- Optentia Research Unit, North-West University, Vanderbijlpark, South Africa

Introduction: Teachers’ sense of self-efficacy has been identified by research as a key factor in the successful implementation of inclusive education. This article reports on disabling factors in South Africa that are reportedly influencing inclusive Full-Service school (FSS) teachers’ sense of self-efficacy to implement inclusive education successfully.

Methodology: A qualitative study, using semi-structured individual and group interviews as well as collages, was employed.

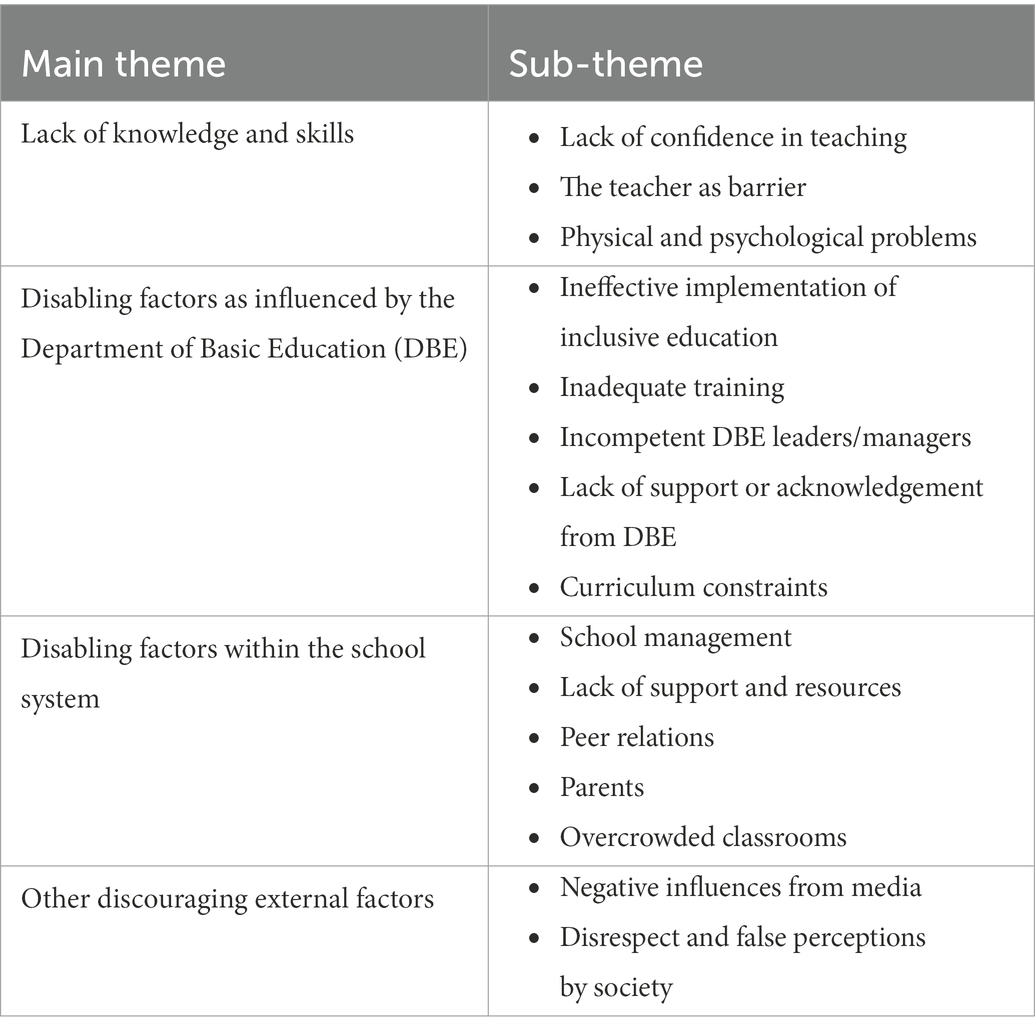

Results: The findings revealed that the disabling factors included internal and external factors. Internal factors comprised a lack of knowledge and skills, including a lack of self-confidence, FSS teachers seeing themselves as a barrier, and physical and psychological problems. External factors were also identified. They are ineffective implementation of inclusive education, inadequate training, incompetent education department officials and managers, a lack of support from the education department, curriculum constraints, as well as disabling factors within the school system. Negative media perceptions were also mentioned.

Conclusion: It was concluded that it is important for the basic and higher education departments of education to be aware of the identified disabling factors and purposefully attempt to improve the external factors, while ensuring that FSS teachers’ capabilities are developed and sustained in in-service and pre-service teacher education. This could contribute to developing and improving their sense of self-efficacy.

Introduction

Inclusive education requires teachers to be effective in providing quality education for all learners, despite them having diverse learning needs (Nel et al., 2022). In such a classroom it is essential for teachers to have a sense of self-efficacy, since the effectiveness of teaching is influenced by teachers’ own personal evaluation of how capable they are of teaching (Wood and Olivier, 2010; Ryan and Mathews, 2022). Self-efficacy can be defined as the belief in one’s capabilities to organize and execute the course of action required to produce results (Bandura, 1994) and has been identified as a major mediator for behavior, and importantly, for behavioral change (Zee and Koomen, 2016; Savolainen et al., 2022). Positive self-efficacy beliefs are related to an internal locus of control and motivation (Wood and Olivier, 2010) which requires a continuous review of a teacher’s capabilities in order to bring about the desired outcomes of learner engagement and learning. This can result in a spiral nature of positive self-efficacy beliefs, meaning that the ability to achieve success creates a new successful experience which then affects the efficacy beliefs in a progressive positive way (Zimmerman and Cleary, 2006). For this study, Bandura’s definition of self-efficacy within the social cognitive theory was chosen to underpin the research. Theories about self-efficacy include social cognitive theory, social learning theory, self-concept theory and attribution theory, but various researchers affirm that self-efficacy is best understood in the context of social cognitive theory (e.g., De Oliviera Fernandez et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2020; Schunk and DiBenedetto, 2020). The social-cognitive theory expounds the understanding, nature and causes of human behavior and motivation (Skaalvik and Skaalvik, 2010). It specifically emphasizes how cognitive, behavioral, personal, and environmental factors interact to determine motivation and behavior (Crothers et al., 2008). In this regard self-efficacy emphasizes the evolution and exercise of human agency in order for people to have some influence over what they do (Bandura, 2006).

