- William Howard Taft University, Boyer Graduate School of Education, Denver, CO, United States

Background: The 2020–2021 school year shut down because of the COVID-19 pandemic brought an unprecedented burden on parents, especially those with special needs children. Parents with children with special needs were left to assist their children with remote learning at home using technology for the first time. These students with special needs were used to face-to-face and one-to-one classroom learning by skilled educators but are now left to be educated by their parents.

Objective: This study explored parents’ experiences assisting their special needs children with remote learning for the first time, using technology at home during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Method: A transcendental (descriptive) phenomenology was undertaken to explore the experiences of nine participants, recruited from two school divisions in Manitoba, Canada, on their child’s education and the challenges they experienced during remote learning from home. A purposive sampling technique was used, and data were collected through telephone interviews.

Results: Eight out of nine parents reported a negative experience with remote learning. Four major themes emerged after the data analysis: participants’ fear and anxiety during remote learning, difficulty maintaining routines during remote learning, students’ behavioral issues and mental health changes during remote learning, and lack of home support during remote learning. Furthermore, results indicated that integrating technology in remote learning for students with special needs was ineffective.

Conclusion: This study suggests poor communication between parents and teachers, and parents’ desire to be involved in planning remote learning for students with special needs during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown was not met. This study also suggests that schools failed to meet students’ IEPs during remote learning. Furthermore, this study highlights that remote learning for special-needs students is inappropriate without educational assistance.

Introduction

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, children with disabilities attended school and participated in in-person classroom learning. In Canada, students with disabilities are integrated into mainstream education with special support if needed (Education Profiles, 2020). Part of the educational policy in Canada is to include special needs students in regular classrooms (Education Profiles, 2020). Some schools provide special needs education where students cannot integrate into mainstream education (Education Profiles, 2020).

Traditionally, learning has been done face-to-face in classrooms, but the COVID-19 pandemic transformed the learning process into remote (online) learning for many students (Daniela et al., 2021). Daniela et al. (2021) stated that transferring classroom learning to remote learning because of the COVID-19 pandemic shocked the educational system, and parents became “homeschoolers within a few days without prior training” (p. 1). Research has shown that online learning may not suit all students and families, especially students with disabilities (Black et al., 2020). Using technology to help students connect with their classrooms from home was a significant concern for parents because of their lack of experience with remote learning [United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 2020]. Parents taught their children remotely without training (Daniela et al., 2021). Some parents had to face the combined challenges of maintaining family life, work life, and teaching (Fisher et al., 2020). Additionally, some parents had to reduce their working hours or take unpaid time to help their children with remote learning (Kalil et al., 2020). These lifestyle changes impacted their family’s financial condition, physical well-being, and mental health (Fisher et al., 2020; Kalil et al., 2020).

Parents who have displeasure with formal schooling make a conscious decision to educate their children at home (Yin et al., 2016). On the other hand, COVID-19-induced homeschooling was not a choice made by parents (Daniela et al., 2021). In this case, parents had no choice but to educate their children at home due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the shutdown of schools (Garbe et al., 2020; Hakkila et al., 2020; Widodo et al., 2020). English (2021) and Burke (2021), as cited in Daniela et al. (2021) called these parents “accidental homeschoolers” (p. 1). Homeschooling is legal in Canada (Homeschool.Today, 2020), and parents do not need a college degree to homeschool their children (Heuer and Donovan, 2017). Moreover, parents have options for part-time homeschooling during contemporary homeschooling with a public school, and students can participate in school extracurricular activities, including athletics, depending on the district’s approval (Heuer and Donovan, 2017). This differs from the COVID-19 induced homeschooling, where all school activities were closed, and parents had to provide activities for their children [Bhamani et al., 2020; Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2020].

The implementation of social isolation and distancing needed due to the COVID-19 pandemic added an unprecedented burden on individuals and families, especially those parents with special needs children (Rose et al., 2020). The closure of schools made it impossible for students to use the school environment to interact and socialize with friends (Bhamani et al., 2020; Goldschmidt, 2020). The home became their playground and learning environment where parents were left to teach and entertain their children [Bhamani et al., 2020; Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2020]. Children with special needs have virtual learning challenges that children without special needs have (Villano, 2020). For example, a child with down syndrome may not be able to log into a computer and navigate some of these schools’ learning software platforms. In contrast, a child with no disability of the same age could log in easily without assistance. Villano (2020, p. 3) stated that “what works for some students may not work for those students with special needs”.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, parents with special needs children did not feel their children were fully included in distance learning planning (Duraku and Nagavci, 2020; Toquero, 2020). Consulting with parents and using their experiences could have helped educators plan virtual learning programs to meet students’ individual education plans (IEPs) (Villano, 2020).

This study was conducted because several studies recommended future research to explore parents’ experiences in assisting their children’s remote learning using technology (Burdette and Greer, 2014; Bhamani et al., 2020; Duraku and Nagavci, 2020; Garbe et al., 2020; Koskela et al., 2020; Toquero, 2020). It was also unclear whether online remote learning suited all students and families, especially students with disabilities (Black et al., 2020). School’s sudden closure and the resulting conversion of traditional classroom learning to distance learning did not allow parents to prepare for a teacher’s role (Letzel et al., 2020; Daniela et al., 2021). Parents lacked the necessary training to assist students in this new environment (Letzel et al., 2020; Daniela et al., 2021), which added an unprecedented burden on them, especially those with special needs children (Rose et al., 2020). Nevertheless, parents’ stories showed they used their self-efficacy to motivate themselves to assist their children with remote learning. Albert Bandura, a social psychologist, believed that people do what they do because they believe in themselves to complete a job. This is referred to as self-efficacy (Owens and Valesky, 2015). Cherry (2020) stated, “Self-efficacy is a person’s belief in their ability to succeed in a particular situation” (p. 1). Therefore, these beliefs determine how “people think, behave, and feel” (Cherry, 2020, p. 1).

Methodology

This study explored the challenges and rewards parents of children with special needs encountered while assisting their children with remote learning for the first time from home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Knowing these parents’ challenges or rewards while helping their children with remote learning will provide school divisions, educators, and policy-makers an opportunity to plan and prepare parents better for future remote learning. Also, educators and parents would know whether remote learning is suitable for students with disabilities. This study received institutional review board approval from William Howard Taft University, Colorado, United States.

