- 1Department of Translation, Al-Zaytoonah University, Amman, Jordan

- 2Department of Applied Linguistics, Al-Zaytoonah University, Amman, Jordan

- 3Independent Researcher, Irbid, Jordan

In light of the challenges and crises the world is facing, the usage of technology has a significant impact on students’ perceptions and learning experiences. This study investigates the perceptions of Gazan university students toward online learning in the context of an ongoing crisis. Using a qualitative thematic analysis methodology, this study conducted semi-structured interviews with a random sample of fifteen graduate students (eight females and seven males) from Gaza University. It aimed to to shed light on Gazan students’ perceptions regarding online learning follwoing the events of October 7th to provide viable solutions that could help them receive appropriate education. The thematic analysis revealed several key findings. Students expressed both gratitude for the continuity of their education and significant frustration with logistical challenges, including inconsistent internet access and frequent power outages. The interviews also highlighted the psychological toll of the crisis, which often impeded their ability to concentrate and engage in online coursework. Students also have a positive perception regrding the convenient, on-demand access to lectures and course content that online learning provides. These findings underscore the dual nature of online learning in a conflict zone: it serves as both a critical lifeline and a source of new stressors. The findings are anticipated to have crucial practical implications for higher education institutions in Gaza, staff, policymakers, and the Ministry of Education aiming to design and implement strategic online education systems that are not only accessible but also resilient and supportive.

Introduction

Over the last few years, online learning has demonstrated its ability to enhance the educational process and facilitate the continuity of student learning in the face of the world’s challenges and exigencies. The contemporary world is experiencing an unparalleled phase of technological advancement marked by the swift development of innovative tools and systems (Alsharif et al., 2025; Khasawneh and Alsharif, 2025). A notable example is the widespread adoption of online education during the COVID-19 pandemic, which compelled educational institutions worldwide to shift to remote learning. Similarly, in the wake of the massive destruction inflicted upon Gaza, Palestinian higher education specialists and educators in institutions emphasized the need to continue learning online. This not only ensures students’ access to education but also enables them to maintain academic engagement with their peers and instructors.

Online learning serves as an important alternative for many students who are unable to attend traditional educational institutions. In the context of global crisis—including pandemics, armed conflicts, and natural disasters such as floods and earthquakes—online learning evolved into an emergency remote learning alternative, particularly following the COVID-19 pandemic. Emergency remote learning (ERL) is defined as the immediate transition from face-to-face learning to an online system due to unforeseen disruptive circumstances, where online learning is employed as the only viable option to continue the education process (Pratiwi and Priyana, 2022).

Online learning offers a practical alternative for students who are unable to engage in traditional face-to-face classes by integrating information and communication tools (ICT) to enhance educational services. It is characterized by its popularity, accessibility regardless of time or location, cost-effectiveness, and provides excellent flexibility and interaction (Maphosa, 2021). It is defined as a system that employs internet technology to provide information to students, enabling interactions through computer interfaces (Vitoria et al., 2018). Building on this, Jamil and Hamre (2018) describe online learning as a form of distance learning where the internet serves as the primary medium, replacing face-to-face interactions between students and teachers in a traditional classroom setting. Considerable research efforts have been directed toward the development of effective instructional strategies (Al-Shahwan, 2024). While several studies investigated online learning challenges and students’ perceptions, the majority of these studies focused on pandemic-related disruptions of COVID-19 or rural underdevelopment (Abich and Eriku, 2023; Almahasees et al., 2021; Inan Karagul et al., 2021; Lei and So, 2021). Meanwhile, other studies focused on general online learning challenges in more stable contexts (Gillett-Swan, 2017; Kearns, 2012; Song et al., 2004). These contexts, although challenging, differ fundamentally from active war zones such as Gaza, where students not only face inadequate internet connection and technological limitations but also continuous displacement, loss of educational institutions, and ongoing security threats.

Online learning is a teaching method that ensures content availability to students at any time, from any location, and regardless of proximity, thereby serving as a tool that enables more creative and student-centered teaching and learning activities. Students who engage in online learning have a different educational experience compared to those in traditional classrooms since their interaction occurs through online platforms and computers rather than face-to-face communication. This teaching method, facilitated by several online learning platforms, promotes both individual and collaborative learning among students. It encourages self-directed learning, reduces students’ reliance on their teachers, and allows them to learn at their own speed. Online learning is also considered a low-cost and more convenient option for students to access learning from any location and at any time, regardless of geographical proximity (Ayimbila et al., 2024).

While online learning offers many advantages, it still presents significant challenges for students that can disrupt their education process. Dube (2020) states that infrastructural limitations—such as unreliable networks—sometimes disrupt students’ communication with faculty members, while students’ limited technological proficiency further intensifies delays in accessing online sessions. These barriers make it difficult for students to participate in online lectures. Furthermore, the absence of essential digital resources, such as personal computers, smartphones, and tablets, poses another substantial issue with online learning. Bilinguals, such as the students in Gaza, exhibit complex interactions between languages (Alsharif and Khasawneh, 2025). This can create an additional layer of complexity in an online learning environment, where clear communication is crucial for effective learning. Academically, online learning is often perceived as less effective for the acquisition of practical skills, and faculty members find it challenging to assess students’ actual level of learning.

