- 1Department of Competencies, Personality, Learning Environments, Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LIfBi), Bamberg, Germany

- 2Department of Developmental Psychology and Center for Psychological Innovation and Research, Faculty of Psychology, Universitas Padjadjaran, Jatinangor, Indonesia

During the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown, face-to-face schooling could not be performed continuously, and alternative ways of learning had to be organized. Parents had to act as their children’s home schooling tutors while working from home, and schools had to deal with various alternatives to distance education. Since parents are by all means both important school users and partners, their perceptions of schools can be considered a central indicator for assessing school quality. In this respect, during school lockdown, parents’ school satisfaction may reflect schools’ ability to adjust and react to fast social changes with almost no time for preparation. To date, there is nearly no knowledge about school satisfaction or school support during this challenging situation. Using data from the COVID-19 survey of the German National Educational Panel Study, we identified central predictors of parents’ perceptions of school support during the national lockdown in Germany in spring 2020. All students (N = 1,587; Mage = 14.20; SD = 0.36; 53% girls) and their parents (Mage = 47.36; SD = 4.99; 91% women) have participated in the longitudinal survey for at least 8 years. The results of the structural equation model indicate that the perceived support and abilities of teachers have been especially relevant for parents’ school satisfaction during the time of the school lockdown. In contrast, factors relating to parents’ and children’s backgrounds seem to be less important.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a major effect on nearly all aspects of life. During the first lockdown in Spring 2020, teachers, students and parents had to face the challenge of maintaining learning processes via remote schooling in Germany, as in almost all European countries (DW 2020). Short-term modifications without sufficient experience were necessary and forced all providers and users of the educational system to adjust to a sudden and completely new situation of home schooling. While teachers and schools had to provide students with learning materials, instructions and assistance by distance, parents had to function as home schooling tutors for their children while maintaining their regular jobs at the same time (Lagomarsino et al., 2020: 851f; Parczewska 2020). In such critical times, where parents have to be more actively engaged in their children’s learning programs (Bubb and Jones 2020), parents’ satisfaction with school becomes a crucial factor, reflecting schools’ ability to adjust and react towards fast social changes. Generally speaking, the construct accounts for a state in which parents are content with the way how schools handle the teaching of their child or with more general characteristics and performance of schools such as school infrastructures and school communication (Friedman et al., 2006). There is no universal definition for parents’ satisfaction with school and studies investigate the construct with a varying focus (Mossi et al., 2019: 1f). While successful parent-school cooperation and the perception of mutual support are always important for students’ educational outcomes (Dusi 2012: 20ff), they are especially vulnerable during times like this. Therefore, one indicator of a good school may be its ability to organize and deliver supportive, effective learning material (Giovannella et al., 2020), thus enabling parents and children to assess and comprehend the materials as well as possible. Accordingly, a perception of strong school support of overburdened parents during the school lockdown may serve as a critical benchmark of school quality. In addition to official measures, parents’ satisfaction with school could be one potential criterion for assessing the larger societal validity of school performance (Charbonneau et al., 2012). Parents’ school satisfaction demonstrated a significant relationship with the official measures of school performance, including schools’ characteristics and students’ performance (ebd.).

To our knowledge, so far, there is very limited research on parents’ satisfaction in the special situation of the COVID-19 pandemic, mainly focusing on a descriptive reporting of the status quo (Andresen et al., 2020; Anger et al., 2020; Huebner et al., 2020; Wildemann and Hosenfeld 2020; Thorell et al., 2021). Moreover, research on parents’ satisfaction with school in the German educational system in general is relatively scarce, and if existing, studies focus on the parents of younger children (Cryer et al., 2002). To date, no study has examined the predictors of parents’ school perceptions if their children belong to the adolescence cohort. However, knowledge about parents’ satisfaction with school is also important for older children, as especially during the sensible time of the adolescent phase a coherent social environment is important for the development of a young person (Perry et al., 1993). Prior studies also confirmed that generally during adolescence, parents continue to provide important developmental contexts for their children, particularly in form of discussion as well as role model (Behnke et al., 2004). The parents’ satisfaction with school expresses the quality dimension of the family-school relationship, which is associated with the educational development of students in general (Khajehpour and Ghazvini 2011; Charbonneau et al., 2012: 60f). Further, from an economic angle, parents are seen as important users of schools. Schools operate as institutions within an educational market and have the responsibility to meet the needs of their users or customers (Matland 1995; Fend 2008: 109ff). As parents are one relevant user group, their satisfaction should be of great interest for schools to maintain and report high-quality levels (Charbonneau et al., 2012; Peters 2015: 342f).

With this paper, we contribute to enhancing knowledge about parents’ satisfaction with school during the exceptional time of the school lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic. We assume that the critical situation during the school lockdown in Spring 2020, with highly necessary adjustments in schooling, has had a relatively deep effect on parents’ satisfaction. We further posit that there are special factors associated with the challenging situation during the school lockdown. Moreover, this is the first study on predictors of parents’ perceptions of school support in the German context if their children are in secondary school. Therefore, this article investigates central predictors of parents’ satisfaction with school support during the German school lockdown in Spring 2020.

We proceed as follows: First, we briefly summarize the current state of research on parents’ satisfaction with school, and give an overview of already identified predictors of parents’ satisfaction during regular times of schooling. There are a few published reports and first results on parents’ satisfaction with school during the pandemic, which we will introduce briefly. We then argue theoretically by using an economic and developmental approach to explain what influences parents’ views of school support during the lockdown, and conduct a theoretically driven hypothesis. In the data and methods section, we first introduce the used dataset, the German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS). We then define key variables and present the analytical approach of the structural equation model. The third section demonstrates the results, which are discussed in the final section.

State of Research

Parents are highly relevant educational actors, as they are both the actual consumers of the school and in charge of their children’s education (Fend 2000: 66f; Fend 2008: 109ff). However, many studies on school satisfaction focus on students’ rather than on parents’ satisfaction (Okun et al., 1990; Zullig et al., 2011; Casas et al., 2013; Weber and Huebner 2015; Arciuli et al., 2019; Arciuli and Emerson 2020). Studies on parents’ satisfaction usually refer to parents of younger cohorts who attend kindergarten or elementary school (Ulrey et al., 1982; Griffith 2000; Cryer et al., 2002; Bailey et al., 2003; Thompson 2003; Fantuzzo et al., 2006; Bassok et al., 2018). In general, parents of older children seem less satisfied with schools than parents of younger students (Thompson 2003: 280f; Fantuzzo et al., 2006), which may signal that parents of older children are likely to have higher educational expectations than parents of younger children (Stull 2013).

Most of the studies measure satisfaction with instruments that were constructed for more general purposes, and their psychometric properties were not structurally proven for assessing school users’ customer satisfaction (Mossi et al., 2019: 2). Therefore, inconsistent measurement of parents’ satisfaction with school is a challenge for comparing studies (Fantuzzo et al., 2006: 144; Mossi et al., 2019).

Generally, the relevant predictors for parents’ satisfaction with school of their adolescent children are far from clear. Above all, an in-depth analysis of relevant factors explaining parents’ satisfaction during the challenging situation of home schooling during the school lockdown in Spring 2020 is not yet available. There are some descriptive reports on learning processes during home schooling (Andresen et al., 2020; Andrew et al., 2020; Attig et al., 2020; Garbe et al., 2020; Parczewska 2020; Wildemann and Hosenfeld 2020; Wößmann et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2020), but no study examines predictors of parents’ perceptions of school support during the school lockdown. Descriptive reports show a tendency towards parents’ dissatisfaction with school and teachers in Germany during home schooling (Andresen et al., 2020: 17; Attig et al., 2020: 2f). However, parents report disagreement in satisfaction with the support they receive from teachers (Andresen et al., 2020: 17). A similar pattern can be seen for satisfaction with the information on the current situation on the part of the schools (Andresen et al., 2020: 17), implying that parents’ satisfaction during home schooling is influenced by various factors. Attig et al. (2020) found that the level of parental satisfaction with information provided by the school depends on the type of secondary school the children attend, with higher levels of satisfaction in academic track schools compared to non-academic track schools (Attig et al., 2020: 4). Interestingly, empirical evidence suggests a unique link between parents’ satisfaction and learning outcomes perceived by parents (Attig et al., 2020). More than half of the parents who were very dissatisfied with school support reported that their children were learning less during home schooling, while only 11% of parents with greater satisfaction reported similar learning feedback (Attig et al., 2020: 6ff). However, it is still unclear whether those differences in satisfaction are significant.

Prior research conducted before home schooling due to COVID-19 has reported that parents’ satisfaction is significantly affected by diverse factors, such as parents’ and children’s characteristics (Fantuzzo et al., 2006; Friedman et al., 2006), as well as by the programs and policies implemented by the schools (Bailey et al., 2003; Bassok et al., 2018; Perry et al., 2020). The literature denotes that cooperation between family and school is both a critical dimension of parents’ satisfaction (Tuck 1995; Smit et al., 2007; Sheridan et al., 2016) and an indicator of children’s cognitive outcomes (Christenson 2003). A good-quality parent-teacher relationship demonstrated a significant (indirect) link with high academic performance (Hughes and Kwok 2007), which in turn influenced parents’ satisfaction (Tuck 1995). Tuck (1995) investigated different areas of parental satisfaction in the US using primarily descriptive statistics, and found a unique connection between parents’ satisfaction and numerous school factors such as staff quality, school climate, academic programs, social development, and extracurricular activities. During the school lockdown due to COVID-19 in Spring 2020, parents reported in a survey that they would like to obtain more feedback from teachers (Wildemann and Hosenfeld 2020: 26f). This suggests that parent-school cooperation during home schooling may require some improvements.

