- 1College of Interdisciplinary Studies, Zayed University, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

- 2Sharjah Education Academy, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

The present study explores the experiences of Emirati female preservice teachers who are completing their internship teaching practice virtually due to the COVID-19 pandemic. This qualitative study focuses on virtual classroom management. Participants were preservice teachers (n = 18) completing their undergraduate degrees in Early Childhood Education at a federal university in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Data collected from interviews resulted in four themes related to classroom management: challenges, opportunities, performance factors, and suggestions for improvement. The findings revealed that the preservice teachers considered virtual learning an opportunity. However, the main challenge was that the preservice teachers had no prior training in online classroom management and had to create their own strategies. Training on the technology used for virtual learning is important for both teachers and students to achieve satisfactory learning experiences.

1. Introduction

It is unquestionably crucial for student teachers to complete training programs while still in school, before starting their future professions and managing actual classrooms on their own. In order to give preservice teachers the opportunity to observe a genuine classroom setting in its actual daily context, a practicum is typically included in preservice teacher training programs. The practicum’s main goal is to help preservice teachers develop their field experience skills while being coached by experienced educators. In the past 30 years, several colleges have embraced this more regularly (White, 2017).

Traditionally, most teacher education programs have assumed that teachers can learn everything they need to teach well by completing their programs of study, offering limited opportunities for practicing, often equated with a passive observation of lessons taught by expert professionals (Samu, 2020). However, many aspiring teachers give up their careers as soon as they are placed in classrooms because they find the experience to be extremely terrifying. Field experience, therefore, provides several options to overcome this problem (Taghreed and Mohd, 2017).

Mohebi and Meda (2021) reported that the provision of high-quality education is part of the UAE’s key national priority. One strategy for achieving this national target is to improve the availability of trainee teachers’ programs as this is the cornerstone for strengthening the education system.

Equivalently, Anderson et al. (2022) claimed that the experience of preservice teachers in the emergency online learning environment was expected to influence their perspectives of e-learning. Teachers’ past experience with e-learning technology is important because students may affect their perceptions about its potential usefulness for learning, future adoption, and usage as pedagogical tools (Anderson et al., 2022).

Kunter et al. (2007) and Junker et al. (2021) stated that although a supportive atmosphere and instructional support are key parts of teaching quality, classroom management is also a requirement for other quality indices (Junker et al., 2021). However, due to the lack of face-to-face contact, dealing with student behavior and attendance difficulties during synchronous learning sessions seems to be an obstacle (Hefnawi, 2022).

Ersin et al. (2020) indicated that the effectiveness of student teaching experiences affected teacher candidates in five categories: (a) pedagogical content knowledge, (b) planning and preparation for instruction, (c) classroom management, (d) promoting family involvement, and (e) professionalism. As such, preservice teachers learn about disciplinary techniques and classroom management through formal training and from their personal experiences. They develop effective classroom management from the duration of service in the related job. Therefore, it can be assumed that teachers will have better classroom discipline management throughout being in the teaching profession. Experience plays a significant role in exercising discipline management in the classroom (Rosilawati, 2013).

2. Literature review

2.1. Teaching online classes

With the outbreak of COVID-19, significant changes marked various aspects of human life, especially the educational systems worldwide. Face-to-face teaching ceased and gave way to a new form on a new platform with new factors. Unfortunately, preservice teachers were mostly at a great disadvantage since this sudden crossing from traditional to virtual classroom teaching occurred at a time when most teachers, educators, and supervisors were not that experienced and skilled in these practices (Sepulveda-Escobar and Morrison, 2020).

Moreover, novice and trainee teachers faced many challenges in their endeavor to harness the newly sought skill of teaching while applying taught educational methods in the new normal of online teaching (Baran and AlZoubi, 2020; Mohamad Nasri et al., 2020; Samu, 2020). These challenges included designing appropriate, differentiating, and effective social tasks for the online environment, managing classroom interaction, and engaging with the electronic constraints of the available platforms such as videoconferencing, live chats, Zoom, or Skype (König et al., 2020; Samu, 2020; Scull et al., 2020). To address these issues, several institutions provided their practicum courses using the reflection-on-action methodology, with their students serving as observers for the online sessions of the professionals (Özkanal et al., 2020). Others employed simulations to hone the classroom management abilities of preservice teachers, providing exceptional opportunities for teaching skill development and reflection (Finn et al., 2020). Furthermore, some educators chose to confront the difficulties brought on by the unexpected acceleration of the rise of teaching and learning online, giving their students an actual and practical field trial so they could adjust accordingly (Baran and AlZoubi, 2020; Mohamad Nasri et al., 2020). According to Kim (2020), “Online teaching experiences provided these preservice teachers with opportunities to interact with children, as well as to encourage reflection on how best to promote young children’s development and learning with online communication tools” (p. 145).

Additionally, current student teachers who will soon be instructors have grown up in a technologically advanced period and are quite familiar with technology’s use and applications (Margaliot and Gorev, 2020). However, they encounter challenges in integrating their technological abilities into the workplace when it comes to utilizing their knowledge in active online teaching (Martin et al., 2019). Uniformly, Harasim (2017) stated that although new social communication technologies and media have been embraced in day-to-day life, these tools and platforms have remained limited when it comes to implementation in teaching and learning (Harasim, 2017). As such, it was only in the last two decades that online education grew rapidly (Allen and Seaman, 2014). The online blended mode, which was available to both on-campus and off-campus students, began to affect students (Zawacki-Richter and Anderson, 2014), forcing higher education institutions to shift their emphasis from ensuring that students had access to their education to improving its quality (Lee, 2017).

