- Pomona College, Claremont, CA, United States

No one enjoys grading, neither instructors nor students. The idea is that grades provide the required incentive to learn and act as an “objective” form of evaluation. This view is especially prevalent in STEM, where practitioners pride themselves in quantitative and objective measurements. However, the science of learning tells us that grades and ranking increase competition and stress, pushing learners to engage in tasks regardless of their effectiveness. Grades have been shown to suppress interest in learning, incentivize engagement in easier tasks, and produce shallower thinking. If wanting to learn is something students and faculty can agree on, how do we get there without grading? From psychology research, we know that feedback, separated from grades, along with opportunities to reattempt work without negative consequence, are powerful drivers of the intrinsic motivation to learn. In fact, feedback loops—trying something new, getting feedback, and making changes based on feedback - are a known developmental pathway to authentic learning. In this article, I describe an experiment with a form of ungrading that involves students in the co-creation of self-assessment criteria. The goal is to create learning feedback loops, incentivize learning for learning’s sake, and give students some agency in the process of evaluation. This was conducted in an upper division Immunology course at a small liberal arts college. This paper outlines an iterative and dialogical process between students and instructional staff to craft a holistic set of criteria for the evaluation of learning. These criteria became the foundation for regular one-on-one conversations with students and a means to track progress over the semester. End-of-semester student feedback was overwhelmingly positive, citing increased motivation to learn, lower levels of anxiety, a less competitive environment, and growth as a learner. Among the few disadvantages cited were anxieties from grade ambiguity, fears about the process, and extra time, especially for the instructor. This paper highlights the ways in which this system aligns with psychosocial theories of learning, fostering an intrinsic motivation to learn utilizing principles of critical pedagogy and students as partners. It concludes with lessons learned from both the student and instructor viewpoint.

Introduction: background and rationale for the educational innovation

Several years ago, I had a personal experience that changed the way I think about the assessment of student learning. Two students arrived for a small group office hour. While pulling notebooks out of backpacks they begin chatting about an upcoming exam in another STEM course. One student asked the other if they were ready for the exam, scheduled for the next day. The second student replied in the affirmative and shared how extensively they had been studying. This student then added, with complete sincerity, “I really like this topic. At some point I’d like to take the time to actually learn this stuff.” A feeling of déjà vu overcame me. I could remember telling myself the same thing in college—just get through this exam and you can worry about understanding the material later.

This anecdote inspired me to question my evaluation and grading practices, and whether these undermine the learning goals I had for my students. A review of the literature introduced me to the science behind how learning works and a range of alternative grading schemes, leading to a gradual withdraw from grades in my classes. After a few semesters of decentering grades, I wondered if replacing grades in favor of feedback and opportunities for revision would help students develop greater internal motivation and more self-accountability for learning? Second, could this process be used to encourage students to develop self-awareness as learners, helping them to shift their behavior toward pro-learning behaviors? Finally, could this divorce from grades decrease anxiety for all involved, especially around the assessment process?

With these questions in mind, I taught the next semester’s class without grades or scores attached to any feedback I provided to my students (an ungraded class, which I define shortly). My institution still required a letter grade at the end of the semester, delaying but not eliminating the need to translate a semester’s worth of work into a letter grade. While the students provided me with self-reflections, I felt increasingly uncomfortable being the ultimate decision-maker about final grades. Likewise, I was concerned that this short-circuited the need for students to assume responsibility for their own learning. This led to my final research question and the central intervention presented in this paper. Can we alleviate some the power differential and ease the process of establishing final grades in an ungraded class by making the process more transparent and providing the students with more agency? This was done by engaging students, early in the semester, in co-creation of a set of criteria that they could use to regularly evaluate their own learning progress.

These four research questions motivate the work presented in this study, investigating implementation of a co-created rubric for self-evaluation in an ungraded class:

1. Would this improve motivation, self-accountability, and student ownership over their learning?

2. Does this foster greater self-awareness as learners, promoting selection of adaptive learning behaviors?

3. Will greater transparency and agency in the evaluation process reduce student anxiety?

4. Can this build greater trust in assessment and facilitate self-assignment of grades at the end of the semester?

Theoretical frameworks

Below I present a very brief review of some of the theoretical principles that underlie the structure of the learning environment and evaluation procedure presented in this paper. In particular, I discuss alternative grading schemes, the science behind motivation and learning, as well as critical pedagogy and power-sharing with students.

Alternative grading schemes

The idea of alternative grading, which has gained momentum in the last decade, was born from a desire to remove the stigma, mystery, and bias of grades from the practice of learning. Examples include standards-based, labor-based, mastery, and contract grading (for a glossary of these and others, see1). In essence, these systems associate a set of learning goals, rubrics, or actions with a grade. While an improvement on traditional grading practices, these schemes can still struggle to address some of the underlying issues with grades—learning motivation and the value of making mistakes—two key tenants of how people naturally learn.

Alfie Kohn’s seminal article, From Degrading to De-grading, lays out the underlying arguments for removing grades from the calculus of learning (Kohn, 1999). In that article, he summarizes research showing three major unintended outcomes of an emphasis on grades. Grades tend to: reduce student interest in learning for learning’s sake; decrease student preference for challenging tasks; and reduce the quality of student thinking. Kohn and others describe additional impacts of grades that will be important for this discussion. For example, grades can erode relationships between the instructor and student, as well as collaboration between students (Kohn, 1999). Despite common wisdom, grades are a flawed and biased means to assess actual learning, with no significant correlation to future outcomes (Samson et al., 1984). Finally, research suggests that grades may incentivize cutting corners and can result in more cheating (Anderman and Murdock, 2007).

The national conversation about moving away from a focus on grades in higher education has progressed in several stages. In their paper entitled “Teaching More by Grading less (or Differently),” Schinske and Tanner lay out the scholarly argument for why grades should be minor players in the learning process (Schinske and Tanner, 2014). Without abandoning grades completely, they argue for an emphasis on recognizing effort, persistence, and self or peer-reflection, de-emphasizing grades. This and other literature that presented the benefits of de-emphasizing grades (McMorran et al., 2017; Schwab et al., 2018; McMorran and Ragupathi, 2020) fed a movement that coalesced around the concept of ungrading, or removing grades from the learning environment.

In the past decade, a multitude of articles, Blogs, and Tweets have shared examples of the range of ungrading-inspired practices. Jesse Stommel’s blog series on ungrading,2 now published as a compilation (Stommel, 2023) reviews many of Kohn’s original arguments and takes the reader from the mechanics of how to ungrade to questioning the wisdom of the term itself. In 2020, an authoritative and wide-ranging collection on ungrading appeared in book form, edited by Blum (2020). This includes examples applied to a range of disciplines and education levels, from middle-school classrooms to college STEM courses and writing-intensive seminars. While specific ungrading practices vary, all formats appear to adhere to the following three principles: regular, substantive, and individualized feedback on student work, without a grade or score; opportunities to revise and resubmit work based on this feedback; and an expectation that students regularly self-evaluate their own learning. The latter often includes semi-regular meetings with the instructor to discuss individual student growth.

The role of motivation and failure in learning

The idea behind grades was that they would provide students with incentive or motivation to learn, as well as provide a more “objective” form of evaluation than mere feedback. This view is especially prevalent in STEM, where practitioners pride themselves in quantitative and objective measurements of the world. However, from the science on learning, we see that grades provide a form of external incentive or motivation, bypassing and subverting crucial internal motivators, the more powerful drivers of our actions as humans. This theory has been tested empirically in seminal work by Ruth Butler. Butler and colleagues studied motivation in 5th and 6th grade children (Butler and Nisan, 1986; Butler, 1988). They investigated the outcome of evaluating student work by combining feedback with grades, as compared to supplying each of these alone. She and others have shown something I think we all know intuitively—students focus on the number or letter assigned to their work (ego-centric feedback), failing to pay much attention to accompanying written critiques and suggestions (task-based feedback). However, when only written feedback was provided without a grade or score, Butler found that students were more likely to act on this information, improving their future performance. Since then, others have found similar negative impacts of grades on the intrinsic motivation to learn (Kitchen et al., 2006; Pulfrey et al., 2011; Grant and Green, 2013).

Joshua Eyler’s book entitled “How Humans Learn” lays out the science behind teaching practices that drive intrinsic motivation (Eyler, 2018). In it, Eyler points out the importance of curiosity, social belonging, emotion, authenticity, and failure in the natural learning process. Lovett and colleagues similarly present 8 evidence-based principles behind effective learning, several of which touch on motivation and room for failure (Lovett et al., 2023). In particular, they point out that while humans are naturally curious, students need to be motivated to learn. When aiming for motivation, value and self-determination are crucial to the learner. Likewise, clear expectations, targeted feedback, flexibility, and opportunities for reflection provide an environment conducive to learning. They go on to describe the importance of a natural feedback loop for learning. This includes frequent, spaced out, low stakes practice opportunities; real-time feedback, including from peers; expectations that students reflect on how they are using this feedback to improve; and opportunities to re-attempt work using insights gained from this feedback and self-reflection.