Students’ perceptions of online learning may be influenced by several factors, including their motivation, classroom interaction, course structural design, technology, internet issues, lecturer knowledge and expertise, and the availability of support from both instructors and colleagues (Saputra et al., 2022). Additionally, students often encounter various challenges within the online learning environment. These challenges include a shift in their engagement levels in class, their emotions and responses, the quality of their relationships with both faculty members and fellow students, and delayed feedback and assistance since faculty members are not always present when students need it during the learning process. Therefore, online learning can be less adaptable than supposed (MacIntyre et al., 2020; Tartari and Kashahu, 2021).

Literature review

Many scholars have addressed the challenges of online learning from students’ perspectives. Abich and Eriku (2023) explored the challenges of implementing online learning, identifying critical issues such as inadequate infrastructure, poor knowledge, and a lack of expertise in online learning that negatively affected the implementation of online learning. Similarly, Xia et al. (2022) addressed the challenges associated with online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Their findings suggest that a lack of engagement with faculty members, a deficiency in campus sociability, insufficient technological proficiency, and a lack of content tailored for online learning and group projects can collectively hinder the achievement of expected learning results. However, online learning simultaneously provides students with new opportunities to study independently, foster collaborative work, and enhance connections with their classmates. It prompts them to reassess how they can improve their communication, learning strategies, and technological skills, thereby transforming their roles as integral team members.

On the other hand, Saeedi et al. (2022) investigated the challenges of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic, identifying key barriers related to internet connectivity, interaction dynamics, and faculty members’ insufficient familiarity with online systems. Complementing these findings, Aboagye et al. (2020) concluded that students primarily faced challenges related to accessibility, internet connectivity, inadequate equipment, and social factors, including the absence of direct communication and contact with professors and classmates.

Moreover, Shuliak et al. (2024) studied how the war impacted Ukrainian students’ online education experience using a survey and questionnaire. The results showed that even in times of war, students are prepared to continue their education in order to obtain a qualification. In regard of the challenges they face during such time, students frequently face problems with motivation, and social, living, and technological distractions which might affect their academic performance. Hruzevskyi (2023) focused on the impact of the military conflict on the distance education system in Ukraine. They indicated that the sudden transition from face-to-face learning to online learning necessitated a significant overhaul of educational institutions. Students also had to adjust to new and unusual conditions during this process. Besides, online learning face many challenges which include the need for students to have strong self-discipline which may negatively affect their motivation and ability to provide the required learning environment, and the lack of direct interaction with the educational institution. Without face-to-face interaction, remote learning has been shown to be less successful.

Accordingly, it is imperative to highlight the critical role that online learning plays in maintaining the continuity of the teaching and learning process during national crises that obstruct conventional face-to-face learning, exemplified by the exigencies of the COVID-19 pandemic or ongoing situations such as those currently happening in Gaza. Furthermore, since online learning is a dynamic and complex process influenced by a broad spectrum of factors, scholars should focus on analyzing the learning process and outlining effective strategies and techniques to enhance students’ experience.

Statement of the problem

In a warn-torn environment, face-to-face learning is not a viable option as participants in the educational process are often physically displaced and dispersed across several regions. Consequently, online learning merges as crucial and important solution during such periods. This was confirmed by Artyukhov et al. (2023) who mentioned that the degree of security following the war, curfews, and internet access varies from one person to another making face-to-face learning an unappropriated option during wartimes. This highlights the necessity of shifting to online learning, a transition exemplified by Ukraine. Similarly, Hruzevskyi (2023) asserted that crises require those in charge of the educational process to adopt an innovative approach to online learning. They are forced to adapt to new realities and seek effective methods to ensure the quality of education under similar constraints.

These same dynamics were also observed in Gaza City, Palestine. Following the massive destruction inflicted upon Gaza City after the events of October 7th, marked by the widespread destruction of all universities and the tragic loss of numerous faculty members, students, specialists, and educators within higher education institutions, these establishments are no longer able to provide the essential educational services to students. Therefore, a decision was made to employ online learning and recruit volunteer faculty members from within Palestine and other countries such as Jordan, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and Tunisia, among others, to ensure the continuity of the educational process. This shift focal presented substantial difficulties for many Gazan students, who have been out of school for more than a year now. They must adapt to a new educational system and unfamiliar learning methods, engage with new faculty members from different backgrounds and teaching styles, and manage limited access to essential learning resources and support mechanisms.

Therefore, it is essential to shed light on the perceptions of Gazan students regarding online learning in the aftermath of October 7th to provide viable solutions that can help them receive an appropriate education. The sudden and inadequately planned implementation of online learning in this context has given rise to several significant problems and challenges.

Significance of the study

This study holds significant and practical implications from its exploration of Gaza university students’ perception of online learning following the events of October 7th. While much of the existing literature on online learning focused on challenges during Covid-19 pandemic or in resource-limited settings (Abich and Eriku, 2023; Gillett-Swan, 2017; Kearns, 2012), little research has investigated how students navigate online learning under conditions of active conflict, trauma, and the destruction of educational infrastructure. By documenting these experiences, the findings from this study are anticipated to have crucial practical implications for universities in Gaza, aiming to optimize their online learning policies. By providing a comprehensive understanding of how online learning affects both students and faculty members, the study can help specialists and educators in higher education institutions develop strategies to enhance online learning environments for both students and faculty. Furthermore, it provides valuable insights for policymakers, and humanitarian organizations working to sustain higher education in war-torn regions. Furthermore, these insights can also assist in designing effective training programs that equip faculty members with the required skills for effective and successful online learning.