Another focus of studies on parent satisfaction with school is the investigation of perceptions depending on specific group membership such as ethnicity, socioeconomic background, or the child’s special educational needs. With respect to ethnic backgrounds, the results are rather mixed. On the one hand, studies have reported different perceptions of schools across ethnic groups (Erickson et al., 1996; Griffith 2000; Thompson 2003; van Ryzin et al., 2004; Friedman et al., 2006), with a lower level of satisfaction demonstrated by ethnic minority parents than by ethnic majority parents (Friedman et al., 2006). On the other hand, Erickson et al. (1996) did not find any significant differences in satisfaction between white and ethnic minority parents, although non-minority parents showed more favorable attitudes towards teachers than ethnic minority parents did. Teacher effectiveness, school budget, parental involvement, facilities, and equipment are identified as essential aspects of schools reported by ethnic minority parents (Friedman et al., 2006). van Ryzin et al. (2004) found that black and Hispanic parents are less satisfied with public schools in the US than White and Asian parents, although socioeconomic status (SES) was controlled for. Interestingly, the differences diminish if neighborhood and trust are controlled for (van Ryzin et al., 2004: 622). Specifically, in Germany, children’s migration backgrounds were reported to be confounded by their parents’ SES (Dubowy et al., 2008). However, most studies seem to treat migrants as a homogenous group and do not differentiate between the social status of the families, although social status influences parent-school cooperation more than a migration background (Neumann 2012: 367). There is no report or study on school perceptions during the school lockdown of migrant or ethnic minority parents available yet.

With respect to the relationship between school satisfaction and SES (Griffith 2000; Chambers and Michelson 2020), prior studies document favorable attitudes, especially of parents with low income, towards their neighborhood schools, but weak connections to objective ratings of school performance (Chambers and Michelson 2020). During the first school lockdown in Germany, parents without academic backgrounds demonstrated higher satisfaction with school support than parents with academic backgrounds (Attig et al., 2020), suggesting that school satisfaction is a product of the level of education. However, parents with and without academic backgrounds reported similar levels of satisfaction with respect to the sharing of information and the delivery of learning material by schools (Attig et al., 2020: 4f). Further, since home learning qualities are greatly influenced by SES (Anders et al., 2012; Weinert et al., 2012), it is very likely that during home schooling, educational inequalities become larger as a consequence of distinct social backgrounds (Bol 2020; Dietrich et al., 2020; Lancker and Parolin 2020; Pensiero et al., 2020).

Previous studies revealed that parents of children with special educational needs are less satisfied with schools than parents of children without them (Ginieri-Coccossis et al., 2011; Beck et al., 2014; Perry et al., 2020). Families with children with special educational needs require more assistance from school. Therefore, school characteristics and structures seem to play an important role for this group; that is, the percentage of students with special educational needs in a school is negatively connected to parent satisfaction (Charbonneau et al., 2012: 61; Beck et al., 2014). Parents of children with special educational needs reported some negative experiences with home schooling more frequently (Thorell et al., 2021). However, those differences between families with and without children with special educational needs seem relatively small, indicating that parents in general had negative experiences.

In sum, empirical studies show that a key element of parent satisfaction with school is the cooperation between family and schools, including both good contact with the teacher and school (Griffith 1997; Griffith 2001) and favorable attitudes towards them (Patrikakou 2016: 115; Berkowitz et al., 2017). However, different effects exist, depending on individual characteristics, not solely from the parent but also from their children, teachers, and schools (Griffith 1997). Thus, these actors’ characteristics are assumed to determine parents’ school satisfaction during home schooling due to the lockdown.

Theory and Hypothesis

This study uses two theoretical approaches to explain parents’ satisfaction with school. First, an economic perspective explains user satisfaction in the educational market (Matland 1995; Fend 2008: 109ff). Currently, schools are increasingly seen as institutions of an educational market with a responsibility to fulfill the needs of their users or customers, and to show good results in comparison to other educational institutions (Bejou 2012). The economic approach strengthens the meaning of a competitive educational market in which customer-oriented offers of schools are in focus (Matland 1995). Parents’ satisfaction is predictive of school quality measures (Charbonneau et al., 2012: 61). As parents are a relevant group of school users, schools should have great interest in their satisfaction to maintain high quality (Wilson 2009: 574f; Charbonneau et al., 2012; Peters 2015: 342f). However, schools differ in how they can meet their users’ needs (Bejou 2012: 60). As the German school lockdown in Spring 2020 put the educational market in a challenging situation with short-handed major shifts in schooling, the fulfillment of users’ needs became a challenge for schools (Giovannella et al., 2020; Verma, 2020). With no time for sound preparation, schools and teachers had to provide students and their families with efficient distance learning materials, online teaching formats, and new exchange opportunities about learning processes at home (Bubb and Jones 2020; König et al., 2020). Notwithstanding, at the beginning of the school lockdown, many German schools were already lagging behind the transformation process regarding digitalization (Fraillon et al., 2019: 37f; König et al., 2020: 610f). Hence, proper family-school exchange and the maintenance of high school satisfaction are especially difficult. It makes sense that schools’ and teachers’ ability to react to such fast changes during the school lockdown in Spring 2020 would be important for parents’ satisfaction (Attig et al., 2020: 5). The better that schools and teachers can support home schooling during the school lockdown via remote and digital learning opportunities, the higher the level of parents’ satisfaction that can be expected. Therefore, the following hypotheses regarding the effects of school and teacher characteristics on parents’ satisfaction with school are formulated:

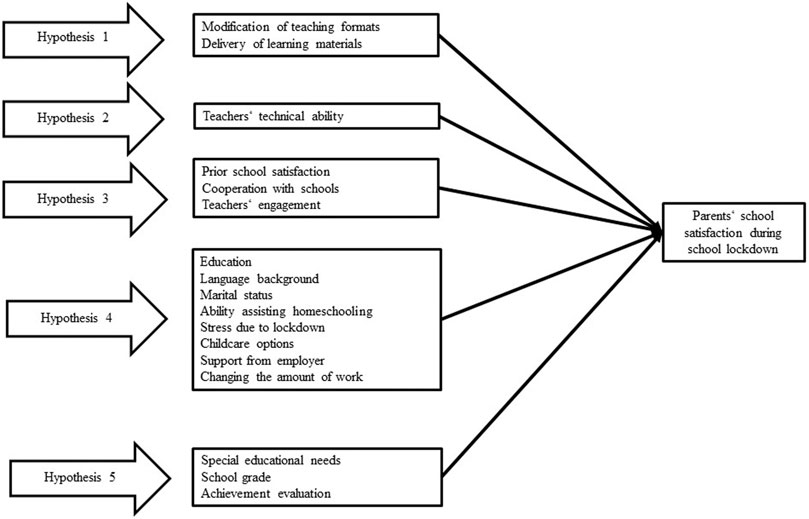

Hypothesis 1: The offer of distant learning materials and online teaching formats has a positive effect on parents’ satisfaction with school during the school lockdown.

Hypothesis 2: Teachers’ abilities, especially in terms of digital teaching formats, have a positive effect on parents’ satisfaction with school during the school lockdown.

The ecosystem framework is a second theoretical approach referring to the importance of a good family-school relationship in the child’s education from a developmental angle (Bronfenbrenner 1992; Christenson 2003: 458ff). Students grow up and learn within different microsystems (e.g., family or school). The relation between those different microsystems (e.g., the interaction between school and family) is reflected by the mesosystem (Bronfenbrenner 1992; Patrikakou 2016: 111). A successful and coherent interaction between the different systems both fosters students’ educational development and strengthens parents’ satisfaction with school (Friedman et al., 2007; Sheridan et al., 2016: 3). Thus, the better the actual cooperation between the child’s two most proximate microsystems (i.e., family and school), the better the mesosystem functions with the abovementioned positive implications for both the child’s development and the parents’ perception of school. Parents who show more favorable attitudes towards school and teachers have higher general school satisfaction (Tuck 1995), are more likely to become more involved in their children’s learning process, and have children with better learning outcomes than parents who show less favorable attitudes (Hughes and Kwok 2007).

The school lockdown due to the COVID-19 pandemic in Spring 2020 can be seen as a critical situation during which the well-experienced interaction between family and school was disrupted in comparison to times of regular schooling with a higher probability. However, empirical evidence has revealed that past family-school cooperation influences future cooperation (Tabellini 2008); therefore, the functioning of the interaction between family and school in the past should have had implications for such interaction during the school lockdown. Accordingly, a high level of parents’ satisfaction during the school lockdown was to be expected if there was high satisfaction in the past. Consequently, we formulate the following hypothesis regarding the relationship between parental satisfaction before and during the school lockdown:

Hypothesis 3: A high level of parental satisfaction with school in the past had a positive effect on parents’ satisfaction with school during the school lockdown.

