- 1Bryn Mawr College, Bryn Mawr, PA, United States

- 2Haverford College, Haverford, PA, United States

STEM culture has consistently been characterized as exclusionary of a diversity of student identities, experiences, and voices. Through such exclusive and inequitable practices, STEM education dehumanizes. A growing body of scholarship documents ways in which student-faculty pedagogical partnership can support the creation of more equitable and inclusive practices. The research question we addressed is: How do faculty and student partners experience, perceive, and act on the potential of student-faculty pedagogical partnership to humanize STEM education? Combining aspects of a scoping review and reflexive thematic analysis, we analyzed 32 publications focused on pedagogical partnership in STEM in the arenas of learning, teaching, and assessment or curriculum design and pedagogic consultancy with student partners in the liminal role of pedagogical co-designer or consultant. Our review, informed by the experiences as well as the perspectives of the student co-authors, revealed five key findings about the aspects of pedagogical partnerships that contribute to humanizing STEM education. First, pedagogical partnerships give faculty access to students’ perspectives and humanity. Second, they support faculty in being, and being perceived as, more fully human. Third, they provide dedicated space and time to develop equitable approaches. Fourth, they support the enactment of equitable teaching. Fifth, they foster a sense of mattering, belonging, and agency in students. Drawing on these findings, we develop four recommendations for those interested in embracing partnership to humanize STEM education. The first is to create roles and support structures for facilitating genuine engagement across positions and perspectives. The second is to position underrepresented student partners to effect a culture shift. The third is to embrace non-STEM student partners’ contributions to humanizing STEM education. The fourth is to recognize this work as ongoing. Together, these findings and recommendations address calls to contribute to renewed and sustained attention to student experiences in relation to instructor values, dispositions, and positionalities. In addition, they reject harmful ideologies and practices that exclude a spectrum of identities, viewpoints, and values. Finally, they contribute to the creation of context-sensitive, inclusive, equitable, and empowering educational experiences for all students.

1. Introduction

An extensive body of research asserts that STEM fields constitute “an exclusionary culture” and that it is this culture, “not deficits in students themselves,” that denies students “access to identity development” critical for persistence in STEM (Reinholz et al., 2019, p. 44). Contributing to the maintenance of this culture is the lack of discussion of equity and inclusion in many STEM disciplines (Perez, 2016; Weiler and Williamson, 2020; Gerdon, 2022). Furthermore, according to one undergraduate, “the disconnect between our predominantly white faculty and their students, especially students of color” and the “lack of student voices in the development of inclusive classroom spaces” (Hernandez Brito, 2021, p. 1) reinforce the exclusionary culture Reinholz et al. (2019) describe, contributing to the dehumanization so many equity-denied students experience.

The definition of humanism offered by the editors of this collection has a number of components. It includes renewed and sustained attention to student experiences in relation to instructor values, dispositions, and positionalities. In addition, it calls for the rejection of harmful ideologies and practices that exclude a spectrum of identities, viewpoints, and values. Humanism in STEM education in particular, the editors suggest, focuses on creating context-sensitive, inclusive, equitable, and empowering educational experiences for all students. Without an emphasis on humanism in STEM education, students and professors might believe that the only “right” way to teach and learn STEM requires a disconnect between students and professors as well as between themselves and the course content.

We propose that one way to address the exclusionary culture, the lack of student voices in developing inclusive learning environments, and the overall dearth of humanism in STEM education is through the human and humanizing engagement that student-faculty pedagogical partnerships enact and support. As Bunnell et al. (2021) suggest, “learning from, partnering with, and highlighting the lived, subjective experiences of students in the classroom is a potentially powerful step towards inclusive education (de Bie et al., 2021; Cook-Sather, 2015, 2018),” and student-faculty pedagogical partnership “may be particularly well suited” to addressing challenges “related to inclusive education in STEM” (28). The transformative potential of the now-global practice of pedagogical partnership has been documented in a growing body of research on such partnership in STEM education. This article offers a review of a cross-section of that scholarship.

To frame our review we define pedagogical partnership, detail the form of student-faculty pedagogical partnerships upon which we focus, and describe the intersection of the scoping review method (Arksey and Lisa O’Malley, 2005) and reflexive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006, 2019) we used for our review. The majority of our discussion focuses on analyzing faculty and student reflections on processes and outcomes of partnership experiences in STEM education as represented in scholarship. Each of us brings a different perspective to this analysis. Alison, first author, is a full professor of education, a cis-gendered, white, female, and the director of Students as Learners and Teachers (SaLT). SaLT is a long-standing pedagogical partnership program at Bryn Mawr and Haverford Colleges in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States, which was founded on a commitment to developing culturally sustaining pedagogical practices (Cook-Sather, 2018b). Diana, second author, is a Bryn Mawr undergraduate who identifies as a first-generation, cis-gendered, female, Mexican and Salvadorian-American college student. She participated in SaLT with a STEM faculty partner for the first time in the Fall-2022 semester. Theo, third author, is a Haverford College undergraduate who identifies as a white, cis-gendered, male, college senior. He has worked in pedagogical partnership through SaLT with a range of STEM faculty since the Fall-2021 semester.

Both Diana and Theo had wanted to major in STEM fields but found the learning environments of their college STEM courses to be unwelcoming of a diversity of identities, viewpoints, and values, and they therefore pursued other majors. Diana, who was originally a chemistry major, decided to no longer pursue STEM because she realized she had many gaps in her K-12 education and not enough room to explore the human side of STEM. It was extremely difficult for her to learn the content—she had constantly to reference a dictionary for the words used while also trying to learn the language used to describe the content. Although her professors were extremely supportive, there were still many aspects of her education they could not fully comprehend because the experiences they had were so different from hers as a first-generation, low-income student. Although Theo’s identity might have fit traditional STEM culture more closely than Diana’s, he felt that the learning environment of his STEM college classrooms lacked qualities that make other classrooms supportive and empowering, and that inter-student support was either restricted to certain groups or was founded on competitive efforts. Diana’s and Theo’s analyses both of the scholarship and of their own lived experiences inform our discussion of how pedagogical partnership work can humanize STEM education.

Our review of 32 articles, chapters, and essays written by students and faculty who have worked in pedagogical partnership in STEM revealed five ways in which pedagogical partnership work can humanize STEM education. Student-faculty pedagogical partnerships:

1. Give faculty access to students’ perspectives and humanity;

2. Support faculty in being, and being perceived as, more fully human;

3. Provide dedicated space and time to develop equitable approaches;

4. Support the enactment of equitable teaching; and

5. Foster a sense of mattering, belonging, and agency in students.

There are overlaps across these themes and therefore echoes across as well as within sections of our discussion. In the final section of our review, we offer recommendations for how STEM disciplines might embrace pedagogical partnership to humanize STEM education.