Moreover, this study serves as a stage for future research into online learning effectiveness within similar circumstances, such as the prolonged situation faced by Gaza over 468 days. It addressed existing gaps by providing a detailed analysis of how online learning influences students’ ability to continue learning, particularly in light of their challenging living conditions. Future researchers can build upon this work to explore online learning dynamics under different and evolving conditions.

Limitations of the study

The current study has several limitations, primarily stemming from its confined scope: it was conducted on a limited number of Gazan students and during a specific ceasefire period. Consequently, the results may not comprehensively represent the broader characteristics or generalizability of the online learning systems currently employed by universities within Gazan. Therefore, to comprehensively identify the challenges and opportunities and to generalize the efficiency of online learning implementation across the city, future researchers should conduct more extensive investigations involving a larger and more representative sample of Gazan universities.

Methods and procedures

Methodology

The current study employed the thematic analysis method to achieve its objectives, primarily using semi-structured interviews for data collection. In line with this methodology, Dawadi (2020) outlined that thematic analysis method is a qualitative research technique that researchers employ to methodically arrange and examine large, complicated data sets. It involves looking for themes that can capture the narratives found in the data sets. It entails carefully going over and rereading the recorded data to identify themes.

Sample of the study

The study sample included fifteen graduate university students (eight females and seven males) enrolled at Gaza University in Gaza City. Participants were selected using a random sampling method to avoid bias, as the first author works as a volunteer faculty member teaching university students in Gaza following the events of October 7th and after the ceasefire agreement on January 15th, 2025. The researchers contacted several students online via WhatsApp, where a pre-prepared set of questions aligned with the study’s objectives were posed to participants after they had been informed of the ethical considerations and given consent to participate in the study voluntarily. Participants were explicitly assured that their participation in the study was entirely voluntary and that they had the right to withdraw at any point. Additionally, participants’ identities and responses assurances would be treated with strict confidentiality in all research reports.

Data collection process

The data for this study was collected using semi-structured interviews that include open-ended questions designed to achieve the study’s objectives and gather data on students’ perceptions of online learning by reviewing a set of studies that address online learning (Artyukhov et al., 2023; Saputra et al., 2022; Saeedi et al., 2022). Questions included: “What are the benefits and challenges of online learning?, Do you think that the lack of engagement and participation affects the understanding of the learning content?, In your opinion, under current conditions, do you consider the offered online learning to be positive and beneficial? Why?.” The interview questions were presented to a jury of (3) specialized members of faculty members specialized in educational administration and fundamentals, and teaching methods. These experts were asked to evaluate the questions for clarity, flow, and overall appropriateness, and to provide any important remarks to enhance the instrument’s validity.

All interviews were conducted by the first author in Arabic, the official language of Palestine. This methodological decision was made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the participants’ answers by eliminating potential misunderstanding that could arise from translation. Using the native language facilitated open and free expression, enabling students to respond without hesitation and ensuring that their opinions were expressed freely. This approach mitigated the risk of participants misinterpreting questions or providing inaccurate answers, thereby strengthening the credibility of the research findings.

Given the open-ended nature of the questions, the interviewer may ask participants to elaborate further as needed. Data collection continued until thematic saturation was achieved, with no new themes or information surfaced from subsequent interviews. In light of the current circumstances in the region, the interviews were conducted via WhatsApp audio recordings. After obtaining students demographic information (gender and specialization), the first author started the interview by providing participants with the questions. This method allowed students to respond at their convenience, accommodating potential challenges such as unstable internet connections and other personal circumstances. The use of an asynchronous, flexible format ensured that all participants had sufficient time to provide thoughtful and comprehensive answers, thereby enhancing the quality of the data collected.

Method of data analysis

The thematic analysis method was employed to analyze the interview transcripts within this descriptive qualitative study. The analytical process followed the systematic steps outlined by Clarke and Braun (2013):

1. Data Preparation: The initial step involved transcribing the interview’s central questions and participants’ verbalizations to prepare the raw data for analysis.

2. Developing Categories and a Coding Scheme: This step entailed the systematic development of categories and a coding scheme directly derived from the data. The primary objective was to organize and classify information into coherent, unified categories or specific types. This involved methodically coding the main features of the data, underlining specific textual passages, and assigning them names, also known as codes, to specify the type of content they represent.

3. Searching for and Reviewing Themes: To do so, researchers carefully curated the codes, discarding those deemed too general or not directly relevant to the research objectives. Then, several codes were grouped into a broader, single theme based on the research’s aim and objectives. The researchers also thoroughly reviewed the themes to ensure that no data had been overlooked, to verify that the data unquestionably supported the identified themes, and to assess potential areas for improvement.

4. Defining and Naming Themes: This step involved precisely defining each identified theme and determining its contribution to the overall comprehension of the data. Each theme was then assigned a concise and clear name.

5. Writing and Discussing the Findings: The final step involved a detailed presentation and discussion of each theme, followed by reinforcing examples drawn directly from the data to support the interpretation.

