- 1Department of Education Sciences, European University Cyprus, Nicosia, Cyprus

- 2Faculty of Psychology and Educational Sciences, University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal

This article presents the results of a study, conducted within the scope of the EU-funded project RELOBIE: Reusable Learning Objects in Education, which investigated faculty perceptions and practices regarding the educational use of contemporary and emerging technologies. A cross-national, in-depth online survey of n = 171 faculty members in the four partner countries (Estonia, Cyprus, Norway, Portugal) took place. Seventy-six (n = 76; 44.4%) of these faculty members taught courses which were either offered at-distance (no face-to-face component), or involved a significant online component (blended courses). The study gained some useful insights into online instructors’ perceptions, motivations, and experiences regarding the instructional use of digital videos and other technologies (e.g. subject-specific software, collaboration tools, games, simulations, virtual labs). It also shed some light into both facilitating and inhibiting factors to the effective integration of learning and communication technologies into online courses’ design and delivery.

Introduction

The advent of the Internet and the rapid advances of online technologies had a huge impact on the way education is perceived and delivered, as well as on the range of learning opportunities in formal, non-formal and informal education. Distance education, is a form of learning that can be traced back to late 19th century, rooting in correspondence courses. Technological advances, have largely transformed approaches and methodologies of distance education throughout the years, and hence Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) has gained a substantial role in this process.

E-learning and online course delivery has become common in most disciplines as well as in most educational levels. Online course design and learning is mainly linked to distance education, but in the last couple of decades it has been largely expanded to other forms of learning and pedagogical approaches that involve online technologies, such as blended learning, e-learning in face-to-face environments, and even online learning forced by emergency situations (e.g. the COVID-19 pandemic in year 2020). Hence, educational institutions at all levels, including leading research universities, have become increasingly involved in both distance education initiatives (Allen and Seaman, 2014), as well as other e-learning activities that involve online course and learning content delivery (Aparicio et al., 2016; Blayone et al., 2017). The expansion of online and distance education is likely to continue in forthcoming years, given the expanding access to the Internet and the greater emphasis given to lifelong learning.

Educational systems worldwide, at all levels of instruction, are engaged in a number of initiatives aimed at transforming teaching practices and processes through the embracement of new e-learning technologies. During the last decade, education has changed dramatically, either gradually, as a result of the advances in learning technologies and relevant methodologies per se (e.g. AI-based learning systems, virtual learning communities, mobile learning technology, cloud-based computing, etc.) (Mintz, 2013; Marzilli et al., 2014; Meletiou-Mavrotheris and Koutsopoulos, 2018), or forced into further experimentation by societal and global changes (e.g. non-discrimination policies for reshaping digital learning toward equality and human rights, the COVID-19 pandemic, etc.) (Center on Online Learning and Students with Disabilities [COLSD], 2016; Hoogerwerf et al., 2020; Govindarajan and Srivastava, 2020; UNESCO, 2020). Hence, as digital learning reshapes education at all levels, higher education has an unprecedented opportunity to reshape and revolutionize both conventional and distance education, creating meaningful and engaging learning environments.

In addition to the above, it seems that variables and factors affecting the effectiveness on online teaching and learning have very recently been reconceptualized and redefined with the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. The need for emergency response in terms of migration of face-to-face courses to an online environment, indicated the importance of previous experiences and expertise of Higher Education Institutions on digital transformation (Hargis, 2020).

Advances of web technologies and the enormous diversity of technological tools currently available (e.g. multimedia tools (Kahn, 1997; Junaidu, 2008; Mandernach, 2009), novel communication and collaboration tools (Meletiou-Mavrotheris and Mavrotheris, 2007; Duffy, 2008; Williams and Chinn, 2010; Baxter et al., 2011; Roodt and Peier, 2013; Blayone, et al., 2017), have been integrated in higher education, and have significantly enhanced leaning and instruction activities toward a transformation in the modes of communication and interaction. The recent predictions of educational experts for the occurrence of significant innovative shifts in higher education in the upcoming years (Anderson et al., 2012; Marzilli et al., 2014), are already becoming a reality. Higher education is driven away from traditional approaches and toward the wide adoption of contemporary digital technologies. Institutions’ infrastructure and availability of innovative and revolutionary technological tools for teaching and learning, consist one of the main aspects that facilitate (or not) the digital transformation. At the same time, current research indicates that mere use of technological tools cannot, in and of itself, directly change teaching or learning. Rather, a large corpus of literature argues that the way technology-enhanced learning processes are designed and implemented, in both face-to-face and distance education environments, is the key element impacting its success (Oliver and Herrington, 2000; Seidel et al., 2013; Guy and Marquis, 2016).

Design and implementation of technology enhanced learning environments largely depends on users’ intention to use technology, which is connected to one’s own perceptions of technology usefulness, relevance, and difficulty in use (Long et al., 2017), In the framework of a learning environment, users of technology are both learners and instructors. However, the perceptions of these two groups of users are often different, particularly when it comes to how engaging and effective for learning they consider different technological tools and strategies to be (Bolliger and Martin, 2018; Kumar et al., 2020). In addition, instructors’ self-perceptions, which relate to issues of professional development on technology-enhanced learning, also seem to influence the level of technology adoption in Higher Education (Georgina and Olson, 2018). Changing teaching practices, in particular, is proving to be very difficult, as it is not only about adopting new technology tools, but also about shifting learning paradigms and changing mindsets. The introduction of ICT has brought new challenges for instructors, adding a new set of variables into their already complicated and demanding task of lesson planning and implementation.

Though instructors may generally value the potential of technology to improve the effectiveness of teaching and learning in higher education (e.g. Dahlstrom and Brooks, 2014; Herrero et al., 2015), a number of factors influence their motivation and interest in exploiting opportunities for the effective integration of technology, especially in online environments. Instructors’ perceptions are affected by their level of experience in the implementation of technology enhanced learning strategies and methodologies, and by their pedagogical beliefs regarding innovations (Aijan and Hartshorne, 2013; Long et al., 2017), Similarly to teachers in other educational levels, university instructors are by no means technology experts and, in many cases, have not received any form of pedagogical training on the design and implementation of online learning education practices (Ertmer et al., 2012; Laurillard, 2013; McDonald et al., 2014). Lack of knowledge is identified by instructors themselves as one of the barriers to the use of technology, and their difficulty to catch up with technological advances, is often connected to anxiety that technology may replace the instructor (Marzilli et al., 2014). This is one of the main reasons why any kind of digital competence development program should go beyond technological skills, and be associated with pedagogies that require a very different skillset compared to conventional teaching, while at the same time also building participants’ confidence in utilizing technology in instruction, as well as their appreciation of the added value of technology enhanced learning.

Staff workload (Kear and Rosewell, 2018), is also identified as one of the factors affecting instructors’ attitudes and experiences in the use of technology in higher education. The wide range of e-learning tools, programs, technologies and information sources currently available, can be overwhelming and create an immense need for digital competence development, which instructors need to handle along with other teaching, research and administrative duties. In a recent survey on faculty attitudes toward technology, more than half of the participants mentioned that their institution is not being supportive in terms of compensation and acknowledgment of the increased workload that the preparation of online and technology enhanced courses is demanding (Jaschik and Lederman, 2019).

The type of professional development and training higher education faculty receive is an additional factor influencing their attitudes and motivation toward technology use (Lidof and Pasco, 2020). The literature indicates that professional development which either formally or informally involves peer support and collaboration, often proves particularly effective (Dysart and Weckerle, 2015; Long et al., 2017). During the COVID-19 pandemic, in order to support teaching staff, some universities even compensated faculty for their engagement in professional development aimed at assisting them in redesigning their courses for online delivery (Hagis, 2020).

Acknowledging the challenges, individuals and organizations are continuously exploring innovative approaches to effectively exploit the possibilities offered by the abundance of emerging technologies for learning and instruction, especially through enhanced professional development programs. The urgent need for training, guidance and support in this field is also strongly emphasized in the European Commission (2014) Report “New modes of learning and teaching in higher education”.

Therefore, preparation of instructors in higher education is essential for true technology transformation of teaching and learning practices to occur (Marzilli et al., 2014; Meletiou-Mavrotheris et al., 2018). The imperative of digitalization of learning in higher education regardless of mode of delivery–face-to-face, blended, distance education–is calling for further consideration of instructors’ technology experiences and expectations in order to understand the overall ecosystem of ICT integration in higher education (Dahlstrom and Brooks, 2014).

This article presents the results of an international study focused on investigating higher education instructors’ perceptions, motivations, and experiences regarding the use of digital videos and other technologies for personal, professional, and instructional purposes. The study was conducted within the scope of the EU-funded project RELOBIE: Reusable Learning Objects in Education (2014-1-FI01-KA200-00083). Through a cross-national, in-depth survey of faculty members’ attitudes and practices in the partner institutions, the study was designed to address the following research questions:

1. What are faculty members’ attitudes and levels of use of Learning and Communication Technologies in daily life and in the higher education classroom (face-to-face, blended, or completely online)?

2. What factors are identified by faculty members as encouraging or inhibiting the adoption and effective use of Learning and Communication Technologies in the higher education classroom?

3. How do attitudes and practices vary in relation to instructors’ prior experiences in online and face-to-face teaching in higher education?

