- 1Department of Education Science, University of Regensburg, Regensburg, Germany

- 2Pädagogische Hochschule Vorarlberg, Feldkirch, Austria

- 3Department of Education Science, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich, Germany

Organizing lessons for heterogeneous learning groups is a challenge for student teachers and novice teachers. To observe and improve classroom management during student teaching, we have developed an assessment tool. The aim of this study is to evaluate and improve the instrument “Scale for Classroom Management in Inclusive Schools (InClass)” with data from 480 student teachers in internships at elementary or special schools in Germany and Austria. The instrument consists of the three dimensions Adaptive Teaching Scale (ATS), Relationship Scale (RS), Behavior Management Scale (BMS). Confirmatory factor analyses revealed good reliable values (CFI = 0.97, TLI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.04) for the three-factor InClass model and could confirm the theoretically developed scales. The latent correlations were between r = 0.74 and r = 0.63. Teachers in elementary schools also showed latent correlations between the three dimensions and their assessment of the implementation of inclusive education in the school ranging from r = 0.51 to r = 0.84. In order to meet the individual needs of all students, with and without special educational needs (SEN), novice teachers in particular should be supported in dealing with heterogeneous learning groups and in using effective classroom management. Instruments such as InClass help student teachers evaluate and reflect on instruction and therefore have an important contribution to teacher education.

1 Introduction

Since the entry into force of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD, United Nations, 2006), many European countries have revised their education laws, regulations, and targets to promote inclusive education. Every school must be well prepared to provide access to effective education for all children, especially those with special educational needs (SEN). Students with SEN need to be individually and effectively supported to maximize their academic and social development. Both practicing and prospective teachers should have extensive knowledge of special teaching strategies that can be adapted to students’ learning needs and improve their academic performance (Krämer et al., 2021; European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, 2022). However, inclusive education is more than just effective teaching, as it must always include social concepts of disability and special educational needs (Gebhardt et al., 2022). Therefore, it is essential to question to what extent inclusive education differs from regular education (Hornby, 2014). Recognizing the heterogeneity and diversity of individuals within a group is crucial in any pedagogical approach.

Since classroom management is a crucial factor in good teaching and in creating a positive classroom climate, could it not also be essential for inclusion? It serves the goals of inclusion and participation (Soodak and McCarthy, 2006). By fostering a conducive learning environment, classroom management effectively supports students in excelling both academically and socially (Korpershoek et al., 2016; Lane et al., 2022). If all students’ personality development and specific learning requirements are taken into account, classroom management is a priori inclusive (Frey, 2021). Hence, we should view the concept of classroom management through an inclusive lens.

2 Defining concepts of classroom management

There are varying concepts of classroom management. Evertson and Weinstein (2006) define classroom management as “the actions teachers take to create an environment that supports and facilitates both academic and social–emotional learning” (Evertson and Weinstein, 2006 p. 4). Emmer and Sabornie (2015) incorporate different perspectives in their interpretation: “Classroom management is clearly about establishing and maintaining order in a group-based educational system whose goals include student learning as well as social and emotional growth. It also includes actions and strategies that prevent, correct, and redirect inappropriate student behavior” (Emmer and Sabornie, 2015 p. 8).

The key components of effective classroom management are evident in these definitions: maximizing instructional time, organizing classroom activities to enhance academic achievement, and utilizing proactive behavior management strategies (Simonsen et al., 2008; Scott and Nakamura, 2022). These defining components are not static, but have been widely accepted across multiple research traditions (Emmer and Sabornie, 2015). Depending on the approach or concept, there is a different focus on the components. While Scott and Nakamura (2022) highlight the importance of effective instruction, Marzano and Marzano (2003) emphasize that the teacher-student relationship is an essential foundation for effective classroom management. With their focus on classroom management in technology-rich classrooms, Johler et al. (2022) also confirmed the critical importance of leadership, good teacher-student relationships, and teacher adaptability in taking on the role of a learner. Effective approaches to classroom management are characterized by a focus on proactive, preventive procedures rather than reactive ones (Korpershoek et al., 2016). Although the various concepts have different focuses on the three components, they all contain them. There is currently no approach that places particular emphasis on an inclusive perspective.

Several assessment tools have been established for classroom management: the Linz Classroom Leadership Diagnostic Questionnaire [“Linzer Diagnosebogen zur Klassenführung” (LDK), Mayr et al., 2018], the Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS, Pianta et al., 2008), the Questionnaire on Instructional Behaviour (QIB, Perry et al., 2006), and the Classroom Management Self Efficacy Instrument (CMSEI, Slater and Main, 2020). The Linz Questionnaire LDK is commonly used in educational research in German-speaking countries (Krammer et al., 2021) and available for free use in practice. Therefore, we provide a detailed overview of this questionnaire. LDK is designed for students, teachers, and interns to evaluate classroom management, specifically at the elementary and secondary levels. 24 classroom management strategies are essential to the Linz concept of classroom leadership, also referred to as the “Linzer Konzept der Klassenführung” (LKK). Its strategies include displaying empathetic understanding, rapid intervention in the event of classroom disruptions, and clear structuring of lessons. These strategies can be grouped into categories or three higher-order factors that concentrate on teacher actions, competencies, and attitudes that contribute to stimulating student learning, minimizing classroom disruptions, and shaping students’ attitudes toward the teacher and the subject (Mayr et al., 2021). The factors are instructional clarity, teacher-student relationship and performance monitoring (Krammer et al., 2021). The LDK questionnaire is designed for both student teachers and experienced educators seeking to gain clarity on their pedagogical actions in the classroom or in relation to a specific subject. It prompts the respondent to primarily assess the lesson, with only a few questions about the class or students.

3 Classroom management in heterogeneous classes

To address the growing diversity of students, it is crucial for teachers to effectively meet the individual needs of each student and differentiate their instruction. According to Pozas et al. (2020), teachers currently view their teaching as more group-oriented and less focused on individual students. Although many regular school teachers have positive attitudes towards inclusion, they are very concerned about its implementation (Miesera et al., 2018). They have concerns that they do not have sufficient knowledge and skills to take responsibility in heterogeneous classrooms, especially for students with SEN, because they were not adequately prepared for this in their basic teacher training (Pijl, 2010). In most cases, however, research shows that it is not the resources or the severity of the disability that matters, but the teacher’s attitudes and the learned pedagogical action patterns (Soodak et al., 1998; Buchner and Gebhardt, 2011; Gebhardt, 2018).

