- 1The Department of Educational Administration and Human Resource Development (EAHR), Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, United States

- 2The Department of Educational Leadership, Texas A&M University-Commerce, Commerce, TX, United States

COVID-19 pandemic was and continues to be a shock and a challenge to the entire world. This health and safety challenge found its way into the world of higher education, even in programs that were already delivered in online environments. In this study, we examined the perceptions of 79 developing principals enrolled in a Master of Education Degree program in Educational Administration at Texas A&M University in the United States as they processed the efficacy of a virtual professional development (VPD) leadership for a state certificate in Advancing Educational Leadership (AEL). The state agency has required AEL as a 3-day state-mandated face-to-face training which is a basic requirement for school leaders who evaluate teachers. In fact, per state policy, AEL was delivered in a face-to-face format since it began in 2015, but was transformed to a VPD format in 2020, for the first time, as a response to safety concerns resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. The Texas Education Agency indicated that the training would go back to a face-to-face format after Fall 2021; however, recently the Agency determined that virtual training could continue, along with face-to-face. Initially, this study was conducted to add information to the policy consideration as to whether to leave the option open for university principal preparation programs to offer the AEL virtually or face-to-face; however, with the alteration of the policy and with the findings of the study, we now provide empirical support, based on a a concurrent triangulation mixed methods design, for the Agency’s policy action. This study might be the first published in support of this AEL training policy.

Introduction

In March, 2020, few educators had any idea how a worldwide COVID-19 pandemic would impact their lives and the education of developing leaders in PreK-12 settings. Prioritizing safety of students and educators led to a big leap from face-to-face to virtual learning at the K-12 and college levels. Texas A&M University was no exception as the faculty members had to have an immediate response to the pandemic and move the delivery of courses and professional development (PD) including a Texas Education Agency (TEA) state-supported PD program, Advancing Educational Leadership (AEL) to be online. AEL is a 3-day PD program designed by the state education agency. Prior to COVID-19, AEL was mandatory face-to-face training and the original version of this training was under another title, Instructional Leadership Development (Region Four Education Service Center, 2022). In order to provide the training, professors or state-approved trainers must engage in a 3-day training of trainers (TOT) and be certified.

Advancing educational leadership training may be included in principal preparation programs or may be taken at state regional education service centers for the purpose of preparing principal candidates or other school leaders to become more effective as instructional leaders. School leaders who will have the responsibility of evaluating teachers are required to take this AEL PD (Texas Education Code §150.5001, Section, Texas Education Code [TEC], 2016). Completion of the AEL training is a prerequisite for becoming a certified teacher appraiser for the state’s Teacher Evaluation Support System (T-TESS). Though completing the AEL and T-TESS endorsements are not a requirement for becoming a certified principal in Texas, most university programs in Educational Administration afford opportunities for graduate students to complete, at a minimum, their AEL certification prior to graduation so they will be prepared to coach and assess the instructional process.

Based on the AEL Training Manuals Advancing Educational Leadership [AEL] (2015), AEL facilitates participants’ recognition of the connections and relationships between and among the major functions or strands of school leadership with five identified conceptual themes:

1. Creating Positive School Culture.

2. Establishing and Sustaining Vision, Mission, and Goals.

3. Developing Self and Others.

4. Improving Instruction, and

5. Managing Data and Processes.

These five themes are aligned to seven strands of AEL training (team building, effective conferencing, conflict resolution, goal setting, data gathering and analysis, teacher coaching and mentoring, and curriculum and instruction) and are designed to assist developing leaders in experiencing how the conceptual foundations of leadership are operationalized in a school context. The AEL framework is aligned to the new principal standards adopted by the Texas Education Agency [TEA] (2016) and further details the importance of the principal’s role as an instructional leader. The purpose of this study was to determine the perceptions of the 79 principal candidates, who agreed to participate in the study from the 83 principal candidates attending the AEL VPD, related to: (a) their satisfaction with the virtual format of the AEL VPD, (b) the most interesting experience during the virtual AEL VPD, and (c) recommendations related to enhancing the quality of virtual AEL VPD that could support or refute TEA’s policy implementation. Those principal candidates were, who were enrolled in a Master of Education Degree in Educational Administration at Texas A&M University in the United States.

Review of literature

We conducted a narrative review of literature (Davies, 2000) in which we reviewed studies found on principal preparation during the time period of the COVID-19 pandemic in order to construe the dominant challenges associated during that time. With this narrative review, we included periodicals, websites, and peer-reviewed journals. We searched the following databases: ERIC EBSCO, Academic Search, Pro-Quest, Google Scholar, and a general Google search with the following keywords: principal preparation programs during the pandemic, principal preparation online and COVID-19 pandemic, and online principal preparation programs during the pandemic. Only a few published articles were found specific to principal or educational leadership preparation programs, online or face-to-face, during the pandemic. Most published works that were found related to helping in-service principals to deal with the challenges of the pandemic in their schools.

Online learning had been implemented in universities in educational leadership programs in some locations around the United States long before the COVID-19 pandemic. In fact, the U.S. News and World Reports (2022) has ranked distance education graduate programs the past decade. Yet, Superville (2021) found challenges as to how the pandemic began to alter principal preparation programs. Upon interviewing four principal program national leaders, she found that the pandemic and the racial justice protests brought to light the need to diversify the principalship. She suggested that standardized testing entrance requirements could be waived or dropped, eligibility criteria could be broadened, grants and scholarships could be increased, and promising candidates could be recruited and identified by university faculty working with district administrators. Additionally, the leaders noted that preparation programs should be nimble and offer online programs that could increase racial, gender, and geographic diversity. In other words, preparation programs can improve the content of their courses to ensure equity, social justice, and social-emotional learning (Shaked, 2018, 2020; Superville, 2021).

One of Superville’s principal preparation program leader participants indicated that likely face-to-face programs would remain predominant after the pandemic, but programs may move into a hybrid format. Even so, the concept of online learning in higher education has been challenged during the COVID-19 time. For example, Hodges et al. (2020) argued that using the term, “online learning,” to describe what happened as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic might not be the suitable term. Instead, they used the term, “Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT).” They explained that typically before online learning there might be time for professors to make course preparation and arrangements, which was not the case in the ERT as professors, just as did teachers in schools, had to move to online all of a sudden (Hodges et al., 2020).

In general, as was observed in daily news accounts, virtual learning in higher education settings increased by necessity during the height of the pandemic and during major surges which universities were in session. The COVID-19 pandemic did increase the numbers of higher education faculty and students using online learning as a response and solution to remote and cross-border education (Chaka, 2020). Even prior to the pandemic, Markson (2018), concluded that online leadership preparation programs could be as effective as face-to-face programs as evidenced by the scores of developing leaders on the New York licensure assessment. While he concluded that he found no statistically significant evidence that one program was better than the other, he recommended that future research examine “instructors’ practices from the perspective of the students,” with the goal of “revealing certain online behaviors of instructors that produced higher satisfaction and more learning among online students” (p. 38). Additionally, Irby et al. (2020) prior to the pandemic reported on an online principal preparation program, which was grant-funded (Project Preparing Academic Leaders (PAL), U.S. Department of Education, T365Z170073), recruited potential school leaders in collaboration with school districts, served a diverse principal candidate pool, and shortened the time to graduation to more expeditiously accommodate the need for leaders in high-needs schools. The authors indicated that Project PAL may serve as a guide to other national program faculty who wish to work on socially responsible school leadership preparation programs serving high-needs students. Additionally, the PAL master’s program had positive results with 100% pass rates on our first group of test takers on the new 268 principals’ test. Project PAL is inclusive of diverse, socially responsible perspectives with bilingual/ESL courses and leadership courses, and it is completed within four semesters with three courses per semester and with practicum/residency being a yearlong (three semesters) and with an intensive summer residency included.

Purpose and research questions of the study

The purpose of this study was to determine the perceptions of the 79 principal candidates of an AEL VPD related to: (a) their levels of satisfaction with the virtual format, (b) the most interesting experience during the AEL VPD, and (c) recommendations for enhancing the quality of virtual AEL VPD that could support or refute the state education agency’s policy implementation. The research questions are as follows:

(1) What is the perception of a group of principal candidates’ satisfaction with the virtual format of the AEL VPD?

(2) What is the perception of a group of principal candidates related to their most interesting experience during the AEL VPD?