2. Pedagogical partnerships

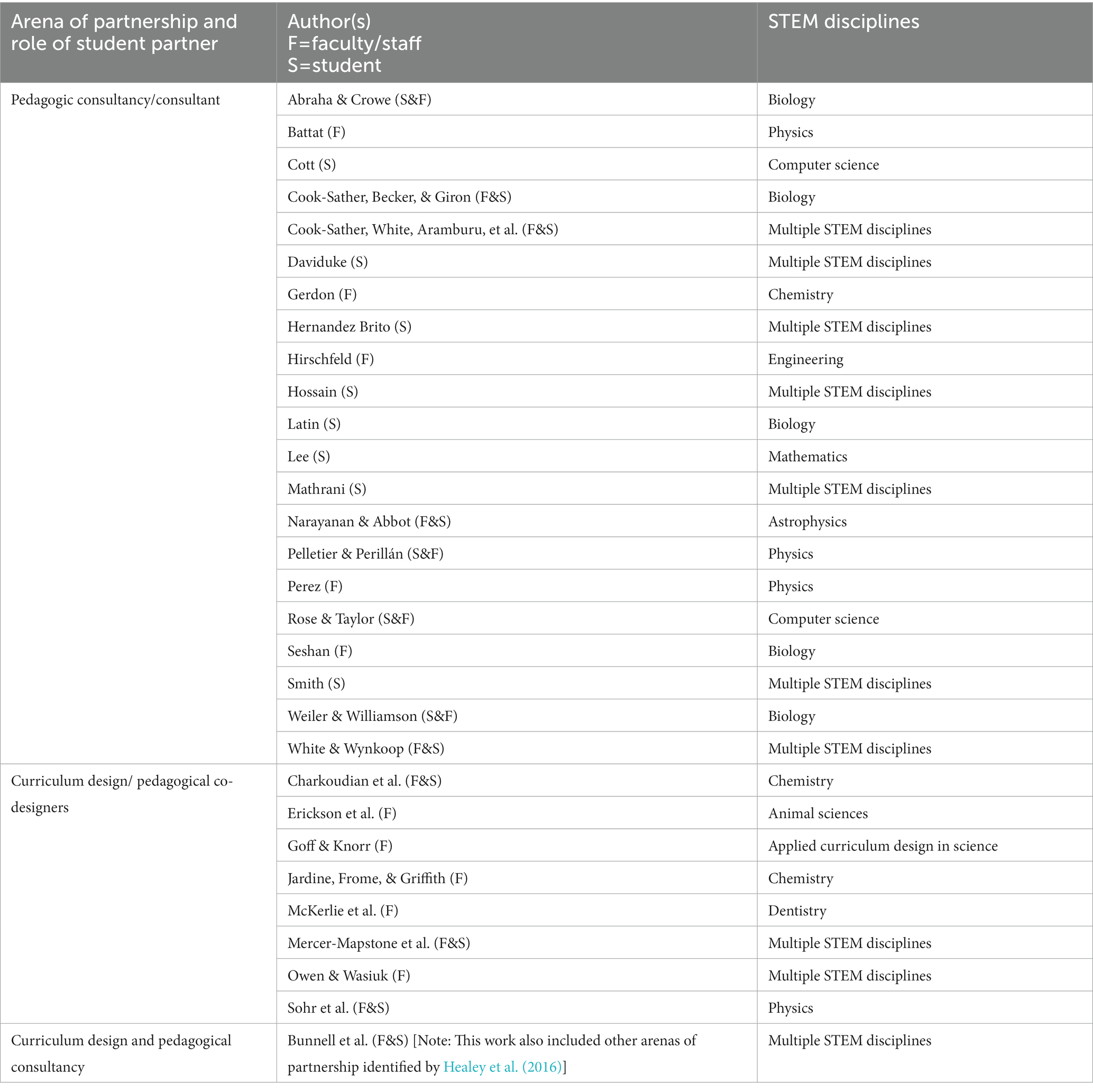

A widely cited definition of pedagogical partnership is: “a collaborative, reciprocal process” through which “all participants have the opportunity to contribute equally, although not necessarily in the same ways, to curricular or pedagogical conceptualization, decision making, implementation, investigation, or analysis” (Cook-Sather et al., 2014, p. 6–7). We focus on work that unfolds in two of the partnership arenas Healey et al. (2016) identify: learning, teaching, and assessment; and curriculum design and pedagogic consultancy. We also focus on two associated roles of student partners that Bovill et al. (2016) name: pedagogical co-designers (students sharing responsibility for designing learning, teaching, and assessment) and consultants (students sharing and discussing valuable perspectives on learning and teaching). Furthermore, to afford Diana and Theo opportunity to draw on their lived experiences as pedagogical partners, we narrow further to focus on partnership work in which students are not enrolled in the courses under consideration but rather assume liminal positions as co-designers and consultants (Cook-Sather, 2022). We represent these arenas and roles in Table 1 below.

Partnership, one student partner and author argues, “empowers students to contribute their voices to the development of more inclusive environments by providing real-time feedback to professors” (Hernandez Brito, 2021, p. 1). Educational developers confirm the potential of partnership to “work towards challenging traditional faculty-student boundaries, while simultaneously respecting the experiential expertise of students, disciplinary expertise of faculty, and curricular expertise of educational developers” (Goff and Knorr, 2018, p. 118). It does not do so automatically, however. It is important to provide support structures, including remuneration for student partners’ work and guidance in developing and implementing confidence, language, and strategies for engaging in such demanding emotional and intellectual roles (see Cook-Sather et al., 2019a for guidelines). In particular, regular meetings of student partners and partnership program coordinators constitute a form of professional development (Cook-Sather et al., 2021) that nurtures partnership skills and endeavors to avoid reproducing the harm many equity-denied students experience (de Bie et al., 2021). The importance of affirmation, deep listening, and striving to gain perspective are all integral to this partnership work (Smith, 2023) and need to be practiced (Cook-Sather et al., 2021).

3. Methods

This discussion combines aspects of a scoping review (Arksey and Lisa O’Malley, 2005) and reflexive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006, 2019). The research question that guided our exploration [stage 1 of Arksey and Lisa O’Malley’s, 2005 six-step process] was: How do faculty and student partners experience, perceive, and act on the potential of student-faculty pedagogical partnership to humanize STEM education? In keeping with the definition of humanizing we evoked in our introduction, our working definition of humanizing is recognizing, valuing, and bringing into dialogue a diversity of both inherited and constructed identities and lived experiences of faculty and students. The goal of this dialogue is the development of equitable and empowering pedagogical practices that attend to the intersection of student learning experiences and instructor values, dispositions, and positionalities.

To identify and select relevant publications [stages 2 and 3 of Arksey and Lisa O’Malley’s, 2005 process], Alison searched both “science” and “STEM,” as well as individual STEM fields (“biochemistry,” “biology,” “chemistry,” “computer science,” “neuroscience,” “physics,” “engineering,” “mathematics”) in journals dedicated to publishing about student-faculty pedagogical partnership work—International Journal for Students as Partners and Teaching and Learning Together in Higher Education—and in Mick Healey’s Bibliography of Students as Partners and Change Agents (Healey, 2022). She then widened the search through Google Scholar to all publications with these same terms and “pedagogical partnership,” which yielded several more publications. However, given that people do not use consistent terms for pedagogical partnership work, it is likely that we missed publications. Therefore, we do not claim to have conducted an exhaustive literature review.

All research articles, case studies, chapters, and reflective essays about pedagogical partnership in STEM were included if they focused on the arenas of learning, teaching, and assessment or curriculum design and pedagogic consultancy (Healey et al., 2016) and the student partner roles of pedagogical co-designer or consultant (Bovill et al., 2016) and if the students involved were not enrolled but rather positioned as collaborators, co-facilitators, and co-inquirers from more liminal positions (Cook-Sather, 2022). Thirty two publications met these criteria. These are represented in Table 2 according to arenas of partnership and student role in partnership. The table lists as well authors, whether they are students or faculty/staff, and STEM disciplines that were the focus of the partnership work.

For charting and summarizing the data [stages 4 and 5 of Arksey and Lisa O’Malley’s, 2005 process], we utilized a form of Braun and Clarke’s (2006, 2019) approach to reflexive thematic analysis. The familiarization phase involved reading each publication, selecting any quotations that addressed the humanizing experience of pedagogical partnership as guided by the definition above, and making initial observations and noting potential themes that emerged across publications. In the coding phase, Alison generated “succinct, shorthand descriptive or interpretive labels for pieces of information that may be of relevance to the research question(s)” (Byrne, 2022, p. 1399). These labels or categories shifted and expanded, developing subcategories, as Alison read through all the publications. In the writing phase, Alison produced an initial draft, drawing on as wide a range of voices from the publications as possible, and Diana and Theo added their analyses based on their own lived experiences as well as interpretations of the scholarship. We took this analysis process through several cycles, working to ensure that we represented the diversity of experiences and perspectives of published authors, the themes that cut across their experiences, and the ways in which Diana’s and Theo’s own experiences resonated with the themes.

