- Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LIfBi), Bamberg, Germany

Academic achievement and educational decisions, which are strongly related to primary and secondary effects, are the two main drivers behind the emergence of social inequality in education. To understand this process in more detail, even before final decisions have to be made, the reciprocal influence of achievement and aspirations is of greatest interest. By not simply looking at an ultimate outcome but investigating its antecedents in a longitudinal fashion over the course of multiple years more insight is gained. Using German large-scale NEPS panel data, it is possible to demonstrate this co-development quantitatively. Cross-lagged panel models are utilized to show that the achievement in mathematics (measured by comprehensive achievement tests) and parental realistic aspirations influence each other positively in a statistically significant way over the course of primary education from grade one to four, even under the control of various potential confounding variables. Further analyses reveal that this process is socially stratified and works differently for lowly and highly educated families. Lower educated parents pay more attention to the performance of the child when adjusting their aspirations than tertiary educated parents, who always hold high aspirations. The results are of interest to understand in more detail how social inequality emerges at a very early point in the highly tracked German educational system.

Introduction

Understanding and explaining how individuals decide for or against educational pathways is one of the most prominent themes in sociology and educational sciences (Breen and Yaish, 2006). While these decisions are clearly of greatest interest, especially for investigating how social inequality emerges or grows over time, focusing on these specific points in time, which are rather few when the entire life course is considered, will hardly ever give a complete picture of the situation as they are not able to fully explain the process behind these decisions. In this context, social inequality means the unequal chances individuals are facing with respect to obtaining formal educational qualifications, caused by differences in their social origin (especially different level of parental education or the financial means of the family). Overall, one can consider these decisions the final consequence of longer lasting developments, which are, due to their extended temporal nature, much harder to understand and particularly to capture using survey methods. Nevertheless, these processes are of immense importance and relevant to better understand how and why decisions are made. Especially so in the German educational system, which makes families decide the educational trajectories of their children at a very young age (Schindler, 2017). As will be outlined in more detail below, the interplay of academic performance and educational aspirations is the defining aspect of this development as they comprise both primary and secondary effects (Boudon, 1974; Neugebauer et al., 2013). Here, primary effects are differences between social groups with respect to actual performance while secondary effects are differences in decisions, even when holding performance constant. Their independent influence on subsequent educational decisions has been well-researched in the past but it is only little understood how these two influence each other dynamically over time (Pietsch and Stubbe, 2007; Buchholz et al., 2016). Due to the early age of the children in primary school and the usually decisive influence of the parents, as will be further outlined below, parental aspirations are the focus of the following analyses. Exemplary, parents may adjust their aspirations continuously, depending on the feedback they receive from the performance of their children in school. Conversely, it makes sense to assume that parents with initially high aspirations will try to influence the academic performance of their offspring, especially when it lags behind expectations. Capturing and measuring these processes in a quantitative fashion appears to be a major interest for educational research. This knowledge is critical to assess how early and how strong social inequality develops in the German system. Thus, the overarching research questions that are guiding the following analyses are: how do parental educational aspirations and the achievement of children co-develop over the course of primary education in Germany? Is this process socially stratified?

To summarize, the following study contributes to the literature in various aspects. First, a theoretical framework is built upon well-established sociological theories that integrate both primary and secondary effects in a longitudinal fashion and allow to capture a dynamic feedback process. Second, it introduces a large-scale and high-quality German panel dataset that makes it possible to investigate named theoretical aspects empirically using a large number of relevant variables and account for potential confounding. Third, it contributes to the ongoing discussion of selecting an appropriate statistical model to answer posed questions for these dynamic feedback loops. Finally, by considering socially stratified effects the study makes it clear how early these social differentials emerge and how they contribute to social inequality that increases over the course of primary and secondary education. Overall, empirical evidence is provided that might be relevant for the evaluation and adjustment of policy to reduce the emergence of social inequality at a very early point in the life course.

Materials and methods

Theoretical considerations

In this chapter theoretical arguments will be presented. First, an explanation of how early educational aspirations develop will be given. Second, following the theoretical account, testable hypotheses are formulated that will guide the following empirical analyses. Third, previous research results are summarized to give an overview of the current state of knowledge.

The early development of educational aspirations

Theoretically, parents can have aspirations for their child even before it is born, particularly regarding idealistic aspirations. These are not grounded in any known limitations or restrictions, and only express wishes and ambitions. Generally, one can define aspirations as a “cognitive orientational aspect of goal-directed behavior” (Haller, 1968, 484). The realistic aspirations, which are the focus of the following study, can thus be understood as a compromise between the idealistic aspirations and any given limitations. These can be financial (costs of schooling or forgone wages), social or academic. In the German system, this last aspect is usually the most relevant one since schooling is free of charge, and pupils are sorted by ability in an early and strongly tracked system (Eckhardt, 2017). Consequently, as the child develops, parents will usually update their aspirations based on the general cognitive and academic performance of the child. One can assume that this is a dynamic feedback process as parents receive information on their child through his or her behavior, notions, and interests. Then they can either try to influence the performance of their child or readjust their aspirations. This becomes especially relevant as soon as the child enters primary education (aged 6 to 7 years), which lasts four years in most federal states. Afterward, pupils are sorted by their ability (choice of secondary schooling). Hence, these four years are highly relevant to develop and recognize the overall academic ability and interests of the child. One can also assume that this is a dynamic process between parents and children (as they influence each other). However, since one of the strongest sources of filial aspirations is the parental ones (Sewell and Hauser, 1980; Gölz and Wohlkinger, 2019), it makes sense to focus specifically on the parental aspirations. What must also be considered is that a child in primary school is usually not able to grasp the overall importance of education and the meaning of various educational qualifications. Therefore, looking especially at parental realistic aspirations makes more sense at this young age.1 It has been demonstrated empirically that aspirations mediate up to 80% of the effect social origin exerts on secondary school track choice in Germany and that the most relevant explanatory factor is parental realistic aspirations (Bittmann, 2022). Nonetheless, these explanations which are based on the influence of significant others, better known as the Wisconsin model of status attainment, usually assume rather constant aspirations and are therefore not detailed enough to explain why aspirations should change, as the significant others (e.g., parents, teachers, family or friends) are normally steady (Sewell and Hauser, 1993; Andrew and Hauser, 2011). To gather further insight, one can invoke well-accepted theories that focus on rational deliberations, which are an important complement.

According to theories of rational choice and derived formalized frameworks, parents want their children to at least reproduce their social status to avoid social demotion, which is referred to as the concept of status maintenance or relative risk aversion (Breen and Goldthorpe, 1997; Stocké, 2010). The initial aspirations are hence based on the parental social status and the respective educational qualifications. Therefore, highly educated parents have a strong incentive for their child to reproduce their status (and educational qualification), which requires showing high academic performance in school. For children of parents with low qualifications, this is apparently different as even mediocre performance will be sufficient to reproduce the parental status. Thus, the initial aspirations are probably based on status and qualifications, which are usually rather constant. So why would parents modify their aspirations at all? Following arguments of rational choice theory, adjustments are required whenever some parameters change. For example, if it turns out that the ability of the child is too low and entering the academic track is hence not feasible, parents will adapt their aspirations to avoid additional costs (dropping out of the academic track before completion). As in the German system, academic performance is the most relevant factor for sorting and assessing pupils, it makes sense to focus on this aspect. The most relevant distinction between the Wisconsin model of status attainment and most rational choice theories is that in the former, aspirations and expectations are seen as rather constant and mostly depending on the (usual not changing) social status of the family, while the latter invoke aspects like Bayesian learning or information updating, meaning that parents can continuously adapt their beliefs whenever they receive new information (Morgan, 2005). If this holds, it means that aspirations are potentially in constant flux as some information emerges over time as the child matures (for example, interests and abilities). Others are provided by the school in form of tests and grades, which can also be regarded as a rather continuous process since in primary schooling multiple smaller tests are held, distributed over the entire year. The final grade is therefore only a summary of the information parents have received earlier on. For the posed research questions this seems especially relevant as a development (and not an event) is investigated that assumes that parents are actually able to change their aspirations. There is some good evidence available that this is actually the case and that both children and parents adapt their aspirations (Andrew and Hauser, 2011; Carolan, 2017; Forster, 2021). As should be made clear, these studies usually rely on a drastic external shock (e.g., track placement after primary schooling), which is often not anticipated and is therefore a strong and sudden update to the beliefs of the families. The question arises whether updates of aspirations will also occur continuously over time in the absence of strong shocks but depending on a steady yet important influx of new information (for example, through schooling grades or developing interests of children). Also of great relevance is that this process differs, depending on the social status of the family (Karlson, 2015, 2019). The studies highlight that high-achieving pupils from socially disadvantaged families have the strongest reactions to signals about academic achievement when aspirations are adapted. This shows that socially stratified effects exist. As another study reports, in the German system, both the Wisconsin model as well as theories of information updating are valid and contribute to an explanation of social inequality with respect to differences in decision-making (Zimmermann, 2020).

Co-development and hypotheses

After having outlined the theoretical aspects of performance and aspirations separately it is now necessary to form an integrated model that explains how these two aspects can influence each other for guiding the following analyses. Theoretically, there are various arguments why crossed effects should be present, meaning that aspirations can influence performance and the other way round as well. In this section, all aspirations are meant as realistic aspirations (already shortly discussed before) since only those are subject to continuous updating.2 Starting with aspirations, it makes sense that parents with initially high aspirations will attempt to influence the performance of their children, especially when it falls behind expectations. Parents are well aware of the fact that certain levels of performance are required to persist in the most demanding schooling tracks, even in the absence of binding teacher recommendations (Bittmann, 2021). If the grades attained are not good enough, children are not able to transfer to the next highest schooling grade and need to repeat the class or even have to switch to a less demanding school form. Consequently, even with very high aspirations and potentially other means to aid the transition to the desired track, parents know that the child’s performance is still an important requirement for educational success. They have various options to influence performance, especially using tutoring and offering additional learning resources to their children (Beal et al., 2007; Hof and Wolter, 2014). Often, these means of support come with financial costs and are not available to all families. Another option is to communicate to the child how important education is for having a successful life and to motivate him or her to invest more time and effort in school, learning and homework (Gottfried et al., 1994). Apparently, this is a gradual process that can be as low as giving advice or as high as forcing the children to learn and punish them if they fail to do so. Of course, given the constraints of intellect and cognitive performance, motivating or even punishing children can only do so much as there are other limits that are beyond the influence of parents. In conclusion, one can expect: the higher the educational aspirations of the parents, the higher the academic performance of their children (Hypothesis 1).

