- 1Department of Statistics, Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

- 2Centre of Excellence in Mathematical and Statistical Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa

Much has been written on the implementation of Twitter in the higher education environment, but few essays exist on the role that this social media space could potentially fulfill in the postgraduate supervision process. This role is reflected on in this paper. Key literature is reviewed that discusses the essential components of doctorateness: enculturation, communities of practice, and research identity for both student and supervisor that this role could serve. The position of this role in Africa is briefly highlighted. We postulate that Twitter may indeed serve as a valuable and meaningful platform that serves the intersection between the four components of doctorateness.

1 Introduction

In this modern day era, scientists have grown accustomed to the rapid information sharing age within academia. Be it fast turnaround times of manuscript reviews via the internet, or collaboration with other scientists around the world, the speed at which information is generated and accrued is unprecedented. A major role player in this information-driven era is social media, which connects people in the virtual realm on a regular basis; examples include Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter. In a professional sense, LinkedIn has provided a social media interface for a corporate (and somewhat academic) environment; and ResearchGate and Academia.edu has created social networks designed specifically for scientists and members of academia.

Ovadia (2014) mentions how social networking sites often seem pointless to academics. However, in recent years there as been an upsurge in the use of these platforms by academics to not only uplift and discuss their research interests, but also to promote their science to a wider, public audience. Bik and Goldstein (2013) discusses the use of social media for scientists in a science communication setting; and specifically mentions benefits for scientists to invest more time in the virtual social world. The authors also discuss Twitter in particular, which is a social media tool of particular interest in this paper. Twitter acts as a “microblogging” environment and creates a way of communication that is, to a large extent, free from costs and geographical restriction [Fernández-Ferrer and Cano (2016), Malik et al. (2019)]. Owens (2014) examines the rise and growing interest of academic social networking platforms and discusses ways in which these platforms are shaping careers of young researchers, be it PhD scholars or emerging researchers, and Mehta and Flickinger (2014) mentions the value and attraction of social media to academia and discusses some advantages, with specific reference to Twitter as platform for establishing a journal club within their discipline. Twitter in the classroom at the under- and postgraduate levels have also been of interest in recent years with extraordinary positive results and sentiment regarding its use, see Bista (2015), Chawinga (2017) for example. The interest in Twitter as a useful social media tool within the academic sphere is therefor understandable and intriguing: little reflection has been presented that philosophizes on the meaningful contribution that Twitter may add in specifically the postgraduate training process. There is growing evidence of academic libraries around the world that utilizes Twitter extensively in order to access, promote, and disseminate scientific work (Kim et al., 2012). This study indicated that academic libraries’ tweets were of interest to intermediaries and key role players in the academic field such as university organizations, local public organizations, and information professions. Also within this information-theoretic focus, it’s meaningful to note many journals are reporting the “Altmetric”—a measure of the social media reach specifically of published papers [see Publons, for example, and Tonia et al. (2020)]. The possibility of Twitter being implemented as a more serious contender as an academic social network space, is therefore likely and potentially exciting [see also Ngai et al. (2015)], with particular emphasis by McPherson et al. (2015) on Twitter as an informal learning space. It is essential to consider how this space might complement or distract from the essence of (digital) doctorateness.

European University Association, 2010 provided a framework, known as the Salzburg Principles, which provides guidance in terms of seven principles to facilitate innovative doctoral training. Those which aligns to the notion of information sharing and the speed of knowledge, includes Nr. 1: Research Excellence, Nr. 4; Exposure to industry and other relevant employment sectors, and Nr. 5: International Networking. The notion of a researcher identity to be honed with postgraduate students (as well as the continued redefined researcher identity of supervisors themselves) are also principal components within the postgraduate training process. With this paper, our aim is three-fold:

1. To report a brief review of essential literature that has described the reach and effect of Twitter within the sphere of academia,

2. To juxtapose benefits of Bik and Goldstein (2013), Ovadia (2014), and Bhardwaj (2017) (as well as discussing disadvantages) to that discussed by other literature [such as Donelan (2016)] regarding the implementation and use of Twitter in the training process via reflective and diffractive type methodology,

3. To illustrate the potential effect of Twitter in this specific academic relationship supports and complements the above principles of the Salzburg Principles; together with some reflections on the construction of researcher identity.

We also add context of the viability of Twitter specifically in the African context. This is purposefully done to stimulate further future discussion on how scholars in Africa, may use this platform as valuable tool to enhance and enrich communication with peers from around the globe. To quote Tomaselli and Sundar (2011): “No longer is Twitter a western of frivolous phenomenon,” regarding the large number of active African Twitter users. Our speculative research methodology, coupled with a reflective and diffractive approach, assesses the potential added value of Twitter to crucial communicative relationship between doctoral1 students and supervisors during the postgraduate training process, students themselves, and the wider academic community—with brief comments on its potential added value in Africa.