4. Findings

As noted in the Introduction, faculty and student analyses suggest that pedagogical partnerships can humanize STEM education because they: give faculty access to students’ perspectives and humanity; support faculty in being, and being perceived as, more fully human; provide dedicated space and time to develop equitable approaches; support the enactment of equitable teaching; and foster a sense of mattering and belonging in students. We address each of these in turn, drawing extensively on the words of student and faculty partners in the publications we reviewed and on Diana’s and Theo’s experiences and perspectives.

4.1. Pedagogical partnerships give faculty access to students’ perspectives and humanity

The literature we reviewed revealed four ways in which pedagogical partnerships give faculty access to students’ perspectives and humanity: through student partners talking about their own learning experiences; sharing wider lived experiences and disciplinary understandings; offering their perceptions of the learning environment in their faculty partners’ classrooms; and drawing on their own experiences and insights to argue explicitly for equitable practice.

According to senior lecturer in engineering Hirschfeld (2022), student partners offer “insight into students’ experiences” that faculty are “not hearing from students enrolled in [their own] courses” (4). Hirschfeld (2022) writes that her student partner “would often talk about challenges she was experiencing in other classes” (4). Consistent with the “honesty and openness of these conversations” (Hirschfeld, 2022, p. 4), Theo reflects on how some of the most humanizing moments in large STEM courses happen when professors strive to see students as collaborators in analyzing and creating the learning environment—when they invite students to share their learning experiences and draw on those to inform practice.

A second way in which students’ humanity is revealed through partnership is in how the perspectives students share with faculty partners are informed by wider lived experiences and disciplinary understandings. Working with a faculty member in biology, student partner Latin (2022) explains that she could draw on her experiences as a psychology major and use her “perspective as a person of color at a predominately white institution (PWI)” (1) to inform her conversations with her faculty partner. Similarly, Natasha Daviduke (2018), a non-STEM student who worked with faculty in math, chemistry, and physics, reflects: “my perspective as a non-STEM student enhanced my observational powers, allowed me to draw suggestions from a broad array of pedagogical concepts, and enabled me to convey the viewpoint of a novice in the subject area” (152). Diana and Theo affirm that a student who has never taken a course offers insight that is more closely aligned with the experiences and perspectives of the enrolled students, especially if the students have had no prior experience or exposure to the subject matter of these courses. Theo further attests to the particular salience of non-STEM student perspectives when developing opportunities for active learning in STEM courses. Across several partnerships, when STEM professors sought to include more active learning practices, Theo could draw on his active learning experiences in humanities and social science classes to propose similar activities in the STEM courses.

A third way in which student humanity is revealed is through student partners offering their perceptions of the learning environment in their faculty partner’s course. One faculty partner describes what her student partner perceived: “My manner of delivery, the way I address students, the wording I use to describe things [are] all elements that do not often receive enough attention, but could contribute immensely, or detract severely, from the quality of my presentation” (faculty member quoted in Daviduke, 2018, p. 155). Summarizing the benefit of the student perception, this faculty member asserts: “Having a student partner gave me insights into teaching that are almost impossible to be gathered in any other way” (faculty member quoted in Daviduke, 2018, p. 155). Student partners often have similar perceptions to the students enrolled in the faculty partner’s course, but the student partners are perceiving from outside of the course’s expectations and demands. Because they are outside of the typical power dynamic of student and professor, they can share more freely these perceptions of the learning environment. Across multiple partnerships, Theo questioned and discussed with his faculty partners whether the goals of certain assessments matched up with how students approached them in practice. These conversations were premised on Theo’s being an observing student and his faculty partner being a receptive educator, both unburdened by the relationship of graded and grader.

A final way in which student partners share their perspectives and humanity is through drawing on their own experiences and insights to argue explicitly for equitable practice. Linking to student partner Angelina Latin’s point above, student partner Mathrani (2018) explains: “I shared [with my faculty partner] my personal interest in intentionally creating spaces in the classroom for students with equity-seeking identities and the possibilities for my partner to do that in their current and future classrooms” (2). This direct expression of commitment was met, Mathrani (2018) explains, by her partner’s interest “in talking more about creating an inclusive classroom” and led to “many conversations about how the classroom environment can actively work against stereotypes and assumptions that students are faced with” (2). Diana and Theo assert that one of the most powerful tools a student partner has is their ability to speak honestly and openly about their desires and goals for classrooms, specifically in terms of equity and inclusion. When in a partnership, they have the space to explain their ideas with someone who can construct that vision with them—their faculty partner.

When faculty partners gain insight into their student partners’ perspectives and perceive their student partners’ humanity, they recognize the importance of extending that understanding to enrolled students. Instructor of biology Lauren Crowe explains: “Understanding more about how social identities affect experience in the class has shifted how I seek to understand the student experience in all classes and how I view my own growth as an instructor” (Abraha and Crowe, 2022, p. 8). Senior lecturer in engineering Hirschfeld (2022) similarly notes: “By better understanding the student perspective and experience from my [student] partners, I became committed to transforming my pedagogy to better meet the needs of students and to disrupt inequitable academic power structures” specifically though looking for “ways to make students feel welcomed and valued in the classroom as their whole selves, fully deserving of flexibility, empathy, and understanding” (1, 5). These faculty are focusing explicitly not only on challenging inequitable structures but also on treating students as people.

Like the student partners quoted in the literature, Theo discusses with his faculty partners how the pedagogical choices that they make might impact students with certain social identities. He notes that there may be moments when office hours or TA sessions overlap with a meeting held by an affinity group or college therapy drop-in sessions, thereby making supportive resources less accessible for some students than others. At the most basic level, Diana suggests, it is vital that professors acknowledge that their students are people first, with their own needs and identities, in addition to being students, which is why recognizing the humanity in students can be helpful for making a more accessible and equitable classroom.

4.2. Pedagogical partnerships support faculty in being, and being perceived as, more fully human

Complementing the ways in which they offer faculty insights into student perspectives and humanity, pedagogical partnerships can support faculty in being, and being perceived as, more fully human. Centering humanism in STEM education requires that students be confronted with some of their own biases and misunderstandings about faculty. Through inviting articulations of faculty partners’ values, dispositions, and positionalities, pedagogical partnerships support faculty in exploring possibilities, expressing uncertainty, embracing vulnerability, and taking risks in their work as teachers. Our review of the scholarship revealed that student partners support faculty in these ways by: affirming faculty partners’ pedagogical approaches; being deeply attentive and engaged as faculty share their thoughts and feelings about teaching; offering constructive feedback on practice toward the goal of greater equity and inclusion; and sharing information that reveals shared identities, viewpoints, and values. When faculty experience these forms of support, they can lean into their vulnerability and gain confidence and courage (see Cook-Sather and Wilson, 2020).

Student partners nurture faculty members’ humanity through what student partner Mathrani (2018) describes as “affirmations of their practice, understanding their goals for teaching, and learning about what [is] important to them” (2). Diana offered her faculty partner, a chemistry professor, words of affirmation at every meeting. Vulnerability, Diana suggests, is crucial in developing a sense of security, relationship, and comfort in the pedagogical partnership because it gives students an insight to the human side of the professor. Theo argues that what Erickson et al. (2019) describe as “the development of meaningful relationships through the shared vulnerability of occupying the ambiguous liminal space” of pedagogical partnership (214) can be achieved through honest, genuine conversation about faculty members’ classrooms and pedagogy. In some STEM classrooms, professors may not feel able or know how to ask for feedback from their students. Theo suggests that many STEM courses emphasize memorization of material, which may create disillusioned ideals of mastery and expertise. For these reasons, professors might feel that asking for feedback from students could erode their position of authority in the classroom. In contrast, many faculty who participate in pedagogical partnerships describe how student partners support “the ‘bravery’ needed to question the traditional boundaries of what is discussed in an undergraduate physics class” (Perez, 2016, p. 2) or provide what a faculty member in biology describes as “a mirror” in which she can “unpack” her feelings each week (Seshan, 2022, p. 3). Whether through words of affirmation, asking questions, or sharing their own moments of vulnerability in the classroom, student partners and their faculty partners co-create a relationship founded on trust and support.

