- Cambridge Centre for Sport and Exercise Sciences (CCSES), School of Psychology and Sport Science, Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge, United Kingdom

The first year of higher education (HE) marks one of the most significant transitions in a student’s life. Within the U.K., the subject area of Sport and Exercise Science (SES) has a problem with effectively supporting and retaining students as they transition into HE. If students’ capabilities to successfully transition are to be fully understood and resourced, it is necessary for research to foreground students’ lived realities. Utilising letter to self-methodology, 58 s- and third-year undergraduate SES students wrote to their younger self, providing guidance on how to successfully transition into HE. Data were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis. Six themes and four sub-themes were identified. Following the development of a single composite version of an “Older, wiser self letter” to represent the identified themes, this resource was integrated into the institution’s pastoral care resources and sessions where personal tutors connected with their tutees. Student member reflections were completed to gather feedback regarding the resource’s effectiveness. The composite letter provides an authentic account of how to face obstacles encountered as students transition into HE. Students’ member reflections highlighted that the letter was a valuable resource as a prompt for discussion regarding their experiences of transitioning into HE. When in the student journey the letter was read was particularly important. The value of this composite letter lies in the implementation of tutor-tutee and student peer-peer conversations at key “moments” throughout their journey in HE, helping students understand the challenges and opportunities for success during transition.

Introduction

With students required to develop new academic skills, whilst simultaneously acquiring new social skills and adapting to their role as an independent learner in a cultural setting different to what they may know, it is not surprising that the first year of higher education (HE) marks one of the most significant transitions in a student’s life (Beasley and Pearson, 1999).

Successful transition into HE has been identified as reducing the likelihood of dropout, and students’ initial weeks of HE are considered key for this success (Wilcox et al., 2005; Coertjens et al., 2017; Tett et al., 2017). To facilitate transition, targeted support, typically in the form of “induction activities,” occurs on the students’ first day or week. The specifics of each induction differ across institutions, however, activities commonly focus on preparing students academically (Hultberg et al., 2008) and socially (Brooman and Darwent, 2014) for the requirements ahead, enabling students to settle quickly and effectively (Coertjens et al., 2017).

Whilst induction activities are often valuable in enabling students to transition into HE (e.g., Ackermann, 1991; Cabrera et al., 2013), several authors suggest that transition should be viewed as a more fluid and enduring component of the learning experience, something to be regarded as a longer process throughout the first year (e.g., Pennington et al., 2018). According to this perspective, “student” is not something one is by default, but something one becomes through a complex learning process, requiring navigation of ongoing, context-specific, social situations occurring throughout the first year in HE. It requires getting to know the place, practises, and knowledge of that specific culture or study environment (Gregersen et al., 2021), which can only be achieved through choosing to engage in teaching and learning activities, or in extra-curricular activities, to understand the subtext of the culture they are expected to be part of and form a sense of their student identity (Leese, 2010).

Both Tinto’s model of social integration (1975) and Nicholson’s transition cycle (1990) provide a valuable theoretical foundation with which to conceptualise student transition into HE. According to Tinto’s model, students become socially integrated through meaningful social interactions, the development of relationships with like-minded peers, teachers and university staff, and engaging with extra-curricular activities (Naylor et al., 2021). The model describes how the initial commitment a student demonstrates to their program and institution is influenced by a number of individual characteristics (e.g., family background, personal attributes, previous academic performance and family encouragement). These commitments are continually modified by the students’ interactions with the social and academic systems of the institution (Fincham et al., 2021). Students who demonstrate delayed or minimal commitment, limit their integration and subsequently increase their risk of drop out (Hadjar et al., 2022). It is only through academic performance and academically purposive interactions between peers and teachers that they [the students] also becomes academically integrated (Naylor et al., 2021).

Whilst Tinto (1975) describes transition as a linear concept, with students successfully transitioning into HE following social – and then academic – integration, Nicholson (1990) presented transition as a cyclical model, which consists of four stages: preparation, encounter, adjustment, and stabilisation. The preparation phase requires students to achieve, prior to entering HE, a state of readiness, developing precise and realistic expectations and being positively motivated to change (De Clercq et al., 2018). Similarly described in Tinto’s model, where individual characteristics influence the student’s initial commitment, these characteristics will influence how students experience the preparation phase and potential to progress to the encounter phase. Encounter denotes the ability to adjust initial beliefs, knowledge and perceptions to the actual academic context and to achieve this, students need to acquire a sense of one’s ability to cope, undertake the challenge of sense-making, and forge links with others (Nicholson, 1990). The adjustment phase referred to the student’s ability to regulate the self through personal change and role development, cementing their adaptation to the new environment. Both encounter and adjustment phases resonate with the social and academic integration highlighted in Tinto’s model of social integration (1975). However, an important distinction should be made. Tinto (1975) delineated between social and academic integration, with social integration required to be achieved before academic integration can occur. Nicholson (1990) does not delineate between the two areas of integration and instead highlights how the encounter phase sees students (in the initial weeks) make “links” with others and “make sense of their new environment” and when entering the adjustment phase begin to forge “relationships” (presumably deeper and more meaningful “links”) and understand how they fit within their environment (De Clercq et al., 2018). Finally, stabilisation happens when students experience broadly what kind of behaviour leads to satisfying social and academic outcomes (Nicholson, 1990).

If students’ capabilities to navigate change and transition into HE are to be fully understood and resourced, it is necessary for research to foreground students’ lived realities (Gale and Parker, 2014) and increase the current understanding by considering students’ own perspective (Maunder et al., 2013). The aim of the current study was twofold: firstly, to understand which aspects support or hinder the experience of transition into HE; secondly, to develop a resource which can be used with students to support such transition.

The current study deliberately focuses on only capturing the lived experiences of Sport and Exercise Science (SES) undergraduate students for two reasons. When students enter HE, they are not only faced with understanding the wider university culture in which they operate (Beasley and Pearson, 1999), but the culture of their specific study programme, and this requires getting to know the place, practises, and knowledge of that particular environment (Beasley and Pearson, 1999; Gregersen et al., 2021). Due to cultural differences across study programmes (Ulriksen et al., 2017), it was necessary to ensure that the lived experiences gathered from the students was specific to the context of their culture. Second, whilst student retention has long been identified as a concern in HE (Wilson et al., 2016), the SES subject area is particularly poor, having recently been ranked second lowest across 34 subjects in terms of students projected to obtain a degree (Office for Students [OfS], 2021). The project sought to understand what could support students to successfully transition into HE, make the most out of their degree and avoid setbacks by examining the advice they would give their younger self upon starting University.

