- Department of Foundation of Education, College of Education, UAEU, Al Ain, United Arab Emirates

After the enactment and implementation of a series of inclusive education policies in the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and worldwide, a number of challenges have hindered the effective implementation of these policies. The current study investigated the conditions of inclusive schools in the context of the UAE and focused on examining the role of school principals in promoting inclusive schools in the city of Al Ain, UAE. A qualitative research design was employed using a phenomenological approach. A semi-structured interview protocol was used to gather data from the participants. A total of 10 special education and general education teachers, five from public schools and five from private schools, participated in the study. The qualitative data was then refined and analyzed using thematic analysis. The findings demonstrated the key role of principals in creating and promoting inclusive schools when considering the factors that affect the inclusion of students of determination (SODs), referring to students with special needs, and when implementing effective inclusive practices in schools. Principals’ awareness of inclusive education emerged as a significant factor in creating and promoting inclusive schools. These findings shed light on conditions that could promote inclusive schools in the UAE context and increase policymakers’ and practitioners’ in acknowledging the key role played by principals in the effective implementation of inclusive schools. The study recommended a systematic provision of professional development, targeting the enhancement and improvement of principals’ awareness of inclusive education and schools.

Introduction

Principals are considered key actors responsible for operating and directing all administrative functions of schools successfully and effectively. They have significant responsibilities in maintaining the effective internal functioning of school systems, representing the school in the community, and implementing educational policies with precision. Principals also act as role models who improve the ethical and professional growth of teachers and other professional staff. Ultimately, principals have an indirect but significant influence on students’ learning by fulfilling their diverse needs and abilities and legislating and establishing school systems and policies (Leithwood and Jantzi, 2008).

Dyal et al. (1996) noted that a school principal plays a vital role in forming an educational climate, which provides learning opportunities for all students, including those with disabilities. They further explained that a principal could build a community of learners or allow classrooms, students, and teachers to act autonomously and reported that school principals’ attitudes, roles, relationships, and visions are active parts of an inclusive school environment. Moreover, the authors noted that principals need to follow several steps to facilitate the creation of inclusive schools, writing a strong mission statement for the success of all children, which relies on the principals’ sense of responsibility, an initial step toward an inclusive school. Similarly, Cohen (2015) claimed that a school principal is the most key agent of change in a school, as they are the central actor who contributes to the creation and promotion of a successful inclusion program.

Inclusive schools involve children with special needs in general classrooms and allow these students to interact and socialize with their peers in general education (Jackson et al., 2000; Hussain, 2017). According to Jackson et al. (2000), inclusive education refers to the use of the inclusion method in education to generate a new type of education characterized by incorporating students with disabilities into classes at regular schools. Notably, all students benefit from significant, challenging, and appropriate educational elements and separated teaching methods that address their unique abilities and needs.

The Government of the United Arab Emirates (UAE) initiated an inclusive school program called “School for All” in 2006 under Federal Law No. 29, which adopted the concept of inclusive education to ensure that all learners with disabilities, called students of determination (SODs), have the right to access educational opportunities in public and private schools and all other educational institutions in the UAE (Hussain, 2017). The Abu Dhabi Department of Education and Knowledge (ADEK) considers education to be a human right, including people of determination. The ADEK enforces legislation and policies and presents initiatives that guarantee the full inclusion of people of determination in the system of regular schools and that their social skills and linguistic development start in early childhood (ADEK, 2020). Mariam Al Qubaisi, the head of special needs, reported that the goal was to fully implement inclusion in the UAE by 2015. She indicated that inclusion is the responsibility of society and emphasized the significance of integrating SODs in schools and the opportunities that can be provided to them (Bell, 2015). Despite significant progress, the goal of reaching full inclusion throughout the country has not yet been reached.

There are significant challenges to ensuring that each individual obtains an equal opportunity for educational progress worldwide (UNESCO, 2019). SODs might confront many obstacles during the transition and adaptation processes in regular school settings. These students need special care and treatment as well as modified curriculum and instruction that meet their needs and expectations. The absence of these modifications results in several challenges for SODs, which might include having negative attitudes toward inclusion, lack of qualified educators, insufficient training courses, and large sizes of classes (Konza, 2008). Thus, in inclusive schools that integrate SODs with other typical students, the role of school principals remains critical yet challenging even after the initiation of inclusiveness (Riehl, 2000).

Hoppey and McLeskey (2013) have indicated that while policies call for inclusive education, achieving this goal remains complicated and challenging for principals. To work toward that goal, they suggested school principals should be held accountable for not only managing and organizing their schools but also promoting the inclusive learning of SOD. Principals also need to take on a number of roles to ensure that their schools are capable of offering the professional support required to teachers and other professional educators. Principals of inclusive schools should be those with the skills, knowledge, and qualities to deliver effective leadership. Without the leadership and support of the principal, schools would struggle to meet the challenging requirements of providing varied services that meet the needs of diverse student populations. Therefore, principals must be aware of the requirements of inclusive schools, which should be effectively established to support teachers and the larger school community. Finally, principals are expected to consider inclusive practices and strategies to change the culture at inclusive schools and develop learning communities in their schools (Hoppey and McLeskey, 2013).

The literature on inclusion in UAE has varied focuses. While some studies describe inclusive practices in UAE schools (Anati, 2012), others have explored different inclusion-related issues in the UAE (Alborno, 2013; Gaad and Almotairi, 2013; Alborno and Gaad, 2014). A number of studies (Alghazo and Naggar Gaad, 2004; Gaad and Khan, 2007; Dukmak, 2013; Hussain, 2017; Badr, 2019; Fakih, 2019) have considered teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion and students with disabilities as determining factors. Usman (2011) on the other hand, highlighted the attitudes of the school principal in promoting inclusion and creating a school climate. Al Neyadi (2015) focused on the parents’ attitudes as a determining factor. In the midst of these differing views, the role of school principals in creating and promoting inclusion in schools remains an area of further investigation. More specifically, issues in realizing the goals of inclusive education policies in the UAE call for a close examination of the practices and challenges encountered by principals in creating and promoting inclusive educational environments. The current study attempted to address these issues in the relevant literature. It addresses the following research questions on the role of principals in promoting inclusive schools:

1. What is the role of school principals in inclusive schools?

2. What are the main factors to be considered when including SODs in inclusive schools?

3. What are the inclusive practices needed to promote inclusive schools?

Methodology

Study Design

The current study investigated the role of school principals in promoting inclusive schools in Al Ain, UAE. The study employed a qualitative research design by focusing on teachers’ perceptions of their principals in managing and promoting inclusive schools (Byrne, 2001). the use of teachers as the main data source is expected to eliminate the bias inherent in the self-reports of principals. Teachers’ narratives were utilized to analyze, understand, and describe (Byrne, 2001) the experiences of general and special education teachers’ perceptions of their principals in promoting inclusive schools. Creswell (2012) noted that qualitative research provides researchers with more flexibility in exploring topics as they arise and can allow participants to form their research direction and share their opinions freely. The qualitative nature of the study provided an opportunity to develop a comprehensive understanding of practices and challenges in inclusive education in the context of UAE. More specifically, this study employed a phenomenological method to explore and describe the lived experiences of teachers which can lead to the interpretation of the facts related to the principals’ practices in schools (Byrne, 2001). Teachers’ qualitative narratives were collected through semi-structured interviews, which addressed the themes identified by the study’s research questions.