This reflective paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, an overview of some literature is given which relates to four key areas: online communities as “physical communities” i.e. communities of practice (CoPs), utilizing Twitter as a hub for the sharing of information and knowledge, the notion of digital doctorateness, and other current social media spaces within academia and the uses thereof. In Section 3, an argument that Twitter may act as beneficial research platform in the training process is emphasized; this relies on key ideas such as participation of academics, participation from students, and the potential of Twitter as this HUB also within an African context. Section 4 discusses some advantages and disadvantages of this social media learning platform, and the paper closes with conclusions and further research opportunities in Section 5.

2 A Snapshot of Literature

An overview on some literature pertaining to communities of scholars within the online world, as well as communities of practice together with an overview on literature pertaining to social media spaces within academia is presented. It is of importance to note the contribution of Gray and Crosta (2019) and Sugimoto et al. (2017) in this regard early on; with both of these providing refreshing perspectives and literature overviews of the doctoral journey within the online environment.

2.1 (Online) Communities of Practice and Digital Doctorateness

There has been a variety of work that has enriched the literature not only on doctorateness and digital doctorateness, but also on CoPs and also virtual communities of practice.

Many authors have researched the ways in which we understand and contribute to online CoPs [see Ardichvili et al. (2003), Ardichvili et al. (2006), Ardichvili (2008), Sharratt and Usoro (2003), Correia et al. (2009)]. A CoP has been described as “groups of people informally bound together by shared expertise and passion for a joint enterprise”. Sharratt and Usoro (2003) mentions in particular that these communities of practice are self-organizing: the lifespan of the community is determined by its members and is vitally dependent on the intrinsic value that membership brings. The same author also describes CoPs as “effective loci for the creation and sharing of knowledge”. Ardichvili (2008) in particular mentions virtual CoPs and motivators, barriers, and enablers within CoPs, how they regulate as well as define themselves by the membership contingent that each CoP has. Correia et al. (2009) also discusses refreshing thoughts in the context of virtual CoPs.

Other contributions relating to digital learning in higher education as well as the virtual space of academia is also worth noting. The concept of digital learning in higher education is also intrinsically linked into the bigger picture of “learning” and contributing at the doctoral level, thereby assisting the definition of “digital doctorateness”. The contribution of Yazdani and Shokooh (2018) is essential to note regarding the description and definition of doctorateness, and Donelan (2016) describes the use of social media as a professional development environment within the academic sense; and particularly reports that of those academics who do rely on social media within their academic realm who were included in the study felt that they had experienced positive contribution within their work environment as a result. Menendez et al. (2012), Balakrishnan (2014) discusses key points relating to the use of social networks to enhance learning at the tertiary level in an education sense, but also in a research and “classical” academic sense [see also Johnson and Yang (2009), Liu (2010), Salmon et al. (2015), Katrimpouza et al. (2019)].

Several contributions in literature focus on concepts of doctoral training, which includes a sense of belonging (enculturation) which directly feeds into the idea of a researcher identity that must be honed [see Lee (2008)] and also viewing doctorateness as an evolving field in the current era [see Lee (2018)]. Wellington (2013) makes valuable comments to the doctorateness aspect from both supervisors and postgraduate students’ perception to phrase the evolving nature of doctorateness. Keefer (2015), Trafford and Leshem (2009) reflects on how supervisors may capitalise on certain components within doctorateness which could act as thresholds for students to overcome and succeed; thereby addressing and complementing doctorateness even further.

Thus, the literature provides a backdrop against which the argument of digital doctorateness, as well as CoPs is not “new”; in fact, it is a practice that is encouraged and unavoidable in the era that we operate in—in- and outside of academia. Social media spaces as additions to digital doctorateness and in context of meaningful CoPs within the academic sphere is not a new concept within itself, and is discussed in the next section.

2.2 Other Common Social Media Spaces Within Academia

Bik and Goldstein (2013) describes social media spaces which scientists can consider; but does not cover current social media spaces particularly earmarked for academics. They mention in particular that seasoned internet users claim that online tools can increase their productivity and lead to improved efficiency regarding reaching personal research goals. Ovadia (2014) mentions that specialized academic social networking sites are gaining popularity within a range of disciplines across the world, making particular mention of ResearchGate and Academia.edu. Distinguishing between different online academic sites needs to be taken into account [see Ovadia (2014)]. It is valuable to note that there is a difference between social networking sites and citation managers such as Mendeley and Zotero which also has social options—but is not a networking environment; these sites are not as engaging as social networking environments.

A comparative analysis of ResearchGate, Academia.edu, Mendeley, and Zotero is undertaken by Bhardwaj (2017); and concludes that none of these popular academic social media spaces can be considered as “excellent”—pointing out inconsistent application of metrics and less than desirable output features. Gruzd and Goertzen (2013) studies the potential significance of social media within an academic environment; particularly in the ways in which social scientists are adopting the online reality as part of their research conduct on a day-to-day basis. Nández and Borrego (2013) argues that social media spaces within academia rely on these platforms to follow other researcher’s activities, get in touch with these researchers, and also to share research results to a broader audience. Some limits and potentials of social media spaces within academia is discussed by Goodband et al. (2012) within a mathematics discipline context; commenting on the social cohesion impact these spaces have on learning by specifically using Facebook. Manca and Ranieri (2016) discusses a similar topic by investigating a larger academic audience.