Materials and methods

In line with the aim of understanding students’ experiences, the present study was underpinned by an interpretivist paradigm, with a relativist ontology (i.e., psychosocial reality is multiple and mind-dependent) and a social constructionist epistemology (i.e., knowledge is co-constructed; Sparkes and Smith, 2013). The study was developed over two phases.

Phase 1

A narrative inquiry approach was deemed appropriate to answer our research question. Narrative inquiry is a research tradition that focuses on personal experience stories and uses a variety of methods to allow narrators to convey their accounts (Papathomas, 2016). Our chosen method of data collection was that of solicited letter writing (Day et al., 2022), specifically the “Older, Wiser Self Letter” (Dolan, 1991). Kress et al. (2011) described letter writing as an activity that allows problems to be externalised, encouraging reflection and providing an opportunity to learn from experience.

Procedure

Following University ethical approval, all second (L5, 69 students) and third year (L6, 55 students) SES students were invited to participate in Phase 1 of the study during the first week of teaching commencing in 2018/9. Students were provided with an information sheet, which explained the study, and the third author was available to clarify doubts. Overall, 58 letters were collected, 28 were from L5 students (males = 15; females = 13), and 30 from L6 students (males = 21; females = 9); reflective of the sex imbalance of undergraduate SES students across the United Kingdom (Higher Education Statistics Agency, 2021). Participants were provided with written guidance on letter writing (e.g., not to worry about grammar or spelling; asking questions such as “What would you like to say to your younger self?,” “What would be most helpful to hear?”) and asked to complete the task in 20–30 min whilst in class. Once completed, letters were collected, transcribed, and anonymised by the third author, before being thematically analysed.

Data analysis

In line with our paradigm, reflexive thematic analysis (RTA; Braun and Clarke, 2019) was adopted to analyse the letters. Thematic analysis is an analytical approach that allows to identify repeated patterns in written data (Braun and Clarke, 2021). As Braun and Clarke (2021) explain, there are different approaches to thematic analysis. RTA better aligns with the philosophical assumptions of interpretivism, highlighting the central role of the researcher’s reflexivity in the process. Therefore, it is important to clarify our positionality as authors engaged with the analysis. Both the second and third authors are qualitative researchers with backgrounds in sport coaching and sport psychology. The second author is a postgraduate research student, who had previously engaged with thematic analysis as a student, whilst the third author is an academic with expertise using RTA. The first author instead came from a post-positivist background, related to their expertise in biomechanics, and covered the fundamental role of critical friend (i.e., a person who listens to a researcher’s interpretations and offers critical feedback, encouraging reflexivity; Smith and McGannon, 2018).

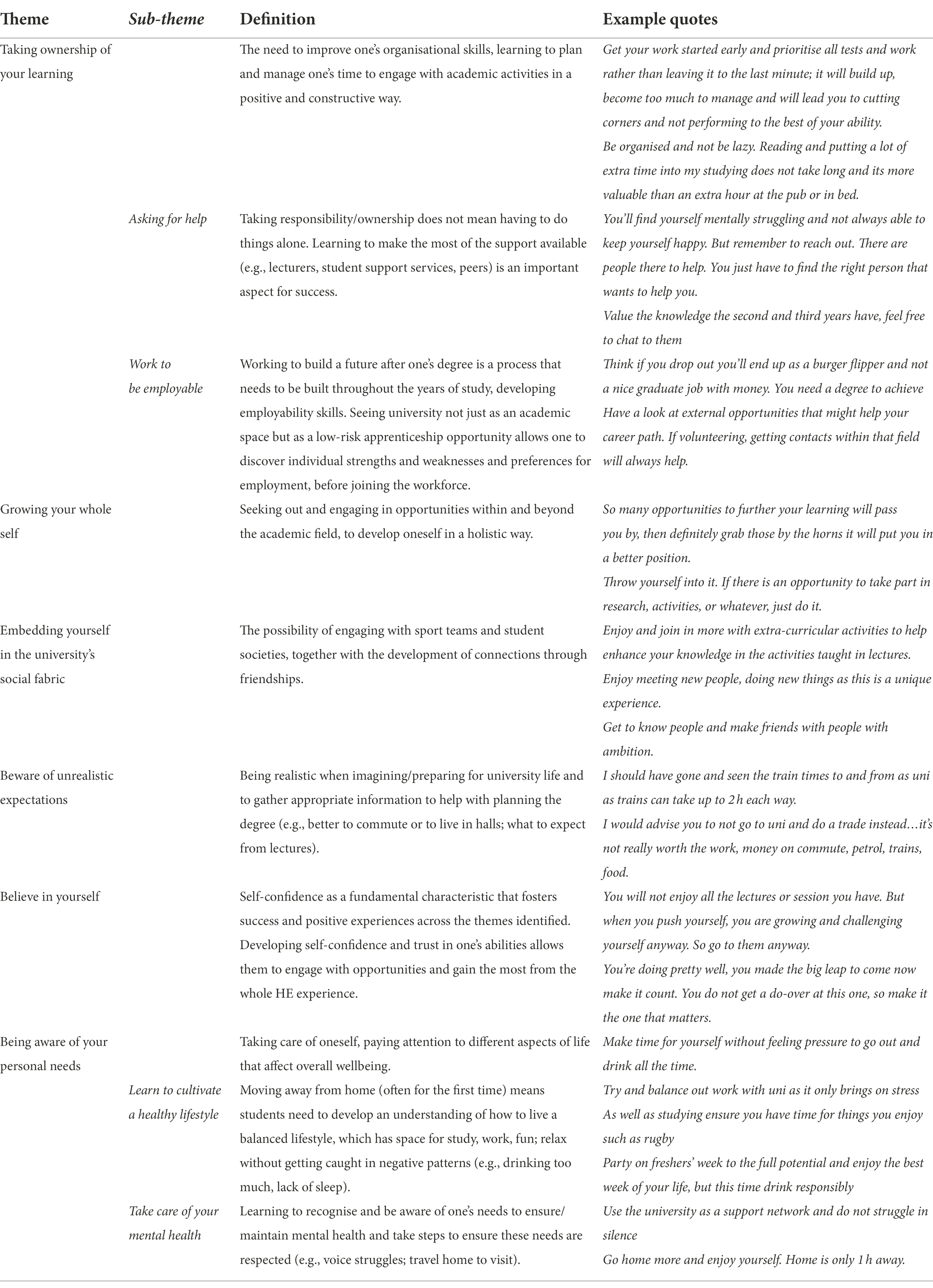

Following anonymisation of the letters, the second and third author spent time becoming familiar with the content, before engaging with an initial data-driven coding phase, analysing the whole dataset collaboratively. Themes then started to be generated and discussed until their core concepts (Braun and Clarke, 2019) were clear. When reviewing the themes, the focus was on ensuring patterns of shared meanings rather than domain summaries (i.e., capturing the diversity of meaning in shared topics; Braun and Clarke, 2019) themes were identified, to highlight different aspects – as well as different experiences – related to our research question. Once themes were finalised, names were refined, and definitions were developed (see Table 1).