(3) What are participants’ recommendations to enhance the quality of virtual AEL VPD that could support or refute the state education agency’s policy implementation?

Theoretical framework

In this study, we used theoretical assumptions from two theories: the multimodal model theory for online education developed by Picciano (2017) and the self-directed learning (SDL, Merriam, 2001). In the multimodal model theory, Picciano explained how online education focuses on the learning community, but in a virtual format. In this, the online learning can include multiple learning components equivalent to, or may be replacing, those of the face-to-face learning environment. These components can include content, social emotional, self-paced, dialectic/questioning, evaluation/assessment, collaboration/student generated content/peer review, and reflection.

The SDL theory, similar to other adult learning theories, helps in understanding how adults construct their learning through making connections with previous knowledge and experience. Based on the SDL theory, providing adult learners with learning environments in which they can communicate their opinions; share their knowledge and reflect on the new learning content can help them to better understand new content and incorporate it with their previous knowledge (Merriam, 2001). To this end, we found that combining theoretical assumptions from the two theories provides an appropriate theoretical framework for our study. This is because the multimodal model theory helps in interpreting how different technological tools utilized in the AEL VPD such as Breakout Rooms, Chat Box, White Board, and Jamboard provided opportunities to participants to collaborate with each other in a virtual learning environment. The SDL, however, helps to explain how through such collaboration, interactions, and reflections, which represent the core of SDL theory, participants, as adult learners, were able to construct their learning.

Materials and methods

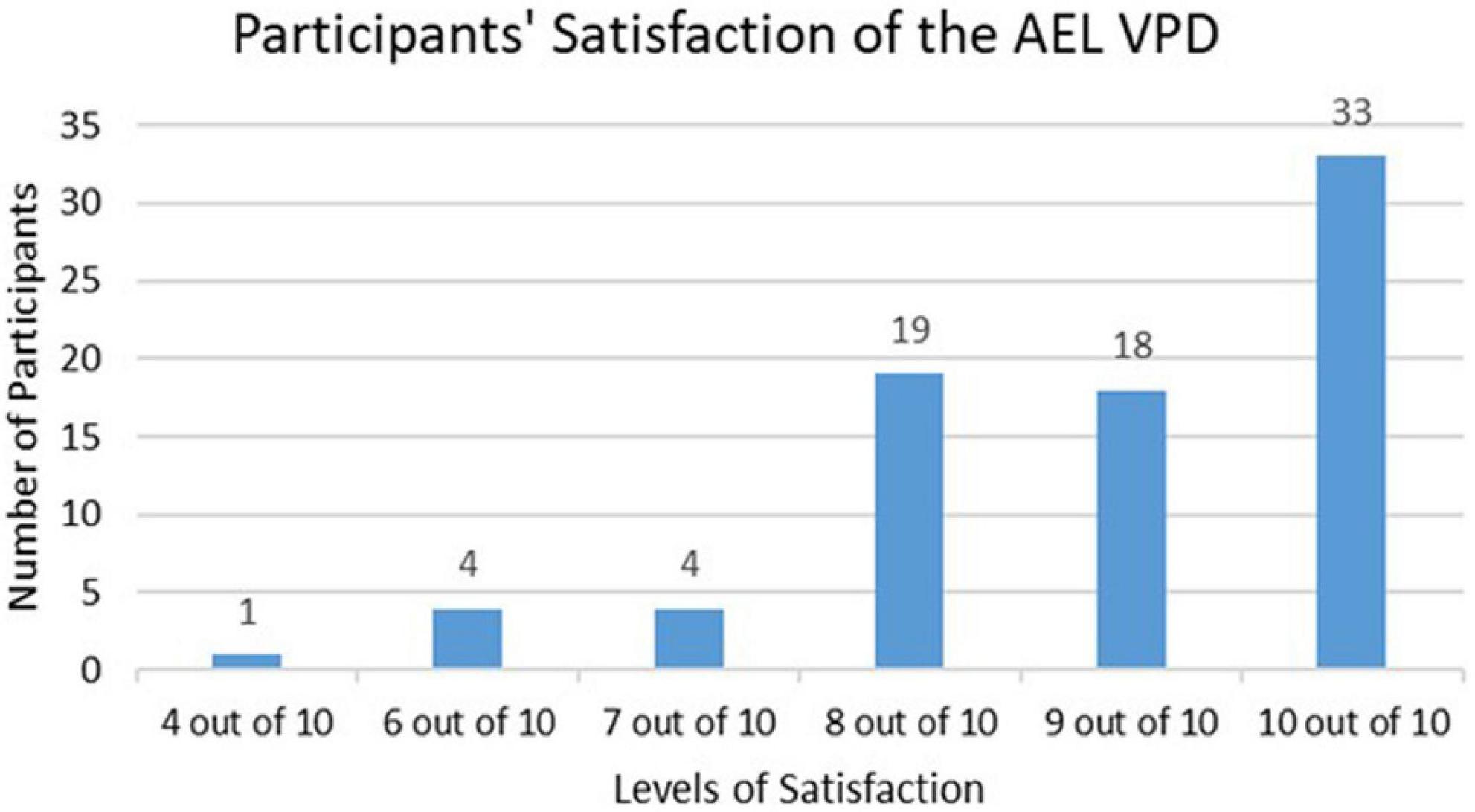

A concurrent triangulation mixed methods design (Schoonenboom and Johnson, 2017) was used in this study. The use of mixed-methods design allows researchers to collect and analyze quantitative and qualitative data about a phenomenon (Doyle et al., 2009). However, the concurrent mixed methods design refers to how researchers can combine quantitative and qualitative research designs concurrently to triangulate for the methods in the study and not in a separate sequential order (Schoonenboom and Johnson, 2017). Schoonenboom and Johnson (2017) explained that mixed methods design is appropriate when the purpose of researchers “is to expand and strengthen a study’s conclusions and, therefore, contribute to the published literature.” (p. 110). A concurrent triangulation mixed methods design was appropriate for this study because we wanted to combine and analyze the quantitative and qualitative data about the perceptions of the 79 principal candidates who participants of this study related to the AEL VPD. Given the fact that it was the first time for the AEL to be delivered virtually, we wanted to provide policymakers with triangulated evidence about participants’ perceptions of the AEL VPD. Recently the agency determined that virtual training could continue, along with face-to-face. Our ultimate goal is to provide empirical support for the agency’s policy action. This study might be the first published for this AEL training policy. In the quantitative part of the study, we used descriptive statistics with measures of frequency (Mishra et al., 2019). Mishra et al. (2019) noted, “Frequency statistics simply count the number of times that in each variable occurs” (p. 68). This type of descriptive statistics was appropriate for the study as it allowed us to count the numbers of participants who responded to the one, 10-point Likert scale item, as shown in Figure 1, the 16, five-point Likert scale items and to calculate the percentages of those responses as well as the mean for each of the survey items, as displayed in Tables 1, 2. In the qualitative part of the study, we used a phenomenological research approach (Paley, 2017). Paley (2017) argued that this approach allows researchers to look closer at individuals’ experiences and to construct understanding of them. The phenomenological research approach was appropriate for the study as it helped us in exploring participants’ experiences of the AEL VPD through analyzing triangulated sources of qualitative data obtained from participants responses to four open-ended questions in the survey as well as their entries to the chat box over the three years of the AEL VPD.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics to explore satisfaction of the technological tools used in the AEL VPD.

Context of the study

As a part of a U.S. Department of Education (T365Z170073) grant, PAL (Irby et al., 2017, 2020), to support the development of bilingual school principals, 83 Master’s degree students had the benefit of an experienced team to facilitate the AEL training. The grant provided an opportunity for the Master’s Program faculty to think strategically and deeply about how to best support the objectives of the grant, while also focusing on how to address those objectives in a virtual environment (Irby et al., 2020). This might seem ironic in that the educational administration program was already an online program. As a result, one might assume that continuing to provide instruction online would be a simple feat. However, the state had developed AEL specifically as a face-to-face intervention, and the online training had not been tested.

The AEL professional development team decided to closely examine how best to support these common experiences in a virtual environment. The team included certified AEL trainers who are the principal investigators, two co-principal investigators, three university professors, the lead coordinator of the PAL project, the coordinator of a second U.S. Department of Education grant (1894-0008. Accelerated Preparation of Leaders for Underserved Schools (A-PLUS)), an assistant instructor for both grants, and two educational leadership doctoral students.

