- 1Department of Early Childhood and Junior Education, University of Zimbabwe, Harare, Zimbabwe

- 2Department of Applied Psychology, University of Zimbabwe, Harare, Zimbabwe

- 3Department of Pre-Primary and Early Childhood Education, Kyambogo University, Kampala, Uganda

The majority of young children with a disability live in low- and middle-income countries, where access to inclusive early learning programs supported by governments or non-government organizations is usually unavailable for the majority of the population, who live in rural areas. This study explored the feasibility of leveraging materials and personnel available within local communities to provide inclusive early learning programs in rural Zimbabwe. Caregivers of young children with some disability were given the opportunity to describe their experienced challenges; ways in which they informally support their children’s early learning; and the types of skills and resources they were able and willing to offer to support the establishment and operation of a more formal group-based inclusive early learning program. Qualitative data were generated from a purposive sample of caregivers of children with diverse impairments (n = 12) in two remote rural districts in Zimbabwe. Themes were identified in the rich qualitative data caregivers provided during individual interviews. The challenges caregivers experienced included the failure of interventions to improve their children’s level of functioning, the lack of access to assistive devices, the perception that the local school would be unable to accommodate their children, and worry about the future. Despite these stressors, caregivers actively supported their children’s self-care, social, moral and cognitive development and sought ways to save the funds that would be needed if their children could attend school. Caregivers were also willing and able to provide diverse forms of support for the establishment and operation of an inclusive early education program: food, funding, teaching and learning materials, and free labor. The insights obtained from these data informed the design of local community-controlled inclusive early education programs and the types of support caregivers and children may need to participate fully in these.

Introduction

Disabilities are long-term physical, mental, intellectual, or sensory impairments. They are in interaction with various barriers that may hinder an individual’s ability to participate in society on an equal basis with others (United Nations, 2006). Research estimates that, in 2016, 52.9 million children under 5 years of age were living with hearing loss, vision loss, epilepsy, global intellectual disability, a disorder on the autism spectrum, or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Global Research on Developmental Disabilities Collaborators, 2018). Specifically, about 95% of these children live in low- and middle-income countries (Global Research on Developmental Disabilities Collaborators, 2018). Although these six disabilities had the highest prevalence in South Asia, Africa experienced the largest increase in their prevalence between 1990 and 2016. The number of additional young children living with physical, communication or other disabilities is unknown. However, it is likely that this number is high and shows a similar distribution.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) include disability-inclusive provisions that promote government policies to address the special needs of children with disabilities in order to bridge the inequalities that exist between them and other children (United Nations, 2015). Inclusive education is one strategy that contributes toward SDG 4. Inclusive education initiatives for persons with a disability identify and remove barriers and provide an environment that empowers them to fully participate and achieve within mainstream educational settings [United Nations (UN), 2016]. The universal provision of inclusive education for children with a disability is also a provision of the Convention on the Rights of Children, which states the right to an education for “every human being below the age of 18 years” (United Nations, 1989). In low- and middle-income countries with limited formal “social safety nets” access to inclusive education plays a critical role in the life opportunities of children with a disability, since it often offers the only viable means of avoiding a lifetime of extreme poverty (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 2021a).

While considerable investment has already been made in inclusive primary and secondary education, SDG Target 4.2 promotes inclusive practices in early childhood education. It explicitly mandates countries to “ensure that, by 2030, all girls and boys have [equal] access to quality early childhood development, care and pre-primary education so that they are ready for primary education” (United Nations, 2015). This target reinforces the priority attached to inclusive early education programs in the Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action [United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 1994]. The aim of such programs is to “hold high expectations and intentionally promote participation in all learning and social activities, facilitated by individualized accommodations; and use evidence-based services and supports to foster children’s development (cognitive, language, communication, physical, behavioral, and social–emotional), friendships with peers, and sense of belonging” (Vargas-Baron et al., 2019, p. 21). Inclusive education during early childhood makes a significant contribution to supporting disabled children to attain their full potential and to make social and economic contributions to their communities (Global Research on Developmental Disabilities Collaborators, 2022).

Although low- and middle-income countries regularly report on their progress toward achieving SDG 4.2, there is little systematic data that addresses early education for disabled children. A study of education sector plans in 51 low- and middle-income countries reports that none included disaggregated data on the enrolment of children with disabilities in pre-primary education (Global Partnership for Education, 2018). However, it is clear that many low- and middle-income countries have low ratios of qualified teaching personnel-to-disabled learners, and low-accessible infrastructure and teaching and learning resources, necessary to achieve SDG target 4.2. In addition, progress toward this goal is characterized by within-country inequity factors. In many of these countries, progress toward this target has been achieved only in easy-to-reach urban areas (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 2021b). Many rural communities continue to be both economically disadvantaged and chronically under-served in the education (and health) services needed to support meaningful development among young children with a disability (Donohue and Bornman, 2015; Ashley-Cooper et al., 2019; Taneja-Johansson et al., 2021). However, even when “inclusive” early education is available, children with a disability are often denied full participation due to physical inaccessibility, stigma and discrimination, local cultural beliefs, expectations about diverse functionalities, limited accommodations, and curricula that do not address the needs of children with disabilities (Smythe et al., 2022).

Sub-Saharan Africa is home to the majority of the world’s low- and low-middle-income countries. The most commonly identified disabilities among young children in sub-Saharan Africa are those that are readily observable: visual, hearing, physical and intellectual impairments and multiple disabilities (Riggall and Croft, 2016). There is generally low recognition of other disabilities that affect children’s capacity to learn (Riggall and Croft, 2016). Between 1990 and 2016, sub-Saharan Africa has achieved a decrease in the prevalence of disability among young children. Despite this, population increases led to an estimated 71.3% increase in the number of children living with the six types of disability; global hearing loss, vision loss, epilepsy, global intellectual disability, a disorder on the autism spectrum, or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (Global Research on Developmental Disabilities Collaborators, 2018). This increase has not been matched by a parallel increase in access to inclusive early childhood education programs. Indeed, during the last decade, sub-Saharan Africa was one world region that made the least progress in expanding attendance at formal early childhood education services (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 2021b). It appears unlikely that many African countries will soon have the resources to remedy this situation in the foreseeable future.

