- Educational Administration and Planning (Curriculum Studies), University of Nairobi, Nairobi, Kenya

This article sought to determine the role played by the invisible curriculum on young people’s view of self-including their self-identity and self-esteem. This comes against a backdrop of accusations and counter accusations regarding, on whose doorstep should the blame on young people’s vulnerability to risk behavior should be placed on, yet limited research, especially in Kenya, has given due consideration to the invisible curriculum. The invisible curriculum accounts for more than 90% of all Students’ learning experiences including their self-conception or self-identity formation and people tend to behave in ways coherent with the view they have about themselves (self-identity). To fill this gap, a sequential explanatory research design was employed to answer one main questions: what role does accidental lessons arising from learning institutions’ social atmosphere play in young peoples’ self-identity and self-esteem development? The target population was 1,246 and Yamane’s sample size calculation formular was used to determine the sample size which was 486. Stratified random sampling was used in selecting the respondents. A self-report questionnaire with 60-closed ended questions and an interview guide with 14 open-ended questions were used in data collection. The results confirmed that accidental lessons arising from invisible curriculum elements shape young people’s self-concept or self-identity and self-esteem.

Introduction

Since young people are the future masters of our societies, nurturing a positive self-identity and healthy self-esteem promises their holistic development and better societies. As self-identities are nurtured, dynamic, complex, and numerous social influences are unavoidable, but relatively limited attention has been focused on the role played by subtle lessons arising from the invisible curriculum, which accounts for close to 90% of all young people’s learning experiences (Jerald, 2006; Alsubaie, 2015, p. 125; Killick, 2016, p. 1; Crossman, 2020), in this critical developmental process. The main role of the invisible curriculum is social education (Al.qomoul and Al.roud, 2017), preparing young people to be self-reliant, have a health self-identity and high self-esteem. Erikson proposed self-identity formation theory for only up to late adolescence stage, but Schwartz et al. (2005), cited by Zhou and Kam (2018), suggested that self-identity development process extends into early adulthood including college students. According to Shaw et al. (1995), the developmental process continues throughout one’s life cycle.

The term identity is a general word used to describe one’s comprehension about self as a separate entity. The “development of positive identity/identities involves developing a healthy self-esteem, reducing self-discrepancies, and fostering role formation and achievement” (Tsang et al., 2012, p. 1). “It promotes an individual’s awareness of his or her strengths and weaknesses and thus facilitates personal functioning and wellbeing” (Erikson, 1968 cited by Zhou and Kam, 2018). While one’s personal identity or self-identity is how one perceives self, one’s social identity is how other people perceive him or her (Studios, 2020). Self-esteem refers to a person’s feelings of self-worth or the value that people place on himself or herself. While self-esteem is a more particularly an evaluation of the self—how one feels about self, self-identity is a comprehensive description of self. The two terms, self-esteem and self-identity are rooted in how one views self and even though they are separate, they overlap and more often than not feed-off of each other in diverse ways (Niebergal, 2010). Self-identity (self-image) influences ones’ self-esteem which has a significant role in one’s success. Berzonsky (1981) claimed that “the element of ‘Me’ can be simply broken down into; a physical self, a social self, a moral self, and a psychological self.”

Largely people’s self-identity and/or self-esteem predicts one’s relationships, job performance, educational attainment, and whether one feels good or bad about himself or herself on a day-to-day basis (Orth and Robins, 2013; Pic Editor Review, 2021). Those with a positive self-identity (positive self-image) have strong character, are confident, have healthy self–esteem, are more resilient, reflective, and autonomous (Kroger et al., 2010; Abbassi, 2016). “A series of debacles such as blurred decision-making and vulnerability to despair in life—an illness that involves the body, mood, and thoughts and affects the way one eats and sleeps, the way he or she feels about himself or herself, the way he or she thinks about things as well as his or her view about his or her daily functioning” (Klein et al., 2011), however often follow those with poor self-identity and low self-esteem. Erol and Orth (2011) posited that low self-esteem is not only related to unhappiness and hopelessness among young people, but also to learning disorders among students, antisocial behavior, increased possibility of anxiety, oversensitivity, stress, and depression. In essence, poor self-identity and low-self-esteem makes ups and downs of life harder to endure. According to Pic Editor Review (2021), those who suffer from poor self-image “have a fickle motivation and find it difficult to set long-term goals because they do not find meaning in what they do.” On the contrary, a healthy self-identity can help young people remain grounded in upright moral standards like honesty, integrity, compassion, and responsibility against social pressures that often affect young people’s moral base negatively and lead some to psychological problems like worry and sometimes suicidal tendencies (Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2007). Even though researchers like Arshad et al. (2015, p. 156) were of a contrary opinion when they claimed that “high self-esteem does not prevent young people from smoking, drinking, taking drugs, or engaging in early sex. If anything, high self-esteem fosters experimentation, which may increase early sexual activity or drinking.” In general, a healthy self-identity and high self-esteem predicts a more happy and successful life because they enable one to approach life in a more productive and positive way.

One’s identity (self-esteem and self-image) is shaped from early years (Pic Editor Review, 2021) by factors like genetics, and the image one has of his or her parents/guardians, given the amount of time young people spent in learning environments—close to 900 h per year, learning institutions’ invisible curriculum play a significant role in not only shaping young people’s cognition, psychology, behavioral traits, but also in shaping their identity (Watson, 2019). According to Beane (1982) and Durand-Delvigne and Duru-Bellat (1998), self-conceptions are related to various aspects of schooling. Dombrovskis (2016) echoed the same sentiments when he claimed that it is commonly understood that identities emerge under the influence of one’s surrounding environment and how one perceives other people as viewing him or her. The socialization process assists young people to be self-aware as they look at themselves from the perspective of other people. Kentli (2009) and Ray (2019) observed that learning institutions’ invisible curriculum serve to transmit silent messages to young people about attitudes, values, and principles which heavily influences their view of self. The subtle lessons are more influential than the official curriculum in shaping young people’s beliefs about self and their social behavioral patterns (Kentli, 2009, p. 83; Leask, 2009; Haggar, 2013; Abbassi, 2016). These sentiments were echoed by Çubukçu (2012) and Hafferty and O’Donnell (2015) when they suggested that much of the knowledge leaners acquire in their learning contexts is through casual interactions and communications and compared to the formal curriculum, the unintentional learnings have greater impact on young people’s social personality formation. According to Ryan (2008), some of the invisible curriculum lessons reinforce suppressed identities and their importance for organizing social life and make some young people feel uncomfortable about their self.