It is clear that there is room within academia for social media spaces to facilitate communication, and to a further extent, learning. However, for the postgraduate training process, the social media spaces discussed in this section does not present appropriate for facilitating connections and conversation, and sharing opinions on research within the context of postgraduate training. It is evident that there is a lack of literature that considers Twitter as a social media space to complement the postgraduate training process, and some advantages and challenges of Twitter being proposed as suitable social media space in this regard, is discussed in Section 4.

3 Twitter as Complementary Research Platform in the Postgraduate Training Process

Here, a contemplative research discussion is presented on how Twitter could function as a supplementary research platform as academic social media space in the postgraduate training process. Such a platform can be seen as breaking away from the dyadic (or apprentice) supervision model [see Frick (2019)]; however, we argue that as a complementary model this breakaway is not regarded as fatal to doctoral supervision success. In fact, it is argued that it gives rise to potential upliftment and further support within the supervision process [see Brodin and Frick (2011) which comments on encouraging critical creativity in the doctoral process].

Dowling and Wilson (2017) describes some key elements of doctoral education which may be achieved online or digitally; these include research training, project management, information management, emotional support, and the development of a researcher identity. Some parallels and reflections on Twitter as worthwhile academic social media space to address and complement these elements and principles are described. This section comprises of three sub-themes: the participation and engagement of supervisors on the Twitter platform, Twitter as a supportive learning environment for postgraduate students, and a discussion on the reach and suitability of Twitter as a potential supportive platform within the postgraduate supervisory paradigm in an African context.

3.1 Engagement of Supervisors on the Twitter Platform

We describe here reflections on if, and how, supervisors may engage on the Twitter platform. These reflections complement the advancement of not only the identified Salzburg principles of interest in Section 1, but also in continuously honing a research identity as a doctoral supervisor. A major aspect for this process is to acknowledge that the creation of a research identity within the postgraduate training process is not exclusively for only the postgraduate student (Lee, 2018). In the authors’ personal experience, this supervisory process is essential to their own continuous researcher development, and therefore, platforms which supports and facilitates this development is of sustained importance—perhaps even more so for young emerging scholars in supervisory positions.

Twitter is arguably also a platform to facilitate Socratic questioning within the postgraduate training process (Frick et al., 2010). The nature of tweets provide to not only ask your own questions (from supervisors as well as postgraduate students) to experts who could be geographically removed from you; but also follow the questions and answers that other students, scientists, and academics share with each other on the platform. Adding onto this, the platform creates the opportunity for the supervisor to engage with their postgraduate students outside of the office and formal supervisory spaces, and also observe and contribute to their communication skills, writing planning, dealing with the types of feedback students may receive. We postulate that this phenomenon can be considered a form, version, or subset, of the cohort supervision model.

The use of digital components within the modern doctorate is not new to the literature. Lee (2018) comments on supervisors contributing to the enculturation of postgraduate students by engaging in ways previously unconsidered with the modern day cohort of students; where Gatfield (2005) describes online tools in a similar sense: therefore we argue that Twitter be considered as a method (or at least, a reliable support structure) for (digital) doctorateness. To promote an inclusive supervision style of supervisors, Twitter may be used as a tool to “bridge” unknown and often lonely aspects of the supervision process for supervisors; and to stimulate conversation and further stimulate Socratic questioning in particular [see Gatfield (2005)]. It remains valuable, and almost should be imperative, for supervisors to commit to renewing, updating, and merging their supervisory strategies to modernize their student outputs to that of global trends within their disciplines. In this way, the Research Excellence principle of European University Association et al. (2010) is supported.

It is valuable to again rely on the contribution of Bik and Goldstein (2013) by giving advice for new users within the social media (in particular, Twitter) sphere. This advice may be valuable to supervisors of postgraduate students who might not be familiar to:

1. Explore online guides to social media;

2. Establish and maintain a professional website;

3. Locate pertinent online conversations;

4. Navigate the deluge of online information;

It is essential to reflect on how Twitter can be used to break down barriers relating to power relations within the postgraduate training process. “Diluting” the stress and sometimes overwhelming sense of obligation that one supervisor may feel (especially if the supervisor is an emerging scholar), may cause an improvement in often-described “strenuous” power imbalances in the postgraduate training process. There are a variety of potential collaborators, or like-minded scientists whose wealth of knowledge is available in a conversational and social manner, which can address this otherwise perceived strenuous environment.

3.2 Engagement of Postgraduate Students on the Twitter Platform

The focus in this section is on the postgraduate student as key role player on utilizing Twitter within their supervised postgraduate experience. As before, this digital exposure draws parallels in addressing both the Salzburg principles and also constructing and honing a research identity—but, from the postgraduate student’s perspective.

