- 1Department of Psychological Interventions, School of Psychology, University of Surrey, Guildford, United Kingdom

- 2Research and Development Department, Sussex Education Centre, Sussex Partnership NHS Foundation Trust, Brighton and Hove, United Kingdom

Background: Self-harm is a major public health concern with evidence suggesting that the rates are higher in the United Kingdom than anywhere else in Europe. Increasingly, policy highlights the role of school staff in supporting young people (YP) who are self-harming, yet research indicates that school staff often feel ill-equipped to provide support and address self-harm behaviors. Here, we assess the impact of a bespoke eLearning module for United Kingdom secondary school teachers on teacher’s actual and perceived knowledge of self-harm, and their self-reported confidence in supporting and talking to YP who self-harm.

Methods: Twenty-one secondary schools across the West Midlands and South East of England were invited to complete a 30-min web-based eLearning module on self-harm in schools. Participants completed pre-and post-intervention measures.

Results: One-hundred and seventy-three teachers completed the eLearning, and pre-and post-measures. The eLearning significantly enhanced participants’ perceived knowledge, actual knowledge, and confidence in talking to and supporting YP who self-harm. The majority of participants (90.7%) felt that eLearning was a good way to receive training.

Conclusion: The 30-min eLearning module was rated highly and may be an effective way to increase secondary school teachers’ knowledge of self-harm, and confidence in supporting and talking to YP who self-harm.

Introduction

Self-harm is increasing rapidly in young people (YP), worldwide. A recent meta-analysis including 686,672 YP estimated the aggregate lifetime prevalence of deliberate self-harm at 13.7% (Lim et al., 2019). There is a pressing need to develop strategies to address the rising prevalence of self-harm in YP, as highlighted in a range of international policy documents (World Health Organization, 2013). This is needed now, more than ever before, given the negative impact of the coronavirus pandemic on YP’s mental health, with a reported increase in self-harm during the pandemic (Carr et al., 2021; Robillard et al., 2021; Zetterqvist et al., 2021).

School staff are well placed to offer YP support and are often expected to manage low level incidences of self-harm in schools, but most feel ill-equipped (Evans and Hurrell, 2016). Young Minds & Cello’s Talking Taboos (2012), a leading charity for YP’s mental health, recently called for greater support and training for school staff who may be working with YP who self-harm, and the United Kingdom government’s best practice guidance states that all staff working in schools should receive training on self-harm. School staff are often the first point of call for YP experiencing self-harm, with figures from the United Kingdom suggesting 48% of YP had sought help from their teachers (NHS Digital, 2017). Whilst school staff welcome new responsibilities around mental health, they believe they do not have sufficient training to do so, and support the need for further training around self-harm and closer working with the health sector (Evans et al., 2019; Pierret et al., 2020).

Although school staff are not mental health professionals, many are involved in conversations around self-harm with YP, despite minimal training (Evans and Hurrell, 2016). Discussions around self-harm with school staff can support YP to seek further help, but only when teachers are perceived to be understanding and supportive (Hasking et al., 2015). However, self-harm can be perceived as “bad behaviour” by some school staff, who may misinterpret self-harm as attention-seeking or manipulative (Heath et al., 2011; Evans and Hurrell, 2016). School staff beliefs around self-harm impact the type of support offered to YP, for example Heath et al. (2011) reported that 60% of high school teachers found the idea of self-harm “horrifying” and this belief was associated with staff feeling less comfortable supporting a student who had self-harmed. Furthermore, Timson et al. (2012) found that school staff with more negative attitudes toward self-harm, also had inferior knowledge, and felt less effective in supporting students who self-harm. In addition to staff knowledge around self-harm, YP can feel cautious about discussing self-harm with school staff for fear of a negative response, and concerns regarding confidentiality (Evans and Hurrell, 2016).

