Abstract

Introduction:

This study investigates how professional learning contributes to antiracist district transformation, focusing on the roles of transformational leadership and double-loop learning. Transformational leadership inspires followers to achieve exceptional goals, while double-loop learning involves questioning underlying assumptions and values to foster systemic change.

Methods:

A longitudinal case study approach was employed to examine the experiences of seven district and school-level leaders in an urban-intensive school district. These leaders participated in a multi-year antiracist professional learning series designed to promote equity and systemic change.

Results:

Preliminary findings indicate that the professional learning series facilitated a shift in participants’ racial schema and enhanced their capacity to navigate resistance to antiracist practices. For example, leaders implemented new protocols for reviewing instructional materials to ensure cultural relevance and inclusivity. Participants also reported developing strategies to address resistance, such as facilitating open forums to discuss concerns and build consensus.

Discussion:

This study contributes to the growing body of literature on leadership for equity, highlighting the importance of professional learning in promoting antiracist transformation. The findings offer insights for districts seeking to foster systemic change and provide practical strategies for leaders navigating resistance to equity initiatives.

Introduction

Despite decades of reform efforts, systemic racism continues to present challenges within the American education system, impacting the opportunities and potential of students of color who bring a wealth of cultural knowledge, resilience, and unique perspectives that can enrich the educational experience for all. While many school districts have implemented diversity initiatives and equity training, these efforts often fail to create lasting, transformative change (Leonardo and Porter, 2010; Singleton et al., 2006). The unequal access to opportunities and resources in academic achievement, disciplinary practices, and advanced coursework underscores the need for a more profound, systemic approach to antiracist education that leverages the strengths and talents of all students (Milner, 2012). Despite the well-established literature on transformational leadership and anti-racism, there is a significant gap in the literature connecting the two. This study bridges this gap by providing insight into transformational leadership practices that are vital to anti-racist work and offering practical applications on ways to reach district transformation.

Research sheds light on the importance of leaders and district support in school organizational change efforts school organizational change efforts, particularly those that mitigate inequities (Leithwood and Jantzi, 2008; Welton et al., 2018). School leader’s actions are critical to transforming how teachers and other leaders within their district respond to inequitable challenges faced in schools that are derived from a White-supremacist culture (Grissom et al., 2021; Khalifa, 2020). Principals are critical in determining and honing the school culture and climate (Grissom et al., 2021). Principals and other school leaders develop their abilities to lead with an equity focus through their life experiences, preparation programs, in-service professional development experiences, or some combination (Gooden et al., 2023).

Targeted professional learning, grounded in transformational leadership principles, can catalyze significant shifts in educational leaders’ racial schema, enhancing their capacity to lead antiracist district transformation. We contend that by engaging leaders in critical self-reflection, challenging existing mental models, and fostering a deep commitment to equity, such professional learning experiences can disrupt ingrained patterns of thought and behavior that perpetuate systemic racism in educational settings. Specifically, this approach to professional learning facilitates double-loop learning, enabling leaders to question and reframe their fundamental assumptions about race and equity in education. This cognitive and dispositional shift is crucial for leaders to effectively implement and sustain antiracist practices across their districts, moving beyond surface-level changes to address the deep-seated, often invisible structures that maintain racial inequities in schools. Our findings suggest that this transformative learning process equips leaders with the mindset, knowledge, and moral imperative necessary to navigate the complex, often resistant landscape of systemic change in pursuit of genuine racial equity. This study seeks to answer the following research questions:

-

How does professional learning shift leaders’ racial schema and promote antiracist dispositions (e.g., critical self-reflection, empathy, commitment to equity) to foster district transformation?

-

In what ways do transformational leadership and double-loop learning manifest in leaders’ approaches to antiracist change?

This research is significant because it bridges the gap between theoretical frameworks of transformational leadership and double-loop learning and their practical application in antiracist district transformation. By examining the experiences of district and school leaders engaged in long-term professional learning, we aim to provide insights that can inform more effective strategies for creating equitable educational systems. The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: We begin with a review of the literature on racism in education, transformational leadership, and organizational learning theory. Next, we detail our methodology, including participant selection, data collection, and analysis procedures. We then present our findings, organized thematically to illustrate the key aspects of leaders’ experiences and actions. The discussion section interprets these findings in light of existing theory and practice. We conclude by addressing the limitations of our study, suggesting areas for future research, and offering recommendations for districts seeking to implement similar antiracist initiatives.

Literature review and theoretical framework

This literature review examines the theoretical underpinnings of antiracist district transformation through the lens of transformational leadership and organizational learning. First, we present a brief overview of the historical context of systemic racism in education. Second, we explore the concept of transformational leadership, examining its relevance to educational leadership and addressing critiques of its effectiveness. Third, we delve into organizational learning theory, focusing on the distinction between single-loop and double-loop learning and their implications for educational change. Finally, we synthesize these concepts to demonstrate their interconnectedness and relevance to antiracist district transformation.

History of racism in education

The history of American education is deeply intertwined with systemic racism, dating back to the era of slavery when education for enslaved Africans was actively suppressed (Anderson, 1988). Du Bois (1903) eloquently captured the yearning for knowledge among Black people, viewing education as the pathway from slavery to freedom. Following emancipation, discriminatory practices such as segregated schools, unequal funding, and biased curricula perpetuated inequities, limiting opportunities for Black students and other students of color (Du Bois, 1935). Landmark court cases like Brown v. Board of Education (1954) legally dismantled segregation. Still, de facto segregation and other forms of racial discrimination persisted, contributing to ongoing disparities in educational outcomes (Kozol, 2005).

Even in the present day, the legacy of racism continues to manifest in schools through inequities in academic outcomes, disproportionate disciplinary actions, and underrepresentation in advanced programs, hindering the full expression of potential and talent within these student populations (Milner, 2012; Warren et al., 2024). To address these persistent inequities, it is essential to acknowledge and confront the historical roots of racism in education and to actively work toward creating more equitable and inclusive learning environments for all students. Despite these challenges, Black communities have consistently demonstrated resilience and a commitment to education, establishing their schools, advocating for equal rights, and developing culturally relevant curricula (Dumas, 2016).

While much of the literature on racism in education has focused on the Black experience in the American South (Anderson, 1988), it is equally important to recognize the unique histories and challenges faced by Latinx students, particularly in Northeastern urban districts. Scholars such as Valenzuela (1999), and others have documented the racialization of Latinx students and the intersectionality of race, language, and immigration status in shaping educational opportunities. In our study district, which serves a predominantly Latinx and African American population, these histories are deeply intertwined. Recent research on Northeastern urban schools highlights persistent inequities and the resilience of both Black and Latinx communities in advocating for educational justice. By situating our study within this broader context, we aim to provide a more nuanced understanding of the complexities of anti-racist leadership in diverse, urban settings.

Transformational leadership

Transformational leadership (TL) has become a popular leadership stance in education over the last few decades because of the facets of the approach that complement today’s demands of school leaders. Transformational leadership (TL) is a leadership style that inspires and motivates followers to achieve extraordinary outcomes while developing their leadership capacity (Bass, 1985). TL is characterized by four key dimensions: idealized influence (charisma), inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, and individualized consideration (Bass and Riggio, 2006). TLs achieve high-order goals by building a shared vision, changing employees’ thinking and doing things, and fostering a collaborative culture (Anderson, 2017; Leithwood and Jantzi, 2008).

Transformational Leaders (TLs) in multiple sectors are proactive, act as change agents, raise followers’ awareness of their collective interest, and help their faculty and staff achieve exceptional goals (Busari et al., 2019). Jyoti and Dev (2015) explained how TLs convey a compelling vision, strengthen employee creativity, raise awareness, and develop an emotional association with their faculty and staff to achieve higher-order goals. These characteristics of a TL also align with the skills needed to engage in an antiracist transformation.