To continue with the role of performance, it is obvious that effects in the inverted direction are also possible. As outlined before, parents usually adjust their aspirations on the basis of the information they receive about their child (Bayesian updating). Clearly, as performance is one of the most relevant predictors of future educational success, it makes sense to assume that it will affect the formation of aspirations as well. For example, assuming that parents hold low aspirations at the start of primary education, noticing that their child is well-performing and mastering the requirements easily might be important information to readjust aspirations. When academic success appears to be in reach, there are good arguments to choose a more demanding schooling track as it offers higher educational qualifications and opens up more educational pathways. While this is not necessarily the case for all parents, one can expect, on average, that performance influences aspirations positively (Hypothesis 2).

However, this expectation comes with some limitations which are derived from the theories previously discussed. Parents of socially benefited families usually always hold high aspirations and need their children to reach high education, so they are able to reproduce the parental status (status maintenance hypothesis). It is unlikely that these parents will easily readjust their aspirations, even if they notice that their child struggles to reach average performance in class. The motive to acquire a high academic education is simply too strong to abandon this initial goal. Parents from socially disadvantaged families will probably react differently as they do not have these strong incentives to start with. An additional argument for socially stratified effects stems from parental support. Socially benefited families have much more resources available they can invest in their children, due to additional financial or social support. This is not the case for socially weaker parents. They know that when their child fails in school there is little they can do to help the situation as tutoring or extra assistance are not affordable. This means they have to rely much more on the actual performance the child delivers right now and be careful to not overstretch their aspirations. If it becomes clear that the child struggles in school, it is not wise for them to keep high aspirations as this could mean additional (sunken) costs. Therefore, one would expect socially stratified effects: parents of socially disadvantaged families will readjust their aspirations more easily than parents of socially benefited families (Karlson, 2019; Forster, 2021). In other words, socially disadvantaged families pay more attention to the academic performance of their children when adjusting aspirations while socially benefited families always keep up high aspirations, regardless of the academic performance of their child (Hypothesis 3).

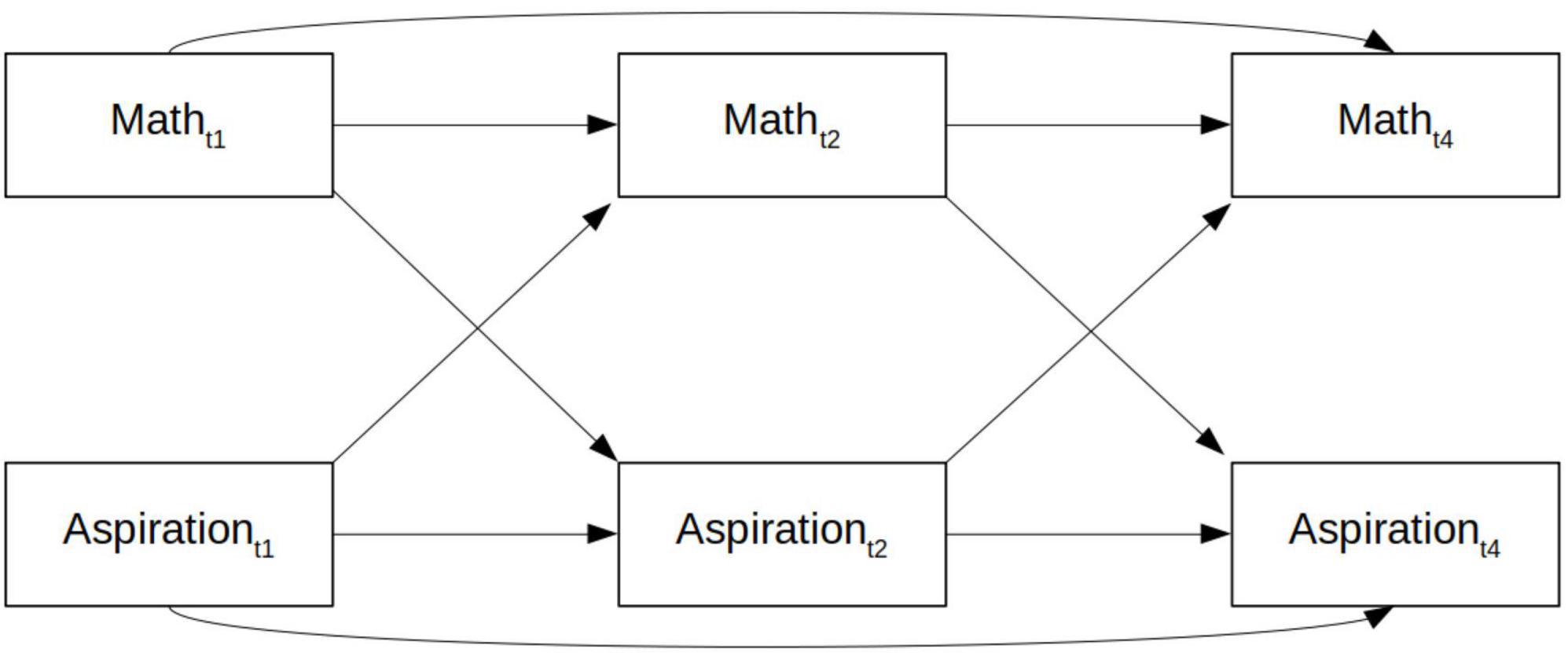

To give an overview, a figure is presented that summarizes the (causal) pathways over the course of primary education (Figure 1). As there are three school grades included in the following analyses, only these points in time are shown. As becomes clear, performance and aspirations are able to influence each other but only in the subsequent wave to account for the temporal order of the events. Additionally, delayed effects are potentially allowed, meaning that variables can directly influence previous waves which are not necessarily mediated by waves in between. The reason for including these are discussed in more detail when the model selection is outlined further below.

Figure 1. Theoretical model. Source: own design. No measurements are available for t3, which is hence omitted.

To summarize, the following analyses will give new research insights that go beyond what has been done before. Most importantly, this is the first large-scale (N > 4,000, 360 schools) analysis that includes actual performance, measured by high-quality achievement tests that are independent of parental, filial or teacher assessment, thus greatly reducing any related measurement errors. It gives insight into the development of aspirations, which is rather unique. Furthermore, a large number of relevant control variables is available to account for spurious correlations and avoid biased estimations. As explained in more detail below, the total causal effect is estimated, not separating between and within influences. Finally, as this study comes from a more sociological perspective, the socially stratified nature of the effects is of special relevance. The overall aim is to explain how early educational inequality forms, which might be relevant for policy and interventions.

Previous research findings

First, selected studies are presented that investigate one-directional effects, so either effects of aspirations on performance or vice-versa. Afterward, research findings are presented that especially focus on the co-development between achievement and aspirations (or related aspects). To start with the influence of aspirations on achievement, there are quite some studies from varying cultures and contexts that show that positive influences exist. While some reports only present correlations (Cherian, 1994; Rothon et al., 2011; Ahuja, 2016), others attempt to isolate the effects by introducing control variables (Abu-Hilal, 2000; Marjoribanks, 2005; Carroll et al., 2009; Ansong et al., 2019). The overall picture is that high aspirations are associated with better performance, on average. Interestingly, parental aspirations even have a statistically significant positive influence on grades in German secondary education under control of academic performance (measured by test-scores) and other potential confounders (Bittmann and Mantwill, 2020). Overall, the evidence underlines that aspirations of both, parents and their children, can affect the filial achievement. The external validity of the findings is probably high since there is a large variation with respect to important parameters of the studies, like country, culture, statistical method or operationalization. The conclusion is that we can expect positive effects of aspirations on achievement.

To continue with the effect that performance can have on aspirations, we also find positive evidence. Pupils with the highest academic achievement also report the highest educational aspirations (Widlund et al., 2018) and achievement can function as a filter for future aspirations (Shapka et al., 2006). This is in line with other studies that find that achievement predicts aspirations for university majors (Parker et al., 2014). Some more studies come to similar conclusions in secondary education (Christofides et al., 2015; Korhonen et al., 2016; Widlund et al., 2020). Again, the external validity is probably high since difference stages in the educational system are investigated and different measures are available. To conclude, given these empirical results it makes sense to assume that performance does indeed affect aspirations.

Finally, to come to the most relevant part, the cross dependencies of aspirations and achievement, one recent Swiss study finds suspected positive cross-lagged effects of parental aspirations and the academic self-concept of the child (Buchmann et al., 2022). Self-concept refers to a self-assessment of the child of how well it does with school and performance and is potentially a rough proxy of actual performance. While it is not exactly performance but rather how the child perceives its own achievements, this is highly relevant as it shows that parents and children are able to influence each other. As the authors utilize the RI-cross-lagged panel model (CLPM) one would expect that their findings probably display a lower bound of the effect sizes since trait-like components (the stable components) are partialed out. Further, a Romanian study investigating the interrelations between GPA and personality traits (Big Five) using both kinds of models (CLPM and RI-CLPM) to distinguish between within-person and between-person influences finds that a high GPA can have some protective effects against negative longitudinal effects, like growing neuroticism (Negru-Subtirica et al., 2020). A German study investigating the development of academic self-concept and reading achievement compares multiple statistical methods and only finds between-individual but not within-individual effects, thus questioning the reciprocity of the constructs in elementary school children (Ehm et al., 2019). However, as will be discussed in more detail below, separating between- and within-effects is often neither necessary nor useful. Lastly, a study from the United States which also looks as mediation pathways between the two constructs of interest reports that achievement and aspirations influence each other over the course of five waves, even under control of other factors such as overall cognitive ability (Guo et al., 2015). However, the parents were not surveyed and the measures were taken from pupils only. All in all, there is sufficient recent evidence available from multiple countries to conclude parents and their children influence each other over the course of multiple years and readjustment processes of named constructs are present.

Empirical research

Data, variables, and methods

In this chapter the data, sample, and variables of the empirical analyses are introduced. Afterward, the analytical model is described.

