- 1School of Energy and Environment, Southeast University, Nanjing, China

- 2John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences Harvard University Cambridge, Cambridge, MA, United States

Introduction

Flexible electronics may lead to a novel technological revolution with the upcoming 5G information era (Wang et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2021). However, the traditional power supply with batteries cannot match the needs of flexible electronics. Hence, an advanced power source with flexibility, non-environmental dependency, and user-friendliness is urgently needed (Suarez et al., 2017; Fan et al., 2021). Immense but largely untapped low-grade heat from the human body, industry (e.g., data centers), and the environment (e.g., solar energy) is emerging into the research spotlight (Duan et al., 2021). Thermoelectric energy conversion technology is an approach for reusing the widely available low-grade heat, which has the potential to optimize energy efficiency and reduce energy consumption (Fan et al., 2021). Among the state-of-art options, thermogalvanic cells can generate electricity by the gain and loss of electrons at the two same electrodes under the action of a temperature-dependent redox ionic reaction (Lei et al., 2021; Li et al., 2021). In comparison with the conventional electronic thermoelectrics (Taroni et al., 2018; Chae et al., 2020) and ionic thermos capacitors (Al-zubaidi et al., 2017; Wu et al., 2021), thermogalvanic cells based on redox reactions are not only noise-free and environmentally friendly, but also they enable continuous conversion of low-grade heat to electricity (Gao et al., 2022). Moreover, the thermogalvanic cells hold the potential to enable an efficient, lightweight, continuous flexible power supply for the burgeoning flexible electronics (e.g., flexible screens and wearable medical electronics) (Liu et al., 2022; Peng et al., 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). This imposes the challenge of durably optimizing the performance of thermogalvanic cells in terms of thermopower (Duan et al., 2018), mechanical properties (Lei et al., 2021; Gao et al., 2022; Lei et al., 2022), and anti-freezing (Gao et al., 2021), among others. Although the previous researchers presented significant advances, thermogalvanic cells still have challenges in the field of low-grade heat harvesting and flexible power sources.

This article intends to summarize the potentials of the thermogalvanic cells from the working mechanism, and strategies for performance enhancement. In the end, the challenges of thermogalvanic cells in further applications are also comprehensively presented.

The Working Mechanism of Thermogalvanic Cells

The thermogalvanic cell is assembled by two identical electrodes and an electrolyte with a redox couple. The liquid-state electrolyte mainly comprises an organic ionic liquid or salt solution containing redox couples, such as Fe2+/Fe3+, I−/I3−, and Fe(CN)63-/Fe(CN)64−. The quasi-solid electrolyte includes gel matrix (gelatin, PVA, PAAM, etc.) and the doped redox couples mentioned previously. There are two main approaches for obtaining the quasi-solid electrolyte: (1) first, doping the redox couple into precursor solution and then gelling the solution and (2) first, obtaining the gel matrix and then immersing the redox couple. Once the two electrodes are given a temperature gradient, thermopower can be generated by the temperature-dependent redox reaction,