Effective classroom management has a positive effect on social acceptance in the classroom (Garrote et al., 2020). A positive classroom behavioral climate is a necessary prerequisite for the successful implementation of inclusion (Hoffmann et al., 2021). The well-being of the students not only depends on how the teachers shape the relationships and the values they bring with them, but also on the prevailing values in the school as a whole (Serke, 2019). As for the classroom situation, this means that teachers show an inclusive attitude and have the confidence to provide individualized support to heterogeneous learning groups. It would be negative if the teacher rejected people with disabilities or treated everyone alike without paying attention to the individual learning requirements. Children with SEN may, at first glance, appear to place an additional burden on regular teachers and exhibit challenging behavioral patterns, but, in inclusive education, all individuals are entitled to well-prepared inclusive teaching, well-designed classroom management strategies and practices. This is beneficial for all students, but especially for students with SEN (Lane et al., 2006).

We recognized the need for an instrument that considers inclusion and participation in university teaching, supervised internships, and pedagogical practice. To address this, we developed the “Scale for Classroom Management in Inclusive Schools (InClass)” (Lutz et al., 2023). While our instrument builds on the categories of the LDK (Krammer et al., 2021), it additionally focuses on the heterogeneity of students. The aim is to support the development of the personality and the learning process of all students, taking into account their specific needs. Although we mainly refer to students with and without SEN in the following sections, InClass can also be used when there is a broader concept of inclusion. In this context, inclusion is often applied to address learners with different heterogeneity characteristics such as multilingualism or special needs (Rank and Frey, 2021).

When designing InClass, we ensured that the questionnaire considers a broader inclusive and participatory perspective that takes into account the heterogeneity characteristics of all students and the working methods in inclusive education (Schurig et al., 2020). Therefore, several experts in the field of inclusive and special education were involved in the development of the item pool. In addition to the LDK, key concepts and principles of inclusion were used in the item development process. The different items emphasize the importance of addressing the needs of all learners and the individual needs of some to ensure quality education, as recommended by European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2022). Core values of the Profile for Inclusive Teachers include valuing learner diversity and supporting all learners to promote the academic, practical, social, and emotional learning of all learners (Evertson and Weinstein, 2006; European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, 2012). This means, for example, creating a barrier-free learning environment that is understandable to everyone, adopting a positive and appreciative attitude toward students, and providing optimal support for their learning.

InClass integrates the three well-established components of classroom management, namely engaging students in their learning activities, creating a productive classroom climate by building positive relationships, and preventing classroom disruptions in order to maximize instructional time (Emmer and Sabornie, 2015). In accordance with these components, the names of the scales are as follows: Adaptive Teaching Scale (ATS), Relationship Scale (RS) and Behavior Management Scale (BMS). The Adaptive Teaching Scale (ATS) centers on how teaching staff adapt their teaching to the heterogeneity of the students. The Relationship Scale (RS) focuses in equal measure on developing and strengthening both the teacher-student and the student–student relationships. The Behavior Management Scale (BMS) aims to prevent classroom disruptions in order to maximize the individual learning time of all students. InClass exists in two versions. One is for external observation [InKlass-F, “Fremdbeobachtung” (Lutz et al., 2022a)], and the other is for self-assessment [InKlass-S, “Selbsteinschätzung” (Lutz et al., 2022b)]. The items in both versions do not differ in content. In this paper, we only consider the scale for external assessment, namely that student teachers assess the classroom management of the teaching staff after having completed their internship and receive feedback in the form of the mean of the responses to the three scales, ATS, RS, and BMS. For self-assessment purposes to improve their own teaching, student teachers or teaching staff can use the self-assessment version of InClass.

