- 1Department of Religious Education, Catholic University of Eichstaett-Ingolstadt, Eichstaett, Germany

- 2Institute of Primary Education Research, Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nürnberg, Nürnberg, Germany

This article argues that the success of today’s education has to be measured by the number of people who act wisely in crisis-ridden times, which also translates into acting sustainably. Research shows that education leads to knowledge, values, attitudes, judgments, and intentions to live sustainably, but people do not act on them. I refer to the gap between inner movements and actual behavior as the “inner-outer gap” and ask: “Is there an evident model or concept that educators can use to help their students bridge this gap?” The exploratory literature review shows that the answer is no. There are many helpful models in research on morality, moral automaticity, domain theory, and there are empirical models to explain sustainable action, but there is no single model that does the trick of showing how to bridge the gap. This raises the second question, if an amalgamation of different models might be helpful. In the discussion I used a segmentation method to fuse different theories and present a new approach within this article: The Tripartite Structure of Sustainability. It describes that actions are carried out under the impression of one of three foci, each of which can have a stable, situational or an automated quality. Empirical research leads to the hypothesis that a self-focus reinforces the gap, a self-transcendent focus bridges it, and a social focus may do both, depending on the social environment. If the hypothesis proves true, the model could help educators decide what to focus on to promote wise behavior in our unsettle world.

1. Introduction

Our world is currently facing a plethora of challenges to which easy solutions are far from forthcoming. The environmental crisis, rising inequality, diminishing resources, increasing numbers of people subject to forced displacement, human rights violations against refugees, and pandemic diseases are alarming and unsettling in their individual and cumulative effects. The discipline of economics refers to a “VUCA” world towards and in which we have to educate, meaning an environment characterized by increasing vulnerability, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity (Bennett and Lemoine, 2014), within which we still must make decisions. To act in this world in a wise way is a necessity evidently underlying the concerns of John Dewey when he said in his famous and still relevant speech “The teacher and the Public” in 1935: “The business of the teacher is to produce a higher standard of intelligence in the community, and the object of the public school system is to make as large as possible the number of those who possess this intelligence. Skill, ability to act wisely and effectively in a great variety of occupations and situations, is a sign and a criterion of the degree of civilization that a society has reached” (Dewey and Weber, 2021, p. 158).

Across the globe, people with a high level of formal education benefit, for example, from higher incomes and better employment opportunities, longer life expectancy and better health (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2016, 2017, 2020). Formal education appears to have notably positive effects in terms of the criteria used by the OECD to rank countries internationally. All these benefits of education notwithstanding, Biesta has raised the question of whether the overarching objective of education rests on a presumed “common sense” basis without explicit discussion, cautioning: “The danger here is that we end up valuing what is measured, rather than that we engage in measurement of what we value. It is the latter, however, that should ultimately inform our decisions about the direction of education” (Biesta, 2009, p. 43). With this warning in mind, we might do well to rethink our approach to the success of education, examining the contribution of our education systems to addressing the global issues and complexities of our contemporary world. We should critically consider whether these systems are teaching future generations in such a way as to endow them with the capacity to create solutions and, in the long run, to “measure what we value.” The environmental crisis is a highly relevant issue with which to begin this endeavor.

Answers about what to do at the individual or societal level are numerous [e.g., Kuhnhenn et al., 2020, UNESCO program Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) beyond 2019, in which various educational institutions in numerous countries participate]. But simultaneously, we have ample evidence that educational efforts to transform existing knowledge, attitudes and values around the preserving of the environment are failing to translate into action (Flynn et al., 2009; Frederiks et al., 2015; Allen, 2016; Binder and Blankenberg, 2017; Moser and Kleinhückelkotten, 2018; Li et al., 2019; Gao et al., 2020; Osunmuyiwa et al., 2020). In addition, other societal and educational objectives addressed in the UNESCO-ESD program such as political participation and ethical shopping and purchasing habits fail to convert into sustainable action (Carrigan and Attalla, 2001; de Pelsmacker et al., 2005; Kam and Palmer, 2008). Some educators have taken great care to design programs that address the gap and urgency of current global challenges; however, it appears that even carefully planned programs have not translated into sustained positive environmental action (see, for example, Parth et al., 2020). Educated people seem to make the right judgments about the actions needed to address global challenges: they know what needs to be done, they value such actions, have the right attitudes, and they really intend to do what is necessary… and then they act differently.

This phenomenon can be described as a gap between the right inner assessment and the wrong outplay. And already the ancient Greeks, such as Aristotle, thought about and this gap by using the term “akrasia”: knowing what is right but failing to act on that knowledge (DeTienne et al., 2019). In this article, I argue that it is this gap, and its apparent intractability, that stands in the way of appropriate and wise action on significant global and societal challenges. And it is this gap that education must address. When addressing the gap it has to be acknowledged that the content we focus on is not overall important: The focus is why inner movements towards wise action do not translate into real action. For the sake of simplicity in this article, we will focus on sustainable action in terms of the SDGs anyway, as we see this as the most relevant endeavor of our time. In the following lines, I would like to provide a deeper understanding of this gap and explore how what is known about the gap can help educators guide their students to act wisely in these crisis-ridden times.

2. Research question

The paper poses the following research questions:

• Is there an evident model or concept that educators can use to help their students bridge the gap between their knowledge/intention etc. and their real action?

• If there is not one model or concept, can different models or concepts be merged to create an evidence-based education towards sustainable development?

3. Method

As part of an exploratory literature review, various databases were searched for useful models or concepts using terminology such as “judgment-action gap,” “value-action gap,” “attitude-action gap,” “knowledge-action gap,” and “intention-action gap.” Fundamentally, these terms – with slightly different emphases – all mean something similar: the action actually taken is different from what the internal processes have concluded. For the purpose of operationalization and terminological simplification, I use “inner” for human judgments/values/knowledge/intentions/attitudes and “outer” for all corresponding outcomes such as actions or behaviors, regardless of their specific emphasis. The references in the reviewed articles were used to search for additional relevant sources. Considering the central theories and research on the inner-outer gap, it become clear that there are two relatively independent strands of addressing the question: The first calls for moral behavior. If we assume that acting sustainably is the morally right thing to do, then this strand is relevant. The complexity of environmental action is seen here as part of a moral decision-making process. The second strand is research that considers directly what prevents or encourages individuals from acting sustainably. I have reviewed both strands for the most important and influential theories and models. In the following pages, I not only briefly explain them, but also, where possible, show how they were operationalized and how researchers rate their empirical predictive power for moral and sustainable behavior.

4. Examining existing models and concepts

In the examination of relevant theories and research it became obvious that the strand of research on morality has a lot longer tradition and is therefore more extensive. To provide orientation the subsections “Classical Research on Morality,” “Moral automatisms” and “Domain Theory” were divided.

