- Department of Humanities, University of Trieste, Trieste, Italy

The European guidelines and orientation in recent years have been focus on the promotion of equity in the learning paths and in the counteract early school leaving. Although many actions to reduce early school leaving have been implemented, today there remain many students who fail to achieve satisfactory school outcomes and who leave the school system early, especially among students with a migrant background. To understand the dynamics that can lead students in conditions of fragility toward negative educational paths, it is necessary to employ a complex and multidimensional analytical framework that considers the multiple variables involved. The ecological and cultural theoretical model of development highlights the complexity of the factors that can influence students’ learning trajectories, assuming a systemic and multifactorial interpretative approach. Starting from these premises, this study aims to explore the impact of individual and contextual factors in the learning pathways of foreign-born students, taking the students’ perspective. Two hundred and forty-four students attending the second level of secondary school answered to a survey, which explores their perception about: the meaning attributed to the school; the role of teachers and the family in supporting their learning path; their involvement in extra scholastic activities. The results highlight the inclusive role play by the school, which represent a place for integration into the community for foreign students; the central role of relationship with teachers and the emotional support received by the family, in counteracting early school living; the participation of students with a migratory background in their extra scholastic activities as element of protection. The results suggest that to respond to foreign students’ complex educational needs, school cannot act as an isolated entity, but rather should build networks that involve families and external contexts.

1. Introduction

The need to promote equity during learning paths and to counteract early school leaving, are key topics that have informed the political debate around and orientation of European guidelines in recent years. Already in 2020, European Union strategies included, among their main objectives, the reduction of early school leaving in its constituent countries (European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice, 2013, 2020). European policies have therefore attempted to promote actions to make learning paths equitable and inclusive, in order to support students most at risk and encourage training actions that could enhance everyone’s skills. Within this perspective, learning is interpreted as a path that accompanies the individual’s life and which should develop transversal skills, intertwining formal and informal knowledge that is transferable to different contexts. The European Commission has also identified some key factors that should be considered in order to implement actions to reduce risk. These actions should be developed through a complex and systemic approach, considering the multiplicity of factors that can affect learning paths, for example: considering flexible and individualized learning paths that can respond to everyone’s needs and requirements; involving families and social contexts; and identifying risk situations and supporting motivation also through appropriate orientation paths.

Although Europe has committed to concrete actions to reduce early school leaving, today there remain many students who fail to achieve satisfactory school outcomes and who leave the school system early. Among this segment of the population, students with a migrant background represent a group particularly at risk of drop out – as highlighted by the data published by the Ministry of Education, University and Research in Italy (MIUR – Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca, 2019). These students achieve lower academic results than Italian students and present a higher dropout rate (10.5%, versus 3.3% for students with Italian citizenship). The factors that place these students in a condition of greater vulnerability are many and attributable to individual aspects that characterize the path of growth and adaptation in the reception contexts of children with migratory origins, and to contextual variables that affect their learning experience at different levels (Suárez-Orozco et al., 2018). These risk factors can have a negative impacts on learning pathways, as well as determinate conditions of low participation in school activities and less satisfactory learning outcomes.

Furthermore, a survey conducted by Save de children in Italy (2021) revealed an increase of drop out for 34,000 high school students, highlighting a negative trend especially for those who were already at risk of abandonment after the introduction of distance learning during the Covid pandemic. The survey therefore highlights a growth in educational inequalities to the detriment of the most vulnerable segment of the population, which has produced a higher risk of early school leaving and failure. Thus, working to ensure equity in learning paths must be an absolutely priority: the Council of Europe (2020) has in fact recognized this goal as one of the main current challenges, in order to guarantee equal learning and participation opportunities for all students. Ensuring equity in learning paths means promoting social justice and working to achieve educational equality in terms of inclusion.

The issue of equity is addressed in the Eurydice report (2020), which analyzes the educational structures and policies that influence learning paths in 42 European countries. The Eurydice report emphasizes how pursuing equity means aiming to overcome potential obstacles and disadvantaged conditions, to ensure they do not impede anyone’s capacity to achieve their educational potential. In fact, students who achieve low school outcomes acquire inadequate skills and knowledge that could constrain their ability to achieve their future projects and reduce the likelihood that they will pursue a prosperous and healthy life path. Guaranteeing equity means offering equal opportunities and therefore creating learning paths, in which all students can be enabled to participate, regardless of their background of origin.

Eurydice also highlights that in order to pursue this goal, a systemic analysis of the problem is needed. Moreover, the multiplicity of factors that can intervene in a positive sense, should be identified to support the learning paths of the most vulnerable students at different levels, such as: participation in early childhood education paths; the support given to students with low outcomes; the opportunities offered by the context; and macro factors linked to education policies and structures.

2. Learning paths of students with a migratory background

Foreign-born students are exposed to a greater risk of scholastic failure and present a higher rate of early school leaving, due to a complex set of factors that place them in a vulnerable condition (Suarez-Orozco et al., 2011; Colombo and Santagati, 2014; Catarci and Fiorucci, 2015; Bembich and Sorzio, 2021).

Suárez-Orozco et al. (2018) proposed a theoretical model to understand the growth and learning path of migrant youth, starting from the ecological and cultural perspective proposed by the bioecological model of development (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2007), and integrating it with theoretical frameworks that analyze different aspects related to the adaptation process (Masten, 2014; Motti-Stefanidi and Masten, 2017; Suárez-Orozco, 2017).