Training and education for school staff around early identification, safeguarding, and signposting to more appropriate support, is one proposed strategy to address these concerns. School staff who receive training respond better to YP who self-harm, than their less experienced colleagues (Dowling and Doyle, 2017). A recent systematic review found that training interventions targeting skills and knowledge around self-harm were effective in supporting school staff to respond to YP who self-harm (Pierret et al., 2020). However, whilst effective mental health training resources have been developed for school staff, major problems persist. This may be due to the lack of effective implementation of training resources in busy school settings, and the use of inappropriate delivery modes and platforms, which requires a systemic approach guided by stakeholder discussions, theory, and the evidence base. eLearning packages, informed by psychological theory, provide a potential solution, delivering information efficiently, and often at low cost. As such, the delivery of eLearning packages to support knowledge of self-harm in teaching staff, is one approach that may be both efficient, and meet the needs of the student population. No such intervention has been tested in the United Kingdom.

Here, we describe the impact of a bespoke, theoretically informed eLearning module for United Kingdom secondary school teachers on actual and perceived knowledge of self-harm, and teachers self-reported confidence in supporting and talking to YP who self-harm.

Materials and Methods

Development of the eLearning Module

The eLearning module is a psychoeducation intervention for secondary school teachers, to support conversations around self-harm. The module takes approximately 30-min to complete and is delivered online. The eLearning module is designed to improve teachers perceived confidence in talking to, and supporting YP who self-harm, as well as perceived and actual knowledge around self-harm.