Teacher self-efficacy can be conceptualized as believing in one’s own abilities to be an accomplished teacher, as well as being able to deal with challenges in the school environment and classroom (Bandura, 1997; De Oliviera Fernandez et al., 2016). Teachers with a high sense of self-efficacy tend to experiment with methods of instruction, seek improved teaching methods and experiment with instructional materials (Griful-Freixenet et al., 2021; Devi and Ganguly, 2022) which result in positive teaching behaviors and higher learner performance (Temiz and Topcu, 2013). They therefore believe that they can influence how well learners learn and persist with those learners who may be considered difficult or unmotivated (Klassen and Chiu, 2010; Guskey and Passaro, 2012). Kosko and Wilkins (2009) affirm that concerning learners who have special education needs self-efficient teachers are more inclined to include them in mainstream classes and not refer them to special education settings. Consequently, teachers with a high sense of self-efficacy could be more motivated to implement inclusive education successfully. However, research studies have shown that adequate preparation, training, and support are important requirements for a high level of teacher self-efficacy beliefs in an inclusive education environment (Savolainen et al., 2012). Yet, regardless of all the support and training South African teachers have already received regarding inclusive education, they still seem to feel disempowered and ineffective in the implementation of inclusive education (Engelbrecht et al., 2017; Nel, 2020; Walton and Engelbrecht, 2022). This results in negative attitudes, demotivation, a lack of self-control and a low sense of self-efficacy disabling them to teach effectively in an inclusive classroom (Bandura, 2006; Memisevic et al., 2021; Van Mieghem et al., 2022). In the South African context teachers have to deal with complex socio-, economic-, political-, cultural-and language situations both in and out of the classroom. This often creates stress which can exacerbate feelings of loneliness, isolation and disempowerment (Clipa, 2017) and consequently a feeling of inefficiency. Teachers are often so discouraged by this loss of control that they lose their enthusiasm and motivation, and as a result, the entire learning process can be hampered (Prinsloo and Gasa, 2016) resulting in not committing to implementing inclusive education effectively.

South Africa has introduced inclusive education with Education White Paper 6 (EWP6) in 2001 [Department of Education (DoE), 2001]. One of the key strategies of EWP6 was to increasingly transform ordinary mainstream primary schools into inclusive Full-Service Schools (FSS). Thus, the current school system consists of ordinary mainstream schools, special schools and FSS. The ordinary mainstream school mainly has learners who need low-intensive support and learners in special schools have high-intensive support needs (Department of Education (DoE), 2001). In this article factors that disable teachers’ sense of self-efficiency to teach in FSS in South Africa, have been explored in order to identify what needs to be addressed by education systems and teacher education to enhance teachers’ sense of self-efficacy so that they can feel more empowered and equipped to teach effectively. A FSS can be viewed as a mainstream school which provides quality education for all learners by meeting the full range of learning needs in an equitable manner. This means that these schools should provide education for regular learners, as well as those with disabilities in an inclusive setting (Department of Education (DoE), 2001). However, the transformation of these schools have been started recently and are still experiencing various challenges to make inclusion work (Ayaya et al., 2021; Makhalemele and Nel, 2021). During the transformation teachers in these schools are usually not consulted or asked by the department of basic education if they are committed to inclusion. They are simply expected to remain and teach in an inclusive manner as required by policy, i.e., EWP6.

Consequently, this research was guided by the following research question: What influences FSS teachers’ sense of self-efficacy, disabling them to implement inclusive education successfully?

Research methodology

A qualitative interpretive design, by employing a multiple case study (two FSS) as strategy of inquiry, was chosen for this study. Data was collected through semi-structured focus group and individual interviews (Creswell, 2012), as well as collages (Van Schalkwyk, 2010). The use of three data collection methods ensured that rich data were collected, and that validity and reliability could be ensured. Interviews are a well-known and used qualitative data collection method. Collages were deemed a valuable data collection tool as it is regarded as a symbolic representation which exposes social meaning, process and values (McMillan and Schumacher, 2014). It is also a process of narrating life experiences using linguistic and non-linguistic modes of expression (Van Schalkwyk, 2010). Butler-Kisber and Poldma (2010) assert that collages can assist in conceptualizing a phenomenon and get a more nuanced understanding of it.

Sampling

The population sample was drawn from two FSS in the Vaal Triangle area of South Africa. Both schools are located in a semi-rural township with low socio-economic levels and limited resources. The schools were identified as FSS by the Gauteng Department of Education (GDE). The principals indicated that they were eager to be FSS because they believed in the principle of inclusion. However, they acknowledge that many challenges remain.

Participants were purposively selected in terms of their suitability and convenience for the study (Creswell, 2012). These included qualified teachers currently working in the selected FSS, and who were willing and committed to participate in this study. FSS were chosen, because they are intended to function as fully inclusive education institutions providing quality education for all learners, irrespective of disability or differences in learning style or pace. Two FSS that were in close proximity to each other were selected, since they are in the same socio-economic environment and therefore limited too wide a range of systemic variables. Twenty eight teachers voluntarily participated in this research, 14 from the first school and 14 from the second school. All these participants were qualified teachers and had 5 years or more teaching experience. Five of these participants had a post graduate degree, specializing in learner support and two had a Masters degree in Education in specific subject fields. Thus, based on qualifications and experience these participants were deemed able to provide rich data.

Data collection process

Two semi-structured focus group interviews were conducted in each of the selected schools. The groups consisted of between six to eight participants each which is confirmed by Cobern and Adams (2020) as acceptable group sizes. The groups were divided into Foundation Phase (Grade 0 to 3) and Intermediate Phase (Grade 4 to 6) teachers. In school A the first focus group consisted of six participants and the second of eight participants. The focus groups in School B had seven participants in each group. The interviews were not longer than an hour and participants were allowed to take short comfort breaks where needed. Probing and prompts were used during the interviews to ensure rich and saturated data. All focus group and individual interviews were audio-tape-recorded during the research process and verbatim transcribed.

During these interviews the following list of semi-structured questions was used:

•How do you feel about teaching within an inclusive education system?

•What does the term teacher self-efficacy mean to you?

•What do you believe is disabling your sense of teacher self-efficacy within an inclusive Full-Service School?

During the collage-making activity, the participants got the opportunity to express their feelings visually about their sense of teacher self-efficacy within an inclusive education system. Ten participants voluntary (five teachers from each school) made two collages each. The material, including paper, glue, pens and a large variety of magazines were provided by the principal researcher. The participants could also use their own material if they wanted to. In the first collage (collage one) they had to illustrate how they experienced their self-efficacy currently in teaching within an inclusive education system and in the second collage (collage two) how they would want their self-efficacy to be. This was an individual activity and the participants were allowed to choose a venue at the schools where they felt comfortable and could not be disturbed. Afterwards the participants were individually interviewed about their collages to gain insight in what they believe is disabling their sense of teacher-self-efficacy.

Ethical considerations

Ethics approval was gained from the Higher Education Institution under whose supervision this study was conducted, the Gauteng Department of Education, as well as from the school principals. Each participant also signed an informed consent letter where the purpose of the research was explained to them. In this letter it was also indicated that they could withdraw from the study at any moment. Confidentiality was ensured for the individual activities, but it was explained that it cannot be fully guaranteed during the group interviews.