Instrumentation

Semi-structured interviews were the primary tool for data collection. The semi-structured interview protocol allowed the researchers to include a structural element. The participants had the opportunity to share their views regarding the inclusive leadership practices that interested them (Bryman, 2004) and explore inclusive education topics in detail (Kvale and Brinkmann, 2009). As mentioned previously, the interview questions were derived from the study’s main research questions which considered three major areas. First, teachers’ perceptions about the role of their principals in promoting an inclusive school were investigated. Second, teachers’ perceptions of the factors that affect the learning and adaptation of SOD’s in schools were studied. Finally, we examined the strategies and practices that the teachers believe that their principals need in creating and promoting inclusive schools. Therefore, each study question was split into three sub-questions that could provide detailed information related to these areas. For instance, the first interview question was concerned with the role of school principals in inclusive schools and included the following sub-questions:

1. What was your first impression about inclusion in our schools and why?

2. To what extent do you believe that SODs are accepted and included at your school?

3. Do you think the school principal plays a major role in making this program successful and why?

Prior to the interviews, each participant received a consent form with the ethics of the interview and confidentiality. It illustrated their right to withdraw before or during the interviews; their freedom to answer or skip any question, their right to drop out of the study anytime, and that the collected data and information will be used only for the study purpose and kept confidential based on the ethical conditions.

The interviews were conducted in January and February 2020 by the three researchers at places and times (schools, phone calls, etc.) convenient to the participants. The duration of each interview was 20–30 minutes. The interviews were recorded and then transcribed to facilitate data collection and analysis. The interview questions were reviewed by reviewers to guarantee authentic, reliable answers from the participants. Moreover, while conducting the interviews, additional explanations were provided to the interviewees when required. The interviews were transcribed with the help of experienced English teachers and then were reviewed by the researchers to ensure data accuracy. Furthermore, a pilot interview was conducted before data collection to ensure that the interview questions were applicable and help estimate the length of the interview. The initial investigation of these pilot studies helped the researcher ensure the instrument’s quality and organization (Gall et al., 2007).

Sample and Population

The sample of the study was selected from a population of private and public school teachers in Al Ain, that is, those who were accessible to the researchers and had interacted with and taught SODs in regular inclusive schools. The participants were selected according to the study’s primary goal (Morse, 1991) and to obtain rich information from those participants who can provide it and are suitable for detailed research (Patton, 2002). Criterion sampling also was employed to select the participants who fulfilled the criteria for participation in this study. Thus, the selected participants were:

• general or special education teachers who taught SODs;

• teachers with more than one year of experience teaching SODs;

• general education teachers of different subjects and grade levels;

• teachers from Al Ain schools.

The initial total number of participants who met the above criteria was 15. However, five participants refused to take part after considering the confidentiality terms and ethical considerations. Accordingly, 10 participants (five special education teachers and five general education teachers) volunteered to participate. As the samples in qualitative studies have usually been small and relied on information needs (Maxwell, 2005), the number of participants was limited to the 10 teachers who consented to participate and who could provide detailed and in-depth data.

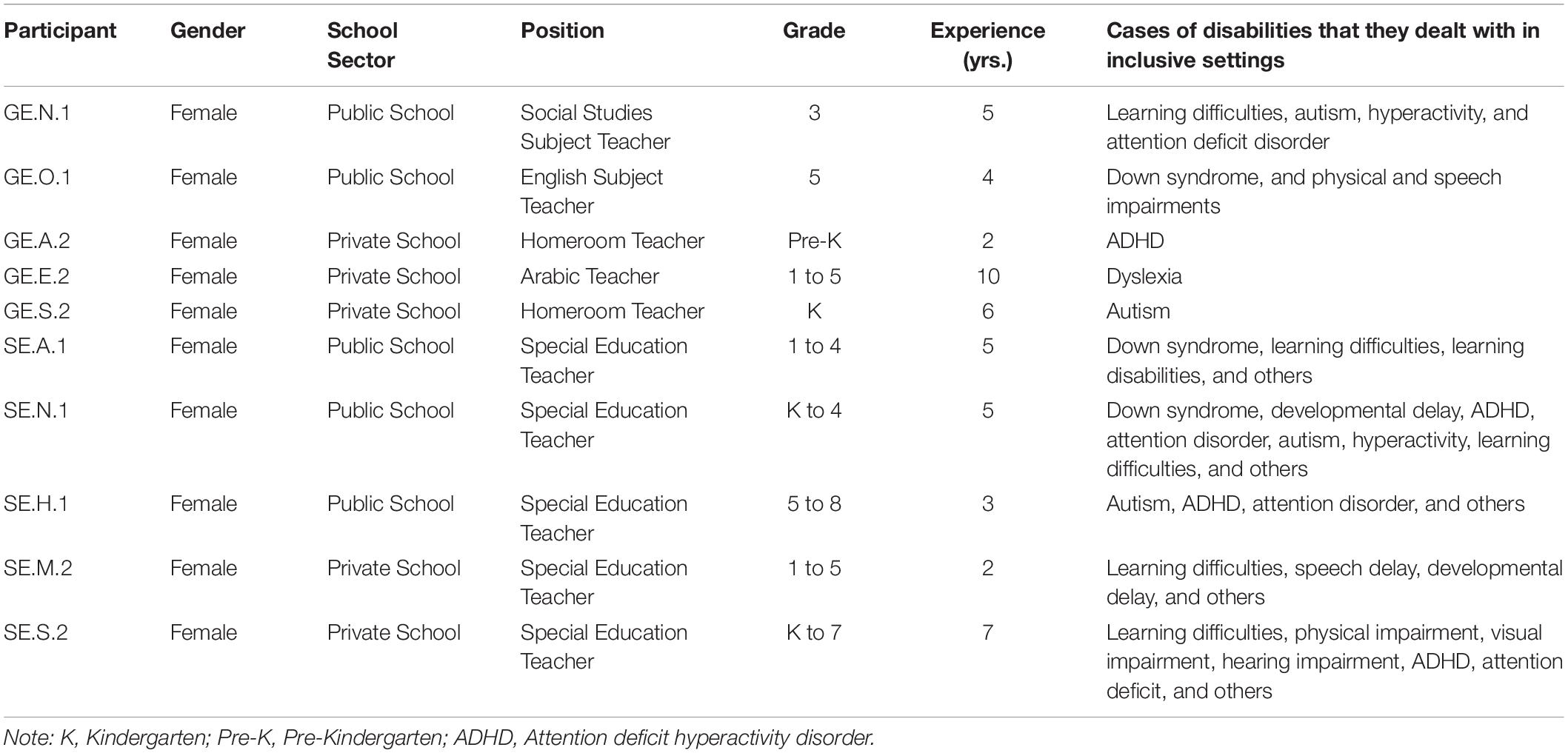

Data was collected from teachers who teach SODs, as they are typically aware of the factors that affect these students in regular schools. Because teachers work in schools, they provide realistic, precise data on their school principals’ role and the practices they might apply to promote inclusive school systems. The study represented the participants, who were classified into four groups, using abbreviations that comprised coded letters and numbers. General education teachers were named GE, and special education teachers were named SE. Those abbreviations were followed by the first letter of each participant’s name and then a number, where one refers to public schools and two refers to private schools. For example, the code GE.N.1 refers to a general education teacher from a public school and GE.A.2 refers to a general education teacher from a private school. The same was applied to the special education teachers’ codes. The 10 participants’ information is summarized in Table 1.

Data Analysis

The researchers conducted an initial evaluation of the interview transcripts to check their validity and contribution to the study and obtain a deep understanding as the first step in data analysis. The 10 interview transcripts were read thoroughly and assessed for their completeness by the researchers. After determining that the collected data sufficiently answered the main study questions, the researchers used thematic analysis to facilitate the analysis of these data. As Guest et al. (2014) suggest, thematic analysis is the most convenient method used to understand the complexity of the underlying meaning in texts. It is also the most common method used in qualitative data analysis. Vaismoradi et al. (2016) emphasized that thematic analysis can be defined as a set of techniques and methods used to analyze textual data and illustrate themes. This method is a systematic process that begins with coding and examining meanings and the description’s provision of social realities, which contribute to creating a theme that describes and interprets the perspectives of participants (Vaismoradi et al., 2016).