Participants

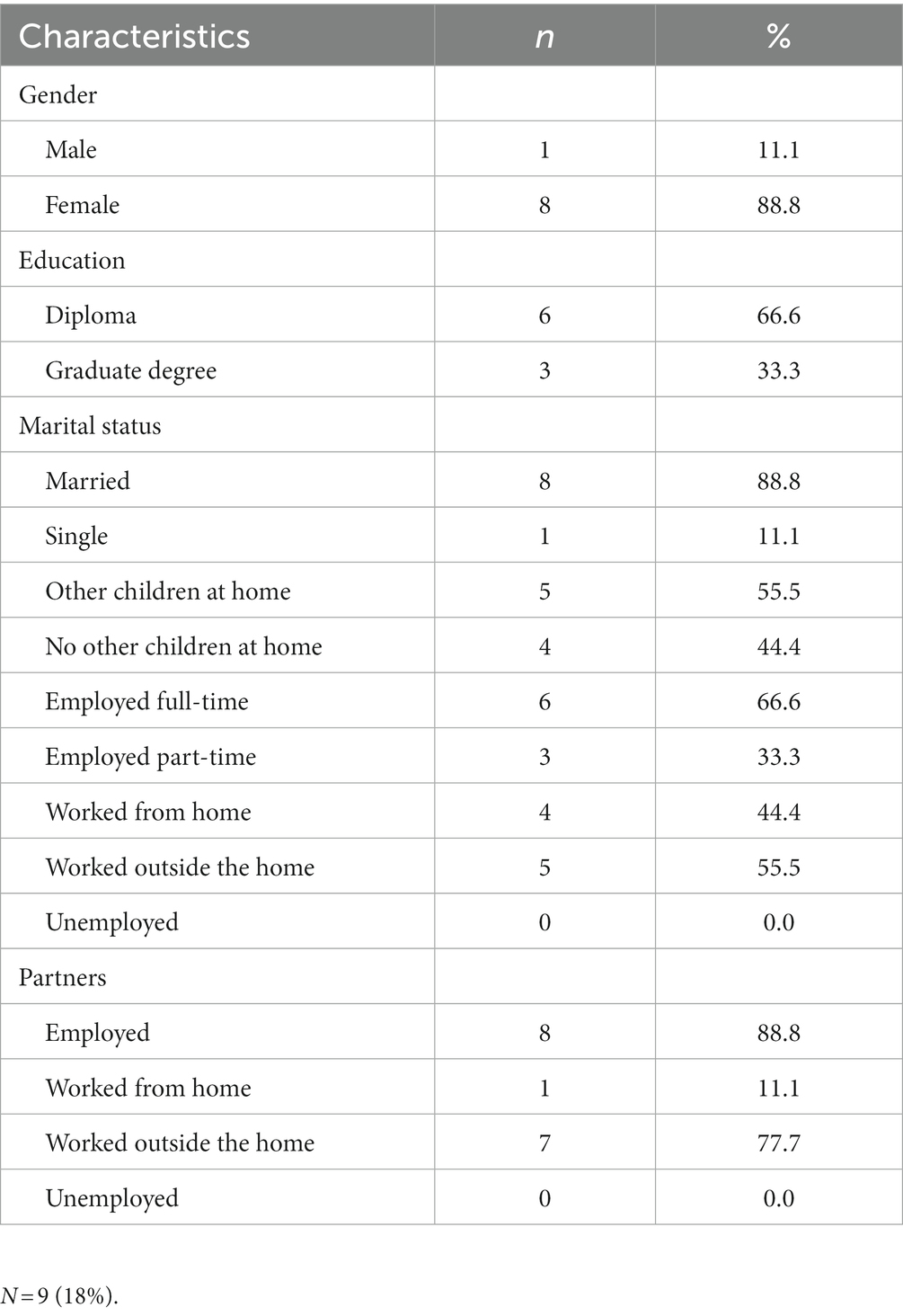

Participants for this study were recruited from two school divisions in Manitoba. One school division is in an urban area, while the other is rural. The schools involved have students with special needs who participated in remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown, which qualified their parents or guardians to participate in this study. This researcher dropped off the envelopes containing the study invitation to teachers for distribution. Teachers identified children with special needs who participated in remote learning with their parents during the COVID-19 pandemic and gave them invitation envelopes to give to their parents. Parents willing to participate in the study contacted the researcher via phone and emailed their consent forms. The child’s disability was confirmed with each participant before conducting the interviews. Eight participants identified as parents and one as a guardian. Participants identified as working class, with some holding more than one job. Participants included eight females and one male of different races and ethnicities (Table 1).

Sample

In this study, purposive sampling was used to recruit willing participants to inform the study (Speziale Streubert and Carpenter, 2010). The strength of purposive sampling is selecting information-rich participants who can inform the study (Isaac, 2006). Purposive sampling also helped the researcher learn a great deal about the issues that affect the participants and those central to the research’s purpose (Isaac, 2006). Data collected from purposive sampling are rich in the participants’ experiences and viewpoints on the investigated subject (Isaac, 2006).

Selection process

Parents and guardians of school-going children with special needs educated at home through distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic were selected for this study. Parents and guardians younger than 18 years were excluded because they were ethically considered minors and would have needed an adult to sign the consent on their behalf. Thus, parents’ and guardians’ confidentiality and privacy in this age group could not be assured because a third party would be involved. Parents and guardians who could not speak English were excluded, as the interviews were conducted in English, and the cost of employing a translator would have been prohibitive. This researcher used a sample size that was large enough to “allow the unfolding of a new and richly textured understanding of the phenomenon under study, but small enough so that the deep, case-oriented analyses of qualitative data is not precluded” (Sandelowski, 1995, as cited in Vasileiou et al., 2018, p. 2).

Researcher positionality

This researcher has a teenage son with a disability who took part in remote learning for the first time during the COVID-19 pandemic school closure. Although this researcher did not participate in this research, they brought plenty of knowledge regarding understanding participants’ stories in educating a special needs child online using technology for the first time. This researcher’s son’s school used Microsoft teams to connect with students; this researcher’s son could not log into Microsoft teams and needed help. Once connected to Microsoft teams, keeping him focused on the screen, staying focused in front of the camera and communicating with his peers and teachers was challenging. This researcher used their knowledge and experience of educating a child with special needs remotely during the data collection process. This was an advantage for this researcher because of their personal experience educating a child with special needs from home for the first time.

Data collection

A semi-structured, individual interview was this study’s chosen data collection method. This was because “semi-structured interviews are those in-depth interviews where the respondents have to answer preset open-ended questions” (Jamshed, 2014, p. 1). With semi-structured interviews, there was more flexibility in the interview process (Jamshed, 2014). Although an interview schedule was used, it allowed for “unanticipated responses and issues to emerge through the use of open-ended questioning” (Todd, 2006, as cited in Ryan et al., 2009, p. 310). Parents were asked questions such as: how would you describe your position as a novice parent-teacher? How did you feel when you were told schools were closed and your child would have to learn from home, knowing you are now responsible for your child’s education? How did you handle that shock, if any? No pilot study was conducted because the researcher used open-ended questions from a schedule guide. These questions are unique and changed during the interview process. Instead of conducting a pilot study, the interview schedule and tentative open-ended questions were reviewed by an expert panel and through member-checking.

The interviews were conducted one-to-one via phone, which helped overcome misunderstandings or misinterpretations of certain words by the participants. Unlike other data collection methods for qualitative studies, such as questionnaires or surveys, with telephone interviews, the researcher could ask participants to clarify words or explain further what they were trying to convey. Such actions helped clear any doubts the researcher may have about the data provided by participants. The researcher asked predefined questions and tried to leave more freedom for the interviewee to talk. Through the interview process, the lived experiences of the interviewee were identified and discussed. The semi-structured interviews lasted between 30 min and 40 min. The interviews were carried out in September and October 2021. Data were collected from participants who declared that they had at least one special needs child who attended traditional classroom learning and changed to remote learning due to the school lockdown. See Table 2 for characteristics of participants’ children with disabilities. All interviews were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed. A follow-up phone call was made to participants after transcribing the interviews to ensure accuracy. Participants were offered a summary of the interview but declined. This researcher could not perform face-to-face interviews as initially planned because of the spread of the COVID-19 Delta variant. During the interviews, Manitoba had restrictions where people should stay 2 meters apart, wear masks, and avoid social gatherings.