Power dynamics in the classroom

Sidelining grades can be a rewarding and mind-opening enterprise. And yet, as a stand-alone practice, it runs the risk of highlighting rather than remediating the imbalance of power present in most teaching and learning environments. For full affect, many elements of the standard classroom environment and teacher-student dynamic need reimagining and humanizing. This requires stepping outside common patterns of power in the classroom. For example, placing more decisions in the hands of the learner and conversations with students about the “whys” behind teaching decisions could help to build trust and foster a more collaborative learning space. The frameworks and literature I found most helpful for thinking about power-sharing include principles from critical pedagogy (Hooks, 1994; Freire, 1998, 2000) and initiatives focused on engaging students as partners in learning (Shor, 1996; Healey and Healey, 2019; Bovill, 2020; Mercer-Mapstone, 2020), as briefly outlined below.

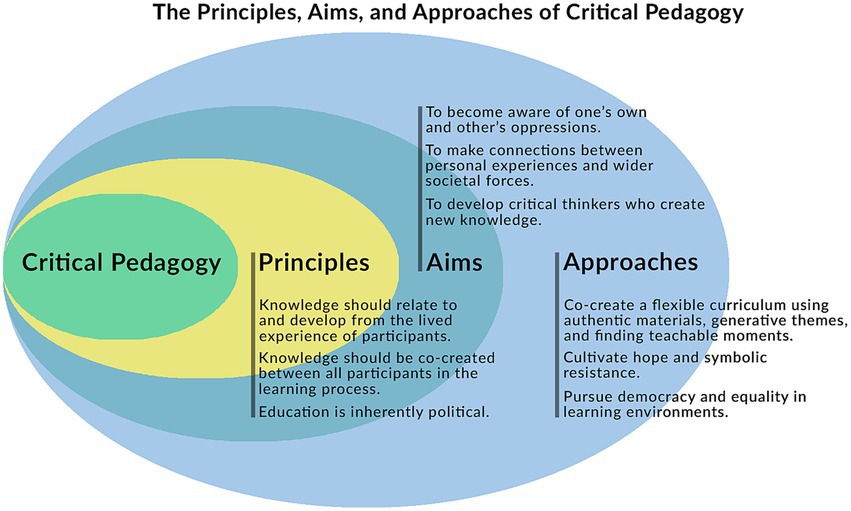

The Brazilian educator and philosopher Paulo Freire is widely viewed as the father of the field of critical pedagogy (Freire, 1998, 2000). This philosophy applies a critical theory lens to teaching and learning, questioning the power, practices, and social structures that influence learning and its participants. It asks us to critique everything associated with learning, creating a more democratic and equitable learning environment. Freire famously compared traditional learning systems to a banking model, where students are seen as empty vessels to be filled with the deposited knowledge of learned teachers. Critical pedagogy posits that all real learning occurs reciprocally—for both the student and instructor—and is specific to the lived experience of the participants, intimately helping to release them from sometimes invisible oppressive forces (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Principles, aims, and approaches of critical pedagogy. From, Rollins School of Public Health (www.SPH.emory.edu, adapted from Smith and Seal, 2021).

Freire’s view of students as partners in learning comes to life in Ira Shor’s recounting of the semester in which he turned over control of his course to student enrollees (Shor, 1996). In that course on Utopia, Professor Shor experiments with greater and greater levels of student agency to question and reshape the standard policies and practices of their writing course. It cleverly illustrates both this slippery slope (e.g., why not question the requirement for attendance?) as well as the ways in which this process facilitates learning for all parties (e.g., the instructor taking notes on student feedback during the After-class-group). These power-sharing arrangements with students, collaboratively peeking under the hood of higher education, open up the endeavor of teaching to critique and invite students to help build something better. Practices like this represent a fairly revolutionary culture shift in academia, especially when grades enter the equation. As bell hooks so aptly states in her book, Teaching to Transgress (Hooks, 1994):

“I celebrate teaching that enables transgressions-a movement against and beyond boundaries. It is that movement which makes education the practice of freedom….That brings us back to grades. Many professors are afraid of allowing non directed thought in the classroom for fear that deviation from a set agenda will interfere with the grading process. A more flexible grading process must go hand in hand with a transformed classroom.”

Students as partners in learning

This leads naturally to the idea of engaging the learner in the process of learning, moving the student from a receptive into an active role. A growing body of literature presents findings on what occurs when instructors engage students as partners (SaP) in the learning process in substantive ways (Healey and Healey, 2019). This can range from selecting course content, to crafting activities and designing assessment criteria (Mercer-Mapstone et al., 2017). While some examples of this applied to assessment ask individual students or small groups to participate in some decision-making or involve students in the creation of rubrics for an individual assignment (Morton et al., 2021), others employ a whole class approach (Bovill, 2020), as outlined in this paper. The latter welcomes learners into the practice of summative evaluation, providing greater student agency and, by corollary, greater intrinsic motivation (Bovill, 2020). Placing students in positions of greater power also helps to create a more inclusive and equitable learning environment, as all viewpoints and the diversity of life experiences can be represented (Mercer-Mapstone, 2020). Finally, inviting students into the decisions made in crafting a teaching space demystifies the process of learning and can open the door to greater awareness about and trust in the process (Fraile et al., 2017).

Learning environment and methods

Campus setting and participants

Pomona College is a residential, small liberal arts college in Southern CA, 35 miles east of downtown Los Angeles. As part of a consortium of undergraduate and graduate institutions (Claremont Colleges), Pomona is one of the 5 undergraduate-only institutions in the consortium (along with Scripps, Pitzer, Claremont McKenna, and Harvey Mudd). Pomona College enrolls approximately 1700 students in an average year, with matriculants from over 40 states and 30 nations. With a faculty of approximately 200, Pomona boosts roughly an 8:1 student/faculty ratio. Pomona College is ranked as one of the top small colleges in terms of diversity of the student body; in the class of 2026, 61% are domestic students of color, 14% are international, and 23% are first-generation college students.

The course in question, Immunology (Biology 160), is an upper division elective offered to students who have completed at least two introductory courses in Biology; Genetics and Cell Biology. Typical enrollees are majoring in Biology, Molecular Biology, Neuroscience, or Public Policy Analysis (with a STEM field concentration). Students with an interest in medicine, public health, and/or biomedical research are common in this course. In an average year the course enrolls 20–24 students, mostly juniors and seniors, many with moderate experience beyond introductory college STEM courses. I have been teaching this course at Pomona College, using a traditional teaching and grading format, for 7 of the past 10 years. I taught a similar course at my former institution (Mount Holyoke College) for the previous 12 years. Therefore, I have over 20 years of experience teaching undergraduate Immunology, most of that time using a fairly traditional grading system.

Learning objectives and class guidelines

The learning goals for this course are standard for an undergraduate Immunology course (see Supplementary Table 1 for a full list of objectives). Much of the course description, beyond the (un)grading scheme presented in this paper, has been standard practice for the majority of my over two decades teaching the course. This topic is still relatively rare for undergraduates, especially at small colleges. With this in mind, I began including a second, “translated,” version of the learning objectives approximately 5 years ago, written in laymen’s terms for the typical novice undergraduate student (see Supplementary Table 1). I believe this helps to humanize the course content, placing the topics within a set of recognizable and socially interesting real-world contexts from day one.

This course is highly interactive and requires some student–student collaboration. Therefore, we always spend part of the first week drafting a set of discussion norms and community guidelines. This helps to set the tone for the type of collegial and inclusive environment I expect. It also allows students to codify what they want to see in order to feel safe opening up to peers and the instructor. We revisit our guidelines at least once in the middle of the semester to ensure we are adhering to our own norms (see Supplementary Table 2 for the Immunology, 2022 Community Guidelines).