This research does not in any way suggest learning environments should be entirely blamed for young people’s poor self-identity and/or low self-esteem, but as highlighted earlier learning institutions are the most important social contexts within which young people’s identity formation unfolds (Abbassi, 2016), because young people spend a great part of their formative years in learning institutions. This means no learning institution can afford to nurture young people’s intellectual aptitude without commensurate positive self-identity and healthy self-worthy because doing so would “make as much sense as putting a high-powered sports car in the hands of a teenager who is high on drugs” (Mahatma Magadhi).

Related Literature

The link between self-identity and learning is not a recent concept because learning has always been a lifelong process of learning to be. As young people take on different roles in their lives, and become part of diverse communities, the surrounding environments, and the people around them influences their learning and the kind of people they become. The school curriculum in its initial Latin roots means “to run a course” and if we think of it as a marathon race with direction markers, signboards, officials as well as coaches along the way and water stations (Wilson, 2021), it means the official curriculum takes place in a context that encroaches on every teaching-learning process, which constitutes to what this article refers to as the invisible curriculum. learning institutions teach young people a great deal of lessons through how they react or respond to their actions. Shaw et al. (1995) claimed that social interactions can complicate or facilitate young people’s personal identity formation. The unexpected lessons extend beyond formal educational objectives because every action performed or omitted, every silence or every joke, teach young people certain values and beliefs that have a potential of shaping their self-identity and self-esteem (Mahood, 2011). They leave their effects on Students’ perception about themselves (Yüksel, 2006; Chandratilake and de Silva, 2009). As noted by Ahsun and Khan (2018) girls and boys can have different experiences even when they “sit in the same classroom, read the same books and listen to the same teachers at the same time” (p. 2810). Shaw et al. (1995) citing Eder and Parker (1987) claimed that certain social activities reinforce characteristics like aggressiveness, toughness, and competitiveness in male students, and emotional control and appearance management for female students. The social activities function as gendered instances that reinforce femininity and masculinity perspectives.

“The concept of an invisible curriculum has been defined differently including the secret, unstudied, underlying, tacit, non-academic outcomes of schooling, unseen curriculum, by products of schooling or scum of teaching-learning processes and/or elements of socialization that take place in school, but are not part of the formal curricular content” (Martin, 1976; Margolis and Romero, 2001, p. 6). According to Portelli (1993, p. 345), the term invisible curriculum implies four meanings: “the hidden curriculum or the unofficial or implicit expectations, values, norms and messages conveyed by learning institution actors; the hidden curriculum as unintended learning outcomes; the hidden curriculum as implicit messages emanating from the structure of learning institutioning and the invisible curriculum as created by the students who infer and anticipate what they need to do to be rewarded.” Snyder, 1973 described the hidden curriculum as what happens in classrooms rather than what policymakers say they want to happen. “In this article the term invisible curriculum is understood in line with Crossman (2019) who referred to it as the unwritten, and often accidental values, and perspectives students pick simply by setting their foot in a learning institution through the socialization as opposed to the official curriculum which consists of predetermine teaching-learning activities.” McCoy (1990) citing Klaus Hurrelmann’s (1988) description of socialization mirror this researcher’s view of the term as “the process of the emergence, formation, and development of the human personality in dependence on and in interaction with the human organism, on one hand, and the social and ecological living conditions (majorly the invisible curriculum) that exist at a given time within the historical development of a society on the other” (P. 2). Eisner (2002) posited that “if we are concerned with the consequences of school programs and the role of curriculum in shaping those consequences, then it seems to me that we are well advised to consider not only the explicit and implicit curricula of schools but also what schools do not teach.”

Every learning activity is a foundational instance in Students’ self-identity and/or self-esteem formation because unplanned lessons arising from the teaching-learning activities provides non-identity or identity “through symbolic formations of a real culture which young people internalize and exercise in their gender roles” “in designing the sense of living of the individuals” (Hernández et al., 2013, p. 89). According to Valance (1993) much of the knowledge young people acquire arise from non-verbal communications. Killick (2016) echoed the same sentiments when he claimed that the messages the invisible curriculum carries are powerful. The accidental lessons socially create Students’ self-identity and/or self-esteem dependent upon the socialization process. We do not even need scientific surveys to convince us about what our eyes are revealing concerning consequences of poor self-identity and low self-esteem among young people—drug abuse, uncontrolled moral behavior, and suicide attempt, to mention but a few.

This is because choices young people make during their formative years are affirmative of their self-identities (Lannegrand-Willems and Bosma, 2006) and can either ease their holistic development and commitment which is the first indication of self-identity achievement, or they can make it impossible. In Kenya comparatively little attention has been directed toward the curriculum that is characterized by lack of mindful preparation and informality and its influences on young people’s self-identity and self-esteem formation, yet its lessons are indeed power-laden. Its lessons are usually accepted as the status quo—not necessarily needing any change—even when they contribute to undesirable results like low self-esteem and poor self-identity among young people (Killick, 2016). This means a sizeable part of curricula has not been taken into consideration, especially when designing new curricular even though the lessons it conveys are indeed power-laden (Kentli, 2009, p. 83).

