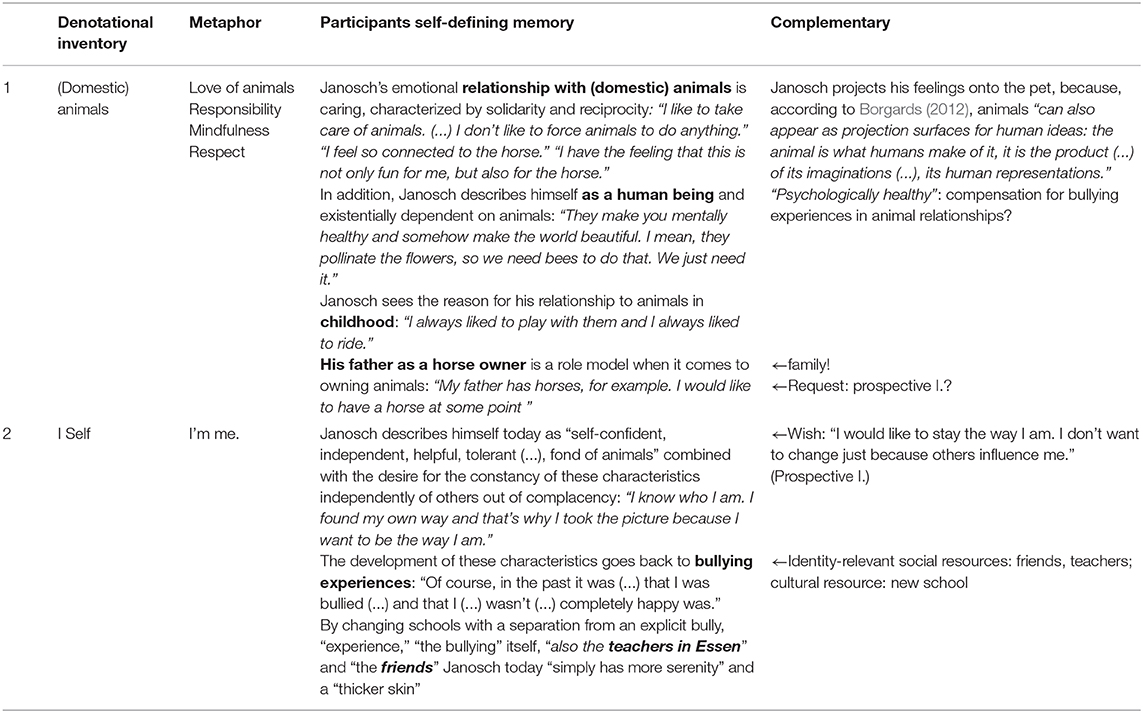

The analysis of the data gathered from the CLET technique involved three steps: First, the collage was analyzed for its role as an inventor of meaning and metaphors, thereby representing a type of transcript of the collage. For every picture or text fragment, an inventor of meaning, connotations or metaphors was implemented. A focus on the contextual clues reflected in the symbolic menaing as well as the manner in which the pictures were arranged. Secondly, an analysis of the narrations was completed with a story map with a focus on key elements like time, location and setting. The analysis used a comparision of on similar meanings, symbolic messages, and methaphors of the narrations. These were further analyzed according to connections between persons and things from past and present. The third step in the data analysis process was the creation of a story grid. The story grid is a four-column table in which meanings, metaphors, self-defined memories, and additional information. It should be noted that these data sets were used within the triangulation process. A denotational inventory was used to further develop the central themes resulting from the analyses (Table 1).

To achieve content validity, the study results were reviewed by the lead researcher, and two students of special education with a focus on deafblindness. Each step in the research process involved these three collaborators. Within this process, the theory of Keupp's Theory (2002) became more and more relevant and was used in the final analyzation process for additional clarity. To identify the core narrations, each member of the research team completed a further content analysis of the transripts and identified content that met the five characteristics of core narrations mentioned above. The researchers conducted a final discussion for the purposes of coming to consensus on the core narrations to be identified. Any core narration in which the members of the research team could not reach consensus, those narrations were removed.

Focus: Single Case Study Janosch

As the purpose was not to generalize any findings to a larger population and as the data of every collage and interview was very individualized, this initiative was conducted as a single case study, involving a 23 year old man, named Janosch, who graduated from high school and finished a year of voluntary social service. Janosch was chosen using a non-probability purposive sampling strategy (Onwuegbuzie and Leech, 2007) and represented the participant who best fit the criteria of the project. This form of sampling specifically aimed at “identifying participants who could provide rich and vivid stories and who had adequate and in-depth understanding of the topic under investigation.” (van Schalkwyk, 2010, p. 686)

At the beginning of the study and during the collage-making process, Janosch wanted to begin a training to become an educator. He left home early and attended a boarding school. He defines himself as Deaf and uses visual German sign language.

Limitations

There are several limitations of the study that begin with the fact that this is a single case, and the subject belongs to a highly diverse and heterogenous population. Therefore, generalization of findings is not appropriate. Lastly, the use of a sign language interpretor and the use of a video recorder may have had effects on the content of the interview.

Results

Janosch's Collage shows the 10 most important past and presents aspects of his life.

Resources

As described in the methodology, three steps of analysis were made to identify themes. These themes were further validated through a process of triangulaton involving the three collaborators. As a result the following core narrations and resources were identifiedand linked to each other (Keupp et al., 2002).

Social Resource: Friends

With a focus on resources, it becomes apparent, that one of his social resources are friends, which is connected to nearly every picture of the collage. Janosch uses the incorporated cultural capital written language, to virtually maintain contact with friends and to be able to meet them in real life to engage in joint creative writing of anime-stories.

“My best friend for example (…), no matter how close or far he is living, I can ask him if we can meet. We can visit each other, we can sent whats app. We also write stories in a whats app group.” (I2, line 15).