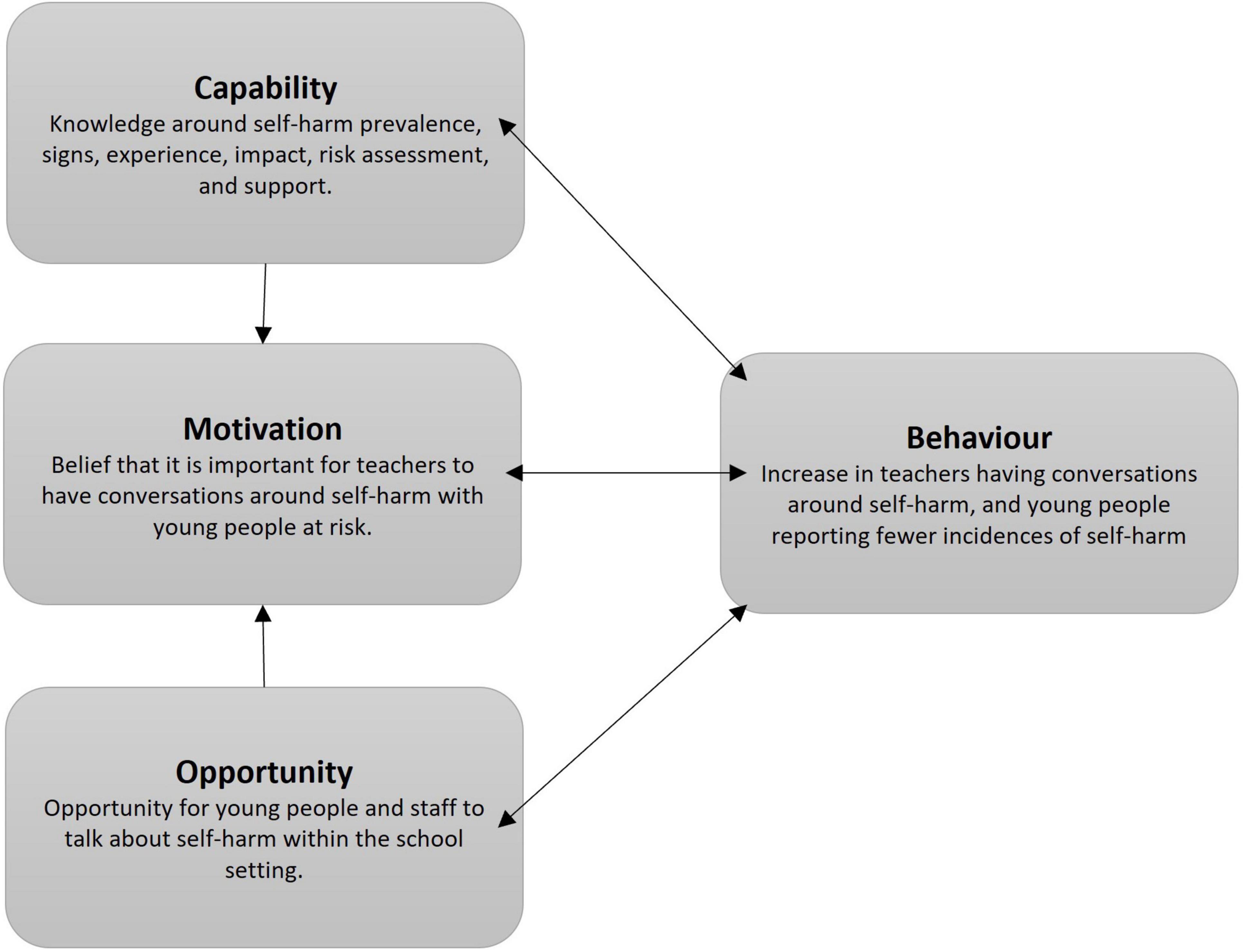

The module uses a range of accessible and engaging delivery methods informed by the evidence base for eLearning, and the behavior change literature (Michie et al., 2011; Regmi and Jones, 2020). The eLearning module drew on psychological theories of change, namely the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation – Behavior (COM-B) framework, and was developed and refined in consultation with an expert advisory group.

Expert Advisory Group

The research team took part in a series of iterative, individual discussions with a head teacher, mental health professionals (n = 3), and consultation with an eLearning development company, to inform intervention content and delivery. Experts described their knowledge about self-harm in YP, the challenges of addressing self-harm in schools, and current approaches to support YP’s wellbeing. Concordant with the evidence base, experts described limited training in self-harm, which was often embedded into wider school teaching around health and wellbeing. Through these discussions, it became evident that a lack of time and resource in schools were barriers to teachers engaging in training around self-harm, and mental wellbeing more broadly. To address these challenges, a free, brief, eLearning module was identified as a way to improve secondary school teachers perceived and actual knowledge around self-harm, and confidence in talking to and supporting YP who self-harm. Discussions with experts were mapped onto the COM-B model, and the behavior change wheel to inform eLearning module content.

The Capability, Opportunity, Motivation – Behavior Framework

Michie et al.’s (2011) behavioral change wheel and COM-B framework provided the psychological theory underlying the eLearning module, and a systematic approach to guide module development. The COM-B framework proposes that behavior change is determined by capability (ability to enact the behavior), motivation (mechanisms that activate or inhibit behavior), and opportunity (environmental structures enabling behavior). The behavior change wheel provides guidance on how to identify intervention approaches that address the behavioral barriers and facilitators identified through the COM-B model. Extensive literature has already identified barriers including a lack of time, resource, knowledge, and confidence, which are particularly relevant for addressing self-harm in busy school settings (Pierret et al., 2020). The hypothesized active components of the eLearning module have been mapped against the COM-B framework to evidence the proposed mechanisms through which the module becomes effective (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mapping eLearning module to the COM-B framework. All three components, capability, opportunity, and motivation influence behavior, and behavior can influence capability, motivation and opportunity, as indicated by the arrows.

The purpose of this eLearning module was to increase effective conversations between teachers and YP around self-harm, and signposting to adequate support, to ultimately reduce the incidence of self-harm in YP. These behavioral outcomes were not measured in the present study, instead, we focus on the first stage in the behavior change trajectory, developing strategies to influence teachers actual and perceived knowledge of self-harm. The eLearning module hopes to achieve this through targeting teacher’s capability through supporting knowledge around self-harm (e.g., prevalence, signs, risk assessment, support), through targeting teacher’s motivation to have conversations with YP at risk of self-harm, and opportunity by supporting an environment in which teachers and YP can have conversations around self-harm. The module also provides an opportunity for the individual to reflect on their own assumptions, reducing the opportunity for shaming experiences around self-harm.