The data analysis procedure was accomplished by one of the researchers. The researcher followed a coherent set of approaches to analyze and interpret the collected data thematically using thematic analysis. First, reading and diagnosing helped the researcher familiarize themself with the data and understand the overall picture. Second, a thorough reading was conducted to start the coding by highlighting and summarizing the frequent and common data under each question into main groups. Third, the coded data or groups were generalized and turned into themes for broader identification. The odd and infrequent codes, which did not benefit the study, were disregarded. Fourth, two main themes that answered each study question were generated from these codes. Therefore, these themes represented and summarized the study’s main findings. Fifth, the generated themes were reviewed to ensure their effectiveness and accuracy in representing the desired findings. Sixth, the generated themes were redefined and named to easily convey their meanings and be understood by the reader. Finally, the researcher narrated and addressed these themes supported by the responses of some participants under three main sections, according to the study’s three main questions, in the results section below.

Results

This section presents major findings and themes based on the collected qualitative data.

The Role of School Principals in Inclusive Schools

The first research question investigated the teachers’ perspective of the role of the principal in inclusive settings. The following two themes were retrieved, which highlighted the role of school principals in promoting inclusive schools using teachers’ perspectives.

Principals’ Attitude Toward Inclusion

The first theme implied that the school principal’s support and attitudes toward inclusion have a substantial impact on teachers’ attitudes. The principals’ support clearly could affect the participant teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion. Five participant teachers reported their negative attitudes toward the inclusion of SODs because their principals did not support them. For instance, SE.M.2 explained that her principal did not pay much attention to her plans for SODs and did not support her activities. As the only special education teacher in their school, they work independently to set up individualized education plans for SODs and design modified activities for the students in their classroom. They reported, “when I plan for activities, he (the principal) doesn’t support me […] he doesn’t want to observe my work or ask about these students (SODs).”

However, the other four participant teachers expressed positive attitudes toward SODs because of their school principals’ positive attitudes and care. Their principals provided them the resources required and supported them and the students likewise. For instance, GE.N.1 commented about their school principal’s engagement with SODs and the care provided for these students. This principal visited SODs in their classrooms and asked the teachers whether they required any support for their activities for SODs. The participants outlined, “my principal likes them (SODs) and cares for them. From the beginning of the year, my principal visits each classroom to meet those students, and to observe them […]. She communicates with other special education teachers to help these students.” GE.N.1 added the importance of holding regular meetings by the principal with the special education teachers to discuss the progress of SODs and the needs of these students. She stated that the principal “holds regular meetings with special education teachers and assistants to discuss how to improve SODs’ learning.” This principal focused more on the needs of these students. The participant emphasized the critical role that a school principal can play by caring for SODs. They noted that “if the principal cares, all staff in the school, like special and general education teachers and assistants, will work cooperatively to help these students (SODs).”

Principals’ Actions and Behavior

The second theme focused on the role of school principals’ actions and behaviors toward inclusion. On the one hand, some principals in private schools in Al Ain, as perceived by teachers, disregard the admitted SODs’ rights and basic needs in their schools. SE.S.2 shared the situation in her private school saying that her principal admits SODs, even though they lack the budget and facilities and which explains why they fail in supporting these students. She explained, “She (the principal) accepts the idea of inclusion, although, we have problems in the budget in private schools […] we cannot provide the facilities and services for these students (SODs).” SE.M.2 also highlighted the significance of the role of the principal in providing and supporting school activities for SODs. They reported the absence of the school principal’s attention to SODs’ plans and the lack of support and budget dedicated to providing activities suitable for them. SE.M.2, as the only special education teacher in the school, plans for SODs and prepares activities for them inside her classroom. As highlighted above, she said: “When I plan for activities, he (the principal) doesn’t support me.” She added: “I have to contain activities for these students (SODs) only within my classroom […] from my own budget […] he doesn’t appreciate my work or ask me anything about them (SODs).” These responses provide a clear picture of the principals’ lack of attention to the rights and needs of SODs in some private schools.

On the other hand, the results showed that some principals in public schools in Al Ain promote inclusion by assigning learning support teams to support SODs. Participant teachers from public schools expressed how their school principals enable them to support SODs. SE.A.1 and SE.N.1 had positive feedback on their school principals’ practices that support the inclusion of SODs. SE.A.1 said, “Every Tuesday, we have activity lessons. Our principal allows SODs to participate in these activities, art, music […] according to their interests.” She added: “Also, we have programs for them […] some autistic children like drawing, or making computer programs […] the principal allows them to attend IT lessons.” SE.N.1 also expressed her school principal’s role in facilitating the school environment and enacting rules that protect SODs. She claimed that her school principal legislates strict rules and facilitates the school environment to welcome those students. She said, “In our school, the principal always tells us to take care of SODs, she manages the rules […] and she follows up […] she made the school environment suitable for them.” She and SE.H.1 reported that the learning support team is led by their principals to support SODs. SE.N.1 said, “She (the principal) takes good care of them (SODs). And she is the leader of our support team.” SE.H.1 also shared the positive role of her school principal. She explained, “She (the principal) meets the learning support team to know the cases of students (SODs) we have […] their social status, medical status, academic performance, and the difficulties they encounter in the school […] and what we did to solve their problems.”

All of the aforementioned highlight the role of school principals in inclusive schools represented in a principal’s attitude and behavior toward SODs and their inclusiveness and which, in turn, can affect the teachers’ acceptance of inclusion and SODs.

Main Factors to Be Considered When Including Students of Determination

The second research question identified the main factors to be considered when including SODs in inclusive schools as suggested by teachers. Two primary themes were retrieved and they highlighted the inclusive factors that, teachers believe, affect SODs’ inclusion in regular schools.

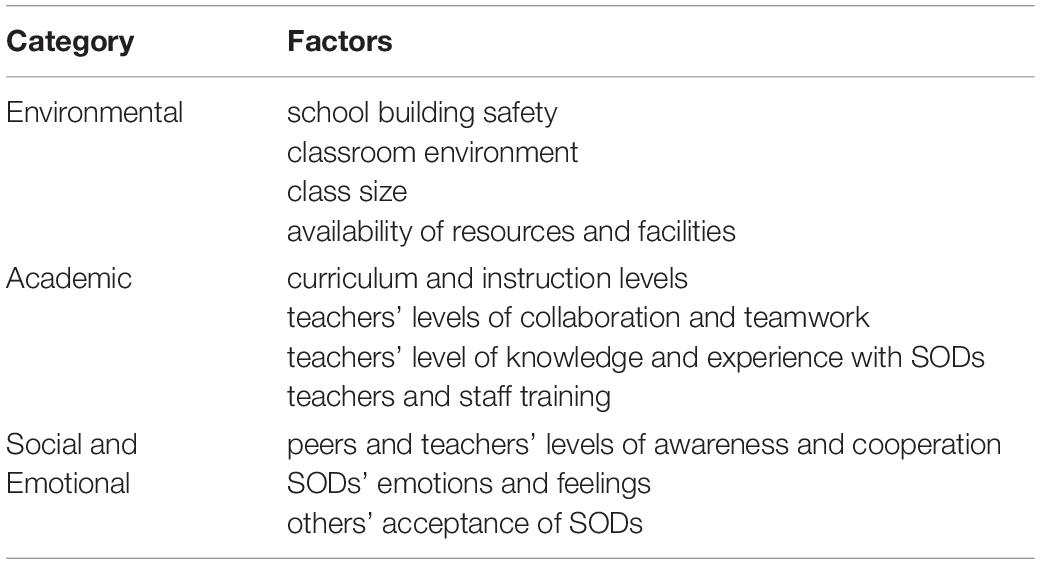

Internal School-Based Factors

The first theme referred to the internal school-based factors, which directly affect SODs in inclusive schools. These factors were classified as environmental, academic, and social, and emotional factors. These factors were confirmed by the participant teachers to influence the success of SODs’ inclusion in regular schools and classrooms. The researchers summarized and categorized these factors into three major categories displayed in Table 2.

