- 1Department of Education, Forman Christian College, Lahore, Pakistan

- 2Department of Teacher Education, University of Okara, Okara, Pakistan

- 3Department of Educational Research and Assessment, University of Okara, Okara, Pakistan

Private school culture dominates the public-school culture in Pakistan. With no central regulating organization, private schools in the country autonomously construct their educational philosophy that underpins curriculum choice, pedagogic approaches, and school operations. In this perspective, there is an increasing inquisitiveness in the understanding of what determines a private school as a “successful” school. The researchers intend to understand the determinants of a successful private school and aim to explore the leadership behaviors of head teachers of such schools in Pakistan. The Beaconhouse School System (BSS), the largest private school system in Pakistan, took part in this case study. A sample of a total of 128 participants, comprising of teachers (n = 120), School Group Heads (SGH) (n = 4) and school head teachers (n = 4) of four most successful primary schools of BSS, was drawn to participate in this case study employing a mixed-methods design. Two survey instruments, Determinants of School Success (DSS) and Leadership Practice Index (LPI) were developed on a five-point Likert Scale and applied to identify four most successful primary schools of BSS. It was found that head teachers had established a whole-school approach towards students high achievement, promoted a culture of trust, commitment, shared vision, practiced distributed leadership and involved all stakeholders in creating a shared sense of direction for the school. Recommendations have been generated for improving the performance of school leaders.

Introduction

About one-third of school-going children in Pakistan attend private schooling (Andrabi et al., 2013; Nguyen and Raju, 2014). The industry of Pakistan’s private schools largely comprises of institutions that are for-profit, autonomous, and unregulated by any central institution. Around two percent of average household income, in both rural and urban areas constitute the industry of private schooling consequently resulting in producing magnanimous annual gross income recorded in the academic year 2013—2014 up to four ninety-seven million (Pakistan Education Statistics, 2014). The annual survey report of All Pakistan Private Schools Association (APPSA) presents a tentative number of private schools operating in Pakistan; there is no accurate number of institutions that can be categorized as a “Private School”. As of 2014, one hundred seventy-three thousand one hundred and ten private schools were operating nationwide, 56% of which were concentrated in one province, Punjab.

The history of private schooling in Pakistan goes back to the era of British Rule in the sub-continent. The first private school, Karachi Grammar School was established in 1847 in Karachi. In the 1990s, on account of the decentralization of primary education, there was a dramatic boom in the emergence of private primary schools across the country. The research proposes unsatisfactory service delivery in government schools as one of the factors for this boom (Andrabi et al., 2008; Baig, 2011). Another often-stated reason is low operating costs and high revenue mainly due to low labor wages; private school teachers are paid less than government schoolteachers (Baig, 2011; Andrabi et al., 2013). Lack of a standard pre-requisite level of education and professional training makes it easier to find teachers who are willing to work on low wages set by private schools. A third contributing factor is a mutual consensus by the local community to associate a necessary students higher achievement with private schooling. However, this assumption is not backed by authentic academic research.

Nonexistence of a central regulatory authority to ensure the standardized quality of service at private schools in Pakistan, service delivery decisions are directed by prevailing market trends and influenced by policymakers of individual schools (Salfi, 2011). Private schools enjoy full autonomy to select school curriculum, pedagogical methods, staff training models and inclusion of society. Some wide-spread networks of school branches belonging to a school system practice standardized procedure across all branches. Research asserts that even at these large school networks the pre-requisites for selecting a head teacher are not standard and may be greatly compromised in some underdeveloped cities of Pakistan.

It has been repeatedly reported by researchers around the world that head teacher plays a vital role in determining the success of a school in terms of management, high teacher performance, positive students’ learning outcomes and social reputation in the community (Böhlmark et al., 2016; Education Review Office, 2018; Felix-Otuorimuo, 2019; Leithwood et al., 2019. Fullan (2001) has gone as far to conclude that, “Effective school leaders are key to large-scale, sustainable education reform” (p. 15). These arguments suggest the need to determine what factors and determinants contribute to a successful school leadership particularly in the context of a private school system in a country where the absence of central regulatory authority creates a situation of non-standardized quality of services that leads to a state of disorganized school management.

The Focus of the Research

International studies confirm a positive relationship between the role of head teacher and school success (Haydon, 2007; Leithwood et al., 2006; Winton, 2013). In the case of Pakistan, the meaning of school success is relative and varies hugely from one school to another. Lack of standard prerequisites for the hiring of head teachers in the private education sector creates a troubling void in understanding the relationship between leadership qualities of head teachers and school success (Iqbal, 2005). To avoid heterogeneity this research maintains its focus only on the largest private primary schools’ network the Beaconhouse School System (BSS).

The objective of this study is two-fold; to identify determinants of school success conceived by the largest private school network of Pakistan and to understand common leadership qualities of successful school head teachers. The synthesis of results determines the relationship between school heads and school success. The core research questions addressed in this study are:

1) What are the determinants of a successful school in the private sector of Pakistani schools?

2) What are school head teachers’ leadership qualities in successful private primary schools of BSS in the province of Punjab?

3) What are the common trends in the leadership qualities of these school head teachers?