The intervention

On March 19, 2020, there was a total school closure across Texas due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Texas Education Agency (TEA) made some policy adjustments in order to adjust the education services to meet this closure (Texas Education Agency [TEA], 2020). Thus, Texas A&M University and other university principal preparation programs responded to these changes by converting the face-to-face training including the AEL to be virtual. The conversion was a major undertaking; therefore, Region 13 trainers. Hosted a virtual 1-day training on May 26, 2020 and invited all AEL trainers to explain the virtual changes. The AEL team attended the 1-day training of trainers (TOT) that helped them to adjust their roles and assignments in the 3-days of the virtual AEL VPD. These meetings were centered on comparing the virtual AEL manual and the face-to-face one to determine the changes and to specify how each activity was to be implemented in the new VPD format.

The AEL team determined the virtual changes to include: (a) the group work changed to be virtual groups in breakout rooms; (b) flash cards/sticky notes were changed to be Jamboard (on Google); (c) flipcharts became virtual whiteboard; and (d) hard copies materials and registration becomes online Google Drive folders. In the AEL of 2020, Project PAL Lead Coordinator volunteered to be the technical trainer who would use technology to facilitate the AEL embedded activities behind the scenes. To ensure that technology would run smoothly during the AEL VPD, the technical trainer hosted one-on-one meetings with the other four AEL trainers to determine the activity/activities each trainer would lead and the timeframe needed for each activity. The technical trainer helped in creating the Google folder for participants, the Powerpoint slide sequence, the virtual activities using ZOOM Breakout Rooms, White Board, polls, Chat log features, Qualtrics survey, and Google Jamboard.

Data collection

At the end of the third day of the AEL VPD, a post survey was sent to the 83 principal candidates who attended it. They were asked to complete the survey within a week, if they were interested to be part of the study. Only 79 principal candidates completed the survey. We also collected data from principal candidates’ entries in the Chat Box as they responded to trainers, other participants, expressed their opinions and shared their experiences about the training activities and questions posed by other individuals. At the end of each AEL VPD, ZOOM software sent an email to the ZOOM meeting host, who was the technical trainer, with a link to the recording and attached transcripts of the Chat Box to the email. These were the two data sources used in the study.

The theoretical drive, development, and validation of the survey instrument

The survey instrument used in the study was developed based on the theoretical framework of the study that included SDL theory of adult learning (Merriam, 2001) and the multimodal model theory for online education (Picciano, 2017) as well as literature on online learning and the use of ZOOM software in teaching online courses for adult learners (Barbosa and Barbosa, 2019) and how ZOOM was a proper solution to address all of the sudden movement from face-to-face to virtual learning (Chaka, 2020). To this end, in the development of the survey items, we framed them around some of the behaviors described in the SDL theory as necessary to exist in a learning environment for adult learners in order to advance their learning experiences. Examples of those behaviors include providing adult learners with opportunities to; collaborate and communicate with each other, reflect on previous knowledge and experience and encourage them to share their thoughts and opinions about their learning. We also included in the development of the survey items on the technological tools used in the AEL VPD. This is because Picciano (2017) explained in the multimodal model theory how technological tools could provide learners with rich opportunities of learning similar to the face-to-face ones and even better.

The survey included 29 items in three sections. The first section included eight items on demographics, ethnicities, and work experience. The second section included 17 quantitative items: one, ten-point Likert scale to assess participants’ levels of satisfaction of the AEL VPD. Nine items on the survey were intended to further assess participants’ satisfaction of AEL VPD coordination such as time allocated for activities, the use of technology, communication among participants, and whether they would recommend AEL to continue to be virtual in the future). Seven items were intended to assess participants’ perceptions of each of the technological tools used in the AEL VPD. The third section of the survey included four, open-ended qualitative questions related to the most interesting experiences participants perceived about the AEL VPD, how technological tools used in the AEL VPD were helpful, and their recommendations for enhancing the AEL VPD in the future. The four questions were: (a) what was the most interesting experience during the AEL VPD?, (b) how do you think the different technological tools (e.g., Breakout Rooms, chat box, Jamboard, White Board) assisted you in the AEL VPD?, (c) what recommendations do you have to better enhance the quality of the AEL VPD in the future?, and (d) are there any other comments about AEL VPD would you like to share?

We used two validation techniques in the survey that were; content validity and face validity (Lynn, 1986; Heale and Twycross, 2015). Content validity refers to the degree to which the instrument used covers the content it is intended to measure whereas the face validity assesses to the relevancy of the instruments to measure what it was designed for. To this end, two of the research team worked on developing the survey that was shared on Google drive where the other members of the research teams suggested edits and added comments to the document. Once the team had agreement on the final version of the survey, it was sent to participants via Qualtrics software provided by Texas A&M University.

Study sample

We employed a convenience sampling strategy (Saunders, 2012) to recruit the 79 participants for this study. Saunders (2012) defined the convenience sample as the human subjects that are available, accessible, and willing to participate in the study. The participants were from two cohorts in the educational administration program. One cohort participated in May 2020 and the second in May 2021. Of the 79 principal candidate participants, 69 were female, nine were male teachers and one selected rather not to say gender. The participants were ethnically diverse. The sample included 44 Latinx, 20 European-American, six African-American, two Asian/Asian-American, one Native-American, and six participants from other races/ethnicity. Teaching experience varied with 19 of them having 5 years of teaching experience or fewer, 24 of them having between 6 and 10 years, 22 of them having between 11 and 15 years, and 14 of them having more than 15 years of teaching experience. As for district type, 13 of the participants served in rural school districts, 36 in urban, and 30 suburban school districts.

Data analysis

To analyze the quantitative data of the study, we used descriptive statistics with measures of frequency (Mishra et al., 2019). To this end, we used the numbers of participants’ responses to each of the 17 Likert items from Qualtrics results to develop visual representations (Figure 1 and Tables 1, 2) of participants’ perceptions of the AEL VPD. As shown in Figure 1, we created a chart on participants’ levels of satisfaction using the one, ten-point Likert scale item. As for the remaining 16, five-point Likert scale items we divided them into two groups of items. The first group included nine items that were used to develop Table 1 with descriptive statistics assessing participants’ perceptions of the coordination of the AEL VPD. The second group included seven items that were used to develop Table 2 with descriptive statistics assessing participants’ perceptions of the technological tools in the AEL VPD. On the five Likert scale, we combined responses of strongly agree and agree to represent participants’ agreement to each statement. Similarly, we also combined strongly disagree and disagree to represent participants’ disagreement to each statement. We kept participants’ responses that were neutral as a separate response.

To analyze the qualitative data, two members of our research team read through the qualitative data collected to make meaning and to explore descriptive codes. They worked on identifying themes that emerged from the data. The four themes were identified aligned to the research questions: (a) participants’ satisfaction with the virtual format of the AEL VPD; (b) participants’ perceptions of the technological tools employed during AEL VPD; (c) participants’ most interesting experiences about virtual AEL Training; and (d) participants’ recommendations regarding enhancing the quality of virtual AEL VPD for future AEL trainings.

We used NVivo 11 with the nodes feature to explore the descriptive codes and to identify the sub-themes and the main themes. Zamawe (2015) noted that NVivo has the nodes feature which is appropriate when researchers utilize thematic analysis. To keep the identity of participants in the study confidential, we used the pseudonym, ‘TL’ to refer to ‘teacher leader’ (the principal candidates). Since we had 79 participants, we used TL1 to TL 79 to represent all the 79 participants in the study.

Credibility and trustworthiness of the study

We also followed three main strategies to increase the credibility and trustworthiness of the study. These strategies were: (a) methods of data collection triangulation (Cope, 2014), (b) investigator triangulation (Johnson, 1997), and (c) low inference descriptors (Johnson, 1997). To triangulate for data collection, we used two data sources (participants’ responses to the survey and their Chat Box entries over the 3 days of the AEL VPD), as stated earlier. Cope (2014) noted that, “With methods triangulation, the researcher uses multiple methods of data collection in an attempt to gain an articulate, comprehensive view of the phenomenon” (p. 90). Further, for the investigator triangulation (Johnson, 1997), two members of the research team worked on identifying the themes emerging from the data and having consensus on the wording. Then two other team members developed sub-themes for data analysis based on the main themes with discussions with the other research team members. As for the low inference descriptors (Johnson, 1997), we had direct quotations from what the participants reported related to their perceptions on the AEL VPD training.

