- 1Department of Educational Psychology, Yangon University of Education (YUOE), Yangon, Myanmar

- 2School of Education, University of New South Wales, Kensington, NSW, Australia

Classroom assessment practices play a pivotal role in ensuring effective learning and teaching. One of the most desired attributes of teachers is the ability to gather and analyze assessment data to make trustworthy decisions leading to supporting student learning. However, this ability is often underdeveloped for a variety of reasons, including reports that teachers are overwhelmed by the complex process of data analysis and decision-making and that often there is insufficient attention to authentic assessment practices which focus on assessment for learning (AfL) in initial teacher education (ITE), so teachers are uncertain how to integrate assessment into teaching and make trustworthy assessment decisions to develop student learning. This paper reports on the results of a study of the process of pre-service teachers’ (PSTs) decision-making in assessment practices in Myanmar with real students and in real classroom conditions through the lens of teacher agency. Using a design-based research methodology, a needs-based professional development program for PSTs’ assessment literacy was developed and delivered in one university. Following the program, thirty PSTs in the intervention group were encouraged to implement selected assessment strategies during their practicum. Semi-structured individual interviews were undertaken with the intervention group before and after their practicum in schools. This data was analyzed together with data collected during their practicum, including lesson plans, observation checklists and audiotapes of lessons. The analysis showed that PSTs’ decision-making in the classroom was largely influenced by their beliefs of and values in using assessment strategies but, importantly, constrained by their supervising teachers. The PSTs who understood the principles of AfL and wanted to implement on-going assessment experienced tension with supervising teachers who wanted to retain high control of the practicum. As a result, most PSTs could not use assessment strategies effectively to inform their decisions about learning and teaching activities. Those PSTs who were allowed greater autonomy during their practicum and understood AfL assessment strategies had greater freedom to experiment, which allowed them multiple opportunities to apply the result of any assessment activity to improve both their own teaching and students’ learning. The paper concludes with a discussion of the kind of support PSTs need to develop their assessment decision-making knowledge and skills during their practicum.

Introduction

Teacher decision-making is essential for effective learning and teaching. A range of research studies highlight the impact of teacher decision-making process on improving student learning (McMillan, 2003; Mccall, 2018; van Phung, 2018). Teachers’ analysis of student data helps to reveal students’ learning needs, which can then be addressed by implementing appropriate learning interventions, highlighting the importance of evidence-informed teacher decision-making skills (McMillan, 2003). To translate these skills into actual student learning gains, there is a need to ensure that teachers are confident and well-equipped to gather and analyze assessment data to make trustworthy decisions leading to supporting student learning.

However, previous research has highlighted that teachers often struggle to justify their use of assessment approaches (Brookhart, 1991; McMillan, 2001; van Phung, 2018). Many report feeling overwhelmed by the complexity of data analysis and decision-making (McMillan, 2003). As teachers’ decision-making is intrinsically a social and cultural experience (Klenowski, 2013), it can be studied through the lens of teacher agency, that is, analyzing how teachers respond to emerging situations in their environment (Priestley et al., 2013, 2015). In teacher decision-making, teacher agency is influenced by the interaction of the context, factors within the school, and the individual teachers’ beliefs and values (Priestley et al., 2015).

In the area of assessment decision-making, most published research concerns the nature of teacher decision-making in marking, grading, and high-stakes testing (McMillan and Nash, 2000; Bowers, 2009; Cheng and Sun, 2015; Kippers et al., 2018). However, as the focus of assessment policy has shifted from summative assessment (assessment of learning) to formative assessment (assessment for learning) (Assessment Reform Group, 2002), more research into teacher decision-making in formative assessment situations is needed. Mccall (2018) suggests that further studies need to be carried out to explore teacher assessment decision-making process, especially in relation to assessment for learning (AfL) and formative assessment practices. However, such teacher decision-making requires far more than a knowledge and understanding of measurement concepts (McMillan, 2003); it requires new forms of teacher assessment literacy (Alonzo, 2016; Davison, 2019). This study uses Alonzo’s (2016) concept of teacher AfL literacy anchored to the principles of AfL, that is “the knowledge and skills to make highly contextualized, fair, consistent and trustworthy assessment decisions to inform learning and teaching to effectively support both students and teachers’ professional learning (p. 58).”

Teachers need to be skilled and knowledgeable in AfL practices before they enter their profession, so that they can decide which assessment strategies are best used to improve student learning. The problem is that much research has shown that pre-service teachers (PSTs) are not always well-prepared in initial teacher education (ITE) to use appropriate assessment strategies to support student learning (Volante and Fazio, 2007; Siegel and Wissehr, 2011; Vogt and Tsagari, 2014; BOSTES, 2016). A theoretical introduction to the basic concepts of assessment in a course is inadequate support to be literate in assessment (Popham, 2011; Greenberg and Walsh, 2012). As a result, PSTs do not have enough confidence in applying assessment knowledge and building their skills (Ogan-Bekiroglu and Suzuk, 2014). Therefore, PSTs need to be given the opportunity to apply understandings in classroom practices, including building effective assessment practices (Grainger and Adie, 2014; McGee and Colby, 2014; DeLuca and Volante, 2016).

This paper reports on a study which investigated the ways in which PSTs made classroom assessment decisions with real students and in real classroom conditions whilst undertaking their final practicum. The study addressed the following research questions:

(1) What factors influence PSTs’ assessment decision-making processes?

(2) How do these factors facilitate or constrain PSTs’ assessment decision-making?

Theoretical Framework

Teacher agency (Priestley et al., 2013, 2015) was chosen as a framework for this study. This perspective on agency is grounded in the sociology and philosophy of action. Teacher agency determines how teachers respond to emerging situations in their environment, resulting from “the interplay of individual efforts, available resources and contextual and structural factors as they come together in particular and, in a sense, always unique situations” (Biesta and Tedder, 2007, p. 137). Teacher agency is the outcome of the interplay of three dimensions: iterational (teachers’ past habitual personal and professional experience); projective (orientation to the future); and practical-evaluative (engagement with cultural, structural, and material context). Teacher agency was used in researching one AfL strategy, rubrics, by Heck (2020) who highlighted the role of agency in improving academics’ assessment literacy and practice. This study uses teacher agency to help explain how PSTs develop their decision-making skills in terms of using assessment strategies to support student learning.

Teacher agency can be achieved by engaging with the available resources, and contextual elements in school (Stritikus, 2003), enabling PSTs to make decisions about what assessment strategies to use by drawing on from the results of interactions of these three dimensions. van der Nest et al. (2018), who studied the impact of formative assessment activities on the development of teacher agency, argue that agency is the outcome of teachers’ engagement with their environment, influenced by their past experience and guided by their future orientation. Individual agency depends on the extent of engagement in the process of learning (Billett, 2004), however, teacher agency is reliant on negotiated assessment procedures (Verberg et al., 2016).

Pre-Service Teachers’ Decision-Making Process and Their Assessment Practices

Building PST capacity for assessment decision-making before entering the profession is crucial in ITE. Piro et al. (2014) argues that the curricula of teacher education programs should support PSTs to build their decision-making based on student assessment data. They describe the effective use of an intervention that teaches PSTs how to work with assessment data in ITE. However, Piro’s study focused only on using summative assessment data such as standardized testing and end-of-course assessment data for accountability purposes. Similarly, Cramer et al. (2014) looked at PSTs’ decision-making based on the use of summative assessment data rather than on data to be used for formative assessment purposes. Therefore, preparing PSTs for effective decision-making should move beyond summative assessment to engage with formative assessment purposes.