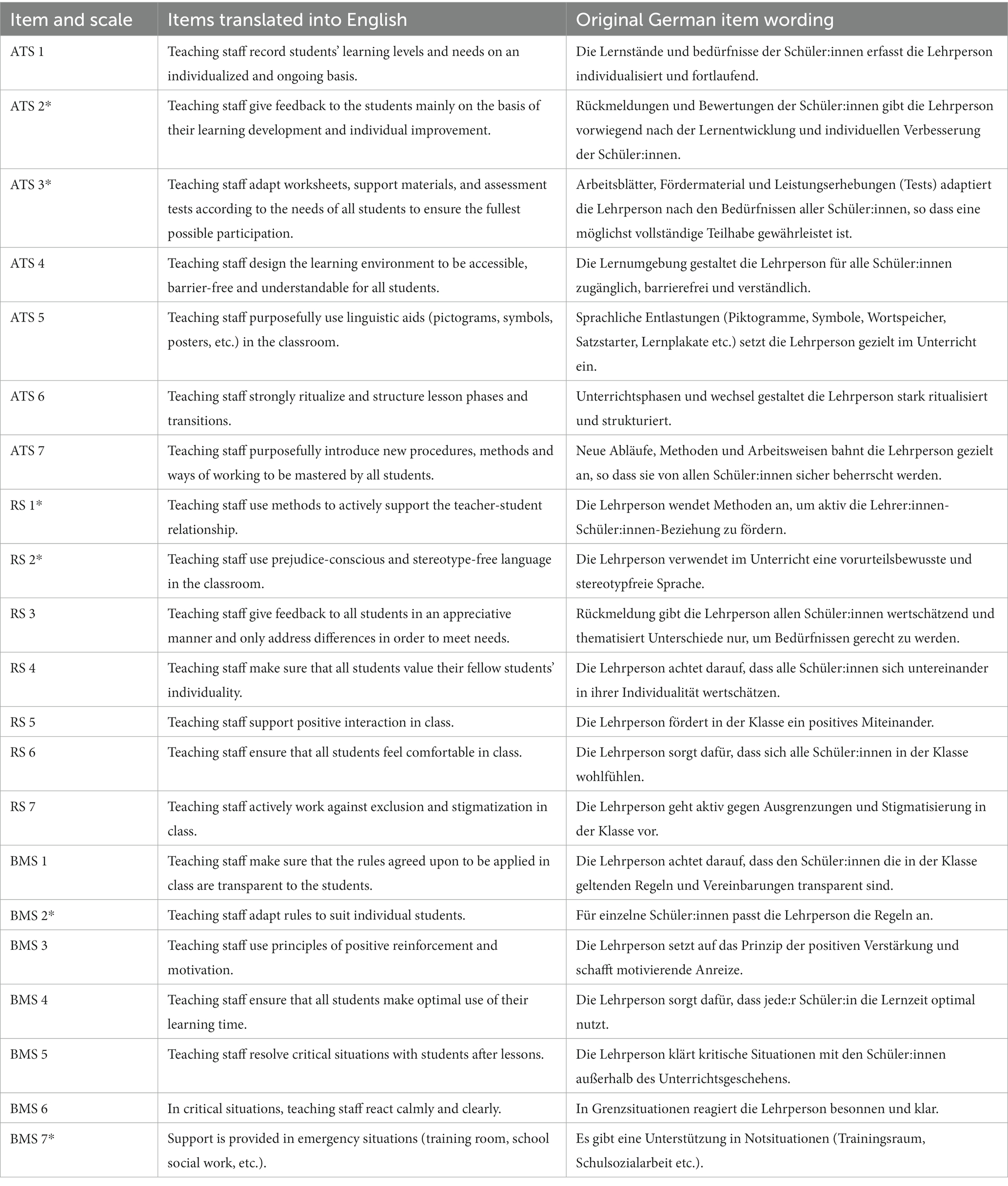

In order to incorporate an inclusive perspective and to meet the individual needs and learning requirements of all students, the Adaptive Teaching Scale (ATS) includes the following elements: record of the students’ learning levels, feedback to the students on the basis of their learning development and individual improvement, adaption of support materials, design of an accessible, barrier-free, and understandable learning environment, use of linguistic aids and strongly ritualized and structured lesson phases, introduction of new procedures and ways of working to be mastered by all students. The Relationship Scale (RS) focuses on methods of actively supporting the teacher-student relationship, using a nonjudgmental and nonstereotypical language in the classroom, giving appreciative feedback, valuing students’ individuality, promoting positive interaction and a sense of well-being in the classroom, and actively working against exclusion and stigmatization in class. The Behavior Management Scale (BMS) includes items on maximizing the learning time through transparent rules, adapting rules to suit the individual student, using principles of positive reinforcement and motivation, ensuring optimal use of student learning time, resolving critical situations with students after class, reacting calmly and clearly in critical situations, and providing support in emergency situations. Not every item on the scales is explicitly worded at the individual level. The wording of an item either emphasizes the individual focus or highlights a class-level assessment that refers to all students in the class. An overview of the InClass items is given in Table 1.

A fourth scale with five items was developed in order to additionally assess how inclusion is implemented at the respective school. This Inclusion Scale (INK) contains various statements about the importance of inclusion at the school and how it has already been incorporated into the school concepts. The individual items are listed in Table 2.

4 Research questions

The purpose of the internship in the study program is to allow student teachers to gain hands-on teaching experience and to recognize the qualities of good inclusive teaching. We have developed the InClass assessment tool so that such teaching can be observed systematically and discussed in the accompanying course. InClass can be instrumental in this process by helping to raise awareness of classroom management in heterogeneous classrooms and focusing attention on the necessary teacher behaviors and competencies. As there is no instrument available that combines classroom management with a focus on inclusion, we developed an instrument under CC BY license that considers the different components of classroom management and also adopts an inclusive perspective and meets the needs and learning requirements of all students.

In Germany and Austria, all teacher education programs include courses in education, instruction and didactics, and psychology, as well as several internships at different types of schools. It can be assumed that all student teachers have the same prerequisites in regard to internships, since internships are part of university education in all disciplines. This provides a level playing field for the assessments, which makes it possible to evaluate the various InClass scales. Encouraging student teachers to anonymously evaluate teachers’ classroom management at the end of their internship can reveal difficulties, for example, in understanding the items. The assessment of student teachers is of particular interest because the study by Weber and Greiner (2019) showed that, in terms of perceived challenges during an internship, classroom management is the most important task that pre-service teachers face during their first teaching internship.

School systems vary from country to country. Since special education schools or separate classes exist in some countries and are likely to be maintained at a low percentage, we decided to apply the instrument in elementary and special schools to measure its reliability in different school settings. We were intent on investigating whether there were differences in student teachers’ assessments depending on the type of school in which their internship took place.

The following research questions can be specified:

• Q1: Does InClass measure three latent factors that correspond to the three scales of classroom management?

• Q2: Do the three scales have acceptable fit in confirmatory factor analysis?

• Q3: Are there differences in the assessment of classroom management by the student teachers in relation to the school type in which their internship took place?

5 Methods

5.1 Procedure

Teacher education programs in Germany and Austria include several internships in different types of schools as well as courses in education, instruction and didactics. It can be assumed that all student teachers have the same prerequisites in regard to internships, since internships are part of the university education in all disciplines. Therefore, it was assumed that all student teachers who wished to participate in the study would be able to complete InClass and to evaluate the classroom management of the teaching staff they observed in their internships. After finishing InClass, student teachers receive feedback in the form of the mean of the responses to the three scales, ATS, RS, and BMS.

Using the InClass instrument, student teachers at various universities in Germany and Austria were asked to anonymously assess the classroom management of the teaching staff in the internships they had completed. For this purpose, they were invited in regular courses such as pedagogy seminars and through open invitations from April to June 2023, with their participation being recommended but voluntary. The survey was conducted using SoSciSurvey software.

5.2 Instruments

In the study, student teachers were asked about their place of study, field and semester of study, and gender. In addition, student teachers were invited to provide information about the type of school where their internship took place. They were never asked to reveal the location of the school or the names of the teachers evaluated.

The instrument used in this study was the German version of InClass, namely the “Skala zur inklusiven Klassenführung (InKlass-F)” (Lutz et al., 2022a). The InClass assessment tool consists of three scales with seven items each. The scales were formulated according to the essential components of classroom management and adapted to inclusive education. The items of the three scales [Adaptive Teaching Scale (ATS), Relationship Scale (RS), Behavior Management Scale (BMS)] are presented in Table 1. English translations of the items are provided for illustrative purposes. Only German items were subjected to empirical analysis. Responses were collected on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = “does not apply” to 5 = “always true/daily”.

The student teachers who completed internships in elementary school were asked to estimate the implementation of inclusion with five items, because an elementary school implements inclusive education very differently. The items on the Inclusion Scale (INK) were assessed using an identical Likert scale and are further presented in Table 2.

5.3 Results of the pilot study

During a pilot phase, student teachers in their internships (N = 79) from Southern Germany and Western Austria evaluated InClass. The internal consistency of the three scales was satisfying, with Cronbach’s alpha for the Adaptive Teaching Scale αATS = 0.83, for the Relationship Scale αRS = 0.85 and for the Behavior Management Scale αBMS = 0.78. Pearson’s correlation showed a significant, positive relationship between all three scales measured, with the lowest correlation between ATS and RS being r = 0.63 (p < 0.001) and the highest correlation between RS and BMS being r = 0.73 (p < 0.001). The initial results suggest that InClass is an instrument that measures the three dimensions of classroom management economically, reliably, and validly. The items were not changed after the pilot phase.