One condition for successful parental support of the learning process at home is the existence of relevant home schooling resources (Andrew et al., 2020: 11ff), such as the availability of a certain amount of time to support the child’s home schooling; social support from other adults or one’s workplace, as an important element of the exosystem (Bronfenbrenner 1992); the parents’ own competencies and knowledge (e.g., educational backgrounds or knowledge of the majority language) (Dietrich et al., 2020: 4; Wolter et al., 2020: 2ff); and parents’ ability to manage stress due to overloaded role (Spinelli et al., 2020). Pre-COVID literature suggests that the organization of work based on flexibility with time and space (smart working trend) usually comes with higher satisfaction and better work-life balance of parents (Angelici and Profeta 2020). Though, during the school lockdown, working from home and simultaneously supporting home schooling became highly stressful for parents (Lagomarsino et al., 2020: 851f). Parents with lower access to temporal, social, and cultural home schooling relevant resources can support their children’s learning to a lesser extent (Bol 2020: 12; Dietrich et al., 2020: 9). Most likely, they both feel more overloaded and need more support from the school in facilitating their children’s learning than parents with a higher number of pertinent resources. In those cases, the family needs more support from the school to foster the child’s educational development. Nevertheless, as descriptive analysis shows, there was reduced teacher-student contact compared to other times, and online teaching was infrequent during the school lockdown in Germany (Wößmann et al., 2020: 32ff). In this respect, “the lack of teachers’ assistance” experienced by children during the school lockdown had to be fulfilled by parents. If schools cannot support parents in the way they need, then microsystems do not sufficiently work together (Bronfenbrenner 1992; Christenson 2003: 461f), resulting in a high risk for both parents’ satisfaction and children’s learning outcomes.

Parents’ overload should then become apparent in their lower satisfaction with school. Hence, the following hypothesis regarding parents’ resources can be formulated:

Hypothesis 4: Parents’ limited access to temporal, social, and cultural home schooling resources had a negative effect on parents’ satisfaction with school during the school lockdown.

Further, student characteristics can play a role in parents’ satisfaction with school (Griffith 1997; Charbonneau et al., 2012). If a student needs more learning assistance during home schooling, for example, due to special educational needs or poor school performance, the parent has to support the student’s learning to a greater extent. In such cases, an overload of the parent during the home schooling phase becomes more likely, and more support from other relevant parties such as school are needed. If the school cannot fulfill these needs, parents may view themselves as single actors in the learning process and therefore develop unfavorable attitudes and perspectives towards school. Hence, the following hypothesis regarding the child’s need for learning assistance can be formulated:

Hypothesis 5: The child’s comprehensive need for additional learning assistance at home had a negative effect on parents’ satisfaction with school during the school lockdown.

Figure 1 presents a brief description about constructs that relate to the hypotheses.

The following sections examine the hypotheses empirically.

Data and Methods

Sample

This study uses the national representative German longitudinal dataset of the National Educational Panel Study (NEPS) Starting Cohort Kindergarten, Version 9.0.0 (Blossfeld et al., 2011). Children were originally recruited 2 years before school entry (first wave) with additional sampling in the first year of elementary school (third wave). In addition to competence measures and children’s questionnaires, teachers completed a series of questionnaires, and caregivers were interviewed by phone (CATI) every year. In most of the states in Germany, students will be assigned to a specific school track after their fourth year of elementary school. Therefore, although school was originally applied as a sampling criterion, the nested structure of the data no longer exists if the children enter secondary school (for more details about sampling and the interview procedure, visit www.neps-data.de).

In this study, most of the students were in their eighth year of schooling or in the 10th wave of NEPS. In this unordinary time, there were no additional protocols implemented during data collection since the caregivers were interviewed by phone (CATI) as in the previous waves. The inclusion criterion was participation in the additional corona survey (May to June 2020) during the school lockdown from March to June 2020. The participants were 1,587 students (mean age of 14.23 and SD = 0.36 with 53% girls) and their parents (mean age of 46.99 and SD = 4.99, and 91% were women), while the number of participants in the first year of elementary school comprised 6,733 children and their parents (third wave). There are two important points that one should bear in mind with respect to the data. First, the data come from different measurement times (second year of schooling or fourth wave to eighth year of schooling or 10th wave. For more details about measurement time points and construct measured Supplementary Appendix S3). Second, the drop-out rate is related to socioeconomic status and migration backgrounds (see Würbach et al., 2006), which are also the subject of our analysis.

Measures

In this chapter, the operationalization of relevant constructs is addressed. Parents’ school satisfaction was implemented as the dependent variable, while other factors were modeled as predictors.

Parents’ School Satisfaction as an Outcome Variable

Parents’ school satisfaction has been implemented as a crucial factor for school assessment (Charbonneau et al., 2012). In this regard, parents’ perception of school is claimed to serve as a proper assessment of school quality (Charbonneau et al., 2012). Whether this thesis can be implemented for the assessment of satisfaction during school lockdown is rather questionable. Without a doubt, the school lockdown has had an enormous effect on school practices. All active participants in distance learning, including parents and schools, had to adjust to the new situation without sufficient time for preparation. It is unrealistic to expect that schools were comprehensively informed about all potential problems that parents could face during home schooling and vice versa.

In this study, parents’ school satisfaction during school lockdown is modeled as a latent variable with three indicators: general school satisfaction, satisfaction with the delivery of information, and satisfaction with learning materials. The first two items were rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 = “not good” to 4 = “very good.” The last item was rated on an 11-point scale ranging from 0 = “very dissatisfied” to 10 = “very satisfied.” The caregivers were administered those three items during the school lockdown between May and June 2020.

Parents’ Background Characteristics

Parents’ background characteristics were measured at distinct time points due to the structure of missing values. The years of formal education of the interviewed parents, as classified by the Comparative Analysis of Social Mobility in Industrial Nations (CASMIN) (Brauns et al., 2003), was implemented as the operationalization of educational level and measured at their children’s fourth year of elementary school. In this study, the CASMIN score of the parents ranged between 9 and 18.

The language background of the interviewed parents was measured in the children’s second year of elementary school and recoded into 0 = native German speaker and 1 = non-native German speaker. Information on parents’ gender (0 = men and 1 = women) was obtained from data in the children’s second year of elementary school, while information about income (ranging between 0 and 10,000,000 per year) was collected during school lockdown. Parents were asked about their marital status during their child’s first year of secondary school (fifth year of schooling). The original six-scale item of marital status was recoded into three categories: 0 = married and/or living together, 1 = married and separated, and 2 = single or divorced.

Parents’ Perceptions of Schools and Teachers Prior to School Lockdown

Prior to the pandemic, parents were administered various items related to their satisfaction with the elementary school their children were attending, their perception of teachers’ engagement, and their perception of cooperation with schools. All three constructs were modeled as latent variables.

Parents’ satisfaction with elementary school was reported in their children’s final year of elementary school (fourth year of schooling). Hence, this report does not represent satisfaction with the same school during the pandemic, when children were in their eighth year of schooling in secondary school. However, satisfaction may relate to personal characteristics (DeNeve and Harris 1998; Suldo et al., 2015), and we still expect a significant amount of variance to be explained by this construct. The indicators of school satisfaction prior to the pandemic include school time, infrastructure and rooms, fair child treatment, achievement expectations, and general satisfaction. Parents were asked to rate the items that had four categories, ranging from 1 = strongly disagree 4 = to strongly agree.

Both parents’ perceptions of teachers’ engagement and cooperation with schools were measured in the fifth year of schooling (the children’s first year of secondary school). However, there is no possibility to track whether the teachers that parents rated in the fifth year of schooling are similar to teachers that parents evaluated during the official school lockdown. Parents’ perceptions of teachers’ engagement have seven indicators: professionalism, enjoyment in learning, tedious responsibility, respect for children, the importance of teaching, teachers know the students personally, and parents can rely on the teachers. Parents’ perceptions of cooperation with school consists of two indicators: parents are welcome at school, and parents are well-informed. All indicators of both teachers’ engagement and cooperation with schools were rated using a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” (1) to “strongly agree” (4).

Parents’ Perceptions During the School Lockdown

In addition to their satisfaction with school, parents were also administered items about teachers’ technical capability, as well as their own capability in assisting their children during distance learning during the school lockdown. Both items were rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 = “very insufficient” to 4 = “very sufficient”. Parents also reported their assessment of the modifications of teaching formats implemented by the schools, as well as the delivery of learning materials organized by the schools. The construct of modifications of teaching formats was modeled as a latent variable that originally had six indicators (i.e., online coursework including interactive learning, learning software or apps, learning using reference books, learning through videos, using public-service broadcasting, and virtual learning). Due to low factor loadings, the items learning using reference books and learning through videos were excluded for further analysis. Parents were asked to rate the likelihood of each teaching format during the official school lockdown compared to prior to the pandemic (i.e., the scale ranged from 1 = “much less often” to 5 = “much more often”). To assess the delivery of learning materials, parents were asked to rate the most implemented method used by the schools in delivering learning materials to their students. To enable a more straightforward interpretation, the original scales (including 1 = “using an online platform, an online course, or a school app”; 2 = “virtual conference or video chat with teachers”; 3 = “email”; 4 = “brief messages such as WhatsApp or SMS”; 5 = “phone calls with teachers”; and 6 = “postal letters”) were recoded into 3 = “online course” (including the original scales of 1 and 2), 2 = “emails and letters” (including the original scales of 3 and 6), and 1 = “other” (the rest).