One strategy to bridge this gap between supply and demand of resources is to draw on, and enhance, the resources of the children’s families and local communities to create informal inclusive early education programs (Smythe et al., 2022). One approach is to supplement the use of existing rich cultural traditions and caregiver knowledge with support to improve caregivers’ effectiveness in scaffolding the development of school readiness skills. Such programs have already been established in some low-and middle-income countries in other regions of the world (World Bank Group, 2017). One of the best-known is the Educa a tu hijo (Educate your child) program in Cuba in which caregivers serve as home-based early educators with the support of a multi-disciplinary team of promoters, trainers, educators, health personnel, volunteers, and community groups (Tinajero, 2010; World Bank Group, 2017). The program capitalizes on the collectivist nature of the local culture and reinforces the belief that the early development of children is a shared responsibility of their families and the wider community—a concept of Ubuntu in Africa. The program currently provides an early education to over 5,000 children with a disability [United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 2021a]. When the program was established in 1983, its goal was to address the absence of early childhood centers in mountainous and rural areas of Cuba. However, the program now also provides non-institutional preschool education in urban areas.

Although many parenting programs have been implemented in Africa (Ward et al., 2020; Luoto et al., 2021), few have shared this approach. One exception is the Inclusive Home-based Early Learning Project (IHELP) (Ejuu and Opiyo, 2022). This model has several distinctive features. First, children’s families and communities lead the program. This fosters a sense of ownership and belonging and ensures that the activities are appropriate for the local culture and context, and align with the interests and abilities of the participating children. Second, although it is a group-based program, it is not institution-based. Instead, families with young children with and without disability gather in a nearby family home or communal space. Third, costs are kept at a minimum by drawing on the resources like home-made toys, food and skills. Skills may include singing and telling stories of caregivers and volunteers from the wider community. The skills are enhanced by support from multi-disciplinary team of educators, health personal and disability specialists. Fourth, the concept of “Ubuntu,” which underlies many African cultural traditions, guides all aspects of the program. Although it is commonly translated as “I am because we are…,” the Ubuntu philosophy is a multifaceted concept that has no equivalent in English. It refers to an ethical social system that values interdependence, reconciliation, and harmony in community relationships, individual and group actions that prioritize the improvement of the well-being of others, and the unity between the physical and spiritual worlds (Ewuoso and Hall, 2019). In IHELP, Ubuntu is reflected through the leadership roles granted to caregivers; the assumption that other community members will feel a responsibility to support young children’s development; the focus on group-based forms of learning; of scarce resources; and the respect shown to the children from low socio-economic backgrounds living with some form of disability. The program builds on previous applications of Ubuntu to early childhood (Boukary, 2018); and primary education in Africa (Chikovore et al., 2012); including in Zimbabwe (Mutanga, 2022). Such initiatives are part of a movement that seeks to ensure that early childhood education programs are underpinned by Afrocentric principles that align with, and capitalize on, children’s rich sociocultural environments (Nsamenang, 2008; Nsamenang et al., 2012; Serpell and Nsamenang, 2014).

Zimbabwe provides a valuable context for understanding the challenges that African rural families face when raising children with disabilities, as well as the feasibility of inclusive early childhood education programs that rely on the active involvement of caregivers. Zimbabwe is similar to many other countries in Africa in four respects: First, it is a party to several international human rights instruments, that guarantee the rights of children with disabilities. These include the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, and the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (United Nations Partnership on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, Zimbabwe, 2021). These instruments guarantee the right to an education. In addition, the rights of persons with a disability (including children) are safeguarded in the Zimbabwean Constitution (Government of Zimbabwe, 2013, Section 83) and the Government of Zimbabwe (2021). However, the constitution also limits the government’s responsibility to provide services to people with disability, to those within the limits of the resources available to it (Government of Zimbabwe, 2013, Amendment No 20, p. 32; Mpofu and Molosiwa, 2017). Second, Zimbabwe has established a program of formal early childhood education and is currently in the process to expand this to respond to SDG 4.2. The Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education (MoPSE) in Zimbabwe provides curricula for 2 years of early childhood education for children aged 4–5 years. Third, there is a significant gap between the policies created to support inclusive early childhood education and their effective implementation. The Ministry’s website acknowledges that most eligible children currently do not have smooth access to early education programs, something especially true in rural areas and particularly for children with disabilities, and that the quality of many programs is low. The website states that there is “inequitable provision for children from rural areas and that vulnerable households most affected; inadequate participation of children with disabilities and insufficient quality of services. Other constraints include the unaffordability and shortage of facilities as barriers to education access and equity while quality of the program is affected by teacher quality, lack of a systematic teacher supervision and support and shortage of teaching and learning materials including inclusive instructional resources” (Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education, Zimbabwe, 2023). Finally, incompatible traditional and contemporary human rights perspectives on disability co-exist in Zimbabwean communities. There continues to be a widespread belief that disability is caused by supernatural forces, such as avenging spirits, witchcraft, or punishment from God or the ancestors (Mukushi et al., 2019; Nkomo et al., 2020). When disabilities are present from birth, mothers are often held responsible (Nkomo et al., 2020), possibly due to the belief that the disability is a punishment for infidelity (Dube et al., 2021). These notions of spiritual or moral “contamination” are often linked with stigma toward children with disabilities and their families (van der Mark and Verrest, 2014), which can contribute to a break-down in communal support (van der Mark and Verrest, 2014; Mukushi et al., 2019) that leaves many parents feeling overwhelmed by their caregiving role and experiencing clinical distress (Dambi et al., 2015).

Research on inclusive early childhood education in Zimbabwe has focused on teachers’ perspectives and preparation (Majoko, 2016, 2017a,b) and the perspectives of parents of children on the autism spectrum who have children who are enrolled in an urban early education program (Majoko, 2019). However, there are currently few insights into the challenges that caregivers of disabled children in rural Zimbabwe experience. There is also little information about the types of informal support for early childhood education these caregivers provide, and the types of support they would be willing and are able to provide to secure improved opportunities for early education for their children.

This current study sought to address this gap by answering three research questions concerning rural caregivers of young children with a disability:

1. What challenges do caregivers face in supporting their children’s early learning?

2. What types of support for early learning are the caregivers currently providing?

3. What types of support would they be willing and able to provide to allow their child to participate in a community-controlled group-based inclusive early education program?