The implication here is that there is a dire need for thorough investigation on influences of the invisible curriculum on young people’s self-identity and self-esteem formation, especially now than ever before, because current social atmospheres more often than not are offering inconsistent messages regarding oneself, which leads to deep disappointments among young people. Disappointments in life, according to Erikson (1968, 1974; cited in Angela, 2019) are unavoidable because they are linked to developmental stages but being cognizant of the invisible curriculum and its effects on young people’s self-identity and self-esteem formation can facilitate holistic nurture of young people to effectively reconcile their developmental crises/disappointments and have positive self-identity and healthy self-esteem. Marcia (1993) emphasized that one’s “identity formation involves complex interplay of intrapsychic processes and interpersonal experiences” and intensifies during schooling years, hence the reason why this research emphasizes creating favorable learning environments to effectively nurture positive self-identity and healthy self-esteem. Jerald (2006) argued that social environments characterized by love, trust, and caring support in exploration of identity alternatives are key in developing positive self-identity.

Learning environments remains places where young people are expected to be enabled to look deep into their lives and find out who they really are, but many college students still go through identity difficulties (Kohlhof, 2018). In both public and Christian universities young people often begin their education at about 18 years old, isolated from mostly positive peer pressure they enjoyed from like-minded children and parents at home and exposed to unhealthy forces which threatens establishment of a positive self-identity and healthy self-esteem which informs their behavior for the rest of their lives. Christian learning institutions major aim is to provide academic environments where a wholistic view about self and God is nurtured and integrated in every area of Students’ life, but many of them rarely think about the invisible curriculum which subtly teach young people “how to behave, walk, speak, clothe, interact, and so on” (Drew, 2021). This threatens Christian learning institutions’ mission of ennobling every young person’s personality (unique self-identity) so that he or she may again reflect the image of God (White, 2020). The question then begs: how best can we ensure that every social learning context enhances positive self-identity and healthy self-esteem development among young people? The need therefore to investigate how subtle lessons arising from Christian learning institutions affect young peoples’ self-identity and self-esteem, cannot be overemphasized. The following specific research questions guided the research:

1. Are there significant relationships between accidental lessons arising from social learning contexts (class organization and teaching styles) and Students’ (young people’s) view of self?

2. Are there significant differences between how male and female students perceive accidental lessons arising from class organization as affecting their self-identity and self-esteem?

3. Are there significant differences between how female and male students perceive accidental lessons arising from teachers’ teaching strategies as affecting their self-identity and self-esteem?

Methodology

The design employed in this research was sequential explanatory because it is correspondent with the procedures and nature of the present study. According to Creswell (2009), a mixed methods approach is a rigorous inquiry that combines both quantitative and qualitative methods of data collection to answer research questions. The British Food Journal (found online) summarizes the advantages of combining both quantitative and qualitative research methods in one research…“we particularly like papers that combine the two approaches–the sum of the two parts is bigger than the whole. The quantitative approach gives numerical data, while the qualitative approach gives underlying reasons.” Based on this quote no single research approach is sufficient by itself to capture the breadth and depth of complex phenomenon like the invisible curriculum. Current researcher therefore assumed mixing data sets would give a better understanding as well as reduce limitations of either the qualitative or the quantitative. The researchers began with quantitative data collection and analysis phase, then informed by the quantitative findings she developed an interview guide with 14 open-ended items for the qualitative phase to enrich the quantitative data. The research was conducted in Nairobi City County, Kenya and the target population consisted of 1,246 undergraduate students in Christian universities because some young people in Christian universities struggle with doubt about self, fear, and hopelessness.

Instrument of the Study

The instruments used to measure respondents’ perceptions on influences of the invisible curriculum were a 5-point Likert scale questionnaire with 64-closed items. Each statement required students to indicate their levels of agreement: strongly agree, agree, not sure, agree and strongly agree, with the statement in terms of invisible curriculum’s influences on their self-identity. The questionnaire and the interview guide were designed by the researcher with critical assistance from experts in curriculum design and instruction. The interview guide comprised 14-open-ended items to gather in-depth information regarding why some hidden curriculum elements were perceived as more influential than other did.

The Sample

The research sample was determined using Taro Yamane’s sample size calculation formula, which is given by n = N/(one + Ne^2): where n = corrected sample size, N = population size, and e = Margin of error (MoE), e = 0.05 based on the research condition, was employed. The target population of regular undergraduate students, ages 17–30 years, at Africa International University was 680, at the beginning of July 2020 when data was collected. Hence, at 5% MoE., the sample size was 680 (1 + 680 (0.05^2) = 680/2.7 = 251.85∼252. Regular undergraduate students at Kenya Methodist University were 566, ages 17–30 years. Hence, at 5% MoE., the sample size was 566/(1 + 566 (0.05^2) = 566/2.42 = 233.884∼234-a total of 486, male and female students, whom the researcher selected through stratified random sampling. She divided students into two strata according to their gender, arranged them chronologically according to their admission numbers and proportionately selected samples from each stratum (gender): 389/680 × 252 = 132; 291/389 × 252 = 120; 302/566 × 234 = 125; 164/566 × 234 = 109. In the qualitative phase the researcher purposively selected 10 key informants (5 young men and 5 young women) who were perceived as having rich information (having been in their learning institutions the longest—at least 4 years by the time the research was conducted.

Research Instrument Validation

The researcher presented the questionnaire to two experts in curricula design and instruction for its face value validation. The questionnaire items were edited according to comments from the curriculum experts. The researcher also conducted a pilot study among 30 undergraduate students from a different Christian university in Nairobi City County. The Cronbach Alpha was used to assess internal consistency of the questionnaire items and a reliability coefficient of 0.87 was indicated showing strong consistency between items which means the results of the research can be depended upon. In ensuring trustworthiness of the interview guide items, the researcher conducted a pilot-test among 3 undergraduate students who were not part of the research sample. They each confirmed that each of the 14 interview guide items were easily understood.

Data Collection and Analysis

The researcher administered the questionnaire to selected students in classrooms for effective feedback. The questionnaires were filled within 40 min and returned to the researcher. Out of the 486 administered questionnaires, 417 were correctly filled and handed back to the researcher. Of the 417 participants who filled and returned the questionnaire, 221 (53%) were male while 196 (47%) were female. The researcher also interviewed 10 key informants. Each face-to-face interview took about 30 min and the research audio tapped participants’ responses and transcribed them verbatim. The inferential and descriptive statistics were utilized in analyzing the quantitative data. The researcher compressed the 5-Likert scales to three for easy analysis: agree, not sure, and disagree and used descriptive statistics to determine the frequency of participants’ responses. The inferential statistics applied were Pearson correlation coefficient to determine intercorrelations between accidental messages arising from class organization and teaching strategies and respondents’ self-identity and a chi-square (χ2) of association (independence) also known as Pearson’s Chi-Square at a significance level of to determine whether Students’ gender is related to their perceptions regarding how accidental lessons arising from learning institutions’ social learning contexts was influencing their view of self.