5.4 Participants

A total of 480 student teachers (89% female and 11% male), 71 student teachers from the Austrian state of Vorarlberg (15%) and 409 student teachers from two German states (36% Bavaria, 50% Thuringia), participated, all of whom assessed a previously completed internship. Of those participating, 141 studied special education and 332 elementary education. The largest group of student teachers (250) was in their first two semesters, 138 were in semesters 3 to 6, and 92 had studied more than six semesters.

5.5 Analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to confirm the three-factor structure of InClass. The three classroom management scales were operationalized as a multidimensional confirmatory factor model. Items were presented digitally and in a fixed order. Student teachers were asked to rate the statements. Student teachers who completed an elementary school internship were also asked to assess the degree of inclusion implementation. Therefore, another confirmatory factor analysis was conducted for a four-factor model of the InClass Scales with Inclusion Scale (INK).

The structural equation models were computed using lavaan (Rosseel, 2012) in R. A robust maximum likelihood estimator was used. To assess the fit of the data to the CFA, several model fit indices were consulted. Besides χ2 and its associated degrees of freedom (df), several sample-size-independent fit indices such as the comparative fit index (CFI), the standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) were evaluated. CFI and TLI values >0.95 indicate an adequate fit of the data to the theoretical model. In addition, RMSEA values <0.06 and SRMR values <0.08 were suggested by Hu and Bentler (1999) as good cutoff values.

6 Results

6.1 Confirmatory factor analysis

Since classroom management consists of three main components, InClass was designed with three dimensions, similar to the LDK role model instrument or other classroom management models. The test statistics with seven items per scale yielded the following results: χ2(185) = 525.83, p ≤ 0.001 (χ2/df ratio = 2.84). The robust CFI (0.92) and TLI (0.91) are slightly acceptable (> 0.95), as is the robust RMSEA (0.07). The SRMR (0.05) is acceptable. The measures of internal consistency are αATS = 0.87, αRS = 0.90, αBMS = 0.78, which means that the individual scales have good reliability in terms of internal consistency. The standardized factor loadings range from 0.39 to 0.87 (ATS: 0.68 ≤ λ ≤ 0.76; RS: 0.60 ≤ λ ≤ 0.87; BMS: 0.39 ≤ λ ≤ 0.75).

The scales were shortened by two items each to obtain better fit values. A shorter and empirically more similar scale was found in the five-point scale. Therefore, the best theoretical and empirical items from the seven-item scales were selected.

The following items were dropped: Item ATS 2 was excluded due to its wording, which includes “giving feedback to the student,” making it very similar to item RS 3. In addition, for item ATS 3 it can be assumed that the addition “to ensure the fullest possible participation” in the item wording may have led to too little selectivity with regard to the Relationship Scale. Items RS 1 and RS 2 were also removed. While item RS 1 focuses on a too general and not very concrete implementation of relationship support, item RS 2 dwells mainly on language and less on building a positive relationship. Items BMS 2 and BMS 7 were also deleted, as both the individual adaptation of rules and the support provided in emergency situations are not sufficiently seen by student teachers in internships and therefore cannot be adequately assessed.

For better model fit, correlations between two items were allowed, as the items use remarkably similar words or target the same aspects. Items ATS 6 and ATS 7 are aimed at the structure and established procedures in the classroom.