Data analysis

This researcher utilized the process described by Colaizzi (1978), as cited in Wojnar and Swanson (2007) to identify the themes. Reviewing and rewriting themes helped decide whether a theme applied equally to all participants. Colaizzi developed seven steps for analyzing descriptive phenomenological data. These steps include reading and rereading the data collected and extracting statements related to the topic. Afterward, the researcher categorized meanings into themes and integrated the “findings into an exhaustive description of the phenomenon being studied” (Colaizzi, 1978, as cited in Wojnar and Swanson, 2007, p. 176). The final step was to validate the findings and “incorporate any changes offered by the participants into the final description of the essence of the phenomenon” (Colaizzi, 1978, as cited in Wojnar and Swanson, 2007, p. 176). This researcher asked five of the nine participants to validate the findings, and changes offered by participants were incorporated into the final results to fulfil the analytic process’s final step as described by Colaizzi (1978), as cited in Wojnar and Swanson (2007). In the final analysis, the formulated meanings became clusters of themes that are common to all participants.

Results

A total of four categories of themes were extracted from participants’ statements that pertain to the phenomenon under investigation. The themes include participants’ fear and anxiety during remote learning, difficulty maintaining routines during remote learning, students’ behavioral issues and mental health changes during remote learning, and lack of home support during remote learning. The findings focused on these four themes and how they relate to parents’ and guardians’ experiences in assisting their special needs children with remote learning from home. Participants’ verbatim accounts accompany most of the descriptions.

Theme one: Participants’ fear and anxiety during remote learning

Participants reported that this sudden change of becoming teachers overnight caused fear and anxiety, as they were left with no option but to become parent teachers. The theme of fear and anxiety was equally shared among eight out of nine participants. When participants were asked about their experience of becoming a parent-teacher, one said, “I felt absolutely sick to my stomach. I was full of dread…I did not know how I was going to be able to manage that.” When asked about how they felt in their new role as parent-teachers, this participant said, “I was pretty worried about it, and I was scared because I did not know…how I was going to juggle…my work responsibilities.” Another participant stated, “there was a little bit of concern and fear, wondering how long this was going to last.” This other participant said:

I felt good that the kids were being pulled out of school because we felt really unsafe with the unknown of the CoVid virus. But I’ll be honest; I was a little bit panicked…because I had to work from home as well, and I was working two jobs at the time.

The research revealed that participants were anxious about their new role as novice teachers from participants’ stories. All nine participants reported doing homeschooling for the first time with no prior knowledge and preparation for homeschooling. Participants also said that they received no training or directions from their schools on educating their special needs children at home. Six out of nine participants received materials from their schools but with little guidance. Participants said they received reading books, picture books, games, puzzles, project-building materials, worksheets on math concepts, and matching activities. Participants stated they used their own materials that they felt comfortable with to teach their children. Participants also said they tried to reach out to schools, but there was poor communication by some of the teachers.

After trying to reach some teachers with no success, one participant said, “Teachers could have touched base a little bit more directly with me. As I said, I had one exceptional teacher, and the others are just terrible.” Another participant, when asked if they reached out to schools for guidance, stated that they sympathized with teachers because they had a lot of students to deal with at the time. Another participant shared a similar sentiment and stated they understood because everyone, including teachers, struggled at the start of the pandemic. This is what another participant said when asked about reaching out to teachers for help and guidance with schoolwork:

I found I will ask for things… but they will just send me more of the same that we were not using. It’s very hard to…know what you need to ask for when you are turned into the teacher, so you are like deciding all these decisions.

In terms of participants’ fear and anxiety with remote learning, one participant shared the following:

Well, I handled it with…a lot of dread…because, being a public health nurse, I knew that I was going to be very, very, very busy…and so my time was going to be very limited to help him. So…I was pretty worried about it, and I was scared.

Participants continually noted their concerns about being a parent-teacher for longer than expected and gave accounts of how they were filled with fear. Although all of the nine participants said they welcomed the initial lockdown, they said they were not expecting to be in their teaching role for a more extended period. They reported that they hoped that the lockdown was temporary and schools would reopen in a few weeks. This participant stated, “I thought we’d be home for a week, and then everything would go back to normal.” Another participant said, “I was absolutely devasted…I cried. I was sad, anxious, angry.”

Two participants reported fewer struggles in assisting students with special needs at home with remote learning, while seven reported challenges. The seven participants stated they did not believe they had the skills to teach children with special needs at home. One participant recalled how the school never sent homework with their child because of the difficulties teaching their child at home. This participant said:

In the past, in terms of assisting him with homework, we were never able to do that. So, the school never sent homework home because it will turn, you know, it will turn explosive. So, going from that experience to all of a sudden to now, I was going to be required to assist him with daily learning… I was overwhelmed with how am I going to do that if I could not even get him to do, you know, simple activities in terms of homework in the past.

Seven out of the nine participants told similar stories, indicating how they were overwhelmed with fear and anxiety when they heard the news that their children would have to do remote learning from home. When asked about their experience, this participant said, “I will say terrified and frustrated.” This researcher noted that fear and anxiety were still evident in participants’ voices when describing their experiences during the interviews. Some participants said they are still trying to heal from their experiences even after a year. This participant stated: “It was a life-changing experience…and we are still recovering from some of that.”

Theme two: Difficulty maintaining routines during remote learning

Difficulty in maintaining routines was another theme echoed throughout eight participants’ stories, saying that the lockdown of schools disrupted their routines and severely disrupted students’ routines. Eight out of the nine participants confirmed the idea that children with special needs thrive on routines. Participants stated that schools provide a good learning structure for students with special needs, which they said they could not provide at home. Participants said closing down schools and changing to remote learning at home removed that structural learning part of their routines. This is how one participant noted their experience when asked about maintaining routines during remote learning:

For him, he doesn’t necessarily understand…following the same routine or structure in a different environment. And having that structure of school and focusing on academics in a home was just not something that he could wrap his head around.

Furthermore, another participant described a similar experience by saying, “It’s definitely different, but we tried to follow a routine so that it will be like also in school… we tried to follow it, but it was difficult for sure.” Participants were asked to describe how school authorities can maintain routines for special needs students during a pandemic. One participant said that school authorities should “try and keep everything the same as much as possible for those kids with special needs. If it is into their own classroom again as needed, then try and keep things the same.” Another participant said:

Initially, we were told…it would just be two weeks…and in addition to spring break, that was kind of combined, and so three weeks in total, the children will be home…so, at that point, it was, you know, ok, like it was ok, you know, we can get through 3 weeks of this, that’s ok…but then in the midst of that, the announcement came that it was going to be like prolong, probably until the end of the school year, last year, and…you know I was absolutely devastated that, that was going to happen, that my son was going to be home and not in school, not in that structured setting…for that amount of time.

On the one hand, I want them to be safe, but on the other hand…he needed the structure and stability that the school environment offers, and I could not provide that at home to him…allow the children that have these learning challenges to remain in the school setting.

Participants talked about school routines that they were unaware of that the children were doing in school. Therefore, when they tried to implement their routines at home, it caused friction between parents and students. This participant said:

I was not aware of certain pieces of the puzzle that they may have been started before and how they did things at school and because he is so much a routine person, I could not change it up for it to make more sense for him because he would say no the teacher tells us to do it this way.

This researcher followed up by asking why participants were unaware of their children’s routines in school. Participants stated that not knowing their children’s school routines was due to poor communication with the teachers. Participants said teachers failed to explain to them these school routines so they could use them during remote learning. One participant said, “I think that we do know our kids best as parents, and I think that the school should have tried to involve us a little more in the process, as they always should.” Furthermore, another participant echoed the same idea by saying:

I was just overwhelmed by different things that he knew at school that I wasn’t sure of…I just got really frustrated with not knowing the rules of the activities, and then I was trying to figure out the rules.