A closer look at assessment data intervention studies in ITE shows the need for authentic classroom practices to improve assessment decision-making of PSTs. For example, Reeves and Chiang (2018) explored the effectiveness of data literacy intervention for both in-service and PSTs. Although assessment data practices are embedded in in-service teachers’ intervention, assessment practices for PSTs are still limited. Piro and Hutchinson (2014) and Reeves and Honig (2015) included student assessment data that PST could work with, however, AfL is an ongoing activity where teachers need to draw on a range of different resources in their decision-making about assessment, including interaction with their students.

The work of Black and Wiliam (1998b) and Hattie (2008) highlight that preparing teachers to be literate in assessment, particularly the use of AfL has the highest potential to increase students outcomes. Assessment courses provided in ITE can be classified into three different types: stand-alone assessment courses that are heavily weighted toward theoretical assessment principles, assessment courses including assessment tasks using real students’ work, and assessment courses including real assessment practices. To prepare classroom-ready teachers effectively in assessment, they need this last kind of course, with practical opportunities to improve their learning by reflecting on how to apply key assessment principles to help students (Hill et al., 2013; BOSTES, 2016) in order to make trustworthy assessment decisions that help students improve.

ITE programs need to ensure that PSTs have adequate AfL literacy and have provided student teachers with the opportunity to critique existing assessment knowledge and skills. Also, student teachers need to be provided with a range of opportunities to apply this assessment knowledge to actual classroom settings to see the link between theory and practice (Willis, 2007) and make sense of how assessment literacy influences practice. Without practice in real classrooms with real students, PSTs are likely to “replicate more traditional, unexamined assessment practices” (Graham, 2005, p. 619). Therefore, rather than simply teaching them how to collect assessment information, PSTs need to have a chance to work with real students (Davison, 2015)

Practicum experiences have been found to have a positive effect on PST practices and help to identify professional development needs (Heck et al., 2020), although only a handful of studies have investigated the assessment practices of PSTs in their practicum. For example, Xu and Brown (2016) highlight that PSTs need to have enough practice to be able to apply and evaluate their conceptions of assessment, but in their review of studies on teacher assessment literacy from 1985 to 2015, found less than 20 studies addressing the understanding and development of teacher assessment literacy in practice (see also Campbell, 2013; Hill and Eyers, 2016).

In Myanmar, the Basic Education Curriculum framework is an on-going reform introduced in 2015. However, the types of assessments in this framework are still heavily weighted toward examinations such as end of term, end of year exams, and national level assessment (examinations). Classroom-level assessment/school-based assessment grounded in AfL is included as a small portion of the whole academic year. As a result, students focus on rote learning to get high marks in their exams (Tin, 2000; Aung et al., 2013; Metro, 2015; Maber et al., 2018), and teachers use tests as practice for the final examination. This reliance on mock tests or old questions from national exams shows how the exam-dominated system encourages students to memorize and recite facts. Due to the pressure this puts on the students to have higher outcomes, after-school classes (private tuition) are proliferating. Not all students can access such lessons due to their lack of socio-economic capital, therefore the practice of private tuition has widened the achievement gap among students. However, despite this, the assessment system is on the way to shifting from an exam-dominated system.

In current pre-service teacher education programs in Myanmar, the main assessment content is delivered in subjects on educational testing and measurement, compulsory for all students in teacher training universities. The content is normally related to the construction of the tests, for example, the functions of the tests and item analysis. Even though different forms of assessment—including formative assessment, performance assessment, and portfolio—are covered, the practical understanding and use of these assessments is still undeveloped. According to the findings of Hardman et al. (2016), teachers in Myanmar do not use AfL during teaching. For example, teachers do not use peer tutoring, and teachers do not seem to know how to build pupils’ responses into subsequent questions. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the way in which PSTs can improve their assessment practices.

Materials and Methods

Using a design-based research methodology, a needs-based professional development (PD) program for PSTs’ assessment literacy was developed and delivered. Following the program, thirty PSTs in the intervention group were encouraged to implement the new AfL strategies during their practicum. Semi-structured individual interviews were undertaken with the intervention group before and after their practicum in schools. The interviews were conducted to explore how PSTs applied their knowledge into their practice. For example, ‘What assessment strategies have you tried out in class?’ ‘Why did you use ____ assessment strategy most frequently/least frequently? How did you use? Could you give me an example?’. In addition, lesson plans, observation checklists and audiotapes of their teaching for at least seven teaching periods were gathered from each PST during their practicum, so that they were able to reflect on their assessment practices with the help of these practicum data templates.