Being deeply attentive and engaged as faculty share their thoughts and feelings about teaching is a second way in which student partners both come to see faculty as more fully human and support faculty in being more fully human. Emphasizing the dialogic nature of the exchange between student and faculty partners, a student partner explains: “You’re there to provide your viewpoint, but also to get an actual conversation going” (Rose and Taylor, 2016). This means spending time in meetings on person-focused, not only work-focused, dialogue: “talking about our families, our goals, and other aspects of our lives” (Mathrani, 2018, p. 2). Such a human foundation makes both vulnerability and responsiveness more likely. Diana took this approach with her partnership and always opened her conversations with a check-in on family, goals, and wellness. Glimpsing the human side of her faculty partner, she realized that, just as students have struggles, fears, and societal pressures, faculty do as well. One instance Diana clearly remembers was when her faculty partner had a previous bad experience with end-of-semester feedback and was anxious about what students would say about her this semester. Diana suggested to her faculty partner that they should go over the semester feedback together and eat cookies to create a light-hearted environment, which, Diana believes, made her faculty partner feel reassured, seen, validated, and able to replace the negative experience with a much more humanizing one. As a result of the careful intentionality that both student and faculty partners bring to their partnerships, the discussions concerning the faculty partner’s pedagogy are rooted in mutual respect for one another’s perspectives, thus humanizing everyone and making meaningful change more possible. Student partner Mathrani (2018) explains that, because of the human relationship they built, “I knew I could be honest with my faculty partner…when there were practices I thought she could change, or situations I thought she could handle differently” (2).

The third way in which pedagogical partnerships support faculty in being, and being perceived as, more fully human is through the student partners offering constructive feedback on practice toward the goal of greater equity and inclusion. Offering constructive feedback on their faculty partners’ teaching is an exchange that is “surprisingly…vulnerable and unexpected,” explains student partner Maya Pelletier. “This type of sharing is unexpected, first because it’s uncommon in North American culture (especially coming from students to professors), and second because in having this vulnerability you discover things you did not realize you thought” (Pelletier in Pelletier and Perillán, 2022, p. 3). Many STEM faculty describe the movement from feeling vulnerable and anxious to feeling supported as people—and as teachers—when they receive feedback from student partners. For instance, while professor of physics José Perillán first experienced the observations and feedback as “anxiety producing,” he found the most benefit from partnership when, as he explains, “I relinquished control, embraced my vulnerability, and trusted the relationship with my partner”—human ways of engaging that made the partnership “a transformational experience” (4). As Theo notes, partnership work can help faculty begin to feel more comfortable shifting how they present their institutional power in the classroom. This shift lends itself to a more genuine learning community, such that these faculty members no longer need a student partner to engage in conversations around their pedagogy. When a professor asks for Theo’s perspective about something, he always suggests, after initially offering his thoughts, that they ask the enrolled students directly so long as it does not make them feel vulnerable and is not confusing. With this suggestion Theo aims to shift focus from dialogue between him and his faculty partner to a larger, open, ongoing conversation between the professor and their class, thereby further promoting and revealing the benefits of humanizing not only faculty but also the physical classroom space.

This humanizing can be facilitated in a fourth way: if student partners offer information that reveals shared identities, viewpoints, and values between them and their faculty partners. As assistant professor of physics Kirstin Perez explains: “Meron [my student partner], herself an underrepresented student who had been dissuaded from a STEM field by her experience in undergraduate classes, validated my own experiences with classroom environments that, while not explicitly unwelcoming, left us feeling isolated” (2). Perez continues: “With her, I could share the vulnerability of being a student who did not feel that her background and approach to study were shared by her peers, as well as annunciate the things we wish professors had spoken to us about” (2). Diana remembers feeling exactly like this in her general chemistry class and expressing this to her professor. Indeed, Diana recalls hearing all throughout her first year that General Chemistry was a weed-out class for students who wanted to pursue STEM and/or pre-med, and this added to the pressure of having to be the “perfect” student or the student who understood everything. This set of pressures left Diana feeling defeated and discouraged, exacerbated her sense that she did not fit in or was not smart enough to keep up with the material or with her peers, and ultimately contributed to her decision not to pursue a major in a STEM field.

When faculty experience the humanizing relationship that pedagogical partnership can be in any of the four ways outlined above, they gain confidence. As assistant professor of biology Anupama Seshan writes: “I have become more confident as an instructor as a direct result of this collaboration” (3). She explains that she was very surprised by this outcome because she had expected that her “ego would need a pick-me-up” after participating in pedagogical partnership; instead, her partner “was so affirming and enriching, and each week she supported me by listening to my concerns and my questions with warmth and with humor” (Seshan, 2022, p. 3). This humanized experience inspired Seshan to focus on humanizing her classroom. She explains that in their weekly meetings, she and her student partner “discussed language that I could use to encourage struggling first-year students to meet with me while decreasing their fear and sense of shame” (Seshan, 2022, p. 3). Diana concurs that the kind of language that is used in STEM is a huge factor in determining if a student is willing to engage with, understand, and learn the material being taught and to approach the professor. Similarly, Theo affirms the power of the humanizing relationship, specifically through the use of humor. He always likes to point out and explicitly appreciate moments when faculty partners use humor in the classroom as well as in their meetings with him. Humor can re-engage students and demonstrate a faculty member’s confidence as a facilitator, humanizing the faculty partner in both the STEM classroom and in the intimate, vulnerable student-faculty partnership meetings.

As the excerpts above make clear, much of the feedback student partners offer is affirming, although faculty often worry it will be negative. Assistant professor of biology Lauren Crowe explains: “knowing what was going right and was well received by students was just as, if not more, important than just knowing what I needed to change to create my ideal class climate” (Abraha and Crowe, 2022, p. 5). This balance of affirmation and constructive critique reflects the underlying human experience of always growing. Theo notes that such a dynamic diverges from the typical narrative of an entry-level STEM classroom, where students often perceive that there are single correct answers and they simply need to learn how to obtain those, instead leaving space for humanity that helps them develop STEM identities.

Affirmations of humanity can be rare in STEM courses. Assistant professor of physics Perez (2016) writes:

Whereas many humanities classes can encourage critique of which authors are included or excluded from a syllabus and why, or how societal factors influence the construction of a canon, the self-view of physics as a linear accumulation of objectively-necessary skills, and of success in physics as based solely on aptitude in these skills, can restrict discussion of social issues in the classroom (2).

Diana and Theo have found that humanities courses expose students to different experiences and perspectives, whereas in STEM courses, the fact that humans are engaged in the work seems to go unacknowledged, and students are required to engage in the content no matter who they are and what perspectives they bring. Partnership contrasts these realities, as professor of chemistry Helen White explains: “Our conversations created a space of care, kindness, and patience—all qualities necessary to do [the equity] work that at times can seem overwhelming and insurmountable” (White and Wynkoop, 2019, p. 2). Communication lies at the heart of student-faculty partnership; this is influenced by both partners’ efforts to support, listen, affirm, and make space for each other, so that each partner’s humanity is valued and emphasized in the work.