Parent-Related Factors During the School Lockdown

To account for parents’ risk of overload, other parent-related factors during the pandemic that are considered in this paper are parents’ working conditions, such as support from their employer (measured using a 4-point Likert-scale, ranging from 1 = “very bad” to 4 = “very good”) and changing the amount of work (0 = “not working at all,” 1 = “less,” 2 = “similar,” 3 = “more”). Parents were also asked to report their stress due to the school lockdown (measured using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”). Further, 6 items regarding childcare options were included in the parents’ survey. Specifically, parents were asked to rate whether the following statements were 1 = “correct” or 0 = “not correct”: I took care of my child, my partner took care of my child, older siblings helped to take care of my child, someone else helped to take care of my child, my child took care of him/herself, and emergency daycare. Based on these 6 items, a variable called childcare options was built on the assumption that the more childcare options parents had during the school lockdown, the fewer problems they needed to deal with during this particular time.

The Child’s Characteristics and School Achievement

The child’s characteristics include gender, age, special educational needs status, and school achievements. Parents were administered items about gender and special educational needs status in the second and fourth years of elementary school, respectively. Information about children’s birthdays was provided by the school, while information about the school achievement scores (grades) in German and mathematics was obtained from parents’ reports in the fifth year of schooling (i.e., the first year in the secondary school tracking system). In the same time, parents were asked to report their perceptions about the school achievement demonstrated by their children. In this regard, parents were administered 5 items as latent indicators: satisfaction with the grades obtained by their child, whether their child could obtain a good school certificate, whether their child was overstrained (recoded), whether their child could obtain a good school certificate and a good job, and whether their child was one of the best in school. All items were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree.”

School Characteristics

In this paper, school characteristics that are recognized as possibly important determinants of parents’ expectations include school track (“academic” vs. “non-academic”), state (i.e., 0 = “former West Germany” vs. 1 = “former East Germany”) and school funding (consisting of two categories: 0 = “public” and 1 = “other”). The measurement time of each construct is presented in Supplementary Appendix S3.

Statistical Analysis

Researchers working with large datasets very likely have to deal with incomplete observations. Accordingly, the methodological literature considers complete case analysis to be generally inappropriate, since inferences can be made only about a part of the target population that provides complete responses (Little and Rubin 2020). To address this specific problem, we performed multiple imputations in RStudio Version 1.3.959 (RStudio Team 2020) using the mice Package, Version 3.8.0 (van Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn 2011).

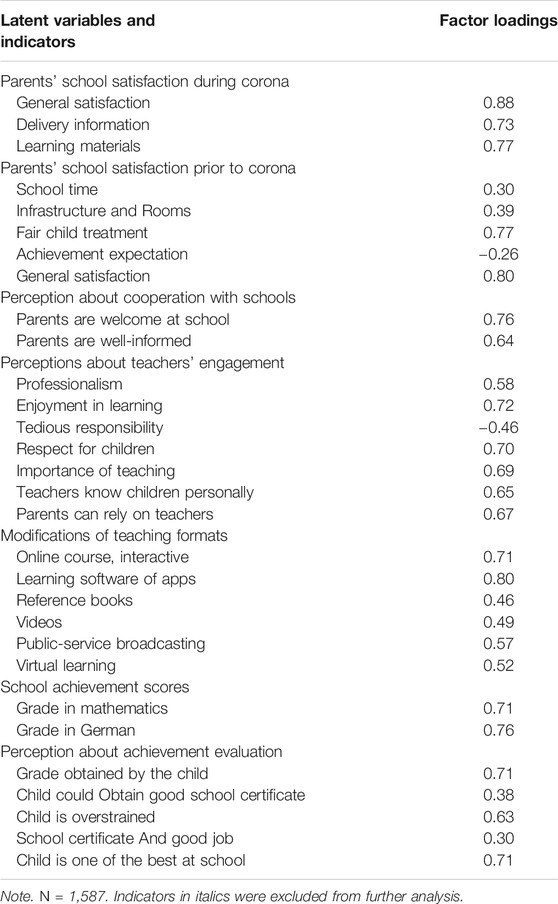

As mentioned above, the outcome variable and several predictors were modeled as latent variables. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted prior to primary analysis to check whether the indicators had suitable psychometric properties. We performed this method in RStudio, Version 1.3.959 (RStudio Team, 2020) using the lavaan Package, Version 0.6–7 (Rosseel 2012). Due to low factor loadings, several indicators were excluded from further analysis (see also Table 1).

After ensuring the quality of the latent factors, a structural equation model (SEM) was specified and examined. This analysis was also conducted in RStudio, Version 1.3.959 (RStudio Team, 2020) using the lavaan Package, Version 0.6–7 (Rosseel, 2012). Parents’ school satisfaction was regressed on all mentioned predictors. Model fit was evaluated with reference to the RMSEA, SRMR, CFI and TLI, following criteria proposed by Hu and Bentler (1999a).

Results

Descriptive Report

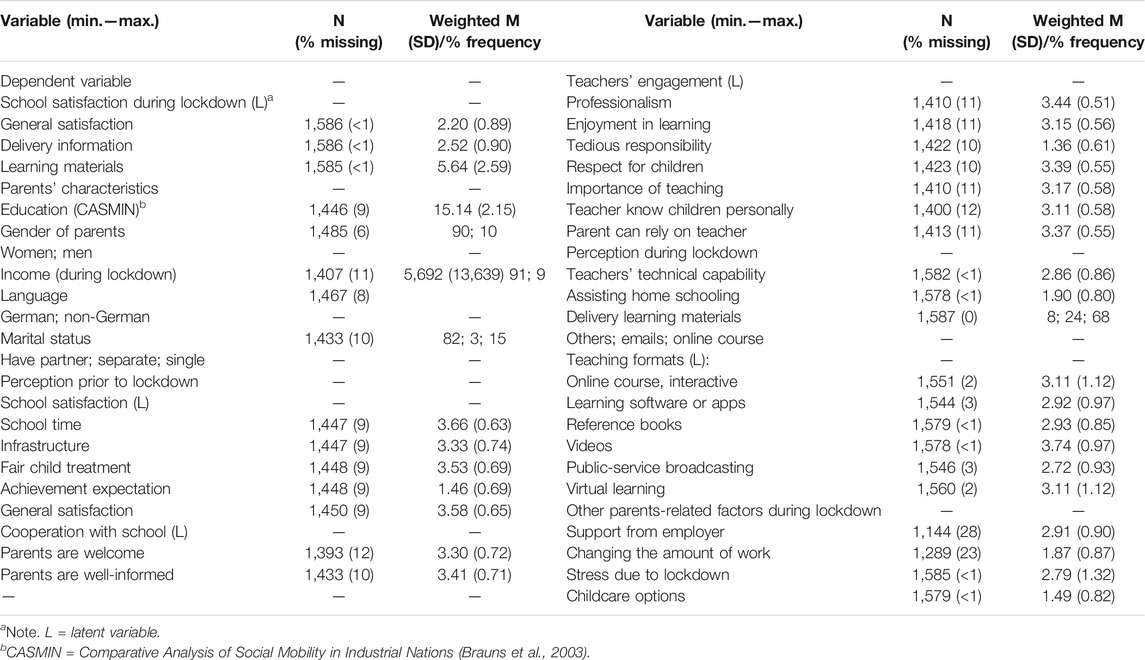

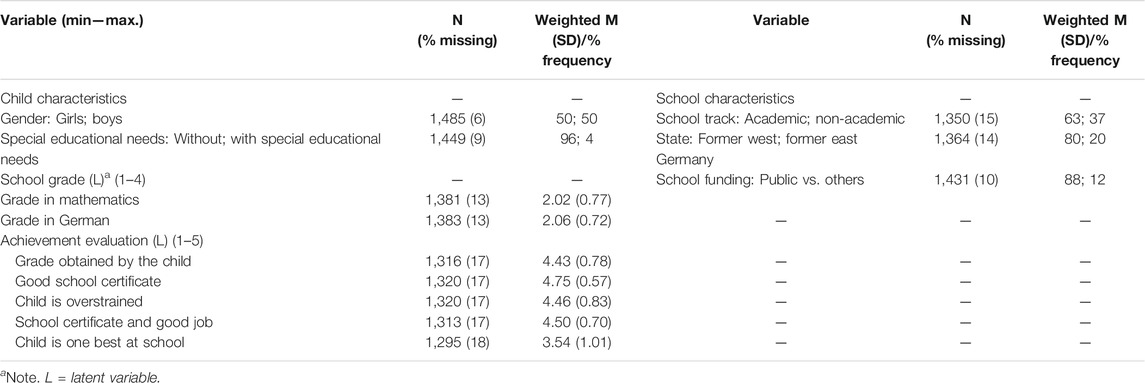

The descriptive report of all relevant variables is presented in Table 2 and Table 3. All variables except for the delivery of learning materials suffer from missing values, with the highest missing rate of 27.91% demonstrated by the construct of support from one’s employer. We performed additional analysis using weighted data to address the longitudinal selectivity issue (see Supplementary Appendix S1 and Supplementary Appendix S2 for unweighted descriptive report).

Overall, the parents’ school satisfaction during the school lockdown yielded modest results, with means of 2.21 and 2.51 (from a maximum of 4 points) for general satisfaction and the delivery of information, respectively. Moreover, satisfaction with learning materials demonstrated a median result with a mean of 5.70 out of a maximum of 10 possible obtained scores. In this regard, parents’ school satisfaction seems slightly lower than parents’ school satisfaction prior to the pandemic (with a mean score of more than 3 out of a maximum of 4 points). However, since the period between the time points of measurement of the parents’ ratings is a few years, parents rated different schools prior to the pandemic (elementary school) and during the school lockdown (secondary school). Therefore, we cannot perform specific analysis to compare these results.