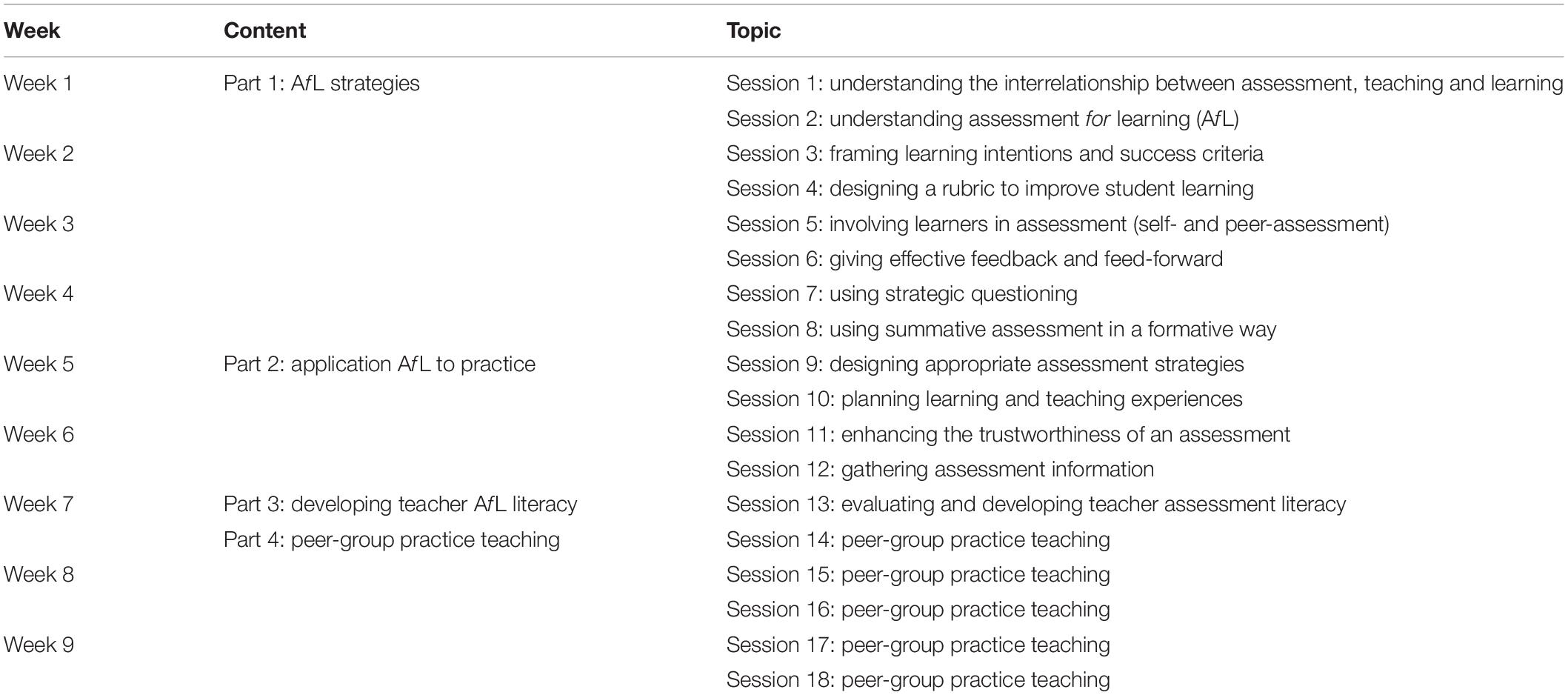

The needs-based PD program was grounded in a view of AfL literacy (Alonzo, 2016) that reflects the principles of AfL. The content of the PD program was adjusted based on the results of needs analysis that identified the current state of PST AfL literacy. The PD program includes four main parts: (i) AfL strategies; (ii) applying AfL to practice; (iii) developing teacher AfL literacy; and (iv) microteaching or peer-group practice teaching. This program was conducted over 2 months (a total of 36 h) with each session taking 2 h as presented in Table 1. Furthermore, the manner in which the program was provided was also an essential component of PST learning. Many courses in ITE are at odds with the underpinning principles of AfL (Timperley, 2014), however the present study followed Davison (2013) and Timperley (2014), ensuring the assessment program was grounded through an AfL approach. Thus, the workshop sessions in the program included initial ‘sharing/reflection’ to explore the background knowledge of the students and to encourage them to recall their previous experiences, and ‘follow-up’ to enable PSTs to reflect on what they had learned. All activities included in this program were based on the local context.

This study was conducted in one of the leading teacher training institutes in Myanmar. Fourth-year student teachers, who had already had experience of practice teaching in their third year, were chosen. A non-probability population sampling method was used due to the voluntary nature of participation. Before the data collection process, ethics approval was gained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Ethics Committee and written permission was gained from the head of the participating university, Myanmar. Among thirty PSTs who expressed their interest to participate in this study, 10 PSTs (33%) were male and 20 PSTs (67%) were female. For their practicum teaching, 30 PSTs went to 17 practicum schools. They had varied total number of teaching period, one teaching period per day to more than three teaching periods per day which depends on the nature of their practicum school.

Results

Following the strategies for qualitative data analysis described by Maxwell (2013), this paper presents the results of the thematic analysis of the semi-structured individual interviews before and after the practicum, with the data collected during the practicum used for triangulation. Five main themes emerged as enabling or constraining factors that influence PST assessment decision-making process: PST assessment knowledge, PST beliefs and values of using assessment, supervising teachers’ influence, student responses and classroom realities. Grounded in a sociocultural approach to teacher agency (Priestley et al., 2015), these main themes were then classified into three dimensions of teacher agency: (1) the iterational dimension; (2) the projective dimension; and (3) the practical-evaluative dimension. In this study, the iterational dimension refers to the PSTs’ assessment knowledge acquired through supplementary professional development in their ITE program. The projective dimension refers to the PSTs’ aspirations for their profession and for their students whilst the practical-evaluative dimension refers to the PSTs interactions with students, supervising teachers and classroom resources while on their final practicum.

Iterational Dimension: PST Assessment Knowledge

PST previous assessment knowledge is one of the key influences on PSTs’ decision-making process. Based on their assessment knowledge gained through their professional learning, the PSTs prepared their AfL strategies and lesson plans. Some PSTs decided to use more assessment strategies to enhance students’ learning. They adjusted their assessment strategies based on their knowledge of student backgrounds and learning needs. For example, PST 11 implemented learning intentions and success criteria, questioning strategies, feedback, self-assessment, and peer-assessment. She used flexible assessment activities and conducted the assessment taking into account the student’s background. She put much effort into her preparation to use AfL strategies in her practicum:

Before I give feedback to them, I have to know all the details. So, I have to prepare very well at night during the practicum. I have spent much time engaged in preparation. This makes me feel more confident in my teaching (PST 11, L 191–193).

Similarly, PST 10 prepared a detailed lesson plan of her assessment strategies, and thought she had been able to implement it effectively, taking into account possible student responses:

From the beginning of preparing lesson plan, I pre think how I’m gonna teach and use assessment, so it is not much difficult. All lessons are taught in expected time range (PST 10, L 175,176).

Unlike PST 10, PST 27 did not prepare the lesson plan systematically to fit the duration of the teaching, for example, she did not set a time for each activity. Her teaching did not match with the lesson plan as she was uncertain when to finish the lessons:

I aimed to teach as I intended in my lesson plan. But when I actually teach, I worry about not finishing all the lessons or having enough time and I didn’t get to teach as I intended (PST 27, L 80–82).

As this was the second practicum for the PSTs, they compared their assessment practices with their first practicum experience. They highlighted how they had improved their use of assessment strategies in this second practicum as well as their assessment decision-making skills. For example, PST 8 commented on her improvement in setting success criteria and learning intention to improve student learning:

Last time I also taught Myanmar subject (her first practicum), which needs much roles of teachers’ explanation. This time I planned how I’m gonna use assessment, setting success criteria and learning intention before I get to teach. It’s really effective for me letting me know the important facts (PST 8, L 207–212).

Similarly, PST 19 commented how she could better implement feedback in this second practicum. In her first practicum, she decided not to use feedback as she did not have enough assessment knowledge and skills. In this second practicum, she was satisfied with her use of feedback, and noted the progress of her use and her students’ improvement in applying feedback in their learning:

In the first practicum, I could not even assess their papers, not even got to the stage giving feedback. I was just lazy, think teaching was the main. But this time, I give feedback to let them know if they actually understand. I realize how to give feedback and note instantly (PST 19, L 222–228).

This section shows how PSTs’ preparation in assessment before the practicum had an impact on PST successful implementation of AfL strategies. In addition, PST assessment knowledge helped them adjust implementation of assessment strategies based on student backgrounds and learning needs.

Projective Dimension: PST Beliefs and Values of Using Assessment

PST beliefs and values in using assessment is one of the key themes influencing PST classroom assessment decision-making. When PSTs had strong beliefs and values in relation to using assessment to improve students’ learning, their positive efforts in using appropriate assessment strategies could be seen in their practicum. In the same way, PSTs did not put much effort into their classroom assessment practices when they did not really believe in the benefits of using assessment strategies to improve learning.

Some PST were well-prepared for their use of assessment strategies as they had strong beliefs and values of using these assessments. For example, PST 8 described the effectiveness of using assessment strategies. She articulated feedback in her practicum based on her students’ needs. At the end, she was satisfied in her use of assessment and her decision-making:

The best part is that when I give them feedback, I understand how to make it interesting even writing in red pen. Most students don’t like red, but I use it with trendy style, so they love it. Even though they see comments in red on their papers, they read them interestingly. I feel quite satisfied to see that they never make those mistakes again and put much effort on it (PST 8, L 75–81).

