- Ecological Approaches to Social Emotional Learning Laboratory, Harvard Graduate School of Education, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, United States

As the positive impact of social emotional learning (SEL) has become widely recognized, there is increasing demand for SEL programs to address the diverse cultures, identities, and experiences of all students in the classroom, in particular students of color and other youth impacted by structural inequality. SEL programs increasingly provide resources and guidance to ensure that diverse students are represented in materials and content and to help educators understand how culture plays a role in the development and expression of SEL competencies. However, few programs are intentionally designed with equity in mind and even fewer examine how historical and structural inequalities impact both the teaching and learning of SEL skills. While many believe that SEL is well-positioned to play a role in creating learning environments where students of all cultures, races, identities, and backgrounds feel safe, respected, and empowered, the link between equity and SEL is not always clear. Furthermore, despite existing well-established, research-grounded practices from which to draw in other fields, the field of SEL currently lacks a coherent and unified definition of what constitutes equitable SEL and what equitable SEL looks like in the classroom. As schools and other educational settings strive toward creating more equitable learning environments for students, the field of SEL needs a clearer viewpoint and explicit practices describing how equity can be better integrated into SEL programming and practice. This paper describes the need for equitable SEL, summarizes existing research and practices, and provides a set of recommendations for implementing them effectively in schools and other educational settings. We begin with a brief exploration of the relationship between educational equity and SEL, describing the potential for SEL to create more equitable, inclusive, and just learning environments. Next, we present key perspectives from the literature that shape current views on how issues of equity can be integrated into SEL programming and practice, proposing a set of principles and definition for equitable SEL. Finally, we discuss the current state of PreK-5 SEL programs, using findings from a content analysis to describe the extent to which programs address equity in lessons and promote transformative SEL skill building.

Introduction

Social and emotional learning, or SEL, refers to the process through which individuals learn and apply a set of social, emotional, and related skills, attitudes, behaviors, and values that help direct their thoughts, feelings, and actions in ways that enable them to succeed in school, work, and life (Jones et al., 2017a). Research indicates that when implemented effectively, high-quality, evidence-based SEL programs have positive impacts on children’s social, emotional, behavioral, and academic outcomes as well as teacher practices and the culture and climate of schools (Diamond et al., 2007; Bierman et al., 2008; Raver et al., 2009; Brown et al., 2010; Durlak et al., 2011; Jones et al., 2011; Sklad et al., 2012). Nevertheless, some have raised questions about the relative value, meaning, and efficacy of SEL programs for diverse populations, including students of color and other youth impacted by structural inequality in the United States (Simmons et al., 2018; Jagers et al., 2019). In addition, some recent work has been directed toward examining whether SEL programs effectively support the well-being of all students by sufficiently reflecting, affirming, and sustaining their cultural identities in the classroom (Castro-Olivo, 2014).

SEL programs increasingly provide resources and guidance to ensure that diverse students are represented in materials and content and to help educators understand how culture plays a role in the development and expression of SEL competencies. However, few programs are intentionally designed with equity in mind and even fewer examine how historical and structural inequalities impact both the teaching and learning of SEL skills. While many believe that SEL can play a role in creating learning environments where students of all cultures, races, identities, and backgrounds feel safe, respected, and empowered, the link between equity and SEL is not always clear. Furthermore, despite existing, well-established, research-grounded practices from other fields on which to draw, the field of SEL currently lacks a coherent and unified definition of what constitutes equitable SEL and what equitable SEL looks like at the classroom level. As schools and other educational settings strive toward creating more equitable learning environments for all students, the field of SEL needs a clearer viewpoint and explicit practices describing how equity can be better integrated into SEL programming and practice.

With this in mind, this paper addresses three questions: 1) What is the relationship between educational equity and SEL in the United States?, 2) How can we define equitable SEL for the United States context?, and 3) How are existing SEL programs addressing issues of equity and what are areas of strength and opportunities for growth? This paper begins with a brief exploration of the relationship between educational equity and SEL, describing the potential for SEL to create more equitable, inclusive, and just learning environments. Next, we present key perspectives from the literature that shape current views on how equity can be explicitly and intentionally integrated into SEL programming and practice, proposing set of principles and definition for equitable SEL. We then discuss the current state of SEL programs designed for early childhood and elementary-age students, using findings from a recent content analysis of SEL programs to describe the extent to which they address equity in lessons and promote transformative SEL skill building in young children. Finally, we conclude with a discussion of our findings, their limitations, and implications for SEL practice.

What is the Relationship Between Social Emotional Learning and Educational Equity in the United States?

Defining Educational Equity

In the field of education, the term “equity” is often viewed in conflicting ways and at times used as a label, goal, or decision-making lens without clear definition or operationalization (Osher et al., 2020). Furthermore, the terms “equity” and “equality” are often used interchangeably despite having important distinctions. Equality refers to what is fair for the group, focusing on providing access to the same opportunities to everyone despite specific needs. Equity, on the other hand, attempts to identify the specific needs of those within the group, focusing on what is fair for the individual. Common themes among definitions of equity include universal access to high-quality educational opportunities, fairness, inclusion, and the eradication of discriminatory practices and prejudice within the education system (The Aspen Education & Society Program and the Council of Chief State School Officers, 2017; NSBA, 2019). In the United States, the need to address pervasive ethnic and racial disparities directly within the educational system has also become a primary focus of conversations on advancing educational equity (de Brey et al., 2019; Morgan and Amerikaner, 2018; NEA, 2020; Pearman et al., 2019; U.S. Department of Education, 2016). Recently, the Black Lives Matter movement and nationwide uprisings against police brutality have led to a significant shift in conversations about how to address racial inequality and structural inequity in education. The recent focus on race has led to a closer examination of inequities that exist in schools and an increase in educators—particularly White educators—who see the need to makes changes to their own practice.

Given the above, we define educational equity for the United States context as the intentional counter to systemic and institutionalized inequality, privilege, and prejudice in the education system and the simultaneous promotion of conditions that support the well-being of students who most experience inequity and injustice. This conceptualization is derived from Osher et al. (2020) description of robust equity, which combines commonly accepted aspects of educational equity like fairness and inclusion with the broader, more expansive systems-focused approach to racial equity which includes dismantling systems of oppression and addressing the legal, political, social, cultural, and historical contributors to inequity that exist within broader societal and institutional structures in the United States.

While some aspects of equity in United States education must be addressed at a systems level (e.g., school disciplinary policies, hiring practices and diversity recruitment, student tracking and ability grouping, etc.), we focus on SEL practices that can be put into action by individual schools and other educational settings to create more equitable learning environments for all students. Equity-oriented practice at the school level includes 1) ensuring equally high outcomes for all students and making certain that success and failure are no longer linked to student identity—racial, cultural, economic, or otherwise; 2) interrupting inequitable practices, examining biases, and creating inclusive multicultural learning environments for all adults and children; and 3) discovering and cultivating the unique gifts, talents, and interests of every student (National Equity Project, 2020). Equitable schools work toward delivering the educational experiences that students need and deserve, particularly students of color and other youth impacted by structural inequality. Equity-oriented practice improves opportunities and outcomes for all children regardless of background or situation (Braveman and Gottlieb, 2014; Simmons et al., 2018), but is of particular significance for those furthest from opportunity, including students of color, English language learners, low-income students, students with disabilities, and other youth impacted by structural inequality (Jagers et al., 2019).

Alignment Between Educational Equity and Social Emotional Learning

In order to create respectful, inclusive, and responsive learning environments that benefit all students, it is essential to consider the link between educational equity and students’ social and emotional development. The relationship between SEL and educational equity is reciprocal: SEL can advance the aims of educational equity by supporting all students to feel welcome, seen, and competent at school. At the same time, an intentional focus on equity enhances SEL practice by ensuring that SEL is relevant, accessible, and beneficial for all students. In fact, high-quality SEL programs facilitate and rely upon many of the same practices that contribute to more equitable and inclusive learning environments, such as 1) fostering a caring and just culture and climate; 2) building student voice and agency; 3) cultivating understanding and respect for cultural differences; and 4) emphasizing asset-based approaches to skill development.

