- School of Education, University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD, Australia

Introduction: Teachers play an integral role in providing positive life experiences for their students and are especially crucial for students who are experiencing or have experienced a trauma in their lives. In Australia however, teachers are increasingly stating that they do not plan on remaining in the profession causing media and governments to warn of a teacher shortage. Several key factors for teacher attrition have been proposed, with burnout being described as a contributing factor). Studies which have focused specifically on teachers’ experiences working with students with histories of trauma have suggested links between lack of trauma-aware training and increased levels of compassion fatigue (CF), secondary traumatic stress (STS), and burnout.

Methods: This paper draws on established research into CF, STS and burnout as well as trauma awareness of teachers using a narrative topical approach to explore the challenges faced by teachers and students in a post-covid landscape.

Results: The results of this review suggest a need for additional research into the impact on teachers of working with an increasingly traumatized student body.

Conclusion: The lack of trauma-specific training reported by pre-service and current teachers indicate a need for higher education institutions and schools to better prepare teachers to support traumatized students while safeguarding their own wellbeing.

1. Introduction

Children in Australia are increasingly showing symptoms of traumatic exposure and poor mental health with the number of mental health presentations to children’s emergency wards increasing by 6.5% a year since 2009 pre-COVID-19 (Hiscock et al., 2018). These symptoms of childhood trauma and poor mental health are being seen more and more within classrooms and the wider school environment and each year the number of children displaying symptoms increases due to natural disasters, the fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic, and many other global and local factors (L'Estrange and Howard, 2022). This is in addition to the large number of children in Australia who are being subjected to Adverse Childhood Experiences each year (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2021).

For children who have experienced trauma, the most important protective factor in their lives is a positive, supporting relationship with a safe, attentive, caring adult (Post et al., 2020). For many children, the only stable relationship they may have with an adult is with their teacher. For all children, teachers have the ability to support healthy development and mitigate the impact of trauma (Post et al., 2020). However, in Australia, teachers are leaving the profession in record numbers (Heffernan et al., 2022; Ministers Media Centre, 2022). Those who have left give many reasons for their decision with a high number indicating that they felt burnt-out. Other factors have been reported as reasons for teacher attrition, including increased workloads (Kelchtermans, 2017), reduction in teacher status and concerns about salary (Rice, 2005), difficulties coping with external testing and accountability (Ryan et al., 2017), and emotional exhaustion [compassion fatigue (CF)], stress (including secondary traumatic stress), and burnout (Lee, 2019; Heffernan et al., 2022). Many studies have been conducted into the impacts of teacher workloads (Green, 2018; Gavin et al., 2021) and increased external testing (Kruger et al., 2018), and governments are beginning to address concerns about teacher salary (Smail, 2022). However, while burnout in teachers has attracted considerable attention (Saloviita and Pakarinen, 2021), there is less known about the related constructs of CF and STS as they relate to teaching although these have been emerging in recent years as key constructs in understanding burnout (Ormiston et al., 2022).

It is known that burnout in teachers can lead to a reduction in effectiveness in the classroom as individuals display emotional exhaustion brought on by chronic work strain (Chirico et al., 2019). This can be exacerbated by the effects of Secondary Traumatic Stress (STS), whereby tension or stress is felt by someone in a caring role when hearing about a traumatic event or situation being experienced by someone in their care (Essary et al., 2020). CF is comprised of STS and burnout and is described as the culmination of the negative impacts of working in a psychologically upsetting environment that can impact on an individual’s ability to feel compassion for others (Turgoose and Maddox, 2017).

The following literature review will examine different schools of thought about the circumstances which can lead to teacher burnout and the relationships between burnout, secondary traumatic stress, and compassion fatigue. It will also explore the current fundamental concepts, issues, and problems surrounding the landscape of complex trauma in Australia and the impact that has been felt since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, it will investigate current research gaps surrounding those elements which can be protective factors for students and/or teachers and consider whether levels of burnout in teachers and thus attrition can be lowered by addressing those factors. The review aims to answer two research questions, how is the wellbeing of teachers impacted when working with students who have experienced trauma and how can the wellbeing of teachers who work with students who have experienced trauma be better protected?

2. Methods

The research questions as well as the criteria for inclusion in this review were developed using the PICO protocol for qualitative research (Schardt et al., 2007). This protocol prompts researchers to describe the Population (teachers), Intervention/Exposure (trauma in schools, COVID pandemic) and Outcome/Context (burnout, compassion fatigue, secondary traumatic stress).

Searches of several databases (EBSCO, ProQuest, Pubmed and Scopus) as well as a manual search of Google Scholar were conducted in December 2022 and failed to return any hits when searching for keywords—CF, STS, Burnout, teachers, COVID and trauma—and so the decision was made to complete several searches and collate the results in a narrative literature review.

First, in order to define the terms and gather an understanding of the relationship between them, a search was conducted using the string “burnout AND compassion fatigue AND secondary traumatic stress.” Secondly the keyword “teachers” was added to the string in order to gather research about how these concepts have been found to impact on our chosen population. Thirdly, searches were made using the keywords “trauma AND teachers AND burnout” and “COVID AND teachers AND burnout.” Finally, a manual search of reference lists and recommended readings was carried out as well as a search of grey literature such as government reports and websites. By collating and synthesizing the information gathered through these different searches, a deeper understanding is reached as the relationships between these different constructs begins to emerge.