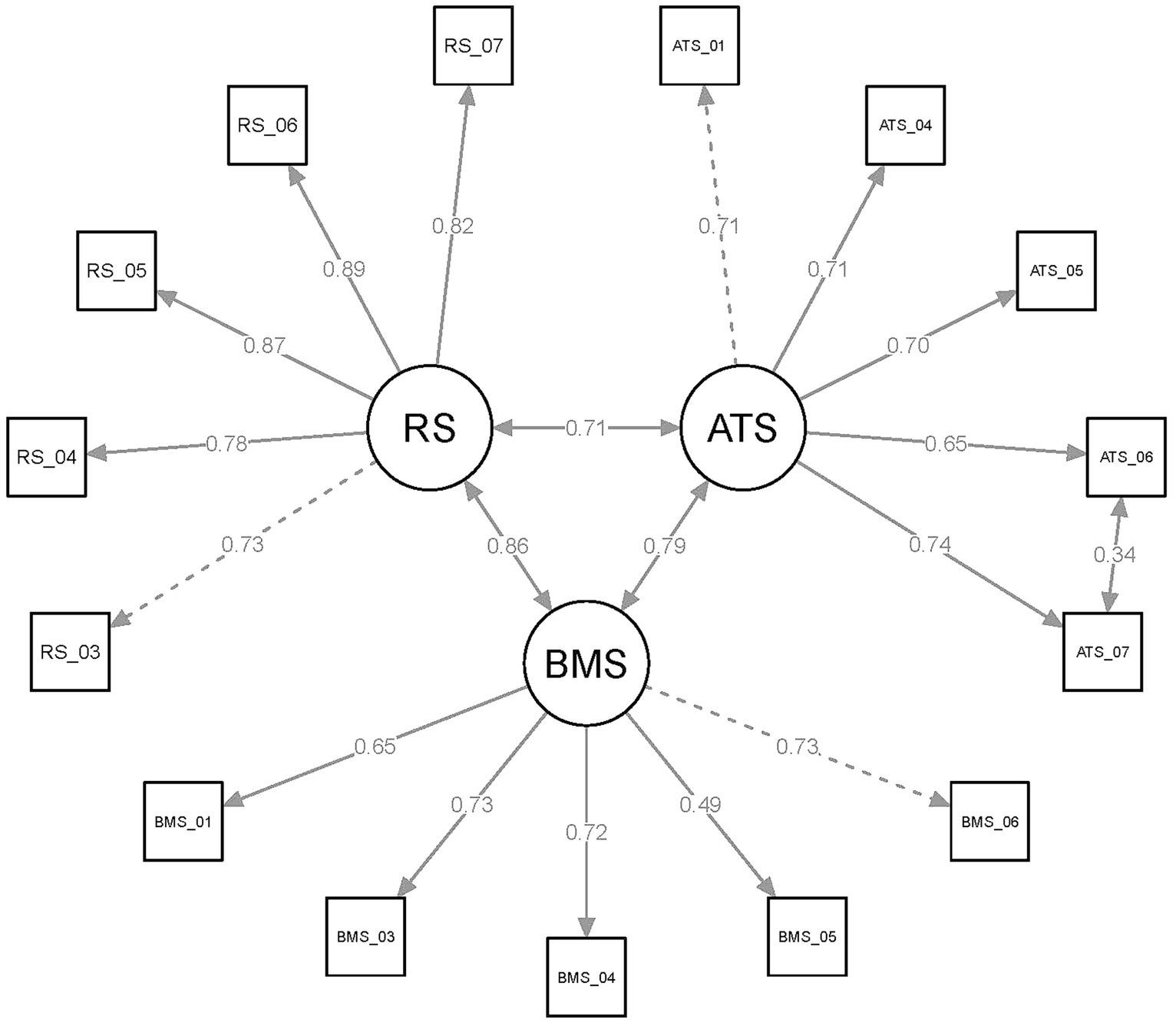

The test statistics with five items per scale showed an acceptable statistic χ2(86) = 186.37, p ≤ 0.001 (χ2/df ratio = 2.17). For a three-dimensional model, the robust CFI (0.97) and TLI (0.96) are acceptable (> 0.95), while the robust RMSEA (0.06) and SRMR (0.04) remain good. The measures of internal consistency are αATS = 0.84, αRS = 0.91, αBMS = 0.79, meaning that the individual scales have good reliability in terms of internal consistency. As can be seen in Figure 1, the standardized factor loadings indicate an adequate model fit to the empirical data as the standardized factor loadings range from 0.49 to 0.89 (ATS: 0.65 ≤ λ ≤ 0.74; RS: 0.73 ≤ λ ≤ 0.89; BMS: 0.49 ≤ λ ≤ 0.73). A one-dimensional model (robust CFI = 0.81 and TLI = 0.77) and a two-dimensional model (robust CFI = 0.94 and TLI = 0.93) were also calculated, which had poorer fit values. The CFA results confirm a three-factor structure of InClass. All latent correlations were significant (p <.01) and positive. Within the scales, RS was most strongly 300 related to BMS (r =.74). The correlations between ATS and RS and between ATS and BMS were 301 r =.63.

Figure 1. Confirmatory factor analysis of the three-factor-model of the InClass scales (special and elementary schools).

6.2 Mean score comparisons

In all three scales, student teachers who assessed teachers in special education schools (MATS = 4.2, SD ATS = 0.6; MRS = 4.3, SD RS = 0.7; MBMS = 4.2, SD BMS = 0.7) rated them higher than student teachers who assessed teachers in elementary schools (MATS = 3.8, SD ATS = 0.8; MRS = 4.1, SD RS = 0.8; MBMS = 3.9, SD BMS = 0.7). There is a significant effect of the assessed school type on ATS, F (1, 478) = 34.1, p < 0.001, on BMS, F (1, 478) = 9.7, p = 0.002, and on RS, F (1, 478) = 8.7, p = 0.003.

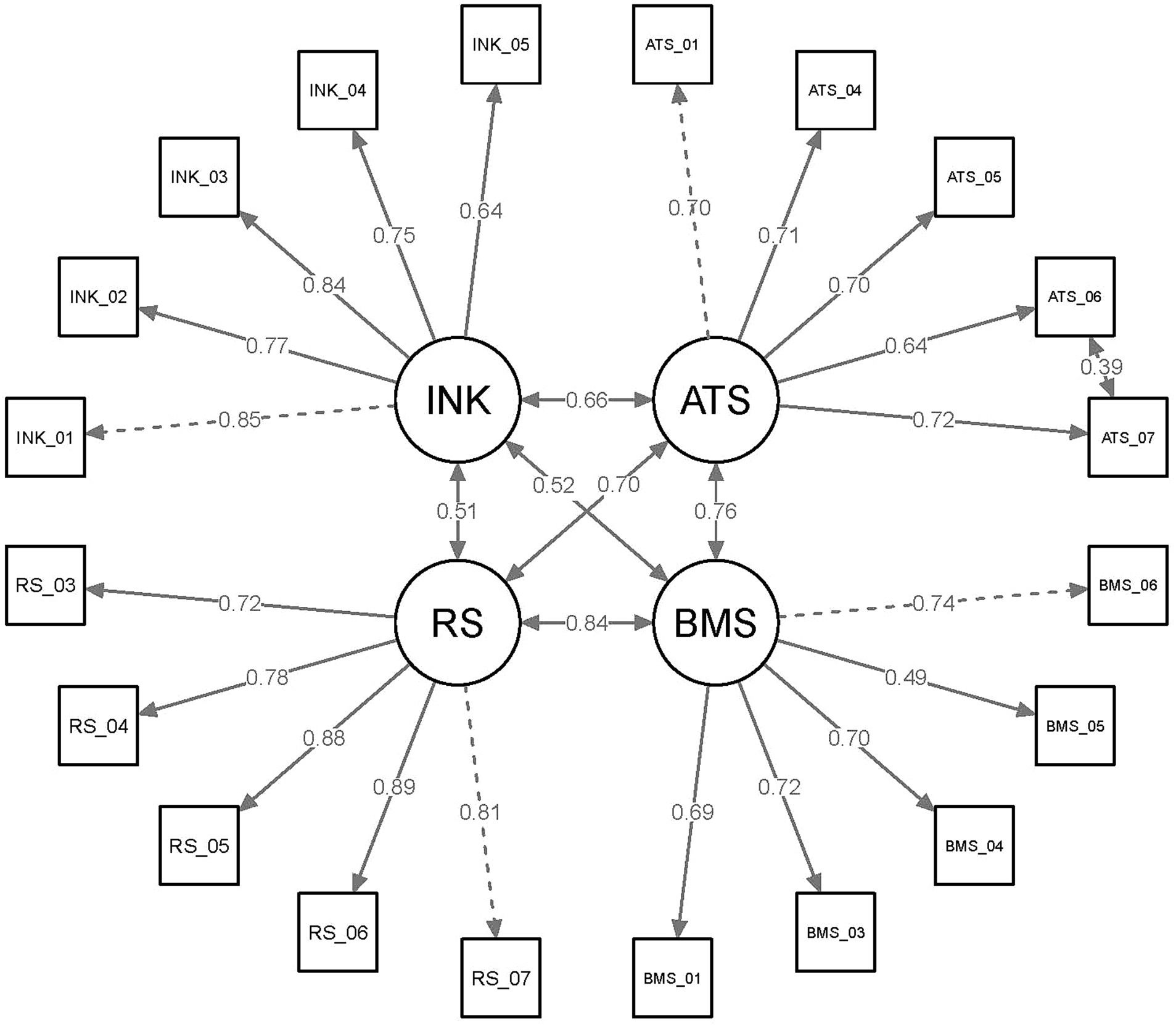

6.3 Confirmatory factor analysis – elementary school

The 366 student teachers who completed an elementary school internship were presented with five items asking them to assess the implementation of inclusive education (see Table 2).