To engage in and sustain an antiracist district-wide change, new policies, systems, and structures must be implemented, and leaders must engage their faculty and staff in a deeply reflective process that includes difficult conversations and interrogates deficit mindsets (Diem and Welton, 2020; Welton et al., 2018). Most importantly, a shared vision of what an antiracist school district looks like requires leaders to be able to manage difficult conversations while inspiring their staff to envision a bold new future for their students and families. For example, Ogwumike et al. (2022) found that a mix of transformational leadership of the leaders they studied and consistent district support helped decrease disproportionate and racialized disciplinary infractions leading to out-of-school suspensions.

Transformational leadership and equity

In the context of schools, transformational leadership is particularly relevant for fostering organizational change and promoting equitable outcomes for all students (Leithwood and Jantzi, 2008). Transformational school leaders empower teachers, create a shared vision, and promote a collaborative culture that supports transformation and change (Hallinger, 2003; Leithwood et al., 2020). For example, Leithwood et al. (2020) have developed a comprehensive model of transformational school leadership, which includes three broad categories of practices: “Setting Directions,” “Developing People,” and “Redesigning the Organization.” Specific dimensions within these categories include building a school vision, providing intellectual stimulation, fostering a collaborative school culture, and creating structures for participation in decision-making (Hallinger, 2003). These constructs apply to transforming schools into more equitable, antiracist student environments.

Building a school vision for antiracist environments might involve including community stakeholders and families to ensure the vision aligns with their hopes and dreams for their children. Building intellectual stimulation might include professional development that helps teachers to become aware of their biases and to employ culturally relevant teaching practices. Fostering a collaborative school culture might require the school leadership to create affinity spaces for various racial groups. Finally, building structures for participation in decision-making might include creating a board with community members with decision-making power. Ogwumike et al. (2022) found that transformational leadership and consistent district support helped decrease disproportionate and racialized disciplinary infractions leading to out-of-school suspensions.

To truly transform schools into equitable environments, leaders must foster a culture of organizational learning where individuals and teams are encouraged to question existing assumptions, challenge ingrained practices, and experiment with new approaches (Argyris, 1977; Senge, 1990). Double-loop learning, in particular, is crucial for antiracist transformation, as it involves questioning the underlying values, beliefs, and policies that perpetuate systemic inequities (Diem and Welton, 2020). This process begins with identifying a problem or challenge (e.g., disproportionate disciplinary rates for students of color). It then involves reflecting on the assumptions that inform current practices (e.g., deficit-based views of students and families). Finally, it culminates in developing new approaches that address the root causes of the problem (e.g., implementing restorative justice practices, culturally responsive teaching, and equitable discipline policies) (Welton et al., 2018). By integrating double-loop learning into their leadership practice, leaders can create a continuous improvement cycle that drives meaningful and sustainable change.

Professional learning and organizational change

Professional learning is widely recognized as a key driver of organizational change in education. Sustained, collaborative professional development has been shown to shift educators’ beliefs and practices, particularly when focused on equity and anti-racism (Bristol and Shirrell, 2019). Effective professional learning initiatives are characterized by ongoing support, critical reflection, and alignment with district goals (Guskey, 2002). In the context of anti-racist transformation, professional learning serves as both a tool for individual growth and a lever for systemic change, enabling leaders to challenge entrenched assumptions and drive collective action (Khalifa, 2020). Our study builds on this literature by examining how a multi-year professional learning series fostered double-loop learning and transformational leadership among district leaders.

Critiques of transformational leadership

While transformational leadership is often portrayed as the most effective leadership style for managing organizational change (Middleton et al., 2015), it is essential to acknowledge alternative perspectives and potential limitations. Some scholars argue that other leadership styles, such as instructional or distributed leadership, may be more appropriate in specific contexts (Spillane and Camburn, 2006).

Critics assert that the emphasis on a leader’s vision can lead to manipulation if the vision is not developed collaboratively and does not reflect the diverse perspectives of stakeholders. To mitigate this risk, antiracist TLs must prioritize participatory decision-making, ensuring that all voices are heard and valued in shaping the vision for an equitable school system. This might include conducting community forums, establishing advisory boards with diverse representation, and actively soliciting feedback from students, families, and staff.

Another critique is that TL can overlook existing power dynamics, potentially reinforcing the marginalization of certain groups. To counter this, antiracist TLs must actively challenge and dismantle inequitable power structures by empowering marginalized voices, advocating for policy changes, and redistributing resources to support equitable outcomes. This may involve implementing policies that promote equitable resource allocation, creating leadership opportunities for individuals from underrepresented groups, and challenging biased practices within the school system.

Therefore, it is crucial to adopt a critical perspective on transformational leadership and consider its ethical implications when pursuing antiracist district transformation. Historically, antiracist practices have been largely neglected in school leadership development programs, with many programs shying away from directly addressing institutional racism and its impacts on education. This reluctance has perpetuated a lack of race consciousness among school leaders, limiting their ability to address and dismantle racist structures within their institutions effectively. It is also important to recognize that transformational leadership is not a panacea and can inadvertently perpetuate inequities if not implemented with a critical, race-conscious lens. For example, a leader’s idealized vision can overshadow community members’ cultural values, leading to resistance and undermining trust. Therefore, rather than viewing transformational leadership as a static set of traits or behaviors, this study frames it as a dynamic process that must be continuously adapted and refined in response to the specific needs and contexts of diverse school communities. This requires leaders to engage in ongoing critical self-reflection, actively seek feedback from marginalized stakeholders, and be willing to challenge their assumptions about what constitutes “good” leadership (Gooden et al., 2023; Khalifa, 2020). As such, the goal is not to simply adopt transformational leadership wholesale but to adapt and apply its principles in a manner that is explicitly aligned with antiracist values and goals.

In summary, while transformational leadership offers a valuable framework for promoting positive change in schools, adopting a critical perspective and addressing its potential limitations is essential. By prioritizing participatory decision-making, challenging inequitable power structures, and focusing on systemic reforms, antiracist TLs can create more equitable and inclusive learning environments for all students. This study will build upon this literature by examining how professional learning can support leaders in developing the knowledge, skills, and dispositions needed to become effective antiracist transformational leaders.

The racialization of organizational systems and structures in schools

Schools are not neutral institutions; instead, they are racialized organizations with systems and structures designed to maintain inequitable barriers and perpetuate White supremacist ideologies (Wooten and Couloute, 2017; Stewart et al., 2021). This racialization manifests in various ways, such as disciplinary policies that disproportionately target students of color (Warren et al., 2024). These curricula center White perspectives and marginalize diverse voices, tracking systems that limit access to advanced coursework for marginalized students (Thornton, 2023) and hiring practices that result in a lack of diversity among teaching staff and leadership (Goings et al., 2021).