3. Results

3.1. Defining burnout, secondary traumatic stress, compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction.

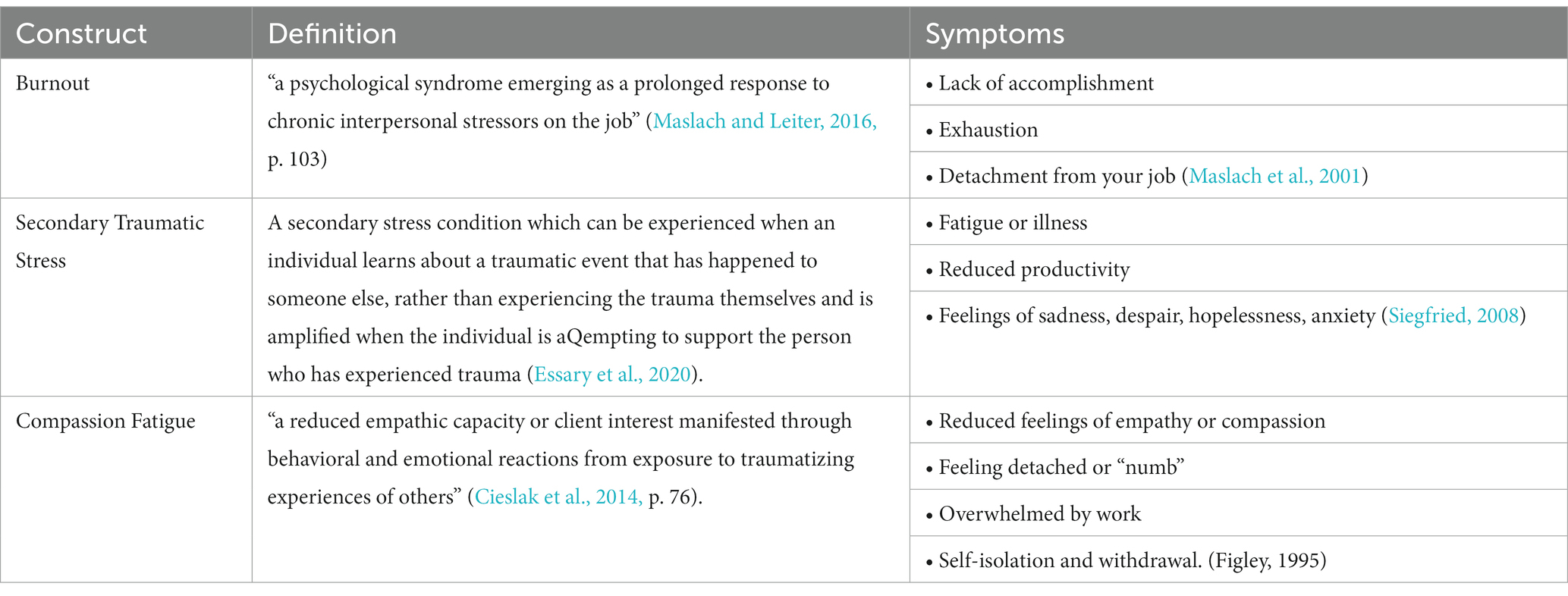

Burnout has been defined as “a psychological syndrome emerging as a prolonged response to chronic interpersonal stressors on the job” (Maslach and Leiter, 2016, p. 103) and has been linked with teacher absenteeism, early retirement, and teacher attrition (Saloviita and Pakarinen, 2021). Burnout gradually develops and is generally described using three categories: lack of accomplishment, exhaustion, and detachment from your job (Maslach et al., 2001). Most individuals experiencing burnout state that the feeling of being worn-out or emotionally exhausted and drained is their dominant feeling (Maslach and Leiter, 2017).

In many different studies, teaching has been found to be among the most stressful occupations globally (Johnson et al., 2005; Richards et al., 2018). Johnson et al. (2005) conducted a review of studies conducted in the United Kingdom using the same measurement tool across 26 different occupations including over 25,000 individuals and found that teaching was reported to have amongst the lowest levels of job satisfaction and highest levels of physical and psychological stress, rating alongside ambulance officers, police, prison officers, call centers, and social services.

Secondary Traumatic Stress (STS) is a secondary stress condition which can be experienced when an individual learns about a traumatic event that has happened to someone else, rather than experiencing the trauma themselves and is amplified when the individual is attempting to support the person who has experienced trauma (Essary et al., 2020). Figley (1995) describes STS as “the natural consequent behaviors and emotions resulting from knowing about a traumatizing event experienced by a significant other—the stress resulting from wanting to help a traumatized or suffering person” (p. 7). Although prevalence rates can vary between professions and geographic locations, one study of Canadian school staff reported that 43% displayed moderate levels of STS (Koenig et al., 2018).

Secondary traumatic stress and Compassion Fatigue (CF) emerged as constructs from the healthcare and mental health professions (Sinclair et al., 2017) and have recently begun to be examined in the teaching context (Ormiston et al., 2022). Cieslak et al. (2014) define CF as “a reduced empathic capacity or client interest manifested through behavioral and emotional reactions from exposure to traumatizing experiences of others” (p. 76). It is typically seen in individuals who provide support to someone who has experienced or is experiencing a traumatic event.

Figley’s (1995) Compassion Stress and Fatigue Model, although originally constructed for use in the Mental Health industry, discusses the many different aspects of CF and centers empathy with CF described as the “cost” of feeling empathy and compassion for others while trying to help or support them. Higher levels of CF can be seen in teachers who care for students with histories of trauma and include witnessing the social, behavioral, and academic costs of these traumas (Hupe and Stevenson, 2019). In one study of 872 educators in Spanish speaking countries, 71.4% reported high levels of CF (Pérez-Chacón et al., 2021). Table 1 explains the constructs of CF, STS, and burnout.

Compassion Satisfaction (CS) has been described as an individual’s sense of self-efficacy related to their helping profession, as well as their sense of positivity and satisfaction regarding their helping work (Stamm, 2010; Figley, 2013). Abraham-Cook’s, 2012 study into the correlates between CF, CS, and burnout in teachers found that moderate levels of compassion satisfaction were found to be a protection against burnout and Caringi et al. (2015) found that the self-efficacy that came with working with “troubled” students was a protective factor against STS. It is clear from the research conducted with teachers and others in the helping professions that working with individuals who have experienced trauma can have a negative impact on the wellbeing of all those involved. However, the literature also suggests that a feeling of confidence or self-efficacy about one’s ability to support traumatized individuals can reduce that impact.

3.2. Trauma awareness and self-efficacy of teachers and how it impacts levels of CF and STS

In their 2020 study, Christian-Brandt and colleagues examined the characteristics of teachers associated with their perceptions of the effectiveness of trauma-informed practices (TIP) programs in place at their schools as well as their intent to remain in the education field. Their study included 163 participants, all teachers at low-income and underserved elementary schools in a single school district in the United States. They found that higher levels of CS and STS as well as lower levels of burnout were associated with higher levels of perceived TIP effectiveness (Christian-Brandt et al., 2020).

Training in TIP in schools has also been shown to mitigate CF and STS levels in teachers (Peterson, 2019; Christian-Brandt et al., 2020; Anderson et al., 2021). In their systematic literature review on STS and CF in teachers, Ormiston et al. (2022) suggested a two-pronged approach of creating a school system that enabled teachers to receive training and education related to TIP as well as creating a clear system of interagency collaboration with schools to provide opportunities for students to receive any interventions from mental-health specialists that they may need. They found that studies which looked at schools with these two approaches reported more positive feedback from teachers overall, although few studies explicitly linked TIP training with intent to leave the profession. One study which did explicitly link the two found that having training in TIP and having confidence to work within a TIP framework lessened the desire of some teachers to leave the profession (Peterson, 2019), however this study was conducted with a very small sample of only six teachers and much more data are needed for any conclusions to be drawn.

Self-efficacy has been described as an individual’s psychological disposition resulting from a self-assessment of one’s ability to accomplish tasks successfully (Bandura, 1997). Many researchers have understood the link between teacher efficacy and burnout with burnout being described as a breakdown of efficacy (Friedman, 2003) or an efficacy crisis (Leiter, 1992). Teacher efficacy has also been found to be a personal protective factor against burnout (Friedman, 2000; Dicke et al., 2014; Zhu et al., 2018). However, teachers’ roles have changed and expanded due to students’ increasing emotional, cognitive, and behavioral needs and the impacts of the pandemic, and children and young people in Australia are experiencing complex trauma in increasing numbers each year (Calvano et al., 2021). This has led to many teachers indicating that they feel ill-equipped by their teacher training to adequately support those students who have a history of trauma (Grybush, 2020; Levkovich and Gada, 2020; Oberg and Bryce, 2022). As teachers are encountering more students in their classrooms who are displaying symptoms of complex trauma, understanding the impact that lack of self-efficacy regarding teachers’ ability to support these students can have on teachers’ levels of CF, STS, and burnout is becoming more important than ever.

3.3. What is the impact when teachers have high levels of STS, CF, and burnout?

As high levels of stress and burnout can clearly have negative implications on teacher’s wellbeing, it is unsurprising that these impacts on wellbeing are also observed in their students (Geving, 2007; Herman et al., 2018). Geving (2007) specifically found that students who were taught by teachers exhibiting symptoms of stress displayed higher levels of negative behaviors such as being critical of their peers, disrespecting their teachers, and damaging school property. Kokkinos (2007) supported these findings and found that high levels of teacher burnout were associated with higher rates of student antisocial behavior. Conversely, it has also been shown that enhanced teacher wellbeing has positive effects on the wellbeing of students (Carroll et al., 2021).

Teachers who report high levels of stress and burnout also report higher rates of physical and mental health difficulties as well as job satisfaction levels which are below average (Herman et al., 2018). This high level of stress in the workplace can lead to high numbers of teachers being absent from work, either physically or psychologically (Jennings and Greenberg, 2009; Herman et al., 2018). This absence means that learning and teaching, as well as behavior management strategies are no longer consistent for students, and has the potential to contribute to poor academic and behavioral outcomes. In their study of 121 teachers, Herman et al. (2018) found that their participants who identified as stressed and with low coping skills also taught the student cohorts with lower adaptive behaviors, lower math achievement and higher levels of disruptive behavior.