Significance of the Research

Beaconhouse School System (BSS) is the largest and most wide-spread network of private schools in Pakistan contributing up to 38% to the total number of private primary school enrolment in the province of Punjab (PES, 2014). It is the first school network in the country to set in-place a School Evaluation Unit (SEU) that carries out cyclical school evaluations to report periodic individual school performance in terms of “good” practices and areas for further development. However, these are internal documents and not to be used as a resource for sharing of good practices and remain a missed opportunity to draw descriptors of a successful BSS school in the context of Pakistan and to further identify the qualities of a good school leader. This research is an attempt to fill this gap by synthesizing this information to help Pakistan’s largest private schools network to learn from their success and to use findings to design targeted head teachers training programs.

This study concentrates in the primary school section due to the high impact the selected section has on the overall education standard in the region. BSS takes approximately 38% of primary school enrollment in Punjab through a range of their education products including The Educators, United Chartered Schools, and mainstream Beaconhouse Schools. The study has significant implications for the other networks of private schools in Pakistan for bringing reforms in school leadership programs. It can augment for establishing effective school leadership practices for the success of other schools in BSS and the schools of other networks in general. The study signifies to reduce a gap of quality school leadership between one of the most popular school networks in the country and public sector schools of the province of Punjab.

Methodology

This study employed a mixed methods research design using four schools working under the umbrella of the Beaconhouse School System. An in-depth case study was undertaken by using multiple sources of data collection, analysis, and interpretation (Johnson and Onwuegbuzie, 2004). In the quantitative standard, the researchers collected data from the selected teachers working in the four schools of BSS through two questionnaires; Determinants of School Success (DSS) and Leadership Practice Index (LPI) formulated on a five-point Likert scale. This was followed by in-depth semi-structured interviews with different stakeholders including the school head teachers and SGHs. This research process was accomplished within 3 weeks. The researchers employed a mixed-methods research approach to make the research findings more reliable, valid, and to minimize the level of bias by comparing sets of data by data triangulation and grasping an in-depth understanding of the case of BSS (Gurr et al., 2005; Osseo-Asare et al., 2005).

Population

Beaconhouse School System (BSS), the largest private school network operating in Pakistan with more than three hundred and seventy-five branches spread across the country, serves as the primary population and a case of study for this research. The school system was established in the province of Punjab in 1975 and it is now the largest school system of its type in the country catering to over two hundred forty-seven thousand students across Pakistan. Most of the students come from upper-middle-class families with a gross monthly household income between fifty thousand rupees up to three hundred thousand rupees (Andrabi et al., 2013). BSS caters to modern educational needs and follows a customized curriculum influenced by the British and Scottish national curricula.

Organizational Setup

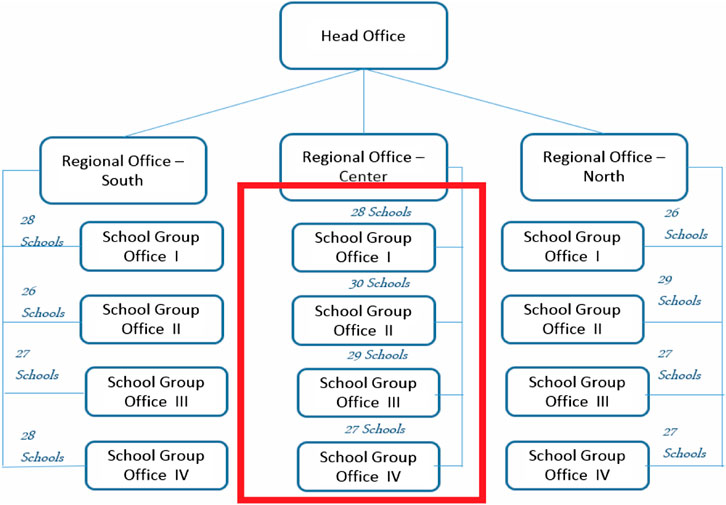

The network of BSS school branches is divided into three geographic regions namely Southern Region, Central Region and Northern Region. Policy planning, curriculum development, assessment development, and other related school management and teacher development issues are addressed at the Head Office which is situated in Lahore, Punjab. All three Regional Offices report to the Head Office. Academic and administrative support to school branches in each region is provided by four School Group Offices (SGOs). These SGOs report directly to Regional Directors (RD).

Note. The Figure 1 explains the division of regions and organizational structure and identifies the research population.

A total of fifty-seven primary school head teachers, four School Group Heads (SGHs), and two thousand eight hundred and fifty teachers comprised the overall population for this study.

Sample Size

The research is accomplished in two cycles using different sampling approaches, in the first cycle of research the Central Region was selected purposively due to the largest number of school branches operating in this region. All School Group Heads (SGHs) took part in the first cycle of research and identified one most successful primary school branch in their cluster therefore, following a subjective sampling technique. The second cycle of research was carried out at the identified branches. To maintain the anonymity of these school branches they will be referred to as School A, B, C and D. A total of one hundred and twenty teachers also participated in the second cycle of research.

Research Design

An explanatory mixed methods research design comprising of both quantitative and qualitative methods of research respectively was employed for an in-depth understanding of the case and to achieve the study objectives.