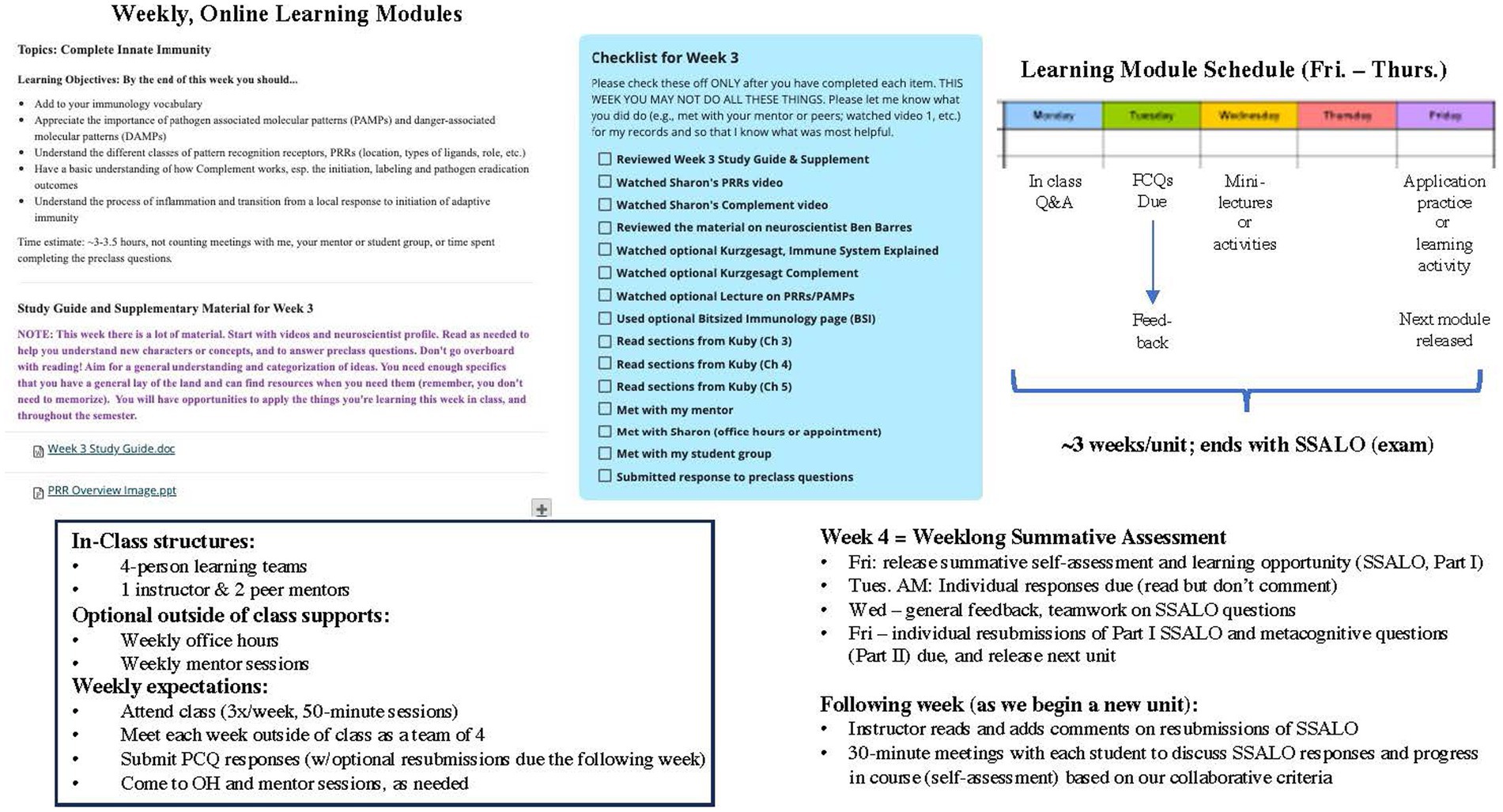

Course structure and pedagogical format

Several pedagogical elements existed in earlier iterations of this course, prior to the introduction of ungrading (see Figure 2 for a schematic illustration). For instance, this course has always been high-structure and taught with a flipped design, using just-in-time teaching (JITT) practices (Novak, 2011) which requires regular pre-class work. In the past 5 years, I have moved from primarily textbook reading to an online format with more diversity of information formats (videos, podcasts, readings, etc.). Students have some flexibility in when they engage with these weekly online learning modules and submit responses to preclass questions (PCQs). Weekly in-class discussions and problem-solving sessions with peers, plus restricted timing of instructor feedback on preclass assignments, helps provide encouragement to keep up with the work but does not penalize students for occasional late or missing assignments. Finally, I employ active learning in the classroom whenever possible, to help students uncover misconceptions and solidify concepts.

Figure 2. Schematic representation of course structure. Immunology (Biology 160), Fall 2022, Pomona College.

For the past 5 years, students have been assigned to small peer teams that work collaboratively throughout the semester in a learning community, inside and outside of class. Rather than traditional exams, evaluation of learning involves a set of monthly literature-based questions, called Summative Self-assessments and Learning Opportunities (SSLOs). With growth in mind, students can resubmit responses to weekly questions and SSLOs after meeting with their student team and/or with me. Finally, relatedness and belonging are incorporated by connecting the work to real world questions and communities, with a heavy reliance on teamwork. The team-based learning and opportunities to resubmit work help build and enforce trust and respect—between students and between the students and the instructional team.

The addition of structured ungrading

Fall of 2021 was the first time I fully incorporated ungrading into my Immunology course. While the experience was generally positive, I did receive valuable feedback from the students in that course regarding this experiment in alternative assessment. Many of these centered around discomfort over self-reflection and establishing end of semester grades. At least one student critique I vividly recall was that after a semester singing the praises of no grades, asking students to tell me what grade they deserved at the end of the semester felt like a bait and switch maneuver. In aggregate, student thoughts around ungrading coalesced around the following themes:

• Grading, and especially self-grading, is hard and uncomfortable.

• Students wished they knew what characteristics to look for in assigning a “good” grade.

• One-on-one meetings with the professor were valuable learning opportunities and also intimidating.

• Lack of a score could lead some toward perfectionism, never knowing what was good enough.

• Personal and quick feedback (without judgment) was easier to trust and immediately incorporate.

We debated possible ideas for how to improve the ungrading experience and make self-evaluation a fairer, more transparent, and less stressful process. In the end, co-creating guidelines for self-assessment was what we settled on. Ideally, this would happen early in the semester and would be specific to a particular course and set of students. These guidelines would help students prepare for self-assessment of their learning and help them justify their evaluation in one-on-one meetings with the instructor. Based on these objectives and my own reflections on the semester, I made the following changes to the Fall 2022 Immunology course:

1. Regular, individual feedback with room for growth: I provided weekly, individualized feedback for all online preclass assignments (but no grade), with the option to resubmit answers up to a level of mastery.

2. Self-reflection and metacognition: After each summative learning assessment (3 in total), students responded to a set of metacognitive questions about their study habits, preparation for the assessment, achievements in the course to date, and remaining opportunities for growth (“Part II” of each SSLO).

3. Ungrading and self-evaluation: I held individual, 30-min meetings with students after each SSLO to talk about their responses, progress in the course, and self-evaluation of learning to date.

4. Intrinsic motivation: Each student set at least one personal learning goal related to the course material, which we also discussed at our individual meetings.

5. Power-sharing and SaPs: I set aside time early in the semester to engage in co-creation of a set of guidelines related to how students would self-evaluate and justify their learning (see results).

Student feedback and analysis

Each student in this course provided written and oral feedback at least three times during the semester; when they answered a set of metacognitive and self-evaluation questions as a part of Part II for each SSLO and during our individual, 30-min meetings after each assessment. For the last of these self-reflections, students answered additional metacognitive questions related to teamwork, the course structure, ungrading/self-assessment, plus their own personal goals and accomplishments (see Supplementary Table 3 for all metacognitive questions). In addition, students completed anonymous end-of-the semester written evaluations (in-class), with some questions specifically addressing the structure of the course and format for assessment. For the questions about ungrading and collaborative creation of the assessment rubric, I conducted both a semi-quantitative and a qualitative analysis of responses. In the results, I outline the process of creating and using the self-assessment rubric, student impressions of the advantages and disadvantages of this form of ungrading, as well some themes that emerged from the analysis of student feedback in aggregate.