To also increase the validity of the data collected from participants, we relied on the rapport that was built with participants. Building rapport is important to ensure that participants feel comfortable sharing their thoughts about a phenomenon (Cope, 2014). In our study, rapport was evident because the trainers of the AEL were professors in the master programs that principal candidates attended. This rapport helped participants to share their perceptions and recommendations about the AEL VPD.

Results

We reported results of the study based on the three research questions. The first question on participants’ satisfaction of the AEL VPD was meant to be answered using the quantitative data from the survey. However, we found that some of the participants’ qualitative perceptions were relevant to those questions and supported the quantitative findings; therefore, we added them to the quantitative findings of those questions, as well. As for the second and third research questions on participants’ most interesting experiences during the AEL VPD, and recommendations to enhance the AEL VPD that could support or refute the state education agency’s policy implementation, we used qualitative data obtained from the open-ended questions in the survey and the transcripts of the Chat Box from the 3 days of the AEL VPD.

Research question 1: What is the perception of a group of principal candidates’ satisfaction with the virtual format of the advancing educational leadership virtual professional development?

To assess participants’ levels of satisfaction with the virtual format of the AEL VPD, we examined participants’ perceptions related to three areas: (a) participants’ general satisfaction levels of the AEL VPD, (b) participants’ satisfaction of the coordination of the AEL VPD, and (c) participants’ satisfaction of the technological tools used in the AEL VPD. We presented findings related to those three areas as follows:

Participants’ general satisfaction levels of the advancing educational leadership virtual professional development

We included a 10-point Likert scale item in the survey where number one on the scale represented the least level of participants’ satisfaction and number ten represented the most. This item was, “On a scale of 10, how would you express your satisfaction about the virtual format of the AEL training with 1 being the least satisfied and 10 the most satisfied?” As shown in Figure 1, out of the 79 participants who completed the survey, 33 participants (42.%) selected number ten 18 participants (23%) selected number nine, 19 participants (24%) selected number eight, four participants (5%) selected number seven, and four participants (5%) selected number six. This means that 78 out of the 79 (99%) were satisfied with the AEL VPD and 70 participants (89%) were highly satisfied as they rated their levels of satisfaction between eight and ten. Only one participant (1%) was not satisfied about the AEL VPD as she/he selected number 4.

Participants’ satisfaction of the coordination of the advancing educational leadership virtual professional development

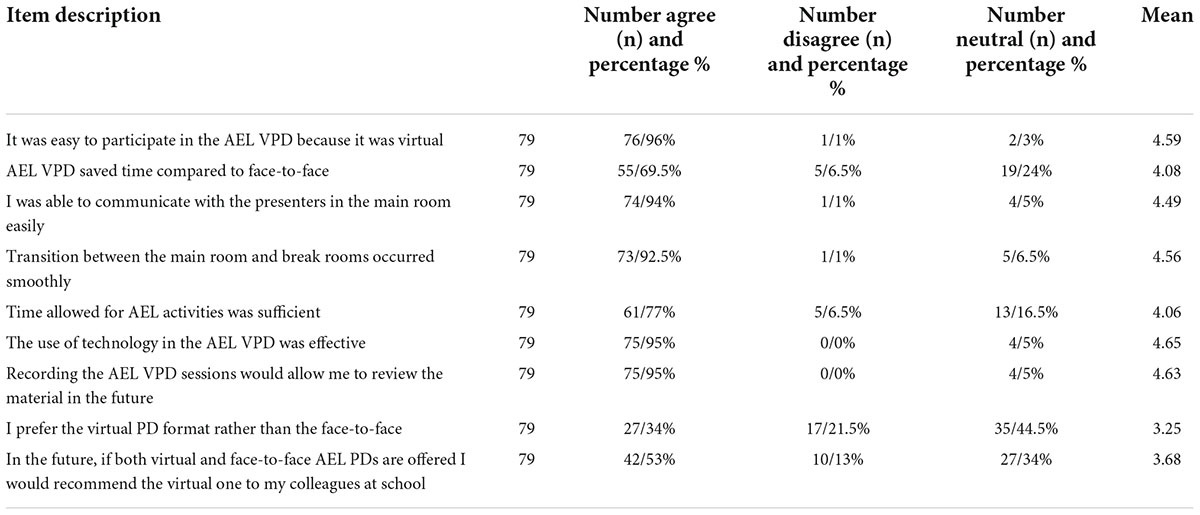

To investigate participants’ satisfaction with the coordination of the AEL AEL such as, time allocation, communication, and the use of technology, we used a group of nine five-point Likert scale items. As explained earlier in the data collection section, we collapsed the five-point Likert scale item results into three categories: disagree, neutral, and agree to have a better visual representation of them.

We used Table 1 with descriptive statistics that included the numbers, percentages of participants who agreed, disagreed, or were neutral as well as the means of the five-point Likert scale for each of the nine items related to participants’ perceptions of the AEL VPD. The nine items were: (a) it is easy to participate in the AEL VPD, because it was virtual; (b) AEL VPD saved time compared to face-to-face; (c) I was able to communicate with the presenters in the main room; (d) transition between the main room and break rooms occurred smoothly; (e) time allocated for AEL VPD activities was sufficient; (f) the use of technology in the AEL VPD was effective; (g) recording the AEL VPD sessions would allow me to review the material in the future; (h) I prefer the AEL VPD rather than the face-to-face; and (i) in the future, if both virtual and face-to-face AEL VPDs are offered, I would recommend the virtual one to my colleagues at school.

As shown in Table 1, participants’ responses indicated that the mean value of these questions ranged from 3.25 to 4.65 which concludes that participants in general were satisfied with the AEL VPD. To give more specific examples, 76 participants (96%) agreed that it was easy for them to participate, because it was virtual with a mean of 4.59. Fifty-five participants (69.5%) agreed that it saved time compared to the face-to-face format with a mean of 4.08. Transitioning between the main room and the Breakout Rooms was perceived by 73 participants (92.5%) as occurred smoothly with a mean of 4.56. Time allowed for AEL VPD activities was perceived by 61 participants (77%) as sufficient with a mean of 4.06. Participants perceived the use of technology at the AEL VPD was effective; 75 participants (95%) agreed to that item with a mean of 4.65 and only four participants (5%) disagreed with it. The same number of participants 75 representing the same percentage (95%) agreed that recording the sessions of the AEL VPD would allow them to review the material in the future with a mean of 4.63.

Findings about participants’ perceptions of VPD in general, and the AEL VPD in particular worth noting. This is because only 27 participants (34%) seemed to prefer VPD over face-to-face with the lowest mean of 3.25. However, the situation was different when participants were asked about their preference of the AEL VPD versus the face-to-face format. Forty-two participants (53%) expressed their preference of the virtual format if both virtual and face-to-face AEL PDs were to be offered in the future with mean 3.68.

In addition to the quantitative findings in which participants expressed their satisfaction about the coordination of the AEL VPD through the nine, five-point Likert scale items, participants also shared qualitative perceptions. For example, TL 4 explained that the virtual format was a proper option given the challenge of COVID and not being able to attend in person. She noted, “I thought it (AEL VPD) was great especially since you all had to move from an in-person training to a virtual training.”

Other participants found AEL VPD convenient to them as it saved time. For example, TL 7 reported, “I enjoyed meeting virtually. It does save time instead of face-to-face.” TL 39 praised coordination of the AEL VPD as it went smoothly. She said, “You all did an absolutely AMAZING job pulling off a virtual AEL training. I know that there was a lot of prep work that took place prior to the training for it to be so smooth for the attendees.” All in all, the participants were satisfied with the coordination of the virtual training and believed that the AEL VPD worked well for them.