Table 2. Categories of internal school-based factors that affect the inclusion of students of determination.

Experienced special education teachers SE.H.1 and GE.O.1 addressed excellent examples of environmental factors affecting SODs’ adaptation in regular schools. SE.H.1 highlighted the importance of a safe school building and classroom environment. She stated: “First, the safety inside the classroom and the environment, how it is set, the brightness, the colors […] and the safety of the classroom settings.” GE.O.1 emphasized the importance of class size and availability of facilities. She stated, “the class number […] if the class is very big, for one teacher, it is very difficult to deal with the students, because they need special attention and even the other students need special attention.” She emphasized the importance of the availability of facilities in the classroom, explaining, “Even the facilities. If teachers need special devices or special resources for them (SODs) […] it will be very difficult to deal with those students without them.”

Academically, SE.M.2 mentioned that the high level of the school curriculum cannot meet all SODs’ academic level, which makes it harder for them to adapt to the regular classroom. She clarified, “The curriculum is hard for them…their grades are low, we always need to keep them in separate classes during exams to read for them and explain the questions.” Collaboration and teamwork could be other factors that can solve many problems and help raise school communities’ knowledge about SODs they deal with when it is shared by knowledgeable people. SE.S.2 confirmed that general and special education teachers should work together to enhance SODs’ learning by preparing their plans and following up with them collaboratively. She said that students who need extra support should have pull-out lessons to support their learning outside the general classroom. She clarified, “when it comes to their learning […] we, special education teachers, have to meet general education teachers on a weekly basis to discuss SODs’ plans with them and to discuss their needs and the activities they need.” She added, “Sometimes, they (SODs) need external assistance outside the classroom […] we can provide that […] this will enhance their learning or performance.”

Teachers’ levels of knowledge and experience with SODs are factors that affect SODs academically. Data showed that the general education teachers interviewed did not have any knowledge or training before teaching SODs in public and private schools. GE.O.1, from a public school, expressed that her first experience in teaching SODs was particularly hard as she did not have enough knowledge about SODs. She explained, “As a general education teacher, I didn’t gain any experience in how to deal with my students (SODs), and it was the first time I deal with them.” When discussing private schools, GE.A.2 stated that they had faced the same issue, when she mentioned the little knowledge she had, which she gained earlier in one of the university courses. She clarified, “I had one course only in my bachelor studies about teaching diverse students […] which is like a drop in an ocean […] there are many cases (of SODs) and they need many years to learn how to deal with them.” GE.S.2 agreed with what the other teachers explained and emphasized the importance of other academic factors: teacher and staff training. She explained, “This (training) was missing […] if they gave me more information […] or PDs (Professional Development) in the beginning, this would have helped me […] they (principals) should put the right base from the beginning.”

SE.H.1 highlighted some social and emotional factors saying, “The teachers’ acceptance of having SODs in their classrooms […] peers cooperation […] SODs’ emotions and feelings […] others’ acceptance for them […] the awareness of school members, teachers, and administrators.” On the other hand, GE.N.1 stressed the significance of emotional factors on SODs. She provided vital examples of the importance of both the principals’ and teachers’ levels of acceptance and care for SODs that can affect the student emotionally. GE.N.1 confirmed that once SODs feel welcome and accepted in the school, this can eventually affect their adaptation, performance, and learning inside the classroom positively. She emphasized, “In my school, all SODs know the principal, they love her […]. If anything happens to them, they go to her office and talk to her.” She also stressed the matter of teachers’ acceptance, explaining that “some teachers don’t like to have SODs in their classroom because they believe they cause more work and troubles to them, which does not allow them to conduct lessons normally.” Finally, GE.N.1 concluded the importance of this emotional factor saying, “If teachers like the students and accept them […] they will feel comfortable, but if they don’t […] the students will feel the unlikeness […]. If principals and teachers accept these students, I think the other students […] will do so.”

External School-Based Factors

The second theme included external school-based factors which, participant teachers believed, can affect SODs and inclusive schools from outside the school premises. These were about the impact and engagement of the students’ families, the policies and legislation of the school district, and external diagnosing centers. Participant GE.E.2 mentioned the impact of families in the form of their level of care, their follow-up, and engagement in the inclusion process and their children’s progress. She stated, “I think the first factor […] is the student’s (SOD’s) family […] if his family doesn’t support him or give him […] attention, and take him to centers that help him improve […] it will not help him.” Similarly, SE.H.1 agreed to this external factor and added other crucial factors such as the role of school districts in enacting decisions and policies related to SODs (i.e., the permitted cases for admission, the percentage of SODs included, etc.) and diagnosing centers. She said, “Parents’ level of cooperation […] the ministry of education’s decisions also impacts SODs’ learning […]. Recently, they took out students with hearing impairment from regular schools […] also the centers […] that provide diagnosis […] and support.”

Promoting Inclusive Schools

The results were generated based on the third question highlighted two main themes. The first is that inclusive practices should be considered by principals as a way to promote the inclusion of SODs. The second relates to the importance of a principal’s willingness to support this system, as suggested by teachers. The interviewed teachers believed that these two components can effectively help promote inclusivity in regular schools.

Inclusive Practices

The first theme contained practices that were essential to promoting an effective inclusive school system. These practices were refined and classified into seven central categories based on their benefits to inclusive schools from the participant teachers’ perspective. These practices include the following:

• Hiring additional special education teachers.

• Holding regular professional development and training courses.

• Encouraging peer coaching and rewarding best practices.

• Limiting the number and types of accepted cases of SODs.

• Allocating a budget for providing SODs’ needs in terms of facilities and resources.

• Reducing class size.

• Introducing and encouraging co-teaching practices.

GE.O.1 confirmed the lack of special education teachers for English subjects and the lack of resources and facilities provided for SODs in her school. She clarified, “They (SODs) need devices depending on their disabilities […] and to provide resources so we can teach them in the classroom. And to provide extra special education teachers […] especially for English, Science, and Maths.” GE.S.2 also confirmed the same view as they have one special education coordinator for the entire school. She explained, “Instead of keeping them (SODs) with teachers who lack the needed experience to deal with them […] the principal needs to hire more special education teachers to meet SODs’ needs.”

Other participant teachers suggested encouraging peer coaching and rewarding best practices. SE.S.2 emphasized this practice along with other practices to be applied by principals saying, “Plus, sharing best practices across the school.” SE.N.2 explained, “The principal should apply a rewarding system […] or can share some teachers’ best teaching strategies […] with others […]. So, they can apply peer-coaching.”

Conversely, other participants suggested limiting both the number and the types of accepted SODs in regular schools. When asked about the main steps that school principals should apply to improve inclusive schools, GE.A.2 suggested that principals have to limit the accepted cases in their schools and conduct detailed interviews with SODs to enable awareness of their disabilities and their background from the beginning. She claimed, “Principals should carefully choose the accepted SODs […] they should conduct interviews to know their background […] because some of them might not be ready to be with people […] thus, they never behave as you wish.”

Allocating a budget for providing SODs’ need for facilities and resources is considered another major practice to be applied by principals. GE.E.2 provided an example of the absence of resources and qualified special education staff in her school. She reported, “I asked the SENCO to help me […] she gave me some paperwork, but this was not helpful […] so I tried to figure something out myself.” Similarly, with regard to public schools, GE.O.1 confirmed the need for resources saying, “They (SODs) need devices depending on their disability […] so we can teach them in the classroom […] and provide extra special education teachers […] especially for English, Science, and Maths.”

Finally, most participants emphasized the importance of reducing class size. They explained that it is not to an SOD’s advantage to be included in a crowded class with a large number of students. GE.O.1 confirmed the importance of reducing class size as she experienced the dilemma of teaching large classes that included SODs. She mentioned, “to reduce the number of students in each class if we have SODs.”