Results

Co-creation of a self-assessment rubric

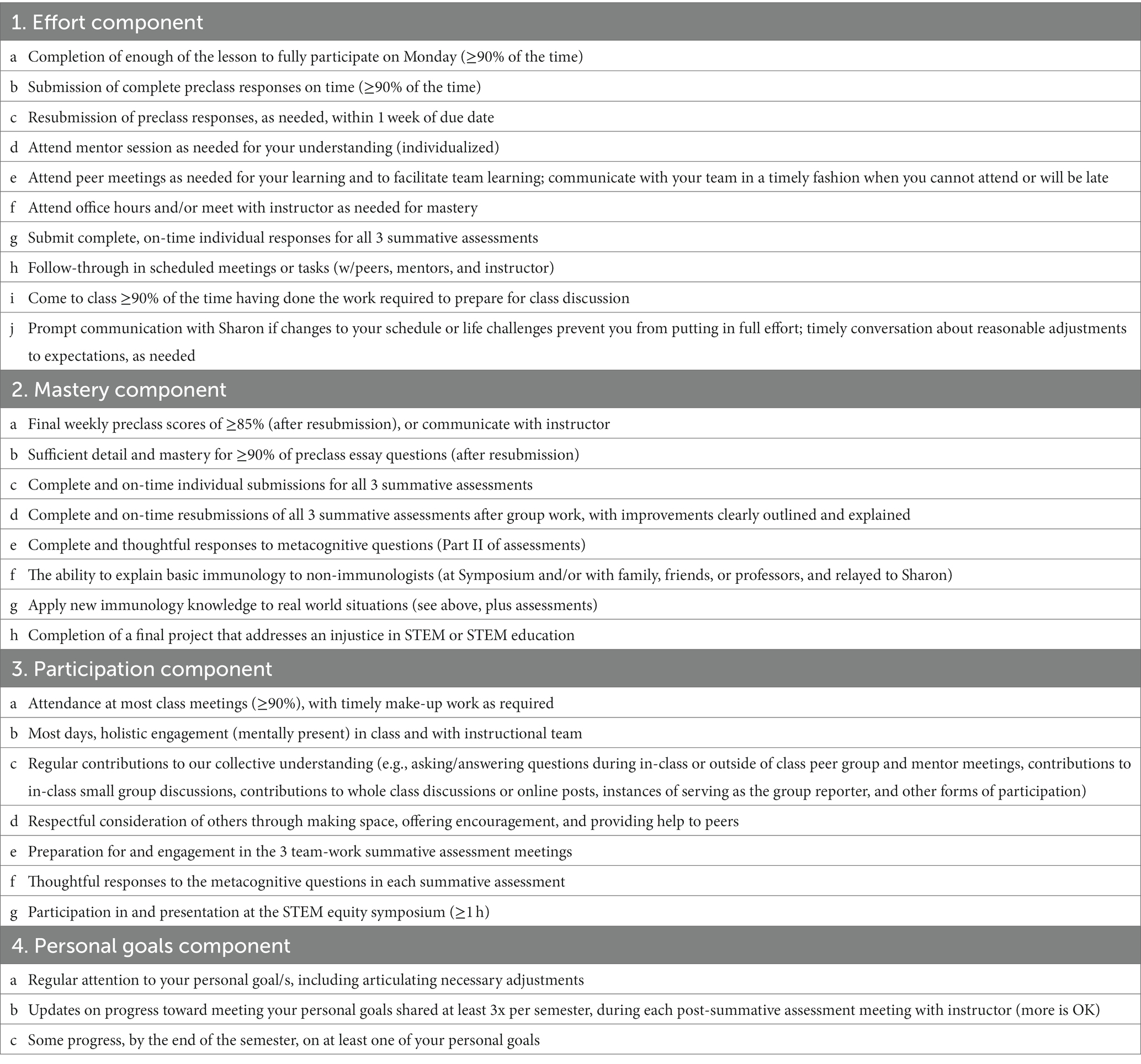

One week into the Fall 2022 semester, after students had explored the course structure and settled into a rhythm, I set aside time for a discussion about the self-assessment guidelines we wanted as a class. It felt important that this process begin in a safe space, separate from undue instructor influence. For this reason, the two peer mentors first facilitated small group discussions outside of class, during mentor session. These mentors were students from my Fall 2021 ungraded Immunology course—ideal people to launch this process. The mentors shared a self-evaluation framework with me, based on their discussion with students. This original framework had three main categories—effort, mastery, and participation—along with a few specific examples in each category.

During the next class period, we worked as a class (small group and whole class discussions) to refine these criteria. In the process, we added a 4th category, personal goals, and fleshed out additional details in each category. For example, one student asked, “what constitutes completion of enough of the lesson?” After some discussion, we settled on 90% as an agreed upon cut off. Likewise, students asked for more detail about how many preclass question sets were OK to miss or to hand in late, and how many class meetings could be missed without consequence. This led to a discussion about the purpose of preclass lessons and in-class work. There was student consensus that “on time” submissions were important for effective in-class group work the next day and that having all of the group present for most of these and other class meetings was crucial, but that everyone deserved at least one instance of life gets in the way. We also tried to build in exceptions to each rule, with a general philosophy that each student take sufficient responsibility for their own learning and contributions to the group, such that they eventually found a way to catch up with the material and could continue to contribute to learning within the group.

We continued to work online for approximately one more week, adding comments to a shared google doc. Before the first summative assessment, we settled on a final version of the criteria that all groups agreed would be our rubric for self-assessment for the semester (Table 1).

Self-assessment in action

The above rubric was used by students at three points in the semester, after each of the summative self-assessments and learning opportunities (SSLOs). Part I included three, multi-part, real world synthesis questions related to the material in that section of the course. After submitting individual responses to these questions, students worked on the questions again, in-class, in their peer teams, learning from one another. Each student then submitted a revised set of answers (Part II), including how their understanding had evolved since the first response. Part II also included a new set of metacognitive questions (see Supplementary Table 3) asking students to think about their learning process and to evaluate their effort, mastery of material, participation in the class, and progress on personal goals, using the above rubric as a guide. In addition to their written responses, I took notes during our one-on-one conversations. Thus, feedback on the process of self-assessment was collected from all students at multiple points in the semester and in multiple formats.

While the depth and detail of student-reflections varied, most took this process very seriously and provided specific examples under each of the above four categories in the rubric. When this did not happen in writing, we would discuss specifics in person. Both the written and oral feedback revealed many instances of student effort and participation that I as the instructor am commonly blind to and allowed us to discuss the importance of these unseen roles. Examples included students who instigated and organized all their groups’ outside of class meetings, individuals who reached out to missing members of their team to offer help, and those who provided peer instruction for concepts that others had yet to master. Likewise, we discussed progress on personal goals. This was a more individualized and ambiguous process, which led to constructive suggestions for improvements to setting and achieving personal goals (see discussion).

Student feedback

The following question asking students to evaluation ungrading was included among the metacognitive prompts in Part II of the final SSLO:

Based on your experiences this semester, what do you see as the advantages and disadvantages of ungrading, using the self-assessment rubric we created this year? If possible, give me some examples of each. Do you feel like the advantages out-weight the disadvantages, or not, and why?