Table 1. Themes identified in the “letters to younger self” with definitions and quotes contextualising the themes.

Phase 2

Following initial analysis of the letters’ content, Phase 2 was developed. A composite letter was created representing the themes identified during the RTA. The letter was embedded into the delivery of the institutional pastoral care scheme for first-year SES students.

Procedure

During Phase 2 of the project, our findings were represented using what is known as a “composite first-person narrative” (Biglino et al., 2017), which is an amalgamation of our participants’ voices into one story. In line with several authors (e.g., Spalding and Phillips, 2007; Benjamin, 2016), using composite representation of research findings helps stimulate reflection and generate discussion. To achieve this, the composite letter was integrated in our institution’s pastoral care resources and in the delivery of “community sessions” and “individual sessions” that personal tutors conducted with their tutees throughout the student’s first year.

The composite letter was portrayed in the form of an “Older, Wiser Self letter” itself, where a student advises their younger self on how to make the most out of their degree, successfully transitioning into HE and avoiding setbacks. Using quotes from the different themes identified, the letter aimed to portray participants’ voices in a form that is closer to data collected. Whilst we were aware of existing critiques to composite representation of research findings as losing the uniqueness of each human being’s voice, we agree with Hollowell (2017) who states that composite characterisation allows “to compress documented evidence from a variety of sources into a vivid and unified telling of the story” (p. 31). Moreover, keeping in mind the applied aspect of this second phase, for us it was paramount to show our findings in a way that allowed to show “the complexity and multidimensionality of these phenomena in a manner that evokes emotion and provokes action” (Sandelowski and Leeman, 2012, p. 1405).

We aimed at enhancing the rigour of our study by including reflexivity through the role of the critical friend, conducting an in-depth and thorough process of data collection and analysis, and gathering reflections from the population of interest for the study (Smith and McGannon, 2018). Through undertaking member reflection with our participants (an open dialogue with students) about the use and implementation of the composite letter, we sought to provide opportunities for questions, critique, feedback, and the chance to gain an even better understanding of our findings (Cavallerio et al., 2020). 12 Level 4 students were presented with the letter again and discussions about their thoughts on its effectiveness as a tool for supporting students’ transition into HE were facilitated by the first and third authors. Through these discussions, aspects of naturalistic generalisability and transferability of the resource were also explored. According to Smith (2018), the former is reached “on the basis of recognition of similarities and differences to the results with which the reader is familiar” (p. 140), whilst the latter occurs “whenever a person or group in one setting considers adopting something from another that the research has identified” (p. 140). Tracy (2010) suggests that transferability can be facilitated by accessible and evocative writing. In this case, the work can also develop a third type of generalisability, known as generativity (Barone and Eisner, 2012), which invites people to take action upon the experience they read about in the research representation.

In the following section, our results are represented, firstly providing a summary of themes identified (Phase 1), and then presenting the composite letter and some example responses from the member reflections with students (Phase 2).

Results

Phase 1: Following RTA, we identified six themes and four sub-themes in response to the research question, “What are the aspects that support or hinder transition into HE?.” The themes are: Taking ownership of your learning, with sub-themes Asking for help and Work to be employable; Growing your whole self; Embedding yourself in the university’s social fabric; Beware of unrealistic expectations; Believe in yourself; and Being aware of your personal needs, with sub-themes Take care of your mental health and Learn to cultivate a healthy lifestyle. See Table 1 for specific definitions of each theme and sub-theme along with example quotes.

Phase 2: Following our analysis, a composite version of an “Older, wiser self letter” was developed to represent the identified themes, using shared collective stories to create a single character (Samuels-Wortley, 2021). Below is the letter that our fictional, composite student writes to their younger self based on their experiences of transitioning into HE.

Dear younger me,

I know you are due to go to university soon, and you must be feeling nervous. But don’t worry, because once you start your first day and meet some great friends from your course, the year will fly by.

First of all, it’s important to turn up to every lecture, take good notes and do independent work in your own time. Trust me, not attending lectures had a negative impact on my learning, as each lecture I missed, I fell behind on work, which then led to twice as much work! You’re here to learn and nobody expected you to be perfect. Don’t be afraid to make mistakes – learn from them. You won’t enjoy all of the lectures or sessions you have but challenge yourself and go to them anyway. Continue to work hard, because when you see how hard you’ve worked and what you’ve achieved, you will feel so proud of how you have grown.

There are a lot of things that you will find strange and scary. One of them is the assignments in each trimester. Do not leave them to the last minute, as they won’t be up to a high standard. I would make sure each week I have set days and times to work on uni work. More planning and more reading on your commute. However, I do wish I had gone and checked train times to and from Uni, as trains can take up to two hours each way! Still, the fact you commute to Uni will not affect the social side of things. Enjoy this year, make friends, go out, and try new things. Stop worrying about what other people are thinking about you. Make sure you join all societies that interest you, and you’ll soon see your friendship group grow.

Don’t stress about money. If you’re struggling, don’t forget there is always someone at Uni to help. You could even sign up to the Employment Bureau, which can help you find work to suit you. Also go home more and enjoy yourself. Home is not that far.

Make sure you know the reasons why you came to university in the first place: it’s the start of your journey on the career pathway you want to undertake. I’m not going to lie to you, it’s going to be stressful. Learning to manage money, balance Uni and work, have a social life in a new place away from home is not easy, but the experience is worth it. Use the university as a support network, DO NOT struggle in silence. It’s okay to ask for help and support when you need it.

Thinking of the future, get an idea of what comes after uni. There are so many opportunities to develop inside and outside of Uni. Make sure you grab as many as you can and gain some experience, it will put you in a better position for a job.

Focus on you, and work to become the best version of yourself!

Best of luck,

X

Member reflections

The reciprocal open dialogue with students was fundamental to how we understood the member reflections. Their reflections prompted our own reflections of phase 2, specifically the content of the letter, its use, and how the students felt about it.

Following re-examination of the letter, students’ responses concurred it was a valuable resource as a prompt for discussion providing a shared “experience” (Smith, 2018), from which members could compare and contrast their own experiences. This could suggest generalisability to a range of student experiences. In this instance the two cohorts had very different experiences for their first year of university: the letters were written by students pre COVID-19, but read by students whose first encounter with HE had only been through the COVID-19 necessitated restrictions. Whilst the letter expressed trepidation about starting university, most of the respondents were excited to begin and eager for academic challenge: “I was like ok I am super excited as soon as I got in I was ready to absorb whatever would be taught it did not really matter what it was, I was ok let me get this.” The social aspect was of particular importance to this cohort as they had felt isolation through COVID-19 restrictions. For many, that initial anticipation to meet new people contrasted with housemates’ or classmates’ lack of interaction and some persevered, agreeing with the letter that it was active participation with sports clubs or group work (in class) that enabled them to make friends.