A previous publication on the same project and research study (Meletiou-Mavrotheris et al., 2017) has extensively presented and discussed an overview of faculty perceptions and practices in relation to the use of technology, focusing mostly on the use of videos as one of the main technologies integrated in the universities’ learning practices. Reflecting on the findings presented in Meletiou-Mavrotheris et al. (2017), authors have realized that further data analysis on how faculty perceptions may vary (or not) based on their prior experiences (or lack of) in teaching fully at-distance or blended courses would be useful in better understanding faculty perspectives and needs for further professional development. Therefore, in the present paper, based on the same methodology of research design and data collection (please see declaration on text similarity at the end of this paper) authors present and discuss data analysis and results by making an effort to compare the responses to the survey of the group of instructors with prior experience in teaching distance or blended courses, to those of the group of instructors with no such experience. In addition, as this further analysis and reflection on existing research findings has taken place in an era where the use of new and online technologies proved vital, i.e. during the COVID-19 pandemic, conclusions and discussion in the present paper shift the focus of the study to a different direction. Hence, this paper adds to the previous publication (Meletiou-Mavrotheris et al., 2017) in three ways: 1) reconsiders and reanalyzes findings according to participants’ prior experiences in distance and conventional courses; 2) reflects on the RELOBIE project findings in the light of the current urge for online learning practices, by discussing the importance of faculty experiences, attitudes and readiness for this kind of forced digital shift; and 3) discusses how some of the participating universities have implemented strategies based on the impact of the previous findings of this study (e.g. see DEL at European University Cyprus in concluding section).

Methodology

Context of the Study

Acknowledging the potential of videos and other ICTs to transform higher education, but also the crucial role of teachers in any effort to bring about change and innovation, the EU-funded project RELOBIE aimed to improve adult and higher education through strengthening instructors’ knowledge and skills in effectively using videos and other technologies in teaching and learning. The project integrated data from several sources to portray a comprehensive picture of the expectations and experiences of students and instructors in the participating institutions (University of Coimbra, Portugal; European University Cyprus; Abo Akademi, Finland; Tartu University, Estonia) regarding the educational application of videos and other digital technologies. Partners utilized findings from the study to empower educators with better tools, skills and know-how on video production and use in particular, and technology-supported learning more generally.

To provide responses to the research questions posed in this article, we focus on the findings of an in-depth faculty survey conducted within the RELOBIE project (details about the student survey and its findings can be found on the project website: https://relobie.wordpress.com/the-survey/).

Instruments, Data Collection and Analysis Procedures

The survey instrument was built based on the international literature and other faculty technology surveys employed in previous studies (e.g. Jaschik and Lederman, 2013; Marzilli et al., 2014). Most of the questions were closed-ended, requesting Likert-type ratings or multiple-choice responses. A few open-ended questions requiring text-based responses were also included, in order to allow respondents to express ideas difficult to place on a Likert-scale and to obtain more comprehensive information.

The survey was divided into four sections as follows:

• Demographics: Age, gender, affiliation, department, years of teaching in adult/higher education institution, employment status, types of students mainly working with (undergraduate, graduate, professional).

• Technology Background and Experiences: Level of familiarity with technology, frequency of use of different technologies (e.g. email, personal website, smartphones, tablets, e-books/e-readers, MOOCs, online surveys, etc.) either personally or professionally, extent of technology integration into classes, frequency of instructional use of different technological tools (e.g. PowerPoint presentations, Prezi presentations, lecture capture, podcasts, simulations, gaming, or virtual worlds, etc.), level of interest and experience in course delivery styles involving a significant online component (completely at-distance, blended, flipped classroom, MOOC), stage within the technology adoption and integration into the teaching and learning process.

• Usage of Video in Instruction: Frequency of video incorporation into courses (face-to-face, blended, completely online), length of video programs or segments shown, frequency of use of supplementary guides or lesson plans to accompany videos, types of videos shown to students (e.g. captured lectures or mini-lectures, YouTube or other ready-made videos, guest performances/public screening of video, etc.), means of locating ready-made videos for using in the classroom (e.g. recommendations from media specialists, recommendations from other instructors, internet browsing, etc.), means of gaining access to ready-made video programs for use in the classroom (e.g. borrow from the library, purchase online, download for free online etc.), interest in using more video material in courses (ready-made videos/videos produced by themselves).

• Incentives and Barriers to the Instructional Use of Videos and other Technologies: Reasons for using videos with students in face-to-face classrooms, reasons for using videos for lecture capture and/or for recording mini-lectures, issues/challenges encountered in using or attempting to use videos and/or other technologies for instructional purposes, importance of factors motivating faculty to integrate videos and/or other technologies into instruction and curricula.

• The survey instrument was developed in English. After being pilot tested and revised based upon received feedback, it was posted electronically via Google forms (see Relobie Faculty Survey instrument). The survey took about 20 min to complete. It was administered to faculty members in four partner institutions: Abo Akademi, Finland; Universidade de Coimbra, Portugal; European University Cyprus; and Tartu Ulikool, Estonia. Invitation messages explaining the purpose of the study, and providing a link to the survey, were sent via email to both full-time and part-time faculty members in these institutions. Participation was completely voluntary and anonymous. No identifying information was collected from participants.

A total of 171 faculty members from various disciplines responded to the survey. The distribution of the respondents’ affiliation was as follows:

• Abo Akademi, Finland (23%, n = 40)

• European University Cyprus (29%, n = 50)

• Tartu University, Estonia (11%, n = 19)

• University of Coimbra, Portugal (36%, n = 62)

Quantitative data obtained from the survey were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics in order to provide answers to the research questions. For the text-based responses, a qualitative thematic analysis approach was followed, during which data were coded and clustered as themes. Themes emerged mostly from elements identified by the current literature, in key areas related to factors for technology adoption, level of technology use, and level of experience and competencies, including professional development opportunities. Linking the depth of qualitative data with quantitative breadth provided complementary information and a more holistic picture of faculty members’ processes of adopting and implementing technology in teaching and learning.

Participants’ Background Characteristics

Fifty-seven percent of the 171 instructors participating in the survey were female (n = 97), and 43 percent male (n = 74). The age distribution of the instructors was tending toward older cohorts. Two-thirds (68%) were older than 40, while one-third (32%) older than 50. Thus, the vast majority were experienced educators who had been teaching in a higher/adult education institution for a considerable number of years. Seventy-seven percent (77%) had more than 5 years of teaching experience, sixty percent (60%) more than 10 years, while a third (32%) had been teaching in higher/adult education for more than 20 years. Two-thirds (66%) were full-time employees, while the rest worked either on a part-time (22%), or on short-term employment (13%) basis.

Although the survey respondents represented fairly well the complete range of instructors in the participating institutions (in terms of gender, employment status, years of experience, etc.), the self-selected nature of the sample and the very low response rate in one of the institutions (Tartu University), made the collected data unsuitable for comparisons between institutions/countries. Similarly, the relatively small sample size did not permit comparisons among different academic disciplines. Thus, we chose to analyze the whole sample data across as a single cohort irrespective of affiliation and disciplines.

Seventy-six (n = 76; 44.4%) of the respondents taught courses which were either offered at-distance (no face-to-face component), or involved a significant online component (blended courses). Where deemed appropriate, comparisons were made between the group of instructors who had prior experience in teaching distance or blended courses (Online Group), and the group of instructors with no such experience (Conventional Group). Henceforth, the first group will be referred to as the Online Group, and the second group as the Conventional Group.