Data and sample

The following analyses are based on the German National Educational Panel Study (NEPS), Starting Cohort 2 (SC2), which initially sampled children in kindergarten (about 4 years old) in 2011 (Blossfeld and Roßbach, 2019; NEPS Network, 2020).3 The children and their families were then repeatedly interviewed (approximately once per year), which makes it possible to trace their trajectories over time (panel data). In addition to the surveys, participating children were invited to take part in competencies tests developed by the NEPS. Since this is a long-running panel, all children have transferred to secondary education and complete trajectories are available for primary schooling. Summarized, the NEPS is a powerful data source since it not only provides high quality individual panel data but also information on the family, social background, schools, and competencies in various disciplines. Of special interest for the following analyses are waves 3 to 6, which correspond to schooling grades 1 to 4 (the normal range of primary schooling in Germany). For this study, the competencies are restricted to the tests in mathematics, which were conducted in waves 3, 4, and 6. Other domains of interest, especially the reading competencies, were not used since they were measured less often. Note that math competence was not tested in wave 5 (grade 3), therefore this wave is omitted from the analyses. Initially, there were 6,734 pupils participating in grade 1. There are no sample restrictions besides removing pupils with a lot of relevant information missing (never taking part in any math test or the parents never taking part in the adult survey) and pupils who have been identified as having special educational needs. After conducting multiple imputation (for details see below), there are 4,325 cases left for analysis.

Variables and operationalization

Parental aspirations are measured using the following item: “And considering everything you know now: What qualification will [name of the child] actually finish school with?”. This item is dichotomized into higher education entrance qualification (Abitur, coded 1) or any other lower educational degree (coded 0) as this reflects the most relevant theoretical distinction (directly able to enter tertiary education or not). This item measures realistic educational aspirations - what a child can actually achieve. Idealistic aspirations (which are by design independent of prior achievement or any other economic or social restrictions) are not used since they should be, according to theory, rather independent of performance and are therefore not optimal for the analyses.

Performance is measured using the comprehensive NEPS tests which are conducted within the classroom context in grades 1, 2, and 4. To be precise, the mathematics tests are used since this competence domain has been tested the most often in the NEPS primary school sample. To give a concrete example, in grade 4, 24 questions are posed to the children, which are then scaled using a partial credit model (Schnittjer et al., 2020). The general conceptual framework is oriented at other comparable tests (like PISA) and attempts to cover various mathematical aspects like quantity, space and shape or interpretation of data to give a comprehensive view of a child’s ability. While the NEPS provides weighted maximum likelihood (WLE) estimates per default, the option is given to estimate plausible values (PVs). Although WLEs represent the individual competence level accurately, they systematically overestimate the variance in a sample and can thus be a source of bias for analyses on the population level (Lüdtke and Robitzsch, 2017; Scharl et al., 2020). Since one is interested in this kind of analysis, generating PVs appears to be relevant. In this process, the values are estimated by not only including the competence items in the models but also all other variables that are part of the following analytical models (for example, gender, migration status, or parental aspirations). This process creates multiple performance estimates for each pupil, which is then similar to the handling of imputed data. In the end, it is straightforward to combine plausible values and imputed datasets (regarding the other variables) and conduct the analyses of interest. Plausible values are computed using the R-package nepsscaling 2.0.0 (Scharl et al., 2020). For the following analyses, the performance scores are standardized by grade 1.

Finally, to account for potential spurious correlations, a large set of relevant control variables is selected for the analytical models based on previous research findings (Eckerth et al., 2014). The gender of the child is included as a binary variable, the same holds for the place of residence (East or West Germany). Parental education is measured by the highest educational qualification in the family and dichotomized. If either the father or the mother of the child have obtained the higher education eligibility (Abitur) or any tertiary degree, this variable is coded 1, 0 otherwise. According to the theory of status maintenance, this variable indicates the educational orientation of the family. Parental income is included as the total after tax monthly household income as a logged variable to ease statistical inference. The age of the child is computed in 2013 (date of reference was set to June 1) when pupils were in grade 1. The migration background is a binary variable and coded 1 for migration background if at least one parent is born abroad, 0 otherwise. The number of siblings living in the same household is included as well. Finally, it is measured whether the parents are living together (nuclear family) or not (for any reasons). If the parents report that they are living together at all times from grade 1 to 4, this is counted as a nuclear family (coded 1). If there is at least one point in time when parents are not living together, it is counted otherwise (coded 0). A final control variable is whether a child has ever been diagnosed with dyscalculia. By including these control variables, the internal validity of the findings should be strengthened as they might potentially function as confounders, meaning they influence both performance and aspirations at the same time.

Modeling strategy

As Figure 1 indicates, the analytical model is some variation of the cross-lagged panel model (CLPM). “Crossed” since the two main variables are allowed to influence each other and “lagged” since values of previous points in time are allowed to influence only following points, therefore respecting the direction of causality. Interestingly, there is a long and still ongoing debate in the literature about the specific model to use (Hamaker et al., 2015; Mulder and Hamaker, 2021; Usami, 2021). Shown in Figure 1 is a hybrid between the standard CLPM and a variation that accounts for higher-order lags, as, for example, variables at t1 are allowed to influence variables at t4, which can be thought of as delayed effects. A quite different implementation of these models is CLPM with random intercepts (RI-CLPM), which were created since the standard CLPM is apparently not able to account for trait-like and time-invariant aspects of variables. To give a concrete example, when the development of math performance over time is of interest, one could suspect that this ability can be decomposed into a constant component (the inherent math ability, the talent or capability, which should be rather stable over time, since some pupils are just better at math than others) and a variable component, that can be influenced by the quality of teaching, the time spent with homework or tutoring. As some authors argue, this RI-CLPM (which can be thought of as a form of fixed-effect models as the fixed part of a variable is accounted for) is inherently better since the CLPM only accounts for temporal stability due to the autoregressive terms in the model (the same variables from earlier points in time). Statistically speaking, this means that it is assumed that each individual varies around the same mean and no stable components exists, which is unrealistic for most variables in the social sciences. While these benefits of the RI-CLPM seem appealing, there is also critique. Quite relevant, the RI-CLPM only captures temporary fluctuations around the individual person mean and is not able to account for effects that explain differences between persons. Furthermore, the claim that this type of model is able to account for unobserved confounding is only true for very specific data constellations and is not a general property of this approach (Lüdtke and Robitzsch, 2021). In addition, the RI-CLPM is usually more appropriate for studies interested in the explanation of shorter time lags (e.g., days) and not in systematic long-term changes (Lüdtke and Robitzsch, 2021; Orth et al., 2021). Another major drawback is that the RI-CLPM is at the moment only statistically well-defined for continuous outcome variables, which is relevant for the following analyses as aspiration is a binary variable. Given all these considerations, the decision was made to utilize the hybrid CLPM using a selection of higher-order lags and including a large set of relevant control variables.4 What this means for the interpretation is discussed in more detail in section “Cross-lagged panel model.” According to simulation studies, this procedure should give valid results for posed research questions as the true data-generating process is not known. As there is no option to test which model is the least biased to estimate causal effects as relevant statistics like model fit indices are not indicative, there is no reason to believe that this modeling is inherently biased. I follow the suggestion of Lüdtke and Robitzsch (2021, 19) to focus on the panel-structure of the data and include relevant control variables (VanderWeele et al., 2020).

Practically, the following analyses will be conducted as structural equation modeling (SEM). While SEM is not the most prominent statistical approach in sociology, it is highly similar to well-established methods (like regressions) and of great relevance for the current research questions. The main advantage of SEM is that it is feasible to test elaborate models in a single step where variables can be both dependent and independent. As Figure 1 shows, this is exactly what is proposed theoretically. To be clear, SEM is by no means magical or superior to other methods. Aspects like causality are the same in comparison to other models and not the choice of statistical approach but theoretical reasoning and the inclusion of relevant control variables can help to recover causal effects. To be precise, the following model will be a path analysis (since there are no latent constructs included due to the restrictions of the data). In the end, the interest lies in two distinct results: first, the path coefficients, which are interpreted as OLS regression coefficients, and the overall fit of the model, which makes it possible to state whether the data fit the theoretical model or not. If this fit is not satisfying, it might be necessary to reject the theoretical assumptions altogether and create a new analytical framework. The path coefficients are highly relevant to make statements about specific relations within the model and assess the size of the effects. Note that this statistical modeling also applies to the binary outcome variable (parental aspirations). In the past, researchers have often preferred logistic models for these outcome variables, however, there are also good arguments to use OLS for binary outcomes (linear probability model, LPM) (Angrist and Pischke, 2009, 47; Wooldridge, 2010, 579ff.). By doing so, complications due to rescaling effects in the cross-dependency models are avoided to ease interpretation and comparability between the two outcomes, which is the most relevant argument for using a LPM at this point. I do not expect a bias due to this modeling strategy since the shares of high aspirations are usually well below 90% and the linear model is a good approximation in these not extreme regions (see Table 1).

All computations are done in Stata 16.1, except for the estimation of plausible values, which are generated using R. To account for item non-response, data are imputed with multiple imputation with chained equations (MICE), creating a total of 50 complete datasets (Azur et al., 2011). Some additional auxiliary variables are included to improve the quality of the imputation (for example, idealistic aspirations or the gender of the parent answering the survey). The imputation model is set to draw from the specified predicted posterior distributions which depend on the scaling of the variables (e.g., binary or continuous). Various quality measures of the imputations were tested (distribution of generated values, no impossible values, convergence) and approved. To account for the fact that the competence tests are conducted within schools and not at home, which creates a form of nested data, standard errors are clustered by schools.

Results

This chapter provides all descriptive and analytical findings and concludes with a final verdict on the proposed hypotheses.

