- 1Department of Anthropology, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan

- 2Department of Social and Cultural Anthropology, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

Enshrined in different conventions nationally and internationally, education is a fundamental right of every child irrespective of identity and location worldwide. Despite the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) 1948 and the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of the Child 1989, education is not accessible and affordable for every child globally due to several entwined factors. Focusing on Pakistan’s Sindh Province, this article identifies the numerous factors that lead to school dropouts and illustrates their interconnectedness. Employing Sen’s Capabilities Approach, we show a relation between freedom and function, whereby a capability can only be a function if there is an opportunity. We conclude and suggest that since the basic right of education is denied in Pakistan owing to sociocultural, economic, and political factors, there is a need to make necessary efforts at the parental as well as national policy level to address it. We also ask for ethnographically rich studies that should comparatively and thoroughly bring this dropout problem to the center stage for generating a comprehensive understanding so that this basic right is given to every child of this country.

Introduction: Education as a Fundamental Right

The right to education has been internationally recognized as one of the fundamental rights for all. Several conventions and treaties on both international and national levels have been signed to safeguard and ensure access to education irrespective of any identity such as race, gender, ethnicity, caste, and class. Among these, the most pervasively ratified include the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR)and the 1989 United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of the Child. Article 26 of the 1948 UDHR states: 1) “Everyone has the right to education. Education shall be free, at least in the elementary and fundamental stages. Elementary education shall be compulsory. Technical and professional education shall be made generally available and higher education shall be equally accessible to all on the basis of merit” (United Nations, 1948). And 2), “Parents have a prior right to choose the kind of education that shall be given to their children.” (ibid.)

Similarly, several UN and the United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF) conventions have emphasized a child’s right to education, starting as early as 1959 with the adoption of the Declaration of the Rights of the Child. This was further consolidated and elaborated in the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child 1989, which is a hallmark in this direction. Article 28 extensively discusses several factors concerning not only the accessibility and availability of education for all, but also for a functional system that leads to better learning (United Nations, 1989). Keeping in view the hierarchy involved in knowledge providers and seekers, it also speaks of the dignity of the latter to remain intact during the learning process. The article endows the state with the responsibility to ensure accessibility and availability of education to all without any discrimination. Important features include: 1) Make primary education compulsory, available, and free to all; 2) Encourage the development of different forms of secondary education, including general and vocational education, make them available and accessible to every child, and take appropriate measures such as the introduction of free education and offering financial assistance in case of need; 3) Make higher education accessible to all based on capacity by every appropriate means; 4) Make educational and vocational information and guidance available and accessible to all children; and 5) Take measures to encourage regular attendance at schools and the reduction of dropout rates.

On the Pakistani level, Article 25a – right to education (2018), is seminal in this regard. Approved by all provincial assemblies, the article is still pending legislation only in Gilgit-Baltistan and Azad Jammu Kashmir. It states: “The State shall provide free and compulsory education to all children of the age of five to 16 years in such [a] manner as may be determined by law.” Corollary to this is Article 37-b emphasizing the removal of illiteracy and [a] provision of “free and compulsory secondary education within [a] a minimum possible period.”

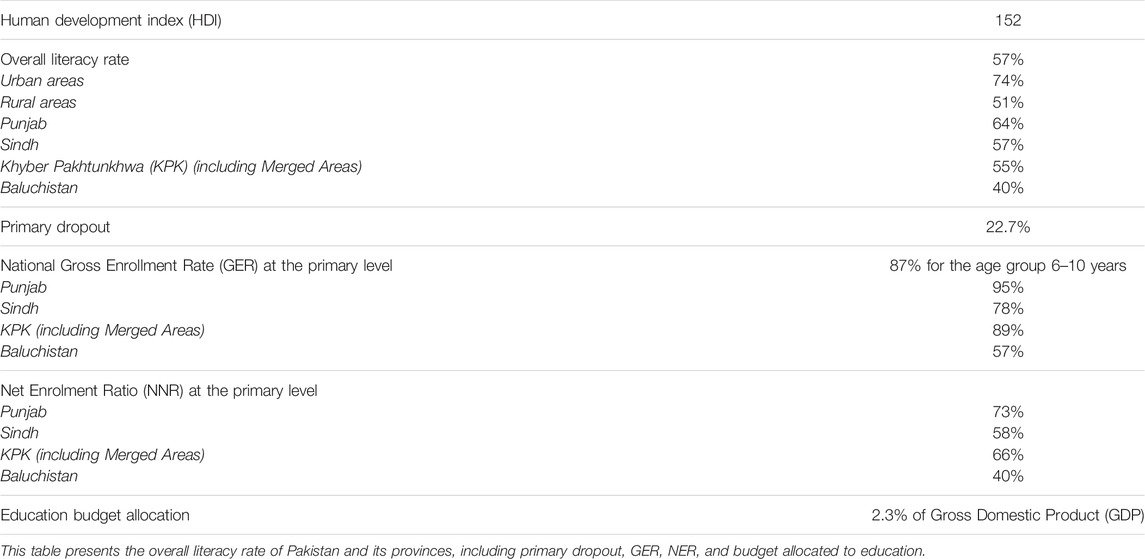

Despite the emphasis, the conventions and legislation statistics indicate the state’s failure to fulfill the responsibility endowed to it. The overall literacy rate in Pakistan is 57%, primary dropout 22.7%, and education budget allocation is approximately 2.3% of GDP (Government of Pakistan, 2020). This figure explicitly reveals that education is low on the government’s priority list. Yet, the onus of this negligence does not solely fall on the state as several factors contribute to it—various forms of institutionalized disparities such as economic, political, and social stand out as the most prominent.