It is noteworthy to mention that the methods and practices applied in blended and online teaching are quite different from the traditional approaches followed in face-to-face learning settings Thus, the way the teachers are prepared for their teaching is relevantly reflective of the quality of their instructions (Gurley, 2018). According to Dorsah (2021), preservice teachers’ readiness for emergency remote teaching is high, yet “they recorded low readiness in dimensions of learner control, computer/internet self-efficacy, and online communication self-efficacy” (Dorsah, 2021, p.10); thus it adds that a mentor or a coach is vital in facilitating and guiding the student teacher to shift from uncertainty to a supportive, collaborative, and participatory learning space (Baran and AlZoubi, 2020; Ersin et al., 2020). Baran et al. (2011) found that “increasing teacher presence for monitoring students’ learning,” “increasing organization in course management,” “increasing structure,” and “reconstructing student-teacher relationships” are the most prominent sides of pedagogical change when teaching moves from face-to-face to online (p. 5). Similarly, based on recent studies, the following three factors are crucial for effective online teaching: (1) compassionate social interaction, (2) appropriate planning, and (3) pertinent execution (Baran and AlZoubi, 2020; Ogbonnaya et al., 2020; Dorsah, 2021; Hojeij and Baroudi, 2021). Similarly, Hodges et al. (2020) stated that the main factors in distance learning caused by a health emergency appear to be ongoing planning and design of online courses, on-the-spot modifications to in-person courses, and familiarity with new technologies for teaching and learning (Sepulveda-Escobar and Morrison, 2020).

Salmon (2000) developed a five-stage model detailing the tasks that e-moderators have to walk their students through to improve the quality of the online teaching experience: access and motivation, online socialization, information exchange, knowledge construction, and development. This learning paradigm moves across preparatory steps through knowledge acquisition and collaborative work where the learners end up responsible for their learning.

This is in line with the literature that emphasizes the constant effort spent on teaching tasks, such as classroom management, monitoring and assessing learner performance, course clarification, and continuity (Baran et al., 2013).

2.2. Classroom management in virtual settings

The tremendous intricacy of teaching is evident to anybody who has ever faced a classroom full of children while bearing the entire weight and duty of directing and motivating their learning. Even though teaching objectives may be pre-planned, the actual process of instructing students to attain those objectives often takes the form of a succession of unpredictable occurrences, which teachers might interpret in a variety of ways. The plan foresees some occurrences, while others come forth as a result of the unexpected. Being aware of these things, how they develop through time, and how they affect learning may be a key element in effective classroom management (Wolff et al., 2020).

In their definition of classroom management and as cited in Korpershoek et al. (2014), Evertson and Weinstein (2006) allude to the steps instructors take to provide a conducive atmosphere for students’ academic and social–emotional growth. They list five different kinds of acts. Teachers must (1) cultivate warm, receptive connections with and among students and (2) plan and carry out teaching in ways that maximize students’ access to learning in order to achieve a high standard of classroom management.

Classroom management skills are extremely important in achieving efficient classroom instruction and they correlate with students’ learning process in the classroom (Marzano et al., 2003). To increase students’ success in schools, teachers should acquire classroom management systems to create a learning environment that enhances both the academic skills and social–emotional development of students (Milliken, 2019). Unfortunately, research indicates that most teacher preparation programs spend minimal time on classroom management instruction. It has also been proven that well-managed classrooms lead to students that are engaged and who will attain high achievement (Milliken, 2019).

Because of all the abovementioned changes in this decade, computer-assisted language learning (CALL) has become a central aspect of teacher training since preservice teachers need to learn how to plan an online course, how to implement online methodologies and teaching techniques coherently with learners’ needs, and how to manage a live online classroom (Samu, 2020). Utilizing CALL software is crucial because it makes it possible to promote critical thinking, self-access, and communication in the target language. CALL assumes interactive communication in which exercises are immediately corrected to allow the student to move on to other tasks, or if the answer is incorrect, the student should be given the appropriate feedback in the form of a rule, an example, a new trial, or the right answer and error explanation. As a result, CALL software might be used as an optional, complimentary component of a distance-learning language course (Seljan et al., 2006; Jarvis and Achilleos, 2013).

Finally, on the importance of classroom management in virtual classrooms, a study by Ersin et al. (2020) showed the four major e-practicum areas that teachers were mainly concerned about (i) the challenges of e-practicum and the unique experience that comes with them, (ii) learning how to overcome online technical problems, (iii) classroom management in a virtual classroom, and (iv) the necessity of such an experience for their future career.

2.3. Challenges

Relationships are the core of successful teaching and learning. Teaching and learning occur with the interaction between teachers and students, and in the case of student teachers, with other members of the school community as well (Sepulveda-Escobar and Morrison, 2020). However, one of the difficulties with online learning that was cited by both teachers and students was the limited options for interaction (Hebebci et al., 2020). This was also shown by Samu (2020), who stated that the lack of physical interaction with students, as well as the potential issues that are associated with managing the affective component of these interactions, is one of the major challenges faced by preservice teachers (Samu, 2020). Similarly, Sepulveda-Escobar and Morrison (2020) declared that preservice instructors reported feeling very anxious and having less willingness to teach due to the absence of direct engagement with students. It also made it difficult for them to prepare and alter lesson plans, and they were unable to put the classroom management techniques they had learned during their teaching preparation program to use. In addition, the study by Scull et al. (2020) reported that many preservice instructors allegedly suffered from the absence of actual classroom instruction, with them mostly complaining about the lack of behavioral problems that would occur in actual classroom settings, which prevented them from putting theory into practice, particularly their classroom management techniques.

In addition, Rosilawati (2013) claimed that it could be difficult for preservice teachers to manage discipline-related problems at the beginning of their work experience, particularly during the lessons as they must ensure that students are engaged in learning at the same time (Rosilawati, 2013). Generally, novice teachers feel unprepared to establish a structured classroom environment, engage students in learning, and deal with challenging behavior. Thus, it is very clear that classroom management issues are a serious challenge for novice teachers; disorderly learning spaces, disrespectful interactions, and disruptive student behavior lead to chaos—ultimately draining instructional time (Milliken, 2019). As a result, effective classroom management training is required for teachers to cope with everyday obstacles, especially because many starting teachers join the field of education lacking the abilities required to develop an effective classroom management plan and respond correctly to student conduct. Inadequate and ineffective preservice teacher education has been criticized for new teachers’ lack of classroom management competency (Milliken, 2019).