Further, the relatively low proportion of non-native individuals, in addition to the relatively high means of income and educational level, indicates the sample’s longitudinal selectivity compared to the originally nationally representative sample (Würbach et al., 2006) in the non-weighted sample. That said, since additional analysis with weighted data was also conducted, concern about drop-out patterns had to be solved.

During the school lockdown, almost half of the parents rated their capability in assisting with home schooling, as well as teachers’ technical capability, as insufficient. At this time, it was also reported that the majority of learning materials were distributed online. Approximately 40% of parents said they obtained good support from their employer and worked a similar amount compared to prior to the pandemic. Perhaps more importantly, approximately one-third of parents reported having stress due to the school lockdown.

Structural Equation Model

Generally, the model fit yielded favorable results with CFI = 0.99, TLI = 0.99, SRMR = 0.06, and RMSEA = 0.04. The ratio between χ2 and degrees of freedom of 2.33 is located in an acceptable range between 5.00 and 2.00 (Wheaton et al., 1977; Tabacknick et al., 2007; see also; Hooper et al., 2008). The R square yielded a score of 47%, indicating relatively high variance explained by the model.

In the measurement model, several indicators are excluded from further analysis due to low factor loadings (see Table 1). Although (Hu and Bentler 1999b; Hu and Bentler 1998) recommended factor loadings between 0.70 and 0.80, the loadings reported by many studies in psychology range between 0.40 and 0.60 (e.g., Church and Burke 1994; Haynes et al., 2000; Ferrando and Chico 2001, see also; Beauducel and Wittmann 2005). Accordingly, Merenda (1997) recommended a lower threshold of 0.30, Hair et al. (2014) recognized factor loadings greater than 0.50 as “salient.” This view is shared by several studies that implemented a cutoff of 0.50 as the lowest acceptable factor loading (Afthanorhan and Ahmad 2013). In this study, all factor loadings higher than 0.50 were considered acceptable. Using this cutoff score, three indicators of parents’ school satisfaction prior to the pandemic (i.e., school time, infrastructure, and rooms and achievement expectations), one indicator of teachers’ engagement prior to the pandemic (i.e., tedious responsibility), two indicators of modifications of teaching formats (i.e., reference books and videos), and two indicators of perceptions of achievement evaluation (i.e., the child could obtain a good school certificate and the child could obtain a good school certificate and a good job) were excluded from further analysis. The factor loadings of all indicators of parents’ satisfaction during the pandemic, parents’ perceptions of cooperation with schools, and the achievement scores exceed the value of 0.50 and therefore are included in the model.

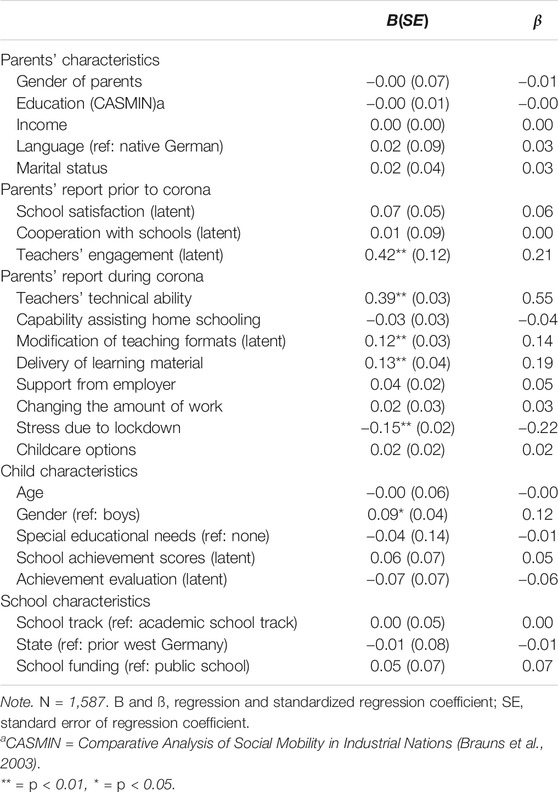

In the structural model, all parents and school characteristics yielded insignificant results (see Table 4). Parents’ perceptions about teachers prior to the school lockdown seems to have made a significant contribution to their school satisfaction during the pandemic (B = 0.42, SE = 0.14, p < 0.01), while the effect of parents’ satisfaction and perceptions about cooperation with school seem to be negligible. Again, it is worth mentioning that the school satisfaction parents reported prior to and during the school lockdown refer to different schools, while the teachers they rated prior to the school lockdown could be the same teachers they rated during the pandemic. As mentioned above, parents’ perceptions about school were measured during the fourth year of elementary school, while their views about teachers were collected during the fifth year of schooling (the first year of secondary school). Unfortunately, there is no possibility to track whether parents rated the same teachers during the school lockdown as they did in the fifth year of schooling. In this regard, there is no possibility to compare parents’ perceptions about teachers prior to and during the school lockdown. However, the general results suggest that parents are likely to be satisfied during school lockdowns when they have positive attitudes towards teachers prior to school lockdowns.

Compared to other factors, such as the characteristics of various actors (i.e., parents, children, and schools), parents’ perceptions during the pandemic seem to have made the highest contribution in explaining parents’ satisfaction during school lockdown. The effects of teachers’ technical ability (B = 0.39, SE = 0.03, p < 0.01), the modification of teaching formats (B = 0.12, SE = 0.03, p < 0.01), the delivery of learning materials (B = 0.13, SE = 0.04, p < 0.01), and stress due to school lockdown (B = −0.15, SE = 0.02, p < 0.01) are statistically meaningful, indicating that these aspects have a significant relationship with parents’ satisfaction during school lockdown. These results imply that parents who rated the teachers to have high technical ability or reported less stress during the pandemic were more likely to have higher school satisfaction than those who had other points of view. Parents’ satisfaction was also likely to be higher if they observed various modifications of teaching formats to have been done, rather than if they thought too few modifications were implemented by the school. A positive outcome is likely to be obtained if parents reported that the school delivered the learning materials via online platforms (e.g., school apps and video conferences) rather than through other means (e.g., emails, letters, telephone, short messages). Further, in accordance with the effect of teachers’ engagement prior to the school lockdown, the effect of teachers’ technical ability was relatively higher compared to other significant effects. This finding indicates that teachers play a key role in assessing parents’ school satisfaction.

Most effects of child characteristics yielded insignificant findings, with gender as the only exception. The outcomes suggest that the parents of girls were more likely to be satisfied during the school lockdown than the parents of boys (B = 0.09, SE = 0.04, p < 0.05). The effect of age, special educational needs, achievement scores, and parents’ perceptions of their children’s achievement cannot be distinguished from those obtained by chance.

Discussion

This paper aims to examine various factors, including parents, teachers’, schools’, and children’s characteristics that were likely to influence parents’ school satisfaction during the first German school lockdown in Spring 2020. Using a structural equation model, we tested five hypotheses related to a school’s ability to support distance learning (Hypothesis 1), teachers’ technical abilities (Hypothesis 2), prior parents’ perceptions of school and teachers (Hypothesis 3), parents’ resources to assist with home schooling (Hypothesis 4), and children’s prior cognitive performance and special educational needs status (Hypothesis 5)

First, our results suggest that teachers’ engagement before the school lockdown and teachers’ technical ability during the time of home schooling are the most important factors, showing the strongest effects on parents’ school satisfaction. This shows that overall, it was mainly the teachers’ or schools’ characteristics that were relevant for parents’ school satisfaction during the lockdown. Hypothesis 1, referring to the positive effect of the offer of distance learning materials and teaching formats, and Hypothesis 2, referring to teachers’ abilities, can both be confirmed. In this respect, our data showed that parents were likely to demonstrate high satisfaction if schools implemented more online-based teaching formats (e.g., interactive online courses or learning software) during the school lockdown than before; this seems to have been done by most schools in Germany (see Wolter et al., 2020). Parents also reported high satisfaction if the learning materials were delivered via an online platform compared to other methods. There are thus clear preferences towards online teaching and communication during the lockdown. One possible explanation is that other teaching methods may give parents more tasks to do than the online approach (e.g., collecting learning materials from schools means parents should plan for some extra time to go to school compared to receiving learning materials through email or online platforms). In addition, during the pandemic, online delivery has been more secure than other options. Due to the demand for an online approach, teachers’ technical capabilities and the school’s technical infrastructure become crucial (see also: Eickelmann et al., 2019; Ames et al., 2021). When teachers cannot deal with the new teaching method, parents’ satisfaction seems to be at risk (with β = 0.55, the highest standardized coefficient in the model). This result suggests that it is imperative that teachers continuously develop their technical abilities, as well as knowledge about information and technology through, for example, participation in further training and education.