Research Instrument

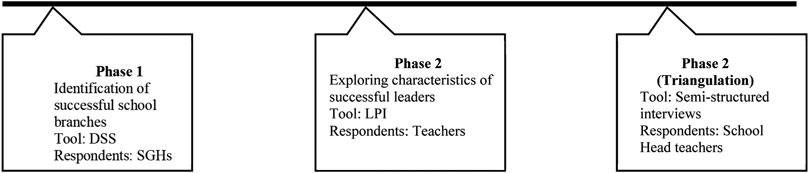

Data were collected using a mixed-methods research design that includes: two questionnaires namely Determinants of School Success (DSS) and Leadership Practice Index (LPI) were formulated on a five-point Likert scale and combined with in-depth semi-structured interviews with different stakeholders including the school head teachers and SGHs. This study was carried out in a two-phase model, the first phase explored and reported determinants of school success as perceived by the senior leadership of the school system. The second phase of research investigated the leadership traits of effective school leaders at schools perceived as “successful” based on the outcome of research phase -1. Figure 2 illustrates the phases in research design.

There is a plethora of research struggling to find an answer to what constitutes a successful school. Some researchers have strongly linked it with elevated students learning outcomes (Scheerens, 2004; Winton, 2013), others attempted to find the answer by increased reporting causes of school failure, for instance, Salmonowicz (2007) recognized fifteen conditions associated with unsuccessful schools including lack of clear focus, unaligned curricula, inadequate facilities, and ineffective instructional interventions. Edmonds (1982) offered a list of five variables correlated with school success, Lezotte (1991) evolved the list by adding two more variables: 1) instructional leadership, 2) clear vision and mission, 3) safe and orderly environment, 4) high expectations for students achievement, 5) continuous assessment of student achievement, 6) opportunity and time on task and, 7) positive home-school relations. The meaning of school success is contextual and existing research is yet to conclude a fixed list of variables that determine the success of a school.

DSS used in this research is based on five broad themes namely: positive outcomes for students, quality teaching and curriculum provision, effective leadership and school management, safe and positive school environment, quality assurance. All these variables are well supported by the existing research and have been extracted from the internal school evaluation framework of BSS. Twenty-five items inspired by Marzano Levels of School Effectiveness (2011) formulate the sub-categories of these domains. The response format on a five-point Likert scale for the items was, strongly agree = 5, agree = 4, neutral = 3, disagree = 2, strongly disagree = 1. The levels of school effectiveness suggested by Marzano (2011) fit well with the internal evaluation indicators of the high-performing school system of BSS. This method of research is new in the context of Pakistan however; evidence from internationally set-up research confirms Marzano levels of school effectiveness being utilized to study the long-term performance of schools in Oklahoma, United States (OSDE, 2011) and Ontario, Canada (Louis et al., 2010). Researchers assert that Marzano’s levels of school effectiveness “Extends our understanding of the explanatory potential of research on school performance” (Louis et al., 2010, p.8).

In the second research cycle, Leadership Practice Index (LPI) was developed by the researchers to index successful leadership qualities. LPI comprised a five-point Likert scale and the responses were collected from teachers (n = 120) in terms of frequency of demonstration of a variety of leadership qualities by the school head teacher. The format was 0 = Never, 1 = Seldom, 2 = Often, 3 = Regularly, and 4 = Routine Practice. LPI constitutes twenty-eight performance indicators for effective leadership qualities under five primary domains: personal, professional, organizational, strategic and relational. The Evidence from large-scale school-based leadership research conducted in high-performing economies such as Canada (Louis et al., 2010) and the United States (Leithwood and Jantzi, 2006) assert that these domains breakdown the knowledge of role and impact of school leadership on instruction, school performance, and students learning outcomes.

During the second cycle of research, head teachers were interviewed using a semi-structured interview style. The interview guide was divided into six overarching categories: students achievement, teaching, and learning, instructional leadership, and management, establishing the direction for the school, social links with the community, and quality assurance. A total of four interviews were conducted during this study in a traditional modality; the average interview time was 47 minutes. Ethical and practical guidelines were shared and agreed with the interviewees and all interviews were recorded, and fully transcribed before inducing for data analysis.

Pilot Study

To ensure the internal reliability and clarity of items of DSS the researchers conducted a pilot study within the same research population. From the Southern Region of the same organization School Group Heads (n = 2), School head teachers (n = 4), and primary school teachers (n = 6) were invited for the pilot the research. The questionnaire was disseminated through the Internet using Google Forms. 12 min was recorded as average time taken by respondents to attempt the questionnaire. There were no negative observations noted for language difficulty however, two items were reported to be overlapping under the section effective leadership and quality assurance. Consequent modifications in the questionnaire was made to address this discrepancy. There were no negative observations for the semi-structured interview questions developed for the school head teachers.

Data Analysis and Discussion

One hundred twenty-eight respondents participated in this multi-method study. Respondents represented various layers of organizational hierarchy complying with extant literature that asserts effective school leadership and successful achievement as a product of multi-tiered support system within the school organizational set-up that initiates at senior leadership and permeates to classroom teachers through individual school leadership (Mikesell, 2020).

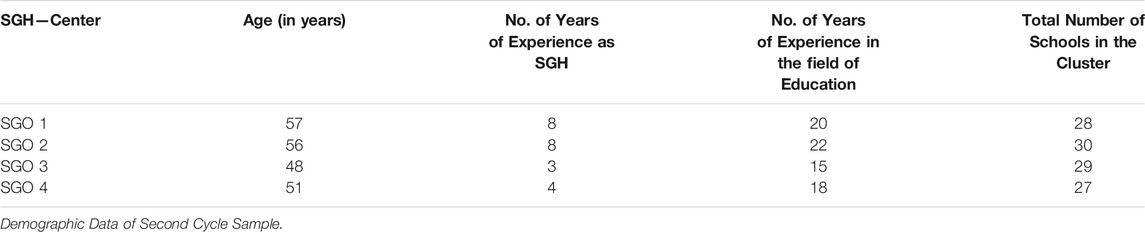

Demographic Data of First Cycle Sample.