2.4. Strategies

The current pandemic forced educators to move the traditional and mostly comfortable face-to-face setting to a virtual setting without prior preparation. Thus, if preservice teachers are not familiar with and competent in virtual teaching, they will fail as teachers, so it is crucial to generate suitable strategies for making online teaching successful. A more collaborative and sustainable approach of cooperation between schools and universities that creates and develops suitable strategies to carry out online teaching during a health emergency would surely strengthen the education of both preservice teachers and their learners (Sepulveda-Escobar and Morrison, 2020). Preservice teachers have to learn how to adapt to unexpected situations, how to work with different digital platforms, and how to design strategies to try and reach their students without actually seeing them. Hence, teacher education programs have a significant role in providing opportunities to build a continuum of teacher–pupil encounters to help future teachers become aware of emergent classroom strategies (Sepulveda-Escobar and Morrison, 2020).

The development of student teachers’ teaching competency and abilities places high importance on the practical portion of teacher education. They have the chance to refine their teaching skills via this practical experience. Students who are also teaching cherish this opportunity to put theory into practice. Consequently, it is here that classroom management is learned (Sepulveda-Escobar and Morrison, 2020). Nevertheless, due to poor classroom management, some teachers fail to deliver their classes as intended despite possessing in-depth topic knowledge. Because of this, teachers need to possess the following three fundamental abilities: prepositional knowledge, procedural knowledge, and conditional knowledge. Prepositional knowledge is the understanding of principles for efficient classroom management. Procedural knowledge is the application of classroom management knowledge by instructors. Conditional knowledge is the understanding of conditions.

Furthermore, it is obvious that preservice teachers must be emotionally and physically prepared for their practicum sessions. They must provide engaging activities in order to engage students, be personable, and learn the names of the students. They should also practice methods for “punishing” inappropriate behavior and rewarding or promoting appropriate behavior (Milliken, 2019). Therefore, effective teachers should employ a range of strategies for various types of students. Conversely, unsuccessful teachers use the same techniques with each and every pupil. Student involvement in the classroom may thus be increased by effective classroom managers.

Samu (2020) stated that increasing teacher–student and student–student interaction during an online course is another helpful strategy that delivers a learning experience similar to face-to-face instruction (Samu, 2020). As a result, preservice teachers must be taught how to organize and manage activities that engage participants in continuing discourse (Samu, 2020). Good lesson preparation, understanding how to include students, and knowing how to ask questions that encourage involvement are all essential components of effective classroom management. A teacher should be able to keep students interested throughout online lessons, avoid daydreaming, and manage students’ attention spans because poor classroom management can interfere with the flow of any instruction (Ersin et al., 2020).

2.5. Best practices

The term “best practice” is not agreed upon by everybody. However, according to the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), best practices share four traits: they are innovative, make a difference, have a lasting impact, and have the potential to be replicated and used as a model for launching initiatives elsewhere. A best practice must guarantee the delivery of the greatest favorable result when used to treat a specific ailment, and it must be based on repeatable steps or activities that have been successfully used by many individuals over time (Baghdadi, 2011).

According to Milliken (2019), gaining self-efficacy enhances the teaching and learning process and boosts work satisfaction, all of which will ultimately lead to higher student outcomes. Preservice instructors must, therefore, take charge of the classroom environment by fostering student motivation and ensuring their comprehension, attention span, and desire to study. A recent review identified clear, consistent expectations for students, effective behavior corrections, and positive teacher–student relationships as the three most successful methods for research-based classroom management. Hojeij and Baroudi (2021) mentioned that teachers should put engagement first while instructing online and they can do so by keeping an eye out for both the students who are speaking out at the same time and the more reticent speakers who could be more easily missed. Therefore, before going on to the next topic, teachers should pause and ask if anyone has any more views on the topic being discussed. Teachers may also invite outside speakers who are authorities in related subjects to participate in the class. This will encourage zeal, inspiration, inclusivity, and involvement. A requirement for participation in the classroom community is asking students to switch on their webcams.

If, however, some students feel uncomfortable sharing their living/studying circumstances, teachers should remind students to use virtual backgrounds that can help protect privacy, improve equity, and reduce visual distractions. Teachers should also encourage students to stretch for 30 s every 20 min or so. Furthermore, teachers should encourage students to raise their hands or ask questions throughout the class by urging them to use the discussion features. Furthermore, by using the whiteboard capability to digitally annotate, teachers and students may brainstorm and solve problems together. Like in conventional classrooms, teachers are permitted to make a cold call to a student rather than waiting for them to raise their hands. Finally, studying from home presents difficulties for learner engagement given that children have short attention spans. Therefore, relying on active learning, presenting lessons in bite-sized portions rather than lengthy lectures, and using technology-based teaching strategies, including tools such as mixed media, gamified components, video clips, surveys, and so on, are the ideal options in this case.

2.6. Research questions

1. What challenges did preservice teachers face with their classroom management in virtual settings during COVID-19?

2. What are preservice teachers’ perceptions about the successes of their classroom management in virtual settings during COVID-19?

3. Methodology

3.1. Research design

According to Creswell (2013), a case study design involves participants depicting their experiences. The researcher’s role is to describe the recurring patterns and themes. The main point of the research is to understand how people lived through the experience from their own perspective by joining the inner world of each participant (Christensen et al., 2014). Hence, a qualitative approach was adopted to explore the lived experiences of preservice teachers in terms of classroom management in a virtual setting due to COVID-19.

3.2. Context

This research was conducted at an Early Childhood Education Program at the College of Education in a public university in the United Arab Emirates (UAE). This program requires preservice teachers to complete four field experience placements during their course of study. The preservice teachers are placed in an early childhood education setting, usually between grades 1 and 3. The last placement is a full-semester internship spanning 15 weeks of full school instruction and an intervention action research component.

This study was conducted during the internship field experience placement which took place in Spring 2021 over a period of 15 weeks. The preservice teachers were placed in a public elementary school in different grade levels and with different teacher mentors. They had 15 consecutive weeks of full teaching under the guidance of their mentor teachers. In the UAE, public schools opted to use Microsoft Teams for their virtual teaching platform. The preservice teachers were all accustomed to Microsoft Teams and its capabilities as they had used it in their previous field experience placements.

The preservice teachers were given the curriculum plan of the class and had to follow it with the help of their mentors. The mentor teachers were always present in the virtual classroom with no exceptions. Daily lessons were all synchronous.