The final iteration of the module was reviewed by two secondary school teachers, four members of the public, an eLearning developer with a medical background, and a Clinical Psychologist, who were purposely selected to ensure variability in experiences. The resulting module provided approximately 30 min of learning, although participants could complete this at their own pace and review module content as needed. The module content was designed to address capability through providing information on the prevalence of self-harm, help-seeking and warning signs in YP, reasons why people may self-harm, the vicious cycle of self-harm, methods of self-harm, and assessing risk. The module provides the opportunity for participants to reflect on their feelings and assumptions around self-harm and dispels myths surrounding the topic. It also provided communication tips, in how to build trust, how to have conversations about self-harm, and addresses issues around confidentiality. Resources and signposting information were provided, and case studies and quizzes were used to aid learning. Building on conversation with experts, to address teacher’s opportunity to complete the eLearning, the implementation plan involved engagement with senior school staff, and finding time within the school day, during professional development hours, to complete the module, in line with the goals and planning cluster within the behavior change taxonomy. Motivation to complete eLearning was targeted via the delivery of certificates on Continuing Professional Development for those who completed the module.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Qualified teachers in mainstream secondary schools within the United Kingdom, who had access to a computer, and basic computer skills were eligible to take part. For this purpose of this study, non-qualified teachers, or teaching assistants, non-teaching school staff, and junior/infant/special educational needs schoolteachers were not eligible to take part. None of the teachers involved in the development process were invited to participate.

Procedure

Eligible participants were recruited using opportunity and snowball sampling. Twenty-one senior members of school staff were contacted via email to ask if they would like their school to participate in the research, an advertisement leaflet was also attached. Senior members of staff emailed teachers (participants) with the participant information sheet, and instructions on how to access the training. A consent form was built into the eLearning module, which made clear that the post-intervention questionnaire was optional, and participants could withdraw from the study at any time without repercussion and that any data generated from questionnaires and through interaction with the learning would be anonymized.

Participants were asked to complete a questionnaire assessing self-harm knowledge, perceived knowledge, and confidence, immediately before and after completing the eLearning module. On completion of the eLearning module, participants could download a personalized certificate of Continuing Professional Development.

Measures

Participants were invited to complete the following questionnaires before and immediately after completing the eLearning module.

The Self-Injury Knowledge Questionnaire (Jeffery and Warm, 2002) was used to measure actual knowledge of self-harm. This 20-item questionnaire includes 10 accurate statements about self-harm and 10 myths. Participants are asked to rate whether they agree or disagree with the statements on a 5-point Likert scale. One item was updated from “Everybody who self-harms suffers from Munchausen’s Disease” to “Everybody who self-harms suffers from mental health problems.”

Three items were developed for this study, to assess perceived level of knowledge of self-harm, confidence in supporting YP who self-harm, and confidence in talking to YP about self-harm (e.g., How confident do you feel in talking to a young person about self-harm?). Participants were asked to rate their responses on a Visual Analog Scale, with 0 being the least confident/knowledge, and 10 being the most confident/knowledge.