Schools must actively change these entrenched systems and structures to achieve racial equity in how students experience the contents, processes, and consequences of schooling. However, such transformation requires more than surface-level adjustments; it demands a fundamental rethinking of the assumptions and values that underpin educational institutions. By understanding how schools are racialized organizations, we can better understand the challenges leaders face in implementing antiracist practices and the types of double-loop learning that are needed to dismantle inequitable systems and structures. This is where organizational learning theory provides a crucial framework for understanding how schools can adapt and improve over time (Argyris, 1999; Sternberg and Horvath, 1999; Senge, 1990). A key distinction within this theory is between single-loop and double-loop learning (Argyris and Schon, 1978). Single-loop learning involves adjusting actions and strategies without questioning underlying assumptions or values. In contrast, double-loop learning entails critical reflection on those assumptions and values, leading to fundamental changes in organizational beliefs and practices. In the context of addressing the racialization of schools, double-loop learning is essential for promoting systemic transformation. By challenging existing assumptions and values, educators can identify and address the root causes of inequities and create more equitable and effective learning environments (Cochran-Smith, 2004). This process of deep reflection and fundamental change is crucial for dismantling the very structures that perpetuate racialized organizational systems in schools. As we explore the concepts of single and double-loop learning in more detail, it becomes clear that transforming schools into truly equitable institutions requires going beyond surface-level reforms. It demands a willingness to question long-held beliefs, confront uncomfortable truths about systemic racism, and commit to ongoing, transformative change processes.

Single and double loop learning

Professional learning can be viewed through the lens of organizational learning theory, particularly Chris Argyris’ concepts of single-loop and double-loop learning, which are critical for creating transformative change (Argyris, 2003; Argyris, 1999; Sternberg and Horvath, 1999; Argyris and Schon, 1978). Single-loop learning focuses on improving operations within the existing framework of norms and values, addressing problems by adjusting actions and strategies without questioning underlying assumptions (Argyris, 2003). In the context of antiracist transformation, single-loop learning might involve implementing new diversity initiatives or revising policies without examining the systemic biases that perpetuate racial inequities. For example, dress code policies may disproportionately target students of color based on hairstyles or clothing choices, perpetuating stereotypes and creating a hostile environment (Shange, 2020). In contrast, double-loop learning involves questioning and challenging those underlying assumptions and values, leading to fundamental changes in organizational beliefs and practices (Argyris, 1999; Sternberg and Horvath, 1999; Argyris and Schon, 1978). Double-loop learning requires organizations to critically examine their mental models and be open to radically different ways of thinking and operating. In the context of antiracist transformation, this might involve questioning the very notion of meritocracy or challenging the dominant narrative of racial neutrality.

Double-loop learning involves collecting valid information, surfacing conflicting views, and fostering free choice and commitment from all organization members (Argyris, 1999; Sternberg and Horvath, 1999). It requires individuals to be open to change and critical self-reflection, challenging their underlying assumptions and motivations to create new behaviors and manage the use of self. Reflection, reflective inquiry, and critical reflection are central to leader development, stimulating dialogue and learning, and making mental models and assumptions explicit (Keating et al., 1996). Social constructivist learning processes, such as interactions with peers and co-constructing ideas, can stimulate reflection and aid in identifying the type of learning occurring. Furthermore, single-loop learning functions in organizations by accepting tacit knowledge and tacit learning, perpetuating a consolidation process, whereas double-loop learning creates a transformative process by changing the overall knowledge and competency base (Snell and Chack, 1998).

Double-loop learning ideas apply directly to antiracist leadership learning, where dominant social norms are challenged. Critical scholars such as Welton et al. (2018) stressed the importance of working for changed beliefs and values on the individual and institutional level. In antiracist transformation, double-loop learning demands that educators confront their own biases and challenge the systemic structures that perpetuate racial inequities. To inspire teachers and staff toward racially equitable practices, leaders must constantly reevaluate and examine their transformational leadership skills and capacity to maneuver challenging tactics. This requires a transformational systemic approach that changes the routines of the school and develops new dispositions and skills toward such goals. To inspire teachers and staff toward racially equitable practices, leaders must constantly reevaluate and examine their transformational leadership skills and capacity to maneuver challenging tactics. This requires a transformational systemic approach that changes the routines of the school and develops new dispositions and skills toward such goals. Examining the professional learning that occurs during the transformation process can provide insights into how leaders engage in a systemic approach toward dismantling racial inequity, and, as DiAngelo (2021) and Sue (2016) point out, prepare for and navigate situations where white fragility may hinder progress. Therefore, we argue that transformative leadership must happen at multiple institutional levels (Spillane and Camburn, 2006).

In summary, antiracist district transformation requires a multifaceted approach that integrates transformational leadership, organizational learning, and a deep understanding of the historical context of systemic racism in education. Transformational leaders can inspire and empower educators to challenge existing inequities, while double-loop learning can facilitate the critical reflection and systemic change necessary to dismantle racist structures and practices. Combining these theoretical frameworks allows school districts to create a more just and equitable educational system for all students. This study examines how Dublin Public School District leaders engage in professional learning to transform their understanding of racialized organizational structures and promote double-loop learning. Ultimately, this research provides insights into how district-wide professional development can foster transformative leadership and dismantle systemic school inequities.

Conclusion

This literature review has explored the interconnectedness of racism in education, transformational leadership, and organizational learning theory. As the history of racism in education demonstrates, systemic inequities are deeply embedded in the structures and practices of schools (Anderson, 1988; Du Bois, 1903, 1935). To dismantle these inequities, leaders must embrace transformational leadership principles, inspiring and empowering others to challenge the status quo (Leithwood and Jantzi, 2008). However, transformational leadership alone is not enough. Leaders must also foster a culture of organizational learning, where individuals and teams are encouraged to question existing assumptions, challenge ingrained practices, and experiment with new approaches (Diem and Welton, 2020; Senge, 1990). By integrating these three frameworks, this study offers a more comprehensive understanding of how antiracist district transformation can be achieved. In essence, this research posits that antiracist leadership requires a transformational approach that creates double-loop learning, allowing for continuous reflection and change to equitable district transformation.

Materials and methods

To study the role of professional learning on school and district-level leaders to influence an antiracist district-wide transformation, we drew on data from a longitudinal case study of one urban-intensive (Milner, 2012) district in the Northeast, which we call Dublin Public School District. (The district, schools, and all participants’ names are pseudonyms.) Our research design capitalized on a multi-year university-district partnership that occurred over the 2021–2023 school years. This study is part of a larger inquiry that examines how a large urban intensive school district engages in an antiracist transformation.

Setting

Dublin Public School District serves over 6,000 students in a large, urban-intensive city. More than 80% of the school’s students were classified as low-income. Northeast serves approximately 25,000 students in pre-K through 12 grades, across 50 schools. The district’s body was diverse: 70% Latino, 20% African American, 6% Asian, and 5% Caucasian. DPSD currently has a median household income of $40,000, a mere $10,000 over the national poverty line despite being one of America’s top 10 wealthiest states.

The former superintendent began the antiracist transformation process because of the murder of George Floyd and subsequent murders of Breonna Taylor, Sandra Bland, Ahmad Aubrey, and several others that also spurred the Black Lives Matter protests in the summer of 2020. Heavily affected by the murders, the superintendent met with local universities to engage in a multi-year commitment to spur racial equity across their district. Like several districts across the U. S., Dublin Public Schools (DPS) has an over-representation of White women teachers and leaders despite having a demographic of primarily Latinx, Black, and Bangla students. The superintendent, herself a White woman, realized that the racial inequities occurring in her district had to change. Thus, she committed her last years as superintendent to a racial equity transformation.

The antiracist professional learning series

From 2021–2024, Dublin Public Schools District and the University designed a multi-year professional learning series about antiracist and transformational leadership. The professional learning aimed to equip district and school-level leaders with the understanding, knowledge, and leadership skills needed to foster antiracist environments and promote academic achievement among students. The first author exclusively delivered professional learning to Principals, Assistant Principals, Deans, operational supervisors, and all district leaders, including both instructional and non-instructional staff. The professional learning sessions took place four times a month. The first two meetings were an hour long and included principals and district leaders. Additionally, principals met with their district supervisor twice monthly at their division level (elementary/middle and high school). These meetings were only for instructional leaders. The fourth meeting of the month was 2 h long and involved all district assistant principals, coaches, and district instructional supervisors. All sessions were conducted via video conference.