3.3. Participants

The participants were 18 Emirati female preservice teachers who were attending their final semester internship field experience placement in the teacher preparation program. All student teachers were teaching online full-time, at the same time, as a part of their internship placement. Participants were all “bilingual speakers of Arabic and English,” and Arabic was their first language. They were all enrolled in the Early Childhood Education program at the College of Education in a public university in the UAE. Their ages ranged between 18 and 21 years.

The researcher followed a convenience sampling method to select the participants. The participants were chosen from one class because they were one of the first groups to make it to the full 15 weeks of teaching virtually. They were chosen for ease of access to data collection, as well as their longer experience than other preservice teachers in the program. These participants had spent their first field experience in a face-to-face setting and as such could compare the two methods of teaching and learning, especially in terms of classroom management.

3.4. Data collection

The data were collected through semi-structured interviews based on open-ended questions to allow participants to describe and elaborate on their classroom management experiences during their virtual internship. The interview instrument was designed by the researcher based on the literature and consisted of 12 open-ended questions. Participants were asked about their virtual classroom management practices during COVID-19, focusing on skills, strategies, challenges, strengths, and weaknesses. Each interview lasted for an average of 30–45 min.

After obtaining ethical clearance approval from Zayed University Ethical Clearance Committee (ZU20_125_E), participants were invited via email for their participation and consent. Participants read and signed the informed consent documents before the interviews. In addition, at the onset of the recorded interview, verbal consent was again obtained, and anonymity was guaranteed. They were also assured that participation had absolutely no influence on their grades and that participation in the study was voluntary and there were no influences on the teacher training course.

The interviews were conducted in English and recorded through the Zoom platform. Recordings were saved on the main researcher’s password-protected cloud account. The collected data and its interpretation were conveyed to the participants to ensure credibility.

3.5. Data analysis

The data collected from the semi-structured interviews were manually transcribed and coded by the first author following a thematic analysis approach. No digital tools were used.

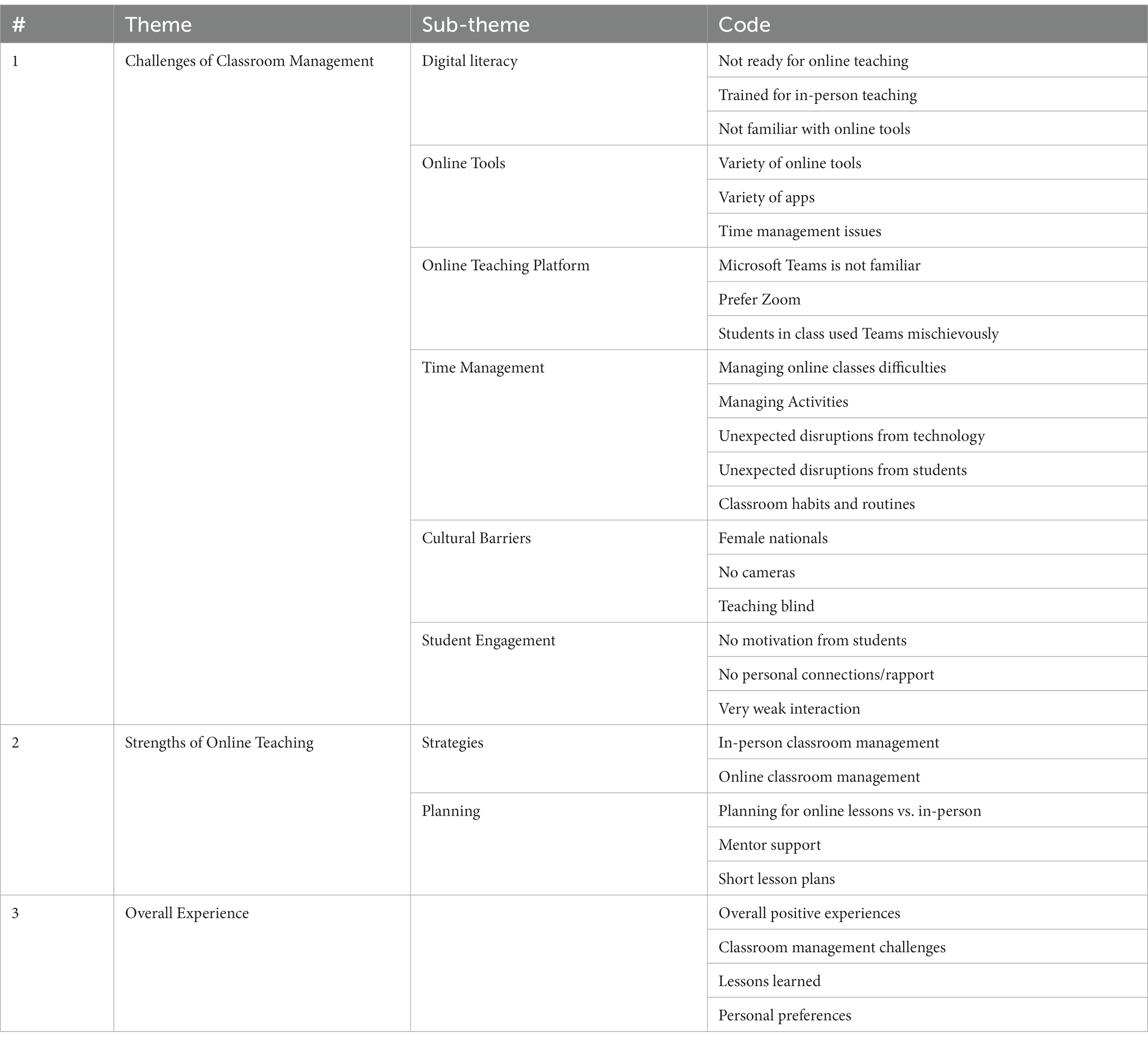

Creswell (2008) explained that thematic analysis is when the researcher reads through the data many times to have a full understanding of the phenomenon in order to divide each text into segments of information and then code them as a way to indicate patterns and meaning. The main researcher and one of the co-authors were involved in the coding process to ensure a credible and reliable analysis. The two coders approached the data with preconceived categories (i.e., challenges, strategies, strengths, and weaknesses), and began analyzing the data by coding text units according to what they expected to find. However, they kept the coding open for any emergent or unexpected themes. The coders met several times to compare the codes, merge the ones that overlapped, and reach an agreement on the main and emergent themes. As a result, a total of three themes and six sub-themes were identified.