According to the model proposed by Suárez-Orozco, the path of growth and adaptation in the receiving contexts of pupils with a migratory background, involves three fundamental aspects: the development tasks; the path of psychological adaptation that young people must undergo; and the tasks of “acculturation.” These indices are closely linked to each other and contribute to determinate the differences in the adaptation processes. The links between acculturative tasks, development tasks and well-being, are of particular interest for understanding the differences in the growth and development paths of these young people (Motti-Stefanidi and Masten, 2017).

Moreover, Suárez-Orozco highlight how the paths of children with a migratory history, are also influenced by contextual variables that affect their learning experience at different levels: the microsystems in which they have direct experience (such as school, family, community); the political and social aspects of the receiving community that influence the possibilities of inclusion and integration of immigrant families, both in the short term and in long-term development paths; and, finally, the global context that influences the economic, geopolitical and social dynamics in the world, that have implications for the migratory phenomenon.

Suárez-Orozco also highlighted how some aspects related to the life path of foreign students should be considered. For many students, the migratory experience is traumatic that involves separation from their families of origin, with deep emotional and affective implications. They are also asked to become part of a new life context, to adapt to it and to negotiate the demands of the receiving community with the cultural and social models of their family of origin (which can also diverge considerably).

Although young people with a migratory background face similar critical conditions, they can nevertheless undertake very different educational paths and in some circumstances be able to achieve good learning outcomes, despite the adversities encountered (Suárez-Orozco et al., 2010). In fact, by analyzing the educational paths of these students, the researchers highlighted how much school and family impact on their learning trajectories.

Therefore, although the influence of the broader macrosystems (linked both to the contexts of origin and to those of reception) play an important role in the learning experience of foreign-born children, it is the contextual aspects linked to the school and the family, that represent central supporting mechanisms for achieving good academic results.

3. The aim

Starting from these premises, this study aims to explore the impact of individual and contextual factors in the learning pathways of foreign-born students, using a systemic and multi-factorial model of analysis.

The study was developed as part of the FAMI-IMPACT FVG 2018–2020 project, funded from 2014–2020 – OS2 Migration and Integration Asylum Fund. The project was carried out in collaboration with the University of Trieste and the University of Udine with the proponent Friuli Venezia Giulia Region, to promote research and teacher training to counteract early school leaving, especially in foreign students.

The research group is part of the CIMCS-Interdepartmental Center of the University of Trieste on “Migration and International Cooperation for Sustainable Development,” which operates in connection with the main international research networks, with public and private institutions, stakeholders, with the aim of promoting, developing and carrying out research projects concerning international cooperation and migration.

We have tried to involve in the research activities a sample of schools as representative as possible of the different territorial contexts and of the different types of schools. The schools joined the project by signing a research protocol, which defined the different phases of research: the first phase included the collection of data through a questionnaire; the second phase an action research with interested teachers. Anonymity, informed consent and the protection of sensitive and personal data are guaranteed in accordance with Legislative Decree nr. 196 of 30 June 2003, “Code regarding the protection of personal data” and the research ethics code established University of Trieste.1

In the first stage of the project, an exploratory survey was developed with the aim to analyze the risk factors related to school failure in students attending first and second grade of secondary schools.

The research methodology centered students’ participation in the research path (Mason and Hood, 2010). Taking the students’ perspective has meant listening to their perspectives and considering them as active participants in a process of school transformation.

The inclusion of students in the course of the research, acts to stimulate reflection on practices and policies, in order to identify interventions that are truly meaningful and responsive to their needs. In this way, it is possible to look at the world experienced by children and highlight aspects that may escape external observation. Indeed, the perceptions of teachers and adults can be very distant from that of students, leading to erroneous interpretations.

Listening to students in their own words, is critical for understanding the factors that hinder their ability to achieve positive school results: it is a question of understanding how they build their experience at school and what they consider influential in their path. Considering students’ point of view, means developing a different vision on school which is able to understand how they conceive of the institution, how they seize the opportunities offered to them, and where they identify the greatest challenges (Danby and Farrell, 2005).

4. Method

4.1. The survey

In accordance with the objectives of this project, a questionnaire was developed to explore the risk factors associated with the school failure of students in secondary schools in a region of north eastern Italy (Friuli Venezia Giulia). The questionnaire explored different sets of factors attributable to the risk of school failure through use of closed items (Likert scale from 0 to 4) and open questions - and required online completion. For the purposes of this work, the analysis will focus on students attending the second stage of secondary school.

The perception of the students was explored using a systemic analytical perspective, and considering the following factors:

a. Meaning attributed to the school (open question): the students were asked to explain what was the meaning they attributed to the school in their life path;

b. Role of teachers in supporting the learning path (close question): students were asked how teachers could help them improve their academic achievements (clearly explaining the aspects that will be assessed; dialoguing with students; intervening in the management of conflicts in the classroom; using forms of collaborative learning between students);

c. Role of the family in supporting the learning path (close question): students were asked how their families could help them improve their academic achievements [communicating frequently with teachers; giving practical support in learning (such as supporting the student in homework, buying school materials, etc.); giving emotional support; possessing positive expectations regarding the competence of their children];

d. The involvement of students in extra scholastic activities (open question): students were asked whether in the last year they had participated in extracurricular cultural activities (such as museum, theater or cinema visits), or in artistic activities (such as dance, sing, draw, etc.) or sports activities.