The internal consistency of the Inclusion Scale (INK) was satisfactory (αINK = 0.88, item whole correlation between 0.64 and 0.85), so that a separate model was only calculated for the elementary school. The test statistic showed an acceptable statistic χ2(163) = 404.17, p ≤ 0.001 (χ2/df ratio = 2.48). However, the psychometric values are slightly worse than the recommended limits. The values for robust CFI (0.93) and TLI (0.92) are too low. The value for RMSEA (0.07) is too high, while the SRMR (0.06) remains stable and good. The internal consistency measures were αATS = 0.84, αRS = 0.91, αBMS = 0.80, αINK = 0.88, which means that the individual scales have good reliable values in terms of internal consistency. As can be seen in Figure 2, the standardized factor loadings are quite similar to the standardized factor loadings in Figure 1, which also indicates an adequate model fit to the empirical data. The standardized factor loadings range from 0.49 to 0.89 (ATS: 0.64 ≤ λ ≤ 0.72; RS: 0.72 ≤ λ ≤ 0.89; BMS: 0.49 ≤ λ ≤ 0.74, INK: 0.64 ≤ λ ≤ 0.85). All latent correlations were significant (p < 0.01) and positive. The correlation between RS and ATS was stronger (r = 0.70) compared to that of RS and INK (r = 0.51). Among the scales, BMS had the highest correlation with both RS (r = 0.84) and ATS (r = 0.76), while the correlation with INK was lower (r = 0.52). The correlation between ATS and INK was r = 0.66.

Figure 2. Confirmatory factor analysis of the four-factor-model of the InClass scales with Inclusion Scale (INK) (elementary school only).

7 Discussion

In order to provide appropriate support for students with and without SEN, teachers need a specific attitude or belief, knowledge or understanding, and competencies for managing heterogeneous classes and using effective teaching methods (Pozas et al., 2020; European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education, 2022). It is particularly crucial to support novice teachers in developing a professional classroom management approach (Wedde et al., 2023). Classroom management encompasses the various methods and activities that shape the learning environment, enabling both curricular and emotional and social learning (Evertson and Weinstein, 2006). The main goal of the current study, namely, to develop a new classroom management assessment tool that focuses on heterogeneous learning groups and meets the needs of all students, was reached. In almost all cases, a high level of understanding of the items was achieved by the student teachers.

InClass is particularly useful for student teachers to assess internship experiences in different schools in terms of inclusive classroom management. After completing InClass, each student teacher was given the mean of the responses to the three scales, ATS, RS, and BMS. The possible values were: 1 = disagree to 3 = neutral to 5 = agree. The students were able to compare these mean scores with their peers and discuss in the seminars which scale had received a higher score. In this way, differences between schools could be identified and reflected upon. The analysis can enable them to draw comparative conclusions from the different observations or derive key insights for their future work. InClass may also be useful for student teachers in terms of self-assessment or for the mutual assessment among fellow student teachers.

In order to make the scale economically usable, six items could be removed from the 21 items. By shortening the scales by two items each, good fit values could be achieved, which allows for a more time-efficient use of the instrument. This also led to a concretization of the classroom management methods that can be actively used by the teaching staff. The Adaptive Teaching Scale (ATS) now includes five items that require intentional design of instruction and the learning environment by the teaching staff to intensively support individual learning. The remaining five items of the Relationship Scale (RS) describe active support methods for all students to strengthen positive teacher-student and student-student relationships. The Behavior Management Scale (BMS) focuses on rule transparency, positive motivation, optimal use of learning time, and disruption prevention to maximize individual learning time for all students.

The instrument has shown good reliability in the assessment of teachers in special and elementary schools. Not only can it be used in practice with the three InClass dimensions (ATS, RS, BMS), but also with the Inclusion Scale (INK). Pearson’s correlation showed a significant, positive relationship between all scales measured, confirming the results of the pilot study. This is likely due to the fact that the scales were formulated according to the essential components of classroom management and strongly aligned with other classroom leadership questionnaires such as the LDK (Krammer et al., 2021).

The results of further analyses showed that the assessed teachers in special education schools were rated higher than the teachers in elementary schools. This can be explained by the fact that the items were based on key components of classroom management (Wang et al., 1993; Simonsen et al., 2008; Scott and Nakamura, 2022). These components are essential for the learning of students with SEN: maximizing the individual learning time, preventing classroom disruptions, individualizing learning, and proactive behavior management practices. In special schools, greater attention can be devoted to these aspects as students are under less pressure to perform and teachers can spend more time establishing routines. These elements also form the basis of direct instruction, an approach that is particularly effective for children with learning difficulties (Grünke, 2006). Another explanation for the identification of a higher rating for special education teachers compared to regular education teachers could be class size. Classes in elementary schools are generally larger than those in special education. Therefore, ensuring that all students feel comfortable in the class or making the most of their learning time may be easier for a special education teacher.

Although the confirmatory factor analysis of the four-factor model of the InClass scales combined with the Inclusion Scale (INK) produced slightly inferior results compared to the three-factor model of InClass, the test statistic yielded an acceptable value for an initial examination. InClass is suitable for the usage in special education and, more so, in inclusive settings, to assess classroom management. The strength of the present study is the validation of the three classroom management scales for heterogeneous learning groups. As inclusive education varies not only between countries, but also within a country, down to individual schools (Grünke and Cavendish, 2016; Krämer et al., 2021), it is important to have a tool that addresses the needs of all students and can therefore be used in different educational contexts. InClass is able to show whether all students have access to learning through adaptive teaching. It provides feedback on the strengthening of the teacher-student and the student–student relationships and the existing prevention of classroom disruptions in order to maximize the individual learning time of all students.