Role of the researchers

The qualitative researcher is seen as the most important instrument in the data-collection research process and therefore the principal researcher was an integral part of each step in the data-collection process (Merriam, 2009; Creswell, 2012). The secondary researcher acted as controller of all the research processes. Both researchers were intensely aware of the fact that personal involvement can introduce a range of strategic, ethical, and personal issues. Consequently, the principal research constantly reflected with the secondary researcher to ensure that objectivity was upheld. Objectivity included remaining true to the research aim, being impartial to the outcome of the research, acknowledging possible preconceptions and operating in as unbiased and value-free a way as possible (Association for Qualitative Research, 2012). The participants were anonymized, and the principal researcher was the only one who had contact with them during the data collection process and during member-checking. The different roles of the researcher and the participants were also clarified with all the participants at the start of the research.

Data analysis

The data obtained from the verbatim transcriptions of the four semi-structured group and ten individual interviews, as well as the collages were inductively analyzed by using a constant comparative method (Merriam, 2009). When using this method to analyze qualitative data, one segment of data (collages) is compared with another (semi-structured interviews) to determine similarities and differences (Merriam, 2009). The overall objective of the constant comparative analysis is also to identify patterns in all the data which are arranged in relationship to one another (Merriam, 2009). By using an inductive content analysis the data directed a set of integrated codes and themes that emerged, rather than imposing a set of codes onto them (Creswell, 2012). Five phases were implemented during the data analysis, including organizing and preparing the data, reading through the verbatim, transcriptions repeatedly, coding the data, assigning categories, themes and sub-themes and then interpreting the data. The data analysis process was guided by the research question.

Trustworthiness

Crystallization was applied to ensure credibility and confirmability (Merriam, 2009; Creswell, 2012). Different data collection methods were used, to ascertain a rich description of the phenomenon under exploration. Themes were only obtained after the data was studied in-depth and then member-checking was also applied to ensure that the participants’ statements and descriptions were appropriately interpreted. The goal of crystallization is not to confirm the accuracy of people’s perceptions or to report the real reflections of a situation, but rather to ensure that the findings relating to people’s perceptions are reflected accurately (Merriam, 2009).

Findings

The factors that were identified as disabling teachers’ self-efficacy are presented and discussed in categories, with relevant main themes and sub-themes. Direct quotations are used to substantiate the categories, themes and sub-themes. The P indicates the participant whose quote was used, S for the school (A or B), F for focus group interview one or two, I for individual interview and C for the collages. For example, SA F1 P1 refers to School A: Focus group: 1 Participant 1 (Table 1).

Lack of knowledge and skills

The sub-themes of this main theme are focused on the experiences of the participants that emanate as a result of having limited knowledge and skills. This was reported by the participants as having a lack of confidence in their own teaching; the teacher as a barrier him/herself; and the psychological and physical problems they experience.

Lack of confidence In teaching

A lack of confidence in teaching within and inclusive education system were experienced by most participants. This was especially evident in the collages where the participants demonstrated negative feelings regarding inclusive education such as “confused and frustrated” (SB C7 P7), and the lack of knowledge “wondering how am I going to do it” (SB C7 P7). Participants clarified this by explaining that they still felt new in the field (inclusive education), had too little knowledge and therefore lacked confidence in their own teaching abilities. This is reflected in the following quote: “Frustrated not knowing exactly what is right, because we are new in the field, and I do not feel confident in my own teaching ability anymore” (SB F2 P3).”

The teacher as barrier

The participants reported that because they felt incompetent and inadequate to address all learners’ needs they experienced an increased sense of failing these learners. This resulted in making them feel like being the barrier themselves, as apparent in the statement:. “I become the barrier, because I do not know to handle all the barriers and I feel like I’m failing my learners, I’m failing at my task to teach” (SA I3 P3). All the participants declared that they are keen to help learners, but despite being willing and attempting to provide support, they still felt incompetent to address diverse needs: “I am trying my very best, I can see that I cannot reach them like they are supposed to be reached you know” (SA F1 P1).

Physical and psychological problems

Participants asserted that their lack of knowledge and skills influenced their mental and physical health negatively. One participant described it as follows: “I do not feel healthy anymore, because I’m failing my learners, I’m failing at my task to be a good teacher” and “I really feel stressed and drained, because I know so little about inclusive education and I do not know what to do for the first time in my life, I always rated myself as a good teacher, but really now my body is giving in, and I think all teachers are very stressed, I mean you can check in every teacher’s handbag there will always be pills and other medication that they need to take for headache or depression continuously to cope” (SB F2 P1).

Disabling factors as influenced by the Department of Basic Education

Factors disabling teachers’ self-efficacy as influenced by the DBE resulted in five sub-themes. These include ineffective implementation of inclusive education; inadequate training; incompetent departmental leaders/managers; a lack of support and acknowledgement; and curriculum constraints.

Ineffective implementation of inclusive education

Most participants revealed that the way in which the Department of Basic Education (DBE) commenced and implemented inclusive education are ineffective. This is summarized in the following statement: “It was not effectively done, we still do not know how to make use of effective inclusion strategies” (SA F1 P4).

Inadequate training

Training was affirmed by all the participants as an important prerequisite for enhancing their sense of self-efficacy since this leads to increased knowledge and skills, which they felt can improve confidence in their own ability. This is reflected in the following assertion of a participant: “When we get enough training we feel more empowered to practice inclusion and therefore we must get more opportunities to go for training.” Nevertheless, it was strongly emphasized that the training they do receive from the DBE was not adequate enough: “the department expects us to implement without proper training” (SB F1 P6).

Incompetent DBE leaders/managers

The participants also mentioned that leaders or managers, for example, the District Based Support Team (DBST), do not always seem competent to provide support. As one participant stated: “Even the districts officials there are those, those who are appointed there not knowing most of the things and if you go to them and you need help, they are unavailable and if you find them they say no you do not do that. She or he will give you the wrong information” (SB F2 P1). This resulted in many participants trying to find information on their own because they believed that they were not given the correct information and as a result it seems that mistrust develops between teachers and District officials. This is affirmed in the following opinion of a participant: “Then you have to go through the documents and you google on your own and then get the correct thing, your facilitator did not tell you the correct thing, so the trust for that person is, you know, not there” (SB F2 P1).

Lack of support or acknowledgement from DBE

All the participants concluded that support from the DBE does not only need to be increased, but needs to be improved. One participant declared: “The department must support us more and the way they are helping should be better” (SA F1 P2). Another one confirmed that an effective support system is needed: “If we can have a support system that is effective within the education system in schools” (SA F2 P1).