4.2. The participants

The survey involved a total of 244 students attending the second level of secondary school.

According to the data published by the Ministry of Education, University and Research (MIUR – Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca, 2019), in Friuli Venezia Giulia region students with non-Italian citizenship are slightly higher than the national average: 19.107, with an incidence of 12% in relation to the total number of students in the region. Of these, 12.039 (63%) were born in Italy, with a distribution among the various school levels in line with national data. This local context reflects the international situation, where is observed a global increase in the number of migrants, of which 14% are under 20 years old (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2017a,b).

The survey was aimed at students under the age of 18 years (mean age = 16, 27; SD = 0.74; female students = 61.1%; students = 35.5%; undeclared sex = 1.4%). The secondary schools involved were gymnasium, technical and professional institutes, and vocational training institutes. We have tried to give priority to the identification of schools with a high rate of foreign students. The sample of the schools includes different scholastic, territorial, and socio-economic contexts.

In the general sample, 11.3% of student participants had a migratory background (MB),2 10.6% came from third countries (TC), while 78% arrived from countries of the European Community (UE).3

The distribution of student with migratory background and coming from third is as follows:

• in gymnasium: 33.4% MB; 23.3% TC;

• technical and professional institutes: 45.5% MB; 20% TC;

• vocational training institutes: 21.2% MB; 56.7% TC.

Third country students hailed from: Kosovo (16.3%), Macedonia (11.3%), and Serbia (27.5%). Among students with a migratory background, there was a higher percentage of families from Albania (13%), Kosovo (14.7%), and Serbia (14.7%).

4.3. Data analysis

The study assumed as independent variables in the data analysis, the variable “Background of origin” of the students [students from Third Countries (TC); with migratory Background (MB); with Italian citizenship or belonging to the European Community (EU)].

With regard to the analysis of open questions, the coding provided for the reading of the statements in free form manner and the construction of a taxonomy from students’ answers, then grouped into homogeneous conceptual areas. The number of detected occurrences was calculated for each identified category, and the distribution percentage of the main categories (those with a frequency of 4 or greater were calculated.)4

4.4. Results

4.4.1. Meaning attributed to the school

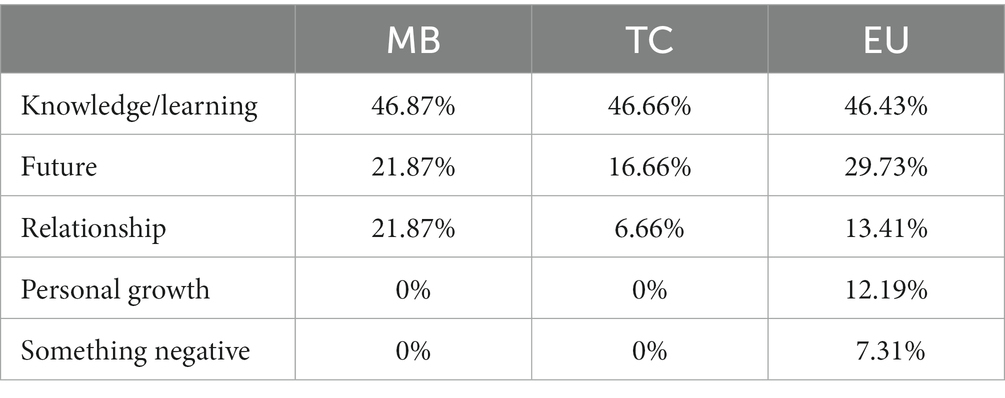

The open-ended answers given by the students, were classified and the following conceptual categories were identified: knowledge/learning; future; relationship; personal growth; something negative (Table 1).

For most students, school is considered a place to acquire new knowledge and learn (MB = 46.87%; TC = 46.66%; EU = 46.43%); this aspect is recognized by the majority of students as a priority, even if it remains a generic concept and not attributed to specific factors of the school career:

“A place where you can broaden your culture in general, have comparisons and where we can learn to express ourselves” (MB).

"It's a place where you learn" (TC).

"It is a place where you learn how to learn" (EU).

Students also mentioned the school represents an opportunity to learn and acquire competences for the future – they emphasize the importance of a diploma for finding a job, especially students with MB e form EU; on the other hand, only 16.66% of students from TC perceive school as an opportunity for their future career (MB = 21.87%; TC = 16.66%; EU = 29.73%):

"It is a place where you learn things that you will need later; it will help me a lot to socialize, it will help me to find a job" (MB).

"School for me is the place where I learn to live for a future" (TC).

"Place that prepares us to face the world of work" (EU).

The importance of the school as a place to develop social skills was highlighted above all by students with a migratory background: they emphasized how they considered it an opportunity to integrate into the social context. Moreover, the relational aspects seem less important for the students from Third Countries, that highlighted the importance of the linguistic aspect as a starting point for building relationships. Finally, EU students see school as a place to socialize (MB = 21.87%; TC = 6.66%; EU = 13.41%):

"A place where you learn to live with other people and where you learn how to overcome the obstacles of life"; "A chance to integrate" (MB).

"I want learning Italian languages...learn to be with others" (TC).

“Learn to socialize with others” (EU).