The grounded theory analysis approach was utilized in analyzing the qualitative data because it offers researchers a more neutral view of understanding human behavior within their normal social contexts. The researcher red the textual data several times, identified repeating themes, carefully coded emerging themes with phrases and keywords, hierarchically grouped the codes into major ideas, and then developed themes through relationship identification.

Discussion of the Research Findings

The findings, both quantitative and qualitative, majorly concurred with other research findings like those of Shaw et al. (1995), Durand-Delvigne and Duru-Bellat (1998), and Meškauskienė (2017, p. 1), among other researchers who claimed that conducive learning environments in their entirety are the most important factors influencing formation of young people’s self-identity, self–esteem, and creative autonomy.

Students’ Perceptions About Self and Accidental Lessons

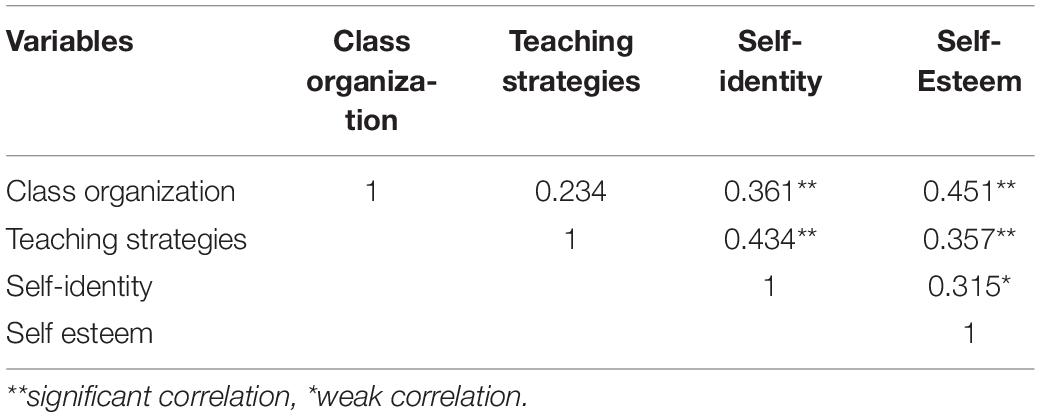

The Pearson correlation coefficient conducted to test hypothesis 1: there is so significant relationships between Students’ perceptions about self and accidental lessons arising from their social learning contexts. The results summarized in Table 1 indicated a significant and positive relationship between Students’ perceptions about self: their self-identity (r = 0.36, p < 0.01) and self-esteem (r = 0.45, p < 0.01) and accidental lessons arising from classroom organization as well as a significant and positive relationship between accidental lessons arising from teaching strategies and Students’ perceptions about self: self-identity (r = 0.43, p < 0.01) and their self-esteem (r = 0.36, p < 0.01). The results, however, differ with Ward et al. (1988) who suggested that caring environments are important in self-identity formation but are more central to identity formation of female students than male students.

Students’ Gender and Perceptions on Accidental Lessons From Organizational Structure

The descriptive results conquered with the Pearson correlation coefficient findings in that, accidental lessons arising from class organization, how instructors say what they say and do what they do as well casual interactions in learning institutions shape Students’ view of self. The findings also echo other research findings like those of Sharp (2012) which revealed that invisible curriculum elements “reinforces cultural messages about gender, including the idea that gender is an essential characteristic for organizing social life.” In this research male and female students who correctly filled and returned the questionnaire equally perceived accidental lessons arising from class organization as shaping their self-identity and self-esteem. Over 80% of both male and female students agreed that class organizations that emphasize on empowering female students were perceived as ways of ignoring male students which negatively affected some of the female Students’ self-identity and self-esteem negatively. Close to 79.8% of both male and female students agreed that accidental lessons arising from how some teachers label students and the biases they carry to class especially when only male students are requested to help in certain tasks portray male students as better than girls and emphasize the fact that female students are not equal to male students which affects female Students’ self-identity and self-esteem negatively. Over 75% of both male and female students agreed that gendering experiences within some classes significantly influence how male and female students construct their self-concepts and/or develop their self-esteem. Over 70% of both male and female students disagreed that when they sit in the same classroom arranged in rows, listen to the same teacher positioned in front of the lecturer and/or read the same textbooks their self-identity/or self-esteem is affected differently. Over 60% of both male and female students agreed that their learning institutions’ organized way of managing complaints in class lowers male and female Students’ self-identity and self-esteem. About 54% of both male and female students disagreed that emphasis on exam grades as the only means for determining Students’ success make both made male and female students think cheating in exams was wise because when one fails in exam it makes him or her feel lesser than those who pass. Close to 52% of both male and female students disagreed that emphasis in some classes for every student to follow what their lecturers teach makes them both male and female students lose confidence in self in equal measure. Close to fifty-one percent (50.6%) of both male and female students agreed learning institutions’ assessment strategies make both male and female students perceive themselves as inferior (low self-esteem) compared to those who perform better than them in exams.

Null Hypothesis Results

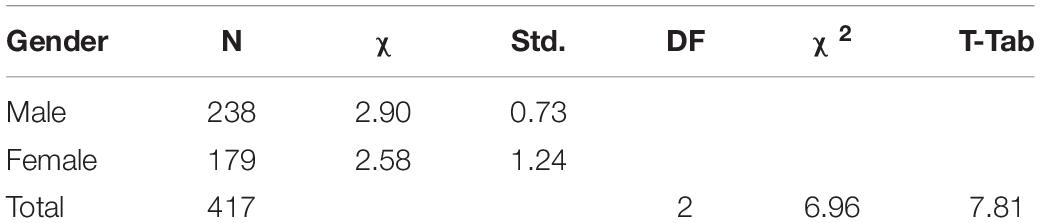

Null hypothesis one (H2): there are no significant relationships between Students’ gender and their perceptions regarding how accidental lessons arising from class organization shapes their self-identity and self-esteem. Table 2 provides a summary of the chi-square statistic value (χ2).