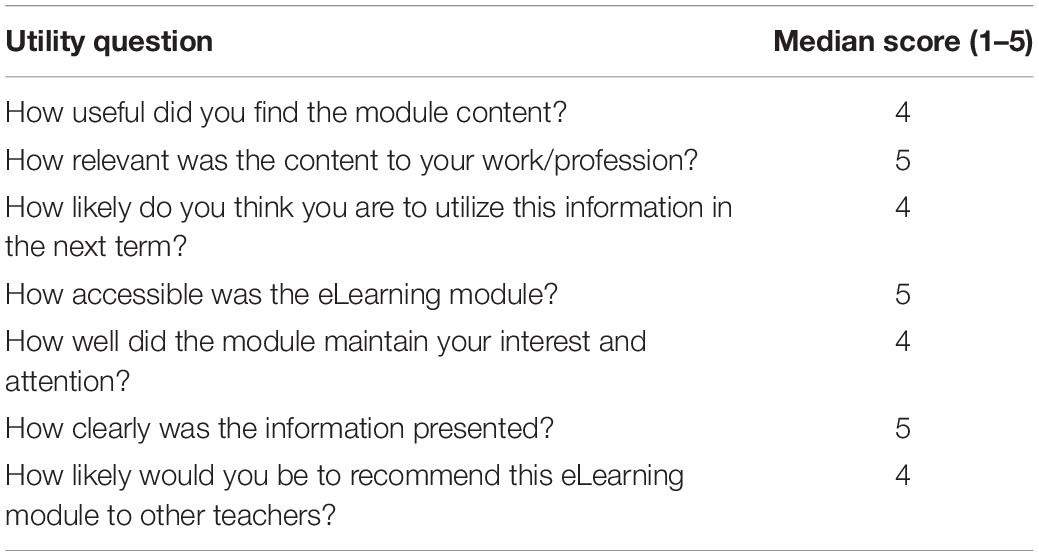

Post-eLearning participants were invited to complete a 5-point utility scale to gain feedback on the content, accessibility, relevance, presentation, likelihood of participants utilizing training the following term, whether eLearning-maintained interest and attention, and how likely they would be to recommend the training to another teaching colleague.

Analysis

Descriptive data was used to describe participant characteristics, prior training experiences, and perceived utility of the eLearning module. The data presented here did not meet parametric assumptions, as such, non-parametric analyses were completed. Wilcoxon’s Signed rank tests were used to explore differences in participants knowledge and confidence pre and post training. To examine the effect influence of prior training, subgroup analyses were performed on those who had (and had not) reported prior training around self-harm, using a Kruskal–Wallis test. A Bonferroni correction test for multiple comparisons was employed, as such, a revised p-value of 0.01 was used when analyzing the data. Participants who did not complete the post training questionnaire were excluded from analyses.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences Ethics Committee (FMHS) at University of Surrey.

Results

In total, 10 schools agreed to distribute the eLearning module to teaching staff (6 schools from South East England, and 4 from the West Midlands). Two schools made the training mandatory for all staff, whereas teaching staff at the remaining eight schools passed on information about the eLearning module to their colleagues. The researchers were informed via email by some participants that training had been passed onto to other teacher colleagues at additional schools. It was not possible to report how many teachers from additional schools also participated in this research, and teachers from other schools were not included in the analysis.

A total of 225 teachers completed the pre-training questionnaires, eLearning module, and gained their certificate of continuing professional development. Only 173 (76.9%) of these teachers completed the post-training questionnaires; there were no significant differences in knowledge of self-harm, age, or experience of participants between participants who completed the post-intervention measures and those who did not. The analysis presented here related to the 173 participants who completed the pre- and post-training questionnaires.

Participants

The majority, 61.3% had qualified teacher status for at least 6 years, 97.1% worked at a state/comprehensive/academy school, with 2.9% working in private schools. The majority (70.5%) had not received any specific training on self-harm prior to the eLearning module, and 55.4% reported that their school did not have a specific policy relating to self-harm.

Pre-training

Prior to completing the eLearning module, 58.5% of participants believed a student in their class had self-harmed, of these, 64% reported they did not talk to the student about this. Participants who had received prior training on self-harm reported higher perceived knowledge scores at baseline, compared to those with no previous training [χ2(2) = 16.53, p = < 0.001], felt more confident in supporting YP who self-harm [χ2(2) = 15.91, p = < 0.001], and felt more confident in talking to YP who self-harm [χ2(2) = 15.59, p = < 0.001]. However, those that had previous training did not appear to perform significantly better on the Self-Injury Knowledge Questionnaire pre-training [χ2(2) = 1.55, p = 0.46].

Impact of eLearning Module

Overall the eLearning appeared beneficial; according to self-report measures, participants perceived knowledge of self-harm significantly increased post training (z = 10.77, p < 0.001, r = 0.82), as did perceived confidence in supporting YP who self-harm (z = 10.86, p < 0.001, r = 0.83), and perceived confidence in talking to YP who self-harm (z = 10.22, p < 0.001, r = 0.78). The training also appeared beneficial for participants actual knowledge around self-harm, with participant knowledge of self-harm increasing significantly post intervention (z = 9.62, p < 0.001, r = 0.73).

