- Science and Research Centre Koper, Koper, Slovenia

Based on field research in Slovenian schools, the article examines the role of the family in the integration process of migrant children. While migrant children perceive the family as the most important factor influencing their overall well-being and life satisfaction, research shows that parents of migrant children are often not involved in school activities and life. The article explores how the role of parents in the integration process of migrant children in the school environment is understood at the policy level and how it is perceived by migrant children and the educational community. It also explores what are the main barriers to the involvement of migrant parents in schools and what are the existing practices and experiences in Slovenian schools. The analysis is based on qualitative research in Slovenian schools with children and the educational community conducted as part of the Migrant Children and Communities in a Transforming Europe (MiCREATE) project.

Introduction

Parental involvement in education of migrant children is paramount for their integration. Several studies have demonstrated the positive impact of parental and family engagement in school on children’s academic performance and success, and subsequently on their (future) participation in society. A general trend observed in Western societies is that parental involvement is very intense and engaged, “so that good parents are expected not just to provide material and emotional support and check homework, but also to participate in school choice and even help their teenage children apply to universities” (Weis, Cipollone and Jenkins in Antony-Newman, 2019: 2). The strong involvement of parents in schoolwork and the educational process is a new factor in the social differentiation of children (Ule, 2015: 25), because the children whose parents do not know how to participate in school or who are not able to provide support in school matters are worse off compared to the children who are supported by their parents.

However, analyses of the school engagement of migrant parents show that the ability to actively participate in their children’s education is significantly influenced by the parents’ class, race, gender, and migrant status (Baquedano-López et al., 2013). Migrant parents face particular challenges due to language barriers (Antony-Newman, 2019), unfamiliarity with the host country’s education system, socio-economic status (Tang, 2014), and cultural differences (Denessen et al., 2007; Calzada et al. 2015). While some migrant parents manage to overcome these obstacles and build relationship with teachers (Turney and Kao, 2009), parental engagement is still lower in schools with a high proportion of students who do not speak the language of instruction at home than in schools with fewer migrant students (European Education and Culture Executive Agency, Eurydice, 2019: 26). In this context, it is encouraging that in Europe, the vast majority of governments have put in place top-level regulations to promote schools’ efforts to inform and actively involve parents of migrant children in the educational process (European Education and Culture Executive Agency, Eurydice, 2019: 26), with the aim of supporting relationships between teachers and migrant parents and facilitating the benefits of involving parents in their children’s education.

The Slovenian context is noteworthy and calls for analytical attention for two main reasons: first, because, as Ule (2015) shows, compared to other European countries, Slovenian parents are among those who are most engaged in their children’s school, educational pathways, and school work and have high educational aspirations, which are also adopted by the children themselves; and second, because Slovenia is one of the few countries with educational policies that cover the areas of parental involvement in a holistic way. As reported in the Eurydice report, Slovenian policy puts emphasis on the potential of parents to contribute to the physical, cognitive, social, and emotional development of their children as well as to address any psychosocial difficulties (European Education and Culture Executive Agency, Eurydice, 2019: 26). However, as studies show, there are significant discrepancies between what is envisaged in policy and what is implemented in school practice (Dežan and Sedmak, 2020; Medarić et al., 2021).

There is a paucity of the literature on parental involvement in relation to the integration of migrant children within school environment. The research on migrant parents has been growing in the last years, but they are still an under-researched group (Antony-Newman, 2019). The article aims to fill this gap by examining the role of parents in the integration process within school environment, how it is conceived at the policy level and how it is perceived by migrant children and teachers. With regard to the latter, the article discusses how teachers perceive and promote the engagement of migrant parents in school (what are the practices of parental involvement, what are the reasons for non-involvement) and how migrant children see the role of their parents in relation to the integration process. The article brings new insights into the role of parents and the family in the integration of migrant children within educational setting and the obstacles to their involvement.

The analysis is based on qualitative research with teachers and migrant children from Slovenian primary and secondary schools, conducted as part of the Migrant Children and Communities in a Transforming Europe (MiCREATE) project.

The article begins with a theoretical framing of the relationship between family, school, and integration of migrant children, drawing attention to the challenges parents face in their engagement with school. Then the methodological approach of the field study is briefly presented and the empirical results are analyzed. The empirical part first describes the main policy documents and support measures aimed at bridging the gaps in cooperation between teachers and parents of migrant children. Thereafter, it pursues with presentation of fieldwork results, ending with a brief discussion and conclusion.

Theoretical framework

The role of family and school for the integration of migrant children

At the level of policy studies, migrant integration has typically meant measuring the degree to which immigrant groups equally participate in the economic and social institutions of the host society, taking into consideration structural aspects such as educational achievement, access to the labor market and discrimination (Schneider and Crul, 2010). Sociological and anthropological studies in this field have additionally placed emphasis on the processes of transition, construction of hybrid identities (Boland, 2020), and emerging modes of belonging (Grzymala-Kazlowska, 2016, 2017; Laoire et al., 2016). With the topicality and growing interest in the process of integrating migrant children, the role of parents and the family and school has become more important in this regard. There is a broad consensus on the importance of the family and schooling for the overall well-being and life satisfaction of children. However, as this section shows, the relationship between family, school and integration of migrant children is complex and multi-layered.

In view of integration processes and migrant children, the family is of key importance. Its supportive role is particularly important for newly arrived migrant children as it provides them with a sense of anchorage connection, security, and identity. Previous research on the anchoring (Grzymala-Kazlowska, 2016, 2017), of Slovenian migrant youth, i.e., research in how migrants connect to a new society and the process of psychological and social stabilization within it, shows that in connecting with the new society family plays a significant role that enables them to feel well, safe, and secure (Sedmak and Medarić, 2022). Indeed, children who have family members living in the same country are better able to cope with the daily challenges that migration brings (Sedmak and Dežan, 2021). Evidence from Danish school studies (Piekut et al., 2021), moreover, show that acceptance of migrant families and ethnic groups of children by teachers, the school, and the local community enhances the integration process of migrant children and, conversely, if children feel that their families are exposed to discrimination and negative prejudice, this has a negative impact on their readiness to adapt.

In addition to family, school is also one of the most important social institutions when it comes to the challenges of migrant children’s integration; it functions as a vehicle for promoting tolerance, intercultural dialogue, inclusion, and acceptance (Medarić and Sedmak, 2012) and serves as a place of social inclusion for children who are new to the local environment. From this perspective, schools play a role in meeting migrants’ needs in terms of language acquisition, developing relationships with peers and teachers (Due et al., 2015; Soriano and Cala, 2018) and providing a safe and stable environment for migrant children (Block et al., 2014; Seker and Sirkeci, 2015; Aydin et al., 2019). Moreover, through education, migrant children acquire new skills and knowledge that increase the chances of their future economic inclusion and upward mobility (Suárez-Orozco, 2017), thus combating the risks of socio-economic marginalization and exclusion.