The area that resonated most with the students was the idea of “asking for help.” Whilst this was mentioned only briefly in the letter there was a generative quality to this statement. It provoked a wider discussion amongst the students about the challenges of asking for help such as: “I would say I like to do stuff on my own ….like I solve some things a lot but somethings I do need help.” The students did agree that once they did ask for help they would feel better: “I was struggling with the group project and then I did not say anything and then I did say something and my group helped me there.” This was of interest as we had hoped the letter would encourage action (Barone and Eisner, 2012). Whilst students did not mention that the letter encouraged a change in behaviour when they initially read it, when the letter was revisited, the discussion seemed to promote the sharing of difficulties like asking for help and agreement about the benefits of doing so once they had overcome that challenge.

This “dialogue” (Cavallerio et al., 2020) proved especially productive pertaining to when to introduce the letter to the students. It had been developed with the intention of assisting with transition, so it was assumed it would only be beneficial early in the student journey. Several members however, expressed they could not remember their first encounter with the letter: “I remember reading it but do not remember what it said.” With student transition into HE suggested as an ongoing process (e.g., Nicholson, 1990), revisiting the letter at the latter stage of their first year, as happened here, provided space for students to reflect, share and make sense of their initial transition into HE. This provoked our own reflections and discussion about when or how often to use the letter going forward (which is explored in the discussion).

Discussion

The current study utilised the lived realities of Level 5 and 6 (yr. 2 & 3) UG SES students as we aimed to understand the aspects supporting or hindering transition into HE. Following the development of a single composite version of an “Older, wiser self letter” to represent the identified themes, this resource was integrated into our institution’s pastoral care resources and specific sessions where personal tutors connected with their tutees. Member reflections were completed with students to gather feedback on the effectiveness of this resource.

Six themes and four sub-themes were identified from our analysis of the letters; Taking ownership of your learning, with sub-themes Asking for help and Work to be employable; Growing your whole self; Embedding yourself in the university’s social fabric; Beware of unrealistic expectations; Believe in yourself; and Being aware of your personal needs, with sub-themes Take care of your mental health and Learn to cultivate a healthy lifestyle.

Within the current research, students recognised the importance of taking ownership of their learning to facilitate transition into HE and was specifically linked to the development of new academic skills, such as organisational skills, managing time and engaging with academic activities in a positive and constructive manner. The development of these (and related) academic skills have been similarly reported in the literature as important in facilitating student transition into HE (e.g., Scouller et al., 2008; Van der Meer et al., 2010; Wilson et al., 2016; De Clercq et al., 2018) and understood as “early transition needs” to enable integration into the academic environment (Wilson et al., 2016). It is through establishing these academic skills that students begin forming a positive student learner identity (Leese, 2010), which is an essential factor in the persistence and success of a university student (Briggs et al., 2012).

Whilst students studying at university are required to become “self-regulated learners” (Zimmerman, 2000), they need support, starting during induction/orientation week, and continuing throughout the first-year (Palmer et al., 2009; Van der Meer et al., 2010) as they learn to become independent (Wilson et al., 2016). This support requires a nuanced co-curricular and curricular approach which recognises the diversity within the first-year student cohort (e.g., where students have progressed from), subsequently allowing distinct learner identities to be developed (i.e., Briggs et al., 2012).

Within the context of where this research was undertaken, the institution has introduced subject specific professional services staff (e.g., librarians and study skills coaches) due to recognising the nuances in support students needed across different subjects. These subject professional services staff provide a personal point of contact for academics to signpost students to (“go and see x” as opposed to “go to this building”) and enable workshops and resources to be developed which improve engagement in their students group; SES student relate to sporting examples better than geography or business examples.

An important aspect of students taking ownership of their learning is recognising the importance of asking for help. This resonated most with the students involved in the member reflections; asking for help was beneficial even if they were not used to doing so. Help, or support, can be provided through academic staff/tutors, fellow students and wider institutional support mechanisms. The relationships students develop with academic staff and their personal tutor are an important part of their integration into academic life (McGivney, 1996). Experiencing staff as supportive and approachable helps students to gain confidence within the academic environment and increases their willingness to seek out support (Morosanu et al., 2010). However, students can perceive the relationships with academic staff as much more distant compared to their previous place of study, where interaction with teaching staff was embedded in everyday learning practises (Christie et al., 2008). This feeling will be further compounded for students when tutors do not see pastoral work as part of their academic role or resource constraints limit the time that academic staff can spend with students individually (James, 1998). Indeed, students who do not feel adequately supported by their institution are more likely to drop out, especially in their first year of study (Wilcox et al., 2005).

Developing friends on the course provides an additional option to seek help beyond that offered by academic staff. Whether this is for students who experience difficulties with their academic work, or those requiring different types of social support (Morosanu et al., 2010). Regardless of where help is sought, students need to have the self-confidence to seek it out (Rocca, 2010), recognise what support is available, and learn how to access it (Christie et al., 2008).

To support students in identifying what help they need, diagnostic assessments are being used more frequently in HE, particularly during their initial weeks of HE (Jang, 2012). Whilst diagnostic assessments provide students with detailed, individualised, and explicit information which enables self-reflection upon their learning problems and opportunity to take necessary actions (Pourdana, 2022), responsibility still lies with the student to recognise the support they need and seek it out. Within the context of where this research was undertaken, results from diagnostic assessments, formative and summative feedback are used in individual tutorial sessions to provoke conversation about what support is needed and with input from the tutor, signpost appropriate support (e.g., professional services).

The final sub-theme identified in taking ownership of learning is work to be employable, a focus which will likely occur after the “early transition needs” have been met. Students recognised the importance of seeing university not just as an academic space, but as a low-risk apprenticeship opportunity. Developing student experiential learning through undertaking internship (s) is becoming increasingly common across SES in HE. It is a sound pedagogical instrument and an important educational experience, enabling students to gain real-life work experience, in an appropriate training environment as students practise what they have learned and acquire new skills (Cook et al., 2004). As students work to be employable, they will develop graduate attributes and skills through discovering individual strengths and weaknesses and preferences for employment (Zepke and Leach, 2010).

The opportunities for SES students to engage in experiential learning within their subject is vast, ranging from laboratory data collection, volunteering in local sports clubs/organisations to paid placements supporting professional athletes. The importance of institutions providing students with such learning opportunities is recognised by The British Association of Sport and Exercise Sciences (BASES) – the professional body for sport and exercise sciences in the United Kingdom. Demonstrating the provision of these opportunities is a requirement for obtaining degree endorsement.

