- 1Dunamai Energy, Zomba, Malawi

- 2The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI), New Delhi, India

- 3Centre for Development and the Environment, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

Rice cookers, social media, and television sets are commonly used in rural Nepal. In this paper we explore how gender norms condition the uptake of these artifacts, and the gendered implications of their uses. We draw on material from a household survey, in-depth interviews, focus group discussions, and key informant interviews, collected in 2017 in Dhading and Tanahun districts in rural Nepal. The results show that each of the three artifacts initiate distinct, gendered dynamics in terms of uptake, uses, and effects. Women's use of electric rice cookers aligns with their gendered identity as cooks, helping them improve their gendered work and do not trigger resistance from men. In contrast, the use of mobile phones, social media, and television, prompt complex gender outcomes, resistances, and negotiations. Young people use social media to initiate self-negotiated marriages, shunning arranged marriages thus increasing their agency. It was reported that these self-negotiated marriages tend to be earlier (ages 12–14) than before, as young girls drop out of school to marry their chosen partners, thus threatening their empowerment. Access to television and internet has increased awareness about family planning methods, but persistent gender hierarchies hinder women from freely deciding on and accessing these methods. Women and youth pursuing new opportunities that challenge gender norms are sometimes labeled as unfaithful and unruly by others in the villages. The paper highlights the need to understand subversive responses to social and cultural changes mediated by electricity so that policy and practice can support the desired social transformations.

Introduction

Gender and energy are seen as co-dependent, both being considered key to sustainable development and have been included in the Sustainable Development Goals as goals 5 and 7, respectively. The importance of women's empowerment through energy access is reflected in that “gender” and “women's inclusion” have been key themes of the last three Sustainable Energy for All (SE for All) Annual Forums1. Access to electricity—as part of broader efforts to improve access to modern energy—is being promoted as one of the ways to support women's empowerment and gender equality, as well as sustainable development in general.

However, it is not clear how women may become empowered through electricity access, which is not an end-product, but rather a condition for meaningful uses of various energy services. Moreover, the concept of empowerment is often employed in distinct ways (Winther et al., 2017). In this paper, we ground the analysis of women's empowerment in the concept energy justice: the triumvirate in terms of three basic tenets of justice: distributional (costs/benefits), procedural (process), and recognition (ownership) (McCauley et al., 2013). Energy justice is increasingly used to critique the political economy of energy, and studies anchored in this tradition explicitly address the situation of marginalized stakeholders—e.g., women, social groups, communities—seeking to bring knowledge about such groups to the attention of those “in charge” of the governance of energy systems, whether public or private. We draw from Islar et al. (2017) by focusing on questions of what energy is used for, what values and (moral) principles ought to guide energy decisions as well as who benefits and loses. We take their contribution to the energy justice framework further by looking at these questions from a gender perspective. We primarily focus on the “post-distributive” issues of electricity access, agency and empowerment (Damgaard et al., 2017, p. 14), to explore the interrelation between people's uses of appliances and gender relations in rural Nepal.

The focus on gender and electricity is informed by research and efforts over the last two decades that suggest that provision of modern energy services such as electricity can empower women through several pathways. These pathways include, firstly, distributional aspects of energy justice whereby electricity use has improved women's conditions by reducing work burdens or improving incomes or labor force participation (Dinkelman, 2011; Köhlin et al., 2011; Grogan and Sadanand, 2013; van de Walle et al., 2017; Winther et al., 2017). Secondly, and related to procedural and ownership aspects, women's participation and involvement in decision making regarding electricity supply can improve their incomes and sometimes their standing in the community (Cecelski, 2005; Matly, 2005; Clancy et al., 2007; Standal, 2008; Sovacool et al., 2013; Winther et al., 2018). Conversely, when women are not specifically targeted in supply chains, it is men who tend to be recruited (Winther et al., 2019). Despite these observations and assertions, as argued by Pachauri and Rao (2013) there is still a lack of compelling evidence on the linkages between electricity and women's empowerment. This is particularly true for evidence on how the conditions, positions and relationships of women and men may become re-configured in the processes of obtaining and using electricity at home.

While research is beginning to uncover ways in which electricity may or may not improve development outcomes for women (Kankam and Boon, 2009; Gippner et al., 2012; Winther et al., 2017), there is a gap in the literature regarding how outcomes of electricity are negotiated between women and men, how they impact them, and how existing gender norms affect whether or not women derive benefits including empowerment from electricity services. Whether an electrification programme results into improvements in gender relations is often attributed to technical design of the project; including and training women or providing them with access to finance, whether the system is grid or off-grid (Winther et al., 2017) and/or the degree of gender mainstreaming in national policies (Clancy et al., 2007). Although there are exceptions who have looked at the issue of how outcomes of electricity are negotiated between women and men (Henning, 2000; Winther, 2008, 2012; Matinga, 2010), the focus on gender relations and electricity use, and the gender focus in the energy justice framework are ripe for research.

In this paper, we examine the gendered implications of electricity access among households in rural Nepal, focusing on how the use of electricity affects women's living conditions, positions and power relationships with respect to men. The article draws from empirical evidence from qualitative and quantitative research undertaken in 2017 including fieldwork in rural Nepal, reviews of peer-reviewed literature, government policies, and gray literature. It contributes to the debate on electricity and gender specifically, and more broadly, energy and gender. It also adds gender and energy literature to the literature on energy justice.

The paper is organized as follows: section Energy and Gender in Nepal: Institutions and Norms provides an overview of energy systems and the gender context of Nepal including norms and institutions that condition electricity's uses and impacts in important ways. Section Study Sites and Methods outlines the research design, methodology, and techniques used to collect the evidence presented in the paper. It also presents the context of the two field sites. Section Results presents the findings on household electricity use with respect to their gendered implications. Section Discussion discusses the implications of the findings of the study, while section Conclusion and Recommendations concludes the article and presents recommendations for policy makers and researchers.

Energy and Gender in Nepal: Institutions and Norms

In this section, we discuss electricity and gender in Nepal in order to provide the context in which electricity is introduced and its use embedded. When it comes to prevalence of renewable energy sources, Nepal is one of the most richly endowed countries in South Asia. It has 45.6GW of technically feasible hydropower, and 3GW and 2GW of commercially feasible wind and solar power, respectively (ADB, 2018). Over the years, Nepal has made various efforts to increase the population's access to electricity. In 1996, the government established the Alternative Energy Promotion Center (AEPC), a semi-autonomous government agency under the Ministry of Population and Environment, to promote renewable energy development. The AEPC's aim is to increase access to renewable energy in rural areas through policy formulation, resource mobilization, technical support, monitoring and evaluation, quality assurance, and coordination. AEPC also supports efforts to address gender issues in the Nepalese energy sector and has formulated Gender Equality and Social Inclusion (GESI) guidelines for the energy sector to support the inclusion of women, poor and marginalized groups in the supply and demand side aspects of renewable energy.

In 2003, the government of Nepal established the Community Rural Electrification Programme (CREP) which among other things, provides co-financing to community based-organizations to buy electricity in bulk from the National Electricity Authority (NEA)2, which the latter then sell to communities. The government of Nepal provides subsidies through these agencies to support rural electrification. These efforts combined with efforts from development partners and civil society have helped Nepal improve the access rate to electricity. An estimated 70% of the population now have access to electricity, split as 45% grid access, and 25% off-grid access (Kumar et al., 2015).