Participants said they reached out to teachers, but that communication was poor, and parents did not know what to ask for. Participants believed removing students with special needs from a structured school environment with routines could have affected their behaviors, as one participant described it this way:

He became really socially isolated, which I think was compounded by the school closure… now, he no longer had access to his peers, and he struggles with social isolation to begin with, so to remove him from the school environment just exacerbated that.

Participants also described how the lack of a school structure affected students’ learning at home. This participant said, “Just convincing him that now we have to do school at home was a bit of a challenge; getting him to like, understand that concept was hard.” Another participant expressed their experience by saying:

The lack of structure at home, not that we are not structured, but you know, the school is set up differently, they have different support there…they have a different schedule, so those things were lacking in the home environment. You can’t really replicate that at home.

Participants gave details of how their children with special needs thrive on routines, and their accounts showed that routines could be age-specific. Their accounts showed that the older the child, the more they rely on routines than younger children. Furthermore, participants expressed that their routines were more affected if working full time. According to participants’ stories, parents working part-time and homestay parents had less disruption to their routines than parents with full-time jobs. This participant said, “Luckily, I’m just part-time, so him staying at home did not affect our routine that much.” Participants were asked if they would like to homeschool their special needs children after experiencing homeschooling for the first time during the COVID-19 pandemic. All nine participants stated they would not be able to homeschool their children. The main reason reported by participants is work and lack of skills. Six out of the nine participants have full-time jobs, and the remaining three have part-time jobs (see Table 1 for characteristics of participants). Participants with full-time jobs reported having more problems maintaining routines than those with part-time or working from home.

Out of the nine participants, four were working from home. One of the four participants working from home had two more jobs. Another participant said that homeschooling was not possible because their child takes directions from other people better than them. Another participant said, “I do not have time because I work a full-time job.” When asked about the possibility of homeschooling, this was echoed among participants, and one participant said, “not really because I think it is still important to socialize with other kids…being in school.”

Theme three: Students’ behavioral issues and mental health changes during remote learning

Participants described their concerns with remote learning for children with special needs. All nine participants said they do not believe remote learning benefits children with special needs. Participants described how they noticed their children with special needs became more aggressive, disobedient, and uncooperative with learning. Parents stated these behavioral changes only surfaced since they started remote learning with their children. Participants said they were worried about their mental health and their children because of their children’s behaviors. This is how one participant described their child’s behavior:

My personal safety was at risk because…he often gets violent towards me…whenever expectations are asked of him…it increases the safety risk, and actually, things really erupted, you know, when we try to have him sit down with any mask or anything like that. I even had a respite worker who was a teaching student at the time…come in, and she would sit down with the kids every day to try and do work with them. He had a pretty massive violent incident that resulted in having to call the RCMP [Royal Canadian Mounted Police]. Because of his absolute refusal to do the work.

The parents said the child’s pattern of behavior was not new but was exacerbated by remote learning because of the new expectations with learning from their parents. One guardian said that schools’ lockdown and subsequent change to remote learning affected the child’s behavior so much that the child would become aggressive, and sometimes “he would smash the computer or throw the keyboard.” These parents also reported that their child’s behavior was exacerbated during remote learning because of the demands from parents when teaching or assisting their child in remote learning. Eight out of nine participants stated they noticed their children’s behaviors worsen during remote learning, which was upsetting. Participants expressed that safety became an issue because of the behavioral changes they believed were brought on by remote learning. One parent stated they had to stop assisting their child with remote learning, and this is their account when asked if remote learning at home was a good choice:

For my personal sanity and for the health of our relationship going forward, no. I am not a teacher; if that were my calling in life, it would be different, but I am not a teacher…his aggression and violence were quite paramount during that time…it was not worth our mental health and our physical safety to continue to push him on it so, unfortunately…the schooling ended for him…really early on in that shutdown.

Another parent, when asked the same question if keeping students at home was the right choice, stated:

Knowing what I know now about the virus, I think we would have felt better sending him. I think all of us would have been better off with our mental health, sending him, and I think he would have made some greater strides throughout the last year with his development.

One parent said, “It was stressful…to the point that I wanted to send him back to school…and he is probably better with others.” Another participant stated that they noticed behavioral changes in their child and said, “He has some behavioral issues come up with his routine.” Describing their experience with their child’s behavioral changes after seeing a physician, this participant said:

He developed what’s called Cyclic Vomiting Syndrome from anxiety and stress. So, he spent probably three months…throwing up three to four times a day at least.…He lost an insane amount of weight, like so much weight.… They had him on a medication that they give to people undergoing chemo…that helps them keep food down in a desperate attempt…for him to eat and digest food.

Another participant described their child’s behavior by saying, “In the beginning; yes, his… behaviour was affected and…it changed the way he does things.” The narration of participants’ experiences showed a common theme regarding the change in their children’s behavior. Another participant, when asked about their child’s behavior, said, “It was definitely harder…it’s hard for her to focus more.” One participant talked about their child’s behavior and said, “It was hard…I learned strategies to try and mitigate what his violent behaviour will be.” This participant was further asked what strategies they utilized to mitigate their child’s behavior and said:

At times, I would have another person come into the house to be there with me while I was telling him…the mall has been closed and…we won’t be able to go to the mall. Just so that when he would get violent, there would be someone to help me calm him down…until he…would have gone past his need to hit or break things.… It was incredibly stressful…my anxiety went crazy…and at times, it definitely felt like I was trapped in my house cause we couldn’t go anywhere together.

Participants echoed this concern as they kept telling the same story about the change in their children’s behavior during remote learning. Eight out of nine participants said they were overwhelmed with fear and anxiety because of these changes in their children’s behaviors, which affected their relationships during the remote learning period. They describe their experiences and the support needed during that difficult time.

Theme four: Lack of home support during remote learning

Nine out of nine participants saw supporting children with special needs at home with remote learning as fundamental in achieving remote learning and students’ individual education plans (IEPs). One participant talked about the support they received from the school and said:

Some of it was really, really excellent, and some of it was really, really poor. It was teacher-dependent, I found…The one teacher was very good, and the other teacher was terrible. She was not very organized, so I couldn’t get him organized ahead of time.

Another participant said, “They tried. I feel like they tried, but I do not think they were prepared to support all of these kids, certainly trying to learn from home. This participant described the experiences by saying:

I know in other provinces, they did open schools up to special needs students, and I think we would have felt safe doing that…even with the virus, if they wear a mask and take the proper protocols and it would have been a huge weight lifted off our shoulders because ultimately, we felt responsible for him not succeeding last year in his academics, right? But we weren’t just able to keep up with it; it’s too hard.

Participants narrated examples of how many things can be achieved with students with special needs with remote learning. Participants said some teachers provided good support to students; for example, one participant said:

He had a gym teacher that obviously was not very busy because she was not teaching gym…she would…log on, on teams with him almost every day, and do gym activities with him every day. She was absolutely amazing…they would both get on the treadmill, or once the weather got nice, she would come over and socially distance walk with him; it was amazing.

Participants were asked about the kind of home support they believed they needed to help their children with remote learning, and one participant said, “It would have been nice to have more support from the other people who worked with him at school.” Another participant said:

I feel like having in-home support with an EA [educational assistance] possibly; I think all other parents will say that. You know, even if it was just…for certain kids, maybe they need it every day, but for mine maybe, he could use it for half a day or something like that…he would not need somebody every day of the week, absolutely. But I just find that even when his gym teacher would log in and do stuff with him online, I think she usually did it about two to three times a week, for almost an hour. He was just so much more engaged in the process; even though she was not teaching him math or anything else, she was kind of his lifeline to school. And so, even though that was a virtual kind of incident, I can imagine how beneficial in person would be, even if it was with a mask and PPE.