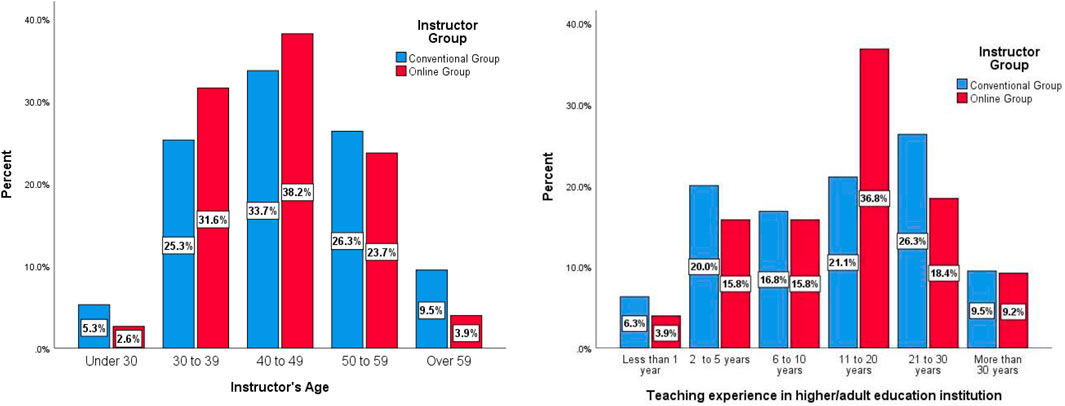

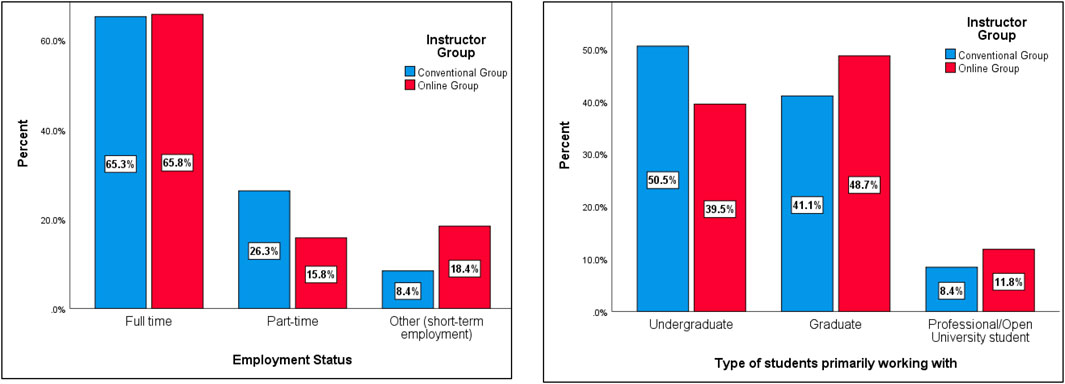

Survey respondents in the Online Group had similar background characteristics with respondents in the Conventional Group. The distribution of age, years of teaching experience, and employment status were very similar for both groups (see Figure 1-left, Figure 1-right, and Figure 2-left respectively). A Chi-Square test of independence indicated no significant difference between the two groups, in terms of either age distribution (χ2(4)= 3.423, p = 0.49 > 0 .05), teaching experience (χ2(5)= 5.814, p = 0.325 > 0.05), or employment status (χ2(2)= 5.449, p = 0.066 > 0.05). Although there are slight differences between the Conventional and the Online Group regarding the level of students that the study they primarily worked with (see Figure 2-right), with a higher percentage of instructors in the latter group working primarily with Graduate or Professional/Open University level students, the differences between the two groups were not statistically significant (χ2(2)= 2.66, p = 0.265 > 0.05).

FIGURE 1. Distribution of age (Figure 1-left), and teaching experience (in years) in a higher/adult education institution (Figure 1-right), for the OnlineGroup and the Conventional Group.

FIGURE 2. Employment Status (Figure 2-left) and level of students instructors in the Online Group and the Conventional Group primarily worked with (Figure 2-right).

Results

Findings from the faculty survey have been organized into three parts, reflecting the survey’s research questions:

1. Instructors’ attitudes and levels of use of Learning and Communication Technologies in daily life and in the higher education classroom

2. Factors encouraging or inhibiting the adoption and effective use of Learning and Communication Technologies in higher education.

3. Variations in instructors’ attitudes and practices in relation to prior experiences in online and face-to-face teaching in higher education

Attitudes and Levels of Technology Use in Daily Life and in the Higher Education Classroom

Participants were inquired to indicate their level of familiarity with technology. Only five instructors (3%) rated themselves as beginners. More than half (n = 92, 54%) rated their familiarity level at the advanced or expert level. At the same time, a considerable proportion (n = 74, 43%) considered themselves to be at an intermediate level. This suggests that a sizable proportion, while being experienced with technology, lacked relative sophistication.

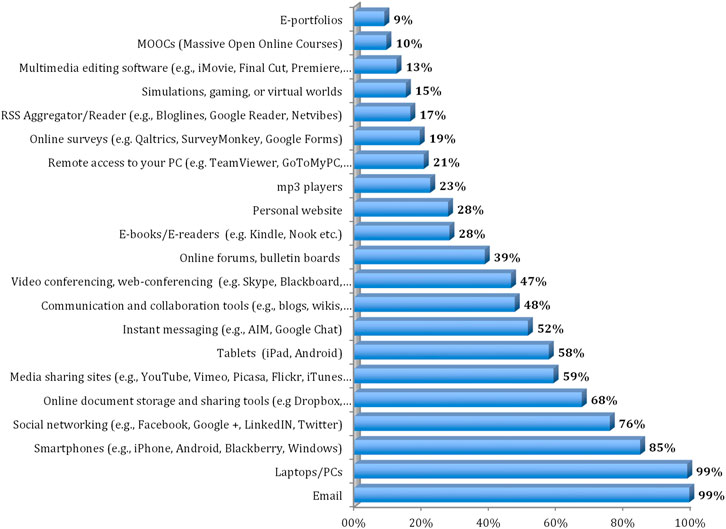

Instructors provided information about their technology usage patterns by indicating, using a 5-level Likert scale (5 = Daily, 4 = Weekly, 3= Monthly, 2 = Less often than monthly, 1 = Never), the frequency with which they used each of a list of 21 different technological tools in their personal or professional lives (other than teaching). Figure 3, shows the percentage of participants reporting that they used each technological tool on a daily or weekly basis.

Large majorities of the instructors used the following tools on a daily or at least weekly basis: Emails (99%); Laptops/PCs (99%); Smartphones (85%); Social networking tools (76%); Online document sharing tools (68%). The majority also employed on a daily or weekly basis media sharing sites such as YouTube and Vimeo (59%), as well as Instant Messaging (52%), and tablets (58%). Slightly less than half regularly used social media such as blogs, wikis, video conferencing/web-conferencing tools such as Skype, and online forums.

It can, therefore, be safely concluded that a significant proportion of the respondents did make active use of communication and collaboration tools in their daily and/or professional lives. They also extensively used both mobile devices and laptops/PCs. By contrast, the vast majority infrequently or never used the following technologies: E-portfolios, MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses), multimedia editing software, simulations, gaming, or virtual worlds, RSS Aggregators/Readers, online surveys, remote access to PCs, mp3 players, personal websites, and e-books/e-readers.

The majority of instructors also reported utilizing technology in their classes. Forty-one percent stated that they considered technology as essential to success in their classes and fully integrated it into teaching and learning, while an additional 49 percent that they considered it to be a useful tool and encouraged their students to use it. Still, there were several instructors in our sample who noted either that technology was optional or that they had no use for technology in their class.

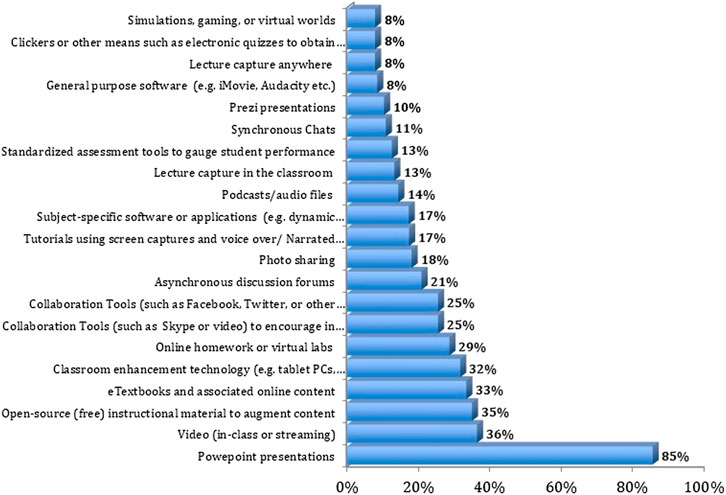

Participants were asked to indicate, using a 5-level Likert scale, the frequency with which they used each of 21 different technological tools in their teaching. Figure 4 illustrates the percentage of instructors that always or very often used each tool.

PowerPoint presentations was the only technological tool being regularly used by most of the instructors. Eighty-five percent reported always or very often using it in their classes. By contrast, the majority of the participants never or seldom used most of the other listed technological tools (in parenthesis the percentage rarely or never using each tool):

• Simulations, gaming, or virtual worlds (83%)

• General-purpose software such as iMovie and Audacity (82%)

• Clickers or other means such as electronic quizzes to obtain student responses in real time (78%)

• Synchronous Chats (77%)

• Lecture capture anywhere (76%)

• Lecture capture in the classroom (76%)

• Prezi presentations (73%)

• Subject-specific software (e.g. dynamic software for teaching statistics) or applications (71%)

• Standardized assessment tools to gauge student performance (70%)

• Podcasts/audio files (69%)

• Collaboration tools (e.g. Facebook, Twitter, or other social media) to encourage online participation or interaction outside the classroom (63%)

• Collaboration tools (e.g. Skype) to encourage in class or real time interactions (63%)

• Asynchronous discussion forums (63%)

• Photo sharing (62%)

• Tutorials using screen captures and voice over/Narrated presentations (62%)

• Online homework or virtual labs (57%)

Participants were also inquired on their experiences regarding the pedagogical model of flipped classroom. Only 16 percent indicated that they had ever used the flipped classroom method. Nonetheless, most of the remaining instructors noted that they were very interested (50.3%), or at least moderately interested (21.6%), in adopting such a pedagogical model.

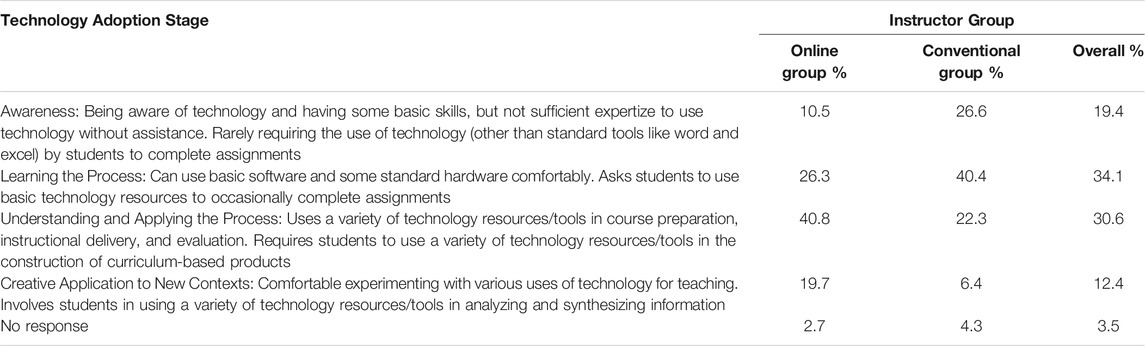

Instructors were also prompted to indicate the stage that they thought best described where they were within the technology adoption and integration into the teaching and learning process. Their responses are summarized in Table 1.