Further, we assumed in Hypothesis 3 that a parent’s higher school satisfaction in the past would have a positive effect on satisfaction with school during the lockdown. The results partly confirm this expectation: While a higher perception of teachers’ engagement in the past had a positive effect (with β = 0.21, the second highest standardized coefficient), the parent’s higher school satisfaction from the past shows no effect (please note that prior school satisfaction refers to elementary instead of secondary school). As the teacher is the direct and often only contact between family and school, it is plausible that parents may primarily think about the teacher’s activities when they are asked about their satisfaction with school. Accordingly, a previous study on African-American parents showed a similar outcome: parents’ attitudes towards teachers were the strongest indicators of how they rated public schools (Thompson 2003). In addition, Friedman et al. (2007) reported that 41% of the variance in parents’ satisfaction was explained by the way schools and teachers inform parents about their children’s learning progress. Our results imply that parents’ views during the lockdown were affected by their prior knowledge about teachers. This indicates that although parents’ satisfaction is multidimensional (Friedman et al., 2007), this construct seems to be relatively stable and is not solely affected by time-specific aspects (even in a very unordinary event such as the school lockdown), such as teachers’ technical capabilities or the delivery of learning materials during the lockdown.

In Hypothesis 4, we further assumed that parents’ lower access to temporal, social, and cultural resources with relevance for home schooling had a negative effect on parents’ satisfaction with school during the lockdown. As the parents were not well-equipped with the capabilities needed for home schooling, they may have felt (or come to feel) overburdened. This can lead to lower satisfaction with school. We identified no effects for cultural resources such as “parents’ education” and “language” or for further indicators of social support and temporal resources such as “marital status,” “childcare options,” “support from one’s employer,” or “changing the amount of work.” We therefore cannot confirm Hypothesis 4. However, the effect of “stress due to lockdown” yielded a significant outcome (with a standardized coefficient of −0.22, yielding a modest result). This signals that parents’ well-being is a key element in their assessment of a school. There is a high likelihood that stressful and overwhelmed parents are indicators of poor school quality. More specifically, parental stress due to the lockdown is related to a school’s capability of performing its duties during home schooling.

Finally, we assumed in Hypothesis 5 that the child’s comprehensive need for additional learning assistance at home could more likely make the parents feel overburdened and therefore, the child’s characteristics should have an effect on parents’ satisfaction with school during the school lockdown as well. Since in the results, no characteristics of the child (apart from a positive effect of the female gender) showed any impact on parents’ school satisfaction during the lockdown, Hypothesis 5 must be denied. As parents’ satisfaction is due to their subjective perceptions (Oliver and Swan 1989; Omar et al., 2009), gender stereotypes seem to play a significant role (see also Friedman et al., 2007). In this respect, favorable attitudes towards girls over boys have been documented in past research (e.g., Zukauskiene et al., 2003; Prinzie et al., 2006).

Overall, the results suggest that various learning offers through the use of modern technology and the knowledge of how to use it are especially important for parents’ satisfaction during periods of home schooling. At the macro-level, educational policy in Germany should therefore focus more on improving framework conditions for schools to develop high standards in the use of modern technology. At the lower level, schools should invest in the support of teachers’ competencies with regard to the comprehensive use of modern technology.

Limitations

There are a few limitations to this study. While it was possible to use survey data from different measurement time points before the school lockdown, restrictions in the panel-data structure did not allow us to perform longitudinal analysis. The relevant predictors we used in this study were collected at different time points, which means that indicators collected at a time point closer to the survey may show stronger effects. Therefore, it is not possible to compare the different effect sizes directly.

Unfortunately, due to data restrictions, there was no indicator of school satisfaction with the same school before and during the lockdown available. Information on school satisfaction before the pandemic was collected during the children’s last year of elementary school, while school satisfaction during the pandemic was collected during the children’s time in secondary school. The indicators of school satisfaction before and during the lockdown therefore refer to different schools. Thus, we might underestimate the effect of former school satisfaction.

A further drawback is the lack of data on teachers’ or students’ evaluations of the school lockdown in Spring 2020. In this study, we could only use parents’ reports and perceptions of home schooling processes, teachers’ activities, and school characteristics during the lockdown. It would be interesting to examine the perspectives of other relevant actors more in the account, and to explore how they influence parents’ school satisfaction.

Future research should hence focus not only on the parents’ perspective, but also analyze students’ and teachers’ perceptions and activities. For example, a focus on factors assessing school quality during challenging times can shed light on the question of what crucial features schools need to get through a crisis well. On behalf of families, future research could focus on the satisfaction and situation of special groups who probably face higher challenges to maintain the learning progress of the students at home (e.g., families with a lower socioeconomic background or a migrant background). In addition, longitudinal analyses should analyze changes in parents’ satisfaction with school before, during, and after the school lockdown.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: https://www.neps-data.de.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

Introduction and theoretical part: TH; methodological and result part: SN; Discussion: TH and SN.

Funding

The publication of this article was funded by the Open Access Fund of the Leibniz Association.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

This paper uses data from the National Educational Panel Study (NEPS): Starting Cohort Kindergarten, Version 9.0.0, doi:10.5157/NEPS:SC2:9.0.0. From 2008 to 2013, NEPS data were collected as part of the Framework Program for the Promotion of Empirical Educational Research, funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). As of 2014, the NEPS was conducted by the Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LIfBi) at the University of Bamberg in cooperation with a nationwide network.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2021.700441/full#supplementary-material

References

Afthanorhan, W., and Ahmad, S. (2013). Modelling the Multigroup Moderator-Mediator on Motivation Among Youth in Higher Education Institution towards Volunteerism Program. Int. J. Scientific Enginieering Res. 4 (7), S. 5.

Ames, K., Harris, L. R., Dargusch, J., and Bloomfield, C. (2021). 'So You Can Make it Fast or Make it up': K-12 Teachers' Perspectives on Technology's Affordances and Constraints when Supporting Distance Education Learning. Aust. Educ. Res. 48 (2), 359–376. doi:10.1007/s13384-020-00395-8

Anders, Y., Rossbach, H.-G., Weinert, S., Ebert, S., Kuger, S., Lehrl, S., et al. (2012). Home and Preschool Learning Environments and Their Relations to the Development of Early Numeracy Skills. Early Child. Res. Q. 27 (2), 231–244. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2011.08.003

Andresen, S., Lips, A., Möller, R., Rusack, T., Schröer, W., Thomas, S., et al. (2020). Kinder, Eltern und ihre Erfahrungen während der Corona-Pandemie. Erste Ergebnisse der bundesweiten Studie KiCo. Hildesheim: Universtitätsverlag Hildesheim.

Andrew, A., Cattan, S., Costa-Dias, M., Farquharson, C., Kraftman, L., Krutikova, S., et al. (2020). Learning during the Lockdown. Real-Time Data on Children’s Experiences during home Learning. IFS Briefing Note BN288. Institute for Fiscal Studies.

Angelici, M., and Profeta, P. (2020). Smart-Working: Work Flexibility without ConstraintsConstraints (CESifo Working Paper No. 8165). Munich: Munich Society for the Promotion of Economic Research.

Anger, S., Dietrich, H., Patzina, A., Sandner, M., Lerche, A., Bernhard, S., et al. (2020). School Closings during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Findings from German High School Students. Hg. V. Iab-forum., Online verfügbar unter. Available at: https://www.iab-forum.de/en/school-closings-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-findings-from-ger.

Arciuli, J., Emerson, E., and Llewellyn, G. (2019). Adolescents' Self-Report of School Satisfaction: The Interaction between Disability and Gender. Sch. Psychol. 34 (2), 148–158. doi:10.1037/spq0000275

Arciuli, J., and Emerson, E. (2020). Type of Disability, Gender, and Age Affect School Satisfaction: Findings from the UK Millennium Cohort Study. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 90 (30), S. 870–885. doi:10.1111/bjep.12344)

Attig, M., Wolter, I., and Nusser, L. (2020), Zufriedenheit in unruhigen Zeiten. Welche Rolle die Kommunikation zwischen Eltern und Schulen während der Schulschließungen gespielt hat. Einschätzung von Eltern zur Unterstützung durch die Schule und zum Lernerfolg ihrer Kinder während des Lockdowns, 4. Bamberg: Leibniz-Institut für Bildungsverläufe e.V. (NEPS Corona & Bildung.

Bailey, D., Scarborough, A., and Hebbeler, K. (2003), Families' First Experiences with Early Intervention. National Early Intervention Longitudinal Study. NEILS Data Report. Menlo Park: SRI International.

Bassok, D., Markowitz, A. J., Player, D., and Zagardo, M. (2018). Are Parents' Ratings and Satisfaction with Preschools Related to Program Features?. AERA Open 4 (1), S. 233285841875995–17. doi:10.1177/2332858418759954

Beauducel, A., and Wittmann, W. W. (2005). Simulation Study on Fit Indexes in CFA Based on Data with Slightly Distorted Simple Structure. Struct. Equation Model. A Multidisciplinary J. 12 (1), S. 41–75. doi:10.1207/s15328007sem1201_3

Beck, D. E., Maranto, R., and Lo, W.-J. (2014). Determinants of Student and Parent Satisfaction at a Cyber Charter School. J. Educ. Res. 107 (3), S. 209–216. doi:10.1080/00220671.2013.807494

Behnke, A. O., Piercy, K. W., and Diversi, M. (2004). Educational and Occupational Aspirations of Latino Youth and Their Parents. Hispanic J. Behav. Sci. 26, S. 16–35. Online verfügbar unter. doi:10.1177/0739986303262329

Bejou, A. (2012). Customer Relationship Management, Exit-Voice-Loyalty, and Satisfaction: The Case of Public Schools. J. Relationship Marketing 11 (2), 57–71. doi:10.1080/15332667.2012.686386

Berkowitz, R., Astor, R. A., Pineda, D., DePedro, K. T., Weiss, E. L., and Benbenishty, R. (2017). Parental Involvement and Perceptions of School Climate in California. Urban Educ. 56 (3), S. 393–423. doi:10.1177/0042085916685764

Blossfeld, H.-P., Roßbach, H.-G., and Maurice, J. V. (2011). Education as a Lifelong Process. The German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS). Z. für Erziehungswissenschaft 14 (2), S. 19–34. Online verfügbar unter. doi:10.1007/s11618-011-0179-2

Bol, T. (2020). Inequality in Homeschooling during the Corona Crisis in the NetherlandsFirst Results from the LISS Panel (Working Paper). Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam.