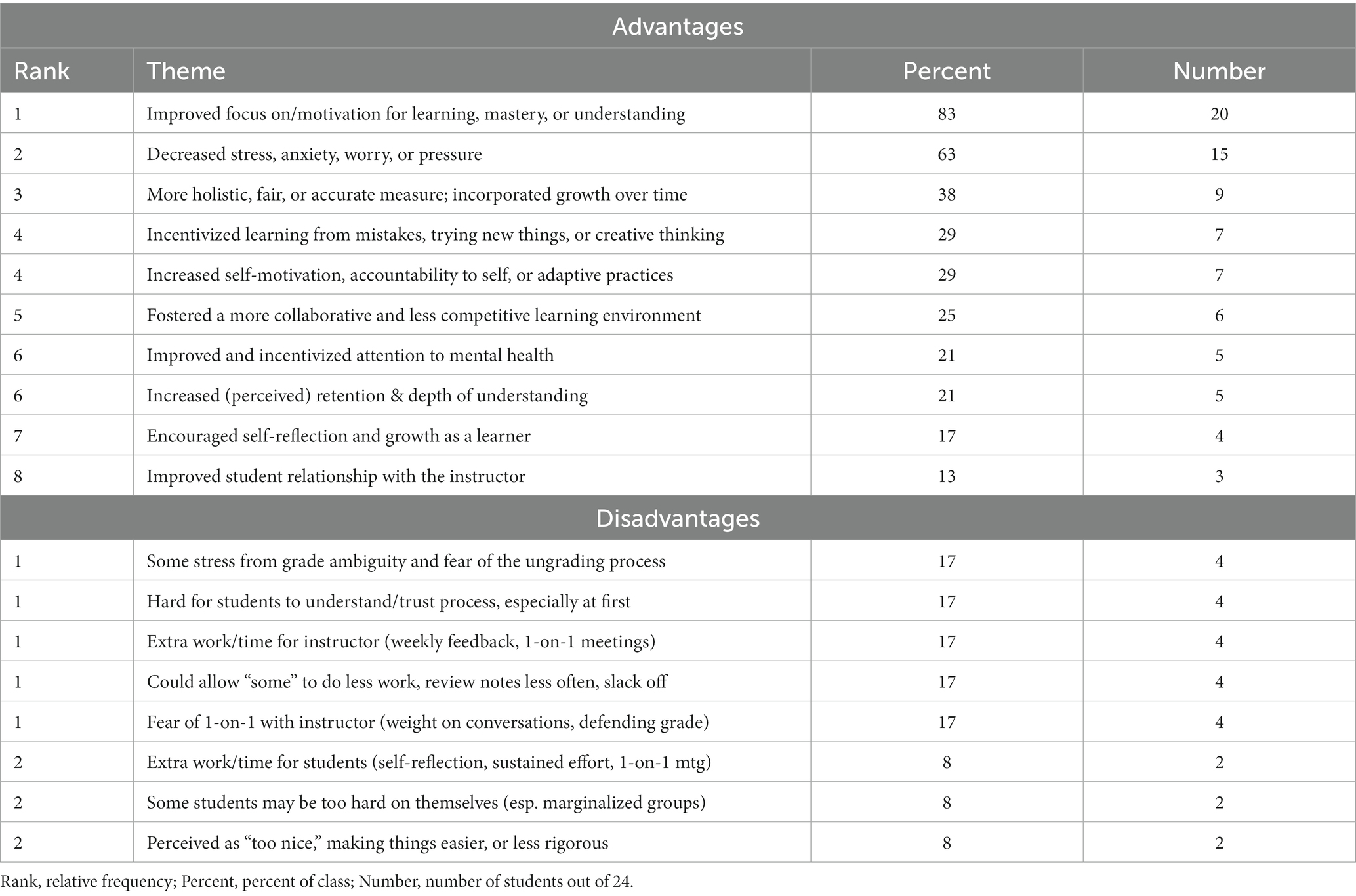

A semi-quantitative and qualitative analysis of responses to this question was conducted. Table 2 displays the major themes or categories of feedback shared by students, ranked by frequency of occurrence, and includes the percentage and raw number of students who shared this view.

Seventy-one percent of students (17/24) said that the advantages of ungrading in this class, using our co-created rubric for self-evaluation, outweighed any disadvantages. While most students included some examples of disadvantages, they presented significantly more examples and greater specificity around the assets of this self-reflection system. Two students were more equivocal, uncertain of the weighing, and the remainder (5/21; ~21%) gave examples of both but without a conclusion on weight. None said the disadvantages exceeded the advantages. Interestingly, many disadvantages were described as hypotheticals rather than personal experiences (e.g., “some students might feel that [blank] is a disadvantage”). And only a small minority of students noted disadvantages without caveat or third person reference. On balance, students had overwhelmingly positive things to say about learning in this context. As one student summarized:

“I think the advantages of ungrading include:

• Reduced pressure in mastering all of the material at once

• Cramming and forgetting to study does not work

• Builds sustainable study skills (e.g., spreading out your workload, planning ahead, taking thoughtful notes)

• Builds relationships with peers and the instructor through multiple submissions and consistent check-ins

• Encourages reflection/metacognition during the learning process”

In addition to the above question about ungrading in this course, students also responded to anonymous end-of-semester evaluations. These contained the following question about assessment:

How well did you understand the instructor’s criteria for assessing assignments, performances, etc. in this course? What instructions, discussions, handouts, or activities helped clarify this for you? Is there anything that would have helped make the criteria clearer for you?

These anonymous course evaluations were completed by 21/24 students (87.5%). Student feedback from this question was combined with responses to the ungrading/self-assessment question posed at the end of the final SSLO, which was not anonymous (see Table 2 for a list of themes). These data were integrated with notes from one-on-one meetings to evaluate each of the original four research questions, as described below.

Fosters more intrinsic motivation and greater self-accountability

The most mentioned attribute of our ungrading scheme, using a community-generated rubric for self-evaluation, was greater motivation for and focus on learning for learning’s sake (83% of students). Self-accountability (29%) as well as depth of understanding and/or greater retention (21%), were also noted as perceived advantages. Students appreciated the focus on growth and improvement over penalties for mistakes (38%). Some commented on how they enjoyed feeling accountable to themselves and their teammates for learning (29%). The following quotes serve as examples:

“One massive advantage of ungrading was that the course focused on learning and understanding the material rather than grades and memorization…Additionally, ungrading allowed me to want to learn the material for myself rather than to get a grade. This allowed me to retain more information about immunology and class material than any other class I have taken.”

“I feel like I actually learned and internalized a lot of this information. We did not have to cram, and actually had time to go back over our assessments to grow and add more information. I think I will retain much more from this class.”

“Rather than punitive in failing with tries, this process of ungrading actually made me put more effort because I felt like I was accountable to myself, my team, and my teacher.”

Increases learner self-awareness and positive adaptive regulation of learning behaviors

Several students talked about gaining valuable insight about themselves as learners (17%), lamenting that this had not happened sooner. There were also comments about decreased inter-student competition and greater collaboration (25%). Students noted the improved trust and stronger relationships that developed through this assessment model, including between students and the instructor (13%). The following quotes are examples:

“I love ungrading. I have always hated the insane emphasis people place on grades, to the point where I do things that people have told me I’m super weird for doing! Anyway, I think ungrading is amazing because it takes away the emphasis on numbers and puts it on the actual learning and the material itself.”

“Not sure about anyone else, but when there are tests, and everyone is so focused on getting good grades, it creates an atmosphere of competitiveness against each other.”

“I thought the most significant advantage of ‘ungrading’ was that it promoted reflection and allowed for the possibility of adjustments and self-improvement throughout the semester.”

“In some classes with number grades (such as …), my focus was shifted much more toward trying to get the highest possible grades I could at the beginning of the semester so I could ‘slack off’ toward the end of the semester and still keep an A. …I think that it really prevented me from engaging with the material throughout the entirety of the course. Ungrading, on the other hand, is set up in a way that I think elicits a strong sense of self-motivation, which in turn leads to a more rigorous (yet reduced stress) learning experience.”

Reduced anxiety with ungrading, but also some grade ambiguity and process concerns

Reductions in overall stress and anxiety, with improvements in mental health, were the second most commonly described outcomes from this structured ungrading process (63% of students). The following quotes exemplify this student perspective:

“In other classes, even if I don’t check my grades, there is the conversation surrounding me about scores and averages and blah blah that does get rather stressful, but there was none of that in Immunology! And I loved it.”

“My overall stress levels about this class were decreased. I was able to approach this class differently than I approach any of my other classes because I wasn’t worried about my grade. I really focused on learning for learnings sake, and it was a lot of fun! I felt no pressure doing my assignments and that allowed me to just try things even when I wasn’t super confident.”

“Having feedback and accountability while also having the flexibility to not be at 100% all the time certainly helped my learning as well as my stress and mental health.”

“I absolutely loved the ungrading approach. Among its many advantages is the fact that it removes a lot of the anxiety from the learning process, and instead allows one to actually focus on learning material each week over an entire semester, rather than for the few days leading into an exam. While this means that ungrading likely requires more time and sustained effort, this strategy has been the most effective method for learning that I have experienced.”

At the same time, some students had anxiety related to grade ambiguity, this new process, and the requirement for grades at the end of the semester (17% of students). Comments on this theme were typically voiced in comparison with other college or secondary school classes, where students have become accustomed to relying on a grade for affirmation. Some students also had hesitations around trusting the process (17%) or the potential harm from an over developed inner critic (8%). Students shared the following thoughts:

“I think the collaborative grading criteria is great, but issues and anxiety can arise when you think about how it is a blanket criteria for every aspect of the course, and many people don’t feel comfortable in trusting that.”

“…it was very hard to let go of the constant thoughts about grades that are a product of years and years of the importance of grades being wired into me, at Pomona and elsewhere.”

“I think since we are so used to grades, at least for me my brain sometimes feels like the ungrading is too nice or not hard enough and like I’m ‘letting myself go’ or ‘being a slacker’…but this might have more to do with my own difficulties with a tough inner critic.”

Worry about the impending need to convert this self-reflection into a grade also came up, especially as the end of the semester approached. A few students mentioned stress associated with one-on-one conversations with the instructor (17%). These worries included the high-stakes and unfamiliar nature of these student-instructor conversations, plus the need to defend one’s grade. Two students also voiced concerns that students in traditionally marginalized and -vulnerable groups might not feel the same agency to self-advocate.

“A disadvantage is that we still have to get grades at the end of the semester, so it can be very stressful because you are unsure of where you stand.”

“It can feel like your entire grade is riding on the conversation you have at the end of the (self)-assessment.”

“I know that the one-on-one meetings can feel nebulous and confusing for some as the impression is that they have to defend themselves and their “improvement” over the semester, and that can be very challenging for people.”