The chi-square test of independence the researcher performed to examine the relation between Students’ gender and their perceptions regarding how accidental lessons arising from class organization shape their’ self-identity and/or self-esteem did not indicate a significant relationship. The chi-square test statistic as indicated in Table 2 is (6.96) was greater than (5.99), DF = 2 and P-value = 0.308, which is less than 0.05, hence, hence, null hypothesis 2: there are no significant relationships between Students’ gender and their perceptions regarding how accidental lessons arising from class organization shapes their self-identity and self-esteem, was not rejected, and concluded that Students’ gender do not influence how they perceive the invisible curriculum as shaping their self-identity and self-esteem.

Students’ Gender and Perceptions on Accidental Lessons From Teaching Strategies

The descriptive results on research hypothesis two: there is no significant differences between how female and female students perceive accidental lessons arising from teachers’ teaching strategies as affecting their self-identity and self-esteem, conquered with the Pearson correlation coefficient findings. Close to 75% of both male and female students agreed that impromptu remarks of teachers and fellow classmates was a key contributor to confidence in self (wholesome self-identity) and their creativity in to seeking alternative ways where other young people give up. About 70% of both male and female students agreed that their becoming happiness level and desire to become somebody important (high self-esteem) was to a great extent determined by the accidental lessons they unconsciously pick from behavioral expectations and values cherished in their learning environments. Close to 60% of both male and female students agreed that multi-sensory appeal in on-ground classrooms where students physically interact with instructors, participate in face-to-face discussions, and ask personal questions, as opposed to on-line classes, boosts their self-identity and self-esteem. About 53% of both male and female students who participated in the research disagreed that limited implicit expectations from their lecturers and inadvertent comments in some on-line classrooms distorts their self-conception and affected some female Students’ lives in the future. Close to 51% of both male and female students agreed that a lack of cultural responsiveness in some on-line classes more often than not compromises female Students’ self-identity and their ability to complete their academic tasks. Fifty percent (50%) of both male and female Students’ who participated in the research disagreed that some on-line learning exchanges suggest hiding one’s identity and any distressing feelings from other people was the most important thing if one wanted to survive in online learning platforms. The findings that reveal insignificant differences between how male and female students perceive the invisible curriculum as shaping their self-identity and/or self-esteem are significant because social interactions are simply collaborating face-to-face or through technology and responding in relation to other people, but they contradict Shaw et al. (1995) and Hossaini (2002), who suggested that identity development was “more complex for females than for males and females, on average, have a lower sense of self-esteem than males.”

Null Hypothesis Results

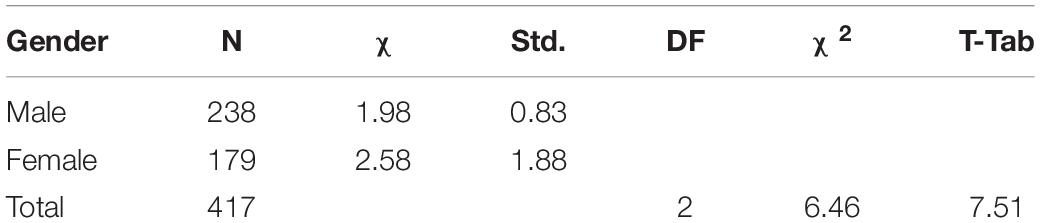

Null hypothesis two (H3): there are significant differences between Students’ gender and their perceptions regarding how accidental lessons arising from teaching strategies teachers employ shape their’ self-identity and self-esteem. Table 3 provides the chi-square statistic (χ2) result.

The chi-square test of independence the researcher performed to examine the relation between Students’ gender and their perceptions regarding how accidental lessons arising from teaching strategies teachers employ shape their’ self-identity and self-esteem did not indicate a significant relationship. The chi-square test statistic as indicated in Table 3 is (6.46) was greater than (5.99), DF = 2 and P-value = 0.0396, which is less than 0.05, hence, hypothesis 3: there are no significant differences between Students’ gender and their perceptions regarding how accidental lessons arising from teaching strategies teachers employ shape their’ self-identity and self-esteem, was not rejected concluded that Students’ gender does not influence how they perceive the invisible curriculum as shaping their self-identity and self-esteem.

The Textual Data

The research employed grounded theory approach in analyzing the textual data and the findings generally concurred with the quantitative data in that invisible curriculum is everything young people learn within their learning institutions without their teachers’ intention or realization and a major contributor of the accidental lessons is teachers’ beliefs, values and attitude, class organization and teachers teaching strategies. The participants concurred in that accidental lessons arising from the way classes are organized in their learning in institutions shape their self-identity and self-esteem either negatively or positively. The 10 interviewed participants concurred in that the way their learning institutions are organized, and casual interactions sometimes convey undesirable messages that negatively affect their view of self. For example, participant 04 asserted “the unwritten lessons young people pick up in their learning institutions through reading non-verbal social cues including things like, ‘it might be OK for students to curse their colleagues, but make sure that there is no adult within earshot,’ negatively affect victims’ self-identity and self-esteem.” According to participants 03 and 08, the high status of instructors stressed by a huge table and a chair in front of the class make some students feel insignificant and lower their self-worthy. Participant 04’s argument echo Workman (2012) who claimed that self-identity development is strongly shaped by social interactions and needs concerted effort by parents, learning institutions, media, and the society to effectively nurture a strong sense of self in all young people. The following paragraph below is an excerpt from the field notes having undergone through initial meaning reconstruction:

Researcher: according to your understanding how do your day-to-day experiences in your learning context relate with how you perceive yourself: your self-identity and/or self-concept?