Curriculum constraints

The prescribed curriculum assessment policy statements (CAPS) seem to place constraints on the participants to be flexible in their teaching. This frustrates them, because it does not allow time to make modifications for learners who struggle. In addition, continuous curriculum changes that took place from 1997 results in feeling of uncertainty. This is affirmed by one participant’s claim: “Because if they have a system a consistent system you are going to have confidence you can do it. But if the system keeps on changing from time to time, like you see this year we are doing this and then you do CAPS and next time you are doing another thing. I think that there are also a lot of changes if the system is not consistent, it will also cause people not to know exactly what they are doing. Those changes that are coming up from time to time, they also make you as a teacher to unsure of what you are doing” (SB F2 P1).

Disabling factors within the school system

Factors that have been reported as disabling teachers’ self-efficacy from within the school system involved the school management, a lack of support and resources, peer relations, parents and overcrowded classrooms.

School management

Most participants reported a need for acknowledgement, being valued and experiencing trust from the school management team. One participant summarized it as follows: “It’s not easy to be a teacher. But at least if in the management of the school somebody will acknowledge if you put more effort into your work. But normally it is not the situation, under normal circumstances, in very few instances where you will find somebody acknowledging that at least I can see what you are doing” (SB F2 P13).

Lack of support and resources

The participants also emphasized the lack of support which adds to the challenge of implementing inclusive education. One participant commented: “Inclusion is very hard for us when we do not get any support, it really makes your job very difficult we cannot do this on our own” (SB F1 P3). Another participant asserted that they do not have psychologists and other human resources available, as other schools have, which causes negativity toward inclusive education. “And maybe one other thing that makes me to feel this negative about inclusion is about the lack of resources. Because I have seen school who have so many things like psychologies, human resources, which we do not have at our school” (SA F1 P1). Participants reported that help from professionals such as doctors, nurses, psychologist and social workers need to be increased. They explained that inclusion policies require them to work with these health professionals, but asserted that there have to be more of these services available for learners as well as teachers: “The policy says we must work with doctors and professionals to help us with the learners, but there must be more of these available to us for assistance with our job and our personal health” (SB I6 P6).

Peer relations

Peer relations between teachers also seemed to influence teachers’ sense of self-efficacy. Most participants reported that their colleagues who teach with them in the same school were on different paths regarding the implementation of inclusive education. This is evident in the following comment of a participant: “With the school I do not see that we are not on the same path. There are those who understand and mostly, they are still puzzled and confused on how to implement inclusive education. And you know some other thing with their colleagues, some people do not feel free to come and ask or to share ideas if they knew. Some people, you know, he or she decides to just go on with the wrong thing in their classroom” (SA F1 P1). These different paths made the participants feel that they are working in isolation which creates a negative attitude as well as demotivation to implement inclusive education. One participant explained: “A colleague working in isolation and functioning in his own world and who do not share the common world philosophy belief with other teachers, it makes us negative discouraged” (SA F2 P3). It was also emphasized by other participants in the following statements: “We have to realise that we need each other to be better teachers, to grow personally, to improve our education in South Africa and inclusion for all. You cannot just do it on your own” and “As a teacher I must play my cards openly not closed you are going to be there to share and gain knowledge and will make me mature as a teacher” (SA F2 P14).

Parents

Parental involvement also clearly stood out as a problem as evident in the following affirmation: “We really need the parents to be part of the learners’ education” (SB I6 P6). Participants asserted that parents are uninvolved and do not attend parent meetings. This is confirmed in statements such as: “That’s the other thing. With parents I’m so glad that the department of education took it further that they need to involve parents. I do not know why but they are still not giving us their participation” (SA F1 P3). When learners display behavior and discipline problems, participants particularly expressed that they need the support of parents. However, it was also acknowledged by the participants that parent support is a complex issue. Where parents are deceased, grandparents take care of the children or parents working long hours leave their children with unrelated caregivers.

Overcrowded classrooms

Overcrowded classes have been emphasized as a major cause of adding to the participants feeling ineffective, because they feel they cannot give attention to all the learners. One participant commented: “Eh, I think the other problems we are facing as teacher is the ratio, the learner ratio between the teachers, you find that in some classes it is 1 is to 60, the teacher has to teach 60 learners in one class so that is impossible to give your full notice to all and it’s also a factor that is contributing maybe a lack of our effectiveness” (SB F1 P2).

Other discouraging external factors

External factors that discouraged teachers’ self-efficacy that were identified included the media and disrespect as well as false perceptions by society.

Negative influences from media

Continuous negative comments by the media instead of recognizing important contributions of teachers’ work and effort, demotivated the participants. This is evident in the following statement: “Sometime the media always criticises teachers, when they talk about the negative things about the teachers, how, they make it on the front page, and so they are demotivating us as educators. So most of the time they do not show the quality things, they always show negative things that have been done by the teachers, the quality one is always at the back, they are hiding, but the good ones, ah the bad ones, so when you look at the media always it see negative things about the teacher, you become demotivated so we need positive affirmation” (SB F1 P3).

Disrespect and false perceptions By society

Fallacious perceptions by society in general about teachers as mentioned by one participant: “teaching is an easy course or a half day job” appear to demoralize the participants and make them feel as if they are “not trusted and respected by the community, learners or country.” The following participant affirmed that: “it is like our profession is nothing, why cannot they change their perception of teachers and realise that it is a full time, 24 h job, because you always take work home” (SB F2 P4).

Discussion

It seems evident from the findings that there are certain critical factors resulting in disabling Full-Service school teachers’ sense of self-efficacy in teaching within an inclusive FSS.

Inclusive education has globally brought about new teaching requirements and changes. Classrooms now have a wider range of diverse learning needs (including learners who experience barriers to learning and disabilities) and this impacts significantly on classroom practice as well as on teachers’ themselves and how they perceive their own sense of self-efficacy (Savolainen et al., 2012; Sharma et al., 2012; Savolainen et al., 2022). This appears to be especially applicable to the FSS’s where this study was conducted. During the time of the research all the participants in these schools had their pre-service teacher education before inclusive education was introduced and therefore had no formal initial teacher education training on inclusive education and teaching learners who experience barriers to learning. Since the introduction of EWP6 in 2001 they were only exposed to afternoon workshops, presented by the DBE. Yet they are required to teach in a fully inclusive FSS. The frustration of the participants is reflected in their statements in which they acknowledge their lack of understanding (what inclusive education is all about) and limited knowledge and skills as a result of inadequate training to deal with all the new challenges that an inclusive teaching environment created. This seems to impact negatively on their confidence, resulting in progressive feelings of incompetence, in being able to teach learners with a diversity of needs in one classroom. Feeling confident and competent as teachers are important features of a positive sense of self-especially within the context of the challenges the participants mentioned in this research. Adequate content knowledge and teaching skills will lead to improved teaching performance and to a more confident perception of one’s own competence, which is necessary for effective teaching in an inclusive classroom (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2009).