Yet while SEL as an approach is well-positioned to create more equitable schools and learning environments, SEL is not by definition equitable, nor does it inherently promote equity. Many scholars argue that to truly support the growth and development of all students, SEL must also intentionally counter inequality, institutional privilege and prejudice, and the systems of oppression that hinder and harm students of color and other youth impacted by structural inequality (Gregory and Fergus, 2017; Aspen, 2018; Jagers et al., 2018; Simmons et al., 2018; Jagers et al., 2019; Weaver, 2020). Although elements of effective SEL programming may support and align with equitable learning practices, that does not guarantee that SEL programming always affirms and incorporates diverse cultures and identities, builds student voice and agency, and explicitly confronts and works to disrupt power and privilege. Indeed, some SEL programming has been criticized for not feeling relevant or relatable to students of color because it reinforces the behavioral, social, and cultural norms prioritized by dominant groups—especially those of white, middle-class society—without taking into consideration the values and experiences of diverse populations (Simmons, 2017; Brion-Meisels et al., 2019; Jagers et al., 2019). Without an explicit and intentional consideration of how culture and power structures impact social and emotional skill development, educational settings run the risk of unknowingly using SEL to push students to conform to dominant cultural practices in ways that conflict with or erase their own cultural identity or their own experiences with and feelings about the world (Brion-Meisels et al., 2019; Love, 2019; Stearns, 2019). When used as a tool to confront systemic inequality head on, SEL can empower students to think critically and strategically about their circumstances and the world in which they live; develop students’ ethnic, racial, and social identities; build students’ self-efficacy and agency; and draw heavily on funds of knowledge from within local communities, many of which have their own well-established practices for emotion regulation, self-care, communication, and collective wellbeing.

What is Equitable Social Emotional Learning?

In recent years, leading SEL researchers have proposed ways that SEL can be designed and implemented equitably, drawing from scholars in the fields of social justice and anti-bias education and culturally responsive and culturally sustaining pedagogies who have been leading this work for many decades. These fields, while distinct from that of SEL, offer well-established, research-grounded practices that can inform a more equitable approach to SEL. Below we present several of these perspectives that shape current views on how equity can be explicitly and intentionally integrated into SEL programming and practice: 1) SEL through the lens of culturally sustaining pedagogies, 2) social justice-oriented SEL, 3) transformative SEL, and 4) trauma-sensitive SEL. We then identify general principles of equitable SEL that are common across the four approaches and propose a definition for equitable SEL.

Social Emotional Learning Through the Lens of Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies

High-profile SEL programs often prioritize skill development and minimize the exploration of students’ cultural assets (Jagers, 2016; Simmons, 2017). Although many SEL programs touch upon the topics of diversity and inclusion, they often frame diversity as acceptance of differences rather than explicitly discussing diversity as an asset and few programs specifically discuss cultural diversity, focusing instead on surface level differences such as individual likes and dislikes. One way to counter this is to approach SEL through the lens of culturally sustaining pedagogies, which rely heavily on student, family, and community cultural assets to inform curricula and instructional strategies. Culturally sustaining pedagogies go beyond the acceptance or tolerance of students’ cultural practices common to many SEL programs and move toward explicitly supporting aspects of their languages, literacies, and cultural traditions that may have been damaged, unacknowledged, or erased in schools (Paris, 2012; Paris and Alim, 2017). Culturally sustaining pedagogy and related models, including culturally relevant (Ladson-Billings, 1995) and culturally responsive (Gay, 2010) teaching, focus on curricula and classroom practices that foster connection and reflection between academic content and students’ cultural assets and cultural references (Jagers et al., 2019). In the field of SEL, this translates into fostering cultural well-being, racial and ethnic identity development, and safe and inclusive learning environments that explicitly connect SEL concepts to the lives of the students in the classroom (Hammond & Jackson, 2015; Darling-Hammond, 2017; Immordino-Yang et al., 2018; Cantor et al., 2019). SEL through the lens of culturally sustaining pedagogies is a more equitable approach to SEL because it purposefully celebrates and honors the diverse linguistic and cultural values and practices of communities as it builds SEL competencies like social awareness and self-awareness (Jagers et al., 2019).

Practices that support culturally sustaining SEL include 1) participatory norm-setting and inclusive norms, structures and routines; 2) cooperative and community-based learning; 3) restorative disciplinary practices; and 4) the use of multicultural and multimodal instructional materials, strategies, and content (e.g., storytelling and personal narratives, art, dance, and music) that incorporate students’ histories, heritages, cultures, and experiences without stereotyping students or neglecting and oversimplifying their experiences (Gay, 2013; Brion-Meisels et al., 2019). Brion-Meisels et al. (2019) also point to the important role of adults in creating empowering and culturally sustaining learning environments for children. They recommend that schools and other educational settings form strong partnerships with families and communities to help identify culturally-salient skills, and support adults to understand SEL skills and the variety of ways in which they might be expressed across cultures and individual students. In addition, they identify three adult competencies that are central to facilitating culturally sustaining SEL in the classroom: 1) building critical self-awareness, which occurs when educators monitor their practices, behaviors, emotions and interactions through a self-reflective and critical lens; 2) building warm, demanding, and reciprocal relationships; and 3) shifting power to students by giving them a voice and choice in their learning. Although practitioners may have limited control over the content of SEL programs, building these competencies in educators empowers them to adapt lessons and learning environments in ways that are culturally sustaining, supportive, and transformative for students.

A Social Justice-Oriented Approach to Social Emotional Learning

Many SEL programs touch on concepts related to treating others with fairness and respect regardless of differences, celebrating diversity in the classroom, and contributing to positive change in the community but few explicitly discuss how these topics are related to issues of identity, power, and structural injustice. Some argue that SEL can only be positioned as equitable to the extent that it advances resistance to oppression and directly addresses systems of power and privilege (Jagers, 2016; Simmons, 2019). SEL programming can provide a good opportunity to address issues of inequity by helping students build skills related to both prejudice reduction and collective action, including critical thinking and conflict resolution skills, perspective-taking and empathy, and civic and ethical values (Learning for Justice, 2017). Social justice-oriented SEL builds on the principles of social justice education, which pay careful attention to the systems of power and privilege that give rise to social inequality and aim to help students develop a social and political consciousness, a sense of agency, and positive social identities (Gutstein, 2003; Dover, 2009).

Social justice-oriented SEL specifically seeks to foster children’s social and emotional development using participatory and inclusive practices that focus on critical thinking, social justice advocacy, and positive identity development. This approach to SEL positions students as agents of change, with empathy for those who suffer from oppression and a commitment to improving local conditions (Ginwright and Cammarota, 2002; Banks, 2004; Cammarota and Romero, 2011). Practices that support socially just SEL include: 1) situating SEL lessons in and teaching about activism, power, and inequity in schools and society; 2) helping students understand and appreciate their own identities without devaluing others; 3) encouraging students to find the ways we are all connected and deserving of respect; 4) teaching students to recognize injustice, and showing them how to act against it; 5) maintaining high expectations for both students and adults; 6) acknowledging, valuing, and building upon students’ existing knowledge and interests; and 7) recognizing and correcting biases in SEL assessment and curricula (Dover, 2009; Learning for Justice, 2018).

Transformative Social Emotional Learning

Currently, social emotional learning goals and developmental outcomes tend to focus on personally responsible citizenship, and while engaged citizens are important to the health of democratic societies, Jagers et al. (2019) argue that it is worth reframing the goal of SEL to prepare students for not only engaged but also critical citizenship. Transformative SEL, a concept introduced by Jagers, Rivas-Drake, and Borowski in 2018, incorporates aspects of both social justice education and culturally sustaining pedagogies into an approach that infuses all aspects of SEL practice with a robust focus on identity, agency, belonging, and engagement. In transformative SEL, respectful relationships between students and teachers form the groundwork for the critical examination of the causes of inequity, and collaborative problem-solving is championed as a means of acting on community and societal issues related to power and privilege, prejudice and discrimination, social justice and empowerment, and self-determination.

This approach to SEL seeks to connect SEL content and skills to students’ existing knowledge and experiences, provides students with opportunities to learn about their own and other cultures, and encourages students to reflect on their own lives and society, all in ways that are grounded in an understanding of current and historical power structures. Strategies that incorporate youth voice, participation, and collaborative problem-solving and decision-making into SEL efforts, such as project-based learning and youth participatory action research allow students to practice and build transformative SEL skills that encourage youth autonomy and leadership for social change (Jagers et al., 2018; Jagers et al., 2019).

A Trauma-Sensitive Approach to Social Emotional Learning

Trauma is an emotional or psychological response to one or more highly stressful experiences that undermine an individual’s sense of safety, stability, and security—including living with the everyday effects of pervasive, systemic stressors like racism, discrimination, community violence, and multi-generational poverty (Center on the Developing Child, 2018). While children from all backgrounds can experience trauma, those growing up in poverty are at a higher risk, as are children with disabilities, children from racial/ethnic minority groups, children who identify as LGBTQ, and children who have immigrated from another country (Craig, 2008; Gerrity and Folcarelli, 2008; Santiago et al., 2018). For this reason, issues of trauma are closely linked to issues of equity, and many argue that for SEL to be truly equitable, it must also be trauma-informed.