As shown in the last column of Table 1, around thirty percent of the instructors (30.6%) considered themselves to be at the Understanding and Applying the Process stage. These instructors utilized a variety of technological tools and resources for course preparation, instructional delivery, and evaluation, and also required their students to use a variety of technological tools and resources. An even smaller percentage (12.4%) felt comfortable experimenting with various uses of technology for teaching and learning, and thus rated themselves at the Creative Application to New Contexts stage. Therefore, based on the instructors’ responses, only 43 percent made extensive use of technology in their classroom. The majority (53.5%) rated themselves as being at the beginning stages of the technology adoption process–i.e. either at the Awareness Stage (19.4%) or Learning the Process (34.1%) Stage.

Given the focus of the RELOBIE project on videos, the questionnaire also sought detailed information on participants’ preferences and trends of video usage in instruction. In a question asking them to specify the frequency with which they integrated videos in their course(s), one third indicated that they made occasional use of videos (33% sometimes), while almost half (43%) that they made frequent use (29% very often, 14% always). A quarter of the respondents noted that they either used videos rarely (18%), or never used them in instruction (6%).

When prompted to specify the type of videos shown to their students, the majority reported employing YouTube or other ready-made videos, in either face-to-face (78%) or at-distance/blended courses (53%). There were also several instructors incorporating guest performances/public screening of video (24%). A sizable proportion also recorded their lectures or mini-lectures and embedded the recordings in either face-to-face (23%) or at-distance/blended courses (20%).

Regarding the duration of videos shown in class, most instructors stated that they tended to display videos of a short length, and to rarely or never show videos exceeding 10 min. They also specified that the main means of managing and making their videos available online, was through use of free web video services such as YouTube and Vimeo (86%). Around 20 percent of the respondents also used campus supported streaming video (22%) or uploaded their videos to a Learning Management System (17%). The main means of displaying videos in the face-to-face classroom was again through use of streaming video such as YouTube or Vimeo.

Almost two-thirds of the respondents (63%) stated that they would like to use more video material in their courses. The type of videos they would like to use with higher frequency included captured lectures or mini-lectures, educational video material made for instructional purposes, live guest lectures, program demos, and case studies/real scenarios on selected topics.

Factors Encouraging or Inhibiting the Instructional Use of Technology

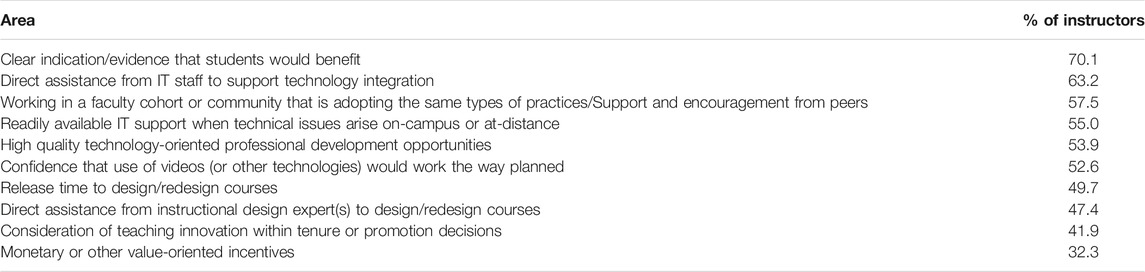

The survey inquired instructors to indicate factors that would motivate them to further integrate videos and other technological tools into their teaching practices. In one of the survey questions, participants had to rank a set of factors motivating faculty to integrate technology into teaching and curricula (with one being the factor with the highest importance and 10 the factor with the lowest importance). Table 2 shows the percentage of instructors who gave a ranking between one and three to each factor.

TABLE 2. Percentage of instructors having ranked the importance of each area between 1–3 (1 = highest importance … 10 = lowest importance).

The factor rated by the highest proportion of instructors as being an important motivation for them to integrate technology was “a clear indication/evidence that students would benefit” from its introduction. Thus, the most essential reason behind instructors’ willingness to incorporate any new technological tool into their teaching practices were its perceived benefits on student learning. Factors related to institutional resources and support (technical support, release time to design/redesign courses), pedagogical support (assistance from instructional design experts, professional development opportunities), and peer collaboration and support, were also deemed as important motivating factors in the technology integration process. Incentives related to monetary or other value-oriented rewards or tenure decisions, were the factors ranked last by instructors in terms of importance.

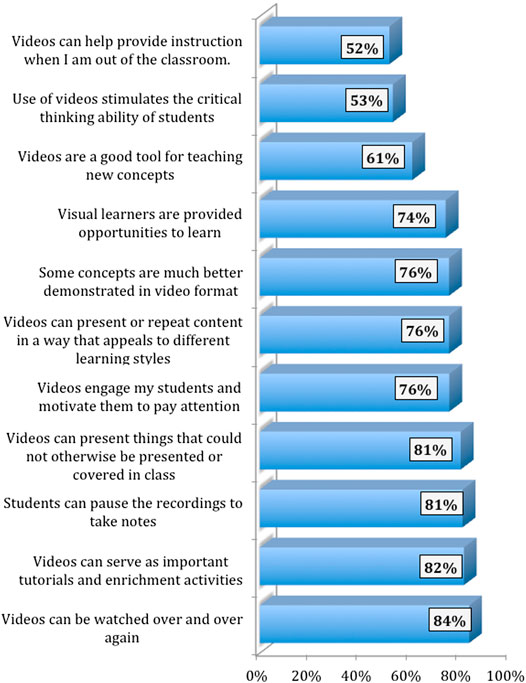

Concerning videos in particular, instructors had to indicate, using a 5-point Likert scale, how important they considered each of a number of reasons for using videos in instruction (5 = very important, 4 = important, 3 = neutral, 2= not very important, 1 = not at all important). The percentage of instructors rating each of the stated factors as an important or very important reason for using videos in face-to-face teaching is shown in Figure 5.

FIGURE 5. Percentage of instructors considering each factor as an important or very important reason for using videos in face-to-face teaching.

Most of the instructors rated each of the listed factors as an important reason for incorporating videos into the face-to- face classroom. Thus, the vast majority considered as important or very important reasons for incorporating videos into face-to-face instruction the fact that videos motivate students and attract their attention, can be watched over and over again, can serve as tutorials and enrichment activities, can be paused to take notes, and can illustrate concepts and ideas that could not otherwise be presented or covered in class. Most instructors also considered important the fact that videos appeal to different learning styles, and particularly to visual learners. However, the considerably lower percentage of respondents rating as important or very important the following factors is notable: 1) videos are a good tool for teaching new concepts; 2) use of videos stimulates the critical thinking ability of students; 3) videos can help provide instruction when I am out of the classroom. Based on instructors’ responses, it seems that they used videos in the classroom mainly to motivate students and to better illustrate or clarify taught concepts, rather than to introduce new concepts or to stimulate learners’ critical thinking.

Despite recognizing the educational value of videos and other technological tools, instructors identified several challenges and barriers to their instructional use: time constraints, outdated equipment, technical issues, difficulty in locating high quality material, copyright issues, lack of relevant material in the students’ native language. Concerning videos in particular, a sizable proportion of instructors reported the following challenges to their attempts to use videos for instructional purposes:

• Development of new videos to integrate into instruction requires too much of class preparation time (42.1%)

• Selection of appropriate videos to integrate into instruction requires too much of class preparation time (27.4%)

• The majority of high quality videos found on the internet are in English with no subtitles (40%)

• Lack of readily available administrative/technical support for the integration of videos or other educational tools into teaching and learning (26.3%)

• Inclusion of videos within course delivery requires too much class time (e.g. long videos, slow video downloading, buffering problems etc.) (25.3%)

• Lack of technological skills and/or pedagogical skills required to effectively integrate videos into teaching and learning (25.3%)

• Lack of professional development opportunities that target the use of videos in instruction by instructors’ institution (21.1%)

• Most of the video material available online has low esthetic value, and/or poor video or sound quality (17.9%).

Variations in Attitudes and Practices in Relation to Prior Experiences in Online and Face-to-Face Teaching

In this section, we present key findings from the conduct of statistical analysis aimed at comparing responses to the survey questions of participants with prior experience in teaching distance or blended courses (Online Group) to those of instructors with no such experience (Conventional Group).

Instructors’ responses to the question inquiring them about their level of familiarity with technology, indicated a similar level of familiarity between the Online Group and the Conventional Group (χ2(3)= 4.683, p = 0.173 > 0.05). Chi-square tests of independence conducted to compare the frequency of use in daily or professional of each of the 21 technological tools listed in Figure 3, indicated significant differences between the two groups with regards to only the following tools.

• Online document storage and sharing tools such as Dropbox (χ2(4)= 10.006, p = 0.04 < 0.05)

• Social networking sites (χ2(4) = 11.670, p = 0.02 < 0.05)

• Instant messaging (χ2(4) = 15.117, p = 0.04 < 0.05)

• RSS Aggregators/Readers (χ2(4) = 10.598, p = 0.031 < 0.05)

• Media sharing sites (χ2(4) = 9.675, p = 0.046 < 0.05)

• Online surveys (χ2(4) = 9.439, p = 0.049 < 0.05).

