Abstract

Introduction:

When teachers are being professional in terms of professional standards, they follow their daily routine to produce quality work and wish to be seen as professionals in terms of their status. This is easier said than accomplished. In Pakistan, teaching has become a profession of last resort for many educated young individuals, despite efforts to raise the profession's status by investing in improving teacher management, fostering political support for teacher licensing, and prioritizing teacher development. Although there are examples where reform initiatives have shown positive outcomes in the classroom, the prevailing situation is such that these examples often go unnoticed due to the reforms failing to make a substantial impact, particularly in public school classrooms. Teachers are frequently criticized for their substandard practice and lack of rigorous preparation. The professional status of teachers, therefore, continues to show a declining trend. However, teachers seem to disagree with notions that appear to de-professionalize their profession.

Methods:

Large-scale nationwide research was conducted to explore and understand teachers' perspectives on their professional status and the measures that have been taken to enhance their status from a broad perspective by using a survey design. Data were collected from 4,165 teachers from four provinces of Pakistan using a multistage stratified sampling technique to ensure the sample was representative of the entire country. The collected data were analyzed using both descriptive and inferential statistical techniques. Factor analysis was conducted to find the key underlying dimensions of attributes to unpack teachers' core professional competencies.

Results:

The research study utilized the teachers' lens to highlight and discuss the interplay between how they see themselves as professionals in terms of their status and regard, how they strive to be professionals in terms of practicing professional standards (the being), and how various measures have been undertaken to enhance teachers' status so that they can be seen as a professional (the becoming).

Discussion:

The key premise of the research study is that teachers, when they are being professional, they also need to be recognized as professionals for greater and demonstrable execution of professional standards at the classroom level.

1. Introduction

Over the past two decades, concerted efforts have been made globally to upgrade the profession and improve the quality of teaching and learning by investing strategically in teacher development. For example, Darling-Hammond (2017) presented teacher education policy reforms and practices in Australia, Canada, Finland, and Singapore in comparison with the United States. There are also examples of initial teacher education programs from diverse contexts, such as Jamaica, Greece, and Nigeria (Chalari et al., 2023).

On the one hand, teacher development initiatives have borne good results in many quarters and have helped teachers produce better quality work; on the other hand, these have pushed teachers to do more work, following a compliant mode with very little reward or recognition, resulting in educators questioning their sense of professionalism (Furlong et al., 2000; Flores and Shiroma, 2003; Hall and Schulz, 2003; Rizvi and Elliott, 2007). When teachers are being professional (Hargreaves, 2000) in terms of the professional standards, they follow their daily routine to produce quality work and also wish to be seen as professionals (Hargreaves, 2000) in terms of their status, standing, regard, and levels of professional reward.

