- 1Department of Pharmacy, Shanghai Fourth People’s Hospital, School of Medicine, Tongji University, Shanghai, China

- 2Department of Pharmacy, Peking University Third Hospital, Beijing, China

- 3Department of Pharmacy Administration and Clinical Pharmacy, School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Peking University, Beijing, China

- 4School of Pharmacy, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China

- 5Department of Clinical Pharmacy, Shanghai General Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

- 6Department of Clinical Pharmacy, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai, China

Introduction: The safety concerns of Bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibitors (BTKis) have garnered significant attention due to their severe adverse reactions. However, no existing studies have utilized VigiBase, the world's largest adverse event reporting system, to conduct post-marketing safety analyses of these agents.

Methods: This study extracted data from VigiBase and the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS), employing the reporting odds ratio as the primary method and information component as supplementary, to comprehensively evaluate the safety profiles of ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, and zanubrutinib, with a focus on bleeding risks when combined with anticoagulants or antiplatelet drugs.

Results: The results revealed that at the system organ class level, ibrutinib had the strongest signal in cardiac disorders; acalabrutinib in blood and lymphatic system disorders; and zanubrutinib in infections and infestations and blood and lymphatic system disorders. Among the top ten standardised medical dictionary for regulatory activities queries (SMQ), the SMQs with the strongest signals were different for each BTKis, but five identical SMQs were in the top ten, namely supraventricular tachyarrhythmias, tumour lysis syndrome, haematopoietic thrombocytopenia, haemorrhage terms (excl laboratory terms), and haemorrhage laboratory terms. At the preferred term level, acalabrutinib exhibited the strongest signal for Richter’s syndrome, zanubrutinib for subcutaneous haemorrhage, while ibrutinib displayed divergent signals between databases—Bing-Neel syndrome in VigiBase and haematotympanum in FAERS. Importantly, bleeding risks varied significantly between monotherapy and combination therapy with anticoagulants/antiplatelet agents, underscoring the need for clinical vigilance regarding site-specific haemorrhage risks.

Discussion: These results will provide new data to support the use of BTKis and further safety warnings. However, as a hypothesis-generating approach, it does not establish a definitive causal relationship, which will require further research and validation.

1 Introduction

Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) is a member of the tyrosine kinase expressed in hepatocellular carcinoma (TEC) family, and as a key kinase in the B cell receptor pathway (1, 2). BTK plays a critical role in various pivotal signaling processes in vivo, including B cell proliferation, trafficking, chemotaxis, and adhesion (3). Based on the crucial role of BTK, abnormalities in BTK can lead to chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)/small lymphocytic lymphoma, mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia, and so on (4–6). Therefore, BTK has become an essential target for treating B-cell malignancies.

In 2013, the FDA approved the marketing of ibrutinib, the first BTK inhibitor developed by Johnson Johnson and Pharmacyclics. The 2nd-generation BTK inhibitor acalabrutinib, developed by AstraZeneca, was approved for marketing by the FDA in 2017. In 2019, the Chinese pharmaceutical company BeiGene developed a Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor (BTKi) called zanubrutinib (7). In addition to this, BTKis that have been approved for marketing are tirabrutinib (8), orelabrutinib (9), and pirtobrutinib. However, due to the small number of reports in this study, they were not included to avoid unstable signals and an increase in false positive signals. Adverse drug events (ADEs) of BTKis are diverse and are concentrated in the cardiac system, dermatologic system, gastrointestinal system, infection-related, and bleeding-related ADEs (10). Currently, some studies have applied the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) to compare the safety of three BTKis in the occurrence of cardiac risks (11), urinary tract infection (12), and bleeding ADEs (13). A study also analyzed the safety of BTKis alone and in combination with other chemotherapeutic agents (14). There are no studies that have analyzed the post-marketing safety of BTKis using data from VigiBase (15), which is the world’s largest ADE reporting system. In this study, the safety of three BTKis will be analyzed at the system organ class (SOC), standardized medical dictionary for regulatory activities (MedDRA) queries (SMQ), and preferred term (PT) levels using two of the world’s largest spontaneous reporting systems (SRSs), FAERS and VigiBase. Hemorrhagic events are a major safety concern in targeted cancer therapy, as they may lead to treatment interruption, disease progression, or death (16). Patients receiving BTKis often require concomitant antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation (AF), ischemic heart disease, or venous thromboembolism—conditions that may themselves be precipitated or exacerbated by BTK inhibition (17). The concomitant use of BTKis with anticoagulant or antiplatelet agents produces additive impairment of hemostasis, markedly increasing the risk of severe bleeding complications (18, 19). So we also analyzed the risk of bleeding when BTKis are used alone or in combination with anticoagulants/antiplatelets, which is expected to provide more data support and further reference for the safe and rational use of BTKis in clinical practice.

2 Methods

2.1 Data sources and procedures

We profiled the ADEs of BTKis by extracting data from FAERS (from the inception to Q2, 2024) and VigiBase (from the inception to May 6, 2024). The FAERS is a publicly accessible database that collects extensive reports of ADEs observed in clinical practice, providing a valuable resource for exploring potential links between drug use and ADEs (16). We used the open tool OpenVigil 2.1 and R 4.4.2 to mine and clean pharmacovigilance data from FAERS. VigiBase includes over 35 million individual case safety reports (ICSRs) of suspected ADEs (as of May 2024) submitted by national pharmacovigilance centers since 1968. We performed a disproportionality analysis of BTKis in the two international SRSs to improve the reliability of the results. We included ICSRs designated as “primary/secondary suspected” or “interacting” but excluded those characterized as “concomitant”. All ADEs were coded using MedDRA version 26.1. The narrow version of the SMQ was used because it provides better predictability while retaining comparable sensitivity to the broad version (20).