School-family nexus has attracted interest of many academics in migration studies, who generated many important findings. Some found that migrant parents may perceive values of the host society incompatible with their parenting traditions, therefore they may try to preserve traditional cultural and religious values, thus reinforcing their migrant identity (Johannesen and Appoh, 2016; Bowie et al., 2017). Other shows that, if possible, parents choose a particular school where other members of the same ethnic community are already enrolled. This was the case in the study of Polish parents in the United Kingdom, who often choose schools already attended by other Polish children in the hope that their children will be supported by Polish peers. However, in some cases, this lead to slower language acquisition and a reduction in children’s social networks, slowing integration (Trevena et al., 2016).

Furthermore, in the context of school and family relations, studies demonstrate that parent and family engagement in school have an impact on migrant children’s academic achievement and success (Jung and Zhang, 2016). Moskal and Sime (2016) in this respect observe that children’s academic engagement and achievement is strengthened by supportive family relationships, while children’s motivation to learn is also related to parents’ recognition of the sacrifices they make to provide better opportunities for their children. Jung and Zhang (2016) moreover highlight that parental host society’s language proficiency and involvement in school are related to children’s cognitive development, directly as well as indirectly, through children’s educational aspirations. Finally, parental involvement in schools is important, as Turney and Kao (2009) suggest, also because in this way children recognize that education is important and because it provide parents with means of control, and access to information about their children, making them in a better position to intervene if their children are struggling.

Barriers to parental involvement in school/children education

Parental involvement in education is broadly defined as the resources parents invest in their child’s learning experience (Calzada et al., 2015) with the goal of supporting children’s academic and/or behavioral success. These include help with homework at home, communication with teachers and attendance at school, such as participation in parent-teacher conferences, involvement in parent organizations, attendance at school events, and volunteering at school (Turney and Kao, 2009; Young et al., 2013), as well as involvement in broader learning environments and extracurricular learning activities (Jung and Zhang, 2016).

The findings on racial and ethnic differences in parental involvement practices are fairly inconsistent, and sometimes even contradictory. Turney and Kao (2009), for example, indicate that Black and Hispanic parents are more involved in parent-teacher organizations than White parents and those Asian parents are less involved. In contrast, report of European Education and Culture Executive Agency, Eurydice (2019) finds that headmasters in schools with a high proportion of migrant students report lower parental engagement (European Education and Culture Executive Agency, Eurydice, 2019: 47). Jung and Zhang (2016) say that their findings do not confirm that ethnic background differentiates parental help with homework. Therefore, as Turney and Kao (2009) point out, it is important to note that parental engagement in school is a multidimensional and intersectional phenomenon. Differences in parental engagement exist not only between different ethnic groups, but also within these groups. The most common factors affecting engagement include time spent in the country (e.g., differences between foreign-born and native-born members of a particular ethnic group), language skills of migrant parents, socio-economic status of the migrant family, demographic characteristics of the family, and cultural proximity to the host society (Turney and Kao, 2009; Jung and Zhang, 2016).

Nevertheless, studies show quite consistently that the ability to actively participate in children’s education is significantly influenced by parents’ migration status (Baquedano-López et al., 2013). According to data from longitudinal Early Childhood Study from National Center for Educational Statistics 2001 from United States, which examined racial and immigrant differences in barriers to parental involvement in school, immigrant parents report more barriers to their children’s participation and engagement in school life compared to native parents (Turney and Kao, 2009).

Overall, studies confirm that language skills are important predictors of parental involvement and engagement in school (Turney and Kao, 2009). In a comparative synthesis of 40 qualitative and quantitative studies on parental engagement using migrant families in North America, Europe, Asia, and Australia as examples, Antony-Newman’s analysis has shown that migrant parents face significant challenges primarily due to language barriers (Antony-Newman, 2019), which significantly affect parental engagement in the case of migrant families (Sohn and Wang, 2006; Denessen et al., 2007). On the one hand, migrant parents may not be able to assist their children with homework and learning due to their limited knowledge of educational concepts and insufficient language skills (Colombo, 2006); on the other hand, language barriers also worsen the relationship and communication between them and teachers. Some studies report that parents often feel less confident because they do not speak the language and therefore do not feel comfortable in direct oral communication, preferring written communication with teachers (Sohn and Wang, 2006). Parents who do not speak the host country’s language are also more likely to report that they do not feel welcome at school (Turney and Kao, 2009). Children often act as translators or interpreters for parents who cannot communicate in the host country language. This can also promote children’s willingness to integrate, as they feel responsible for supporting their families (Moskal and Sime, 2016).

Lack of familiarity with the education system and the role of host schools is another barrier to parental involvement in schools (Antony-Newman, 2019). Some studies suggest that the lower level of support is due to migrant parents’ unfamiliarity with the school culture, organizational structure, educational standards, and requirements of the national school system (Crosnoe, 2010; OECD Education and Skills Today, 2020). This unfamiliarity with the school system can lead to a lack of confidence in their ability to guide their children’s educational trajectory (Peña, 2000), avoidance of helping their child achieve educational success through participation in school activities (Tang, 2014), and being in a worse position when advising their children on their educational path (Kristen, 2005).

Parental engagement is also influenced by the socio-economic status of the family. Tang (2014) highlights that migrant parents are more likely to report that meeting times suggested by teachers are unsuitable; this may be particularly true of low-income migrant families, whose adult members are more likely to face long working days, unstable working hours, and jobs far from their homes (Tang, 2014). In addition, some studies suggest that the parents of migrant children have, on average, lower levels of education (OECD Education and Skills Today, 2020: 16) and are therefore less able to support the child’s learning and improve their academic performance (Erikson and Jonsson, 1996: 26). Depending on socio-economic status, the family may also support and enable their child’s participation in extracurricular activities, where social networks are built that contribute to inclusion (Rerak-Zampou, 2014).

Studies show that cultural differences in many ways hinder cooperation and communicating between teachers and parents. Families have different attitudes toward schooling and interaction with school staff, and that these attitudes may be related to their experiences of schooling, religion, and cultural values. Cultural differences make parental involvement more difficult for teachers and school administrators. For example, Denessen et al. (2007) explain that parents may not know how to get involved; while Calzada et al. (2015) stress that they may not see involvement in their children’s schooling as their role or responsibility. Some studies have found that immigrant families are less likely to participate in certain school activities because they do not perceive the activity as directly linked to their child’s educational success (Hill and Torres, 2010). Not knowing each other’s culture, lifestyles and values (among both teachers and parents) negatively affect relationships and direct parental involvement. A study of Somali parents shows that parents need parental support for a successful transition into parenthood. Schools and social services can overcome barriers that prevent a lack of knowledge about the new country’s systems in relation to parenting (Osman et al., 2016).