A key disabling factor identified in this study is that the participants’ feelings of incompetence to address all learners’ needs makes them believe that they are failing the learners and are consequently the barrier to the learners’ successful learning. Other research studies (Wood and Olivier, 2010; Memisevic et al., 2021; Van Mieghem et al., 2022), conducted with teachers also identified feelings of fear, frustration, negativity and failure about their own ability to deal with disabilities which they then believed lead to lower academic standards. Thus, giving urgent attention to teachers in FSS’s feelings of incompetence is critical as it can lead to a decreased capacity to perform, reduced efficiency, as well as poor health, mental and physical wellbeing and ultimately to a low sense of self-efficacy (Shulman, 2013; El-Sayed et al., 2014; Lynch, 2019).

The ineffective management of the DBE in implementing inclusive education has been asserted as disabling the participants sense of self-efficacy teaching in a FSS. This finding is supported by other studies and reports that have shown that the implementation of inclusive education remains a challenge in South Africa. This has been contributed to a lack of adequate training, insufficient resources and unsatisfactory support services [e.g., Department of Basic Education (DBE), 2015; Makhalemele and Nel, 2016, 2021; Equal Education Law Centre (EELC), 2021].

Although in-service training workshops regarding inclusive education have been and still is provided by the DBE the participants deemed this as inadequate to effectively prepare them for the implementation of inclusive education. The participants asserted that they need more workshops on how to identify and support learners with different barriers to learning and development. Other studies confirm that in-service training programs are not sufficient for teachers to be fully equipped with knowledge on inclusive education, as well as practical skills on how to address a diverse range of barriers by for example being able to differentiate the curriculum and using a variety of instructional strategies (International Disability and Development Consortium (IDDC), 2013; Spaan et al., 2022; Wray et al., 2022). Ross-Hill (2009) asserts that not offering frequent and substantial training brings about tension, stress, and strain for teachers in inclusive settings. Moreover, the participants recommended that the workshops should be a more interactive learning experience, instead of the presenters’ only reading from notes. In addition, a need for more practical demonstrations in place of only providing documents and expecting teachers to read it on their own, was asserted by the participants. Interactive learning is well-documented as a strategy to increase confidence in one’s own capabilities (Roldán et al., 2021).

Incompetent Department of Basic Education (DBE) officials were mentioned as a source of frustration and demotivation for the participants, preventing them from being successful in the implementation of inclusive education. The District Based Support Teams (DBST) was specifically reported as not providing adequate and sufficient support to teachers to assist them with learners who experience barriers to learning. It seems that the participants felt that the DBST members lack knowledge about inclusion. This results in them not trusting the DBST to provide adequate support and build their capacity in being efficient inclusive teachers. These findings are supported by other studies, namely Makhalemele and Nel (2016, 2021), as well as Nel et al. (2016), who found that many DBST’s and School Based Support Teams (SBST) are not functioning efficiently. Furthermore, limited available professional support services such as psychologists and other health professionals frustrate the participants. They asserted a dire need for the availability of such human resources, since they believe they are not able to provide all the expert support that some disabilities require. This seems to add to teachers’ feelings of demotivation and despondency, affecting their sense of self-efficacy.

In addition to the participants not receiving sufficient support from departmental officials, they also indicated that their work and achievements are not acknowledged by their own school management team. The participants felt that they needed to be more individually recognized for their qualities and contributions to teaching and conveyed that in many instances they do not receive the credit that that they deserve from the school management. Ting and Yeh (2013) found that when given gratitude, it has positive effects on teachers’ trust, satisfaction and commitment, but not being appreciated result in teachers feeling neglected, demotivated and dissatisfied in their job. Another concern mentioned by the participants, with regard to senior personnel at the school, is that they are not competent to deal with inclusive education, and consequently their management thereof is not acceptable. Causton and Theoharis (2013) confirm that incompetent leaders can destructively affect teachers’ performance. Contrary, when management teams are well-qualified, teachers seem to feel more trusted and secure in their work (Wahlstrom, 2008). This was apparent when one participant mentioned she respected her principal more because of his post graduate qualification. She supposed that this made him more knowledgeable. The Human Science Research Council [Human and Social Science Research Council (HSRC), 2005] found that these kinds of systemic practices where teachers’ are not acknowledged are some of the main reasons why they want to leave the system. Consequently, effective, competent and supportive leaders and managers are key dimensions in ensuring that teachers will experience a sense of self-efficacy in an inclusive classroom (Savolainen and Häkkinen, 2011).

It emerged from the findings that the participants’ sense of self-efficacy appears to also be affected negatively by continuously changing curriculums, as well as the curriculum constraints that are placed on them. Lilyquist (2013) confirms that ever-changing expectations result in teachers feeling confused. Current curriculum constrictions, such as prescriptive requirements for completion of the curriculum (CAPS) and limited flexibility (with regard to time frames and lesson plans) are emphasized by the participants as limiting them from addressing diverse learning needs. These concerns are confirmed in research by Booysen (2018) and Engelbrecht et al. (2017) which found that a prescriptive approach to policy requirements restricts teachers from being flexible to address their own learners’ context and needs. A key principle of inclusive education is that curriculum implementation should be flexible with regard to teaching methods, assessment, and pace of teaching, as well as the development of learning material (Department of Education (DoE), 2001). The pressure to complete the curriculum (also called “curriculum coverage” by the participants) within certain time limits constrain teachers to thoroughly address learners’, who experience barriers to learning, needs (Msibi and Mchunu, 2013).

A lack of resources was reported as a major factor that disable teachers in their attempts to implement inclusive education effectively. The absence of resources such as adapted physical facilities for learners with physical disabilities or teaching aids for learners with visual, hearing or learning impairments, as well as appropriate learning material, place an extra burden on teachers and could create stress for both the learner and the teacher in an inclusive classroom.

Teacher colleagues who do not share the same positivity and passion about inclusive education made the participants feel negative, demotivated and as if they are working in isolation. They felt that better cooperation between colleagues in terms of planning and sharing personal experiences would be developmental and enhance self-efficacy. Maika (2012), as well as Romi and Leyser (2006), affirm that when peers at the same school are on different paths regarding a variety of implementation issues, it can result in teachers feeling isolated and negative. Pajares (2009) explains that teachers’ self-efficacy can be positively or negatively influenced by the behavior of colleagues who teach with them. If one teacher colleague is, for instance, negative about inclusion, there is a strong possibility that he/she can cause the same reaction or attitude among other teachers that he/she is working closely with (Igbokwe Uche et al., 2014). Furthermore, teachers who are working together, but do not share common ideas, creates separation, which can lead to individual functioning (Robbins, 2005). However, healthy collaborative partnerships will lead to improved teacher self-efficacy, since a sense of support and interdependency is created (Romi and Leyser, 2006; Maika, 2012). Yet, the participants suggested, for this to materialize opportunities have to be purposefully created where teachers could talk and interactively learn from one another. Interactive interpersonal opportunities can involve open discussions where teachers talk and effectively learn from one another, where strengths in one another are identified, and encouragement from other colleagues is given and received. This could contribute to personal development and the enhancement of self-efficacy.