During these sessions, participants learned about various topics such as equity-oriented practices, equitable data-driven practices, cogenerative dialogues, and antiracist leadership and policy. These topics were presented using materials from reputable sources such as Galloway and Ishimaru (2015), Fergus (2016), Emdin (2016), and Welton et al. (2018). Participants demonstrated their learning by setting equity goals at the start of the 2021 and 2022 academic years. They also contributed to developing a district-wide antiracist and equity-oriented definition for their stakeholders. Additionally, they engaged in protocols to facilitate learning, including Expeditionary Learning (2024), Power of Protocols by McDonald et al. (2015), and Harvard Project Zero (2013). At the end of every academic year of professional learning, leaders responded to their progress on the antiracist transformation and how they felt their capacity had developed over the year. The first author met with the district assistant superintendents every summer to collaborate on designing the upcoming year’s plan. They made adjustments to the original plan as needed during these meetings.

Data collection

This particular study uses the data from the interviews with seven school and district leaders, including principals and content supervisors. The sample varies in age, race, and gender (see Table 1). These leaders were recruited through announcements and emails sent across the district to investigate, through interviews, how leaders expressed transformational leadership during the antiracist district-wide transformation. District and university IRB authorizations collected data at the end of the 2023 school year.

Table 1

| Leader | Level | Years of experience | Racial or ethnic background | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sandra | Principal | 8 | Black Latina | Female |

| Dale | Principal | 12 | Black | Male |

| Martina | Principal | 10 | White | Female |

| Ann | STEM Supervisor | 5 | White | Female |

| Sinclaire | Arts Supervisor | 2 | White | Female |

| Sharon | Math Supervisor | 2 | White | Female |

| Ronaldo | Special Education Director | 1 | Black | Male |

Participants demographic.

Interviews were conducted using a semi-structured protocol to uncover how the professional learning series informed their transformational leadership. The interview method was appropriate to gather in-depth data on principals’ responses and experiences to professional learning (Knight and Arksey, 1999). The interview protocol was organized around three topics: professional learning, equity leadership, and expressions of transformational leadership related to the district initiative.

Positionality

As a research team, we recognize that our perspectives and experiences as researchers and practitioners can influence the research process. To address this, we engaged in ongoing dialogue and reflexivity throughout the study, critically examining our assumptions and biases and how they might shape the data collection and analysis. We acknowledge that these relationships and perspectives may have influenced the types of questions we asked, the way we interpreted the data and the conclusions we drew. To mitigate potential biases, we employed several strategies, including member checking with participants, peer debriefing with other researchers, and triangulation of data sources. Our collective experiences with educational leadership, equity work, and our own racial identities inform both our approach to this study and our interpretation of the findings. We remain critically aware of our positionalities and have engaged in ongoing reflexivity throughout the research process. By engaging in these practices, we sought to enhance the credibility and trustworthiness of our findings.

Data analysis

All interviews were first transcribed and then coded using Atlas.ti. Our data analysis involved three stages, guided by the theoretical frameworks of transformational leadership (Bass and Riggio, 2006) and single/double-loop learning (Argyris and Schon, 1978). In the first stage, we identified all interview excerpts where leaders described their leadership practices, reflections on their assumptions, and experiences with professional learning. Initial codes focused on capturing instances of transformational leadership behaviors (idealized influence, inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, individualized consideration) and indicators of single and double-loop learning (adjustments to actions vs. questioning underlying assumptions). These initial codes were derived directly from the theoretical constructs outlined by Bass and Riggio (2006) and Argyris and Schon (1978), respectively. We also used a code for “professional learning” to identify data related to the impact of the professional development experience.

In the second stage, we generated reports through Atlas.ti of all data coded under the initial codes. The first author then engaged in open coding (Glaser, 1965) to identify emergent themes related to how leaders were enacting transformational leadership and engaging in single or double-loop learning in their districts. For example, under the code “inspirational motivation,” we examined how leaders articulated a vision for change and inspired others to commit to it. Under the code “double-loop learning,” we looked for evidence of leaders questioning their own assumptions and values and making fundamental changes to their practices. Example codes used to identify areas related to transformational leadership were “Modeling Equity,” “Inspiring a Vision,” “Collaborative Culture,” and “Distributed Leadership,” whereas areas that focused on single and double-loop learning included “Challenging Assumptions,” “Reframing problems,” and “Seeking new perspectives.”

After this reading, we constructed analytical memos (Saldana, 2011) to explore the interrelationships among these themes. Specifically, we examined how the professional learning experience facilitated transformational leadership and promoted single or double-loop learning. For example, one memo explored how participation in the professional learning series helped leaders to question their assumptions about student achievement and to adopt more equitable grading practices. Data were then aligned to our theoretical framework from both TL (Bass and Riggio, 2006) and Single/Double Loop Learning (Argyris and Schon, 1978).

In the third stage, we then applied Boeije (2002) constant comparative analysis to evaluate participant similarities and differences. As part of this process, the two authors independently coded transcripts and then met to discuss coding and find agreement. These analyses showed what leaders did to promote more equity-driven decisions. The codes were then analyzed and showed leaders’ insight into how professional development was used to elicit change. These codes from the four dimensions of TL and the data from leaders’ insight showed us how professional development helped their leadership practices, which are further developed in the findings below.

Findings

Leveraging leadership to influence structural transformation

Participants in this study consistently demonstrated leveraging their formal leadership positions to initiate structural changes, particularly by fostering double-loop learning among faculty and staff. This finding highlights a practical application of transformational leadership, wherein leaders utilize their influence to challenge existing assumptions and promote a shared vision of antiracist education. While some changes reflected single-loop learning – such as adjustments to grading systems or discipline policies – leaders consistently aimed for deeper, more transformative shifts in mindset.

Some examples leaders gave us were changing grading systems, discussing the discipline policy, or writing an equity statement. However, we found that all leaders engaged in double-loop learning to challenge underlying assumptions and mental models with faculty about student learning and equity. From the data, the leaders used the professional learning to be reflective, challenging their assumptions and beliefs as to why they held prior beliefs and assumptions about their students and looking for improvements that countered the deficit framing of students. Sandra’s reflection underscores the challenging yet essential nature of this work:

What I see in the school is that we have the desire to change things, but it also reminds me what a hard thing it is to do (racial equity transformation). I didn't just get here. It took so long to just, you know, kind of even have a conversation about identity or race. Not now. Understanding why is this happening in this way, and to me in particular, or to people that look like me, or to people that speak like me, instead of thinking that this has nothing to do with the social structure. So, I think that that has been major, being able to have, like a clear understanding in terms of my social identity, and how I identify myself as well within the district.

Sandra’s emphasis on understanding the ‘why’ behind inequities and connecting personal experiences to broader social structures is evidence of double-loop learning, demonstrating a critical examination of the systemic forces at play.

Leaders also demonstrated transformational leadership by integrating racial equity into existing structures, such as Professional Learning Communities (PLCs). Leaders in the sample clearly stated that there were barriers to infusing antiracist practices but found ways to weave them through formal professional learning structures such as PLCs. The mathematics supervisor shared:

There is a school where if I told them that antiracism and culturally relevant teaching were my focus, the principal and vice principal might not be thrilled because they see it (equity and math instruction) as separate. But I don't frame it as separate because I don't believe it is. I tell them that my PLCs are on small group instruction.