Descriptive overview

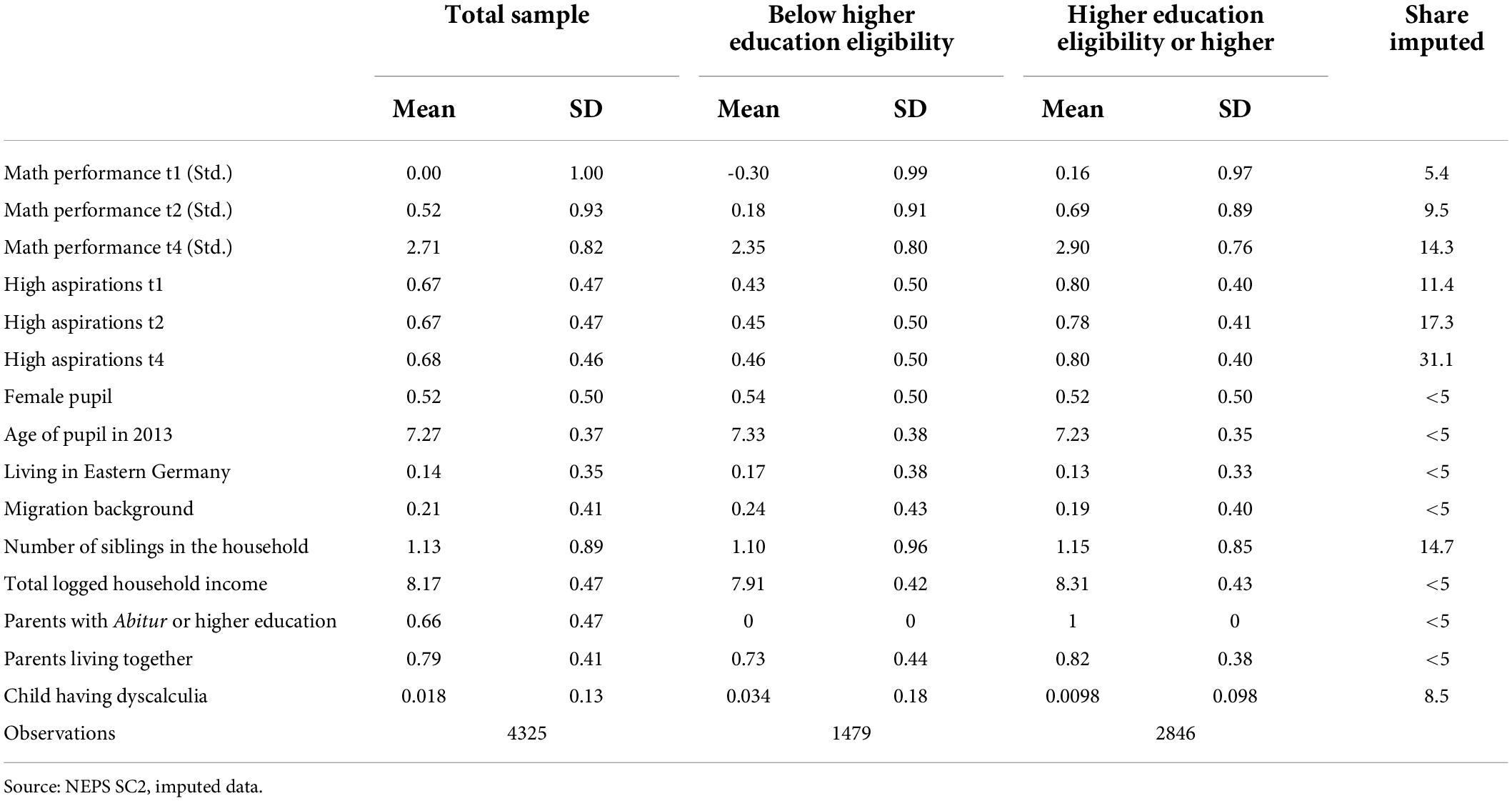

Before conducting the main analyses, a descriptive overview is helpful to get an impression of the data. The results are summarized in Table 1. In addition, the descriptive statistics are grouped by educational level (parents with at least higher education eligibility vs. other parents) as stratification is of special interest for the advanced analyses.

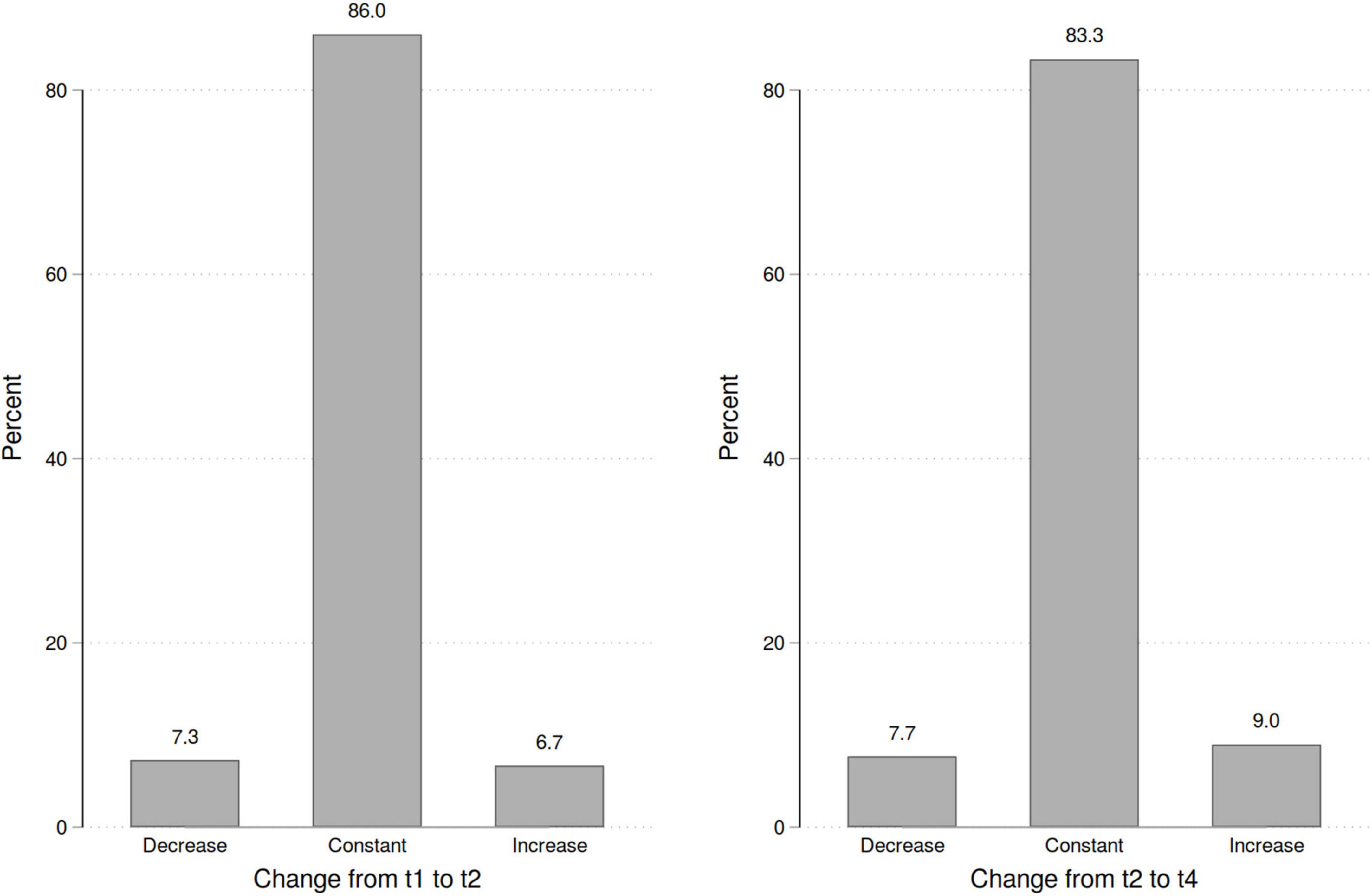

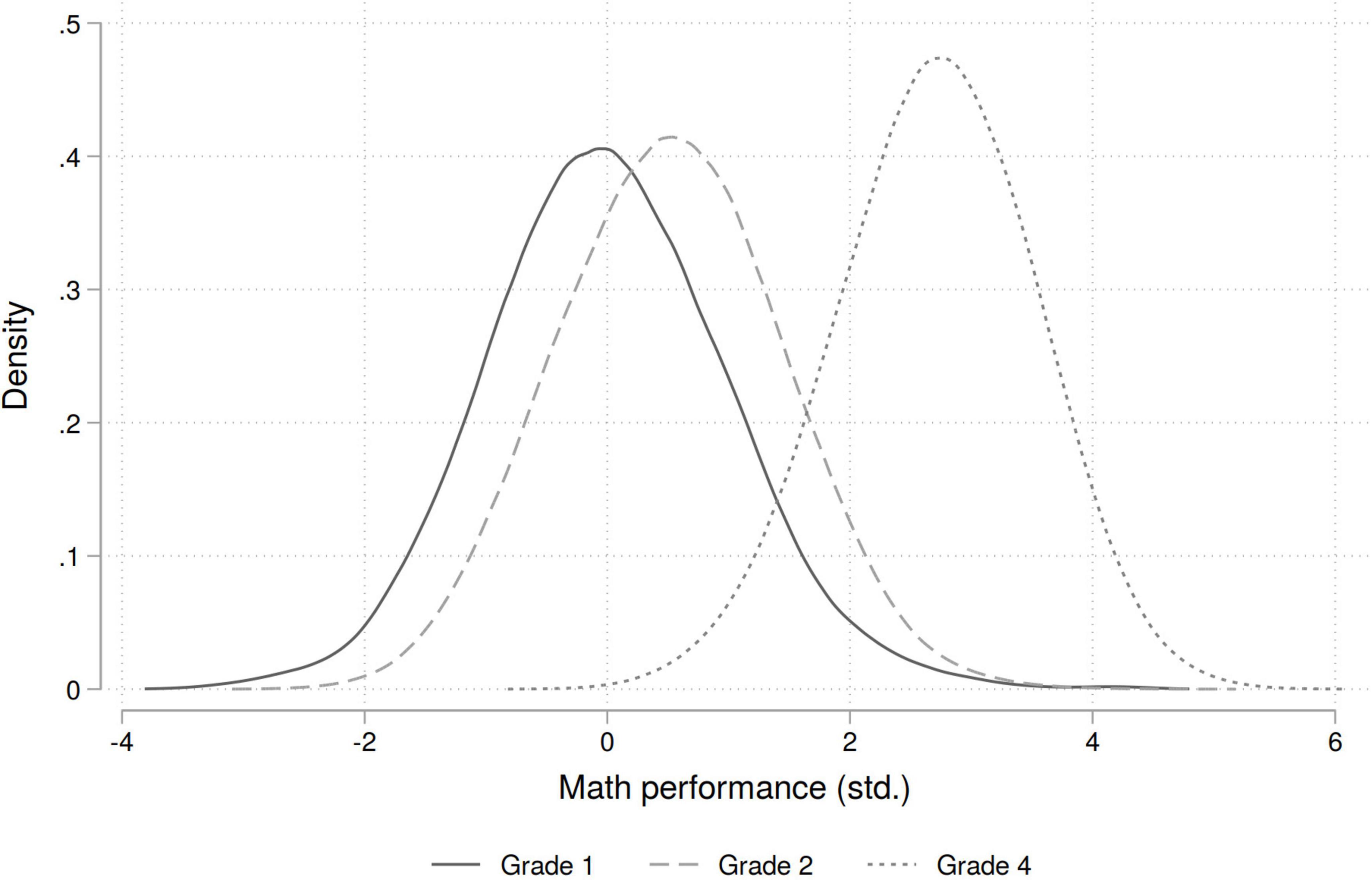

It becomes clear that overall math performance increases over time. In grade 1, the mean is 0 since it is z-standardized, the following points in time can be interpreted as deviations from this mean. Figure 2 also indicates that these measures are approximately normally distributed. The aspirations are quite constant over time, at least when the aggregated measures are inspected. However, there is also enough within-subject variation present in the data to be exploited for the analyses (standard deviation of aspirations is about 0.24). Another way to visualize this is to plot how many parents actually change their aspirations over time, which is done graphically in Figure 3. Apparently, the large majority of parents will hold their aspirations constant while some changes are present. The share slightly increases over the course of primary education. In grade 1, the average pupil was about 7.3 years old. About 66% of all pupils had parents who obtained higher education eligibility or a tertiary degree, which indicates that the NEPS sample is rather highly educated.