Lee (2008) comments on concepts of doctoral education; one of this being the idea of enculturation from the postgraduate student’s perspective. The environment that Twitter provides—a network and academic online community of experts, other postgraduate scholars, scientists, and academics allows a sense of enculturation to manifest for such a student. The student becomes part of an academic discipline community; and also contributes to the well rounded emancipation of the student during the course and even after their studies—where the student becomes an independent thinker, questioning and engaging with the community. The principle of International networking as well as exposure to industry and other sectors of European University Association et al. (2010) is of direct interest here.

Of course, having your supervisor more actively participating in your research conversation in short tweets, could lead to improved supervisor qualities [see also Frick (2019)]. A supervisor who is also actively “in the game” with the student in terms of the academic online community, could lead to a local (at the home university/department) intellectually stimulating and connected research community in which the postgraduate student would be more likely to flourish.

Finally, it is known that postgraduate students and supervisors enter the supervisory relationship with unequal knowledge (Frick, 2019). This does not necessarily imply that a student has lesser net knowledge: the unequal knowledge regarding the academic content is temporary at best, but the supervisor, even having experience, also has the same net knowledge about the outcome of the degree content at any point in time—this is how novel the content should be. The comfort and ease of navigating social media, in this case academic social media spaces, are likely to be more in the hands of the student, than the supervisor. In this regard, “unequal knowledge” becomes a very broad term with both supervisors and postgraduate students having advantages and challenges that should be honed and sharpened throughout the process—which Twitter may be able to ease.

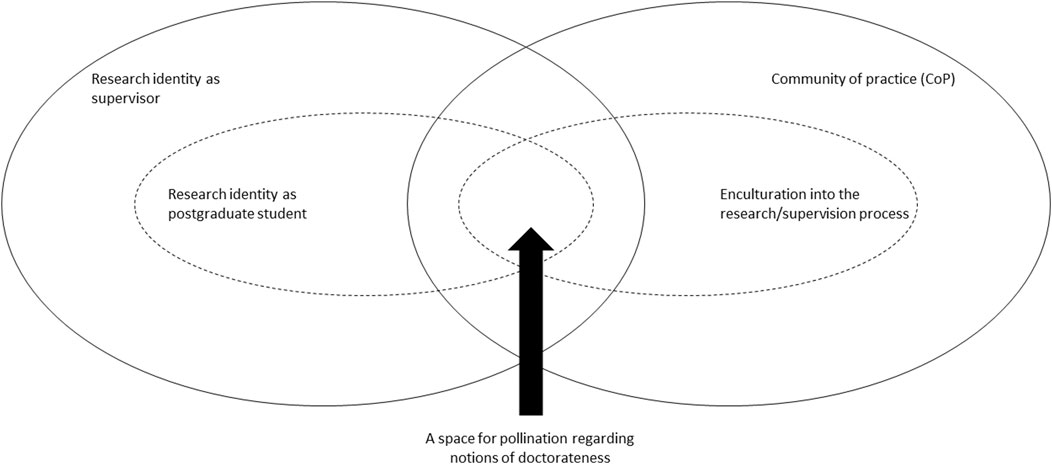

Figure 1 [inspired by Chawinga (2017)] depicts where a platform such as Twitter would lie when juxtaposed together with the research identity of the supervisor (which, for arguments’ sake encapsulates that of postgraduate student), and cross-pollinates with the notion of a (online) CoP which would facilitate the enculturation into the supervision (and thus, research) process. This intersection is identified as a space where Twitter could facilitate this cross-contamination of these essential ingredients of (digital) doctorateness.

3.3 The Reach of Twitter Within an African Context

Africa as a knowledge entity presents a variety of challenges as well as its own solutions, within as well as beyond the education realm. Ayentimi and Burgess (2019) mentions in particular that Africa “remains a key region on the global map with significant natural resource endowment, including human capital compared to any region of the world”. Mungai (2016) describes some interesting trends and insights into the way that Africa tweets—the number one insight mentioned is that Twitter is indeed a growing force on the continent. This is further emphasized by Tomaselli and Sundar (2011), mentioning that it is foolish to miss an opportunity of reaching Africans via Twitter. Within the supervisory process, models of training in Africa has started to realign itself towards the continent’s need during the past few years (Cross and Backhouse, 2014). The authors comment and discuss innovative approaches within the African context on the doctoral journey; but make little to no mention regarding online considerations.

This is arguably a valid and valuable point of reflection. Mungai (2016) argues that major cities in Africa are becoming “smart” cities (such as Nairobi, Lagos, Accra, etc.) thereby creating a platform for online presences around universities in these cities as well the fourth industrial revolution is also inevitably shifting the education paradigm within Africa as well. Based on the information and communication technology (ICT) investment and boom across Africa [see also Ayentimi and Burgess (2019)], access to platform such as Twitter is viable. Thus, this platform is within reach for Africa, and could act as an assistive component that complements other lacking resources which many African universities still may have. These include lack of access to libraries and research material (contacting and conversing with authors via Twitter could provide more direct access without infringing publishers’ copyright), as well as potentially creating breeding grounds for international collaboration and co-supervision in the training process [complementing the partnership opportunity model that Cross and Backhouse (2014) proposes]. In this way, a researcher identity can be honed with the support of international academics and scientists; together with meeting principles Nr. 4 and 5 of European University Association et al. (2010).