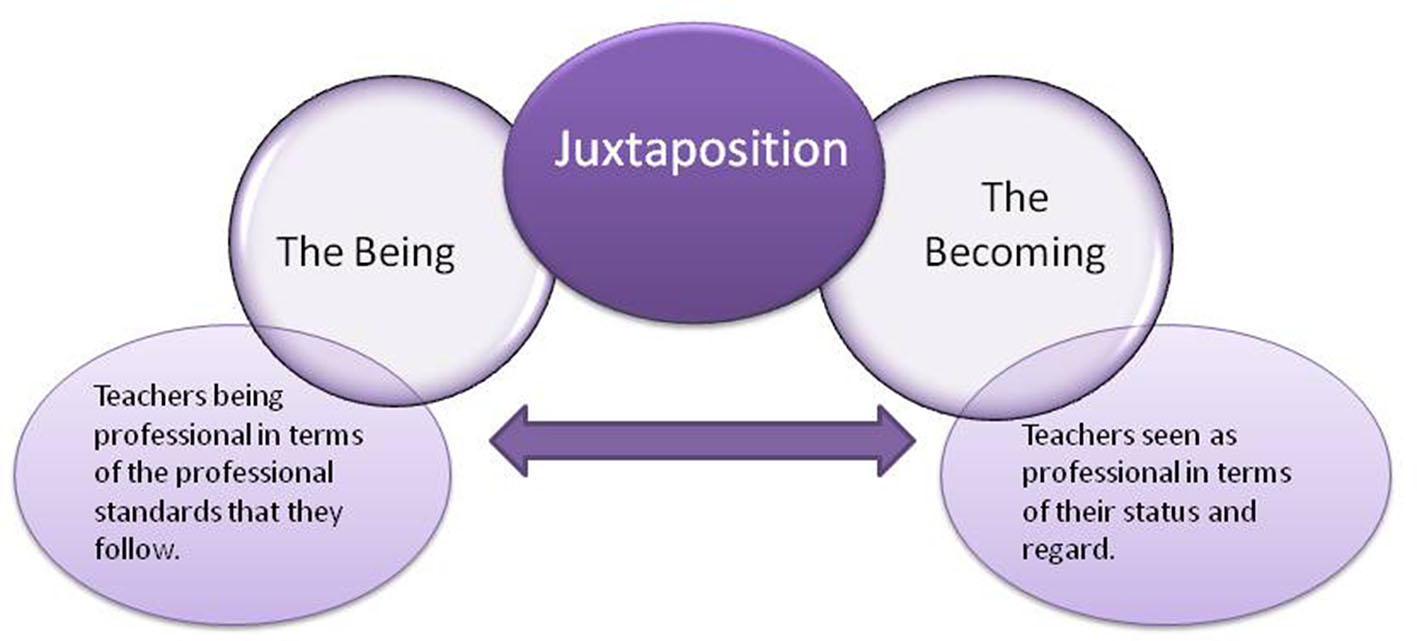

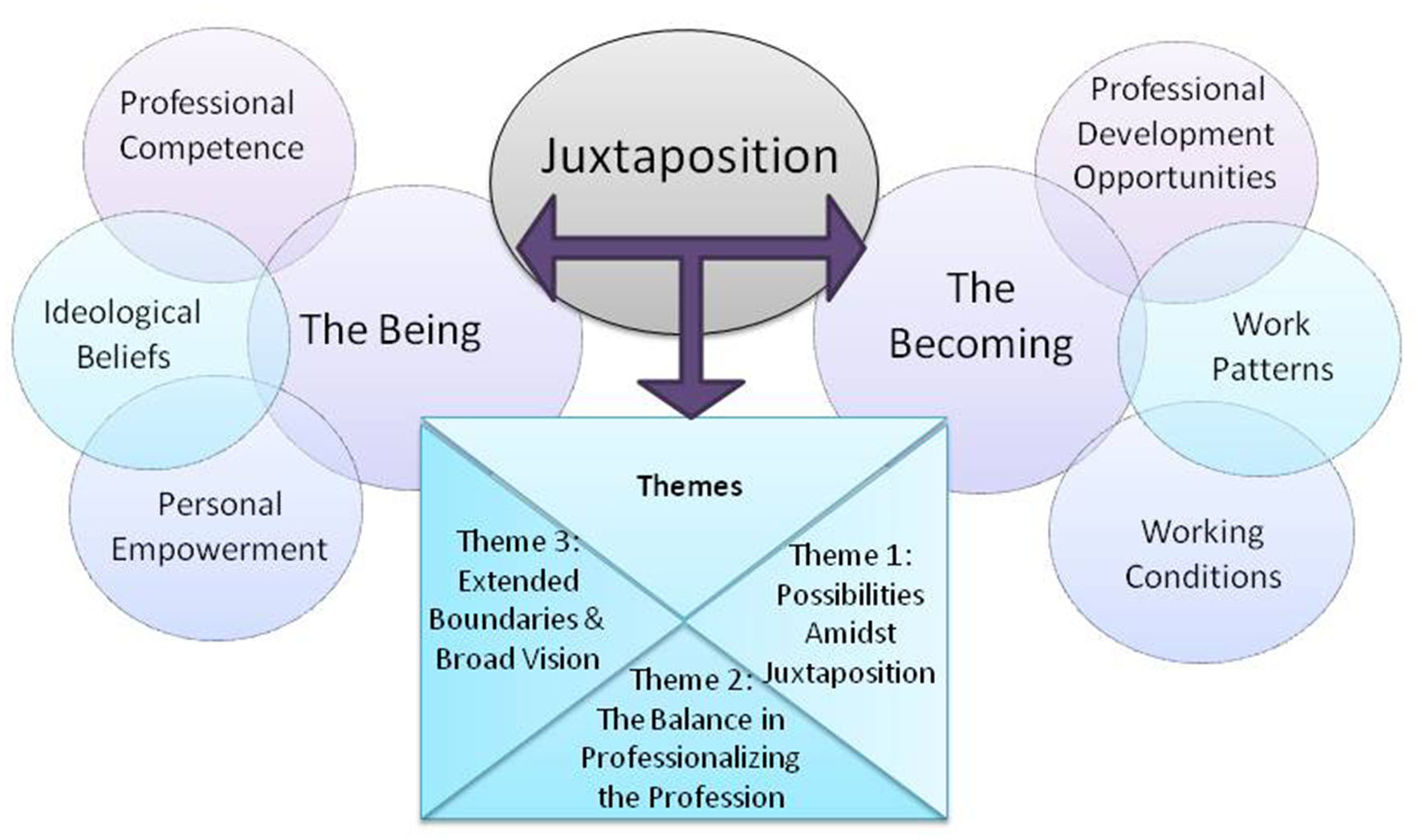

Research studies on the status of teachers and the teaching profession (Hargreaves et al., 2006; Burns and Darling-Hammond, 2014; Symeonidis, 2015; Dolton et al., 2018; Price and Weatherby, 2018; Thompson, 2021) have brought forward the existing trends of teacher status that exists around the world. There are countries such as China, Japan, South Korea, New Zealand, Finland, and Singapore where the teaching profession is highly valued and teachers are being professional, enabling students to learn more effectively (Burns and Darling-Hammond, 2014; Darling-Hammond, 2017; Dolton et al., 2018). The positive perceptions of their status are not only linked to better students' learning but also closely tied to various critical aspects of quality education. These perceptions help teachers become professionals through continuous professional development, involvement in research, collegial collaboration with other teachers, and engagement in decision-making (Symeonidis, 2015). There are also examples where, despite efforts to raise the status of the profession by investing in improving teacher management, developing political will for teacher licensing and certification, increasing equity in teacher placement, improving the school environment, and prioritizing teacher development, teachers' professional status have remained a point of concern. As per the Global Teacher Status Index 2018, most significant declines in teachers' status were witnessed in Greece (2nd out of 21 in 2013 down to 6th out of 21 in 2018) and Egypt (6th out of 21 in 2013 down to 12th out of 21 in 2018) (Dolton et al., 2018). In Pakistan, the reforms have generally failed to make a substantial impact, particularly at the public school classroom level, where the teachers are criticized for their substandard practice and lack of rigorous preparation. Their professional status, therefore, continues to show a declining trend. However, teachers seem to disagree with the notions that appear to de-professionalize the profession. Previous studies have found teachers defending their own profession and considering themselves as confident and capable professionals, unlike the popular opinion of regarding teachers as detached professionals (Rizvi and Elliott, 2005, 2007), highlighting the gap between rhetoric and reality in terms of teachers' professional standing and status. This research study uses the perspective of teachers to illustrate and discuss the interplay or juxtaposition between how teachers see themselves as professionals in terms of their status and regard, how they strive to be professionals in terms of practicing professional standards (the being), and how various measures have been undertaken to enhance teachers' status so that they can be recognized as professionals (the becoming). Figure 1 reflects the two-way construction between being professional and becoming professional, which is theoretically elaborated in the subsequent section and forms the basis of the research reported in this study.

Figure 1

Juxtaposition of being professional and becoming professional (initial framework).

2. Being a professional and becoming a professional: exploring the construct

Simply put, the being refers to the professional identity that teachers associate with and the professionalism that encapsulates their professional identity. Since UNESCO's 1966 recommendation, which recognized teachers as professionals and defined their professionalism as (a) a form of public service that requires expert knowledge and specialized skills acquired through rigorous and continuing study and (b) a sense of personal and corporate responsibility for the education and welfare of the pupils in their charge (UNESCO and ILO, 2008), systematic initiatives to unravel the meaning of a teacher's professionalism and professional identity have gained momentum.

Kelchtermans (2009) defined professional identity as self-understanding. He explained that self-understanding encompasses one's understanding of oneself at a certain moment in time (product) and the recognition that this product results from an ongoing process of making sense of one's experience and their impact on self (Kelchtermans, 2009, p. 261). For Connelly and Clandinin (1999), teachers' identities are shaped by the stories they live by and are given meaning through the knowledge formed within the landscapes in which teachers work and discuss their personal and collective experiences (Craig, 1999). Clandinin et al. (2006) explained that the stories to live by are multiple, fluid, and ever-evolving. Consequently, professional identity is understood as a dynamic ongoing process (Conway, 2001) that is situational (Korthagen, 2017) and emotionally developed (Day, 2004). It plays a key role in teachers' commitment, distinguishing those who are caring, dedicated, and prioritize their profession from those who put their own interests first (Day et al., 2005).

The dynamic ongoing process of professional identity formation can be observed in a study conducted to explore the relationships between school reforms and teacher professionalism in Pakistan. The study illustrated that, in reform initiatives where reformers develop trust relationships with teachers, develop their capacities, and provide them with opportunities to expand upon their capabilities, teachers regard themselves (self-understanding) as confident and capable professionals who can make decisions and undertake responsibilities, who understand that it is important to collaborate and learn from one another, and who are willing to undertake leadership roles (Rizvi, 2003; Rizvi and Elliott, 2005). The evidence here presents a group of teachers who are being professional.

However, questions have been raised about teachers' sense of professionalism and the professional standards that they adhere to when stories of teachers mishandling their professional responsibilities become known through popular media. Evaluation studies on teachers' classroom practices in Pakistan have also yielded mixed results. Kizilbash (1998) and the Social Policy and Development Centre (SPDC) (2003) reported that effective practices last only until the program's life and then generally fade away. In addition, there are reports (Rizvi and Nagy, 2016) that illustrate a continued but average-to-moderate impact at the school classroom level after the program ends. Furthermore, there are examples of failing schools (Hoodbhoy, 1998; Ishaq, 2019), raising serious questions about teachers' professionalism and professional practice and directing attention toward a group of teachers who need support in developing professional practice.

The attention has thus been diverted to becoming a professional, a notion closely tied to measures taken for teacher professionalization and raising teachers' status so that teachers who are being professional can be seen as professionals and so that concrete actions can be taken to enhance teachers' professional practice, ultimately leading to student learning and school improvement. Processes of teacher development in contexts such as Finland, Singapore, Canada, and Australia (Darling-Hammond, 2017) have augmented some practical routes, such as standards for teaching and special clinical training approaches, which have brought teachers' status to the forefront. For example, through a clinical training approach aiming at balancing teachers' professional and personal competencies, Finland has managed to achieve teaching as a respected profession in which teachers have ample authority and autonomy, including responsibility for curriculum design and student assessment, which engages them in a continuous reflection of practice. Another example is the Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL), which is working with various states to implement processes of appraising teachers at different points in their careers and is recognizing increasing levels of accomplishments. While these examples offer important insights, they cannot be conclusive as each country has its own unique context and cultural heritage within which the being and the becoming of professionals are set. However, the contexts within which teachers work are also changing. For example, cosmopolitanism has transcended boundaries and can be found throughout Asia with its variety of religious and cultural traditions (Rizvi and Choo, 2020). The global pandemic has also redefined teachers' work and has illustrated various avenues of learning such as homeschooling and online forms of remote learning (Ross et al., 2021; Mifsud and Day, 2022).

Evidence suggests that, in changing times, teachers should be seen as autonomous professionals, not mere executors of plans. This means that teachers' voices, needs, and aspirations must be considered in the planning and implementation of teacher policies (Karousiou et al., 2019). In addition, teachers' professional relationships, collaboration with their colleagues, and meaningful reflection influence their becoming professional (Davey, 2013; Korthagen, 2017; Rizvi, 2017), suggesting that being professional needs to be more intertwined with becoming professional.

3. Being and becoming professional within the educational context in Pakistan

There are three distinctive school systems in Pakistan:

Government (public sector) system of primary and secondary schools.

Private school system (community-based, non-profit, and for-profit schools).

Religious school (Deeni Madaris) system.

According to The Academy of Educational Planning and Management (2021), Pakistan currently has a total of 305,763 schools, out of which 189,748 (62%) are public sector schools and 116,015 (38%) are private sector schools, a figure that also includes 31,115 Deeni Madaris. The Pakistan Social Living Standards Measurement Survey 2019–2020 revealed that Pakistan is struggling to meet quality standards with a large number of out-of-school children, a net school enrollment rate of 64% at the primary school level (6–10), and a literacy rate (10 years and above) just ~60%.

In 1947, when Pakistan became independent, teachers were considered the key agents by transforming the ideals of the newly found nation's leaders who wished to shift the emphasis of education from colonial-administrative objectives to a professional and technical bias suiting a non-dependent, progressive economy (Hoodbhoy, 1998). The years that followed saw a boom of privatization in education, implementation of several small and large-scale educational reforms, and renewed focus on public–private partnerships.

Traditionally, teacher development in Pakistan has followed two key pathways: Pre-service teacher education and in-service teacher education. According to the National Education Census, there are 217 teacher training institutions in the country. Table 1 gives the sector-wise (public/private) distribution of teacher training institutions, enrollment of teacher training institutions, and the total number of teaching faculty of the institutions.

Table 1

| Sector | Teacher training institutes | Enrollment | Teaching faculty |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public | 158 (73%) | 70,862 (93%) | 3,493 (92%) |

| Private | 59 (27%) | 5,365 (7%) | 298 (8%) |

Sector-wise distribution of teacher training institutes.

The Academy of Educational Planning and Management (2018).

The latter part of the 20th century saw the emergence of a number of initiatives to further teachers' classroom teaching competency and, consequently, their professional status. These reform initiatives were mostly foreign-funded and managed by governmental and non-governmental organizations. For example, the main goal of the Sindh Primary Education Development Program funded by the World Bank was to improve access to primary education, especially for girls, with equity and quality (The Bureau of Curriculum and Extension Wing, 1997). Aga Khan University's Institute for Educational Development (AKU-IED) took part in the USAID-funded Education Sector Reform Assistance initiatives in 2000 to deliver effective and relevant teacher education and development programs, with a focus on improving classroom teaching practice in the province of Sindh using an indigenous approach called the cluster-based mentoring program. The World Bank and UK DFID funded the Punjab Education Sector Reform Program. Started in 2003, this program has undertaken major investments in education with three overarching goals: improving access, quality, and governance in education. In 2009, the Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade, and Development and the Aga Khan Foundation funded AKU-IED's Strengthening Teacher Education in Pakistan project to develop teachers' capacity in four key subject areas: math, science, social studies, and English.

While there are examples of positive effects of reform initiatives at the classroom level (Rizvi and Elliott, 2005; Riaz, 2008; Rizvi and Nagy, 2016; Aslam et al., 2019) and on many hardworking and dedicated teachers (Memon and Bana, 2005; Shamim and Farah, 2005; Safida, 2006; Rizvi, 2015, 2019), the situation is such that these examples mostly go unnoticed because the reforms generally failed to make a substantial impact at the classroom level. Teachers' professional status continued to show a downward trend. It has been argued that the teacher development initiatives failed to make a substantial impact due to various reasons: they did not account for each school's contextual reality, the training was conducted in places away from the school, teacher development and implementation plans were prepared by experts without involving the teachers, and a poor accountability and monitoring system failed to sustain teacher initiatives. Previous research studies (Rizvi, 2003; Hasan, 2007; Rizvi and Elliott, 2007; Siddiqui, 2010) have illustrated that a myriad of top-down reform agendas left teachers bewildered, unmotivated, and doubtful of their own capabilities to successfully improve the teaching and learning processes.