2.2 Statistical analysis

First, the disproportionality analysis was calculated based on Supplementary Table S1. In this table, N11 represents the number of cases reporting the target ADE while using the target drug; N10 represents the number of cases reporting non-target ADEs while using the target drug; N01 represents the number of cases reporting the target ADEs while using other drugs; and N00 represents the number of cases reporting non-target ADEs while using other drugs. These values were used for signal detection analysis to evaluate the potential association between the target drug and the target ADEs. We employed the reporting odds ratio (ROR) to indicate the presence of risk signals. Because of the small number of co-medication reports, we exceptionally used the information component (IC) method, an assay suitable for a small sample size, for signal mining (21). Equations (1) and (2) present the formulas for calculating the ROR and its 95% confidence interval (CI), whereas equations (3), (4), (5), and (6) describe the calculation of the IC and its 95% CI. (22).

A signal with disproportionate reporting is defined as having an ROR025 > 1 and at least 3 cases, or an IC025 > 0 (22, 23). Signal prioritization employed ROR025 values derived from VigiBase, the higher-reporting-volume database, to ensure analytical robustness. Patient demographic distributions and disproportionality metrics were processed through Microsoft Office Excel 2021 and Power BI.

3 Results

3.1 Patient characteristics

As shown in Figure 1; Supplementary Table S2, ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, and zanubrutinib collected 68410, 5659, and 1292 reports in the VigiBase; and 65530, 6050, and 1351 reports in the FAERS, respectively. When we do not consider unknown data, the proportion of reports was greater in males than in females and was highest in the 71–80 age group. In addition, the proportion of deaths was highest for acalabrutinib and lowest for zanubrutinib.

Figure 1. Patient characteristics of BTKis-related ADEs reports in VigiBase and FAERS. (A) Stacked barcharts for age groups (0-60, 61-70,71-80, 81 and above, unknown) reporting on FAERS and VigiBase databases for Zanubrutinib, Acalabrutinib, and lbrutinib. (B) A bar graph displaying sex distribution of reports in FAERS and VigiBase for the three drugs. (C) Outcome bar charts for FAERS and VigiBase, categorized by outcomes such as death, hospitalization, and others. (D) Line graphs tracking annual reports from 2020 to 2024 on drugs across both databases.