Figure 2. Distribution of math competencies by grade. Source: NEPS SC2, imputed data. Competencies are standardized by grade 1.

When focusing on the effect of parental education as a stratifying variable, it becomes clear that group differences are present. More highly educated parents have a higher probability to hold high educational aspirations and their children perform better in the achievement tests. Also, they are less likely to have a migration background and their income is higher, on average. These results make sense and show that parental education indicates social origin.

Cross-lagged panel model

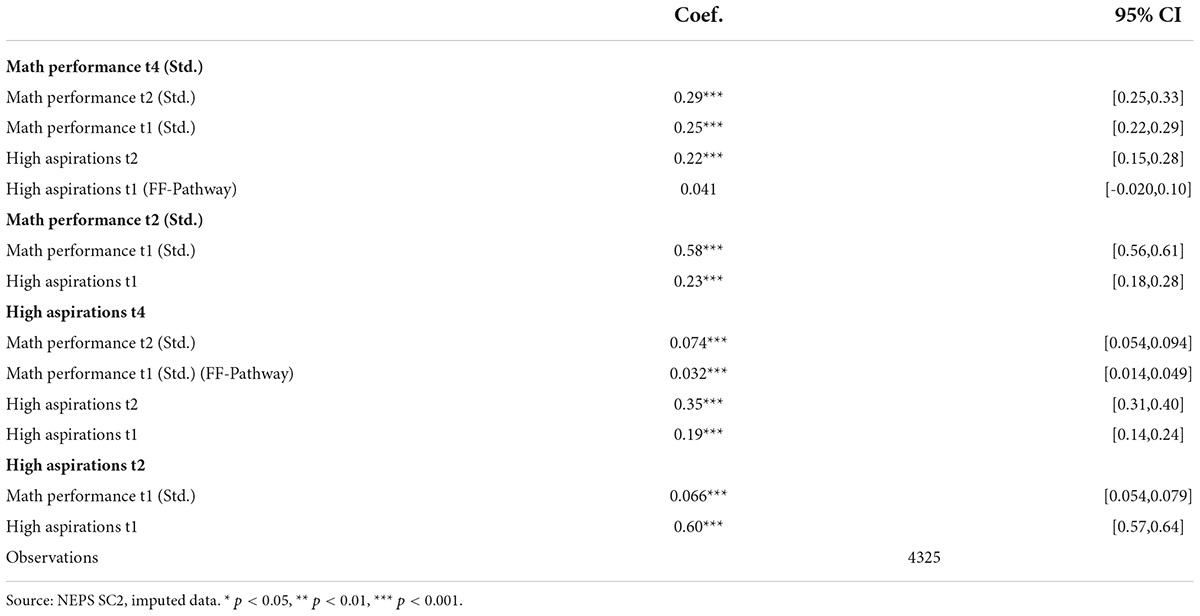

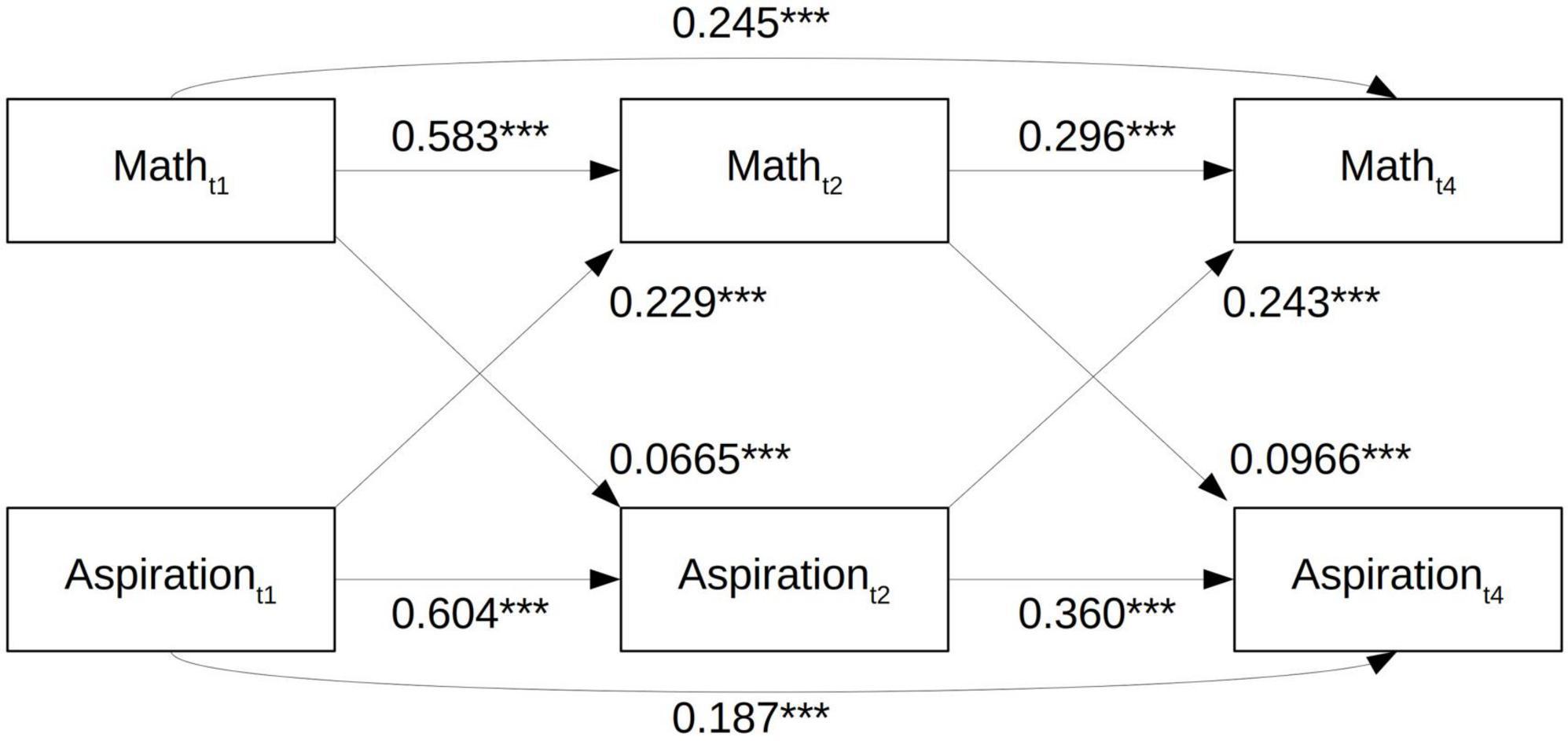

Next, the main model follows, the CLPM, which implements the theoretical model of Figure 1. The results are shown in Figure 4 for a convenient interpretation; numerical results are reported in the Appendix Table A1. Since most variables can be both dependent and independent, results are depicted separately by the dependent variable. Note that, strictly speaking, all variables in this model are endogenous (even performance and aspirations in t1) since control variables are included. Visually, this means that an arrow points from the vector of all control variables to each variable in Figure 1 (not shown for a clearer depiction). The error terms between performance and aspirations are allowed to be correlated within each point in time. Reported are 95% confidence intervals in brackets.

Figure 4. Path coefficients for the CLPMSource: NEPS SC2, imputed data. Control variables: gender, age, income, parental education, migration status, number of siblings, place of residence, single parents, dyscalculia. Standard errors clustered by school. *** p < 0.001.

Before continuing with the empirical results, the correct interpretation of the model should be explained, which is also referring back to “Modeling strategy” where differences between the CLPM and the RI-CLPM are outlined. Exemplary, the cross-lagged effect of the CLPM as specified above answers the question whether parents having high aspirations (compared to other parents) at time point t have their child showing higher achievement (compared to other children) at time point t + 1 (Lüdtke and Robitzsch, 2021, 13).5

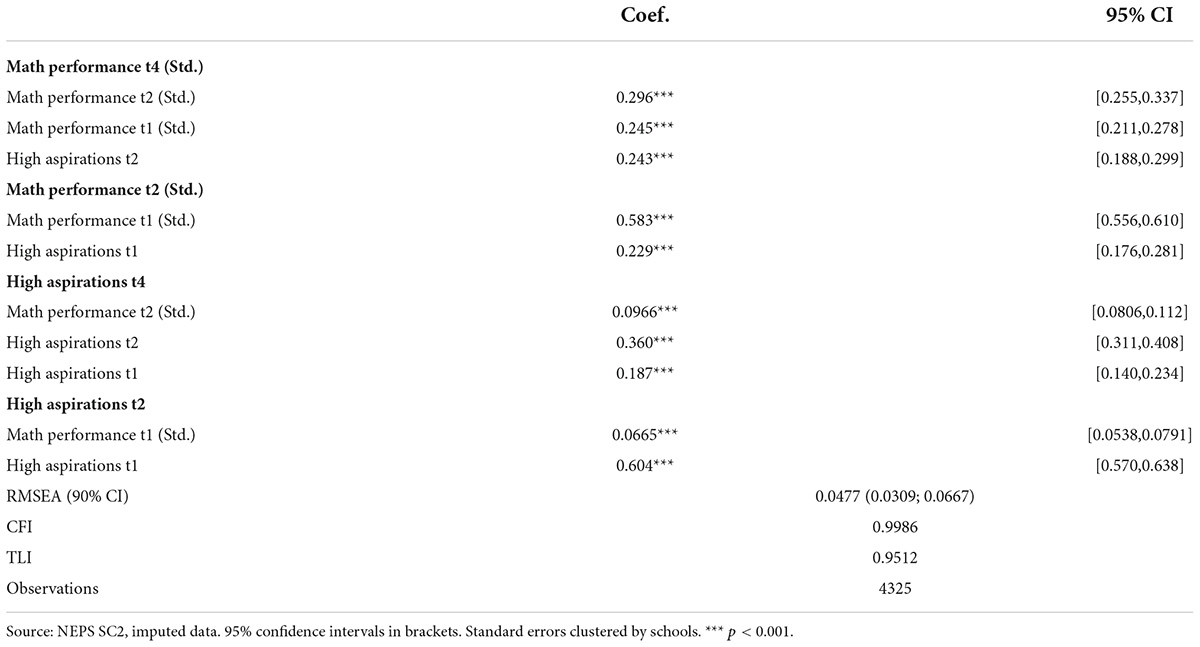

First, the overall model fit is reported to gauge whether the data are congruent with the proposed theoretical model. The probably most relevant statistic is the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA). The central idea of this statistic is to compare the observed variance-covariance matrix with the proposed one (the model). If this statistic is large, it means that the proposed model shows larger deviations from the data. In the literature, a RMSEA below 0.05 is considered as very good and between 0.05 and 0.08 as good (Gana and Broc, 2019, 43). This statistic is 0.048, indicating that the model is fine. The question might arise why all potential effects are then not simply added to the statistical model, which makes the model identical to the data and lowers the RMSEA to 0. However, such a saturated model is usually not of theoretical interest as it simply states that everything is related to everything else. That is why other indices are reported which also take the degree of parsimony into account. The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) should be larger than 0.90 for a good model fit and larger than 0.95 for a very good fit. These values are 0.999 and 0.951, indicating a good overall fit. The conclusion is that the proposed theoretical model is quite congruent with the observed data and that the theoretical assumptions are therefore grounded in reality. After the overall model fit the path coefficients are of special interest.