4. Results

A case study approach was adopted where participants described their experiences, specifically related to their classroom management during their virtual teaching experience during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings of the study are divided into three main themes and six sub-themes which align with the three research questions, as seen in Table 1 below.

4.1. Theme 1: Challenges of Classroom Management

Based on participants’ interviews, there were many challenges during the virtual teaching experience, especially in terms of classroom management. These obstacles are presented below under the following sub-themes: digital literacy, time management, cultural barriers, and student engagement.

4.1.1. Digital literacy

The majority of the participants (n = 16) indicated that they were not ready to teach online. They had been training for in-person teaching and their skills were not fully developed to equip them to deal with classroom management in the virtual class. Preservice teachers highlighted during their interviews that technology posed a major challenge to their classroom management. They mentioned the difficulties they faced with the online tools used at their schools, e.g., one respondent stated that “We used the many online tools, and this was a problem for me because I had to focus on the lesson, the technology, and the students. This made me nervous because I was not sure of all the apps they used at the school, and I had to use them online now. I could not control my class because I was busy with trying not to make mistakes with the apps.” (P3).

Respondents also had concerns regarding the teaching platform adopted by the Ministry of Education for UAE public schools. As one participant noted:

“In the school, they use so many apps in the online class. This is not good for me because I was so worried about the lesson plan and finishing my objectives. At the same time, the tools were so many, and I needed to know them all because the students know how to use them, and if I make a mistake, I lose the class. I had a hard time with managing.” (P7).

Another participant noted that:

“Sometimes the students were not ready to join Teams on time. They also were able to mute me and to kick me out of the class. I did not like Teams at all. I think if we used Zoom, it’s better.” (P2).

4.1.2. Time management

The majority of participants (n = 15) had issues with readiness to manage an online class, especially in terms of time management. In particular, participants mentioned their failure in managing the lesson time while they needed to keep track of the activities and control any unexpected disruptions from the technology or students. This has had consequences on their confidence and satisfaction in teaching online, as mentioned below in their comments.

“I could not stay on time! It was so hard for me to manage everything I had to do and worry about the time as well. This was my biggest problem in the online class. Trying to follow the time of the activities on my lesson plan was so hard for me.” (P1).

“In the regular class, we set habits and routines that happen at a specific time in the class. For example, when we come into the class face-to-face in the morning, one student writes the date, another takes attendance, and like this, in my virtual class, I could not do this. There was no time at all to do any of the class routines. Because if I did these, I will lose my time and not finish my lesson. Also, the students were not really interested in the class routines.” (P15).

“My biggest problem was managing activities and making sure they finish on time. It took me too long to set the expectations and rules of the activities because there were so many disruptions all the time. So much of my time was spent trying to control the disruptions to the lesson. That is why I lost so much time.” (P18).

4.1.3. Cultural barriers

In terms of cultural barriers, all participants were well aware of the restrictions they had to abide by as female Emirati nationals themselves. These were expressed in some of their replies below.

“The students do not turn on their cameras, so I do not know what they are doing. I cannot see them, and they cannot see me. It is teaching in the dark. It was hard to teach like that, the class was difficult.” (P5).

“In our culture, women cannot be pictured. So, I had to teach with my camera off. Also, the students were the same. They cannot turn on their camera, so we do not see their house or their family. Sometimes, they had a dad or a brother with them to help them and it’s not allowed for them to see us or for me to see them. It’s not a good way to have a class but this is the Arabic culture, and we cannot change.” (P8).

4.1.4. Student engagement

Student engagement posed an additional challenge to the participants. Approximately 88% of replies (n = 16) indicated that students were not engaged in the online classroom. They expressed their dissatisfaction with the motivation of the students and how this affected their lessons negatively. Some of the replies are below.

“Relationships with the students are difficult in the online classroom. I could not make a connection with them. We learned we have to establish a connection but in the real classroom, it is easy because we can see them and do things together. In the online class, there are less chances for interaction.” (P10).

“The students are not interested and not motivated. They do not like the online class. They are distracted and they keep logging in and out of the class the whole time. There is not so much student engagement. Even when we try to do group work, they are not motivated, and they do not listen to my instructions.” (P16).

4.2. Theme 2: strengths of online teaching

The second topic, which emphasized the advantages of online teaching, produced the sub-themes of planning and strategies. The majority of the participants (89%, n = 16) stated overall satisfaction with the planning abilities and classroom management techniques they employed. According to participant replies, getting to put the methods they had learned in their preparatory classes into practice was a useful opportunity. Additionally, because the lessons were brief and they had to collaborate with their mentors in order to develop them, planning for the online classroom was a unique experience. However, as can be seen below, responses indicate the overall worth of this.

4.2.1. Strategies

“My class was successful sometimes and other times no. But I practiced some of the strategies for classroom management that we learned in class at the university.” (P4).

“The strategies I used to control my class were good. We learned many good ways to run out class in the course at the university and I tried them in my online class. Many worked so I felt good.” (P8).

4.2.2. Planning

“Some activities were fun to plan. I did well on my lesson plans, and I was able to do my activities well. After I plan the lesson, I sit with my mentor from school (on Zoom) and she helped me with the lesson plan. I learned a lot about how to teach a class online from her.” (P10)

“The online classes were short, like 35 minutes or something like that. They were easy to plan because they were short. I liked the planning of the lessons and l learned how to make a plan for an online class.” (P6)

“The online class is very different and the activities we do are also different from the real classroom. It didn’t take a long time for me to learn how to plan for the online class and what activities I can do. I did well in my planning. My mentor teacher always said I did good.” (P9)

4.3. Theme 3: overall experience

In general, the preservice teachers had overall positive experiences during their virtual practice teaching placement. However, despite all the positives, there were still many challenges in the online class especially related to classroom management as indicated by 12 of the participants (67%). Some of their comments are below.