The lack of information faced by migrant families due to language limitations often leads to a lack of integration of migrant children. In the school context, children from migrant families may also act as closed gates to the flow of information due to concerns about their family’s public image and consciously try not to impose additional burdens on their parents while resisting pressure from their parents (Säävälä et al., 2017). Existing school integration policies and practices in European schools often do not automatically include the dissemination of information about school rules and daily routines in migrant languages. On the other hand, a comparative study in six European countries has clearly shown that there is a need for such support (Sedmak and Dežan, 2021). A lack of information for migrant families was also revealed at a time of pandemic, when the disadvantage of migrant children became even more apparent and an integration process was seriously questioned (Gornik et al., 2020).

Finally, teachers and educational staff play a key role in building a cooperative relationship with parents. Licardo and Leite (2022) emphasize that teachers’ interpersonal and professional skills are important predictors of perceived cooperation with migrant parents. Migrant families may perceive the school climate as intimidating and dismissive or feel uncomfortable and disrespected due to teachers’ judgmental attitudes and communication style (Peña, 2000; Turney and Kao, 2009). While teachers acknowledge that barriers to parental involvement are due to a lack of school policies and ineffective communication strategies, they also frequently report barriers on the part of families, such as parents not attending school events, not responding to teacher communication, not having the resources to engage with the school, and being reluctant to engage with the school due to mandated screening procedures (Soutullo et al., 2016). In addition, Van Daal et al. (in Denessen et al., 2007) point out that teachers often feel that migrant parents lack language skills to communicate with teachers, hold school (exclusively) responsible for their child’s education and have a low interest in school matters.

Existing studies indicate that parents need to be supported by school authorities in order to promote the integration process of children. Expectations of appropriate involvement and how the family should cooperate with the school vary. This is especially true when intercultural differences are involved, i.e., in the case of migrant children and their families. López et al. (2001) also acknowledge in their study the difficulty of American schools to cope with the lower achievement and dropout of migrant children and the difficulty to effectively overcome the terrain of parental involvement and promote the academic success of migrant children. They found that the schools that were successful in parental involvement were successful because they placed the needs of parents above all other considerations for involvement. The schools were successful not because they were committed to a particular definition of parent involvement, but because they were committed to meeting the diverse needs of migrant parents on a daily and ongoing basis.

Methodology and methodological approach

The analysis is based on field research among migrant children and members of the education community in Slovenia, conducted as part of the MiCREATE - Migrant Children and Communities in a Transforming Europe project, funded by the Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Action.

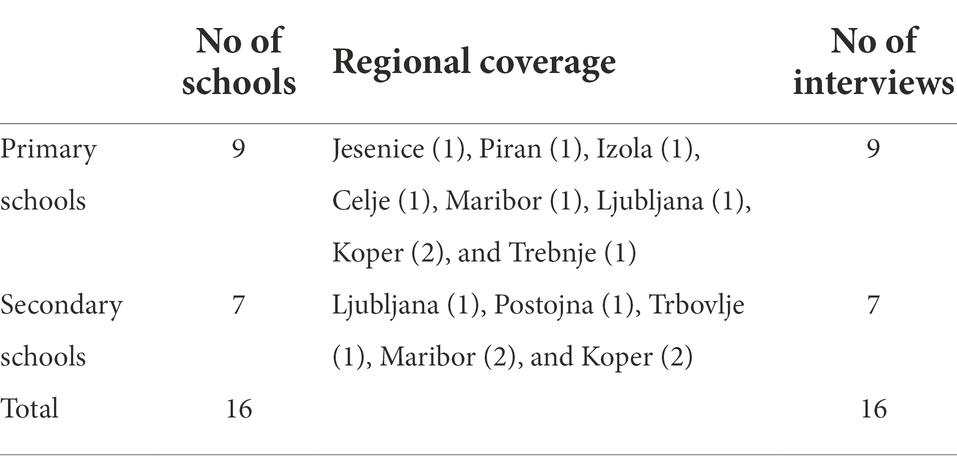

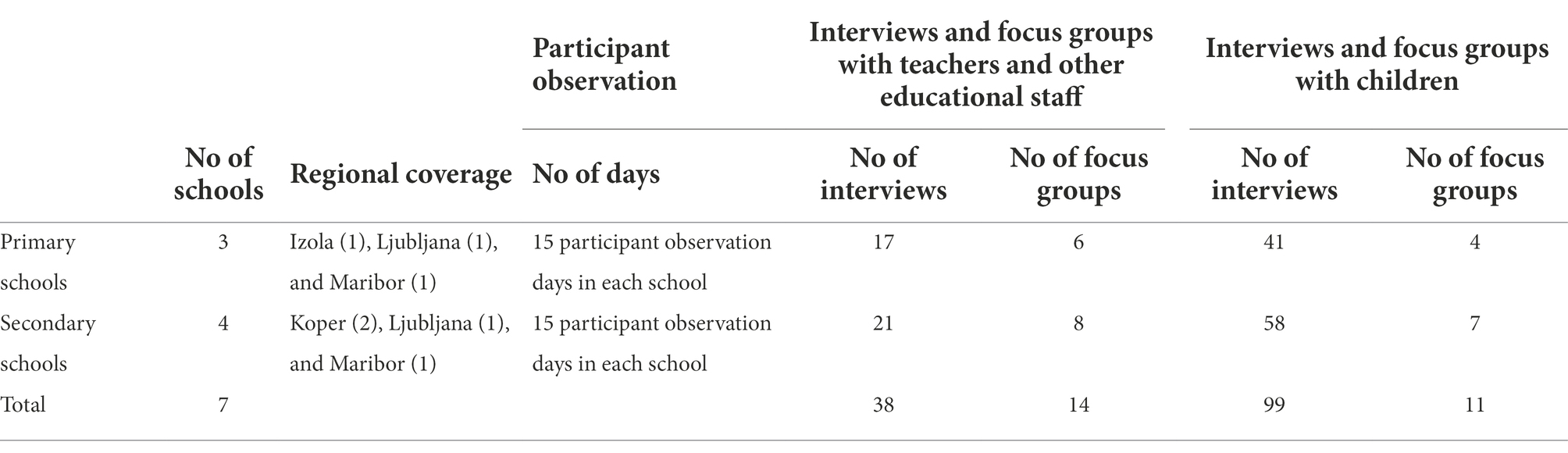

Research among members of the educational community in primary and secondary schools was conducted in the period from June to December 2019. A total of 54 interviews and 14 focus groups were conducted in 16 Slovenian primary and secondary schools. The selection criteria were to include elementary schools, vocational schools, and upper secondary schools in cities with a large migrant population and resulting cultural and ethnic diversity, and to achieve the most diversified sample in terms of migrant children’s experiences. First, background information on school life was obtained from a school representative, usually principals and school counselors in 16 schools. Afterwards, seven schools, three primary and four secondary, were selected for more in-depth research. In these schools, additional 38 interviews and focus groups were conducted with teachers and other educational staff in order to attain their perceptions, attitudes and opinions regarding approaches, measures, and the overall process of the integration of migrant children.