Participants’ satisfaction of the technological tools used in the advancing educational leadership virtual professional development

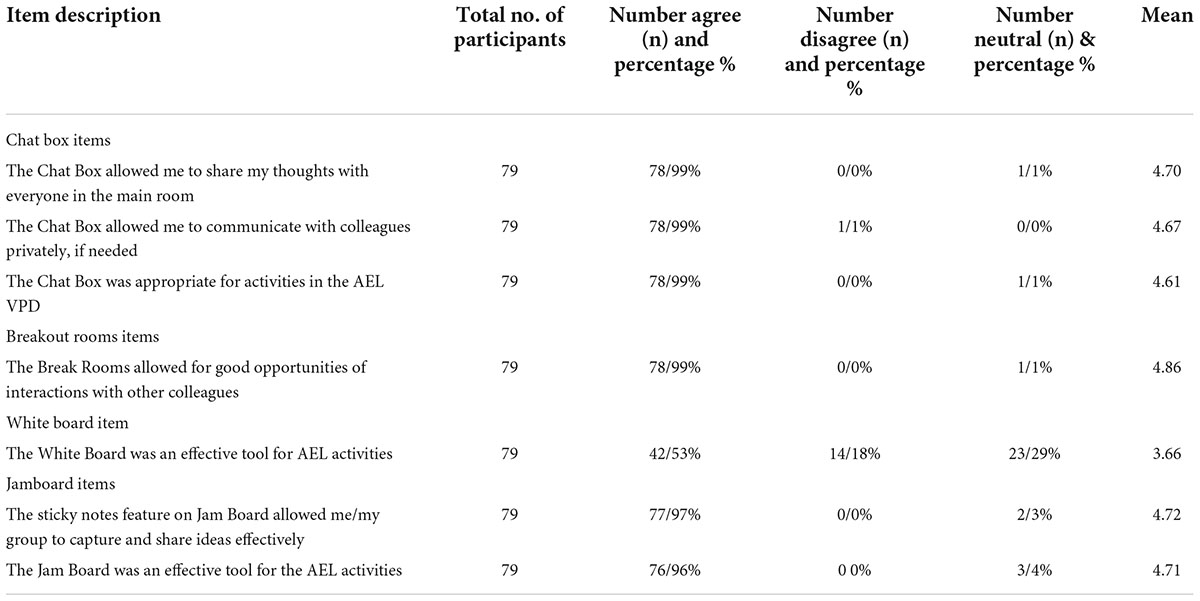

To assess participants’ perceptions of the technological tools utilized in the AEL VPD, we used a group of seven, five-point Likert scale items to which the participants responded. Those seven items were: (a) the Chat Box allowed me to share my thoughts with everyone in the main room; (b) the Chat Box allowed me to communicate with colleagues privately, if needed; (c) the Chat Box was appropriate for the activities in the AEL VPD; (d) the Break Rooms allowed for good opportunities of interactions with other colleagues; (e) the White Board was an effective tool for the AEL activities; (f) the sticky notes feature on Jamboard allowed me/my group to capture ideas effectively; and (g) the Jamboard was an effective tool for the AEL activities.

As shown in Table 2, we reported descriptive statistics on participants’ perceptions of the technological tools by including the numbers and the percentages of participants’ responses to each of the seven items from the survey as well as the mean for each of those items. Also, to present participants’ perceptions about the technological tools utilized in the AEL VPD in-depth, we supported the descriptive statistics associated with each tool with some of the qualitative perceptions about it. Our goal was to help the readers of the study to see how the participants perceived those technological tools as effective from quantitative and qualitative perspectives. In the following, we reported qualitative and quantitative findings on the four main technological tools used in the AEL VPD: Chat Box, Breakout Rooms, Jamboard, and White Board.

Technological tool: Chat box

Quantitative data indicated that participants perceived the Chat Box as an effective tool that allowed them to share their thoughts comfortably. There were three items on the survey related to the use of the Chat Box. Seventy- eight participants (99%), with a mean of 4.70, agreed the Chat Box was appropriate for the activities in the AEL VPD with a mean of 4.67. The second item related to the Chat Box asked participants’ opinions about if they were able to communicate with colleagues privately if needed; 78 participants (99%) agreed with a mean of 4.67. The third item on the Chat Box was related to perceiving the Chat Box was appropriate for activities in the AEL VPD; 78 participants (99%) agreed with this survey item with a mean of 4.61.

The qualitative findings about participants’ perceptions of the Chat Box were similar to the quantitative ones. For example, TL 21 said, “The chat box allowed everyone to participate and have their voice heard. It allowed everyone an opportunity to share thoughts, without the face-to-face intimidations that sometimes we can feel.” Similar to this, TL 40 explained how the Chat Box advanced her engagement with a larger group of participants where she was able to interact with others without interrupting presenters or distracting attendees. She said:

Chat Box allowed us to process during the training and engage with everyone in the training versus talking to your neighbor at the table in an in person setting which can be disruptive to others. It also allowed other trainers to engage in the chat to clarify misconceptions, answer questions, affirm, extend thinking, and provide encouragement while another presenter was speaking.

Technological tool: Breakout rooms

Participants perceived the Breakout Rooms as the most effective technological tool in the AEL VPD. There was one item on the survey assessing participants’ perceptions of how the Breakout Rooms facilitated their interactions. Seventy-eight participants (99%) agreed that the Breakout Rooms allowed for good opportunities of interactions with other colleagues with a mean of 4.86.

Based on the qualitative data collected for the study, many participants also think that Breakout Rooms provided them with the most interesting experience in the training that advanced their collaborations through small group discussions. TL 9 said, “Breakout Rooms allowed for small group interaction face to face.” Aligned with this, TL 14 noted, “The breakout rooms were something I wasn’t expecting. It definitely made the experience a lot better because I was able to talk to classmates that I probably never would have.” Similar to this, TL 66 reported, “The chat room kept me connected to other members and the instructors.”

TL 19 explained why she thought the Breakout Rooms were the most interesting. She mentioned, “The breakout room was in my opinion the most enjoyable part of the training because it gave us all a great opportunity to share out and listen to our peers.” Technological Tool: Jamboard. The Jamboard was perceived by participants as an effective technological tool in the AEL VPD. There were two items on the survey related to the use of the Jamboard. The first item was related to the sticky notes, which is a feature of the Jamboard. Participants thought that sticky notes allowed them as individuals and as groups to capture and share their ideas effectively. Seventy-seven participants (97%) agreed with this survey item with a mean of 4.72. The second item on the Jamboard was related to the Jamboard being an effective tool for the AEL activities. Seventy-six participants (96%) agreed to this item with a mean of 4.71.

Qualitatively, participants highlighted that the Jamboard allowed for good communication among participants, particularly to capture and share thoughts of individuals and groups. TL 2 noted, “The Jam Board allowed us to better communicate with our colleagues.” TL 15 explained, “Enjoyed the JamBoards to see new ideas and reflect on different practices.” Similar to this, TL 23 indicated, “The jamboard was great because we got to write our own ideas as well as see everyone else’s ideas.” TL 4 said, “I loved the Jam Board. This was so cool and I want to use it in my personal classroom.” While the Jamboard was perceived by the majority of participants as effective, a few participants seemed to have concerns about it. For example, TL 18 noted, “Jamboard only allows a certain number of participants which limits its effectiveness in simultaneous interactions.”

Technological tool: White Board

The White Board was perceived as the least effective technological tool in the AEL VPD. There was one item on the survey that assessed participants’ perceptions of how the White Board was an effective tool for the AEL activities. Forty-two 42 participants (53%) agreed that the White Board was an effective tool for the AEL activities with the lowest mean of 3.66. Twenty-three participants (29%) were hesitant to evaluate its effectiveness of the White Board in the AEL VPD and, thus, selected the neutral response on the five-point Likert scale. Fourteen participants (18%) disagree related to the White Board being an effective technological tool in the AEL VPD.

Qualitative findings on the White Board were aligned with the quantitative ones reflecting participants’ perceptions that the White Board was not a very effective technological tool in the AEL VPD. Particularly, participants reported that this tool was not effective compared to the other tools used. For example, TL 1 mentioned, “All (technological tools) were great ways to share ideas, with the exception of the White Board.” TL 18 said, “I had difficulty seeing the value in Whiteboard; while I understand it was to record our thoughts, This could have been achieved in a Google Doc just as easily.” TL 46 noted, “I enjoyed the breakout rooms and chat box, but I was not a fan of White Board or Jam Board.” TL 77 stated, “Some I was not familiar with at all (White Board) and was consumed by trying to use it.”

Research question 2: What is the perception of a group of principal candidates related to their most interesting experience during the advancing educational leadership virtual professional development?