Interviewee: mmmmmm…the terms at first sight appear abstract but I think they describe oneself comprehensively—in all its facets including all features which defines an individual and according to my opinion some experiences we as students go through in learning contexts make it difficult for some of us to describe our feelings about who we think we are (self-identity) and correctly express our worthy (self-esteem) in wards.

Researcher: what would you say majorly contributes to such feeling?

Interviewee: there may be many factors that contribute to it, but one’s experiences, especially Students’ interactions with teachers and fellow students especially teachers’ attitude toward students in classrooms and the approaches they employ in teaching momentously shape the picture young people have of themselves.

Researcher: would you say social learning environments affects girls’ and boys’ view of self: self-identity and self-esteem differently?

Interviewee: aaaaa, I’m not sure but what when young people go to college, they mostly have a certain level of self-confidence—a degree of an awareness of who they are and have an attitude toward self but I doubt whether all learning institutions, particularly in Kenya, can say they have reached a point where they can truthfully claim to have created equal opportunities for all students, both young men and women, and thus say they are equally nurturing their view of self. I think some learning institutions’ experiences affects young women’s self-worth negatively even when learning institutions do not mean it. The accidental lessons arising from some interactions in learning contexts, class organizations and the attitudes some instructors, particularly in public instructions, cherish negatively shapes female Students’ view of self.

These findings echo Hansen (2018) fining which revealed that learning institutions tend to reproduce status quo–including inequalities. Participant 06 claimed that unless learning institutions are organized in a manner that facilitate mapping positive values on the official curriculum to nurture positive self-identity and healthy self-esteem among young people, some of the challenges young people face are likely to continue affecting their identity negatively. When the researcher probed participants to explain why face-to-face learning settings were perceived as more effective in inculcating a holistic view of self in young people, participants 05 and 01 suggested that most instructors in face-to-face classes enact their values and beliefs during class interactions with students which help students to foster more in-depth relationships with their God and self which in turn boost their self-identity/or self-esteem. Participant 09 asserted, “I have learnt self-respect and consideration for other people from observing how my university administration treat students.” Participant 07 added that based on how his university administrative staff interact with students his confidence in himself had been boosted. Participant 03 asserted:

The need to have confidence in myself during hard times was great in one of my instructors at a time I did not seem to grasp anything in class because I was going through a lot of life challenges. She made me not to get disappointed and demoralized. My lecturer was busy encouraging me even when I felt like giving up. I applied the same encouragement when one of my colleagues was disappointed. I suggested to him that it was important have faith in himself it worked for him.

Interestingly, in most of the investigated universities’ strengths, is also where some of the participants pinpointed certain weaknesses. For example, participant 03 explained that “within diverse teaching-learning activities that encourage passivity in female students or do not actively discourage male Students’ domination feminize female students into demeaning self-perception.” Participant 10 added that “when some teaching-learning activities treat student the same way in the name of ‘fairness,’ such teacing0-learning activities can negatively impact some Students’ self-identity and self-esteem because even identical twins are quite different” Participant 09 asserted “unconscious biases some educators carry with them into class sometimes downplay women’s achievements and often make them lose confidence in self and become dependent on their counter parts (boys) and their lecturers.”

According to participant 01 learning interactions that lack respectful relationships between instructors and students negatively affect young people’s view of self. When the researcher probed participant 01 to explain what she meant, she asserted “online learning is great, especially now during COVID-19 pandemic, but with more complex competencies like view of self and critical thinking skills development, there needs respectful interactions between educators and students.” Participant 04 explained that e-learning can be made more interactive through use of webinars, video conferences and chats but it can never be the same as sitting in a real face-to-face classroom-in other words it can never be a real replacement of intermingling with fellow human beings in classroom.

Conclusion

The major finding in current research was that when we create learning environments, we are not just facilitating young people to only learn facts because such environments are part of what forms their self-identity and/or self-esteem. The accidental lessons arising from the values instructors carry to class, the ways in which they say what they say and do what they, the teaching strategies they employ as well as messages conveyed through casual interactions have a more profound impact on Students’ self-identity and self-esteem formation than what is officially taught through the official curriculum. For instance, negative criticism and biases some instructors unconsciously carry to carry to class can fill students with self-doubt when they believe what is implicitly conveyed to them. The none-verbal lessons can lead to poor self-identity and low self-esteem formation which can easily become a destructive downward cycle, hard to stop. This research findings seem to suggest face-to-face class interactions are more effective compared to online interactions in shaping positive self-identity and/or high elf-esteem among students. The enacting of positive values and beliefs by lecturers and fellow students was perceived as important in fostering wholistic views about God and oneself which in turn boosts both male and female Students’ self-identity/or self-esteem. This finding is in line with researchers like Rogers (2014) who claimed that self-identity development is a lifelong process influenced by the agents of socialization including learning institutions and family. The accidental lessons influence who young people become within the learning context and in the society. This research findings also concur with Henderson and Gornik’s (2007) and Verhoeven et al. (2018), who claimed that learning institutions are places where young people spend a lot of time which make then important contexts of self-identity formation which means what is not officially taught is as educationally important as what is officially taught. Current research therefore concludes that the invisible curriculum students instinctively imbibe plays a central role in the tacit transfer of values and attitudes which affects their self-identity and/or self-esteem either positively or negatively.

These findings are beneficial in helping educators and parents/guardians to deal with self-identity and/or self-esteem issues among students in higher education. They call attention to aspects of teaching-learning processes that are only infrequently acknowledged but remains largely unexamined. The researcher recommends more attention to the influences of the invisible curriculum than is usually the case. Workshops could be provided to educators who wish to positively nurture male and female Students’ self-identity and self-esteem to raise their awareness about both positive and negative effects of the invisible curriculum. All invisible curriculum dimensions need to be actioned deliberately and with robustness to ensure learning institutions thrives with positive attitudes and positively shape young people’s self-identity and self-esteem. Educators need to identify positive invisible curriculum elements and effectively map them into the official curriculum to socialize students into people with positive self-identity and high self-esteem. Even though theorists have taken diverse points of view about the invisible curriculum, they principally emphasize the significant role it plays young people’s socialization.