where

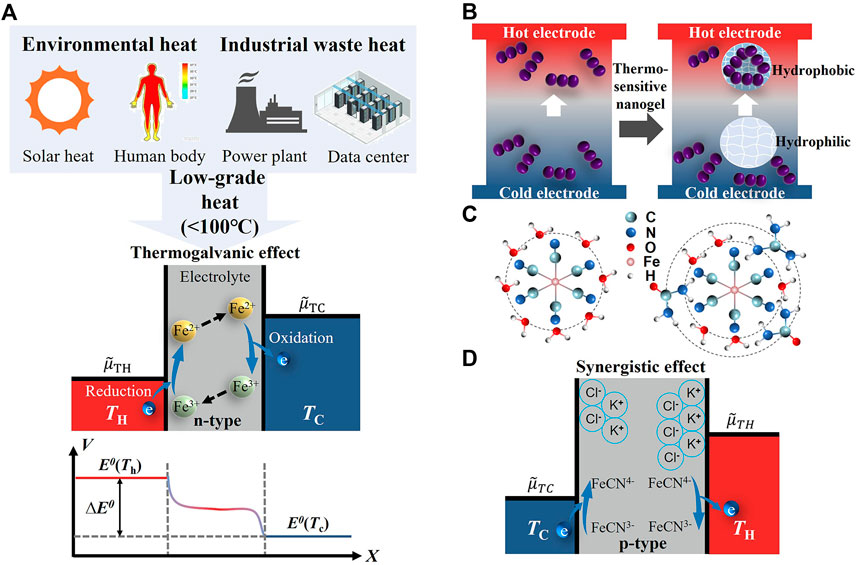

As shown in the mechanism diagram of Figure 1A, for the thermogalvanic cell with the redox couple, ferric/ferrous (Fe3+/Fe2+), the thermopower is zero without a temperature gradient. The redox couple (Fe2+/Fe3+) doped in the electrolyte of quasi-solid thermocell based on the thermogalvanic effect undergoes spontaneous redox reactions when heat flows across the cell. At the hot electrode, Fe3+ gains electrons from the electrode and is reduced to Fe2+, which leads to an increase in the standard potential

FIGURE 1. Mechanism and strategies for performance enhancement of thermogalvanic cells. (A) Low-grade heat sources and mechanism of thermoelectric energy conversion via thermogalvanic cells (Fe2+/Fe3+, n-type). (B) Strategy of enhancing concentration ratio differences. (C) Strategy of reorganizing the solvated shell of the redox couple. (D) Synergistic effect of thermodiffusion and thermogalvanic effects (Fe(CN)63−/Fe(CN)64−, p-type).

Performance Enhancement of Thermogalvanic Cells

For thermogalvanic cells, redox couples with different entropy differences can output a certain thermopower under a temperature gradient. Therefore, liquid thermogalvanic cells with different thermoelectric performances can be fabricated with electrolytes of organic solvents or aqueous solutions (Fe(CN)64−/3−, Fe2+/3+, and I−/3−). For example, the thermopower of thermogalvanic cells using ferricyanide/ferrocyanide (Fe(CN)64−/3−) and ferric/ferrous (Fe3+/2+) electrolyte solution as electrolytes is ∼1.4 mV/K and ∼1.0 mV/K. In order to enhance thermoelectric performance, two strategies have been reported in thermogalvanic cell systems through two distinct mechanisms (Duan et al., 2021). One strategy is to increase the solvation structure entropy difference. Jiao et al. (2014) reported thermopower up to ∼2.65 mV/K using pure ionic liquids or ionic liquid mixture electrolytes, which is mainly attributed to the different solution environments between ionic liquids and aqueous systems. Moreover, the introduction of ionic liquids and the addition of organic solvents with appropriate solubility can also contribute to thermoelectric performances. The combination of 15 wt% methanol and Fe(CN)64−/3− exhibits a thermopower of ∼2.9 mV/K (Kim et al., 2017). Duan et al. (2018) tripled the thermopower to 4.2 mV/K by adding Gdm+ and urea, reorganizing the solvated shell of Fe(CN)64−/3− based on the chaotrope–chaotrope ionic bond interaction (Figure 1B). In addition to the approach of increasing the redox entropy difference, enhancing concentration ratio differences between redox species is another strategy. It has been reported that the introduction of thermosensitive nanogel (poly(N-isopropylacrylamide), PNIPAM) (Duan et al., 2019) (Figure 1C) and supramolecular (α-cyclodextrin) (Zhou et al., 2016) can boost the thermopower by establishing a lager redox species concentration difference across the cell.

