- Universiti Putra Malaysia, Serdang, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia

Doctoral examiners play a pivotal role in upholding academic standards; therefore, they must be supported in their work. Drawing on situated learning theory, this paper proposes a conceptual training framework to empower examiners, particularly those participating in the PhD viva. The framework comprises three key initiatives: a professional development programme, a peer review, and an accreditation programme. The paper further highlights the potential benefits of the training initiatives and discusses implementation challenges aimed at fostering examiners’ continuous professional development, promoting a deeper understanding of assessment literacy, and maintaining the overall quality of doctoral assessment.

Introduction

Universities play a pivotal role in global higher education, ensuring that the doctoral programmes they offer are not only rigorous but also internationally recognised. While considerable resources are often invested in research supervision, the professional development of examiners receives less attention. Although progress is being made in some universities, such as the University of Otago, New Zealand, offering training for internal examiners, there is a scarcity of training specifically designed to prepare examiners for the viva. This gap raises questions about the readiness of examiners to navigate the multifaceted complexities of doctoral assessment, as it directly impacts the credibility and standing of the awarded qualifications (Bernstein et al., 2014; Chetcuti et al., 2022).

In the context of Malaysian doctoral education, the British model of assessment is adopted, involving a written thesis examination and a mandatory closed-door viva (oral examination). Notably, examiners are not part of the supervisory committee; instead, they are independently appointed from within and outside the university. Examiners take part in the PhD viva, which consists of three parts: the pre-viva meeting, the viva talk, and the post-viva meeting (Tan, 2023a). Despite variations in doctoral assessment systems across countries (Powell and Green, 2007), the potential benefits derived from examiner training remain universally applicable.

This study addresses the need for examiner support and training in doctoral assessment. With an understanding that examiners play a crucial role in upholding academic standards, it becomes imperative to enhance their capacity for rigorous and purpose-driven assessment. Drawing on my experience as a higher education researcher investigating the PhD viva and examiner practises, this paper extends my earlier work (Tan, 2023b). In the prior study, given the limited learning opportunities, I advocated for supporting examiners in their assessment endeavours and called for institutional support within the Malaysian doctoral education context. In this study, I asked the question: How should examiners and their practises in the PhD viva be supported by the university for effective assessment?

The data for this study were sourced through a review of existing professional learning initiatives for academics at selected universities. This includes universities, such as the University of Otago, New Zealand, University of Auckland, New Zealand, and University of Bristol, United Kingdom. Moreover, the IELTS training guide for prospective examiners was referred to gain insights on examiner recruitment and training.

Situated learning theory

Situated learning theory (SLT) is adopted as the theoretical framework in this study to understand doctoral examiners and their assessment practises. The theory emphasises the importance of learning within authentic contexts and social interactions. It is grounded in the work of Lave and Wenger (1991), who argue that learning is a process that occurs through legitimate peripheral participation (LPP) in communities of practise (CoP). SLT proposes that knowledge acquisition and skill development are most effective when learners actively engage in real-world tasks and experiences. According to this perspective, learning is not solely a cognitive process that occurs within the individual, but rather a social and collaborative endeavour that occurs through active participation in meaningful activities.

The integration of SLT also extends into the recognition of the importance of social participation and the establishment of communities of practise. This perspective, emphasising learning as membership in a community, aligns with the dynamic and interactive nature of examiner roles within the doctoral assessment process. The acknowledgement of collective knowledge acquisition and shared activities complements the intricate nature of the assessment. Furthermore, the theory’s acknowledgement of cultural dimensions underscores the fact that assessment practises are situated within broader social contexts, thereby influencing the outcomes and interpretations. By embracing the principles of situated learning, examiners can have meaningful learning experiences that bridge the gap between theory and practise, enhance learner engagement, and foster the development of practical examining skills and knowledge.