When participants were asked in one of the open-ended questions in the survey about the most interesting experience of the virtual AEL VPD, participants seemed to have been divided into three groups. The first group believed collaboration with other people was their most interesting experience. The second group thought that Breakout Rooms were their most interesting experience. However, the third group shared some of the takeaways from the AEL VPD content, activities, and trainers as their most interesting experience. Thus, we developed three main themes based on what the three groups of participants believed were the most interesting as follows: (a) collaboration with different people in the AEL VPD, (b) Breakout Rooms allowed for interaction with other members, and (c) AEL training’s content, activities, and trainers. In the following, we highlight some of the participants’ perceptions associated with the three themes on the Breakout Rooms.

Collaboration with different people in the advancing educational leadership virtual professional development

Thirty-one participants perceived collaboration with different people as their most interesting experience in the AEL VPD. They explained how collaboration with new people, and people they know, but have not met for long, provided them with opportunities to share their thoughts and learn from each other. For example, TL 23 explained, “Having the opportunity to meet new people and to put faces with names was great!” TL 6 noted that the most interesting experience was “Getting to interact with different people and have meaningful conversations.” TL 17 stated, “It was interesting to talk to others about the different types of campuses and how situations varied.”

Collaboration was also perceived by some participants as adding to their own experiences. For example, TL 63 said, “Listening to people’s experiences and how they would handle the situation or problem.” Similarly, TL 21 noted, “Getting to communicate and collaborate with the cohort members on their experiences was great.” Aligned with this TL 22 added, “The ability to collaborate and discuss topics with fellow cohort members provided a unique opportunity for rich conversation.”

Breakout rooms allowed for interaction with other members

Twenty eight participants perceived the Breakout Rooms as the most interesting aspect in the AEL VPD. They explained how those rooms provided them with the space to interact with other members in the AEL VPD. For example, TL 35 said: “The most interesting was definitely the break rooms. It allowed for more one on one interaction and time to reflect, speak, and hear other perspectives.” Similar to this TL 17 noted, “I enjoyed the breakout rooms and being able to talk with all of the different cohort members that I hadn’t had the chance of working with yet.” Participants also explained how the Breakout Rooms allowed them to be more focused on working together to complete tasks. TL 37 said, “The breakout rooms were a wonderful way to interact with a group over particular tasks or discussions. Very helpful and engaging.”

The Breakout Rooms were also perceived by some participants as an opportunity to meet with each other in small groups, which advanced their chance to get to know each other better and learn form each other more. For example, TL 42 explained, “I really appreciated the breakout sessions. It allowed me to make connections in small groups with others in my cohort and other cohorts. Just great.” Similar to this TL 44 stated, “The breakout rooms and being able to connect with other future leaders.” TL 67 said, “The breakout rooms allowed me to hear different experiences from others.”

Advancing educational leadership training’s content, activities, and trainers

Seventeen participants indicated that the most interesting aspect of the AEL virtual learning experience was the content of the training itself, the activities included and how the trainers facilitated those activities. To get examples of AEL training content, TL 5 indicated, “I loved developing and learning about the vision and mission statements.” TL 8 reported, “I especially thought the working on critical dialogue with the coaching opportunities was interesting and powerful.” TL 55 said, “The videos from different leaders. I was able to obtain so much in a short duration of time.”

As for the AEL activities, TL 19 noted, “I enjoyed the activities the most. Learning the themes and building blocks.” TL 66 reported, “The rattlesnake bits were really good. They did come out of nowhere and it was nice to brainstorm with a cohort member what needed to be done.” Participants also believed that the video embedded in the AEL VPD provided rich information and some activities provided opportunities for simulation. For example, TL 55 said, “The videos from different leaders. I was able to obtain so much in a short duration of time.”

Trainers, or professors who led the AEL VPD, were perceived by some participants as the most interesting experience in the training. Participants believed that the trainers prepared well for the training and succeeded to make it more individualized based on the needs of the trainees. For example, TL 32 noted, “I want to give a shout out to the professors too for their incredible amount of knowledge and training. Very beneficial training!” Similar to this, TL 48 said, “The chosen professors, X and Y were great and truly provided their individual touch to the presentation.” TL 49 noted, “Presenters and facilitators did a great job!” TL 77 said, “I appreciate my professors taking the time to engage in the training with us.”

Research question 3: What are the recommendations regarding enhancing the quality of the virtual advancing educational leadership virtual professional development that could support or refute the state education agency’s policy implementation?

We divided participants’ recommendations into two main categories: (a) Participants’ recommendations to enhance the quality of future AEL VPD and (b) Participants’ recommendations that could support or refute the state education agency policy implementations. We present each of the two categories of recommendations as follows.

Participants’ recommendations to enhance the quality of future advancing educational leadership virtual professional development

Participants shared recommendations for enhancing the quality of AEL VPD related to three main areas: (a) increasing time allocated for activities in Breakout Rooms, (b) adding more breaks and increasing time for breaks, and (c) sending an agenda and overview in advance.

Increasing time allocated for activities in breakout rooms

Fifteen participants recommended allocating more time for the Breakout Rooms when the AEL VPD is delivered again in the future, if possible. They thought that would give more individuals opportunities to share their opinions in each activity. TL 18 noted that, “I would increase the time in breakouts because many times it was too short and peers got cut off in the middle of their opinions.” Similar to this TL 16, said “Just allow more time if possible during some break out sessions as we did get cut off from time to time.” Similarly, TL 55 noted, “Allow a little more time with some of the breakout rooms. I feel that 2 or 3 min is not enough time to fully articulate a point, strand, or theme presented.”

Some participants recommended that trainers revisit the times allocated for each activity to make sure that assigned times are appropriate based on the time expected for participants to complete those activities in. For example, TL 31 noted, “Time and pacing. Some areas seemed rushed, while others had too much time.” Other participants recommended that presenters make sure that everyone is back from the Breakout Rooms before they start another activity. TL 25 said, “I enjoyed the virtual training. There was some lag time between breakout rooms and lecture, so I would recommend for the instructor to wait a minute or two before beginning the topic.” Similar to this TL 47 said “Smoother transitions in different technologies and presenters.”

Adding more breaks and expanding time for current breaks

Twelve participants also recommended adding more breaks as well as expanding time allocated for current breaks. They believed that the online training was intensive and such breaks could help them cope with the information provided in it. TL 10 said, “Maybe give 6–7 min or rest or break time every hour.” Similar to this TL 9 noted, “A little more break time or more frequent breaks.” TL 37 recommended improving the schedule by allowing more time for breaks. She stated, “Improve schedule and/or possibly more breaks, especially after lunch. After lunch there needs to be more interactive and engaging pieces.” Similar to this, TL 46 said, “A little more time with colleagues, and a 5-min break each other to stretch the legs.” TL 72 noted, “Longer breaks. There were times I needed to leave the room but was scared I’d get called on.” Similar to this TL said 15, “Shorter amount of time, sitting too long for 3 days looking at the computer is a bit exhausting and overwhelming.” Some participants even asked to increase the number of days assigned for the training. For example, TL 78 noted, “Maybe spread it out over 2 or 3 weekends? Three consecutive days was a bit difficult.”

Sending agenda and overview in advance

Five participants recommended sending more information about the AEL Training or maybe an agenda could help attendees have a better idea about the timeline for the training. TL 20 said that, “I think it was great the way it was. Maybe give a little overview through email before the actual first meeting.” Another recommendation was to “Send out agendas with times ahead of time so that attendees can be adequately prepared.” (TL 32). Similarly TL 28 stated, “A detailed agenda with specific times for breaks and lunch. Staying on schedule for the ending time.” Some participants asked for the instructions of what they are expected to do in activities to be shared with them in advance so that they can get prepared and have access to those instructions during the training. For example, TL 66 suggested, “Having a presentation that is shared with students where the instructions of what to discuss in the break room are posted. Once we left the main room, it was sometimes hard to remember what the discussion was about.” One participant asked to have an opportunity for rehearsal on technology before the training so that they feel comfortable and are able to follow up with the training. For example, TL 17 she reported “It felt a little disorganized, almost as if it had not been rehearsed prior. I think some practice and collaboration with running through the training would go a long way toward making the experience more seamless.”