Methodology and methods

Research design and study sites

To capture caregivers’ experiences expressed in their own words and contexts, the study, guided by the interpretivist research paradigm generated rich qualitative data through open-ended and semi-structured interviews. This qualitative research design used two study sites in rural districts of Masvingo Province, in the South-East of Zimbabwe that borders with Mozambique. Both school districts identified experience high levels of children from low-socio economic status seeking education opportunities (Bikita: 68.8%; Zaka: 59.5%) and food insecurity. For examples Bikita experiences 36.8% and Zaka has 28.1% levels of children from low socio-economic status coupled with experiences of some forms of disability (Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT) and UNICEF, 2019). Children in low-socio economic households in Masvingo province have an elevated prevalence of disability (Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT) and UNICEF, 2019). Both Bikita and Zaka districts are underserved in terms of education provision, health and other critical forms of infrastructure.

Research participants

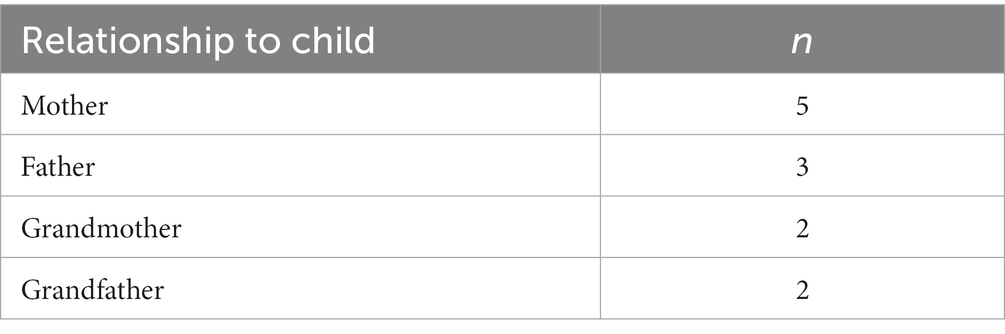

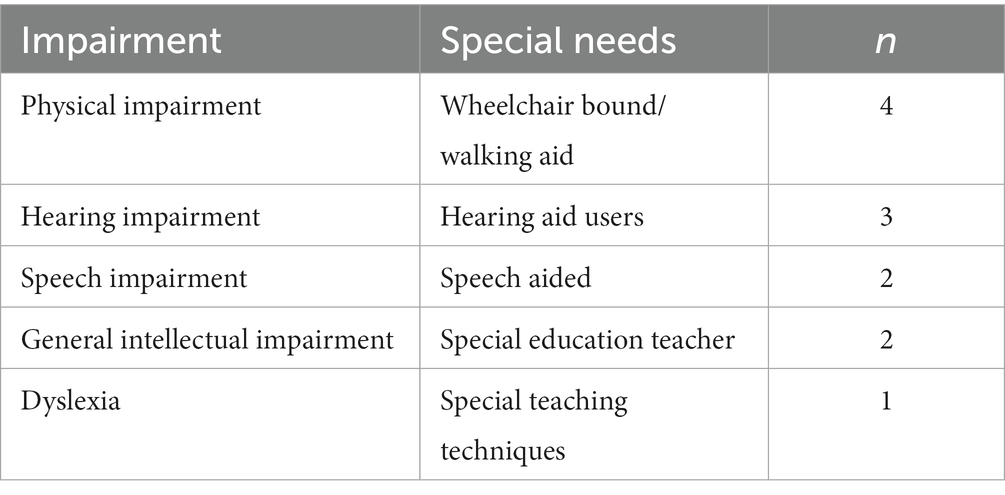

The sample was purposively selected to capture the diversity of primary caregivers of young children with a disability, who were not attending primary school (Zaka, n = 7; Bikita, n = 5) as shown in Table 1. Table 2 shows the diversity of disabilities commonly observed in rural Zimbabwe. All participating caregivers invited in to participate in the study voluntarily agreed.

Table 2. Disabilities experienced by young children in rural Zimbabwe whose primary caregiver participated in the current study (n = 12).

Data generation strategies

Parents reported children’s disabilities and special needs because official records are often unavailable. A review of literature from 21 countries in East and Southern African revealed that formal identification and screening systems were rare, and that parents usually informed the school staff about the disability of their children (Riggall and Croft, 2016).

The researchers conducted individual semi-structured interviews in the participants’ homes with their consent to participate. Information generated involved responding to questions regarding the possibility of inclusive early childhood education provision in a group home-based program. The researchers briefly described the nature of the program to the participants. Two open-ended questions guided the discussion during interviews including: “In the absence of pre-primary education, how would you support your child so that they become ready for primary school”; and “What are you willing to offer to support your child learn better in the inclusive home-based learning centre?” Previous experience suggested that no question would explicitly be asked about challenges was necessary to prompt caregivers to discuss these. Follow-up verbal probes were used at appropriate times of the interview to seek clarification or encourage participants to provide full descriptions (Noble and Heale, 2019). On average, interviews lasted for 25–30 min each. Interviews were terminated when data provided revealed saturation. Interviews were conducted in the participants’ native language (Shona).

Data analysis

The recorded interviews were transcribed and coded in Shona before translating them into English for publication purposes. All members of the research team were fluent in English and Shona. An iterative inductive analysis process allowed for the identification of themes that made sense of caregivers’ shared, their meanings and experiences. An iterative process of assigning codes to responses allowed broad themes to be identified (Braun and Clarke, 2012).

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval for this research was obtained from the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe (Approval MRCZ/A/2732). Permission to conduct this study was obtained from the MoPSE in Harare, and the Provincial Education Director for Masvingo Province. Councilors of the wards that hosted the study sites and village heads were informed about the research and they gave permissions. In addition, members of the research team introduced themselves and the goals of the research to members of the communities before the research commenced. Before, during and after interviews, the researchers reminded caregivers of their rights to freely withdraw from participation without any prejudice.

Findings of the study

Challenges faced by caregivers of young children with a disability

Caregivers had a strong desire for their children to receive a formal education, but they experienced many obstacles. Their attempts to overcome these revealed the co-existence of spiritual, biological, and contextual understandings of disability (World Health Organization, 2021). Even though the improvements caregivers sought would have benefited many aspects of their children’s lives, they explicitly linked their efforts to increasing their children’s chances of attending primary school.