Janosch uses the objectified cultural capital of books or mangas for collaborative creative writing acitivies and attends manga conventions with his friends. Reading the books in contrast to role-play at conventions seems to be an alternative method of exercising his imagination and connections with his network by designing anime characters with specific characteristics.

“Well, I can dream stories. I can imagine to be in the story and then I can write stories on my own—in these roleplay-whatsapp-groups (…) and this is all connected.” (I3, line 16).

“Cosplay1 is important to me, but even more important is reading the stories, because in reading them there are so many possibilities. Cosplay, there is not so much about Cosplay. (…) Well, there are stories I really like, but I would never dress up like that… That's not me.” (I3, line 24).

Another aspect of the social resource of friends is traveling: Janosch emphasized that he loves traveling and that he can travel free due to his sensory disability. This makes it possible for him to maintain contact with his friends without the assistance of others. This becomes even more important while considering the special value that Janosch puts on friendships. It appears that Janosch's skills in traveling have a critical influence on his status among his social network of friends. He positions himself as a capable traveler independently.

Use of Social Networks: Friends for Developing Identity

By considering the use of the social network as important to the development of identity, it becomes apparent that attendance at conventions are extremely important to Janosch and therefore, hold special status in his narrations.

“We visit so called conventions. This means: You do not just read books, but you also dress up and go to meetings, where people represent different characters.” (I3, line 2).

In these dresses Janosch experiments with roles to overcome his shyness, which seems not to fit into his narrations because he describes himself as “confident, independent, helpful, tolerant (…), and fond of animals” (I1, line 10). These incongurencies between his goal of overcoming his shyness yet his prospective work on identity is demonstrated as he describes himself as confident.

“Well, ususally I am always Janosch, but I can also… Well, do that. I am as Janosch sometimes a little shy and not able to speak to strangers and have to overcome myself, but when I am dressed up, then it is possible. Then I go to them and say: ‘Come, would you like to make a picture¿ I don't know why it is that way, but it has something to do with the paneling.” (I3, line 10).

At another part of the interview, he describes himself contrary: “We (Janosch and his best friend) have changed together quiet a lot. He was very introvert in the beginning and I helped him to open up a little bit and he helped me to change myself.” (I1, line 54).

“If somebody has a problem I tend to interfere and help. My best friend sometimes tells me: ‘No, wait, you can't always do that.’ And due to him I learned to withdraw a little bit.”(ibid).

The frame in these two narrations is different: In the first quotation, Janosch refers to himself as Deaf in the hearing world or in contact with hearing people. In the second quotation, he refers to himself as a friend in contact with people which he does not provide a category such as deaf or hearing. These characteristics differ in these two narrations which can be a hint for part-identities (Keupp et al., 2002). Janosch as a friend and Janosch as a Deaf.

As Janosch's identity continues to evolve, there appears to be tensions that are demonstrated by current inconsistency in his themes of the past. Based on Keupp et al. (2002), Janosch's recurring narrations may be an indication that Janosch is generating new actions and concepts of identity or actions that assist in identity development. Being dissatisfied with his shyness in the hearing world—especially in connection with the rejection of him as a Deaf person—can be assumed to be recurring and leads him to strive toward more to extrovert attributes as a current identity project. In addition, a remanent of Janosch's past in which he was bullied by peers, is a factor to be viewed closer.

Janosch successfully incorporates cultural capital within his assuming the features and characteristics of anime- or manga characters. He appears to be filtering characteristics of anime or manga characters as an avenue to relate to others and to generate new friendships:

“Well, with the animebooks and films… I also experience things like friendship, love and… I experience also characteristics like helpfulness, tolerance and then I develop through that stable friendships and this is really important to me.” (I3, line 38).

This is possible as the characters in animes give Janosch an idea of what friendship is (see Table 2).

“I would have to say that through these books, I have changed my understanding (of friendship). When I was at school in D., for example, because I was often bullied, I became more cautious and was scared. I tried to become stronger and to change myself and to help others, rather than letting myself be bullied” (I3, line 40). In this conception of friendship, in which heroes Naruto and Fairy Tail are role models, the community of individuals and mutual support in the face of challenges plays a very big role. “Naruto, for example, or Fairy Tail, with fantasy and dragons and stuff, um… they are a kind of guild. That's a group with special abilities who are given tasks by the king or whoever. They get these tasks, like killing some monster or something, or to save someone or whatever. And then they do it, but they do it TOGETHER. They don't fight alone; they fight together. And when that happens… they support each other in fighting against the dangers of the world. They do it together and are able to get it done.” (I3, line 42).

Janosch is able to evaluate his understanding of friendship not only through reading, and accepting or refuting some of the information, but also, through sharing stories with his friends via WhatsApp. He is able to experiment with various identities through using disguises at conventions. The social network, through a differentiated filtering of the various lifestyles available through mass media, takes on the role of a relevant social structure (cf. Keupp et al., 2002). This process of negotiation is very conscious and active, not implicit. Janosch describes further that he is able to make new friends at conventions. That is how he describes a closed circle of generated social resources. At conventions, Janosch has access to hearing people who then become his friends. “This hobby has allowed me to meet lots of people and to make friends.” (I3, line 2).

Janosch experiences tolerance at conventions and tolerance (see social resources: hearing people) is a quality with which he identifies and which, among others, he seeks to continue.

“I am… tolerant” (I3, line 10).

“I know who I am. I have made my own way, and that's why I put that picture there, because I want to be the person I am.” (I1, line 8).

Once again, Janosch considers himself a tolerant person, which is an indication of his identity project which may be defined as the process of identity development and evoluation. The project is motivated by the tension between the contradictory self-image perspectives as a(n) (in)tolerant person: “Janosch in the hearing Cosplay community” and “Janosch in relation to the general hearing world.”

In addition to attending conventions, Janosch talks about other activities he participates in with his social network of friends: “We love to go into town and walk around, to go out to eat in the evening or to see a movie, or maybe go out for a drink.” (I1, line 60).