Creates a more transparent and student-centered assessment process

Several students described this format for ungrading as a more holistic and accurate way to measure learning (38%). The novel concept of learning from mistakes and building growth into the grading calculus was also favorably received (29%). On the whole, this process was viewed by many as fairer, as well as more human-centered and holistic. Some also noted that this increased their creativity and penchant to try out new ideas or take risks. For example:

“There are a lot of advantages to ungrading: I think it’s more human-centered…”

“The biggest advantage of ungrading is that it is a much more fair and representative assessment of performance in a class.”

“I felt like I could get things out of this class for my growth as a whole person versus just to get a good grade and move on.”

Perceived as extra time for students and instructor

Students commented on a perception that this ungrading system took more or their time (regularly revisiting material, answering extra self-reflection questions, and one-on-one meetings with the instructor) as well as instructor time (weekly, individual feedback on preclass questions and one-on-one post-assessment conversations with students). However, most of these comments about time were equivocated with remarks like “worth it” or “productive.” Some example student quotes related to time investment include:

“In my own experience, the only disadvantage I can identify for ungrading is how many individual conversations you [instructor] have to have with students throughout the semester.”

“I don’t really have any disadvantages, despite it sometimes being time consuming, because I think all the time was worth it.”

“One (disadvantages) might be that …this method does also require a significant time commitment on the part of both student and teacher.”

End of semester feedback and my conversations with students also revealed the importance of some of the structural elements of the course for the process of self-evaluation. Below I outline features of the course design that students linked as important accessories to assessment and self-evaluation in this class.

The importance of collaborative learning with peers

Although not explicitly part of ungrading, peer collaboration came up repeatedly in student feedback and therefore requires some unpacking as a separate theme. For example, feedback from students in my first ungraded Immunology course (Fall, 2021) initially alerted me to the importance of teamwork for deep learning and student self-assessment. Likewise, feedback from students in this Fall 2022 course connected working in teams as critically supporting their learning, self-confidence, and ability to self-assess (25% of students). They noted that this required time, both to develop a system of working effectively as a team and to build trust among group members. For this reason, we opted to keep teams constant throughout the semester for all of the summative assessment exercises and for weekly discussions about the preclass questions (typically, Monday class meetings). We also fleshed out more specific examples in the assessment rubric for expectations around student–student interactions (e.g., attendance at, preparation work for, and follow-through in outside of class peer meetings).

This practice of working in teams was also criticized by students in some of my earlier alternatively graded courses. This was especially true during the pandemic, when we stayed in-group and masked for all class meetings, to avoid additional spread of infectious disease. Students appreciated the caution but lamented not getting to know as many of their peers. As a means to increase their interactions with other students they were placed outside their 4-person team for all in-class active learning exercises in that Fall 2022 class (generally, Friday class meetings). Feedback on this was extremely positive; they enjoyed getting to know new peers, the opportunity to transfer ways of thinking and explaining concepts to students outside their teams, and the chance to bring new ways of thinking back to the team. This practice was coined “cross-pollination” by one student. This allowed us to create and maintain the bond of trust within the group, which facilitated the vulnerability required to share their initial response to preclass and summative assessment questions, while also allowing students to get to know peers and expand their ways of thinking about the material.

Other structural elements that help support ungrading and self-evaluation

In their feedback, students commented on additional features that I consider part of the course design and structure, besides teamwork, that supported their learning and ability to self-assess. Many of these structural elements are illustrated in Figure 2. Specific examples included:

• predictable weekly online learning modules that allowed them to create routines, anticipate upcoming work, and work at their own pace

• a suggested cut-off date for when they were expected to have a baseline (85%) mastery of the material from each learning module and to prepare for in-class group work

• using individualized feedback on preclass to identify key concepts and details, and the ability to customize their response by taking advantage of additional resources (peer mentor sessions, office hours, outside of class meetings with their team) to ultimately fill in their missing pieces

• active-learning exercises that intentionally exposed them to students outside their teams, allowing them to meet new people and benefit from new ways of thinking about the material

• the ability to revisit their previous thinking during summative assessments, after discussing questions with others, and re-articulate their answers to these real-world questions

Many of these features connect to one or more of the self-assessment criteria (see Table 1). Therefore, these serve as reinforcing principles, guideposts or benchmarks, that helped students to engage in regular and largely effective learning activities, thus preparing them for a more positive experience during the self-assessment process.

Discussion

One of the primary research questions that inspired this inquiry was whether ungrading, and this process of co-creation of rubrics for self-evaluation, would increase internal motivation for learning. In their written feedback, the most common example of the advantages of this system was feeling more motivated to learn and learning for learning’s sake. Since the word motivation never appeared in the question prompt, it was interesting that many students elected to use this word to describe their feelings. I also witnessed the locus of control for learning move away from me (the former grader), toward the learners. Students talked about feeling curiosity and not about what they “needed to know.” Instead, one of the themes that emerged was feeing incentivized to learn from mistakes. This latter point is worth some attention. In my time teaching I’ve witnessed increasing reluctance of students to reveal academic weaknesses or conceptual misunderstandings. Presumably, over fear of being labeled as a poor student or “outed” for what they do not know. Yet, authentic learning requires that we uncover and examine our misconceptions and confusions. This shift of attention toward interrogating mistakes was refreshing and helpful for the learning process. It made me a better and more individualized coach for my students. Assuming this was happening in other venues, this has the potential to improve learner self-awareness, and contribute to a more honest and productive engagement with peers.

This leads to another advantage that I noticed, and which came up in student reflections. Students talked about gaining insights into themselves as learners, and I improved in my ability to guide their learning. For the former, I credit our conversations about how learning works and the thoughtfulness of student contributions to our rubric. Since our assessment rubric wasn’t completed until after week 3, students had enough experience with the class to make wise and self-accountable suggestions. This gave them built-in incentives to prioritize high-impact practices, like preparing before class, revisiting material later, and working through problems with peers. While these outside of class practices were fruitful, it was sometimes hard to know what was enough. Some students resubmitted responses 3 or 4 times, until there was no more feedback from me. We had conversations about diminishing returns and inefficiency. This led us back to the rubric, where we added 85% as a sufficient mastery benchmark for preclass questions. Admittedly, this interfered with my embargo on scores. It meant students calculated when they could stop resubmitting; no suggested revisions on 13/15 responses (86%) meant they could stop but 12/15 suggested they should revise. When queried about this, students preferred to have this threshold that suggested “good enough.” I also adapted my behavior, giving a thumbs up to answers that were mostly there but not perfect. This happened as I began to trust that they would pick up the missing pieces as we revisited and applied the material later, for example, during in-class activities and summative assessments. I therefore also learned to let go of the “one and done” mentality around assessment. I started trusting that students would take advantage of these opportunities to bolster their understanding, even if I wasn’t quizzing them on it.

This connects to the second research question, about whether students would engage in more productive learning activities. I noticed a gradual but significant shift toward what I consider high-impact practices. This might not be the same for every class, but for this class completing weekly lessons and attempting to answer the preclass questions early (before Monday’s class) benefited the students on this schedule, even though answers were not due until Tuesday. I watched this shift happen after the first summative assessment (week 4). Several students commented on this in their first set of metacognitive reflections, noticing that some front-loading of the work added to their depth of understanding and learning efficiency. They commented on more productive teamwork sessions, asking better questions in class, and improved notetaking. Many still took advantage of the occasional busy week to submit late or not at all, without penalty. But they generally noticed and implemented this front-loading behavior change. This meant that activities I planned for later in the week became opportunities to revisit and reinforce concepts, not first exposures. Thus, spaced repetition and retrieval practice, both scientifically-sound learning techniques (Eyler, 2018), became the norm. It was fascinating that this evolution in practice (for most students) came naturally from the process of metacognition and self-evaluation, rather than from the instructional team.

Students also noticed and commented on the importance of teamwork and collaboration for their learning. This collaborative feeling extended to the instructor, with students commenting in their reflections about this improved relationship. I felt like I knew my students more as individuals through our regular conversations about the material, even if this occurred via online feedback. While collaboration was not explicitly among my research questions, peer instruction is a recognized high-impact practice (Crouch and Mazur, 2001), and therefore an example of a shift toward more effective learning strategies. For most, this appeared to be an easy transition, and they commented on feelings of collaboration over competition. For a few students, the teamwork element was more of an uphill climb. Based on individual feedback, this was more common if the students described themselves as “better learning on my own” or as “too busy to take advantage of outside of class learning resources.” In the former case, it may be that some student personalities run counter to productive work in teams or that some teams were better than others about staying focused, along with other possible explanations. Again, this self-awareness was valuable even if it meant that they relied more on office hours and mentors to supplement learning. Since the rubric allowed for this, there were no negative repercussion. For students with busy schedules, if we discussed this early, we found solutions that fit the rubric, like meeting outside of office hours or substituting conversations with friends in the class for meetings with their assigned group. I worked individually with students in each of these cases. In at least one instance, this self-awareness came late, making it difficult to find alternative outside of class resources or to fill learning gaps. This student experienced less satisfaction with the ungrading process and poorer learning outcomes overall. In the recommendations section, I touch on suggestions for how to head this off.