While Nepal has made appreciable progress in increasing electricity access to households over the last two decades, electricity's use and benefits are embedded in pre-existing structures, institutions, and norms. These structures, institutions and norms can form what Islar et al. (2017) call feasibility constraints, such that electricity's use and benefits are not equally distributed between various groups. Unequal uses and benefits are most notable between low- and high-income households, rural and urban populations, and between women and men. Among low-income populations, affordability affects firstly, whether they can access electricity or not and when they do have access, whether they can use it for a variety of applications3. Rural areas tend to have poor quality of supply and have higher proportions of persons without electricity access compared to urban areas; 63% of rural dwellers have electricity access compared to 96% of urban dwellers (CBS, 2011). At household level, traditional biomass remains the most commonly used fuel for cooking, heating, and in some cases, lighting (CBS, 2011), and women are largely responsible for providing the biomass as well as for cooking with it. Agro-processes are still largely manual although pumping of water for irrigation is increasingly powered by electricity. While irrigation is largely undertaken by men, grain milling is often women's responsibility and so whether power is directed to irrigation or grain milling affects whether women or men are the key users. There are also pre-existing differences in positions and conditions of women and men that affect their access and use of electricity and other energy sources. While the positions of women and men vary depending on spatial (urban/rural) context, ethnic and caste group, religion, and socio-economic class, overall, women in Nepal have been disadvantaged through both customs and legal provisions compared to men. Factors that have contributed to women's disadvantaged position in Nepal include early and/or child marriages, gender-based violence, wife abandonment, purdah and cchaupadi4, and norms that prioritize and privilege sons over daughters (Care, 2015). Additionally, only about 20% of women have some form of legal ownership rights over land (IOM, 2016), which can affect whether they can subscribe to electricity or not (Winther et al., 2019).

Gender norms have also resulted in women having lower opportunities for education; their literacy rate is 57.4% compared to men's 75.1% (Govt of Nepal, 2016). Women's incomes are on average, 65% lower than men's (World Economic Forum, 2017). Low education levels and social restrictions such as the purdah and perceptions that married women should be stay-at-home mothers and wives, mean women are less likely to be employed than men. In turn, women's lower education and income levels likely negatively affect whether and how women access and use electricity, compared to men. Additionally, the burden of unpaid family care—cooking, cleaning, providing food—disproportionally falls on women. An estimated 75% of unpaid family labor is done by women (CBS, 2009). Meanwhile, the country is experiencing high rates of out-migration primarily by males. At the time of the 2011 Census, an estimated 10% of the population, mostly male, had migrated out of Nepal (CBS, 2011). While such migration brings extra finances to households, it also increases work burdens for women who have to take on men's work burdens over and above their own. Thus, while electricity can bring relief if it eases some of these work burdens, women's ability to use it, for example, for income generation might be limited by time constraints resulting from other work burdens.

Over the years, the Nepali government has put in place legal and regulatory instruments to support women's rights and improve their positions with respect to men. A breakthrough has been the 2015 Constitution of Nepal which, among other things, grants women rights to lineage, right to safe maternity and reproduction, and equal rights in family matters and property (Govt of Nepal, 2015). The Government of Nepal also mandates 33% women's representation in the legislative parliament, and all state machineries. And since 2012, the government provides 30% discount on registration fee when the land is registered under a woman's name (The Women's Foundation, 2018).

Study Sites and Methods

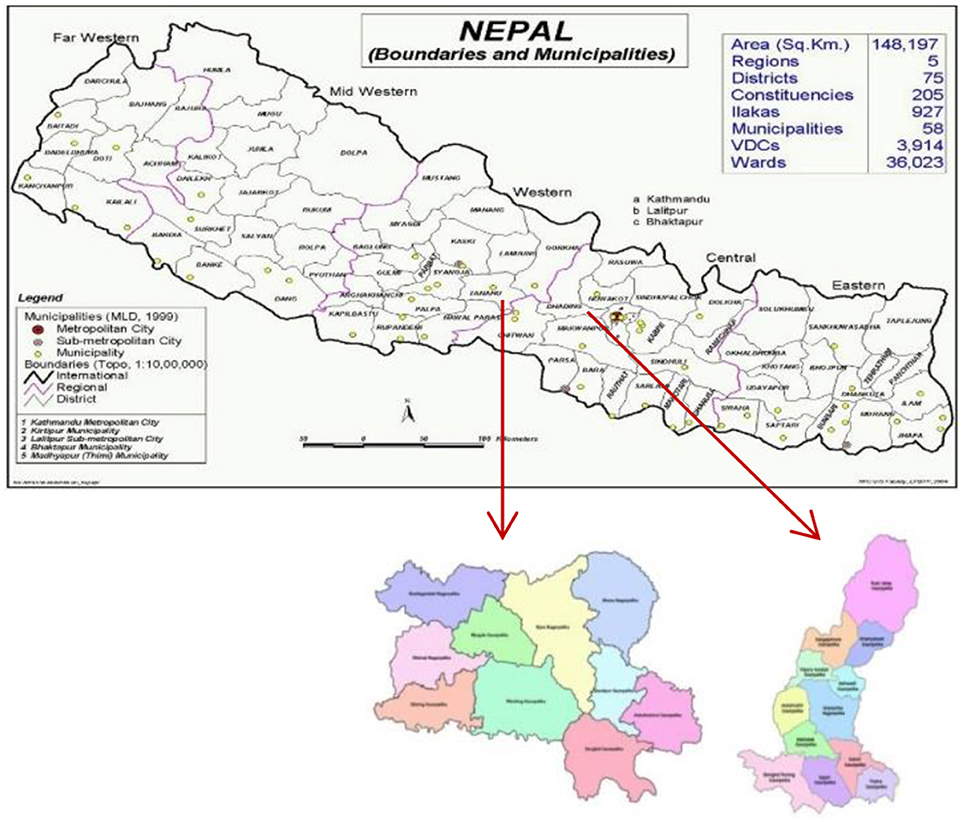

In conducting this research, we started with a literature review on gender and energy, as well as on Nepal. For the qualitative research, fieldwork was conducted in April and October 2017 in two districts; Dhading (Mahadevsthan village development committee, also referred to as Benighat Rorang) and Tanahu (Ghiring and Chapakot wards) districts (see Figure 1).

We selected these sites because they have different types of electricity systems: most households in Mahadevsthan have either grid electricity supplied by NEA or by a 64 kw micro-hydro power plant established with support from AEPC. A small number use solar home systems (SHS), and an even smaller number are without electricity. In Ghiring and Chapakot wards in Tanahu district, households access grid electricity either through a private provider, Butwal Power Company (BPC) or the state utility NEA. In addition to grid electricity, several households in the Ghiring area use SHS initially promoted (15 years ago) through AEPC and private companies.

Brahmin and Chhetri castes were a minority in both sites. Groups indigenous to the Himalayan region, mostly Tamang and Chepang (indigenous Tibeto-Burmans), were the majority but tended to be socio-economically disadvantaged. Non-indigenous community members frequently referred to indigenous communities as backward and unwilling to modernize. As with the rest of Nepal, there is a high rate of migration by male family members in both districts to pursue work and educational opportunities abroad or in the capital (Kathmandu).