In addition, she implemented questioning strategies successfully. She could build the students’ answers into subsequent questions, and articulated her students’ progress:

I am well-pleased with the assessment, especially the strategic questioning. Depending on what students respond, I like that I could lead them to get the correct answer themselves (PST 8, L 143–145).

However, some PSTs received negative responses from students as they could not see the positive benefits of their assessments. Their PSTs did not use flexible teaching activities, develop an environment of trust nor build students’ interest in learning. For example, PST 17 did not implement even one AfL strategy because he was not passionate about his practice teaching:

It’s just practicum so I didn’t think I have much responsibility. As the students were not obedient so I didn’t go against them. I had to teach for only 2 weeks, so I didn’t scold them much and I wasn’t too strict (PST 17, L 112–116).

Like PST 17, PST 3 could not implement at least one AfL strategy successfully although she tried. Then she decided not to use these assessment strategies. She did not develop an environment of trust, did not undertake assessment taking into account student background, and did not clarify or correct students’ misconceptions. The evidence can be seen in the following extract:

I told them to ask for help from their peers if they don’t understand something. If not, they can ask to me (Interviewer: So, did they come and ask you?). Yes, they came and asked me. Then, I referred to another student who knows that answer. I couldn’t do the detail explanation because of … (PST 3, L 83–85).

This shows that positive beliefs and values about using assessment generally led to successful assessment practices in practicum, and more negative attitudes led to an avoidance of the use AfL strategies. This result is consistent with that of Izci and Caliskan (2017) who suggested that the experience of successful assessment practices through the positive personal effort of PSTs leads to improving PSTs’ conceptions of assessment. To this end, these results confirm the association between PST personal effort and their successful assessment practices.

Practical-Evaluative Dimension: Supervising Teachers’ Influence

While the practicum is important to improve PST assessment practices in their teaching, not surprisingly supervising teachers were one of the main influences on PST decision-making regarding AfL strategies. In this study supervisors could be divided into controlling or supporting. With controlling supervising teachers, two sub-themes emerged: (i) control over instructional strategies of PST teaching; and (ii) control over the lessons/curriculum that PSTs need to teach. Regarding supporting supervising teachers, two sub-themes emerged: (i) academic/professional support through sharing lesson plans, giving constructive feedback and discussing PSTs’ teaching; and (ii) autonomy, the freedom to develop teaching and assessment practices.

Controlling Effect of Supervising Teachers

This study looked closely at the influence of the personal attributes of supervising teachers on PSTs: their supporting and controlling effects. The study showed that supervising teachers helped or hindered PST implementation of assessment strategies. More controlling supervising teachers were associated with developing tensions and a poor relationship between the supervising teacher and PST. PSTs who had supervising teachers who were very controlling in relation to instructional strategies and the lessons/curriculum, commented that they had to change their assessment decisions and they adjusted their assessment strategies. They could not use assessment strategies according to their lesson plan.

When supervising teachers controlled their instructional strategies, PSTs were not allowed to use assessment-based activities. For example, PST 12 planned to use questioning strategies, feedback, self-assessment and peer-assessment over a range of activities. However, her supervising teachers persisted in controlling her teaching. She commented on how her supervising teacher influenced her teaching:

My supervising teacher told me to teach what I need to teach, like focusing on lessons, not on any extra activities. And she is not observing my teaching from outside of the classroom, she is even sitting in the class with the students (most of her teaching periods) so I don’t get any chance to let students do any activities. Also, the students around her didn’t concentrate on my teaching (PST 12, L 153–155).

Subsequently, PST 12 revealed that she could not use most assessment strategies as she expected and planned. In the middle of her practicum, she decided not to implement assessment strategies because of the tension with her supervising teacher. She was not satisfied with her use of AfL strategies although she recognized the importance and effectiveness of using assessment after the program.

As a result of such control over their teaching, some PSTs were not motivated to use assessment strategies. They could not make choose to use trustworthy assessment strategies to improve students’ learning. For example, PSTs 7 and 28 were hesitant to use assessment strategies as their supervising teachers gave critical feedback in front of their students to control their use of assessment activities. At the end of their practicum, they were unenthusiastic about their teaching and their use of assessment-based activities. The controlling effect of their supervising teachers can be seen in the following extract:

Before even taking the class, I felt uncomfortable worrying that I might get scolded by my supervising teacher. I am not free to teach at all. I am not satisfied with my teaching as I don’t have much preparation time and I don’t get to use much assessments. While assessments are in advance, the class might get noisy, so I am concerned about what the other class teachers think. That’s why I didn’t use assessment frequently (PST 7, L 97–100). While I ask my students to participate in assessment activities, the teachers always shout and scold at us saying “Keep the voice down, it disturbs other classes.” He does that every 2 days. So, I have to think twice before I do activities (PST 28, L 87–94).

In terms of the controlling effect of supervising teachers on lesson content, PSTs mentioned that their supervising teachers were very strict about finishing lessons. They commented that when their supervising teachers asked three or four times to complete lessons in the practicum, it was hard to apply AfL strategies to improve student learning. They commented that they were forced to focus on the completion of lessons rather than the use of AfL strategies because of the controlling effect of their supervising teachers. For example:

Before I started taking a class, I aimed to teach effectively to make sure students understand, by applying proper assessment. But I was instructed to teach up to their [supervising teachers’] expected curriculum, so I had to rush and even took extra classes. My aimed assessment plan was ruined (PST 14, L 33–38).

Having negative experiences with supervising teachers also led to negative consequences for the PSTs’ teaching practice. Some PSTs commented that they received critical comments on their teaching, and they developed bad relationships with their supervising teachers. For example, PST 3 commented that she felt disappointed and unmotivated in her teaching because of criticism from her supervising teacher:

She said she could not teach again what I had taught, and the exam was coming at the end of the month, so students were gonna fail. That’s what she said. And I even ask myself am I the reason why students gonna fail? (PST 3, L 186–189)

These findings reflect those of Smith (2010) who also found that disagreement between student teachers and supervising teachers had a negative effect. PSTs have more challenges when their supervising teachers are controlling their assessment practices (Cavanagh and Prescott, 2007). These results are consistent with the literature, indicating that supervising teachers have an influence not only on PSTs’ teaching (Spooner-Lane et al., 2009; Smith, 2010; Izadinia, 2016; Livy et al., 2016) but also on their authentic assessment practices in the classroom (Graham, 2005; Volante and Fazio, 2007; Absolum et al., 2009; Eyers, 2014; Jiang, 2015).

Supporting Effect of Supervising Teachers

With supportive supervising teachers, two sub-themes emerged in relation to their behaviors: (i) the provision of more autonomy, which gave PSTs the freedom to develop their teaching and assessment practices; and (ii) academic/professional support through sharing lesson plans, giving constructive feedback and discussing PSTs’ teaching. In particular, PSTs who gained greater autonomy during their practicum better understood assessment strategies and continuously applied the results of any assessment activity to identify room for improvement in both their teaching and students’ learning.