On the question of whether students experience less stress, especially around assessment, feedback was very positive. The majority (15/24 or 63%) felt less stress, anxiety, or pressure with this ungrading format. Some also commented on improved mental health and mentioned specific practices that enhanced this (e.g., stopping when they hit the 85% mastery threshold or electing to submit preclass questions late during a busy week). Again, their self-reflections were telling. Reduced stress came partly from this breathing room but also from the ability to plan ahead, knowing they could take advantage of this release valve without consequence.

A few additional advantages were noted by students that were not part the original set of research questions. This included a perception that this process felt more holistic and fair (38% of students). Some even voiced feelings of satisfaction with and trust in the assessment of their learning. I rarely hear this in a traditionally graded class, where students are more likely to say that they felt the assessment did not accurately represent their level of understanding. At the same time, some students talked about confusion around how the ungrading process would work in practice, worries about its validity, and concern that some students might be too hard on themselves. For most who voiced these views, experience with co-creation of the rubric and meeting individually with me ameliorated most concerns. For a few, that was not the case. In the latter instances, students failed to buy into the system and especially pushed against the self-evaluation aspect of the exercise. This may not be surprising, given years of patterning around not revealing weakness and the general lack of self-agency in most educational settings. Interestingly, these same students were happy with the flexibility and team-work elements of the system, but less enamored of the self-reflection component. Perhaps, more training in this process and exposure to research that illustrates the utility of metacognition would help with this (see future recommendations).

Other indicators of learning improvement included enhancements in creative thinking (29%) and perceptions of increased depth of understanding and retention of the material (21%). While these are self-reports, I can say that I also believe that learning improved for most students. The most concrete examples came during our one-on-one conversations. These engagements could feel like an oral exam, with me probing student facility with the material. Many conversations started this way, especially early in the semester. However, by the second meeting the majority of students were more relaxed. We could get into a conversational flow that revealed the depth and reach of their understanding, and some gaps. There were conversations that took unexpected turns, into recent news related to Immunology, deeper thoughts about a question, or connections to topics in other courses. This was like watching someone go from learning words in a new language to genuine fluency—a mutually satisfying experience. In some cases, this happened weeks or months after the underlying topic had been covered, suggesting genuine learning retention. While this could be an artifact of meeting individually with students, which I have not done in other classes, additional pieces of evidence support this. In their reflections, students supplied examples of using their Immunology learning in the other classes and in conversations with family or friends. The end of semester STEM Equity Symposium was another opportunity to observe retained and integrated learning, where students had Immunology-related conversations with those who visited their posters. My colleagues recounted and I experienced interactions that reinforced the perception of deep and connected learning, plus a passion for their selected topic.

There were some down sides to this ungrading format that came up. In addition to anxiety over the process, there was the issue of more time, for students and the instructor. For students, this included extra time to engage in metacognitive self-evaluation and to meet with me for 30 min after each SSLO (i.e., exam). As mentioned earlier, some also struggled with knowing when to stop resubmitting work or taking advantage of resources that might add to their understanding. To get a better sense of student time, I conducted a retrospective analysis. A question on the end-of-semester anonymous evaluations asked about how much outside of class time students spent on this class each week. The average for the students in that Fall 2022 was 5.3 h/week. The same question from previous semesters of the same course, without ungrading, averaged 5.6 h/week. Therefore, self-report data suggests that students are not spending more time in this ungraded course, maybe slightly less. Perhaps the requirement to self-reflect is novel enough that it leads to over-estimates of time.

On the question of whether this cost me significantly more time as instructor, I have a mixed response. Overall, I do believe I spent a little more time than I usually spend on this course in a graded semester. I spent a little less time in office hours or individual meetings answering student questions (outside our scheduled one-on-one). At the same time, every week I felt like I had a mini conversation (through online feedback) with each student, even if they did not come to office hours. Providing this weekly, individual feedback was a significant time commitment, made manageable because I could schedule it into my week. At first, I blocked out most of Tuesday because online preclass responses were due that morning. As I got more proficient, 4 h was usually sufficient (for reference, I include 10–12 questions in each assignment and had 24 students in the class). The process was also instructive and saved me time in planning for the next two class periods. I had a clear sense of what activities to focus on after reading student responses. It was also gratifying to see tangible progress and to have an opportunity to boost student confidence with my feedback. Having used JITT for years, without individual feedback or resubmission options, I witnessed significantly more student growth when students received written feedback without scores, with opportunities to resubmit. This is consistent with the differences noted by Ruth Butler (Butler and Nisan, 1986; Butler, 1987) comparing task- versus ego-based evaluation.

The biggest time sink came in the weeks after SSLOs, when I held individual meetings with students (~12 h to meet for 30 min with 24 students). Of course, I would likely have spent a comparable amount of time grading 24 exams, mainly evening and on weekends, versus weekday hours for these student meetings. The grading is certainly less gratifying, so I will gladly make that trade. Spreading those meetings over 2 weeks made this more manageable.

My final research question was whether co-creating criteria for assessment would help build greater trust in the assessment of learning and facilitate self-assignment of grades at the end of the semester. Based on student feedback, results on this were bimodal, with the majority of students expressing positive feelings. There were more instances when I suggested a higher grade than situations where I felt students were inflating their grades. Students spoke very frankly about their challenges, anxieties, and coping strategies, plus a host of other life details. I felt like I got to know them as human beings in the process. These conversations were not always easy. Even by the third round, some students struggled to relax and just talk about immunology with me. This pattern and the fear of revealing inaccurate thinking is highly engrained. In some instances, we broke through the façade and students relaxed into an enjoyable and growth-promoting conversation. It took getting them to trust that I wasn’t trying to catch them out or looking for perfection. In a few cases, this did not happen, whether because of lingering fear, the power dynamic, or holes in knowledge, it is hard to say.

Importantly, I felt more confident in my assessment of student learning using this process of ungrading. It is easier to distinguish a fundamental misunderstanding from a small mistake when you can ask follow-up questions. And memorization will only get you so far in a conversation that takes unexpected turns. I can appreciate that these conversations were not easy, and that performance anxiety may have contributed to mistakes. Nonetheless, between weekly individual feedback, these 30-min + individual conversations, office hours, and the end of semester symposium, I felt confident in my assessment of student knowledge. I also got to know students as individuals and could witness growth. I surveyed students before the class began about prior knowledge, and it was clear in my first post-SSLO conversation that some entered with sophisticated abilities to articulate this knowledge. I tried to incorporate this into conversations about setting personal goals and monitoring growth. I suspect that I included this “distance traveled” factor more in my assessment then they did, assuming as they do that everyone knows more than them. This could contribute to a higher grade in my estimation than in theirs.

I also noticed a shift in power dynamics in the class, and some students commented on this. This was especially apparent during the iterative process of co-creating our assessment criteria. The process of discussing and creating this document was among the most humanizing and rewarding activities that I have facilitated with students in my 25 years of teaching. The process infused the course with student voice and wisdom, giving them agency and ownership in the outcome. It was a rare moment of power-sharing, peeking under the hood of higher education in ways that I rarely do with students. I believe this helped us each to develop perspectives from the other side of the lectern.

One of my most abiding and enlightening revelations came from witnessing the growth in a handful of students who entered with low levels of self-confidence and no prior exposure to the course topic (based on early survey responses and one-on-one conversations). These students benefitted the most from this assessment format. Those who committed to regular groupwork, met semi-regularly with mentors, and resubmitted preclass responses based on feedback, generally exceled in the class. This collective set of activities allowed for regular and varied reinforcement of the material, resulting in what I came to see as greater depth of understanding and retention of material. This was especially clear during one-on-one meetings. Students accustomed to discussing immunology with peers and resubmitting responses could banter in fluent Immunology, even answering tangential questions without getting flustered. In some cases, they lacked confidence in their answers, despite the accuracy. This provided me with opportunities to build confidence by applauding their progress. On several occasions, we ran way over time because it was hard to stop in the middle of a satisfying exchange of ideas.

One student comment nicely encapsulates many of the advantages and disadvantages shared by students at the end of this semester, concluding with suggestions for the future.