Only EU students highlighted how school is a place where you can experience personal growth and acquire transversal competences, as the ability to stay and collaborate in a social context and to use the critical thinking. These aspects are not recognized as significant by students with BM and coming from TC (MB = 0%; TC = 0%; EU = 12.19%):

"School is necessary for the development of our person, from a social and personal point of view."

"School is a way of improving oneself and understanding how the world works, as well as learning useful things and the capacity for critical thinking" (EU).

Finally, for some EU students, school has a negative connotation: it is a place in which they experience anxiety, stress and relational difficulties (MB = 0%; TC = 0%; EU = 7.31%):

"It gives me anxiety...trouble, stress, anxiety, fear" (EU).

4.4.2. Role of teachers in supporting the learning path

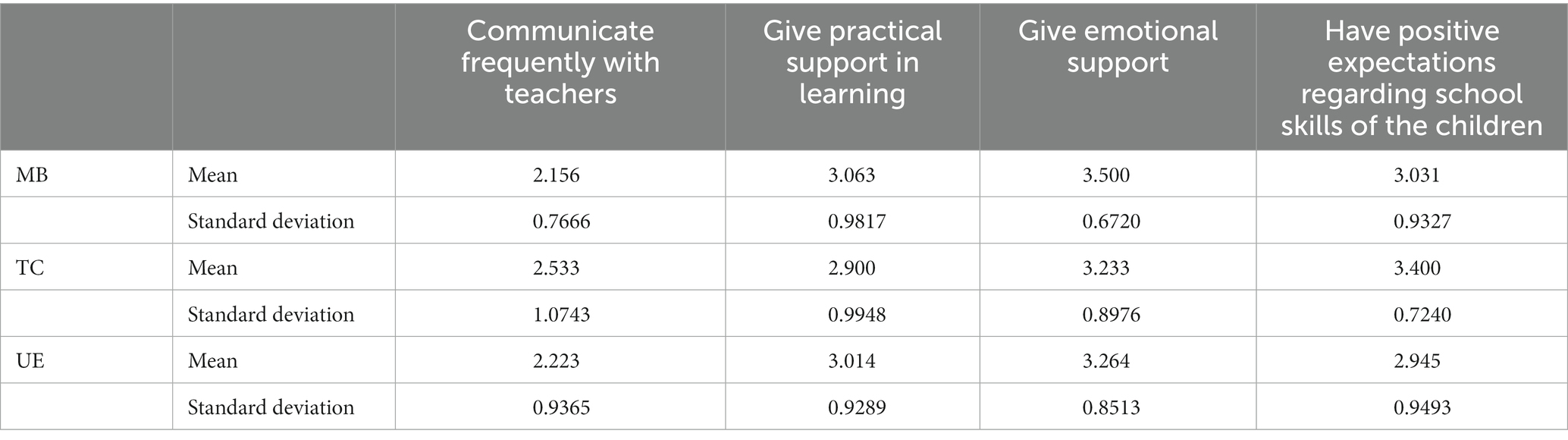

The question is composed of closed elements (Likert scale from 0 = not at all, to 4 = a lot). In general, students consider dialogue with teachers to be particularly significant in supporting the learning path and the use of collaborative forms of learning (Table 2). For MB students, it emerged that it was more important that teachers clearly explain the aspects that will be assessed (F (2, 279) = 3.049; p = 0.049)5, while for TC students it was considered more important that teachers intervene in the management of conflicts in the classroom (F (2, 279) = 3.925; p = 0.021).

4.4.3. Role of the family

The question is composed of closed elements (Likert scale from 0 = not at all, to 4 = a lot). In general, students considered it important to receive emotional support from their family; receiving practical support also seems to be considered quite important. On the other hand, it seemed that communication between school and family is an aspect considered less significant (Table 3). Especially for TC students, positive expectations from the family seem to assume a particularly relevance [F(2, 279) = 3.193: p = 0.043].