If PSTs had supportive supervising teachers who provided autonomy in their teaching, they could then make trustworthy decisions in using assessment to enhance students’ learning. For example, PST 11 commented that her supervising teacher did not tightly control her teaching and gave her freedom regarding the use of assessment strategies. Therefore, she was able to choose appropriate assessment strategies based on students’ responses.

My supervising teacher didn’t control my instructional strategies and the lesson/curriculum that I need to teach. She explained what lessons I need to finish within these 2 weeks at the beginning of my practicum. She gave me the autonomy. She just came to observe my teaching twice for assessment purposes (PST 11, L 53–57).

A comparison of these findings with those of other studies (Weaver and Stanulis, 1996; Moody, 2009) confirm that autonomy can create the opportunity for PSTs to improve their teaching during practicum. Hence, this study seems to reinforce the literature which suggests that PSTs need to have sufficient autonomy to improve their teaching and assessment practices.

Regarding academic support from the supervising teacher, very few PST received academic support such as sharing lesson plans and giving constructive feedback on their teaching practices. PST 9 and 20 were an exception, receiving such support from their supervising teachers.

She supported by providing me with materials. For example, notes of the lesson which is related to the lessons of the curriculum. She showed me how she did it (PST 9, L 48–49). I got the support from them, for example, their notes of the lesson. Then, she advised me how I can do the teaching (PST 20, L 73–74).

In contrast to these PSTs, most PST did not get any professional support from their supervising teachers, such as engaging in a discussion about their teaching, although, PSTs wanted to such support during practicum. For example, PST 7 expected emotional support from his supervising teachers such as friendly and helpful guidance:

When I had my first teaching period, she didn’t tell me how to teach with regard to the curriculum, nor did she discuss with me or even introduce me to the students. That’s when I become inactive (PST 7, L 179–182).

The PSTs expected to receive such support, including engaging in discussion about their teaching. This finding reinforces studies (Cherian, 2007; Caires et al., 2012) which indicated PST need emotional and caring support from their supervising teachers. In addition, this finding confirms the results of previous studies (Richards and Crookes, 1988; Volante and Fazio, 2007; Spooner-Lane et al., 2009) that found insufficient support by supervising teachers in PST practicums. Nguyen (2016) suggested that many supervising teachers will support PSTs only when they have problems during the practicum. However, like other studies (Jiang, 2015), this study found that PSTs only successfully engaged in experimentation with assessment practices if they had the support of their supervising teachers, especially positive and frequent support. Therefore, supervising teachers need to be prepared to support PST AfL assessment practices.

As can be seen from these findings, supervising teachers play an important role in PST practicum. These results are consistent with the literature, indicating that supervising teachers have an influence not only on PST’s teaching (Spooner-Lane et al., 2009; Smith, 2010; Izadinia, 2016; Livy et al., 2016) but also on their authentic assessment practices in the classroom (Graham, 2005; Volante and Fazio, 2007; Absolum et al., 2009; Eyers, 2014; Jiang, 2015). Hence, it is important for supervising teachers to have a positive influence on PST assessment.

However, in Myanmar, where this study took place, there is no proper mentoring program for supervising teachers about how to be a good mentor and how to help PSTs in their practicum. Hence, the findings of this study suggest that supervising teachers should be provided with guidelines on how to support PST, especially in relation to PSTs’ assessment practices and their classroom assessment decision-making during the practicum.

Practical-Evaluative Dimension: Student Responses

This study also found that students’ responses influenced PST classroom assessment decision-making. When PSTs implemented AfL strategies in their practicum, they received various positive, negative or a combination of both responses from their students. PSTs made decisions to adjust their use of assessment strategies or to stop using them, based on students’ responses. It is possible that students’ responses depended on how students saw their PST and to what extent their PSTs were engaged, reflective, and how much effort and passion they put into their teaching.

When PSTs had positive responses from students, they decided to use assessment strategies frequently to improve their students’ learning. Such PSTs mentioned their students’ active participation in assessment activities, ongoing discussion about the lesson after the practicum and positive comments from their students. Some PSTs asked for feedback from their students after the practicum so they could reflect on their teaching. They felt satisfied about their decision to use AfL strategies if they received positive comments from students. For example:

In their comments which are anonymous, they (her students) said they had a clear understanding after engaging in all assessment activities. If not, they could not decide the correct answer (PST 10, L 46–48).

Therefore, students’ engagement and their progress were positive influencing factors which helped PSTs use appropriate assessment strategies. For example, PST 11 commented on her students’ engagement in assessment practices. Although her students were not familiar with the strategies, the progress of her students could be seen through the outcome of using of them:

Even if I forget to give feedback, they remind me to do it (PST 11, L 167–168).

Some come along with questions saying that they think it ought to be another way. And I think this is kind of showing their engagement and you can see their interest (PST 11, L 71–73).

As a result, she decided to use these strategies till the end of the practicum. These results are consistent with those of Absolum et al. (2009) who noted the positive effect of active student-teacher collaboration in assessment practices. However, some PSTs decided not to use these assessments when they had unexpected challenges from their students. For example, some students did not want to give feedback to their peers. In this case, their students gave feedback to PSTs. For example:

After they have done the peer-assessment, they never wanted to give feedback to other students. They always come to me, show me what they’ve done and tell me how they think. That’s not what I expected them to do in their peer-assessment (PST 2, L 64–67).

They don’t wanna give feedback to their peers. What they worry is about that they might assess others wrongly. They never write negative feedback although it is wrong. They worry that they might annoy other students. Maybe because they have never done that before (PST 1, L 49–53).

However, some students had arguments with their peers based on the feedback. Consequently, some PSTs commented that using peer-assessment did not work well according to their lesson plan. They stopped using peer-assessment as they could not control the classroom situation:

I thought they would love to undertake peer-assessment before practicum. When I actually do it, they argue a lot. Therefore, I think before I actually assign peer-assessment to them. I should probably change their attitude first (PST 6, L 115–117).

Therefore, this study showed that students’ responses toward AfL strategies influenced the success or failure of their assessment practices. This result confirms the results of previous studies (Elwood and Klenowski, 2002; Absolum et al., 2009; Jiang, 2015) which found that the influence of students on PST assessment practices was fundamental for effective AfL. Charteris and Dargusch (2018) also observed that students are crucial in shaping and reshaping PST assessment practices during the practicum.

During classroom interactions, the way students responded to their teachers was related to how teachers treated them in terms of using assessment. It follows then that students responded positively to PSTs in terms of the overall AfL strategies, and each AfL strategy when they saw positive efforts from their PSTs. On the other hand, students responded negatively when they saw the negative efforts of their PSTs. The performance of PSTs is one of the causes of positive and negative student responses. However, it should be noted that this study focuses on the results from the perspectives of PSTs.

Practical-Evaluative Dimension: Classroom Realities

During PST assessment practices, classroom realities emerged as one of the influencing factors on PST assessment decision-making. The classroom setting of the school, the number of teaching periods, and the time of day of the particular period influenced assessment decision-making during the practicum.

The classroom setting of the school was one of the influential factors in PSTs’ assessment practices. Unless they had enough space, PSTs could not implement the assessment-based activities effectively. Many PSTs needed to group students or rearrange students in a lecture-oriented classroom when they implemented assessment-based activities. For this reason, some PSTs commented that they were negatively influenced by the classroom setting. They stopped using self- and peer-assessments because of the negative influence of space in the classroom. For example:

The classroom isn’t wide enough. It can’t rearrange desks and chairs for activities. It’s just wasting time (PST 28, L 29–30).