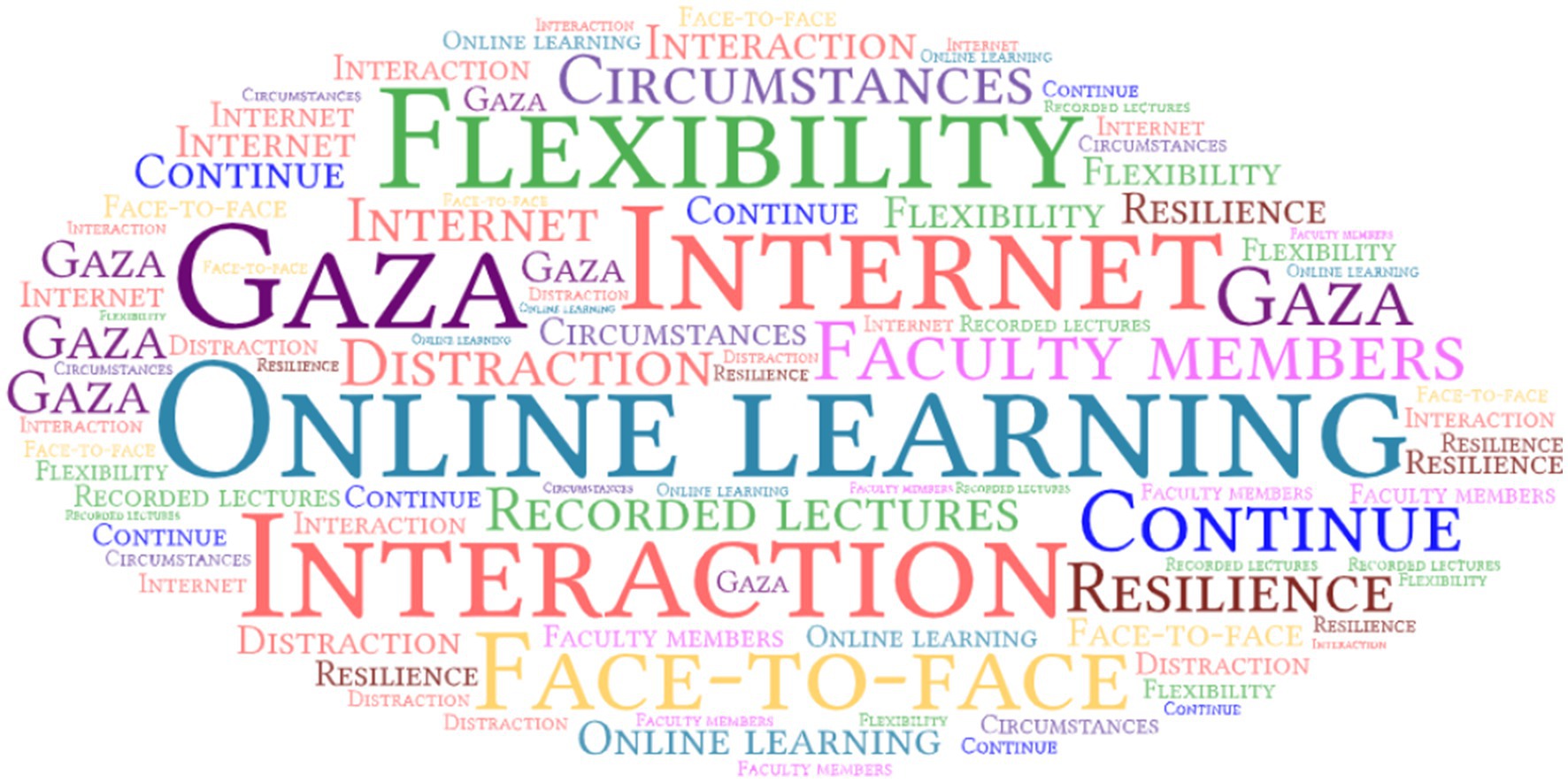

6. Word Cloud Analysis: This technique enabled the identification of the most prominent themes dominating students’ perceptions of the challenges they face in online learning by representing the most frequently used words in a text. Each word’s size indicates its frequency of occurrence in the data, with more frequently appearing terms displayed in larger and bolder fonts.

Through the data analysis process, the authors collaboratively verified all codes and categories during regular meetings, ensuring consistency and precision.

Study results and discussion

The data analysis identified the emergence of the following five main themes about students’ perceptions of online learning.

Study participants’ perception of the challenges of online learning

All interviewed participants strongly asserted that they faced several challenges within the online learning environment. These challenges primarily include the instability or interruption of the internet in the area, infrastructural issues such as inadequate access to laptops, computers, and tablets, frequent power outages or inconsistent power supply, the absence of a safe and stable learning environment, and the continuous need for relocation. All in all, these challenges, along with others, significantly impact the implementation of the online learning pedagogical system.

One student (P2) who participated in the study highlighted the multifarious challenges encountered in the online learning environment, stating: “We face many challenges in online learning, including internet instability, tense situations, bombing, destruction, fear, displacement, unstable life, and lack of security and safety. All of these issues make the process of continuing education through online learning complicated.” This statement highlighted the various unfavorable circumstances, including significant logistical and psychological disruptions, technological instability, and security risks, that collectively hinder the ongoing implementation of online education. This show that during similar crisis, the normal pressures of learning are compounded. Creating a supportive and forgiving environment becomes not just a pedagogical choice, but a psychological necessity to help students cope with both academic and external stressors (Attia and Algazo, 2025).

Another participant (P10) similarly observed: “Right now, we live in challenging circumstances and inappropriate surroundings, making it challenging to find a reliable internet connection and WiFi services. There is also a lack of facilities (laptop, iPad) considered necessary in this type of instruction.” This emphasized the interrelated challenges of inadequate technology infrastructure and the absence of supportive learning environments, both of which seriously hinder the effectiveness of online education.