4.4.4. Involvement of students in extra scholastic activities

4.4.4.1. Cultural activities

4.4.4.1.1. Theater

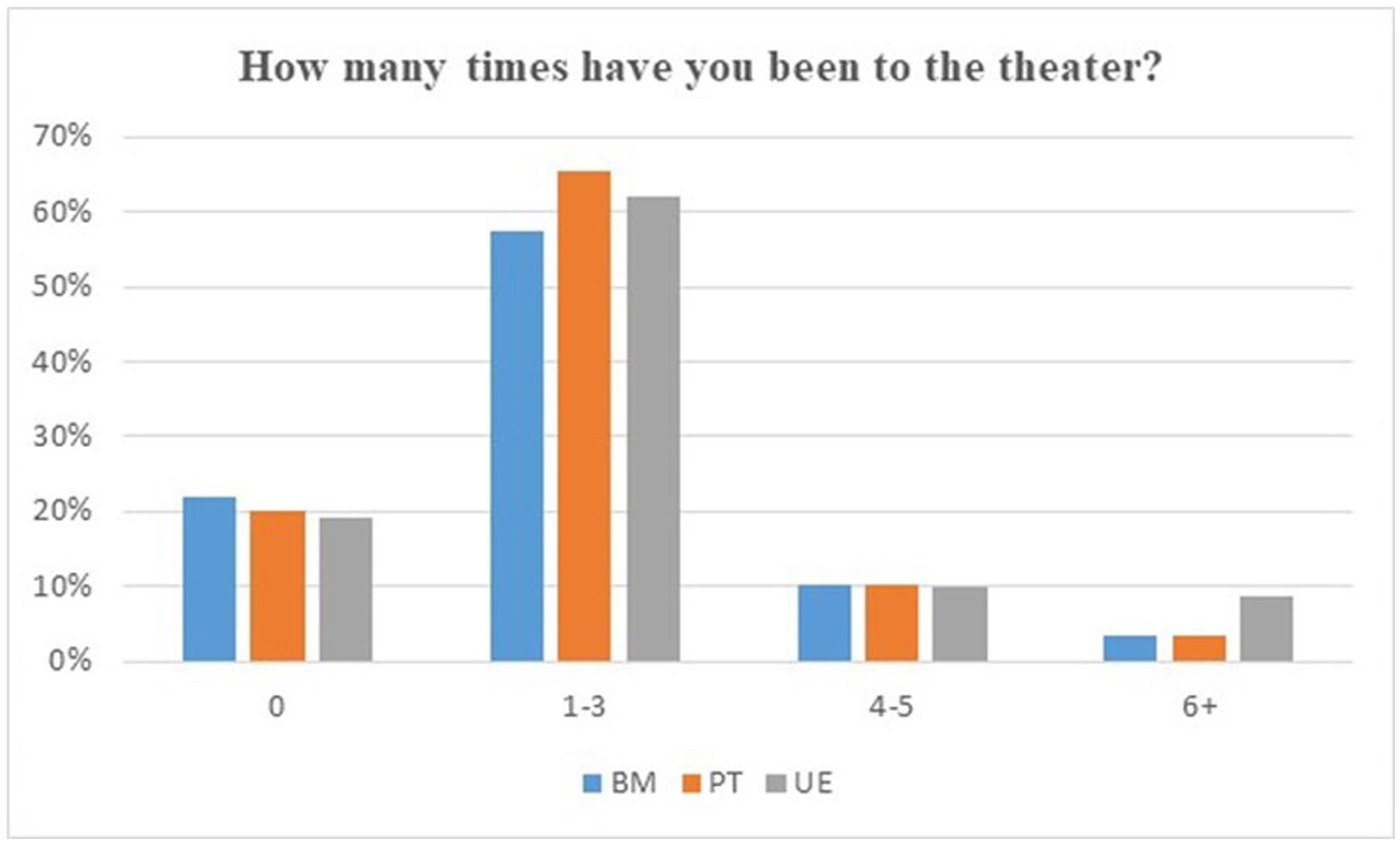

The students were asked how many times in a year they had been to the theatre; the responses were categorized by considering the reported frequencies: (0; from 1 to 3 times; from 4 to 5; more than 6).

About 20% of the students has never been to the theater during the last year; most declared to have visited there 1–3 times as an activity mainly organized by the school (Graph 1). While 6.83% of the MB students did not give a categorizable response (“do not know/do not remember”).