More recently, the government has undertaken some concrete measures to formalize, streamline, and institutionalize in-service and pre-service teacher training and accreditation processes and, consequently, enhance teachers' professional status. In November 2008, under the Strengthening Teacher Education in Pakistan initiative, the Ministry of Education adopted and notified 10 National Professional Standards for Teachers in Pakistan. These standards define competencies, skills, and attributes deemed as essential targets for teachers and teacher educators (Ministry of Education, 2009). The National Education Policy (Ministry of Education, 2009) presents 22 key policy drivers, which address issues concerning pre-service training and standardization of qualifications; professional development; teacher remuneration, career progression and status; and governance and management of the teaching force. Provincial governments, particularly the former Directorate of Staff Development and currently the Quaid-e-Azam Academy for Educational Development in Punjab, have systematically engaged in a paradigm shift from traditional cascade models to continuous professional development, encouraging an interactive and constructivist approach to learning based on the processes of reflection, collaborative work, mentoring, and problem-solving (UNESCO Centre of Education and Consciousness, 2013). Teacher licensing is a major initiative that has been taken in recent years to raise the professional capacity of teachers and to professionalize the teaching workforce. This is the first time in the history of Pakistan that teachers will be obtaining licenses as a testimony to their teaching quality and professional standing (Ali and Ahmed, 2022). In 2012, the Higher Education Commission revised the curriculum for the B.Ed. (Hons.) elementary and the Associate Degree in Education. In line with the standards of other professional degrees such as medicine, engineering, or law, the 4-year B.Ed. (Hons.) degree intends to develop teachers as professionals who require comprehensive content knowledge and intensive professional training (Higher Education Commission (HEC), 2012).

The report on the status of teachers in Pakistan makes an important claim that “once the new training programs and policies are fully in place teachers will be better prepared to respond to the educational needs and aspirations of all children” (UNESCO Centre of Education and Consciousness, 2013, p. 28). Pakistan's educational history consists of detailed and comprehensive documents and idealistic reform initiatives that were created with a lot of enthusiasm and fervor but could not bear the results that they were intended to bear. It has been argued elsewhere (Rizvi, 2015) that policymakers need to realize that, unless teachers are recognized as professionals who are actively involved in the decision-making apparatus and assume leadership roles, who build collaborative teams and networks, and who are passionate and morally strong, these targets of quality education may remain unachievable.

Large-scale nationwide research was conducted to explore and understand teachers' perspectives on their professional status and the measures that have been taken in the past and are currently being taken to enhance teachers' status from a broad perspective, using a survey design. The research addressed the following questions:

What are teachers' perspectives about their professional status?

What measures have been taken to enhance teachers' status?

This research study focuses on the juxtaposition or interplay between how teachers see themselves as professionals in terms of their status and regard, how they strive to be professionals in terms of practicing professional standards (the being), and what measures have been undertaken to enhance teachers' status (the becoming).

4. Materials and methods

Data were collected from 4,165 teachers from the four provinces of Pakistan, namely, Punjab, Sind, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and Baluchistan, as well as other regions (Islamabad, Azad Jammu Kashmir, and Gilgit-Baltistan) using a multistage stratified sampling technique to ensure that the sample was representative of the entire country.

4.1. Sampling decisions

Teachers were selected proportionately from the four provinces, namely, Punjab, Sindh, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and Balochistan, as well as other regions, which included the Islamabad Capital Territory (ICT), Azad Jammu and Kashmir (AJK), and Gilgit-Baltistan (GB), to make the sampling representative of the teaching levels in the provinces/regions. From each province, urban and rural districts were selected. A total of 09 districts were included in this study.

Pakistan's 2023 population is estimated at 240,485,658 people at mid-year. Out of the total population, 34.7% is urban (83,500,516 people in 2023) and 65% is rural (156,985,142 people in 2023) (Worldometer, 2020). The current rural-urban divide concerning the aggregate teaching force in Pakistan is 59.51% and 40.48%, respectively (The Academy of Educational Planning and Management, 2021). It was, therefore, important to select teachers from both rural and urban regions.

Within each urban and rural district, both public and private schools were randomly selected. From these schools, teachers were randomly selected. All teachers teaching at the elementary, middle, and secondary levels from the randomly selected schools from each district were included in the study. This category also included school principals. All school principals/vice-principals and school in-charge/section heads were invited to participate in the survey research. The estimated sample size of teachers was 5,100. In all, 4165 teachers participated in the study, representing a response rate of 81.6%. The percentage of teachers from each province/region corresponded approximately to the percentage of teachers stated by official AEPAM Statistics, 2016–17 (The Academy of Educational Planning and Management, 2018). Table 2 presents the region and district-wise distribution of the participants.

Table 2

| Province/ region | District | No. of teachers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Public | Private | ||

| Punjab | Lahore | 501 | 455 |

| Faisalabad | 383 | 140 | |

| Rawalpindi | 384 | 116 | |

| Sheikhupura | 122 | 63 | |

| Sindh | Karachi | 238 | 528 |

| Sukkur | 179 | 005 | |

| KPK | Peshawar | 172 | 117 |

| Chitral | 162 | 115 | |

| Baluchistan | Quetta | 114 | 41 |

| Other regions | Islamabad | — | 60 |

| Gilgit-Baltistan | 94 | 117 | |

| Azad Jammu Kashmir | 43 | 16 | |

| Total | 2,392 | 1,773 | |

Distribution of participants.

4.2. Sample characteristics

The demographic analysis illustrated that the teachers come from diverse backgrounds. Teachers from both public schools (57%) and private schools (43%) participated in the study from different districts of Pakistan. They came from high- to low-income schools. They taught different subjects at different levels, from primary to higher secondary. There were both and male teachers. Approximately, an equal number of teachers above (n = 1,837) and below (n = 2,177) the age of 40 participated in the study. Overall, 43% of the teachers had teaching experience of more than 15 years, and 57% had teaching experience of less than 15 years. The key characteristics are presented in Table 3.

Table 3

| Key characteristics | Teachers from public schools | Teachers from private schools |

|---|---|---|

| Number of teachers | 2,392 (57%) | 1,773 (43%) |

| Female teachers | 1,443 (60%) | 1,561 (88%) |

| Male teachers | 949 (40%) | 208 (12%) |

| Age ≥ 40 | 1,275 (55%) | 598 (34%) |

| Experience ≥ 15 years | 1,295 (55%) | 486 (28%) |

| Academic qualification (M.A./M.Sc./M.Com.) | 1,468 (63%) | 1,021 (58%) |

| Professional qualification (M.Ed. and B.Ed.) | 1,756 (73%) | 623 (35%) |

| Salaries ≥ 50,000 | 1,019 (45%) | 358 (20%) |

Teachers' key characteristics.

4.3. Description of the questionnaire

The data were collected from teachers with the help of a purposefully developed structured questionnaire. Using information from various available studies in the literature (Herrmann, 1972; Hoyle, 2001; Rice, 2005; Hargreaves et al., 2006; Ministry of Education, 2009; Burns and Darling-Hammond, 2014; Lankford et al., 2014; Symeonidis, 2015), the researcher's own experience, and the concepts noted in the theoretical background, a questionnaire was designed.

The questionnaire comprised four parts. Part A of the questionnaire requested demographic or factual information concerning the respondents' gender, age, place of work, and personal and professional biographical data. It also contained some general background information about the context. Part B asked the teachers to report on a Likert scale to capture their perceptions about their professional status from various angles. Part C collected the teachers' views on the various measures that have been undertaken to enhance their professional status. Part D provided teachers with an opportunity to express any general issues or concerns.

4.4. Refining and piloting of questionnaire

The questionnaire was translated into the national language of Pakistan, as well as the local languages of the different respondents. Members of the research team translated the tools themselves, with support from local language experts to retain the literal meaning of the items in the tools. The research assistants' training and regular monitoring of the work also ensured the collection of reliable and authentic data. Furthermore, the questionnaire's reliability was measured using the internal consistency method associated with Cronbach's alpha. Its content validity was established by giving the tool to six educators with expertise in the content areas to read the tools specifically for the purpose of checking that the items were measuring the concepts that they were supposed to measure.

The questionnaire was pilot-tested with ~100 respondents for the purpose of checking the reliability, time consumption, and content comprehensiveness. The purposes of piloting the tools were as follows:

To refine the questionnaire.

To assess the viability of pursuing a large nationwide study.

To assess the feasibility of entry and logistical plans.

The key points of improvement from the pilot were as follows:

Clarification of the meanings of several items in the questionnaires.

Improvement of the instructions for the questionnaire.

Improvement of the training procedures for administering the questionnaires.

Inclusion of items related to teaching during emergency situations to give due coverage to teachers' status in the changing scenario and also to facilitate the mental and emotional engagement of the respondents with the questionnaire.

4.5. Data collection procedures

Eighteen research assistants worked with the core team members to collect data from the selected districts. A 2-day online training exercise was arranged for the research assistants. The training aimed to provide a detailed description of the data collection tools. Issues related to the administration of the data collection instruments and research ethics were also discussed with the research assistants.

Research assistants self-administered the questionnaires among the teachers and collected them back at a time suggested by the teachers. Considering the pandemic situation, flexibility was added to the design. A hybrid data collection method that included both face-to-face and online portions was employed. Data from most private schools were collected using online means. Online meetings were held with the school principals to discuss data collection modalities and the number of participants required from each school. Data collection tools were shared and discussed with the school principals. The online data submission process was kept anonymous to uphold ethical principles.

4.6. Follow-up and supervision of field-based tasks

Online monitoring and supervision were organized due to the COVID-19 pandemic situation. This involved more perseverance and exhaustive engagement with the research team than what was originally planned.

Regular meetings were organized with all the research assistants once a week until they had completed data collection. The meetings provided avenues of intellectual discourse and emotional connection to the research assistants hailing from diverse contexts and realities. As the research required direct administration of the questionnaire to all the teachers, open, supportive, and transparent channels of communication through emails and WhatsApp groups were established so that field-based concerns could be communicated and resolved in a timely manner.