No anthropological work on this subject has been conducted in Pakistan; thus this article seeks to identify these factors and examine their interconnectedness. Paying close attention to the problem under study, cultural capital containing various socio-economic statuses plays a substantial role in discouraging certain children not to reproduce their privileged position in society (see Bourdieu and Passeron, 1977). Hence, focusing on the underlying reasons, this study was conducted in a Muhalla (ward) of Nasirabad town of Sindh Province of Pakistan. It provides a comprehensive and in-depth understanding of the problems around dropouts around dropout: what elements encourage children to leave school prematurely? We argue that the causes of dropouts can only be understood against the backdrop of several sociocultural, political, and economic factors that significantly affect education in the stated province. Providing an overview of education in Pakistan, and starting with people’s general perceptions towards education, the article then discusses the various significant factors leading to children dropping out of school.

Methods and Materials

This study’s locale was Noonari Muhalla (ward) of Nasirabad located in district Kambar-Shahdadkot, Sindh province of Pakistan. Sindh is located in the southeast of the country, where a majority of people of Sindhi ethnicity are settled. The lingua Franca is the Sindhi language with a few “other “prominent languages such as Serāikī (it is sometimes considered as a dialect of Sindhī), Urdu, and Balochī. In terms of geographical area, Sindh is the third largest province, and population-wise, it is the second-largest province of Pakistan. The province has around 50 million population with a majority of Muslims and a minority of Hindus—most people are settled in rural areas than urban ones1 Education, in terms of its quality and quantity, has remained a great concern and problem in the province as almost half of the population is unable to read and write. And these facts significantly differ when compared gender-wise or geographical-area-wise as the male population is more educated—in terms of numbers—than the female population. Similarly, urban areas have a more educated population than rural areas.

Our reasons for choosing this locale included its significant number of educational institutions and a rising number of dropouts. There were around 170 educational institutes in the Taluka (sub-district), Nasirabad: 40 boys’ schools and 40 girls’ schools, and 97 co-education schools (where both girls and boys receive education). A total of 22,000 students were enrolled in government schools: 13,000 boys and 9,050 girls. Across the country, the education rate differs significantly gender-wise, as many more men have formal education than women. (Source: field data).

Our analysis is based on data collected through field research by Murad Ali, over a period of 4 months using primarily in-depth interviews and focus group discussions during 2017. Being a native speaker of the Sindhi language and belonging to that area, he needed less time to build the required rapport. Capitalizing on these advantages, Murad conducted several group discussions in the Sindhi language.

Using a purposive sampling and an interview guide, several group discussions of 2–3 h each with 30 men at their Otāq (guest house for male members), teachers, and several children. Additionally, in-depth interviews were also conducted for a better understanding of the dropout phenomenon: its causes and consequences. In the case of children, permission was duly sought by the guardian prior to the interview. He also conducted individual and key informant interviews. The interview guide had three main areas: 1) local perceptions and practices around education; 2) local perceptions of dropouts and 3) the underlying reasons for dropouts. Although Murad wanted to include the views of female teachers and mothers, he had no access to them due to sociocultural gender constraints.

As per research ethics, all discussions, whether individual or group, were carried out after obtaining informed consent. Discussions were audio-recorded with the permission of the participants. Moreover, pseudonyms are used to ensure confidentiality. Using data saturation as an indicator, we ceased further data collection and shifted to analysis.

This begs a brief description that how did we reach saturation? While drawing upon (Sandelowski’s 2008: 75) concept of “informational redundancy” that when a researcher listens to similar views time and again, s/he reaches data saturation. The same stands true in our context, when the responses of our interlocutors began to repeat and no new data emerged, the field researcher stopped collecting data any further. Thereafter, we started analyzing the already collected data.

Thematic analysis was used to identify cross-cutting and common themes. We grounded our categories in our data as well as our theoretical framework (Ryan and Bernhard 2003) while agreeing with Ian (Dey, 2003, P.17), “There is no single set of categories waiting to be discovered. There are as many ways of “seeing” data as one can invent.”

With the flexibility to extend, modify, and discard categories (Dey 2003), we analyzed these data by reading the entire dataset several times to identify relevant themes, followed by listing, summarizing, reviewing, and refining them. Our analysis addressed the following questions: 1) How do local people perceive education? 2) What are local perceptions and factors regarding dropouts, and 3) what drives children to leave school prematurely?

We also deem it pertinent to mention here that our research is anthropological and hence, qualitative in nature. Rather than quantification, the article aims to arrive at an in-depth understanding of the reasons for school-dropouts from an emic perspective. We do not claim that the results are representative of the entire population. What we insist is that the research does provide insight into the social, cultural, economic, and political factors leading to early dis-enrollment in schools. Another limitation of the research is that it focuses on boys who have dropped out of school. Despite our deep interest, we could not cover female dropouts, primarily due to gender norms, time and resource constraints. It must be noted here that in Pakistan generally, and in rural, semi-rural, and semi-urban areas specifically, schools are gender-differentiated with boys and girls learning separately; the school space is often not co-gender. However, we believe that our research provides a baseline for future research on the topic.