In the same seven schools, a multi-method research among children was conducted among migrant and local children and youth (aged 10–17 years) between October 2019 and March 2021. Initially, the participant observation phase was organized for at least 15 days per school. The participant observation days were conducted as the “field entry” phase. A combination of passive and moderate participation approaches (Fine and Sandstrom, 1988) was used. In the former, we passively participated as uninvolved observers in daily school activities to gather information about the general climate, daily routines, interactions, class and peer relationships, and general social dynamics in the schools. Later, a moderate observation approach was used to develop a rapport and establish a level of familiarity and trust that helped us to conduct the collection of autobiographical life stories with children and young people and focus groups. A total of 99 autobiographical life stories were collected, 60 of which with newly—arrived or long-term migrant children+. All interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analyzed according to the rules of qualitative data analysis (Denzin and Lincoln, 2011) using NVivo software.

What followed was the application of focus groups with 3–6 children/young people where participants discussed selected topics, e.g., migration, multiculturalism and cultural diversity in school, discrimination, racism, well-being, issues of identity and belonging, everyday school life, family etc. In research the child—centered approach was applied that sees children as relevant actors in society whose views should be taken into account in the matters that affect them (Clark and Moss, 2008; Fattore et al., 2008; Qvortrup et al., 2011; Volonakis, 2019; Gornik, 2020). Altogether, 11 focus groups were conducted with either the same or different children that already participated in the individual interviews (Tables 1, 2).1

Table 2. Methodology: Phase 2—In depth research in selected seven schools (October 2019–March 2021).

Results

Migrant children and their families

In their narratives, migrant children and youth often emphasized the central role of the family through statements, such as: “The family means everything to me” or “The family means life to me,” and parents are frequently seen as confidants, who are the only ones who can be trusted. The emotional role of parents in the process of adjusting to the new environment is significant for many migrant children. As one teenager (16) who migrated from Bosnia 4 years ago explains, their support was crucial in the first period after migrating to the new country:

“Also, my family, my parents always talked to me and everything./…/It meant a lot to me, we talked every day, they told me that everything would be fine, that I would slowly get used to life here, that they would be there for me and things like that.”

While parents provide emotional support to their children, not all of them are able to support them in their school activities because of language barriers or intersection of different issues, such as knowledge gaps and lack of time due to work and the like. On the contrary, the children often reported that they were the ones supporting younger siblings with school, because their parents could not support them due to lack of language skills. A 13-year-old girl from Kosovo who came to Slovenia less than 3 years ago explains:

For me it was difficult, because my mother does not understand the language, and when I did not start school early at 7 or 7.30 I had to help my brothers and translate if they did not understand.

So migrant children often find themselves in the role of helper, interpreter, mediator for family members, and feel responsible to support them. In their narratives, children sometimes also expressed that their parents sacrificed a lot to assure better future for them, so they felt they had to adapt quickly and do their best.

It’s hard, no one can be indifferent in such a situation, you leave, for example, your grandma and you go to some unknown place. The system is different and it’s not easy, but we have to make efforts because our parents did this for our own good. Not because they want something bad for us, but because they wish great things for us. We have to adapt, and we have to remain strong. (girl, 16 y/o, newly arrived)

Migrant parents and school

Documents and guidelines

The most relevant documents that address the integration of migrant children in Slovenia are the following: Strategy for Integrating Migrant Children, Pupils, and Students in the Education System in the Republic of Slovenia (Ministry of Education, Science and Sports, 2017),2 Guidelines for the Education of Alien Children in Kindergartens and Schools (2009), and National Education Institute Slovenia (2012), and the most recent Proposal for a program of work with immigrant children in the field of pre-school, primary, and secondary education (Rutar et al., 2018). In these documents, the parents are recognized as an essential element for the integration of children, moreover, the Proposal (Rutar et al., 2018) aims for the partnership between children, the school community, parents, and the local community.

The Strategy from 2017 identified problems, which need to be addressed in order to improve migrant integration in education system, including cooperation with migrant parents. More specifically, the document identified lack of recommendations and guidelines for working with migrant parents (strategies for communicating with migrant parents, strategies for integrating migrant parents in kindergarten and school settings, etc.). It also highlighted the need for teachers to learn basic elements of migrants’ language and culture and to gain skills of intercultural communication in order to avoid possible misunderstandings or facilitate contact with parents and encourage them to participate in school. Finally, lack of adequate financial support to assist in communicating with migrant parents (lack of financial resources for the translator, preparation of bilingual invitations, instructions, messages…) was mentioned as one of the obstacles that need to be addressed.

Cooperation with parents is addressed already in the Guidelines for the Education of Alien Children in Kindergartens and Schools (2009) that propose a collaboration of schools, parents, and local communities through confidants (for example, teachers responsible for migrant children) who coordinate the interaction between the three parties. Additionally, during enrolment process, the schools are also encouraged to assist the parents with information about the school system, school’s expectations, and documents, but also providing translators and the like. According to guidelines, school should also organize welcome days and similar activities before the beginning of the school year. Furthermore, schools are encouraged to offer language courses for migrant parents and thus contribute to the development of their language skills. Moreover, professionals in schools should gain competences to address communication challenges that might arise between the school and migrant parents (Rutar et al., 2018). While individual schools do offer such activities and courses for parents and their employees, the main problem is they are often project—funded and thus often only temporary.

According to these policy documents parents should be involved at different stages of migrant child’s educational process, however, as the documents are not binding, the implementation differs across schools. Parents should be involved in the preparation of individual plans for migrant learners that define the learning goals, strategies for teaching and individual plan of activities for each migrant child on a yearly basis. Additionally, following the guideline that for the first 2 years of schooling, migrant children are entitled to several adjustments in relation to their assessment, parents should also be involved in the decisions on the evaluation process, number of grades, time extension etc. The documents show a rather holistic perspective to tackling the issue of integration of migrant children in education that also involves parents at different stages. However, there is a significant gap between the existing policy documents and the everyday practices in Slovenian school. One of the main problems is that the documents are not binding and there are significant differences in their implementation across schools (see also Dežan and Sedmak, 2020; Medarič, 2020; Medarić et al., 2021).

Perceptions of educational staff

Involvements of parents of migrant children differ significantly across Slovenian schools. There is a large discrepancy between primary and secondary schools in terms of cooperation with parents, including parents with a migrant background. In primary schools, contact with parents is more intensive, as teachers meet with them at the beginning of the school year and cooperation usually continues throughout the year. In the secondary schools, parental involvement of parents is less intensive, partly because children aged 15 and over are considered young adults and are therefore more independent.