4.3. Pedagogical partnerships provide dedicated space and time to develop equitable approaches

Our review affirmed that pedagogical partnerships are structures that otherwise typically do not exist for dialogue between faculty and students in which they can articulate commitments to enhancing equitable learning opportunities and produce plans for how to pursue those goals. These structures both support pedagogical approaches and build courage and confidence to implement them (Cook-Sather and Wilson, 2020). A “structured scaffolding that includes immediate and ongoing feedback from a student who is not registered for your course,” explains professor of physics José Perillán (Pelletier and Perillán, 2022, p. 1), ensures that faculty “dedicate time and energy to discussing [underlying areas for growth and systemic change] collaboratively” with students, according to student partner Kate Weiler (Weiler and Williamson, 2020, p. 5). Positioning the student partner outside of traditional power dynamics creates what assistant professor of physics Kerstin Perez (2016) describes as a “space necessary to address with students how [discussing] issues of equity and inclusion” aids in creating a more equitable environment inside and outside the classroom (4). A weekly meeting for a professor-student partnership can, Theo notes, be a moment of respite for the professor, rare in a typical academic environment, and a time for professors not to have to think about their long-term professional goals, the ongoing politics within their department, and the next lesson plan. Instead, they can have space to reflect on how the current moments in the classroom are impacting the students and double check that their intentions are coming to fruition in the classroom space.

The space of partnership can support faculty in thinking about equitable practices within individual classrooms and labs and also in developing a critical perspective on the larger systemic inequities embedded in higher-education institutions. Considering the classroom level, student partner Cott (2021) explains that she and her faculty partner posed the following question for exploration: “‘How can we invite voices that are frequently silenced (think: gender, race, etc.) in computer science and what kind of scaffolding can we use to support each voice in the classroom?’” (148). Student partner Sasha Mathrani (2018) explains that she disagreed with an approach her faculty partner planned to take: to “start the class with a very difficult assignment to show the students they had a lot to learn” but not “tell the students the assignment was intentionally difficult” (4). After explaining to him that she worried this approach would “disproportionately hurt students from marginalized backgrounds” who are “questioning their place in a natural science classroom,” her faculty partner “immediately changed his focus and began to think about his practice differently” (Mathrani, 2018, p. 4–5). Both Theo and Diana affirm the importance of this shift, with Diana noting that when her faculty partner goes into detail explaining ‘why,’ it helps the students feel a lot more connected and seen/heard. Additionally, Theo notes that when faculty partners engage in pedagogical transparency, students are better able to communicate any confusion around the activities. His faculty partners mention that student questions are clearer when the expectations of assessments are transparent.

“In a partnership framework,” Bunnell et al. (2021) explain, “we create space for uncovering bias and misunderstandings” (31). If, as in Theo’s experience with many professors, those professors rely on their perceptions of student feelings and thoughts, such biases and misunderstandings can persist. The same can happen as students make biased assumptions about faculty. In contrast, pedagogical partnership pulls back the curtain on what goes into a college classroom (intentions, expectations, pedagogical choices, etc.) with the explicit goal of both affirming effective approaches and improving professor and student experiences. Attempts to open space in decision making in curriculum development, for instance, such as a project focused on codesigning a set of curricular materials for topics in quantum mechanics that students often struggle with, involve “extended, complex, and at times subtle, negotiation and contestation of participation” (Sohr et al., 2020, 020157-18). These conversations—with explicit inclusion of student perspectives and thoughts—are not easy to have on a large scale but can offer significant benefits when more of those involved in the conversation, faculty and students alike, have experience navigating these conversations from partnerships.

Within the structured spaces that partnership creates, faculty partners can articulate and pursue their pedagogical commitments to equity. Assistant professor of physics Kerstin Perez (2016) explains:

While I was worried about the mechanics of running a course – Is my writing on the board legible? Am I talking too fast? Do I stop for questions enough? – [my student partner] encouraged me to think about and, crucially, say aloud my values as an instructor. She asked me to articulate my ideal class environment: one where all students are unafraid to learn from each other and their mistakes, and to support each other as they struggle through difficult material (1).

Diana took this same approach in her partnership, and it contributed significantly to laying the foundation for a humanizing space focused on deepening equitable practice. Diana’s faculty partner and her students wrote classroom expectations for the first class, one of which was ‘holding each other accountable and supporting each other with grace.’ What that meant to this faculty member and the enrolled students was to encourage each other in the classroom, and when someone was wrong, to graciously and kindly correct them.

Developing clarity about equitable pedagogical approaches and practicing transparency in enacting those are key functions of the partnership work. Associate professor of chemistry Helen White explains that she and her student partner, Paul, used their meetings as a “reflective and conversational space where we could discuss our despair and frustrations with existing structures” and also use some of their time “to take care of ourselves and to manage the emotional demands of this work.” Over time, White continues, “a shared understanding and renewed commitment to addressing the existing inequalities … emerged from the connection between our faculty and student perspectives” (White and Wynkoop, 2019, p. 1). Theo explains that in one of his partnerships, he and his faculty partner, a chemistry professor new to the department, frequently filled in each other’s gaps in knowledge about the experiences of the students in the department to create a collaborative conceptualization of the classroom with respect to two of its primary influencers: students’ previous experiences and departmental expectations placed upon the professor. Without having such conversation, Theo suggests, he would not have been aware of the challenges that his faculty partner experiences in preparing a class that will be accessible to students. Similarly, if he had not shared his experience and perceptions of the chemistry classroom, his faculty partner would not have been able to use that knowledge to shape her pedagogy. These understandings that develop over time are a result of the trust built through partnership. In addition to information helpful to everyone in the classroom, what this trust creates is low-stakes environment solely for the purpose of growing as educators and learners.

As Theo notes, a classroom’s purpose is to teach, allow people to learn, and present new information to everyone. If a classroom only serves those who are most comfortable in that space—people who have been in similar spaces because they went to well-resourced schools or have other privileges—then that classroom is not serving its purpose. For example, if there is a genius professor who can only get 5% of the class to understand and learn the concepts taught, while the rest of the class does not feel supported or feels as though they are in a hostile learning environment, then there is an inequity at play that is harming students and preventing the classroom from being an accessible space. Using the dedicated space and time allotted by pedagogical partnership to develop equitable approaches to classroom practice entails, as associate professor of chemistry and physics Gerdon (2022) notes, “intentionally highlight[ing] important issues of inclusivity or exclusion throughout the semester and … establish [ing] a classroom community where students could belong and learn in different ways” (1). It entails working, as student partner Daviduke (2018) argues, “to build space into the course for deeper discussion” as well as to “place concepts and examples into a relevant context” and “provide a clear structure for academic success” (153).

On the systemic level, faculty and student partners can use the space of partnership to recognize the larger structures that perpetuate inequity—what Kate Weiler, a student who partnered with a faculty member in biology, describes as “problematic systems and structures [that] permeate the walls and affect students and their families” (in Weiler and Williamson, 2020, p. 5). Because of the “trusting relationship” (Williamson in Weiler and Williamson, 2020, p. 5) faculty can develop with their student partners, they can address institutional barriers to inclusive STEM practices (Hernandez Brito, 2021) and, thinking about the trajectories through STEM majors students must follow, “reimagine how to teach an introductory STEM class with sensitivity to students’ learning needs and consideration for the type of thinking they would be asked to do in higher-level courses” (Daviduke, 2018, p. 155). Theo and Diana appreciate this conscious consideration because so often students are taught individual bits of information but not taught why they need to know particular things, when or how those things fit into subsequent courses, and how such information fits into the discipline as a whole. Without a professor’s proactive and expert contextualization, student learning of decontextualized information is just a menial task. For example, in a partnership Theo had with a faculty partner teaching a required chemistry class, the faculty partner’s goal was for students to focus on developing their problem-solving skills relating to chemical synthesis. However, before the faculty professor stated this goal explicitly, many students were under the impression that it was a class focused on rote memorization of chemical mechanisms, as they did not yet understand how the content fit into their journey through undergraduate chemistry. The work between a professor and a student partner can help illuminate the connection between those goals and the content being taught as well as help faculty move toward enacting greater transparency and uncovering the hidden curriculum—practices especially important, as Winkelmes (2023) notes, for minoritized students.