Theoretical Framework: Capabilities, Approaches, and Education

Our research is based on the theoretical premise of Amartya Sen’s (2005) groundbreaking capabilities approach, which is a normative and moral framework developed as an alternative to narrow economic metrics approaches to development and utilitarian or resource-oriented approaches. Sen’s approach establishes a deep correlation between freedom and function, whereby a capability can only be a function if there is an opportunity. The greater the opportunity and the freedom to choose, the better the chances of transforming a capability into an actual function. Nussbaum (2006) states “Nothing could be more crucial to democracy than the education of its citizens.” And according to Saito (2003), there is a seemingly a potentially strong and mutually enhancing relationship “between […the] capability approach and education.” The capabilities approach is crucial and significant because, unlike other approaches, it emphasizes “the intrinsic and noneconomic roles that education plays” (Robeyns, 2006). The intrinsic aim of educational policy should be to expand people’s capabilities (ibid.). Education to enhance people’s capacities has also been endorsed by the World Declaration on Education for all (Article 1 (1) (1990). It should be able to meet basic learning needs so to help people “to be able to survive, to develop their full capacities, to live and work in dignity, to participate fully in [the] development, to improve the quality of their lives, to make informed decisions and to continue learning”—Article 1 (1) (1990). In a similar vein, Terzi (2007) links “capability to be educated” to “social justice”. This includes both formal as well as informal schooling. Terzi posits that an absence of education will not only harm the individual but also hinder the growth and expansion of other capabilities. For her, education is one of the basic capabilities with the potential to play a substantive role in human growth and development.

The issue of student retention in educational institutes has existed for as long as schools have existed. Studies reveal that dropping out of school is not entirely a state's matter nor an issue of education provision; several factors at individual, social, and institutional levels lead to low retention and critically high dropout rates (Stearns & Glennie, 2006; Hunt, 2008; Abar, Abar, Lippold, Powers, & Manning, 2012; Rumberger & Rotermund, 2012; Feldman, Smith, & Waxman, 2017). Rumberger’s (2001) extensive study on dropout children in the United States further confirms this point. It presents a fact that is contrary to the general perception that in high-resource countries, almost all children complete their education: for example, the number of dropouts in the United States is over a million. Furthermore, it is important to understand that dropping out is not sudden but processual. Alexander et al. (1997) argue that “dropping out is the culmination of a long-term process of academic disengagement”.

Having noted that dropout causes reflect an interplay of individual, familial, and societal factors, this qualitative study sets to explore these multiple causes in Sindh province.

A Brief Overview of Pakistan’ Educational System

Pakistan confronts several challenges that are significantly interdependent and complex. In 2019, it was placed at the 152nd position out of 189 countries in the UN’s Human Development Index (HDI) (Government of Pakistan, 2020). Over the years, it has not shown significant improvement in educational indicators, such as literacy rate, overall enrollment rate, in comparison with neighboring countries. The overall literacy rate is 57%, primary dropout 22.7%, and education budget allocation is approximately 2.3% of GDP (ibid.). The literacy rate is higher in urban areas (74%), compared to rural areas (51%). Provincially, there is a significant difference in terms of formal literacy rates. Punjab has the highest literacy rate, with 64%, followed by Sindh with 57%, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) (including Merged Areas)2 with 55%, and Baluchistan with 40% (ibid.). In 2018–19, the national Gross Enrollment Rate (GER) at the primary level (except for Katchi, that is, preparatory education or prior to any grade education) was 87% for the age group 6–10 years. Again, Punjab province has a high rate of 95%, Sindh 78%, KPK (excluding merged areas) 89%, and Baluchistan 57% (ibid.). Likewise, the primary level Net Enrollment Rates (NER) of the country are: Punjab 73%; KPK 66%; Sindh 58%; and Baluchistan 40% (ibid.) (see Table 1). These various figures explicitly reveal the critical state of education in Pakistan and the government’s failure to prioritize it.

Results and Discussion: Education and Dropout Problem

Local Perceptions of Education

Bringing a local perspective of education is indispensable to know what it means for the local people of Sindh. Education has been perceived as a means to an end: finding a good job to earn money. For instance, the following quote of a male interlocutor, age 50, reveals that it is a form of greed to obtain education only for getting a suitable job:

Education is necessary for every child, making him/her good not merely for finding a suitable job, but acting as a responsible member. That is why education is compulsory for everyone: if one is educated, one can make his/her life good and easier to live. Despite that, the importance of education is not sufficiently recognized in our society. It is viewed as a consumption activity and an investment good. There is greediness in the education system since everyone sees education from an economic perspective. For instance, if I will send my children to school or college, they will be engineers or doctors and they will make money. If we eliminate the factor of greediness from education, it may cause society’s development.

In contrast, another interlocutor stated that in Pakistan, people have linked education to obtaining a job, earning money, and acquiring status and power.

People lack awareness regarding education. If their children do not get jobs after receiving education, it leads them to believe that education has no benefit. Due to this, economically poor people are hesitant to send their children to school, because in the end neither they secure a good job nor they are willing to work as laborers.

This quote can be understood against the backdrop of existing unemployment in the country, that is, around 4.45% (Government of Pakistan, 2020). Not finding a suitable job after completing education is a complex phenomenon. There are two main reasons for it: 1) inappropriate education that is again a result of several factors such as unqualified teachers, lack of educational institutions, and the government’s low priority. 2) A dearth of employment opportunities is also related to the government’s policies and practices.

Perceptions of Private Vs Government Schools

The private and government (public) schools have received sufficient attention from researchers for illustrating their causes and consequences. Some view that private schools can increase the inequalities in the educational system as they fail to reach economically poor and rural children (de Talance 2017). Yet, others argue that private schools can ensure access to education by relaxing the governmental financial constraints, especially where the number of public schools is not enough. These private schools can also increase the competition to achieve and deliver high-quality education (Hoxby 2007; Aslam 2009).