SE.S.2 also confirmed the importance of reducing class size and clarified that to have a large class, the principals need to implement a co-teaching system. She clarified, “We should encourage co-teaching strategies […] it can work well in inclusive education […]. So, the principal has to either reduce the class size or apply co-teaching.”

Principals’ Willingness for Promoting Inclusivity

The second theme implied that regardless of the school sector (i.e., public or private), the principal decides whether to facilitate or constrain inclusive strategies and practices to create better inclusive settings in the school. Participant teachers from the same school sector, whether public or private, had different responses. This indicates that school principals, regardless of their school sector, are not providing facilities or requirements in their inclusive schools at the same level. Several participant teachers agreed on the lack of qualified people who are dealing with SODs in their private schools, along with the lack of resources and services for SODs. GE.A.2 confirmed that saying, “We lack those teachers who are qualified in dealing with SODs.” She also mentioned that the plans provided by the special education coordinator are not very useful for the student; she said, “My student needs more effective planning so that he can learn […] his behavior is still the same because of the plan, which is not suitable for his needs.”

GE.E.2 also provided an example of the absence of resources and qualified special education staff in her school. She reported, “I asked the SENCO to help me […] she gave me some paperwork, but was not helpful […] so I tried to figure something out myself.” Similarly, from public schools, GE.O.1 confirmed that they lack special education teachers who teach core subjects in English along with the lack of resources and facilities for SODs. She clarified: “They (SODs) need devices depending on their disability […] so we can teach them in the classroom […] and provide extra special education teachers […] especially for English, Science, and Maths.”

However, other participant teachers referred to a group of facilities and services that are provided for SODs, with mild cases, in their schools. For instance, SE.A.1 confirmed that her principal provides the resources and facilities needed for SODs by communicating with the specialized institutions or ADEK regarding their needs. She clarified, “Our principal communicates with centers or with ADEK to ask for such types of equipment […]. We have specialists for hearing and visual impairments, and specialists for learning disabilities […] they do follow-up or check-up from time to time.” SE.N.1 also mentioned excellent examples of the provided resources and facilities in her public school for SODs. She emphasized, “We have a new building; it facilitates SODs’ movement […]. We have an elevator for the students who cannot walk […] we have three resource rooms and three special education teachers and teaching assistants to help with these students.” The former examples of facilities and services provided by principals can show how they can best serve the inclusion of SODs. These findings indicate that school principals’ willingness to promote inclusive schools is the key to implementing effective strategies and practices.

Discussion

Discussion on the Role of School Principals in Inclusive Schools

In terms of the first research question of this study, the interview results revealed that the teachers who participated believe that school principals play a major role in promoting inclusive schools with regard to two areas: their attitudes and their behavior. As the first theme suggests, school principals’ support and attitudes toward inclusion can affect teachers’ attitudes. Notably, perception of the principal’s attitude can be considered as follows: first, it is important to direct principals to apply actions that support inclusive practices; and second, this direction can influence teachers’ attitudes, thereby affecting the perception of SODs and subsequently their implementation of inclusive practices in the school. The principal’s and teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion are therefore central to supporting a well-structured and inclusive school.

In line with these findings, Horn (2011) considered this as a primary factor in promoting inclusive practices. This study outlines that because inclusion suggests that children with disabilities must be taught along with the other students in regular classrooms by general education teachers; these teachers’ beliefs and attitudes are fundamental. Once the teachers receive the required training on how to teach these students, they will feel comfortable teaching them. Moreover, teachers feel more comfortable when they are supported by school administrators, provided with resources, given time for planning, and have good communication with parents. Barnett and Monda-Amaya (1998) highlight that the school principal’s attitude toward inclusion is fundamental to the successful implementation of inclusive practices in a school. The principal’s attitude and other school members’ attitudes may be influenced by the knowledge and the training they have obtained about inclusion and the best ways to implement it (Barnett and Monda-Amaya, 1998; Horn, 2011).

This study also revealed that, as perceived by teachers, school principals’ actions and behavior in private and public schools affect the success of inclusivity. Some private schools in Al Ain admit SODs regardless of these students’ needs. The results revealed that these principals seem to accept the students but disregard their rights and needs. They do not allocate a sufficient budget for the special education departments in their schools to provide the appropriate services. This situation is not necessarily true for all private schools, especially the private schools with high budgets. Therefore, this finding can neither be proven nor generalized to all private schools because no studies have similar findings or interpretations, which was perhaps because of the absence of consistency in the practices of private schools. In contrast, the results emphasized that, as perceived by teachers from public schools, the principals of most public schools in Al Ain assign learning support teams, and create programs to encourage and support SODs’ learning. For public schools in Al Ain, the school district (ADEK) has power over the school principal in terms of the budget, facilities, and recruited teachers. By contrast, the other school systems and rules are managed and directed by the school principal.

It was concluded that most principals in public schools could support SODs and that they could also have better plans for inclusive education. This finding reflected the current state of public schools in Al Ain in terms of the services provided and needs of SODs in those schools. However, the principals of the public schools where the participant teachers worked had different levels of perception and awareness regarding SODs and inclusive schools. Furthermore, no study was found to support this finding. This finding could reflect the status quo of particular public schools. Overall, it is remarkable that school principals have a major role in promoting inclusivity in schools based on the perspectives of the interviewed teachers. School principals’ attitudes toward inclusion and their actions and behavior affect other school members’ attitudes and practices, which then influences the success of those inclusive schools.

Discussion on the Main Factors Affecting SODs

The second question results related to the main factors that affect SODs inside and outside schools, as suggested by general and special education teachers from Al Ain schools. These factors were investigated in this study to focus on the significance of school principals. The participant teachers could agree on some factors that affect SODs and inclusive schools despite the different sectors and conditions of the schools where participants worked. These factors were categorized according to the source, taking into account whether it was from inside or outside the school building. They are described as school-based factors in a study by Anyango (2017). Next, these school-based factors were classified into internal and external factors. This reflects the method adopted in another study by Ng (2015), which categorized the factors influencing inclusive practices concerning SODs into external environmental factors and internal factors.

As the findings suggested, internal school-based factors, those which directly affect SODs within the school building, were classified into environmental, academic, and social, and emotional factors. Those factors included the main conditions and surroundings that directly affect SODs’ learning and which, as a result, influence the effectiveness of inclusive schools. Because many of these internal factors appeared, the researchers had to classify them under these major categories. The following is a detailed discussion and interpretation of each category with links from the literature.

School building safety and healthy surroundings are critical for SODs, and they can determine the success or failure of inclusive schools. As some SODs are unaware of what is dangerous for them, everything should be designed and prepared, to facilitate and ensure their safety in the school building. Konza (2008) clarified that it is essential to highlight the teachers’ needs for a safe and nurturing environment, which are as important and effective as students’ needs in that environment. Managing students with wide-ranging needs is challenging and risky, particularly in the case of failure, when others, including parents, teachers, or students, perceive the school as incompetent and unqualified.

Class size can also affect the performance of SODs. Classes with many students with diverse needs and levels may result in teachers being unable to focus on each student. This situation can lead to teachers being frustrated and losing track of each student’s level and progress. Ng (2015) emphasized that there would be significant benefits for schools that could increase the number of employees, for example, teachers and special needs employees, and decrease class sizes. Notably, a group of shadow teachers explained that big class sizes are not ideal for the application of inclusion because the mainstream teacher has insufficient time and must concentrate and pay attention to students with special needs.

The availability of resources and facilities in a school can also have a direct impact on the success of inclusive schools because the learning of some SODs requires individual devices and resources to reinforce their learning and meet their needs. If the principals neglect this factor, the learning, outcomes, and progress of SODs are affected. Ng (2015) highlighted the need for more resources for students with special needs, which can be used in classrooms. Hussain (2017) also stressed factors that inclusive schools depend on to attain the recommended objectives with non-disabled (typical) and disabled learners, starting with preparing the classroom and school before providing the facilities necessary for teachers’ habilitation, disabled students, and the new process.