Janosch expands on the topic of going out to eat. “The food is called ramen; a kind of noodle soup. I love to eat that sitting together with my friends. Eating just by myself is not so fun.” (I1, line 92).

Within his hearing family, Janosch is fairly isolated during family activities due primarily to issues of communication, this exclusion may result in a feeling of being a less capable person. That's why activities with friends are so important. In those situations, he can actively and personally participate from a more capable position. His social network of friends compensates for a lack of communication ability and opens up a range of possibilities for identity development. When discussing his friends, Janosch emphasizes the aspect of friendship that allows for development within a group and profiting from the mutual support (cf. I1, line 54). His social network of friends provides a range of options for his personal characteristics and his understanding of friendship. “So, I think that through my friends I have learned about qualities of myself and my identity and my ideas about what a friendship should be.” (I3, line 40).

Janosch's relationship with his best friend J. means he has a significant other and the two boys benefit from one another. Janosch's identity project of becoming a more extroverted person can be put into practice through his interactions with J.

Social Resource: Hearing People

Janosch uses the incorporated culture capital of written language to communicate with hearing people. “I always use my smartphone when hearing people can't understand me. I write out a message and show it to them…and now there's an AVA app [author's note: app which creates live subtitles] for that.” (I2, line 11).

In general, Janosch's relationship with hearing people is one-sided and difficult because hearing people often aren't interested in investing the time needed to communicate with him as a deaf person. On the other hand, he must invest some effort to translate their messages. Janosch experiences rejection and disdain from others because of his deafness, which according to Keupp et al. (2002) can be viewed as marginalization; the withholding of the resource of recognition which would otherwise come from his social network. This becomes all the more apparent when he encounters hearing people at conventions, who are different from most other hearing people because they take time to communicate with him. Viewed from another angle, Janosch feels momentarily tolerated and valued by the hearing people at conventions.

“There are some people who are more Zen and with them I get the feeling that they are more tolerant. They just think, “Oh, God, he's deaf,” and then they take more time. They write things down and try to communicate. It's like when I take a picture, for example, then I can show it to someone and it just works. Then we get together and take pictures. It's just really nice. It's just easier.” (I3, line 12).

As already mentioned, Janosch describes himself as a “tolerant” person. This stands in contrast to the rejection he has experienced himself as a deaf person and fits with his own personal narrative of tolerance from certain hearing people. Presumably, in his own personal dealings, Janosch distances himself from the rejection he has experienced. This represents a future-oriented process of reflection in the sense of prospective identity work that is driven by a lack of resources. The related identity project is: Janosch as a tolerant person. Trying on new identities through experiments with roles based on anime and manga and trying on costumes at conventions aid in the development of this identity project. Additionally, we can see retrospectively how his identity related to tolerance was formed: on the one hand, through his rejection by most hearing people in the past and on the other through his internal narration about being bullied.

Social Resource: Animals

According to Otterstedt (2012) a person's relationship to an animal can change instantaneously: “It is not that the animal has changed, but rather our image of the animal that changes. The animal is perceived increasingly less as a thing, and becomes instead a personality and a subject, one to be accorded sympathy and empathy as a fellow creature.” (Online source without page reference). Borgards (2012) states that animals “can also serve as a projection screen for human ideas: The animal is that which the person makes of it; it is a project […] of his imagination […], his human representations.” (Online source without page reference).

The fact that Janosch included the animals in his collage means that they are part of Janosch becoming who he is today and that they are an important part of his identity process. The family pets that Janosch talks about can be viewed as critical relationships that have an important role in his identity project. Since animals do not communicate through language, Janosch supplies their intentions through reflecting on his own experiences in the hearing world. Connections here can only be implied. Janosch's emotional relationship with the animals is one of care-giving, full of closeness and mutual enjoyment.

“Animals are important to me. I like taking care of animals. I like caring for them and not trying to make them do anything they don't want to.” (I1, line 2).

“I feel so close to the horse.” (I1, line 4).

“I get the feeling that this isn't just fun for me, but for the horse also.”(ibid.).

Because the animal can be seen as a representation of Janosch himself, we can assume that we will find evidence of mutuality and caring in his relationships between animals and people. This is especially true in the case of friendships. Friends grow together and benefit from mutual support. As already mentioned above Jansoch says of his best friend J.:

“We have really changed each other a lot. He was quite introverted when we first met and I have helped him become more open and he has helped me to change, as well. (I1, line 54)“When someone is having a problem, I just jump in and try to help and J. sometimes says to me: ‘No, wait, you can't always do that.’ And because of that I have learned to hold myself back a little.” (ibid.).

After bullying experience, Janosch became a more open, helpful person who is dependent on others, whereas before this incident, he was more self-focused and independent. This clearly shows Janosch's reflective abilities and deep analysis of his behavior in relationships, seen here in his contact with animals. This perspective of Janosch's identity work becomes clearer as witnessed in his perceived health and existential dependence on animals.

“Bees pollinate flowers, so we need them. We just need them.” (I1, line 6).

Presumably, Janosch sought emotional refuge in animals during difficult periods like during the time he was bullied. Animals provide unconditional love and closeness, and communication with them is easy. Janosch is aware of his very early relationships with animals as a child.

“I always played with animals, and I always liked to go horseback riding.” (I1, line 4).

That fact that his father has a horse is a role model for Janosch wanting to own animals 1 day.

“My father has horses, for example. I would love to have a horse someday, too.” (I1, line 2).

In conclusion, this complex identity project related to social development helped to develop the following characteristics: attentiveness, caring, communality, equality, dependence.