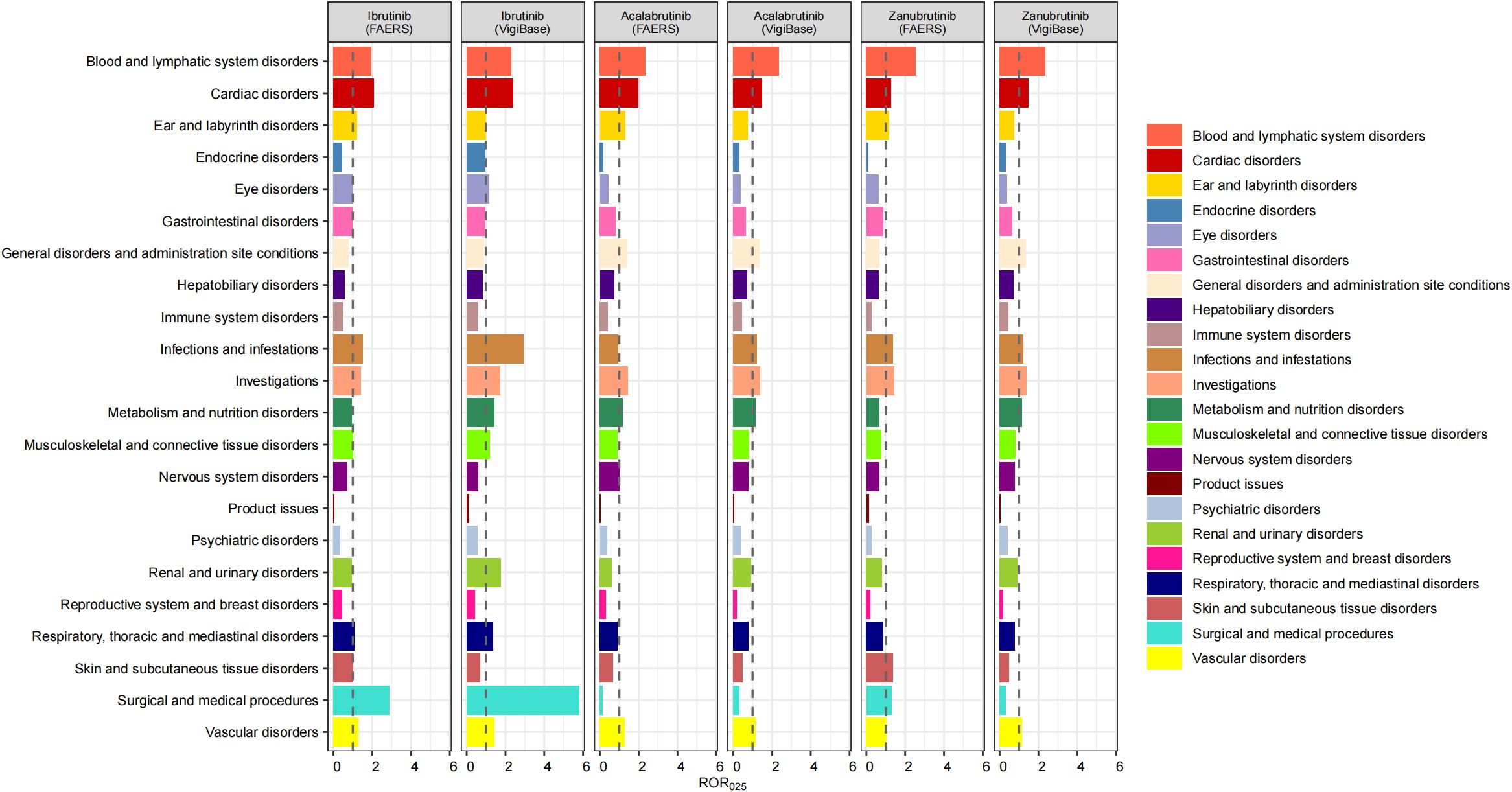

3.2 Signal strength differences of BTKis at the SOC level

For the SOCs of the three BTKis, we excluded SOCs unrelated to the mechanism of action of the drugs, including injury, poisoning and procedural complications, congenital, familial and genetic disorders, social circumstances, neoplasms benign, malignant and unspecified, and pregnancy, puerperium and perinatal conditions. In both SRSs, significant signals were found for each BTKi in blood and lymphatic system disorders, vascular disorders, investigations and cardiac disorders. However, there were slight differences in the intensity of the signals between the drugs. Specifically, zanubrutinib had a lower signal intensity in vascular disorders but the strongest signal in blood and lymphatic system disorders than the other two drugs. The signal for the cardiac disorders was strongest in ibrutinib. In addition, only acalabrutinib suggested risk signals regarding metabolism and nutrition disorders in both SRSs. Significant signals for respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders, and musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders were only suggested for ibrutinib in both SRSs. Further, the signals for infections and infestations were significant in all 3 BTKis (no significant signals for acalabrutinib in FAERS). We also found that all 3 BTKis suggested signals in ear and labyrinth disorders in FAERS but not in VigiBase. Details of the signal strength distribution across individual drugs are presented in Figure 2.

3.3 Signal strength of BTKis at the SMQ level

The VigiBase database does not provide ADE signal data for all SMQs; therefore, the SMQ-level ADE signal data is solely derived from FAERS. We collected 65 positive signals for ibrutinib, 36 for acalabrutinib, and 40 for zanubrutinib in the SMQ hierarchy. After excluding tumor-related SMQs, the top ten SMQs ranked based on ROR025 are shown in Table 1. Among them, there are 5 identical SMQ signals that are all ranked in the top ten of the three BTKis. Ibrutinib had the highest risk of supraventricular tachyarrhythmias; acalabrutinib had the highest risk of tumor lysis syndrome; zanubrutinib had the highest risk in the other 3 SMQs.

3.4 Signal strength differences of BTKis at the PT level

We first listed the top ten ADEs regarding signal strength for the three BTKis (Figure 3). Although the absolute signal values varied between the two SRSs, bleeding-related ADEs consistently showed prominent signal strengths across all three drugs, except for hematologic malignancy-related complications such as Richter’s syndrome and Bing-Neel syndrome. Notably, zanubrutinib was associated with an especially strong signal for subcutaneous hemorrhage. More than half of the top ten PTs ranked by signal strength for zanubrutinib were bleeding-related, underscoring the need to carefully monitor bleeding risks. Other bleeding-related signals for ibrutinib and zanubrutinib were comparable in strength. In contrast, bleeding-related ADEs accounted for only 20% to 40% of the top ten PTs for acalabrutinib (in FAERS and VigiBase reports, respectively). However, acalabrutinib showed particularly prominent signals for infection-related ADEs. According to FAERS reports, meningitis streptococcal, bacterial gastroenteritis, and cerebral aspergillosis were among the top ten reported ADEs for acalabrutinib. Despite this, the ROR025 for cerebral aspergillosis was still lower than that associated with ibrutinib, which continued to exhibit stronger signals for infection-related events overall. Importantly, among the three BTKis, acalabrutinib exhibited the most prominent signals for cardiotoxicity and gastrointestinal toxicity, which warrants close monitoring and further investigation into its long-term safety profile.

We also analyzed the ADEs in cardiac disorders. Ibrutinib, acalabrutinib, and zanubrutinib showed 44, 13, and 3 overlapping cardiac-related positive signals in two SRSs, respectively. All three BTKis detected signals for acute myocardial infarction, AF, atrial flutter, cardiac failure, pericardial effusion, and ventricular tachycardia in at least one SRS. Among these, ibrutinib consistently demonstrated the strongest signals for all ADEs except acute myocardial infarction. Both ibrutinib and acalabrutinib showed AF as the strongest signal in the two SRSs. Zanubrutinib had pericardial effusion and atrial flutter as the strongest signals in FAERS and VigiBase, respectively. Acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib exhibited comparable signal strengths for AF, while acalabrutinib displayed the weakest signals for atrial flutter, pericardial effusion, and cardiac failure, suggesting a lower likelihood of these specific ADEs with acalabrutinib use. However, acalabrutinib’s positive signals for acute myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, and acute coronary syndrome indicate that special attention to the prevention of coronary atherosclerotic heart disease may be required during its clinical application. All positive signals related to the cardiac disorders in both SRSs are shown in Supplementary Material 2.