Another participant (P11) pointed out an important challenge, “The challenge I face through online learning is the absence of engagement as we cannot ask about any difficulty we encounter directly. Thus, I believe online learning cannot be compared to face-to-face learning. In light of the continuing siege and conflict, I also believe that one of our biggest challenges is not having a strong internet connection to watch lectures or download them for later viewing.” This statement stressed a significant concern regarding the limited interaction in online learning environments compared to traditional methods. This issue worsens due to the ongoing problem of unstable internet connectivity, which makes it difficult to access necessary learning resources amid continuous hardship.

(P4) further explained other challenges students face while using online learning: “We lack a suitable and quiet environment for online learning, considering the situation we are going through. Sitting for long periods in front of screens causes severe fatigue and poor concentration, as the safety equipment available to students in other countries may not be available to us.” Along with concerns regarding digital eye strain and unequal access to ergonomic and safety equipment that are widespread in more stable environments, this remark emphasizes the urgent need for a supportive learning environment in the face of ongoing hardship.

Study participants’ perception of the presentation of content and comprehension

While all participating students unanimously agreed that they prefer the face-to-face teaching method over online learning, a significant majority confirmed that they did not face any difficulties understanding the learning content presented online. Additionally, there is unanimity among them that the presentation of learning materials was suitable for their specialization, and they stressed that having a reliable internet connection is crucial.

Regarding this point, one of the participating students (P13) stated, “Although I do not face any problems in understanding the learning content, I still prefer face-to-face learning.” Another participant remarked, “Considering the current circumstances, I believe the information is presented excellently.” These responses indicated that, although students’ comprehension of the content is generally excellent when delivered online, a clear preference for standard in-person education still exists despite challenging operational circumstances.

Another participant (P2) conveyed their perspective on the appropriateness of the learning content, stating: “Yes, the way the material is presented is appropriate under these circumstances, given the challenging conditions in Gaza, the continuous conflict, and the absence of safe environments and universities. Since there is a propensity to use all means necessary to prevent us from continuing our education, it is beneficial for the educational process to continue.” This statement emphasized the importance of maintaining educational continuity while addressing pressing environmental and geopolitical issues and underscores the need for resilience and adaptability in content delivery.

Another participant (7) pointed out: “The learning content presented is organized and easy to understand. Students can easily review and fully comprehend lectures because they can access them anytime.” This demonstrated the perceived advantages of online learning in terms of flexibility and content accessibility, which enable well-structured and understandable learning experiences, allowing students to interact with the material at their convenience for in-depth review and understanding.

Engagement in class

The students participating in the study have different views on this particular point. For example, one student (P8) stated: “Some students might find it challenging to ask questions and receive explanations if no live sessions are available through Zoom or Google Meet. New faculty members may use different teaching methods or platforms, which can confuse students at first.” This observation highlighted concerns about the limited opportunities for face-to-face interaction and potential misunderstandings resulting from the diverse instructional strategies and platforms employed by new faculty members in online settings.

Another participant (P3) mentioned, “We are used to face-to-face classes with direct interaction and participation with the lecturer. However, the volunteer faculty members are doing their best to ensure that the learning content provided is comprehensive.” This statement acknowledged the outstanding efforts of volunteer faculty members in providing thorough learning content under challenging circumstances while also highlighting students’ preference for traditional interactive pedagogy.

His colleague commented (P12), “Although interaction and participation create an enthusiastic and competitive environment, their absence does not significantly affect the quality of online learning.” This indicated that the overall quality of educational content or outcomes from a student’s perspective was not always directly related to interaction and participation, even when they are praised for creating a dynamic learning environment.

Contacting faculty members

Seventy percent of the participants reported that contacting faculty members in the online learning environment were both beneficial and efficient. An example includes the response of the following student (P6), who reported, “When it comes to answering our questions, the volunteer faculty members are prompt and understand our circumstances and conditions. In general, the volunteer faculty members and the old ones do not neglect us in terms of following up and ensuring that everything in the course is clear for us.” Despite the online teaching method, this response demonstrated the consistent support and perceived responsiveness from both established and volunteer teachers, demonstrating successful student-instructor communication.

Another participant’s (P2) response supported this, stating: “I do not have problems contacting faculty members. We have groups and other means of communication, and the teaching staff is in constant contact with us.” This feedback showed the effectiveness of the online learning environment’s communication channels and the consistent accessibility of faculty members across various platforms.

However, one student (P14) who participated in the discussion offered a different perspective. He mentioned, “Sometimes a student may not receive an immediate answer to their questions due to the different schedules or work pressures of various faculty members.” This observation was supported by his colleague’s statement, who added: “Some new instructors may be unclear about how to contact them.” These statements collectively indicated possible communication barriers resulting from asynchronous faculty availability and early confusion about contact procedures with recently hired professors.

Usefulness

By examining the interview data, it became clear that, given the current state of education in Gaza and the inability to conduct face-to-face education, online learning serves as a practical and valuable alternative, offering numerous advantages. A primary benefit frequently cited by participants is enabling them to continue their education.

One student (5) specifically pointed this out, stating, “Despite the challenges we face with online learning, this teaching method ensures that education remains uninterrupted, helping students complete their education.” This highlighted the importance of online learning in maintaining academic achievement and educational continuity in the face of significant setbacks.