Participants’ recommendations that could support or refute the state education agency policy implementations

As stated earlier, prior to COVID-19, the delivery of the AEL PD was mandated by the state agency as a 3-day face-to-face training, and the original version of this training was under another title, Instructional Leadership Development. In 2020, due to COVID-19 restrictions, it was the first time that the state agency allowed it in a virtual format. As explained in the findings’ section, participants in the study were satisfied with the AEL VPD, the coordination of and the technological tools utilized in it. This provided empirical evidence related to participants’ satisfaction of the AEL VPD that supports the policy considerations of the AEL VPD being retained as deemed appropriate by the providers. To this end, we concluded the findings of the study emerged related to policy considerations as follow: (a) participants were satisfied about AEL VPD with the majority of them mostly satisfied, (b) AEL VPD was perceived by participants as easy to attend because it was in a virtual format, given some participants who have family commitments, (c) AEL VPD saved time compared to face-to-face because some participants would have to drive from remote places to the training place, since participants in the Master’s program are from across Texas, (d) AEL VPD, as described in the study, facilitated communications among participants and with the trainers, (e) technology utilized in the AEL VPD was perceived as effective and appropriate for the activities included in the training, (f) Breakout Rooms were perceived as convenient for small group discussions, reflections, and sharing ideas, (g) Chat Box allowed participants to communicate with each other properly, get feedback and assistance through written texts without interrupting presenters or other participants, (h) sticky notes on Jamboard allowed participants to share individual and group thoughts, similar to gallery walks in face-to-face PDs, (i) recording AEL VPD 3-day sessions would allow participants to revisit them when needed, (j) participants stated that if both AEL VPD and face-to-face options are available in the future, they would recommend the AEL VPD option to their colleagues, (k) participants perceived collaboration in a virtual environment with diverse group of educators across Texas and how the Breakout Rooms made this collaboration most effective as their most interesting experience of the AEL VPD they attended, and (l) participants recommended increasing time allocated for activities in the Breakout Rooms, adding more breaks to the AEL VPD schedule and extending time for those breaks to be able to follow up with the AEL VPD, when presented to other participants in the future.

Discussion

In this study, we investigated a unique professional development initiative by a public university in Texas that is to deliver the AEL training as mandated by TEA for principal candidates in a virtual format for the first time. The switch from the face-to-face to the virtual format was a response to the COVID-19 Pandemic closure in 2020 informed by the Texas Governor’s instructions. This sudden shift of the AEL to the virtual format is similar to what Hodges et al. (2020) described in the literature as an ERT. The decision of the virtual format was made in April 2020 by TEA to allow virtual training for a limited period of time due to the pandemic. The virtual option became available at the end of May 2020 (Texas Education Agency [TEA], 2022). Given the idea that it was the first virtual AEL, we wanted to explore the perceptions of the AEL trainees, who were bilingual teachers in the PAL master’s program, related to: (a) their satisfaction with the virtual format of the AEL VPD, (b) the most interesting experience during the virtual AEL VPD, and (c) recommendations related to enhancing the quality of virtual AEL VPD that could support or refute the state education agency’s policy implementation.

The AEL VPD findings actualized two theories used in the study: the multimodal model theory (Picciano, 2017) for online education and the SDL theory for adult learning (Merriam, 2001). With the AEL VPD, the instructors were able to create an online learning community, similar in its quality of instruction and interaction to, if not even better than, the face-to-face learning communities. Certainly, the AEL VPD included the same training content approved by TEA as the face-to-face AEL. Informed by Picciano (2017) online learning community, the AEL VPD succeeded in providing participants with numerous opportunities for dialogue and discussion using technology, as perceived by the participants themselves. Collaboration among participants who, as described earlier principal candidates, was also evident, along with reflection on the learning. Those rich opportunities of interaction and reflection constitute the basis of the multimodal model theory as discussed by Picciano. On the other side, the SDL theory demonstrated how adult learner participants constructed their learning through making connections with their previous knowledge and experiences. They were provided with a virtual learning environment in which they were able to communicate, reflect, and share their opinions on the AEL VPD content and activities in ways that advanced their leadership knowledge and skills.

Participants’ satisfaction with the virtual advancing educational leadership training

Participants in the study demonstrated high levels of satisfaction of the virtual format of the AEL VPD as indicated in the quantitative and qualitative findings. Many of them shared positive perceptions about the AEL VPD related to how it saved them time compared to face-to-face and provided them with opportunities of interaction. This is similar to what we found in the literature (Markson, 2018) about how well-constructed online leadership preparation programs were perceived by participants as more effective than face-to-face preparation. Those are not surprising perceptions from participants in the study given the large size of the State of Texas, where some of the PAL program’s participants would have had to drive for long hours to be able to attend this mandatory training in the local university hosting it.

As for participants’ satisfaction with the coordination of the AEL VDP, it was also clear, as per participants’ perceptions, that the time and efforts invested by the trainers, who are professors from the local university, to ensure delivering a high quality virtual professional development worked well. This is because it was mentioned repeatedly in participants’ comments that the virtual learning environment of the AEL VPD provided them with opportunities for collaboration and interaction with each other as well as simulation that they believed was even better than the face-to-face learning environment. This is also aligned with what we found in the literature related to how Markson (2018) described online principal preparation programs as effective for preparing future school leaders.

Participants were also satisfied with the technological tools used in the AEL VPD. Obviously, using ZOOM to host the AEL virtual training seemed to have been a good choice made by the trainers. This is because participants perceived the technological tools embedded in Zoom such as the Breakout Rooms and Chat Box as appropriate for the AEL VPD. This is aligned with what we found in the literature related to how ZOOM served as an effective virtual portal to teach online courses for adult learners (Barbosa and Barbosa, 2019). Participants also believed that the Jamboard, which is a Google feature, was effective to capture and share their ideas. The only technological tool that did not seem to have been perceived as effective was the White Board. Indeed, participants’ perceptions of the technological tools providing them with opportunities of collaboration and reflection in an online learning community is aligned with the theoretical framework of the study (Merriam, 2001; Picciano, 2017).

Participants were satisfied with coordination and planning for the AEL VPD. In our planning for the AEL activities, we were careful to keep the same group members within the same groups in the extended activities. The reason we did so was to allow group members to pursue their discussions on those activities, and not get interrupted by changing their groups. Participants perceived this helpful as it developed trust to share opinions among members in the small groups, which contributed to advancing effectiveness of the discussions about those extended activities. On the other hand, we also used the randomized group assignment in planning for activities that needed frequent rotations among group members.

Participants believed that meeting more people during the AEL, whether members they knew in their cohort or new members from the other cohort, was an eye opening experience. This is because different people from different geographical areas and school districts across Texas seemed to have shared unique perspectives. This is aligned with (Irby et al., 2020) found regarding how a diverse principal pool can provide a rich learning environment that accommodates the needs of leaders serving in high-needs schools. At the time when participants were satisfied with most of the technological tools utilized in the AEL VPD, they did seem to have been satisfied with the White Board. As described in the findings, Jamboard sticky notes and the White Board were the Gallery on which those groups pinpointed their thoughts and opinions. While those tools were the visual representations of participants’ ideas they were perceived by participants as not equality effective. Jamboard and sticky notes were perceived by the majority of participants as more appropriate for the AEL VPD compared to the White Board. Particularly, participants found Jamboard and sticky notes were more colorful. The Jamboard allowed participants to move sticky notes around and group them similar to what participants would do in the face-to-face VPD with actual sticky notes and a physical board. Participants did not like the White Board very much because it did not allow those levels of interactivity provided by the Jam Board and the sticky notes. This virtual learning environment and the tools utilized to advance interaction among participants are aligned with the MultiModal Model Theory related to how appropriate online portals assist effectively in facilitating learning (Picciano, 2017).

Participants’ most interesting experiences during the advancing educational leadership virtual professional development

The three main themes associated with participants’ most interesting experiences: collaboration, Breakout Roots, and AEL activities and trainers provided evidence that participants found the AEL VPD engaging and beneficial to them. Although the switch from face-to-face to virtual learning environments was all of a sudden due to COVID-19, as described in literature by Hodges et al. (2020) as an ERT, and the AEL was not an exception, participants’ perceived trainers’ good preparation for the AEL VPD worked well for them.

Collaboration among participants specifically in Breakout Rooms was enriched by multiple factors: the high quality activities included in the content of the AEL, the diversity of participants as they were from different geographical areas and districts across Texas, and the relatively small numbers of participants in each of the Breakout Rooms (mostly four to five participants). Those factors enabled participants to build trust with each other and to feel confident in sharing their opinions and professional experiences related to critical leadership situations included in the AEL VPD that they would have to address in the future as school leaders. This was obvious as participants reflected on some of the challenging activities that tested their abilities for decision making. An example of those activities is the rattlesnake in which participants were asked to explain how they would behave in some tough situations that school leaders sometimes have at their schools.