4 Advantages and Challenges of Twitter as Academic Social Media Space

Bik and Goldstein (2013), Mehta and Flickinger (2014), Owens (2014) mentions several advantages as well as challenges of engaging with academic content- and fellows on Twitter. Klar et al. (2020) provides particular commentary on how social media can combat inequalities in the dissemination of research. These identified advantages and challenges from literature are amalgamated here with some reflection by the author, and additional advantages and challenges by the author are also contributed.

Twitter remains a tool of the internet; which has a variety of advantages that academics and students alike would be able to reap benefits from in the postgraduate training process:

1. Low time investment, short posts.

Tweets offers short posts of up to 280 characters which makes it ideal for ideas and thoughts, and composing and sending a tweet takes comparatively little time.

2. Ability to rapidly join in on online conversations.

Due to the open access nature of Twitter, it is easy to follow and join in on online conversations that an academic, or group of academics (or even a journal) may be having.

3. Very current source for topical conversations and sharing journal articles.

Academics on Twitter often share either the links to the published versions of their manuscripts; but often also to their institutional repository where the final pre-print manuscript is held. The free access to these pre-prints are usually not infringing on copyright for accepted manuscript at journals [see Holton et al. (2014)].

4. Advertise their thoughts and scientific opinions.

Due to the public and open nature of the platform, many scientists weigh in on conversations outside of their research expertise area (such as climate change, public policy, etc), which in turn could stimulate further discussion on addressing these topics within a research paradigm.

5. Posting updates with regards to meetings and conferences and circulate information regarding professional opportunities and upcoming events.

The use of hashtags (#) to categorize certain topics, updates, and scientific meetings make it easy to find information relating to gatherings of academics at conferences or other scientific meetings across the world; and even if you are not attending, Twitter makes it accessible for people around the world to follow and join in on scientific conversations at these meetings.

6. Twitter is cost-free.

There is no cost to Twitter, and it is easily available via the app for any smartphone operating system as well as the web interface.

7. Creates a digital paper trail for your shared thoughts.

Users can easily go back to their tweet history as well as tweets from other users which they liked; these are also conveniently time-stamped to assist with the digital paper trail of shared thoughts.

8. Creating and sharing a sense of researcher identity within a community.

This is one of the most important reflections in the advantages discussion of this platform.

9. Virtually no restriction on a user’s geographical location.

Scientists from all corners of the globe can access twitter, with some exceptions where government agencies has outlawed the use of this platform [see Kumari (2021) for a recent discussion on this matter].

Challenges of the platform include:

1. Posts are quickly buried under new content.

Due to the speed and ease of generating tweets, users run the risk of their tweets not always being observed or linger for enough time for more users to engage with them.

2. Twitter does not have search functionality in its archive.

Without this functionality, it makes it challenging for the user to find and filter through search results to find tweet-specific information.

3. Gaining followers and a Twitter persona is a slow process.

With the wealth of accounts, establishing a Twitter persona which communicates effectively and which is considered as reliable and worthwhile to engage with, takes time and patience.

4. The platform is open-access, public, and has its own set of terms and conditions.

As Twitter is an open-access and public “forum” with little to no moderation from the site itself, users run the risk of being exposed to cyber-bullying. Users are cautioned in sharing too much detail, at least in first encounters with potential collaborators or other scientists, as these initial engagements may compromise the integrity and exclusivity of research ideas and methods. It is also valuable to note that body language, as in a mobile text message, is not encoded, and so any harsher forms of critique should always be read with caution and a “pinch of salt” [see also Budge et al. (2016)].

5. The internet is forever.

It is prudent to note that “messy” interactions (sic, see Budge et al. (2016)) may be inevitable on the platform; and that by merely deleting a tweet might not render the sender innocent further—Twitter archiving, as per their terms and conditions, retains all tweets which may be found by strong search engines. Thus, users should also use caution engaging in “Twitter wars” with other academics; as this could also potentially damage their research reputations [see also Woodley and Silvestri (2014)].

6. The international academic Twitter community is most likely to tweet and engage on this platform in English.

Although this remains a challenge in the classic sense, Mungai (2016) reports that English is indeed by far the most dominant language on Twitter across Africa. Therefore, postgraduate students and supervisors can be aided in their writing process as well as the language of engagement on the platform remains as neutral as possible [see also Boughey and McKenna (2019)].

7. It is easy to get distracted with nonacademic content on a site that is designed for nonacademic audiences.

Many celebrities in different spheres of life all have active Twitter accounts, as well as news outlets and entertainment agencies. It might be challenging to engage only with meaningful academic content. We suggest interested practitioners (supervisors and postgraduate students) to keep separate profiles an academic (professional) and a personal profile to stratify the interests of the user.