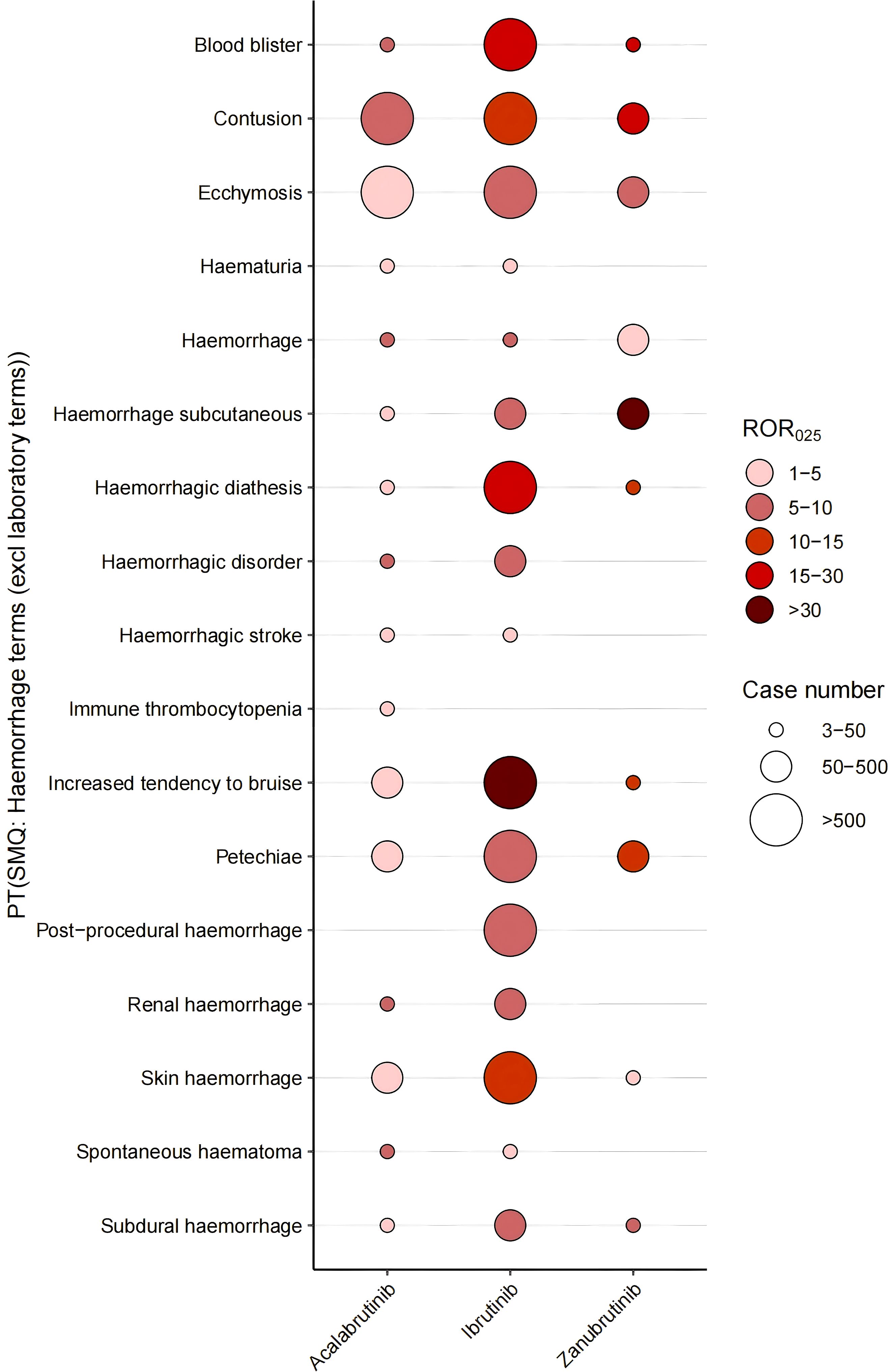

3.5 Comparative analysis of hemorrhagic risk profiles

We first analyzed the hemorrhage-associated PT risk signals for each BTKi in VigiBase. As a whole, zanubrutinib had the strongest signal, and acalabrutinib had the weakest signal. Ibrutinib demonstrated the highest number of hemorrhage-related signals, exhibiting the strongest disproportionality for the majority of bleeding-associated PTs. However, acalabrutinib showed superior signal strength for hemorrhagic disorder and spontaneous hematoma, while zanubrutinib displayed heightened signals for blood blister, contusion, petechiae, hemorrhage subcutaneous, procedural hemorrhage, subdural hemorrhage, hematuria and hemorrhagic stroke (Figure 4). The detailed results are shown in Supplementary Table S3.