Disability as a barrier to accessing local schools

In the absence of accessible transport, infrastructure, and appropriately trained and resourced school staff, most caregivers perceived that their children’s disabilities were an insurmountable barrier to their children’s attendance at local schools. Many caregivers believed that school attendance would only be possible if the child’s impairment could be “cured.”

Caregivers generally felt that access spiritual “cure” would be a panacea to the problem through their churches. Depending on their faith tradition, they agreed that seeking for healing power of prophets or pastors was key to the problem of disability.

I tried to approach prophets so that the child can be healed and be able to walk on his own. I wanted him to become mobile and be able to walk to school just like [all] other children, but all was in vain. (Grandfather of a boy with a physical impairment)

My pastors at church tried to pray for her, so that the disability can go away. We would fast and pray to God, but it did not help. I thought if she would be healed, she would be able to go to school. Otherwise, for now, nothing has worked for us. (Father)

However, caregivers also sought cures from diverse health professionals:

We approached doctors and physiotherapists to help treat our child. We wanted the deformities to be treated so that he would attend school like his peers, but all those efforts were not successful. (Father of a boy with a physical impairment)

From the interviews, one observation that we made was that none of the caregivers reported some improvement in the child’s condition as a result of the spiritual or medical interventions that they sought.

Education in “special schools” is inaccessible

Participating caregivers commonly coincided and agreed on the view that one option for their children to access education services would be to enroll them in organizations or institutions that specifically supported children with disabilities. These specialist institutions in Zimbabwe, as in many other low- and middle-income countries, are not readily available, and when available, they are particularly challenging for families in rural areas to financially access them. The participating caregivers coincided and reported difficulty in accessing education services through these institutions. The following citation from one caregiver confirms and summarizes this general observation.

We went with the child to organisations that help children with disabilities so that she could get food and assistive devices and be able to learn like others. Those organisations had also promised us that they could place her at institutions for children with disabilities, but nothing came out of it. (Grandparents of a girl with a physical disability)

Essential assistive devices and technologies are inaccessible

Caregivers recognized that their children’s opportunities were often hindered by non-availability of physical accommodation rather than their impairment. However, caregivers of children with a physical or sensory impairment had exhausted all possible options for obtaining the assistive devices that could enable their children to attend school and learn effectively. For example, a grandmother from Zaka reported that despite repeated attempts, she was unable to register her physically disabled granddaughter to receive a wheelchair.

Wheelchair, please. Wheelchair is the only missing item here otherwise I do not see anything more important than that. I have gone everywhere. What they tell us are promises. Nothing comes. Even going to school without the wheelchair will not be possible? How does that happen? I cannot carry her these days. I am old as you can see.

Similarly, a mother of a girl with a hearing impairment experienced a similar predicament when the hearing aid that she had been promised was not made available. For her, the hearing aid was the only challenge between her child and access to specialized education.

Every day I get more worried that my child is growing and will soon be expected to go to school. But how? She cannot hear properly. We have taken her to the clinic. They have not given her the [hearing] aid they told us years ago. She is now 7 years old. Her twin is now in Grade 2. If only we could get [a hearing] aid.

The broken promises from suppliers of materials made to caregivers by well-wishers including government and non-government organizations appeared to raised false hopes and exacerbated the caregivers’ distress.

Despair

Some of the caregivers expressed feelings of despair and abandonment.

What can I do with such a child? She cannot do anything. Myself and her grandfather cannot carry her to school, we are too old and frail. Her parents divorced after her birth. Her mother, who is my [daughter] child, is deceased now, while her father just disappeared. (Grandmother of a boy with a physical impairment)

This child of mine was born with disabilities. He cannot do anything. His father divorced me, saying the child was not his. His twin brother who has no disabilities is now in Grade 2. This child just stays at home. There is nothing I can do…. (Mother of a boy with a physical impairment)

In both cases, the children were born with their impairment. Their biological parents subsequently divorced and the biological fathers abandoned the family citing a variety of reasons. One of the fathers’ claimed that the disabled child was “not his” is consistent with a spiritual understanding of disability in which a child’s impairment is perceived to be a punishment for the mothers’ infidelity. However, before the child was born, there were suspicions. This arose only when the child was born and disabilities were observed. This perception appears ran across the participants. For example, in the case of the twins, it persisted even though one twin was not disabled. In the current sample, no mothers were reported to have abandoned their disabled children.

Informal support for early child development provided by caregivers

Even though many caregivers could not envision a path that would allow their child to attend school, they supported the development self-help, social, and cognitive skills that might make this possible.

Self-care skills

Caregivers believed that for their children, the ability to accomplish self-care tasks such as eating, dressing, and going to use the toilet without assistance would provide their children with independence both at home, and increase their chances of attending school.

Who will be waiting to feed my child at school? These days I make sure that I make her eat from the plate alone [on her own]. Maybe that will be easy. She goes to school where there are others who can self-feed easily. (Mother of a girl with a hearing impairment)

You know what? I am not sure how my child will be able to join school when he has not been able to tie shoelaces and to put on clothes on his own, at least put on a shirt. We have to do it for him here at home, but it will be different at school. We are trying to train him to do it [before going to school]. (Father of a boy with a physical impairment)

Because I do not know when she will be going to school as she is not able to walk [on her own], I am very busy trying to train her to use the toilet on her own. Umm… I am even afraid that she may not like school because of that embarrassment from others. (Mother of a girl with a physical impairment)

Generally, the caregivers agree and accept that self-care skills are critical and that they have the capacity to reduce caregivers’ burden, by liberating time for them to do other things like the household chores. The child will also be motivated to feel that they are self-responsible.

My wish is to see my grandchild do things for herself. She is old enough such that I cannot continue to bathe her and feed her. However, what do I do? She cannot sit, even touch or hold a cup. Her hands and fingers cannot [move]. So, I concentrate on teaching her to be able to do that on her own. (Grandmother of a girl with a physical impairment)

The simple motor skills work and go far beyond playing for purposes of education. The caregivers’ efforts of building on their children’s basic movements and mother-skills is part of what they need to learn. The disabled children apply these skills to accomplish everyday tasks that include feeding themselves, getting dressed, brushing and achieving school activities writing. Caregivers’ comments often reflected a fear that no one at the school would have the role of assisting their child if they went and dropped their children at school. Besides, their children might be ridiculed due to their inabilities to complete everyday self-care tasks and perform “simple” motor-skills.