Professional learning initiatives

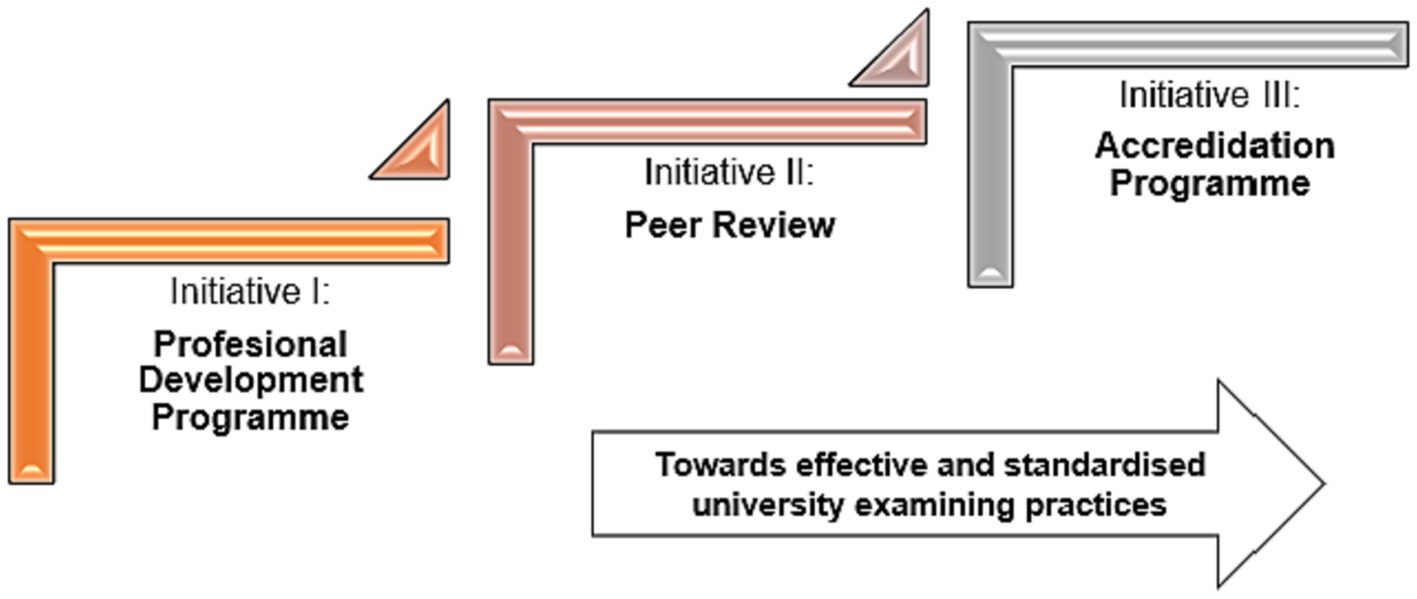

Three initiatives are proposed to support examiners: a PDP, a peer review of the viva, and an accreditation programme. These initiatives:

• provide a platform for conversation;

• encourage examiners to learn, reflect on their practise and enhance it, if necessary;

• encourage examiners to share their practise with others; and

• provide ongoing, accessible institutional support systems to enable effective learning and assessment.

When the three initiatives are implemented together, they form a provisional training framework that universities could use to support examiners and their examining practises (Figure 1). The framework could be included in examiner education either as informal, non-structured, formal, or structured support, provided it achieves the aim of supporting examiners for the doctoral assessment. Each of the initiatives is explained below.

Initiative I: professional development programme

A professional development programme (PDP) focusing on the viva should be offered. PDPs are designed to target learners on particular topics, are facilitated in some way, and aim to foster learning (Borko, 2004). Nonetheless, current PDPs for academics tend to focus on how to examine a written thesis rather than on how to examine in the viva. As the viva is an essential part of the doctoral assessment, training specific to the viva is indispensable.