Parents’ lack of involvement has also been reported as having a disabling influence in teachers feeling less self-efficient. Active involvement of parents in the teaching and learning process of their children is fundamental to effective learning and development (Sapungan and Sapungan, 2014). The lack thereof places an enormous load on teachers in addressing the needs of learners, especially when they experience barriers to learning. Ting and Yeh (2013) found that gratitude from parents to teachers is an essential component in building relationships and effective teaching.

Overcrowded classrooms are seen by the participants as an elemental factor in disabling teachers’ self-efficacy to effectively implement inclusive education. South African school classrooms are overpopulated (Matsepe et al., 2019). It is consequently difficult for teachers to manage class discipline, while also dealing with every learner’s learning needs. The participants reported that in order to support learners who experience barriers to learning, they will give these learners more attention and as a result neglect the other learners. They will then feel as if they themselves are the barrier to those learners who learn faster.

Discouraging external factors, such as the media and society, were also asserted as factors disabling the participants’ self-efficacy. They felt that the media and general society mostly criticize teachers instead of recognizing the important contributions they are making in the education of learners. This adds to a feeling of demotivation. The participants reported that the media shape a misleading impression of teachers and this makes teachers feel under-appreciated. Disrespectful and false perceptions by the society, such as a disregard for teaching as a profession, viewing teaching as an easy course leading to a half day job also made the participants feel as if they were not trusted by the community. Aspfors et al. (2019) confirm that teachers are feeling that their jobs are not considered a profession. It was emphasized by the participants that it seems as if teachers, instead of the system, are mainly and unfairly blamed by society for everything that goes wrong in education when learners do not perform well on an academic level. It is affirmed by Perold et al. (2012) that South African teachers widely receive negative media publicity and is often held responsible for the failure of educational inventions, which are displayed in the underperformance of learners. Yan (2009) declares that negative statements from the media as well as destructive perceptions from society, are primary causes of teacher demotivation.

Conclusion

Education White Paper 6 affirmed that teachers need to play a central role in ensuring that inclusive education is successfully implemented in South Africa (Department of Education (DoE), 2001). Thus, teachers having a positive sense of self-efficacy is essential to ensure that a FSS functions effectively and fully as an inclusive school, as it is intended to. However, it is evident from the findings of this study that there are several factors that seem to disable their sense of self-efficacy, some of which is external and others internal. The external factors (such as inadequate training, the ineffective functioning of the department of basic education, the school management team not being supportive and competent, curriculum constraints, poor involvement of parents, limited and inadequate resources, large classroom numbers and even the media) appear to be mostly systemic. It can be assumed that all these external factors mentioned by the participants are directly linked to the education department’s struggle to ensure a fully and efficient functional inclusive education system. A plethora of studies (e.g., Schoeman, 2012; Douglas et al., 2021; Walton and Engelbrecht, 2022, etc.) and official reports (e.g., Department of Basic Education (DBE), 2015) highlighted that the South African education system have not yet achieved the goal of EWP6 (Department of Education (DoE), 2001) to foster the development of inclusive and supportive centers of learning for all learners, especially in FSS. Thus, these external systemic factors reportedly disabling teachers’ sense of self-efficacy could have a serious negative effect on their sense of agency. A central premise of Bandura’s self-efficacy theory is that persons strive for a sense of agency, or the belief that they can control a significant degree of influence over important events in their lives (Schunk and DiBenedetto, 2020).

Consequently, within the afore-mentioned challenging education environment, over which FSS teachers feel that they have little control, an enormous responsibility is placed on their shoulders to be successful and efficient in addressing a range of learning needs in one classroom and support learners who experience barriers to learning, while trying to develop and sustain a positive sense of self-efficacy. The impact thereof is seen in the internal factors reported by the participants as disabling their sense of self-efficacy. These include being on different paths than peers resulting in them feeling isolated, a lack of knowledge and skills, a lack of confidence in their own teaching, and they even went as far as seeing themselves as a barrier to learners’ progress, as well as experiencing physical and psychological problems. These mentioned internal disabling factors are critical to take note of as it influences the self-perceptions that teachers hold about their capabilities to learn or to perform courses of action at designated levels (Pajares, 2009). Bandura (2006) affirmed that efficacy beliefs determine how environmental opportunities and obstacles are perceived, affecting the choice of activities, how much effort is expended on an activity, and how long people will persevere when confronting stumbling blocks.

It is therefore vital that the basic and higher education departments of education are aware of the identified disabling factors and purposefully improve the external, systemic factors, while ensuring that FSS teachers’ capabilities are developed and sustained in in-service and pre-service teacher education. This could contribute to developing and improving their sense of self-efficacy, but importantly also their physical and psychological wellbeing. Increasing growth and belief in capabilities while developing positive thinking patterns will augment self-confidence and the ability to control the surrounding environment. This could assist in carrying out daily pressures with more confidence and belief in oneself which tend to lead to improved psychological well-being (Alkhatib, 2020).

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. This data can be found at: https://repository.nwu.ac.za/handle/10394/16540.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Human and Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

IVS-P wrote the article and collected the data. MN co-wrote and edited the article. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alkhatib, M. A. H. (2020). Investigate the relationship between psychological well-being self-efficacy and positive thinking at prince Sattam bin Abdulaziz university international. J. High. Educ. 9, 138–152. doi: 10.5430/ijhe.v9n4p138

Aspfors, J., Eklund, G., and Hansén, S. E. (2019). Early career teachers’ experiences of developing professional knowledge - from research-based teacher education through five years in the profession. Nordisk Tidskrift för Allmän Didaktik 5, 2–18.

Association for Qualitative Research. (2012). Objectivity in Qualitative Research. Cambridge, UK: Davey House.

Ayaya, G., Makoelle, T. M., and Van Der Merwe, M. (2021). Developing a framework for inclusion: a case of a full-service school in South Africa. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Educ., 1–19. doi: 10.1080/09518398.2021.1956616

Bandura, A. (1994). “Self-efficacy” in Encyclopaedia of Human Behavior. ed. V. S. Ramachaudran (New York, NY: Academic Press), 71–81.

Bandura, A. (2006). “Guide for constructing self-efficacy scales” in Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents. eds. F. Pajares and T. Urdan (Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing), 307–337.

Booysen, R. M. (2018). The perspectives of secondary school teachers regarding the flexible implementation of the curriculum assessment policy statement. Unpublished Master’s dissertation. Vanderbijlpark: North-West University.

Butler-Kisber, L., and Poldma, T. (2010). The power of visual approaches in qualitative inquiry: the use of collage making and concept mapping in qualitative research. J. Res. Pract. 6:Article M18

Causton, J., and Theoharis, G. (2013). The Principal’s Handbook for Leading Inclusive Schools . Baltimore: Paul H Brookes Publishing.