The classroom is not large enough for a teacher to walk through (PST 14, L 20).

In contrast, some PSTs reported that they had enough space to implement assessment-based activities. For example, PST 11 commented that her classroom was wide enough to implement most AfL strategies:

The classroom has enough space for 36 students to perform assessment-based activities, so it doesn’t matter to be noisy (PST 11, L 47–49).

The data suggests that PSTs need enough space in their classroom to do key assessment activities. Therefore, the physical setting of the school help PSTs choose appropriate assessment strategies based on students’ needs.

A second classroom reality was the number of teaching periods, which the PSTs could not control. This study found a variety of PSTs’ experience regarding the number of teaching periods. Some PSTs had more than three teaching periods per day while some had less than one teaching period per day. When PSTs had fewer teaching periods in their practicum, they did not get the chance to implement more assessment strategies or assessment practices. For example, PST 4 mentioned that:

I got just five teaching periods for the whole practice teaching. This is not enough to get an experience of assessment practices (PST 4, L 222,223).

This study shows that PST can experiment with more AfL strategies when they have more teaching periods where they have a chance to practice their assessment knowledge and skills. These results are consistent with those of Mitton-Kukner and Orr (2014) who found that the length of the teaching period is one of the influences on the PST practicum.

In terms of time of day, four PSTs commented that they have positive and negative influences in their assessment practices, for example, earlier and later time of day. They commented that the time of day had an effect on students’ involvement in assessment practices. For example:

Most of the students could not concentrate on lessons at the last period of a day. During last class, they just wanna finish the class. Only the students sitting on the front seats pay attention on teaching (PST 1, L 119–121).

As my class time is second period so that’s ok. Once one physics teacher requested me to switch my class with hers because she wanted her students to learn in fresh minds. And I ended up taking afternoon class which is period after lunch break. I could not teach properly on that days. I had to wait may be 15 min because there was complete chaos when I entered the classroom (PST 8, L 30–35).

These PSTs commented that if they had the earlier time of day, they could decide to implement more AfL strategies and their students could engage more in assessment practices. If PSTs had teaching periods later in the day, students did not actively engage in assessment activities. Therefore, an earlier time of day had a positive influence on students’ responses in PSTs’ assessment practices while a later time of day had a negative influence on students’ responses. This suggests that time of the day is one of the classroom realities that PST could not control. Therefore, PST should be equipped with many opportunities to experiment with assessment practices in the practicum. In addition, there is no literature on the association between these factors of classroom realities and PST assessment practices. Therefore, further studies need to be undertaken which can take these influences into account.

Discussion and Conclusion

Drawing on the nature of teacher agency, this study has enabled us to understand the factors which can influence PSTs’ assessment decision-making process and the extent to which PSTs can exercise agency by engaging with the influencing factors of school context, available resources, and their beliefs and experiences. The factors which influenced classroom assessment decision-making found in this study were (i) the iterational dimension: PST assessment knowledge (ii) the projective dimension: PST beliefs and values of using assessment, and (iii) the practical evaluative dimension: their supervising teachers, students’ responses, and classroom realities. These influences on teacher assessment decision-making are somewhat aligned with previous studies (McMillan and Nash, 2000; McMillan, 2003) which also demonstrated the influence of external factors, including state accountability testing, district policies, and parents. However, as the role of PSTs in the practicum does not include working with parents and school leaders within such a short period of practice teaching in Myanmar, the influence of parents and district policies was not explored.

In decision-making processes, there is also tension between PSTs’ beliefs and values and external influences: stakeholder, student responses, and classroom realities which is consistent with the results of Black and Wiliam (1998a) and McMillan (2003). PSTs who have a good sense of how AfL operates, in using on-going assessment and using the results to make decisions including adjustment of learning and teaching activities, developed tension with supervising teachers who exerted strong control over their practicum. In addition, when PSTs are negatively influenced by one or more of these factors, they could not make appropriate assessment decisions to improve students’ learning. Those PSTs who gained greater autonomy during their practicum better understood assessment strategies and continuously applied the results of any assessment activity to identify room for improvement both in their teaching and students’ learning. Therefore, this study contributes to recent literature on teacher agency (Priestley et al., 2013, 2015; Buchanan, 2015; Loutzenhesier and Heer, 2017) which has argued that teacher agency during PST assessment practices is heavily impacted by particular contextual factors. Teacher agency has emerged through their engagement with the environment which is consistent with previous studies (Biesta and Tedder, 2007; Priestley et al., 2013; van der Nest et al., 2018). Teachers exercised their attributes in engaging with that specific context, for example, modifying the assessment strategies. PSTs responded differently to these influences in accordance with the findings of Verberg et al. (2016).

In general, teacher training institutes or colleges need to understand the essential role of authentic assessment practices in classrooms for PSTs. Participating in assessment practices develops a sense of agency that they can engage with real students in classroom. The findings of this study show that PSTs improved their classroom assessment decision-making through working with students. Therefore, teacher training institutes or colleges need to ensure that student teachers have an opportunity to practice and reflect on their assessment during practicum. To improve PST classroom assessment decision-making in their assessment practices, cooperation between teacher training institutes and school practicum schools must be improved. It is important that PSTs, teacher educators and the other key stakeholders from the practicum school can speak the same language, especially in PST teaching where influences on PST assessment practices are interactive. However, in Myanmar, there is less contact between teacher educators and the practicum school in terms of improving PST assessment practices and teaching than in assessing PST teaching generally. This suggests that teacher educators, supervising teachers and PSTs should cooperate more at the beginning of the practicum. This study provides a better understanding of how to improve PST assessment decision-making in their assessment practices through addressing the interactive nature of assessment influences.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the HREA Panel B: Arts, Humanities & Law of UNSW Australia and Yangon University of Education, Myanmar. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author Contributions

CO: conceptualization, Professional Development (PD) program design and implementation, PD program delivery, methodology, data collection, transcription, data analysis and interpretation, writing-reviewing, and editing. DA and CD: conceptualization, PD program design and implementation, methodology, data analysis and interpretation, writing-reviewing, and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This study was supported by a Presidential Scholarship, Myanmar.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Absolum, M., Flockton, L., Hattie, J., Hipkins, R., and Reid, I. (2009). Directions for Assessment in New Zealand: Developing Students’ Assessment Capabilities. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

Alonzo, D. (2016). Development and Application of a Teacher Assessment for Learning (AfL) Literacy Tool. Doctoral dissertation, The University of New South Wales, Kensington, NSW.

Assessment Reform Group (2002). Assessment for Learning: 10 Principles. Available online at: www.assessment-reform-group.org.uk (accessed August 2, 2016).

Aung, W., Hardman, F., and Myint, A. A. (2013). Development of a Teacher Education Strategy Framework Linked to Pre- and in-Service Teacher Training in Myanmar. San Diego, CA: The Institute For Effective Education.