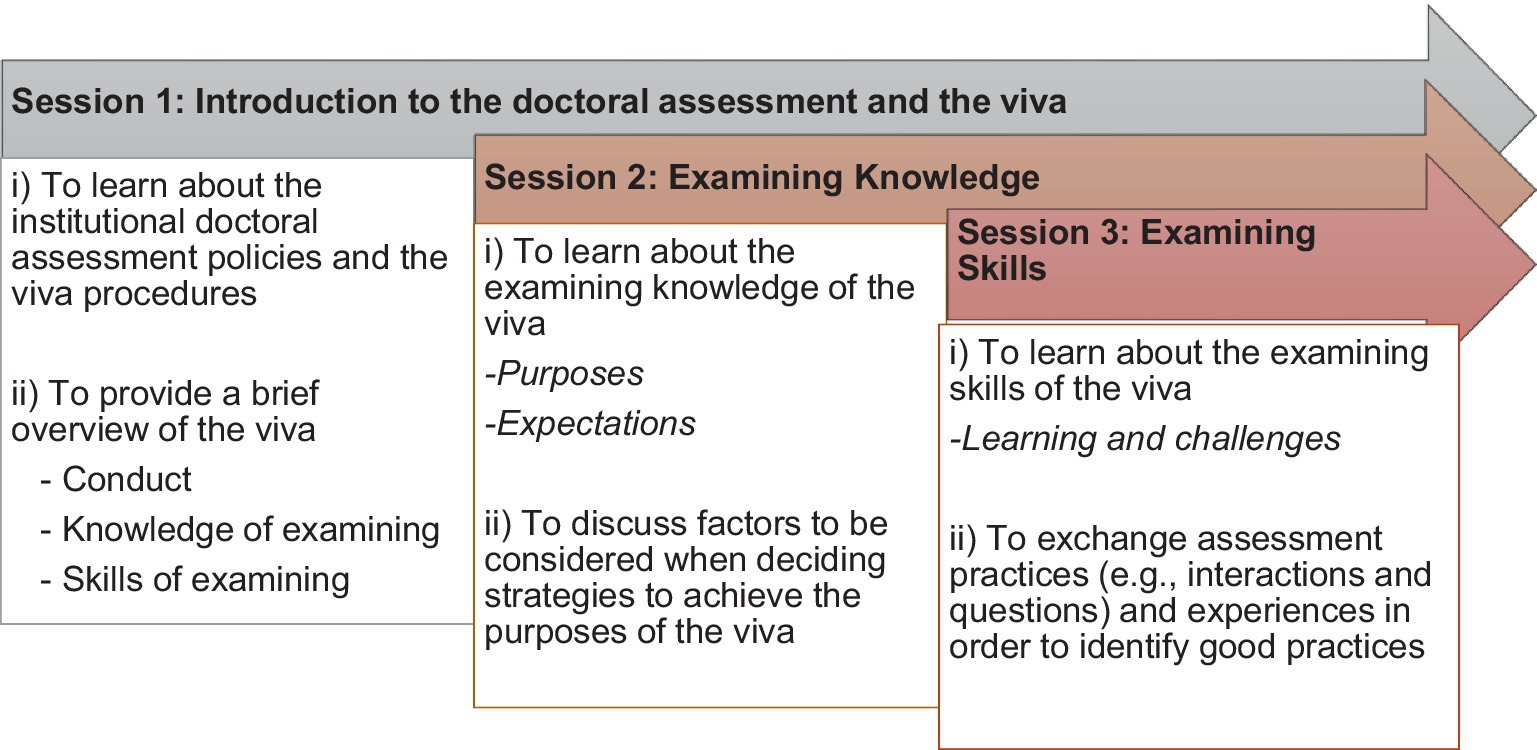

Inspired by existing doctoral supervision PDPs, a similar viva training programme could be developed. For instance, the University of Bristol offers three-session seminars on supervision, focusing on institutional policies and experiences, facilitated by an academic developer. This adaptable model supports academics aiming to learn supervision amidst a hectic workload. Illustrated in Figure 2, the three-session PDP emphasises institutional policies, examiner practises, and experiences, proposing potential learning topics. It can be conducted face-to-face or online, facilitated by academic developers, fostering a research discourse community of examiner practise (Lave and Wenger, 1991).