4.4. Pedagogical partnerships support the enactment of equitable teaching

By fostering relationships that are humanizing for both student and faculty partners and providing structured space to develop equitable approaches, pedagogical partnerships support the enactment of equitable practices. Scholarship documents individual changes made by faculty members in the creation of classroom environments that become “trauma-informed learning spaces” (Weiler and Williamson, 2020, p. 6). In such spaces faculty focus on “seeing the humanity and complexity of students” and also “revealing our humanity to our students to show them that we are on their side, that we have their backs, that we see them and validate their struggles and that they matter” (Aren, 2022, p. 42). When students and faculty partners are guided by humanity, they focus, as one faculty and student pair put it, on “areas that we knew would be sticking points” and being “transparent with the students” (Narayanan and Abbot, 2020, p. 191). Such practices are more equitable because they recognize that students enter the learning space with different kinds and degrees of preparation and are navigating different challenges in their lives. This enactment of equitable practices includes individual changes in or transformations of faculty members’ creation of: classroom environments; teaching practices; and curriculum.

Addressing the classroom environment, associate professor of chemistry and physics Gerdon (2022) writes: “I worked hard, with [my student partner’s] help, to make intentional decisions that would demonstrate a desire to build community with my students” (1). Assistant professor of biology Adam Williamson also asserts that “student-faculty partnerships are an important strategy to hold faculty accountable to build and nourish the learning communities we so often promise” (Williamson in Weiler and Williamson, 2020, p. 6). Theo has observed some STEM professors refer to their class as a “learning community” to make this kind of intentionality clearer to students. Using such language helps because not all students have the idea that they are learning, in community, with the rest of their classmates, because of the competitive nature of many STEM majors. When professors are intentional about building community in the STEM classroom, it provides a more accessible space for learners across a wider range of identities. Having such dialogue in partnership supports faculty in extending similar conversations to enrolled students.

Also addressing how she shifted her classroom environment toward a more human, inclusive, and equitable one, assistant professor physics Perez (2016) spent a portion of her class talking with her students about a sexual harassment case in a physics department at another institution, and she was “astonished by the positive response from students” (3). These responses included acknowledgment of how rare such discussions are in most STEM classes, expressions of appreciation from students for having a woman as a science professor for the first time, courage to speak with the faculty member about a difficult life transition that was interfering with their academic life, and willingness to speak privately with this professor about doubts of being “smart enough” for physics. Seeing the difference in classroom environment that such a conversation made, Perez (2016) and her student partner “brainstormed ways to communicate to all students that they are welcome and supported,” including “small tweaks to the vocabulary and infrastructure of a course” that could affect the classroom culture” (4).

Focusing on the enactment of equitable practices in the pedagogical realm, faculty partners such as assistant professor of physics José Perillán write about “pedagogical tweaks and interventions … around … various approaches to introducing and discussing concepts and ideas” (Pelletier and Perillán, 2022, p. 7). Assistant professor of physics Battat (2012) describes his student partner comments on the benefit of putting students into groups to wrestle with questions: “This gives students an opportunity to evaluate the material that they have covered so far and ask questions if they do not understand a concept” (3). Battat (2012) asserts as well that this practice “changes the dynamics of the class because students get to know each other better and figure out a problem in a team” (3). Theo notes that the efficacy of this approach lies in its contrast to situations in which the only interaction that students have with one another is in graded group projects, in which they only get to know each other in high-stakes situations. Low-stakes opportunities for students to get to know each other are essential to developing an accessible learning community. Battat (2012) explains how his work with his student consultant, Roselyn, affirmed this inclusive practice for him: “I entered the semester committed to the inclusion of interactive group work in the classroom. However, I was less sure/confident about how to implement this successfully. Roselyn’s observations helped reinforce for me the beneficial impact of the group work on the learning experience” (3).

Bunnell et al. (2021) report that facilitating a Being Human in STEM (HSTEM) course “informed faculty and staff members’ pedagogical approaches more broadly” (39). For instance, a White female tenure-track professor and HSTEM course co-facilitator explained:

As a consequence of HSTEM, I made a deliberate decision to share with students stories about my own failures and moments of doubt. I am a junior faculty member, and I am the only female faculty member in my department, in a field where women are underrepresented. Participating in the HSTEM initiative has increased my awareness not only of the importance of inclusivity in my classroom, but also of the importance of building a community for myself (Bunnell et al., 2021, p. 39).

Similarly, a chemistry instructor who worked with several student partners to redesign an introductory chemistry laboratory course asserted that the lessons they learned “were invaluable and not only enhanced this specific course, but their teaching overall” (Jardine et al., 2023).

Diana muses that faculty sometimes feel that they cannot share too much about their personal lives because it would make them seem less authoritative. However, students appreciate when faculty are vulnerable with their students. Diana remembers being in a general chemistry class and feeling inadequate until her professor, also a woman of color, opened up and told Diana how she had failed a chemistry class as an undergraduate but still became a chemist. This professor sharing her story encouraged Diana to work harder, and made her feel less inadequate about her abilities in the lab. Theo likewise asserts the power of professors saying that they do not know or do not remember the answer to a problem and that they will look up the answer and get back to the student once they have researched it. Such modeling provides a wonderful way for professors to demonstrate their humanity and enact a more realistic and equitable expectation for learning in the classroom.

Enacting equitable approaches requires coming to see how inequitable past approaches may have been. Assistant professor of astrophysics Desika Narayanan explains: “I grew up in large university systems (and continue to teach in one) where the style was often combative between students and professors” (Narayanan and Abbot, 2020, p. 193). Such an approach can be easily reproduced. However, as Narayanan continues: “This partnership taught me how to approach lectures with particular care toward increasing clarity and energy, which has the effect of deepening the in-class relationship between me and the students” (Narayanan and Abbot, 2020, p. 193). A professor can never know what kind of expectations or perceptions STEM students hold when they enter the classroom. For this reason, some students may interpret a professor’s actions, which may have good intentions, as a kind of trap or not have the trust in professors to believe the transparency that they may talk about. Partnership can support the time, effort, and constant reflection necessary to develop trust and be transparent, as well as support faculty in getting to know students and demonstrate investment in their learning, all typically absent in environments where there is a combative student-professor dynamic.

Linking pedagogical practice with formative and summative assessment, several student and faculty partners reflect on the ways in which their partnership work humanized their approaches and made them more equitable. For instance, focusing on formative assessment and feedback, in a biology course student partner Eve Abraha explains: “Many students felt that this was one of the first courses in which they learned a lot and also felt supported by their professor” because the professor “consistently followed up with students who she saw were not performing well,” conveying a “sense of care” that made students “want to stay in the course and work it through rather than dropping it” (Abraha and Crowe, 2022, p. 5). Abraha argues that this kind of communication with students about their progress and wellbeing was important because it “showed the subset of students who were struggling (especially those who were Black and/or Latinx) that they were capable and there was someone who believed in them rather than falling prey to misguided negative beliefs about their own intellectual capacity” (Abraha and Crowe, 2022, p. 5).

While fewer of the publications we reviewed addressed curricular revision, Mercer-Mapstone et al. (2021) report that faculty working in partnership with students on an academic development project aiming to enhance the inclusivity of science curricula demonstrated an increased adoption of inclusive teaching practices. Similarly, one of the action projects emerging from the Being Human in STEM (HSTEM) course at Amherst College is a student-authored handbook of suggested inclusive curricular practices1, which is shared annually with all new STEM faculty and “guides the focus for STEM faculty and staff as they integrate and refine inclusive practices in their teaching” (Bunnell et al., 2021, p. 31–32). As another example, at the Glasgow Dental School in Scotland, a co-creation approach “is now a permanently embedded element of the curriculum and we look forward to continued success with this model of co-creating teaching materials for the BDS [Bachelor of Dental Surgery] course. The success of the SSM [special study module] is evidence that given the right circumstances, coproduction partnerships have a place in professional degree programmes” (McKerlie et al., 2018, p. 127). Owen and Wasiuk (2020) developed a partnership approach to course design that they argue “can be easily adapted for different projects and contexts and could be more widely adopted across the University.” Finally, Seshan (2022) asserts: “I have made lasting changes to the way that I design my courses because of this program, and I have found that the student-perspective is more readily in my consciousness” (4).