Biesta, G., and Tedder, M. (2007). Agency and learning in the lifecourse: towards an ecological perspective. Stud. Educ. Adults 39, 132–149. doi: 10.1080/02660830.2007.11661545

Billett, S. (2004). Workplace participatory practices. J. Workplace Learn. 16, 312–324. doi: 10.1108/13665620410550295

Black, P., and Wiliam, D. (1998a). Assessment and classroom learning. Assess. Educ. 5, 7–74. doi: 10.4324/9781315123127-3

Black, P., and Wiliam, D. (1998b). Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. Phi Delta Kappan 80, 139–148. doi: 10.1002/hrm

BOSTES (2016). Learning Assessment: A Report on Teaching Assessment in Initial Teacher Education in NSW. Sydney, NSW: NSW Government.

Bowers, A. J. (2009). Reconsidering grades as data for decision making: more than just academic knowledge. J. Educ. Administr. 47, 609–629. doi: 10.1108/09578230910981080

Brookhart, S. M. (1991). Grading practices and validity. Educ. Meas. Issues Pract. 10, 35–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-3992.1991.tb00182.x

Buchanan, R. (2015). Teacher identity and agency in an era of accountability. Teach. Teach. 21, 700–719. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2015.1044329

Caires, S., Almeida, L., and Vieira, D. (2012). Becoming a teacher: Student teachers’ experiences and perceptions about teaching practice. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 35, 163–178. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2011.643395

Campbell, C. (2013). “Research on teacher competence in classroom assessment,” in SAGE Handbook of Research on Classroom Assessment, ed. J. H. McMillan (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE).

Cavanagh, M., and Prescott, A. (2007). “Professional experience in learning to teach secondary mathematics: incorporating pre-service teachers into a community of practice,” in Proceedings of the 30th Annual Conference of the Mathematics Education Research Group of Australasia, Vol. 1, eds J. Watson and K. Beswick (Adelaide: MERGA), 182–191.

Charteris, J., and Dargusch, J. (2018). The tensions of preparing pre-service teachers to be assessment capable and profession-ready. Asia Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 46, 354–368. doi: 10.1080/1359866X.2018.1469114

Cheng, L., and Sun, Y. (2015). Teachers grading decision making: multiple influencing factors and methods. Lang. Assess. Q. 12, 213–233. doi: 10.1080/15434303.2015.1010726

Cherian, F. (2007). Learning to teach: teacher caniddates reflect on the relational, conceptual, and contextual influences of responsive mentorship. Can. J. Educ. 30, 25–46. doi: 10.2307/20466624

Cramer, E. D., Little, M. E., and McHatton, P. A. (2014). Demystifying the data-based decision-making process. Action Teach. Educ. 36, 389–400. doi: 10.1080/01626620.2014.977690

Davison, C. (2013). “Innovation in assessment: common misconceptions and problems,” in Innovation and Change in English Language Education, eds K. Hyland and L. L. Wong (Oxon: Routledge), 263–275.

Davison, C. (2015). “Enhancing teacher assessment literacy: practising what we preach,” in Paper Presented at 2015 Assessment in Schools Conference, (Sydney, NSW).

Davison, C. (2019). “Using assessment to enhance learning in English language education,” in Second Handbook of English Language Teaching, Springer International Handbooks of Education, ed. X. Gao (Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland), 433–454. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-02899-2_21

DeLuca, C., and Volante, L. (2016). Assessment for learning in teacher education programs: navigating the juxtaposition of theory and praxis. J. Int. Soc. Teach. Educ. 20, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2013.02.001

Elwood, J., and Klenowski, V. (2002). Creating communities of shared practice: the challenges of assessment use in learning and teaching. Assess. Evaluat. High. Educ. 27, 243–256. doi: 10.1080/02602930220138606

Eyers, G. (2014). Preservice Teachers’ Assessment Learning: Change, Development and Growth. Doctoral dissertation, The University of Auckland, Auckland.

Graham, P. (2005). Classroom-based assessment: changing knowledge and practice through preservice teacher education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 21, 607–621. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2005.05.001

Grainger, P., and Adie, L. (2014). How do preservice teacher education students move from novice to expert assessors? Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 39, 1–18. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2014v39n7.9

Greenberg, J., and Walsh, K. (2012). What Teacher Preparation Programs Teach About K – 12 Assessment: A Review. Washington, DC: National Council on Teacher Quality.

Hardman, F., Stoff, C., Aung, W., and Elliott, L. (2016). Developing pedagogical practices in Myanmar primary schools: possibilities and constraints. Asia Pac. J. Educ. 36, 98–118. doi: 10.1080/02188791.2014.906387

Hattie, J. (2008). Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-analysis Relating to Achievement. Milton Park: Routledge.

Heck, D. (2020). “Talking about rubrics in higher education: exploring academic agency,” in Facilitating Student Learning and Engagement in Higher Education through Assessment Rubrics, eds P. Grainger and K. Weir (Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing).

Heck, D., Willis, A., Simon, S., Grainger, P., and Smith, K. (2020). “Becoming a teacher: scaffolding post-practicum reflection,” in Enriching Higher Education Students’ Learning through Post-work Placement Interventions, Professional and Practice-based Learning, eds S. Billett, J. Orrell, D. Jackson, and F. Valencise-Forrester (Cham: Springer), 173–188. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-48062-2

Hill, M. F., and Eyers, G. (2016). “Moving from student to teacher,” in Handbook of Human and Social Conditions in Assessment, eds G. T. L. Brown and L. R. Harris (Milton Park: Routledge).

Hill, M. F., Smith, L. F., Cowie, B., Gilmore, A., and Gunn, A. (2013). Preparing Initial Primary and Early Childhood Teacher Education Students to Use Assessment: Final Summary Report. Wellington: Teaching and Learning Research Initiative.

Izadinia, M. (2016). Student teachers’ and mentor teachers’ perceptions and expectations of a mentoring relationship: do they match or clash? Prof. Dev. Educ. 42, 387–402. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2014.994136

Izci, K., and Caliskan, G. (2017). Development of prospective teachers’ conceptions of assessment and choices of assessment tasks. Int. J. Res. Educ. Sci. 3, 464–474. doi: 10.21890/ijres.327906

Jiang, H. (2015). Learning to Teach with Assessment: A Student Teaching Experience in China. Cham: Springer.

Kippers, W. B., Wolterinck, C. H. D., Schildkamp, K., Poortman, C. L., and Visscher, A. J. (2018). Teachers’ views on the use of assessment for learning and data-based decision making in classroom practice. Teach. Teach. Educ. 75, 199–213. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2018.06.015

Klenowski, V. (2013). Towards improving public understanding of judgement practice in standards-referenced assessment: an Australian perspective. Oxford Rev. Educ. 39, 36–51. doi: 10.1080/03054985.2013.764759

Livy, S. L., Vale, C., and Herbert, S. (2016). Developing primary pre-service teachers’ mathematical content knowledge during practicum teaching. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 41, 1–23. doi: 10.1007/s13394-018-0252-8

Loutzenhesier, L., and Heer, K. (2017). “Unsettling habitual ways of teacher education through ‘post-theories’ of teacher agency,” in The SAGE Handbook of Research in Teacher Education, eds D. Clandinin and J. Husu (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publication), 317–331. doi: 10.4135/9781526402042.n18

Maber, E. J. T., Oo, H. W. M., and Higgins, S. (2018). “Understanding the changing roles of teachers in transitional Myanmar,” in Sustainable Peacebuilding and Social Justice in Times of Transition, eds M. Lopes Cardozo and E. Maber (Springer), 117–139. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-93812-7_6

Maxwell, J. A. (2013). Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach, 3rd Edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Mccall, V. A. (2018). The Decision-Making Process Used to Determine Formative Assessment Strategies and Subsequent Instructional Design. Aurora, IL: Aurora University.