4.1. Strand 1 – classical research on morality – principles of moral decision making

The Classic research on Morality can be distinguished into historical sources and research on moral judgment and emotion and research on moral identity.

4.1.1. Historical sources and research on moral judgment and emotion

Research in the moral domain often refers explicitly or implicitly to Aristotle’s idealized concepts of “akrasia” and “phronimos” (Darnell et al., 2019), that is, a person who is able to make best decisions in complex situations in accordance with universal moral standards. In modern times, Lawrence Kohlberg identified stages of moral development, which lead to Aristoteles ideal: For each stage, he sets out typical questions, which occupy the subject at each of these stages (Kohlberg et al., 1983).

In the preconventional stage people ask:

• “How do I avoid punishment?” and

• “How do I gain the most for myself in a particular situation?”

In the conventional reasoning the questions are:

• “How do I gain the trust of my peers?” and

• “How can I uphold the social order?”

In the postconventional stage, people consider the questions:

• “How can I enforce/uphold justice?” and

• “What is universally correct?”

The relative lack of predictive power generated by Kohlberg’s concept with regard to action prompted Rest and colleagues to develop it further. Their Defining Issues Test (DIT) operationalizes Kohlberg’s states through the examination of the intended reaction to moral dilemma situations (Rest et al., 1999). The test has been able to explain the emergence of moral cognition (Brooks et al., 2013; DeTienne et al., 2019) and “has never been seriously questioned or challenged” (Krettenauer, 2019, p. 144). However, its predictive power with respect to actual action through moral judgment is still considered too limited (Darnell et al., 2019; Krettenauer, 2019).

Another attempt to operationalize morally motivated action is Rest, Narvarez, Darnell and others’ Four Component Model, which is sometimes called the Neo-Kohlbergian Four-Component Model. It was developed exploratory based on meta- and factor-analyses of empirical data and deliberately considers moral emotions, a concept that Kohlberg mentioned in his work, but in contrast to moral judgment did not operationalize further. The model states that a person, in order to exhibit moral behavior, requires

• moral judgment,

• moral sensitivity (the ability to identify and attend to moral issues),

• moral motivation/will (giving priority to the moral value) and

• moral implementation (consisting of qualities and skills that help to continue with a moral task – also termed as moral character) (Darnell et al., 2019, p. 35 f.).

Up to now, the model has not been proven in its multifactorial structure beyond specific contexts of application as it was rarely empirically conceptualized to capture all four components (Frimer and Walker, 2008; Darnell et al., 2019; DeTienne et al., 2019).

4.1.2. Research on moral identity

Another strand of research into morality began with Blasi, who became one of the most influential researchers in this field (Frimer and Walker, 2008). To explore what motivates people to judge in a moral way, he pointed to the moral personality of the individual, or, in his terms, moral personhood. An individual who holds morality as central to one’s self-concept should be able to resist going astray in the face of competing interests and therefore be able to bridge the inner-outer gap. While Blasi did not operationalize his concept (Frimer and Walker, 2008), other scholars such as Colby, Damon and Hart did, in a number of differing ways. Within their review of 129 empirical studies in 25 years of work on the self in moral functioning, Jennings et al. (2015) observed that approximately 70% of those studies adopted Aquino and Reed’s (2002) conceptualization and measures of moral identity (p. 152). Aquino and Reed offered a definition and operationalization of moral identity grounded in theories of social identity and self-concept. They defined moral identity as a self-conception organized around a set of moral traits (p. 1424). The measurement of the outcome of moral identity was based upon the virtues of a person being caring, compassionate, fair, friendly, generous, helpful, hardworking, honest and kind (2002). The authors found support for distinguishing between a private dimension of self-importance “Internalization,” and a public dimension, “Symbolization.” Both dimensions predicted the emergence of a moral spontaneous self-concept and self-reported volunteering, but only the Internalization dimension predicted actual donation behavior (p. 1436). Jennings et al. (2015) warned to over-rely on this conceptualization, as it neglects other aspects of the moral self (p. 152).

4.1.3. Conclusion: classical research on morality

Krettenauer (2019) summarized that all three concepts I have presented so far – moral judgment, moral emotions and moral identity – are overall not good predictors of moral action. Scholars in this field have therefore called repeatedly for a model to identify a new and productive approach (Anable et al., 2006; Darnell et al., 2019), or one that at least consistently incorporates the most relevant factors (Sweeney et al., 2015; Stephens, 2018; DeTienne et al., 2019). It seems that the classical research on morality is missing relevant factors or concepts to explain moral behavior. I therefore want to introduce concepts that might complement classical approaches. All of them were deducted out of empirical findings, but are not (yet) empirically confirmed.

4.2. Strand 1 – moral automatisms incl. Triune Ethics Theory (TET)

The above-mentioned theories see moral reasoning as deliberate. Narvaez and Lapsley (2005) doubted, whether is it appropriate to see moral reasoning that way: “If moral conduct hinges on conscious, explicit deliberation, then much of human behavior simply does not qualify” (p. 143). Lapsley and Hill (2008) categorized the models which have been presented thus far, and which use deliberate and slow reasoning (like the models of Kohlberg, Blasi, Darnell and others) as “system 2 models.” They contrasted these with “system 1 models” that emphasizes fast, implicit reasoning (moral automaticity). Two system 1 models are heuristic models presented by Gigerenzer (2008) and Sunstein (2005). According to them, by means of experience individuals develop very context-sensitive heuristics that act as shortcuts for making simple moral decisions. Haidt went one step further: using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies on neuroeconomics and decision-making, he considered that upon being asked why they have behaved in a certain way, people search for reasons to justify an intuitive judgment made in milliseconds. Haidt (2001) social intuitionist model (2001) asserts that reactions to all internal and external stimuli are responses to the fundamental question “approach or avoid?,” and thus calls into question the notion of deliberate conscious decisions.

Another theorist that questioned the idea that action depends upon conscious decisions was Darcia Narvaez with her Triune Ethics Theory (TET). I will elaborate on this theory further as it is relevant for our argumentation later in this article. Narvaez collected empirical findings from neurobiology, affective neuroscience and cognitive science and built her so-called ethical stages bottom-up. TET focuses on “motivational orientations that are rooted in evolved unconscious emotional systems shaped by experience that predispose one to react to and act on events in particular ways” (Narvaez, 2008, p. 96). She distinguished three moral systems that drive decision taking processes and claims that they are mostly developed in early childhood. She wrote “As motivated cognition, when a particular ethic is active, it is presumed to influence perception, information processing, goal setting, and affordances” (Narvaez, 2009, p. 137).

• The Ethic of Security is activated according to Narvaez, when people strive for physical safety and autonomy. These concerns, as well as the desire for dominance and status, underlie habitual thinking and interaction. Action is motivated by emotions like fear, rage, seeking and sorrow/ panic (dominance). Morality is self-protective and self-assertive as well as self-concerned in interpersonal relations (Narvaez, 2010).