Similarly, our interlocutors consider private schools more academically rigorous than government or public schools. For them, private schools can create their own curriculum, have honor codes and stricter behavioral standards that help students to be mature adults. These schools have lower numbers of students per classroom; thus, it is easier to control pupils. Various paintings, colors, and drawings on the walls create a positive impact by enlivening the atmosphere, which is not nearly as attractive in public schools.

In contrast, interlocutors view public schools differently in that these schools face significant issues, especially related to administration and budget, which result in a dearth of facilities and less discipline. In the past, Pakistan’s public school system was capable of producing well-informed and well-evolved students. The fact that it no longer does so has made many parents who can afford them consider private schools to be a better option for educating their children.3

Causes Shaping School Dropouts

Many factors are associated with dropouts that relate to individual perceptions and practices and national-level politics, policies, and praxis. In the following sections, we describe and analyze some of these, including corporal punishment; lack of essential facilities; lack of parental interest and encouragement; peer group pressure; economic constraints and the need for child labor; children’s lack of motivation; and low self-esteem and increasing absenteeism that eventually leads to dropout.

Corporal Punishments

Corporal punishment is one of the primary reasons children mentioned why they wanted to drop out of school. Children were punished for distinct reasons: not completing their homework and classwork regularly; making noise in the classroom; not paying due attention to the teachers; irregular attendance; and absenteeism. Corporal punishment, threats to physical reprimand, admonishment, and warnings are considered effective tactics to ensure students’ compliance. While discussing various forms of corporal punishment, students lamented being told to hold the ears through legs as the worst form of penalty. This being an undignified and severe stress position, is recognized as a physical as well as mental punishment, as it leads to an intense feeling of embarrassment. Other forms include twisting of the ears, striking with a cane stick or wooden ruler on the palms, and made to stand for an extended period of time, causing fatigue and discomfort. In some cases, these strategies have even been normalized, oddly enough, by the students as well. For instance, students would prefer being beaten with a stick than to sit in an undignified position; the latter, as mentioned earlier, causes unprecedented shame and humiliation. The question then arises aren’t the other forms of corporal punishment not a source of embarrassment? Also, why some forms of punishment, although disliked, are accepted while others are despised and detested? This could best be understood by situating punishment within the larger context of hegemonic and normative masculinity. Being able to tolerate physical infliction is a characteristic typified by social norms of masculinity. Bearing cane strikes, enduring the pain caused by twisting of the ears as well as being able to stand for an extended period of time, are not merely punishments but also challenges to one’s physical strength. As against these, holding the ears through the legs is locally termed as murgho bannain, literally, to make a rooster, which leads to ridicule by fellow students. It is pertinent to note here despite the categorization of various forms of corporal punishment from worse to worst; all of them are disapproved and mentioned by the dropped out students as a reason for their disengagement from school.

In contrast, both parents and teachers hold different views about corporal punishment. They regard it as a necessary means of discipline to enforce obedience. Apart from compliance, a few teachers stated that corporal punishment is an effective tool in making students do their best. In this context, it is noteworthy that parents, however, are not appreciative of the extensive and frequent adoption of physical punishment as a measure to discipline students.

Lack of Facilities

In the schools of Sindh, children face many problems. Government school buildings are extremely unattractive, with peeling paint and no internal or external decoration. Many buildings are too old as teachers and students fear that these buildings might fall during any heavy monsoon rain. Even the schoolrooms are not tidy and clean. They lack basic facilities, such as libraries, proper or well-maintained toilets, water, sanitation, and sufficient electricity. In addition, most schools are far away from villages entailing long rides in ill-maintained buses.

More importantly, government schools have insufficient teachers, and most of the teachers that they have lack appropriate training and capacity. As one teacher stated:

Teachers have less knowledge about the psyche of children required to develop children’s interest in education. These issues are further exacerbated due to a high number of students for one teacher, as I have to teach 90 students, which overwhelms me. How can one teacher manage such a large number of children? This affects the learning processes and the image of government schools and teachers.

Likewise, another interlocutor, a teacher, stated that water deficiency and insufficient furniture are two prime issues in his school. Although there is a laboratory, appropriate and up-to-date equipment for conducting experiments is unavailable. He sees the entire education department as dysfunctional; thus, basic needs remain unfulfilled.

Parental Attitudes, Involvement and Role in the Education of Children

Lack of parental motivation, interest, and involvement have emerged as important factors for a child’s discontinuation of school education. Many interlocutors stated that the family environment is incredibly influential. Low parental participation, absence of parental supervision, parents’ educational background, and interaction between parents and children on matters related to education; all play a significant role in a child’s successful educational path. Often uneducated parents do not send their children to school, given their economic and sociocultural background and lack of access to information about the value and importance of literacy, education, and consequent prospects.

In this vein, the essentiality of parents’ concern about a child’s education has been particularly emphasized. The findings suggest that most of our interlocutors tend to believe-that since the child is a minor and is in his formative years, parental supervision is deemed necessary and that the early years are fundamentally crucial as children learn the most during the process of socialization. It has been observed that parents show great concern that their children learn culturally appropriate and acceptable behaviors (see Weisner, 2015) necessary to live a good life in their society. Our interlocutors believe that in the early years parents must teach their children about morals and attitudes, how to behave, and what to do. And parents must provide them with the right environment at home.

One of our interlocutors believed that educated parents, given their own experience, perform better in ensuring a favorable environment to a child’s educational path:

Educated parents create a conducive educational environment that helps develop a knowledge-seeking attitude and an inclination to school among children. See, home is a kind of school where we learn many things about our life. Then comes society’s influence.

Parental attitude sets a primary base for education. Similarly, a lack thereof results in truancy. In early years, given a child’s age and maturity, parents are held responsible for their child’s actions, thus the same interlocuter continues:

The reason for the dropout of children from school in my point of view is the parents’ attitude towards their children: They don’t care for their children; they are unconcerned and unaware about their activities.