Sample for the first research cycle comprised of four female SGHs. The demographic data defining their academic qualifications and the total number of years of professional experience is given in Table 1.

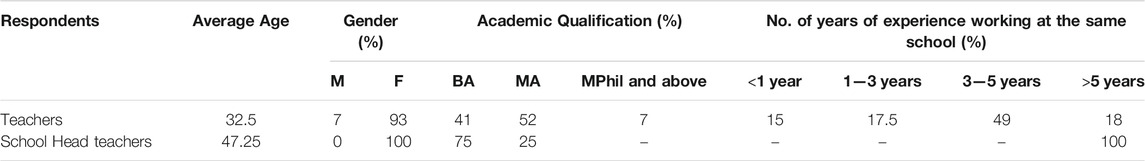

The conclusion of the first cycle of research led to the sample that took part in the second cycle of research. All teachers (n = 120) and head teachers (n = 4) of primary school branches identified as most successful by the SGHs took part in this research. Table 2 represents the demographic data about participants of this research including age, gender, academic qualification, and professional experience.

The qualitative data were analyzed using MaxQD and the quantitative data was studied using SPSS version 22 for Windows. The analysis led to the emergence of some themes common with those determined in the West. The next section details key findings from the analysis of DSS and LPI.

Research Q1: Results of DSS

The research question; what are the determinants of a successful school in the private sector of Pakistani schools was addressed through the results of DSS. All SGHs account for high students learning outcomes measured in terms of academic, co- and extra-curricular activities as the most significant determinant of a school’s success. Quality of teaching and curriculum provision has been identified as other influencing determinants and lastly, there was a consensus that effective school leadership is responsible to bring these factors together.

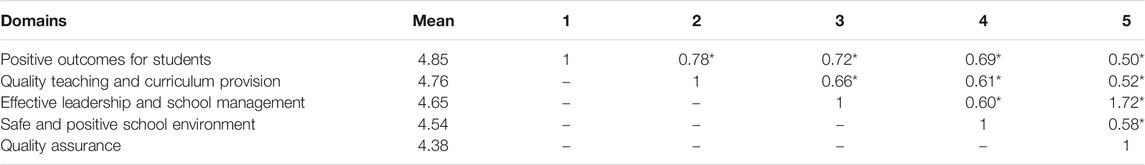

Table 3 shows the accumulative mean for all five domains of DSS in order of highest to lowest. The bivariate correlation of study variables projects a strong relationship with each other. The first domain, “Positive outcomes for students” accounts a positive relationship with all other determinants with the highest correlation with “Quality Teaching and Curriculum Provision” (r = 0.78) which asserts that teaching practices have a tremendous impact on students achievement. Analysis of results emphasizes the role of school leadership in boosting teaching and learning in classrooms with r=.66. Extensive long-term studies identify the school head teacher as the central source of school leadership (Mulford, 2003; OECD, 2013; Louis et al., 2010) that significantly impacts pupil outcomes (Leithwood et al., 2006). In this study, it is noteworthy that leadership was best correlated with “Quality Assurance” (r = 0.72) setting the significant foundation of self-evaluation and self-review. A strong culture of self-review is an indicator of thoughtful leadership (Ofsted, 2010). The interrelationship of all these variables brings effective leadership as a vital determinant of school success.

At the end of the first cycle of study, the SGHs were able to place effective school leadership at the heart of school success. This research supports the persuasive evidence present in favor of the strong influence of school leadership on school success. School success indicators presented by Hull (2012), The Wallace Foundation, (2013) and DuFour and Marzano, (2011) in different contexts and regions of the world identify pupil achievement, quality of teaching, leadership and self-review in variable order of significance. Moreover, Felix-Otuorimuo (2019) found that the practices and experiences of school leaders influenced the strategies and approaches they can use to become successful school leaders.

Research Q2: Results of Leadership Qualities Index (LQI)

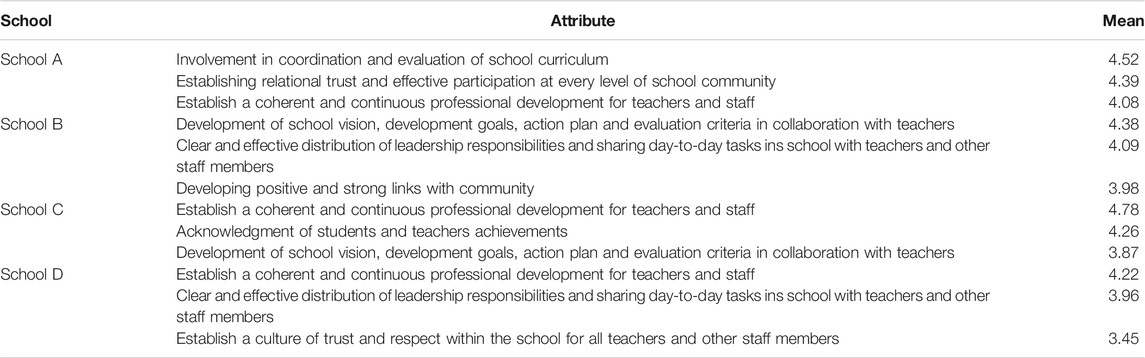

One hundred and twenty teachers from four different schools participated in the second cycle of research carried out to identify key leadership practices of school head teachers. Responses were gathered in the five levels of frequency for the demonstration of leadership practices. Table 4 presents the results of Leadership Qualities Index (LQI) calculated through SPSS and presented in an order of highest to the lowest mean score for the most prominent three leadership qualities practiced by school head teachers of four selected schools. The results of this section answer the research question; what are school head teachers leadership qualities in successful private primary schools of BSS in the province of Punjab?