4.7. Data analysis techniques

The data were analyzed using both descriptive and inferential statistical techniques using SPSS within two constructs: the being and the becoming. The analysis and results of Part B of the questionnaire will be addressed first in Section 5, exploring the being professional construct (how teachers see themselves as professionals in terms of their status and regard and how they strive to be professionals in terms of practicing professional standards), followed by the analysis of Part C of the questionnaire in Section 6, exploring the becoming professional construct (what measures have been undertaken to enhance teachers' professional practice). Section 7 will bring together the discussion on the being and the becoming professional constructs for drawing meaningful themes and implications.

5. Results and analysis of the being professional construct

Teachers' responses to items written to investigate teachers' professional status were collected on a 5-point Likert scale consisting of 24 items. The responses were converted into a numerical scale. The numerical value assigned to each response is given below:

| Strongly Agree (SA) | Agree (A) | Uncertain (U) | Disagree (D) | Strongly Disagree (SD) |

| 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

The frequency distribution of each variable was calculated using the SPSS. The principal components analysis (PCA) method was used to extract the factors. These were rotated using the Varimax rotation to produce a more meaningful interpretation of the underlying structure of teachers' status.

Four criteria were used to extract factors. First, the criterion of simple structure was employed. This means that the items that loaded for more than one factor were either omitted to achieve a purer measure of the different dimensions of teacher status or they were assigned to the factor for which they had the highest loading value, provided that the item also contributed to the meaning of the factor. Second, items were evaluated for conceptual clarity. This means that those items that loaded on a factor with a value greater than or equal to 0.40 and those that contributed logically to the meaning of the factor were considered significant for the factor. Third, items were eliminated if they substantially reduced the internal consistency of the items in the factor, as measured by Cronbach's alpha. Fourth, Kaiser's (Bryman and Cramer, 2005) criteria and Cattell's (Bryman and Cramer, 2005) scree test method were employed to decide the number of factors to be retained. Only those factors that had eigenvalues greater than 1 or that lay before the point at which the eigenvalues seemed to level off were retained.

Three factors explain the being professional construct of the professional status. For overall schools, the three factors had eigenvalues exceeding 1, and they explained 24.42%, 8.70%, and 4.70% of the variance, respectively. For public schools, the three factors had eigenvalues exceeding 1, and they explained 25.04%, 9.89%, and 4.72% of the variance, respectively. Similarly, for private schools, the three factors had eigenvalues exceeding 1, and they explained 25.01%, 5.26%, and 4.30% of the variance, respectively.

Factor 1 was titled “The Professional in the Being Professional Construct of Teachers' Status,” Factor 2 was titled “The Ideological Values in the Being Professional Construct of Teachers' Status,” and Factor 3 was titled “The Personal Empowerment in the Being Professional Construct of Teachers' Status”. Tables 4, 5, 7 present these factors with their factor loadings. For the sake of brevity, views of “Agree” and “Strongly Agree” were collapsed together to form one view of “Agree” that is numerically equal to 3 and represented by “A.” Similarly, views of “Disagree” and “Strongly Disagree” were collapsed together to form one view of “Disagree” that is numerically equal to 1 and represented by “D.” Views of “Uncertain” values remained unchanged but were assigned a new numerical value equal to 2 and represented by “U.” This rule has been applied to all the tables that present factors.

Table 4

| Factor 1: Professional competencies in the being professional construct of teachers' status | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall schools | Public schools | Private schools | ||||||||||

| Items | Loading | A | U | D | Loading | A | U | D | Loading | A | U | D |

| PTS 16: I am regarded as a good teacher in my community because I use diverse and modern instructional practices in my class. | 0.61 | 3,639 (88%) | 318 (8%) | 174 (4%) | 0.57 | 2,024 (86%) | 211 (9%) | 125 (5%) | 0.64 | 1,615 (91%) | 107 (6%) | 49 (3%) |

| PTS 17: I can modify the curriculum content or delivery to fulfill the learning needs of my students. | — | — | 0.44 | 1,526 (65%) | 406 (17%) | 417 (18%) | — | — | — | — | ||

| PTS 18: I believe that I have the ethical responsibility to educate students for life and not only for passing school exams. | 0.69 | 3,906 (94%) | 142 (3%) | 99 (3%) | 0.67 | 2,200 (93%) | 86 (3%) | 89 (4%) | 0.66 | 1,706 (96%) | 56 (3%) | 10 (1%) |

| PTS 19: Parents consider me a good teacher as my students are mostly high achievers. | 0.69 | 3,731 (89%) | 322 (8%) | 93 (3%) | 0.71 | 2,121 (89%) | 183 (8%) | 70 (3%) | 0.66 | 1,610 (91%) | 139 (8%) | 23 (1%) |

| PTS 20: I feel that I am a better teacher because of my teacher training. | 0.71 | 3,783 (91%) | 258 (6%) | 100 (3%) | 0.72 | 2,134 (90) | 162 (7%) | 76 (3%) | 0.68 | 1,649 (94%) | 96 (5%) | 24 (1%) |

| PTS 21: I feel that I am prepared to modify my teaching as per the changing requirements due to emergencies (e.g., teaching in the post-COVID-19 classroom). | 0.73 | 3,775 (91%) | 255 (6%) | 118 (3%) | 0.74 | 2,102 (88%) | 189 (8%) | 86 (4%) | 0.71 | 1,673 (94%) | 66 (4%) | 32 (2%) |

| PTS 22: I make use of various professional development opportunities to enhance my teaching skills. | 0.75 | 3,780 (92%) | 229 (6%) | 127 (3%) | 0.77 | 2,091 (89%) | 161 (7%) | 112 (4%) | 0.71 | 1,689 (95%) | 68 (4%) | 32 (2%) |

| PTS 24: I plan my lesson based on the reflections from the previous class. | 0.64 | 3,806 (91%) | 244 (6%) | 135 (3%) | 0.62 | 2,091 (89%) | 164 (7%) | 109 (4%) | 0.65 | 1,665 (94%) | 80 (5%) | 26 (1%) |

| Cronbach's Alpha Values | 0.835 | 0.831 | 0.835 | |||||||||

Factor 1.

Table 5

| Factor 2: Ideological beliefs in the being professional construct of teachers' status | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall schools | Public schools | Private schools | ||||||||||

| Items | Loading | A | U | D | Loading | A | U | D | Loading | A | U | D |

| PTS 02: I joined the teaching profession by choice | 0.67 | 3,813 (92%) | 182 (4%) | 152 (4%) | 0.68 | 2,186 (92%) | 102 (4%) | 89 (4%) | 0.67 | 1,627 (92%) | 80 (5%) | 63 (3%) |

| PTS 03: I believe that I play a key role in developing children as independent and responsible citizens of Pakistan | 0.61 | 3,968 (96%) | 139 (3%) | 46 (1%) | 0.68 | 2,240 (94%) | 105 (4%) | 37 (2%) | 0.63 | 1,728 (97%) | 34 (2%) | 9 (1%) |

| PTS 06: I am responsible for setting moral standards for my students | 0.60 | 3,942 (95%) | 122 (3%) | 82 (2%) | 0.56 | 2,246 (94%) | 74 (3%) | 58 (3%) | 0.60 | 1,696 (96%) | 48 (3%) | 24 (1%) |

| PTS 10: My work environment at school determines my status | 0.43 | 3,447 (84%) | 415 (10%) | 264 (6%) | 0.42 | 2,003 (85%) | 205 (9%) | 155 (6%) | 0.49 | 1,444 (82%) | 210 (12%) | 109 (6%) |

| PTS 11: I feel that, according to the norms of my society, teaching is the most respectable profession for me | 0.61 | 3,604 (87%) | 316 (8%) | 229 (5%) | 0.59 | 2,097 (88%) | 166 (7%) | 115 (5%) | 0.61 | 1,507 (85%) | 150 (8%) | 114 (7%) |

| Cronbach's Alpha values | 0.728 | 0.742 | 0.712 | |||||||||

Factor 2.

Inspection of the correlation matrix for the three factors revealed the presence of many coefficients of 0.3 and above. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin value for both public and private school teachers was 0.88 overall. For the public school scale, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin value was 0.885. For the private school scale, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin value was 0.876. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin value for the three factors exceeded the recommended value of 0.6 (Pallant, 2001). Bartlett's test of sphericity (Pallant, 2001) for the factors also reached statistical significance, supporting the factorability of the correlation matrix.

5.1. Professional competencies in the being professional construct

The PCA revealed a presence of strong professional construct with item loadings ranging from 0.436 to 0.771 (Table 4) in the three school categories (overall, public, and private), illustrating high to moderate correlation (more than 0.40) with the factor. The respondents' perception counts for the items (except for PTS 17) illustrated strong agreement ranging between 86% and 95% (Table 4). The Cronbach's alpha values of 0.831 for the public school and 0.835 for the private schools and overall demonstrated strong internal consistency of the items.