• Narvaez saw Ethic of Engagement rooted in the mammalian emotional systems that drives us towards intimacy, such as care, lust, play (promoting harmony and sociality) and grief/panic when separated from others. This ethical system is active when people are attuned to each other (via limbic resonance). According to Narvaez (2010), only with adequate care can the Engagement Ethic develop fully and lead to values of compassion, openness and tolerance (p. 103).

• The Ethic of Imagination represents the “mind of morality” (Narvaez, 2010, p. 146) and allows people to escape their needs for physical survival and intimacy. Navarez theory suggests that moral decision making “has to do with the coordination of instincts, intuitions, reasoning and goals by the deliberative mind” (Narvaez, 2010, p. 147). However, in order for this capacity to develop properly, it seems crucial that people experience the feeling of being physically safe and integrated into their social group, ideally early in their life.

4.3. Strand 1 – domain theory

Not only researcher on moral automaticity opposed the Kohlbergian view that actions are solely informed by a developmental stage. Domain theorists like Nucci (1997), Nucci et al. (2018) stated that beginning in early childhood, children construct moral, societal, and psychological concepts in parallel, rather than in succession, as is proposed by global stage theories (DeTienne et al., 2019). They considered each action to be informed by situational adherence to social conventions and by how individuals view themselves and others. Turiel (2006) cited evidence collected in different cultures, that already very young children consider the harming of others as wrong – even if beloved adults or peers in hierarchically higher positions legitimize those actions. The Domain Theorists considered this as the domain of “Moral Universals” informing action situationally. This postconventional reasoning contradicts Kohlberg’s theory of developing postconventional judgement only after the preconventional and the conventional stage are passed. Domain Theory empirically showed that individuals explain a specific action with one of three domains: Beside the domain of Moral Universals are the domains of Personal Choice (e.g., a person legitimizing action with her right to do what she wants to do Nucci and Turiel, 2009) and the domain of Social Norms (including cultural norms). The domains complement or compete each other dependent on the specific situation.

To conclude the three chapters on morality, it has become obvious that since ancient times much thought has been given to the question of why people act morally, which to act sustainably would be in our view. However, no theory or model was able to predict moral action empirically in a satisfying way. Therefore, it is reasonable to explore another strand of research that focusses – differing from research on morality – on very specific outcomes as for example eco-friendly traveling.

4.4. Strand 2 – empirical models which explain sustainable action: TPB, NAT, VBN, and CADM

There are four influential and commonly used models in the second strand of relevant research on a specific environmental outcome, usually referred to by their abbreviations. These are the theories of planned behavior (TPB), norm activation (NAT), the value-belief-norm (VBN), as well as the comprehensive action determination model (CADM). The TPB holds behavioral intention to be a central determinant of action, influenced by attitudes toward a behavior (behavioral beliefs), subjective norms (normative beliefs), and perceived behavioral control (control beliefs). Empirical findings show strong support for this model, as evinced in, for example, Panda et al. (2020), Lane and Potter (2007), and Fabian et al. (2020). However, Adnan et al. (2017) criticized this model for not considering possible hindering factors such as a poor train connection when a person wants to switch to public transport. Klöckner and Blöbaum (2010) criticized its insufficient prediction of repetitive behaviors.

Norm Activation Theory (NAT) explicitly incorporates morality by taking normative self-expectations (moral or personal norms) as central moments, which contribute to altruistic behavior, activated by awareness of consequences and a feeling of responsibility. Klöckner (2013) reported (meta)analyses that demonstrate the model’s explanatory power in relation to intended behaviors. He also, however, offered the following criticism of the theory: “In contrast to the TPB the NAT focuses strongly on moral drivers of pro-environmental behavior, ignoring non-moral motivations which would be captured by the TPB.

Value-belief-norm (VBN) Theory (Stern, 2000) was developed to improve NAT. It adds personal values as factors antecedent to beliefs and personal norms and also supplements New Environmental Paradigm (Dunlap et al., 2000, cited after Klöckner, 2013) and the relatively stable general value orientations of “self-transcendence” and “self-enhancement.”