Combining the principles of trauma-informed practice and high-quality SEL, trauma-sensitive SEL aims to establish safe spaces where students who have experienced adversities and trauma feel welcome and supported, can explore their identities, exercise choice and agency, build positive and healthy relationships with both peers and adults, and can access the mental health supports they need without risking re-traumatization (TransformEd, 2020). Trauma-sensitive SEL practices include: 1) creating predictable routines that help students adapt to transitions throughout the day; 2) building strong and supportive relationships; 3) developing student agency by ensuring students feel seen and heard, including not forcing them to participate in activities they find triggering, and providing opportunities for them to feel competent and confident; 4) supporting the development of student and adult self-regulation skills; and 5) engaging in individual and community identity development, including strengthening one’s own identity and understanding the perspectives of others. It is also important to be thoughtful about the ways in which SEL content itself is delivered to children exposed to trauma by 1) educating staff on the signs and symptoms of trauma; 2) preparing them to effectively plan for and respond to the potentially intense emotions that might arise during SEL lessons; and 3) providing them with resources to monitor and maintain their own wellbeing (Jones et al., 2021).

Finally, it is essential to note the importance of responding to trauma in ways that are culturally relevant and sustaining. Schools and other educational settings should seek to 1) minimize and address trauma in ways that are consistent with the cultural norms and healing practices of children and their families; 2) leverage students’ unique strengths and cultural assets; 3) provide opportunities for students to explore, celebrate, and develop their sociocultural identities; and 4) recognize and address issues that arise from historical trauma and societal oppression like stereotypes, bias, and educational practices and policies that disproportionately impact specific groups of students and add to traumatic stress (SAMHSA, 2014; TransformEd, 2020; Wolpow et al., 2016; NCTSN, 2017; Hebert et al., 2019).

Proposed Principles and Definition of Equitable Social Emotional Learning

Looking across the four approaches summarized above, common principles embodied by culturally-sustaining, social justice-oriented, transformative, and trauma-sensitive SEL include: 1) ensuring safe and inclusive learning environments that are respectful and affirming of diverse identities; 2) recognizing and incorporating student cultural values, practices, and assets; 3) fostering positive identity development; 4) promoting student agency and voice; and 5) explicitly addressing issues of bias, power, and inequality at multiple levels (classroom, school, systems) and working to disrupt them. Based on these principles, we define equitable SEL as an approach to SEL that incorporates the cultural knowledge, experiences, and assets of students from diverse families and communities, and acknowledges and addresses the social injustices, inequalities, prejudices, and exclusions that students face.

How Do PreK-5 Social Emotional Learning Programs Currently Support Equitable Social Emotional Learning?

As the field of SEL grapples with how issues of educational equity can be integrated into SEL programming and practice, some programs and organizations are beginning to incorporate more equitable framing and practices into their work (e.g., Sanford Harmony, 4Rs, Girls on the Run, RULER, etc.). However, research suggests that in general, most SEL programs lack specificity and definition in their attempt to incorporate culture and diversity (Caldarella et al., 2009; Durlak et al., 2011) and that, despite diverse characteristics of the student population, SEL programming itself tends to remain static (Desai et al., 2014). Furthermore, while many SEL programs include concepts related to fairness, respect, diversity, and social responsibility, few explicitly address how these topics relate to issues of identity, power, and structural injustice.

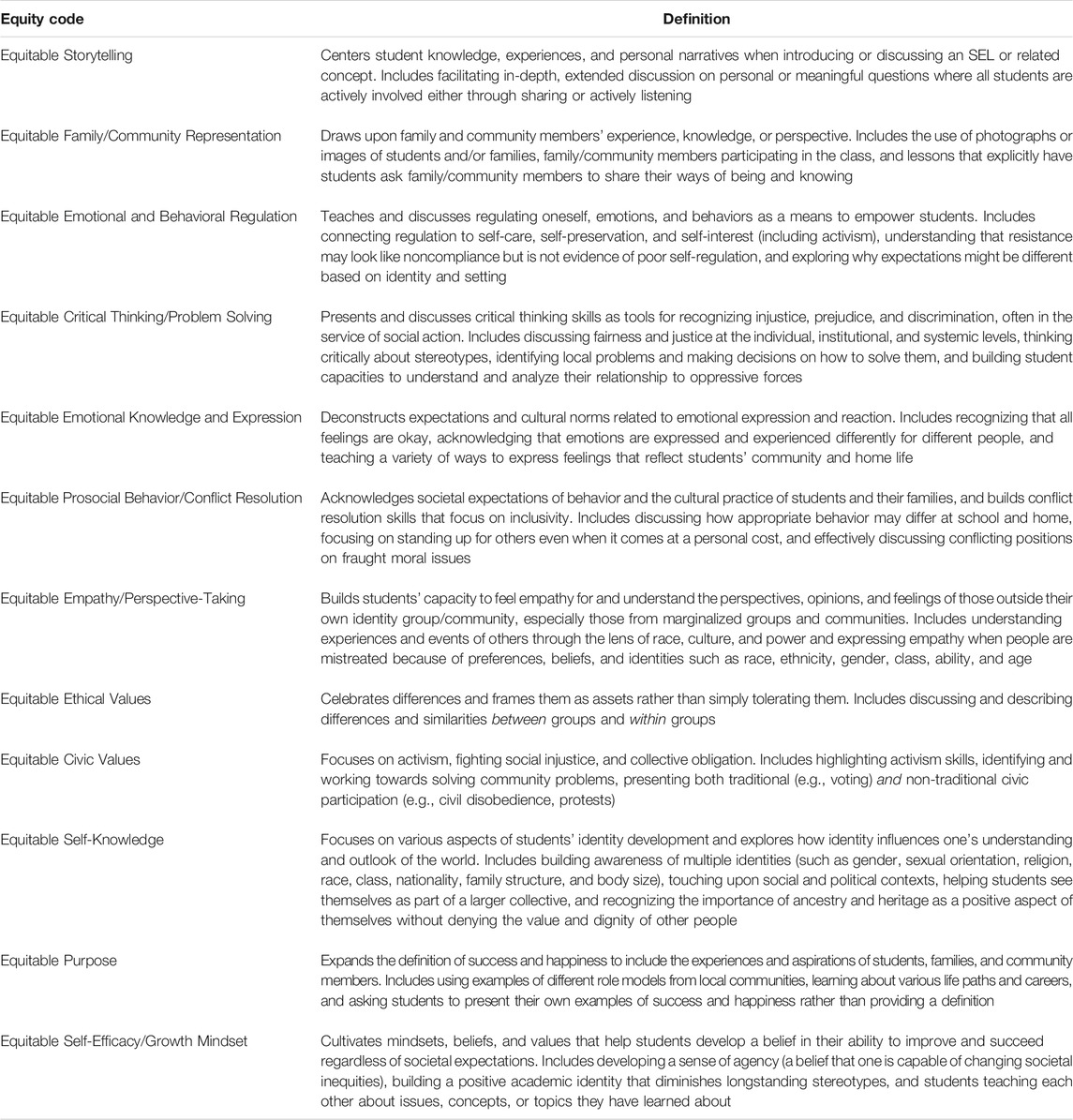

We conducted a content analysis of 33 widely-used PreK-5 SEL programs to better understand the extent to which SEL programs are designed to promote equity (Jones et al., 2021). To begin, we developed an equity coding system that is based upon a review of the literature in asset-based pedagogies and critical theory and aligned with the developmental and prevention science literatures on social and emotional development The coding system allowed our team to capture the extent to which lessons incorporate equitable practices that promote transformative SEL skill-building across the 12 categories outlined in Table 1. These categories represent a variety of skills and practices that empower students to 1) think critically and strategically about their circumstances and the world in which they live; 2) develop their ethnic, racial, and social identities; and 3) build their self-efficacy and agency. In addition to this, we used a standardized process to collect and summarize information about high-level program features including guidance, tips, and resources SEL programs provide to ensure their materials and content are relevant to students of all backgrounds, cultures, and educational needs.

The following sections present the methods and findings from the content analysis. We first describe the development of the equity coding system, the identification and selection of programs for coding, and the process for data collection and analysis at two levels, the lesson-level and program-level. Next, we discuss our findings, which provide a snapshot of how Pre-K SEL programs are currently addressing equity at the lesson-level and the program-level. We begin by highlighting resources outside of lessons that programs are providing to address equity and then share how equity appears in SEL lessons, calling out areas of success and opportunity and presenting examples of programs doing exemplary work. Next, we discuss what is typically missing from SEL programs, highlighting the codes that were found least commonly across SEL lessons. Finally, we discuss the limitations of the content analysis.