4.4.4.1.2. Museum

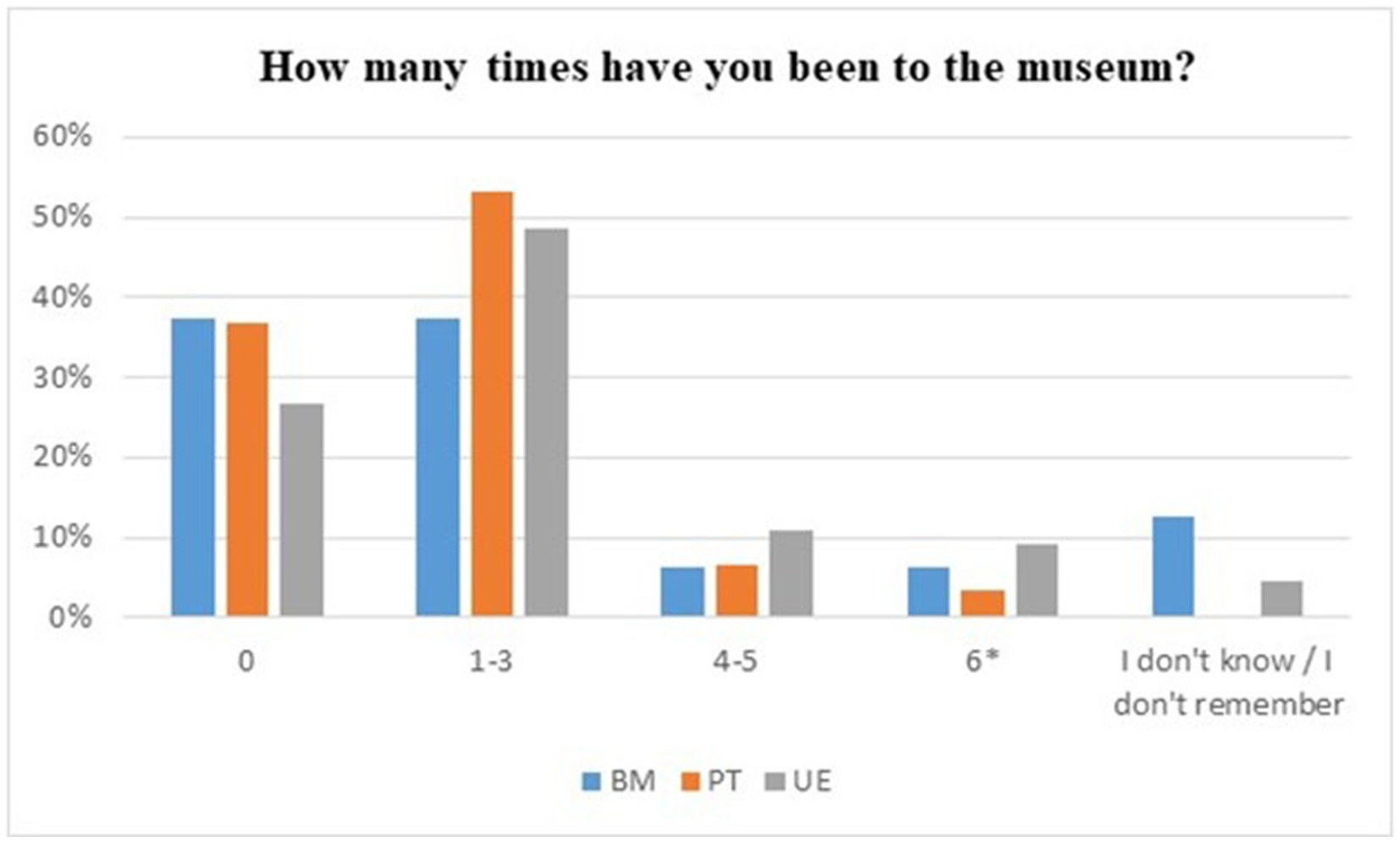

The students were asked how many times in a year they had been to the museum; the responses were categorized by considering the reported frequencies: (0; from 1 to 3 times; from 4 to 5; more than 6).

About 30% of students have never been to the museum in the last year. Most declared they had been between 1 and 3 times, mostly as an organized school activity (Graph 2).

4.4.4.2. Artistic activities

32.26% of MB students and 36.67% TC students reported that they are engaged in artistic activities (such as singing, drawing and dancing), many of which are carried out as informal activities at home or with groups of friends. 48.18% of EU students who declared that they dedicate themselves to this kind of activity, do so mostly through structured courses and at extracurricular facilities.

4.4.4.3. Sports activities

Many students declared that they carry out sporting activities, even if the highest percentage was found among EU students – 53.13% (MB); 50% (TC); 69.55% (EU).

5. Discussion

The results highlight that for most students, the school represents “the place of knowledge and learning”; many declare it is as a place “where one learns” and where one’s culture is expanded. In general, for students the meaning attributed to school seems to remain primarily anchored to an expansion of knowledge and information; a conceptual knowledge that is acquired and gradually fills their cultural horizon. Students recognize a broader value of the meaning of learning only partially: in fact, some emphasized how through school they can improve their ability to express and reason, while others indicated that they “are learning to learn.” Only EU students declared that for them, the school represents a place where they can grow personally and develop critical thinking. The development of these transversal competences therefore does not seem to be recognized by MB and TC students, as a significant aspect in their school career. This perception could affect in negative way the learning path of these students: in fact, the attitudes toward the experience at school and expectations about the opportunities for the future offered by the school are considered elements that influence the scholastic outcome (Dweck, 2006; Dweck et al., 2014).

Students with MB, highlight other factors significant to them, such as the possibility of integrating into the social context through the school, as well as acquiring language skills that allow them to communicate and participate in school activities and in the external environment. The value given to school for this segment of the population is therefore related to their particular needs: the school is perceived as an opportunity to facilitate the process of inclusion and can support them in integrating into the social fabric. This data is in line with Suárez-Orozco et al. (2018), who underline how the path of growth in the receiving contexts of pupils with a migratory background, involves social and relational aspects. The path of adaptation passes through the acquisition of skills relating to the different cultural repertoires: a negotiation process that should integrate the demands of the new life context and the cultural and social models of the family of origin.

In general, the students also emphasized how much school means for their future and the possibility of finding a job. They believed that school can provide an opportunity to prepare them for their future life. In students’ perceptions, there is a strong link between school and the labor market: through the school they expected to acquire knowledge that will serve them when entering the workplace. However, there was low awareness that learning actually represents a continuous path, which does not end with obtaining a diploma, but rather will accompany all professional growth. This data can be interpreted both in terms of expectations on schooling, or on the “dissonance” between the ways of thinking and learning at school and in the contexts of extracurricular experience: it could reflect a lack of a study method (which does not allow to appreciate the cognitive and metacognitive aspects of learning) and consequently on the transferability in the school context, of the reflective and metacognitive skills learned in the extra-school context (Mehan, 1991, 1998).

Finally, for some, school has negative connotations where aspects of discomfort, anxiety and relational difficulties seem to prevail. The literature highlights, that often young people experience emotional distress and negative moods, making them vulnerable and at risk of academic failure (Thompson and Tawell, 2017).

With respect to the role of teachers, it emerged that it is above all the relational aspect that is considered fundamental for students: the possibility to have an open dialogue was articulated as a central aspect in learning paths. Other considerations such as clarity in evaluative aspects and conflict management, were considered more important by MB and TC students. This perception could derive from the greater difficulties these students may face in understanding the functioning of the host school context and in establishing relationships with peers. The quality of the relationship between students and teachers is strictly correlated with academic outcome and also with students’ future learning orientations: the social and emotional experiences in the classroom, represent an element that affects individual future expectations and the investment that student make in school (Taylor et al., 2017).