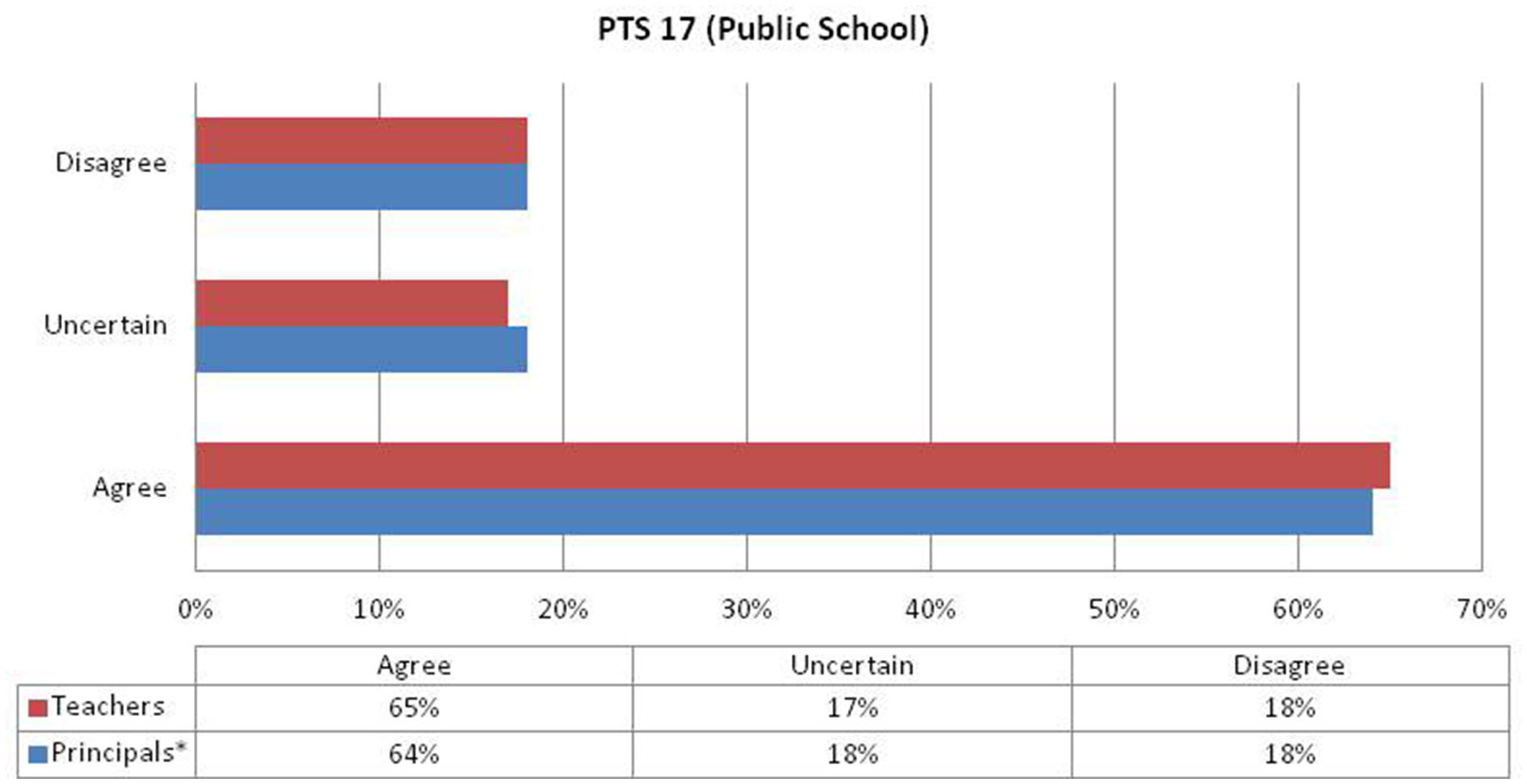

The same items were loaded in three school categories with the exception of PTS 17, which was loaded only in public schools. Public school teachers perceive their capacity to modify curriculum content or delivery to fulfill the learning needs of their students as an important dimension of their being professional construct. However, only 65% of the public school teachers agreed with this item, 17% were uncertain, and 18% disagreed (Table 4). Additional analysis was performed to unpack the levels of agreement between classroom teachers and principals. The principal category also included vice-principals, coordinators, and school in-charge or section heads. The analysis revealed that both teachers (n = 1318, 65%) and school principals (n = 200, 65%) felt equally enabled in terms of modifying the curriculum content or delivery to fulfill the learning needs of their students (Figure 2). This finding is important as it illustrates that teachers feel as enabled as school principals regarding curriculum modification at the classroom level.

Figure 2

PTS 17 - I can modify the curriculum content or delivery to fulfill the learning needs of my students (Public School). *Also included vice-principals, coordinators and school in-charge or section heads.

The professional competencies in the being professional construct of teachers' status emerged as significant in all three school categories—overall, public, and private. This dimension entails the quality, range, and flexibility of teachers' classroom work and the way they develop as professionals to undertake school improvement initiatives and to bring positive change at the classroom level (Hargreaves, 2000).

Teachers perceive that parents and the community consider them good teachers when they use diverse and modern instructional practices in their classes and when their students are high achievers (PTS 16 and 19). This appreciation, according to the teachers, is an important determinant of their professional status and provides evidence of their being professional. The other determinants of teachers' professional beings are as follows: fulfilling their ethical responsibility to educate students for life, planning lessons based on reflection from previous classes, making use of various professional opportunities to enhance teaching skills, and modifying practices due to emergencies such as teaching in the post-COVID-19 classrooms. However, low counts on PTS 17 should be a matter of concern for educational managers and trainers as every teacher should feel enabled to modify content or delivery to fulfill the learning needs of their students.

These findings are particularly important on two counts. First, they illustrate what constitutes “being professional” in the professional status. Second, implicit within PTS 16 and PTS 19 are teachers' claims of “becoming professional,” which require acceptance and appreciation from parents and community members. Many large-scale top-down reforms with good intentions have failed to make a substantial impact at the classroom level (Rizvi and Elliott, 2005; Rizvi and Nagy, 2016) because of their detachment from particular school realities, and the teachers' professional status continued to show a downward trend. It is important to see later in the results what relevant measures have been taken to foster teachers' professional status.

5.2. Ideological beliefs in the being professional construct of teachers' status factor

Item loadings for ideological beliefs in the being professional construct ranged from 0.421 to 0.683 (Table 5), illustrating moderate correlation (0.40 > but > 0.70) with the factor. The same items were loaded in three school categories. The perception counts illustrated strong agreement ranging between 97% and 82%. The Cronbach's alpha values of 0.742 for the public school and 0.712 for the private school demonstrated strong internal consistency within the items (Table 5).

It is clear from the analysis that teachers' professional being is also ideologically constructed. This may be because theoretically, teachers in Pakistan enjoy an elevated status due to their central ideological role in the character-building, social, behavioral, and mental development of Pakistani children. Islam, which is the dominant religion in Pakistan, also pays a lot of respect to the teaching profession. School teachers appear to corroborate the theoretical notions by confirming that they play a key role in developing children as independent and responsible citizens (PTS 03 - public 94% and private 97%) and that they are responsible for setting moral standards for their students (PTS 06 - public 94% and private 96%). Similarly, 88% of public school teachers and 85% of private school teachers believe that teaching is the most respectable profession for them in Pakistan (PTS 11).

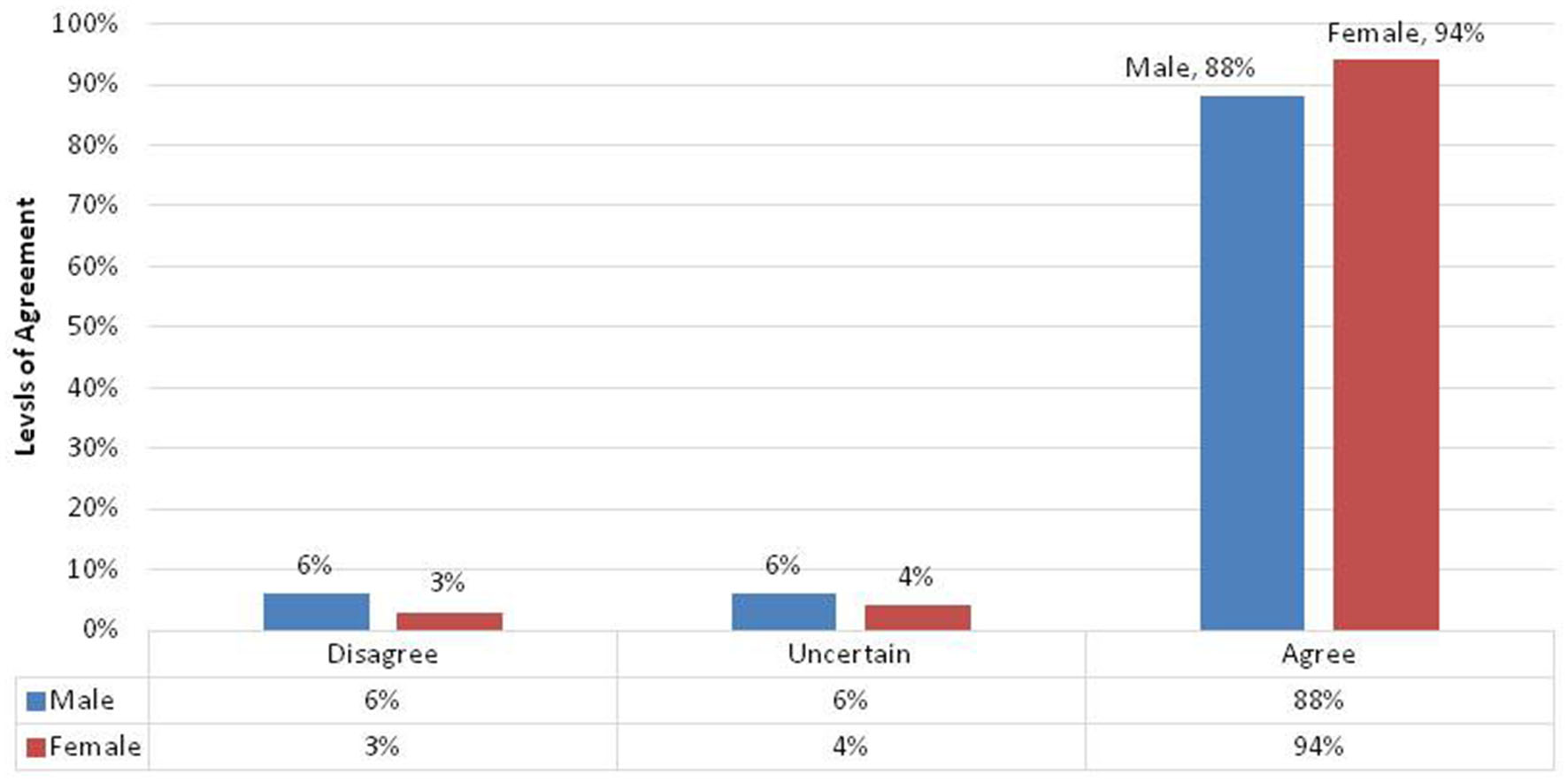

There are two important findings in this construct. First, teachers from both public and private schools voiced that they joined the teaching profession by choice (PTS 02 - 92% both public and private). These findings are in complete contrast to the general view that teaching is the last profession of choice, particularly for male teachers (Ministry of Education, 2009). Since most of the teachers in the sample were women (72%), additional analysis was performed to unpack the levels of agreement of both male and female teachers separately. Additional analysis revealed that teaching was a profession of choice for both male (n = 1,006, 88%) and female (n = 2,803, 94%) teachers (Figure 3).