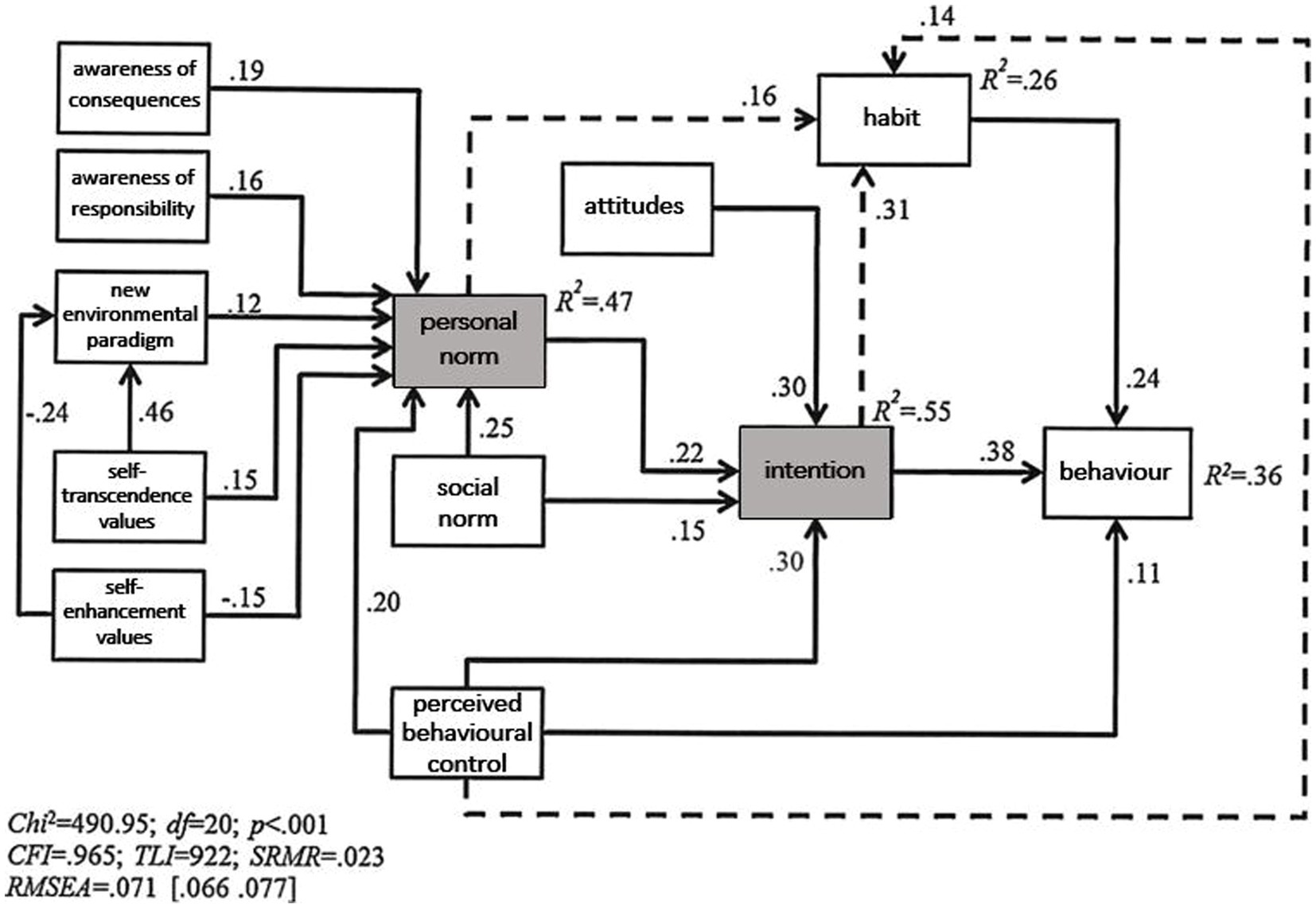

His critique of the different models led Klöckner (2013) to form a comprehensive model combining TPB, NAT and VBN theories. Since all three of these constituent theories perform notoriously poorly in the prediction of repeated behaviors, he supplemented them with “habits” and “social norms.” The resultant “comprehensive action determination model” (CADM, see Figure 1) is likely the most extensive and inclusive empirical model for explaining sustainable behavior. The model was tested using a meta-ana1ytical structural equation modelling approach based on a pool of 56 different data sets with a variety of target behaviors that supported the model (p. 1028). It holds predictive power of 36% for various types of behavior across different cultural contexts. Although this must be seen as high for a model of this complexity, one might wish for a better prediction. In addition, the model itself seems too vague in some respects to be used for educational purposes: What habits, attitudes, or personal norms exactly are helpful for sustainable action – and are there any that might be hindering?

Figure 1. Klöckner’s (2013), comprehensive action determination model. [Results of the meta-analytical structural equation modelling based on the pooled correlation matrix (modified: abbreviations in full)]. Reprinted from Global Environmental Change, 23, Klöckner, C. A., A comprehensive model of the psychology of environmental behaviour—A meta-analysis, p. 1032, Copyright (2013), with permission from Elsevier.

When research starts with outcomes rather than focusing primarily on internal developments, researchers need to be particularly clear about how sustainable action is measured. An interesting observation during our literature review was that instead of measuring behavior directly, different operationalizations were used. Sometimes, self-reports of past, current, or intended future actions were considered reliable (Noortgaete and De Tavernier, 2014; Babutsidze and Chai, 2018). However, other authors, as cited by Brooks et al. (2013), considered self-reports to be invalid for measuring behavior. Newton and Meyer (2013) found a significant difference between measured behavioral intention (which some research has counted as “action”) and actual action. In their meta-analysis, Hertz and Krettenauer (2016) reported that studies based solely on self-reports yielded larger effect sizes. In summary, when empirical studies work with self-reported behavior and intentions, they are very likely to overestimate the effect of the respective variables on action.

After considering all the different theories and models which seek to explain the emergence of sustainable action and of the inner-outer gap, I see Krettenauer statement from 2019 is still current: the “‘silver bullet’ for bridging the judgment-action gap is not in sight yet […]” (p. 143). This statement has to be expanded on the other terms used in examining the “inner-outer-gap.” As if all models and concepts hold relevant thoughts, none of them on its own unfolds a predictive power that is convincing enough so that it would justify to build recommendations solely on it for educational purposes. In its complexity, the cited research seems fragmented and as an answer to our first research question: There is not a single evident model or concept that educators can use to help their students bridge the inner-outer gap.

If there is not a single model or theory that can be used, is it – following our second research question – possible to merge some of them into a useful concept?

5. Discussion and suggested new approach: Tripartite Structure of Sustainability

In situations where a universal theory does not provide a comprehensive solution, adopting a segmentation approach can hold significant promise (Anable et al., 2006). This method involves dividing a total population of individuals into distinct segments characterized by shared traits. It is conceivable that a specific treatment or educational strategy may effectively promote sustainable behavior within one segment while proving counterproductive for another. Within existing theories, the attempt to address all segments simultaneously might be what lead to inconsistencies and unreliable predictions. Segmenting a totality in a meaningful manner might enable researchers to develop nuanced hypotheses and educators to employ more precise and thus more effective strategies. The critical question here is whether there are already identifiable commonalities that warrant differentiation into certain segments. Rather than focusing on grouping people, this approach hinges on discerning distinctive patterns of intentions, attitudes, values, and judgments within the entirety of the data. These unique signatures can offer a foundation for generating reliable predictions related to sustainable actions.