Social, moral, and cognitive development

Most caregivers valued the importance on teaching their children some social skills and ensuring they exhibited acceptable social and moral standards. The participating caregivers felt that these skills were necessary preparation for participating in school. They wanted their children to be recognized as valuable members of their communities as children who adhered to social norms, irrespective of their disabilities. The caregivers confirmed this thesis:

The moment we stop teaching these children good manners, eish… and say “they are disabled,” then we are also lost. …They are just like any other children. They should be taught good manners. Otherwise, ummm, it will be a problem at school. (Grandfather)

I was shocked to hear my grandson scold other children at the shops one day. Even if he was wronged, it was not correct. But the children were calling him all sorts of names because he is [mentally] disabled. True, we have to teach the children, all of them, how to relate well with each other. They are all people and need to learn together at school. (Grandmother of a boy with an intellectual disability)

Caregivers also identified specific social behaviors that they wished to discourage in their children. Some of these were unique to the individual participants and their disabilities. Shared social behaviors generally affect how people around the child react and respond to the situation created by the behaviors, but they also affect decisions that will be made by all those involved in the context. Participants agreed that the results are dependent on the type of the society the disabled child belongs hence, it is very critical to ensure their children are able to create social environments that are conducive to earn support from the people around then especially other children. For example:

I have since noticed that the disabled children want to be sympathized with for no good reason. (Grandfather)

Other caregivers perceived that school presented special challenges to moral and social behavior that could be resisted with appropriate prior learning:

As a parent, I have to make sure that the child is morally upright, you know…. Oh yes. If the girls and boys are left alone to behave the way they want, we will be surprised because they can easily lose their heads and misbehave when they go to school where there will be other children. (Father of a child with a speech impediment)

The ways in which parents sought to develop their children’s skills often reflected a strengths-based approach to learning:

I would really, really want my child to have a lot of things to play with, I mean toys that he would be using to make sure that the ears that do not hear properly are helped by the eyes, nose, hands and other parts. That is all my child needs, so I will make sure to look for the money to buy some playthings. (Father of a boy with a hearing impairment)

Planning for their children’s school attendance

Even though many caregivers could not see a viable way for their children to attend primary school, they continued to actively prepare for this possibility. In Zimbabwe, school attendance requires a school uniform, supply of other learning media and the payment of school fees, so much of this preparation focused on saving enough money to cover these costs. Meanwhile, money is hard to come-by in Zimbabwe.

Whatever the case, no matter how hard it is to find the money, I can tell you I will sacrifice to buy my child a uniform to make sure that there is something ready for use when school starts. It is a pity that this year is a year of drought. There are fewer extra tasks to do at people’s homes [to earn money to help my child]. Everyone is looking for money to buy food and there is nothing to spare for other things. (Mother)

The first thing that I will do is to pay fees for my child. At least for the time being I can save that money as it comes my way. I do not care how I get the money, but what I know is that I will keep something out of it for fees. (Mother)

In summary, many of the obstacles caregivers faced to support their children to gain access to education is easily traced back to their low-economic status and the lack of services in their remote rural area. Poverty made them dependent on government and non-government agencies or well-wishers for assistive devices, and limited their ability to save enough money to allow their children to attend school. The participating caregivers reported experiencing high levels of frustration in addition to despair. Despite these experiences, all caregivers actively attempted to support the development of school readiness skills, and many were willing to make significant personal sacrifices to keep alive the hope and possibility of their child attending school.

Caregiver support for a home-based inclusive early learning program

Caregivers welcomed the opportunity to access a local inclusive early learning program for their disabled child:

If it were possible for children to learn at home, right here in the village, we will be very happy. (Grandfather)

Despite their very limited resources and the many care and livelihood demands on their time, caregivers reported that they were willing and able to offer both time and material support for the establishment and operation of an early learning program for their children. Children’s early years learning experiences define the quality how they think and socialize are critical for the children’s optimum development and the skills that they will need to participate in Early Childhood Education.

Food

The females generally revealed and discussed the importance of recommended nutrition for children and offered to provide food for the meals the children would need while they were attending the early learning program:

If my child gets an opportunity to learn closer to home and with others, I would be happy to bring mealie meal and can give them vegetables so that there is material from which to prepare food. We just need to grind the maize and we have something for the children to eat as they play and learn. (Mother of a child with a hearing impairment)

My child needs to learn on a full stomach and so I need to make sure that there is always food for the child to eat both at home and at school. Like in the autumn season we are able to bring green mealies and tomatoes and beans that we have grown in the fields and gardens at our homes. (Mother of a child with dyslexia)

Food is very important. I have to support my child. Yes I will bring from home to the centre some light food such as locally available fruits such as monkey apples to the centre. My child loves them and they are found close to home. Just at the nearby hill there are plenty of these fruits that grow since this area is dry. Tomatoes are also growing this side. These we shall bring for soup preparation. (Mother of a child with an intellectual impairment)

The foods the mothers offered to supply were those that could be found or grown in the local environment.

Money

Financial support for learners in early childhood care and education is needed for covering total costs of the desired quality of early child care and related education services. Therefore, financial support is required and is charged by the school for the child’s participation in the early learning programs. Regardless of there are givers expressed motivation to find the means to cover the costs, even though there were financial implications for some cases.

The very first thing that I will do is to pay school fees even if I am not formally employed. I will do anything, even doing piece jobs in people’s fields so that I have money to pay fees for my child. (Mother of a child with a speech impediment)

I have since been chucked out of the job that I used to do but that does not matter. I will still pay fees for my child because that’s the only support that I can offer to guarantee learning at the centre. (Recently retrenched father of a child with hearing and speech impairments)

Teaching and learning materials

Caregivers understood and valued the importance of materials required to engage the children’s interest and promote learning. Caregivers with the means to provide support indicated that they would offer to donate learning and play materials to achieve quality learning for their children. For example, one parent summarized the general view of the parents this way:

Of course, I will keep school fees and money to buy uniforms and books and some other items that the child will need like crayons, toys and balls. You know what, my child likes to write things and paint, so would be happy to support that. (Grandfather of a boy with a physical impairment)

Other caregivers indicated that they offered to provide toys and chairs. In some cases, these resources would be homemade.