Strengths and Limitations

Like any other mixed methods research, current research was time consuming, but combining both qualitative and quantitative methods produced a more comprehensive understanding of the research phenomenon, and the finding can confidently be generalized to other populations. Even though the research sample was large (n = 617), it did not investigate socio-demographic aspects that also shape young people’s view of self which means more extensive and may be comparative research needs to be conducted within rural and urban learning institutions, including public learning institutions to broadly determine influences of the invisible curriculum on young people’s self-identity. Chi-Square value calculation is extremely sensitive to sample size and since the sample size in current research was over 400, close to 500, the given maximum, another research can be conducted, and the data analyzed using a different statistic.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abbassi, N. (2016). “Adolescent identity formation and the school environment,” in The Translational Design of Schools. Advances in Learning Environments Research, ed. K. Fisher (Rotterdam: SensePublishers).

Al.qomoul, M., and Al.roud, A. (2017). Impact of hidden curriculum on ethical and aesthetic values of sixth graders in Tafila directorate of education. J. Curric. Teach. 6, 35–44. doi: 10.5430/jct.v6n1p35

Alsubaie, M. A. (2015). Hidden curriculum as one of current issue of curriculum. J. Educ. Pract. 6, 125–128.

Angela, O. M. (2019). Child Development Theory: Adolescence (12-14). Available online at: https://www.risas.org/poc/view_doc.php?type=doc&id=41163&cn=1310 (accessed September 22, 2021).

Arshad, M. S., Haider Zaidi, S. M. I., and Mahmood, K. (2015). Self-esteem & academic performance among university students. J. Educ. Pract. 6, 156–162.

Chandratilake, M. N., and de Silva, N. R. (2009). Identifying poor concordance between the ‘planned’ and the ‘hidden’ curricula at a time of curriculum change in a Sri Lankan medical school. S. Asian J. Med. Educ. 3, 15–19.

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approach, 3rd Edn. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Inc.

Crossman, A. (2019). What is the Hidden Curriculum?. Available online at: http://www.thoughtco.com/hidden-curriculum-3026346 (accessed August 19, 2019).

Crossman, A. (2020). The Sociology of Social Inequality. Available online at: https://www.thoughtco.com/sociology-of-social-inequality-3026287 (accessed January 28, 2020).

Çubukçu, Z. (2012). The effect of hidden curriculum on character education process of primary school students. Educ. Sci. 12, 1526–1534.

Dombrovskis, A. (2016). “Identity and an identity crisis: the identity crisis of first-year female students at Latvian Universities and their socio-demographic indicators,” in Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference. I (Vladivostok: Far Eastern Federal University), 308–319. doi: 10.17770/sie2016vol1.1527

Drew, C. (2021). What is Hidden Curriculum? Available online at: https://helpfulprofessor.com/hidden-curriculum/ (accessed August 27, 2021).

Durand-Delvigne, A., and Duru-Bellat, M. (1998). A Hidden Curriculum? Coeducation and Gender Identity. Oxfordhire: Routledge.

Eisner, E. (2002). The Educational Imagination: On the Design and Evaluation of School Programs, 4th Edn. New York, NY: Macmillan.

Erol, R. Y., and Orth, U. (2011). Self-Esteem development from age 14 to 30 years: a longitudinal study. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 101, 607–619. doi: 10.1037/a0024299

Hafferty, F. W., and O’Donnell, J. F. (2015). The Hidden Curriculum in Health Professional Education. New England: Dartmouth College Press.

Haggar, R. (2013). Gender and Hidden Curriculum. Available online at: https://earlhamsociologypages.uk/gender-and-hidden-curriculum/ (accessed April 02, 2013).

Hansen, H. (2018). Social Identity–Hidden Curriculum. Available online at: https://hannahansenblog.wordpress.com/2018/03/14/social-identity-hidden-curriculum/ (accessed April 18, 2018).

Henderson, J. G., and Gornik, R. (2007). Transformative Curriculum Leadership, 3rd Edn. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill/Prentice Hall.

Hernández, M., González, P., and Sánchez, S. (2013). Gender and constructs from the hidden. Creat. Educ. 4, 89–92. doi: 10.4236/ce.2013.412A2013

Jerald, C. D. (2006). School Culture: The Hidden Curriculum. Available online at: https://www.readingrockets.org/article/school-culture-hidden-curriculum (accessed February 23, 2022).

Killick, D. (2016). The Role of the Hidden Curriculum: Institutional Messages of Inclusivity. Leeds: Leeds Beckett University.

Klein, D. N., Roman, K., and Bufferd, S. J. (2011). Personality and depression: explanatory models and review of the evidence. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 7, 269–295. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104540

Kohlhof, M. (2018). The College Identity Crisis: Who am I?. Available online at: https://www.theodysseyonline.com/college-identity-crisis (accessed August 4, 2021).

Kroger, J., Martinussen, M., and Marcia, J. E. (2010). Identity status change during adolescence and young adulthood: a meta-analysis. J. Adolesc. 33, 683–698. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.11.002

Lannegrand-Willems, L., and Bosma, H. A. (2006). Identity development-in-context: the school as an important context for identity development. Identity 6, 85–113. doi: 10.1207/s1532706xid0601_6

Leask, B. (2009). Using formal and informal curricula to improve interactions between home and international students. J. Stud. Int. Educ. 13, 205–221. doi: 10.1177/1028315308329786

Mahood, S. C. (2011). Medical education: beware the hidden curriculum. Can. Fam. Physician 57, 983–985.

Marcia, J. E. (1993). “The relational roots of identity,” in Discussions on Ego Identity, ed. J. Kroger (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum), 101–120.

Margolis, E., and Romero, M. (2001). “In the image and likeness,” in How Mentoring Functions in the Hidden Curriculum: The Hidden Curriculum in Higher Education, ed. E. Margolis (New York, NY: Routledge), 79–96.

Martin, J. (1976). What should we do with a hidden curriculum when we find one? Curric. Inq. 6, 135–151. doi: 10.2307/1179759

McCoy, D. (1990). The Impact of Socialization on Personality Formation and Gender Role Development. Available online at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/234645134The Impact_of_Socialization_ on_Personality_Formation_and_Gender_Role_Development (accessed December 8, 2021).