Impact of Previous Training

Subgroup analyses revealed that the eLearning module had a greater impact on participants who had not had previous training around self-harm. These participants demonstrated greater perceived knowledge post-training, than those who had received prior training [χ2(2) = 11.79, p = 0.003], more perceived confidence in supporting YP who self-harm [χ2(2) = 12.77, p = 0.002], and more perceived confidence in talking to YP who self-harm [χ2(2) = 16.28, p = < 0.001]. There was no difference across groups for self-harm knowledge.

According to self-report measures around knowledge assessment immediately following training, sensitivity analyses revealed the eLearning training may have been beneficial for participants, regardless of previous training experience (perceived knowledge z = −9.23, p < 0.001; confidence to support z = −9.24, p < 0.001; confidence to talk z = −8.98, p < 0.001; actual knowledge z = −8.5, p < 0.001).

Utility of the eLearning Module

Most participants (90.7%, n = 157) reported that the eLearning was a beneficial way to receive training. The content of the module, and relevance to the teaching profession were rated highly, and participants felt they were likely to use the information from the eLearning module in the following school term. In addition, participants reported that the eLearning maintained their interest and attention, information was presented well, the eLearning was accessible, and most would recommend the eLearning to a colleague (see Table 1 for median ratings).

Discussion

The aim of this research was to investigate whether a brief, eLearning module could improve United Kingdom secondary school teachers knowledge and self-reported confidence in supporting and talking to YP who self-harm. The training improved perceived knowledge, actual knowledge, confidence in supporting YP who self-harm, and confidence in talking to a YP about self-harm, as assessed through self-report questionnaires. Additionally, the eLearning module appeared acceptable, with participants recommending the training to their colleagues.

In line with previous work, this eLearning module appeared to improve participants confidence and knowledge around self-harm in YP (Pierret et al., 2020). Our research also found that compared to teachers who had previously received no training around self-harm, perceived knowledge and confidence was greater for teaching staff with prior training in self-harm; however, staff with and without prior training were comparable in terms of actual knowledge around self-harm. One interpretation of these findings is that information gained from prior training was not retained, however, it is unclear here how long ago participants had received prior training. Similarly, prior work indicates that although knowledge around self-harm may improve post intervention, across studies, these results are not maintained at 6 months post training (Pierret et al., 2020). In combination with our work, this suggests that teachers who have received training around self-harm may overestimate their knowledge, which may result in incidences of self-harm being inappropriately managed. Alternatively, previous training may not have addressed the aspects of self-harm included within the Self-Injury Knowledge questionnaire.

Our work highlights not only the potential for an effective eLearning module, but also suggests this is an acceptable way to deliver training across school staff. Most participants completing the eLearning felt this was a helpful way to receive the training, and ensured the training was accessible. The training was passed on by participants to staff at other teaching schools, again highlighting the accessibility and perceived utility of this module. This is particularly important against the current background of cuts to school resources, staffing, and limited time for training. Given this context, eLearning may be one way to encourage early conversations around self-harm, early identification and safeguarding of YP in need, and signposting to adequate mental health support. In line with current policy, we recommend that eLearning is implemented as one aspect of a whole school approach to mental health promotion, which includes a focus on curriculum, teaching, and learning, school ethics and environment, as well as family and community partnerships, and collaboration with the health sector (Wyn et al., 2000). eLearning in isolation, is unlikely to be enough to address the mental health needs of YP, and needs of teachers in secondary schools, but forms one evidence-based component of a whole school approach.

Limitations and Future Research

The lack of follow-up beyond immediate post eLearning assessment prevents any conclusions about the long-term impact of the eLearning module on teacher’s competence and confidence around self-harm. Longitudinal studies are essential to determining the sustained impact of eLearning and provide guidance around the frequency of delivery. This is particularly important given the evidence presented here that suggest that information gained from prior training around self-harm did not appear to be retained across participants, and may have resulted in unfounded confidence in one’s beliefs around self-harm, and potentially inappropriate management of self-harm. This highlights the need for ongoing monitoring around self-harm knowledge post-training, and suggests that additional support or training may be warranted. In the current project, teachers were not provided with feedback on their knowledge tests post-eLearning, in line with behavioral change principles, this may be one approach that targets overestimation of knowledge around self-harm and provides feedback on individuals strengths and learning needs (Larson et al., 2014).