This researcher found that home support was vital for participants to ensure their children get some education at home during remote learning. Parents stated their children have EAs on their IEPs in school, but this option was not provided at home during remote learning. In Canada, the individual education plan (IEP) is “an individual education plan designed for a student that includes one or more of the following: learning outcomes that are different from, or in addition to, expected learning outcomes set out in the applicable educational program guide; a list of support services; a list of adapted materials, instruction or assessment methods” (British Columbia, 2016, p. 2). Schools in Canada must develop an IEP for students with special needs, a process that involves including input from the child’s parents (British Columbia, 2016).

Outliers

According to Garbe et al. (2020), “Outliers is defined as a response not captured by other themes, but yet noteworthy enough to code” (p. 55). These outliers are not recurring experiences throughout most of the participants. One response that falls within the outliers was when one out of nine participants stated they had no struggles with remote learning. This participant said, “Luckily, I’m just part-time, so him staying home did not affect our routine that much.…he is not social…I do not think he missed that interaction with other kids as much as others do.” Another participant responded similarly by saying, “my son…did not have homework…so…I did not have to deal with that. I had to deal with him being here, but I did not have to deal with…teaching him.” Although participants described their struggles with remote learning, two out of nine reported fewer struggles. Participants stated that their children with special needs thrive on routines, but one participant said, “My son can actually have a change without being upset.”

This researcher noted that eight out of nine participants had functioning computers at home, which their children used for remote learning. In contrast, one participant reported using their cell phone because there was no computer in their home. A follow-up question on how their child could participate in remote learning resulted in the participant saying, “We do not have a computer at home. So, at the time, he could only do that when I was home, and he would use my phone.”

Discussions and recommendations

Results of this study showed no difference between urban and rural participants’ experiences. The four themes that emerged from the study’s findings are participants’ fear and anxiety during remote learning, difficulty maintaining routines during remote learning, students’ behavioral issues and mental health changes during remote learning, and lack of home support during remote learning. Each theme will be discussed in this section.

Participants’ fear and anxiety during remote learning

Participants stated they had fear and anxiety while assisting their children with remote learning because of their children’s behaviors. Parents stated that they were not teachers, and changing their roles from parents to teachers caused friction between them and their children to the point where the children hated their parents. Accounts of participants’ experiences showed that parents’ relationships with students deteriorated during the remote learning period. Fear and anxiety expressed by parents in this study were also reported by Bhamani et al. (2020) when they said parents found the sudden closure of schools “extremely disturbing” (p. 15). The uncertainty of the end of the COVID-19 pandemic naturally manifested fear in people (Daniel, 2020). A recent study by Averett (2021) also confirmed that parents struggled with fear and anxiety during the remote learning period.

Similar to other studies such as Brooks et al. (2020) and Rose et al. (2020), parents in this study reported experiencing more stress while trying to help their children with distance learning. Stress and mental issues are common phenomena documented by many studies that people felt during the pandemic and stay-home orders (Brooks et al., 2020; Rose et al., 2020). This study showed that parents had stress and mental health issues because of the lockdown and subsequent remote learning duties. This result aligns with Garbe et al. (2020) recommendation to investigate the long-term effects of remote learning on parents. Parents also confirmed that their children suffered stress and anxiety issues during the remote learning period. This confirms what other studies stated. Although little attention has been given to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children’s mental health, children with disabilities are more vulnerable to mental health problems than their counterparts without disabilities (Patel, 2020; Aishworiya and Kang, 2021). A study by Smith et al. (2016) confirmed that parents felt frustrated, stressed, and anxious about the challenges of remote learning.

Additionally, findings from this study seem to correlate with similar studies from Bhamani et al. (2020) and Daniela et al. (2021), who stated that parents were concerned with their ability to keep their homes and jobs running smoothly without neglecting their children during remote learning. Other studies have reported obstacles for students with disabilities during distance learning, such as the absence of necessary learning equipment, Internet access, and a lack of accessibility to school materials and support (United Nations, 2020a). A study by United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (2020) showed that parents expressed a lack of experience with online learning and access to technology as their primary concerns. This is contrary to what parents stated in this study. Parents in this study said they had access to technological equipment and no problems using them. Unlike results from United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO] (2020), parents’ primary concerns in this study were having to take time off work, reducing their working hours, not being able to assist other siblings with remote learning, and getting students to focus and participate in front of a computer screen.

Parents complained that one of the reasons for experiencing these difficulties was that schools consider all students intellectually equal by providing students with the same technological resources to connect with their teachers from home. This problem was confirmed by Villano (2020), who stated, “Individualization is hard when you have a distance program trying to serve everybody” (p. 7). Findings from this study also correlated with that of Averett (2021), who stated that students with disabilities had “difficulties navigating technology and various learning apps and platforms, and difficulty with different teaching modalities than what students normally experience” (p. 5). Additionally, in this study, parents with other children doing remote learning reported a significant difference when helping their children with no disabilities. Parents said it was easier to assist their children with no disabilities than those with disabilities. Villano’s (2020) study results also stated similar findings where parents found it easier to help students with no disabilities with remote learning.

Parents reported a lack of communication between schools and parents regarding what the students already knew, what they were currently being taught, and how they were being taught. Garbe et al. (2020) also reported a lack of communication between schools and parents during remote learning. However, their study was done during the remote learning period and, therefore, did not capture the long-term experiences of parents, which they acknowledged in their report. In their study, Averett (2021) also stated that there was no clear communication between parents and teachers, which would have helped improve parents’ experiences. Students are back in school during this study after more than a year since the lockdown and remote learning. This researcher hoped that conducting this research after the COVID-19 lockdown would give parents more time to process the questions and clearly narrate their stories.

There have been concerns from other studies on whether online learning is suitable for students with disabilities (Black et al., 2020). In this study, eight out of nine parents felt online learning was inappropriate for special-needs students. Empirical research, such as United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (2020), has shown that online learning does not suit all students and families, especially students with special needs. UNESCO further stated that using technology to help students connect with their classrooms from home was a significant concern for parents because they lacked experience with remote learning. Parents confirmed this concern in this study by saying that remote learning was not suitable for their children because they do not have teachers’ skills, time and patience to teach special needs students.

This researcher noted that parents’ self-efficacy motivated them to take up this new role to assist their children’s education because they did not want to see their children fall behind. Even though parents became teachers overnight, their accounts showed they were determined to assist their children with special needs with remote learning because they wanted to see them succeed. As described by Albert Bandura, their self-efficacy kept parents motivated to help their children’s remote learning. Results from this study confirm that of Villano (2020), who stated, “Students with special needs are just going to struggle with the shortcomings of virtual learning” because of their special needs (p. 6). Although other studies stated different concerns for parents with remote learning [Garbe et al., 2020; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 2020], the main problems reported by parents in this study were maintaining routines for their children and the behavioral change of their children as a result of remote learning.

Difficulty maintaining routines during remote learning

Maintaining routines in the home was reported by parents as challenging. Parents said they struggled to keep any routine for their children. Parents expressed that their children found it difficult to understand that their homes are now their schools, making it harder for students to accept that they should maintain their school routines at home. Other studies also confirmed this problem for parents; for example, Bhamani et al. (2020) stated that parents had developed routines for their children during school times before the pandemic, and suddenly those structured routines were disrupted. Garbe et al. (2020) also stated, “School closures have unprecedentedly altered the daily lives of the student learners, their families, and their educators” (p. 45). This finding was also confirmed by Averett (2021), who stated that children’s routines were disrupted due to the school lockdown and subsequent remote learning.