A parent’s duty far extends just the facilitation of a child’s access to education. Parents, according to our respondents, must keep a check on a child’s activities in and out of the house. Seeking a regular update on a child’s progress in school and vis-à-vis education is also a parental obligation. A proportional connection is drawn between activities at home and performance in school. A child with irregular sleep habits will not be able to concentrate in school and bring good results. At times, parental supervision is spoken of not just in terms of simple supervision but strict surveillance.

Parental involvement in a child’s education is necessary. They should have a check on their children’s attendance, homework, and watching late-night television. These will result in the best education. Yet, parents in our area show a lack of concern as they do not inquire from their children about their studies, school environment, the difficulties they face and whether or not they attend school. This necessary atmosphere is an essential factor behind the dropout of children.

Communication between parents and teachers is of utmost importance. Both, in their individual capacities and positions, are held responsible for a child’s upbringing and education. The essentiality of the interaction between parents and teachers is explained in syllogistic terms; both are closely related to a child, both are responsible for the education of a child, and both are also assigned supervision and surveillance of the child. Hence, it makes only sense that both must remain in contact with each other to update and discuss a child’s progress. One of our interlocutors explained:

Furthermore, there is a considerable gap between teachers and parents in terms of communication and coordination. Lack of resources and poverty are also the primary reasons as parents are busy earning a living the entire day, return late in the evening, and cannot manage to keep track of their child’s performance and attendance in school.

In the case of a child’s low performance, parents, especially those from lower socio-economic status, insist on the child to work instead. It is informed that in cases where children work to earn, parents are seldom regretful of their child’s low literacy. In the case of our interlocutor, who is now a tailor and around 50 years of age, the low quality of education leading to low performance was the reason for leaving school and education in favor of skill-based learning:

I don’t know how to read and write. I am even unable to read the Sindhi newspaper. Although I attended high school, my reading skills are minimal. This is because I received a low-quality primary education. Without any proper examinations, my teacher issued my passing certificate to be enrolled in a high school. Gradually, I left the school and joined a tailor shop as an apprentice to make my life better. Without compelling me to go to school, my parents asked me to work if I wanted to quit my education. They happily allowed me to join a tailor shop, as they were willing to send me to Saudi Arabia to earn more money.

While the above response by our interlocutor was primarily aimed to establish a link between low performance and school dropout, it also inadvertently brings to notice the low quality of education and incompetent systems. Rather than investing to improve the performance of a student, he is unduly promoted. What could be the reason behind this? Several factors may have led to this. First, to show better success in terms of a higher rate of students clearing the exam, the schools promote even weak or slow learners. A second important reason could be the retention of students in a class to improve learning would also imply an increased number of students to educate. In public schools where the student-teacher ratio is already extremely disproportionate, this would entail an increased burden on the teachers. However, this is not the topic under discussion. For the purpose of this article, it suffices that students are sometimes undeservedly and unduly promoted, which does not help them in concrete ways.

At times, teachers are approached by parents for lenient evaluation of their children, albeit rarely. Another male interlocutor who is now in his late 20 s and had left school informs about other forms of corruption. He never paid attention to his studies, rather his family would always find some reference or contact to approach his teachers to get his assignments done by others. He stated:

My parents spent extensively on my education as we had no financial issues. Although they bore expenditures, they never paid attention to whether I was learning something new; or doing my homework. They enrolled me in a government school. After school time, I used to play cricket. I had no idea about my education and my future. Precisely, I was unable to learn anything. I just received certificates. As a result, I did not continue my education and I became a barber. My parents are interested to send me to a foreign country as several people from our village work in Saudi Arabia.

Some parents argue that children also leave school because parents need their help with their work. This is because economically poor people cannot afford the costs associated with going to school. The education itself—from primary to 8th grade—is free of cost as the government provides textbooks. Yet, a uniform is necessary for high schools, and the monthly expenditure of a child averages 4–5 thousand Pakistan rupees (around 30–40 United States$).

The collective efforts of parents and teachers could maintain the overall balance of an educational system. Ideally, parents should be aware of their child’s daily progress and teachers should look after children. Yet, the reality is critical; as our data demonstrate that 7 parents out of 10, most of whom engage in daily wage labor, are too tired at the end of the day to ask their children what they learned. And many mothers would not even know what to ask, as many have very little or no formal education. Yet, a mother’s role can be vital in sending her children to school and encouraging them to complete their education.

Economic Constraints and Consequential Child Labor

For most interlocutors, household resources, particularly income, play a significant role in children’s education, facilitating it in cases of financial abundance and vice versa. Household income is the money earned mostly by the father or both parents to bear all family expenses, including children’s education.4 Schooling expenses include both upfront and hidden costs. Upfront costs are the school fee, while as has been previously noted hidden costs include uniforms, transport, notebooks, sometimes books, and others.

“In our society, children who quit education mostly belong to a poor family,” noted one of our interlocutors. He further explained that in their area, agriculture is the primary source of subsistence, except for a few. Most people are living in poverty and are barely able to fulfill their basic needs, such as food and shelter. Under such circumstances, a child’s education is considered a double financial burden: 1) it entails expenditure; and 2) it also entails losing a potential earning hand. Irrespective of age, a child is considered responsible to contribute to the family’s earnings—no matter how small or big, the belief is that each contribution counts. Economic resources are directly and adversely proportional to education: the lower the resources, the lesser the possibility of sending a child to school, and vice versa. Financial constraints resulting in an inability to meet the basic needs of life have emerged as the most influential reasons shaping people’s perceptions about education. When a family is unable or barely able to meet its basic needs, education is rendered insignificant.