Starting with performance, we notice that achievement always significantly predicts the achievement in the subsequent wave of the survey, which makes sense. Additionally, there is a highly significant effect of performance in grade 1 on performance in grade 4, even under the control of performance in t2. Interpreting this finding is interesting: potentially, this is a delayed effect. One could also consider this to be the influence of the time-constant trait or “talent” with respect to mathematical ability. This would also explain why the effect of math t2 on t4 is smaller since this is then to be viewed as a compound effect (the stable effect and the variable effect due to additional gains from t2 to t4). For aspirations, these effects are conceptually similar. Since these numbers are the result of linear probability models, one can interpret them as average marginal effects. For example, parents who hold high aspirations in t1 have a 60.4 percentage point larger probability to hold high aspirations in t2 than parents without high aspirations in t1. To continue, the crossed effects are of special interest. For t2, which can only be influenced by t1, we see that children of parents who hold high aspirations have, on average, a performance that lies 0.23 standard deviations above children of parents who do not hold these aspirations. Since this result is under control, so to speak, of math performance in t1, one can interpret this effect as an actual change from the baseline that is due to the higher aspirations. A quite similar finding holds for the effect of aspirations in t2 on performance in t4. Regarding the effects of performance on aspirations, we also see positive and statistically significant results. The interpretation is that with each standard deviation more of performance, the probability to hold high aspirations in t2 increases by about 7 percentage points. For the following point in time, this effect even increases to almost 10 percentage points.

As hypothesis 1 states that higher aspirations predict higher performance, one can accept this hypothesis as the relevant coefficients are positive and statistically highly significant. Hypothesis 2 is that there is a positive effect of performance on aspirations. As the coefficients clearly show, this is indeed true. Since this is the case for both grade 2 and 4, hypothesis 2 is accepted.

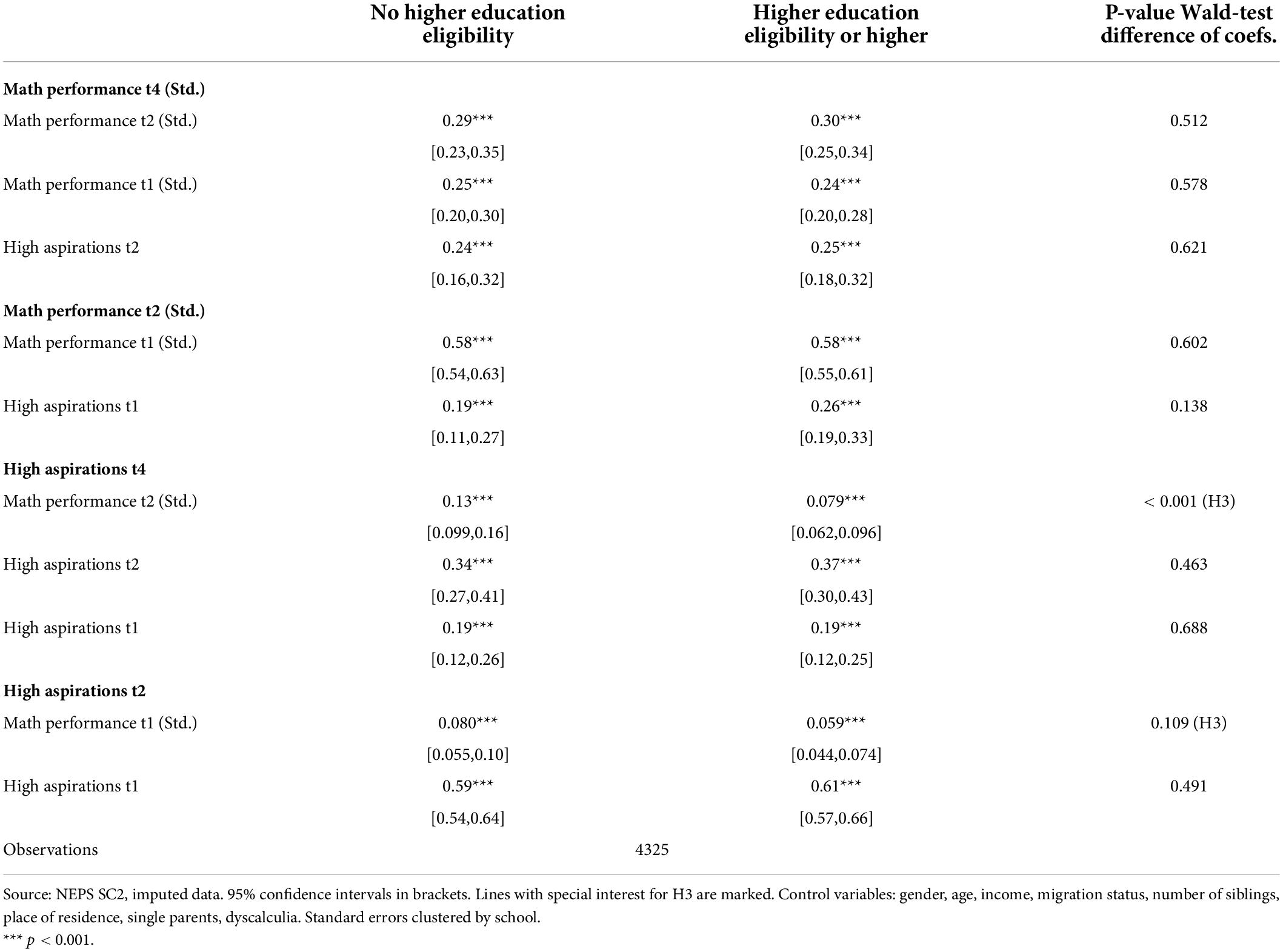

Socially stratified effects

As explained before, one could expect that the path coefficients in the above model are not identical for lowly and highly educated parents. This can be tested empirically using Wald tests or whether parameters constrained to be equal across groups should be relaxed. One can think of this as having an interaction term between each coefficient and parental education. Since the education of the parents is the variable to stratify on, it is no longer included in the set of control variables. The rest of the model is identical. Results are displayed in Table 2. For easier identification, the relevant lines in the table are marked with “H3”. To test the difference between the coefficients, either the confidence bands or the p-values (corresponding to the Wald tests) can be used. Regarding performance, it is clear that the effects of aspirations are quite similar and no statistically significant differences are present. However, when aspirations are the dependent variable, other effects are visible. For aspirations in t2, the effect of performance is a bit higher for parents with less education, yet not statistically significant as the difference is only about 2 percentage points. This changes for aspirations in t4, the effect of performance is 0.13 for the lowly educated but only 0.079 for the highly educated. The p-value and confidence bands clearly indicate that this is a statistically significant difference. The conclusion is that less educated parents react more strongly to high performance than highly educated ones. Therefore, hypothesis 3 is accepted.

Robustness checks

Various robustness checks are conducted to test the stability and validity of the findings. This concerns mostly the statistical modeling and testing whether the same conclusions hold for various subpopulations. The first aspect to test whether the findings are similar for boys and girls. It is known that boys usually show slightly larger math achievement than girls, while these effects are especially pronounced in older pupils (Mullis et al., 2012). As a test, the basic model is computed separately for boys and girls. The findings are summarized in the Appendix Table A2. The conclusion is that the coefficients are highly similar and there are practically no gender differences visible. The second test is whether the results are similar for natives and migrants. It is a well-established finding that the role of aspirations differs between these two groups as migrants usually have a higher chance than natives to come from a disadvantaged social origin and have less resources available (Kao and Tienda, 1995; Becker, 2010; Relikowski et al., 2012). Yet, parents often have high aspirations, which is normally not the case for socially disadvantaged natives. This opens up the question whether all findings also hold for the migrant sub-sample. The results are shown in the Appendix Table A2. The results are highly similar, with a single exception: the coefficient of high aspirations on math performance in grade 2 is lower for migrants than for natives (0.15 vs. 0.25). However, the coefficient for migrants is still statistically significant. The difference is slightly smaller in the subsequent wave (0.18 vs. 0.27), meaning that natives and migrants apparently converge on these estimates over time. As the confidences bands clearly overlap it is probably not the case that very different conclusions should be drawn for migrants and natives. Follow-up studies might want to investigate the role of migration in more detail, which then opens up quite different and novel research questions.

As another side note, using a different cut-off point for high parental education (either having obtained any tertiary degree or not) does not lead to different conclusions as the effects even become slightly more pronounced in the stratified model.

Additionally, the FF-CLPM is tested, which means that crossed pathways between t1 and t4 are introduced to the basic model. The findings are reported in Table A3. Apparently, these additional crossed effects are much smaller, which makes sense since the intermediate wave takes most of the effects. The delayed effect of achievement on aspirations is higher than for aspirations on achievement. The conclusions drawn from these two models are highly similar. Since the CLPM as used before is more parsimonious, it is the preferred one.

Finally, it must be made transparent that parental aspirations are in the vast majority the motherly aspirations since in the NEPS SC2 parent survey, only one parent was surveyed. For example, in grade 1, more than 90% of all parental respondents were female (the biological mother or a female legal custodian). Additional tests show that the gender of the responding parent is not associated with the level of aspirations in conditional models (under control of the other variables). Also, I did not find any relevant differences between models when testing the education of either the mother or the father and not the highest of both values. This means that the results are robust with respect to parental education. Potentially, the high level of homogamy with respect to education in couples as well as the transmission of aspirations between both parents can explain why no differentials are found here.