Although the ionic mobility of liquid-state thermocells is more prominent, the leakage risk of electrolyte solutions poses challenges for thermogalvanic cell packaging (Gao et al., 2021). To this end, quasi-solid-state thermogalvanic cells (e.g., hydrogel with redox couples) emerge due to the decoupling of mechanical and ionic properties of solid and liquid, respectively. Wu et al. (2017) and Yang et al. (2016) fabricated the quasi-solid thermocell based on Fe(CN)64−/3− (p-type), using poly(sodium acrylate) and PVA, which obtained the different thermopower of −1.09 and −1.21 mV/K, respectively. These values exhibit a slight decrease compared to the equivalent condition in an aqueous solution, attributed to the poor ion transport in the gel matrix. On the contrary, Zhou et al. (2018) introduced the polymer–ion interaction between I3− and the polymer containing starch and polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), achieving the enhancement of +0.86 mV/K in liquid I−/ I3− solution to +1.54 mV/K. In addition, Taheri et al. (2018) further studied the relationship between PVDF, PVD-HFP, and cobalt bipyridyl redox. Results show that only strongly interconnected polymer chains and redox reactants affect entropy changes of the redox reaction. Otherwise, the change of thermopower is negligible. However, the maximum power densities obtained with PVDF (6 mW/m2) and PVDF-HFP (4.5 mW/m2) are significantly reduced compared to liquid MPN-based electrolyte (48 mW/m2), which is mainly due to the limited convection that impairs the mass transport. Zhou and Liu, (2018) achieved a high thermopower as high as −9.9 mV/K first through the combination of acetone and isopropanol. This report demonstrates the evaporation phase transition of acetone on the boost of entropy and the enhancement of the concentration gradient, which verifies the possibility of enhancing the thermoelectric performance through the vapor–liquid phase transition. Based on the gelatin containing KCl, NaCl, KNO3, and Fe(CN)64−/3−, Cheng-Gong et al. (2020) gained a prominent thermopower of +17 mV/K through the thermodiffusion of KCl, NaCl, and KNO3, as well as the thermogalvanic effect of Fe(CN)64−/3− (Figure 1D). In addition to the studies on the enhancement of thermoelectric performance, the anti-freeze performance (Gao et al., 2021), mechanical properties (Gao et al., 2022), and p-n-type conversion (Duan et al., 2019) are also the focus of research.

In addition, electrode materials are also critical to realizing the thermoelectric performance enhancement. Compared with the commonly used metal electrodes, carbon-based electrodes and conducting polymer electrodes have high-efficiency and flexibility advantages. The Carnot efficiency of the thermogalvanic cells with multi-walled CNTs is 200% superior to that of platinum (Hu et al., 2010). By adjusting the composition of the CNTs and GO composites, an output power of 460 mW/m2 and a Carnot efficiency of 2.6% were obtained (Romano et al., 2013). Moreover, the PEDOT-Tos conductive polymer electrodes also demonstrated comparable electrical properties to platinum (Wijeratne et al., 2017). Benefiting from the intrinsic flexibility and stretchability, the non-metal electrode enlarges the potential of thermogalvanic cells in the field of flexible electronics benefiting from the intrinsic flexibility and stretchability.

Conclusion

This study briefly describes the mechanisms and the potential of thermogalvanic cells in low-grade heat harvesting. The trend from liquid-state cells to quasi-solid-state cells and two key factors affecting thermoelectric performance are summarized. Several strategies are introduced for improving thermoelectric performance in the liquid-state and quasi-solid-state thermogalvanic cells. Although current research has yielded advances such as excellent thermoelectric performance output and flexible mechanical properties, there are still some overlooked challenges to address:

1) Poor ionic conductivity: in comparison to conventional solid-state thermoelectric materials, the ionic thermoelectric electrolytes exhibit insufficient conductivity because the ionic mobility is lower than that of electrons. In particular, the weakening of convection in the quasi-solid-state matrix results in much lower ionic conductivity than that of liquid electrolytes.

2) Mismatched thermopower of n-type thermogalvanic cells: the series connection of p-type and n-type cells is a common assemble method, which can enlarge the capacity of the modules for practical applications. However, the current reports mainly focus on the performance enhancement of p-type thermocells. The scarcity of n-type thermocells sufficiently matching the thermopower of p-type thermocells remains to be further investigated.

Author Contributions

WG contributed to the conception of the study. HM wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision and read and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Al-zubaidi, A., Ji, X., and Yu, J. (2017). Thermal Charging of Supercapacitors: a Perspective. Sustain. Energy Fuels 1, 1457–1474. doi:10.1039/c7se00239d

Chae, W. H., Sannicolo, T., and Grossman, J. C. (2020). Double-Sided Graphene Oxide Encapsulated Silver Nanowire Transparent Electrode with Improved Chemical and Electrical Stability. ACS Appl. Mat. Interfaces 12, 17909–17920. doi:10.1021/acsami.0c03587

Duan, J., Feng, G., Yu, B., Li, J., Chen, M., Yang, P., et al. (2018). Aqueous Thermogalvanic Cells with a High Seebeck Coefficient for Low-Grade Heat Harvest. Nat. Commun. 9, 5146. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-07625-9