McGee, J., and Colby, S. (2014). Impact of an assessment course on teacher candidates’ assessment literacy. Action Teach. Educ. 36, 522–532. doi: 10.1080/01626620.2014.977753

McMillan, J. H. (2001). Secondary teachers’ classroom assessment and grading practices. Educ. Meas. Issues Pract. 20, 20–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-3992.2001.tb00055.x

McMillan, J. H. (2003). Understanding and improving teachers’ classroom assessment decision making: implications for theory and practice. Educ. Meas. Issues Pract. 22, 34–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-3992.2003.tb00142.x

McMillan, J. H., and Nash, S. (2000). “Teacher classroom assessment and grading practices decision making,” in Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the National Council on Measurement in Education, (New Orleans, LA), 39.

Metro, R. (2015). “Students and teachers as a agents of democratization and national reconciliation in Burma,” in Contemporary Burma/Myanmar, eds R. Egreteau and F. Robinne (Singapore: NUS Press), 209–223. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv1ntgbt.15

Mitton-Kukner, J., and Orr, A. M. (2014). Making the invisible of learning visible: pre-service teachers identify connections between the use of literacy strategies and their content area assessment practices. Alberta J. Educ. Res. 60, 403–419.

Moody, J. (2009). Key elements in a positive practicum: insights from Australian post-primary pre-service teachers. Irish Educ. Stud. 28, 155–175. doi: 10.1080/03323310902884219

Nguyen, L. T. H. (2016). Development of Vietnamese Pre-service EFL Teachers’ Assessment Literacy. Doctoral thesis, Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington.

Ogan-Bekiroglu, F., and Suzuk, E. (2014). Pre-service teachers’ assessment literacy and its implementation into practice. Curriculum J. 25, 344–371. doi: 10.1080/09585176.2014.899916

Piro, J. S., Dunlap, K., and Shutt, T. (2014). A collaborative data chat: teaching summative assessment data use in pre-service teacher education. Cogent Educ. 1, 1–24. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2014.968409

Piro, J. S., and Hutchinson, C. J. (2014). Using a data chat to teach instructional interventions: student perceptions of data literacy in an assessment course. New Educ. 10, 95–111. doi: 10.1080/1547688X.2014.898479

Popham, W. J. (2011). Assessment literacy overlooked: a teacher educator’s confession. Teach. Educ. 46, 265–273. doi: 10.1080/00405840802577536

Priestley, M., Biesta, G., and Robinson, S. (2013). “Teachers as agents of change: teacher agency and emerging models of curriculum,” in Reinventing the Curriculum: New Trends in Curriculum Policy and Practice, eds M. Priestley and G. Biesta (London: A&C Black).

Priestley, M., Biesta, G., and Robinson, S. (2015). Teacher Agency: An Ecological Approach. London: Bloomsbury.

Reeves, T. D., and Chiang, J. L. (2018). Online interventions to promote teacher data-driven decision making: Optimizing design to maximize impact. Stud. Educ. Evaluat. 59, 256–269. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2018.09.006

Reeves, T. D., and Honig, S. L. (2015). A classroom data literacy intervention for pre-service teachers. Teach. Teach. Educ. 50, 90–101. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2015.05.007

Richards, J. C., and Crookes, G. (1988). The practicum in TESOL. TESOL Q. 9, 9–27. doi: 10.2307/3587059

Siegel, M. A., and Wissehr, C. (2011). Preparing for the plunge: preservice teachers’ assessment literacy. J. Sci. Teach. Educ. 22, 371–391. doi: 10.1007/s10972-011-9231-6

Smith, K. (2010). Assessing the Practicum in teacher education – do we want candidates and mentors to agree? Stud. Educ. Evaluat. 36, 36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.stueduc.2010.08.001

Spooner-Lane, R., Tangen, D., and Campbell, M. (2009). The complexities of supporting Asian international pre-service teachers as they undertake practicum. Asia Pac. J. Teach. Educ. 37, 79–94. doi: 10.1080/13598660802530776

Stritikus, T. T. (2003). The interrelationship of beliefs, context, and learning: the case of a teacher reacting to language policy. J. Lang. Ident. Educ. 2, 29–52. doi: 10.1207/S15327701JLIE0201_2

Timperley, H. (2014). “Using assessment information for professional learning,” in Designing Assessment for Quality Learning, eds C. Wyatt-Smith, V. Klenowski, and P. Colbert (Dordrecht: Springer), 137–149. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-5902-2_9

Tin, H. (2000). Myanmar education: status, issues and challenges. J. Southeast Asian Educ. 1, 134–162.

van der Nest, A., Long, C., and Engelbrecht, J. (2018). The impact of formative assessment activities on the development of teacher agency in mathematics teachers. S. Afr. J. Educ. 38, 1–10. doi: 10.15700/saje.v38n1a1382

van Phung, D. (2018). Variability in Teacher oral English Language Assessment. Sydney, NSW: The University of New South Wales.

Verberg, C. P. M., Tigelaar, D. E. H., van Veen, K., and Verloop, N. (2016). Teacher agency within the context of formative teacher assessment: an in-depth analysis. Educ. Stud. 42, 534–552. doi: 10.1080/03055698.2016.1231060

Vogt, K., and Tsagari, D. (2014). Assessment literacy of foreign language teachers: findings of a European study. Lang. Assess. Q. 11, 374–402. doi: 10.1080/15434303.2014.960046

Volante, L., and Fazio, X. (2007). Exploring teacher candidates’ assessment literacy: Implications for teacher education reform and professional development. Can. J. Educ. 30, 749–770. doi: 10.2307/20466661

Weaver, D., and Stanulis, R. N. (1996). Negotiating preparation and practice: student teaching in the middle. J. Teach. Educ. 47, 27–36. doi: 10.1177/0022487196047001006

Willis, J. (2007). Assessment for learning – why the theory needs the practice. Int. J. Pedagogies Learn. 3, 52–59. doi: 10.5172/ijpl.3.2.52

Keywords: teacher decision-making, assessment practices, assessment for learning, pre-service teacher, teacher agency, initial teacher education, practicum

Citation: Oo CZ, Alonzo D and Davison C (2021) Pre-service Teachers’ Decision-Making and Classroom Assessment Practices. Front. Educ. 6:628100. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.628100

Received: 11 November 2020; Accepted: 15 March 2021;

Published: 01 April 2021.

Edited by:

Susan M. Brookhart, Duquesne University, United StatesReviewed by:

Peter Ralph Grainger, University of the Sunshine Coast, AustraliaEric C. K. Cheng, The Education University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

Copyright © 2021 Oo, Alonzo and Davison. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Cherry Zin Oo, Y2hlcnJ5emlub29AeXVvZS5lZHUubW0=

Cherry Zin Oo

Cherry Zin Oo Dennis Alonzo

Dennis Alonzo Chris Davison

Chris Davison