While the impact of teacher burnout on students is an understudied area, a systematic review of studies into teacher burnout and the impact on students did in fact find a relationship between teacher levels of burnout and low levels of student academic achievement as well as poorer student motivation (Madigan and Kim, 2021). This systematic review highlights a gap in research in this area as only 14 articles were found globally on this topic and the review authors indicated that few of them included a robust measure of burnout. Although they may be preliminary however, these studies do indicate a further reason beyond increasing teacher wellbeing and retention to investigate ways to mitigate the risk of teachers developing high levels of burnout.

3.4. What protective factors can reduce the risk of teachers having high levels of STS, burnout, and CF?

Teachers’ levels of CF and STS and the protective factors against them are largely under-researched areas. In a 2022 systematic literature review focusing of CF and STS in teachers, Ormiston et al. conducted two searches to find articles related to teachers’ STS and/or CF and only found 17 studies globally, and fewer than half were peer reviewed. This is clear evidence of the scarcity of research exploring teachers and their experiences of CF and STS. Although this topic is largely under-studied, there have been some valuable studies which have explicitly examined the ways that CF and STS in teachers can be mitigated.

Christian-Brandt et al. (2020) focused on teacher wellbeing and found that Compassion Satisfaction (CS) seemed to be the opposite of CF and in fact help protect against it. CS was found to be developed more often in teachers who had strong social support networks (positive feedback, supportive administration; Abraham-Cook, 2012) and these networks also appeared to reduce stress levels and symptoms of burnout. Teachers who participated in reflective supervision, a practice which has long been in place in the mental health and social work fields (Tomlin et al., 2014) but largely understudied in education (Christian-Brandt et al., 2020), reported higher levels of CS (Brown, 2016; Lepore, 2016).

In addition, enhancing teacher creativity and understanding of TIP can also work toward mitigating CF and STS (Peterson, 2019; Christian-Brandt et al., 2020; Anderson et al., 2021). Anderson et al. (2021) examined the relationship between STS and creative anxiety (the worry and unease that results from having to constantly come up with new or creative ways to teach concepts). They found that there was a significant positive correlation between creative anxiety, stress, and STS and that as their participants (n = 57 teachers) gained knowledge through professional development on integrating creativity in teaching, their levels of creative anxiety and STS fell.

Christian-Brandt et al. (2020) studied teachers in a low-income school district which was implementing TIP. They found that teachers with low levels of burnout and high levels of compassion satisfaction also perceived the TIP as more effective and reported less intention to leave the profession. Interestingly, teachers with a high level of STS also indicated higher perceived effectiveness of TIP, which may be due to the fact that teachers who have experienced more STS from working with traumatized students are more eager to engage with TIP principles. This supports prior findings by Baweja et al. (2016) who found that teachers who reported that they worked with students displaying high levels of trauma also strongly expressed their desire for further training in TIP. Although in some educational environments the idea persists that training in trauma is solely the remit of the school guidance officer or counselor and not required for classroom teachers (Costa, 2017; Howard, 2019). Given the number of students impacted by trauma and the ways in which working with these students can affect teachers however, it seems less and less acceptable that only certain staff members are given the tools to mitigate these impacts.

3.5. Complex trauma in Australian children

Teacher’s levels of STS and burnout can be impacted by working with children who have experienced or are experiencing symptoms of complex trauma. Follette et al. (1996) referred to the concept of complex trauma when they stated that “multiple trauma experiences would lead to increased trauma symptoms, and that as the number of different traumatic experiences increased, subjects would demonstrate a cumulative impact of trauma” (Follette et al., 1996, p. 27). They concluded that the impacts of repeated exposure to trauma increase cumulatively across time.

Experiencing complex trauma during childhood can be a common occurrence and can continue to have an impact on a person’s life many years after the events which caused the trauma have ended (Su and Stone, 2020). The Australian Bureau of Statistics (2019; ABS) report that approximately 2.5 million Australian adults have experienced abuse during their childhood. This equates to 13% of the adult population. This includes 1.6 million (8.5%) who have reported physical abuse in childhood and 1.4 million (7.7%) who experienced childhood sexual abuse.

Similarly, the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW, 2021a) released a report on the utilization of Child Protective Services in Australia during 2019–2020 showing that during this period 174,700 children, or one in every 32 children in Australia, received services from the Child Protection Agency. Of those children, 30,600 had been living in out of home care for 2 years or more, compounding the trauma of neglect or abuse with the added potential trauma of being removed from home and placed in foster care (Riebschleger et al., 2015; Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2021). Perhaps the most alarming statistic from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2021) report was the fact that 67% of those children who received child protective services during the 2019–2020 year were subject to multiple reports and interventions. This is particularly alarming given the evidence that repeated exposure to childhood trauma and mistreatment has been linked to increased risk of poor health and social outcomes during adulthood (Felitti et al., 1998).

Although these figures are staggering, the wide variance in cultural understandings as to what constitutes abuse or neglect of a child has meant that the true rates of prevalence of child maltreatment in Australia are difficult to estimate (Child Family Community Australia, 2017; CFCA). The Child Family Community Australia (2017) conducted an overview of Australian studies into the five different forms of child abuse (physical and sexual abuse, emotional maltreatment, exposure to familial violence, and neglect) to gain a realistic indication of the prevalence of child maltreatment. The authors noted several limitations to this review, namely that there were considerable ethical and practical difficulties involved in gaining a true picture of maltreatment such as a difference in whether such activities as smacking or exhibitionism were considered maltreatment by different communities (Child Family Community Australia, 2017). Despite these limitations and difficulties, the report concluded that child maltreatment occurs, across all five categories, in significant numbers within Australia. While these figures indicate a concerning trend, the complete picture may be even more alarming. Globally, many studies have been conducted into the long-term impacts on individuals who experience maltreatment in childhood beginning with the original Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study in the mid-nineties (Felitti et al., 1998).

3.5.1. Adverse childhood experience (ACE) studies

The original ACE study took place between 1995 and 1997 and was led by Dr. Vincent Felitti from Kaiser Permanente Department of preventative medicine and Dr. Robert Anda from the Centre for Disease Control (CDC) in the United States. It was the first study to examine the long-term impacts of childhood trauma and was one of the largest investigations of childhood familial trauma and later-life health and wellbeing (Bryce, 2017). ACEs include experiences which directly impact students, such as physical, sexual, or psychological abuse and/or neglect, and those where the impacts are more indirect, such as family members who have addiction issues, or are incarcerated (Centre for Children’s Health and Wellbeing, n.d.; Felitti et al., 1998; Hughes et al., 2017).

The ACE study utilized a questionnaire to capture the ACEs of more than 9,000 respondents who had also completed a medical evaluation at a large Health Maintenance Organization (HMO; Felitti et al., 1998). A direct link was discovered between episodes of adverse childhood experiences and later-life onset of chronic disease and mental illness as well as an increased risk of poor social outcomes such as unemployment, addiction, and imprisonment (Felitti et al., 1998; Bryce, 2017). The study also found a direct relationship between the number of ACEs an individual reported and their risk of developing negative physical, mental health, and social outcomes in later-life (Felitti et al., 1998).

3.6. Teachers’ self-efficacy in supporting children with complex trauma in the classroom

Although there is limited research which investigates the perspectives of teachers who are working with students experiencing the symptoms of exposure to complex trauma including multiple ACEs this limited research does suggest that working with traumatized students is likely a common occurrence for teachers (Hayes, 2022). In a random sample of teachers in Netherlands, 89% of participants indicated that they were working with at least one student who had experienced more than one traumatic event (Alisic et al., 2012).