Higher proportions of the instructors that had experience in blended or at-distance education made frequent use of online document storage and sharing tools (e.g., Dropbox, Google Drive, Skydrive), social networking sites (e.g., Facebook, Google+, LinkedIN, Twitter), instant messaging (e.g., AIM, Google Chat), RSS Aggregators/Readers (e.g., Bloglines, Google Reader, Netvibes), media sharing sites (e.g., YouTube, Vimeo, Picasa, Flickr, iTunes U), and online surveys (e.g., Qaltrics, SurveyMonkey, Google Forms).

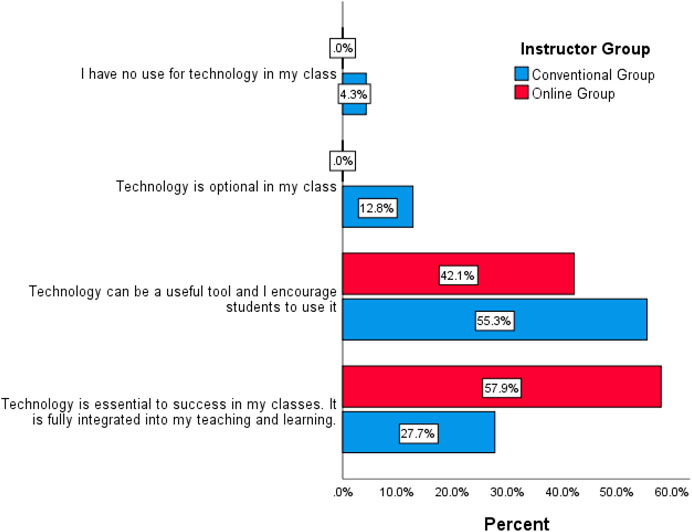

Figure 6 illustrates responses of the Conventional Group and the Online Group to a question requiring them to indicate the extent of technology integration into instruction.

FIGURE 6. Extent of instructional integration of technology for the Online Group and Conventional Group.

There were significant differences between the Online Group and Conventional Group regarding the extent of instructional integration of technology (χ2(3)= 21.586, p = 0.001 < 0.05). As shown in Figure 6, while 58 percent of the instructors in the Online Group considered technology as essential to success in their classes, the corresponding percentage for the Conventional Group was only 28 percent. Moreover, while (obviously) no instructor in the Online Group indicated that technology is optional or that they have no use for technology in their class, 17 percent of the instructors in the Conventional Group did.

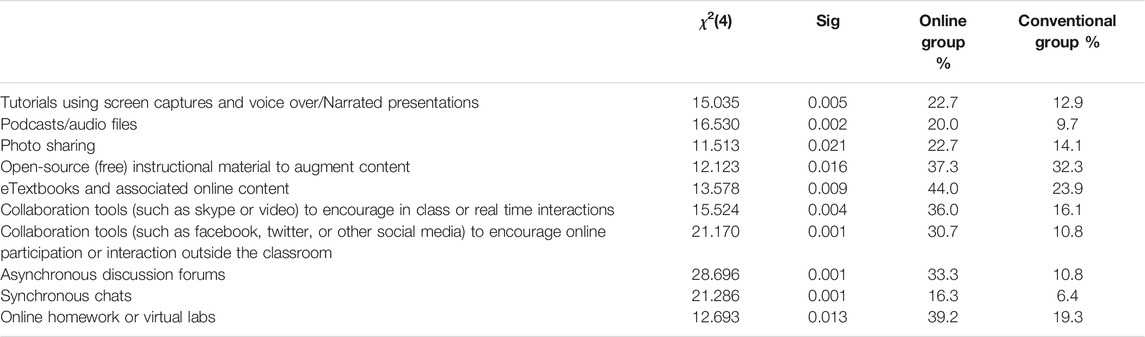

Chi-square tests of independence were also conducted for each of the 21 technological tools presented in Figure 4, in order to investigate whether there were differences in the level of their instructional use between the Online Group and the Conventional Group. Significant differences between the two groups were observed for ten of these tools. Table 3, displays the results of the chi-square analysis for these ten tools, and the percentage of instructors in each group always or very often employing each tool.

TABLE 3. Results of chi-square analysis, and percentage of instructors in the online group and conventional group always or very often employing the following tools.

As shown in Table 3, somewhat higher proportions of the instructors with prior experience in blended or at-distance education always or very often employed tools such as tutorials using screen captures and voice over, podcasts/audio files, photo sharing, open-source instructional material, eTextbooks and associated online content. However, overall findings indicate the tendency of instructors in both the Online Group and the Conventional Group to view technology as mainly a means of more efficiently delivering content and information. The majority of faculty in both groups made low use of technologies that can promote more engaging, interactive, student-centered pedagogical approaches, such as simulations, gaming, virtual worlds, electronic voting systems, and media manipulation software. Also, although a somewhat higher proportion of instructors in the Online Group made frequent use of tools promoting communication and collaboration (collaboration tools, asynchronous discussion forums, synchronous chats), the majority in both groups reported never or rarely using these tools. Despite the fact that the study participants were well familiar with social media and broadly used them in their daily lives and in professional contexts outside of teaching, the vast majority reported never or seldom utilizing them in instruction.

Comparing the self-selected stages of technology adoption and integration of the Online Group and Conventional Group (see Table 1), we find significant differences favoring the Online Group (χ2(4)= 19.099, p = 0.001 < 0.05). A considerably higher percentage of instructors with prior experience in blended or distance education considered themselves to be either at the Understanding and Applying Process, or the Creative Application to New Contexts stages (Online Group: 68.5%, Conventional Group: 28.7%). Twenty-percent of the instructors in the Online Group considered themselves to be at the Creative Application to New Contexts stage, while only 6 percent of the instructors in the Conventional Group did.

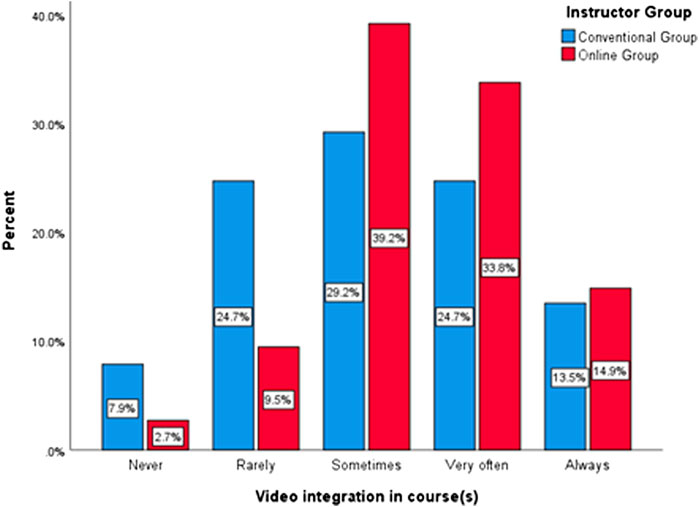

Significant differences were also observed in the patterns of video usage between the Conventional Group and the Online Group (χ2(4) = 9.636, p = 0.047 < 0.05). As shown in Figure 7, whereas one-third of the instructors in the Conventional Group (32.6%) rarely or never used videos in their courses, the corresponding percentage for instructors in the Online Group was only 12 percent. While half of the instructors in the Online Group (48.7%) frequently used videos in instruction, a considerably lower percentage of instructors in the Conventional Group did (38.2%).

In the question where participants had to indicate how important they considered each of a number of reasons for using videos in face-to-face instruction, results were similar for both the Online Group and the Conventional Group. The majority of instructors, regardless of the group they belonged to, rated each of the listed factors as an important reason for incorporating videos. The only factors for which there were significant differences between the two groups were the following: 1) Videos can be watched over and over again (χ2(4)= 12.126, p = 0.007 < 0.05); 2) Videos can serve as important tutorials and enrichment activities (χ2(4)= 11.283, p = 0.024 < 0.05); 3)Videos can present or repeat content in a way that appeals to different learning styles (χ2(4)= 9.982, p = 0.041 < 0.05); 4) Visual learners are provided opportunities to learn (χ2(4)= 12.847, p = 0.012 < 0.05). A somewhat higher percentage of the instructors in the Online Group compared to the Conventional Group considered these factors as important/very important (see Table 4).

TABLE 4. Results of chi-square analysis, and percentage of instructors in the Online Group and Conventional Group always or very often employing the following tools.

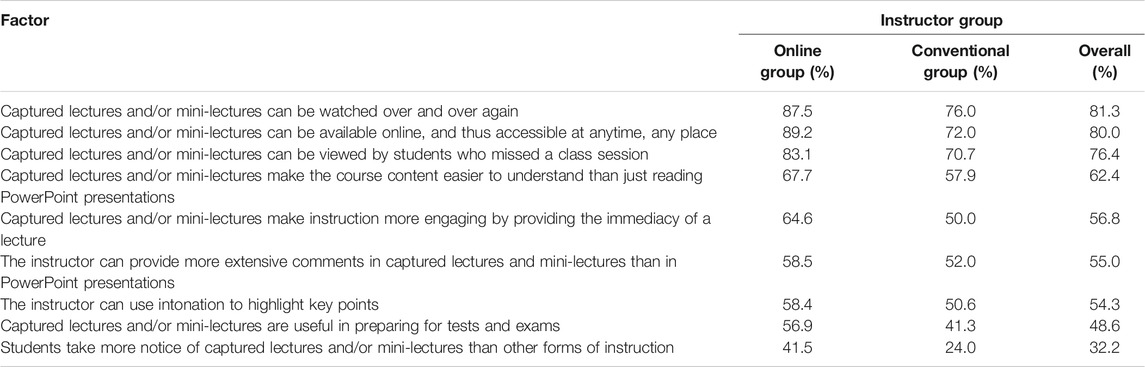

In a related question, instructors rated the level of importance of each of a number of factors for using videos for lecture capture and/or for recording mini-lectures. The percentage of instructors in the Online Group and the Conventional Group rating each factor as important or very important is shown in Table 5.