Research Q3: Factor Analysis.

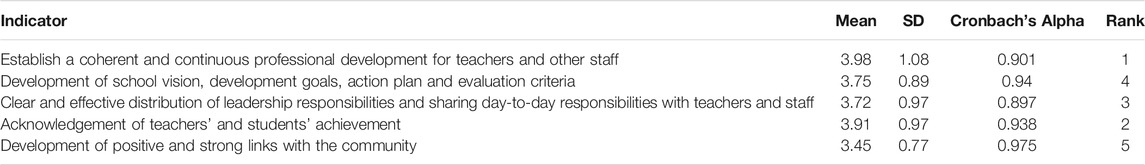

A factor analysis on Likert-type survey items involving Varimax rotation and Kaiser normalization, led the researcher to answer the research question; what are the common trends in the leadership qualities of the selected school head teachers? It determined the common leadership traits of the four successful schools. With the Varimax rotation, the indicators were uncorrelated and independent from one another (Kim and Mueller, 1982; Khan et al., 2009). With a sample size n = 120, loadings of at least 0.50 were considered significant and used to draw common attributes (Khan et al., 2009) which were pronounced as the commonly occurring leadership traits of leaders of successful primary school head teachers as shown in Table 5 and discussed in the proceeding section.

These results can be broadly divided into two types of leadership style dimensions; qualities directed towards task accomplishment, and qualities focusing on interpersonal relations (Hydon, 2007; Nystedt, 1997).

Qualities Directed Towards Task Accomplishment

Establish a Coherent and Continuous Professional Development for Teachers and Other Staff.

Analysis of this indicator reveals that all four head teachers taking part in this study rigorously planned the professional development exercises drawing upon training needs analysis, context, and school development targets. Seventy-two percent of teachers reported this aspect as a matter of routine practice for selected schools head teachers. Research tends to view leading teachers professional learning in coherence with their needs as an instructional leadership (Gumus et al., 2018; Mulford, 2007; The Wallace Foundation, 2013).

All the head teachers taking part in the second cycle of study shared their views that support the methodical agenda for teachers in-service education. Head teachers strongly connected students learning outcomes with the quality of teaching and teachers professional learning and development.

“I make sure that our school development plan projects vision of commitment to greater achievement and success for all students that come with committed teachers in my opinion, access to opportunities for continuous learning strengthens teachers as the change agents I try to create opportunities for them to take part in professional education that is embedded in their daily job life and the best of their and the school’s interest” (Head Teacher School Branch C).

Three out of four schools promoted a strong culture of mentoring and regular peer-coaching with a purpose to embed learning within daily school routines to improve the quality of teaching. In an interview, a School head teacher stated:

“high achievement comes with good teaching; good teaching comes with learning, training we don’t have enough budget for training its better when teachers learn from their colleagues, it’s practical and situational learning learning on-job from peers is the best solution for us From their senior colleagues, they learn better without any hesitation.”

One out of four head teachers maintained that teachers learning portfolios which not only provided a learning graph but also serve as a source of information for setting annual appraisal targets. Longitudinal data for teachers training needs provide school leaders an opportunity to: graph individual professional development of teachers; address the most accurate training needs; and redefine induction criteria for new teachers (Knapp and Hopmann, 2017).

Development of School Vision, Development Goals, Action Plan, and Evaluation Criteria in Collaboration with Teachers

The second leadership quality commonly identified by the analysis of qualitative and quantitative results is a shared vision. A majority of 68% of teachers identified this as a positive leadership trait possessed by their respective head teacher. Three out of four head teachers formulated an annual school development plan together with teachers to encourage individual ownership for achieving these targets. When teachers have formal roles in the decision-making processes regarding school initiatives and plans, they are more likely to perform better and take higher ownership of their decisions (DuFour and Marzano, 2011). The same was reported by the head teacher of School B “when teachers have a direct input in formulating the school development plan, they take responsibility to achieve these targets because it is their plan, not a dictated idea”. Head teachers participating in this study regularly consulted BSS school evaluation framework and engaged in rigorous self-review to keep themselves and their staff aware of school performance.

Clear and Effective Distribution of Leadership Responsibilities and Sharing Day-To-Day Tasks in School with Teachers and other Staff Members

Analysis of head teachers interviews provided strong evidence of involvement of all staff to make leadership a combined endeavor, rather than practicing a model of single leader atop the school hierarchy. Research also supports that the distribution of leadership promotes a culture of trust, high motivation and coherent vision for school development (Copland, 2003; Gronn, 2003; Spillane et al., 2005). A considerably high mean value for this indicator (3.72) and 63% of teachers vote for this leadership trait concludes it as one of the prime leadership qualities of successful school leaders. One of the head teachers from School “A” was of the view:

Heading a school is not a one-man show you know It requires joining hands together with all the stakeholders within the school premises and outside of the school I would not ignore the active engagement of parents, our academic liaison with other educational organizations, academia, and professionals of BSS and even the results of the latest research on school leadership.