Parents expressed frustration because it affected their routines and the amount of attention and help given to their other children doing remote learning. Five of the nine participants had other children at home to look after while assisting their special needs child with remote learning. Some parents who were essential workers who had to go to work said they relied on routines to get to work on time and ensure the children were organized and ready to connect with their teachers. Five participants worked outside the home, while four worked from home during the lockdown. One participant’s partner worked from home, while the rest worked outside the home. Parents with teenagers said they were less affected than those with younger children. Parents said it was easier to leave the teenagers at home and check on them regularly by phone.

On the other hand, parents with younger children said they could not leave their children alone because of their ages. Therefore, these parents with younger children said they had to change their working hours to spend more time at home with their children. A similar study by Leonhardt (2020) described how parents panicked because of the lack of ideas on balancing work and remote learning for their children. Other studies have also shown similar results to this study, as parents revealed that the COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdown of schools impacted children and parents’ daily routines and children’s learning (Bhamani et al., 2020; Fisher et al., 2020; Daniela et al., 2021). Averett (2021) reported similar findings stating, “Parents of younger children tended to report that remote learning was more of a challenge than those whose child with a disability was older” (p. 9).

Students’ behavioral issues and mental health changes during remote learning

The theme that was a common thread among all nine participants was students’ behavioral changes. This theme made participants say they would never accept future remote learning for their children. Although one participant said they enjoyed remote learning, they still noticed behavioral changes and sent their child back to school when in-person classroom learning started. Some of the changes reported by parents were minor, while some were severe. Parents said they noticed changes in their children’s behaviors and attitudes to the extreme that their safety became a concern. Parents reported that they only saw these new behaviors since the lockdown and remote learning. When asked why they believed these changes happened, one parent said their child was training for the Special Olympics, which had to be canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Another parent said their child used to go to the mall and look around but had to stay indoors because the mall was closed. Another parent stated that their child, who loves swimming, could not go swimming because swimming pools were closed. Parents expressed that students became very aggressive and abusive, while some became physical with their parents. This researcher noted from parents’ accounts that things were so bad one parent needed a second person to be around the house at all times during remote learning, while another parent had to call the police on their child. As other studies have shown, parents believed that the lockdown did not help children with special needs because the closure of schools made it impossible for students to use the school environment to interact and socialize with friends (Bhamani et al., 2020; Goldschmidt, 2020).

Parents told this researcher that the behavioral changes in their children with special needs caused by remote learning made them more worried about their children’s mental health than the virus. Other studies have reported similar mental health concerns from parents of children with disabilities (Di Marino et al., 2018; Patel, 2020; Rose et al., 2020; Thorell et al., 2020). Parents with teenagers reported more aggression and violence toward them than parents with younger children. There were six parents with teenagers in this study, ranging from 13 to 21 years. Smith et al. (2016) reported that conflicts between parents and children were common with remote learning. Averett (2021) stated similar findings to this study where one parent in that study said her child “flies into these horrible temper tantrums. And then I spend a lot of time kind of repairing both her and the house after the tantrums” (p. 7). Parents in this study expressed that remote learning was ineffective because of their teaching difficulties and their children’s behavioral changes. This result aligns with Toquero’s (2020) recommendations to investigate the effectiveness of remote learning.

Conclusion to strategies identified to help parents

This study suggests home support as one strategy identified by parents to help their children with remote learning in a home setting. All nine parents said they managed the technological aspect of remote learning, but teaching the students with their methods did not work. According to parents’ accounts, they believed that students were used to how their teachers taught them, which they said they could not replicate at home. As novice teachers, parents stated they struggled to understand why their children were not listening and accepting their teaching methods. Parents disclosed they were well educated and had the capabilities and knowledge to assist their children’s remote learning from home. The majority of parents had a diploma and a graduate degree. Unfortunately, they said the children were just unwilling to take teaching instructions from them. Parents stated they needed additional home support to assist their children’s remote learning.

Lack of home support during remote learning

School’s sudden closure and the resulting conversion of traditional classroom learning to distance learning did not allow parents to prepare for a teacher’s role (Letzel et al., 2020; Daniela et al., 2021). Therefore, parents desired additional home support to assist their children with remote learning. Duraku and Nagavci (2020) and Toquero (2020) suggested that parents with special needs children did not feel their children were fully included in distance learning planning during the COVID-19 pandemic, which too was echoed by parents in this study. For example, eight parents from this study stated they had no input on when their children would log on for remote learning. One parent said they were able to arrange a time with the teacher that works for them to ensure they were home to assist their child with remote learning. Results of this study also confirm what other studies have reported: that parents are vital sources to get rich information from to help plan distance learning programs for students with disabilities (Burdette and Greer, 2014; Bhamani et al., 2020; Duraku and Nagavci, 2020; Garbe et al., 2020; Koskela et al., 2020; Toquero, 2020). Parents wanted good communication, education assistants (EAs), and other educators for in-person home support, education materials, and technical assistance.

Good communication between teachers and parents

Parents from this study said they know their children better and how their children behave at home. Therefore, they said good communication with the teachers would have helped identify the strengths and weaknesses of these children in a home setting. Parents said this would have given them more say in planning their children’s remote learning. This result is confirmed in Averett’s (2021) study, which stated that good communication was lacking between parents and teachers, which would have helped parents’ experiences. Averett also noted that parents should be involved in planning students’ learning. However, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (2020) stated that placing such expectations on parents can cause extra burdens resulting from their little or no technical knowledge of remote learning. Manitoba educational authorities involved parents and guardians in their children’s remote learning by tasking them to monitor their children’s “engagement and completion of required independent work” during the remote learning period (Manitoba, 2021, p. 2). This study found that tasks given to children were challenging and needed parents to intervene. Daniela et al. (2021) reported similar findings whereby tasks assigned to students were too complex, and parents had to step in and help them complete the tasks.

Providing education assistants and other educators at home during remote learning

Parents in this study said they wanted home support, whereby a teacher or an Education Assistance (EA) would visit the child at home and provide them with some learning or activities. Two out of nine parents said individual teachers took it upon themselves to support their children at home. Six out of nine parents stated that sending a teacher or an EA, even for just a few hours a week, would have helped immensely with remote learning because their children have an EA in school and a one-to-one support system to assist with their learning. Parents said they wondered why this setup was not transferred to the homes during remote learning. According to parents’ accounts, teachers and EAs were asked to stay home during the school’s shutdown, while some EAs were let go from their jobs. Parents said taking up the teacher’s and EA’s roles brought significant tension between them and their students, causing students to refuse to learn from them.

In this study, occupational therapists, psychologists, and speech therapists were other in-person home support parents said could have been involved with remote learning. All nine parents reported that students had these services in school but were deprived of them during remote learning. Parents believed that involving these stakeholders in students’ remote learning at home would have helped control or mitigate the behavioral changes students had to endure. This study confirms what other studies have reported: that the quality of remote learning was poor and that parents received little support in assisting their children (Thorell et al., 2020; Averett, 2021).

A study by Averett (2021) stated similar findings that schools struggled to provide services and accommodations for students with individual education plans. Averett said parents reported disruptions to their children’s services during remote learning, such as “Speech and occupational therapy, one-on-one aids or para-professionals, or read-aloud services” (p. 6). Averett also stated in their report that some children’s services were stopped entirely. Parents in this study reported similar feedback about their children’s services.