Several interlocutors believe that lack of monetary resources is the primary cause of children dropping out of school. When parents are unable to afford school expenditures, they send their children to work. A few informed us that school dropouts are sent as apprentices to learn an occupational skill, for instance, to mechanics, barber, or tailor. Children leave school on their own or by their family’s will. The school has little role to play in this decision. For instance, Amjad, a 14-year-old boy, was substantially compelled by the circumstances to discontinue his education. He dropped out of school in 8th grade owing to his father’s demise. He has been working for 5 years now, along with his mother, to earn enough money for their family’s sustenance. He stated:

My family has many problems. The biggest problem is money, especially a regular income, which compelled me to leave school. I studied in a private school, but due to economic reasons, I left school and my studies. Now I am an apprentice to a mechanic, and I am trying to learn the skill. After my father’s death, being the eldest son, I had to support my family. My mother also works for the well-being of our family. I miss my father at home. I used to go to school when my father was alive.

Another interlocutor indicated the necessity of each family member to contribute to agricultural activities. As previously noted, agriculture is a primary source of subsistence for many in rural areas of Sindh. The work is still done manually; modern technologies, except tractors and threshing machines, are beyond the financial reach of these agricultural families. Children can help greatly by working in the fields. In the Sindhi language, there is an expression, Jaitra Hath Otro Faida. Its English translation is something like “as the hands, so the benefits.” In other words, the more hands working in the agriculture fields, the more crops can be seeded and harvested. Consequently, during the different phases of crop production, many children miss school, thereby reducing their school attendance to only 2–3 months. Thus, they find it extremely challenging to keep up with their studies.

Teachers also pointed to parents’ low income as a significant reason for dropouts. During an interview, one teacher argued that parents who earn less do not believe education to be a requirement equivalent to food, clothing, and shelter. They feel that parents have more responsibility by using their children to help fulfill these basic family demands rather than sending them to school. One headmaster said:

Parents who work on a daily wage basis are primarily concerned about food provision. With such impoverished circumstances, how can they think of sending their children to school? If parents feel that their children are capable enough of earning, they force their children to work rather than supporting their schooling. Only children who are from families who have sufficient economic resources continue their schooling and complete the full cycle of education.

One of our interlocutors believed that it was a waste of money to send an uninterested child to school. Rather than investigating the reasons for his children’s lack of interest in education, Ali decided to send his boys to work and earn when they left school.

I am a laborer; I try to provide my children with a good life and education. Nevertheless, they showed no interest. I am unable to understand why they left school, but when they did, I sent them to learn a skill. They need to know the skills for better survival. My daughters have completed their 10th grade. They were never absent from school, so I continued to pay their fees.

Some parents force their sons to work somewhere to earn money. For example, Rizwan was asked by his father to leave school when he was 14 years old and in 9th grade; he said, “When my father asked me to work and contribute to the family’s income, I started to help him in his shop. I could no longer attend school regularly.” When approached Akram, Rizwan’s father confirmed that while he believes in the importance of education, he could not sustain the entire family’s responsibility alone. Having eight sons, he asked his eldest one, Rizwan, for support. Sacrificing the education of one has helped him provide education to others. It is not because of school expenditures that Rizwan had to drop out but to meet the family’s basic expenses, as is evident from Akram’s explanation.

I send my other sons to school. All of them are receiving free education from different schools. Three of them go to a school run by one NGO, the others to a government school. Rizwan and I are working for our family. I have done my F.Sc. [12th-grade] but am unable to secure a good job. I do not have any hope in the government. They do not look after the poor. I am sending my other children to school only because there the education is free. For some, it is the family’s sustenance leading to dropping out of school; for others, it is the inability to sustain expenses in continuing education.

In Akram’s case, the number of his other children is one of the entangled factors that shaped his decision to force his son to quit education and start working. Similarly, Ashraf, a boy aged 14, dropped out of school when he was in his 6th grade. Reflecting upon the reasons leading to the discontinuation of education, he says:

It is difficult to provide for the whole family for 6 months with the earnings received from farming. We are compelled to work on daily wages to sustain the other 6 months. My parents cannot think of sending me to school as this would mean more money to buy uniforms, notebooks, examination fees, and bearing all that is required to continue schooling.

We call child labor “consequential labor,” as most of our interlocutors send their children to work instead of school as a consequence of their financial circumstances. As we have seen, male dropouts engage in various forms of labor—skill learning agriculture or trade. Girls are mostly involved in domestic labor. One interlocutor who was a primary teacher blamed the parents for not making an effort and for being short-sighted in terms of looking for immediate benefit rather than long-term advantage:

After school hours, children from our school work in the market. Their parents do not care if their kids are receiving due education or not; they only care about money! They prefer money over education—money rules. Money makes life easier. Everyone, except us, believes that! It’s just us, the teachers, who keep insisting on education as being the most important and fundamental. We tell them that without proper education, life is hard. We motivate children to complete their education to be able to secure even better jobs in the future.

Children’s’ Lack of Motivation and Low Self-Esteem

Our research reveals variations in children’s understandings of education, their interests, and their attitudes towards learning and school. One reason for dropout that we have not yet discussed is age concern. For Ahmed, who was 17 when he dropped out of 7th grade, being over-aged resulted in self-consciousness and shyness, which were his main reasons for dropping out of school. “Being the oldest among my class fellows and overage for my grade, I always felt shy,” he confided. He also identifies this as the leading cause of his multiple attendance infractions.