Duan, J., Yu, B., Huang, L., Hu, B., Xu, M., Feng, G., et al. (2021). Liquid-state Thermocells: Opportunities and Challenges for Low-Grade Heat Harvesting. Joule 5, 768–779. doi:10.1016/j.joule.2021.02.009

Duan, J., Yu, B., Liu, K., Li, J., Yang, P., Xie, W., et al. (2019). P-N Conversion in Thermogalvanic Cells Induced by Thermo-Sensitive Nanogels for Body Heat Harvesting. Nano Energy 57, 473–479. doi:10.1016/j.nanoen.2018.12.073

Fan, Z., Zhang, Y., Pan, L., Ouyang, J., and Zhang, Q. (2021). Recent Developments in Flexible Thermoelectrics: From Materials to Devices. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 137, 110448. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2020.110448

Gao, W., Lei, Z., Chen, W., and Chen, Y. (2022). Hierarchically Anisotropic Networks to Decouple Mechanical and Ionic Properties for High-Performance Quasi-Solid Thermocells. ACS Nano 16, 8347–8357. doi:10.1021/acsnano.2c02606

Gao, W., Lei, Z., Zhang, C., Liu, X., and Chen, Y. (2021). Stretchable and Freeze-Tolerant Organohydrogel Thermocells with Enhanced Thermoelectric Performance Continually Working at Subzero Temperatures. Adv. Funct. Mat. 31, 2104071. doi:10.1002/adfm.202104071

Han, C.-G., Qian, X., Li, Q., Deng, B., Zhu, Y., Han, Z., et al. (2020). Giant Thermopower of Ionic Gelatin Near Room Temperature. Science 368, 1091–1098. doi:10.1126/science.aaz5045

Hu, R., Cola, B. A., Haram, N., Barisci, J. N., Lee, S., Stoughton, S., et al. (2010). Harvesting Waste Thermal Energy Using a Carbon-Nanotube-Based Thermo-Electrochemical Cell. Nano Lett. 10, 838–846. doi:10.1021/nl903267n

Jiao, N., Abraham, T. J., MacFarlane, D. R., and Pringle, J. M. (2014). Ionic Liquid Electrolytes for Thermal Energy Harvesting Using a Cobalt Redox Couple. J. Electrochem. Soc. 161, D3061–D3065. doi:10.1149/2.009407jes

Kim, T., Lee, J. S., Lee, G., Yoon, H., Yoon, J., Kang, T. J., et al. (2017). High Thermopower of Ferri/ferrocyanide Redox Couple in Organic-Water Solutions. Nano Energy 31, 160–167. doi:10.1016/j.nanoen.2016.11.014

Lei, Z., Gao, W., and Wu, P. (2021). Double-network Thermocells with Extraordinary Toughness and Boosted Power Density for Continuous Heat Harvesting. Joule 5, 2211–2222. doi:10.1016/j.joule.2021.06.003

Lei, Z., Gao, W., Zhu, W., and Wu, P. (2022). Anti-Fatigue and Highly Conductive Thermocells for Continuous Electricity Generation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2201021. doi:10.1002/adfm.202201021

Li, M., Hong, M., Dargusch, M., Zou, J., and Chen, Z.-G. (2021). High-efficiency Thermocells Driven by Thermo-Electrochemical Processes. TRENDS Chem. 3, 561–574. doi:10.1016/j.trechm.2020.11.001

Liu, Y., Zhang, Q., Odunmbaku, G. O., He, Y., Zheng, Y., Chen, S., et al. (2022). Solvent Effect on the Seebeck Coefficient of Fe2+/Fe3+ Hydrogel Thermogalvanic Cells. J. Mat. Chem. A. doi:10.1039/d1ta10508f

Peng, P., Zhou, J., Liang, L., Huang, X., Lv, H., Liu, Z., et al. (2022). Regulating Thermogalvanic Effect and Mechanical Robustness via Redox Ions for Flexible Quasi-Solid-State Thermocells. Nano-Micro Lett. 14, 81. doi:10.1007/s40820-022-00824-6

Romano, M. S., Li, N., Antiohos, D., Razal, J. M., Nattestad, A., Beirne, S., et al. (2013). Carbon Nanotube - Reduced Graphene Oxide Composites for Thermal Energy Harvesting Applications. Adv. Mat. 25, 6602–6606. doi:10.1002/adma.201303295