Labor

Caregivers also offered to perform a diverse range of tasks to establish and support the ongoing operation of an inclusive early learning program. Some of the offers were for ongoing tasks, such as maintaining the play area, and ensuring that the children had access to clean drinking water and sanitation facilities. They perceived these contributions has having potential to minimize recurrent operating costs and ensure the safety of their children.

I will be available to come and cut grass at the centre because children need space to move around freely since, [for example, my daughter] … has challenges with that. I want her to learn without fear of any harmful elements that can emerge from the tall grass. (Mother of a daughter with a physical impairment)

Other parents offered to provide labor for the construction of play facilities:

I want my child to learn many sporting activities, so I will make sure that I help to make some sports facilities. If I put up a jump pit filled with sand, ya-aa the children will be happy to learn how to use their bodies. (Father of a child with a physical impairment)

Other aspects that the caregivers could also use to enrich the support they give to (children) learners would be to volunteer to produce their rich cultural knowledge of songs, stories, dances, and games that might be a valuable resource for the early learning program. In general, and from a practical perspective, cultural knowledge empowers learners/children to identify and to go further and discover ways of learning. They will also use language and even use the cultural norms to communicate in respectful with others. When parents share these forms of knowing, it helps to promote the historical awareness in them. This way, learners will be able to learn about their individual identities and it encourages them to be inquisitive, creative, thus benefiting them in their entire lives.

The school curriculum

Although neither of the prompt questions asked about caregivers’ priorities for their children’s learning, several caregivers discussed the concept. It would be important to note that the caregivers did not emphasized pre-literacy or pre-numeracy skills. Instead, they demonstrated concerned about their children’s holistic development and discipline:

I personally do not care about reading and writing for my child, not because of his disability, but because those academic competences do not make the child who they should be as a Shona person. I want a straightforward child. (Father)

For me, I will be very much willing to come to the centre to help teach my child and others about being a good person. (Grandfather)

If we relax and just think that the children will just grow by themselves, then we will be lost because they will go into the forest and lose their heads in the jungle. They will be like animals without any social limits. They can do anything in broad daylight. I mean animals. Have you seen donkeys and cattle in the pastures. That’s what our children will be like. Let us all teach them. They are our children together. (Father of a son with a hearing impairment)

These caregivers’ priorities are consistent with the centrality of the hunhu/ubuntu concept in the local cultural context. In the current sample, only male caregivers made comments about the curriculum in the early learning program.

Concerns

One caregiver was concerned about the attitude and behaviors of people who came into contact with her disabled child while they were participating in the early learning program. Caregivers were sensitive not only to situations that posed a physical safety risk, but also to those that could pose a psychosocial risk:

I do not want visitors who come to ask too many questions about my child’s condition because it disturbs. (Mother of a child with a physical impairment)

Discussion

This study allowed caregivers to describe, in their own words, their lived experiences with challenges they encountered while raising children with diverse disabilities in rural Zimbabwe; the informal support for early learning they provided; and the types of supports they were willing and able to provide to facilitate their children’s access to a more formal inclusive early learning program. The data revealed that caregivers indicated a high commitment to support their children’s development. They demonstrated future-orientation to promoting the development of self-care, social, moral and cognitive skills they believed their children would need to have an opportunity to attend primary school. They also sought to provide financial supports to ensure this. However, data generated revealed high levels of frustration, because of the absence of the types and quality of supports from government agencies and non-governmental organizations that would allow their children to achieve their potential to support their children. In the absence of these supports, and being unsure whether their children would be able to receive an education, caregivers were concerned about what the future held for their children, including being overwhelmed by the burden of care and a sense of hopelessness about the future for their children. In this context, caregivers welcomed the possibility that their children could participate in a more formal early learning program, and they desire to provide wide ranges of material resources and labor to facilitate the establishment and ongoing operation of such a program.

The resourcefulness and commitment exhibited by the participating caregivers are valuable resources that can be deployed to support their children’s early learning. However, it seems likely that they would benefit from a wide range of strategies to scaffold the development of their children’s skills (Smythe et al., 2022). For example, caregivers in the current study may not capitalize on their rich cultural knowledge because they do not perceive the diverse ways in which this can support the quality of their children’s early learning (Serpell and Nsamenang, 2014). Caregivers may be most effective as teaching partners if interventions also seek to improve caregivers’ wellbeing, livelihood strategies, and confidence (Smythe et al., 2022).

From the data generated, the application of the Ubuntu philosophy to the context of disability is complex and requires unpacking. Three male caregivers perceived the development of children’s acceptable character should be a focus of the inclusive early childhood curriculum. This is consistent with the concept of Ubuntu/hunhu. However, none of the caregivers received significant support from other members of their communities were two fathers had abandoned their families after the birth of a disabled child. Peers at school need help understanding disability to reduce their ridiculing those with disabilities. One reason for not sending disabled children to schools relates to fear of people unfamiliar with their children’s disability and might ask uncomfortable questions. This complexity does not appear to be unique to rural Zimbabwe, since stigma and social exclusion have been reported by caregivers of young children with a disability in urban settings in Zimbabwe (Rugoho and Maphosa, 2016), and in nearby African countries in which Ubuntu is also a core cultural concept. In Kenya, for example, Gona et al. (2011) reported such experiences. Similar experiences were also reported in Malawi, for instance, Masulani-Mwale et al. (2016), to use just a few examples. These findings do not detract from the value of organizing early learning programs using the Ubuntu philosophy, or designing a curriculum that seeks to promote child behaviors and attitudes that are consistent with Ubuntu. However, acknowledging that reality may deviate from the Ubuntu ideal. One element in the IHELP model that responds to this is the bringing together of caregivers for mutual support. This needs to be carefully planned. Research suggests that self-help groups for African caregivers of disabled children foster mutual support only under very specific conditions (Bunning et al., 2020; Tekola et al., 2020; Mkabile et al., 2021).

The current study had several limitations that should be considered when the results are interpreted. The number of disabilities experienced by children as reported by caregivers required that each be addressed in its entirety to understand how solutions should be achieved based on the uniqueness. There is need to look at one case study for each, or to group the different cases for each context. Generally, the study provided pointers but the solutions could be insufficient. The results of this study might have produced diverse insights if the study had focused on caregivers of children with and without disabilities.