Thus, the results show that the school heads believe in effective school headship as a joint venture and running the school democratically in collaboration with other relevant academic and administrative personnel of the school. It was revealed in a study conducted by Felix-Otuorimuo (2019) in Nigerian perspective that “successful primary school leadership in Nigeria is a collective and direct effort of the entire school community working together as a family unit, which cuts across the cultural and national boundaries of sub-Saharan Africa” (p. 218).

Qualities Directed Towards Interpersonal Relations

Acknowledgment of Teachers and Students Achievement

Appreciation, motivation, and empathy refer to the level of interpersonal care from senior leadership (Gurr et al., 2005). Findings of the study revealed that about 59% of teachers indicate that their school head teachers mostly or always demonstrated a motivating, encouraging and facilitating behavior to project an increase in achievement of different cohorts of teachers and students. An emerging theme from head teachers interviews sets the intention of fostering a culture of support, trust, the concept of shared achievement and a sense of sensitivity when dealing with cohorts of students and teachers struggling to produce desired results. One of the senior school heads working in School “D” reflected:

The students, teachers, parents, BSS higher authorities and the head teachers work like a community who believe in mutual help, support and appreciation. We learn from each other strengths and weaknesses and acknowledge each other’s efforts in achieving the common school goals. Achievement of a single student is the achievement of the whole team working behind him and we must appreciate them all.

They have set systems in place to acknowledge, share and celebrate students and teachers achievements. Previous researchers have also emphasized on the significance of this indicator (Day et al., 2016; Hitt and Tucker, 2016; Leithwood et al., 2017; Louis and Murphy, 2017; Leithwood and Sun, 2018). Williams (2008) reported that in high-poverty communities, successful school leaders primarily invest in relationship building focusing on individuals for collective progress. In an annual report on Education in Wales, Estyn, (2015) argues that a culture of trust, mutual empowerment, care, collaboration and genuine partnerships amongst all levels of staff serve as the driving force for effecting school improvement. Also, one of the most recent studies in this field conducted in the Nigerian perspective found that the school heads vision, trust in mutual relationship and personal belongingness established a strong relationship of school with the home and influenced the overall improvement in the school leadership (Felix-Otuorimuo, 2019).

Development of Positive and Strong Links With the Community

There are systems in place for involvement of diffused communities such as art and literary societies in the city, health service providers, and global partnerships with other international schools. Exchange of work samples, networking of parents and distant mentoring for teachers via Skype are regularly practiced at these schools. A large percentage of teachers (68%) identified the culture of developing strong links with the outer community as a reason for the success of their school, the head teacher from School “C” supported: “we are not in a closed shell, I encourage teachers to adopt good practices, as long as they add to pupil achievement, change is good for developing”. All school head teachers engaged others outside the immediate school community, including parents and the local community. Community—School partnership was a positive trend that emerged from this study; research in the international context asserts that the impact of community involvement on school success is vague (Hull, 2012). Nevertheless, a connection between school and family is an influencing factor to determine a school’s success and to improve students learning outcomes (Boyko 2015; Goodall, 2017); Dodd and Konzal, 2002; Epstein, 2001). One of the head teachers who was working in School “A” asserted her remarks in these words:

Learning does not begin when students enter the school, it begins at homes and when they walk through the school gate they bring with them culture, behaviors, language, attitudes, skills and learning from homes and when they leave here they take back knowledge, culture and values from the school, therefore, there is a strong link between children, school, and families.

The participant school heads elaborated that annual orientation sessions for parents to: keep them informed about the school development plans; curricular interventions; teacher training initiatives; and quantitative surveys to inquire parents aspirations on improving the school environment and teaching practices were some of the regular attempts at these school branches to build a better relationship with families. It was interesting to find that three out of four schools communicated with parents through an official webpage.

Conclusion and Recommendations

In relation to the existing academic literature, this study reinforces the significance of effective school leaders for students high achievement. School head teacher has the strongest impact on student achievement across life, school practices, culture and quality of performance (Boyko 2015; Böhlmark et al., 2016; Day et al., 2016; Felix-Otuorimuo, 2019; Gurr et al., 2003). Research and practice confirm that a school head teacher has a tremendous capacity to revolutionize school culture to promote success and change (Elmore, 2002; Louis et al., 2010; Leithwood et al., 2019). Findings of this study synthesize that head teachers of the most successful primary school branches of BSS:

• had established a whole-school approach towards students high achievement;

• promoted a culture of trust, commitment, shared vision and celebrate achievement at all levels of hierarchy in the school;

• practiced distributed leadership and promote a culture of sharing;

• involved all stakeholders in creating a shared sense of direction for the school;

• prioritized teachers professional development by setting contexts for learning and creating opportunities for learning embedded in day-to-day campus-life; and

• practiced democratic leadership style and worked towards building positive links with the community.

The repertoire of effective leadership practices presented in existing academic literature encompasses the findings reported by this study. Research categorizes leadership development as a lifelong learning process (Hull, 2012), the researchers make the following recommendations that contribute more to school success:

Provision of Training

Although there was no standard approach to the provision of leadership development the Beaconhouse School System should organize in-service programs for school head teachers concerning their school context. When there are no other prerequisites, strong in-service programs should encourage the development of advanced leadership skills. Three out of four school head teachers who participated in this research did not have 16 years of education, on a larger scale school senior leadership teams should be encouraged to uplift their academic qualifications to keep abreast of modern educational trends.