Figure 3

Public and private school teachers' perceptions of teaching as a profession by choice.

The other important finding is that, in teachers' views (public 88% and private 85%), the working environment plays an important role in helping them being professional and determining their professional status (PTS 10). Relating it to the ideological perspective, one can see the relationship of the school environment with other items factored in, signifying that teachers need a conducive learning environment for fulfilling their moral responsibilities and playing their role in developing children as responsible citizens. The additional analysis illustrated a significant correlation of PTS 10 with other items in the scale (Table 6).

Table 6

| Correlations | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTS2 | PTS3 | PTS6 | PTS10 | PTS11 | |||

| Spearman's Rho | PTS10 | Correlation coefficient | 0.367 | 0.263 | 0.363 | 1.000 | 0.509 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | . | 0.000 | ||

| N | 4,110 | 4,115 | 4,111 | 4,126 | 4,119 | ||

Correlation of teachers' perceptions of the school environment with other items in the scale.

5.3. Personal empowerment in the being professional construct of teachers' status factor

The personal empowerment in the being professional construct of teachers' status construct had loading values ranging from 0.415 to 0.748, illustrating a high to moderate correlation (more than 0.40) with the factor (Table 7). The same items (except PTS 17) were loaded in all school types. The internal consistency measures of Cronbach's alpha were lower than those of other constructs. However, they were retained because of their meaningfulness to the study and also because of high inter-item correlation.

Table 7

| Factor 3: Personal empowerment in the being professional construct of teachers' status | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall schools | Public schools | Private schools | ||||||||||

| Items | Loading | A | U | D | Loading | A | U | D | Loading | A | U | D |

| PTS 04: I play an instrumental role in policy and planning at my school level | 0.52 | 3,408 (83%) | 431 (10%) | 307 (7%) | 0.52 | 2,029 (86%) | 214 (9%) | 134 (5%) | 0.75 | 1,379 (78%) | 217 (12%) | 173 (10%) |

| PTS 05: I play an instrumental role in policy and planning at the national and/or provincial level | 0.70 | 2,179 (53%) | 766 (18%) | 1,175 (29%) | 0.70 | 1,254 (53%) | 409 (17%) | 697 (30%) | 0.70 | 925 (53%) | 357 (20%) | 478 (27%) |

| PTS 17: I can modify the curriculum content or content delivery to fulfill the learning needs of my students | 0.45 | 3,002 (72%) | 574 (14%) | 542 (14%) | — | — | — | — | 0.42 | 1,476 (83%) | 168 (10%) | 125 (7%) |

| PTS 23: I feel that I am empowered enough to make changes in my school | 0.60 | 2,125 (52%) | 953 (23%) | 1,046 (25%) | 0.45 | 1,090 (46%) | 539 (23%) | 726 (31%) | 0.56 | 1,035 (59%) | 414 (23%) | 320 (18%) |

| Cronbach's Alpha Values | 0.585 | 0.511 | 0.674 | |||||||||

Factor 3.

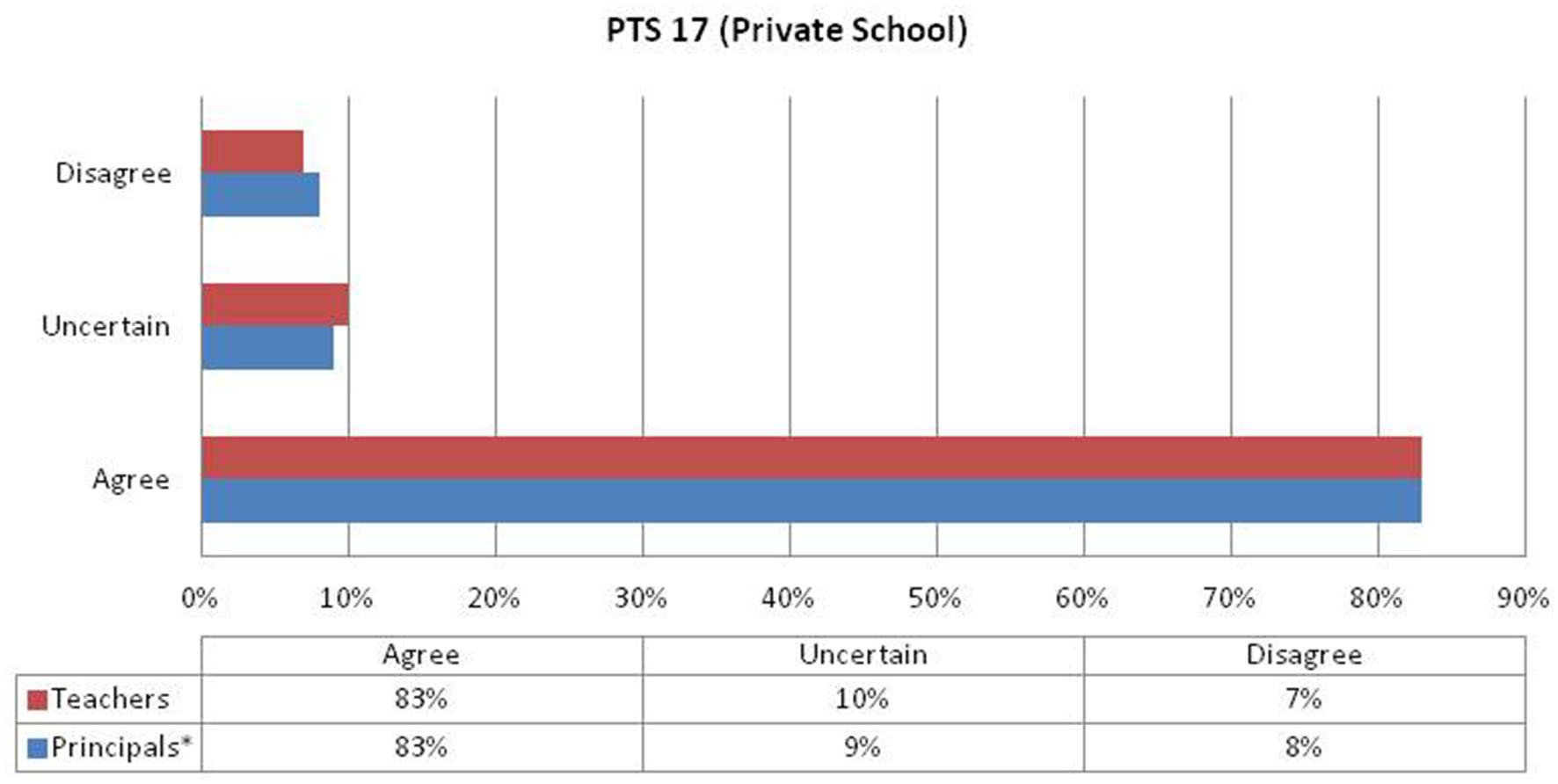

Through this construct, teachers illustrated that their personal identity as capable and confident beings is an important determinant of their professional status. Most of the teachers from public schools (86%) and private schools (78%) reported that they play an important role in policy and planning at their school level (PTS 04). However, the number of teachers who, according to them, are involved in policy and planning at the national and/or provincial level is relatively small, at 53% for both public and private schools (PTS 05). PTS 17 was loaded in the private school category. The same item was loaded in the public school category in Factor 1 (Section 5.1). Although public school teachers feel that they have the capacity, they are not necessarily empowered to make changes in the curriculum content or delivery; contrarily, the majority of the private school teachers (n = 1476, 83%) feel empowered to modify the curriculum content or content delivery to fulfill the learning needs of their students.

Additional analysis was performed to unpack the levels of agreement between private classroom teachers and principals. The analysis revealed that both teachers (n = 1305, 83%) and school principals (n = 167, 83%) felt equally empowered in terms of modifying the curriculum content or delivery to fulfill the learning needs of their students (Figure 4). This finding is important as it demonstrates that private school teachers and principals feel equally empowered regarding curriculum modification at the classroom level.

Figure 4

PTS 17 - I can modify the curriculum content or delivery to fulfill the learning needs of my students (Private School). *Also included vice-principals, coordinators and school in-charge or section heads.

PTS 23 illustrated that private school teachers (59%) appear to feel more empowered to make changes at the school level than public school teachers (46%). This difference in perceptions appears to be rooted in the different school setups. Public schools are managed by the government, supported by government funds, and mandated by the government's curriculum. Contrarily, private institutions are managed by private owners who generate their own funds for managing schools. It may be that private schools' teachers have more of a vested interest in their schools and, therefore, they feel more in authority to make changes.

6. Results and analysis of the becoming professional construct

The teachers' responses to items written to investigate measures to enhance teachers' professional status were collected through questions of varying types, from Yes or No questions to 3-point and 5-point scales. Descriptive analysis of the data was conducted using frequency distributions mainly to unpack the measures that have been taken to enhance the professional competencies of teachers. Wherever applicable, a follow-up analysis was conducted to provide further explanation.

Teachers were invited to respond to a number of specific measures subsumed under six broad categories, namely, general opportunities, specific professional development opportunities, teachers' work patterns, teachers' employment, salaries and benefits, other benefits, and teachers' work conditions. Table 8 summarizes the two specific measures that both public and private teachers identified as the most occurring and the two that they identified as the least occurring under each broad category. The measures were based on the counts of teachers' levels of agreement and disagreement with the items in each overall category.