Social Resource: Family

Janosch's family is hardly ever mentioned during the interview. There aren't any pictures of his family in his collage, which Jansoch explains is because he couldn't find any pictures of his family members. In retrospect, he says he would like to include some. (cf. I1, line 34 et seq.) At one point during the interview, Janosch mentions a girlfriend in connection with discussing anime and love, but there is also no picture of her in the collage. Janosch explains that this is because they are “not yet 100% together” (I3, line 51 et seq.) But they are in love (cf. ibid.). His family is mentioned in his story in ways that are relevant to his identity: in ways they differ from his friends, as a hearing family, as his roots, and in relation to his skills in independent living. Taken all together, a story emerges in which the core of his family was formative in early years and which is still important today. However, today his friends have taken the place of his family in the process of his identity development.

The last section described Janosch's complex identity project. The explicit role played by his father related to this project is greater than the data might indicate. The mention of his father as a role model in his identity development is more an indicator of identification with him than a rejection of his father's role as a horse owner. We can therefore assume that the father does not play a very central role in this identity project, however he does play a supporting role. Regarding group activities, Janosch talks about the importance of both family and friends, as well as group spirit, gathering together and community. His explanation of his friends involves a wish for mutual support in friendships and the stability of friendships. The desire for stability can be explained by his family situation. (I1, lines 34-64). As a deaf person, Janosch experienced loneliness within his family despite his mother's efforts at communication. To a question about the importance of stability in friendships, Janosch answers: “For me it's important that friendships are maintained and not somehow just lost.”

“Otherwise I just feel lonely when I don't have any contact with friends. My family situation is the same way. My family is hearing. Sure, my mom is there, but I am deaf. I never know what's going on in my family. And that's why. I mean, my mother tries to sign for me, but that's not 100%. I still miss a lot anyway, but with my friends I can communicate and that's why I like spending time with them.” (I1, line 42).

Janosch feels quite isolated within his family because of the communication barriers between himself and his family members. His mother has special significance because she learned German sign language to communicate with him. Janosch describes himself within the family as being in a less capable position because actions in the above quote originate with his mother while he portrays himself as rather passive, (having to) accept this situation. In the following quote, Janosch talks about activities with his family that sometimes don't work out. For that reason he would rather fall back on his social network of friends with whom he is in a more capable position in terms of communicating without barriers.

“With my family? Well, yeah, sometimes we eat together, chat about stuff at home, maybe drive somewhere. One time I wanted to drive to Berlin with my mother but the trip fell through. So, I'd rather go with my friends, because Mom usually doesn't have the time.” (I1, line 62).

Actions that produce desired social confirmation are successful with his mother because communication is possible with her, although Janosch admits that signing with her is not always clear. Although it is possible to communicate with other family members through written notes, Janosch hardly mentions this in the section about communication. Presumably, Janosch finds himself in an isolated position in terms of communication. We can assume from his wish for more social interaction with other people that actions and social confirmation are an acceptable way for him to realize coherence. His desire for social exchange is clearly evident in his activities with friends, while these activities all involve a communicative aspect, with the exception of going to the movies together.

“We love to go into town together, to walk around, maybe go out to eat, maybe catch a good movie or go for a drink.” (I1, line 60).

According to Keupp et al. (2002) young people try to foster coherence or consistentcy. In Janosch's case this is impossible within his family because he is deaf and dependent on the efforts of his family members to communicate and make himself understood. Coherence can, however, be found in his circle of friends in which he experiences himself as very capable. Janosch's sense of capacity with his friends, it may be assumed that in his social network he actively avoids communication isolation or barriers to communication, so to not replicate his family experiences of lack of communication. Janosch also talks about his family in the context of home, rootedness, tradition, and familiarity. That being said, Janosch compares the feeling of home he gets in M. to love (cf, I1, line 86), “because he grew up there” (I1, line 86) and feels “a connection” [to the place] (ibid.). In fact, Janosch did not grow up there, but rather in a town nearby.

“So there's this little town outside of M. that is really my home, but that's where my parents got divorced. So, that's where I actually grew up, but I still feel more connected to M., since that's where I went to school and where my friends are.” (I1, line 88).

Janosch's positive feeling of home are more closely tied to friends and school than with family. Instead, Janosch remembers his parents' divorce. One possible explanation that his feeling of home is not closely tied to his parents may be the frequent family visits outside of M. and the fact that while Janosch has left M. behind him, his family remains there, even if in a different family constellation.

I: How often do you see your family?

B: Pretty often. Well, my mom often. And my grandma lives in Bremen. I visit her often.

I: So, you usually visit her?

B: Well, both really. (I1, line 45ff)

Another mention of his family occurs in the context of good food, enjoyment and cultural traditons. Janosch describes very enthusiastically that good food is very important to him. He differentiates between the activity of going out to eat and cooking.

“I do cook sometimes, but I kind of wait and see if I have the time, if I have some other appointment. I do it when I have time to cook.” (I1, line 92) One particular experience during school played a part in his enjoyment of and creativity around food:

“One time I was on a class trip to Rome and ate some noodles and I became really hooked on them.” (I2, line 1).

Janosch attributes his creativity and willingness to try new things in the kitchen to the above-mentioned culinary experience. In part because of the bad food in his school dorm, Janosch is very interested in returning to Italy. When asked what he enjoys cooking, Janosch says:

“Usually something with noodles and egg… noodles with tomato sauce if I want to make something simple. I just throw stuff together… in the school dorm I used to try out lots of spices… One time I was on a class trip to Rome and ate some noodles and I became really hooked on them. Then I went to school and ate the noodles and they had no flavor at all, you know? Of course there are some good noodles to be had in Germany, but in Italy they somehow just tasted better. Typical school dining hall food is usually bad, so I bought myself some noodles and tried on my own to spice them up a bit and I noticed they didn't taste very good either. So, I guess I just need to go back to Rome and ask how they make noodles taste so good.” (I1, line 96 – I2, line 1).

Janosch learned a lot from watching his mother who is a professional cook. Through her he was able to incorporate the cultural capital of cooking which allowed him to become independent and self-reliant in preparing his own food, his enjoyment of food, and desire to become more creative in the kitchen.