Content Analysis Methods

Development of Equity Coding System

The development of the equity codebook involved a hybrid approach of qualitative methods of content analysis whereby an existing coding system of common social and emotional skills (Jones et al., 2017b) was used to organize a review of the literature to begin, but where novel themes were also allowed to emerge during this initial review process and during the analyses itself (Fereday and Muir-Cochrare, 2006). Incorporating both inductive (Boyatzis, 1998) and deductive (Crabtree and Miller, 1992) approaches allowed us to better explore the overarching research question: How are existing SEL programs addressing issues of equity and what are areas of strength and opportunities for growth?

We began first by mapping the existing coding system of SEL skills onto relevant literature from the fields of culturally responsive pedagogy, anti-bias and multicultural education, liberatory education, and social justice education. Documents included frameworks such as the Social Justice Standards (Learning for Justice, 2017), the Five Pillars of Emancipatory Practice (El-Amin, 2015), the Six Elements of Social Justice (Picower, 2012), the Revised Radical Healing Framework (Ginwright, 2016), and the Principles of Teaching for Social Justice (Dover, 2009), as well as books about equity-related practice including What if All the Kids Are White? (Derman-Sparks et al., 2006)? and Everyday Antiracism (Pollock, 2008). Guidance documents which provided recommendations for social emotional learning through an equity lens were also reviewed, including the National Equity Project’s Pitfalls and Recommendations (National Equity Project, 2018) and CASEL’s Equity Elaborations (Jagers et al., 2018) among others (Watts et al., 2011; Gay, 2013). Through this mapping exercise, we were able to identify areas of alignment between the widely-recognized SEL skills domains found in the existing SEL coding system (e.g., Cognitive, Emotion, Social, Values, Perspectives, or Identity) and equity-oriented standards and domains highlighted in the literature (e.g., Identity, Diversity, Justice, Agency, and Culture). After identifying the equity-oriented skills and practices that spanned both the SEL coding system domains and the equity-oriented standards and domains from the literature review, 10 equity codes were developed. Two additional codes (Storytelling and Family/Community Representation) were then added based on equity-oriented educational skills and practices that were found in the literature and in SEL lessons, but not in the SEL skills coding system. Each equity code included an initial set of indicators and examples derived from the literature and our own knowledge of SEL programming. These were further updated and refined throughout the coding process based on coding team discussions and what was found in the lessons.

The equity coding system was initially piloted by two different coders and consequently revised before being introduced to the rest of the coding team. The final equity coding system was applied by six coders across 33 PreK-5 SEL programs over the course of seven months. During this time, the coding team met on a weekly basis to discuss how programs were addressing issues of equity within SEL lessons and, more specifically, how the equity codes were appearing in program lessons. Based on these conversations, examples of each code were continuously added to the coding system and indicators were refined and updated throughout to more accurately reflect what appeared in program lessons.

Program Sample

PreK-5 SEL programs were originally identified via several databases and reports (e.g., 2013 CASEL Guide, Blueprints for Healthy Youth Development, Child Trends What Works) or internal expertise, and 33 were ultimately selected for inclusion based on their relevance to the project, diversity of focus and approach, evidence of effectiveness, and accessibility and codability of program materials. Each program selected met a majority of the following inclusion criteria: 1) includes lessons and activities that fall within the PreK-5 age span; 2) has sufficient evidence to indicate impact on social and emotional skills, behavior, academic achievement, attendance, and/or relationships and climate, including results from randomized control trials and/or multiple research studies; 3) is a universal program that could be used in classrooms, afterschool programs, community centers, early childhood centers, and other educational settings; 4) has a primary focus on SEL or a related field (e.g., bullying, youth development, character education, mental health, etc.); 5) is well-aligned with the theory and practice of social and emotional learning, including a well-defined set of activities that directly build student SEL skills; and 6) has accessible and codable materials (e.g., lessons, strategies, and routines that directly build student SEL skills) and implementation information.

Data Collection and Analysis

A team of coders conducted a careful and detailed reading and coding of each program’s curriculum to capture the extent to which lessons incorporated equitable skills and practices. We used quantitative methods to analyze the lesson level data, looking at the percentage of lessons (both within each program and across all programs) that received each code to explore the following question: On average, which equity codes appear most and least commonly across program lessons?

Information was also collected at the program level about the types of programmatic support for equitable and inclusive education offered outside of lessons (e.g., in trainings, implementation manuals, resources libraries, etc.), including 1) guidance, tips, and resources for ensuring program materials and content are relevant to students of all backgrounds, cultures, and educational needs; 2) resources that explicitly and intentionally support adults and students to create inclusive learning environments and challenge systemic oppression; and 3) activities, events, and recommendations for incorporating families in students’ SEL development. We also summarize these findings below.

Content Analysis Findings

Program Level: What Resources are Programs Providing to Support Equity?

As the field of SEL focuses more of its attention on issues of equity, SEL programs are beginning to provide more resources to those looking for additional support on the topics of equity, inclusion, and cultural responsiveness. Our program level analysis found that many programs provide some form of guidance, tips, or resources for ensuring program materials and content are relevant to students of all backgrounds, cultures, and educational needs.

For example, some programs encourage teachers to examine the equity of their seating arrangements, provide them with sample language to use when reinforcing student behavior, provide guidelines for creating or adapting visual supports that will help all students access knowledge, and suggest ways to apply the concepts covered in lessons to real conflicts in the classroom. While less common, some programs also provide resources that explicitly and intentionally support adults’ ability to reflect on their identity and teaching practice in ways that foster inclusive learning environments and challenge systemic oppression. For example, programs may offer teachers an opportunity to reflect on their identities and that of their students, and consider how their personal biases and preconceptions can affect interactions with their students. Other programs provide less targeted resources including supplementary materials with information about anti-bias education, cultural dominance, guidance around how to adapt lessons to incorporate diversity and reflect the students in their class, and other general guidance that ensures lesson materials and content are culturally sustaining. Several programs also promote cultural diversity on a more basic level by using names and stories that are representative of a range of different backgrounds and cultures and images which include people of varying skin colors, ages, and sizes, as well as individuals with disabilities.

In terms of family engagement, some programs offer resources for incorporating families into SEL committees, provide resources for gathering data about parent perceptions of programs, invite families so share their experiences with the class, or share resources to help parents discuss SEL skills and experiences with their children at home (e.g., how they regulate their emotions).

Lesson Level: How Do Social Emotional Learning Lessons and Activities Address Equity?