Conclusion

Past research has demonstrated that inclusive early education programs can lead to significant improvements in the quality of life for both caregivers and their children (Majoko, 2019). The current research suggests that local material and labor resources could be harnessed to provide such programs even in poor rural communities. Nevertheless, the progress that can be achieved by such programs, and from interventions that provide support and training to caregivers, are likely to be limited if the shortfall in foundational infrastructure and human resources is not addressed. For example, the benefits from an early learning program are likely to be enhanced if children with a hearing impairment are provided with a hearing aid and children with gross motor impairments are provided with a wheelchair or similar aid. In addition, the benefits of preparing children to attend school are easily undermined if schools are not prepared to receive them due to inaccessible infrastructure and learning resources and/or a lack of appropriately trained and supported teaching staff who hold positive attitudes to inclusive education (Mangwaya et al., 2016; Majoko, 2017b).

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

This study involving human participants was reviewed and approved by the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe, under the Research Council of Zimbabwe. The participants provided their written informed consent.

Author contributions

JT conceptualized and wrote the study topic, reviewed literature, designed the study, collected the data, and wrote the first and reviewed manuscripts. SM conceptualized and reviewed the study topic and design, reviewed literature, collected the data, and edited and contributed to the first and reviewed drafts of the manuscript. GE designed the study, reviewed article content, and approved the submitted version. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Data collection and literature search for this manuscript were made possible with funding from the IDRC grant 109666-001 to Kyambogo University which the authors accessed from the University of Zimbabwe as a sub grant awardee.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Ashley-Cooper, M., Van Niekerk, L.-J., and Atmore, E. (2019). “Early childhood development in South Africa: Inequality and opportunity” in South African schooling: The enigma of inequality: A study of the present situation and future possibilities. eds. N. Spaull and J. D. Jansen (Cham: Springer), 87–108.

Boukary, H. (2018). “Putting the cart before the horse? Early childhood care and education (ECCE) the quest for Ubuntu educational foundation in Africa” in Re-visioning education in Africa: Ubuntu-inspired education for humanity. eds. E. J. Takyi-Amoako and N. T. Assié-Lumumba (Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan), 135–153.

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2012). “Thematic analysis” in APA handbook of research methods in psychology. eds. H. E. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. E. Rindskopf, and K. J. Sher, Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological, vol. 2 (Washington, DC: American Psychological Association), 57–71.

Bunning, K., Gona, J. K., Newton, C. R., Andrews, F., Blazey, C., Ruddock, H., et al. (2020). Empowering self-help groups for caregivers of children with disabilities in Kilifi, Kenya: Impacts and their underlying mechanisms. PLoS One 15:e0229851. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229851

Chikovore, J., Makusha, T., Muzvidziwa, I., and Richter, L. (2012). Children’s learning in the diverse sociocultural context of South Africa. Child. Educ. 88, 304–308. doi: 10.1080/00094056.2012.718244

Dambi, J. M., Mlambo, T., and Jelsma, J. (2015). Caring for a child with cerebral palsy: The experience of Zimbabwean mothers. Afr. J. Disabil. 4, 1–10. doi: 10.4102/ajod.v4i1.168

Donohue, D. K., and Bornman, J. (2015). South African teachers’ attitudes toward the inclusion of learners with different abilities in mainstream classrooms. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 62, 42–59. doi: 10.1080/1034912X.2014.985638

Dube, T., Ncube, S. B., Mapuvire, C. C., Ndlovu, S., Ncube, C., and Mlotshwa, S. (2021). Interventions to reduce the exclusion of children with disabilities from education: A Zimbabwean perspective from the field. Cogent Soc. Sci. 7:1913848. doi: 10.1080/23311886.2021.1913848

Ejuu, G., and Opiyo, R. A. (2022). Nurturing Ubuntu, the African form of human flourishing through inclusive home based early childhood education. Front. Educ. 7:838770. doi: 10.3389/feduc

Ewuoso, C., and Hall, S. (2019). Core aspects of Ubuntu: A systematic review. South Afr. J. Bioeth. Law 12, 93–103. doi: 10.7196/SAJBL.2019.v12i2.679

Global Partnership for Education. (2018). Disability and inclusive education; a stock take of education sector plans and GPE-funded grants. GPE working paper 3. Washington, DC: Global Partnership for Education

Global Research on Developmental Disabilities Collaborators (2018). Developmental disabilities among children younger than 5 years in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Glob. Health 6, e1100–e1121. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30309-7

Global Research on Developmental Disabilities Collaborators (2022). Accelerating progress on early childhood development for children under 5 years with disabilities by 2030. Lancet Glob. Health 10, e438–e444.

Gona, J. K., Mung’ala-Odera, V., Newton, C. R., and Hartley, S. (2011). Caring for children with disabilities in Kilifi, Kenya: What is the carer’s experience? Child Care Health Dev. 37, 175–183. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2010.01124.x

Government of Zimbabwe (2013). Constitution of Zimbabwe amendment (No. 20) Act 2013. Harare: Fidelity Printers and Refiners

Government of Zimbabwe (2021). National Disability Policy, Zimbabwe. Harare: Government of Zimbabwe. Available from: www.veritaszim.net

Luoto, J. E., Lopez Garcia, I., Aboud, F. E., Singla, D. R., Zhu, R., Otieno, R., et al. (2021). An implementation evaluation of a group-based parenting intervention to promote early childhood development in rural Kenya. Front. Public Health 9:653106. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.653106

Majoko, T. (2016). Inclusion in early childhood education: Pre-service teachers voices. Early Child Dev. Care 186, 1859–1872. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2015.1137000

Majoko, T. (2017a). Inclusion in early childhood education: A Zimbabwean perspective. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 21, 1210–1227. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2017.1335354

Majoko, T. (2017b). Mainstream early childhood education teacher preparation for inclusion in Zimbabwe. Early Child Dev. Care 187, 1649–1665. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2016.1180292

Majoko, T. (2019). Inclusion of children with autism spectrum disorder in mainstream early childhood development: Zimbabwean parent perspectives. Early Child Dev. Care 189, 909–925. doi: 10.1080/03004430.2017.1350176

Mangwaya, E., Blignaut, S., and Pillay, S. K. (2016). The readiness of schools in Zimbabwe for the implementation of early childhood education. S. Afr. J. Educ. 36, 1–8. doi: 10.15700/saje.v36n1a792