Table 8

| No | Broad categories | Specific measures | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-most occurring | Second-most occurring | First-least occurring | Second-least occurring | ||

| 1 | General opportunities | Received a salary raise in the last 10 years | Planned and organized professional development programs, such as workshops, and short-duration training, for teachers | Nominated for membership in a professional association (e.g., SPELT) | Received grant/scholarship to further professional qualifications, such as obtaining an educational degree |

| 2 | Specific professional development opportunities | CPD results in greater teacher recognition in a particular skill or area of specialization | The school facilitates me in bringing CPD learning into the real classroom | Teachers receive free in-service teacher education/training sponsored by the government | Teachers receive free pre-service teacher education sponsored by the government |

| 3 | Teachers' work patterns | Teachers are held accountable through various measures such as appraisals and test results | Teachers are held accountable through inspections and supervision | Teachers are involved in matters related to educational policy at the national/regional/school level | Teachers' views are sought on various educational issues, such as alternate solutions for teaching in emergencies like teaching in a pandemic situation |

| 4 | Teachers' employment, salaries, and benefits | Most of the teachers are employed on a permanent basis | Teachers enjoy job security | Teachers' salaries are comparable to those of other professions with similar qualification. | Teachers' salaries are linked to students' performance in exams |

| 5 | Other benefits | Sick leave with pay | Maternity/paternity leave | Special provisions for teaching from home such as internet connection and updated device | Fuel allowances |

| 6 | Teachers' work conditions | I have the freedom to determine how to teach according to professional standards without any interference | I can ask for improvements in the working conditions from the relevant authorities | I can ask for a raise in my salary if I believe I meet the criteria | I can ask for revisions in my conditions of employment from the relevant authorities |

Overall most- and least-occurring specific measures.

Table 8 presents interesting patterns. The findings illustrate how being professional and becoming professional intersect and intertwine. For example, in the being professional construct, teachers portrayed themselves as competent professionals who can modify teaching and curriculum to suit students' needs and the changing contexts with the help of various professional development opportunities. Teachers' portrayal connects well with a number of most-occurring measures. These are related to developing teachers' professional competencies such as arranging planned and organized professional development programs for them, providing them with avenues to bring their learning from continuous professional development to the classrooms, and making provisions for continuous professional development, which results in greater recognition in a particular skill or area of specialization. This resultantly connects to the findings relating to the professional capacities in the being professional construct as the most significant dimension of teachers' professional status. The relationship illustrated here is not conclusive, but the pattern is very obvious.

The findings also illustrate that, while teachers recognize the importance of professional development, they have limited opportunities for receiving grants for furthering their professional qualifications or for receiving free pre-service or in-service education. Teachers' work patterns suggest that they are mostly held accountable through various measures, but they are less involved in matters related to educational policy and planning, including matters related to teaching during the pandemic.

A similar pattern was observed in teachers' work conditions, where teachers had more decision-making freedom in some matters. For example, a higher percentage of teachers reported that they could determine their teaching methods and could also ask for improvement in the work conditions, but the percentage of teachers who could ask for a salary raise or change in their employment condition was small. Similarly, while most of the teachers were employed on a permanent basis, enjoyed job security, and had obtained a salary raise during the last 10 years, most of them were still not satisfied with their existing salaries and felt that their salaries were not comparable to salaries in other professions with similar qualifications.

7. Juxtaposition of being professional and becoming professional: discussion and implications

It is very clear from the analysis that teachers identify with being professional and they wish to be seen as professionals. The core of the “Professional Competencies in the Being Professional Construct of Teachers' Status” factor comprises teacher knowledge, teacher pedagogy, teacher engagement, and teacher learning and preparation (also for emergency situations). While teacher knowledge, teacher pedagogy, and teacher engagement define teacher professionalism, teacher learning and preparation call for professionalizing the profession. Teachers shared that key measures to facilitate their learning and preparation within the becoming professional construct comprise the provision of planned and organized professional development programs for teachers (such as workshops, short-duration training, etc.) and the provision of opportunities to bring learning in real classrooms for greater recognition in a particular skill or area of specialization. This is in accordance with Hargreaves's (2000) notion that, when teachers are being professional in terms of the professional standards, they follow their daily routine to produce quality work and wish to be seen as professionals (Hargreaves, 2000) in terms of their status, standing, regard, and levels of professional reward. This is easier said than accomplished, particularly in a country like Pakistan, where, as noted earlier, it has been generally reported that teaching has become the profession of the last resort for most educated young persons (Ministry of Education, 2009), despite efforts to raise the status of the profession by investing in improving teacher management, developing political will for teacher licensing and certification, increasing equity in teacher placement, improving the school environment, and investing in teacher development (Government of Pakistan, 2017, 2018). Experts often flip Hargreaves's (2000) notion to argue that if teachers wish to be seen as professionals in terms of their status and regard, they must always strive to be professionals in terms of practicing professional standards. They cite examples to illustrate the breadth of teachers' incapacities in relating with students, engaging students in learning, and promoting students' learning (Ministry of Education, 2009; Pre-service Teacher Education Program Pakistan/USAID, 2010). They argue that teachers need to engage in continuous learning and preparation for greater and demonstrable execution of professional standards at the classroom level to enhance their professional standing and their own sense of professionalism. Ignoring teachers' calls for being professional would kill and overturn even the most creatively designed professional development programs (Hargreaves, 2002; Rizvi, 2015).

The “Personal Empowerment in the Being Professional Construct of Teachers” Status factor calls for regarding teachers as capable professionals who have the capacity to influence and drive improvements in their own learning and in the learning of the children in their care. The personal construct highlighted in this study brings to the surface teachers' conceptualization of re-professionalizing the profession in a drive to enhance their status. Teachers' involvement in policy and planning at the school, provincial, or national level and teacher empowerment have emerged as two important components of this construct. Teachers shared that they can play an important role in policy and planning. The analysis of the measures taken to help teachers become professionals revealed that they are mostly held accountable through various measures, but they are less involved in matters related to educational policy and planning at the national, provincial, or regional level, including matters related to teaching during the pandemic. This means that a detached planning approach, which the literature has already highlighted as problematic (Furlong et al., 2000; Flores and Shiroma, 2003; Hall and Schulz, 2003), is still being practiced in Pakistan. It is dismal to note that nearly 50% of the teachers in the sample did not feel empowered to make changes even at the school level.

These findings contradict teachers' ideological beliefs, which are reflected through the core values emerging from the “Ideological Beliefs in the Being Professional Construct of Teachers' Status” factor, where they consider themselves ethical professionals who are responsible for building the moral and ethical character of students so that they become independent and responsible citizens of Pakistan. In his address at the first educational conference held in Pakistan soon after achieving independence in 1947, Quaid-e-Azam, Muhammad Ali Jinnah (Mujahid and Merchant, 2007) accorded an important responsibility and a prominent status to Pakistani teachers for building the character of future generations. This policy has continued since then, at least theoretically. Realistically, as the measures in Table 8 illustrate, the salaries of the teachers on whose shoulders lie the responsibility of building the character of future generations are not even comparable to those of other professions in Pakistan; teachers are expected to abide by ethical standards but cannot ask for revisions in their conditions of employment or alter their work environment for judicial execution of their ethical work practice.

While dilemmas abound and tensions persist in the way of professionalizing the teaching profession, the juxtaposition of the being professional and becoming professional constructs has also drawn attention to a number of possibilities for creating equitable, futuristic, and judicial teacher education programs. These are illustrated with the help of three key themes for preparing and recognizing teachers as professionals. The themes have emerged from the careful analysis of the three factors presented in Sections 5.1, 5.2, and 5.3, as well as the general and specific opportunities for enhancing teachers' professional status presented in the Results and Analysis of the Becoming Professional Construct section. A discussion of these themes culminates into specific implications for the relevant authorities in Pakistan, in particular, but it may also be relevant for educational authorities in related global contexts to make informed decisions for drawing meaningful and authentic connections between being professional and becoming professionals. Figure 5 illustrates this relationship. It is a progression from the initial framework to the informed framework, illustrating how the juxtaposition of the key factors of being professional and the key measures of becoming professionals generate key themes of recognizing teachers as professionals and enhancing their status.

Figure 5

Juxtaposition of being professional and becoming professional (informed framework).

7.1. Theme one: possibilities amid juxtaposition

The reciprocal relationship illustrated in juxtaposition is important for defining teachers' study programs. For example, the enhancement of teachers' professional status takes place when measures that contribute to defining teachers' status are also taken. Teachers, as professional beings, must understand children's needs and prepare them for the unforeseen future. This is only possible when teachers are also prepared for such roles and responsibilities.

In making an argument for teachers as activist professionals, Groundwater-Smith and Sachs (2002) called for thorough preparedness of teachers working at all levels. They argued that teacher education programs need to be based on the principles of critical pedagogy, preparing and enabling teachers to challenge the practices that are geared toward de-professionalizing the profession. Rigorous preparation, creative engagement, theory-driven practice, professional autonomy, and professional standards have been identified globally as the core of teacher professionalism and professionalization (Swann et al., 2010).

The findings strongly imply that policymakers and educational planners should focus on preparing and recognizing teachers as autonomous professionals capable of realizing more fully the professional standards, which they highlighted in this research, with the help of futuristic and judicious teacher preparation and development programs based on principles of inclusion and teacher empowerment (Korthagen, 2017; Cochran-Smith et al., 2022). If teachers continue to be treated as technicians with little or no control over their own development, then ambitious plans such as teacher licensing and accreditation will lose their true significance.

Planning of teacher education programs, which are detached from teachers' ideals, beliefs, and aspirations, may not produce any results no matter how progressive and forward-looking they are. The research presented a broad general overview of teachers' perceptions. This can serve as an authentic foundation for teacher training and development; however, since each individual is unique, there is also a need for more in-depth research that can bring to light teachers' viewpoints on their own professional growth and development.