Potential and newly appointed examiners would be anticipated to attend the three sessions of the PDP to familiarise themselves with the PhD viva at the university. They would be introduced to the university’s doctoral assessment and oral examination policy and gain the knowledge and skills to examine. The knowledge basis of the PDP could be informed by the current literature, such as thesis examination practises (e.g., Chetcuti et al., 2022; Kobayashi and Emmeche, 2023) and viva practises (e.g., Tan, 2022, 2023a; Wisker et al., 2022), and complemented by examiners’ experience sharing. The three sessions of the PDP could also be offered as an intensive one-day training. Regardless of the delivery mode, the learning outcome would be to ensure that examiners have a clearer view of the institutional policy and practises of the doctoral assessment expected of them at the university.

Initiative II: peer review

Peer review should be introduced to examiners of the PhD viva. Peer review is a purposeful, non-judgemental, collaborative process whereby a colleague or peer is invited to observe a selected aspect/s of another’s teaching or supervision and provide constructive feedback on its effectiveness in promoting student learning (University of Otago, n.d.). Although peer review intends to help academics review and enhance their teaching and supervision practise, it can also be adapted as a professional learning tool and help academics in doctoral assessment, particularly the oral examination.

There are various ways to conduct peer review. This study suggests learning from the peer review of the teaching/supervision model, initiated at the University of Otago, New Zealand. This is a voluntary, collaborative academic activity that takes place among colleagues for learning. There are five steps to conducting a peer review of doctoral assessment for examiners:

i. Choosing an appropriate peer for the peer review.

ii. Identifying the aims, focus and roles in the briefing session.

iii. Conducting the review.

iv. Having a debriefing session after the review.

v. Encouraging critical reflection for learning.

The five-step peer review is a learning activity that could be used as part of an academic mentoring programme, with experienced academics guiding less experienced academics. Academics who are experienced examiners in the department, faculty, division, or university could be selected as mentors to assist novice examiners, such as by providing feedback on their examining practises. The review might involve a discussion session or observation of the examiner during the viva followed by a discussion. Less experienced examiners would discuss their practise with experienced colleagues to learn how to examine better in the viva, drawing on their reflections from the peer review. Examiners could also exchange their viva experiences with colleagues to help them identify good practises. This sharing of practise among examiners would foster more effective examining practise with an aim to encourage student learning in the oral examination (Tinkler and Jackson, 2004).

Initiative III: accreditation programme

An accreditation programme for examiners could be implemented by the university. ‘Accreditation’ refers to training, monitoring, and certifying an academic to conduct an assessment. Since a PhD has global recognition, and the viva is a high-stakes examination, examiners should be properly trained and certified. Holding a PhD does not mean an academic can examine well in the assessment. To be appointed as an examiner, one should be accredited. This initiative is inspired by the implemented guidelines on becoming and supporting supervisors at the University of Auckland (2012), where academics need to be accredited before supervising postgraduates. The goal is to ensure consistent and high-quality supervision and research across the university, and similar guidelines could be developed for examiners.

Given the crucial role of examiners in the viva, they are responsible for ensuring that the assessment decision is valid and reliable. One way to ensure that examiners are accountable is through training and certification; however, with rare exceptions, this is not being done. A comparison with the appointment of examiners for the high-stakes English language test, the International English Language Testing System (IELTS) (IELTS, n.d.), reveals that examiners must be trained and certified every 2 years to ensure practise quality. This quality control is lacking in the doctoral assessment, where examiner practises rely on experience rather than formal training. Therefore, it is recommended that examiners receive training and perhaps be certified to allow them to fulfil their responsibilities in the assessment, uphold thesis quality, and align with university expectations.