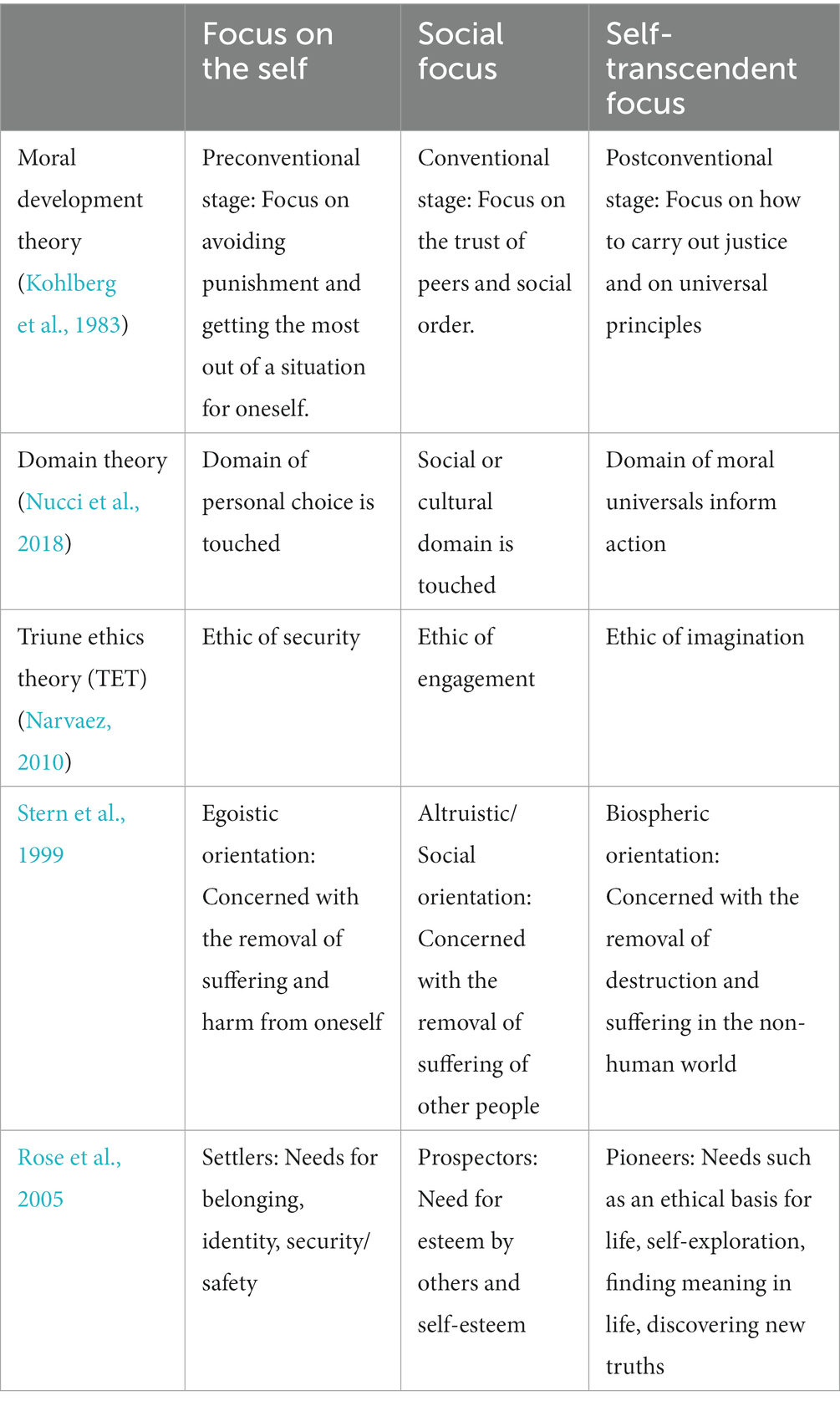

Whilst reading literature about the inner-outer gap, it became obvious to us that three reasons for engaging or not engaging in moral actions keep reappearing and could therefore be usefully adopted as segments. It segments an entirety of reasons for a certain choice which I call foci. Table 1 summarizes three theories that I have so far written about in this article, that support the thesis of common segments or foci and two additional ones – originating out of segmentation research – by Stern et al. (1999) and Rose et al. (2005). In our analysis, I identify distinct segments that are characterized by their primary focus. In the first focus, individuals predominantly prioritize their own interests, while in the second focus, their attention shifts towards their social environment. The third focus exhibits a self-transcendent perspective, where individuals feel responsible for a broader, altruistic cause that does not necessarily yield immediate personal or community benefits in daily life. This perspective was termed “self-transcendent,” borrowing from Stern’s Value-Belief-Norm-Model that refers to the Schwartz et al. (2012), to emphasize its contrast with self-centeredness.

The elaborated Tripartite Structure incorporates Kohlberg’s stages of moral development but goes beyond moral judgment. As in the Domain Theory, the foci can be seen as applying to the present moment and to complement or compete with each other. Consistent with research on moral automaticity, such as the Triune Ethics Theory (TET), it appears that actions are often automated and dependent on an individual’s emotional systems and brain architecture, which are influenced by personal history. The model also addresses three factors that are named by Klöckner’s CADM from left to right in the columns: self-enhancement values, social norms and self-transcendent values. To delve deeper into the distinctions between the three foci, one has to explore the concept of “self,” which is needed to explain at least the focus on the self and the self-transcendent focus. Frimer and Walker (2008) highlight the lack of consensus or even discussion regarding the definition of self in research about the moral self. They conclude that the notion of “self” may not be as stable as assumed, which has profound implications for the research field. Noortgaete and De Tavernier (2014) point out that social psychology conceptualizes interpersonal closeness through the extent to which a person includes another as part of himself – this then leads to more empathy and willingness to help. Going a step further, Robb et al. (2019) reported that nature could be experienced as part of one’s conception of identity. This integrated way of relating to the nonhuman world seems typical for indigenous communities (Wilson and Schellhammer, 2021). Encompassing nonhuman nature in one’s sense of identity appears to provide a way of overcoming dualism or alienation (Tam, 2013, p. 64) and according to Clayton (2003), encourages conservation behavior because the object of protection is tied to the self. Consequently, the motivation to act on nature’s behalf or on behalf of minorities becomes internal, rather than external. In regard to these notions of different authors I suspect that strictly speaking there is no shift in focus, because people always focus on themselves, but what they define/feel as self expands. The question would then be how they constitute their concept of self at a particular moment: If the concept is narrow/small, then it includes only their person; if it is wider, it includes conceptualized close “others” (Bertau and Tures, 2019). If the conception of self is very wide, it includes the whole living and non-living world. The distinction could therefore also be called the three stages of increasing I-Width or increasing width of awareness. Nevertheless, for the model I would like to stay with the terms of focus on self, social focus and self-transcendent focus as these terms are continuously referred in literature.