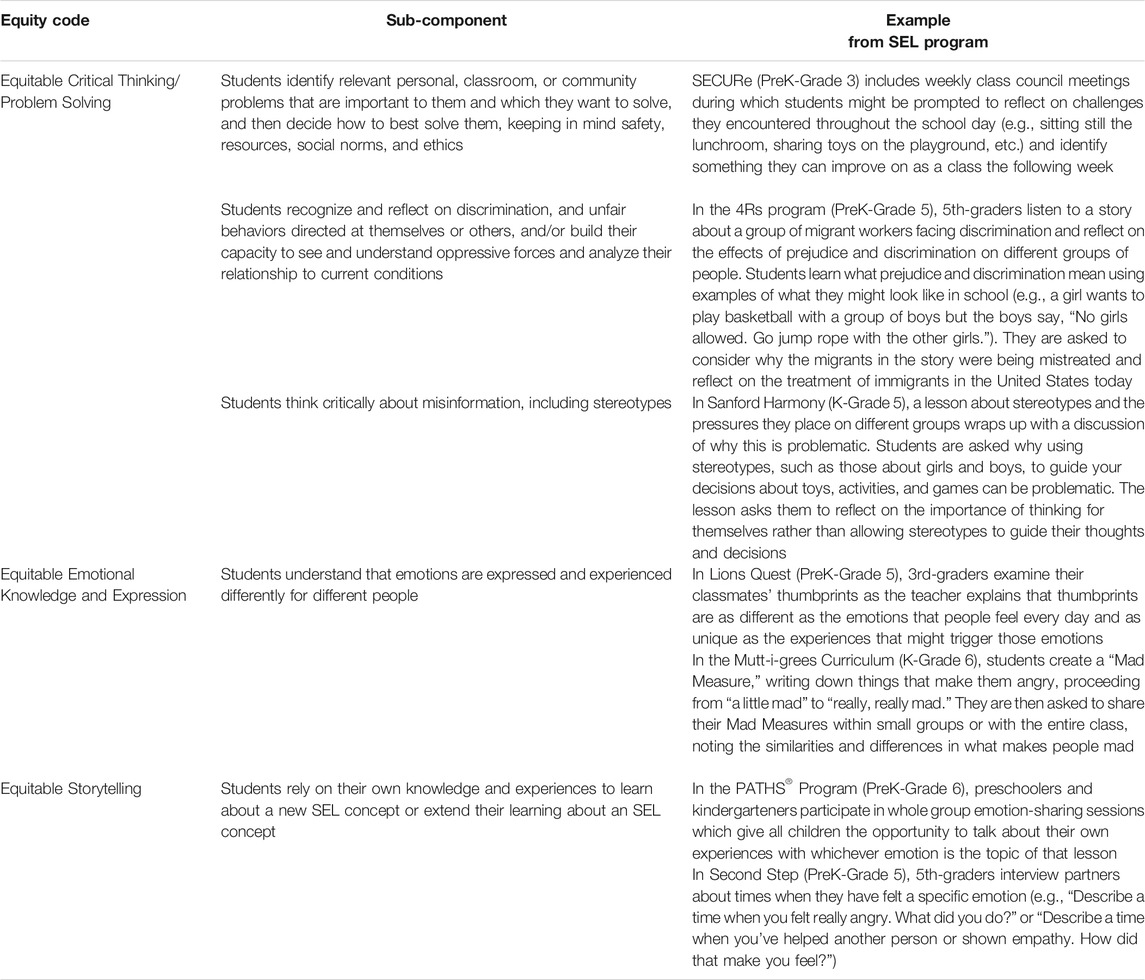

Overall, our findings suggest that equitable SEL practices and skills rarely appear in program lessons and activities. Less than 4% of the lessons in our sample of 33 programs received an equity code. Within that 4% of lessons, we found that programs incorporated three equitable skills and practices more frequently than others: equitable critical thinking/problem solving, equitable emotional knowledge and expression, and equitable storytelling. While the overall low prevalence of equity codes suggests that more intensive efforts are needed to integrate equity into SEL programs, the above areas where SEL and equity tend to overlap may serve as a natural starting place to begin integrating equity into SEL lessons. Below we spotlight some common ways these areas appear in the programs we coded. Please see Table 2 for specific examples from programs.

Equitable Critical Thinking/Problem Solving

Equitable critical thinking/problem solving appears relatively frequently in three programs (i.e., in 13–44% of lessons in the three programs). While this is a small portion of the overall sample, most other equity categories appear in less than 2% of lessons across the entire sample, suggesting that we may have something to learn from how these three programs are targeting and building equitable critical thinking/problem solving. When students build their equitable critical thinking and problem-solving capacities, they use critical thinking skills and tools to 1) identify discrimination and resist prejudice, 2) think critically about misinformation and stereotypes, 3) build their capacity to understand and analyze their relationship to oppressive forces in the world, and/or 4) identify local or other personally-relevant challenges (e.g., in the classroom, community, at home, etc.) and make decisions about how to best solve them.

In the three programs where this type of skill building most often takes place, regular class meetings may include a problem-solving or goal-setting component. During these gatherings, students have an opportunity to build equitable critical thinking/problem solving skills by setting a classroom goal or solving a classroom problem together that touches upon issues of fairness, justice, or related concerns about which they feel passionate. As students raise questions and concerns within the context of their classroom community, teachers may have them engage in planning, problem solving, and goal setting by following a number of steps in which they: 1) identify a class-wide problem area, 2) brainstorm possible solutions together, 3) collectively decide on a plan they will put into action or a goal they want to reach and, 4) track their progress moving forward. These types of activities have the potential to be transformative for children and youth because they allow students to identify and take action on issues that affect them and their communities directly, while the teacher’s role remains that of a facilitator rather than instructor.

In other instances, skill building may take place after reading a story in which a character faces prejudice, injustice, or mistreatment. Using the story as an opportunity to reflect on issues related to discrimination and stereotypes, teachers can: 1) explain that discrimination happens when we treat others unfairly based on prejudice and ask students for examples of this happening in the story, 2) encourage students to think of examples from their own lives of people doing mean or unfair things to other people who are different, 3) ask the class to reflect on the negative effects discrimination can have on people, and 4) have students pair up to brainstorm ideas of actions they can take to stop mistreatment and injustice when they see it happening. Starting with a definition of these terms and providing relevant examples before connecting back to the characters in the story helps students to think about fairness and justice at individual level and begins to build their capacity to see and understand systemic or more widespread injustice.

While less common, some lessons may explicitly target this skill by facilitating exercises that illustrate the problems associated with stereotyped thinking. In activities or games that help students find commonalities with each other, students can be asked to think about the assumptions they made based on group identities (such as gender, race), and how this may prevent them from identifying their shared interests and learning from each other’s differences. Asking questions like “What surprised you? Did you find things in common with people whom you did not expect to have things in common? Why did you have these expectations?” after the activity can help students reflect on their own biases and assumptions. These types of activities have the potential to be transformative because they help students deconstruct stereotypes about themselves and their peers and move them from “celebrating diversity” to an exploration of how diversity has differently impacted various groups of people, ultimately helping them recognize their responsibility to stand up to exclusion, prejudice, and injustice (Picower, 2012; Learning for Justice, 2017).

Equitable Emotional Knowledge and Expression

Equitable emotional knowledge and expression appears most commonly across the set of programs, showing up at least once in 20 of the 33 programs coded. When students build their equitable emotional knowledge and expression capacities, they 1) recognize that all feelings are okay, 2) understand that emotions are expressed and experienced differently by everyone, and/or 3) use a variety of words or gestures for expressing feelings that reflect the language or vocabulary they use at home and in their community. This skill building typically occurs when a program is introducing emotions or during a lesson discussing emotion regulation or emotional triggers. During these kinds of activities, teachers can affirm that all feelings are valid or acceptable and that people have different levels of comfort with different emotions. For example, after an emotion is introduced, teachers can take the opportunity to remind students that: 1) in some ways we are alike and in some ways we are different, 2) we can have many different feelings about the same situation and express those feelings differently from one another, and 3) some feelings are comfortable and enjoyable to have, while other feelings are uncomfortable or difficult to have, but all feelings are okay. In some programs, teachers can expand further on this idea by having students also share what elicits a specific emotion in them, such as anger, then reflect on the differences and similarities in what makes people feel angry. These activities have the potential to be transformative because they help students deconstruct expectations and cultural norms around ways of expressing emotion and expand the definition of normative and appropriate reactions to include the experiences and cultures of all students (National Equity Project, 2018).

Equitable Storytelling

Equitable storytelling appears relatively frequently in three programs (i.e., in 18–31% of lessons) and at least once across most programs (i.e., 20 of the 33 programs). Lessons that include equitable storytelling practices encourage students to share their experiences and stories, and often explicitly and intentionally center student knowledge and make use of personal narrative in lessons. Activities that integrate storytelling practice, consider student experience foundational to building knowledge and teaching SEL concepts. While not all students are required to participate, equitable storytelling practices allow all students the opportunity to share their experiences or be an active listener to others who are sharing. Across the three programs, this practice often takes place when a new concept, like an emotion, is being introduced to students. Indeed, in several of the programs, one of the most important aspects related to teaching children about emotions involves helping children connect what they already know and have experienced in terms of feelings with the emotions they will be learning about.

Teachers can help students build equitable storytelling skills when an unfamiliar or new concept is being taught by 1) introducing the concept briefly, sharing little besides the name and some context if necessary; 2) asking students if they have heard of the concept before and can think of a story from their own lives that connects with or reminds them of the concept; 3) having students take a minute to think and then share their stories, thoughts, and experiences with a partner; and 4) having volunteers share out with the whole class and, if appropriate, writing the main ideas from the share out on the board before providing additional information about the concept. When introducing an unfamiliar emotion to younger students, teachers can also have them participate in sharing circles which provide all children the opportunity to share about their own experiences with the emotion. If teachers feel equipped to facilitate a more extended discussion and have previously established a safe space for students to share in the classroom, it can also be helpful for students to first share stories with the class about times they felt an uncomfortable emotion before learning about emotion regulation techniques associated with that emotion as this allows students to more easily connect the techniques they are learning with their individual circumstances. Although much less common in SEL lessons, open-ended activities that encourage students to share their experiences more generally such as sharing or healing circles, where members share their interests, fears, and hopes can be especially impactful (Ginwright, 2016). Equitable storytelling is transformative because it shows students that their experiences are valuable and worth sharing and creates a climate of respect for diversity as students learn to listen with kindness and empathy to the experiences of their peers (Picower, 2012; National Equity Project, 2018).

What is Missing?