While the IELTS and PhD viva differ in their focus—English language proficiency for IELTS and research competency and communicative ability for the viva—they are alike because both have an oral component. This study adapts the IELTS examiner recruitment and training model, incorporating insights from the Guidelines on Accreditation of Supervisors of University of Auckland (2012), to propose an accreditation programme for examiners. The six-step examiner recruitment and training guide includes:

1. Recruitment

Academics considered for the role of examiner should have a relevant doctoral degree, experience supervising doctoral students, and be research active.

2. Induction

Potential examiners attend a PDP on the university’s doctoral examination policy.

3. Training

Potential examiners attend the PDP to obtain doctoral examination knowledge and skills.

4. Certification

Examiners undertake a mock examination, evaluate a thesis and participate in a recorded or mock viva to demonstrate their PhD assessment abilities. Successful completion results in accreditation.

5. Monitoring

Regular monitoring by senior colleagues or examiners occurs at least annually, with the potential for peer reviews as part of the monitoring process.

6. Standardisation and re-certification

To maintain standardisation, examiners may undergo re-certification every 5 years, involving assessments or performance appraisals, as appropriate.

Discussion

I have presented three initiatives to support examiners and their practises of the PhD viva: a PDP, a peer review of the viva, and an accreditation programme. These initiatives are professional development opportunities to assist novice examiners in enhancing their competence and effectiveness in conducting the doctoral assessment. The overarching aim is to support examiners’ community of practise (Lave and Wenger, 1991) by establishing standardised examining practises across the university, ensuring that potential examiners are well-equipped to meet the professional and personality requirements of the PhD assessment (Kiley, 2009).

While acknowledging the merits of these initiatives, it is crucial to recognise that their implementation may not be without challenges. The PDP is considered the most feasible initiative, with existing programmes related to supervision and thesis examination serving as favourable precedents. Various supervisory development workshops are also available (Brew and Peseta, 2004; Kiley, 2011) and are known to be effective (McCulloch and Loeser, 2016). Despite the non-mandatory nature of a viva-focused PDP, its integration into professional development opportunities holds significant potential in enhancing examiner capacities.

The second initiative, peer review of the viva, may present notable implementation complexities due to its reliance on observation and experience sharing. Although many academics recognise the benefits of peer observation, such as in developing teaching practise (Hendry and Oliver, 2012), some academics might be sceptical of using peer review in the viva. Potential concerns about the evaluative nature of the review and the resultant impact on examiner dialogue must be carefully addressed. Moreover, the intricate power dynamics within academia, particularly concerning esteemed senior professors undergoing review by junior colleagues, present additional considerations. The cultural milieu, especially in collectivist societies like Malaysia, introduces nuances in how reviewers might provide critiques, emphasising the need for thoughtful navigation of potential challenges.

The third initiative, establishing an accreditation programme, stands out as the most intricate undertaking due to its substantial resource investment. While essential for maintaining the quality of doctoral assessment, executing the programme necessitates the development of new policies, training, and allocation of financial and human resources. Appointing experienced trainers familiar with examining practises and university culture is pivotal for the programme’s efficacy. The success of the accreditation initiative, ensuring reliability and standardisation of doctoral assessment across the university, demands a high level of commitment given the ongoing and time-consuming nature of the process.

The three initiatives are believed to be beneficial in better preparing examiners for the viva and doctoral assessment, impacting both examiner and supervisory practises (McCulloch and Loeser, 2016). Nevertheless, their effectiveness and impact require careful evaluation, considering potential weaknesses within the Malaysian or international context. Applying Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick’s (2006) training evaluation model is recommended for this purpose, alongside a thorough examination of academics’ receptiveness and a comprehensive study of the risks and consequences before, during, and after implementation.