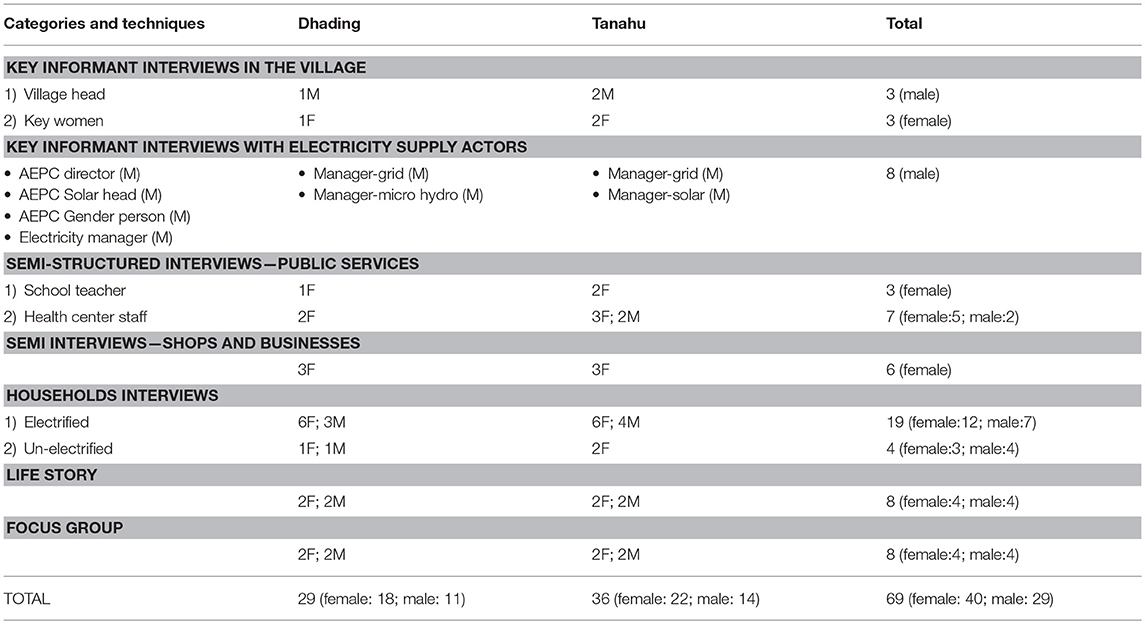

We first used qualitative techniques and then complimented these with quantitative techniques. Qualitative methods allowed us to get an in-depth understanding of electricity and gender as a social phenomenon and allowed respondents to express themselves without constraints of predefined categories. Quantitative techniques allowed us to get a sense of how widespread certain phenomena were among the study population. The qualitative techniques used included semi-structured interviews with women and men representing their households, and key informant interviews with persons we presumed would have deep insights into key issues relevant to our study; teachers and heads of schools provided information on educational performance of girls and boys; clinic personnel provided information on health including family planning; electricity managers provided information on system capacities, tariffs, bill payment etc. We also held focus group discussions with single-sex groups and collected life stories with persons older than 45 years. Table 1 provides a summary of interactions from the qualitative aspect of the research; a total of 61 semi-structured interviews and 8 focus group discussions.

Interviews were conducted in Nepali, with support of a field coordinator and translator from a local research firm. The interviews were recorded, transcribed in English and analyzed by coding using NVIVO as well as manual coding.

In October 2017, we conducted a quantitative survey in Dhading only. This site was chosen purposively based on the qualitative study, while households were sampled systematically with random starting points. The survey sample had 220 respondents with the following electricity access types: 44% were connected to a micro-hydro station through mini-grids, 37% had grid electricity, and 6% had solar home systems (SHS). Seven percent of households had solar lanterns while 6% had no electricity access at all. Data was entered and analyzed using SPSS software.

Results

Appliance Ownership in the Surveyed Homes

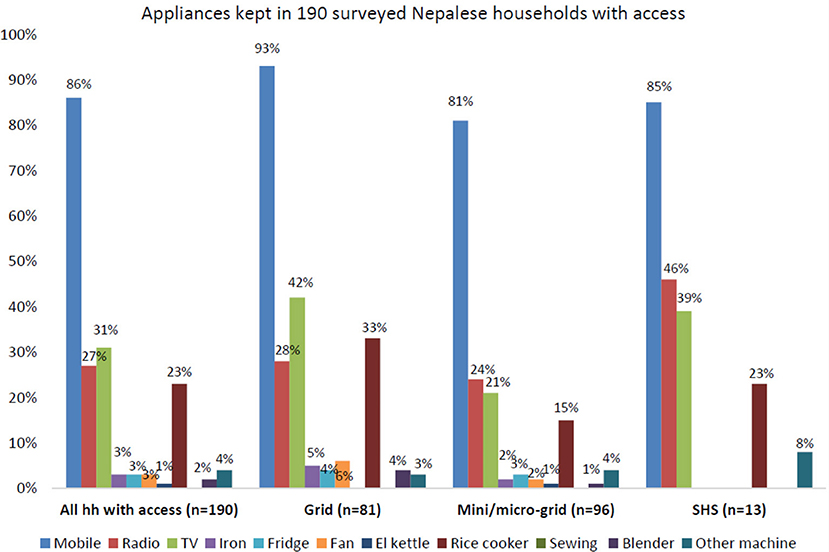

In analyzing the implications of electrification on gender and how it impacts gender relations, we look at the three most available electrical appliances in the research sites; the mobile phone, the television set and the rice cooker. We have excluded lightbulbs which are available in every household with electricity since their use is more communal, and because in many cases, the physical position of lights in the home had been determined by the electricity installer and not household members. Figure 2 shows an overview of the appliances reported as owned in 190 homes with any type of access to electricity that potentially may be used for running appliances (hence excluding households with lanterns only).

Figure 2. Appliances kept in 190 surveyed households with access. HH: Households; SHS: Solar Home Systems.

Based on the reported individual ownership of electric appliances, a gendered pattern becomes apparent from the survey results. More men were said to be sole owners of radios (28.8% men vs. 9.6% women) and color televisions (17.3% men vs. 9.6% women) as compared to women, whereas, more women were sole owners of mobile phones (48% men vs. 57.6% women), rice cookers (1.9% men vs. 15.3% women), and blender-mixers (0% men vs. 3.8% women). In the remaining cases, the spouses were either said to keep the item jointly or that parents/parents-in-laws or “other people” owned the appliance.

Women outnumbering men in mobile phone ownership is a surprising finding given that the Nepal DHS Survey (2016) shows that 89% of men own mobile phones compared to 73% of women. The likely explanation in our study areas is that the high migration rates of productive men have left more younger and older men, which are age groups that tend to have lower mobile phone ownership. Other than this diversion, other results on appliance ownership show that ownership and use of electrical appliances become embedded within pre-existing gender norms: women tend to report higher ownership of appliances linked to their traditional reproductive roles (e.g., food preparation and cooking) while men have higher ownership of all other electrical appliances (e.g., televisions and radios).