She continued:

I chose to provide information about small group instruction centered on what needs to be centered on because we can do 100 different things during whole class instruction, but what we choose to share is inherently an equity issue. We talk about that we shouldn't be politicizing math class but that's a political decision. I say to the teachers, "Listen, here are the mathematical tasks, and all of them are curated through a social justice and equity lens.” High-quality instruction is also an equilibrium, right? Making sure that our children can move on and go to college or a career of their choice is part of the inequity issue and if we just love them to pieces, but don't teach them, that's inequitable!

The mathematics supervisor highlights the notion of engaging in systems and processes that advance the antiracist transformation. Moreover, the supervisor shows how she conceptualizes the layers of equity by identifying that you need more than a kind heart (Ishimaru and Galloway, 2021) to systematically transform an inequitable system. This finding aligns with Ray (2019), demonstrating that individuals’ racial schemas activate when organizations transform and engage in racial equity efforts, thus showing how they conceptualize tangible change.

During the interviews, all the leaders expressed how they viewed themselves through a racial lens. When asked about their willingness to contribute to professional learning about sensitive topics such as racism and xenophobia as part of the transformation, the STEM supervisor shared,

I think I'm selective about what I share from my own experience. I'm less selective about what I might, you know, respond to if it's something I feel like somebody needs to get called out. But when we're asked to personally share a story or a reflection. I will think, "What do I want to say?" Because I know all the things that might be happening in terms of my colleagues' perceptions of me. So, I'm more likely to share some of those things in a small setting because I may have more of an opportunity to be able to provide clarity.

The STEM supervisor, who is a White woman raised in the inner city of Dublin, expresses a duality of perceptions versus lived experiences and an understanding that she is an outsider insider (Thomas, 2019) but also holds racial privilege. In contrast, Dale, a Black male principal who served in the district for over 12 years as a school leader, shared that during professional learning, he is not worried about contributing or providing constructive feedback, expressing, “They know who I am, my work speaks for itself after all these years.” Instead, he used the learning to reconsider his role in the transformation by challenging the racial and ethnic diversity of administrators. He explained,

I believe that if we are a district that has twenty-nine thousand students, and over seventy percent are Hispanic or LatinX, and we don't have one or two Hispanic or LatinX district administrators, we have a fundamental problem. Do we really want relevant leadership? We can talk the talk but if you want to change, you have to step out there and show that you want to be the change and be committed to the change. Once people see that you're committed to the change, you can influence them and bring them along.

Like the other leaders in the study, Dale explained their awareness of the district’s inherent inequities and the structural ways they were influencing change by engaging with colleagues or disrupting policies.

Further, leaders in the sample expressed they adjusted their leadership toward an antiracist orientation based on the tactics they learned from the professional learning series. Leaders who were previously in the district demonstrated an awareness of the change efforts by naming how the district was changing and adjusting toward an antiracist orientation. As district supervisor Ann stated,

I left the district for about 2 and a half years. Then, the district's vision was to put these goals in place. Those are the things that we are supposed to be doing, but then there's what was happening. You had a handful of really committed people, and everybody else was being pulled along, and that handful of people who are really committed were working. You know the district is large enough that their roles are disparate enough that they're not often able to pull together to work on things intentionally together. Now, I think there are still a lot of barriers, and some of that is about the size of the district, and some of that is about people's willingness to change. But now we think about how there will be systemic changes in the way that you have conversations and the way that we schedule PD. But also, how principals schedule kids. You have to think about how you're going to create safe spaces for conversation and how you're going to train people to continue to have those conversations. There are places where you know there are challenges because you can foresee that right, like, you know, for a calendar year or over a series of years. Where are the times where you run into stressors because you're talking about different issues or coming up against different things that either are happening within the school environment or out in the community environment that cause pressure points. And how do you acknowledge that and plan for it so that you're being proactive about engaging in conversation leading up to it, rather than being in the space of having to react, which doesn't leave you the time right to do what you want to do?

The awareness of the change efforts and how they affect racial equity provides an understanding of how leaders recalibrated their leadership to engage with the transformation. Moreover, it appears from the data that the reflective nature of where the district was, where it is headed, and their own racial identity allowed them to continue implementing change efforts. The facilitation of the professional learning series has reinforced the leaders’ commitment to the antiracist transformation. Sandra said simply, “The conversations we are having are very different.” Some of the district-level leaders’ change in role allowed them to reinforce racially equitable practices such as disaggregating data to drive instruction, implement culturally relevant strategies, and have discussions based on their observations. The data suggests that because of the participants’ formal role, they could make structural changes. Special Education Director Ronaldo explained,

I've been in this role for just a short period of time. But there are certain observations that I have made, for example, in the self-contained area. I'm noticing that I was talking about high expectations when I have PLCs and grade level meetings, and some teachers would say things like you're asking us to improve student engagement in the classroom, but sometimes some teachers will say, oh, but they (the students) are functioning on such a lower level. So I bring data into the conversation. I think data can help us and drive instruction and expectations. We now disaggregate data, and teachers are revamping their lessons and instructional strategies.

Similarly, Mathematics Supervisor Sharon expressed that the professional learning reinforced her use of her role to implement racial equity strategies, such as dealing with skepticism and push-back.

The professional learning series was good for me in many ways because it prepared me for my role. The joy of the new role is that they are less likely to push back because I observe them (teachers). But the other is kind of anticipating the things that create push-back, and then overcoming those objections before you get there, right? I started a PLC that I led last week where I expected some skepticism, and so I started it with, "I know that culturally responsive teaching is something that all of you care about because I know that you care about all of your students, and you believe that they can be successful."

The supervisors all expressed that their role’s formal authority allowed them to engage in the antiracist transformation by using formal structures such as observations and learning communities. This also shows how unintentional learning outcomes of professional learning provide insights into how leaders use the learning to forge ahead and transfer what they learned to their leadership practices. Additionally, because of professional learning, leaders are modeling what they have experienced, thus incorporating high-leverage equity-oriented practices to engage in sustainable change.

Fostering double loop outcomes through professional learning

We found that instead of leaders engaging in professional learning to mitigate single-loop outcomes, such as the cause and effect of an equity issue, leaders used the knowledge and skills gleaned during the professional learning to foster double-loop outcomes. The examples below illustrate how district and school-level policies and other factors influence academic results, faculty retention, and teacher satisfaction so that they can adjust in the future.

The data also suggests that leaders described the difference between double-loop learning and their first-year learning, which expanded their capacity and had them identify single-loop outcomes that focused on discrete actions for intended results to encourage antiracism. Special Education Director Ronaldo explained that in the first year, the professional learning allowed him to learn how to foster antiracist efforts by becoming more tolerant of his colleagues.

During the professional learning, I wondered, how do we embrace everybody by having tolerance for all? So, even though I may be, you know, from a certain religious background, I try to stay neutral with everybody, and I know sometimes people say you can't please everybody and can't make everybody happy. But my thing is, I can respect everybody. I can have tolerance, and I can have respect for everybody, and that's what I try to when I'm going to different schools and different platforms and different meetings. I try to always keep that in mind.

Ronaldo’s comments express the notion that school culture is a necessity to consider when considering inclusive schools. Research has shown that students thrive when school culture is built under antiracist principals. For example, leaders such as Principal Martina described how the professional development schedule hindered further progress. She explained,

The professional development schedule is brutal. Also, the fact that I don't have common planning built into my schedule every day, which is something we're working on for next year because when you have a professional development session where you're working with only a couple of people each period, it like you're shackled to your computer, because there are so many sessions to get everyone. But I would love to be like Fridays is our PD Day so everyone could learn together.