TABLE 5. Percentage of instructors in the online group and conventional group rating each factor as “Important” or “Very Important” for using videos for lecture capture and/or for recording mini-lectures.

Evidently, instructors in both the Conventional Group and the Online Group realized the power of lecture capture to broaden reach, enhance independent student study, and meet individual learner needs (Elliott and Neal, 2016). Their responses concur with the research literature, which highlights numerous advantages to captured technology, including the ability it provides for students to access lecture/mini-lectures at a time and place of their convenience (Panther et al., 2011), and to easily rewind, pause and review recording as many times as they wish (e.g. Panther et al., 2011; Al Nashash and Gunn, 2013), thus acting as a particularly helpful aid for better understanding and/or revising the course material (Panther et al., 2011; Taplin et al., 2011; Elliott and Neal, 2016). Most instructors however did not consider video lectures to be a substitute for lecture attendance (unless a student misses a class session), with only 32 percent agreeing that students take more notice of captured lectures and/or mini-lectures than other forms of instruction. This was particularly true for instructors in the Conventional Group, since only 24 percent of them, compared to 42 percent in the Online Group, considered this factor as an important or very important reason for using videos for lecture capture and/or for recording mini-lectures. A chi-square test of independence indicated significant differences between the two groups’ ratings (χ2(4)= 15.090, p = 0.005 < 0.05) concerning this factor, but also concerning two other factors: 1) Captured lectures and/or mini-lectures are useful in preparing for tests and exams (χ2(4)= 14.141, p = 0.007 < 0.05); 2) Captured lectures and/or mini-lectures can be available online, and thus accessible at anytime, any place (χ2(4) = 12.124, p = 0.016 < 0.05). A higher percentage of the instructors in the Online Group compared to the Conventional Group considered each of these factors as important or very important.

Discussion and Conclusion

Through a cross-national, in-depth survey, the current study has provided some useful insights into higher education instructors’ perceptions, motivations, and experiences regarding the employment of digital videos and other technological tools for personal, professional, and instructional purposes. The study has also provided useful information regarding perceived barriers to the effective integration of ICT into instructional settings.

Instructors’ Perceptions and Attitudes Coming Across Technology Competencies and Familiarity

Findings are in accord with those of previously conducted studies (e.g. Dahlstrom and Brooks, 2014; Marzilli et al., 2014; Herrero et al., 2015), which suggest that most higher education instructors have positive attitudes toward the educational use of videos and other contemporary technologies. Our study participants considered technology to be a valuable tool that can greatly enhance the instructional process in both traditional brick-and-mortar classrooms and virtual learning environments (Meletiou-Mavrotheris et al., 2017). They noted numerous, well cited in the research literature, benefits of technology, including: increased student motivation and engagement, more efficient delivery of course content, improved knowledge retention, personalization and differentiation of learning. Benefits that are discussed in the relevant research studies of the last decade, which highlight the importance of integrating technologies into the learning process in all educational levels (e.g. Tobolowsky, 2007; Gill 2011; Taplin et al., 2011; Eick and King, 2012; Ford et al., 2012; Bishop and Verleger, 2013; Yousef et al., 2014; Guy and Marquis, 2016).

The vast majority of instructors in both the Conventional Group and the Online Group did utilize technology in their classes. More than half of the participating instructors rated their familiarity level at the advanced or expert level. At the same time, however, a very high percentage considered themselves to be at an intermediate level. This suggests that a sizable proportion of the instructors, while being experienced with technology, lacked relative sophistication (Meletiou-Mavrotheris et al., 2017). Though it would be anticipated for the Online Group to denote a higher level of familiarity with technology than the Conventional Group, since the format of online and distance education classes imposes by default the use of technology, this was not the case. No statistical significant differences were observed between the two groups with regards to instructors’ self-reported levels of familiarity with technology.

Although there was considerable agreement among our study participants regarding the positive impact that technology might have on student engagement and learning, it became obvious that many instructors tended to lack appreciation of the true potential of technology for transforming the nature of higher education. The reported levels of use of different technological tools for instructional and learning purposes lagged behind their levels of use in daily life or in professional contexts outside of the classroom. Similarly, to other researchers, we also found that instructors tended to view technology as mainly a useful aid for delivering course content and/or for increasing student motivation, rather than as a tool for transforming teaching and learning (e.g. Lei et al., 2010; Marzilli et al., 2014). Although there were some differences between the Conventional Group and the Online Group in relation to the types of technology tools used, the majority of respondents in both groups restricted their use of technology to mainly representation tools such as PowerPoint, and made minimal use of interactive technologies (social media, simulations, games, educational software, media manipulation software, etc.) that can promote student-centered, collaborative, and inquiry-based learning environments.

A particularly noteworthy finding of the study is the fact that, although the vast majority of the participants were well familiar with social media and broadly used them in their daily lives, they reported no or seldom use of these tools in their instruction. What is interesting to point here is that, similarly to our study, social media are not among the preferred communication channels of higher education institutions during the COVID-19 pandemic period either, as indicated by research evidence available this far. According to Rumbley (2020), one of the key messages of a survey on COVID-19 coping mechanisms of international higher education in Europe is the surprisingly little (documented) use of social media as a key communication channel, though there is evidence of robust and multi-faceted communication efforts being undertaken by institutions across Europe.

Maybe one of the underlying issues is the lack of awareness and education of instructors on how our everyday interactions can really be learning experiences–for both us and our students–and how we can transform our everyday interactions into learning experiences promoting student communication and collaboration. Social media are mostly seen as tools to keep in touch with friends and family. Abe and Jordan (2013) are discussing whether “the use of social media in the classroom is worth the hassle” (p.16) in higher education, especially given that social media are often seen as having the potential to disengage students and draw their attention away from class content. Skepticism of educators, as well as parents, is also another factor discussed in the literature in relation to the use of social media for learning at all levels of education, though research is pointing to numerous benefits and added value (Andersson et al., 2014; Hagler, 2013; Goodyear et al., 2014). Hence, the concern is not only about integrating technology into learning and instruction. It is also about how we view our whole life as a learning experience, especially in higher education, where university life should be viewed as such (Uusiautti and Määttä, 2014). Arguably, it seems that there is hesitation in acknowledging that learning in higher education (and probably in other levels of education as well) can be continued outside the classroom (physical or virtual) and that skills acquired outside the classroom can be useful and part of academic learning.

Additionally, only a very small percentage of the instructors participating in the current study (12.4%), and particularly from the Conventional Group (Online Group: 19.7%, Conventional Group: 6.4%), rated themselves at the Creative Application to New Contexts stage of technology adoption, i.e. being comfortable experimenting with various uses of technology for teaching, and involving students in using a variety of technology resources/tools in analyzing and synthesizing information. This is particularly alarming given that an essential aspect of higher-order thinking and innovation is creativity, i.e. the ability to use one’s acquired knowledge and skills to produce novel products and solutions. The importance of cultivating 21st century students’ creativity is reflected in the revisions made in the early 2000 s to Bloom’s taxonomy–the influential framework that has been a central reference issue in curriculum design, implementation, and evaluation for more than half-century. Anderson and Krathwohl (2001), updated the original taxonomy, yielding the Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy, which includes the following levels: Remembering, Understanding, Applying, Analyzing, Evaluating, and Creating. The most important change was the removal of “Synthesis” and the addition of “Creating” at the highest-level of Bloom’s Taxonomy. Thus, the Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy considers learners’ ability to apply their knowledge in a novel approach to solving a problem (e.g. devising a new method, model or evaluation procedure), to be the pinnacle of cognitive tasks.

Moreover, the level of familiarity and/or frequency with which instructors reported using each of a list of digital tools in their teaching practices, indicated that some of these tools seemed to be more frequently and extensively used and more favorable for participants than others. However, based on experiences of follow-up projects and initiatives implemented by institutions involved in the present study (see paragraphs below), the level of appreciation and instructional use of certain tools seems to change based on the way these are promoted and used as examples during faculty professional development. As literature discussed in the introduction of the paper indicates, instructors’ level of experience in particular technology use (see Long et al., 2017) and type of professional development (see Lidof and Pasco, 2020) are essential for the use of technology in higher education. The follow-up experiences of this study also provide evidence to this argument. For example, audience response and participation tools, while low-rated by the participants of the present study, seemed to have been among the most popular and immediately adapted tools implemented by non-experienced (Conventional) instructors, after targeted designed professional development activities. More specifically one of the institutions involved (EUC) has implemented the Digital Enhanced Learning (DEL) initiative, which among others included targeted professional development, which was conducted based on a peer support and peer-coaching approaches (Louca, 2020). A number of the training sessions highlighted the importance of audience response tools in gaining direct interaction between instructor and students as well as between students and course content, and in providing direct feedback. Best practices of peers were presented and discussed in order to support the ways in which the affordabilities of audience response tools may engage and attract students’ attention and promote communication and collaboration, as well the fact that students can access these tools using their mobile devices, which in other circumstances they might not be allowed to use in class (or might need to hide to be able to chat with peers during class). Arguably, the way professional development for integrating digital technology into higher education practices is designed and implemented in specific cultures and settings, is crucial to its success.