Sharing of Good Practices

For a vast network of school systems underpinned by identical vision, philosophy and standard operating procedures; the Beaconhouse School System should promote the culture of sharing of good practices of successful schools to promote excellence across the system.

Lessons for Other Schools

These recommendations are specifically supportive for further improvement of the school leadership and consequently school success for the BSS- one of the largest private school networks in the country. Nevertheless, the results of the study have implications for the other competitive private school networks that share common characteristics of school headship. Some of the results may be useful for the primary schools being governed and managed by the government of Punjab in Pakistan.

Findings from this study my serve like a blueprint for low-cost private schools to establish systems for in-house teachers professional development, strategic school improvement planning, monitoring and evaluation, and create a sense of school community in collaboration with multi-stakeholders. This study has opened several avenues for other private schools to explore, contextualize and advance towards a systematic leadership program within their organization.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

MR conceived of the idea, worked on research design and collected data. She conducted a preliminary analysis, and outlined major parts of the manuscript. NG, and SW conducted additional interviews to saturate the data, analyzed the interview transcripts and finalized the draft for submission. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Andrabi, T., Das, J., and Khwaja, A. I. (2008). A dime a day: The possibilities and limits of private schooling in Pakistan. Comp. Edu. Rev. 52 (3), 329–355. doi:10.1086/588796

Andrabi, T., Das, J., and Khwaja, A. I. (2013). Students today, teachers tomorrow: Identifying constraints on the provision of education. J. Public Econ. 100, 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2012.12.003

Baig, S. (2011). The personal values of school leaders in Pakistan: A contextual model of regulation and influence. J. Values-Based Leadersh. 4 (2), 26.

Böhlmark, A., Grönqvist, E., and Vlachos, J. (2016). The headmaster ritual: The importance of management for school outcomes. Scand. J. Econ. 118 (4), 912–940. doi:10.1111/sjoe.12149

Boyko, A. I. (2015). Socio-philosophical analysis of the problems and leadership in the field of science. Perspect. Philos. 1 (63), 25–30.

Copland, M. A. (2003). Leadership of inquiry: building and sustaining capacity for school improvement. Educ. Eval. Pol. Anal. 25 (4), 375–395. doi:10.3102/01623737025004375

Day, C., Gu, Q., and Sammons, P. (2016). The Impact of Leadership on Student Outcomes. Educ. Adm. Q. 52 (2), 221–258. doi:10.1177/0013161x15616863

Dodd, A. W., and Konzal, J. L. (2002). How communities build stronger schools: Stories, strategies and promising practices for educating every child. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-0-230-60214-4

DuFour, R., and Marzano, R. J. (2011). Leaders of learning: How district, school, and classroom leaders improve student achievement. Bloomington: Solution Tree Press.

Education Review Office (2018). Evaluation at a glance: A decade of assessment in New Zealand primary schools - Practice and trends. Wellington, New Zealand: Education Review Office.

Elmore, R. F. (2002). Bridging a New Structure for School Leadership. Washington, DC: Albert Shanker Institute. doi:10.2514/6.2002-t2-52Available online at: http://www.shankerinstitute.org/education.html

Epstein, J. L. (2001). School, family, and community partnerships: Preparing educators and improving schools. Colorado: Westview Press.

Estyn (2015). The Annual Report of Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Education and Training in Wales 2013-2014. Cardiff: Estyn. [Online]. Available from: http://www.estyn.gov.uk/english/annual-report/annual-report-2013-2014.

Felix-Otuorimuo, I. (2019). The qualities, values, skills and strategies of successful primary school leaders: Case studies of two primary school head teachers in Lagos, Nigeria (doctoral dissertation). England: University of Nottingham.

Fullan, M. (2001). Leading in a culture of change. San Francesco: Jossey-Bass. doi:10.4324/9780203986561

Goodall, J. (2017). Narrowing the achievement gap: Parental engagement with children’s learning. New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315672465

Gronn, P. (2003). Leadership: Who needs it? Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 23 (3), 267–291. doi:10.1080/1363243032000112784

Gumus, S., Bellibas, M. S., Esen, M., and Gumus, E. (2018). A systematic review of studies on leadership models in educational research from 1980 to 2014. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 46 (1), 25–48.

Gurr, D., Drysdale, L., and Mulford, B. (2005). Successful principal leadership: Australian case studies. J. Educ. Admin 43 (6), 539–551. doi:10.1108/09578230510625647

Hitt, D., and Tucker, P. (2016). Systematic review of key leader practices found to influence student achievement. Rev. Educ. Res. 86 (2), 531–569.

Hull, J. (2012). The principal perspective: Full report. Alexandria: Center for Public Education. Retrieved April 13, 2020 from http://www.centerforpubliceducation.org/principalperspective.

Iqbal, M. (2005). A comparative study of organizational structure, leadership style and physical facilities of public and private secondary schools in Punjab and their effect on school effectiveness (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Lahore: Institute of Education & Research, University of Punjab.