Opportunities and Disruptions as a Result of Mobile Phone Use

Mobile phones were used by both men and women. Given the high rates of migration by male family members, mobile phones were said to be critical for remaining in touch and facilitating familial bonds when other family members are abroad or in the capital city (Kathmandu). They facilitate direct remittances as husbands and wives can discuss budgets or household needs, rather than going through in-laws or others. As others have found elsewhere (Schuler et al., 2010; Tenhunen, 2014), mobile phones enable men and especially women to draw support from their networks of friends and relatives. Internet connectivity and access were available in both study sites, and mobiles phones were widely used for video calling, and for social media applications such as Facebook and YouTube. For youth, mobile phones are critical for networking, for watching online videos, and staying in touch with latest trends on a range of issues. Thus, mobile phones are used by and are useful for women, men, youth, elderly and even children. Further, they are common among all households irrespective of their type of access since they do not require high electrical capacities to be charged. For some households, availability of electricity also meant cash savings and increased convenience as they do not have to travel far and/or pay for mobile charging. Meanwhile, community health workers and volunteers said they use mobile phones to communicate with their clients, which they reported, has eased their work of health surveillance. Health workers reported that communication and support is more convenient both for themselves and their clients than before electricity and mobile phones.

Although mobile phones have the benefits cited above, people also perceive them as problematic. Mobile phones have become part of local discourses on sexual infidelity. Men often complained that mobile phones and the use of social media facilitated women's extra-marital affairs. They claimed that since the majority of men migrate abroad and live away from their wives for extended periods of time, women take advantage of this absence and use their mobile phones to connect with other men and have extra-marital affairs. This quote by a male interviewee is illustrative:

Mobile is also creating taboos as people are having love affairs and it is destroying a happy family. Many men who migrated for work returned to find their wives had married other men in their absence.

- Male, Local leader and micro-hydro project initiator, Key person interview, Mahadevsthan

Women also reported that men had affairs and that the practice of polygamy although illegal in Nepal had increased since the arrival of electricity:

Interviewer: Is there any difference in behavior of women and men to each other after the arrival of electricity?

Woman: Practice of polygamy has increased.

Interviewer: What has caused it?

Woman: It may be through TV, mobile, and Facebook. People marry through Facebook too. It may have happened through the phone.

- (Dalit) Female, Vice President of women's savings and credit group, Key person interview, Mahadevsthan

Interestingly, despite evidence of men sometimes leaving their wives to live with other women (effectively second wives5) the men did not report this kind of practice as problematic or as being facilitated by mobile phones and social media. In response to the “problem” of women's extra-marital affairs, men, like the one we quote below, found ways to address the situation:

…. we are empowering women in this topic too. We formed groups to educate them about what relationships truly mean. We have been able to create a good environment and such incidents have reduced drastically over the last 3/4 years.

- Male, Local leader, and micro-hydro project initiator, Key person interview, Mahadevsthan

Men's preoccupation with the moral danger of using mobile phones was directed toward women but not other men. Women on the other hand, seemed less motivated or capable of addressing the problem of men's extra-marital affairs and had not taken collective action as the men had done:

Interviewer: Does it sometimes happen that women or men experience that their rights are limited in practice?

Woman: Yes, in law polygamy is banned. It is heard that if a wife leaves her husband, she should pay 2 lakh rupees. Also, the husband should pay 5 lakh rupees to the wife if he brings another wife. There is a law that the husband cannot hit his wife and drink alcohol too.

Interviewer: Does it happen in the village?

Woman: The laws are limited only to sayings and people are doing such things in the village from long time.

- (Dalit) Female, Vice President of women's savings and credit group, Key person interview, Mahadevsthan

These narratives of mobile phone use and extra marital affairs, and how differently the extra-marital affairs of women and men are perceived and dealt with, show that even as mobile phones improve agency, their use is embedded in unequal gender relationships.

A contested aspect of mobile use that was reported by both women and men relates to the youth. Both women and men claimed that the use of social media allows teenagers to initiate intimate relationships and, in some cases, even elope, while previously parents or other elders would have arranged their marriages. A father told us: “These days we do not need to seek a groom or bride for our children. The mobile is doing this. This is the problem these days.” Another male expressed what he considered some negative effects of this new practice:

Parents, who had aspirations of educating their daughters see them dropping out of school, getting married too early. Such incidents have happened. We have set up a child welfare committee to counsel teenagers, but they are running away at the age of 12 or 13.

- Male, Ward President, Key Person Interview, Mahadevsthan

Women claimed that marriages borne out of elopements tended to occur among the youngest. They reported that girls and boys eloped as young as 12 or 14, while when the marriages were arranged, the age of marriage was commonly between 16 and 18. In one FGD, women complained that such marriages often have a weak foundation resulting in problems and breakdowns. In another FGD, men reported that because parents did not facilitate and, in many cases, authorize these self-negotiated marriages, when the young couples face problems elders do not help them resolve these problems, leading to high rates of such marriage. Some women and men however saw these self-negotiated relationships among adolescents as a positive impact of electrification and mobile phone access because parents or elders did not have to struggle to find partners for their children, a process they considered burdensome. Other women recalled their own negative experiences of not having had any say in the decision of their own marriage partner. They felt that independently choosing a partner was a positive development for young women and men. The survey that followed these FGDs did not however look at how widespread the problem of early marriages was in self-negotiated marriages compared to arranged marriages.

Opportunities and Disruptions as a Result of Watching Television

According to the survey, radios and televisions are, respectively, owned by 27 and 31% of those with electricity access. They are reported as important sources of information and entertainment. The embedding of television in the lives of women is illustrated in that many women (and some men) reported feeling “incomplete” if they had not watched TV on a given day. When asked what type of information they get from listening to the radio and watching television, both women and men said that they get health information and particularly reproductive health. Health workers reported that they have observed improvements in the levels of awareness of health issues such as hygiene and family planning among women. Women, as exemplified below, also reported that when watching television, they get new aspirations regarding what a woman can be:

Sometimes we watch Hindi programmes. And I saw a woman in a white coat explaining things about science. I realized a woman could do that. May be our daughters, because we never had a chance to get education.

- Female participant, Focus Group Discussion, Mahadevsthan

Several women and men said they are learning Hindi through soap operas, which is an privileged language in this area. Due to India's politico-economic relationship with Nepal, speaking Hindi can improve access to work opportunities especially for men, but can also instill a sense of self-esteem especially for women.

As with mobile phones, there are aspects of television use that are, on gender lines, perceived as problematic. Although learning Hindi is seen as an asset in accessing opportunities such as jobs, women have very limited use of their newly acquired skills because social norms require that they stay at home—either in their natal villages or their husbands' home villages, rather than migrate for work or even move out for education6. For men, Hindi is a useful asset when they migrate to India (and in some cases move to Kathmandu) for work because they use it to communicate with their employers or others. Similarly, while television programmes instill new aspirations including ones that counter traditional gender narratives, women often have limited opportunity to realize these new aspirations. One woman talked of watching other women on television in white (laboratory) coats and aspiring the same for her daughters. In reality, girls are often only educated up to School Leaving Certificate (class 12) because for higher education, girls and boys have to relocate to urban areas or abroad. Moving out of the village to pursue education is not considered safe for girls while boys are often accorded the opportunity if the family has funds. Another aspect in which access to television and its benefits are gendered but also problematic is that while women learn more about family planning from television, they are not always free to act on this information and access family planning services. Where a husband and wife disagree, the wives generally defer to the husband's wishes, or must access the services in secret, often at risk of reprimand from their husbands or their relatives, and even violence against them.