Despite the study’s foundation in personal experience and existing institutional initiatives, the training initiatives suggest a potential for implementation and further enhancement and expansion. The paper emphasises the need for future research to transcend its boundaries, exploring and implementing these initiatives to augment examiner support and refine their practical application in doctoral education worldwide.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

WT: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author declares that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Bernstein, B. L., Evans, B., Fyffe, J., Halai, N., Hall, F. L., Marsh, H., et al. (2014). “The continuing evolution of the research doctorate” in Globalization and Its Impacts on the Quality of PhD Education: Forces and Forms in Doctoral Education Worldwide. eds. M. Nerad and B. Evans (Rotterdam: Sense Publishers), 5–30.

Borko, H. (2004). Professional development and teacher learning: mapping the terrain. Educ. Res. 33, 3–15. doi: 10.3102/0013189X033008003

Brew, A., and Peseta, T. (2004). Changing postgraduate supervision practice: a programme to encourage learning through reflection and feedback. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 41, 5–22. doi: 10.1080/1470329032000172685

Chetcuti, D., Cacciottolo, J., and Vella, N. (2022). What do examiners look for in a PhD thesis? Explicit and implicit criteria used by examiners across disciplines. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 47, 1358–1373. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2022.2048293

Hendry, G. D., and Oliver, G. R. (2012). Seeing is believing: the benefits of peer observation. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pract. 9, 87–96. doi: 10.53761/1.9.1.7

IELTS (n.d.). Examiner recruitment and training. Available at: https://www.ielts.org/for-teachers/examiner-recruitment-and-training

Kiley, M. (2009). You don't want a smart alec': selecting examiners to assess doctoral dissertations. Stud. High. Educ. 34, 889–903. doi: 10.1080/03075070802713112

Kiley, M. (2011). Developments in research supervisor training: causes and responses. Stud. High. Educ. 36, 585–599. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2011.594595

Kirkpatrick, D., and Kirkpatrick, J. (2006). Evaluating Training Programmes: The Four Levels (3rd Edn.). San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler

Kobayashi, S., and Emmeche, C. (2023). What makes a good PhD thesis? Norms of science as reflected in written assessments of PhD theses. Assess. Eval. High. Educ.. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2023.2200917 (Epub ahead of print).

Lave, J., and Wenger, E. (1991). Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McCulloch, A., and Loeser, C. (2016). Does research degree supervisor training work? The impact of a professional development induction workshop on supervision practice. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 35, 968–982. doi: 10.1080/07294360.2016.1139547

Tan, W. C. (2022). Speaking the language of defence: narratives of doctoral examiners on the PhD viva. Qual. Res. J. 22, 478–488. doi: 10.1108/QRJ-01-2022-0009

Tan, W. C. (2023a). Purpose-driven oral examination: insights from doctoral viva examiners. Discov. Educ. 2:52. doi: 10.1007/s44217-023-00083-6

Tan, W. C. (2023b). Doctoral examiners’ narratives of learning to examine in the PhD viva: a call for support. High. Educ. 86, 527–539. doi: 10.1007/s10734-022-00913-w

Tinkler, P., and Jackson, C. (2004). The Doctoral Examination Process: A Handbook for Students, Examiners and Supervisors. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

University of Auckland (2012). Guidelines on accreditation of supervisors, University of Auckland, New Zealand. Available at: https://cdn.auckland.ac.nz/assets/central/about/the-university/how-the-university-works/policy-and-administration/Supervision/accreditation-of-supervisors.pdf

University of Otago (n.d.). Peer review and feedback about teaching and supervision. Available at: https://www.otago.ac.nz/hedc/otago703482.pdf

Keywords: PhD viva, professional development, assessment literacy, examiners, doctoral education

Citation: Tan WC (2024) Empowering examiners to develop doctoral assessment literacy: a situated learning perspective. Front. Educ. 9:1345661. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2024.1345661

Edited by:

Paitoon Pimdee, King Mongkut's Institute of Technology Ladkrabang, ThailandReviewed by:

Maresi Nerad, University of Washington, United StatesCopyright © 2024 Tan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wee Chun Tan, d2VlY2h1bkB1cG0uZWR1Lm15

Wee Chun Tan

Wee Chun Tan