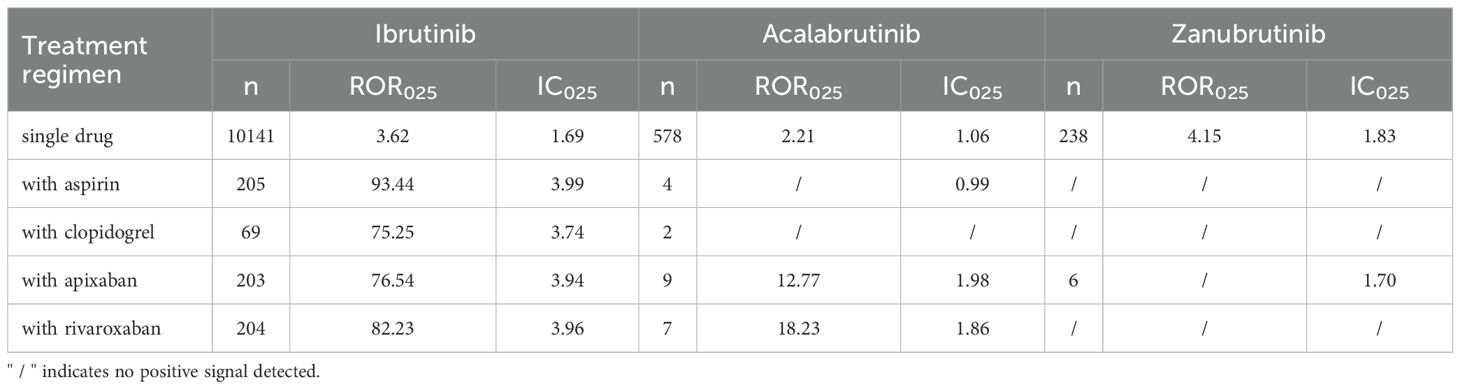

Second, we mined the risk signals of BTKis in combination with aspirin, clopidogrel, apixaban, and rivaroxaban, and the results are shown in Table 2. Due to the very limited reports of zanubrutinib and acalabrutinib co-administered with anticoagulant/antiplatelet agents, we additionally employed the more sensitive IC method to enhance early signal detection. For methodological consistency, we applied the same approach to ibrutinib, despite its comparatively larger number of reports. For zanubrutinib, a significant signal was seen in combination with apixaban when using the IC method only. Currently, the signal strength appears slightly lower than that of monotherapy. However, given that only 6 cases have been reported for the combination therapy, ongoing monitoring of case numbers and signal intensity is required. In contrast, combining acalabrutinib with clopidogrel did not show signal enhancement of bleeding risk. Notably, in the VigiBase, signal intensity for acalabrutinib in combination with apixaban or rivaroxaban exceeded its monotherapy baseline level, suggesting that specific drug combinations may influence risk performance. Ibrutinib in combination with all anticoagulant/antiplatelet agents tested showed significantly higher bleeding risk signal intensity than its monotherapy group. This finding suggests that the combination therapy of ibrutinib with anticoagulant/antiplatelet agents may increase ADEs of bleeding, resulting in a cumulatively higher risk of bleeding. In conclusion, the four anticoagulant/antiplatelet agents exhibited the strongest bleeding ADEs signal in combination with ibrutinib.

Table 2. Haemorrhage risk of BTKis combined with other anticoagulants/antiplatelet agents in VigiBase.

4 Discussion

This study is a comprehensive analysis that utilizes two of the largest SRSs in the world to characterize the safety profile of BTKis in multiple ways. Analyzing the risk of ADEs for three BTKis at different levels and in combination with anticoagulant/antiplatelet agents provides more comprehensive data to support the safe use of BTKis.

Regarding cardiotoxicity, the second-generation BTKis acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib significantly reduced the risk of AF compared to ibrutinib, consistent with evidence from previous clinical trials. This divergence may stem from their enhanced kinase selectivity: ibrutinib exhibits off-target inhibition of TEC family kinases and HER2/HER4 receptors due to lower selectivity, whereas zanubrutinib and acalabrutinib selectively target BTK with minimal HER2 interaction (24, 25). HER2/HER4 play critical roles in myocardial electrical activity and contractile function: HER2/HER4 heterodimerization is a key mechanism for maintaining cardiac signaling, and ibrutinib’s irreversible inhibition of these kinases may trigger myocardial dysfunction (26, 27). Additionally, TEC kinase inhibition may reduce PI3K-AKT signaling in cardiomyocytes, indirectly promoting arrhythmias (24). In contrast, zanubrutinib and acalabrutinib exhibit higher target selectivity: both inhibit HER4 and TEC but not HER2, and differences in TEC inhibition strength do not significantly increase cardiovascular toxicity. Since HER2 is a core driver of ibrutinib-associated AF, avoiding this target by second-generation drugs results in markedly lower AF risk (26). However, it is essential to note that ibrutinib’s broad kinase inhibition leads to significant AF, while acalabrutinib, despite its higher selectivity, shows prominent cardiac toxicity signals. Zanubrutinib generally poses lower risks but requires attention to specific atrial flutter cases.

In the vascular disorders, bleeding and hypertension were the most frequently reported ADEs across all three BTKis. Both acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib were associated with a lower proportion of bleeding events compared to ibrutinib. Previous studies have demonstrated that ibrutinib significantly increases the risk of severe and overall bleeding (16, 28–31), which is largely attributed to its effects on multiple signaling pathways. For second-generation BTKis, a meta-analysis of ten studies indicated that acalabrutinib significantly increases the risk of overall bleeding, but not severe bleeding (16). Furthermore, two head-to-head phase III multicenter trials—comparing zanubrutinib vs. ibrutinib and acalabrutinib vs. ibrutinib, respectively—showed that both acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib were associated with a reduced risk of overall bleeding compared to ibrutinib, with no significant differences observed in the incidence of severe bleeding (32, 33). BTK is essential in BT/VWF-mediated aggregation-induced thromboxane A2 generation and GPIb-dependent stabilization of arterial thrombus formation in vivo (34). Additionally, TEC family kinases, also substrates of ibrutinib, contribute to the downstream regulation of phospholipase Cγ2 (PLCγ2) via the collagen receptor glycoprotein VI (GPVI) on human platelets. Both Tec and BTK are required for platelet activation via GPVI, and Tec has been shown to compensate for BTK deficiency in the regulation of PLCγ2 (35, 36). Moreover, ibrutinib inhibits several intracellular signaling molecules critical for platelet function, including members of the SRC family kinases and JAK3. Inhibition of SRC by BTKis has been linked to impaired platelet aggregation and hemostasis, contributing to increased bleeding risk (16, 37). Although both acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib are also irreversible BTKis capable of selectively inhibiting BTK and Tec at low concentrations in platelets—thereby attenuating low-level GPVI-mediated platelet activation—they do not exhibit the broader off-target inhibition observed with ibrutinib. In particular, they do not significantly inhibit SRC family kinases, which play a central role in platelet signaling. Previous studies have highlighted substantial differences among the three agents’ effects on platelet function (38, 39).