Opportunities Brought by Use of Rice Cookers

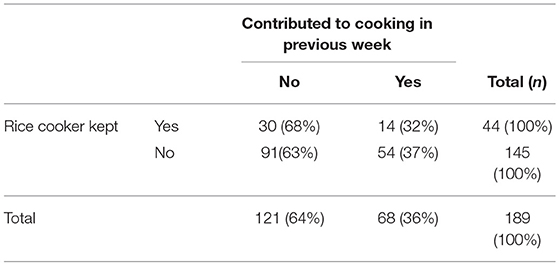

The third most common appliance was rice cookers, which were owned by 23% of the 190 surveyed households with electricity with capacities capable of powering rice cookers i.e., excluding those with solar lanterns only. Women are the primary users of the rice cookers. Both women and men reported that rice cookers (and to a lesser extent, spice grinders) helped women save time, are convenient and reduce drudgery related to cooking as women do not have to tend fires, or clean sooty pots after cooking rice. Respondents reported reduction in cooking time and in drudgery due to reduced need for collecting firewood and/or pinewood cones for cooking. Rice cookers also enable re-organization of work since rice is left to cook and women can focus on other work, as opposed to cooking on open fires where they have to watch and tend the fire and the rice throughout the cooking process. Of the survey sample, 36% reported that men had contributed to cooking in the week before the interviews. While there have not been substantial changes in terms of men engaging more in cooking, rice cookers have facilitated minor changes with men and boys cooking rice and serving themselves. Households with rice cookers were slightly more likely to report that men contribute to cooking (37%) than those without rice cookers (32%) (Table 2). This was also reported during qualitative interviews.

Table 2. Respondents reporting that men contributed to cooking (irrespective of how many times) in the previous week.

During in-depth interviews and FGDs, women were unequivocal in that rice cookers were the most desired electrical appliance, followed by spice grinders. Unlike television and mobile phones, rice cookers did not appear to be problematic and did not invoke any gender-based resistance. While research elsewhere has shown that the transition to using new cooking technology can generate resistance especially among men (Winther, 2008) or feelings of ambivalence among women (Concern Universal, 2012), there was no such evidence in the field sites in Nepal. Men appeared just as appreciative as women of the impacts of rice cookers on their lives, with one man reporting:

I like it a lot. Now I can dish the food for myself whenever I come in. I do not have to wait for my wife or my daughter to come and give me food.

Only one person, a woman, was reported to have resisted the rice cooker.

My mother is the only person in this house who doesn't like it. That is why it has a crack. She was angry and hit it. She thinks rice doesn't taste that nice when we use a rice cooker and that it is probably not good for our health. She just says that so that we can stop using it because she prefers the traditional way.

Discussion

Electricity and its mediating artifacts have brought new opportunities for both women and men albeit not the same opportunities. Within the household realm, across the three artifacts examined in this paper, gendered implications can be demarcated in two: those that imply improved working conditions for women but do not immediately disrupt status quo or gender relations, and those that imply changes in positions and relations of women and men and disrupt gender norms and status quo.

The improvement of conditions of women can be seen in the use of rice cookers which have immediately improved how women do their gendered work of cooking; reducing time spent on this work, reducing drudgery, and reducing smoke in the kitchen. Cooked rice was also available at any time for members to dish for themselves, and men in particular did not have to wait for women to dish rice for them: they could do it themselves. These impacts of rice cookers are in line with findings from Sumba, Indonesia, where rice cookers were reported to decreased effort and time to cook because of reduced need to constantly attend the cooking, reduced firewood collection, that rice was available at any time for family members to dish out and eat, and their use eliminated smoke in the kitchen (World Bank, 2015). Similar benefits were found in Timor Leste (MDF and Matinga, 2018). In Japan where rice cookers made inroads from the 1950s and have become ubiquitous, they are still highly valued by women and had “a revolutionary impact on Japanese women in the 1950s” (Macnaughtan, 2012). Women in Japan—even 60 years later in 2010/11—reported the benefits of rice cookers as convenience, time-saving, and reductions in household work burdens (Macnaughtan, 2012), suggesting that while in the short term they do not appear to disrupt gender hierarchies or challenge gender norms, their benefits are enduring rather than short-term. Indeed, under the appropriate conditions, rice cookers could have a higher potential for changing women's positions as they likely did on Japan where Macnaughtan notes that:

“With rising demand for female labor, especially part-time (pāto), from Japanese companies seeking to maintain a workforce under the conditions of rapid economic growth, these key home appliances added to the ‘supply side’ conditions enabling married women to enter paid employment while still fulfilling their key ‘housewife’ role” (Macnaughtan, 2012 p. 108).

The findings of these study show that in rural Nepal, there is hardly any contestation of the changes that occur as a result of rice cookers. We postulate that this is because currently rice cookers, largely support and enhance traditional gender roles as opposed to directly challenging them. This conclusion is similar to one drawn by Standal and Winther (2016) where lighting in Bamiyan, Afghanistan and Uttar Pradesh, India enabled women to care for children, performing their designated roles as wives, daughters-in-law, and mothers more confidently than before. The difference with this study is that the rice cooker has broader impacts on women's time use which can eventually have more gender transformative impact as seen in Japan. However, Nepal is not yet experiencing sharp demand in female labor as Japan did in the 1950s, and women wanting and able to participate in the labor force would likely have to migrate which could have other social implications. Additionally, other socio-cultural barriers such as the belief that women, especially married women, should not work outside the home would have to decrease to facilitate women's entry into the labor force.

Another important aspect of rice cookers is that they do not seem carry the risk associated with other cooking technologies of changing taste substantially (Winther, 2008; Palit et al., 2013; Wolf et al., 2017). Further, given that one third of men cook irrespective of type of cooking technology (rice cookers or open fires), rice cookers also benefit men who likely have a stake in purchasing them or supporting their use. Thus, men and women in this context, have little incentive to resist the changes they bring about.

The availability of mobile phones has some ambiguous impacts: it helps women and men maintain and strengthen relationships in a context where economically-necessitated migration has separated husbands from wives, and other relatives, enabling frequent communication and direct cash remittances and financial discussions between husbands and wives. To some extent, wives being able to discuss remittances with husbands living abroad has also disrupted the power that male relatives (often brothers-in-law or fathers-in-law) often had because previously they were the ones who were told about and managed the remittances. Mobile phone usage has also created opportunities for women and men to explore new relationships and relationship types (e.g., self-negotiated as opposed to arranged marriages). In the same context, it is blamed for destroying relationships between husband and wives by facilitating extra-marital affairs. And in some cases, is said to destroy an age-old custom of arranged marriages, resulting in less support for young couples and reportedly increased child marriages and break down of marriages of young people.