Social integration plays an important role for students’ successful transition (Wilcox et al., 2005). This is an aspect which the member reflections highlighted had been heightened due to social restrictions imposed from COVID-19. In the current study, students recognised the importance of embedding oneself in the university’s social fabric, especially through making friends and developing a support network. The current research has previously highlighted how students developing friends on their course provides an avenue to seek help and support when facing difficulties with academic work. The additional benefit of developing a friendship network within and outside of their course (member reflection highlighted that it was active participation with sports clubs or group work (in class) that enabled them to make friends) encourages students to develop a sense of belonging (Artinger et al., 2006), feeling at home and supported (Hausmann et al., 2007).

Tinto’s (1993) theory of student integration identifies the importance of social interaction in university as it enables students to create a sense of belonging to the institution, a critical part of the retention process (Wade, 1991). When students develop this sense of belonging, they become involved in other university activities and further integrated into the university (Miller, 2011). Students, however, often do not immediately fit in at university and encounter a transient space between home and university life, where they experience feelings of not belonging (Blair, 2017). Transitioning students therefore need support with getting to know their peers and the university community and in feeling at home in HE (Ackermann, 1991; Hausmann et al., 2007; Cabrera et al., 2013; Gale and Parker, 2014; Coertjens et al., 2017). It is important that students are encouraged early in their HE journey to engage in wider university activities, as students who are not involved early typically stay uninvolved (Berger and Milem, 1999). As a result, uninvolved students are less likely to perceive the institution or their peers as supportive, less likely to become integrated, and consequently, less likely to persist (Miller, 2011).

Within the context of where this research was undertaken, since completion of this research, to engage all students early as they transition into HE, SES students are now allocated a Welcome Buddy. Level 5 or Level 6 SES students register to become a Welcome Buddy (initiative runs during first semester only) and (following training) are allocated a small number of Level 4 SES students where they chat (online) pre arrival, meet for drinks, answer questions about university life and provide a “friendly face” around campus. Future research plans to evaluate the impact of the Welcome Buddy scheme on student retention.

Member reflections were useful in generating additional insight (Smith, 2018) concerning the encounter phase of transition (Nicholson, 1990; Coertjens et al., 2017). Students revealed they not only acknowledged but relished that University would be different to what had gone before. However, they were not prepared for the discrepancies between expectations and reality when they arrived and this gap between expectation and experience when joining their course is common (Holmegaard et al., 2014). If these unrealistic expectations are not sufficiently addressed or negotiated, students will struggle to relate themselves to the study programme and be unable to gain a sense of belonging in their place of study, increasing their risk of drop out (Gregersen et al., 2021). In the current study, students cautioned against having unrealistic expectations. These unrealistic expectations were specific to irrelevant course content, cost associated with the degree (e.g., travel from home to place of study) and time requirements around commuting to university. Previous research has identified how irrelevant course content and financial requirements are a key factor for student non-continuation (e.g., Yorke and Longden, 2008; Holmegaard et al., 2014).

Nicholson’s Transition Cycle model (1990) advocates the importance of pre-entry programmes which encourage students to undertake preparation work to develop realistic expectations about the course/university they will enter. This is particularly valuable for students with limited experiences or presumptions of HE (Wong and Chiu, 2020). It is during this period where explicit and transparent expectations can be communicated regarding academic and social elements of their course/university and decrease feelings of uncertainty. With students continuing to evaluate and consider their choice of programme even after having entered HE – which for some students is a continuous process through at least their first year of study – it is important that adequate contact time with academic staff/tutors is provided to ensure support (Holmegaard et al., 2014). The member reflections suggest that the letter could be a useful tool for supporting the adjustment phase of transition (Nicholson, 1990; Coertjens et al., 2017), helping students develop realistic expectations about university life. Even for the students involved in the member reflections whose experiences were contrary with those portrayed in the letter, it still encouraged them to share and reflect on their own experiences around the mismatch between expectations and reality.

When students are transitioning into HE, it can be uncomfortable and troublesome, as they experience difficulty and anxiety as they make sense of their new environment (Meyer and Land, 2003). Gourlay (2009) suggests that confusion and emotional destabilisation should be considered as “normal” features of the student transition, with troublesome points of struggle being an important part of becoming a student. Irrespective of whether transitioning into HE is viewed by the student as a transformative experience, or a problematic one, in the current study students recognised the importance of having belief in one’s self to ensure a successful transition into HE. Having belief in one’s self, will also provide students with the confidence to engage with the other themes identified in this research, persistence to navigate the transitional space and also provide the resilience to manage unrealistic expectation, seek help when needed and engage in the wider university culture.

The importance of students having belief in one’s self when transitioning into HE is something which has not been frequently identified in the transition literature. De Clercq et al. (2018) identified the importance of students having belief in reaching personal goals as a theme in students transitioning into HE, with participants reporting the importance of [self] confidence, passion, belonging and performing in the academic context. De Clercq et al. (2018) also highlighted the importance of students having a positive attitude at the beginning of the year to enable them to thrive in the academic context. We recommend that welcome week/induction programs include sessions on how to develop self-belief and build this into support sessions delivered throughout the student’s first year of study.

Focus on supporting student mental health and wellbeing and cultivating a healthy lifestyle is becoming increasingly prominent in HE (Taylor and Harris-Evans, 2018). As students transition into HE, they will encounter new social situations as they endeavour to make new friends, negotiate unrealistic expectations and work towards becoming an independent learner. These experiences, in addition to being responsible for their own successes can be overwhelming and contribute to heightened levels of anxiety and stress (Yorke, 2000; Yorke and Longden, 2008). These feelings of anxiety and stress may be further heightened in students who have moved away from the parental home and are learning how to live independently and manage a healthy lifestyle. It is important that students are provided with appropriate levels of support and resources to maintain their mental health and wellbeing, which may be introduced during pre-entry or welcome week initiatives. Whilst the specific personal needs of each student will be different, in the current study, students recognised the importance of “Making time for yourself” and “if not having a good day…. stay at home, rather than forcing yourself and making it worse.”

In the current study, students saw the value of making the most of opportunities and new experiences as well as refining skills to grow the whole self. Specific advice from students included “Learning from mistakes,” “Getting out of one’s comfort zone” and “throwing oneself into it.” Several of the themes identified in this research provide opportunities for students to develop.