In addition, our study suggests that there is a risk of bleeding when ibrutinib is combined with either anticoagulant or antiplatelet agents. Previous studies have found that about half of patients on ibrutinib develop mild to moderate platelet dysfunction, and this effect is exacerbated when combined with antiplatelet agents (40). Populations typically treated with BTKi drugs, such as those with CLL, MCL, and MZL, often have comorbidities, and there is a recognized risk of new-onset AF associated with BTKis use. Clinicians usually face challenges in treatment decision-making when combining ibrutinib with oral anticoagulants (41). Studies have suggested that acalabrutinib has superior safety characteristics concerning bleeding ADEs, particularly in patients with low sensitivity to platelet aggregation induced by ibrutinib (42), suggesting that switching BTKis in clinical practice may not reduce the risk of bleeding in all patients. Current expert consensus recommends avoiding the concomitant use of potent antiplatelet or anticoagulant agents during BTKi therapy whenever possible. If antithrombotic therapy is necessary, treatment should be initiated with a low-dose BTKi, with cautious dose escalation under close monitoring. For patients undergoing surgery or at high risk of bleeding, temporary discontinuation of BTKis for 3–7 days before and after the procedure is advised. Moreover, when combining BTKis with antithrombotic agents, an individualized risk–benefit assessment should be conducted, balancing thrombotic protection against bleeding risk and considering patient-specific comorbidities (43).

ADEs reports associated with blood and lymphatic system disorders accounted for a large proportion of all ADEs associated with BTKis and showed a high signal intensity. Abnormalities in various tests are frequently concentrated in blood-related examinations. In the usage of all three drugs, signals for abnormal platelet, white blood cell (WBC), and neutrophil counts were reported. In two head-to-head studies, hematologic toxicity had a high incidence among all ADEs. However, acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib did not demonstrate a significant advantage over the first-generation BTKis, ibrutinib, in reducing hematologic toxicity (32, 33). Other real-world studies have also monitored new hematological ADEs, such as splenomegaly and lymphadenopathy. Splenomegaly may affect blood filtration and immune function, while lymphadenopathy suggests potential local or systemic immune response abnormalities (44). It is essential to closely monitor patients’ immune and coagulation functions to prevent serious ADEs like bleeding or infection. In clinical practice, it is recommended to routinely conduct complete blood cell count tests before and during treatment, focusing on monitoring WBC count, platelet count, red blood cell count, and bleeding tendency assessment. If severe hematologic toxicity occurs, BTKi therapy should be paused, and treatment regimens should be adjusted based on the patient’s characteristics and risk-benefit assessment to ensure medication safety (43).

Infectious complications represent another critical category of ADEs associated with BTKi therapy. Overall, all three BTKis were associated with various types of infections. However, in terms of signal strength, the second-generation agents demonstrated a markedly reduced risk of infection-related ADEs compared to the first-generation inhibitor, ibrutinib. Across multiple SOC, including the central nervous system, lungs, skin, and systemic infections, there was a notable increase in the risk of infections caused by specific pathogens. Among these, aspergillus infections were particularly prominent. These findings suggest that patients receiving BTKi therapy, regardless of the generation of the agent, may be at elevated risk for aspergillosis. As such, preventing and managing aspergillus infections should be an important consideration in clinical practice when using these agents. Due to various disease-associated innate and adaptive immune deficiencies, patients with B-cell malignancies are particularly susceptible to infections. A meta-analysis has shown that ibrutinib use is significantly associated with an increased risk of infections in this patient population (45). A systematic review of 44 studies reported that 56% of patients receiving ibrutinib monotherapy and 52% of those receiving combination therapy experienced infection-related ADEs. Notably, approximately one-fifth of patients developed pneumonia (45, 46). The interference with BTK and interleukin-2-inducible T cell kinase signaling pathways in immune cells is considered a key mechanism underlying the increased susceptibility to infections observed with ibrutinib. Several reports have highlighted a particularly high risk of fungal infections, including invasive aspergillosis, associated with ibrutinib use—findings that are consistent with the results of our study (45). A signal was detected only for ibrutinib in a real-world research study specifically investigating the risk of urinary tract infections associated with BTKis treatment. The authors suggested that differences in marketing timelines among the three agents and the greater use of second-generation BTKis as first-line therapies, often in patients with relatively preserved immune function, may significantly influence the detection and reporting of infection-related ADE signals (12).

The impact of medications on liver and kidney function has always been an important area of concern. All three BTKis mention potential hepatotoxicity and nephrotoxicity in their product labels. In our study, we observed a small number of signals related to hepatotoxicity and renal impairment, but their signal strength was at the threshold level, suggesting weak statistical associations. Although these signals may reflect potential risks, their clinical significance should be interpreted cautiously, as they did not reach the threshold for significance. It is advisable to further verify these findings through laboratory tests, dose-dependency analyses, and long-term follow-up data. However, we also identified a few signals that may warrant attention. While the majority of renal-related ADEs were associated with bleeding and infections, such as hematuria and urinary tract infection, we observed a signal for fluid retention in both ibrutinib and zanubrutinib, with a stronger signal in ibrutinib. This suggests that attention to patients’ fluid status may be necessary when using these agents. In the liver system, we identified a signal for hepatitis B reactivation in both zanubrutinib and ibrutinib. This ADE may be related to immune suppression caused by BTKi therapy, rather than a direct hepatotoxic effect (47).

Regarding other systems, we also identified several less frequently mentioned ADEs signals. For example, ibrutinib was associated with middle ear effusion and deafness, while both acalabrutinib and ibrutinib showed signals for glaucoma and iron deficiency. Additionally, all three BTKis were linked to dehydration and appetite disorders. We also observed general disorders such as fatigue and tiredness across the three medications. In clinical practice, it is essential to conduct a multidimensional assessment based on the individual characteristics of patients, combining their baseline conditions with close dynamic monitoring. This approach will help identify ADE signals and optimize treatment strategies, ensuring continuity of care while improving patients’ quality of life.