From a gender and empowerment perspective, the claims that women are engaging in extra-marital affairs when according to respondents, they hardly engaged in these before, represents for better or worse, newly acquired agency for women. Similarly, the advent of self-negotiated marriages among young women and men signal reduced parental control over strategic life choices and improved agency for the youth. The new agency that mobile phones are also illustrated in the evidence from our survey that more women than men own a mobile phone. Thus, for women and youth, for better or worse, mobile phones have challenged and disrupted existing power relations and norms. Due to the said increased in extramarital affairs among women, men through a moral discourse of unruly, immoral women, have developed new ways of policing women or attempt new forms of control of women: teaching them about importance of fidelity in relationships. In contrast, while men's infidelity is also said to have increased, no such policing of men's morality was reported. Men developing new forms of controlling women in the face of increased connectivity via mobile phones is similar to findings by Tacchi et al. (2012). They found that as women strengthened relationships through mobile phone usage, men resisted and attempted new forms of control by limiting visits to women's maternal homes (Tacchi et al., 2012). For young women and men in rural Nepal, mobile phone's effects of disrupting power relations and social norms has invited resistance against the new-found agency from both women and men through moral discourse of unruly youth.

Through access to information afforded by mobile phones and television, women and health workers reported improved awareness of family planning methods. While this arguably facilitate women's reproductive rights—and so enhancing women's capacity to make strategic life decisions and their agency,—men were reported to resist women's access to the available family planning methods. Men required not only a negotiation of whether their wives can access these methods but have ultimate decision-making power when the two disagree. Women sometimes have to negotiate this by secretly accessing family planning methods even though doing so can put them at risk of reprimand from their husbands or relatives, and even violence. The limitations that women face in effecting strategic life choices are especially striking in the context of 2015 Constitution of Nepal, granting women right to safe maternity and reproduction, and equal rights in family matters (Govt of Nepal, 2015), lending credence to one woman's judgement that “The laws are limited only to sayings.” This illustrates how gender norms shape social changes brought about by electricity access and use of electrical appliances.

Television also exposes women to new gender narratives, increasing awareness of the scope of life courses possible for women (e.g., having a non-traditional career), new skills and alternative gender discourses but these have not materialized. What our research shows is that structure barriers and gender norms obstruct women's possibilities of enacting these newly instilled ambitions. Thus, while electricity has opened a gateway to possibilities other barriers in the system—not connected to electrification—continue to limit women's choices.

The study has its limitation which should be considered in referencing the findings to other settings. To begin with, the generalizability of the study is limited due to the methods used. However, given that Nepal is not drastically different from other developing countries in the challenges it faces in electricity access and addressing gender issues, these findings merit being tested in other developing country settings. With respect to mobile phone use, the study could have benefitted from a closer examination of the youth's perspective of phone use in negotiating self-negotiated marriages and whether boys and girls have similar views on this or whether and how their views differ from those of their parents. Additionally, claims that mobile phones and social media tend to facilitate marriage at earlier ages than self-negotiated marriages could have been further investigated as such child marriages could, in the long term have negative impacts on the position of the women. Despite the limitations, the study takes the debate on electricity's impacts on women and men a step further by going beyond current debates on what electricity enables for men and women, to looking more in-depth at some of the gendered post-distributive aspects that have rarely been addressed from an energy justice perspective: how gender, as a relational concept, is shaped through a complex process that includes resistance and negotiations, and expounds on some of these resistances and negotiations. In doing so, the study shows that processes around changes in gender positions and relations are problematic and technology availability and use (for women and men) alone, might not be enough to effect changes in the short term. Thus, all three aspects of energy justice: distributional, procedural, and recognition must be embedded in electrification and energy access programming to improve the changes of addressing gender inequalities. Another vital contribution this research makes is the time factor in impacts of electrification and mediating technologies: since it suggests that technologies might have differing impacts in the short term e.g., simply changing conditions, and in the long term e.g., having gender transformative impacts.

Conclusion and Recommendations

This study has shown that overall, electricity contributes to improvements to women and men's lives. Taking three technologies in rural Nepal; rice cookers, mobile phones, and televisions, the study shows that from a gender perspective, electricity access does lead to improvements in the lives of women for those that access and use these technologies. However, there are subtle but important resistances and negotiations that occur around some of the changes. For this particular context, resistance was found where technologies directly threatened positions and relations, as illustrated by discourses of women's infidelity and men organizing to instruct women about morality, as well as concerns over self-negotiated marriages.

Another key finding of this research in terms of electricity and gender impacts is how rice cookers immediately improve women's conditions and are highly desired by the women. Also, that among households with rice cookers, men were slightly more likely to cook than in households without. The women and men's high regard for rice cookers runs counter to most narratives in gender and energy work which place little value on electricity compared to improved biomass cookstoves because “electricity is not used for cooking.” This context, and others such as Indonesia show that electricity is used for cooking along with rice cookers and is valued by women. Annecke (2005), IEG (2008), Matinga (2010), Dinkelman (2011), and World Bank (2015) have all found that in specific context, electricity is used for cooking, and although it does not replace firewood in full and is used by a small population, it is does improve the welfare of women.

Where mobile phones open up spaces of power e.g., enable strategic choices such as choosing partners, concerns arise especially among men due to the disruptions to hierarchy that the mobile phones facilitate. Similarly, inasmuch as television open up information for strategic life decisions such as family planning or different life courses (such as careers) for women, it is often difficult to appropriate these because women continue to have limited agentic ability and power, and because other sectors also have gaps in how they provide services for women.

We now turn to some recommendations for policy makers and practitioners, and for researchers. First, for policy makers and practitioners including gender advocates and development partners, it is important that in designing, implementing, or evaluating electrification projects impacts on women and men should clearly be defined and addressed. They must distinguish impacts that improve conditions of women and men, and those that disrupt gender relations and social norms, without necessarily putting more value on one or another since they serve different purposes. Secondly, electricity should not be discounted as not beneficial for women because they do not cook with electricity. The impacts from television, mobile phones, and in specific context for cooking e.g., using rice cookers, are critical to women who find them highly valuable, and this should guide how support is provided. Moreover, achieving gender equality also means seeing female energy users not just in their traditional roles of cooks. Thirdly, electricity does not function in a vacuum and cannot be sorely responsible for improving gendered conditions or gender relations. It is important to recognize and provide the ancillary services needed such as higher education services, in a gender responsive manner, to enhance benefits of electrification especially for women. This will require cross-sector work. Finally, we urge policy makers and practitioners to be sensitive to the time factor in gendered impacts of electrification: what might seem to have minimal impact in the first few years after electrification might have more transformative impacts over several years and depending on other changing contextual conditions. This means that indicators for measuring gender outcomes and impacts might have to change over time: ownership of a rice cooker might be an indicator for improving welfare for women at its start but as economic and cultural conditions change it might enable women to enter paid labor market making the same rice cooker an indicator for economic life choices. For those that fund research and for researchers, the time factor means conducting longitudinal research to better understand how the gendered impacts of electrification change over time.

For researchers, so far gender and energy research has focused on what changes electricity brings and present these as unproblematic. This research shows that, in rural Nepal, when electricity's benefits threaten gender hierarchies, resistance and negotiations are part of the process of change that accompanies electrification and need to be better understood for the appropriate support to be provided. Further, much of the gender and energy research examines gender changes in terms of what women and men have because of electrification. This research shows the importance of separating these changes, as changes in conditions, positions, and to relations. Changes in conditions are critical especially to women's and household's welfare though they do little to challenge and close gender gaps, at least not without other facilitative factors. This is not to mean technologies or efforts that only change conditions are inferior to those that change women's positions and relations with respect to men. Rather, they must be acknowledged as such. They might indeed be stepping stones to changing positions and relations when conditions are right e.g., high demand of work force to push women into paid labor participation as happened with rice cookers in Japan.