Another participant (P11) emphasized the benefits of online learning under the current circumstances: “Online learning is beneficial in light of our circumstances. It offers many advantages, including free access to lectures and content at any time that suits us, helping us balance our studies with our living conditions. It also reduces some costs, such as transportation and printing, easing the financial burden on students.” This statement highlighted the value of online learning in its adaptability, accessibility, and potential to reduce costs, allowing students to balance their academic responsibilities with their challenging living situations.

One student (P14) who participated in the study further noted: “Online learning enhances students’ skills in using technology, such as managing digital platforms, time management, and online communication.” This highlights how online learning is believed to help students develop important digital skills, such as navigating platforms, self-regulating their study schedules, and engaging in successful virtual communication.

The questions were further explored using a word cloud analysis technique. Figure 1 shows the most common words and concepts expressed by students regarding their online learning experience in Gaza after the October 7th events. The more a word appears, the larger and bolder it is shown. According to Figure 1, online learning was the central and most prominent theme, directly reflecting the core subject of the study. Meanwhile, Gaza grounds the entire study in its specific geographical context. The significant size of the challenges, such as internet, interaction, and distraction, shows that difficulties and obstacles were a significant part of the student’s experience with online learning. The substantial use of “face-to-face” indicates a strong resemblance to or longing for a traditional face-to-face learning environment. Students likely used this approach to demonstrate the advantages this method offers, such as direct communication, prompt feedback, and a stable learning environment, in contrast to the drawbacks of online learning. A faculty member’s size indicates their importance to the online learning environment, encompassing content delivery, communication with instructors, and adaptability.

Discussion

Since the start of the conflict in Gaza City, educators have recognized the need to implement and modify online learning to allow students in various fields of study to finish their education, particularly given the extensive destruction of universities and educational facilities. However, in light of the ongoing circumstances, the widespread use of online learning in higher education remains unclear and insufficient. Thus, this study contributes to the existing body of literature by highlighting the perceptions of Gazan students regarding online learning, categorized into five major themes derived from the collected data.

According to the study results, significant challenges hinder the implementation of online learning in higher education, including, but are not limited to, the lack of infrastructure such as laptops and computers, unstable or interrupted internet connectivity, students’ inability to access electronic devices, poor WiFi services, and interrupted electricity supply. These barriers can be attributed mainly to the severe damage sustained by primary infrastructure during the conflict in the area. Such conditions may make it more difficult for students to use online learning, as many are unable to access essential online learning resources, while others must share or borrow them.

Most of the challenges identified in this study align with the findings of other previous studies’. For instance, Dube (2020) notes that students may find it challenging to participate in online learning due to weak internet connectivity and the absence of essential digital resources, such as computers, smartphones, and tablets. Additionally, MacIntyre et al. (2020) stated that the change in students’ level of engagement in class is one of the main challenges that many students face. This particular issue was highlighted by a participant (P4) in the current study, who stated, “One of the biggest challenges we encounter is the absence of direct interaction. In face-to-face learning, students can ask questions directly to faculty members and receive immediate responses. Responses in online learning can be delayed or sent via written messages, which makes the feedback unclear.”

This result can also be explained by the fact that several factors influence students’ perceptions regarding online learning, including the conditions they live in at the time of study, individual motivation level, and available support. Conversely, positive learning environments, which the participating students miss, have been found to increase students’ motivation, engagement, and overall learning capacity. This is confirmed by Tartari and Kashahu (2021), who stated that when students learn online, their level of engagement in class may vary, as well as their emotions and responses.

The study also found that students had positive perceptions regarding the presentation and comprehension of learning content within the online environment. This can be attributed to the fact that faculty members are familiar with online learning, as most have long teaching experience and prior involvement in online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, they are well-equipped to provide the course material via online learning using different digital platforms. It can also be influenced by the faculty members’ contextual understanding of the physical, psychological, and social conditions affecting the student’s learning environment, all of which shape the standards that regulate how the material is presented. Given the circumstances that often prevent many students from connecting to the internet, faculty members seek to present material in a cohesive and integrated way, ensuring students’ comprehension even if they cannot communicate directly to ask questions for clarification. This aligns with Mabed (2021), who confirmed that several factors, primarily the prevailing conditions of the educational environment, significantly impact how learning content is presented online. For example, learning resources can be simplified and shared in lightweight formats (such as compressed PDFs or slide decks) to accommodate unstable electricity and limited devices. Similarly, instead of relying exclusively on lengthy synchronous lectures, instructors can provide short recorded videos, audio messages, or text-based summaries that students may access whenever internet connectivity becomes available. Assessment practices may also be adapted by allowing flexible deadlines or alternative submission methods such as voice notes or short written reflections via WhatsApp.

Regarding engagement in class, no discernible differences were observed in the study sample’s perceptions, with both male and female students confirming that engagement is essential for understanding the learning content, which they often miss in online learning. This was explained in light of a point made by one of the study participants (P11), who said, “Direct interaction is important. Face-to-face learning allows students to ask questions and receive immediate replies and feedback from the professor. In contrast, online learning may result in delayed or written responses that lower explanation clarity and may not accurately deliver the necessary information.” In this regard, Xia et al. (2022) similarly asserted that a lack of engagement with faculty members may not yield the expected results in online learning.

Furthermore, the observed results can be attributed to the fact that faculty members in Gaza notify students that they have uploaded lectures to the platforms after recording and uploading them. This method allows students the flexibility to download the lecture and listen to it at a later time or visit the platform whenever they have free time. This strategy, in turn, limits student direct engagement and participation, often confining interaction to written or recorded questions submitted to faculty members for later responses after listening and watching the recorded lecture.