The eLearning module appeared beneficial for self-reported increases in teacher knowledge and confidence around addressing self-harm in YP, however, the eLearning model was informed by the COM-B framework. Whilst behavior change is a key aspect of mental health promotion, additional variables including social and emotional variables may need embedding to effectively address self-harm in YP across school settings (Hetrich et al., 2020). In addition, there is a need for further work to assess the active components of the eLearning module mapped onto the COM-B framework, and whether this results in a behavioral change across teaching staff, and a change in YP’s wellbeing. Completion of online eLearning does not mean the eLearning skills are delivered in practice, and the impact on YP is unclear.

An in-depth understanding of the implementation of the eLearning module in school settings is required before embedding into routine practice. In addition, although eLearning may be perceived as an efficient and accessible way of supporting teachers, future studies on the cost-effectiveness of embedding eLearning within secondary schools are required. Furthermore, the eLearning module delivered here was provided to teaching staff, although there was interest and requests to expand the module to additional members of school staff. Given the numbers of school staff, and frequent interactions with YP in the school setting, we believe it worthwhile examining the effectiveness of eLearning across the range of school staff (e.g., administrative staff, technical staff, teaching assistants, and site staff).

Implications

The observation that teachers completing 30-min eLearning had a positive impact on self-reported confidence and knowledge in regard to managing self-harm, suggests that the use of eLearning for self-harm may be valuable across school settings. However, given the current evidence base which indicates that on its own, information obtained from brief training may not be retained overtime, it likely that a wider system change is needed to address self-harm in schools (Pierret et al., 2020). Brief, eLearning is only one part of this approach. In line with current government frameworks, we propose that eLearning may be embedded as part of a wider program identifying and supporting mental health in YP attending secondary schools. In line with other authors suggestions (Townsend et al., 2022), we anticipate that eLearning may support in the upskilling of teachers, and additional members of school staff, and reduce the rates of self-harm in YP as well as increasing confidence in talking to YP on sensitive topics but further work is required.

Conclusion

The eLearning module was rated highly and was reported to be a good modality through which to receive training. The module was effective at improving confidence and knowledge in how to support a young person who is self-harming. However, further research is needed to investigate whether these effects are maintained long-term, and the impact on YP’s wellbeing.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences Ethics Committee (FMHS) at University of Surrey. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

CP conceptualized and designed the study and analyzed and managed the data and wrote the manuscript with support from MJ, R-MS, and CJ. MJ supervised the project. CJ and R-MS contributed substantive content related to behavior change and relevant literature. All authors reviewed and commented on multiple drafts of the manuscript, and played a key role in the interpretation and clinical relevance of study results.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Nicholas Blackwell and Sarah Pontefract who supported in the design of the e-learning module.

References

Carr, M. J., Steeg, S., Webb, R. T., Kapur, N., Chew-Graham, C. A., Abel, K. M., et al. (2021). Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on primary care-recorded mental illness and self-harm episodes in the UK: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Public Health 6, E124–E135. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30288-7

Dowling, S., and Doyle, L. (2017). Responding to self-harm in the school setting: the experience of guidance counsellors and teachers in Ireland. Br. J. Guidance Counsel. 45, 583–592. doi: 10.1080/03069885.2016.1164297

Evans, R., and Hurrell, C. (2016). The role of schools on children and young people’s self-harm and suicide: systematic review and meta-ethnography of qualitative research. BMC Public Health 16:404. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3065-2

Evans, R., Parker, R., Russell, A. E., Mathews, F., Ford, T., Hewitt, G., et al. (2019). Adolescent self-harm prevention and intervention in secondary schools: a survey of staff in England and Wales. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 24, 230–238. doi: 10.1111/camh.12308

Hasking, P., Rees, C. S., Martin, G., and Quigley, J. (2015). What happens when you tell someone you self-injure? The effects of disclosing NSSI to adults and peers. BMC Public Health 15:1039. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2383-0