Lessons and activities that incorporate equitable emotional and behavioral regulation, equitable self-knowledge, and equitable self-efficacy/growth mindset appeared least commonly across programs. Less than 1% of lessons (i.e., between 0.1 and 0.51% of lessons) across all programs touched upon these three categories. Overall, 29 of the 33 programs did not have any lessons that incorporated equitable self-efficacy/growth mindset or equitable emotional and behavioral regulation, and 25 of 33 programs did not have lessons that incorporated equitable self-knowledge. This may be in part because identity development and related constructs (such as self-knowledge and learner identity which relate closely to self-efficacy and growth-mindset) are often considered most important in adolescence (Tsang et al., 2012; Nagaoka et al., 2015) rather than during the preschool and elementary years. Nevertheless, this gap is significant to note and address in future work.

Although identity development plays a critical role in adolescence, the constructs of identity begin developing from birth and are molded during early and middle childhood as children learn about themselves in relation to opportunities and limitations in their social world (Derman-Sparks et al., 2006; Raburu, 2015; Reschke, 2019). In order for positive identity development to happen during adolescence, children need early experiences that promote healthy self-awareness and a sense of belonging and self-worth in childhood, including the formation of positive identity and self-efficacy, SEL skill areas which are not always focused on in elementary classrooms. Additional efforts are needed to include lessons that focus on building equitable self-knowledge and equitable self-efficacy/growth mindset capacities in pre-school and elementary school SEL programming because these skills help students explore their identity and positionality, and cultivate mindsets, beliefs, and practices that help students develop positive academic identities.

It is particularly troubling that few programs touched upon equitable emotional and behavioral regulation, which teaches regulation in a way that empowers students by connecting the purpose of self-regulation to students’ own self-interest and helps students explore different expectations for self-regulation based on identity, context, and setting. The low prevalence of equity-oriented emotional and behavioral regulation in SEL programs is particularly problematic because SEL programs often place a large focus on self-regulation, self-management, and related SEL concepts which are often misapplied and can further inequities. Research shows that the misbehavior of low-income students and students of color is often perceived as an inability to self-regulate and is responded to with punishment or demands for compliance (Green, 2018; Bailey et al., 2019). Framing emotional and behavioral skills as a way to practice self-care and self-preservation can be transformative for students because it moves self-management away from compliance and conformity to empowerment while at the same time allowing students to build the crucial navigational skills they need to manage behavior and express emotions in an unjust world (El-Amin, 2015; Simmons, 2019). Children need opportunities to regulate their feelings and behaviors and to understand self-regulation and self-management techniques as tools that they can use to their benefit in and out of school.

Content Analysis Limitations

Sampling Bias

The sample of programs used for coding purposes was limited to accessible, United States-based, English language SEL programs that include some direct form of student skill-building, typically via a scope and sequenced curriculum and/or through a set of activities, and routines designed to be integrated throughout the regular day. Although these programs typically fall under the category of comprehensive prevention and intervention programs that are one of the most widely used approaches and consequently have been the most rigorously studied (Jones et al., 2017a), it is important to note that there are many other valid and valuable types of SEL interventions that could not be coded using our coding system including interventions that 1) target adult skills, attitudes, and practices in ways that support high-quality teaching, learning, and social and emotional development, as well as those that seek to 2) transform the entire culture and climate of the learning environment via a system-wide approach that integrates norms and expectations.

Transferability

While the programs analyzed are considered universal programs, it is important to acknowledge that the programs were developed in the United States and are most widely-used and studied in United States contexts. Furthermore, the frameworks and other documents reviewed as part of the development of the equity coding system were largely written by United States-based scholars. For this reason it is not possible to conclude whether the equity coding system is applicable or relevant to settings outside of the United States. Future research could expand upon the current research and explore the applicability and transferability of the equity coding system to non-United States based SEL programs.

Discussion

The equity coding system we developed captures a variety of skills and practices that empower students to 1) think critically and strategically about their circumstances and the world in which they live; 2) develop their ethnic, racial, and social identities; and 3) build their self-efficacy and agency. These skills and practices align with the comprehensive principles and proposed definition of equitable SEL described earlier in this paper: an approach to SEL that incorporates the cultural knowledge, experiences, and assets of students from diverse families and communities, and acknowledges and addresses the social injustices, inequalities, prejudices, and exclusions that students face. Findings from our content analysis are consistent with the claim that SEL programs, while promising vehicles for promoting equity because of the alignment between many of their principles, are not inherently equitable. As indicated above, very few PreK-5 SEL programs have a curricular focus on issues related to equity, justice, cultural competence, or cultural diversity and only a handful of the programs we analyzed seem to intentionally design their content to be equitable. Given that SEL programs are often described as mechanisms to improve educational outcomes and wellbeing for all children, particularly those in marginalized communities, this is an important finding and area for growth within the field. While some programs analyzed did provide guidance for educators to tailor the way they frame and deliver lessons, currently the responsibility falls on individual educators, facilitators, and trainers to make equitable SEL more intentional in the classroom. Indeed, the promise of SEL as a lever for increasing educational equity largely depends on whether educators have the tools needed to increase their own critical self-awareness; understand how racism and historic oppression are embedded in the context of our schools; and design or adapt SEL lessons that engage and value all students for the experiences they bring into the classroom (National Equity Project, 2018). Until SEL curricula is intentionally designed and written with equity in mind, schools, educational settings, and educators themselves carry the responsibility to interpret, frame, and deliver lessons to students in a manner that takes into consideration their cultural knowledge, experiences, and assets, and acknowledges and addresses the social injustices, inequalities, prejudices, and exclusions they face. The equity-oriented principles, skills, and practices highlighted in our equity coding system and outlined in our proposed definition of equitable SEL are a starting point for educators, schools, and other educational settings to familiarize themselves with equity-oriented SEL skill building at the classroom-level. Given that schools and other educational settings have limited control over what appears in SEL lesson content and similarly limited resources available for adapting lessons to diverse contexts, we offer the following recommendations that, when addressed purposefully, can be important levers for helping educators to approach SEL in a way that is consistent with the general principles of equitable SEL.

Recommendation 1: Invest in Adult Training

Invest in adult self-awareness, knowledge, and skills by providing training and resources that encourage adults to build their own SEL skills, examine and address implicit biases, and engage in culturally sustaining and equity-promoting practices. Strategies include critical reflective prompts and statements (McIntosh, 1990; Weigl, 2009; Simmons, 2017), loving kindness meditation and mindfulness training (Kang et al., 2014; Lueke and Gibson, 2015; Suttie, 2017); and anti-bias and culturally sustaining SEL training (Brion-Meisels et al., 2019; Poddar et al., 2021).

Recommendation 2: Reflect Student Identities

Design and/or select SEL curricula that reflect and build upon student identities, cultures, and goals. To truly serve all students, SEL should ensure that messaging, skills, and goals reflect, incorporate, and sustain diverse student needs and perspectives and move away from curricula that reinforces white, Western, individualist culture without acknowledging and accepting other ways of being. Focus on skills that align with student needs and interests, provide opportunities for students to incorporate their own experiences and personal narratives into the curriculum, and promote transformational goals for youth that enable them to recognize and work against social injustice (Simmons, 2017; Jagers et al., 2018; National Equity Project, 2018).

Recommendation 3: Involve Students and Families

Be inclusive and intentional when selecting SEL programming by involving students, families, and staff. Students, families, and communities should be active participants in building SEL programs to ensure they reflect the values, beliefs, identities, interests, and needs that are important to them, ultimately increasing buy-in and impact. This might include soliciting student and family feedback via surveys, phone calls, and other strategies that establish ongoing feedback loops (Drwal, 2014; Simmons, 2017) or using asset-mapping strategies to identify and align community assets (e.g., cultural facilities and organizations, festivals and events, and artists networks) with student educational needs (Simmons, 2017).

Recommendation 4: Align Social Emotional Learning With Equitable School Practices

Accompany and align SEL programming with other mutually reinforcing equitable school practices and structures such as restorative disciplinary practices and trauma-sensitive systems. This includes restorative justice practices that emphasize repairing the harm done to individuals and the community through cooperative processes that focus on joint problem-solving and restitution, resolution, and reconciliation among the parties involved (Morrison and Vaandering, 2012; Simmons et al., 2018) and trauma-informed practices that acknowledge and address persistent environmental stressors such as racism, transphobia, homophobia, and classism that impact the social and emotional wellbeing of marginalized youth.