Although the data suggests that the vast majority of teachers will experience working with traumatized students, studies repeatedly demonstrate that teachers do not feel sufficiently skilled or knowledgeable to be able to support these students in the best manner (Alisic, 2012; Oberg and Bryce, 2022). Nor did teachers understand the impacts of trauma and adversity of childhood development and academic achievement (Alisic, 2012; Berger and Samuel, 2020). Working with traumatized students has the potential to impact the wellbeing of teachers and create emotional strain for them (Brunzell et al., 2018; Luthar and Mendes, 2020) as they feel torn between their roles in providing instruction for students on the academic curriculum and looking after students’ emotional wellbeing (Alisic, 2012; Brunzell et al., 2018).

Many studies also found that many teachers lack confidence in their ability to support traumatized students and that lack of sufficient training in trauma-aware practices was impacting teachers’ feelings of self-efficacy (Alisic, 2012; Brunzell et al., 2018; Luthar and Mendes, 2020; Oberg and Bryce, 2022).

Many teachers have described the emotional impacts of working with students experiencing trauma (see for example, Alisic, 2012; Brunzell et al., 2018; Berger and Samuel, 2020). These impacts range in severity from feelings of frustration or fatigue, through to teachers who report feeling too emotionally involved and that concerns from school were impacting their home lives. Many teachers in these studies also described the support of colleagues and school administration as helping to relieve these emotional impacts.

3.7. COVID as a contributing factor

During the COVID-19 pandemic teachers, as well as students and their families, have been subjected to multiple additional stressors such as home schooling, lockdowns, social distancing and closed borders separating families (Calvano et al., 2021). These changes, when combined with potential economic stressors including job losses and reduction in hours, the difficulties in working from home, and the impact of social isolation on parents have had a profound impact on familial interactions and in some cases increased the number of ACEs experienced by children (Cluver et al., 2020; Gallagher and Wetherell, 2020). Given the recency of the COVID-19 outbreak and the fact that many countries are only now emerging from strict lockdowns, there are limited studies investigating the impact of COVID-19 on ACEs around the world however, previous research has confirmed the increase in violence and vulnerabilities during periods of school closures due to health emergencies (Rothe et al., 2015) leading many to anticipate a rise in cases during the current pandemic (Bryant et al., 2020).

One of the few studies that have taken place during the COVID-19 pandemic was conducted in Germany in August 2020. Calvano et al. (2021) surveyed 1,024 parents of primary-aged children and reported that parental stress increased significantly during the pandemic (d = 0.21). Within the group surveyed, 29.1% of parents reported that there had been an increase in domestic violence incidence witnessed by their children and a 42.2% increase in the number of children subjected to verbal and emotional abuse. While some parents surveyed had reported positive impacts such as an increase in family time and a slower pace of life, there was a significant subgroup of families who had seen an increase in ACEs (Calvano et al., 2021). These results indicate that scholars may be accurate in predicting a rise in adverse childhood experiences during this time and as lockdowns ease and more children are returning to school, those in the helping professions, including teachers will need to be prepared in knowing how to best help these children.

In addition to COVID potentially leading to an increase in children experiencing maltreatment, literature is beginning to emerge which argues that given the collective nature of the pandemic, and the trauma associated with job losses, death of loved ones, lockdowns, isolation, and heightened stress, COVID itself to should be classified as an Adverse Childhood Experience (McManus and Ball, 2020; Hyter, 2021) which is impacting all children globally and causing many to display symptoms of toxic stress (Araújo et al., 2021). It is in this environment that teachers are finding themselves not only experiencing the stress of living during a pandemic, but also attempting to negotiate changing work conditions as well as meet the needs of a cohort of students who are displaying increasing symptoms of stress, trauma, and negative mental health (Araújo et al., 2021). The accumulated effects of trying to balance their own COVID-related stress while also supporting the complex needs of their students is contributing to increased numbers of teachers reporting feelings of burnout and fatigue (Pressley, 2021). In this ever-changing environment, understanding those factors which can mitigate the impacts of trauma on students and teachers has gained renewed importance as a potential development in the field of student and teacher wellbeing.

3.8. Making schools a place of protection through trauma-informed practices

The past decade has seen an emergence of research which, instead of focusing on the negative effects of childhood trauma, is instead seeking an explanation as to why some people are so negatively impacted, while others seem not only to recover, but to thrive (Mohr and Rosén, 2017). Our understandings surrounding how individuals respond to childhood trauma have been broadened by these studies into resilience (ability to recover), and posttraumatic growth (ability to thrive; Bonanno and Diminich, 2013) and protective factors which have the ability to promote both resilience and posttraumatic growth are beginning to be identified (Mohr and Rosén, 2017; Crouch et al., 2019).

For most children, traumatic events such as peer bullying, natural disasters, or community violence happen outside of the home and factors such as having a close, supportive family or a safe and secure home can be significant enough to limit the impacts of this trauma (Herrenkohl et al., 2019). For those children however who experience traumatic events within their home, protective factors outside gain an increased level of importance (Chafouleas et al., 2016). As so much time is spent in school across the year, Veltman and Browne (2001) argue that schools have the potential to be a significant protective factor for children and to mitigate the effects of complex trauma if they follow appropriate trauma-aware and child protection policies and practices. Due to these studies and others which demonstrated similar outcomes, many scholars argue that there is a pressing need to develop a school system which is able to respond positively to children who have been affected by trauma and meet their needs (Herrenkohl et al., 2019; Howard, 2019).

Trauma-informed practices (TIPs) are those support provisions put in place which consider not only the occurrence of adverse experiences in childhood, but also how these experiences can impact children’s development, wellbeing, and ability to learn (Morgan et al., 2015). Dorado et al. (2016) argue that within the school environment, TIPs present an opportunity to intervene in difficult behaviors while being considerate of a child’s mental and emotional wellbeing. In this way TIPs can be considered as an alternative to the more traditional punitive and reactive behavior management strategies adopted by many schools (Dorado et al., 2016). Poole and Greaves (2012) emphasize the need for a school to operate under the principles of safety, control, empowerment, and choice for staff and students alike.

3.9. Teacher preparation: Preservice and workforce training

Although there is a significant lack of research surrounding teachers’ perceptions regarding complex trauma, there have been several studies conducted into teachers’ perceptions regarding the impact that can be seen in children experiencing distinct simple traumas. One such study was conducted by Atiles et al. (2017) and investigated the impact that familial divorce can have on children and teachers’ understanding of that impact. Participants within the study were found to have a moderate understanding (n = 72) of how divorce in families can impact children and perhaps more importantly, a statistically significant, positive correlation (r = 0.455, p = 0.000) was found between a teachers’ ability to understand the impacts of divorce on children and their sense of self-efficacy in being able to cater for those children (Atiles et al., 2017).

Similar studies have been conducted into teachers’ perceptions regarding their ability and preparedness to support children after suicide attempt (Buchanan and Harris, 2014) and natural disasters (Green-Derry, 2014). Researchers in both studies discovered that teachers felt ill-prepared and lacked confidence in knowing how to support the emotional and mental health needs of their students. A lack of course work in their pre-service training focused on understanding the mental health and emotional needs of children after trauma was highlighted by participants as contributing to their lack of confidence (Buchanan and Harris, 2014; Green-Derry, 2014). Interestingly, although they all stated that there was a lack in course work on the topic, participants in Green-Derry's (2014) study were residents of New Orleans during Hurricane Katrina and indicated that they felt their lived experience of natural disaster, as well as their time on placement in a city that had experienced a collective trauma, had assisted them to gain some confidence in their ability to assist students who had lived through similar traumas. Although these studies contain limitations such as sample size and the fact that they are all conducted in the United States rather than Australia, they add credence to the notion that equipping teachers with the understandings and expertise to work with children living in trauma is important.