In order to enact equitable practices in STEM, faculty need to feel confident and empowered. These examples in this section illustrate what assistant professor of chemistry Lou Charkoudian explains after completing a semester-long revision process of organic chemistry with three students. She “felt empowered teaching a course with my newfound clarity of purpose” and “sensed a deeper connection with my students born from the bond with my student consultants” (Charkoudian et al., 2015, 7). As a result of this experience, Charkoudian “consciously created an environment of pedagogical transparency” in which “students could come to me with continual feedback and suggestions to make the course stronger. I felt like I was a part of a team,” she explains, “and that I was working along-side my students to achieve the course objectives” (Charkoudian et al., 2015, p. 8–9). Another faculty member noted how partnership “definitely boosted my confidence as a first-time teacher of the organic chemistry laboratory,” and when she taught the course again, she felt “very confident about my ability to lead the class and it manifested into an extremely positive learning environment” (quoted in Daviduke, 2018, p. 153). And senior lecturer in engineering Hirschfeld (2022) asserts that her weekly meetings with her student partner, specifically her partner’s feedback and encouragement, gave her “the confidence to make changes during the semester and experiment with different activities and topics of discussion during class sessions” (4). In a similar vein, Theo enthusiastically encouraged his faculty partner in chemistry to include a portion at the start of every class that specifically developed students’ chemistry vocabulary. His faculty partner had thought of this as a solution to students feeling embarrassed or avoiding calling compounds by their official names and thus bolster their confidence and ability to identify where in a given problem they were confused. Through her partnership, this faculty member developed the confidence to structure in this equitable activity.

4.5. Pedagogical partnerships foster a sense of mattering, belonging, and agency in students

The potential of partnerships to foster a sense of mattering, belonging, and agency across students with a diversity of identities (Perez, 2016; Colón García, 2017; Cook-Sather et al., 2021; Weston et al., 2021; Cook-Sather et al., in press) is particularly important for students in STEM, given the unwelcoming culture of STEM described by Reinholz et al. (2019) as well as student partners, both Diana and Theo and the student authors and co-authors of the literature we reviewed. These experiences of mattering, belonging, and agency are described by both student partners and enrolled students. One student partner explains how partnership “helped me reconnect with being a student who is also human; I am better able to recognize my needs, notice the experiences of others, and find ways to approach professors about making the classroom a welcoming space for everyone” (Pelletier and Perillán, 2022, p. 8). And a study of the Being Human in STEM (HSTEM) Initiative found that students in HSTEM lab sections reported “holding a minority status in class positively contributed to their learning in STEM” (Bunnell et al., 2021, p. 45).

Mattering focuses on students feeling that they have value regardless of whether they fit in any given context (Weston et al., 2021; Cook-Sather et al., 2021). Regarding the experience of mattering, student partner Maya Pelletier asserts that the partnership program in which she participated “made me more aware of both my own position and experience in a learning setting as well as that of others” (Pelletier and Perillán, 2022, p. 8). Prior to her partnership work, Pelletier had felt that she “had to shut down the parts of my brain that were reacting with anger or fear or shame to certain pedagogies because my purpose was not to have emotion; I had to absorb knowledge” (Pelletier and Perillán, 2022, p. 8). What Pelletier describes is a profoundly dehumanizing experience. In her own vivid words:

In limiting my human response to the classroom, I was becoming an automaton in my learning, I was being unfair to myself as a person, and I was missing important cues for inclusion in the classroom. When you train to become a machine, it is difficult to respond to others or yourself as human—something that destroys community and makes it difficult to realize unfair situations when they arise (Pelletier and Perillán, 2022, 8).

The experience of working in pedagogical partnership made Pelletier feel that she, and all learners, matter as humans.

Belonging is typically framed as having two essential parts: fit and value. “Fit” relates to a student’s sense that they share identities or other salient characteristics with others in the institution (Asher Stephen and Weeks, 2014). “Value” describes the significance of “students’ perception of feeling valued and respected by other students” and, to a lesser extent, staff at the institution (van Gijn-Grosvenor and Huisman, 2020, p. 377). In relation to students’ increased sense of belonging, Marie and McGowan (2017) report that students who participated in the ChangeMakers scheme at University College London reported “an enhanced sense of community and belonging, a sense of empowerment, improved teamwork and communication skills, and a better understanding of how the university works” (p. 2). Mercer-Mapstone et al. (2021) also report that students and faculty working together on an academic development project aiming to enhance the inclusivity of science curricula experienced changes in perception, like an increase in sense of belonging for both faculty and students and fairness in decision-making for students. Likewise, Jardine et al. (2023) report that participation in a course redesign project increased student partners’ sense of belonging. And finally, Bunnell et al. (2021) explain that: “The experience of co-creating the Being Human in STEM Initiative increased the pioneers’ stakes in the Amherst community, providing a thread of continuing connection, belonging, and personal investment” (37). They specify that, in contrast to students in a non-HSTEM lab sections of a large, introductory science course, who reported that being female and people of color made learning harder and more stressful, students in HSTEM lab sections reported that these dimensions of their identity positively contributed to their learning in STEM. For instance, one student wrote, “The more diverse we are, the more inclusive and comfortable it is.” Another student reported, “I feel proud to be a woman in STEM and love to see how many other girls are doing so well in my lab section” (Bunnell et al., 2021, p. 45).

Student partners also develop a sense of agency and capacity through their work. Student partner Anna Bitners, who majored in chemistry, asserted that the process of redesigning an organic chemistry course with a faculty member and two other students “gave me a sense of agency on the level of the course and the Chemistry Department as a whole” (Charkoudian et al., 2015, p. 6). Student partner Sabid Hossain (2021), who majored in physics, describes himself as “a brown man contained in predominantly white institutions for the past 8 years” who “grew up in a low-income household” and experienced his identity as “a barrier” in academic places such as the classroom. In reflecting on his work to launch the More Inclusive Learning Environment (MILE) program at Davidson College, focused on making STEM more welcoming to a diversity of students, Hossain warns students about the resistance, disapproval, skepticism, and other challenges they might experience, but encourages them to “take risks and be willing to face backlash….Do not waver. It is important to understand why you are doing the work that you are doing” (7). He urges students to “reaffirm your values and remember that improving the pedagogical practices within classrooms helps every party involved and helps institutions take a step closer to a more equitable and inclusive environment” (Hossain, 2021, 8). As Theo notes in relation to the set of points, the nature of student-professor partnerships is that students will move on to other institutions, departments, or life post-grad, so the environment around student partnerships can be positively influenced by professors who are willing and desire to engage in the work. By sharing their intentional goals with respect to pedagogy with other faculty members as well as students, professors can make a greater investment in the college or department as a learning community that is capable of change and adaptation. This is very important for encouraging institutional memory about the value of student partnership.

Consistent with these points about persistence, student partner Lee (2021) reflects that, while initially he saw his role “as an assistant rather than a partner or consultant,” the partnership as it unfolded afforded him “an opportunity to engage with a faculty member as an expert in my own right and demystify the seemingly distant relationships that students hold with professors at the college level” (1). This shift not only informed Lee’s own sense of agency; it also allowed him “to confidently engage in discourse with my faculty to create an inclusive learning environment as well as help voice the opinions of students in class” (Lee, 2021, p. 3). Lee (2021) asserts that, “Having experienced the pedagogical partnership program at Amherst, I feel more inclined to engage in conversations with my professors about my learning needs. The partnership allowed me to recognize what pedagogical tools I need to best learn in class, and how to approach my professors with confidence” (3).