I: “How did you learn to cook?” (I2, line 4).

B: “From my mother. My mother is a professional cook. So I helped out a lot. I wanted to become a cook, too. At first, I wanted to be a veterinary assistant but that didn't work out. Now I am training to become a teacher starting this August. That seems to be working out, but if it hadn't, I think I would still like to be a cook.” (I2, line 5).

It is noteworthy here that Janosch had considered following in his mother's steps to become a cook, but chose instead to go his own way. This is common, that young adults break out of the family structure and find their own way in life, orienting themselves instead toward their same-age peers.

Social Network: People With CHARGE

Interestingly, Janosch does not really identify himself with other people with CHARGE, even though he created his collage at the CHARGE conference. There is only one point at which he shares a narrative in which he identifies with the syndrome and other people with CHARGE. Janosch thinks that parents of other people with CHARGE underestimate his independence and autonomy, although he does understand why some parents are very concerned for their children. Even though he has faced some difficult challenges, he sees their concerns as a hindrance to the independence/autonomy that he has worked hard to learn in school:

“Of course, there are some people with CHARGE who can't take the train by themselves because their parents think they won't be able to or they are worried. I can understand that. Sometimes it can be kind of confusing in the train station. You don't always know which way to go. Take the station in Siegen, for example, where it takes a long time to navigate. It took me a long time to become familiar with it, so I don't like that station very much. One time I thought the train was leaving so I started running but it turned out to be a construction zone. So I ended up missing the train which was a bummer. Sometimes in that station I was able to just make the train. Now things are better. I have finally figured out the system and I can do it by myself. (I1, line 26).

It is possible that the deficit-oriented, medically driven research about CHARGE Syndrome is in part responsible for this. However, CHARGE Syndrome does play an important role in Janosch's identity development, as it relates to his close friendship with J, who has CHARGE. As a person in a position of significance, J. is an anchor for Janosch's identity projects. One has the impression that Janosch would not seek to be a member of the CHARGE Syndrome group if he had the choice. However, he has a reflective relationship to belonging to the group. He views the fact that he has CHARGE as limiting his independence but processes this view by reflecting on himself through an independence-enhancing individual perspective. This can be seen as an internal resource that helps make him more capable.

Core Narrations and Friendship: Helpfulness, Independence, Tolerance

Below the core narrations with a consensus between the three collaboratuers are described.

Helpfulness

The desire for the stability of friendships, when viewed through a network perspective, can be seen as an avoidance of the loneliness caused by being a deaf person in a hearing family; and his relationship with his best friend J. is important because of the mutual support it provides. (See: Social Resources: Family; I1, line 54) If we consider support a transactional process, then being willing to help someone out is a necessary characteristic in this process. The mutuality of support is, on the one hand, a combination of the processes of helpfulness and friendship, and on the other, a translation of these processes results in everyday identity work. The following core narrative demonstrates characteristics, actions and their connection to friendship. Both quotes relate to picture #4 of the collage.

“So, for me, both family and friends are important… I just think it's important: that close tie… and it's important to me to maintain my friendships and not let them fall apart. I definitely don't want that.” (I1, line 34).

“The two of us (J. and I) have known each other a really long time and have done lots of stuff together and we've helped each other change quite a bit. He was much more introverted at the beginning and so I helped him open up a bit more and he helped me to change a lot, too. It just works really well… sometimes he tells me he doesn't like it when people jump in and get involved. But, when someone has a problem, I like to get right in and try to help, but J. tells me: “No, wait, you can't always do that. And through knowing him I have learned to hold back a little more.” (I1, line 54).

The meaningful result drawn from this story of mutual support is the importance of valuable friendships. The key occurrence: Janosch the extrovert supports his introverted friend J. in becoming more open to others while at the same time, the more cautious J. helps Janosch learn to hold back from solving other people's problems. Note the order of the narrative: The use of the perfect tense [“he was more introverted” (ibid.)] in a core narrative that is otherwise conveyed in the present tense emphasizes the success of Janosch's support, while the fact that Janosch holds back more is a success of J.'s support. The change from the past to the present can be viewed as a parallel process to the development of their earlier to current selves when viewed as a whole. Establishing causal relationships: Janosch's narrative is a logical expression of the importance of valuable friendships.

Independance

Independence is very important to Janosch and it has already been noted in relation to his social network as a person with CHARGE, that Janosch feel hindered by the concerns of other parents of children with CHARGE in the development of his own independence and autonomy. The quote that was analyzed previously (I1, line 26) depicts a core narrative. Janosch exercises his independence with train travel in ways closely related to his friendships. He would rather take a train trip than miss a chance to see his friends who don't travel. This demonstrates both his capability and readiness in regards to his friendships, as well as the realization of his independence in everyday identity work.

“I just love to travel… sometimes a long ways…by train. Sometimes I have to travel to see my friends and it's no problem, because I can so easily take the train. And I travel for free. I don't have to pay anything. Sometimes my friends say they can't come visit me because they would have to pay. So I just say, well, I've got the ID card that let me ride free, so I'll go. If they don't have money, it's no problem, because I travel free, you know? And I can even take someone with me. I just go pick them up and then they can ride free on my card. It's really practical.” (I1, line 20). “Sometimes it's kind of a pain, but it's fun. What's important to me is getting together with my friends so I don't forget them and they don't forget me.” (I1, line 22).

Janosch describes his desire for independence as a gradual, progressive process over time.

“There was a train from M. to some little town where I wanted to go, so I just went by myself. It was just one stop away, maybe two. It was no problem. Things progressed from there. I just traveled more and more. For example in 2008, I had been in M. and then went to Dortmund for high school, and I already knew how to take the train by myself. It was no problem. So I always took the train to and from D., or sometimes I went to R.n to visit friends.” (I1, line 24).