Johnson, R. B., and Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2004). Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educ. Res. 33 (7), 14–26. doi:10.3102/0013189x033007014

Khan, S. H., Saeed, M., and Fatima, K. (2009). Assessing the Performance of Secondary School Headteachers. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 37 (6), 766–783. doi:10.1177/1741143209345572

Kim, J. O., and Mueller, C. W. (1982). Factor analysis statistical methods and practical issues. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Knapp, M., and Hopmann, S. (2017). “School leadership as gap management: Curriculum traditions, changing evaluation parameters, and school leadership pathways,” in Bridging Educational Leadership, Curriculum Theory and Didaktik. Educational Governance Research. Editors M. Uljens, and R. Ylimaki (Cham: Springer).

Leithwood, K., Day, C., Sammons, P., Harris, A., and Hopkins, D. (2006). Successful school leadership: What it is and how it influences pupil learning. London: DfES and Nottingham: NCSL.

Leithwood, K., Harris, A., and Hopkins, D. (2019). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership revisited. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 40 (1), 5–22. doi:10.1080/13632434.2019.1596077

Leithwood, K., and Jantzi, D. (2006). Transformational school leadership for large-scale reform: Effects on students, teachers, and their classroom practices. Sch. Effectiveness Sch. Improvement 17 (2), 201–227. doi:10.1080/09243450600565829

Leithwood, K., and Sun, J. (2018). Academic culture: A promising mediator of school leaders’ influence on student learning. J. Educ. Adm. 56 (3), 350–363.

Leithwood, K., Sun, J., and Pollock, K. (2017). How school leadership influences student learning: The four paths. Netherlands: Springer.

Lezotte, L. (1991). Correlates of effective schools: The first and second generation. Okemos, MI: Effective Schools Products, Ltd.

Louis, K. S., Leithwood, K., Wahlstrom, K., Anderson, S., Mascall, B., Michlin, M.,, et al. (2010). Learning from districts’ efforts to improve student achievement. New York: Report to the Wallace Foundation.

Louis, K. S., and Murphy, J. (2017). Trust, caring and organizational learning: the leader's role. Jea 55 (1), 103–126. doi:10.1108/jea-07-2016-0077

Mikesell, J. M. (2020). Multi-Tiered Systems of Support and School Leadership in HighAchieving Pennsylvania Schoolwide Title 1 Elementary Schools. Texas: Abilene Christian University Press. Retrieved July 8, 2021from https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1292&context=etd.

Mulford, B. (2007). An overview of research on Australian educational leadership 2001-2005. Winmallee, NSW: Australian Council for Educational Leaders.

Mulford, B. (2003). School leaders: Changing roles and impact on teacher and school effectiveness. Paris: OECD.

Nguyen, Q. T., and Raju, D. (2014). “Private school participation in Pakistan,” in Policy Research working paper No. 6897 (Washington, DC: World Bank). doi:10.1596/1813-9450-6897

Nystedt, L. (1997). Who should rule? Does personality matter? Eur. J. Pers. 11, 1–14. doi:10.1002/(sici)1099-0984(199703)11:1<1::aid-per275>3.0.co;2-h

Ofsted (2010). Good professional development in schools. Manchester: Ofsted. Retrieved April 13, 2020, from https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/1109/1/Good%20professional%20development%20in%20schools.pdf.

Osseo-Asare, E., Longbottom, D., and Murphy, D. (2005). Leadership best practices for sustaining quality in UK higher education from the perspective of the EFQM Excellence Model Augustus. Qual. Assur. Edu. 13 (2), 148–170.

Salfi, N. A. (2011). Successful leadership practices of head teachers for school improvement. J. Educ. Admin 49 (4), 414–432. doi:10.1108/09578231111146489

Salmonowicz, M. J. (2007). Scott O'Neill and Lincoln Elementary School. J. Cases Educ. Leadersh. 10 (2), 28–37. doi:10.1177/1555458907301439

Scheerens, J. (2004). “The meaning of school effectiveness,” in Presentation at the 2004 summer school (Oporto, Portugal: ASA Publishers).

Spillane, J., Diamond, J., Sherer, J., and Coldren, A. (2005). “Distributing Leadership,” in Developing leadership: Creating the schools for tomorrow. Editors InnM. Coles, and G. Southworth (New York: OU Press).

The Wallace Foundation (2013). The school principal as leader: Guiding schools to better teaching and learning. New York, NY: The Wallace Foundation. from http://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/schoolleadership/effective-principal-leadership/Pages/The-School-Principal-as-LeaderGuiding-Schools-to-Better-Teaching-and-Learning.aspx (Retrieved April 13, 2020).

Williams, H. W. (2008). Characteristics that distinguish outstanding urban principals: Emotional intelligence, social intelligence and environment adaptation. J. Manag. Dev. 27 (1). doi:10.1108/02621710810840758

Keywords: leadership qualities, private school, successful school leadership, school success, primary school leaders

Citation: Raza M, Gilani N and Waheed SA (2021) School Leaders' Perspectives on Successful Leadership: A Mixed Methods Case Study of a Private School Network in Pakistan. Front. Educ. 6:656491. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.656491

Received: 20 January 2021; Accepted: 26 July 2021;

Published: 17 August 2021.

Edited by:

Osman Titrek, Sakarya University, Sakarya, TurkeyReviewed by:

Nukhba Zia, Johns Hopkins University, United StatesFakhra Yasmin, South China Normal University, China

Copyright © 2021 Raza, Gilani and Waheed. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Syed Abdul Waheed, cy5hLndhaGVlZEB1by5lZHUucGs=

Mehwish Raza

Mehwish Raza Nadia Gilani2

Nadia Gilani2 Syed Abdul Waheed

Syed Abdul Waheed