Heath, N., Toste, J., Sornberger, M., and Wagner, C. (2011). Teachers’ perceptions of non-suicidal self-injury in the schools. Sch. Ment. Health 3, 35–43. doi: 10.1007/s12310-010-9043-4

Hetrich, S. E., Subasinghe, A., Anglin, K., Hart, L., Morgan, A., and Robinson, J. (2020). Understanding the needs of young people who engage in self-harm: a qualitative investigation. Front. Psychol. 10:2916. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02916

Jeffery, D., and Warm, A. (2002). A study of service providers’ understanding of self-harm. J. Ment. Health 11, 295–303. doi: 10.1080/09638230020023679

Larson, E. L., Patel, S. J., Evans, D., and Saiman, L. (2014). Feedback as a strategy to change behaviour: the devil is in the details. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 19, 230–234. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01801.x

Lim, K. S., Wong, C. H., McIntyre, R. S., Wang, J., Zhang, Z., Tran, B. X., et al. (2019). Global lifetime and 12-month prevalence of suicidal behavior, deliberate self-harm and non-suicidal self-injury in children and adolescents between 1989 and 2018: a meta-analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 19:4581. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16224581

Michie, S., van Stralen, M. M., and West, R. (2011). The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 6:42. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

NHS Digital (2017). Mental Health of Children and Young People in England. Available online at: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mental-health-of-children-and-young-people-in-england/2017/2017 (accessed March 1, 2022).

Pierret, A. C. S., Anderson, J. K., Ford, T. J., and Burn, A. M. (2020). Review: education and training interventions, and support tools for school staff to adequately respond to young people who disclose self-harm - a systematic literature review of effectiveness, feasibility and acceptability. Child Adolesc. Ment. Health 27, 161–172. doi: 10.1111/camh.12436

Regmi, K., and Jones, L. (2020). A systematic review of the factors – enablers and barriers – affecting e-learning in health sciences education. BMC Med. Educ. 20:91. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02007-6

Robillard, C. L., Turner, B. J., Ames, M. E., and Craig, S. G. (2021). Deliberate self-harm in adolescents during COVID-19: the roles of pandemic-related stress, emotion regulation difficulties, and social distancing. Psychiatry Res. 304:114152. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114152

Timson, D., Priest, H., and Clark-Carter, D. (2012). Adolescents who self-harm: professional staff knowledge, attitudes and training needs. J. Adolesc. 35, 1307–1314. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.05.001

Townsend, M. L., Jain, A., Miller, C. E., and Grenyer, B. F. S. (2022). Prevalence, response and management of self-harm in school children under 13 years of age: a qualitative study. Sch. Ment. Health [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1007/s12310-021-09494-y

World Health Organization (2013). Mental Health Action Plan 2013-2020. Available online at: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241506021 (accessed March 1, 2022).

Wyn, J., Cahill, H., Holdsworth, R., Rowling, L., and Carson, S. (2000). MindMatters, a whole-school approach promoting mental health and wellbeing. Austral. N. Zeal. J. Psychiatry 34, 594–601. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2000.00748.x

Young Minds & Cello’s Talking Taboos (2012). Talking Self-Harm. Available online at: https://talkingtaboos.com/our-work/talking-self-harm (accessed August 31, 2020).

Keywords: self-harm, young people, teachers, eLearning, school

Citation: Price C, Satherley R-M, Jones CJ and John M (2022) Development and Evaluation of an eLearning Training Module to Improve United Kingdom Secondary School Teachers’ Knowledge and Confidence in Supporting Young People Who Self-Harm. Front. Educ. 7:889659. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.889659

Received: 04 March 2022; Accepted: 11 May 2022;

Published: 20 June 2022.

Edited by:

Susan Rasmussen, University of Strathclyde, United KingdomReviewed by:

Katrina Roen, University of Waikato, New ZealandZoe A. Morris, Monash University, Australia

Copyright © 2022 Price, Satherley, Jones and John. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rose-Marie Satherley, ci5zYXRoZXJsZXlAc3VycmV5LmFjLnVr

Claire Price1

Claire Price1 Rose-Marie Satherley

Rose-Marie Satherley Christina J. Jones

Christina J. Jones