Academic factors have a direct impact on a student’s learning and outcomes. These factors include the knowledge and qualifications of the general and special education teachers who teach SODs. As the findings of this study show, inclusive education cannot work if the teachers responsible for students’ learning are not qualified and are unaware of SODs and the best strategies for managing them, which also help those students adapt to the general classroom. As a result, findings emphasized the importance of training and preparing the school staff and specifically teachers who teach SODs, ensuring that the primary purposes of inclusive education are fulfilled and the students’ rights are being honored equally and fairly.

Curriculum and instruction were also classified as one of the academic factors. In some cases, SODs need accommodation and modification of the school curriculum’s content and instructional strategies. When this condition is not provided in schools, the students, as the findings of the present study show, move from one grade level to another without learning and acquiring the same education service as their classmates. As Konza (2008) suggested, inclusion aims to eliminate the separation between general and special education and to ensure that all learners are provided with suitable education in their local school that accommodates their various levels of disability. The educational system should be entirely restructured for the application of inclusion and that requires schools to be responsible for providing all the means necessary for its success, including the facilities, suitable curriculum, and resources needed for all learners irrespective of disability.

Social factors convey the effect of social interactions and relationships between SODs and the people around them in the school environment. Interactions between SODs and others could convey many meanings and impact on a student’s mental and psychological status toward the inclusive classroom environment and their relationships with people. As a result, this may affect the learning and the acquisition of knowledge for SODs. This factor can affect all parties in the social interaction process; it can affect SODs and other students’ learning and socialization, thereby affecting teachers’ achievement and performance in the classroom.

Horn (2011) stressed the importance of social skills in an inclusive environment, for SODs and other students. She referred to the participant teachers’ perspectives and said that they encourage inclusion and value what the students with disabilities can gain by socializing with other typical students. She confirmed that students could learn from each other in many ways: one of the most significant ways is learning new social skills and developing a better understanding of one another. Emotional factors can be directly affected by social factors and can, in turn, affect all other factors, as this study’s findings suggest. Anyango (2017) discusses how the majority of the surveyed teachers in this study referred to the positive impact of inclusion on SODs’ social and emotional development and considered it beneficial to typical students and SODs. This study categorized internal school-based factors were into three areas, including variables, practices, or factors that influence SODs and inclusive schools immensely and most commonly.

According to the external school-based factors, which are related to variables outside the school building and which most teachers agree indirectly but significantly affect SODs’ inclusion in inclusive schools, the parents’ impact, external care centers, and the school districts’ policies and legislations are also significant. As the findings highlighted, parents have a distinct role in facilitating inclusive practices and the transition, admission, placement, and planning procedures of their child of determination regarding the regular school and classroom. Parents can also be an excellent support for schools in promoting their child’s learning and acquisition of new knowledge by following up with them at home and asking the teachers for extra support whenever necessary. Parents’ perception and awareness can also help their children, especially if they are prepared for any expected drawbacks or obstacles that their children experience in the inclusive school environment so that they can prepare their children and support them mentally and spiritually.

Jackson et al. (2000) posited that family involvement is one of the most effective practices in inclusive education. This study outlines that SODs’ families must be involved relatively and meaningfully in their children’s educational development. Families are required to participate in the development and daily routines of their child’s school mission. They highlighted six main functions and roles in which an inclusive school can engage with SODs’ families and that make the family and parents’ role a crucial factor. Examples include creating substantial roles for the parents through opportunities for participation and control; gathering information from families about their children while preparing educational plans; and ensuring effective mutual communication between schools, parents, and others.

The policies and legislation of school districts are other external factors mentioned in other studies. As this study’s findings emphasized, school districts can have control over the ultimate implications and policies implemented in schools and those related to inclusive practices. An excellent example of a school district’s positive impact on inclusive schools is if the district’s new policy states a new strict policy regarding the number of special education teachers in inclusive schools. The policy implies that the number of special education teachers should be linked to the number of SODs in the school and their disabilities. This policy helps SODs’ general education teachers receive the support necessary to teach them inside and outside the classroom. Other beneficial policies can be considered, for example, compulsory professional development for all school principals and samples of teachers from each school.

By contrast, the negative impacts of school districts can be observed through regulation, which, for example, indicates an increasing percentage in the number of admitted SODs in schools or additional moderate to severe cases be permitted access to regular schools. This policy affects the overall school environment and performance, and the teaching and learning practices inside the classrooms, which are crowded with SODs. Therefore, these regulations and policies can have a significant impact on inclusive schools’ practices and success. As Chuchu and Chuchu (2016) reported in their study, the responsibility for education at all school levels lies with government ministries. This includes all curricular and cultural courses and the allocated funds and resources to create inclusive schools and apply more effective rules and policies to acknowledge inclusive education with low achievements. However, this factor, compared with parental impact, is the only factor that the school principal cannot control.

The last external school-based factor is the role of care centers or diagnosing centers dedicated to the SODs’ needs, whether for academic, social, or physical treatment and support. These centers or organizations were not mentioned in the literature as a significant factor. Thus, although most participants in this study suggested and confirmed its impact on SODs’ inclusion in regular schools and on their academic level, it could not be found necessarily an impacting factor on all SODs.

The factors that affect SODs inside and outside the school building are also discussed in the literature, except for one of the external factors. These factors have a crucial impact on SOD’s inclusion in regular schools. The internal factors mentioned in this study have been frequently discussed in other studies and were considered more often than external factors. Likewise, other studies have classified and mentioned these factors as internal and external factors, except for others who have highlighted them as practices or themes.

Discussion on Promoting Inclusive Schools by Principals

The last question results relate to the practices that principals apply to best promote inclusivity in schools. These focused on inclusive practices according to the perspectives of participant teachers, who teach SODs in regular schools, and which they posit as being able to promote and enhance the implementation of inclusion in Al Ain schools. The first finding is that inclusive practices related to staff professional development and the application of inclusive approaches and policies are essential for promoting and enhancing an inclusive school system, as the interviewed teachers suggested.

These practices and their implications are also evidenced in the wider literature. The inclusive practices mentioned in this study include seven actions, including hiring additional special education teachers, holding regular professional development and training courses, encouraging peer coaching and rewarding best practices, limiting the accepted number and types of cases of SODs, allocating a budget for providing SODs’ the facilities and resources they need, reducing class size, and introducing and encouraging co-teaching practices.

Regular professional development sessions and training for school members and parents, as the findings revealed, have a significant impact on SODs’ adaptation in regular schools and their academic performance. Moreover, it has a significant impact on the attitudes of teachers and school members toward SODs and inclusive education. Furthermore, the characteristics of the professional development should be considered by the school principal, for instance, the quality of the training courses, training frequency, and the qualifications and expertise of trainers about inclusive education, ensuring they hold accredited degrees relating to special education. As Ng (2015) found, raising awareness of the need for inclusive classroom practices is crucial, and teacher training and professional development can help increase this awareness and knowledge. He added that professional development could result in a more positive attitude toward teamwork with special education teachers and support staff.

Due to the great importance of this practice, school principals must understand that professional development is necessary for all stakeholders, including themselves. Once the principal is aware of the importance of professional development, he or she will provide it for all school members consistently, to obtain a positive impact. Anati (2012) acknowledged that the primary concern of the teacher participants in this study was the instructional strategies used in inclusive classrooms, because of the shortage of professional development sessions. The desired change can only be accomplished with adequate professional development.