However, even at the primary school level, there are major differences between schools in terms of cooperation with migrant parents. Some schools see integration as a holistic process involving not only migrant children and their families but also local children, members of the educational community as well as local community, but many schools do not. Currently, there are no commonly accepted guidelines or systemic approach to the inclusion of migrant children in schools and the relationship between their parents and schools. Each school organizes its own way of connecting with parents, drawing on past experiences, and common practices. This means that the integration of migrant children and relationship with their parents in practice depend on the individual school and often on individual teachers, principals, counselors, etc. who play the most important role in the integration processes of children within school. Some schools that are located in traditionally more multicultural areas with a higher presence of ethnic minorities or economic migrants, or that generally recognize cultural, linguistic, and religious diversity as an important issue and value, have developed internal rules and informal procedures that promote acceptance, inclusion, and a general multicultural school ethos. These schools understand the importance of reaching out to the whole family and engaging with parents for successful integration of children. As presented by a school representative from such a multicultural area, the needs of migrant children and parents are addressed not only in schools, but in cooperation with different stakeholders in the whole local area:

Somehow, according to the needs, certain practices were established in this area. These include the coordinator for helping foreigners, education in the form of courses, Slovenian language courses offered by the Adult education center, workshop to which we direct our children and families. So basically, we try to equip these families as much as possible, and at the same time we explore through evaluation and monitoring what additional needs they have and what could be organized additionally for these families and children (Primary school representative)

In such schools parent’s well-being in the cooperation between parents and school is seen as significantly affecting the well-being of migrant children:

It is important that the parents feel safe and accepted in the first place. Because if the parents feel safe and accepted, then this affects the children, so the children feel better too (Primary school counselor).

In our research, however, this is not the norm, as there are many schools that do not specifically address migrant parents. For example, when a school principal was asked whether they get in touch with the parents of migrant children, if they organize any meetings and the like, he replied: No more than anyone else. We do not differentiate here highlighting the equality and the ‘ethnically blind approach’ as the reason for not approaching migrant parents.

On the other hand, some school representatives stressed that it is the parents of migrant children who cannot be reached, cannot speak the language and are generally non-responsive. In a case when a high school girl was missing school for longer periods of time and they could not reach the parents, their unresponsiveness was presented as “typical” for migrant parents:

And then you find yourself in a kind of a hole, where you don’t know what to do and how, because you don’t have parents to talk to, because they are unresponsive. As a rule they don’t read e-mails, they don’t answer your phone, because they don’t speak the language, they don’t come to school, and this is where the problem lies (Secondary school representative).

This discourse has often been used in reference to the Albanian migrant community that has been migrating as economic migrants in recent decades, especially from Kosovo and some parts of Northern Macedonia and is perceived as the ultimate “other,” i.e., “closed,” “self-sufficient,” and “culturally different,” with strong ethnic boundaries (Sedmak and Medarić, 2022). Since they speak the language of non-Slavic origin, they are more difficult to communicate to than, for example parents of children who come from other former republics of Yugoslavia like Bosnia, Serbia, Croatia, or even Northern Macedonia.

Migrant parents thus face specific challenges in their cooperation with schools. The issue of (the lack of) parent’s language knowledge was often raised by the teachers and other educational staff. The example below shows that there do not exist systemic solutions in solving the issue of communication with migrant parents, such as using interpreters or intercultural mediators. On the contrary, often ad hoc solutions, such as of children taking the role of translators are implemented:

A problem in communicating with the parents arises when, for example, they do not speak Slovenian. Last year, for example, there was a situation where the mother only spoke Albanian, not even English. Communication was not possible, and then the girl translated herself. It's funny because the child we are talking about translates for the parents and since you do not know the language, you cannot follow and you do not know if it was translated correctly (Secondary school principal).

The first contact between migrant families and the school environment usually happens in the process of the enrolment of children to school. Especially before the first visit to the school, sometimes parents bring relatives or friends who already speak the language, or even translators to help communicate with the school. In secondary schools children often enroll alone. Administrative officers explained that migrant students who have been in Slovenia for several years are frequently asked to help with translation in communication with parents, although none of them is satisfied with such solution.

The lack of information for migrant parents was recognized as an important issue in some schools; therefore, they try to address it by preparing the most relevant information for migrant parents about the necessities in their schools. For example, a primary school principal explained a recently implemented change in order to address this issue:

So, now I have to say that this school year, as a novelty, we held a joint parents' meeting intended for migrant parents, to which we also invited a translator. So, we provided the parents with all the information, with all the contacts, where they can go, when they can come to the consultation hours, even outside the ones that are for everyone, because they are overcrowded, simply for that reason.

Again, this is not a norm in all schools and some schools do not provide any additional information for migrant parents, even though in the narratives of teachers and counselors this was recognized as relevant.

Another important issue that arose from the interviews with educational staff is that intersectionality should be taken into account when discussing parental involvement in schools, thus their socio-economic status, educational background etc. As noted by a teacher from a multicultural school, parental educational background and language knowledge play an important role in their support and general involvement in education of their children:

Well, if you look at Slovenian children, it is the same issue: if the parents are more educated, they also support them with their work at home. I would not say this is specific for migrant children, but it is the same with Slovenian ones. If Slovenian children come from the families with lower educational background, they have less support at home and they have to do more on their own. It is the same with migrant parents, except that they are in a worse position, because they don’t master the language /…/. (Primary school Slovenian language teacher).

In the view of educational staff, if parents perceive education as an important value, this is also reflected in the attitudes of migrant children: I think that the attitude of parents is very important. If school, education is important for them, if they take it seriously, than they pass it on to children (Primary school counselor).

Educational staff also link children’s academic performance and willingness to integrate to a lack of motivation due to family circumstances, family values, and possibly low parental expectations. One primary school principal noted that children of economic migrants from the former Yugoslav republics whose parents are low-skilled workers do not have high academic aspirations and are also less willing to integrate:

Those who move from the formed e former Yugoslav republics…it is interesting that they have been for long time, but are less willing to advance, because they see their parents who are builders, shop assistants, and they say…ok, it is enough for me just to pass, to get the satisfactory grade, I don’t need better grades. And the teachers understand me, why would I learn Slovenian language, I speak Southern at home, my parents speak Southern between themselves or at school, so why would I speak Slovenian in school. “She understands me anyway”. They are very poorly motivated (Primary school principal).

Existing school practices

In the following, the existing practices for integration and support of migrant parents in Slovenian schools are presented. Such practices exist only in some schools, especially those that generally recognize multiculturality as a relevant issue, and more often in primary schools. Schools that generally recognize cultural, linguistic, and religious diversity also recognize the importance of reaching out to migrant parents and involving them in the school process. These schools address some of the barriers parents face and were already presented.