The effectiveness of the resource in supporting student transition into HE was highlighted in the students’ member reflections. When the letter was used was particularly important. When initially asked to recall the letter, replies were mostly about a lack of recollection such as: “I remember reading it but do not remember what it said.” Such reflections provided an insight into where the contradictions lie between the researchers and the participants in understanding the data or its portrayal (Smith and McGannon, 2018). In this case, it revealed the contradiction between researcher expectations and member experiences, as to when it could be most productive to introduce the letter. Following re-examination of the letter, students’ responses agreed it was a valuable resource as a prompt for discussion, providing a shared “experience” from which members could compare and contrast their own experiences. We have since integrated the letter more frequently into community and individual personal tutor sessions as a mechanism to initially prompt discussion with students.

Whilst it remains unclear when a student fully transitions into HE, a key tenant of Tinto’s model of social integration is that whilst not experienced equally by all students, transition occurs throughout their first year of study (Naylor et al., 2021); Nicholson’s transition cycle (1990) proposes that the adjustment stage lasts throughout the first year with stabilisation occurring after the first year (Purnell, 2002). Other perspectives contend that students may not have fully transitioned in their second year (or even third) year of study (e.g., Gale and Parker, 2014). We acknowledge that collecting data from both L5 and L6 students may have resulted in reflections from students who themselves have not fully transitioned into HE. However, we recognised the value in obtaining a richer data set across multiple levels of study for developing the composite letter. Future research should explore when students themselves consider to have transitioned into HE and how the single composite letter could be used to explore different narratives amongst the diverse student population.

The themes within this discussion have been presented in isolation; primarily for ease of reading. In reality, many of these themes are linked and as other authors have similarly found, reflects the complex interwoven nature of several themes involved together in the transition process (e.g., Wilson et al., 2016; De Clercq et al., 2018). This interwoven nature of the themes is likely heightened by the close community often found amongst SES students. It is common-place for students, often studying in different years of their degree, to play on the same sport team, to attend the same gym and/or exercise together, to live in the same shared accommodation, to eat and/or socialise together and spend time engaged in experiential learning, either with an academic or outside the institution. This provides a rich supportive community where many of the themes identified which facilitate transition can be collectively met.

The holistic support provided by an institution to facilitate student transition should also be delivered in an interwoven, collective manner. Limited coordination of support efforts to meet students’ multifaceted needs ultimately leads to ineffective support (Tinto, 2012). Student support offices often take a unidimensional approach to support, rather than holistically engaging students’ multiple identities, assets, and experiences (Page et al., 2019), and different support agencies often operate in an isolated restricted fashion (Manning, 2017). Too often students are expected to independently seek out the services provided by separate offices and functional areas dispersed across campus, expected to assimilate content which is not nuanced to their study programme (culture) or background (McNair et al., 2022). Within the current article, examples have been provided from the context where this research was undertaken to demonstrate how a more holistic, comprehensive, coordinated, and student-centred approach is being adopted to facilitate student transition, which aligns closely with the Ecological Validation Model of Student Success proposed by Kitchen et al. (2021).

The composite letter continues to be used as part of our institution’s pastoral care resources and specific sessions where personal tutors connect with their tutee. Future research will investigate how the use of pre arrival (pre-entry) resources (based upon the themes identified in this current research) facilitates transition into HE – Nicholson (1990) termed this the preparation phase; we propose that such pre arrival resources may serve to start the process of transitioning into HE earlier and engage students more effectively in the preparation phase. Themes have been developed into digital resources for students to engage with prior to arriving in HE. During welcome week, we are creating space for students to explore the themes of the letter, consider the results from any diagnostic assessments completed and meet subject specific professional staff members.

Summary

The themes identified from the current research suggests that student transition into HE is not a one-off event, completed during welcome/induction week. Rather, it is a more fluid and enduring component of the university experience (Pennington et al., 2018) which is shaped by the individual experience students gather in their complex interaction with their institution (Trautwein and Bosse, 2017). It is for this reason that we (the authors) believe the value of this composite letter lies in tutor-tutee and student peer-peer conversations at key “moments” throughout their journey in HE. Indeed, member reflections highlighted the value of the resource as a prompt for discussion which should be returned to frequently during the academic year. Key moments include students preparing to enter HE, during the initial weeks of induction, around points of assessment and nearing completion of the semester.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Anglia Ruskin University. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

MT and FC: conceptualization, methodology, and writing—original draft preparation. MT, FC, and SP: formal analysis, investigation, and writing—review and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Anglia Ruskin University Student Qualitative Research Group (ARQ_LAB) who were involved in a preliminary analysis of the data.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ackermann, S. P. (1991). The benefits of summer bridge programs for underrepresented and low-income transfer students. Commun. Jun. Coll. Quart. Res. Pract. 15, 211–224. doi: 10.1080/0361697910150209

Artinger, L., Clapham, L., Hunt, C., Meigs, M., Milord, N., Sampson, B., et al. (2006). The social benefits of intramural sports. J. Student Affairs Res. Pract. 43, 69–86. doi: 10.2202/1949-6605.1572

Barone, T., and Eisner, E. (2012). “Arts-based educational research,” in Handbook of Complementary Methods in Education Research. eds. J. L. Green, J. Green, G. Camilli, G. Camilli, P. B. Elmore, and P. Elmore (Routledge), 95–109.

Beasley, C. J., and Pearson, C. A. (1999). Facilitating the learning of transitional students: strategies for success for all students. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 18, 303–321. doi: 10.1080/0729436990180303

Benjamin, S. (2016). When plan a falls through: using a collective story methodology to construct a narrative. J. Hosp. Tour.

Berger, J. B., and Milem, J. F. (1999). The role of student involvement and perceptions of integration in a causal model of student persistence. Res. High. Educ. 40, 641–664. doi: 10.1023/A:1018708813711

Biglino, G., Layton, S., Leaver, L. K., and Wray, J. (2017). Fortune favours the brave: composite first-person narrative of adolescents with congenital heart disease. BMJ Paediatr. Open 1:e000186. doi: 10.1136/bmjpo-2017-000186

Blair, A. (2017). Understanding first-year students’ transition to university: a pilot study with implications for student engagement, assessment, and feedback. Politics 37, 215–228. doi: 10.1177/0263395716633904

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 11, 589–597. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2021). Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Couns. Psychother. Res. 21, 37–47. doi: 10.1002/capr.12360

Briggs, A. R., Clark, J., and Hall, I. (2012). Building bridges: understanding student transition to university. Qual. High. Educ. 18, 3–21. doi: 10.1080/13538322.2011.614468

Brooman, S., and Darwent, S. (2014). Measuring the beginning: a quantitative study of the transition to higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 39, 1523–1541. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2013.801428

Cabrera, N. L., Miner, D. D., and Milem, J. F. (2013). Can a summer bridge program impact first-year persistence and performance?: a case study of the new start summer program. Res. High. Educ. 54, 481–498. doi: 10.1007/s11162-013-9286-7

Cavallerio, F., Wadey, R., and Wagstaff, C. R. (2020). Member reflections with elite coaches and gymnasts: looking back to look forward. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 12, 48–62. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2019.1625431

Christie, H., Tett, L., Cree, V. E., Hounsell, J., and McCune, V. (2008). ‘A real rollercoaster of confidence and emotions,’: learning to be a university student. Stud. High. Educ. 33, 567–581. doi: 10.1080/03075070802373040

Coertjens, L., Brahm, T., Trautwein, C., and Lindblom-Ylänne, S. (2017). Students’ transition into higher education from an international perspective. High. Educ. 73, 357–369. doi: 10.1007/s10734-016-0092-y

Cook, S. J., Parker, R. S., and Pettijohn, C. E. (2004). The perceptions of interns: a longitudinal case study. J. Educ. Bus. 79:179.