Peer coaching is an advantageous process that can benefit general and special education teachers. Even in general education, it is highly recommended and advised that teachers share experiences and ideas because their degrees of certification could differ, as well as their levels of expertise and development. Konza (2008) discusses the importance of peer coaching and cited studies and models that emphasized this concept. This study outlined that peer coaching could instigate changes throughout schools more effectively. It underlined and focused on the importance of regular weekly coaching or seminar sessions that aim to develop required strategies or skills. From another perspective, rewarding teachers with best practices, as the findings of this study suggest, has a significant impact on other teachers and can be a great motivation for them to perform to a high level and to do their best.

Financial support is a significant foundation for the creation and implementation of new systems and services in schools. Allocating a budget that provides SODs’ needs of facilities and resources, was one of the suggested practices that school principals should apply to ensure that the school building is well equipped with all the requirements for these students. SODs need special devices and tools that help them in the learning process, even for mild cases. Therefore, this practice should be initially considered by school principals to promote their inclusive schools.

As much as financial support is required in schools, the findings revealed that private schools were not empowered financially to provide the required facilities and services for SODs, which consequently called for the importance of new inclusive regulations to change the situation. In agreement with this finding, Anati (2012) emphasized that many private schools in the UAE do not have budgets to employ extra employees or provide additional support facilities and services, observing that there were few special education teachers hired in the private schools where the study participants worked; hence, general education teachers were managing and teaching students with special needs in their classroom independently (Anati, 2012). These findings on private schools in UAE are similar to those of the present study.

Principals must work on limiting the numbers of SODs and the types of disabilities. This practice can contribute to offering learners more rights in learning, equally and fairly. As the findings of the present study show, in crowded classrooms with many SODs teachers cannot pay sufficient attention to each student. A study by Anati (2012) also outlined that participants had concerns about the inclusion of students with severe levels of disability because as they require additional support and effort that are not supported in a classroom setting.

The last two practices refer to the two primary interrelated practices of introducing and encouraging co-teaching in inclusive schools and increasing the number of special education teachers. Co-teaching presents a system of teaching assistance and instruction in a well-organized and well-structured classroom setting, managed and led cooperatively by two or more teachers using different teaching strategies. However, the successful integration of co-teaching requires qualified teachers with high levels of expertise and practice in each classroom.

In a classroom with a large class size with one teacher, class management and differentiation strategies can get out of control because the classroom contains many SODs and non-disabled students, who have diverse levels and needs. This was the situation in most of the classes in the schools investigated in this study, and general education teachers called this situation a hindrance in inclusive classrooms. According to classroom management, Anati (2012) confirmed the existence of this issue and mentioned that her participants, who were against inclusion, suggested that classroom management became more difficult with an increase in students with disabilities in the classroom, which consumed a lot of time during lessons and caused extra consumption of classroom resources, with many behavioral issues observed.

Special education teachers are one of the basic requirements in each inclusive school, to assure that SODs are well diagnosed and that their needs are met in inclusive classrooms and buildings. If the number of special education teachers is insufficient and does not reflect the needs of the included SODs, or when the general education teacher has insufficient knowledge of SODs, students will not receive the special care and individualized support they need. A special education teacher is required to guide the general education teacher and create an individualized plan for SODs to meet their needs, otherwise, SODs will be perceived as a burden for an unknowledgeable teacher. When there is only one special education teacher in a school with numerous cases of SODs, there will be no opportunity for the special education teacher to follow-up with all SODs in that school. Thus, there is a need for additional special education teachers, and the school principal will be the first to be blamed.

According to Anati’s (2012) findings, at the time the study was conducted, teachers were dissatisfied with the inclusion system in UAE schools. She related that negative attitude first to the lack of a group of school systems and requirements such as the proper training for teachers, community awareness regarding the issues expected during the inclusion procedure, and funding for training and resources. Last, and most importantly, is administrators’ insufficient attention to inclusion. These drawbacks and obstacles led to teachers’ and school members’ dissatisfaction, but this could be solved if inclusive practices are applied by school principals. The inclusive practices discussed in this and other studies could enable drastic changes in inclusive school systems and act as remedies for the limitations and hurdles threatening this system as well as SODs’ needs and requirements.

The findings of this study suggest that, regardless of the school sector (i.e., public or private), the principal decides whether to facilitate or constrain practices for a better inclusive school. These decisions can affect the overall school rules and policies related to SODs, which only a principal has authority over. These decisions can also be represented in a principal’s capacity to ensure that special and general education teachers work collaboratively and that general education teachers employ peer coaching and other effective strategies. This can improve the quality of instruction and performance in the inclusive classroom. Other practices can be affected by these rules, for example, training sessions related to professional development and spreading awareness throughout the school regarding inclusion and the rights of SODs. Thus, the process of raising the principal’s awareness of the importance of these actions, practices, and strategies in inclusive schools can increase willingness and ensure an effective implementation process.

Supporting these findings, Geleta (2019) found that principals are proactively required to ensure inclusive school settings. According to this study, principals need individualized training so that they become capable of developing a complete understanding and perception of the meaning of setting up inclusive school systems. School principals’ active involvement and support in inclusive schools is critical. Geleta (2019) emphasizes that school principals have crucial roles in an inclusive school environment’s improvement and the implementation of educational policies. Consequently, the first practice that should be implemented is increasing the school principals’ awareness of their critical role in promoting inclusive school systems and the importance of inclusive practices to SODs and school members. Mthethwa (2008) emphasized that there should be a connection between principals’ knowledge of inclusive education and their attitudes toward it. Once a principal is knowledgeable and well-aware of the importance of inclusive practices for SODs, and of their role in promoting this system, they will be more willing to develop and apply strategies or practices for a better and more inclusive school. The school sector, whether public or private, does not affect this principal’s knowledge or perception and willingness for improvement. In other words, most inclusive practices can be implemented by school principals once they are willing to change their school systems.

The major conclusion of the third question is that the school sector does not affect principals’ willingness or control them once they want to change, and they are aware of the importance of these inclusive practices. As a result, school principals’ awareness is the key factor in promoting inclusive schools. As Avissar et al. (2003) concluded in their study, to ensure that inclusive practices reflect essential changes in a school, the barriers related to people’s attitudes and knowledge should be overcome. This change in attitude can successfully affect the inclusion of students with special needs and ensure inclusive practices are adopted in schools.

Conclusion

The conclusions of this study’s research questions are, first, that the role of school principals in inclusive schools is connected to their attitude and behavior toward SODs and inclusiveness. Second, the main factors that affect SODs in and outside schools that principals should consider, as have teachers suggested, were classified into the following two major groups: internal school-based factors, including environmental, academic, and social, and emotional factors; and external school-based factors, including parents’ impact, external care centers, and school district policies and legislation. Third and last, school principals’ willingness is crucial for implementing successful inclusive practices, as they are responsible for implementing inclusive practices in their schools, protecting the rights of SODs, and providing for their needs regardless of the available budget and facilities. All of the aforementioned can successfully affect the inclusion of students with special needs if initiated by school principals, as perceived by teachers.

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

In summary, according to the review of the literature, this study is the first to examine the determining factors of inclusiveness in schools, with a focus on the role of principals in creating and promoting inclusion in the UAE context. The study provided a comprehensive examination of the critical roles played by school principals from the perspectives of special education teachers and general education teachers. This study’s findings also illuminated the insufficient attention given to SODs because of principals’ inadequate involvement, lack of resources, and absence of awareness among school communities. The findings of the study confirmed the importance of pertinent research in unveiling the complex dynamics of determination, and the role of principals toward creating and promoting inclusive schools. Most of all, this study and its findings highlighted a humane and important issue, i.e., the inclusion of SODs in the normal course of education with their peers who do not possess such limitations is better than being confined in isolated learning environments, resulting in their isolation from society. However, some study findings cannot be generalized to other settings. Therefore, further studies should collect data using other qualitative or quantitative research instruments such as observations, surveys, and other types of interviews to obtain a wider image of the current situation and find a variety of solutions. A larger sample size would also be useful in confirming the validity of the data collected in the present study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by United Arab Emirates University - Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

NK contributed to all elements of the research, conducted the study in schools’ field, and initiated the manuscript draft. ID contributed to the development of the literature review, theoretical foundations, conceptual framework, research design, and editing and reviewing of the manuscript. MA contributed to the overall development and design of the study, reviewed and fine-tuned the results, and coordinated the study. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participant teachers. Without their voluntary participation, this study would not have acquired a complete understanding of the current status and the targeted findings.