There are additional ways in which experiences of mattering, belonging, and agency carry into engagement beyond partnership. Biology major and student partner Sasha Mathrani argues that through her pedagogical partnerships, she “developed a sense of confidence, passion, and desire to effect change, and all of that growth transferred over” into other advocacy work she did for underrepresented students in STEM (Mathrani and Cook-Sather, 2020, p. 163) and in her confidence to speak up in a workshop designed for faculty and postdoctoral students while she was an undergraduate (Mathrani, 2018). This commitment and capacity to advocate for equity and inclusion in STEM beyond partnerships characterizes many student partners’ experiences. After participating in the co-creation of a course at McMaster University, for instance, some students “continued to partner with educational developers on teaching and learning initiatives well beyond the completion of the Applied Curriculum Design in Science course and even beyond their undergraduate studies at McMaster” (Goff and Knorr, 2018, p. 117). Furthermore, upon graduation, “curriculum design students continued to work on encouraging students to become partners in teaching and learning initiatives by conceptualizing and developing ideas and programs at McMaster and at other universities” (Goff and Knorr, 2018, p. 117).

Finally, students who have participated in pedagogical partnership carry their commitments and capacities into their own practice as teachers in STEM classrooms. Eve Abraha, a student of biology and student partner at Tufts University, writes:

Ensuring that assessments tests students’ knowledge accurately and equitably was one of the first things I was able to practice with [my faculty partner]; the next step was assessing students’ feelings towards their learning—did they feel that learning the material was presented in many ways, did they get different ways of assessing their knowledge, and did they have access to support when needed? Overall, doing a survey in the middle of the semester allowed us to check what was working and what needed revision. I have taken all of these skills and new language around equitable evidence-based pedagogy that I have learned from [my faculty partner] with me as I teach underserved high school students in physics! (Abraha and Crowe, 2022, p. 7).

5. Discussion and recommendations

The quotes from publications by student, staff, and faculty partners such as those included above affirm that such partnership is one effective way to develop “the brave space necessary to have these conversations” about equity in STEM validate for participating faculty how personal experiences influence teaching and support the changes faculty attempt to make (Perez, 2016, p. 5). Looking across these themes surfaced in the reflections of faculty, staff, and students, we recommend:

• Creating roles and support structures for facilitating genuine engagement across positions and perspectives;

• Positioning underrepresented student partners to effect a culture shift;

• Embracing non-STEM student partners’ contributions to humanizing STEM education; and

• Recognizing this work as ongoing.

5.1. Creating roles and support structures for facilitating genuine engagement across positions and perspectives

While partnership does not ensure that STEM education is humanized, it provides structure and support that helps faculty keep a focus on the humanizing process—making classrooms welcoming and affirming student identities and capacities. Associate professor of chemistry and physics Aren (2022) explains:

My confidence in addressing sensitive topics has certainly grown, and I see how that confidence is carrying over to my other courses. Maintaining confidence and effectiveness as a teacher will require continued practice and effort, but through this one experience I’ve seen the benefits of that effort and how working with a partner makes the effort much less of a challenge. (3–4)

Similarly, professor of physics José Perillán writes: “I … have become sensitized to the student experience in a uniquely transformative and irreversible way” (Pelletier and Perillán, 2022, p. 8). Senior lecturer in engineering Hirschfeld (2022) asserts: “I gained a sense of community and connection that gave new meaning and purpose to my teaching, which I had been so used to doing in isolation” (4). And finally, assistant professor of biology Adam Williamson reflects on how his partnership with Kate Weiler “built on trust and open, honest communication,” will help him” to continue to grow as the teacher and mentor” that he wants to be (Weiler and Williamson, 2020, p. 6, 2).

Creating roles and support structures for facilitating genuine engagement across positions and perspective allows faculty and students to engage in this work that might not otherwise be supported (Pelletier and Perillán, 2022, p. 8). The role of student partner is still relatively new, but an increasing number of institutions are developing partnership programs, and there are guidelines available for how to do so and specifically how to design the student partner role (see Cook-Sather et al., 2019a). Creating support structures for the new role of student partner also includes, as we noted in our initial discussion of partnership work above, both appropriate forms of compensation for student labor and regular forums, such as weekly meetings, to support student partners in developing the confidence, capacity, and language to engage in this demanding work (Cook-Sather et al., 2021).

Our third theme above—provide dedicated space and time to develop equitable approaches—can support pursuit of the other themes we list. As Jardine and her colleagues (2023) argue, considerations regarding structuring successful partnership work in STEM include “recruiting a diverse team of students, allowing for both individual and collaborative work, providing flexibility, and setting up organized communication systems.” They also note challenges, including “balancing breadth versus depth, attending to differences in expertise and motivation, and balancing freedom and structure” (167).

5.2. Positioning underrepresented student partners to effect a culture shift

Positioning underrepresented students as partners, in particular, allows students to mobilize their own cultural identities and contribute to a culture shift (Cook-Sather et al., 2019b; Brown et al., 2020; Cook-Sather et al., 2021). Several student partners make this point, including Latin (2022), who asserts that she could draw on her perspective “as a person of color at a predominately white institution (PWI) to inform my conversations with my faculty partner” (1), and Sasha Mathrani (2018), who shared her “personal interest in intentionally creating spaces in the classroom for students with equity-seeking identities” (2). And faculty partners, such as assistant professor of physics Perez (2016), affirm that when students take on this work, they affirm faculty members’ own identities, experiences, and approaches.

Especially important to consider in positioning underrepresented student partners to effect a culture shift is how to create equitable partnership structures that do not reproduce the inequities, specifically the violences and harms, of higher education (de Bie et al., 2021). Violences are done by the institutional structures, cultures, and practices; harms are what result from these violences and focus specifically on what students experience. The former can include the epistemic violence many equity-denied students experience in the form of having their knowledge and capacity as knowers discounted, their diverse epistemologies unrecognized, and their epistemic labor dismissed or exploited, which can lead to the epistemic harms of doubting or devaluing what they or their cultures know and value. A second form of violence equity-denied students can experience is affective; subject to multiple forms of discrimination and oppression (e.g., psycho-emotional disablism, microaggressions/abuse), equity-denied students are expected to conform to dominant norms (such as heteronormativity). The emotional harms of such violence include isolation, nonbelonging, self-doubt, uncertainty, racial-battle and other forms of fatigue and the exhaustion from carrying burdens of emotional labor that those who do not experience these violences and harms do not have to carry. Finally, both informed by and informing epistemic and affective forms of violence, ontological violences cause students from equity-denied groups to be dehumanized because what they know and how they feel are dismissed. When students experience their very beings as negated or inhibited, blocking them from being who they are, they can internalize harms that take the form of negative impacts on their sense of self and personhood, denying or limiting who they are and can be leaving them with a profound lack of agency (See de Bie et al., 2021 for further discussion of these points).

We therefore recommend positioning underrepresented student partners to effect a culture shift but ensuring that they have the support and affirmation for, and sometimes a necessary respite from, doing this work.

5.3. Embracing non-STEM student partners’ contributions to humanizing STEM

Embracing the potential of non-STEM students as pedagogical partners with STEM faculty can contribute to humanizing STEM in a variety of ways through focusing on classroom dynamics and through drawing on humanities and social sciences practices that alter what student partner Lee (2021) calls “structures of engagement with students to provide deeper understanding and clarity of topics” (1). About working with a student partner who did not have disciplinary experience, associate professor of biology Seshan (2022) reflects: “this ended up being an advantage if I’m honest: my [student partner] was able to focus on classroom dynamics and the pulse of the classroom rather than get mired in the content” (2). Similarly, assistant professor of biology Adam Williamson, asserts:

[My student partner’s] academic expertise is in education, and I’m a biologist. I think the fact that our partnership crossed disciplines is important. For me, the conceptual level of our weekly conversations was elevated because the course content itself was not our focus …. we immediately fell into conversations about student-centered learning rather than course content (Weiler and Williamson, 2020, p. 2, 5).