Conclusion

In closing, we hope the proposed definition for equitable SEL and the equity coding system are useful tools for researchers, practitioners, and program developers who seek to understand and more directly integrate issues of race, identity, and equity with traditional SEL programming in schools. By applying the equity coding system to PreK and Elementary SEL programs that are widely-used in the United States, we explored the extent to which current programs address issues of racial justice, identity, power, privilege, bias, and oppression. The results of our coding suggest that overall, very few programs explicitly discuss these issues in lessons or curricula. We found that three equitable practices were most common among the programs we coded: equitable critical thinking/problem solving, equitable emotional knowledge and expression, and equitable storytelling. These practices may be useful starting places for SEL programs that aim to include more equity-oriented practices. We note that our research is shaped largely by United States-based theory, programming, and educational practice. Future research should explore the applicability of our proposed definition for equitable SEL and the equity coding system to other contexts and non-United States based SEL programs.

Author Contributions

TR conducted research and wrote the first draft of the manuscript; KB contributed to the conceptualization and design of the paper and wrote sections of the manuscript; NR conducted research and wrote sections of the manuscript; SMJ and RB contributed to the conception and design of the paper; and all authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The content analysis, equity coding system, research, and writing upon which this chapter is based were made possible through funding from the Wallace Foundation, as part of the development of the Navigating SEL from the Inside Out report.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

This paper is derived from Chapter 3: Integrating Trauma, Equity, and SEL in the second edition of Navigating SEL from the Inside Out (Jones et al., 2021), a content analysis of and guide to 33 widely-used SEL programs for preschool through 5th grade commissioned by the Wallace Foundation. We are extremely grateful to the Wallace Foundation, in particular Amy Gedal Douglass, Katherine Lewandowski, and Bronwyn Bevan for their generous support and ongoing collaboration and feedback. A team of researchers at the Harvard Graduate School of Education (HGSE) contributed to this publication including: Jorge Cuartas who helped with the analysis of the equity codes; Emily Meland and Gretchen Brion-Meisels who provided insight and support throughout the various phases of the writing process; Zoe Xinyi Mao, Michele Marenus, Samantha Wettje, and Kristen Finney, our core team of coders who contributed to the lesson coding, data collection, and revision and expansion of the equity coding system. A special thanks to our group of reviewers who provided thoughtful feedback on early drafts of this work: Gretchen Brion-Meisels of the Harvard Graduate School of Education, Kamilah Drummond-Forrester of Open Circle, Drema Brown of Children’s Aid, and David Osher of American Institutes for Research. Finally, we would like to thank the developers who created the programs coded for the content analysis for their willingness to provide us with access to their program materials and information, for their helpful conversations and reviews, and for their dedication to helping children and youth build the social and emotional skills central to success in school and life.

References

Bailey, R., Meland, E. A., Brion-Meisels, G., and Jones, S. M. (2019). Getting Developmental Science Back into Schools: Can what We Know about Self-Regulation Help Change How We Think about “No Excuses”? Front. Psychol. 10. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01885

Banks, J. A. (2004). Teaching for Social Justice, Diversity, and Citizenship in a Global World. Educ. Forum 68 (4), 296–305. doi:10.1080/00131720408984645

Bierman, K. L., Domitrovich, C. E., Nix, R. L., Gest, S. D., Welsh, J. A., Greenberg, M. T., et al. (2008). Promoting Academic and Social-Emotional School Readiness: The Head Start REDI Program. Child. Dev. 79 (6), 1802–1817. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01227.x

Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Sage.

Braveman, P., and Gottlieb, L. (2014). The Social Determinants of Health: It's Time to Consider the Causes of the Causes. Public Health Rep. 129, 19–31. doi:10.1177/00333549141291s206

Brion-Meisels, G., Meland, E., Bailey, R., and Jones, S. (2019). Toward a Model of Culturally-Sustaining SEL, (Working Paper), Cambridge, MA: Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Brown, J. L., Jones, S. M., LaRusso, M. D., and Aber, J. L. (2010). Improving Classroom Quality: Teacher Influences and Experimental Impacts of the 4Rs Program. J. Educ. Psychol. 102 (1), 153–167. doi:10.1037/a0018160

Caldarella, P., Christensen, L., Kramer, T. J., and Kronmiller, K. (2009). Promoting Social and Emotional Learning in Second Grade Students: A Study of the Strong Start Curriculum. Early Child. Educ J 37 (1), 51–56. doi:10.1007/s10643-009-0321-4

Cammarota, J., and Romero, A. (2011). Participatory Action Research for High School Students: Transforming Policy, Practice, and the Personal with Social Justice Education. Educ. Pol. 25 (3), 488–506. doi:10.1177/0895904810361722

Cantor, P., Osher, D., Berg, J., Steyer, L., and Rose, T. (2019). Malleability, Plasticity, and Individuality: How Children Learn and Develop in Context1. Appl. Dev. Sci. 23 (4), 307–337. doi:10.1080/10888691.2017.1398649

Castro-Olivo, S. M. (2014). Promoting Social-Emotional Learning in Adolescent Latino ELLs: A Study of the Culturally Adapted Strong Teens Program. Sch. Psychol. Q. 29 (4), 567–577. doi:10.1037/spq0000055

Center on the Developing Child, (2018). A Guide to Toxic Stress: ACEs and Toxic Stress: Frequently Asked Questions. Availableat: https://developingchild.harvard.edu/guide/a-guide-to-toxic-stress/.

Crabtree, B. F., and Miller, W. L. (1992). A template approach to text analysis: Developing and using codebooks. In B. F. Crabtree, and W. L. Miller (Eds.), Doing Qualitative Research (pp. 93–109). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Craig, S. E. (2008). Reaching and Teaching Children Who Hurt: Strategies for Your Classroom. Baltimore, Maryland: Paul H. Brooks Publishing Co.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher Education Around the World: What Can We Learn from International Practice? Eur. J. Teach. Edu. 40 (3), 291–309. doi:10.1080/02619768.2017.1315399

de Brey, C., Musu, L., McFarland, J., Wilkinson-Flicker, S., Diliberti, M., Zhang, A., et al. (2019). Status and Trends in the Education of Racial and Ethnic Groups 2018 (NCES 2019-038). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education. doi:10.4000/ccec.8237

Derman-Sparks, L., Ramsey, P., and Edwards, J. (2006). What if All the Kids Are white? Anti-bias Multicultural Education with Young Children and Families (Early Childhood Education Series). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Desai, P., Karahalios, V., Persaud, S., and Reker, K. (2014). A Social justice Perspective on Social Emotional Learning. Communique. NASP 43 (1), 14–16.

Diamond, A., Barnett, W. S., Thomas, J., and Munro, S. (2007). THE EARLY YEARS: Preschool Program Improves Cognitive Control. Science 318 (5855), 1387–1388. doi:10.1126/science.1151148

Dover, A. G. (2009). Teaching for Social Justice and K-12 Student Outcomes: A Conceptual Framework and Research Review. Equity Excell. Edu. 42 (4), 506–524. doi:10.1080/10665680903196339

D. Paris, and H. S. Alim (2017). in Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies: Teaching and Learning for justice in a Changing World (New York, NY: Teachers College Press),

Drwal, J. (2014). Improving the Feedback LoopTeaching Tolerance Magazine. Availableat: https://www.tolerance.org/magazine/improving-the-feedback-loop.

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., and Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The Impact of Enhancing Students' Social and Emotional Learning: A Meta-Analysis of School-Based Universal Interventions. Child. Dev. 82 (1), 405–432. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

El-Amin, A. (2015). “Until Justice Rolls Down like Water” Revisiting Emancipatory Schooling for African Americans- A Theoretical Exploration of Concepts for Liberation. Cambridge , MA , USA: Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Fereday, J., and Muir-Cochrane, E. (2006). Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: a Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development. Int. J. Qual. Methods 5 (1), 80–92. doi:10.1177/160940690600500107

Gay, G. (2010). Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice. New York, NW, USA: Teachers College Press.

Gay, G. (2013). Teaching to and through Cultural Diversity. Curriculum Inq. 43 (1), 48–70. doi:10.1111/curi.12002

Gerrity, E., and Folcarelli, C. (2008). Child Traumatic Stress: What Every Policymaker Should Know. Durham, NC and Los Angeles, CA: National Center for Child Traumatic Stress.

Ginwright, S., and Cammarota, J. (2002). New Terrain in Youth Development: The Promise of a Social justice Approach. Social Justice 29 (4), 82–95.

Ginwright, S. (2016). Hope and Healing in Urban Education: How Urban Activists and Teachers Are Reclaiming Matters of the Heart. Oxford, UK: Routledge.

Green, E. L. (2018). Why Are Black Students Punished So Often? Minnesota Confronts a National Quandary. The New York Times. doi:10.5749/j.ctv9b2tmdAvailableat: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/18/us/politics/school-discipline-disparities-white-black-students.html

Gregory, A., and Fergus, E. (2017). Social and Emotional Learning and Equity in School Discipline. Future Child. 27 (1), 117–136. doi:10.1353/foc.2017.0006

Gutstein, E. (2003). Teaching and Learning Mathematics for Social Justice in an Urban, Latino School. J. Res. Math. Edu. 34 (1), 37–73. doi:10.2307/30034699

Hammond, Z., and Jackson, Y. (2015). Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain: Promoting Authentic Engagement and Rigor Among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: Corwin.