Train travel is the resource Janosch uses to establish his friendship/social-oriented self. That is how he personally maintains the valuable friendships that are part of his core narrative. One relevant event is represented in the core narrative in I1, line 26. The narrative is constructed through a progressive process of seeking independence, which in turn helps him to develop into a social being.

Tolerance

Tolerance is a personality trait that can be viewed in Janosch's friendships: Janosch describes the tolerance of some hearing people demonstrate due to his deafness (I1, line 12). However, tolerance does relate to friendships, because Janosch and his friends become closer through their shared fan culture (reading anime and writing roleplay stories). In addition, Janosch experiences tolerance not just at anime conventions, but also in the anime stories themselves, and emphasizes their connection to friendship. Janosch concretely establishes strong, valuable friendships through personality traits such as tolerance. “In anime books and movies I experience things like friendships and love… and I also experience traits like helpfulness and tolerance and that's how I form strong friendships and that is realy important to me. All of that is involved in the stuff I do with my friends” (I3, line 38).

Janosch does not directly include tolerance in his core narrative during the interview, but the theme of tolerance does emerge from time to time. One reason for this could be that no probing questions about tolerance were asked during the interview, so when Janosch mentions tolerance it is usually related to his friendships, anime conventions, or his experiences with bullying. Further questioning may help to reveal more about his identity. An additional explanation for this lack of reference to the topic of tolerance could be that Janosch is not able to express this component of his story because it is yet to be completed. One indication of that could be the fact that he did not insert any pictures about tolerance into his collage, as he did for independence (picture #3 on the collage). This analysis has assumed that latter explanation that Janosch has not had sufficient time to process the theme of “tolerance” with the interviewer. This is supported by the fact that tolerance is only episodically mentioned. Janosch's current, tolerant self is a result of his use of an evaluative framework (MacIntyre, 2007) to emphasize the positive as he progresses through his identity development process. Tolerance is another identity project that vascliates between humans and animals which can be based on acceptance. It is worth exploring which relevant experiences were the basis for this reflection and which experiences helped Janosch increase his sense of tolerance through identity work. Clearly relevant here are his experiences of being bullied (I1, line 8; I3, line 40) and the tolerance he experienced with hearing people at conventions (I3, line 12). The tolerance that is reflected within anime stories can be viewed as an event because he “experiences” this in a very special way (ibid.). Beyond those already mentioned, the collage does not offer any further incidents. He knows from his own personal experience how bad intolerance feels and how good tolerance feels, remembering that when he was being bullied, he felt “not entirely happy” (I1, line 8). Given the degree to which this experience played a role in his identity development, we can read his statement about not being “entirely happy” as a euphemism. In contrast to this, Janosch describes the times when, as a deaf person, he was not rejected due to his deafness (I3, line 12), which can be viewed as tolerance. Based on these experiences, he determines that he wants to be a more tolerant person himself. There is a discrepancy in the outcome of his reflective process between his wanting to be more tolerant and the overall tolerance he has experienced. This could be due to the fact that he has not yet realized his identity project or due to a lack of data. There is nothing in the interview to indicate that Janosch might otherwise have thought or acted in an intolerant manner. We can assume that Janosch cannot connect his level of tolerance to one single event, since tolerance is a fundamental charater trait that reveals itself through openness to other people. A focus on relevant events is only partially successful in determining the outcome. We can clearly see in retrospect how important tolerance is to Janosch.

Relevance of Manga Culture: Cultural Perspective

As a deaf person, Janosch's access to spoken language is obviously limited. His langage is German Sign Language that in itself is the natural language of those who are culturally deaf. Because he is able to communicate using Sign language with his friends, he actively initiates opportunities to interact. Of course, the assumption is that many of his friends also communicate through German Sign Language. Unfortunately, It was not possible to observe his membership in the deaf community or his identification as a deaf person from a cultural perspective. However, his own formulation of deafness as a disability is clear (quote: following page):

“I just am the way I am. It's not about CHARGE or deafness. I just am the way I am.” (I1, line 56).

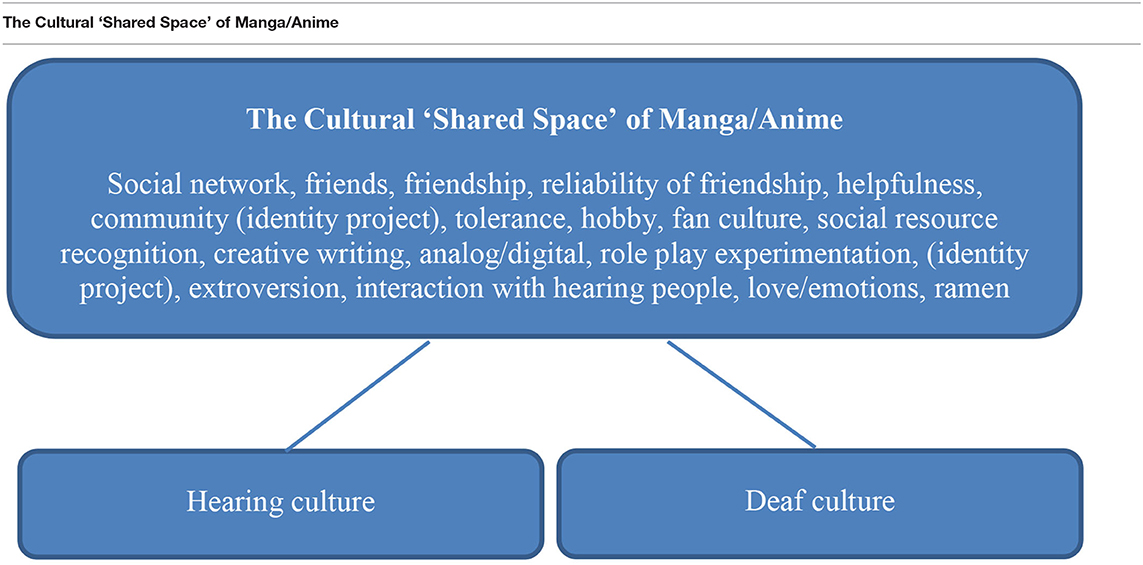

Nevertheless, he experiences his deafness as problematic within his family. However, it appears that Janosch is willing to make the necessary communication with hearing people through the Manga culture as a “shared space” between deaf and hearing people. The following illustration lists all of the identity-related terms used in this article so far, in the context of or related to manga/anime, and places them within this cultural shared space.