“I see that the ambiguity of the ungrading class structure can bring stress to people. I know that I, and a lot of other students, put in so much more time than we initially thought we would need to, into the class because the ambiguity made us feel like we needed to do everything and always fill up our time. However, every time I looked at the grading criteria, I was reminded that this course was not disguised as a self-paced course, it was a self-paced course. The ambiguity that I initially thought was trying to trick me into working overtime, was just breathing room. In the end, while the new concept of ungrading may bring some students anxiety, I think the biggest advantage is the breathing room that you are allowed. With the criteria allowing students the ability to not be at 100% every week, I truly felt that I was able to take my mental health breaks by choosing not to be as active in a class session one week or asking for an extension on my PCQS [preclass questions]. I think that in the end, everyone is going to be feel anxious about the ungrading system until they live through it, so the advantages outweigh the disadvantages. However, I do think that compiling a list or document with feedback from past students who talk about the classroom style would be helpful to calm some nerves. I remember my conversations with the mentors calmed some of my anxieties, especially when going into my first self-assessment under the ungrading criteria.”

This student makes interesting observations about student perceptions of how much time they will spend on an ungraded course, despite the added breathing room. This was echoed in my conversations with students, including one who said (paraphrased): “I put so much effort into this class and I do not understand why, since there’s no grade hanging over my head.” Other notable points from this quote include reference to the self-paced nature of the course and breathing room, linking these with lower stress and positive mental health practices. The quote ends with some ideas for the future that I flesh out below.

Recommendations for the future

The following are suggestions for next steps and future ungraded classes, based on my observations and feedback from students and peer mentors.

Early “selling” of key foundational elements

To allay student anxiety over the process of ungrading and self-assessment, the peer mentors suggested more “selling” of the important foundational elements of the course structure. For example, they suggested that the instructor and peer mentors spend time in the first week reinforcing the utility of peer learning, mentor sessions, and office hours. It was clear that students who put consistent effort into these activities benefited the most. This makes pedagogical sense. We know from the literature that talking through complicated concepts with others is a low stakes way to test and refine one’s own understanding, as well as surface confusions (Noroozi and De Wever, 2023). As a part of this, the instructor could introduce the class to literature on the science of learning and the power of self-reflection. In the future, I will spend more time in the first weeks selling the philosophy and science behind alternative assessment and talk more about the benefits of power-sharing with students, including quotes from past students.

More structure around peer and outside of class engagement

Most learning does not happen in a 50 min lecture. What students do when they work with peers and outside of class time is crucial. However, we spend little if any time training students in how to do this effectively. One recommendation would be to help students create more structure around their outside of class time and work with peers. We observed that many of the students who spent less time in outside of class peer engagement displayed less depth of understanding and self-confidence in one-on-one meetings. They struggled with out of the box thinking and were easily flustered, not infrequently asking to check their notes before responding to my questions. There were one or two exceptions; often students who entered the class with significant prior knowledge and could therefore afford to pass on these learning opportunities without consequence. But this was the rare. Once we noticed this, the peer mentors and I started encouraging students to engage more in low-stakes opportunities to practice with others, but this was fairly late in the semester. In retrospect, I would emphasize this earlier and suggest that groups develop a structure for their engagement as well as a reflective practice around teamwork. Having an agreed-upon structure may also encourage those who say they work better alone to give it a try.

Set SMART personal goals

One of the students, in reflecting on progress toward their personal goals, noted that they had not been very thoughtful in setting goals in the first place, making follow-through harder. They recommended we consider setting SMART goals in the future—Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, and Time-related or -bound (Doran, 1981). I noticed that regular conversations with students about their goals often yielded a desire to update or modify these partway through the course. Thus, in the future I plan to engage in SMARTER goal setting, which adds Evaluate and Revise to the mix.3 For example, after each of the two self-reflection points midway through the semester I would ask students to evaluate the goals they set and consider whether these need revision to remain SMART. This should help students to make progress on their goals and encourage them to use self-reflection to make adjustments, as needed.

Instructor time management

In terms of impact on the instructor, this new format of teaching and assessment was rewarding, and I have no plans to turn back, but it did take extra time. I will make some adjustments in the future, especially in a larger class. Some ideas for managing this include shorter weekly question sets, help from student teaching assistants to provide some (not all) of the weekly feedback, and scattering one-on-one meetings over 2 weeks instead of just one. To further humanize this process, I plan to include how this model benefitted me as an instructor. I found more joy in teaching and getting to know students better. It lowered the power divide between myself and the students, helping us to feel more like we were on the same team. Writing recommendation letters was also a breeze. From student self-assessments and our conversations, I had very specific comments to share about individual attributes. Finally, it was gratifying to see tangible progress, to read about what students were most proud of (one of our collective favorites), and to witness students applying their knowledge to new situations, with less fear about saying something wrong.

Conclusion

In conclusion, I have found this ungraded course structure and working with students to design an assessment tool to be a liberating and humanizing practice. The major advantages I see are similar to those given voice by the students: an emphasis on learning for the sake of understanding; lower stress; a more holistic and accurate assessment process; it allows reflection on mistakes to lead to growth; a more collaborative environment; and stronger instructor-student relationships. Importantly, it also brought me added joy in teaching.

I would like to end with another story. A student in my first ungraded course was struggling to discuss the assessment questions during our first one-on-one conversation. She also admitted to struggling in working with her teammates, feeling like she was leaning on them too much. She had kept up with the work, using my feedback to revise her preclass responses, but she could not apply this to new situations. We talked about her learning and studying strategies and it became apparent that she had never learned how to teach herself. She also rarely challenged herself to go deeper than aiming for correct answers. As a senior STEM major who had done “well enough” in her classes, she was shocked that this might not be enough. She wondered aloud how she got this far without really needing to apply what she learned? Her own conclusion was that she had patterned her practices on what worked for most of her classes. We discussed her options. She could continue to do “well enough” in this class and leave with a B or B-. She was OK with that. Her main worry was letting down her team and disappointing herself. She asked me to help her do more and we came up with a plan. She committed to 30-min check ins with me every week. She made a diagram or concept map of the material each week, to prepare for our meetings. At our meeting, we discussed the material and worked on new challenge questions together (e.g., outlining the events in an immune response to a new pathogen). She committed to attending most of the weekly mentor sessions and meeting with her student team every week. By the end of the semester, she had moved from moderate, superficial understanding to much deeper comprehension that she could apply to new scenarios. More importantly, she had greater self-confidence and had learned important things about herself as a learner. If we had been in a traditionally graded class, that hard conversation would never have happened. She would not have learned as much immunology or valuable things about herself. And maybe she would walked away with an A anyway.

Limitations of this work

The exercise described in this paper occurred at a highly selective and well-resourced small liberal arts college with a relatively small class of mostly juniors and seniors. The course in question is an upper-level elective, attracting only students with interest in the topic. How this would play out in other campus settings, with larger class sizes, with students who are new to college or taking a course as a requirement, is untested. The observations described in this report come from two semesters of experimenting with ungrading in an Immunology course, and just one semester of a more structured form of self-assessment, as described.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Acknowledgments

I would first like to acknowledge and thank the many Immunology students at Pomona College who have patiently participated in a range of attempts at alternative grading, including two fully ungraded classes. I especially thank my peer mentors—Ciannah Correa and Kofi Osei-Opare (2021), and Natalya Braxton and Berge Hagopian (2022). They participated in forms of ungrading as students and worked as peer mentors for future Immunology students. They were all instrumental in the development of the final self-assessment document. I would also like to thank my colleagues at the Pomona College Institute for Inclusive Excellence, Travis Brown, Hector Sambolin, Jr., and Malcolm Oliver II. Their patience with listening to me tell these stories and help with thinking about assessment is appreciated. Finally, I would like to thank Jessica Tinklenberg and Sara Hollar, from the Claremont Colleges Center for Teaching and Learning. Sara provided insight into student survey questions and thinking about the assessment of ungrading. I have Jessica Tinklenberg to thank for directing me to countless ungrading and critical pedagogy resources, and for turning me on to ungrading in the first place.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2023.1213444/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

1. ^https://gradingforgrowth.com/p/an-alternative-grading-glossary

2. ^https://www.jessestommel.com/tag/ungrading/

3. ^https://www.professionalacademy.com/blogs/are-you-being-smart-er/

References

Anderman, E. M., and Murdock, T. B. (2007). “The psychology of academic cheating,” in Psychology of academic cheating. eds. E. M. Anderman and T. B. Murdock (Elsevier Academic Press), 1–5.

Blum, S. D. (ed.). (2020). Ungrading: Why rating students undermines learning (and what to do instead). West Virginia University Press.

Bovill, C. (2020). Co-creation in learning and teaching: the case for a whole-class approach in higher education. High. Educ. 79, 1023–1037. doi: 10.1007/s10734-019-00453-w