At present, the validity of the instrument is still limited, as further studies are needed to confirm the structure and results. Further development of the instrument is also possible and desirable for other researchers thanks to the free license. We surveyed student teachers evaluating the teachers they observed in their most recent internship. To assess the full effectiveness of InClass, teacher perspectives should as well be considered. It would also be useful to obtain student teachers’ assessments of the observed teachers directly during their internship. Retrospective evaluation can be difficult or may lead to slight distortions. It may also be useful for student teachers to assess themselves in terms of their classroom management. For this purpose, guided internships are necessary, as called for by Sokal et al. (2013). They emphasize the importance of high-quality inclusive internships, which they see not only as an essential feature of effective teacher preparation programs, but also as a way to increase teacher efficacy in classroom management. In guided internships, it would also be possible to have an in-depth discussion with the student teachers about the evaluation criteria of InClass. It is important that student teachers consider every single student in the class in their assessment. In the case of class-level formulations, all students are part of the assessment, including those who have special needs or attention requirements. From a methodological perspective, the results are limited by sample size and degrees of freedom. In CFA, a small sample size and low degrees of freedom often result in a larger sample could be used to verify whether the model fit improves.

Effective classroom management that considers all students in a class and their needs will be increasingly relevant in the future, especially in inclusive settings. In this context, instruments such as InClass are important tools for practice and research, and can also be central in teacher training. In our study, we surveyed student teachers who assessed evaluating the teachers they observed in their most recent internship. In future planned studies, we aim to gather assessments from student teachers directly during their internships. In this vein, our specific plan is to train educators in the use of scales to prepare them for teaching in inclusive and heterogeneous settings. InClass can contribute to incorporating into teacher education the aspect of thinking and acting inclusively throughout. In an ever-growing diverse world, it is crucial to provide effective education to every child. Hence, there is a pertinent need for inclusive classroom management and individualized learning.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found at: https://osf.io/h7n5p/.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because the research was conducted in accordance with APA ethical procedures and guidelines. Participants provided informed written consent to participate in this study and could terminate participation at any point without any disadvantage to themselves and data were treated confidentially. The survey was approved by the university’s data protection officer. Because no experimental manipulation or invasive procedure took place and since no highly sensitive data were collected, a full ethics application to the University Ethics Committee was not required. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SL: Writing – original draft. AF: Writing – review & editing. AR: Writing – review & editing. MG: Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or authorship. The publication of this article was funded by the University of Regensburg.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our special thanks for the support of colleagues who have contributed to the development of InClass.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Buchner, T., and Gebhardt, M. (2011). “Zur schulischen Integration in Österreich—historische Entwicklung, Forschung und Status Quo” Zeitschrift für Heilpädagogik, vol. 62, 298–304. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263404778_Zur_schulischen_Integration_in_Osterreich_Zur_schulischen_Integration_in_Osterreich_historische_Entwicklung_Forschung_und_Status_quo

Emmer, E. T., and Sabornie, E. J. (2015). “Introduction to the second edition” in Handbook of classroom management. ed. E. T. Emmer (New York: Routledge), 3–12.

European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2012). Profile for inclusive teachers. Odense, Denmark.

European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education (2022). Profile for inclusive teacher professional learning: Including all education professionals in teacher professional learning for inclusion. Odense, Denmark.

Evertson, C. M., and Weinstein, C. S. (2006). “Classroom management as a field of inquiry” in Handbook of classroom management: Research, practice, and contemporary issues. eds. C. M. Evertson and C. S. Weinstein (New York, NY: Routledge), 3–15.

Frey, A. (2021). “Klassenführung in der Inklusion” in Professionalisierung für ein inklusives Schulsystem. eds. A. Rank, A. Frey, and M. Munser-Kiefer (Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt), 34–70.

Garrote, A., Felder, F., Krähenmann, H., Schnepel, S., Sermier Dessemontet, R., and Moser Opitz, E. (2020). Social acceptance in inclusive classrooms: the role of teacher attitudes toward inclusion and classroom management. Front. Educ. 5:582873. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.582873

Gebhardt, M. (2018). “Einstellungen von Lehrkräften zur schulischen Inklusion in Deutschland” in Leistung und Wohlbefinden in der Schule: Herausforderung Inklusion. eds. K. Rathmann and K. Hurrelmann (Weinheim: Beltz Juventa), 340–351.

Gebhardt, M., Schurig, M., Suggate, S., Scheer, D., and Capovilla, D. (2022). Social, systemic, individual-medical or cultural? Questionnaire on the concepts of disability among teacher education students. Front. Educ. 6:701987. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.701987

Grünke, M. (2006). Zur Effektivität von Fördermethoden bei Kindern und Jugendlichen mit Lernstörungen. Kindheit und Entwicklung 15, 239–254. doi: 10.1026/0942-5403.15.4.239

Grünke, M., and Cavendish, W. (2016). Learning disabilities around the globe: making sense of the heterogeneity of the different viewpoints. Learn. Disabil. Contemp. J. 14, 1–8. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301221227

Hoffmann, L., Närhi, V., Savolainen, H., and Schwab, S. (2021). Classroom behavioural climate in inclusive education – a study on secondary students’ perceptions. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 21, 312–322. doi: 10.1111/1471-3802.12529

Hornby, G. (2014). “Inclusive special education: the need for a new theory” in Inclusive special education. ed. G. Hornby (New York, NY: Springer New York), 1–18.

Hu, L., and Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118

Johler, M., Krumsvik, R. J., Bugge, H. E., and Helgevold, N. (2022). Teachers’ perceptions of their role and classroom management practices in a technology rich primary school classroom. Front. Educ. 7:841385. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.841385

Korpershoek, H., Harms, T., Boer, H. D., van Kuijk, M., and Doolaard, S. (2016). A meta-analysis of the effects of classroom management strategies and classroom management programs on students’ academic, behavioral, emotional, and motivational outcomes. Rev. Educ. Res. 86, 643–680. doi: 10.3102/0034654315626799

Krämer, S., Möller, J., and Zimmermann, F. (2021). Inclusive education of students with general learning difficulties: a meta-analysis. Rev. Educ. Res. 91, 432–478. doi: 10.3102/0034654321998072

Krammer, G., Pflanzl, B., Lenske, G., and Mayr, J. (2021). Assessing quality of teaching from different perspectives: measurement invariance across teachers and classes. Educ. Assess. 26, 88–103. doi: 10.1080/10627197.2020.1858785

Lane, K., Falk, K., and Wehby, J. (2006). “Classroom management in special education classrooms and resource rooms” in Handbook of classroom management: Research, practice, and contemporary issues. eds. C. M. Evertson and C. S. Weinstein (New York, NY: Routledge), 439–460.