Hebert, L., Peterson, K., and Dunsmore, K. (2019). A Leader’s Guide to Trauma-Sensitive Schools and Whole-Child Literacy: School, home, and Community Working Together for All childrenLiteracy Organizational Capacity Initiative (LOCI). Norc at the University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA.

Immordino-Yang, M. H., Darling-Hammond, L., and Krone, C. (2018). The Brain Basis for Integrated Social, Emotional and Academic Development: How Emotions and Social Relationships Drive Learning. Washington, D.C, USA: Aspen Institute National Commission on Social, Emotional, & Academic Development.

Jagers, R. J. (2016). Framing Social and Emotional Learning Among African-American Youth: Toward an Integrity-Based Approach. Hum. Dev. 59, 1–3. doi:10.1159/000447005

Jagers, R. J., Rivas-Drake, D., and Borowski, T. (2018). Equity and Social-Emotional Learning: A Cultural Analysis. CASEL Assessment Work Group Brief Series. doi:10.1037/t67831-000Availableat: https://measuringsel.casel.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Frameworks-Equity.pdf

Jagers, R. J., Rivas-Drake, D., and Williams, B. (2019). Transformative Social and Emotional Learning (SEL): Toward SEL in Service of Educational Equity and Excellence. Educ. Psychol. 54 (3), 162–184. doi:10.1080/00461520.2019.1623032

Jones, S. M., Barnes, S. P., Bailey, R., and Doolittle, E. J. (2017a). Promoting Social and Emotional Competencies in Elementary School. Future Child. 27 (1), 49–72. doi:10.1353/foc.2017.0003

Jones, S. M., Brown, J. L., and Lawrence Aber, J. (2011). Two-year Impacts of a Universal School-Based Social-Emotional and Literacy Intervention: An experiment in Translational Developmental Research. Child. Dev. 82 (2), 533–554. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01560.x

Jones, S. M., Brush, K. E., Bailey, R., Brion-Meisels, G., McIntyre, J., Kahn, J., et al. (2017b). Navigating SEL from the inside Out: Looking inside & across 25 Leading SEL Programs: A Practical Resource for Schools and OST Providers (Elementary School Focus). New York, NY, USA: The Wallace Foundation.

Jones, S. M., Brush, K. E., Ramirez, T., Mao, Z. X., Marenus, M., Wettje, , et al. (2021). Navigating SEL from the inside Out: Looking inside & across 33 Leading SEL Programs: A Practical Resource for Schools and OST Providers: Revised and Expanded. second edition. New York, NY, USA: The Wallace Foundation.SBailey(preschool & elementary focus)

Kang, Y., Gray, J. R., and Dovidio, J. F. (2014). The Nondiscriminating Heart: Lovingkindness Meditation Training Decreases Implicit Intergroup Bias. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 143 (3), 1306–1313. doi:10.1037/a0034150

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a Theory of Culturally Relevant Pedagogy. Am. Educ. Res. J. 32 (3), 465–491. doi:10.3102/00028312032003465

Learning for Justice, (2017). Social Justice Standards. Available at: https://www.learningforjustice.org/frameworks/social-justice-standards.

Love, B. (2019). We Want to Do More than Survive: Abolitionist Teaching and the Pursuit of Educational Freedom. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Lueke, A., and Gibson, B. (2015). Mindfulness Meditation Reduces Implicit Age and Race Bias. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 6 (3), 284–291. doi:10.1177/1948550614559651

McIntosh, P. (1990). White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack. New york, NY, USA: Independent School, 31–36.

Morgan, I., and Amerikaner, A. (2018). Funding Gaps 2018. The Education Trust. Available at: https://edtrust.org/resource/funding-gaps-2018/.

Morrison, B. E., and Vaandering, D. (2012). Restorative Justice: Pedagogy, Praxis, and Discipline. J. Sch. Violence 11 (2), 138–155. doi:10.1080/15388220.2011.653322

Nagaoka, J., Farrington, C. A., Ehrlich, S. B., and Heath, R. D. (2015). Chicago Consortium on School Research, University of Chicago.Foundations for Young Adult Success: A Developmental Framework

National Center for Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN), (2017). Addressing Race and Trauma in the Classroom: A Resource for Educators. Available at: https://www.nctsn.org/resources/addressing-race-and-trauma-classroom-resource-educators.

National Education Association (Nea), (2020). NEA Policy Playbook. National Education Association, Washingdon, DC, USA,

National Equity Project, (2020). Educational Equity: A Definition. Available at: https://www.nationalequityproject.org/education-equity-definition.

National Equity Project, (2018). Social Emotional Learning & Equity. Available at: https://www.nationalequityproject.org/frameworks/social-emotional-learning-and-equity.

National School Boards Association (Nsba), (2019). Equity. Available at: https://www.nsba.org/Advocacy/Equity.

Osher, D., Pittman, K., Young, J., Smith, H., Moroney, D., and Irby, M. (2020). Thriving, Robust Equity, and Transformative Learning & Development. American Institutes for Research and Forum for Youth Investment.

Paris, D. (2012). Culturally Sustaining Pedagogy. Educ. Res. 41 (3), 93–97. doi:10.3102/0013189x12441244

Pearman, F. A., Curran, F. C., Fisher, B., and Gardella, J. (2019). Are Achievement Gaps Related to Discipline Gaps? Evidence from National Data. AERA Open 5 (4), 1–18. doi:10.1177/2332858419875440

Picower, B. (2012). Using Their Words: Six Elements of Social Justice Curriculum Design for the Elementary Classroom. Int. J. Multicultural Edu. 14 (1), 1–17. doi:10.18251/ijme.v14i1.484

Poddar, A., Meland, E., Bailey, R., and Jones, S. M. (2021). Addressing Teachers’ Biases: A Review of Anti-bias and Anti-racist Literature.[Poster session]. APA Division 45 Research Conference, Virtual

Pollock, M. (2008). Everyday Antiracism: Getting Real about Race in School. New York, NW, USA: New Press.

Raburu, P. A. (2015). The Self- Who Am I?: Children’s Identity and Development through Early Childhood Education. J. Educ. Soc. Res. 5 (1), 95.

Raver, C. C., Jones, S. M., Li-Grining, C., Zhai, F., Metzger, M. W., and Solomon, B. (2009). Targeting Children's Behavior Problems in Preschool Classrooms: A Cluster-Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Consulting Clin. Psychol. 77 (2), 302–316. doi:10.1037/a0015302

Santiago, C. D., Raviv, T., and Jaycox, L. H. (2018). Creating Healing School Communities: School-Based Interventions for Students Exposed to Trauma. American Psychological Association.Washingdon, DC, USA, doi:10.1037/0000072-000

Simmons, D. (2017). Is Social-Emotional Learning Really Going to Work for Students of Color? Education Week. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199975839.013.1266 Available at: https://www.edweek.org/tm/articles/2017/06/07/we-need-to-redefine-social-emotional-learning-for.htm

Simmons, D. N., Brackett, M. A., and Adler, N. (2018). Applying an Equity Lens to Social, Emotional, and Academic Development. College State, PA: Pennsylvania State University.

Simmons, D. (2019). Why We Can’t Afford Whitewashed Social-Emotional Learning. ASCD Education Update Alexandria, VA: ASCD, 69.

Sklad, M., Diekstra, R., Ritter, M. D., Ben, J., and Gravesteijn, C. (2012). Effectiveness of School-Based Universal Social, Emotional, and Behavioral Programs: Do They Enhance Students' Development in the Area of Skill, Behavior, and Adjustment? Psychol. Schs. 49 (9), 892–909. doi:10.1002/pits.21641

Stearns, Clio. (2019). Critiquing Social and Emotional Learning: Psychodynamic and Cultural Perspectives. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (Samhsa), (2014). SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. Available at: https://ncsacw.samhsa.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf.

Suttie, J. (2017). Three Ways Mindfulness Can Make You Less Biased Greater Good Science Center at UC Berkeley. Available at: https://greatergood.berkeley.edu/article/item/three_ways_mindfulness_can_make_you_less_biased.

The Aspen Education & Society Program and the Council of Chief State School Officers (2017). Leading for Equity: Opportunities for State Education Chiefs. Washington, DC: Council of Chief State School Officers. Available at: https://ccsso.org/sites/default/files/2018-01/Leading%20for%20Equity_011618.pdf.