Closer to home, when researching the availability of teacher training programs focused on trauma-aware teaching practices in Australia, Howard (2019) found an alarming lack. Howard conducted a mixed-methods study looking at both attendance data as well as responses to questionnaires and concluded that although a significant majority (96.6 percent) of personnel in leadership positions within schools ranked trauma training as either important or extremely important for all staff, training was overall, only offered to small groups of staff in non-teaching roles. When analyzing the responses from the teaching staff, Howard (2019) found that over 44 percent of teacher participants had never attended any training on trauma-informed practices, although they had heard of the topic. Howard’s results confirm the findings by Costa (2017) that showed a belief amongst school staff that trauma awareness and training are part of the roles of only a select group of staff members. These results also highlight the lack of knowledge amongst teachers leading to an inability to fully understand the developmental, behavioral, and social impacts of complex trauma on the children who experience it (Walkley and Cox, 2013; Costa, 2017).

4. Discussion

The first research question posed in this review was “how is the wellbeing of teachers impacted when working with students who have experienced trauma?” From the literature reviewed, it is obvious that there are significant impacts on teachers who work with traumatized students and these impacts have increased in recent years.

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, teachers in Australia have reported increased levels of stress, exhaustion, and anxiety (Barnsley, 2020). Teachers surveyed as part of the Australian Education Survey (Ziebell et al., 2020) reported concerns about their own health and wellbeing during the pandemic as they were more isolated due to working from home and more stressed due to changing work conditions and responsibilities.

Teachers are coping with an increasing amount of stress, exhaustion, and burnout due to the pandemic and changes in workload. Adding to this, they are also feeling the effects of supporting children through this stressful and potentially traumatic time, which can increase the risk of experiencing Secondary Traumatic Stress.

Factors such as teachers’ training in and understanding of trauma and the links with self-efficacy about their ability to support traumatized students are important when investigating both student and teacher wellbeing. By gaining knowledge and understanding of trauma, teachers are able to change the focus they are using to observe classroom behaviors, and this can alter the way that they are interpreting and responding to these behaviors (Dorado et al., 2016). Teachers who are trauma-informed will be more likely to observe behaviors and view a student as needing support or help rather than simply regarding them as a child with “problem behaviors” (Dorado et al., 2016, p. 164; Oberg and Bryce, 2022).

Teacher self-efficacy has been demonstrated to be highly significant within the school setting as not only has it been found to protect against emotional overload and burnout (Shead et al., 2016; Boujut et al., 2017) but it has also been found to impact the academic achievement of students (Klassen and Tze, 2014). Teaching as an occupation carries a high risk for stress and burnout (Johnson et al., 2005) and the emotional response felt by teachers who work with students exposed to trauma is becoming more substantial as it is becoming clearer that teachers may be vulnerable to symptoms of STS (Koenig et al., 2018).

Teachers have a unique position with regards to childhood trauma, they are often the first people who are able to respond to children experiencing emotional and behavioral crises in school, and they are often party to descriptions of children’s traumatic experiences (Hydon et al., 2015). This combination of hearing about student traumas as well as experiencing the behavioral and emotional symptoms of those traumas can lead to teachers feeling additional stress, emotional burden, and anxiety (Alisic, 2012; Blitz et al., 2016; Oberg and Bryce, 2022) which has further implications on staff turnover (Caringi et al., 2015). Although prior research examining trauma in childhood has identified significant challenges for those working with traumatized children, few studies have looked into the links with teacher wellbeing (Hydon et al., 2015).

5. Implications

The second question that this review sought to answer was “how can the wellbeing of teachers who work with students who have experienced trauma be better protected?” When looking at the constructs of CF and STS in teachers, there is a scarcity of empirical research, however, the research that has been done does suggest that there are several steps which can be taken to mitigate the effects on teachers of working with students affected by trauma.

Firstly, the research suggests a link between being trauma-informed as a teacher and experiencing lower levels of STS, CF and burnout (Peterson, 2019; Christian-Brandt et al., 2020), however many teachers report feeling that their training with regards to trauma is lacking (Howard, 2019; Oberg and Bryce, 2022). This is concerning as teachers who lack adequate training may be less effective in supporting students as well as safeguarding their own wellbeing. This finding lends weight to the call for trauma-specific training to be made available on an ongoing basis to all pre-service and current classroom teachers and for this training to include topics on emotional self-care for teachers. This training is the first step in creating school communities which have trauma-informed practices (TIPs) as their foundation.

In order to be fully effective, TIPs in school environments should include both whole-school approaches such as education for staff, students, and families as well as responses to behavior based on safety, wellbeing, and empowerment (Perry and Daniels, 2016). Schools should also respond on a more individual level to students who have experienced trauma by implementing more intensive programs such as psychoeducational programs, trauma assessments, and trauma-focused interventions (Woodbridge et al., 2016; Record-Lemon and Buchanan, 2017). Current research indicates that TIPs in Australian schools differ from school to school and are very hit or miss (Howard, 2019), however the potential benefits for both students and teachers add to the argument that a systemic framework for trauma-informed practices is needed Australia-wide.

It is evident that CF and STS in teachers and how these constructs relate to trauma-awareness is an area that is lacking in empirical studies.

6. Limitations

The lack of empirical, peer-reviewed studies found during database searches addressing all search terms has identified a research gap and need for further exploration. However, it has also led to a reduction in the systemic nature of this review which may impact replicability of this study. Further, although all efforts were made to synthesize the most significant findings from each of the different areas reviewed, researcher bias may have played a part in both the selection, and interpretation of, the different studies selected.

To address the findings and limitations of this review, the following recommendations are made: firstly, a survey of Australian teachers to determine their current rates of CF, STS, and burnout as well examining their current understandings and confidence regarding trauma-informed practices; secondly, in-depth interviews with teachers to gain a deeper understanding of their beliefs about factors that protect against burnout, STS, and CF when working with students effected by trauma and those which can enhance their sense of efficacy; and thirdly, development of frameworks for self-care and peer support from other helping professions and possible adaptations for use in an educational environments should be further investigated.

7. Conclusion

This review collated and examined research into the reasons for teacher burnout as well as the relationship between burnout, secondary traumatic stress, and compassion fatigue. Secondly, it explored the current levels of trauma-awareness and self-efficacy of teachers and how these factors relate to compassion fatigue and burnout and finally, it examined the research about protective factors against burnout, compassion fatigue, and secondary traumatic stress. Further research into the effects being felt by teachers working in this environment is recommended, with the hope that this will lead to targeted training for both pre-service, and experienced teachers and add to the call for trauma-informed practice to be implemented at a systemic level. This is necessary, not only for the benefit of students experiencing trauma, but also for the wellbeing of teachers and others who work in schools.

Author contributions

GO constructed the research questions, conducted the review, and wrote the article. AC and SM revised, reviewed, and supported the writing of this article. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abraham-Cook, S. (2012). The prevalence and correlates of compassion fatigue, compassion satisfaction, and burnout among teachers working in high-poverty urban public schools. doctoral dissertation, Seton Hall University).