Moreover, the study sample viewed the degree of contact with faculty members as moderate, with 70% indicating that it was effective and beneficial. This finding can be partially explained by the fact that many of the faculty members teaching students from Gaza are employed by other universities, which may occasionally prevent them from providing students with prompt feedback. Nonetheless, these faculty members try to provide students with thorough instructional materials that address all their queries, thereby mitigating the need for direct contact if connectivity issues arise. One participant (P3) attested to this: “Overall, the online learning process is good. Faculty members, both new and experienced, make every effort to follow up and ensure that we comprehend all of the material covered in the courses.”

Similar to findings reported in previous studies (e.g., Ayimbila et al., 2024), the study participants discussed the potential advantages of online learning and its usefulness. They highlighted the flexible teaching method, which enables faculty members and students to contact each other at any time and from any location. This approach provided students with convenient, on-demand access to lectures and content, making them available for multiple views. Furthermore, participants perceived that online learning reduced cost, saved time, and allowed students to learn at their own pace.

Although it needs some improvement, participating students generally have a positive perception toward online learning, as they believe it offers them the opportunity to keep up with their peers at other universities and continue their education amidst current circumstances. According to one participant (P9), “Students can continue learning through online learning regardless of the conditions that may hinder the face-to-face learning process. It works well, particularly when enhancing content delivery methods and increasing interaction between faculty members and students.”

Considering the significant difficulties facing educational institutions, the study offers valuable insights and implications for adopting online learning in higher education. The study’s findings provide fundamental information necessary to plan and implement a strategic online education system, specifically within the Gaza context. In other words, the results emphasize, provide, and add valuable knowledge about online learning in Gaza for faculty members, staff, policymakers, management of higher education institutions, the Ministry of Education, and other stakeholders who are actively involved in the Gaza education sector, serving as a vital starting point for future initiatives.

The word cloud illustrates how Gazan students are struggling with the practicalities of online learning, including infrastructure, environment, and internet access, while still making an effort to engage with the educational content provided by faculty members, often contrasting it with their preferred face-to-face teaching method.

Conclusion and recommendations

The study’s findings underscore the critical need for online learning systems in contexts where in-person instruction is not feasible. We identified key challenges and opportunities in the adoption of these systems in Gaza, Palestine, including significant infrastructure deficiencies, a perceived lack of engagement, and the absence of a supportive learning environment. However, students had a positive perception of the way content was presented and understood, appreciating the flexibility, anytime access to instructors, and on-demand access to lectures. This study confirms the need to address the challenges that hinder the implementation of online learning, ensuring a successful experience for students that does not negatively affect their education. Furthermore, these findings can serve as a baseline for the comprehensive implementation of an e-learning system at the university.

Understanding the profound impact of online learning on a student’s ability to continue their education is essential for developing effective policies aimed at fostering a better online learning environment. This study provides valuable insights that can guide specialists in optimizing their strategies. Future research should investigate the long-term effects of online learning under conditions similar to those experienced in Gaza, aiming to provide a comprehensive understanding of its sustained benefits and persistent challenges.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because the studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

RaK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. BA: Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. RoK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Correction note

A correction has been made to this article. Details can be found at: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1717017.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abich, Y., and Eriku, G. A. (2023). Challenges and opportunities for the adoption of e-learning at the University of Gondar: A qualitative study. Master card Foundation e-Learning Initiative Working Paper Series 1.0.

Aboagye, E., Yawson, J., and Appiah, K. (2020). COVID-19 and e-learning: the challenges of students in tertiary institutions. Soc. Educ. Res. 2, 1–8. doi: 10.37256/ser.212021422

Almahasees, Z., Mohsen, K., and Amin, M. O. (2021). Faculty’s and students’ perceptions of online learning during COVID-19. Front. Educ. 6:638470. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2021.638470

Al-Shahwan, R. (2024). The attitudes of students at the translation department at Al-Zaytoonah University of Jordan towards using translation from English language into Arabic language by the instructors as a medium of instruction in translation courses. Al-Zaytoonah Universityof Jordan Journal for Human and Social Studies, 5, 176–190. doi: 10.15849/ZJJHSS.240330.09

Alsharif, B., and Khasawneh, R. (2025). The Production of Laterals by Arabic-English Bilingual Children. World J. Engl. Lang. 15, 301–310. doi: 10.5430/wjel.v15n5p301

Alsharif, B., Khasawneh, R., and Alzghoul, M. (2025). Strategies of Rendering Metaphor from Arabic into English: A Comparative Study of ChatGPT and Matecat. World J. Engl. Lang. 16, 45–51. doi: 10.5430/wjel.v16n1p45

Artyukhov, A., Simakhova, A., Artyukhova, N., Bojaruniec, M., and Wit, B. (2023). Information support of e-learning: Ukrainian challenges and cases during the war. J. Mod. Sci. 54, 338–354. doi: 10.13166/jms/176381

Attia, S., and Algazo, M. (2025). Foreign language anxiety in EFL classrooms: teachers’ perceptions, challenges, and strategies for mitigation. Front. Educ. 10:1614353. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1614353

Ayimbila, E., Akantagriwon, D., Awuni, J., and Ayamba, A. (2024). Students' perceptions towards online learning in the upper east region. Eur. J. Educ. Dev. Psychol. 12, 28–49. doi: 10.37745/ejedp.2013/vol12n12849