I remained absent from school during most of the days of the week. I would miss my classes and roam with my age mates, play games with them, or chase stray dogs for fun.

Azmat, an 8th-grade dropout, holds his lack of motivation and inefficiency. His self-recognition as less intelligent is indicative of low self-esteem.

I was not a smart student. I never understood what was being taught. I never made an effort, neither in school nor at home. I left school in the 8th grade because I could not read the Sindhi script. If I were smart, I would have continued no matter what. Now I feel guilty for not completing my education. I think I never had the capability.

Although Azmat entirely blames himself for leaving his education unfinished, a closer examination one can easily note the unfavorable educational environment. It is not just his individual failure, but also a failure of the system that could not upkeep the morale and self-esteem of its pupils. An interlocutor who is a teacher discusses psychological issues among students and their root causes:

Students with inadequate clothing and supplies lack confidence. When they see their poverty highlighted by the affluence of other children, they feel less confident. Poverty adversely affects mental health. Poor people have a lot on their minds, such as their day-to-day needs, children, their school, and job insecurity.

It is interesting to note that while this teacher shows a clear and more in-depth understanding of students’ mental health issues, he has nothing to say about schools’ or teachers’ potential role in addressing these issues.

Peer Group Influence

Last but not least, peer influence also plays a significant role in shaping specific views about dropping out. Those children whose friends and peers-leave the school show a higher risk of dropping. Children mentioned that seeing their peers without any worries about schoolwork and engaged in leisure activities inculcates in them a desire the same life, free from the worry of education. One 11-year-old boy shared that he likes to take cattle to the grazing fields and be with other friends rather than study. He feels happy when he is with his friends as they play various games—that is, easy while studying is hard.

This peer influence similarly works in the opposite direction, that is, when children see their peers going to school, they often want to do the same. As one teacher stated, since peers and friends are closest to a child besides their family, their habits have a remarkable impact on the choices made by their peers.

Some of the children we interviewed did leave their schools due to peer influence. One male child shared:

I left school due to my cousin and brother. We remained absent from school, played video games in the market and kept wandering in the town. Although the teachers punished us, we did not care about that. Gradually, our interest in school diminished. First, my cousin left school, and then I did the same as without him, it felt strange and boring in school. Since I was bad at school, my comprehension was poor. Our parents paid our expenditures, but our lack of interest in education became the more significant reason to quit education. Nowadays, I do nothing in my life. Although my parents compelled and punished me for not continuing school, I still left.

Anwar was 14 and living in a joint family. His father had died, his brother was a shopkeeper, and two sisters were married. He was the youngest of his siblings and a bright student. The economic condition of his family was not good. He left his primary education due to losing his interest in studies when his close friend left school. Anwar justified his act of not going to school by saying that he needed to help his mother with household chores. In contrast, his mother wanted her son to receive an education and insisted that he must do so. However, nothing worked. During discussion with Anwar, he said that his friend’s parents did not force his friend to go to school. Showing no understanding of the importance of education, he said that he planned to get married after a few years and for marriage, education is not required.

From Absenteeism to Dropping Out

As noted earlier, dropout is processual—the culmination of a long process. The interplay of the various factors discussed above influences this decision. Repeated absenteeism is one of the processual steps to dropping out of school, standing next to the financial constraints discussed above. An interesting finding of our research is that, while absenteeism is viewed as a “cause” of dropout by teachers, students conceptualize it as a “consequence” of their circumstances. Our research shows that the rate of absenteeism and dropout is higher in high school than in primary school. Adil, a teacher in public schools, believes that:

Absenteeism is a serious issue as far as school dropout is concerned. If a child remains absent from school after a few months, he will undoubtedly leave school because he cannot develop an interest in education without being present. Absenteeism in high school is higher than in primary school children. High school children reaching adolescence miss their classes frequently.

For students, however, numerous factors contribute to absenteeism, the school environment being a significant contextual factor. A lack of student’s connectedness and sense of attachment to their school, their paucity of interest in curricular and extracurricular activities, social, and other needs have been identified as a few significant reasons. “If students feel safe, valued, and respected in the school, they will not remain absent from classes or school,” suggests one of our interlocutors, also a dropout.

Conclusion: Dropout a Processual Phenomenon

Even though education is a fundamental right of every child that is enshrined in different conventions nationally and internationally, such as UDHR 1948 and the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child 1989, in Pakistan’s Sindh Province, as in many other areas of the country, education is neither accessible nor affordable for many children due to the various entwined factors we have described above. Since the basic right of education is being denied to many children in Pakistan owing to individual, family, sociocultural, economic, and political factors, there is a need to make necessary efforts at the parental and school levels, as well as at the national policy level, to address these multiple factors. Employing Sen’s Capabilities Approach, we have shown a relationship between freedom and function, whereby a capability can only be a function if there is an opportunity. While successful completion of education means a capability positively transformed to functioning; dropout connotes the right to basic capabilities, freedom, and functions denied. Paucity or unavailability of several O-capabilities adversely affects P and S capabilities. These deficiencies are identified on several levels: individual, social, circumstantial, and institutional. It is interesting to note that the state’s role has not been mentioned directly, however, it is the state’s failure to provide an adequate and functional education system that can easily be deduced from the narratives. Through careful analysis and reading of our interlocutors’ narratives, we argue that dropout is not an incidental but a processual phenomenon. Arguing that it is consequential, resulting from several push factors, the dropout child is seen caught in a vicious circle of varied issues, primarily of financial nature.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because This is because our article contains most of the first-hand data in the form of quotes. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to aW5heWF0X3FhdUB5YWhvby5jb20=.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Quaid-i-Azam University’s Ethical Committee. Written informed consent from the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

SA: conceptualization, contribution to the first draft, analysis, revision, and validation. SMA: data collection, contribution to first draft, and validation. IA: contribution to the first draft, revision, and validation.