It remains up to the users to utilize this platform within the training process. However, the advantages of Twitter within the academic social media realm are beneficial; if users are continuously mindful and aware of the challenges that this (and arguably, any) social media environment in this era presents its users with.

5 Final Thoughts and Some Future Directions

We have reflected on Twitter as a potential suitable academic social media space in which supervisors and their postgraduate students can engage in to complement the training process and relationship. The role of Twitter in this process was reflected on from different viewpoints, and advantages and challenges were amalgamated from across literature and supplemented by the authors’ own experiences and opinion. Our presented argument is strongly influenced by the proposed supplemental nature of this platform to the Socratic questioning method, and the strong social interaction that students and supervisors can tap into on a global scale for discipline-specific, but also interdisciplinary conversations, collaborations, and consultations. We postulate that the advantages outweigh the challenges, and in this case, particularly supports the use of social media—and Twitter in particular—as complement to the postgraduate supervision process.

As a final thought, it is worth quoting Bik and Goldstein (2013): “The increasing use of online resources may eventually transform and expand the culture of science as a whole.” It is the opinion of this paper; that by utilizing Twitter as an active learning space in the postgraduate training habitat could be of immense benefit to the attitude, sharing, experience, and meaning within the culture of science (in particular the postgraduate training process, and potentially beyond) across any range of disciplines.

Bhardwaj (2017) undertook a comparative analysis of social media sites which were particularly designed with an academic audience in mind; but did not include Twitter as an academic social media space in this comparison. This comparison could add value to the literature to evaluate Twitter’s reach and platform in an academic sense; and is a valuable avenue for potential future research. DeAndrea et al. (2012) investigated the use of social media as method to assist and adjust students’ transition from high school to university studies. This creates a possible consideration for research on transition from either masters to doctoral studies and students’ perception thereof, or for international students to a new university and their adjustment—via the use of social media spaces as adjustment method and tool. Although Prescott (2019) focuses on rural universities within a first world setting in the United States, a study on similar predicaments predominantly in terms of funding and the postgraduate scholar’s experience in rural universities within an African setting, would also be of value within the literature.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

This work forms part of the grant RDP296/2021 based at the University of Pretoria, South Africa. The assistance of the Department of Statistics at the University of Pretoria is acknowledged.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The author wish to acknowledge the support of the Department of Statistics at the University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa, for financial support for this manuscript. This works forms part of the author's involvement at DIES/CREST at 355 Stellenbosch University, South Africa. Furthermore, the author wishes to acknowledge the unwavering support and essential role that the Centre of Excellence in Mathematical and Statistical Science, based at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, is playing within the discipline of statistics in the South African academic landscape. The thoughtful and constructive comments of two reviewers and the editor is hugely appreciated.

Footnotes

1In this paper, postgraduate student(s) is used with particular reference to doctoral students; however, the arguments and reflections contained here may be considered for other postgraduate students as well (honours/masters etc.) depending on the context of postgraduate study.

References

Ardichvili, A. (2008). Learning and Knowledge Sharing in Virtual Communities of Practice: Motivators, Barriers, and Enablers. Adv. Developing Hum. Resour. 10, 541–554. doi:10.1177/1523422308319536

Ardichvili, A., Maurer, M., Li, W., Wentling, T., and Stuedemann, R. (2006). Cultural Influences on Knowledge Sharing through Online Communities of Practice. J. Knowledge Manage. 10, 94–107. doi:10.1108/13673270610650139

Ardichvili, A., Page, V., and Wentling, T. (2003). Motivation and Barriers to Participation in Virtual Knowledge‐sharing Communities of Practice. J. Knowledge Manage. 7, 64–77. doi:10.1108/13673270310463626

Ayentimi, D. T., and Burgess, J. (2019). Is the Fourth Industrial Revolution Relevant to Sub-sahara Africa?. Tech. Anal. Strateg. Manage. 31, 641–652. doi:10.1080/09537325.2018.1542129

Balakrishnan, V. (2014). Using Social Networks to Enhance Teaching and Learning Experiences in Higher Learning Institutions. Innov. Edu. Teach. Int. 51, 595–606. doi:10.1080/14703297.2013.863735

Bhardwaj, R. K. (2017). Academic Social Networking Sites. Ils 118, 298–316. doi:10.1108/ils-03-2017-0012

Bik, H. M., and Goldstein, M. C. (2013). An Introduction to Social media for Scientists. Plos Biol. 11, e1001535. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001535

Bista, K. (2015). Is Twitter a Pedagogical Tool in Higher Education? Perspectives of Education Graduate Students. JoSoTL 15, 83–102. doi:10.14434/josotl.v15i2.12825

Boughey, C., and McKenna, S. (2019). Roles and Responsibilities of the Supervisor and studentCourse Material of Module 3 of the DIES/CREST Training Course for Supervisors of Doctoral Candidates at African Universities. Stellenbosch, South Africa: Stellenbosch University.