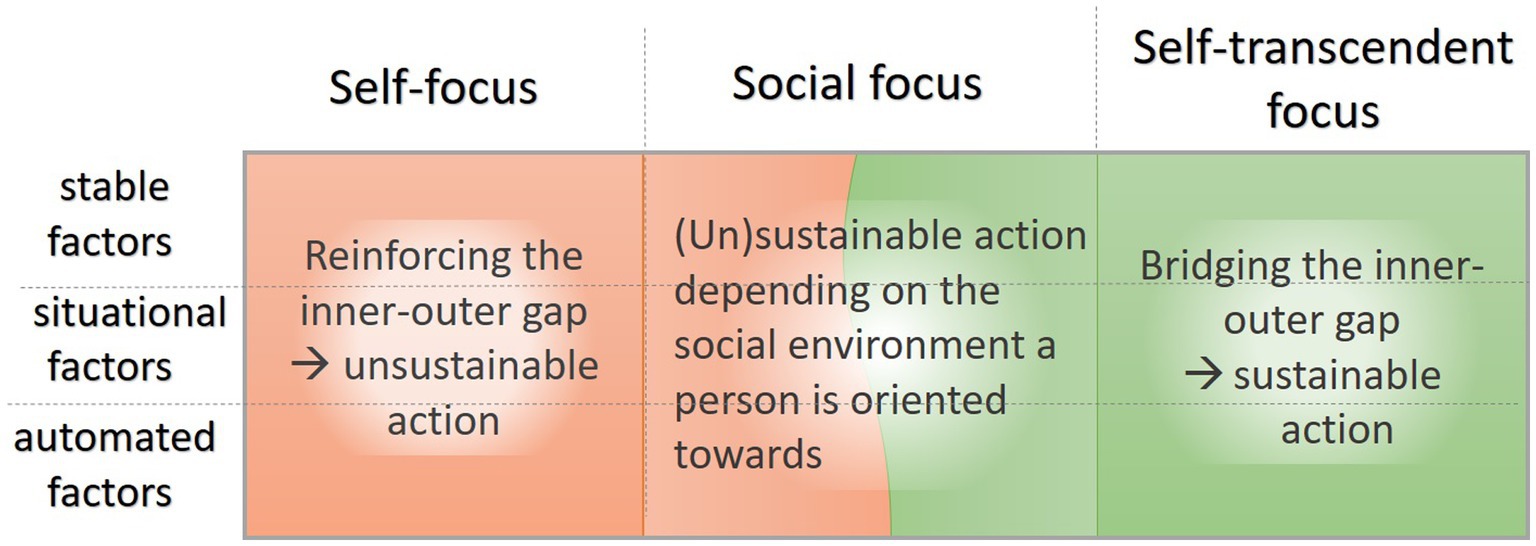

The notion of widening awareness is not only important for the discrimination in the model but also for education in general. Different authors hypothesized that the current formal education as well as the influence of scientific and economic frames of thought might make experience less immediately accessible, with the result of a weakened emotional bond between humans and nonhuman nature (Kopnina, 2012; Noortgaete and De Tavernier, 2014; Böhme et al., 2022). This may explain the considerably greater predictive power of an individual’s experience with the natural world when it occurs in childhood rather than in adulthood (Noortgaete and De Tavernier, 2014). If educators were to follow metamodernism, postcolonialism, or posthumanism, they would recognize that they all criticize the idea of objectivism and the possibility of observers seeing themselves outside the observed system (which is deeply rooted in the current educational system). Instead, they call for new paradigms that honor the intricate interconnectedness of living and non-living beings, the sense of being embedded in something larger than oneself, and the transcendence of experienced boundaries (Severan and Dempsey, 2021; Wilson and Schellhammer, 2021; Böhme et al., 2022). Not only indigenous communities describe this widened self as an important and more realistic way of being in the world but also modern scholars followed this impression (Böhme et al., 2022). Albert Einstein for example wrote in a letter, which was published in the New York Times on the 29th of March in 1972: “A human being is a part of the whole, called by us ‘Universe,’ a part limited in time and space. He experiences himself, his thoughts and feelings as something separated from the rest — a kind of optical delusion of his consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to affection for a few persons nearest to us. Our task must be to free ourselves from this prison by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole nature in its beauty.” The theories and empirical findings quoted here indicate that in terms of sustainable action, a self-transcendent focus is more likely to convert into sustainable action than the focus on the self or a social focus. The social focus seems to lead to sustainable action if the social surroundings are sustainable (see Figure 2). The tripartite structure of the different foci could therefore be a guide to help educators to embrace the new paradigm and operationalize what could be done to educate toward it.

But understanding why individuals act sustainably requires more than the three foci, and so I propose a second dimension for a model. While it can be presumed that whether the inner-outer gap is bridged is influenced by the focus an individual has, consciously or unconsciously, at the moment of action, it is not clear what activates that focus. According to the literature reviewed, there appear to be three categories of activation:

• stable factors inside a person (such as Kohlberg’s developmental stages or Blasi’s moral identity as well as values, norms and attitudes in the CADM),

• situational factors (see Domain Theory as well as awareness of consequence/responsibility and perceived behavioral control in the CADM), and/or

• automated/habitual factors inside a person that answer to the situation (see research on moral automaticity plus habit in the CADM, emotions such as of the climate crisis or moral disengagement would also fall in this category).

In total, the two dimensions collectively propose a dual three-folded arrangement, akin to a 3×3 grid, hereby referred to as the “Tripartite Structure of Sustainability.” This framework holds potential for delineating the extent to which individuals engage in sustainable behaviors, as illustrated in Figure 2. The adoption of this model could herald a novel paradigm in both research and education concerning sustainability. Moreover, this structural framework could serve as a valuable analytical tool, akin to Sunnemark et al. (2023). The latter, also structured as a 3×3 grid, distinguishes between the “holistic perspective” dimension (stages, actors, manuscript), and the “individual perspective” dimension (individual, social, and authoritative levels). While the content of these models differs, they share the utility to examine the causal factors contributing to specific actions. The relevance in regard to the inner-outer gap builds upon the insight of Domain Theorists who highlight the concurrent activation of multiple domains or foci in decision preparation. This approach prompts questions such as: Which stable foci influenced the decision-making process? What contextual factors did the situation offer and to which foci do they draw? And to what extent did automated factors play a role in shaping the outcome?

6. Conclusion

In summary, the research questions can be addressed as follows: A comprehensive literature review did not yield a single model or concept that consistently and reliably explains the inner-outer gap associated with sustainable action. This gap poses a challenge for educators seeking effective tools to assist their students towards wise and sustainable action. However, I found a promising approach to merge various theories through a segmentation framework, leading to the proposal of the “Tripartite Structure of Sustainability.” This model categorizes factors influencing the inner-outer gap into a 3×3 grid, based on an individual’s focus (self, social, or self-transcendent) and the triggers of these foci (stable, situational, automatic). There is a hypothesis that a self-transcendent focus may be more conducive to sustainable actions than self or social orientations. Additionally, sustainable behavior seems more likely when in the social focus the surroundings act sustainable. It is important to note that the relationship between the Tripartite Structure of Sustainability and sustainable action is still a hypothesis. Further investigation is carried out through a systematic literature review (Meyer et al., 2023, under review)1 to identify empirical factors bridging the inner-outer gap and their alignment with the proposed model. This model holds potential value for educators, offering a systematic framework to analyze how sustainable action arises in an individual and a way to guide educators to embrace the new paradigm. Researchers may also find it useful for designing more effective research methodologies, building upon the adopted segmentation approach.

If the hypothesis of influence on sustainable action is true, it would help teachers contribute to Dewey’s claim by increasing the skills and abilities of individuals “to act wisely and effectively in a great variety of occupations and situations,” and thereby raise the level of civilization that our societies reach (Dewey and Weber, 2021, p. 158). Acting wisely in this current state of the world means acting with foresight and compassion for fellow creatures and the planet as a whole. I hope that this article is a useful contribution to this endeavor. Finally, I pay tribute to and thank all the scientists whose work has been cited and all those who have been researching the inside-outside divide for centuries. The model presented stands on the shoulders of their research.

Author contributions

BM conducted the literature review, developed the Tripartite Structure of Sustainability and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1. ^Meyer, B., Gaertner, E., and Elting, C. (2023). Educating towards a new paradigm in sustainability. A systematic literature review testing the contribution of the Tripartite Structure of Sustainability. Under review.