References

ADEK (2020). Education of People of Determination. Avaliable at: https://www.adek.gov.ae/Education-of-People-of-Determination/ (accessed March 10, 2020).

Al Neyadi, M. K. A. (2015). Parents Attitude Towards Inclusion of Students With Disabilities into the General Education Classrooms. Al Ain: United Arab Emirates University.

Alborno, N. E. (2013). The Journey Into Inclusive Education: A Case Study of Three Emirati Government Primary Schools. Doctoral dissertation, The British University in Dubai, Dubai.

Alborno, N. E., and Gaad, E. (2014). ‘Index for Inclusion’: a framework for school review in the United Arab Emirates. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 41, 231–248. doi: 10.1111/1467-8578.12073

Alghazo, E. M., and Naggar Gaad, E. E. (2004). General education teachers in the United Arab Emirates and their acceptance of the inclusion of students with disabilities. Br. J. Spec. Educ. 31, 94–99. doi: 10.1111/j.0952-3383.2004.00335.x

Anati, N. M. (2012). Including students with disabilities in UAE schools: a descriptive study. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 27, 75–85.

Anyango, O. M. (2017). School-Based Factors Influencing Implementation of Inclusive Education in Public Secondary Schools in Makadara Sub County, Kenya. Master Theses, University of Nairobi, Kenya.

Avissar, G., Reiter, S., and Leyser, Y. (2003). Principals’ views and practices regarding inclusion: the case of Israeli elementary school principals. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 18, 355–369. doi: 10.1080/0885625032000120233

Badr, H. M. (2019). Exploring UAE teachers’ attitude towards the successful implementation of the general rules in the “School for All” initiative. JLTR 10, 92–102. doi: 10.17507/jltr.1001.11

Barnett, C., and Monda-Amaya, L. E. (1998). Principals’ knowledge of and attitudes toward inclusion. Remedial Spec. Educ. 19, 181–192. doi: 10.1177/074193259801900306

Bell, J. (2015). 100 Percent Inclusion for Disabled People is UAE’s Goal. Avaliable at: https://www.thenational.ae/. (accessed April 15, 2020).

Byrne, M. M. (2001). Understanding life experiences through a phenomenological approach to research. J. Aorn 73, 830–830. doi: 10.1016/s0001-2092(06)61812-7

Chuchu, T., and Chuchu, V. (2016). The impact of inclusive education on learners with disabilities in high schools of Harare, Zimbabwe. J. Soc. Dev. Sci. 7, 88–96. doi: 10.22610/jsds.v7i2.1310

Cohen, E. (2015). Principal leadership styles and teacher and principal attitudes, concerns and competencies regarding inclusion. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 186, 758–764. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.04.105

Creswell, J. (2012). Educational Research: Planning, Conducting, and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research. Boston, MA: Pearson.

Dukmak, S. J. (2013). Regular classroom teachers’ attitudes towards including students with disabilities in the regular classroom in the United Arab Emirates. J. Hral 9:26.

Dyal, A., Flynt, W., and Bennett-Walker, D. (1996). Schools and inclusion: principals’ perception. Clear. House 70, 32–35. doi: 10.1080/00098655.1996.10114355

Fakih, M. (2019). Teachers’ Attitudes Towards Inclusion of Learners With Disabilities at American Private Early Childhood Education in Dubai: An Investigative Study. Doctoral dissertation, The British University in Dubai, Dubai.

Gaad, E., and Almotairi, M. (2013). Inclusion of student with special needs within higher education in UAE: issues and challenges. J. Res. Int. Educ. 9, 287–292. doi: 10.19030/jier.v9i4.8080

Gaad, E., and Khan, L. (2007). Primary mainstream teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion of students with special educational needs in the private sector: a perspective from Dubai. Int. J. Spec. Educ. 22, 95–109.

Gall, M. D., Gall, J. P., and Borg, W. R. (2007). Educational Research: An Introduction. Boston, MA: Pearson.

Geleta, A. D. (2019). School principals and teachers’ perceptions of inclusive education in Sebeta Town Primary Government Schools, Sebeta, Ethiopia. Int. J. Tech. Incl. Educ. 8, 1364–1372. doi: 10.20533/ijtie.2047.0533.2019.0166

Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M., and Namey, E. E. (2014). Applied Thematic Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Hoppey, D., and McLeskey, J. A. (2013). A case study of principal leadership in an effective inclusive school. J. Spec. Educ. 46, 245–256. doi: 10.1177/0022466910390507

Horn, S. V. (2011). The Principal’s Role in Managing special Education: Leadership, Inclusion, and Social Justice Issues. Doctoral dissertation, Washington State University, Washington.

Hussain, A. S. (2017). UAE Preschool Teachers’ Attitudes Toward Inclusion Education by Specialty and Cultural Identity. Doctoral dissertation, Walden University, Washington.

Jackson, L., Ryndak, D., and Billingsley, F. (2000). Useful practices in inclusive education: a preliminary view of what experts in moderate to severe disabilities are saying. J. Assoc. Pers. Sev. Handicaps. 25, 129–141. doi: 10.2511/rpsd.25.3.129

Konza, D. (2008). “Inclusion of students with disabilities in new times: responding to the challenge,” in Learning and the Learner: Exploring Learning for New Times, eds P. Kell, W. Vialle, D. Konza, and G. Vogl (Wollongong: University of Wollongong), 39–64.

Leithwood, K. A., and Jantzi, D. (2008). Linking leadership to student learning: the contributions of leader efficacy. Educ. Adm. Q. 44, 496–528. doi: 10.1177/0013161x08321501

Maxwell, J. A. (2005). Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach. California: Sage Publications.

Morse, J. (1991). On the evaluation of qualitative proposals. Qual. Health Res. 1, 147–151. doi: 10.1177/104973239100100201

Mthethwa, G. S. (2008). Principals’ Knowledge and Attitudes Regarding Inclusive Education: Implications for Curriculum and Assessment. Master’s thesis, University of Zululand, Richards Bay.

Ng, M. S. (2015). Factors Influencing the Success of Inclusive Practices in Singaporean Schools: Shadow Teachers’ Perspectives. Master thesis, University of Oslo, Singapore.

Riehl, C. J. (2000). The principal’s role in creating inclusive schools for diverse students: a review of normative, empirical, and critical literature on the practice of educational administration. Rev. Educ. Res. 70, 55–81. doi: 10.3102/00346543070001055

UNESCO (2019). Inclusion in Education. Avaliable at: https://en.unesco.org/themes/inclusion-in-education/ (accessed March 12, 2020).

Usman, F. (2011). Principals Attitudes Toward Inclusion in Dubai Public Schools: Where do They Stand?. Master’s thesis, Loyola University Chicago, Chicago, IL.

Keywords: school principal, inclusive school, students of determination (SODs), inclusive practices, Al Ain schools

Citation: Khaleel N, Alhosani M and Duyar I (2021) The Role of School Principals in Promoting Inclusive Schools: A Teachers’ Perspective. Front. Educ. 6:603241. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.603241

Received: 05 September 2020; Accepted: 16 March 2021;

Published: 12 April 2021.

Edited by:

Simone Schoch, Zurich University of Teacher Education, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Kuen Fung Sin, The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong KongReto Luder, Zurich University of Teacher Education, Switzerland

Copyright © 2021 Khaleel, Alhosani and Duyar. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.