7.2. Theme two: the balance in professionalizing the profession

The analysis of teachers' work patterns presented a misbalance in the measures taken for professionalizing the profession. Most of the teachers agreed to the fact that they are held accountable for their work through various measures such as appraisal, test results, inspection, and supervision. However, relatively small percentage of teachers expressed that they were trusted to use their professional judgment and expertise, that their views were sought on various educational issues, and that they were involved in matters related to educational policy. These findings suggest that there is a tilt in balance toward various accountability measures compelling teachers to fulfill their responsibilities. Measures that treat teachers as responsible professionals are less in practice when in fact findings illustrated that teachers consider themselves ethical professionals whose responsibility is to educate students for life. These findings clearly suggest that responsibility must precede and supersede accountability (Hargreaves and Shirley, 2009). Hargreaves and Shirley (2009) also cited the example of Finland, where teachers are held together by cultures of trust, cooperation, and responsibility and where teachers feel responsible for all the students they affect. An accountable and transparent teaching profession is important, but there must be other creative ways to achieve this to re-professionalize (Williamson and Morgan, 2009) the teaching profession. The teaching profession based on principles of democracy, trust, justice, and equity (Groundwater-Smith and Sachs, 2002) can counteract the inclination toward a centrally controlled teaching profession and can also open avenues for opportunities for education debates and practices.

Policymakers and educational leaders need to understand that finding a balance is a tall but necessary order. Students are diverse, but so are teachers. Teachers are expected to respect the cultural diversity of the students. This can only happen if the teachers' own diversity is appreciated and respected. It is imperative that the profession is able to attract and retain teachers who have the commitment and passion to improve the quality of teaching and learning in their contexts.

7.3. Theme three: extending the boundaries and broadening the vision

Teachers' professionalism and professionalization is, in fact, a global phenomenon of importance for all concerned. Many issues highlighted by Edwards (cited in Thompson, 2021) in the global report on the status of teachers are quite similar to the issues we discovered in this research. The report gathered perspectives from multiple countries and multiple organizations across the globe. In this respect, it would be fair to say that teachers' status has a universal connotation. Edwards (cited in Thompson, 2021) stated that teachers can no longer be isolated. If education authorities want to improve the quality of education, they need to listen to teachers. Karousiou et al. (2019) asserted that policymakers who seek the successful restructuring of education systems will unavoidably have to respect and support teachers' professional being.

There are implications for policymakers and educational managers to structure avenues of global dialogues among teachers from diverse national and international contexts so that they can learn from each other, work collaboratively toward resolving their issues, and uplift their professional status. These avenues can include but may not be limited to the formation of professional associations, membership in the existing associations, and strengthening of professional networks through various programs.

8. Limitations of the study

The limitations, such as respondents' non-responsiveness for some items and their tendency to agree with positive items inherent in the quantitative self-report survey design, were addressed by collecting a large amount of data from diverse participants in different school settings spread across various regions of Pakistan. Resource and time constraints influenced sampling decisions. For example, it was decided to collect data from at least two districts from each province, except for Balochistan where only one district was selected due to its wide terrain.

The initial plan of collecting data from Deeni Madaris could not be materialized due to the COVID-19 pandemic situation. Some Deeni Madaris appeared interested at first. However, following the COVID-19 situation, they lost interest.

9. Conclusion

The research, guided by two broad research questions, provided a holistic understanding of teachers' notions of being professional and how these notions can lead to an informed program of enhancing teachers' professional status and standing. When teachers are being professional, they also need to be recognized as professionals. It was important to use empirical analysis pragmatically to reach out to a diverse group of teachers and ensure maximum participation from various regions of Pakistan using self-report data. A large number of participating teachers helped us counter the inherent bias in self-reports. However, they could not provide elaborations, which were required in some responses. Nevertheless, teachers openly and confidently shared their conceptions about their professional selves, their ideological selves, and their personal selves as capable professionals who can use their personal agency to define and lead their professional status. However, first, they need to be equipped with knowledge, confidence, and skills to make informed decisions and to improve the lives of the children under their care. If teachers are being empowered, they also need emotional strength, trust, and economic stability.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Funding

This research (Project ID: 191012IED) has been funded by the University Research Council (URC) on the recommendation of the Grants Review Committee (GRC).

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the participating teachers, research assistants, AKU-IED students, the AKU-URC, the AKU-Ethics Review Committee, the National Bioethics Committee, Pakistan, the school authorities, and the AKU-IED leadership.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

AliS.AhmedA. (2022). Teaching License in Pakistan: A White Paper 2022.Karachi: AKU-IED.

2

AslamM.MalikR.RawalS.RoseP.VignolesA. (2019). Do government schools improve learning for poor students? Evidence from rural Pakistan. Oxford Rev. of Edu.45, 802–824. 10.1080/03054985.2019.1637726

3

BrymanA.CramerD. (2005). Quantitative Data Analysis with SPSS 12 and 13. London: Routledge.

4

BurnsD.Darling-HammondL. (2014). Teaching Around the World: What Can TALIS Tell Us?Stanford: SCOPE.

5

ChalariM.OnyefuluC.FasoyiroO. (2023). Teacher educators' perceptions of practices and issues affecting initial teacher education programmes in Jamaica, Greece and Nigeria. Power Edu.15, 102–121. 10.1177/17577438221102683

6

ClandininD. J.HuberJ.HuberM.MurphyM. S.OrrA. M.PearceM.et al. (2006). Composing Diverse Identities. London: Routledge.

7

Cochran-SmithM.CraigC. J.Orland-BarakL.ColeC.Hill-JacksonV. (2022). Agents, agency and teacher education. J. Teach. Educ. 73, 445–448. 10.1177/00224871221123724

8

ConnellyF. M.ClandininD. J. (1999). Shaping a Professional Identity: Stories of Educational Practice.Ontario: Teachers College.

9

ConwayP. (2001). Anticipatory reflection while learning to teach: from a temporally truncated to a temporally distributed model of reflection in teacher education. Teach. Teacher Edu.40, 89–106. 10.1016/S0742-051X(00)00040-8

10

CraigC. (1999). “Life on the professional knowledge landscape: living the principal as rebel image,” in Shaping a Professional Identity: Stories of Educational Practice. eds ConnellyF. M.ClandininD. J. (Ontario: Teachers College), 150-167.

11

Darling-HammondL. (2017). Teacher education around the world: what can we learn from international practice?Eur. J. Teach. Edu.40, 291–309. 10.1080/02620171315399

12

DaveyR. (2013). The Professional Identity of Teacher Educators: Career on the Cusp?London: Routledge.

13

DayC. (2004). A Passion for Teaching. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

14

DayC.ElliottB.KingtonA. (2005). Reform, standards and teacher identity: challenges of sustaining commitment. Teach. Teach. Edu.21, 563–577. 10.1016/j.tate.2005.03001

15

DoltonP.MarcenaroO.VriesD. e.SheR. D. (2018). Global Teacher Status Index 2018.London: Varkey Foundation.

16

FloresM. A.ShiromaE. (2003). Teacher professionalization and professionalism in Portugal and Brazil: what do the policy documents tell?J. Edu. Teach.29, 5–18. 10.1080/0260747022000057972

17

FurlongJ.BartonL.MilesS.WhitingC.WhittyG. (2000). Teacher Education in Transition. Buckingham: Open University.

18

Government of Pakistan (2017). National Education Policy 2017. Available online at: https://pbit.punjab.gov.pk/system/files/National%20Educaton%20Policy%202017.pdf (accessed December 28, 2022).

19

Government of Pakistan (2018). National Education Policy Framework 2018. Available online at: https://aserpakistan.org/document/2018/National_Eductaion_Policy_Framework_2018_Final.pdf (accessed December 28, 2022).

20

Groundwater-SmithS.SachsJ. (2002). The activist professional and the reinstatement of trust. Camb. J. Edu.32, 341–358. 10.1080/0305764022000024195

21

HallC.SchulzR. (2003). Tensions in teaching and teacher education: professionalism and professionalisation in England and Canada. Compare33, 369–383. 10.1080/03057920302588

22

HargreavesA. (2000). Four ages of professionalism and professional learning. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract.6, 151–182. 10.1080/713698714

23

HargreavesA. (2002). “Teaching in a box: emotional geographies of teaching,” in Developing Teachers and Teaching Practice, eds SugrueC.DayC. (London: Routledge/Falmer), 3-25.

24

HargreavesA.ShirleyD. (2009). The Fourth Way: The Inspiring Future for Educational Change.Thousand Oaks: Corwin.

25

HargreavesL.CunninghamM.HansenA.McIntyreD.OliverC. (2006). The Status of Teachers and the Teaching Profession: Views From Inside and Outside the Profession:Cambridge: University of Cambridge.

26

Hasan A. J. (2007). Education in Pakistan: A White Paper Revised. Available online at: http://planipolis.iiep.unesco.org/upload/Pakistan/Pakistan%20National%20Education%20Policy%20Review%~20WhitePaper.pdf (accessed February 10, 2023).

27

HerrmannR. W. (1972). Classroom status and teacher approval—Study of children's perceptions. J. Exp. Edu.41, 32–39.

28

Higher Education Commission (HEC) (2012). Curriculum of Education. Available online at: http://www.hec.gov.pk/InsideHEC/Divisions/AECA/CurriculumRevision/Documents/Educati/on/2012.pdf (accessed January 22, 2023).

29

HoodbhoyP. (Ed.). (1998). Education and the State: Fifty Years of Pakistan. Karachi: Oxford University.

30

HoyleE. (2001). Teaching: prestige, status and esteem. Edu. Manag. Admin.29, 139–152. 10.1177/0263211X010292001

31

IshaqR. (2019). Why Are Schools Failing to Educate? The News, December 15. Available online at: https://www.thenews.com.pk/tns/detail/582964-why-are-schools-failing-to-educate (accessed November 20, 2023).

32

KarousiouC.HajisoteriouC.AngelidesP. (2019). Teachers' professional identity in super-diverse school settings: teachers as agents of intercultural education. Teach. Teach.25, 240–258. 10.1080/13540602.2018.1544121

33

KelchtermansG. (2009). Who I am in how I teach is the message: self-understanding, vulnerability and reflection. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract.15, 257–272. 10.1080/13540600902875332

34

KizilbashH. H. (1998). “Teaching teacher to teach,” in Education and State: Fifty Years of Pakistan, ed HoodbhoyP. (Karachi: Oxford University), 102-135.

35

KorthagenF. (2017). Inconvenient truths about teacher learning: toward professional development. Teach. Teach. Theory Pract.23, 387–405. 10.1080/13540602.2016.1211523

36