Clarke, V., and Braun, V. (2013). Teaching thematic analysis: overcoming challenges and developing strategies for effective learning. Psychologist. 26, 120–123. Available at: https://uwe-repository.worktribe.com/index.php/preview/937606/Teaching%20thematic%20analysis%20Research%20Repository%20version.pdf

Dawadi, S. (2020). Thematic analysis approach: a step by step guide for ELT research practitioners. J. NELTA 25, 62–71. doi: 10.3126/nelta.v25i1-2.49731

Dube, B. (2020). Rural online learning in the context of COVID-19 in South Africa: evoking an inclusive education approach. Multidiscip. J. Educ. Res. 10, 135–157. doi: 10.17583/remie.2020.5607

Gillett-Swan, J. (2017). The challenges of online learning: supporting and engaging the isolated learner. J. Learn. Des. 10, 20–30. doi: 10.5204/jld.v9i3.293

Hruzevskyi, O. (2023). A systematic analysis of the impact of the military conflict on the distance education system in Ukraine. E Learn. Innov. J. 1, 71–87. doi: 10.57125/ELIJ.2023.03.25.04

Inan Karagul, B., Seker, M., and Aykut, C. (2021). Investigating students’ digital literacy levels during online education due to COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 13:11878. doi: 10.3390/su132111878

Jamil, F., and Hamre, B. (2018). Teacher reflection in the context of an online professional development course: applying principles of cognitive science to promote teacher learning. Action Teach. Educ. 40, 220–236. doi: 10.1080/01626620.2018.1424051

Kearns, L. R. (2012). Student assessment in online learning: challenges and effective practices. J. Online Learn. Teach. 8:198. Available at: https://jolt.merlot.org/vol8no3/kearns_0912.pdf

Khasawneh, R., and Alsharif, B. (2025). A Comparative Study of AI-powered Tools for Arabic-English and English-Arabic Translation. J. Lang. Teach. Res. 16.

Lei, S. I., and So, A. S. I. (2021). Online teaching and learning experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic–a comparison of teacher and student perceptions. J. Hosp. Tour. Educ. 33, 148–162. doi: 10.1080/10963758.2021.1907196

Mabed, M. (2021). The style of presenting content in e-learning environment and its effect on the attainment of skills of designing and producing eexams for technology and education college students. Fayoum Univ. J. Educ. Psychol. 15, 465–553. doi: 10.21608/JFUST.2021.62306.1280

MacIntyre, P., Gregersen, T., and Mercer, S. (2020). Language teachers' coping strategies during the Covid-19 conversion to online teaching: correlations with stress, wellbeing and negative emotions. System 94, 1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2020.102352

Maphosa, V. (2021). Factors influencing student's perceptions towards e-learning adoption during COVID-19 pandemic: a developing country context. Europ. J. Interact. Multimed. Educ. 2, 1–8. doi: 10.30935/ejimed/11000

Pratiwi, H., and Priyana, J. (2022). Exploring student engagement in online learning. J. Ilmu Pendidik. 28, 66–82. doi: 10.17977/um048v28i2p66-82

Saeedi, M., Khakshour, A., Zarif, B., Abbasi, M., and Imannezhad, S. (2022). Virtual education challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic in academic settings: a systematic review. Med. Educ. Bull. 3, 505–515. doi: 10.22034/MEB.2022.342911.1058

Saputra, E., Saputra, D., Handrianto, C., and Agustinos, P. (2022). EFL students' perception towards online learning: what to consider? IJELTAL 7, 123–140. doi: 10.21093/ijeltal.v7i1.1242

Shuliak, I., Ostapchuk, I., and Laborda, J. (2024). Online education in Ukraine in extreme conditions: constraints and challenges. Comput. Assist. Lang. Learn. Electron. J. 25, 208–227. Available at: https://callej.org/index.php/journal/article/view/101

Song, L., Singleton, E. S., Hill, J. R., and Koh, M. H. (2004). Improving online learning: student perceptions of useful and challenging characteristics. Internet High. Educ. 7, 59–70. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2003.11.003

Tartari, E., and Kashahu, L. (2021). Challenges of students in online learning. Kult. I Eduk. 4, 229–239. doi: 10.15804/kie.2021.04.13

Vitoria, L., Mislinawati, M., and Nurmasyitah, N. (2018). Students' perceptions on the implementation of e-learning: helpful or unhelpful? IOP Conf. Series: Journal of Physics: Conf. Series 1088, 1–7. doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/1088/1/012058

Keywords: online learning, crisis, Gaza, challenges, students’ perception

Citation: Khasawneh R, Alsharif B and Khasawneh R (2025) Online learning amidst crisis: perceptions of Gazan university students. Front. Educ. 10:1659256. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2025.1659256

Edited by:

Matt Smith, University of Wolverhampton, United KingdomReviewed by:

Ivor Timmis, Leeds Beckett University, United KingdomEzekiel Akotuko Ayimbila, C. K. Tedam University of Technology and Applied Sciences, Ghana

Copyright © 2025 Khasawneh, Alsharif and Khasawneh. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Razan Khasawneh, ci5yYXphbmtoYXNhd25laEBnbWFpbC5jb20=

Razan Khasawneh

Razan Khasawneh Bilal Alsharif

Bilal Alsharif Ronza Khasawneh

Ronza Khasawneh