“I think teaching online was a good practice for me. COVID gave me something good. If we did not have the pandemic, my practice will only be in person, and I will never learn how to teach online.” (P11)

“The online teaching is very different from the teaching in-person. I prefer in-person. But because of COVID, I had no choice. I learned how to plan a lesson for online class. I also learned how to manage my class and deal with kids who disrupt the class. I learned how to teach on Teams. I mean teaching online was a good experience, but I prefer the real classroom of course.” (P13)

In contrast, some of the preservice teachers (n = 6) did not enjoy the virtual teaching experience. Their opposing comments are as follows.

“I faced many challenges in managing my online class. The kids were never on time, they didn’t take the class seriously. They keep going in and out of the class and saying they have connection issues. The big problem for me was the camera. I could not see them or what they are doing. It didn’t feel like they were learning anything. It is like the students had more control over the class than the teacher. I didn’t like it at all.” (P16)

“I do not like teaching online at all. It is much harder than teaching in class. There is a hard time to make the lesson and to manage the kids. They do not pay attention. They do not want to be online.” (P15).

5. Discussion

Having strong classroom management skills is the core of an efficient teaching and learning environment as it is directly correlated with students’ engagement and learning (Marzano et al., 2003; Milliken, 2019). In online learning, many factors come in place that would impact teachers’ abilities to manage an online classroom, such as teachers’ implementation of online methodologies that are coherent with learners’ needs and students’ motivation to learn (Samu, 2020). This study explored the challenges that preservice teachers faced in virtual settings and investigated perceptions about their success in classroom management. This was important to address due to the seriousness of this issue for novice teachers in particular (Marzano et al., 2003). Similar to Samu (2020), the findings of Dai and Xia (2020) revealed the extent that limited digital literacy can impact teachers’ abilities to manage the virtual classroom. Knowing the use of technological resources is a key pillar in the framework for preparing preservice teachers for online teaching (Hojeij and Baroudi, 2021):

1. The findings showed that student engagement posed an additional challenge to 88% of the participants and this result aligns with the studies by Baroudi and Shaya (2022) and Robinson and Hullinger (2008) which stated that engaging students during online instruction is a key concern for researchers and practitioners as it impacts teachers’ performance in the virtual classroom, job fulfillment, and satisfaction.

2. Preservice teachers’ time management for instructional tasks has been impacted by a lack of digital literacy. According to Dai and Xia (2020), it is critical to train instructors on how to use digital platforms in order to boost their confidence in planning online education and keeping track of class time. However, the findings of this study show that this has yet to be implemented. Furthermore, the findings revealed that preservice teachers struggled with the internet resources that their schools used.

3. Limited knowledge in using the technology has negatively impacted participants’ self-confidence and satisfaction in online teaching as they felt that they were incapable to teach online. Teachers’ satisfaction with online teaching has been recently investigated as it is related to their self-efficacy levels (Baroudi et al., 2022). The recent pandemic and the consequences it has had on the education sector opened the eyes of policymakers and school leaders to the importance of increasing educators’ ability to perform their job even during the most challenging situations, in other terms, self-efficacy. Hence, if teachers were prepared to use the technology, they would perform better under unexpected situations (i.e., internet disruptions), which would elevate their satisfaction and performance (Bandura, 1994).

An important finding here highlights that for novice teachers as for their more experienced counterparts, the online learning environment hindered their capacities to promote students’ social and emotional development. This is also another reason why preservice teachers expressed their discontent about managing the online classroom (Sepulveda-Escobar and Morrison, 2020). It is also important to include the affective aspect of learning within teachers’ teaching practices, which is integrated into teachers’ interactions and practices inside the class when teachers, for instance, encourage and motivate students, ask about their feelings and concerns, and relate relevant personal experiences (Samu, 2020). As such, to enhance novice teachers’ classroom management skills, teaching preparation programs must equip them with teaching practices that would promote emotional development among students due to its short- and long-term benefits toward their engagement, sense of belonging, and overall performance (Milliken, 2019).

On another note, increasing students’ social development by building positive teacher–student and student–student relationships in the online classroom is another path to nurturing positive emotions and reducing disruptive behaviors. Sadly, the results of this study showed that preservice teachers struggled in managing the classroom mainly due to disruptive students’ behaviors and because they were “teaching in the dark” as described by one participant. Turning off the cameras for both the instructor and the students for the duration of the course was a major disadvantage that hampered preservice teachers’ skills to properly manage the online classroom since they could not interact with the students or create strong connections with them. This issue increased students’ disobedience and disturbances, causing instructors psychological discomfort through the negative sentiments expressed in participants’ responses, which are thought to have influenced their own ideas and beliefs about teaching in general (Paramita et al., 2020).

Despite these hurdles, online teaching was a positive learning opportunity for preservice teachers as it trained them to work under pressure and find immediate solutions to disruptions that threatened their classroom management abilities. It prepared them to become more adaptable and flexible, take risks, make decisions, and learn from their mistakes. All of which are skills needed to increase their resiliency and self-efficacy levels so they can sustain their performance in unexpected situations.

The study’s main finding, in summary, was that preservice teachers had pedagogical, technical, and social–emotional issues that overshadowed their potential. One of these was maintaining an interesting virtual classroom for the students. This study also demonstrated that successful online course management and teaching depend on participants receiving adequate and pertinent training and information about developing purposeful asynchronous learning resources, technology pedagogical understanding, and obligations related to the roles they will play in online learning.

6. Conclusion

The purpose of this study was to explore the experiences of Emirati female preservice teachers who were completing their internship teaching practice virtually due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The study’s findings show that, despite the difficulties they faced, most preservice teachers (67%) were able to effectively operate and deliver online classes. Their triumphs and possibilities greatly surpassed whatever difficulties they faced. Moreover, the study’s findings revealed that preservice teachers benefited from the global COVID-19 epidemic because it sparked their interest in online education and gave them the skills they needed for blended learning, which is now widely used. However, it was considered disappointing that the education system suffered unspeakable losses that decreased the likelihood of achieving the fourth sustainable development goal, and children with special needs took the brunt of the rapid change in curriculum. Despite this, it is important to note that effective teaching and classroom management is possible in a setting where inexperienced teachers are fully supported and motivated by their school mentors and university supervisors to perform at their best.