Educational supplies for parents and remote learning outcome

In terms of materials, parents reported that, initially, during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, school support with educational materials was slow. However, they said they received more material support during the second and third pandemic waves. Parents acknowledged that the first wave took educators by surprise but stated that there was still a lack of preparedness for such events. This study suggested that remote learning was unsuccessful and unsuitable for children with special needs. Black et al. (2020) reported a similar outcome, and the United Nations (2020b) also echoed this finding by stating, “Children with disabilities are among those most dependent on face-to-face services…which have been suspended as part of social distancing and lockdown measures. They are least likely to benefit from distance learning solutions” (p. 12).

However, parents said that, even with school materials, they do not believe they have the teaching skills to teach their children with special needs. Parents thought they needed skills to teach children with special needs. Most of these children were in mainstream schools taking normal subjects that parents said were unfamiliar to them. The most challenging subject reported by parents was math. Parents reported that how they were taught math during their schooling differed from today’s teaching method. Therefore, they said they felt helpless because they could not help their children.

Eight out of nine parents in this study reported a negative experience with remote learning. This is in correlation with results from Thorell et al. (2020), who said, “Parents across Europe reported negative experiences for both themselves and their children” (p. 8). Averett (2021) also reported negative experiences by parents in their study. Nevertheless, one participant out of nine in this study reported a positive experience with remote learning. This finding is similar to that of Averett, who said some parents reported positive experiences.

The use of technology during remote learning

Parents in this study assisted their children’s remote learning because they said they had no choice with the COVID-19 induced homeschooling, a similar finding by other researchers such as Daniela et al. (2021), Garbe et al. (2020), Hakkila et al. (2020), and Widodo et al. (2020). Unlike reports from other studies that showed that most parents may have never used technology before and had no choice but to learn this skill in a short period to assist their children (Bubb and Jones, 2020; Letzel et al., 2020), this study showed that all participants were comfortable with the use of technology. The only concern reported by parents was uploading school materials or assignments to teachers using the school’s program. From parents’ accounts, this researcher noted that the lack of training and resources did not cause them frustration and stress, as reported in other studies such as Hakkila et al. (2020). Parents said they were fine once they knew how to operate the school’s program and upload assignments.

Implications

The implications of this study seem to suggest that there was poor communication between parents and teachers, and parents’ desire to be involved in planning remote learning for students with special needs during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown was not met. Parents from this study said they know their children better and how their children behave at home. Therefore, they said good communication with the teachers would have helped identify the strengths and weaknesses of these children in a home setting. Parents said this would have given them more say in planning their children’s remote learning.

A second implication suggests that schools failed to meet students’ IEPs during remote learning. Switching from face-to-face classroom education to online learning for students with IEPs caused inequities and a lack of proper access to education for these students. Students’ IEPs were created during face-to-face, in-person learning. The cancelation of face-to-face in-person learning forced schools to create specialized online education programs to meet students’ IEPs, which was unsuccessful.

Another implication of this study highlighted that remote learning for special-needs students is inappropriate without educational assistance. Parents said taking up the teacher’s and EA’s roles brought significant tension between them and their students, causing students to refuse to learn from them. Students have EAs in school to assist them with school activities, something they missed out on during remote learning from home. These implications also seem to follow recent research by Averett (2021) in the United States, which stated a lack of services and accommodations, disruptions to students’ IEPs, and serious challenges for students and parents during remote learning.

Recommendations

The findings of this study provide information through which school districts, teachers, and policy-makers could improve special needs students’ learning during a school lockdown. Given that parents struggled to assist their children with remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, this study suggests that parents desired modified in-person teaching methods other than remote learning for special needs students during a school lockdown in future pandemics. This study suggested that parents with special needs students receive some hours of in-person home support, for example, a teacher or an EA during a school lockdown. Other stakeholders, such as occupational therapists, speech therapists, and psychologists, are also desired by parents with special needs students to be involved with students’ remote learning during school lockdowns.

Parents stated they wanted to be involved in their children’s remote learning planning process. In light of the findings, communication between teachers and parents was inadequate; parents desired improved communication with school authorities. Finally, parents wanted teachers to provide a teaching template of methods and styles used in school for parents to teach their students remotely at home in a future school lockdown. This study suggests changes to school policies to provide services and accommodations at home for students with IEPs in future remote learning.

Limitations of the study

Although this qualitative descriptive study was conducted with honesty and integrity, some limitations could have affected the results. Therefore, these limitations should be considered when interpreting the study’s findings. Phenomenology research uses small sample sizes. Therefore, this methodology and the small sample size could limit this study. In addition, the sample for this study consisted of well-educated parents with access to technology and technological abilities. Using parents who are not well-educated and with little to no access to technological equipment and technical knowledge may have changed the results of this study. Also, using one research method and a single tool for data collection may have limited this study’s findings. Furthermore, this study only included parents who used remote learning for the first time. Including parents with prior knowledge of remote learning may have provided different results.

Recommendation for further research

Future research is recommended, given that the findings of this study cannot be generalized to other settings because of its sample size. Therefore, further research is recommended to further this qualitative descriptive study by addressing the limitations. Further research is needed using a different methodology and a larger sample size. The use of triangulation methods and different data collection methods, such as face-to-face interviews, is needed. Use different locations and larger school settings to ameliorate the limitations. Research should be conducted in an area with a more diverse population in terms of education. Further research is needed in the area of schools fulfilling students’ IEPs.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by William Howard Taft University, USA. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Aishworiya, R., and Kang, Y. (2021). Including children with developmental disabilities in the equation during this COVID-19 pandemic. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 51, 2155–2158. doi: 10.1007/s10803-020-04670-6

Averett, K. H. (2021). Remote learning, COVID-19, and children with disabilities. Am. Educ. Res. Assoc. Open 7, 1–12. doi: 10.1177/23328584211058471

Bhamani, S., Makhdoom, A. Z., Bharuchi, V., Ali, N., Kaleem, S., and Ahmed, D. (2020). Home learning in times of COVID: experiences of parents. J. Educ. Educ. Dev. 7, 9–26. doi: 10.22555/joeed.v7i1.3260

Black, E., Ferdig, R., and Thompson, L. A. (2020). K-12 virtual schooling, COVID-19, and student success. Am. Med. Assoc. 175, 119–120. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.3800

British Columbia (2016). Special education services: A manual of policies, procedures, and guidelines. Available at: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/education/administration/kindergarten-to-grade-12/inclusive/special_ed_policy_manual.pdf (Accessed April 6, 2021).

Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., et al. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 395, 912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8

Bubb, S., and Jones, M. A. (2020). Learning from the COVID-19 homeschooling experience: listening to pupils, parents/carers, and teachers. Improv. Sch. 23, 209–222. doi: 10.1177/1365480220958797

Burdette, P. J., and Greer, D. L. (2014). Online learning and students with disabilities: parent perspectives. J. Interact. Online Learn. 13, 67–88.

Cherry, K. (2020). Self-efficacy and why believing in yourself matters. Available at: https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-self-efficacy-2795954 (Accessed April 6, 2021).

Daniel, S. J. (2020). Education and the COVID-19 pandemic. Prospects 49, 91–96. doi: 10.1007/s11125-020-09464-3

Daniela, L., Rubene, Z., and Rudolfa, A. (2021). Parents’ perspectives on remote learning in the pandemic context. Sustainability 13, 1, 3640–12. doi: 10.3390/su13073640

Di Marino, E., Tremblay, S., Khetani, M., and Anaby, D. (2018). The effect of child, family, and environmental factors on the participation of young children with disabilities. Disabil. Health J. 11, 36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2017.05.005

Duraku, Z. H., and Nagavci, M. (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the education of children with disabilities. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/342282642_The _impact_of_the_COVID-19_pandemic_on_the_education_of_children_with_disabilities (Accessed March 17, 2021).