Clipa, O. (2017). “Teacher stress and coping strategies” in Studies and current trends in science of education. ed. O. Clipa (Suceava, Romania: LUMEN Proceedings), 120–128.

Cobern, W. W., and Adams, B. A. J. (2020). When interviewing: how many is enough? Int. J. Assess. Tools Educ. 7, 73–79.

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational Research: Planning, Conducting and Evaluating Quantitative and Qualitative Research. 4th Edn. New York, NY: Pearson. 673 p.

Crothers, L. M., Hughes, T. L., and Morine, K. A. (2008). Theory and Cases in School-Based Consultation: A Resource for School Psychologists, School Counsellors, Special Educators, and Other Mental Health Professionals. London, United Kingdom: Routledge.

De Oliviera Fernandez, A. P., Ramos, M. F. H., Costa e Silva, S. S., Fernando, K. C. F. N., and Pontes, A. R. (2016). Overview of research on teacher self-efficacy in social cognitive perspective. Anales de psicología 32, 793–802. doi: 10.6018/analesps.32.3.220171

Department of Basic Education (DBE). (2015). Report on the Implementation of Education White Paper 6 on Inclusive Education: An Overview for the Period 2013–2015. Pretoria: Sol Plaatjie House.

Department of Education (DoE). (2001). Education White Paper 6: Special Needs Education (Building an Inclusive Education and Training System). Pretoria: DoE.

Devi, A., and Ganguly, R. (2022). Pre-service teachers’ and recent teacher graduates’ perceptions of self-efficacy in teaching students with autism Spectrum disorder – an exploratory case study. Int. J. Incl. Educ., 1–17. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2022.2088869

Douglas, A., Walton, E., and Osman, R. (2021). Constraints to the implementation of inclusive teaching: a cultural historical activity theory approach. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 25, 1508–1523. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2019.1620880

El-Sayed, S. H., El-Zeiny, H. H. A., and Adeyemo, D. A. (2014). Relationship between occupational stress, emotional intelligence, and self-efficacy among faculty members in faculty of nursing Zagazig University, Egypt. J. Nurs. Educ. Pract. 4, 183–194. doi: 10.5430/jnep.v4n4p183

Engelbrecht, P., Savolainen, H., Nel, M., Koskela, T., and Okkolin, M.-A. (2017). Making meaning of inclusive education: classroom practices in Finnish and south African classrooms. Compare: J. Comp. Int. Educ. 47, 684–702. doi: 10.1080/03057925.2016.1266927

Equal Education Law Centre (EELC). (2021). A 20-year review of the regulatory framework for inclusive education and its implementation in South Africa. EELC. Available at https://eelawcentre.org.za/wp-content/uploads/ie-report-let-in-or-left-out.pdf

Griful-Freixenet, J., Struyven, K., and Vantieghem, W. (2021). Exploring pre-service teachers’ beliefs and practices about two inclusive frameworks: universal Design for Learning and differentiated instruction. Teach. Teach. Educ. 107:103503. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2021.103503

Guskey, T. R., and Passaro, P. D. (2012). Teacher efficacy: a study of construct dimensions. Am. Educ. Res. J. 31, 627–643. doi: 10.3102/00028312031003627

Human and Social Science Research Council (HSRC). (2005). The health of our educators: a focus on HIV/AIDS in south African public schools. Report to ELRC. Centurion: Human Science Research Council.

Igbokwe Uche, L., Mezieobi, D. I., and Callistus, N. E. (2014). Teachers’ attitude to curriculum change: Implications for inclusive education in Nigeria. Res. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 4, 92–100.

International Disability and Development Consortium (IDDC). (2013). Teachers for All: Inclusive Teaching for Children with Disabilities. Available at: https://www.eenet.org.uk/resources/docs/IDDC_Paper_Teachers_for_all.pdf

Klassen, R. M., and Chiu, M. M. (2010). Effects on teachers’ self-efficacy and job satisfaction: teacher gender, years of experience, and job stress. J. Educ. Psychol. 102, 741–756. doi: 10.1037/a0019237

Kosko, K. W., and Wilkins, L. M. (2009). General educators’ in-service training and their self-perceived ability to adapt instructions for students with IEPs, Virginia Polytechnic Institute & State University Teacher Training and inclusion. Prof. Educ. 33, 1–10.

Lilyquist, J. G. (2013). Are Schools Really Like This? Factors Affecting Teacher Attitude Toward School Improvement. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media, 91.

Liu, X., Peng, M. Y. P., Answer, M. K., Chong, W. L., and Lin, B. (2020). Key teacher attitudes for sustainable development of student employability by social cognitive career theory: the mediating roles of self-efficacy and problem-based learning. Front. Psychol. 11:1945. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01945

Lynch, M. (2019). How bad education policies demoralize teachers. The Edvocate. Available at: https://www.theedadvocate.org/how-bad-education-policies-demoralize-teachers/

Maika, K. (2012). Teacher self-efficacy and successful inclusion: Profiles and narratives of eight teachers. MEd-of Art: Thesis. Canada: Concordia University.

Makhalemele, T., and Nel, M. (2016). Challenges experienced by district-based support teams in the execution of their functions in a specific south African province. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 20, 168–184. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2015.1079270

Makhalemele, T., and Nel, M. (2021). Investigating the effectiveness of institutional-level support teams at full-service schools in South Africa. Support Learn. 36, 296–315. doi: 10.1111/1467-9604.12356

Matsepe, D., Maluleke, M., and Cross, M. (2019). Re-imagining teacher’s experience with overcrowded classrooms in the public secondary schools in South Africa. J. Gender Inf. Dev. Africa (JGIDA) 8, 91–103.

McMillan, J., and Schumacher, S. (2014). Research in Education Evidence-Based Inquiry. (7th Ed.). Essex: Pearson Ltd.

Memisevic, H., Dizdarevic, A., Mujezinovic, A., and Djordjevic, M. (2021). Factors affecting teachers' attitudes towards inclusion of students with autism spectrum disorder in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Int. J. Incl. Educ., 1–17. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2021.1991489

Merriam, S. B. (2009). Qualitative Research: A Guide to Design and Implementation. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. 293 p.

Msibi, T., and Mchunu, S. (2013). The knot of curriculum and teacher professionalism in post-apartheid South Africa. Educ. Change 17, 19–35. doi: 10.1080/16823206.2013.773924

Nel, M. (2020). Inclusive and special education in Africa. Oxford Research Encyclopaedia. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nel, M., Nel, N. M., and Hugo, A. (2022). “Inclusive education: an introduction” in Learner Support in a Diverse Classroom. eds. M. Nel, N. M. Nel, and M. Malindi (Pretoria: Van Schaik), 3–40.