Day, M. C., Hine, J., Wadey, R., and Cavallerio, F. (2022). A letter to my younger self: using a novel written data collection method to understand the experiences of athletes in chronic pain. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health, 1–17. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2022.2127860

De Clercq, M., Roland, N., Brunelle, M., Galand, B., and Frenay, M. (2018). The delicate balance to adjustment: a qualitative approach of student’s transition to the first year at university. Psychol. Belgica 58, 67–90. doi: 10.5334/pb.409

Dolan, Y. M. (1991). Resolving Sexual Abuse: Solution-Focused Therapy and Eriksonian Hypnosis for Adult Survivors. New York: Norton.

Fincham, E., Rózemberczki, B., Kovanović, V., Joksimović, S., Jovanović, J., and Gašević, D. (2021). Persistence and performance in co-enrollment network embeddings: an empirical validation of Tinto’s student integration model. IEEE Trans. Learn. Technol. 14, 106–121. doi: 10.1109/TLT.2021.3059362

Gale, T., and Parker, S. (2014). Navigating change: a typology of student transition in higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 39, 734–753. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2012.721351

Gourlay, L. (2009). Threshold practices: becoming a student through academic literacies. Lond. Rev. Educ. 7, 181–192. doi: 10.1080/14748460903003626

Gregersen, A. F. M., Holmegaard, H. T., and Ulriksen, L. (2021). Transitioning into higher education: rituals and implied expectations. J. Furth. High. Educ. 45, 1356–1370. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2020.1870942

Hadjar, A., Haas, C., and Gewinner, I. (2022). Refining the Spady–Tinto approach: the roles of individual characteristics and institutional support in students’ higher education dropout intentions in Luxembourg. Eur. J. High. Educ., 1–20. doi: 10.1080/21568235.2022.2056494

Hausmann, L. R., Schofield, J. W., and Woods, R. L. (2007). Sense of belonging as a predictor of intentions to persist among African American and white first-year college students. Res. High. Educ. 48, 803–839. doi: 10.1007/s11162-007-9052-9

Higher Education Statistics Agency. (2021). HE student enrolments by subject of study. Available at: https://www.hesa.ac.uk/data-and-analysis/students/whos-in-he-research (Accessed June 29, 2022)

Hollowell, J. (2017). Fact and Fiction: The New Journalism and the Nonfiction Novel. North Carolina: UNC Press Books.

Holmegaard, H. T., Madsen, L. M., and Ulriksen, L. (2014). A journey of negotiation and belonging: understanding students’ transitions to science and engineering in higher education. Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 9, 755–786. doi: 10.1007/s11422-013-9542-3

Holmegaard, H. T., Ulriksen, L. M., and Madsen, L. M. (2014). The process of choosing what to study: a longitudinal study of upper secondary students’ identity work when choosing higher education. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 58, 21–40. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2012.696212

Hultberg, J., Plos, K., Hendry, G. D., and Kjellgren, K. I. (2008). Scaffolding students’ transition to higher education: parallel introductory courses for students and teachers. J. Furth. High. Educ. 32, 47–57. doi: 10.1080/03098770701781440

James, D. (1998). “Higher education field-work: the interdependence of teaching, research and student experience”, in Bourdieu and education: acts of practical theory. eds. M. Grenfell and D. James (London: Falmer).

Jang, E. E. (2012). “Diagnostic assessment in language classrooms,” in The Routledge Handbook of Language Testing. eds. G. Fulcher and F. Davidson (New York, NY: Routledge), 120–133.

Kitchen, J. A., Perez, R., Hallett, R., Kezar, A., and Reason, R. (2021). Ecological validation model of student success: a new student support model for promoting college success among low-income, first-generation, and racially minoritized students. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 62, 627–642. doi: 10.1353/csd.2021.0062

Kress, V. E., Hinkle, M. G., and Protivnak, J. J. (2011). Letters from the future: suggestions for using letter writing as a school counselling intervention. Aust. J. Guid. Couns. 21, 74–84. doi: 10.1375/ajgc.21.1.74

Leese, M. (2010). Bridging the gap: supporting student transitions into higher education. J. Furth. High. Educ. 34, 239–251. doi: 10.1080/03098771003695494

Maunder, R. E., Cunliffe, M., Galvin, J., Mjali, S., and Rogers, J. (2013). Listening to student voices: student researchers exploring undergraduate experiences of university transition. High. Educ. 66, 139–152. doi: 10.1007/s10734-012-9595-3

McGivney, V. (1996). Staying or leaving the course: non-completion and retention. Adults Learn. 7, 133–135.

McNair, T. B., Albertine, S., McDonald, N., Major, T. Jr., and Cooper, M. A. (2022). Becoming a Student-Ready College: A New Culture of Leadership for Student Success. Somerset: John Wiley & Sons.

Meyer, J., and Land, R. (2003). Threshold Concepts and Troublesome Knowledge: Linkages to Ways of Thinking and Practising Within the Disciplines. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh.

Miller, J. J. (2011). Impact of a university recreation center on social belonging and student retention. Recreat. Sports J. 35, 117–129. doi: 10.1123/rsj.35.2.117

Morosanu, L., Handley, K., and O’Donovan, B. (2010). Seeking support: researching first-year students’ experiences of coping with academic life. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 29, 665–678. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2010.487200

Naylor, R., Cox, S., and Cakitaki, B. (2021). Personalised outreach to students on leave of absence to reduce attrition risk. Aust. Educ. Res., 1–19. doi: 10.1007/s13384-021-00503-2

Nicholson, N. (1990). “The transition cycle: causes, outcomes, processes and forms,” in On the Move: The Psychology of Change and Transition. eds. S. Fischer and C. L. Cooper (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley), 83–108.