Masulani-Mwale, C., Mathanga, D., Silungwe, D., Kauye, F., and Gladstone, M. (2016). Parenting children with intellectual disabilities in Malawi: The impact that reaches beyond coping? Child Care Health Dev. 42, 871–880. doi: 10.1111/cch.12368

Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education, Zimbabwe (2023). Development of the national early learning policy underway. Available at: http://mopse.co.zw/blog/development-national-early-learning-policy-underway

Mkabile, S., Garrun, K. L., Shelton, M., and Swartz, L. (2021). African families’ and caregivers’ experiences of raising a child with intellectual disability: A narrative synthesis of qualitative studies. Afr. J. Disabil. 10, 1–10. doi: 10.4102/ajod.v10i0.827

Mpofu, J., and Molosiwa, S. (2017). “Disability and inclusive education in Zimbabwe” in Inclusive education in African contexts. eds. N. Phasha, D. Mahlo, and G. J. S. Dei (Rotterdam: Sense Publishers), 49–63.

Mukushi, A. T., Makhubele, J. C., and Mabvurira, V. (2019). Cultural and religious beliefs and practices abusive to children with disabilities in Zimbabwe. Global J. Health Sci. 11, 103–111. doi: 10.5539/gjhs.v11n7p103

Mutanga, O. (2022). Perceptions and experiences of teachers in Zimbabwe on inclusive education and teacher training: The value of Unhu/Ubuntu philosophy. Int. J. Incl. Educ., 1–20. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2022.2048102

Nkomo, N., Dube, A., and Marucchi, D. (2020). Rural young children with disabilities: Education, challenges, and opportunities. Int. J. Stud. Educ. 2, 134–145.

Noble, H., and Heale, R. (2019). Triangulation in research, with examples. Evid. Based Nurs. 22, 67–68. doi: 10.1136/ebnurs-2019-103145

Nsamenang, A. B. (2008). “(Mis)understanding ECD in Africa: The force of local and global motives” in Africa’s future, Africa’s challenge: Early childhood care and development in sub-Saharan Africa. eds. M. Garcia, A. Pence, and J. L. Evans (Washington, DC: World Bank)

Nsamenang, A. B., and Tchombé, T. M. (Eds.). (2012). Handbook of African educational theories and practices: A generative teacher education curriculum. Bamenda: Human Development Resource Centre

Riggall, A., and Croft, A. (2016). Eastern and southern Africa regional study on the fulfilment of the right to education of children with disabilities. Reading: Education Development Trust and UNICEF

Rugoho, T., and Maphosa, F. (2016). Ostracised: Experiences of mothers of children with disabilities in Zimbabwe. Gend. Quest. 4, 1–18.

Serpell, R., and Nsamenang, A. B. (2014). Locally relevant and quality ECCE programs: Implications of research on indigenous African development and socialization. Paris: UNESCO

Smythe, T., Almasri, N. A., Moreno Angarita, M., Berman, B. D., Kraus de Camargo, O., Hadders-Algra, M., et al. (2022). The role of parenting interventions in optimizing school readiness for children with disabilities in low and middle income settings. Front. Pediatr. 10:927678. doi: 10.3389/fped.2022.927678

Taneja-Johansson, S., Singal, N., and Samson, M. (2021). Education of children with disabilities in rural Indian government schools: A long road to inclusion. Int. J. Disabil. Dev. Educ. 1–16, 1–16. doi: 10.1080/1034912X.2021.1917525

Tekola, B., Kinfe, M., Girma, F., Hanlon, C., and Hoekstra, R. A. (2020). Perceptions and experiences of stigma among parents of children with developmental disorders in Ethiopia: A qualitative study. Soc. Sci. Med. 256:113034. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113034

Tinajero, A.R. (2010). Scaling-up early child development in Cuba. Wolfensohn center for development working paper no. 16. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution

United Nations. (1989). Convention on the rights of the child United Nations, treaty series, Vol. 1577, 3. New York, NY: United Nations.

United Nations (2006). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities (UNCRPD). New York: United Nations

United Nations (UN) (2016). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities (UNCRPD), viewed 29 October 2022. Available at: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (1994). The Salamanca statement and framework for action on special needs education. Available at: http://www.unesco.org/education/pdf/SALAMA_E.PDF

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (2021a). Right from the start: Build inclusive societies through inclusive early childhood education. Policy paper 46. Paris: UNESCO.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (2021b). Inclusive early childhood care and education: From commitment to action. Paris: UNESCO

United Nations Partnership on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, Zimbabwe (2021). Comprehensive situational analysis on persons with disabilities in Zimbabwe. Harare: UNPRPD and UNESCO.

van der Mark, E. J., and Verrest, H. (2014). Fighting the odds: Strategies of female caregivers of disabled children in Zimbabwe. Disabil. Soc. 29, 1412–1427. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2014.934441

Vargas-Baron, E., Small, J., Wertlieb, D., Hix-Small, H., Gómez Botero, R., Diehl, K., et al. (2019). Global survey of inclusive early childhood development and early childhood intervention programs. Washington, DC: RISE Institute.

Ward, C. L., Wessels, I. M., Lachman, J. M., Hutchings, J., Cluver, L. D., Kassanjee, R., et al. (2020). Parenting for lifelong health for young children: A randomized controlled trial of a parenting program in South Africa to prevent harsh parenting and child conduct problems. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 61, 503–512. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13129

World Bank Group (2017). Promising approaches in early childhood development: Early childhood development interventions from around the world. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Keywords: inclusive education, disability, low- and middle-income countries, early learning, home-based

Citation: Tafirenyika J, Mhizha S and Ejuu G (2023) Building inclusive early learning environments for children with a disability in low-resource settings: Insights into challenges and opportunities from rural Zimbabwe. Front. Educ. 8:1029076. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1029076

Edited by:

Julie Ann Robinson, Flinders University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Patricia Kitsao-Wekulo, African Population and Health Research Center (APHRC), KenyaKudzayi Savious Tarisayi, Stellenbosch University, South Africa

Copyright © 2023 Tafirenyika, Mhizha and Ejuu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Joice Tafirenyika, dGFmaXJlbnlpa2Fqb2ljZUBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Joice Tafirenyika

Joice Tafirenyika Samson Mhizha

Samson Mhizha Godfrey Ejuu

Godfrey Ejuu