Discussion

As the results clearly indicate, parental aspirations and filial math achievement do co-develop over the course of primary education. Children of parents holding high aspirations show higher test scores in the following survey wave. Conversely, parents of children who perform better in the tests have a higher probability to report high aspirations in the subsequent wave. These results are in line with theoretical expectations and earlier publications and underline that a dynamic feedback process is going on. Based on this evidence, one can conclude that the emergence of social inequality, which usually becomes first visible when the decision for the secondary schooling track has to be made (after the end of grade 4), is not a single event but a long-lasting process that goes on for years. While most analyses are only able to shed light on this specific event due to the lack of longitudinal data, the present study elucidates what is happening years before the actual decision. What does this mean for future research and policy? It should be highlighted that all numbers are computed under the control of a large set of potentially confounding variables, and that these spurious influences are hence attenuated. Since both the financial situation of the family (measured by the household income) and the overall educational orientation (measured by the parental level of education) are held constant, it is fascinating that aspirations are still of greatest relevance. The conclusion is that these aspirations are partially independent of these other two factors that are usually the most relevant predictors of social inequality. While this cannot be proven with the available observational data, one can suspect that increasing parental aspirations might have positive effects on the performance of the children. Given the findings, it seems important to pursue this question further and test in more detail whether programs or interventions that specifically target parental aspirations show to affect grades and academic achievement.

When considering the effects of achievement in more detail, the results underline that parents of high-achieving pupils hold higher aspirations. This makes sense as these pupils have a higher probability to enter the academic track and fulfill the high academic expectations. As parents are usually well aware of the performance of their children due to grades and feedback from the teachers, they have good evidence to adapt their aspirations. The socially stratified findings are here of greatest interest. As shown clearly, especially parents with lower educational qualifications pay much attention to the performance of their children. In other words, they are quite sensitive to achievement, their aspirations depend much more on them as it is the case for highly educated parents. This finding, which is in line with theoretical assumptions and previous research results (Karlson, 2019), highlights how social inequality slowly emerges in primary education over the course of multiple years. Since parents with lower educational qualifications have a lower probability to hold high aspirations than more educated ones, even when the performances are equal, this means that the probability is high that their children will not obtain higher educational qualifications as well. Referring back to potential interventions, this means that especially families with lower educational qualifications need to be targeted as the other families will usually always hold high aspirations, which depend much less on actual performance.

To conclude, the limitations of the current study must be made transparent. First, the CLPM as used in the analyses compute a total effect, so within- and between-effects are taken together. This affects the interpretation of the findings as not pure changes are investigated. To be clear, it would be incorrect to state that an increase of aspirations influences achievement in a certain way as this would only concern intra-individual (within) variation. That being said and what is also known from previous studies, if one were to compute models that specifically take person-constant parts out of the estimation (RI-CLPM), the estimated coefficients would be smaller. Therefore, the findings presented here are probably upper bounds of effect sizes. Second, the data is observational, so it is not feasible to recover pure causal effects. Given the large set of relevant controls, one can assume that there are probably no strong confounders left but this is a theoretical question that cannot be proven statistically. Third, as some researcher points out, all panel models attempting to establish a causal order rely on the assumption that the lags are correctly specified (Vaisey and Miles, 2017; Leszczensky and Wolbring, 2022). This is highly problematic and there are currently no comprehensive statistical solutions available. As the researchers point out, in a worst-case scenario, coefficients could even switch signs. Given the current state of research one can only refer to previous findings and theory, which are both in line with the results of the present study. Given limitations due to statistical knowledge and data, there is currently no option available to guarantee that the findings are absolutely robust. However, given that dozens of previous studies as outlined in the review of the literature above come to similar conclusions (also given the high degree of variation with respect to research designs and statistical techniques), it is unlikely that they all suffer from an unfortunate lag-constellation and the entire research field comes to the same wrong conclusion. Fourth, presented are results for math achievement. It is obvious that the NEPS-tests are only one of the potentially many ways to define, measure, and operationalize achievement. Other tests might come to different conclusions as “achievement” or “performance” are (latent) constructs. Also, only mathematics was investigated in this study and this is, of course, only one part of the complete picture. Follow-up studies might want to examine the relation with other measures of performance, especially reading as this is another, highly relevant indicator of performance and development.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: http://dx.doi.org/10.5157/NEPS:SC2:9.0.0.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

The publication of this article was funded by the Open Access Fund of the Leibniz Association.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful for the various sources of support the author received. Yossi Shavit gave the inspiration for the study and advice on the cross-dependency of the variables of interest. Timo Gnambs, Anna Scharl, and Jeroen Mulder answered various questions regarding the computation of plausible values and selection of the analytical model. Lana Blazevic and Evelyn Kopp supported the review of the literature. The author would like to thank all participants of the BAGSS Weekly Seminar for their comprehensive comments on the first draft. Finally, two reviewers gave helpful remarks.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

- ^ Ultimately, it is the parents who select a school and enroll their child.

- ^ While the idealistic aspirations can function as predictors of achievement and latter realistic aspirations, they should not be itself depend on the subsequent values of these two variables and are therefore not part of the derived dynamic model.

- ^ This paper uses data from the National Educational Panel Study (NEPS): Starting Cohort Kindergarten, 10.5157/NEPS:SC2:9.0.0. From 2008 to 2013, NEPS data was collected as part of the Framework Program for the Promotion of Empirical Educational Research funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). As of 2014, NEPS has been carried out by the Leibniz Institute for Educational Trajectories (LIfBi) at the University of Bamberg in cooperation with a nationwide network.

- ^ Note that this is not a complete full-forward (FF) model since there is no cross-lagged effect between t1 and t4 specified. As some authors argue, there are often no robust theoretical reasons for the presence of these delayed crossed effects (Ehm et al., 2019, 8). The same holds for the introduced theoretical framework, which gives little reason to believe that these delayed crossed effects should appear. For example, why should aspirations in grade 1 affect the achievement in grade 4 independently of what happens in grade 2 as for the child the most recent parental behavior is probably decisive. However, the FF-CLPM is tested as a robustness check further below.

- ^ In contrast, the RI-CLPM would tell: do parents who have higher deviations from their long-term average aspirations at time point t have a child that is likely to show a higher deviation from his or her long term average achievement score at time point t + 1? This answers a quite different research question.

References

Abu-Hilal, M. M. (2000). A structural model of attitudes towards school subjects, academic aspiration and achievement. Educ. Psychol. 20, 75–84. doi: 10.1080/014434100110399

Ahuja, A. (2016). A study of self-efficacy among secondary school students in relation to educational aspiration and academic achievement. Educat. Quest 7, 275–283. doi: 10.5958/2230-7311.2016.00048.9

Andrew, M., and Hauser, R. M. (2011). Adoption? Adaptation? Evaluating the formation of educational expectations. Social. Forces 90, 497–520.

Angrist, J. D., and Pischke, J.-S. (2009). Mostly harmless econometrics: an empiricist’s companion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Ansong, D., Eisensmith, S. R., Okumu, M., and Chowa, G. A. (2019). The importance of self-efficacy and educational aspirations for academic achievement in resource-limited countries: Evidence from Ghana. J. Adolesc. 70, 13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.11.003

Azur, M. J., Stuart, E. A., Frangakis, C., and Leaf, P. J. (2011). Multiple imputation by chained equations: what is it and how does it work?: Multiple imputation by chained equations. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 20, 40–49. doi: 10.1002/mpr.329

Beal, C. R., Walles, R., Arroyo, I., and Woolf, B. P. (2007). On-line tutoring for math achievement testing: A controlled evaluation. J. Interact. Online Learn. 6, 43–55.

Becker, B. (2010). Bildungsaspirationen von Migranten: Determinanten und Umsetzung in Bildungsergebnisse. Available Online at: http://edoc.vifapol.de/opus/volltexte/2011/3423/pdf/wp_137.pdf (accessed July 14, 2022).

Bittmann, F. (2021). Academic track mismatch and the temporal development of well-being and competences in German secondary education. Vienna Yearb. Popul. Res. 19, 1–36. doi: 10.1553/populationyearbook2021.res5.1

Bittmann, F. (2022). Investigating the role of educational aspirations as central mediators of secondary school track choice in Germany. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 81:100715. doi: 10.1016/j.rssm.2022.100715

Bittmann, F., and Mantwill, O. (2020). Gute Leistung, gute Noten? Eine Untersuchung über den Zusammenhang von Schulnoten und Kompetenzen in der Sekundarstufe (Good Performance, Good Grades? An Analysis of the Relationship Between Grades and Competences in German Secondary Education). SSRN J. 25. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3724172

Blossfeld, H.-P., and Roßbach, H.-G. (2019). Education as a Lifelong process: The German national educational panel study. New York, NY: Springer.

Boudon, R. (1974). Education, opportunity, and social inequality: Changing prospects in western society. New York, NY: Wiley-Interscience.

Breen, R., and Goldthorpe, J. H. (1997). Explaining educational differentials: Towards a formal rational action theory. Rational. Soc. 9, 275–305. doi: 10.1177/104346397009003002

Breen, R., and Yaish, M. (2006). “Testing the Breen-Goldthorpe model of educational decision making,” in Mobility and inequality: Frontiers of research in economics and sociology, eds S. L. Morgan, D. B. Grusky, and G. S. Field (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press), 232–258.

Buchholz, S., Skopek, J., Zielonka, M., Ditton, H., Wohlkinger, F., and Schier, A. (2016). “Secondary school differentiation and inequality of educational opportunity in Germany,” in Models of secondary education and social inequality, eds H.-P. Blossfeld, S. Buchholz, J. Skopek, and M. Triventi (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing), 79–92. doi: 10.4337/9781785367267.00014

Buchmann, M., Grütter, J., and Zuffianò, A. (2022). Parental educational aspirations and children’s academic self-concept: Disentangling state and trait components on their dynamic interplay. Child Dev. 93, 7–24. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13645

Carolan, B. V. (2017). Assessing the adaptation of adolescents’ educational expectations: Variations by gender. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 20, 237–257.