Office for Students [OfS] (2021). Projected completion and employment from entrant data (proceed): updated methodology and results. Available at: https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/publications/proceed-updated-methodology-and-results/ (Accessed June 28)

Page, L. C., Kehoe, S. S., Castleman, B. L., and Sahadewo, G. A. (2019). More than dollars for scholars the impact of the dell scholars program on college access, persistence, and degree attainment. J. Hum. Resour. 54, 683–725. doi: 10.3368/jhr.54.3.0516.7935R1

Palmer, M., O’Kane, P., and Owens, M. (2009). Betwixt spaces: student accounts of turning point experiences in the first-year transition. Stud. High. Educ. 34, 37–54. doi: 10.1080/03075070802601929

Papathomas, A. (2016). “Narrative inquiry: from cardinal to marginal… and back?” in Routledge Handbook of Qualitative Research in Sport and Exercise. eds. B. Smith and A. C. Sparkes (London: Routledge), 59–70.

Pennington, C. R., Bates, E. A., Kaye, L. K., and Bolam, L. T. (2018). Transitioning in higher education: an exploration of psychological and contextual factors affecting student satisfaction. J. Furth. High. Educ. 42, 596–607. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2017.1302563

Pourdana, N. (2022). Impacts of computer-assisted diagnostic assessment on sustainability of L2 learners’ collaborative writing improvement and their engagement modes. Asian Pac. J. Second Foreign Lang. Educ. 7, 1–21. doi: 10.1186/s40862-022-00139-4

Purnell, S. (2002). Calm and Composed on the Surface, But Paddling Like Hell Underneath: The Transition to University in New Zealand. Paper presented at the Pacific Rim Conference for the First Year in Higher Education, Christchurch, New Zealand.

Rocca, K. A. (2010). Student participation in the college classroom: an extended multidisciplinary literature review. Commun. Educ. 59, 185–213. doi: 10.1080/03634520903505936

Samuels-Wortley, K. (2021). To serve and protect whom? Using composite counter-storytelling to explore black and indigenous youth experiences and perceptions of the police in Canada. Crime Delinq. 67, 1137–1164. doi: 10.1177/0011128721989077

Sandelowski, M., and Leeman, J. (2012). Writing usable qualitative health research findings. Qual. Health Res. 22, 1404–1413. doi: 10.1177/1049732312450368

Scouller, K., Bonanno, H., Smith, L., and Krass, I. (2008). Student experience and tertiary expectations: factors predicting academic literacy amongst first-year pharmacy students. Stud. High. Educ. 33, 167–178. doi: 10.1080/03075070801916047

Smith, B. (2018). Generalizability in qualitative research: misunderstandings, opportunities and recommendations for the sport and exercise sciences. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health 10, 137–149. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2017.1393221

Smith, B., and McGannon, K. R. (2018). Developing rigor in qualitative research: problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. Int. Rev. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 11, 101–121. doi: 10.1080/1750984X.2017.1317357

Spalding, N. J., and Phillips, T. (2007). Exploring the use of vigneettes: from validity to trustworthiness. Qual. Health Res. 17, 954–962. doi: 10.1177/1049732307306187

Sparkes, A. C., and Smith, B. (2013). Qualitative Research Methods in Sport, Exercise and Health: From Process to Product. London: Routledge.

Taylor, C. A., and Harris-Evans, J. (2018). Reconceptualising transition to higher education with Deleuze and Guattari. Stud. High. Educ. 43, 1254–1267. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2016.1242567

Tett, L., Cree, V. E., and Christie, H. (2017). From further to higher education: transition as an on-going process. High. Educ. 73, 389–406. doi: 10.1007/s10734-016-0101-1

Tinto, V. (1975). Dropout from higher education: a theoretical synthesis of recent research. Rev. Educ. Res. 45, 89–125. doi: 10.3102/00346543045001089

Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving College: Rethinking the Causes and Cures of Student Attrition. 2nd Edn. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Tinto, V. (2012). Completing College: Rethinking Institutional Action. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qual. Inq. 16, 837–851. doi: 10.1177/1077800410383121

Trautwein, C., and Bosse, E. (2017). The first year in higher education—critical requirements from the student perspective. High. Educ. 73, 371–387. doi: 10.1007/s10734-016-0098-5

Ulriksen, L., Holmegaard, H. T., and Madsen, L. M. (2017). Making sense of curriculum—the transition into science and engineering university programmes. High. Educ. 73, 423–440. doi: 10.1007/s10734-016-0099-4

Van der Meer, J., Jansen, E., and Torenbeek, M. (2010). ‘It’s almost a mindset that teachers need to change,’: first-year students’ need to be inducted into time management. Stud. High. Educ. 35, 777–791. doi: 10.1080/03075070903383211

Wade, B. K. (1991). A profile of the real world of undergraduate students and how they spend discretionary time. Paper Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Chicago, Illinois.

Wilcox, P., Winn, S., and Fyvie-Gauld, M. (2005). ‘It was nothing to do with the university, it was just the people’: the role of social support in the first-year experience of higher education. Stud. High. Educ. 30, 707–722. doi: 10.1080/03075070500340036

Wilson, K. L., Murphy, K. A., Pearson, A. G., Wallace, B. M., Reher, V. G., and Buys, N. (2016). Understanding the early transition needs of diverse commencing university students in a health faculty: informing effective intervention practices. Stud. High. Educ. 41, 1023–1040. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2014.966070

Wong, B., and Chiu, Y. L. T. (2020). University lecturers’ construction of the ‘ideal’ undergraduate student. J. Furth. High. Educ. 44, 54–68. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2018.1504010

Yorke, M. (2000). Smoothing the transition into higher education: what can be learned from student non-completion. J. Inst. Res. 9, 35–47.

Yorke, M., and Longden, B. (2008). The First-Year Experience of Higher Education in the UK. New York: Higher Education Academy

Zepke, N., and Leach, L. (2010). Beyond hard outcomes: ‘soft’ outcomes and engagement as student success. Teach. High. Educ. 15, 661–673. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2010.522084

Keywords: transition, higher education, sport and exercise science, older wiser self-letter, reflexive thematic analysis, narrative inquiry

Citation: Timmis MA, Pexton S and Cavallerio F (2022) Student transition into higher education: Time for a rethink within the subject of sport and exercise science? Front. Educ. 7:1049672. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.1049672

Edited by:

Debbie Willison, University of Strathclyde, United KingdomReviewed by:

Nancy Budwig, Clark University, United StatesRalitsa Todorova, University of Southern California, United States

Copyright © 2022 Timmis, Pexton and Cavallerio. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Matthew A. Timmis, TWF0dGhldy5UaW1taXNAYXJ1LmFjLnVr

Matthew A. Timmis

Matthew A. Timmis Sharon Pexton

Sharon Pexton