Our study, like other pharmacovigilance studies, has several limitations. Firstly, there is an inherent bias in the data sources; SRSs may suffer from underreporting, duplicate reporting, and misreporting, and serious or new ADEs are more likely to be reported, whereas minor or common events may be underestimated. This could lead to an increased reporting rate of serious or more closely monitored ADEs over time, amplifying imbalances and thereby exaggerating differences between drugs. Second, the data sources for SRS are variable. FAERS data primarily originates from the United States, while VigiBase data is collected globally. Differences in data collection and processing methods, as well as variations in population bases, may account for discrepancies between signals observed in FAERS and VigiBase. Finally, even if the results of disproportionality analyses are significant, they are unlikely to confirm a causal relationship between drugs and ADEs and represent only a statistical association, a more definite causal relationship requires further verification.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the study involving humans in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent to participate in this study was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

HQ: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Supervision, Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Project administration, Software, Formal analysis. YJ: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization, Software, Investigation, Visualization, Methodology, Formal analysis. ZZL: Data curation, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis. ZAL: Visualization, Writing – original draft, Software. XZ: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Supervision. ZW: Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Investigation. GF: Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Conceptualization, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Resources. YL: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing, Project administration, Resources, Methodology, Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by Bethune Charitable Foundation (Z04JKM2023E040 and Z04J2023E095), Shanghai Shenkang Hospital Development Center Municipal Hospital Diagnosis and Treatment Technology Promotion and Optimization Management Project (SHDC22024202), Scientific and Innovative Action Plan of Shanghai (23S21900900), Wu Jieping Medical Foundation (320.6750.2024-18-2), Shanghai Medical Innovation & Development Foundation (SMIDF-142-1), the Medical Scientific Research Project of the Health and Wellness Committee of Hongkou District, Shanghai (HW2503-07), and the Scientific Research Project of the Discipline Boosting Program of the Shanghai Fourth People’s Hospital (SY-XKZT-2025-1014).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Uppsala Monitoring Centre (UMC), who manages and provides the data used in the present study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Author disclaimer

The views expressed in this study are the authors’ personal views and may not reflect the position of the WHO.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1636657/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Lucas F and Woyach JA. Inhibiting bruton's tyrosine kinase in CLL and other B-cell Malignancies. Target Oncol. (2019) 14:125–38. doi: 10.1007/s11523-019-00635-7

2. Pal Singh S, Dammeijer F, and Hendriks RW. Role of Bruton's tyrosine kinase in B cells and Malignancies. Mol Cancer. (2018) 17:57. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0779-z

3. de Rooij MF, Kuil A, Geest CR, Eldering E, Chang BY, Buggy JJ, et al. The clinically active BTK inhibitor PCI-32765 targets B-cell receptor- and chemokine-controlled adhesion and migration in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. (2012) 119:2590–4. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-11-390989

4. Shirley M. Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors in B-cell Malignancies: their use and differential features. Target Oncol. (2022) 17:69–84. doi: 10.1007/s11523-021-00857-8

5. Phelan JD, Scheich S, Choi J, Wright GW, Häupl B, Young RM, et al. Response to Bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibitors in aggressive lymphomas linked to chronic selective autophagy. Cancer Cell. (2024) 42:238–52.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2023.12.019

6. Buske C, Jurczak W, Salem JE, and Dimopoulos MA. Managing Waldenström's macroglobulinemia with BTK inhibitors. Leukemia. (2023) 37:35–46. doi: 10.1038/s41375-022-01732-9

7. Roskoski R Jr. Properties of FDA-approved small molecule protein kinase inhibitors: A 2023 update. Pharmacol Res. (2023) 187:106552. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2022.106552

8. Dhillon S. Tirabrutinib: first approval. Drugs. (2020) 80:835–40. doi: 10.1007/s40265-020-01318-8

9. Dhillon S. Orelabrutinib: first approval. Drugs. (2021) 81:503–7. doi: 10.1007/s40265-021-01482-5

10. Paydas S. Management of adverse effects/toxicity of ibrutinib. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. (2019) 136:56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2019.02.001

11. Zhai Y, Hu F, Shi W, Ye X, Xu J, Guo X, et al. Pharmacovigilance analysis of cardiac risks associated with Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Expert Opin Drug Saf. (2023) 22:857–69. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2023.2204226

12. Yang H, Ding Z, and An Z. Urinary tract infection following the use of BTK inhibitors: a real-world analysis of post-marketing surveillance data. Expert Opin Drug Saf. (2024) 23:333–8. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2023.2251376

13. Li X, Shang N, Yan Q, Yue X, Liu Y, and Zheng X. Investigating bleeding adverse events associated with BTK inhibitors in the food and drug administration adverse event reporting system (FAERS). Expert Opin Drug Saf. (2025) 24:183–92. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2024.2339448

14. Xiang S, Shen R, Xiang J, Zhu N, Gu J, Shen J, et al. A real-world pharmacovigilance study of FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) events for Bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibitors (BTKis) single and its combination therapy. Expert Opin Drug Saf. (2024) 23:627–36. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2024.2327507

15. Lindquist M. VigiBase, the WHO global ICSR database system: basic facts. Drug Inf journal: DIJ / Drug Inf Assoc. (2008) 42:409–19. doi: 10.1177/009286150804200501

16. Jiang D, Song Z, Hu Y, Dong F, and Zhao R. Risk of bleeding associated with BTK inhibitor monotherapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. (2022) 15:987–96. doi: 10.1080/17512433.2022.2106968