Funding

We received no funding that needs to be delcared.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1We are not using terms of “majority” and “minority” in a politically loaded manner, but in terms of total number of the population.

2In 2018, of the seven Tribal Districts became part of KPK: Bajaur, Mohmand, Khyber, Orakzai, Kurram, North Waziristan, South Waziristan.

3For more discussion, please refer to (Ali & Abid, 2021), Optimist about Education, Pessimist about Schools: People’s Perception Regarding the Schooling System.

4We are mentioning that in most families, fathers are the money-earners as most mothers, especially in rural areas, are homemakers.

References

Abar, B., Abar, C. C., Lippold, M., Powers, C. J., and Manning, A. E. (2012). Associations between Reasons to Attend and Late-High School Dropout. Learn. Individ Differ. 22 (6), 856–861. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2012.05.009

Alexander, K. L., Entwisle, D. R., and Horsey, C. S. (1997). From First Grade Forward: Early Foundations of High School Dropout. Sociol. Educ. 70, 87–107. doi:10.2307/2673158

Article 25a – right to education (2018). Article 25a – right to education. Retrieved from: https://rtepakistan.org/.

Aslam, M. (2009). The Relative Effectiveness of Government and Private Schools in pakistan: Are Girls Worse off?. Education Econ. 17 (3), 329–354. doi:10.1080/09645290903142635

Bourdieu, P., and Passeron, J.-C. (1977). Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture. London: Sage Publication

Dey, I. (2003). Qualitative Data Analysis: A User Friendly Guide for Social Scientists. London: Routledge.

Feldman, D. L., Smith, A. T., and Waxman, B. L. (2017). Why We Drop outUnderstanding and Disrupting Student Pathways to Leaving School. London: Teachers College Press.

Gasper, D. (1997). Sen's Capability Approach and Nussbaum's Capabilities Ethic. J. Int. Dev. 9 (2), 281–302. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1328

Government of Pakistan (2020). Pakistan Economic Survey 2019-20. Retrieved from Islamabad: http://www.finance.gov.pk/survey/chapter_20/10_Education.pdf.

Hoxby, C. M. (2007). Dropping Out from School: A Cross Country Review of the Literature. The Economics of School Choice. Berkeley: University of Chicago Press.

Hunt, F. (2008). Dropping Out from School: A Cross Country Review of Literature. Sussex: University of Sussex, 16.

Nussbaum, M. C. (2006). Education and Democratic Citizenship: Capabilities and Quality Education. J. Hum. Dev. 7 (3), 385–395. doi:10.1080/14649880600815974

Peiró i Gregòri, S., Merma-Molina, G., and Gavilan-Martin, D. (2014). The Integration of Values, Skills and Competences in Quality Education through the Subject “Computer Science”.

Robeyns, I. (2006). Three Models of Education. Theor. Res. Educ. 4 (1), 69–84. doi:10.1177/1477878506060683

Rumberger, R. W., and Rotermund, S. (2012). The Relationship between Engagement and High School Dropout. Handbook of Research on Student Engagement. Springer, 491–513. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7_24

Rumberger, R. W. (2001). Why Students Drop Out of School and what Can Be Done. Harvard University Press.

Ryan, G. W., and Bernard, H. R. (2003). Techniques to Identify Themes. Field methods 15 (1), 85–109. doi:10.1177/1525822x02239569

Saito, M. (2003). Amartya Sen's Capability Approach to Education: A Critical Exploration. J. Philos. Education 37 (1), 17–33. doi:10.1111/1467-9752.3701002

Sandelowski, M. (2008). “Theoretical Saturation,” in The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. Editor L. M. Given (Thousand Oaks: Sage), 875–876. doi:10.4135/9781412963909.n456

Sen, A. (2005). Human Rights and Capabilities. J. Hum. Dev. 6 (2), 151–166. doi:10.1080/14649880500120491

Stearns, E., and Glennie, E. J. (2006). When and Why Dropouts Leave High School. Youth Soc. 38 (1), 29–57. doi:10.1177/0044118x05282764

Syed Murad Ali, S. M., and Saadia Abid, S. (2021). Optimist about Education, Pessimist about Schools: People's Perception Regarding the Schooling System. ojs 4 (2), 13–20. doi:10.36902/sjesr-vol4-iss2-2021(13-20)

United Nations (1989). Convention on the Rights of the Child. Geneva, Switzerland. Retrieved from: https://www.unicef.org/child-rights-convention/convention-text.

United Nations (1948). Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Geneva, Switzerland. Retrieved from: https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/.

Keywords: education, dropout, basic right, sindh, Pakistan, capability approach

Citation: Abid S, Ali SM and Ali I (2021) A Basic Right Denied: The Interplay Between Various Factors Contributing to School Dropouts in Pakistan. Front. Educ. 6:682579. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.682579

Received: 18 March 2021; Accepted: 12 August 2021;

Published: 28 October 2021.

Edited by:

André Kunz, Zurich University of Teacher Education, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Angela Page, The University of Newcastle, AustraliaAriel Mariah Lindorff, University of Oxford, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2021 Abid, Ali and Ali. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Inayat Ali, aW5heWF0X3FhdUB5YWhvby5jb20=; Saadia Abid, c2FiaWRAcWF1LmVkdS5waw==

Saadia Abid

Saadia Abid Syed Murad Ali

Syed Murad Ali Inayat Ali

Inayat Ali