Supporting parents through the enrolment procedure

In some schools, migrant parents are supported in various ways during enrolment, e.g., with the necessary information in their mother tongue and the like. In one school, for example, a leaflet is produced in different languages containing basic information about the school, including the most important telephone numbers, office hours, holidays, information about school meals, subsidies, school books, and the like. It is distributed at the first parents’ meeting.

Communication problems are not systematically addressed with interpreters and/or cultural mediators, so the educators find their own ways. Sometimes other parents, teachers, friends or even children take on the role of translator for the parents of the newly arrived children; rarely but in some cases, the schools also engage authorized translators.

I organize someone within the school, if the language is spoken by someone. Like a teacher or a parent. For example, I do not speak Russian, but there is a mother from Russia who has offered to help. Or Albanian. We have quite a few children from Kosovo who speak Albanian. And the parents volunteer. /…/ Or we ask them to bring someone with them, or the parents of the migrants bring someone themselves who speaks the language (primary school, counselor).

Language courses for parents

In order to address the communication problems, some schools organize language courses for both migrant children and their parents. One of the main problems is that these courses are only run in some schools, are often project-based and funded, and are therefore often limited in time.

Cooperation of parents with the local community

The involvement of community resources to support migrant parents by schools is not common. Nevertheless, in some areas there is cooperation with non-governmental organizations that provide various activities for both children and parents, usually language acquisition support, information, etc.

We have very close contacts with the Slovenian philanthropy, Cene Štupar - Institute for Language Learning. They offer a language course also for the parents of children. For both, children, and parents. We have these courses in our school. So this is what we have … But we also cooperate with the Faculty of Philosophy, which sends its students to our schools as volunteers.

Schools rarely perceive the integration of migrant children as a process that needs to involve not only migrant children but also local children and families as well as the whole educational and local community. Nevertheless, individual schools recognize it as such:

In our school we really thought about it, because when we talk about inclusion, and acceptance, we have to think about everything. It’s not just about migrant families adapting to the new environment, it's about all of us living together.

Training of educators in intercultural awareness

During their studies, Slovenian teachers usually do not receive training that deals with issues of cultural diversity and interculturality, and at the school level there is no compulsory training for active teachers. Nevertheless, in recent years various courses, short-term trainings and the like have been organized for teachers to improve their skills. The organization of such activities depends on the individual school and participation in such trainings is voluntary. Therefore, there are also differences between schools and individuals who participate in such courses. Usually, schools that generally recognize multiculturality as a relevant issue, also more often organize such trainings or workshops. Often, participants are educators who already have affinity for the issues of intercultural coexistence, management of cultural diversity and similar.

There were some external trainings that we could attend, I also went myself. The workshop was about the integration of migrants into the school system (primary school teacher).

Despite the good examples presented, one of the main problems remains that the existing guidelines concerning migrant parents are not systematically implemented in practice in all Slovenian schools. The experiences of schools that have reached out to migrant parents show that this can be very positive, but the often temporary nature of these good practices is problematic.

Discussion and conclusion

The article examined the role of parents in the integration process from the perspectives of policy, migrant children, and educational staff. It takes as its starting point existing observations of studies that confirm positive effects of parental and family engagement in school on migrant children’s academic performance, general well-being, and integration.

The results of the research within Slovenian schools show that the family is central to the well-being of migrant children and youth. Their supportive role is particularly important for newly arrived migrant children as it provides them with a sense of support, security, and psychological and social stabilization. This has also been recognized by individual schools and their educational staff, who specifically addresses migrant parents and their needs and enhances their cooperation with schools. The analysis showed that language barriers and lack of information are among the most common obstacles to the participation of migrant parents in school and their children’s education as perceived by the educational staff, however, cultural differences or the confluence of various issues were also mentioned. This is in line with previous research that see language barriers and lack of information as a significant barrier in migrant children’s family and school cooperation (Crozier and Davies, 2007; Turney and Kao, 2009; Antony-Newman, 2019; Macia and Llevot Calvet, 2019). As Ule (2015) points out, the (non)participation of parents represents an important new element of social differentiation and it covertly sanctions those who cannot support their children, who are less involved in schoolwork and educational trajectories of children due to various reasons. The support of parents is crucial also for the prevention of school dropouts and successful transition from education to employment (Macia and Llevot Calvet, 2019; Bojnec, 2021). Some schools are addressing these issues by supporting migrant parents in enrolment, addressing the linguistic barriers, organizing support in the local community, and focusing on training their educators, however, these measures are not equally or systematically addressed in all school. Analysis uncovered that schools from traditionally more culturally diverse environments manifest higher affinity to the issues of multiculturalism and management of cultural diversity as well as higher level of awareness about the specific needs of migrant children and cooperation with their parents. Discrepancies have also been noted between primary and secondary schools, with the primary schools being more successful and attentive in maintaining contacts with migrant parents.

Slovenia was among the first in the European Union to develop an integration strategy for migrant integration in education (European Education and Culture Executive Agency, Eurydice, 2019: 58). The documents are based on a comprehensive approach to the integration of migrant children in schools and set targets that stem from gaps identified in the field and, more importantly, address all relevant elements and actors, i.e., teachers, policy makers, the local and national community, language support, school curricula as well as migrant parents. However, these policy documents are not successfully implemented in practice and there is still a significant gap between existing policy documents and daily practice in Slovenian schools (see also Dežan and Sedmak, 2020; Medarič, 2020; Medarić et al., 2021). The analysis has also shown that non-binding policy documents do not provide satisfactory results. As a systemic governmental approach is still missing, the vague framework of integration policy leads to large differences between schools. In relation to the supporting the cooperation of migrant children’s parents and schools, the analysis shows there is a need to adopt a legally and financially supported approach that would for example, address the language barriers through official translators or cultural mediators, but also organize regular trainings for educational staff. The study shows that extensive knowledge already exists in Slovenia and that there are policy models that could enable greater parental involvement and cooperation with schools for migrant parents. However, there is a need for additional focus on better implementation by ensuring adequate and stable funding and comprehensive solutions. Although Slovenia being specific as it is one of the few countries that address parental involvement of migrant children in a very holistic way, the results show that it still faces similar challenges as other European countries such as Spain, Italy, or Luxembourg regarding parental involvement of migrant children in school (Macia and Llevot Calvet, 2019). This study is based on the perspective of educational staff and children and does not include the perspective of parents, which is its main limitation. Future research should also focus on their experiences, views, and opinions.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by The Commission for Ethical Issues of ZRS Koper. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the part of the MiCREATE project—Migrant Children and Communities in a Transforming Europe that has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement (No. 822664) and the Slovenian Research Agency (research core funding No. P6-0279).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^For more information about methodology and results of study among children and young people see Dežan and Sedmak (2021).