Brauns, H., Scherer, S., and Steinmann, S. (2003). “The CASMIN Educational Classification in International Comparative Research,” in Hoffmeyer-Zlotnik und Christof Wolf (Hg.): Advances in Cross-National Comparison: A European Working Book for Demographic and Socio-Economic Variables. Editor H. P. Jürgen (Boston, MA: Springer US), S. 221–244. Online verfügbar unter. doi:10.1007/978-1-4419-9186-7_11

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1992). “Ecological Systems Theory,” in Annals of Child Development. Six Theories of Child Development: Revised Formulations and Current Issues. Editor R. Vasta (Hg (London: Jessica Kingsley, S), 187–249.

Bubb, S., and Jones, M.-A. (2020). Learning from the COVID-19 home-schooling Experience: Listening to Pupils, Parents/carers and Teachers. Improving Schools 23 (3), S. 209–222. doi:10.1177/1365480220958797

Casas, F., Bălţătescu, S., Bertran, I., González, M., and Hatos, A. (2013). School Satisfaction Among Adolescents: Testing Different Indicators for its Measurement and its Relationship with Overall Life Satisfaction and Subjective Well-Being in Romania and Spain. Soc. Indic Res. 111 (3), S. 665–681. doi:10.1007/s11205-012-0025-9

Chambers, S., and Michelson, M. R. (2020). School Satisfaction Among Low-Income Urban Parents. Urban Educ. 55 (2), S. 299–321. doi:10.1177/0042085916652190

Charbonneau, É., van Ryzin, G. G., and Gregg, G. (2012). Performance Measures and Parental Satisfaction with New York City Schools. Am. Rev. Public Adm. 42 (1), S. 54–65. doi:10.1177/0275074010397333

Christenson, S. L. (2003). The Family-School Partnership: An Opportunity to Promote the Learning Competence of All Students. Sch. Psychol. Q. 18 (4), S. 454–482. Online verfügbar unter. doi:10.1521/scpq.18.4.454.26995

Church, A. T., and Burke, P. J. (1994). Exploratory and Confirmatory Tests of the Big Five and Tellegen's Three- and Four-Dimensional Models. J. Pers Soc. Psychol. 66 (1), S. 93–114. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.66.1.93

Cryer, D., Tietze, W., and Wessels, H. (2002). Parents' Perceptions of Their Children's Child Care: a Cross-National Comparison. Early Child. Res. Q. 17 (2), S. 259–277. doi:10.1016/s0885-2006(02)00148-5

DeNeve, K. M., and Cooper, H. (1998). The Happy Personality: A Meta-Analysis of 137 Personality Traits and Subjective Well-Being. Psychol. Bull. 124 (2), 197–229. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.124.2.197

Dietrich, H., Patzina, A., and Lerche, A. (2020). Social Inequality in the Homeschooling Efforts of German High School Students during a School Closing Period. Eur. Societies 23, S348–S369. Online verfügbar unter. doi:10.1080/14616696.2020.1826556

Dubowy, M., Ebert, S., von Maurice, J., and Weinert, S. (2008). Sprachlich-kognitive Kompetenzen Beim Eintritt in Den Kindergarten. Z. für Entwicklungspsychologie Pädagogische Psychol. 40 (3), S. 124–134. doi:10.1026/0049-8637.40.3.124

Dusi, P. (2012). The Family-School Relationships in Europe. A Research Review. CEPS J. 2 (1), S. 13–33.

DW (2020). Coronavirus: What Are the Lockdown Measures across Europe?. Online verfügbar unter Available at: https://p.dw.com/p/3Zz2f, zuletzt geprüft am 04.01.2021.

Eickelmann, B., Bos, W., Gerick, J., Goldhammer, F., Schaumburg, H., Senkbeil, M., et al. (2019). ICILS 2018 #DeutschlandComputer- und informationsbezogene Kompetenzen von Schülerinnen und Schülern im zweiten internationalen Vergleich und Kompetenzen im Bereich Computational Thinking. New York: MünsterWaxmann.

Erickson, C. D., Rodriguez, M. A., Hoff, M. O., and Garcia, J. C. (1996). Parent Satisfaction and Alienation from Schools. Examination Ethnic Differences. Fresno: California State University.

Fantuzzo, J., Perry, M. A., and Childs, S. (2006). Parent Satisfaction with Educational Experiences Scale: A Multivariate Examination of Parent Satisfaction with Early Childhood Education Programs. Early Child. Res. Q. 21 (2), S. 142–152. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2006.04.002

Fend, H. (2000). Qualität und Qualitätssicherung im Bildungswesen. Wohlfahrtsstaatliche Modelle und Marktmodelle. Z. für Pädagogik (Beiheft 41), S. 55–72.

Fend, H. (2008). Schule gestalten. Systemsteuerung, Schulentwicklung und Unterrichtsqualität. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Ferrando, P. J., and Chico, E. (2001). The Construct of Sensation Seeking as Measured by Zuckerman's SSS-V and Arnett's AISS: a Structural Equation Model. Personal. Individual Differences 31 (7), S. 1121–1133. doi:10.1016/s0191-8869(00)00208-7

Fraillon, J., Ainley, J., Schulz, W., Friedman, T., and Duckworth, D. (2019). “Preparing for Life in a Digital World,” in IEA International Computer and Information Literacy Study 2018. International Report (Cham: Springer).

Friedman, B. A., Bobrowski, P. E., and Geraci, J. (2006). Parents' School Satisfaction: Ethnic Similarities and Differences. J. Educ. Admin 44 (5), 471–486. doi:10.1108/09578230610683769

Friedman, B. A., Bobrowski, P. E., and Markow, D. (2007). Predictors of Parents' Satisfaction with Their Children's School. J. Educ. Adm. 45 (No. 3), 278–288. doi:10.1108/09578230710747811

Garbe, A., Ogurlu, U., Logan, N., and Cook, P. (2020). COVID-19 and Remote Learning. Experiences of Parents with Children during the Pandemic. Am. J. Qual. Res. 4 (3), S. 45–65. doi:10.29333/ajqr/8471

Ginieri-Coccossis, M., Rotsika, V., Skevington, S., Papaevangelou, S., Malliori, M., Tomaras, V., et al. (2011). Quality of Life in Newly Diagnosed Children with Specific Learning Disabilities (SpLD) and Differences from Typically Developing Children. A Study of Child and Parent Reports. Child. Care Health Development 39 (4), S. 581–591. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2012.01369.x

Giovannella, C., Passarelli, M., and Persico, D. (2020). Measuring the Effect of the Covid-19 Pandemic on the Italian Learning Ecosystems at the Steady State. A School Teachers’ Perspective. Interact. Des. Arch. J. 45, S. 1–9.

Griffith, J. (2001). Do satisfied Employees Satisfy Customers? Sopport-Services Staff Morale and Satisfaction Among Public School Administrators, Students, and Parents. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 31 (No. 8), S. 1627–1658. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2001.tb02744.x

Griffith, J. (2000). School Climate as Group Evaluation and Group Consensus. Student and Parent Perception of the Elementary School Environment. Elem. Sch. J. 101 (No. 1), S. 35–61. doi:10.1086/499658

Griffith, J. (1997). Student and Parent Perceptions of School Social Environment: Are They Group Based?. Elem. Sch. J. 98 (2), S. 135–150. doi:10.1086/461888

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., and William, C. (2014). Multivariate Data Analysis. Harlow: Pearson Education.

Haynes, C. A., Miles, J. N. V., and Clements, K. (2000). A Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Two Models of Sensation Seeking. Personal. Individual Differences 29 (5), S. 823–839. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00235-4

Hooper, Daire., Coughlan, Joseph., and Mullen, Michael. R. (2008). Structural Equation Modelling. Guidlines for Determining Model Fit. Electron. J. Business Res. Methods 6 (1), S. 53–60.