Brodin, E. M., and Frick, L. (2011). Conceptualizing and Encouraging Critical Creativity in Doctoral Education. Intl Jnl Res. Dev 2, 133–151. doi:10.1108/17597511111212727

Budge, K., Lemon, N., and McPherson, M. (2016). Academics Who Tweet: “Messy” Identities in Academia. J. Appl. Res. Higher Edu. 8, 210–221. doi:10.1108/jarhe-11-2014-0114

Chawinga, W. D. (2017). Taking Social media to a university Classroom: Teaching and Learning Using Twitter and Blogs. Int. J. Educ. Tech. Higher Edu. 14, 1–19. doi:10.1186/s41239-017-0041-6

Correia, A. M. R., Paulos, A., and Mesquita, A. (2009). Virtual Communities of Practice: Investigating Motivations and Constraints in the Processes of Knowledge Creation and Transfer. Electron. J. Knowledge Manage. 8, 11–20.

Cross, M., and Backhouse, J. (2014). Evaluating Doctoral Programmes in Africa: Context and Practices. High Educ. Pol. 27, 155–174. doi:10.1057/hep.2014.1

DeAndrea, D. C., Ellison, N. B., LaRose, R., Steinfield, C., and Fiore, A. (2012). Serious Social media: On the Use of Social media for Improving Students' Adjustment to College. Internet Higher Edu. 15, 15–23. doi:10.1016/j.iheduc.2011.05.009

Donelan, H. (2016). Social media for Professional Development and Networking Opportunities in Academia. J. Further Higher Edu. 40, 706–729. doi:10.1080/0309877x.2015.1014321

Dowling, R., and Wilson, M. (2017). Digital Doctorates? an Exploratory Study of PhD Candidates' Use of Online Tools. Innov. Edu. Teach. Int. 54, 76–86. doi:10.1080/14703297.2015.1058720

European University Association (2010). Salzburg II Recommendations-European Universities’ Achievements since 2005 in Implementing the Salzburg Principles, 25. 2016, Salzburg, Austria: European University Association .

Fernández-Ferrer, M., and Cano, E. (2016). The Influence of the Internet for Pedagogical Innovation: Using Twitter to Promote Online Collaborative Learnings. Int. J. Educ. Tech. Higher Edu. 13, 1–15. doi:10.1186/s41239-016-0021-2

Frick, L., Albertyn, R., and Rutgers, L. (2010). The Socratic Method: Adult Education Theories. Acta Academica 1, 75–102.

Frick, L. (2019). Supervisory Models and Styles. Course Material of Module 4 of the DIES/CREST Training Course for Supervisors of Doctoral Candidates at African Universities. Stellenbosch, South Africa: Stellenbosch University.

Gatfield, T. (2005). An Investigation into PhD Supervisory Management Styles: Development of a Dynamic Conceptual Model and its Managerial Implications. J. Higher Edu. Pol. Manage. 27, 311–325. doi:10.1080/13600800500283585

Goodband, J. H., Solomon, Y., Samuels, P. C., Lawson, D., and Bhakta, R. (2012). Limits and Potentials of Social Networking in Academia: Case Study of the Evolution of a mathematicsFacebookcommunity. Learn. Media Tech. 37, 236–252. doi:10.1080/17439884.2011.587435

Gray, M. A., and Crosta, L. (2019). New Perspectives in Online Doctoral Supervision: a Systematic Literature Review. Stud. Cont. Edu. 41, 173–190. doi:10.1080/0158037x.2018.1532405

Gruzd, A., and Goertzen, M. (2013). “Wired Academia: Why Social Science Scholars Are Using Social media,” in 2013 46th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (IEEE), 3332–3341. doi:10.1109/hicss.2013.614

Holton, A. E., Baek, K., Coddington, M., and Yaschur, C. (2014). Seeking and Sharing: Motivations for Linking on Twitter. Commun. Res. Rep. 31, 33–40. doi:10.1080/08824096.2013.843165

Johnson, P. R., and Yang, S. (2009). “Uses and Gratifications of Twitter: An Examination of User Motives and Satisfaction of Twitter Use,” in Communication Technology Division of the Annual Convention of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (Boston, MA.

Katrimpouza, A., Tselios, N., and Kasimati, M.-C. (2019). Twitter Adoption, Students' Perceptions, Big Five Personality Traits and Learning Outcome: Lessons Learned from 3 Case Studies. Innov. Edu. Teach. Int. 56, 25–35. doi:10.1080/14703297.2017.1392890

Keefer, J. M. (2015). Experiencing Doctoral Liminality as a Conceptual Threshold and How Supervisors Can Use it. Innov. Edu. Teach. Int. 52, 17–28. doi:10.1080/14703297.2014.981839

Kim, H. M., Abels, E. G., and Yang, C. C. (2012). Who Disseminates Academic Library Information on Twitter?. Proc. Am. Soc. Info. Sci. Tech. 49, 1–4. doi:10.1002/meet.14504901317

Klar, S., Krupnikov, Y., Ryan, J. B., Searles, K., and Shmargad, Y. (2020). Using Social media to Promote Academic Research: Identifying the Benefits of Twitter for Sharing Academic Work. PloS one 15, e0229446. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0229446