Martina’s comments provide insight into how leaders began to think about issues in their schools, such as lack of racial equity literacy. Although leaders initially expressed their desire to make changes based on surface-level problems, they also noted how professional learning increased their awareness of systemic problems. Further, the data suggests leaders moved into a space where, after the first year, they felt more confident, knowledgeable, and committed to the antiracist transformation, moving into double-loop learning in their schools. Martina discussed how she thought about the programmatic features and the systemic barriers in place at the district level to make the program more inclusive. She explains,

I'm like, this (academic program) can be done where everyone, including your resource and inclusion, special education students, and ELL students, can participate. Because why are we going to spend all this money and have this grade program? If not, everybody benefits from it.

Leaders in the data set explain that after engaging in professional learning about antiracist leadership (Welton et al., 2018), they investigated the programs within their school and across the district to make systemic changes. For example, Sandra said,

There is a true investment. Before, we couldn't say Black or White or anything about race, and that hindered our progress from being antiracist. It is not just a theory, right? It (antiracism) is something that you live, and you implement it. It has to connect to practice, right? So it is that connection that you don't lose sight of. It's not only let's have great conversations because the conversations have to be enacted. You have to see it, realize it. One way we have changed is providing feedback on the teachers' culturally relevant pedagogy instructional delivery. We have to include a teacher's praxis. I have to continue providing feedback, like the support system that you put in place for teachers. We have to have a comprehensive system.

After 2 years of learning about antiracist leadership, Special Education Director Ronaldo started questioning the educational landscape of the district about the systemic issues faced by urban schools across the country. He aimed to bring antiracist efforts to his role and work with the teachers. In Ronaldo’s own words,

The school systems, the educational landscapes, you know, imagine the equity and the quality of instruction, and everyone would feel like this is a place where, hey? I can come, and I can learn something. I may not be as smart as that, or I may not get the same recognition as this, this one, or that one. But this is a safe environment. This is an environment that I feel comfortable in. And hey, I just may learn something, and that's what I want to. You know. That's the atmosphere that I want in all my schools.

According to the data, school leaders who completed their first year of professional learning moved on to challenge the systems and norms of the schools and district to facilitate antiracist practices.

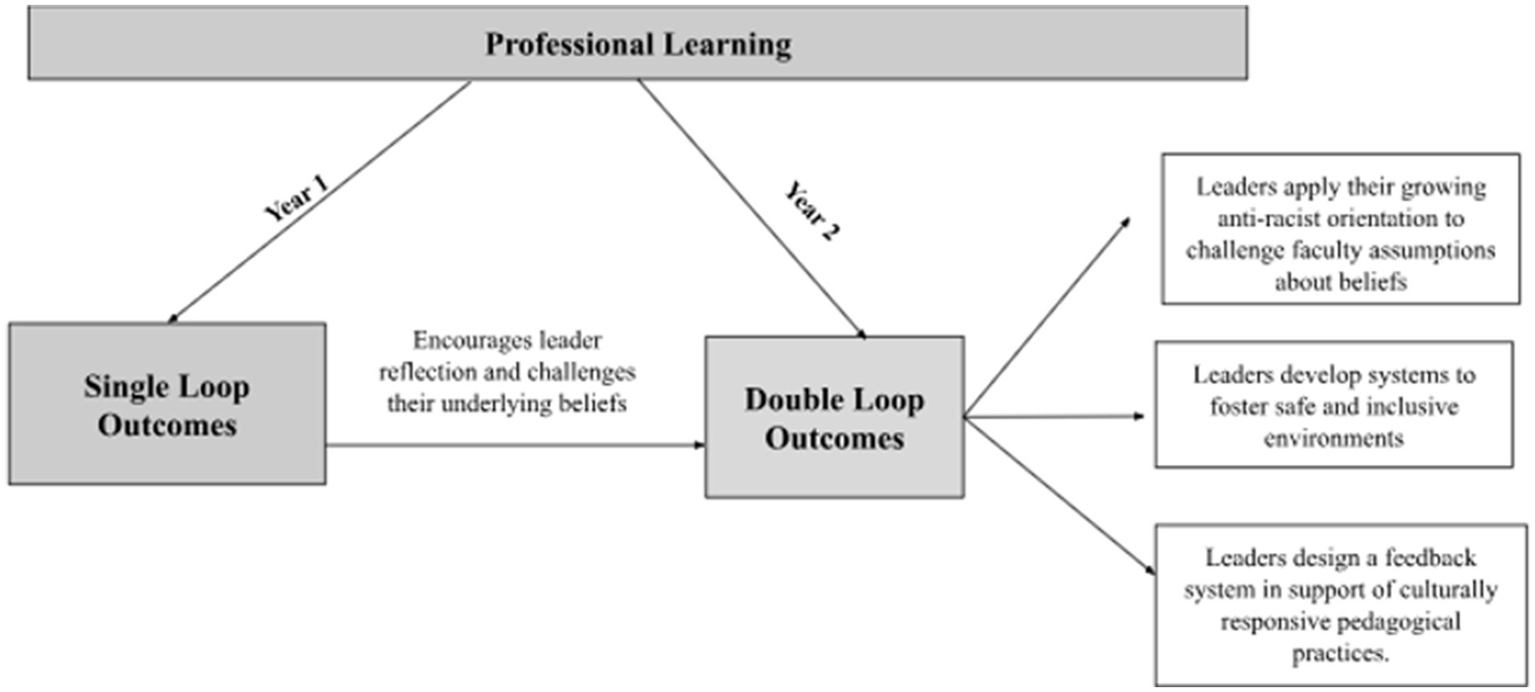

Based on the data analysis and the resulting findings, we created Figure 1 to illustrate how the leaders in the sample expressed how professional learning fostered antiracist leadership and then executive double-loop outcomes such as fostering a safer environment, increasing accessibility to programs, and improving feedback loops for teachers to support their growth and development in culturally relevant practices.

Figure 1

Conceptual framework illustrating the relationship between professional learning and educational outcomes.

Limitations

This study includes limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, the sample size of 7 district and school-level leaders from a single urban-intensive school district allowed for in-depth exploration of individual experiences and perspectives, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other contexts (Miles and Huberman, 1994). However, the sample size was deemed appropriate given the study’s exploratory nature and the focus on understanding the nuances of antiracist district transformation within a specific context (Creswell and Clark, 2017). The findings are specific to the context of the Dublin Public School District, which may have unique characteristics that influence the implementation of antiracist initiatives. Future research should explore the transferability of these findings to other districts with varying demographics, organizational structures, and community contexts.

Discussion and conclusion

The distinction between Single-Loop and Double-Loop Learning was first published nearly fifty years ago (Argyris, 1977). Two decades later, the field of school leadership began to explore constructs of change leadership (e.g., Elmore, 1999), soon framed as Transformational Leadership (Hallinger, 2003). The idea that school leaders can bring antiracist transformation to their schools has percolated for over 30 years (e.g., Enid Lee, 1991) but has become central to school leadership discourse only in the past decade (Welton et al., 2018; Gooden et al., 2023). The urgency of antiracist leadership has been fueled by the Black Lives Matter movement beginning in 2013 and accelerated by the murder of George Floyd in 2020. Each of these three theoretical perspectives plays a role in understanding what took place in the Dublin School District from 2021 to 2023.

Several key conclusions can be drawn from the Dublin case. First, district leadership mattered in the effort to bring about antiracist change in Dublin. The White superintendent saw a need, brought in external expertise to help meet that need, and allocated resources and commitment to sustain the effort over time. This finding aligns with research by Leithwood and Jantzi (2008), who emphasized the critical role of district leaders in creating the conditions for school improvement. However, our study extends this research by highlighting the importance of the superintendent’s commitment to antiracist change, creating a sense of urgency and legitimacy for the initiative.