This research suggests that changes to positions and relations are likely to be resisted, and so availability of technology only—electricity, mobile phones, or television—may be inadequate in embedding changes to gender relations. The resistance to impacts that threaten to change positions and relations shows the importance of working with a relational rather than just conditional view of gender. Our research shows that rice cookers are impacting women's lives in a variety of settings where rice is a key part of the diet and some research data is available such as in Asia—but could also be critical in West Africa. Yet this is an under-researched area and hence there is little for policy makers and practitioners to go on when designing projects. This represents a research gap for an area that could have critical impacts for women's lives, and researchers need to start addressing it. This research also begins to contribute to the literature on energy justice which though looking at marginalized groups, has hardly looked gender in electrification.

Author Contributions

MM developed paper concept based on research undertaken by the EFEWEE consortium (www.efewee.org). She helped with in conceptualizing the research design, undertook fieldwork in Mahadevsthan (Dhading) and contributed to writing and analysis. BG undertook fieldwork in Mahadevsthan and Ghiring and Chapakot (Tanahu) and contributed to the analysis and writing. TW led the planning of the empirical research and contributed to the analysis and the writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This independent research derives from the project Exploring Factors that Enhance and restrict Women's Empowerment through Electrification (EFEWEE) funded by the Department for International Development (DFID), UK, and coordinated by the International Network on Gender and Sustainable Energy (ENERGIA) through the Energy and Gender Research Programme (2015–2018).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the women and men in the research sites, that answered our questions and supported us in many ways, making this research possible. We also thank the TAG team members and the Secretariat of the research programme whose guidance and probing questions pushed us to undertake meaningful analysis: Andrew Barnett, Mumbi Machera, Youba Sokona, Elizabeth Cecelski, Joy Clancy, Annemarije Kooijman-van Dijk, and others. Colleagues of in this research consortium also rendered various types of support and we are grateful for this.

Finally, we are grateful to the editor and two reviewers for their valuable comments.

Footnotes

1. ^Sustainable Energy for All (SE4All) is an initiative launched by the UN Secretary General in September 2011, with the aim of achieving three goals by 2030: Ensuring universal access to modern energy services; doubling the global rate of improvements in energy efficiency; and doubling the share of renewable energy in the global energy mix. Each year since 2014, the initiative has held an annual forum to broker partnerships, share experiences, and drum up investment for these goals.

2. ^Nepal Electricity Authority (NEA) is the national utility, generating and distributing electric power under the supervision of the Government of Nepal.

3. ^Among the top most quintile, 94% have access to electricity while the bottom quintile only 42% have electricity access (CBS, 2011).

4. ^Purdah is the physical and social limitation of interaction between women and males according to specific rules of association common in South Asia especially among Muslims and Hindus. Chhaupadi is a social tradition associated with the menstrual taboo in the western regions of Nepal, that prohibits Hindu women from participating in normal family activities while menstruating, as they are considered “impure.”

5. ^It is common in both areas for a husband to move out of his marital home and live with new wife while his first wife continues to live in their marital home. The husband would either start living in two homes or completely abandon the first wife. Official separation and divorce are not common.

6. ^There is however an increasing number of women migrating for work, but often within Nepal. According to the Demographic and Health Survey, of 8,836 persons that migrated in the past 10 years (from 2016), 57% were men and 43% were women. Eighty four percent of women migrated within Nepal, while the 68% of men migrated abroad.

References

ADB (2018). Gender Equality and Social Inclusion Assessment of the Energy Sector: Enhancing Social Sustainability of Energy Development in Nepal. Manila: Asian Development Bank.

Annecke, W. J. (2005). Whose Turn is it to Cook Tonight? Changing Gender Relations in a South African Township. Report of the Collaborative Research Group on Gender and Energy(CRGGE), the ENERGIA International Network on Gender and Sustainable Energy and the Department for International Development (DFID).

Care (2015). Gender Relations in Nepal - Overview. CareInternational. Avaliable online at: http://drupal-157272-453315.cloudwaysapps.com/sites/default/files/RGA%20Overview%20Nepal_Final.pdf (Accessed June 25, 2018)

CBS (2009). Report on the Nepal Labour Force Survey 2008. Kathmandu: Central Bureau of Statistics. Avaliable online at: http://cbs.gov.np/image/data/Surveys/2015/NLFS-2008%20Report.pdf

CBS (2011). Nepal Living Standards Survey 2010/11 1st Edn., Vol. 1. Kathmandu: Central Bureau of Statistics. Avaliable online at: file:///C:/Users/bigsna.gill/Downloads/Statistical_Report_Vol1.pdf

Cecelski, E. (2005). Energy, Development and Gender: Global Correlations and Causality. Leusden: ENERGIA.

Clancy, J., Ummar, F., Shakya, I., and Kelkar, G. (2007). Appropriate gender-analysis tools for unpacking the gender-energy-poverty nexus. Gend. Dev. 15, 241–257. doi: 10.1080/13552070701391102

Concern Universal (2012). Socio-Cultural Acceptability of Improved Cook Stoves (ICS) in Rural Malawi. Lilongwe: Concern Universaland Irish Aid. Authored by M.N. Matinga.

Damgaard, C., McCauley, D., and Long, J. (2017). Assessing the energy justice implications of bioenergy development in Nepal. Energy Sustain. Soc. 7:1–16. doi: 10.1186/s13705-017-0111-6

Dinkelman, T. (2011). The effects of rural electrification on employment: new evidence from South Africa. Am. Econ. Rev. 101, 3078–3108. doi: 10.1257/aer.101.7.3078

Gippner, O., Saroj, D., and Sovacool, B. (2012). Microhydro electrification and climate change adaptation in Nepal: Socioeconomic lessons from the Rural Energy Development Program (REDP). Mitigat. Adapt. Strat. Global Change 18, 407–427. doi: 10.1007/s11027-012-9367-5

Govt of Nepal (2015). The Constitution of Nepal. Kathmandu: Govt of Nepal. Avaliable online at: http://www.wipo.int/edocs/lexdocs/laws/en/np/np029en.pdf

Govt of Nepal (2016). Ministry of Population and Environment. Renewable Energy Subsidy Policy. Kathmandu.

Grogan, L., and Sadanand, A. (2013). Rural electrification and employment in poor countries: evidence from Nicaragua. World Dev. Elsevier 43, 252–265. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2012.09.002

Henning, A. (2000). Ambiguous Artefacts: Solar Collectors in Swedish Contexts. On Processes of Cultural Modification. Stockholm: Stockholm University. Avaliable online at: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:523329/FULLTEXT01.pdf

IEG (2008). ‘The Welfare Impact of Rural Electrification: A Reassessment of the Costs and Benefits. An IEGImpact Evaluation.’ (Authored by H. White et al.). Washington D.C.: The World Bank Independent Evaluation Group.