Suarez, F., Parekh, D. P., Ladd, C., Vashaee, D., Dickey, M. D., and Öztürk, M. C. (2017). Flexible Thermoelectric Generator Using Bulk Legs and Liquid Metal Interconnects for Wearable Electronics. Appl. ENERGY 202, 736–745. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.05.181

Taheri, A., MacFarlane, D. R., Pozo-Gonzalo, C., and Pringle, J. M. (2018). Quasi-solid-State Electrolytes for Low-Grade Thermal Energy Harvesting Using a Cobalt Redox Couple. ChemSusChem 11, 2788–2796. doi:10.1002/cssc.201800794

Taroni, P. J., Santagiuliana, G., Wan, K., Calado, P., Qiu, M., Zhang, H., et al. (2018). Toward Stretchable Self-Powered Sensors Based on the Thermoelectric Response of PEDOT:PSS/Polyurethane Blends. Adv. Funct. Mat. 28, 1704285. doi:10.1002/adfm.201704285

Wang, Y., Yang, L., Shi, X. L., Shi, X., Chen, L., Dargusch, M. S., et al. (2019). Flexible Thermoelectric Materials and Generators: Challenges and Innovations. Adv. Mat. 31, 1807916. doi:10.1002/adma.201807916

Wijeratne, K., Vagin, M., Brooke, R., and Crispin, X. (2017). Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)-tosylate (PEDOT-Tos) Electrodes in Thermogalvanic Cells. J. Mat. Chem. A 5, 19619–19625. doi:10.1039/C7TA04891B

Wu, J., Black, J. J., and Aldous, L. (2017). Thermoelectrochemistry Using Conventional and Novel Gelled Electrolytes in Heat-To-Current Thermocells. Electrochimica Acta 225, 482–492. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2016.12.152

Wu, X., Gao, N., Jia, H., and Wang, Y. (2021). Thermoelectric Converters Based on Ionic Conductors. Chem. Asian J. 16, 129–141. doi:10.1002/asia.202001331

Yang, P., Liu, K., Chen, Q., Mo, X., Zhou, Y., Li, S., et al. (2016)Wearable Thermocells Based on Gel Electrolytes for the Utilization of Body Heat. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 12050–12053. doi:10.1002/anie.201606314

Zhang, D., Mao, Y., Ye, F., Li, Q., Bai, P., He, W., et al. (2022). Stretchable Thermogalvanic Hydrogel Thermocell with Record-High Specific Output Power Density Enabled by Ion-Induced Crystallization. Energy Environ. Sci. doi:10.1039/d2ee00738j

Zhang, L., Shi, X.-L., Yang, Y.-L., and Chen, Z.-G. (2021). Flexible Thermoelectric Materials and Devices: From Materials to Applications. Mater. TODAY 46, 62–108. doi:10.1016/j.mattod.2021.02.016

Zhou, H., and Liu, P. (2018). High Seebeck Coefficient Electrochemical Thermocells for Efficient Waste Heat Recovery. ACS Appl. Energy Mat. 1, 1424–1428. doi:10.1021/acsaem.8b00247

Zhou, H., Yamada, T., and Kimizuka, N. (2016). Supramolecular Thermo-Electrochemical Cells: Enhanced Thermoelectric Performance by Host-Guest Complexation and Salt-Induced Crystallization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 10502–10507. doi:10.1021/jacs.6b04923

Keywords: thermoelectric, thermogalvanic cells, energy conversation, low-grade heat, heat harvesting

Citation: Meng H and Gao W (2022) Potential and Challenges of Thermogalvanic Cells for Low-Grade Heat Harvesting. Front. Energy Res. 10:958009. doi: 10.3389/fenrg.2022.958009

Received: 31 May 2022; Accepted: 20 June 2022;

Published: 19 July 2022.

Edited by:

Fulai Zhao, Tianjin University, ChinaReviewed by:

Wei Shao, Westlake University, ChinaGulnur Kalimuldina, Nazarbayev University, Kazakhstan

Copyright © 2022 Meng and Gao. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wei Gao, d2VpZ2FvQGcuaGFydmFyZC5lZHU=

Haofei Meng

Haofei Meng Wei Gao

Wei Gao