Second, despite everything we know about how difficult it is for people to change their beliefs and values, Dublin leaders at various levels reported shifts and growth in their mindsets and the culture of Dublin schools. In various leadership roles, Dublin school and district leaders were provided with a structured and sustained professional learning opportunity that explicitly sought to equip district and school-level leaders with the understanding, knowledge, and leadership skills needed to foster antiracist environments and promote academic achievement among students. The experience engaged them in reading, discussing, and collaboratively reflecting on material from the antiracist and transformational leadership professional knowledge base. Dublin leaders reported specific and compelling results from their professional learning experiences in three areas of inquiry: professional learning, equity leadership, and transformational leadership related to the district initiative. For example, one principal noted, “Before the professional learning, I did not fully understand the impact of implicit bias on my disciplinary practices. Now, I’m much more aware of my own biases and how they affect my interactions with students of color.” This finding supports previous research by Welton et al. (2018), which suggests that professional learning can effectively promote equity leadership. However, our study adds to this body of knowledge by demonstrating how specific design features, such as sustained engagement and collaborative reflection, can enhance the effectiveness of professional learning.

Third, the professional development experience was designed to support the Dublin leaders in double-loop learning, using the opportunity to challenge and reflect on underlying assumptions and mental models about student learning and equity with their faculty. This double-loop learning led directly to systemic changes in organizational functions within schools, such as providing feedback to teachers on their culturally relevant pedagogy and supporting teacher growth. Leaders reinforced their commitments to antiracist change and aligned their practices accordingly. In addition, the double-loop learning experiences caused leaders at multiple levels to question and challenge some of the established systems and structures of the district in constructive ways. These included raising questions about the district’s established routines and practices in professional development. This finding is consistent with Argyris (1977) double-loop learning theory, which posits that challenging underlying assumptions is essential for promoting systemic change. However, our study provides empirical evidence of how this process can unfold in the context of antiracist district transformation, demonstrating that leaders can use double-loop learning to identify and dismantle inequitable policies and practices.

Finally, just as district leadership mattered in the Dublin experience, so did the quality of antiracist professional development. A White superintendent with limited expertise in antiracist change brought in a university partner who could offer (a) the personal attributes of coming from a Black/Latina background and a commitment to antiracist change; and (b) the professional attributes of having been an experienced school leader, an experienced staff developer, and a scholar with a learning stance toward the emergent literature on antiracist school leadership. This finding highlights the importance of selecting professional development providers with expertise in antiracist practices and a deep understanding of the local context. Furthermore, the fact that the superintendent was White suggests that leaders do not need to have personal experience with racism to effectively champion antiracist initiatives, provided they are willing to partner with experts and commit to ongoing learning (Khalifa, 2020).

Recent years have seen a sharp growth in the literature on equity-centered, race-conscious school leadership (e.g., Welton et al., 2018) and principal preparation programs that prepare antiracist school leaders (Waite (2021); Young et al., 2022). Few empirical studies, however, have demonstrated the impact of in-service professional learning on antiracist, transformational leadership. While the case study method yields insights, not generalizations (Stake, 1997), this study demonstrates an instance of leaders transforming their thinking and practice to become more effective as antiracist leaders in their schools.

The study suggests that accomplishing these changes required (a) district leadership willing to commit resources to change over time, in this case, a period of at least 3 years; (b) expertise at selecting appropriate materials and facilitating reflective discussions of these materials, in this case, provided by a university partner; (c) collection of annual data to document and monitor participants’ perceptions of the professional learning experience. It is plausible to expect that these elements could be replicated in other settings and that additional research on such efforts could further inform the field. In conclusion, this case study of the Dublin School District provides valuable insights into the complex process of antiracist district transformation.

Our findings suggest that a combination of visionary district leadership, high-quality professional learning, and a commitment to double-loop learning can create the conditions for meaningful change. While this study is limited by its scope, it offers a compelling example of how schools can begin to dismantle systemic racism and create more equitable learning environments for all students. Future research should explore the long-term impact of such initiatives and examine the role of community engagement in sustaining antiracist change. This focus on research and practice in professional development for practicing leaders is significant because the growth of antiracist leadership preparation practices is relatively new to the field and would be expected to affect a relatively small percentage of new principals annually. As a complement to pre-service practices, in-service practices of antiracist, transformative leadership development could have a much-needed effect on leaders, teachers, and students in those districts where such professional development occurs.

Transformational leadership revisited: addressing critiques through practice

Our study’s findings directly address several critiques of transformational leadership (TL) raised in the literature, particularly the need for dynamic, contextually responsive, and collaboratively constructed leadership.

Traditional models of TL often emphasize a set of static traits or behaviors. In contrast, our findings demonstrate that effective antiracist leadership is highly adaptive and evolves in response to the community’s unique needs, histories, and challenges. For example, participants described how their professional learning experiences prompted continual self-reflection and adjustment of their leadership practices. Leaders engaged in ongoing dialogue with stakeholders, responded to emerging resistance, and tailored their strategies to the district’s shifting context instead of relying on typical transformational leadership characteristics. Using the above-named practices aligns with the notion that transformational leadership in antiracist work must be a dynamic, iterative process rather than a fixed leadership style.

A key critique of TL is the risk of a leader imposing a singular, idealized vision. Our findings expand on this by showing that leaders in the study prioritized the co-construction of an antiracist vision with teachers, students, families, and community partners. Leaders facilitated open forums and advisory groups, actively soliciting diverse perspectives to shape the district’s goals and actions. This collaborative approach increased stakeholder buy-in and ensured the vision for equity reflected the lived experiences and aspirations of the entire community.

Finally, another critique is that TL can inadvertently reinforce existing power dynamics if not critically examined. Our study found that leaders intentionally worked to redistribute decision-making authority, elevate marginalized voices, and challenge inequitable policies. For example, leaders revised instructional review protocols to center cultural relevance and inclusivity and created new spaces for historically underrepresented groups to participate in policy discussions. These actions demonstrate a commitment to inspiring change and dismantling structural barriers to equity-a key evolution of transformational leadership in practice.

Although our data collection concluded in 2023, we have observed several early indicators of organizational change within the district. These include adopting revised disciplinary policies, increased representation of leaders of color in key roles, and anecdotal reports of improved teacher retention and student engagement. While it is too early to draw definitive conclusions about long-term outcomes, these developments suggest a positive trajectory. We acknowledge the limitations of our current data. Future research will continue to track these indicators and explore the mechanisms through which professional learning supports sustained antiracist transformation.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The studies involving humans were approved by Montclair State University Institutional Review Board. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

PV: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CA: Writing – review & editing. ST: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1

Anderson J. D. (1988). The education of blacks in the south, 1860–1935. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

2

Anderson M. (2017). Transformational leadership in education: a review of existing literature. Int. Soc. Sci. Rev.93, 1–13. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/90012919

3

Argyris C. (1977). Double loop learning in organizations. Harv. Bus. Rev.55, 115–125. doi: 10.1007/s10649-017-9776-1

4

Argyris C. (2003). A life full of learning. Organ. Stud.24, 1178–1192. doi: 10.1177/01708406030247009

5

Argyris C. (1999). “Tacit knowledge and management” in Learning as transformation: Critical perspectives on a theory in progress. eds. MezirowJ. R. and Associates (Jossey-Bass), 137–154.

6

Argyris C. Schon D. (1978). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

7

Bass B. M. (1985). Leadership: Good, better, best. Organ. Dynamics13, 26–40.

8

Bass B. M. Riggio R. E. (2006). Transformational leadership: Psychology Press.