Hu, L.-t., and Bentler, P. M. (1998). Fit Indices in Covariance Structure Modeling: Sensitivity to Underparameterized Model Misspecification. Psychol. Methods 3 (4), S. 424–453. Online verfügbar unter. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.424

Hu, L. t., and Bentler, P. M. (1999a). Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New alternativesStructural Equation Modeling. Struct. Equation Model. A Multidisciplinary J. 6 (1), S. 1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118

Hu, L. t., and Bentler, P. M. (1999b). Cutoff Criteria for Fit Indexes in Covariance Structure Analysis: Conventional Criteria versus New alternativesStructural Equation Modeling. Struct. Equation Model. A Multidisciplinary J. 6 (1), S. 1–55. Online verfügbar unter. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118

Huebner, M., Spieß, K. C., Siegel, N. A., and Wagner, G. G. (2020). Wohlbefinden von Familien in Zeiten von Corona: Eltern mit jungen Kindern am stärksten beeinträchtigt. DIW Wochenbericht Weekly Report No. 30-(31). Available at https://pure.mpg.de/rest/items/item_3245199/component/file_3245200/content

Hughes, J., and Kwok, O. M. (2007). Influence of Student-Teacher and Parent-Teacher Relationships on Lower Achieving Readers' Engagement and Achievement in the Primary Grades. J. Educ. Psychol. 99 (1), S. 39–51. Online verfügbar unter. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.99.1.39

Khajehpour, M., and Ghazvini, S. D. (2011). The Role of Parental Involvement Affect in Children's Academic Performance. Proced. - Soc. Behav. Sci. 15, S. 1204–1208. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.03.263

König, J., Jäger-Biela, D. J., and Glutsch, N. (2020). Adapting to Online Teaching during COVID-19 School Closure: Teacher Education and Teacher Competence Effects Among Early Career Teachers in Germany. EUROPEAN JOURNAL TEACHER EDUCATION 43 (4), S. 608–622. doi:10.1080/02619768.2020.1809650

Lagomarsino, F., Coppola, I., Parisi, R., and Rania, N. (2020). Care Tasks and New Routines for Italian Families during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Perspectives from Women. Ital. Sociological Rev. 10 (3S), S. 847–868.

Lancker, W. V., and Parolin, Z. (2020). COVID-19, School Closures, and Child Poverty. A Social Crisis in the Making. The Lancet Public Health 5 (5), S. 243–244. Online verfügbar unter. doi:10.1016/s2468-2667(20)30084-0

Little, R. J. A., and Rubin, D. B. (2020). Statistical Analysis with Missing Data. 3rd edition. Hoboken: Wiley Intersience (Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics).

Matland, R. E. (1995). Exit, Voice, Loyalty and Neglect in an Urban School System. Soc. Sci. Q. 76 (3), S. 506–512.

Merenda, P. F. (1997). A Guide to the Proper Use of Factor Analysis in the Conduct and Reporting of Research: Pitfalls to Avoid. Meas. Eval. Couns. Develop. 30 (3), S. 156–164. doi:10.1080/07481756.1997.12068936

Mossi, P., Ingusci, E., Tonti, M., and Salvatore, S. (2019). QUASUS. A Tool for Measuring the Parents' School Satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 10 (13), S. 1–12. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00013

Neumann, U. (2012). Zusammenarbeit mit Eltern in interkultureller Perspektive. Forschungsüberblick und das Modell der Regionalen Bildungsgemeinschaften. DDS - Die Deutsche Schule 104 (4), S. 363–373.

Okun, M. A., Braver, M. W., and Weir, R. M. (1990). Grade Level Differences in School Satisfaction. Soc. Indic Res. 22 (4), S. 419–427. doi:10.1007/bf00303835

Oliver, R. L., and Swan, J. E. (1989). Consumer Perceptions of Interpersonal Equity and Satisfaction in Transactions: A Field Survey Approach. J. Marketing 53 (2), S. 21–35. doi:10.1177/002224298905300202

Omar, N. A., Nazri, M. A., Abu, N. K., and Omar, Z. (2009). Parents' Perceived Service Quality, Satisfaction and Trust of a Child Care centre. Implication on Loyalty. Int. Rev. Business Res. Pap. 5 (5), S. 299–314.

Parczewska, T. (2020). Difficult Situations and Ways of Coping with Them in the Experiences of Parents Homeschooling Their Children during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Poland. Education 3-13, S. 1–12. doi:10.1080/03004279.2020.1812689

Patrikakou, Eva. N. (2016). “Contexts of Family–School Partnerships. A Synthesis,” in Family-School Partnerships in Context. 1. Editors Susan. M. M. Sheridan und Elizabeth, and Hg. Kim (New York, Dordrecht, London: Aufl. HeidelbergSpringer International Publishing Switzerland (Research on Family-School Pertnerships), 3, S. 109–120.

Pensiero, N., Kelly, T., and Bokhove, C. (2020): University of Southampton Research Report. Learning Inequalities during the Covid-19 Pandemic. How Families Cope with home-schooling. Online verfügbar unter. University of Southampton. doi:10.5258/SOTON/P0025

Perry, A., Charles, M., Zapparoli, B., and Weiss, J. A. (2020). School Satisfaction in Parents of Children with Severe Developmental Disabilities. J. Appl. Res. Intellect. Disabilities 33 (6), 1448–1456. doi:10.1111/jar.12772

Perry, C. L., Kelder, S., and Komro, K. (1993). “The Social World of Adolescents: Families, Peers, Schools, and the Community,” in Susan Millstein, Anne Petersen und Elena Nightingale (Hg.): Promoting the Health of Adolescence (New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press), S. 73–96.

Peters, S. (2015). “Eltern als Stakeholder von Schule. Erkenntnisse über die Sichtweise von Eltern durch die Hamburger Schulinspektion,” in Marcus Pietsch, Barbara Scholand und Klaudia Schulte (Hg.): Schulinspektion in Hamburg. Der erste Zyklus 2007 - 2013. Grundlagen, Befunde und Perspektiven (Münster: Waxmann, S), 341–365.

Prinzie, P., Onghena, P., and Hellinckx, W. (2006). A Cohort-Sequential Multivariate Latent Growth Curve Analysis of Normative CBCL Aggressive and Delinquent Problem Behavior: Associations with Harsh Discipline and Gender. Int. J. Behav. Develop. 30 (5), S. 444–459. doi:10.1177/0165025406071901

Rosseel, Yves. (2012). Lavaan. An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling and More. Version 0.5-12 (BETA). J. Stat. Softw. 48 (2), S. 1–36. Online verfügbar unterAvailable at: https://users.ugent.be/∼yrosseel/lavaan/lavaanintroduction.pdf. doi:10.18637/jss.v048.i02

RStudio Team (2020). RStudio. Integrated Development for R. RStudio. Boston: PBC. Available at: http://www.rstudio.com/(Online verfügbar unter.

Sheridan, S. M., Holmes, S. R., Smith, T. E., and Moe, A. L. (2016). “Complexities in Field-Based Partnership Research: Exemplars, Challenges, and an Agenda for the Fiel,” in Family-School Partnerships in Context. 1. Editors S. M. Sheridan und Elizabeth, and Hg. Kim (New York, Dordrecht, London: Aufl. HeidelbergSpringer International Publishing Switzerland (Research on Family-School Pertnerships), 3, S. 1–24.

Smit, F., Driessen, G., Sluiter, R., and Sleegers, P. (2007). Types of Parents and School Strategies Aimed at the Creation of Effective Partnerships. Int. J. about Parents Educ. 1 (0), S. 45–52.

Spinelli, M., Lionetti, F., Pastore, M., and Fasolo, M. (2020). Parents' Stress and Children's Psychological Problems in Families Facing the COVID-19 Outbreak in Italy. Front. Psychol. 11, S. 1–7. Online verfügbar unter. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01713

Stull, J. C. (2013). Family Socioeconomic Status, Parent Expectations, and a Child's Achievement. Res. Educ. 90 (1), S. 53–67. Online verfügbar unter. doi:10.7227/RIE.90.1.4

Suldo, S. M., R. Minch, D., and Hearon, B. V. (2015). Adolescent Life Satisfaction and Personality Characteristics: Investigating Relationships Using a Five Factor Model. J. Happiness Stud. 16 (16), S. 965–983. Online verfügbar unter. doi:10.1007/s10902-014-9544-1

Tabacknick, B. G., Fidell, L. S., and Ullman, J. B. (2007). Using Multivariate Statistics. 5th ed.. New York: Pearson. Online verfügbar unter Available at: https://www.pearsonhighered.com/assets/preface/0/1/3/4/0134790545.pdf.

Tabellini, G. (2008). The Scope of Cooperation: Values and Incentives*. Q. J. Econ. 123, 905–950. doi:10.1162/qjec.2008.123.3.905

Thompson, G. (2003). Predicting African American Parents' and Guardians' Satisfaction with Teachers and Public Schools. J. Educ. Res. 96 (5), S. 277–285. doi:10.1080/00220670309597640

Thorell, L. B., Skoglund, C., Gimenez de la Pena, A., Baeyens, D., Fuermaier, A. B. M., Groom, M. J., et al. (20212021). Parental Experiences of Homeschooling during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Differences between Seven European Countries and between Children with and without Mental Health Conditions. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry, 1–13. doi:10.1007/s00787-020-01706-1

Tuck, K. D. (1995). Parent Satisfaction and Information. A Customer Satisfaction Survey. Washington, DC: District of Columbia public schools.

Ulrey, G. L., Alexander, K., Bender, B., and Gillis, H. (1982). Effects of Length of School Day on Kindergarten School Performance and Parent Satisfaction. Psychol. Schs. 19 (2), S. 238–242. doi:10.1002/1520-6807(198204)19:2<238::aid-pits2310190217>3.0.co;2-z

van Buuren, S., and Groothuis-Oudshoorn, C. G. (2011). Mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. J. Stat. Softw. 45 (3), 1–67. doi:10.18637/jss.v045.i03

van Ryzin, G. G., Muzzio, D., Immerwahr, S., and Immerwahr, Stephen. (2004). Explaining the Race gap in Satisfaction with Urban Services. Urban Aff. Rev. 39 (5), S. 613–632. doi:10.1177/1078087404264218

Verma, G. (2020). COVID-19 and Teaching. Perception of School Teachers on Usage of Online Teaching Tools. Mukt Shabd J. 9 (6), S. 2492–2503.