Institutional Digital Culture and Professional Development: A Key Aspect

A main conclusion drawn from the study was the urgent need for partner institutions (and other higher education institutions as well) to cultivate more supportive cultures that would motivate instructors’ technology integration process. Study participants reported a number of challenges in their strive to keep pace with the pervasive spread of new and innovative classroom technologies. The issues mentioned most frequently were the high investment in time and effort required to keep up with technology advancements, the need for administrative and peer support, and the need for continuous training on the educational applications of new technologies. Thus, higher education institutions should support their faculty with appropriate technical and administrative resources and support that will promote the effective infusion of emerging technologies into teaching and learning. The provision of high quality professional development, in particular, emerged as vital for generating the necessary changes in teaching cultures that will enable instructors, and consequently learners, to reap the full benefits of ICT advances (Meletiou-Mavrotheris et al., 2017).

To facilitate the proliferation of technology in higher education instructional settings and its use in more creative ways that can have a true impact on teaching and learning, instructors should be provided with professional development opportunities that bring innovative technologies to the forefront of their consciousness, and facilitate their integration into instructional practices in more effective ways. Educators should be helped to recognize how, rather than using technology as an “add-on” to existing teaching and learning activities, they should use it in ways that transform learning by fostering deep understanding and engagement through higher-order thinking and socio-constructivist-style activities. Through familiarization with theoretical frameworks for technology integration such as Puentedura (2009) Substitution, Augmentation, Modification, Redefinition (SAMR) model and hands-on experimentation with new and emerging technologies and their educational affordances, they should acquire skills and dispositions that will allow them to use technology not only as a direct tool substitute (with or without functional change), but as an enabler for significant task redesign, or even for the creation of new tasks that were previously inconceivable.

Responding to the end-user needs identified by the RELOBIE study, four of the five institutions comprising the RELOBIE consortium (Åbo Akademi, Coimbra University, European University Cyprus, Tartu University), in collaboration with Denmark’s Aarhus University, proposed and succeeded in obtaining EU funding for a follow-up project titled PLAY&LEARN DIGIMEDIA - Playful Learning Experience - Enhancing adult education and learning environments with digital media (Ref. #: 2016-1-FI01-KA204–022757). The PLAY&LEARN DIGIMEDIA project, which lasted for 33 months (September 2016-May 2019) utilized findings from the RELOBIE study to design and implement high quality online teacher training aimed at developing and expanding competencies of higher/adult educators in ICT-enhanced instruction. The main outcome of the project is an online course, offered as a MOOC that provides educators with new tools and concrete support for using digital media more extensively and effectively in instruction, so as to improve students’ motivation and learning outcomes. The MOOC was pilot tested in Spring 2019, and was attended by more than 500 participants around Europe. After being pilot tested and revised based upon received feedback, the course material was released and is currently available for independent study by anyone interested: https://open-tdm.au.dk/blogs/pld.

Individual partners also utilized findings from the RELOBIE study and, subsequently, the outputs of the Play and Learn DigiMedia project, to improve their methods of teaching, learning, and assessment to more closely align with the affordances of new technologies. At European University Cyprus, for example, several measures have since been taken by the University to support faculty with appropriate technical and administrative resources that promote the effective infusion of emerging technologies into teaching and learning (Meletiou-Mavrotheris et al., 2018, see also DEL mentioned above). These included both centralized collective efforts as well as individual efforts that targeted particular courses, and/or faculty members. The involvement of members of the faculty with scientific background in ICT in education supporting all instructors in the design and development of their courses in an interactive online learning environment was proven invaluable. Emphasis was given on the added value of integrating technology and the use of videos especially with respect to recording classes and employing teleconferencing in the teaching and learning process (Meletiou-Mavrotheris et al., 2018). Similar initiatives aimed at the promotion of digitally enhanced learning took place in many other HEI across the globe. Overall use of technology-enhanced learning has grown over the recent years in a number of HEI worldwide.

Concluding Remarks: New Challenges, New Era in the COVID-19 Pandemic and Beyond

Current data and reports of the higher education response and situation during the COVID-19 pandemic (IAU, 2020; UNITWIN/UNESCO, 2020) provide evidence on the relationship between universities’ prior experiences and established digital enhanced learning policies and practices to their readiness for emergency teaching response. Existing mechanisms, policies and practices in Higher Education Institutions such as those described in the previous paragraph, have been strongly tested during the COVID-19 pandemic period in 2020, where globally universities’ closure to contain the spread of the virus, forced instructors of conventional programs to turn, within a matter of days, their courses into digitally enhanced, and to offer them at-distance in order to minimize learning disruptions. The communities of learning empowered for both students and academics, which were already in place, as in the case of EUC (Louca, 2020), and the digital culture created since then, have proved valuable for instructors to devise solutions with the use of technology, and facilitated the shift from conventional to online classes fast and effectively, despite the unprecedented challenges posed by the emergent situation.

Despite the rich insights gained from the current study, more research is needed to further advance our understanding of higher education instructors’ attitudes and levels of educational use of technological tools and applications. A drawback of this study is the limited generalizability of its findings due to the self-selected nature and relative small size of the survey sample. To enable generalizations beyond the specific research setting, future iterations of the survey study ought to employ more rigorous sample selection procedures. Future effect studies taking place in actual classroom settings (face-to-face, blended, or online) are also essential to help shed light into both facilitating and inhibiting factors to the successful implementation of technological tools in formal learning settings. Research focusing on the actual integration of various technological tools, can provide a more holistic picture of faculty members’ processes of adopting and implementing technology in teaching and learning. It can also offer faculty with valuable information on how to best utilize the affordances provided by ICT to motivate their students, and to scaffold and extend their learning.

Findings of the current study indicated that a sizable proportion of the instructors in both the Conventional and Online Group felt that they are experienced with technology, but lacked relative sophistication. Findings also showed that, for almost one-fifth of the instructors in the Conventional Group sample, use of technology was optional in their courses, or they made no use of technology at all. It would be interesting to see how such a position and view might have changed for the Conventional Group after the implementation of projects and initiatives, such as the DEL project at EUC, as well as after all instructors have been forced by unpredictable situations, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, to rapidly digitalize their teaching practices, and to provide full online learning experiences to their students. It is indeed admirable how such situations can lead to a shift of not only practices but also pedagogies and methodologies that academics might have never thought of in the past. However, it would be interesting to investigate the long-term impact of this “forced” shift, due to the need of immediate response, and the sustainability of such practices, not only by instructors themselves but also by institutions.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the conception and design of the study, and to the data collection process. The first author organized the data and performed the statistical analyses, with help from the other two authors. All authors contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. They all read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was funded by the EU, under the Erasmus + Key Action two program RELOBIE: Reusable Learning Objects in Education (Ref. #: 2014-1-FI01-KA200-000831). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations presented in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the EU.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution in the data collection process of their RELOBIE project partners Pekka Tenhonen, Mona Riska, Maria Sundstrom, and Lehti Pilt.

References

Abe, P., and Jordan, N. A. (2013). Integrating social media into the classroom curriculum. About Campus 18, 16–20. doi:10.1002/abc.21107 Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/abc.21107 (Accessed May 1, 2020).

Aijan, H., and Hartshorne, R. (2013). Investigating faculty decisions to adopt Web 2.0 technologies: theory and empirical tests. Internet Higher Educ. 11, 71–80. doi:10.1016/j.iheduc.2008.05.002

Al Nashash, H., and Gunn, C. (2013). Lecture capture in engineering classes: bridging gaps and enhancing learning. Educ. Technol. Soc. 16 (1), 69–78.

Allen, I., and Seaman, J. (2014). Grade change: tracking online learning in the United States. Wellesley, MA: Babson College/Sloan Foundation.

Anderson, L. W., and Krathwohl, D. R. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: a revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. New York, NY: Longman.

Anderson, J. Q., Boyles, J. L., and Rainie, L. (2012). The future impact of the Internet on higher education: Experts expect more-efficient collaborative environments and new grading schemes; they worry about massive online courses, the shift away from on-campus life. Washington, D. C.: Pew Research Center's Internet and American Life Project.

Andersson, Α., Hatakka, M., Grönlund, Å., and Wiklund, Μ. (2014). Reclaiming the students–coping with social media in 1:1 schools. Learn. Media Technol. 39, 37–52. doi:10.1080/17439884.2012.756518

Aparicio, M., Bacao, F., and Oliveira, T. (2016). An e-learning theoretical framework. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 19 (1), 292–307.

Baxter, G. J., Connolly, T. M., Stansfield, M. H., Tsvetkova, N., and Stoimenova, B. (2011). “Introducing Web 2.0 in education: a structured approach adopting a Web 2.0 implementation framework,” in Proceedings of the 7th international conference on next generation web services practices, Salamanca, Spain, October 19–21, 2011 (IEEE), 499–504.

Bishop, J., and Verleger, M. (2013). The flipped classroom: a survey of the research. Atlanta, Georgia: American Society for Engineering Education National Conference Proceedings.