IOM (2016). Barriers to women's land and property access and ownership in Nepal. Kathmandu: International Organization for Migration.Avaliable online at: https://www.iom.int/sites/default/files/our_work/DOE/LPR/Barriers-to-Womens-Land-Property-Access-Ownership-in-Nepal.pdf (Accessed June 25, 2018)

Islar, M., Brogaard, S., and Lemberg-Pedersen, M. (2017). Feasibility of energy justice: exploring national and local efforts for energy development in Nepal. Energy Policy 105, 668–676. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2017.03.004

Kankam, S., and Boon, E. K. (2009). Energy delivery and utilization for rural development: Lessons from Northern Ghana. Energy Sust. Dev. 13, 212–218. doi: 10.1016/j.esd.2009.08.002

Köhlin, G., Sills, E., Pattanayak, S., and Wilfong, C. (2011). Energy, Gender and Development: What Are the Linkages? Where is the Evidence? Washington, DC: The World Bank. doi: 10.1596/1813-9450-5800

Kumar, P., Yamashita, T., Karki, A., Rajshekar, S., Shrestha, A., and Yadav, A. (2015). Nepal - Scaling Up Electricity Access Through Mini and Micro Hydropower Applications: A Strategic Stock-Taking and Developing a Future Roadmap (Vol. 2): Summary (English). Washington, DC: World Bank Group. Avaliable online at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/527221467993505663/Summary

Macnaughtan, H. (2012). “Building up steam as consumers: women, rice cookers and the consumption of everyday household goods in Japan,” in The Historical Consumer: Consumption and Everyday Life in Japan, eds P. Francks and J. Hunter (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan), 1850–2000.

Matinga, M. N. (2010). We Grow Up With It: An Ethnographic Study of the Experiences, Perceptions and Responses to the Health Impacts of Energy Acquisition and Use in Rural South Africa. Enschede: University of Twente.

Matly, M. (2005). “Women's Electrification Report of the Collaborative Research Group on Gender and Energy (CRGGE),” in The ENERGIA International Network on Gender and Sustainable Energy and the Department for International Development (DFID) (London: Department for International Development (DFID))

McCauley, D. A., Heffron, R. J., Stephan, H., and Jenkins, K. (2013). Advancing energy justice: the triumvirate of tenets. Int. Energy Law Review 32, 107–116.

MDF, and Matinga, M. N. (2018). Assessment on Impact of Improved Cook-stoves at the Household Level in Timor-Leste. Report for MDF, Dili, Timor Leste, Unpublished report.

Pachauri, S., and Rao, N. D. (2013). Gender impacts and determinants of energy poverty: are we asking the right questions? Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 5, 205–215. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2013.04.006

Palit, D., Sovacool, B. K., Cooper, C., Zoppo, D., Eidsness, J., Crafton, M., et al. (2013).The trials and tribulations of the Village Energy Security Programme (VESP) in India. Energy Policy 57, 407–413 doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2013.02.006

Schuler, S. R., Islam, F., and Rottach, E. (2010). Women's empowerment revisited: a case study from Bangladesh. Dev. Pract. 20, 840–854. doi: 10.1080/09614524.2010.508108

Sovacool, B. K., Clarke, S., Johnson, K., and Crafton, M. (2013). Energy-enterprise-gender nexus: lessons from the Multifunctional Platform (MFP) in Mali. Renew. Energy 50, 115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2012.06.024

Standal, K. (2008). Giving Light and Hope in Rural Afghanistan: the Impact of Norwegian Church Aid's Barefoot Approach on Women Beneficiaries. Oslo: University of Oslo.

Standal, K., and Winther, T. (2016). Empowerment through Energy? Impact of electricity on care work practices and gender relations. Forum Dev. Studies 43, 27–45. doi: 10.1080/08039410.2015.1134642

Tacchi, J., Kitner, K. R., and Crawford, K. (2012). Meaningful mobility: gender, development and mobile phones. Feminist Media Stud. 12, 528–537. doi: 10.1080/14680777.2012.741869

Tenhunen, S. (2014). “Gender, Intersectionality and Smartphones in Rural West Bengal,” in Women, Gender and Everyday Social Transformation in India, eds K. B. Nielsen and A. Waldrop (London: Anthem Press), 23–46.

The Women's Foundation (2018). Property Rights. Retrieved from The Women's Foundation. Avaliable online at: https://www.womenepal.org/womens-and-childrens-issues/property-rights/

van de Walle, D., Ravallion, M., Mendiratta, V., and Koolwal, G. (2017). Long-term gains from electrification in rural India. World Bank Econ. Rev. 31, 385–411. doi: 10.1093/wber/lhv057

Winther, T. (2008). The Impact of Electricity: Development, Desires and Dilemmas. Oxford: Berghann Books.

Winther, T. (2012). “Negotiating energy and gender: ethnographic illustrations from Zanzibar and Sweden,” in Development and Environment: Practices, Theories, Policies, eds K. Nielsen and K. Bjørkdahl (Oslo: Akademisk Forlag), 191–207.

Winther, T., Matinga, M., Saini, A., Ulsrud, K., Govindan, M., Gill, B., et al. (2019). Women's Empowerment and Electricity Access: How do Grid and Off-grid Systems enhance or restrict gender equality? Research Report RA1, University of Oslo, The Energy Resources Institute, Dunamai Energy and Seacrester Consulting. ENERGIA International Network on Gender & Sustainable Energy.

Winther, T., Matinga, M., Ulsrud, K., and Standal, K. (2017). Women's empowerment through electricity access: scoping study and proposal for a framework of analysis. J. Dev. Effect. 9, 389–417. doi: 10.1080/19439342.2017.1343368

Winther, T., Ulsrud, K., and Saini, A. (2018). Solar powered electricity access: Implications for women's empowerment in rural Kenya. Energy Res. Social Sci. 44, 61–74. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2018.04.017

Wolf, J., Mäusezahl, D., Verastegui, H., and Hartinger, S. M. (2017). Adoption of clean cookstoves after improved solid fuel stove programme exposure: a cross-sectional study in three peruvian andean regions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14:745. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14070745

World Bank (2015). Stoves, Fuels, and Cooking Practices on Sumba Island, Indonesia: Findings and Recommendations of Qualitative Field Research. EAP Gender and Energy Facility and CSI (Clean Stove Initiative). Washington, DC: GPSURR; World Bank.

World Economic Forum (2017). The Global Gender Gap Report. Geneva: World Economic Forum. Avaliable online at: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2017.pdf (Accessed June 25, 2018)

Keywords: gender relations, energy poverty, electricity access, women's empowerment, energy justice

Citation: Matinga MN, Gill B and Winther T (2019) Rice Cookers, Social Media, and Unruly Women: Disentangling Electricity's Gendered Implications in Rural Nepal. Front. Energy Res. 6:140. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2018.00140

Received: 28 July 2018; Accepted: 03 December 2018;

Published: 24 January 2019.

Edited by:

Ethemcan Turhan, Royal Institute of Technology, SwedenReviewed by:

Cornelia Fraune, Darmstadt University of Technology, GermanyKevin Lo, Hong Kong Baptist University, Hong Kong

Copyright © 2019 Matinga, Gill and Winther. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Margaret N. Matinga, bW1hdF8wMDFAeWFob28uY29t

Margaret N. Matinga

Margaret N. Matinga Bigsna Gill

Bigsna Gill Tanja Winther

Tanja Winther