In addition, students considered receiving emotional support from their family, as a significant factor in achieving academic success. Furthermore, for TC students, family expectations are critical; for many of these students, school represents an opportunity that their family has not had, and can provide the possibility for having a better future than that of their parents. Family expectations therefore seem to shape this segment of the population more extensively, and for them represent an element that can affect school results (Li and Xie, 2020). The literature suggest that low level of family involvement is linked with low school outcome of foreign students, by contrast higher involvement correlate with good achievement (Henderson and Mapp, 2002).

Finally, considering participation in activities outside the school, it was found that participation in cultural activities is generally low; for many students these activities are linked to educational projects formalized by the school. Therefore, the importance of the school seems to be realized in creating opportunities for participation in cultural activities, that would otherwise not be enjoyed by students.

As for the artistic activities, it emerged that it is mostly the EU pupils who practice them within formal contexts, while the MB and TC students carry them out at home or with friends. Moreover, even if a good percentage of students declare they play sports, it is still EU students who practice them in greater numbers. It therefore appears that MB and TC students are less engaged in structured extracurricular activities and in formal contexts than their peers. In fact, attending extracurricular activities could represent a positive aspect for them, that could improve their relationships within their context and broaden their range of experiences. Longitudinal data present in the literature confirm the protective function exercised by participation in extra-curricular activities for vulnerable children (Mahoney, 2014). After-school activities can concern various projects, supervised and guided by qualified adults, which must be structured in a targeted way and aimed at developing specific skills (Durlak and Weissberg, 2007).

6. Conclusion

Guaranteeing equity in learning paths means promoting actions that can support the students most at risk, considering the plurality of factors that can affect their school career. The ecological-cultural approach highlights how aspects of individual fragility, should be considered in relation to the contextual aspects and the opportunities offered by the social environment (Bronfenbrenner and Morris, 2007). In fact, early school leaving is a process structured over time, which derives from a series of experiences and factors that progressively increase situations of vulnerability and initial disadvantage.

The results of this work highlight how students build their own internal representation of the school, and attribute a particular meaning to the learning experience in relation to their expectations and personal experience. Foreign students declared that school represents for them a possibility for inclusion: a place where they can build relationships that support their integration into the community. This perception reflects the particular social condition of these students and their personal life’s experience. Therefore, considering the implication of personal aspects means reading them in a complex way, understanding that they are strongly linked to the personal history, the lived experiences and to current needs.

Moreover, factors related to the relationship with teachers and the emotional support received by the family, must be considered as central in counteracting early school living. It is important to consider the way the relationship between students and teachers develop in the school context: this is a factor that affects how students perceive closeness; help and interest from others; a sense of belonging; fairness in the application of the rules; mutual respect; and participation in the decision-making process. The relationship constitutes a protective factor, where the teacher manages to create positive relationships by showing, encouraging and responding (Pianta, 1999; Hamre and Pianta, 2006).

In the family context, on the other hand, it is the emotional support received (rather than practical support), that is considered by the students as particularly significant. Especially for students at high risk of school failure this aspect represents an important protective element: when the family plays an active role in the children’s learning paths, stimulates their participation in organized activities, monitors and controls the path of learning, and intervenes to help when needed (Siraj and Mayo, 2014).

Finally, factors external to the family and school should also be considered: indeed, participation of students in their wider social context could be an element of protection. The results highlight how the participation of students with a migratory background in the context outside the school seem to be weaker than their peers, because they are less involved into structured extra-scholastic activities.

Research highlights how relational networks built with the external context, can support at risk students and reduce the probability that vulnerable children turn to early school leaving (Mahoney, 2014). Within these activities, pupils can experiment with new ways of relating, expand motivation and rediscover a meaningful connection with school, supported by positive social relationships with peers and adults (Mahoney et al., 2005).

In conclusion, students with a migratory background, often have to face significant challenges and difficulties in their growth path that can impede their ability to achieve positive school outcomes. To respond to these complex educational needs, the school cannot act as an isolated entity, but rather should build networks that involve families and external contexts, while being aware that growth and training paths are complex and multifactorial processes.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian/next of kin.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^https://www.units.it/ricerca/etica-della-ricerca

2. ^The project indicators define this category of beneficiaries as: "Students who have Italian citizenship or citizenship of another EU country, but who have at least one parent who has immigrated to Italy from a non-EU country."

3. ^This category includes students from Italy and a small percentage from other European Community countries.

4. ^Cohen’s Kappa (1960, 1968) was used to assess coder reliability. During the coding of the data, 20% of the responses were independently coded by two coders. Reliability coefficients were computed, and reliability for both codes were acceptable (K > 0.70).

5. ^Anova corrected by Welch and post-doc Games–Howell for non-homogeneous variance.

References

Bembich, C., and Sorzio, P. (2021). Minority students at risk of drop out and the value they attribute to schooling. In INTED2020 proceedings, IATED Academy, 8237–8240.

Bronfenbrenner, U., and Morris, P. A. (2007). The bioecological model of human development. Handbook of child psychology. New York: Wiley.

Catarci, M., and Fiorucci, M. (2015). Intercultural education in the European context: Theories, experiences, challenges. Farnham, Surrey & Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and psychological measurement. 20, 37–46.