Alisic, E. (2012). Teachers' perspectives on providing support to children after trauma: a qualitative study. Sch. Psychol. Q. 27, 51–59. doi: 10.1037/a0028590

Alisic, E., Bus, M., Dulack, W., Pennings, L., and Splinter, J. (2012). Teachers' experiences supporting children after traumatic exposure. J. Trauma. Stress. 25, 98–101. doi: 10.1002/jts.20709

Anderson, R. C., Bousselot, T., Katz-Buoincontro, J., and Todd, J. (2021). Generating buoyancy in a sea of uncertainty: teachers creativity and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 11:3931. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.614774

Araújo, L. A. D., Veloso, C. F., Souza, M. D. C., Azevedo, J. M. C. D., and Tarro, G. (2021). The potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on child growth and development: a systematic review. J. Pediatr. 97, 369–377. doi: 10.1016/j.jped.2020.08.008

Atiles, J. T., Oliver, M. I., and Brosi, M. (2017). Preservice teachers’ understanding of children of divorced families and relations to teacher efficacy. Educ. Res. Q. 40, 25–49.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2019). Characteristics and outcomes of childhood abuse. Available at: https://www.abs.gov.au/articles/characteristics-and-outcomes-childhood-abuse

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2021). Child protection Australia 2019–20. Available at: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/child-protection/child-protection-australia-2019-20/summary

Barnsley, W. (2020). Stress and anxiety high among teachers as schools remain open despite coronavirus pandemic. 7NEWS Web site. Published March 20, 2020. Available at: https://7news.com.au/lifestyle/health-wellbeing/stress-and-anxiety-high-among-teachers-as-schools-remain-open-despite-coronavirus-pandemic-c-755061

Baweja, S., Santiago, C. D., Vona, P., Pears, G., Langley, A., and Kataoka, S. (2016). Improving implementation of a school-based program for traumatized students: identifying factors that promote teacher support and collaboration. Sch. Ment. Heal. 8, 120–131. doi: 10.1007/s12310-015-9170-z

Berger, E., and Samuel, S. (2020). A qualitative analysis of the experiences, training, and support needs of school mental health workers regarding student trauma. Aust. Psychol. 55, 498–507. doi: 10.1111/ap.12452

Blitz, L. V., Anderson, E. M., and Saastamoinen, M. (2016). Assessing perceptions of culture and trauma in an elementary school: informing a model for culturally responsive trauma-informed schools. Urban Rev. 48, 520–542. doi: 10.1007/s11256-016-0366-9

Bonanno, G. A., and Diminich, E. D. (2013). Annual research review: positive adjustment to adversity-trajectories of minimal–impact resilience and emergent resilience. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 54, 378–401. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12021

Boujut, E., Popa-Roch, M., Palomares, E. A., Dean, A., and Cappe, E. (2017). Self-efficacy and burnout in teachers of students with autism spectrum disorder. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord. 36, 8–20. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2017.01.002

Brown, L. (2016). The impact of reflective supervision on early childhood educators of at-risk children: Fostering compassion satisfaction and reducing burnout (Publication No. 10193236). [Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Santa Barbara]. ProQuest LLC.

Brunzell, T., Stokes, H., and Waters, L. (2018). Why do you work with struggling students? Teacher perceptions of meaningful work in trauma-impacted classrooms. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 43, 116–142. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2018v43n2.7

Bryant, D. J., Oo, M., and Damian, A. J. (2020). The rise of adverse childhood experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 12, S193–S194. doi: 10.1037/tra0000711

Bryce, I. (2017). Cumulative Harm and Resilience Framework: An Assessment, Prevention and Intervention Resource for Helping Professionals. Boston, MA: Cengage.

Buchanan, K., and Harris, G. E. (2014). Teachers’ experiences of working with students who have attempted suicide and returned to the classroom. Can. J. Educ. 37, 1–28.

Calvano, C., Engelke, L., Di Bella, J., Kindermann, J., Renneberg, B., and Winter, S. M. (2021). Families in the COVID-19 pandemic: parental stress, parent mental health and the occurrence of adverse childhood experiences—results of a representative survey in Germany. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry, 31, 1–13.

Caringi, J. C., Stanick, C., Trautman, A., Crosby, L., Devlin, M., and Adams, S. (2015). Secondary traumatic stress in public school teachers: contributing and mitigating factors. Adv. School Ment. Health Promot. 8, 244–256. doi: 10.1080/1754730X.2015.1080123

Carroll, Y. A., Fynes-Clinton, S., Sanders-O'Connor, E., Flynn, L., Bower, J. M., Forrest, K., et al. (2021). The downstream effects of teacher well-being programs: improvements in Teachers' stress, cognition and well-being benefit their students. Front. Psychol. 12:689628. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.689628

Centre for Children’s Health and Wellbeing. (n.d.) ACES and toxic stress. dream big act big for kids 1. Available at: https://www.childrens.health.qld.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/PDF/dream-big/Dream-Big-Act-Big-for-Kids-Issue-1-ACEs-Toxic-Stress.pdf

Chafouleas, S., Johnson, A., Overstreet, S., and Santos, N. (2016). Toward a blueprint for trauma-informed service delivery in schools. Sch. Ment. Heal. 8, 144–162. doi: 10.1007/s12310-015-9166-8

Child Family Community Australia. (2017). The prevalence of child abuse and neglect. Australian Institute of Family Studies. Available at: https://aifs.gov.au/cfca/publications/prevalence-child-abuse-and-neglect

Chirico, F., Taino, G., Magnavita, N., Giorgi, I., Ferrari, G., Mongiovì, M. C., et al. (2019). Proposal of a method for assessing the risk of burnout in teachers: the VA. RI. BO strategy. G Ital. Med. Lav. Ergon. 41, 221–235.

Christian-Brandt, A. S., Santacrose, D. E., and Barnett, M. L. (2020). In the trauma-informed care trenches: teacher compassion satisfaction, secondary traumatic stress, burnout, and intent to leave education within underserved elementary schools. Child Abuse Negl. 110:104437. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104437

Cieslak, R., Shoji, K., Douglas, A., Melville, E., Luszczynska, A., and Benight, C. C. (2014). A meta-analysis of the relationship between job burnout and secondary traumatic stress among workers with indirect exposure to trauma. Psychol. Serv. 11, 75–86. doi: 10.1037/a0033798

Cluver, L., Lachman, J. M., Sherr, L., Wessels, I., Krug, E., Rakotomalala, S., et al. (2020). Parenting in a time of COVID-19. Lancet 395:e64. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30736-4

Costa, D. A. (2017). Transforming traumatised children within NSW Department of Education schools: one school counsellor's model for practice–rewire. Child. Aust. 42, 113–126. doi: 10.1017/cha.2017.14

Crouch, E., Radcliff, E., Strompolis, M., and Srivastav, A. (2019). Safe, stable, and nurtured: protective factors against poor physical and mental health outcomes following exposure to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). J. Child Adolesc. Trauma 12, 165–173. doi: 10.1007/s40653-018-0217-9

Dicke, T., Parker, P. D., Marsh, H. W., Kunter, M., Schmeck, A., and Leutner, D. (2014). Self-efficacy in classroom management, classroom disturbances, and emotional exhaustion: a moderated mediation analysis of teacher candidates. J. Educ. Psychol. 106, 569–583. doi: 10.1037/a0035504

Dorado, J. S., Martinez, M., McArthur, L. E., and Leibovitz, T. (2016). Healthy environments and response to trauma in schools (HEARTS): a whole-school, multi-level, prevention and intervention program for creating trauma-informed, safe and supportive schools. Sch. Ment. Heal. 8, 163–176. doi: 10.1007/s12310-016-9177-0

Essary, J. N., Barza, L., and Thurston, R. J. (2020). Secondary traumatic stress among educators. Kappa Delta Pi Rec. 56, 116–121. doi: 10.1080/00228958.2020.1770004

Felitti, V., Anda, R., Nordenburg, D., Williamson, D., Spitz, A., Edwards, V., et al. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: the adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. Am. J. Prevent. Med. 14, 245–258. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8

Figley, C. R. (2013). Compassion Fatigue: Coping With Secondary Traumatic Stress Disorder in Those Who Treat the Traumatized. Oxfordshire: Routledge.