Kumari, P. (2021). 5 Countries that Have Blocked Twitter & Why. Available at: https://www.scoopwhoop.com/news/countries-that-have-blocked-twitter/18 June (accessed 23 July, 2021)

Lee, A. (2008). How Are Doctoral Students Supervised? Concepts of Doctoral Research Supervision. Stud. Higher Edu. 33, 267–281. doi:10.1080/03075070802049202

Lee, A. (2018). How Can We Develop Supervisors for the Modern Doctorate?. Stud. Higher Edu. 43, 878–890. doi:10.1080/03075079.2018.1438116

Malik, A., Heyman-Schrum, C., and Johri, A. (2019). Use of Twitter across Educational Settings: a Review of the Literature. Int. J. Educ. Tech. Higher Edu. 16, 1–22. doi:10.1186/s41239-019-0166-x

Manca, S., and Ranieri, M. (2016). Facebook and the Others. Potentials and Obstacles of Social Media for Teaching in Higher Education. Comput. Edu. 95, 216–230. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2016.01.012

McPherson, M., Budge, K., and Lemon, N. (2015). New Practices in Doing Academic Development: Twitter as an Informal Learning Space. Int. J. Acad. Dev. 20, 126–136. doi:10.1080/1360144x.2015.1029485

Mehta, N., and Flickinger, T. (2014). The Times They Are A-Changin': Academia, Social media and the JGIM Twitter Journal Club. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 29, 1317–1318. doi:10.1007/s11606-014-2976-9

Menendez, M., Angeli, A. d., and Menestrina, Z. (2012). “Exploring the Virtual Space of Academia,” in From Research to Practice in the Design of Cooperative Systems: Results And Open Challenges (Springer), 49–63. doi:10.1007/978-1-4471-4093-1_4

Nández, G., and Borrego, Á. (2013). Use of Social Networks for Academic Purposes: A Case Study. Electron. Libr. 31, 781–791. doi:10.1108/el-03-2012-0031

Ngai, E. W. T., Tao, S. S. C., and Moon, K. K. L. (2015). Social media Research: Theories, Constructs, and Conceptual Frameworks. Int. J. Inf. Manage. 35, 33–44. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2014.09.004

Ovadia, S. (2014). ResearchGate and academia.Edu: Academic Social Networks. Behav. Soc. Sci. Librarian 33, 165–169. doi:10.1080/01639269.2014.934093

Prescott, B. T. (2019). Predicaments of Public Institutions in Rural Settings. Change Mag. Higher Learn. 51, 29–33. doi:10.1080/00091383.2019.1618142

Salmon, G., Ross, B., Pechenkina, E., and Chase, A.-M. (2015). The Space for Social media in Structured Online Learning. Res. Learn. Tech. 23. doi:10.3402/rlt.v23.28507

Sharratt, M., and Usoro, A. (2003). Understanding Knowledge-Sharing in Online Communities of Practice. Electron. J. Knowledge Manage. 1, 187–196.

Sugimoto, C. R., Work, S., Larivière, V., and Haustein, S. (2017). Scholarly Use of Social media and Altmetrics: A Review of the Literature. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Tech. 68, 2037–2062. doi:10.1002/asi.23833

Tomaselli, K., and Sundar, T. (2011). Twitter and African Academia. Editors' Bull. 7, 101–104. doi:10.1080/17521742.2011.685646

Tonia, T., Van Oyen, H., Berger, A., Schindler, C., and Künzli, N. (2020). If I Tweet Will You Cite Later? Follow-Up on the Effect of Social media Exposure on Article Downloads and Citations. Int. J. Public Health 65, 1797–1802. doi:10.1007/s00038-020-01519-8

Trafford, V., and Leshem, S. (2009). Doctorateness as a Threshold Concept. Innov. Edu. Teach. Int. 46, 305–316. doi:10.1080/14703290903069027

Wellington, J. (2013). Searching for 'doctorateness'. Stud. Higher Edu. 38, 1490–1503. doi:10.1080/03075079.2011.634901

Woodley, C., and Silvestri, M. (2014). The Internet Is Forever: Student Indiscretions Reveal the Need for Effective Social media Policies in Academia. Am. J. Distance Edu. 28, 126–138. doi:10.1080/08923647.2014.896587

Keywords: communities of practice, doctorateness, postgraduate training, research identity, social media space

Citation: Ferreira J (2021) Reflecting on the Viability of Twitter as Tool in the Postgraduate Supervision Process. Front. Educ. 6:705451. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.705451

Received: 05 May 2021; Accepted: 20 August 2021;

Published: 06 September 2021.

Edited by:

M. Meghan Raisch, Temple University, United StatesReviewed by:

Candace Nicole Hall, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville, United StatesFelecia Commodore, Old Dominion University, United States

Copyright © 2021 Ferreira. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: J.T. Ferreira, am9oYW4uZmVycmVpcmFAdXAuYWMuemE=

J.T. Ferreira

J.T. Ferreira