Education Profiles. (2020). Inclusion. Available at: https://education-profiles.org/europe-and-northern-america/canada/~inclusion (Accessed March, 17, 2021).

Fisher, J., Languilaire, J. C., Lawthom, R., Nieuwenhuis, R., Petts, R. J., Runswick-Cole, K., et al. (2020). Community, work, and family in times of COVID-19. Community Work Fam. 23, 247–252. doi: 10.1080/13668803.2020.1756568

Garbe, A., Ogurlu, U., Logan, N., and Cook, P. (2020). COVID-19 and remote learning: experiences of parents with children during the pandemic. Am. J. Qual. Res. 4, 45–65. doi: 10.29333/ajqr/8471

Goldschmidt, K. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic: technology use to support the well-being of children. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 53, 88–90. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2020.04.013

Hakkila, J., Karhu, M., Kalving, M., and Colley, A. (2020). Practical family challenges of remote schooling during COVID-19 pandemic in Finland. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344225531_Practical_Family_Challenges_of_Remote_Schooling_during_COVID-19_Pandemic_in_Finland (Accessed February 2, 2021).

Heuer, W., and Donovan, W. (2017). Homeschooling: The ultimate school choice. Available at: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED588847.pdf (Accessed Februay 3, 2021).

Homeschool.Today. (2020). Summary of homeschooling laws across Canada. Available at: https://homeschool.today/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/Summary-of-Home-Education-Laws-Across-Canada-05-2020.pdf (Accessed March 21, 2021).

Isaac, D. (2006). A qualitative descriptive study of nurses’ and hospital play specialists’ experiences on a children’s burn ward. Available at: https://openrepository.aut.ac.nz/handle/10292/262?show=full (Accessed January, 4, 2021).

Jamshed, S. (2014). Qualitative research method-interviewing and observation. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4194943/ (Accessed March 24, 2021).

Kalil, A., Mayer, S., and Shah, R. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 crisis on family dynamics in economically vulnerable households (working paper no. 2020-143). Available at: https://bfi.uchicago.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/BFI_WP_2020143.pdf (Accessed April 17, 2021).

Koskela, T., Pihlainen, K., Piispa-Hakala, S., Vornanen, R., and Hamalainen, J. (2020). Parents’ views on family resiliency in sustainable remote schooling during the COVID-19 outbreak in Finland. Sustainability 12:8844. doi: 10.3390/su12218844

Leonhardt, M.. (2020). Parents struggle with remote learning while working from home: ‘I’m constantly failing’. Available at: https://www.cnbc.com/2020/09/17/remote-learning-why-parents-feel-theyre-failing-with-back-to-school-from-home.html (Accessed June 17, 2021).

Letzel, V., Pozas, M., and Schneider, C. (2020). Energetic students stressed parents, and nervous teachers: a comprehensive exploration of inclusive homeschooling during the COVID-19 crisis. Open Educ. Stud. 2, 159–170. doi: 10.1515/edu-2020-0122

Manitoba. (2021). Manitoba education standards for remote learning. Available at: https://www.edu.gov.mb.ca/k12/covid/support/remote_learn_standards.html (Accessed June 11, 2021).

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2020). Strengthening online learning when schools are closed: the role of families and teachers in supporting students during the COVID-19 crisis. Available at: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/strengthening-online-learning-when-schools-are-closed-the-role-of-families-and-teachers-in-supporting-students-during-the-covid-19-crisis-c4ecba6c/ (Accessed January 9, 2021).

Owens, R. G., and Valesky, T. C. (2015). Organizational behavior in educational setting: Leadership and school reform (11th Edn). London: Pearson.

Patel, K. (2020). Mental health implications of COVID-19 on children with disabilities. Asian J. Psychiatr. 54, 102273–102272. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102273

Rose, J., Willner, P., Cooper, V., Langdon, P. E., Murphy, G. H., and Kroese, B. S. (2020). The effect on and experience of families with a member who has intellectual and developmental disabilities of the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK: developing an investigation. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 68, 234–236. doi: 10.1080/20473869.2020.1764257

Ryan, F., Coughlan, M., and Cronin, P. (2009). Interviewing in qualitative research: the one-to-one interview. Int. J. Ther. Rehabil. 16, 309–314. doi: 10.12968/ijtr.2009.16.6.42433

Smith, S. J., Burdette, P. J., Cheatham, G. A., and Harvey, S. P. (2016). Parental role and support for online learning of students with disabilities: a paradigm shift. J. Spec. Educ. Leadersh. 29, 101–112.

Speziale Streubert, H. J., and Carpenter, D. R. (2010). Qualitative Research in Nursing: Advancing the Humanistic Imperative (5th Edn). Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Thorell, L. B., Skoglund, C., de la Pena, A. G., Baeyens, D., Fuermaier, A. B. M., Groom, M. J., et al. (2020). Parental experiences of homeschooling during the COVID-19 pandemic: differences between seven European countries and between children with and without mental health conditions. Eur. Child. Adolesc. Psychiatry 31, 649–661. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01706-1

Toquero, C. M. D. (2020). Inclusion of people with disabilities amid COVID-19: Laws, interventions, recommendations. Multidiscipl. J. Educ. Res. 10, 158–177. doi: 10.4471/remie.2020.5877

United Nations. (2020a). Policy brief: education during COVID-19 and beyond. Available at: https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2020/08/sg _policy_brief_covid-19_and_education_august_2020.pdf (Accessed February 19, 2021).

United Nations (2020b). Policy brief: The impact of COVID-19 on children. Available at: https://unsdg.un.org/sites/default/files/2020-04/160420_Covid_Children_Policy_Brief.pdf (Accessed February 19, 2021).

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (2020). Distance learning strategies in response to COVID-19 school closures. Available at: Distance learning strategies in response to COVID-19 school closures - UNESCO Digital Library (Accessed February 19, 2021).

Vasileiou, K., Barnett, J., Thorpe, S., and Young, T. (2018). Characterizing and justifying sample size sufficiency in interviewed-based studies: systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 18:148. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0594-7

Villano, M. (2020). Students With Special Needs Face Virtual Learning Challenges. CNN.com

Widodo, S. F. A., Wibowo, Y. E., and Wagiran, W. (2020). Online learning readiness during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1700, 012033–012034. doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/1700/1/012033/pdf

Wojnar, D. M., and Swanson, K. M. (2007). Phenomenology: an exploration. J. Holist. Nurs. 25, 172–180. doi: 10.1177/0898010106295172

Yin, L. C., Zakaria, A. R., and Baharun, H. (2016). Homeschooling: An alternative to mainstream. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309126591_HOMESCHOOLING_AN_ALTERNATIVE_TO_MAINSTREAM (Accessed June 17, 2021).

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, disability, remote learning, special needs students, technology

Citation: Sankoh A, Hogle J, Payton M and Ledbetter K (2023) Evaluating parental experiences in using technology for remote learning to teach students with special needs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Educ. 8:1053590. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1053590

Edited by:

Kristina Rios, California State University, Fresno, United StatesReviewed by:

Pitambar Paudel, Tribhuvan University, NepalLieke Van Heumen, University of Illinois at Chicago, United States

Janeth Aleman Tovar, California State University, Chico, United States