The trainers also played important roles leading activities and facilitating discussions among participants. Their leadership of the AEL VPD was guided by a framework developed from the SDL theory of adult learning (Merriam, 2001). To this end, the trainers purposefully created opportunities for collaboration, reflection, and sharing thoughts and experiences among participants. The SDL theory (Merriam, 2001), which is an integrated part of the theoretical framework of this study, helped in explaining how bilingual teachers in the study, as adult learners, were able to reflect on their previous experiences and make connections to other teachers’ experiences as they brainstormed and reflected together throughout the AEL activities. This contributed to advancing participants’ learning outcomes as they constructed more meaningful and relevant knowledge and skills about educational leadership.

Participants’ recommendations for enhancing the advancing educational leadership virtual professional development

Considering this was the first time for the AEL to be delivered virtually, we expected to receive numerous recommendations about improving the use of technology and ZOOM, but this was not the case. Most of the participants’ recommendations to enhance the AEL VPD when presented again for other participants in the future were mainly related to time management/issues. Since the AEL was offered originally in three face-to-face intensive days, when it moved to a virtual format the same timeframe of 3 days did not change. While attending the AEL in a three face-to-face training format seemed appropriate for participants, they perceived the 3-days virtual training as hard for them. They explained that it was hard for them to spend almost 8 h for three consecutive days in front of their computer screens. Therefore, most of their recommendations to enhance the AEL VPD were focused on increasing the number of breaks in each day and expanding time for those breaks so that they could stretch and to reduce their virtual fatigue.

Based on the feedback obtained from the participants, the Breakout Rooms provided effective collaboration and interactions among participants beyond our expectations. The only recommendations participants shared related to the Breakout Rooms were to increase the time allocated for some activities in those rooms so that everyone could share their opinions. These recommendations were aligned with other recommendations related to considering a few more seconds for the transitions between the main room and the Breakout Rooms. In other words, as per participants, providing more time for activities in the Breakout Rooms and allowing a few seconds for participants to return from those rooms to the main rooms with everyone could be great additions to the AEL VPD.

The other important recommendations were related to sharing the AEL Agenda and materials prior to the AEL as well as providing participants with opportunities to rehearse on technology. We believe sharing AEL Agenda and rehearsing on technology could help participants feel more comfortable related to the flow of the AEL training. However, we do not think that sharing all AEL training materials would be helpful for participants. To elaborate on this, while sending some of the materials, especially the readings and instructions of some activities, prior to the AEL training might help participants to get prepared in advance, some of the activities specifically those designed to test leadership timely decision making such as rattlesnake are intended for participants to provide immediate responses to critical leadership situations. Thus, sharing them prior to the AEL VPD might provide participants with extra time to think about some of the decisions leaders may consider, which is not the goal of those activities. All in all, participants’ recommendations about time are important to be taken into consideration for future AEL VPD.

Implications for practice

The COVID-19 pandemic was a factor that enforced educational leadership to promote emergency changes. The AEL training is a state and a university required training to all principal candidates who pursue a masters’ degree in Educational Administration. The results showed high satisfaction with the virtual AEL training which provides all participants to participate in the AEL training activities. As explained earlier, the newly designed virtual activities were virtual types of the face-to-face AEL training activities. However, the virtual activities seemed to have received higher engagement than the face-to-face. For example, dividing the participants into groups who join virtual breakout rooms, gives a valuable opportunity to introverted participants to voice up and share their professional experiences. In addition, the time allocations of the other activities including but not limited to Chat Box, jamboard, and presentations were more effective in the virtual platforms because in the face-to-face format the move from an activity to another (e.g., round table, lecturing, post it in, etc.) was time consuming. Much time is also consumed when the participants are changing their classroom settings. This time consumption is not an option in the virtual platform.

Since all virtual AEL training is recorded, the knowledge availability represents a major implication for practice. All AEL trainees who attended the virtual training, have access to the recordings of the 3-day training. This opportunity makes the knowledge gained from the training handy, and students can revisit the recordings whenever they want to refresh their knowledge about it. This ability to watch the training videos again was not an option in the face-to-face AEL training.

Implications for policy

Since the time of the study, TEA ruled that the virtual option for the AEL training may be retained as deemed appropriate by the providers; therefore, this study might be the first study published related to this AEL training policy. The results elicited several recommendations in regard to the AEL training delivery. We advocate for the virtual AEL new policy to continue in the future and to be a continued option along with the face-to-face version so that participants may select from between the two versions offered by state agencies or principal preparation program providers. We build this support to the policy consideration based on a number of reasons informed by the findings of the study. Those reasons are as follows.

Advancing educational leadership virtual professional development achieves equity

Based on what the participants shared, we found that they believed that the virtual AEL training saved their time and effort to commute from their homes and cities to go to the designated city in which a training is hosted. More importantly, this virtual AEL training waived the travel expenses. Since our program is fully online, we have students from the entire Texas. In the previous years when the participants were required to attend in person, they had to travel to Texas A&M University campus at College Station city, some students came from El Paso city which is over an 11-h drive away from College Station city.

The participants also have needed to secure and pay for lodging which may have increased the exposure to COVID-19. Thus, the virtual AEL training was the solution to reduce the risk of contracting the COVID-19 infection and to reduce the monetary expenses accompanied with attending the in-person training. This gave all students equal and equitable opportunities to attend the AEL VPD. Thus, with continuing potential for contracting COVID-19, we recommend the AEL training to be continued in the virtual delivery and for the reasons of equity and access, we support the state policy that allows for AEL VPD even after the risk of the COVID-19 pandemic ends.

The convenience of the advancing educational leadership virtual professional development

The participants also shared that the virtual training was convenient, because they have the advantage of attending the training from home while they are being taken care of, or they are taking care of their families. One of the participants was tested COVID positive, and she was under treatment, the AEL virtual delivery enabled her to participate while she was in bed. If the training were in its traditional face-to-face format, such participants would not have been able to participate. With school closures and some public school students quarantined during the time of the study due to COVID-19, participants were among those educators with an increased presence of children at home. This situation may have prevented participants from being able to attend the AEL training if they have to travel to the AEL training facility. Thus, when the training was available virtually, these participants were able to take care of their children while they were engaged in the training.

Because of the convenience for principal candidates to be able to collaborate and participate virtually from home, the policy consideration for AEL is that after this pandemic has subsided, that the AEL VPD continue as an option. The findings from this empirical study can provide policymakers at the state level with added information to support a policy decision for delivering AEL virtually as an option along with the face-to-face option for AEL. This policy consideration is important to advance equity and access for all participants given the fact that participants perceived the virtual AEL format to be effective for them. The advancement of online learning, as demonstrated with ZOOM and the technological tools noted in this study as an example, can help principal preparation faculty to engage, to meet the needs of adult learners in leadership training, and to equip them with leadership knowledge and skills, perhaps equally as well as a face-to-face AEL training.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Texas A&M University-College Station Institutional Review Board (IRB). The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Funding

This study was supported under the grant from the U.S. Department of Education, Project Preparing Academic Leaders (PAL) (Award# T365Z170073), Accelerated Preparation of Leaders for Underserved Schools (A-PLUS) is a SEED grant (Award# 1894-0008).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Advancing Educational Leadership [AEL] (2015). Participant guide (spiral-bound). Region 13 Product Store. Available online at: https://store.esc13.net/products/advancing-educational-leadership-ael-participant-guide?variant=7969879429

Barbosa, T. J., and Barbosa, M. J. (2019). Zoom: An innovative solution for the live-online virtual classroom. HETS Online J. 9, 137–154.

Chaka, C. (2020). Higher education institutions and the use of online instruction and online tools and resources during the COVID-19 outbreak-An online review of selected US and SA’s universities. Durham, CA: Research Square. doi: 10.21203/rs.3.rs-61482/v1

Cope, D. G. (2014). Methods and meanings: Credibility and trustworthiness of qualitative research. Oncol. Nurs. Forum 41, 89–91. doi: 10.1188/14.ONF.89-91

Davies, P. (2000). The relevance of systematic reviews to educational policy and practice. Oxford Rev. Educ. 26, 365–378. doi: 10.1080/713688543

Doyle, L., Brady, A. M., and Byrne, G. (2009). An overview of mixed methods research. J. Res. Nurs. 14, 175–185. doi: 10.1177/1744987108093962