Lane, K. L., Menzies, H. M., Smith-Menzies, L., and Lane, K. S. (2022). “Classroom management to support students with disabilities: empowering general and special educators” in Handbook of classroom management. eds. E. J. Sabornie and D. L. Espelage (New York: Routledge), 499–516.

Lutz, S., Frey, A., Rank, A., and Gebhardt, M. (2022a). Skala zur inklusiven Klassenführung – Fremdbeobachtung (InKlass-F) Regensburg: Universität Regensburg. doi: 10.5283/epub.52277

Lutz, S., Frey, A., Rank, A., and Gebhardt, M. (2022b). Skala zur inklusiven Klassenführung – Selbsteinschätzung (InKlass-S) Regensburg: Universität Regensburg. doi: 10.5283/epub.52269

Lutz, S., Frey, A., Rank, A., and Gebhardt, M. (2023). Scale for classroom management in inclusive schools (InClass) Regensburg: Universität Regensburg. doi: 10.5283/epub.53929

Mayr, J., Eder, F., Fartacek, W., Lenske, G., and Pflanzl, B. (2018). Linzer Diagnosebogen zur Klassenführung: Version LDK-P-LPG. Available at: https://ldk.aau.at/files/LDK-P-LPG.pdf (Accessed February 15, 2024).

Mayr, J., Lenske, G., Pflanzl, B., and Seethaler, E. (2021). “Schülerrückmeldungen wirksam machen. Ein Werkstattbericht aus der Arbeit mit dem Linzer Konzept der Klassenführung” in Quo vadis Forschung zu Schülerrückmeldungen zum Unterricht. eds. K. Göbel, C. Wyss, K. Neuber, and M. Raaflaub (Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden), 67–93.

Miesera, S., DeVries, J. M., Jungjohann, J., and Gebhardt, M. (2018). Correlation between attitudes, concerns, self-efficacy and teaching intentions in inclusive education evidence from German pre-service teachers using international scales. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 19, 103–114. doi: 10.1111/1471-3802.12432

Pianta, R. C., La Paro, K. M., and Hamre, B. K. (2008). Classroom assessment scoring system: CLASS; manual. Baltimore, Md. Brookes.

Perry, D. B., Bergen, T., and Brekelmans, M. (2006). “Convergence and divergence between students’ and teachers’ perceptions of instructional behaviour in Dutch secondary education” in Contemporary approaches to research on learning environments. eds. D. Fisher and M. S. Khine (Hackensack, N.J World Scientific), 125–160. doi: 10.1142/9789812774651_0006

Pijl, S. J. (2010). Preparing teachers for inclusive education: some reflections from the Netherlands. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 10, 197–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-3802.2010.01165.x

Pozas, M., Letzel, V., and Schneider, C. (2020). Teachers and differentiated instruction: exploring differentiation practices to address student diversity. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 20, 217–230. doi: 10.1111/1471-3802.12481

Rank, A., and Frey, A. (2021). “Einleitung” in Professionalisierung für ein inklusives Schulsystem. eds. A. Rank, A. Frey, and M. Munser-Kiefer (Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt), 11–15.

Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Soft. 48, 1–38. doi: 10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Schurig, M., Weiß, S., Kiel, E., Heimlich, U., and Gebhardt, M. (2020). Assessment of the quality of inclusive schools a short form of the quality scale of inclusive school development (QU!S-S) – reliability, factorial structure and measurement invariance. Int. J. Incl. Educ., 1–16. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2020.1862405

Scott, T. M., and Nakamura, J. (2022). “Effective instruction as the basis for classroom management” in Handbook of classroom management. eds. E. J. Sabornie and D. L. Espelage (New York: Routledge), 15–30.

Serke, B. (2019). Schulisches Wohlbefinden in inklusiven und exklusiven Schulmodellen. Eine empirische Studie zur Wahrnehmung und Förderung des schulischen Wohlbefindens von Kindern mit sonderpädagogischem Förderbedarf Lernen. Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt.

Simonsen, B., Fairbanks, S., Briesch, A., Myers, D., and Sugai, G. (2008). Evidence-based practices in classroom management: considerations for research to practice. Educ. Treat. Child. 31, 351–380. doi: 10.1353/etc.0.0007

Slater, E. V., and Main, S. (2020). A measure of classroom management: validation of a pre-service teacher self-efficacy scale. J. Educ. Teach. 46, 616–630. doi: 10.1080/02607476.2020.1770579

Sokal, L., Woloshyn, D., and Funk-Unrau, S. (2013). How important is practicum to pre-service teacher development for inclusive teaching? Effects on efficacy in classroom management. Alberta J. Educ. Res. 59, 285–298. doi: 10.55016/ojs/ajer.v59i2.55680

Soodak, L. C., and McCarthy, M. R. (2006). “Classroom management in inclusive settings” in Handbook of classroom management: Research, practice, and contemporary issues. eds. C. M. Evertson and C. S. Weinstein (New York, NY: Routledge), 461–489.

Soodak, L. C., Podell, D. M., and Lehman, L. R. (1998). Teacher, student, and school attributes as predictors of teachers' responses to inclusion. J. Spec. Educ. 31, 480–497. doi: 10.1177/002246699803100405

United Nations (2006). Convention on the rights of persons with disabilities. Available at: https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-2.html [Accessed September 22, 2023].

Wang, M. C., Haertel, G. D., and Walberg, H. J. (1993). Toward a knowledge base for school learning. Rev. Educ. Res. 63, 249–294. doi: 10.2307/1170546

Weber, K. E., and Greiner, F. (2019). Development of pre-service teachers' self-efficacy beliefs and attitudes towards inclusive education through first teaching experiences. J. Res. Spec. Educ. Needs 19, 73–84. doi: 10.1111/1471-3802.12479

Keywords: classroom management, InClass, inclusive education, special education, student teachers, special educational needs (SEN)

Citation: Lutz S, Frey A, Rank A and Gebhardt M (2024) InClass – an instrument to assess classroom management in inclusive and special education with a focus on heterogeneous learning groups. Front. Educ. 9:1316059. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1316059

Edited by:

Brianna L. Kennedy, University of Glasgow, United KingdomReviewed by:

Khalil Gholami, University of Helsinki, FinlandAriana Garrote, University of Applied Sciences and Arts Northwestern Switzerland, Switzerland

Copyright © 2024 Lutz, Frey, Rank and Gebhardt. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence:Stephanie Lutz, U3RlcGhhbmllLkx1dHpAdXIuZGU=

Stephanie Lutz

Stephanie Lutz Anne Frey2

Anne Frey2