These terms are represented as a single theme because they are all located in this “shared space”; they are all connected to manga/anime. This topic is stressed as it also occurred in other cases of this project: From 13 adolescents with CHARGE Syndrome five mentioned the importance of mangas or animes. Yet they are also related to each other in more complex ways. Some terms like “friendship” play a more important role because they were accessible through manga, and require other featured terms like “independence.” Some of them also represent a cycle, like friendship, conventions and acceptance: Through fan culture and with his friends, Janosch gains access to conventions. In the social network of his friends, Janosch finds acceptance. Further relationships become conceivable.

It is not yet clear how manga and anime culture assist Janosch in constructing this space. One central theme in Janosch's identity process is the recognition of the importance of friendships. This has already been analyzed as a process of reflection about his experience with being bullied, and from a network perspective, discussed as a source of recognition and a basis for his identity work. For that reason, this analysis of manga/anime is focused on his friendships.

“In anime books and movies, I experience things like friendships and love… and I also experience traits like helpfulness and tolerance and that's how I form strong friendships and that is realy important to me. All of that is involved in the stuff I do with my friends” (I3, line 38).

Although friendship can occur across all types of people, for the purposes of this study, friendship is understood as a relationship between same-age peers. This assists the researchers to create a clear picture of the existence and development of social emotional skills. Aspects of social emotional development of hearing children is the theoretical foundation for this analysis. The fact that Jansoch learns as part of his identity process to meet challenges with the help and support of others appears demonstrate delayed independence, in comparison to hearing children. Hearing children learn in early childhood, how to build friendships through working together to solve problems. Petermann and Koglin (2013) emphasize the relevance of social emotional development in early childhood. However, it appears that Janosch was not able to exercise an equal amount of guided interaction with same-age peers at an early age. For Janosch the highly complex co-regulated process of parent-child and child-child interactions did not occur.

In addition, many children with CHARGE experience significant medical challenges to include difficulty with swallowing, requiring tube feedings and often will demonstrate a lack of nutituion. These challenges may result in strained parent-child relationships which can impact the child's ability to interpret their emotional states as well as others. Prosocial behaviors such as regulating one's own affect, and demonstrating empathy in social situations may affect forming relationships with other children. Therefore, delayed social emotional abilities fundamentally affect the building of friendships.

These recognized developmental delays are not only present in building friendships but also present challenges to the parent-child relationships. This is further complicated by parents of deaf children who don't know sign language. If communicative exchanges are complicated by the language differences between hearing and deaf people, then communication about emotions and emotional sensitivities is presumably complicated as well. From this perspective it makes sense to seek other ways of communicating, however this represents a deficit oriented approach. One should not view Janosch's development of social emotional skills as altered, nor should they be viewed as somehow his fault. In the face of swallowing difficulties and inadequate nutrition intake, parents of children with CHARGE Syndrome need connected to support networks like the Multi-Professions Network as described in Trider et al. (2017). Parents can learn how to create the best possible conditions for their children's development. In the case of deafness it is important to note that, because sign language is a natural language, the societal environment is responsible when acceptable social interaction is not made available in early childhood. Families are in a difficult position regarding communication between deaf and hearing family members. Growing up as a deaf child in a hearing family causes problems with fitting in that start in early childhood. The communication difficulties that arise within families between deaf and hearing members are unfortunately extremely hard to overcome.

Additionally, comparing Janosch's social development to that of hearing children focuses on an oral/aural perspective that bears criticism and appears to be a useless comparison. Manga, is different from purely written literature, and provides many things that could be interesting to a deaf person. Friendship, community, love and social cohesion are common adolescent themes that are found in manga. Therefore, the content is presumably interesting and capable-oriented. Compared to classic novels, pictures play a much larger role in conveying one's story. This is of aesthetic value to Janosch as a deaf person, as access through pictures comes more naturally to him than through written language that is based on spoken language, a practice of the hearing world. It is important to note that Janosch clearly reads written language well, as he has read Eragon. In manga, gestures, facial expressions and body positions are conveyed through pictures and are therefore visually understandable. The combination of print and pictures-as-language make written aspects of the story visually available, creating another avenue of access to written language. This can also have aesthetic value for deaf people. Janosch seems to be drawn to manga both for its visual access and because of the social themes involved. In dramatic stories, manga makes emotions more accessible than photographs due to its exaggerated nature. Ladd (2008) compares the colonialization of deaf communities to that of oppressed African-American cultures. This could be a reason why, for deaf people, the themes in manga of acceptance, social mixing and integration of people from other backgrounds, can be so interesting. Further research is needed to be able to generalize.

Given these circumstances, it is logical perhaps and even expected that Janosh would experience this kind of openness from hearing people at conventions. Wearing costumes helps to decrease shyness in interactions among hearing people, and it can accomplish the same thing for Janosch as a deaf person among hearing people. In addition to cosplay, writing his own stories in online chat spaces provides an opportunity for Janosch to express himself, which he talks about in relation to writing WhatsApp stories. Although using WhatsApp as a vehicle to express himself to his friends is largely text based, even here he has an opportunity to express himself through memes, emojis, animojis, photos, videos and GIFs. Due to the fact that Janosch includes manga, anime, conventions and creative writing in his collage, it becomes clear that he views that culture and community as an interface between hearing and deaf culture. He also perceives the components of this culture as a resource that is relevant to his identity formation. In this way, tolerance, independence and helpfulness have become facets of Janosch's personality that have heped him, through his long-standing relationships with friends, to work on his shyness and extroversion.