7. Implications, recommendations, and limitations

Although this study focused on the time when COVID-19 was at its peak, when many countries were under lockdown, the results of the research have implications for current teaching and learning. The study implies that teacher training institutions must step up their efforts to promote blended learning with more focus on online learning. This will prepare preservice teachers so that they gain comprehensive knowledge, pedagogical skills, and technological skills to be able to teach effectively when they graduate. Training students on using technological tools and pedagogical skills play a significant role in teachers as it improves their self-efficacy beliefs in online teaching (Baroudi and Shaya, 2020).

It is recommended that trainee teacher institutions reconsider their curricula to make sure that they include technological literacy, allowing students to graduate with significant knowledge about online and blended teaching. Institutions must strive to ensure that the curricula sufficiently cover all the 4Cs (critical thinking, collaboration, creativity, and communication) of the 21st century.

The study was limited to a federal institution in the UAE where students were only women. That was the first limitation. The second limitation is that researchers did not collect data regarding preservice teachers’ abilities to create authentic learning opportunities or collaborative learning opportunities as these are key to ensuring a positive learning environment and successful classroom management.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Zayed University Ethics Committee. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

ZH, SB, and LM contributed to the writing of this manuscript. ZH took the lead in the project and completed the literature review, data collection, data analysis, results, and revised and edited the manuscript. SB completed the revision of the literature review and the methodology section. LM completed the third review of the literature review and the discussion draft. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Allen, I., and Seaman, J. (2014). Grade change: Tracking online learning in the United States Babson Survey Research Group and Quahog Research Group Available at: http://www.onlinelearningsurvey.com/reports/gradechange.pdf

Anderson, P. J., England, D. E., and Barber, L. D. (2022). Preservice teacher perceptions of the online teaching and learning environment during COVID-19 lockdown in the UAE. Educ. Sci. 12:911. doi: 10.3390/educsci12120911

Baghdadi, Z. (2011). Best practices in online education: online instructors, courses, and administrators. Turkish Online J. Distance Educ. Available at: https://dergipark.org.tr/en/download/article-file/156038

Bandura, A. (1994). “Self-efficacy” in Encyclopedia of human behavior. ed. V. S. Ramachandran (New York: New Academic Press).

Baran, E., and AlZoubi, D. (2020). Human-centered design as a frame for transition to remote teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Technol. Teach. Educ. 28, 365–372.

Baran, E., Correia, A., and Thompson, A. (2011). Transforming online teaching practice: Critical analysis of the literature on the roles and competencies of online teachers, Distance Educ. 32, 421–439. doi: 10.1080/01587919.2011.610293

Baran, E., Correia, A. P., and Thompson, A. D. (2013). Tracing successful online teaching in higher education: voices of exemplary online teachers. Teach. Coll. Rec. 115, 1–41. doi: 10.1177/016146811311500309

Baroudi, S., and Hojeij, Z. (2022). “Innovative practices implemented by preservice teachers during their field experience: lesson learnt from face-to-face and online field placement” in Handbook of research on teacher education: Pedagogical innovations and practices in the Middle East. ed. M. S. Khine (Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore), 141–152.

Baroudi, S., Hojeij, Z., Meda, L., and Lottin, J. (2022). Examining elementary preservice teachers’ self-efficacy and satisfaction in online teaching during virtual field experience. Cogent Educ. 9:2133497. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2022.2133497

Baroudi, S., and Shaya, N. (2022). Exploring predictors of teachers’ self-efficacy for online teaching in the Arab world amid COVID-19. Educ. Inf. Technol. 27, 8093–8110. doi: 10.1007/s10639-022-10946-4

Christensen, L. B., Johnson, R. B., and Turner, L. A. (2014). Research methods, design, and analysis. 12th Edn. Boston: Pearson.

Creswell, J. W. (2008). Educational research: Planning, conducting and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. 3rd Edn. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Merrill Prentice Hall.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry design: Choosing among five approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Dai, D., and Xia, X. (2020). Whether the school self-developed e-learning platform is more conducive to learning during the COVID-19 pandemic? Best Evid. Chin. Educ. 5, 569–580. doi: 10.15354/bece.20.ar030

Dorsah, P. (2021). Preservice teachers’ readiness for emergency remote learning in the wake of COVID-19. Eur. J. STEM Educ. 6, 1–12. doi: 10.20897/ejsteme/9557

Ersin, P., Atay, D., and Mede, E. (2020). Boosting preservice teachers’ competence and online teaching readiness through E-practicum during the COVID-19 outbreak. Int. J. TESOL Studies 2, 112–124. doi: 10.46451/ijts.2020.09.09

Evertson, C. M., and Weinstein, C. S. (Eds.) (2006). Handbook of classroom management. Research, practice, and contemporary issues. New York: Larence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Finn, M., Phillipson, S., and Wendy, G. (2020). Reflecting on diversity through a simulated practicum classroom: a case of international students. J. Int. Stud. 10, 71–85. doi: 10.32674/jis.v10iS2.2748

Gurley, L. E. (2018). Educators’ preparation to teach, perceived teaching presence, and perceived teaching presence behaviors in blended and online learning environments. Online Learn. 22, 197–220. doi: 10.24059/olj.v22i2.1255

Harasim, L. (2017). Learning theory and online technologies. 2nd Edn. New York: Routledge Falmer, Taylor & Francis Group.

Hebebci, M. T., Bertiz, Y., and Alan, S. (2020). Investigation of views of students and teachers on distance education practices during the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Int. J. Technol. Educ. Sci. 4, 267–282. doi: 10.46328/ijtes.v4i4.113

Hefnawi, A. (2022). Teacher leadership in the context of distance learning. Manag. Educ. 36, 94–96. doi: 10.1177/0892020620959732

Hodges, C. B., Moore, S., Lockee, B. B., Trust, T., and Bond, M. A. (2020). The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning VTechWorks. Available at: https://vtechworks.lib.vt.edu/bitstream/handle/10919/104648/facdev-article.pdf?sequence=1

Hojeij, Z., and Baroudi, S. (2021). Engaging preservice teachers in virtual field experience during COVID-19: designing a framework to inform the practice. Int. J. Distance Educ. Technol. 19, 14–32. doi: 10.4018/IJDET.2021070102

Jarvis, H., and Achilleos, M. (2013). From computer assisted language learning (CALL) to Mobile assisted language use (MALU). Electron. J. English Second Lang. 16, 1–18.