Carroll, A., Houghton, S., Wood, R., Unsworth, K., Hattie, J., Gordon, L., et al. (2009). Self-efficacy and academic achievement in Australian high school students: The mediating effects of academic aspirations and delinquency. J. Adolesc. 32, 797–817. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2008.10.009

Cherian, V. I. (1994). Relationship between parental aspiration and academic achievement of Xhosa children from broken and intact families. Psychol. Rep. 74, 835–840. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1994.74.3.835

Christofides, L. N., Hoy, M., Milla, J., and Stengos, T. (2015). Grades, aspirations, and postsecondary education outcomes. CJHE 45, 48–82. doi: 10.47678/cjhe.v45i1.184203

Eckerth, M., Hanke, P., and Hein, A. K. (2014). “Entwicklung von Kindern im mathematischen Bereich im Übergang von der Kindertageseinrichtung in die Grundschule – Ergebnisse aus dem FiS-Projekt,” in Individuelle Förderung und Lernen in der Gemeinschaft, eds B. Kopp, S. Martschinke, M. Munser-Kiefer, M. Haider, E.-M. Kirschhock, G. Ranger, et al. (Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden), 262–265. doi: 10.1007/978-3-658-04479-4_49

Eckhardt, T. (2017). The Education System in the Federal Republic of Germany 2015/2016. A description of the responsibilities, structures and developments in education policy for the exchange of information in Europe. Available online at: https://www.kmk.org/fileadmin/Dateien/pdf/Eurydice/Bildungswesen-engl-pdfs/dossier_en_ebook.pdf (accessed July 14, 2022).

Ehm, J.-H., Hasselhorn, M., and Schmiedek, F. (2019). Analyzing the developmental relation of academic self-concept and achievement in elementary school children: Alternative models point to different results. Dev. Psychol. 55, 2336–2351. doi: 10.1037/dev0000796

Forster, A. G. (2021). Caught by surprise: The adaptation of parental expectations after unexpected ability track placement. Res. Soc. Stratif. Mobil. 76:100630. doi: 10.1016/j.rssm.2021.100630

Gölz, N., and Wohlkinger, F. (2019). Determinants of students’ idealistic and realistic educational aspirations in elementary school. Z. Erziehungswiss. 22, 1397–1431. doi: 10.1007/s11618-019-00916-x

Gottfried, A. E., Fleming, J. S., and Gottfried, A. W. (1994). Role of parental motivational practices in children’s academic intrinsic motivation and achievement. J. Educ. Psychol. 86, 104–113. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.86.1.104

Guo, J., Marsh, H. W., Morin, A. J. S., Parker, P. D., and Kaur, G. (2015). Directionality of the associations of high school expectancy-value, aspirations, and attainment: A longitudinal study. Am. Educ. Res. J. 52, 371–402. doi: 10.3102/0002831214565786

Hamaker, E. L., Kuiper, R. M., and Grasman, R. P. P. P. (2015). A critique of the cross-lagged panel model. Psychol. Methods 20, 102–116. doi: 10.1037/a0038889

Hof, S., and Wolter, S. (2014). Ausmass und Wirkung bezahlter Nachhilfe in der Schweiz. Aarau: SKBF.

Kao, G., and Tienda, M. (1995). Optimism and achievement: The educational performance of immigrant youth. Soc. Sci. Q. 76, 1–19. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1423-5

Karlson, K. B. (2015). Expectations on track? High school tracking and adolescent educational expectations. Soc. Forces 94, 115–141. doi: 10.1093/sf/sov006

Karlson, K. B. (2019). Expectation formation for all? Group differences in student response to signals about academic performance. Sociol. Q. 60, 716–737. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2021-068576

Korhonen, J., Tapola, A., Linnanmäki, K., and Aunio, P. (2016). Gendered pathways to educational aspirations: The role of academic self-concept, school burnout, achievement and interest in mathematics and reading. Learn. Instr. 46, 21–33. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.08.006

Leszczensky, L., and Wolbring, T. (2022). How to Deal With Reverse Causality Using Panel Data? Recommendations for Researchers Based on a Simulation Study. Sociol. Methods Res. 51, 837–865. doi: 10.1177/0049124119882473

Lüdtke, O., and Robitzsch, A. (2017). Eine Einführung in die Plausible-Values-Technik für die psychologische Forschung. Diagnostica 63, 193–205. doi: 10.1026/0012-1924/a000175

Lüdtke, O., and Robitzsch, A. (2021). A critique of the random intercept cross-lagged panel model. PsyArXiv [Preprint]. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/6f85c

Marjoribanks, K. (2005). Family background, academic achievement, and educational aspirations as predictors of Australian young adults’ educational attainment. Psychol. Rep. 96, 751–754. doi: 10.2466/pr0.96.3.751-754

Morgan, S. L. (2005). On the edge of commitment: Educational attainment and race in the United States. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Mulder, J. D., and Hamaker, E. L. (2021). Three extensions of the random intercept cross-lagged panel model. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 28, 638–648. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2020.1784738

Mullis, I. V., Martin, M. O., Foy, P., and Arora, A. (2012). TIMSS 2011 international results in mathematics. Washington, DC: ERIC.

Negru-Subtirica, O., Pop, E. I., Crocetti, E., and Meeus, W. (2020). Social comparison at school: Can GPA and personality mutually influence each other across time? J. Pers. 88, 555–567. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12510

NEPS Network (2020). NEPS Starting Cohort 2: Kindergarten (SC2 9.0.0)NEPS-Startkohorte 2: Kindergarten (SC2 9.0.0). Available online at: doi: 10.5157/NEPS:SC2:6.0.0 (accessed July 14, 2022).

Neugebauer, M., Reimer, D., Schindler, S., and Stocké, V. (2013). “Inequality in transitions to secondary school and tertiary education in Germany,” in Determined to succeed? ed. M. Jackson (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press), 56–88. doi: 10.11126/stanford/9780804783026.003.0003

Orth, U., Clark, D. A., Donnellan, M. B., and Robins, R. W. (2021). Testing prospective effects in longitudinal research: Comparing seven competing cross-lagged models. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 120, 1013–1034. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000358

Parker, P., Nagy, G., Trautwein, U., and Lüdtke, O. (2014). “Predicting career aspirations and university majors from academic ability and self-concept,” in Gender Differences in Aspirations and Attainment, eds I. Schoon and J. S. Eccles (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 224–246. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139128933.015

Pietsch, M., and Stubbe, T. C. (2007). Inequality in the transition from primary to secondary school: School choices and educational disparities in Germany. Eur. Educ. Res. J. 6, 424–445. doi: 10.2304/eerj.2007.6.4.424

Relikowski, I., Yilmaz, E., and Blossfeld, H.-P. (2012). “Wie lassen sich die hohen Bildungsaspirationen von Migranten erklären? Eine Mixed-Methods-Studie zur Rolle von strukturellen Aufstiegschancen und individueller,” in Soziologische Bildungsforschung, eds R. Becker and H. Solga (Wiesbaden: Springer), 111–136.

Rothon, C., Arephin, M., Klineberg, E., Cattell, V., and Stansfeld, S. (2011). Structural and socio-psychological influences on adolescents’ educational aspirations and subsequent academic achievement. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 14, 209–231. doi: 10.1007/s11218-010-9140-0

Scharl, A., Carstensen, C. H., and Gnambs, T. (2020). Estimating plausible values with NEPS data: An example using reading competence in starting Cohort 6. NEPS Survey Papers. Bamberg: NEPS. doi: 10.5157/NEPS:SP71:1.0

Schindler, S. (2017). School tracking, educational mobility and inequality in German secondary education: developments across cohorts. Eur. Soc. 19, 28–48. doi: 10.1080/14616696.2016.1226373

Schnittjer, I., Gerken, A.-L., and Petersen, L. A. (2020). NEPS technical report for mathematics: Scaling results of starting Cohort 2 in Grade 4. NEPS Survey Papers, No. 45. Bamberg: NEPS.

Sewell, W. H., and Hauser, R. M. (1980). The Wisconsin longitudinal study of social and psychological factors in aspirations and achievements. Res. Sociol. Educ. Social. 1, 59–99. doi: 10.1352/2009.114.128-143

Sewell, W. H., and Hauser, R. M. (1993). A review of the Wisconsin Longitudinal Study of social and psychological factors in aspirations and achievements 1963-1992. Center for Demography and Ecology, Working Papers, 92–01. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Shapka, J. D., Domene, J. F., and Keating, D. P. (2006). Trajectories of career aspirations through adolescence and young adulthood: Early math achievement as a critical filter. Educ. Res. Eval. 12, 347–358. doi: 10.1080/13803610600765752

Stocké, V. (2010). “Der Beitrag der Theorie rationaler Entscheidung zur Erklärung von Bildungsungleichheit,” in Bildungsverlierer, eds G. Quenzel and K. Hurrelmann (Berlin: Springer), 73–94.

Usami, S. (2021). On the Differences between General Cross-Lagged Panel Model and Random-Intercept Cross-Lagged Panel Model: Interpretation of Cross-Lagged Parameters and Model Choice. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 28, 331–344. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2020.1821690

Vaisey, S., and Miles, A. (2017). What You Can—and Can’t—Do With Three-Wave Panel Data. Sociol. Methods Res. 46, 44–67. doi: 10.1177/0049124114547769

VanderWeele, T. J., Mathur, M. B., and Chen, Y. (2020). Outcome-wide longitudinal designs for causal inference: A new template for empirical studies. Statist. Sci. 35, 437–466. doi: 10.1214/19-STS728

Widlund, A., Tuominen, H., and Korhonen, J. (2018). Academic well-being, mathematics performance, and educational aspirations in lower secondary education: Changes within a school year. Front. Psychol. 9:297. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00297

Widlund, A., Tuominen, H., Tapola, A., and Korhonen, J. (2020). Gendered pathways from academic performance, motivational beliefs, and school burnout to adolescents’ educational and occupational aspirations. Learn. Instr. 66:101299. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2019.101299

Wooldridge, J. M. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data. 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Zimmermann, T. (2020). Social influence or rational choice? Two models and their contribution to explaining class differentials in student educational aspirations. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 36, 65–81. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcz054

Appendix

Keywords: aspirations, achievement, competencies, socials stratification, primary education, Germany, CLPM

Citation: Bittmann F (2022) Investigating the co-development of academic competencies and educational aspirations in German primary education. Front. Educ. 7:923361. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.923361

Received: 19 April 2022; Accepted: 08 August 2022;

Published: 25 August 2022.

Edited by:

Bibiana Regueiro, University of Santiago de Compostela, SpainReviewed by:

Qianqian Pan, Nanyang Technological University, SingaporeTania Vieites, University of A Coruña, Spain

Copyright © 2022 Bittmann. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Felix Bittmann, ZmVsaXguYml0dG1hbm5AbGlmYmkuZGU=

†ORCID: Felix Bittmann, https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0802-5854

Felix Bittmann

Felix Bittmann