References

Adnan, N., Nordin, S. M., Rahman, I., and Amini, M. H. (2017). A market modeling review study on predicting Malaysian consumer behavior towards widespread adoption of PHEV/EV. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 24, 17955–17975. doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-9153-8

Allen, M. W. (2016). “Understanding pro-environmental behavior: models and messages” in CSR, sustainability, ethics and governance. Strategic communication for sustainable organizations. ed. M. W. Allen (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 105–137.

Anable, J., Lane, B., and Kelay, T. (2006). An evidence base review of public attitudes to climate change and transport. London: UK Department for Transport.

Aquino, K., and Reed, A. (2002). The self-importance of moral identity. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 83, 1423–1440. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.6.1423

Babutsidze, Z., and Chai, A. (2018). Look at me saving the planet! The imitation of visible green behavior and its impact on the climate value-action gap. Ecol. Econ. 146, 290–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.10.017

Bennett, N., and Lemoine, G. J. (2014). What a difference a word makes: understanding threats to performance in a VUCA world. Bus. Horiz. 57, 311–317. doi: 10.1016/J.BUSHOR.2014.01.001

Bertau, M.-C., and Tures, A. (2019). Becoming professional through dialogical learning: how language activity shapes and (re-) organizes the dialogical self's voicings and positions. Learn. Cult. Soc. Interact. 20, 14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.lcsi.2017.10.005

Böhme, J., Zack, W., and Wamsler, C. (2022). Sustainable lifestyles: towards a relational approach. Sus. Sci. 17, 2063–2076. doi: 10.1007/s11625-022-01117-y

Biesta, G. (2009). Good education in an age of measurement: on the need to reconnect with the question of purpose in education. Educ. Assess. Eval. Account. 21, 33–46. doi: 10.1007/s11092-008-9064-9

Binder, M., and Blankenberg, A.-K. (2017). Green lifestyles and subjective well-being: more about self-image than actual behavior? J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 137, 304–323. doi: 10.1016/j.jebo.2017.03.009

Brooks, J., Bock, T., and Narvaez, D. (2013). Moral motivation, moral judgment, and antisocial behavior. J. Res. Character Educ. 9, 149–165.

Carrigan, M., and Attalla, A. (2001). The myth of the ethical consumer – do ethics matter in purchase behavior? J. Consum. Mark. 18, 560–578. doi: 10.1108/07363760110410263

Clayton, S. (2003). “Environmental Identity: A Conceptual and an Operational Definition” in Identity and the natural environment: The psychological significance of nature. ed. S. Clayton and S. Opotow MIT Press, 45–65.

Darnell, C., Gulliford, L., Kristjánsson, K., and Paris, P. (2019). Phronesis and the knowledge-action gap in moral psychology and moral education: a new synthesis? Hum. Dev. 62, 101–129. doi: 10.1159/000496136

DeTienne, K. B., Ellertson, C. F., Ingerson, M.-C., and Dudley, W. R. (2019). Moral development in business ethics: an examination and critique. J. Bus. Ethics 170, 429–448. doi: 10.1007/s10551-019-04351-0

Dewey, J., and Weber, E. T. (Eds.). (2021). America's public philosopher. New York City: Columbia University Press.

Dunlap, R. E., Van Liere, K. D., Mertig, A., and Jones, R. E. (2000). Measuring endorsement of the new ecological paradigm: A revised NEP scale. J. Soc. Issues. 56, 425–442. doi: 10.1111/0022-4537.00176

Fabian, M. C., Cook, A. S., and Old, J. M. (2020). Do Australians have the willingness to participate in wildlife conservation? Aust. Zool. 40, 575–584. doi: 10.7882/AZ.2019.010

Flynn, R., Bellaby, P., and Ricci, M. (2009). The ‘value-action gap’ in public attitudes towards sustainable energy: the case of hydrogen energy. Sociol. Rev. 57, 159–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-954X.2010.01891.x

Frederiks, E. R., Stenner, K., and Hobman, E. V. (2015). Household energy use: applying behavioral economics to understand consumer decision-making and behavior. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 41, 1385–1394. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2014.09.026

Frimer, J. A., and Walker, L. J. (2008). Towards a new paradigm of moral personhood. J. Moral Educ. 37, 333–356. doi: 10.1080/03057240802227494

Gao, J., Wang, J., and Wang, J. (2020). The impact of pro-environmental preference on consumers’ perceived well-being: the mediating role of self-determination need satisfaction. Sustainability 12:436. doi: 10.3390/SU12010436

Gigerenzer, G. (2008). “Moral intuition = fast and frugal heuristics?” in Moral psychology: the cognitive science of morality: Intuition and diversity. ed. W. Sinnott-Armstrong (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), 1–26.

Haidt, J. (2001). The emotional dog and its rational tail: a social intuitionist approach to moral judgment. Psychol. Rev. 108, 814–834. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.108.4.814

Hertz, S. G., and Krettenauer, T. (2016). Does moral identity effectively predict moral behavior? A meta analysis. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 20, 129–140. doi: 10.1037/gpr0000062

Jennings, P. L., Mitchell, M. S., and Hannah, S. T. (2015). The moral self: a review and integration of the literature. J. Organ. Behav. 36, S104–S168. doi: 10.1002/job.1919

Kam, C. D., and Palmer, C. L. (2008). Reconsidering the effects of education on political participation. J. Polit. 70, 612–631. doi: 10.1017/S0022381608080651

Klöckner, C. A. (2013). A comprehensive model of the psychology of environmental behavior—a meta-analysis. Glob. Environ. Chang. 23, 1028–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.05.014

Klöckner, C. A., and Blöbaum, A. (2010). A comprehensive action determination model: toward a broader understanding of ecological behavior using the example of travel mode choice. J. Environ. Psychol. 30, 574–586. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.03.001

Kohlberg, L., Levine, C., and Hewer, A. (1983). Moral stages: a current formulation and a response to critics. Contributions to human development. Basel: Karger.

Kopnina, H. (2012). The Lorax complex: deep ecology, ecocentrism and exclusion. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 9, 235–254. doi: 10.1080/1943815X.2012.742914

Krettenauer, T. (2019). The gappiness of the “gappiness problem”. Hum. Dev. 62, 142–145. doi: 10.1159/000496518

Kuhnhenn, K., Costa, L., Mahnke, E., Schneider, L., and Lange, S. (2020). A societal transformation scenario for staying below 1.5°C (Publication Series Economic and Social Issues No. 23). Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung, Berlin

Lane, B., and Potter, S. (2007). The adoption of cleaner vehicles in the UK: exploring the consumer attitude–action gap. J. Clean. Prod. 15, 1085–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2006.05.026

Lapsley, D. K., and Hill, P. L. (2008). On dual processing and heuristic approaches to moral cognition. J. Moral Educ. 37, 313–332. doi: 10.1080/03057240802227486

Li, D., Zhao, L., Ma, S., Shao, S., and Zhang, L. (2019). What influences an individual’s pro-environmental behavior? A literature review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 146, 28–34. doi: 10.1016/J.RESCONREC.2019.03.024

Moser, S., and Kleinhückelkotten, S. (2018). Good intents, but low impacts: diverging importance of motivational and socioeconomic determinants explaining pro-environmental behavior, energy use, and carbon footprint. Environ. Behav. 50, 626–656. doi: 10.1177/0013916517710685

Narvaez, D. (2008). Triune ethics: the neurobiological roots of our multiple moralities. New Ideas Psychol. 26, 95–119. doi: 10.1016/j.newideapsych.2007.07.008

Narvaez, D. (2009). Capturing the complexity of moral development and education. Mind Brain Educ. 3, 151–159.