Junker, R., Gold, B., and Holodynski, M. (2021). Classroom management of pre-service and beginning teachers: from dispositions to performance. Int. J. Mod. Educ. Stud. 5, 339–363. doi: 10.51383/ijonmes.2021.137

Kim, J. (2020). Learning and teaching online during Covid-19: experiences of student teachers in an early childhood education practicum. Int. J. Early Child. 52, 145–158. doi: 10.1007/s13158-020-00272-6

König, J., Jäger-Biela, D. J., and Glutsch, N. (2020). Adapting to online teaching during COVID-19 school closure: teacher education and teacher competence effects among early career teachers in Germany. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 43, 608–622. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2020.1809650

Korpershoek, H., Harms, T., de Boer, H., van Kuijk, M., and Doolaard, S. (2014). Effective classroom management strategies and classroom management programs for educational practice. Groningen: GION onderwijs/onderzoek.

Kunter, M., Baumert, J., and Köller, O. (2007). Effective classroom management and the development of subject-related interest. Learn. Instr. 17, 494–509. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2007.09.002

Lee, K. (2017). Rethinking the accessibility of online higher education: a historical review. Internet High. Educ. 33, 15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2017.01.001

Margaliot, A., and Gorev, D. (2020). Once they’ve experienced it, will pre-service teachers be willing to apply online collaborative learning? Comput. Sch. 37, 217–233. doi: 10.1080/07380569.2020.1834821

Martin, F., Gezer, T., and Wang, C. (2019). Educators’ perceptions of student digital citizenship practices. Comput. Sch. 36, 238–254. doi: 10.1080/07380569.2019.1674621

Marzano, R. J., Marzano, J. S., and Pickering, D. J. (2003). Classroom management that works: Research-based strategies for every teacher. New York: ASCD.

Milliken, K. (2019). The implementation of online classroom management professional development for beginning teachers. doctoral thesis, Abilene Christian Univesity. Available at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/etd/177/.

Mohamad Nasri, N., Husnin, H., Mahmud, S. N. D., and Halim, L. (2020). Mitigating the COVID-19 pandemic: a snapshot from Malaysia into the coping strategies for pre-service teachers’ education. J. Educ. Teach. 46, 546–553. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2020.1802582

Mohebi, L., and Meda, L. (2021). Trainee teachers’ perceptions of online teaching during field experience with young children. Early Childhood Educ. J. 49, 1189–1198. doi: 10.1007/s10643-021-01235-9

Ogbonnaya, U. I., Awoniyi, F. C., and Matabane, M. E. (2020). Move to online learning during COVID-19 lockdown: preservice teachers’ experiences in Ghana. Int. J. Learn. Teach. Educ. Res. 19, 286–303. doi: 10.26803/ijlter.19.10.16

Özkanal, Ü., Yüksel, İ., and Başaran-Uysal, B. Ç. (2020). The preservice teachers’ reflection-on-action during distance practicum: a critical view on EBA TV English courses. J. Qual. Res. Educ. 8, 1–18. doi: 10.14689/issn.2148-2624.8c.4s.12m

Paramita, P. P., Sharma, U., and Anderson, A. (2020). Effective teacher professional learning on classroom behaviour management: a review of literature. Aust. J. Teach. Educ. 45, 61–81. doi: 10.14221/ajte.2020v45n1.5

Robinson, C. C., and Hullinger, H. (2008). New benchmarks in higher education: student engagement in online learning. J. Educ. Bus. 84, 101–109. doi: 10.3200/JOEB.84.2.101-109

Rosilawati, S. (2013). Preservice teachers’ classroom management in secondary school: managing for success in teaching and learning. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 90, 670–676. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.07.139

Samu, B. (2020). “Teaching practice in pre-service language teacher education: challenges of the transition from face-to-face to online lessons” in Conference proceedings of the10th international conference: The future of education (Filodiritto: Editore) Available at: https://conference.pixel-online.net/FOE/files/foe/ed0010/FP/6251-TPD4730-FP-FOE10.pdf

Scull, J., Phillips, M., Sharma, U., and Garnier, K. (2020). Innovations in teacher education at the time of COVID19: an Australian perspective. J. Educ. Teach. 46, 497–506. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2020.1802701

Seljan, S., Banek, M., Špiranec, S., and Lasic-Lazic, J. (2006). CALL (computer-assisted language learning) and distance learning. Proceedings of the 29th International convention MIPRO. Rijeka: Hrvatska udruga za informacijsku i komunikacijsku tehnologiju. Available at: https://www.bib.irb.hr/251411/download/251411.CALLDL_Seljan.pdf

Sepulveda-Escobar, P., and Morrison, A. (2020). Online teaching placement during the COVID-19 pandemic in Chile: challenges and opportunities. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 43, 587–607. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2020.1820981

Taghreed, E. M., and Mohd, R. M. S. (2017). Complexities and tensions ESL Malaysian student teachers face during their field practice. English Teach. 46, 1–16.

White, M. (2017). A study of guided urban field experiences for preservice teachers. Penn GSE Perspect. Urban Educ. 14, 1–19.

Wolff, C. E., Jarodzka, H., and Boshuizen, H. P. A. (2020). Classroom management scripts: a theoretical model contrasting expert and novice teachers’ knowledge and awareness of classroom events. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 33, 131–148. doi: 10.1007/s10648-020-09542-0

Keywords: classroom management, virtual class, teacher education, COVID-19, pre-service teachers

Citation: Hojeij Z, Baroudi S and Meda L (2023) Preservice teachers’ experiences with classroom management in the virtual class: a case study approach. Front. Educ. 8:1135763. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1135763

Edited by:

Myint Swe Khine, Curtin University, AustraliaReviewed by:

Janika Leoste, Tallinn University, EstoniaOthman Abu Khurma, Emirates College for Advanced Education, United Arab Emirates

Copyright © 2023 Hojeij, Baroudi and Meda. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zeina Hojeij, WmVpbmEuSG9qZWlqQHp1LmFjLmFl

Zeina Hojeij

Zeina Hojeij Sandra Baroudi1

Sandra Baroudi1 Lawrence Meda

Lawrence Meda