2. ^The first version of this document was issued in 2007 and presents the foundations for the integration of migrant children in the school environment in Slovenia.

References

Antony-Newman, M. (2019). Parental involvement of immigrant parents: a meta-synthesis. Educ. Rev. 71, 362–381. doi: 10.1080/00131911.2017.1423278

Aydin, H., Gundogdu, M., and Akgul, A. (2019). Integration of Syrian refugees in Turkey: understanding the educators’ perception. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 20, 29–1040. doi: 10.1007/s12134-018-0638-1

Baquedano-López, P., Alexander, R. A., and Hernández, S. J. (2013). Equity issues in parental and community involvement in schools. Rev. Res. Educ. 37, 149–182. doi: 10.3102/0091732x12459718

Block, K., Cross, S., Riggs, E., and Gibbs, L. (2014). Supporting schools to create an inclusive environment for refugee students. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 18, 1337–1355. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2014.899636

Bojnec, Š. (2021). Policy and practical lessons learned regarding youth and NEETs in Slovenia. Calitatea Vieții 32, 371–397. doi: 10.46841/RCV.2021.04.03

Boland, C. (2020). Hybrid identity and practices to negotiate belonging: Madrid’s Muslim youth of migrant origin. Comp. Migrat. Stud. 8. doi: 10.1186/s40878-020-00185-2

Bowie, B., Wojnar, D., and Isaak, A. (2017). Somali families’ experiences of parenting in the United States. West. J. Nurs. Res. 39, 273–289. doi: 10.1177/0193945916656147

Calzada, E. J., Huang, K. Y., Hernandez, M., Soriano, E., Acra, C. F., Dawson-McClure, S., et al. (2015). Family and teacher characteristics as predictors of parent involvement in education during early childhood among afro-Caribbean and Latino immigrant families. Urban Educ. 50, 870–896. doi: 10.1177/0042085914534862

Clark, A., and Moss, P. (2008). Spaces to Play: More Listening to Young Children Using the Mosaic Approach London: London National Children’s Bureau.

Colombo, M. W. (2006). Building school partnerships with culturally and linguistically diverse families. Phi Delta Kappan 88, 314–318. doi: 10.1177/003172170608800414

Crosnoe, R. (2010). Two-generation strategies and involving immigrant parents in Children’s education. [online] Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED511766.pdf

Crozier, G., and Davies, J. (2007). Hard to reach parents or hard to reach schools? A discussion of home-school relations, with particular reference to Bangladeshi and Pakistani parents. Br. Educ. Res. J. 33, 295–313. doi: 10.1080/01411920701243578

Denessen, E., Bakker, J., and Gierveld, M. (2007). Multi-ethnic schools' parental involvement policies and practices. Sch. Commun. J. 17, 27–43.

Denzin, N. K., and Lincoln, Y. S. (2011). The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research 4th Edn. Thousand Oaks: Sage

Dežan, L., and Sedmak, M. (2020). Between systemic responsibility and personal engagements: integration of newly arrived migrant children in Slovenia. Ann. Ser. Hist. Sociol. XXX, 559–574. doi: 10.19233/ASHS.2020.37

Dežan, L., and Sedmak, M. (2021). National report on qualitative research among newly arrived migrant children, long-term migrant children and local children: Slovenia. (Report). Science and Research Centre Koper.

Due, C., Riggs, D.W., and Augoustinos, M. (2015). The Education, Wellbeing and Identity of Children With Migrant or Refugee Backgrounds. Adelaide: The University of Adelaide

Erikson, R., and Jonsson, J. O. (1996). “Explaining class inequality in education: the Swedish test case,” in Can Education Be Equalized. eds. R. Erikson and J. O. Jonsson (Stockholm: Westview Press), 1–63.

European Education and Culture Executive Agency, Eurydice (2019). Integrating students from migrant backgrounds into schools in Europe: National policies and measures. Publications Office. Available at: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2797/819077

Fattore, T., Mason, J., and Watson, E. (2008). When children are asked about their well-being: towards a framework for guiding policy. Child Indic. Res. 2, 57–77. doi: 10.1007/s12187-008-9025-3

Fine, G. A., and Sandstrom, K. L. (1988). Knowing Children Participant Observations With Minors: Qualitative Research Methods 15. California: Sage Publications

Gornik, B. (2020). The principles of child-centred migrant integration policy: conclusions from the literature. Ann. Ser. Hist. Sociol. 30, 531–542.

Gornik, B., Dežan, L., Sedmak, M., and Medarić, Z. (2020). Distance learning in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic and the reproduction of social inequality in the case of migrant children. Družbosl. Razp. 36, 149–168.

Grzymala-Kazlowska, A. (2016). Social anchoring: immigrant identity, security and integration reconnected? Sociology 50, 1123–1139. doi: 10.1177/0038038515594091

Grzymala-Kazlowska, A. (2017). From connecting to social anchoring: adaptation and “settlement” of polish migrants in the UK. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 44, 252–269. doi: 10.1080/1369183x.2017.1341713

Guidelines for the Education of Alien Children in Kindergartens and Schools (2009) Ljubljana, Zavod RS za šolstvo. Available at: http://eportal.mss.edus.si/msswww/programi2018/programi/media/pdf/smernice/Smernice_izobrazevanje_otrok_tujcev.pdf (Accessed 26 Jul. 2022).

Hill, N. E., and Torres, K. (2010). Negotiating the American dream: the paradox of aspirations and achievement among Latino students and engagement between their families and schools. J. Soc. Issues 66, 96–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2009.01635.x

Johannesen, B. O., and Appoh, L. (2016). My children are Norwegian but i am a foreigner. Nord. J. Migr. Res. 6, 158–165. doi: 10.1515/njmr-2016-0017

Jung, E., and Zhang, Y. (2016). Parental involvement, children’s aspirations, and achievement in new immigrant families. J. Educ. Res. 109, 333–350. doi: 10.1080/00220671.2014.959112

Kristen, C. (2005). School Choice and Ethnic School Segregation: Primary School Selection in Germany. Münster: Waxmann

Laoire, C. N., Carpena-Méndez, F., and White, A. (2016). Childhood and Migration in Europe: Portraits of Mobility, Identity and Belonging in Contemporary Ireland, London: Routledge.

Licardo, M., and Leite, L. O. (2022). Collaboration with immigrant parents in early childhood education in Slovenia: how important are environmental conditions and skills of teachers? Cog. Educ. 9. doi: 10.1080/2331186x.2022.2034392

López, G. R., Scribner, J. D., and Mahitivanichcha, K. (2001). Redefining parental involvement: lessons from high-performing migrant-impacted schools. Am. Educ. Res. J. 38, 253–288. doi: 10.3102/00028312038002253

Macia, B. M., and Llevot Calvet, N. (eds.) (2019). Families and schools. The involvement of foreign families in schools. Lleida: Edicions de la Universitat de Lleida.