Figley, C. R. (1995). Compassion Fatigue: Toward a New Understanding of the Costs of Caring. Chicago.

Follette, V., Polusny, M., Bechtle, A., and Nagle, A. (1996). Cumulative trauma: the impact of child sexual abuse, adult sexual assault, and spouse abuse. J. Trauma. Stress. 9, 25–35. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490090104

Friedman, I. A. (2000). Burnout: shattered dreams of impeccable professional performance. J. Clin. Psychol. 56, 595–606. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(200005)56:5<595::AID-JCLP2>3.0.CO;2-Q

Friedman, I. A. (2003). Self-efficacy and burnout in teaching: the importance of interpersonal-relations efficacy. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 6, 191–215. doi: 10.1023/A:1024723124467

Gallagher, S., and Wetherell, M. A. (2020). Risk of depression in family caregivers: unintended consequence of COVID-19. BJPsych. Open 6:E119. doi: 10.1192/bjo.2020.99

Gavin, M., McGrath-Champ, S., Wilson, R., Fitzgerald, S., and Stacey, M. (2021). “Teacher workload in Australia: national reports of intensification and its threats to democracy” in New Perspectives on Education for Democracy eds. S. Riddle, A. Heffernan and D. Bright, Green- Editor C. Carden (Oxfordshire: Routledge), 110–123.

Geving, A. M. (2007). Identifying the types of student and teacher behaviours associated with teacher stress. Teach. Teach. Educ. 23, 624–640. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2007.02.006

Green, M. (2018). “What are the issues surrounding teacher workload?” in Primary Teaching: Learning and Teaching in Primary Schools Today. ed. C. Catherine, Learning Matters, 445.

Green-Derry, L. (2014). Preparation of teachers by a southeastern Louisiana College of Education to meet the academic needs of students traumatized by natural disasters. doctoral dissertation. Retrieved from ProQuest. (3645281).

Grybush, A. L. (2020). Exploring attitudes related to trauma-informed care among teachers in rural title 1 elementary schools: Implications for counselors and counselor educators (publication no. 28002535). Doctoral dissertation, University of North Carolina at Charlotte. ProQuest LLC.

Hayes, H. (2022). “Who minds the minders”: A mixed methods examination of Irish primary school teachers’ experiences of and perspectives on supporting pupils exposed. doctoral dissertation.

Heffernan, A., Bright, D., Kim, M., Longmuir, F., and Magyar, B. (2022). ‘I cannot sustain the workload and the emotional toll’: reasons behind Australian teachers’ intentions to leave the profession. Aust. J. Educ. 66, 196–209. doi: 10.1177/00049441221086654

Herman, K. C., Hickmon-Rosa, J. E., and Reinke, W. M. (2018). Empirically derived profiles of teacher stress, burnout, self-efficacy, and coping and associated student outcomes. J. Posit. Behav. Interv. 20, 90–100. doi: 10.1177/1098300717732066

Herrenkohl, T., Hong, S., and Verbrugge, B. (2019). Trauma-informed programs based in schools: linking concepts to practices and assessing the evidence. Am. J. Community Psychol. 64, 373–388. doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12362

Hiscock, H., Neely, R. J., Lei, S., and Freed, G. (2018). Paediatric mental and physical health presentations to emergency departments, Victoria, 2008–15. Med. J. Aust. 208, 343–348. doi: 10.5694/mja17.00434

Howard, J. (2019). A systemic framework for trauma-informed schooling: complex but necessary! J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 28, 545–565. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2018.1479323

Hughes, K., Bellis, M., Hardcastle, K., Sethi, D., Butchart, A., Mikton, C., et al. (2017). The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2, e356–e366. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30118-4

Hupe, T. M., and Stevenson, M. C. (2019). Teachers’ intentions to report suspected child abuse: the influence of compassion fatigue. J. Child Custody 16, 364–386. doi: 10.1080/15379418.2019.1663334

Hydon, S., Wong, M., Langley, A. K., Stein, B. D., and Kataoka, S. H. (2015). Preventing secondary traumatic stress in educators. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Clin. 24, 319–333. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2014.11.003

Hyter, Y. (2021). A Pandemic's pain: the need for trauma-informed services for children. Leader Live. Available at: https://leader.pubs.asha.org/do/10.1044/leader.FTR1.26102021.38/full/

Jennings, P. A., and Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Rev. Educ. Res. 79, 491–525. doi: 10.3102/0034654308325

Johnson, S., Cooper, C., Cartwright, S., Donald, I., Taylor, P., and Millet, C. (2005). The experience of work-related stress across occupations. J. Manag. Psychol. 20, 178–187. doi: 10.1108/02683940510579803

Kelchtermans, G. (2017). ‘Should I stay or should I go?’: Unpacking teacher attrition/retention as an educational issue. Teach. Teach. 23, 961–977. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2017.1379793

Klassen, R. M., and Tze, V. M. (2014). Teachers’ self-efficacy, personality, and teaching effectiveness: a meta-analysis. Educ. Res. Rev. 12, 59–76. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2014.06.001

Koenig, A., Rodger, S., and Specht, J. (2018). Educator burnout and compassion fatigue: a pilot study. Can. J. Sch. Psychol. 33, 259–278. doi: 10.1177/0829573516685017

Kokkinos, C. M. (2007). Job stressors, personality and burnout in primary school teachers. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 77, 229–243. doi: 10.1348/000709905X90344

Kruger, L. J., Wandle, C., and Struzziero, J. (2018). “Coping with the stress of high stakes testing” in High Stakes Testing: New Challenges and Opportunities for School Psychology eds. L. J. Kruger and D. Shriberg (Oxfordshire: Routledge), 109–128.

Lee, Y. H. (2019). Emotional labor, teacher burnout, and turnover intention in high-school physical education teaching. Eur. Phys. Educ. Rev. 25, 236–253. doi: 10.1177/1356336X17719559

Leiter, M. P. (1992). Burn-out as a crisis in self-efficacy: conceptual and practical implications. Work Stress 6, 107–115. doi: 10.1080/02678379208260345

Lepore, C. E. (2016). The prevention of preschool teacher stress: Using mixed methods to examine the impact of reflective supervision (publication no. 10193227). Doctoral dissertation, University of California, Santa Barbara. ProQuest LLC.

L'Estrange, L., and Howard, J. (2022). Trauma-informed initial teacher education training: a necessary step in a system-wide response to addressing childhood trauma. Front. Educ. 7. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.929582

Levkovich, I., and Gada, A. (2020). “The weight falls on my shoulders”: perceptions of compassion fatigue among Israeli preschool teachers. Asia-Pacific J. Res. Early Childhood Educ. 14, 91–112. doi: 10.17206/apjrece.2020.14

Luthar, S. S., and Mendes, S. H. (2020). Trauma-informed schools: supporting educators as they support the children. Int. J. School Educ. Psychol. 8, 147–157. doi: 10.1080/21683603.2020.1721385

Madigan, D. J., and Kim, L. E. (2021). Does teacher burnout affect students? A systematic review of its association with academic achievement and student-reported outcomes. Int. J. Educ. Res. 105:101714. doi: 10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101714

Maslach,, and Leiter, (2016). Understanding the burnout experience: recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry 15, 103–111. doi: 10.1002/wps.20311

Maslach,, and Leiter, (2017). New insights into burnout and health care: strategies for improving civility and alleviating burnout. Med. Teach. 39, 160–163. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2016.1248918

Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., and Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 52, 397–422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397

McManus, M. A., and Ball, E. (2020). COVID-19 should be considered an adverse childhood experience (ACE). J. Community Safety Well-Being 5, 164–167. doi: 10.35502/jcswb.166

Ministers Media Centre. (2022) Minister for education. Teacher workforce shortages issues paper|ministers' Media Centre (education.gov.au).