Blayone, T. J. B., vanOostveen, R., Barber, M., and Childs, E. (2017). Democratizing digital learning: theorizing the fully online learning community model. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High Educ. 14 (13), 1–16. doi:10.1186/s41239-017-0051-4

Bolliger, D. U., and Martin, F. (2018). Instructor and student perceptions of online student engagement strategies. Distance Educ. 39 (4), 568–583. doi:10.1080/01587919.2018.1520041

Center on Online Learning and Students with Disabilities (COLSD) (2016). Equity matters: digital & online learning for students with disabilities. Lawrence, KS: Author.

Dahlstrom, E., and Brooks, D. C. (2014). ECAR Study of Faculty and information technology, 2014. Louisville, CO: ECAR.

Duffy, P. (2008). Engaging the YouTube google-eyed generation: strategies for using Web 2.0 in teaching and learning. Electron. J. e-Learning 6 (2), 119–130.

Dysart, S., and Weckerle, C. (2015). Professional development in higher education: a model for meaningful technology integration. J. Inf. Technol. Educ. Innov. Pract. 14, 255–265.

Eick, C., and King, D. T. (2012). Non science majors’ perceptions on the use of YouTube video to support learning in an integrated science lecture. J. Coll. Sci. Teach. 42 (1), 26–30.

Hoogerwerf, E. J., Mavrou, K., and Traina, I. (2020). The role of assistive technology in fostering inclusive education: strategies and tools to support change. London, United Kingdom: Routledge.

Elliott, C., and Neal, D. (2016). Evaluating the use of lecture capture using a revealed preference approach. Active Learn. Higher Educ. 17 (2), 153–167. doi:10.1177/1469787416637463

Ertmer, P. A., Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A. T., Sadik, O., Sendurur, E., and Sendurur, P. (2012). Teacher belie fs and technology integration practices: a critical relationship. Comput. Educ. 59 (2), 423–435. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2012.02.001

European Commission (2014). Report to the European Commission on new modes of learning and teaching in higher education. Available at: https://www.teachingandlearning.ie/publication/report-to-the-european-commission-on-new-modes-of-learning-and-teaching-in-higher-education-insight-for-students/ (Accessed May 1, 2020).

Ford, M. B., Burns, C. E., Mitch, N., and Gomez, M. M. (2012). The effectiveness of classroom capture technology. Active Learn. Higher Educ. 13 (3), 191–201. doi:10.1177/1469787412452982

Georgina, D. A., and Olson, M. R. (2018). Integration of technology in higher education: a review of faculty self-perceptions. Internet Higher Educ. 11 (1), 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.iheduc.2007.11.002

Gill, R. (2011). Effective strategies for engaging students in large-lecture, nonmajors science courses. J. Coll. Sci. Teach. 41 (2), 14–21.

Goodyear, V. A., Casey, A., and Kirk, D. (2014). Tweet me, message me, like me: using social media to facilitate pedagogical change within an emerging community of practice. Sport Educ. Soc. 19 (7), 927–943. doi:10.1080/13573322.2013.858624

Govindarajan, V., and Srivastava, A. (2020). What the shift to virtual learning could mean for the future of higher. Available at: https://hbr.org/2020/03/what-the-shift-to-virtual-learning-could-mean-for-the-future-of-higher-ed (Accessed May 1, 2020).

Guy, R., and Marquis, G. (2016). Flipped classroom: a comparison of student performance using instructional videos and podcasts versus the lecture-based model of instruction. Iisit 13, 001–013. doi:10.28945/3461

Hagler, B. (2013). Value of social media in today’s classroom. J. Res. Business Educ. 55 (1), 14–23.

Hargis, J. (2020). What is effective online teaching and learning in higher education? Academia Lett., 13. https://doi.org/10.20935/AL13

Herrero, R., Bretón-López, J., Farfallini, L., Quero, S., Miralles, I., Baños, R., et al. (2015). Acceptability and satisfaction of an ICT-based training for university teachers. Educ. Technol. Soc. 18 (4), 498–510.

IAU (2020). Regional/national perspectives on the impact of COVID 19 on higher education. 978-92-9002-211-4.

Jaschik, S., and Lederman, D. (2013). The 2013 inside higher ed survey of faculty attitudes on technology. Washington, DC: Inside Higher.

Jaschik, S., and Lederman, D. (2019). The 2019 inside higher ed survey of faculty attitudes on technology, a study by inside higher ed and gallup. Mediasite.

Junaidu, S. (2008). Effectiveness of multimedia in learning and teaching data structures online. Turkish J. Distance Educ. 9 (4), 97–107.

Kahn, B. H. (1997). “Web-based Instruction (WBI): what is it and why is it?,” in Web-based instruction. Editor B. Kahn (Engelwood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology), 5–18.

Kear, K., and Rosewell, J. (2018). “Excellence in e-learning: the key challenges for universities,” in The envisioning report for empowering universities (p20-23), European association of distance teaching universities (EADTU). Editors G. Ubachs, and L. Konings. Maastricht, NL: EADTU. Available at: https://tinyurl.com/envisioning-report

Kumar, J. A., Bervell, B., and Osman, S. (2020). Google classroom: insights from Malaysian higher education students” and instructors” experiences. Educ. Inf. Technol. 25, 4175–4195. doi:10.1007/s10639-020-10163-x

Laurillard, D. (2013). Rethinking university teaching: a conversational framework for the effective use of learning technologies. London, United Kingdom: Routledge.

Lei, L., Finley, J., Pitts, J., and Rong, G. (2010). Which is a better choice for student-faculty interaction: synchronous or asynchronous communication?. J. Technol. Res. 2, 1–12.

Lidof, S., and Pasco, D. (2020). Educational technology professional development in higher education: a systematic literature review of empirical research. Front. Educ. 5(35), 1–20. doi:10.3389/feduc.2020.00035

Long, T., Cummins, J., and Waugh, M. (2017). Use of the flipped classroom instructional model in higher education: instructors” perspectives. J. Comput. High Educ. 29, 179–200. doi:10.1007/s12528-016-9119-8

Louca, L. (2020). European University Cyprus: university instruction is changing radically. Available at: https://www.sigmalive.com/news/market-news/620420/europaiko-panepistimio-kyprou-i-panepistimiaki-didaskalia-allazei-rizika?fbclid=IwAR1gEzFboHyQFbQgUYPjEKkA4zJYtj5qMoCUwTQPvznIH6uevgORtaypSEw (Accessed May 1, 2020).

Mandernach, B. J. (2009). Effect of instructor-personalized multimedia in the online classroom. Int. Rev. Researching Open Distance Learn. 10 (3), 1–19. doi:10.19173/irrodl.v10i3.606

Marzilli, C., Delello, J., Marmion, S., McWhorter, R., Roberts, P., and Marzilli, T. S. (2014). Faculty attitudes towards integrating technology and innovation. Ijite 3 (1), 1–20. doi:10.5121/ijite.2014.3101

McDonald, P., L., Lyons, L. B., Straker, H. O., Barnett, J. S., Schlumpf, K. S., Cotton, L., et al. (2014). Educational mixology: a pedagogical approach to promoting adoption of technology to support new learning models in health science disciplines. Online Learn. 18 (4), 1–18. doi:10.24059/olj.v18i4.514

Meletiou-Mavrotheris, M., and Koutsopoulos, K. (2018). “Projecting the future of cloud computing in education: a foresight study using the delphi method,” in Educational design and cloud computing in modern classroom settings. Editors K. Doukas, and K. C. Koutsopoulos (Hershey, PA: IGI Global), 262–290.

Meletiou-Mavrotheris, M., and Mavotheris, E. (2007). Online communities of practice enhancing statistics instruction: the European project earlystatistics. Electron. J. e-Learning 5 (2), 113–122.

Meletiou-Mavrotheris, M., Mavrou, K., Chatzipanayiotou, P., and Vryonides, M. (2018). Taking digital teaching and learning seriously at European University Cyprus. Int. J. Euro-Mediterranean Stud. 11, 49–56.

Meletiou-Mavrotheris, M., Mavrou, K., Vaz-Rebelo, P., Santos, S., Tenhonen, P., Riska, M., et al. (2017). “Technology adoption in higher education: a cross-national study of university faculty perceptions, attitudes, and practices,” in Technology-centric strategies for higher education administration. Editors P. Tripathi, and S. Mukerji (Hershey, PA: IGI Global), 295–317.

Mintz, S. (2013). The future is now: 15 innovations to watch for. Washington, D.C: The Chronicle of Higher EducationAvailable at: http://chronicle.com/article/The-Future-Is-Now-15/140479 (Accessed May 1, 2020).

Oliver, R., and Herrington, J. (2000). “Using situated learning as a design strategy for web-based learning,” in Instructional and cognitive impacts of web-based education. Editor B. Abbey (Hershey, PA: Idea Publishing group), 178–191.

Panther, B. C., Mosse, J. A., and Wright, W. (2011). “Recorded lectures don’t replace the “real thing”: what the students say,” in Proceedings of the Australian conference on science and mathematics education 2011. Editors M. Sharma, A. Yeung, T. Jenkins, E. Johnson, G. Rayner, and J. West (Sydney, NSW: UniServe Science), 127–132.

Puentedura, R. R. (2009). SAMR and TPCK: intro to advanced practice. Ruben R. Puentedura’s Weblog. Available at: http://hippasus.com/resources/sweden2010/SAMR_TPCK_IntroToAdvancedPractice.pdf (Accessed May 1, 2020).