Cohen, J. (1968). Weighted kappa: nominal scale agreement provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychological bulletin. 70:213.

Colombo, M., and Santagati, M. (2014). Nelle scuole plurali. Misure di integrazione degli alunni stranieri. Milano, Franco Angeli

Danby, S., and Farrell, A. (2005). “Opening the research conversation,” in Ethical research with children. ed. A. Farrell (Milton Keynes: Open University Press), 49–67.

Durlak, J. A., and Weissberg, R. P. (2007). The impact of after-school programs that promote personal and social skills. Chicago: Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning.

Dweck, C. S., Walton, G. M., and Cohen, G. L. (2014). Academic tenacity: Mindsets and skills that promote long-term learning Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice (2013). Education and training in Europe 2020: Responses from the EU member states. Eurydice Report. Brussels: Eurydice.

European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice (2020). Equity in school education in Europe: Structures, policies and student performance. Eurydice report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

Hamre, B. K., and Pianta, R. C. (2006). “Student-teacher relationships,” in Children's needs III: Development, prevention, and intervention. eds. G. G. Bear and K. M. Minke (National Association of School Psychologists), 59–71.

Henderson, A., and Mapp, K. (2002). A new wave of evidence: The impact of school, family, and community connections on student achievement. Austin, TX: Southwest Educational Laboratory.

Li, W., and Xie, Y. (2020). The influence of family background on educational expectations: a comparative study. Chin. Sociol. Rev. 52, 269–294. doi: 10.1080/21620555.2020.1738917

Mahoney, J. L. (2014). School extracurricular activity participation and early school dropout: A mixed-method study of the role of peer social networks. J. Educ. Develop. Psychol. 4, 143–154. doi: 10.5539/jedp.v4n1p143

Mahoney, J. L., Lord, H., and Carryl, E. (2005). An ecological analysis of after-school program participation and the development of academic performance and motivational attributes for disadvantaged children. Child Dev. 76, 811–825. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00879.x

Mason, J., and Hood, S. (2010). Exploring issues of children and actors in social research. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 33, 490–495. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.05.011

Mehan, H. (1991). “The school's work of sorting students,” in Talk and social structure: Studies in ethnomethodology and conversation analysis. eds. D. Boden and D. H. Zimmerman (Cambridge: Polity Press), 71–90.

Mehan, H. (1998). The study of social interaction in educational settings: accomplishments and unresolved issues. Hum. Dev. 41, 245–269. doi: 10.1159/000022586

MIUR – Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca (2019). La dispersione scolastica nell’anno scolastico 2016/2017 e nel passaggio all’anno scolastico 2017/2018. Available at: https://miur.gov.it/pubblicazioni.

Motti-Stefanidi, F., and Masten, A. S. (2017). “A resilience perspective on immigrant youth adaptation and development,” in Handbook on positive development of minority children and youth. eds. N. J. Cabrera and B. Leyendecker (Springer science: Business media), 19–34.

Pianta, R. C. (1999). Enhancing relationships between children and teachers. Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

Siraj, I., and Mayo, A. (2014). Social class and educational inequality: The impact of parents and schools. Cambridge: University Press

Suárez-Orozco, C. (2017). Conferring disadvantage: behavioral and developmental implications for children growing up in the shadow of undocumented immigration status. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 38, 424–428. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0000000000000462

Suarez-Orozco, M., Darbes, T., Dias, S. I., and Sutin, M. (2011). Migration and schooling. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 40, 311–328. doi: 10.1146/annurev-anthro-111009-115928

Suárez-Orozco, C., Gaytán, F. X., Bang, H. J., Pakes, J., O'Connor, E., and Rhodes, J. (2010). Academic trajectories of newcomer immigrant youth. Dev. Psychol. 46, 602–618. doi: 10.1037/a0018201

Suárez-Orozco, C., Motti-Stefanidi, F., Marks, A., and Katsiaficas, D. (2018). An integrative risk and resilience model for understanding the adaptation of immigrant-origin children and youth. Am. Psychol. 73, 781–796. doi: 10.1037/amp0000265

Taylor, R. D., Oberle, E., Durlak, J. A., and Weissberg, R. P. (2017). Promoting positive youth development through school-based social and emotional learning interventions: A meta-analysis of follow-up effects. Child Dev. 88, 1156–1171. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12864

Thompson, I., and Tawell, A. (2017). Becoming other: social and emotional development through the creative arts for young people with behavioural difficulties. Emot. Behav. Diffic. 22, 18–34. doi: 10.1080/13632752.2017.1287342

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2017a). International migration report 2017. Available at: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/public ations/migrationreport/docs/MigrationReport2017.pdf

Keywords: early school leaving, foreign students, inclusion, participation, ecological perspective

Citation: Bembich C (2023) Equity in learning paths and contrast to early school leaving: the complexity of the factors involved in the school experiences of foreign students. Front. Educ. 8:1063754. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1063754

Edited by:

Julia Morinaj, University of Bern, SwitzerlandReviewed by:

Elena Tikhonova, Peoples' Friendship University of Russia, RussiaMeline Kevorkian, Nova Southeastern University, United States

Copyright © 2023 Bembich. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Caterina Bembich, Y2JlbWJpY2hAdW5pdHMuaXQ=

Caterina Bembich

Caterina Bembich