Discussion

An analysis of the data about the formation of identity indicates a complex interconnected identity process. Social interaction and social development is defined by the analysis of Janosch's narratives. This happens more or less through networks of connected relationships with other people and groups.

The Importance of Friends

Janosch's friends are at the center of his world, since they can communicate together through German Sign Language. They form a stable network that provides mutual caring and respect. Janosch invests time and energy in these networks from a position of capability. The networks provide a range of options and a socially relevant structure. Within these networks, Janosch can anchor his identity projects, like becoming more extroverted. In many ways, having a well-functioning social netork allows for successful identity development (Keupp et al., 2002).

The Hearing World

Hearing people play a role in Janosch's identity work as well. However, his identity work here is rooted in a lack of the internal resources of appreciation that occurs when he is rejected or devalued as a deaf person. This, in addition to other self-reflection, has caused Janosch to want to become a more tolerant person (his identity project). He is able to implement this project within the Manga community, through connections with certain hearing people.

The Family

Currently, Janosch's family does not play a very important role in his narrative as an anchor for his identity project, as he is not able to spend as much time with them as he does with his friends. This is in part because of the communication difficulties between him and his parents. Given his age and his family situation, his becoming more independent of his family and finding a job is not so unusual.

CHARGE Syndrome and Other People With CHARGE

Janosch does have relationships with people with CHARGE Syndrome, as seen in his friendship with J., but this does not comprise a network of people with CHARGE. Janosch does not view the syndrome as an important element of his identity. In relation to his own development, CHARGE Syndrome is not a relative attribute of his identity project nor does he share the common fears and concerns of parents whose children have CHARGE. In his view, these kinds of fears only inhibit people with CHARGE from becoming independent. Janosch contrasts this with his own journey toward independence. His story shows that his strong motivation to become independent is due in part to being underestimated. Janosch uses CHARGE Syndrome to further his identity work. For this writer, many aspects of Janosch's story demonstrate how identity is formed. In many ways, manga and anime serve as means of access to concepts like friendship, community and helpfulness. These concepts permeate his identity in multiple ways. Building on the concepts explored in manga and anime, Janosch participates in the vibrant manga culture and experiments with role-playing, both through wearing costumes at conventions and through his creative writing of anime stories with his friends. It is interesting that one half of the participants experiment with these same ideas through manga, anime and/or cosplay.

Timing Analysis

Looking back over time, it is clear that Janosch used his experience with being bullied as a pertinent identity resource. Although this experience was one of rejection and fear, Janosch is able to see the value in interacting with other people, in being helpful and in being a loyal friend. Experience and the earlier identities involved serve as a point of reference for Jansoch's developing identity and contribute toward a state of coherence. Janosch describes his childhood self as a loner and a victim of bullying who was ostracized by his fellow students. He had few close friends, was unhappy, fearful, shy, and lonely. His identity process has allowed him today to become a confident, independent person.

Upon reflection, we see that Janosch has not completely overcome his shyness. While a part of his identity demonstrates that as a friend he can be extroverted and help his friends to be more open and brave, Janosch can still be quite shy around hearing people. Here again, the wearing of costumes at conventions is important. In closing, a literary perspective reveals that manga and the vibrant culture of this genre are especially meaningful for Janosch as a deaf person, especially in his relations with hearing people. Manga culture forms a shared space between hearing and signing culture. This space enables access for people from both cultures. Janosch is able to participate with differing and even contradictory partial identities. This creates room for lively identity development.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

AW designed and carried out the study and wrote the article.

Funding

This project received support from the Friede Springer Foundation.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges Jim Witmer.

Footnotes

1. ^Cosplay: Means Costume and Play: the practice of dressing up as a character from a movie, book, or video game.

References

Ahbe, T. (1997). Ressourcen -transformation - identität, in Identitätsarbeit heute: klassische und aktuelle Perspektiven der Identitätsforschung. eds H. Keupp, and R. Höfer (Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp), 207–226.

Blake, K., Davenport, S. H., Hall, B. D., Hefner, M. A., Pagon, R., Williams, M. S., et al. (1998). CHARGE association - an update and review for the primary pediatrician. Clin. Pediatrics 31, 159–174. doi: 10.1177/000992289803700302

Borgards, R. (2012). “Tiere in der Literatur - eine methodische Standortbestimmung”, in Das Tier an sich: Disziplinen übergreifende Perspektiven für neue Wege im wissenschaftsbasierten Tierschutz, eds H. Grimm, and C. Otterstedt (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht), 87–118

Bourdieu, P. (1983). “Ökonomisches Kapital, kulturelles Kapital, soziales Kapital,” in Soziale Ungleichheiten, ed R. Kreckel (Göttingen: Schwartz), 183–198.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). “The forms of capital,” in Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, ed J. Richardson (New York, NY: Greenwood).

Brown, D. (2005). CHARGE syndrome “behaviors”: challenges or adaptations? Am. J. Med. Genet. 133, 268–272. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30547

Brown, D. (2011). Deaf-Blindness, self-regulation, and availability for learning: some thoughts on educating children with CHARGE syndrome. ReSources 16, 1–7.

Davenport, S. L. H., Hefner, M. A., and Mitchell, J. A. (1986). The spectrum of clinical features in CHARGE syndrome. Clin. Genet. 29, 298–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1986.tb01258.x

Dresing, T., and Pehl, T. (2018). Praxisbuch Interview, Transkription & Analyse. Anleitungen und Regelsysteme für qualitativ Forschende, 8th Edn. Marburg: Eigenverlag.

Franz, J. M. (2005). “Arts-based research in design education,” in Proceedings AQR Conference (Melbourne, VIC).