Medarič, Z. (2020). Migrant children and child-centredness: experiences from Slovenian schools. Ann. Ser. Hist. Sociol. 30, 543–558. doi: 10.19233/ASHS.2020.36

Medarić, Z., and Sedmak, M. (2012). Childrens Voices: Interethnic Violence in the School Environment. Koper: Annales University Press.

Medarić, Z., Sedmak, M., Dežan, L., and Gornik, B. (2021). Integration of migrant children in Slovenian schools (La integración de los niños migrantes en las escuelas eslovenas). Cult. Educ. 33, 758–785. doi: 10.1080/11356405.2021.1973222

Ministry of Education, Science and Sports (2017). Strategy for integrating migrant children, pupils and students in the education system in the Republic of Slovenia.

Moskal, M., and Sime, D. (2016). Polish migrant children’s transcultural lives and transnational language use. Centr. East. Eur. Migrat. Rev. 5, 35–48. doi: 10.17467/ceemr.2016.09

National Education Institute Slovenia (2012). Guidelines for integrating immigrant children into kindergartens and schools (Smernice za vključevanje otrok priseljencev v vrtce in šole). Ljubljana: Zavod za šolstvo.

OECD Education and Skills Today (2020). Supporting immigrant and refugee students amid the coronavirus pandemic. [online] OECD Education and Skills Today. Available at: https://www.gov.si/assets/ministrstva/MIZS/Dokumenti/Zakonodaja/EN/Integration-of-migrants-into-school-system-guidelines-2012.doc (Accessed July 25, 2022).

Osman, F., Klingberg-Allvin, M., Flacking, R., and Schön, U.-K. (2016). Parenthood in transition – Somali-born parents’ experiences of and needs for parenting support programmes. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 16. doi: 10.1186/s12914-016-0082-2

Peña, D. C. (2000). Parent involvement: influencing factors and implications. J. Educ. Res. 94, 42–54. doi: 10.1080/00220670009598741

Piekut, A., Jacobsen, G. H., Hobel, P., Jensen, S. S., and Høegh, T. (2021). National report on qualitative research. Denmark (Newly arrived migrant children, long-term migrant children, local children), Odense: University of Southern Denmark.

Qvortrup, J., Corsaro, W. A., and Honig, M. S. (2011). The Palgrave Handbook of Childhood Studies. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

Rerak-Zampou, M. (2014). Social integration of polish adolescents from Greek and polish high schools in Athens. Stud. Migracy. 40, 259–276.

Rutar, S., Knez, M., Pevec Semec, K., Jelen Madruša, M., Majcen, I., Korošec, J., et al. (2018). Proposal for a Program of Work with Immigrant Children in the Field of Pre-School, Primary and Secondary Education (Predlog programa dela z otroki priseljenci za področje predšolske vzgoje, osnovnošolskega in srednješolskega izobraževanja). Available at: www.medkulturnost.si/wpcontent/uploads/2018/09/Predlog-programa-dela-zotrokipriseljenci.pdf (Accessed August 23, 2019).

Säävälä, M., T, E., and Alitolppa-Niitamo, A. (2017). Immigrant home-school information flows in Finnish comprehensive schools. Int. J. Migrat. Health Soc. Care 13, 39–52. doi: 10.1108/ijmhsc-10-2015-0040

Schneider, J., and Crul, M. (2010). New insights into assimilation and integration theory: introduction to the special issue. Ethn. Racial Stud. 33, 1143–1148. doi: 10.1080/01419871003777809

Sedmak, M., and Dežan, L. (2021). Comparative report on qualitative research—newly arrived migrant children—Slovenia (Micreate Project Report). Koper: Znanstveno-raziskovalno središče.

Sedmak, M., and Medarić, Z. (2022). Anchoring, belongings and identities of migrant teenagers in Slovenia. Study of Ethnicity and Nationalism [Preprint]. doi: 10.1111/sena.12367

Seker, B. D., and Sirkeci, I. (2015). Challenges for refugee children at school in eastern Turkey. Econ. Soc. 8, 122–133. doi: 10.14254/2071-789x.2015/8-4/9

Sohn, S., and Wang, X. C. (2006). Immigrant parents’ involvement in American schools: perspectives from Korean mothers. Early Childhood Educ. J. 34, 125–132. doi: 10.1007/s10643-006-0070-6

Soriano, E., and Cala, V. C. C. (2018). School and emotional well-being: a transcultural analysis on youth in southern Spain. Health Educ. 118, 171–181. doi: 10.1108/he-07-2017-0038

Soutullo, O. R., Smith-Bonahue, T. M., Sanders-Smith, S. C., and Navia, L. E. (2016). Discouraging partnerships? Teachers’ perspectives on immigration-related barriers to family-school collaboration. Sch. Psychol. Q. 31, 226–240. doi: 10.1037/spq0000148

Suárez-Orozco, C. (2017). The diverse immigrant student experience: what does it mean for teaching? Educ. Stud. 53, 522–534. doi: 10.1080/00131946.2017.1355796

Tang, S. (2014). Social capital and determinants of immigrant family educational involvement. J. Educ. Res. 108, 22–34. doi: 10.1080/00220671.2013.833076

Trevena, P., McGhee, D., and Heath, S. (2016). Parental capital and strategies for school choice making: polish parents in England and Scotland. Centr. East. Eur. Migrat. Rev. 5, 71–92. doi: 10.17467/ceemr.2016.10

Turney, K., and Kao, G. (2009). Barriers to school involvement: are immigrant parents disadvantaged? J. Educ. Res. 102, 257–271. doi: 10.3200/joer.102.4.257-271

Ule, M. (2015). The role of parents in children's educational trajectories in Slovenia. Sodob. Pedagog. 66:10.

Volonakis, D. (2019). Theorising childhood: citizenship, rights, and participation, edited by Claudio Baraldi, tom Cockburn. Int. J. Child. Rights 27, 586–588. doi: 10.1163/15718182-02703008

Keywords: migrant children, integration, schools, family, well-being

Citation: Medarić Z, Gornik B and Sedmak M (2022) What about the family? The role and meaning of family in the integration of migrant children: Evidence from Slovenian schools. Front. Educ. 7:1003759. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1003759

Edited by:

Sara Victoria Carrasco Segovia, University of Barcelona, SpainReviewed by:

Juan Sánchez García, Autonomous University of Nuevo León, MexicoŠtefan Bojnec, University of Primorska, Slovenia

Copyright © 2022 Medarić, Gornik and Sedmak. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zorana Medarić, em9yYW5hLm1lZGFyaWNAenJzLWtwLnNp

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Zorana Medarić

Zorana Medarić Barbara Gornik†

Barbara Gornik† Mateja Sedmak

Mateja Sedmak