Mohr, D., and Rosén, L. A. (2017). The impact of protective factors on posttraumatic growth for college student survivors of childhood maltreatment. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 26, 756–771. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2017.1304478

Morgan, A., Pendergast, D., Brown, R., and Heck, D. (2015). Relational ways of being an educator: trauma-informed practice supporting disenfranchised young people. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 19, 1037–1051. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2015.1035344

Oberg, G., and Bryce, I. (2022). Australian teachers' perception of their preparedness to teach traumatised students: a systematic literature review. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. (Online) 47, 76–101. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2022v47n2.6

Ormiston, H. E., Nygaard, M. A., and Apgar, S. (2022). A systematic review of secondary traumatic stress and compassion fatigue in teachers. Sch. Ment. Heal. 14, 802–817. doi: 10.1007/s12310-022-09525-2

Pérez-Chacón, M., Chacón, A., Borda-Mas, M., and Avargues-Navarro, M. L. (2021). Sensory processing sensitivity and compassion satisfaction as risk/protective factors from burnout and compassion fatigue in healthcare and education professionals. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 18:611. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18020611

Perry, D. L., and Daniels, M. L. (2016). Implementing trauma-informed practices in the school setting: a pilot study. Sch. Ment. Heal. 8, 177–188. doi: 10.1007/s12310-016-9182-3

Peterson, S. (2019). Trauma-informed teachers and their perceived experiences with compassion fatigue (publication no. 13900262). Doctoral dissertation, Capella University. ProQuest LLC.

Poole, N., and Greaves, L. (Eds.). (2012). Becoming Trauma Informed. Toronto, ON: Centre for Addiction and Mental Health.

Post, P. B., Grybush, A. L., Elmadani, A., and Lockhart, C. E. (2020). Fostering resilience in classrooms through child–teacher relationship training. Int. J. Play Therapy 29, 9–19. doi: 10.1037/pla0000107

Pressley, T. (2021). Factors contributing to teacher burnout during COVID-19. Educ. Res. 50, 325–327. doi: 10.3102/0013189X211004138

Record-Lemon, R. M., and Buchanan, M. J. (2017). Trauma-informed practices in schools: a narrative literature review. Can. J. Couns. Psychother. 51.

Rice, S. (2005). You don’t bring me flowers anymore: a fresh look at the vexed issue of teacher status. Aust. J. Educ. 49, 182–196. doi: 10.1177/000494410504900206

Richards, K. A., Hemphill, M. A., and Templin, T. J. (2018). Personal and contextual factors related to teachers’ experience with stress and burnout. Teach. Teach. 24, 768–787. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2018.1476337

Riebschleger, J., Day, A., and Damashek, A. (2015). Foster care youth share stories of trauma before, during, and after placement: youth voices for building trauma-informed systems of care. J. Aggress. Maltreat. Trauma 24, 339–360. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2015.1009603

Rothe, D., Gallinetti, J., Lagaay, M., and Campbell, L. (2015). Ebola: beyond the health emergency. Plan International. Available at: https://plan-international.org/publications/ebola-beyond-health%C2%A0emergency

Ryan, S. V., von der Embse, N. P., Pendergast, L. L., Saeki, E., Segool, N., and Schwing, S. (2017). Leaving the teaching profession: the role of teacher stress and educational accountability policies on turnover intent. Teach. Teach. Educ. 66, 1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2017.03.016

Saloviita, T., and Pakarinen, E. (2021). Teacher burnout explained: teacher-, student-, and organisation-level variables. Teach. Teach. Educ. 97:103221. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2020.103221

Schardt, C., Adams, M. B., Owens, T., Keitz, S., and Fontelo, P. (2007). Utilization of the PICO framework to improve searching PubMed for clinical questions. BMC Medical Inform. Decis. Mak. 7. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-7-16

Shead, J., Scott, H., and Rose, J. (2016). Investigating predictors and moderators of burnout in staff working in services for people with intellectual disabilities: the role of emotional intelligence, exposure to violence, and self-efficacy. Int. J. Dev. Disabil. 62, 224–233. doi: 10.1179/2047387715Y.0000000009

Siegfried, C. B., (2008). Child welfare work and secondary traumatic stress. Child welfare trauma training toolkit: secondary traumatic stress. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Module 6, activity 6c.

Sinclair, S., Raffin-Bouchal, S., Venturato, L., Mijovic-Kondejewski, J., and Smith-MacDonald, L. (2017). Compassion fatigue: a meta-narrative review of the healthcare literature. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 69, 9–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.01.003

Smail, S (2022) Teacher shortages prompt federal government to consider massive pay rises for some and paying others to retrain. ABC. Available at: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-08-02/radical-teaching-reforms-considered/101290982

Stamm, B. H. (2010). The concise ProQOL Manual. Available at: https://img1.wsimg.com/blobby/go/dfc1e1a0-a1db-4456-9391-18746725179b/downloads/ProQOL%20Manual.pdf?ver=1622839353725. Accessed November 1, 2022.

Su, M., and Stone, L. (2020). Adult survivors of childhood trauma: complex trauma, complex needs. Aust. J. General Pract. 49, 423–430. doi: 10.31128/AJGP-08-19-5039

Tomlin, A. M., Weatherston, D. J., and Pavkov, T. (2014). Critical components of reflective supervision: responses from expert supervisors in the field. Infant Ment. Health J. 35, 70–80. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21420

Turgoose, D., and Maddox, L. (2017). Predictors of compassion fatigue in mental health professionals: a narrative review. Traumatology 23, 172–185. doi: 10.1037/trm0000116

Veltman, M. W. M., and Browne, K. D. (2001). Three decades of child maltreatment research: implications for the school years. Trauma Violence Abuse 2, 215–239. doi: 10.1177/1524838001002003002

Walkley, M., and Cox, T. (2013). Building trauma-informed schools and communities. Child. Sch. 35, 123–126. doi: 10.1093/cs/cdt007

Woodbridge, M. W., Sumi, W. C., Thornton, S. P., Fabrikant, N., Rouspil, K. M., Langley, A. K., et al. (2016). Screening for trauma in early adolescence: findings from a diverse school district. Sch. Ment. Heal. 8, 89–105. doi: 10.1007/s12310-015-9169-5

Zhu, M., Liu, Q., Fu, Y., Yang, T., Zhang, X., and Shi, J. (2018). The relationship between teacher self-concept, teacher efficacy and burnout. Teach. Teach. 24, 788–801. doi: 10.1080/13540602.2018.1483913

Keywords: compassion fatigue, burnout, secondary traumatic stress, trauma, trauma-informed schooling, trauma-informed practice, efficacy, schools

Citation: Oberg G, Carroll A and Macmahon S (2023) Compassion fatigue and secondary traumatic stress in teachers: How they contribute to burnout and how they are related to trauma-awareness. Front. Educ. 8:1128618. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1128618

Edited by:

Gaylene Denford-Wood, Auckland University of Technology, New ZealandReviewed by:

Stacie Craft DeFreitas, Prairie View A&M University, United StatesFrancesco Chirico, Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, Italy

Copyright © 2023 Oberg, Carroll and Macmahon. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Glenys Oberg, Zy5vYmVyZ0B1cS5lZHUuYXU=

Glenys Oberg

Glenys Oberg Annemaree Carroll

Annemaree Carroll Stephanie Macmahon

Stephanie Macmahon