Narvaez, D. (2010). “Triune ethics theory and moral personality” in Personality, identity, and character: explorations in moral psychology. eds. D. Narváez and D. K. Lapsley (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 136–158.

Narvaez, D., and Lapsley, D. K. (2005). “The psychological foundations of everyday morality and moral expertise” in Character psychology and character education. eds. D. K. Lapsley and F. C. Power (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press), 140–165.

Newton, P., and Meyer, D. (2013). Exploring the attitudes-action gap in household resource consumption: does “environmental lifestyle” segmentation align with consumer behavior? Sustainability 5, 1211–1233. doi: 10.3390/su5031211

Noortgaete, F., and De Tavernier, J. (2014). Affected by nature: a hermeneutical transformation of environmental ethics. Zygon, 49:, 572–592, doi: 10.1111/zygo.12103

Nucci, L. (1997). Culture, universals, and the personal. New Dir. Child Dev. 1997, 5–22. doi: 10.1002/cd.23219977603

Nucci, L., and Turiel, E. (2009). Capturing the complexity of moral development and education. Mind Brain Edu. 3, 151–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-228X.2009.01065.x

Nucci, L., Turiel, E., and Roded, A. D. (2018). Continuities and discontinuities in the development of moral judgments. Hum. Dev. 60, 279–341. doi: 10.1159/000484067

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development . (2016). Education indicators in focus (vol. 47) Paris: OECD

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development . (2017). Health at a glance 2017: OECD indicators. Paris: OECD

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development . (2020). Education indicators in focus (vol. 75). Paris: OECD

Osunmuyiwa, O. O., Payne, S. R., Vigneswara Ilavarasan, P., Peacock, A. D., and Jenkins, D. P. (2020). I cannot live without air conditioning! The role of identity, values and situational factors on cooling consumption patterns in India. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 69:101634. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2020.101634

Panda, T. K., Kumar, A., Jakhar, S., Luthra, S., Garza-Reyes, J. A., Kazancoglu, I., et al. (2020). Social and environmental sustainability model on consumers’ altruism, green purchase intention, green brand loyalty and evangelism. J. Clean. Prod. 243:118575. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.118575

Parth, S., Schickl, M., Keller, L., and Stoetter, J. (2020). Quality child–parent relationships and their impact on intergenerational learning and multiplier effects in climate change education: are we bridging the knowledge–action gap? Sustainability 12, 1–16. doi: 10.3390/su12177030

de Pelsmacker, P., Driesen, L., and Rayp, G. (2005). Do consumers care about ethics? Willingness to pay for fair-trade coffee. J. Consum. Aff. 39, 363–385. doi: 10.1111/J.1745-6606.2005.00019.X

Rest, J. R., Narvaez, D., Thoma, S. J., and Bebeau, M. J. (1999). DIT2: devising and testing a revised instrument of moral judgment. J. Educ. Psychol. 91, 644–659. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.91.4.644

Robb, J., Haggar, J., Lamboll, R., and Castellanos, E. (2019). Exploring the value–action gap through shared values, capabilities and deforestation behaviors in Guatemala. Environ. Conserv. 46, 226–233. doi: 10.1017/S0376892919000067

Rose, C., Dade, P., Gallie, N., and Scott, J. (2005): Climate change communications– dipping a toe into public motivation. Campaign Strategy, London.

Schwartz, S. H., Cieciuch, J., Vecchione, M., Davidov, E., Fischer, R., Beierlein, C., et al. (2012). Refining the theory of basic individual values. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 103, 663–688. doi: 10.1037/a0029393

Severan, A., and Dempsey, B.G. (2021) Metamodernism and the return of transcendence. Chicago, IL: Independently published.

Stephens, J. M. (2018). Bridging the divide: the role of motivation and self-regulation in explaining the judgment-action gap related to academic dishonesty. Front. Psychol. 9:246. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00246

Stern, P. (2000). Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 56, 407–424. doi: 10.1111/0022-4537.00175

Stern, P. C., Dietz, T., Abel, T., Guagnano, G. A., and Kalof, L. (1999). A value belief-norm theory of support for social movements: the case of environmentalism. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 6, 81–97.

Sunnemark, F., Gahnström, E., Rudström, H., and Karlsson, E. (2023). Social sustainability for whom? Developing an analytical approach through a tripartite collaboration. J. Work. Learn. 35, 524–539. doi: 10.1108/JWL-01-2023-0004

Sunstein, C. R. (2005). Moral heuristics. Behav. Brain Sci. 28, 531–542. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X05000099

Sweeney, P. J., Imboden, M. W., and Hannah, S. T. (2015). Building moral strength: bridging the moral judgment-action gap. New Dir. Stud. Leadersh. 2015, 17–33. doi: 10.1002/yd.20132

Tam, K.-P. (2013). Concepts and measures related to connection to nature: similarities and differences. J. Environ. Psychol. 34, 64–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2013.01.004

Turiel, E. (2006). “The development of morality” in Handbook of child psychology. eds. W. Damon and R. M. Lerner. 6th ed (New York: John Wiley & Sons), 789–857.

Keywords: Education for Sustainable Development (ESD), literature review, judgement-action gap, value-action gap, attitude-action gap, knowledge-action gap, intention-action gap, Tripartite Structure of Sustainability

Citation: Meyer BE (2023) The Tripartite Structure of Sustainability: a new educational approach to bridge the gap to wise and sustainable action. Front. Educ. 8:1224303. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1224303

Edited by:

Douglas F. Kauffman, Medical University of the Americas – Nevis, United StatesReviewed by:

Kelsie Dawson, Maine Mathematics and Science Alliance, United StatesAlfonso Garcia De La Vega, Autonomous University of Madrid, Spain

Copyright © 2023 Meyer. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Barbara E. Meyer, bWFpbEBiYXJiYXJhLWUtbWV5ZXIuZGU=

†ORCID: Barbara E. Meyer, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7958-2186

Barbara E. Meyer

Barbara E. Meyer