Meškauskienė, A. (2017). The impact of teaching environment on adolescent self–esteem formation. Eur. J. Soc. Sci. Educ. Res. 4, 112–120. doi: 10.26417/ejser.v10i1.p112-120

Neumark-Sztainer, D. R., Wall, M., Haines, J. I., Story, M. T., Sherwood, N. E., and van den Berg, P. A. (2007). Shared risk and protective factors for overweight and disordered eating in adolescents. Am. J. Prev. Med. 33, 359–369. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.07.031

Niebergal, J. A. (2010). Promoting Positive Identity Among Children in a School Curriculum. Available online at: https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/bitstream/handle/1808/6789/Niebergall_ku_0099M_10844_DATA_1.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y (accessed April 10, 2010).

Orth, U., and Robins, R. W. (2013). Understanding the link between low self-esteem, and depression. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 22, 455–460.

Pic Editor Review (2021). Explain the Links between Identity Self Image and Self Esteem. Available online at: https://piceditorreview.com/explain-the-links- between-identity-self-image-and-self-esteem/#:~:text=Explain%20the%20links %20between%20identity%20self%20image%20and,how%20we%20are%20and %20what%20we%20are%20worth (accessed May 27, 2021).

Portelli, J. P. (1993). ‘Exposing the hidden curriculum. J. Curr. Stud. 25, 343–358. doi: 10.1080/0022027930250404

Ray, P. K. (2019). The Hidden Curriculum. Available online at: https://pawan4job.blogspot.com/2019/04/the-hidden-curriculum.html (accessed April 16, 2019).

Rogers, A. (2014). Why Social Interaction is Fundamental to Shaping our Identity. Available online at: https://omdsaid.com/why-social-interaction-is-fundamental-to-shaping-our-identity/ (accesed November 11, 2014).

Ryan, T. (2008). The Hidden and Null vs Written Curriculums and the Juxtapositional Dynamic of the no Child Left behind Program Policy Implementation in the American Educational System. Available online at: https://www.academia.edu/31249001/The_Hidden_and_Null_Vs_Written_Curriculums_And_The_Juxtapositional_Dynamic_Of_The_No_Child_Left_Behind_Program_Policy_Implementation_In_The_American_Educational_System (accessed April 1, 2008).

Schwartz, S. J., Côté, J. E., and Arnett, J. J. (2005). Identity and agency in emerging adulthood: two developmental routes in the individualization process. Youth Soc. 37, 201–229. doi: 10.1177/0044118x05275965

Sharp, G. (2012). Gender in the Hidden Curriculum. Available online at: https://thesocietypages.org/socimages/2012/11/16/gender-in-the-hidden-curriculum/ (accessed November 16, 2012).

Shaw, S. M., Kleiber, D. A., and Caldwell, L. L. (1995). Leisure and identity formation in male and female adolescents: a preliminary examination. J. Leis. Res. 27, 245–263. doi: 10.1080/00222216.1995.11949747

Snyder, B. R. (1973). The Hidden Curriculum. Available online at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/thehiddencurriculum

Studios, Y. (2020). I am….:What Factors Really Influence Identity?. Available online at: https://ystudios.com/insights-people/influence-on-identity (accessed July 2, 2020).

Tsang, S. K. M., Eadaoin, K. P. H., and Bella, C. M. L. (2012). Positive identity as a positive youth development construct: a conceptual review. Sci. World J. 2012:529691. doi: 10.1100/2012/529691

Ullah, H., and Khan, A. N. (2018). The gendered classroom: masculinity and femininity in Pakistani universities. Lit. Inf. Comput. Educ. J. 9, 2810–2814. doi: 10.20533/licej.2040.2589.2018.0370

Valance, E. (1993). “Hiding the Hidden Curriculum: An Interpretation of Language of Justification in Nineteenth Century Educational Reform, eds H. Giroux and D. Purpel (Berkeley, CA: McCutchan Pub)

Verhoeven, M., Poorthuis, A. G., and Monique, V. (2018). The role of school in adolescents’ identity development: a literature review. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 31, 35–63. doi: 10.1007/s10648-018-9457-3

Watson, J. (2019). Why is Teen Identity Development Important? Available online at: https://aspiroadventure.com/blog/why-is-teen-identity-development- important/#:~:text=Identity% 20formation%20in%20teens%20is%20about%20 developing%20a,years%20but%20 for%20most%20of%20their%20adult%20life (accessed December 11, 2019).

White, E. G. (2020). Education and Character. Available online at: https://m.egwwritings.org/en/book/29.1170#1170. (accessed March 2, 2021).

Wilson, L. O. (2021). How Many Types of Curricula are You Familiar with?. Available online at: https://thesecondprinciple.com/instructional-design/types-of-curriculum/. (accessed June 11, 2021).

Yüksel, S. (2006). The role of hidden curriculum on the resistance behavior of undergraduate students in psychological counselling and guidance at a Turkish University. Asia Pac. Educ. Rev. 7, 94–107. doi: 10.1007/bf03036788

Keywords: self-identity, self-esteem, invisible curriculum, young people, depressive feelings

Citation: Nyamai DK (2022) The Invisible Curriculum’s Influence on Youth’s Self-Identity and Self-Esteem Development. Front. Educ. 7:583180. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.583180

Received: 14 July 2020; Accepted: 28 February 2022;

Published: 06 April 2022.

Edited by:

Douglas F. Kauffman, Medical University of the Americas – Nevis, United StatesReviewed by:

Chetan Sinha, O.P. Jindal Global University, IndiaShraddhesh Tiwari, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, India

Omar García Zabaleta, University of the Basque Country, Spain

Farzaneh Rashidi Fakari, North Khorasan University of Medical Sciences, Iran

Copyright © 2022 Nyamai. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Dinah K. Nyamai, ZGluYWgubnlhbWFpQGFpdS5hYy5rZQ==

Dinah K. Nyamai

Dinah K. Nyamai