Nel, N. M., Tlale, L. D. N., Engelbrecht, P., and Nel, M. (2016). Teachers' perceptions of education support structures in the implementation of inclusive education in South Africa. KOERS—Bull. Christian Scholarsh. 81, 17–30. doi: 10.19108/KOERS.81.3.2249

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2009). Creating Effective Teaching and Learning Environments: First Results from TALIS. OECD Publishing. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/education/school/43023606.pdf

Pajares, F. (2009). “Toward a positive psychology of academic motivation: the role of self-efficacy beliefs” in Handbook of Positive Psychology in Schools. eds. R. Gilman, E. S. Huebner, and M. J. Furlong (New York: Taylor & Francis), 149–160.

Perold, M., Oswald, M., and Swart, E. (2012). Care, performance and performativity: portraits of teachers’ lived experiences. Educ. Change 16, 113–127. doi: 10.1080/16823206.2012.692208

Prinsloo, E., and Gasa, V. (2016). “Addressing challenging behaviour in the classroom” in Addressing barriers to learning: A South African perspective. eds. E. Landsberg, D. Kruger, and E. Swart. 3rd edn (Pretoria: Van Schaik), 543–564.

Robbins, S. P. (2005) Essentials of organizational behavior. 8th Edition, Pearson Education Inc., Prentice Hall.

Roldán, M. S., Marauri, J., Aubert, A., and Flecha, R. (2021). How inclusive interactive learning environments benefit students without special needs. Front. Psychol. 12:661427. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.661427

Romi, S., and Leyser, Y. (2006). Exploring inclusion pre-service training needs: a study of variables associated with attitudes and self-efficacy beliefs. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 21, 85–105. doi: 10.1080/08856250500491880

Ross-Hill, R. (2009). Teacher attitudes towards inclusion practices and special needs students. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 9, 188–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-3802.2009.01135.x

Ryan, A., and Mathews, E. S. (2022). Teacher self-efficacy of primary school teachers working in Irish ASD classes. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 37, 249–263. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2021.1872996

Sapungan, G. M., and Sapungan, R. M. (2014). Parental involvement in child’s education: importance, barriers and benefits. Asian J. Manag. Sci. Educ. 3, 42–48.

Savolainen, T., and Häkkinen, S. (2011). Trusted to lead: trustworthiness and its impact on leadership. Technology innovation. Manag. Rev.

Savolainen, H., Engelbrecht, P., Nel, M., and Malinen, O.-P. (2012). Understanding teachers’ attitudes and self-efficacy in inclusive education: Implications for pre-service and in-service teacher education. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 27, 51–68. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2011.613603

Savolainen, H., Malinen, O. P., and Schwab, S. (2022). Teacher efficacy predicts teachers’ attitudes towards inclusion – a longitudinal cross-lagged analysis. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 26, 958–972. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2020.1752826

Schoeman, M. (2012). “Developing an inclusive education system: changing teachers’ attitudes and practices through critical professional development” in Paper presented at the National Teacher Development Conference at the University of Pretoria, 17–19.

Schunk, D. H., and DiBenedetto, M. K. (2020). Motivation and social cognitive theory. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 60:101832. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2019.101832

Sharma, U., Loreman, T., and Forlin, C. (2012). Measuring teacher efficacy to implement inclusive practices. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 12, 12–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-3802.2011.01200.x

Shulman, R. (2013). Unhappy and exhausted teachers: How and why everyone is affected. EdNews Daily. Available at: http://www.ednewsdaily.com/unhappy-and-exhausted-teachers-how-and-why-everyone-is-affected/.

Skaalvik, E. M., and Skaalvik, S. (2010). Teacher self-efficacy and teacher burnout: a study of relations. Teach. Teach. Educ. 26, 1059–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2009.11.001

Spaan, W., Oostdam, R., Schuitema, J., and Pijls, M. (2022). Analysing teacher behaviour in synthesizing hands-on and minds-on during practical work. Res. Sci. Technol. Educ., 1–18. doi: 10.1080/02635143.2022.2098265

Temiz, T., and Topcu, M. S. (2013). Preservice teachers' teacher efficacy beliefs and constructivist-based teaching practice. Eur. J. Psychol. Educ. 28, 1435–1452. doi: 10.1007/s10212-013-0174-5

Ting, S. C., and Yeh, L. Y. (2013). Teacher loyalty of elementary schools in Taiwan: the contribution of gratitude and relationship quality. School Leadersh. Manag. 34, 85–101. doi: 10.1080/13632434.2013.813453

Van Mieghem, A., Struyf, E., and Verschueren, K. (2022). The relevance of sources of support for teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs towards students with special educational needs. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 37, 28–42. doi: 10.1080/08856257.2020.1829866

Van Schalkwyk, G. J. (2010). Collage life story elicitation technique: a representational technique for scaffolding autobiographical memories. Qual. Rep. 15, 675–695. doi: 10.46743/2160-3715/2010.1170

Wahlstrom, K. L. (2008). How teachers experience principal leadership: the roles of professional community, trust, efficacy, and shared responsibility. Educ. Adm. Q. 44, 458–495. doi: 10.1177/0013161X08321502

Walton, E., and Engelbrecht, P. (2022). Inclusive education in South Africa: path dependencies and emergences. Int. J. Incl. Educ., 1–19. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2022.2061608

Wood, L., and Olivier, T. (2010). Increasing the Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Life Orientation Teachers: An Evaluation. Port Elizabeth: Faculty of Education Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, 161–179.

Wray, E., Sharma, U., and Subban, P. (2022). Factors influencing teacher self-efficacy for inclusive education: a systematic literature review. Teach. Teach. Educ. 117:103800. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2022.103800

Yan, H. (2009). Student and teacher de-motivation in SLA. Asian Soc. Sci. 5, 109–112. doi: 10.5539/ass.v5n1p109

Zee, M., and Koomen, H. M. Y. (2016). Teacher self-efficacy and its effects on classroom processes, student achievement adjustment, and teachers well-being: a synthesis of 40 years of research. Rev. Educ. Res. 86, 981–1015. doi: 10.3102/0034654315626801

Keywords: teachers, self-efficacy, inclusive education, disabling factors, social-cognitive theories

Citation: Van Staden-Payne I and Nel M (2023) Exploring factors that full-service school teachers believe disable their self-efficacy to teach in an inclusive education system. Front. Educ. 7:1009423. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1009423

Edited by:

Maxwell Peprah Opoku, United Arab Emirates University, United Arab EmiratesReviewed by:

Mahlapahlapana Themane, University of Limpopo, South AfricaInmaculada Orozco, University of Seville, Spain

Edda Óskarsdóttir, University of Iceland, Iceland

Copyright © 2023 Van Staden-Payne and Nel. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mirna Nel, ✉ TWlybmEuTmVsQG53dS5hYy56YQ==

Isabel Van Staden-Payne

Isabel Van Staden-Payne Mirna Nel

Mirna Nel