9

Boeije H. (2002). A purposeful approach to the constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative interviews. Qual. Quant.36, 391–409. doi: 10.1023/A:1020909529486

10

Bristol T. J. Shirrell M. (2019). Who is here to help me? The work-related social networks of staff of color in two mid-sized districts. Am. Educ. Res. J.56, 868–898. doi: 10.3102/0002831218804806

11

Bryk A. S. (2020). Learning to improve. Stanford Soc. Innov. Rev. doi: 10.48558/4802-QT84

12

Busari A. H. Khan S. N. Abdullah S. M. Mughal Y. H. (2019). Transformational leadership style, followership, and factors of employees’ reactions towards organizational change. J. Asia Bus. Stud.14, 181–209. doi: 10.1108/JABS-03-2018-0083

13

Cochran-Smith M. (2004). The problem of teacher education. J. Teach. Educ.55, 295–299. doi: 10.1177/0022487104268057

14

Creswell J. W. Clark V. L. P. (2017). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

15

DiAngelo R. (2021). Nice racism: How progressive white people perpetuate racial harm. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

16

Diem S. Welton A. D. (2020). Antiracist educational leadership and policy: Addressing racism in public education. Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge.

17

Du Bois W. E. B. (1903). The souls of black folk. Chicago, IL: A. C. McClurg & Co.

18

Du Bois W. E. B. (1935). Black reconstruction in America: An essay toward a history of the part which black folk played in the attempt to reconstruct democracy in America, 1860–1880. New York: Harcourt Brace.

19

Dumas M. J. (2016). Against the dark: antiblackness in education policy and discourse. Theory Pract.55, 11–19. doi: 10.1080/00405841.2016.1116852

20

Elmore R. (1999). Leadership of large-scale improvement in American education: Albert Shanker Institute.

21

Emdin C. (2016). For white folks who teach in the hood. And the rest of y'all too: Reality pedagogy and urban education. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

22

Expeditionary Learning (2024) EL education. Available online at: https://eleducation.org/ (Accessed September 23, 2025).

23

Fergus E. (2016). Solving disproportionality and achieving equity: A leader's guide to using data to change hearts and minds. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

24

Galloway M. K. Ishimaru A. M. (2015). Radical recentering: equity in educational leadership standards. Educ. Adm. Q.51, 372–408. doi: 10.1177/0013161X15590658

25

Glaser B. G. (1965). The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Soc. Probl.12, 436–445. doi: 10.1525/sp.1965.12.4.03a00070

26

Goings R. B. Walker L. J. Wade K. L. (2021). The influence of intuition on human resource officers’ perspectives on hiring teachers of color. J. Sch. Leadersh.31, 189–208. doi: 10.1177/1052684619896534

27

Gooden M. A. Khalifa M. Arnold N. W. Brown K. D. Meyers C. V. Welsh R. O. (2023). A culturally responsive school leadership approach to developing equity-centered principals: Considerations for principal pipelines. New York: Wallace Foundation.

28

Grissom J. A. Egalite A. J. Lindsay C. A. (2021). What great principals really do. Educ. Leadersh.78, 21–25.

29

Guba E. G. Lincoln Y. S. (1994). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. Handbook Qual. Res.2:105.

30

Guskey T. R. (2002). Professional development and teacher change. Teach. Teach.8, 381–391. doi: 10.1080/135406002100000512

31

Hallinger P. (2003). Leading educational change: reflections on the practice of instructional and transformational leadership. Camb. J. Educ.33, 329–352. doi: 10.1080/0305764032000122005

32

Harvard Project Zero . (2013). With responses by Howard Gardner - project zero. Available online at: https://pz.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/gardner%20mind%2C%20work%2C%20life.pdf (Accessed September 23, 2025).

33

Ishimaru A. M. Galloway M. K. (2021). Hearts and minds first: institutional logics in pursuit of educational equity. Educ. Adm. Q.57, 470–502. doi: 10.1177/0013161X20947459

34

Jyoti J. Dev M. (2015). The impact of transformational leadership on employee creativity: the role of learning orientation. J. Asia Bus. Stud.9, 78–98. doi: 10.1108/JABS-03-2014-0022

35

Keating C. Robinson T. Clemson B. (1996). Reflective inquiry: a method for organizational learning. Learn. Organ.3, 35–43. doi: 10.1108/09696479610126699

36

Khalifa M. (2020). Culturally responsive school leadership. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

37

Knight P. T. Arksey H. (1999). Interviewing for social scientists: an introductory resource with examples. Interviewing Soc. Sci., 1–224. doi: 10.4135/9781849209335

38

Kozol J. (2005). Confections of apartheid: a stick-and-carrot pedagogy for the children of our inner-city poor. Phi Delta Kappan87, 265–275. doi: 10.1177/003172170508700404

39

Lee E. (1991). Letters to Marcia: A teacher's guide to antiracist education: Cross Cultural Communication Centre.

40

Leithwood K. Jantzi D. (2008). Linking leadership to student learning: the contributions of leader efficacy. Educ. Admin. Q.44, 496–528. doi: 10.1080/15700760500244769

41

Leithwood K. Sun J. Schumacker R. (2020). How school leadership influences student learning: a test of “the four paths model”. Educ. Adm. Q.56, 570–599. doi: 10.1177/0013161X19878772

42

Leonardo Z. Porter R. K. (2010). Pedagogy of fear: toward a Fanonian theory of ‘safety’in race dialogue. Race Ethn. Educ.13, 139–157. doi: 10.1080/13613324.2010.482898

43

McDonald J. P. Mohr N. Dichter A. McDonald E. C. (2015). The power of protocols: An educator’s guide to better practice. New York: Teachers College Press.

44

Middleton J. Harvey S. Esaki N. (2015). Transformational leadership and organizational change: how do leaders approach trauma-informed organizational change… twice?Fam. Soc.96, 155–163. doi: 10.1606/1044-3894.2015.96.21

45

Miles M. B. Huberman A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

46

Milner H. R. (2012). But what is urban education?Urban Educ.47, 556–561. doi: 10.1177/0042085912447516

47

Ogwumike I. Rangel V. S. Johnson D. D. (2022). The promise and pitfalls of transformational leadership for decreasing the use of out-of-school suspensions and reduce the racial discipline gap. Educ. Urban Soc.56, 230–259. doi: 10.1177/00131245221106710

48

Ray V. (2019). A theory of racialized organizations. Am. Sociol. Rev.84, 26–53. doi: 10.1177/0003122418822335

49

Saldana J. (2011). Fundamentals of qualitative research. London: Oxford University Press.

50

Senge P. M. (1990). The fifth discipline: the art and practice of the learning organization. New York: Doubleday/Currency, Chicago.

51

Shange S. (2020). Progressive dystopia: Abolition, antiblackness, and schooling in San Francisco. Chapel Hill: Duke University Press.

52

Singleton G. E. Linton C. Ladson-Billings G. (2006). Facilitator's guide: a field guide for achieving equity in schools: courageous conversations about race. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

53

Snell R. Chack A. M. (1998). The learning organization: learning and empowerment for whom?Manage. Learn.29, 337–364. doi: 10.1177/1350507698293005

54

Spillane J. P. Camburn E. (2006). The practice of leading and managing: the distribution of responsibility for leadership and management in the schoolhouse. Am. Educ. Res. Assoc.22, 1–38. doi: 10.1080/15700760601091200

55

Stake R. (1997). “Case study method in educational research: seeking sweet water” in Complementary methods for research in education. ed. JaegerR. M.. 2nd ed (Washington, DC: AERA).

56

Sternberg R. J. Horvath J. A. (Eds.). (1999). Tacit Knowledge in Professional Practice: Researcher and Practitioner Perspectives(1st ed.).London:Psychology Press. doi: 10.4324/9781410603098

57