17. Roccograndi LM, Lovell AR, Ferrajoli A, Thompson PA, Burger JA, Wierda WG, et al. Incidence of major bleeding in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia receiving ibrutinib and therapeutic anticoagulation. Leuk Lymphoma. (2023) 64:1554–61. doi: 10.1080/10428194.2023.2223740

18. Raz MA, Arnason J, Bairey O, Shvidel L, Aviv A, Ben Baruch S, et al. The risk of bleeding in patients receiving ibrutinib combined with novel direct oral anticoagulants. Br J Haematol. (2020) 189:e31–e3. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16422

19. Brown JR, Moslehi J, Ewer MS, O'Brien SM, Ghia P, Cymbalista F, et al. Incidence of and risk factors for major haemorrhage in patients treated with ibrutinib: An integrated analysis. Br J Haematol. (2019) 184:558–69. doi: 10.1111/bjh.15690

20. Lin X, Yang J, Weng L, and Lin W. Differences in hypersensitivity reactions to iodinated contrast media: analysis of the US food and drug administration adverse event reporting system database. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. (2023) 11:1494–502.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2023.01.027

21. Candore G, Juhlin K, Manlik K, Thakrar B, Quarcoo N, Seabroke S, et al. Comparison of statistical signal detection methods within and across spontaneous reporting databases. Drug Saf. (2015) 38:577–87. doi: 10.1007/s40264-015-0289-5

22. Noguchi Y, Tachi T, and Teramachi H. Detection algorithms and attentive points of safety signal using spontaneous reporting systems as a clinical data source. Brief Bioinform. (2021) 22:1–14. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbab347

23. van Puijenbroek EP, Bate A, Leufkens HG, Lindquist M, Orre R, and Egberts AC. A comparison of measures of disproportionality for signal detection in spontaneous reporting systems for adverse drug reactions. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. (2002) 11:3–10. doi: 10.1002/pds.668

24. McMullen JR, Boey EJ, Ooi JY, Seymour JF, Keating MJ, and Tam CS. Ibrutinib increases the risk of atrial fibrillation, potentially through inhibition of cardiac PI3K-Akt signaling. Blood. (2014) 124:3829–30. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-10-604272

25. Honigberg LA, Smith AM, Sirisawad M, Verner E, Loury D, Chang B, et al. The Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor PCI-32765 blocks B-cell activation and is efficacious in models of autoimmune disease and B-cell Malignancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2010) 107:13075–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004594107

26. Estupiñán HY, Berglöf A, Zain R, and Smith CIE. Comparative analysis of BTK inhibitors and mechanisms underlying adverse effects. Front Cell Dev Biol. (2021) 9:630942. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2021.630942

27. Chen MH, Kerkelä R, and Force T. Mechanisms of cardiac dysfunction associated with tyrosine kinase inhibitor cancer therapeutics. Circulation. (2008) 118:84–95. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.776831

28. Pellegrini L, Novak U, Andres M, Suter T, and Nagler M. Risk of bleeding complications and atrial fibrillation associated with ibrutinib treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. (2021) 159:103238. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2021.103238

29. Yun S, Vincelette ND, Acharya U, and Abraham I. Risk of atrial fibrillation and bleeding diathesis associated with ibrutinib treatment: A systematic review and pooled analysis of four randomized controlled trials. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. (2017) 17:31–7.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2016.09.010

30. Wang J, Zhao A, Zhou H, Zhu J, and Niu T. Risk of bleeding associated with ibrutinib in patients with B-cell Malignancies: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Pharmacol. (2020) 11:580622. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.580622

31. Caron F, Leong DP, Hillis C, Fraser G, and Siegal D. Current understanding of bleeding with ibrutinib use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood Adv. (2017) 1:772–8. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2016001883

32. Tam CS, Opat S, D'Sa S, Jurczak W, Lee HP, Cull G, et al. A randomized phase 3 trial of zanubrutinib vs ibrutinib in symptomatic Waldenström macroglobulinemia: the ASPEN study. Blood. (2020) 136:2038–50. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020006844

33. Byrd JC, Hillmen P, Ghia P, Kater AP, Chanan-Khan A, Furman RR, et al. Acalabrutinib versus ibrutinib in previously treated chronic lymphocytic leukemia: results of the first randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. (2021) 39:3441–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.01210

34. Liu J, Fitzgerald ME, Berndt MC, Jackson CW, and Gartner TK. Bruton tyrosine kinase is essential for botrocetin/VWF-induced signaling and GPIb-dependent thrombus formation in vivo. Blood. (2006) 108:2596–603. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-01-011817

35. Atkinson BT, Ellmeier W, and Watson SP. Tec regulates platelet activation by GPVI in the absence of Btk. Blood. (2003) 102:3592–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1142

36. Quek LS, Bolen J, and Watson SP. A role for Bruton's tyrosine kinase (Btk) in platelet activation by collagen. Curr Biol. (1998) 8:1137–40. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(98)70471-3

37. Ran F, Liu Y, Wang C, Xu Z, Zhang Y, Liu Y, et al. Review of the development of BTK inhibitors in overcoming the clinical limitations of ibrutinib. Eur J Med Chem. (2022) 229:114009. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2021.114009

38. von Hundelshausen P and Siess W. Bleeding by bruton tyrosine kinase-inhibitors: dependency on drug type and disease. Cancers (Basel). (2021) 13:1–32. doi: 10.3390/cancers13051103

39. Dobie G, Kuriri FA, Omar MMA, Alanazi F, Gazwani AM, Tang CPS, et al. Ibrutinib, but not zanubrutinib, induces platelet receptor shedding of GPIb-IX-V complex and integrin αIIbβ3 in mice and humans. Blood Adv. (2019) 3:4298–311. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2019000640

40. Mulligan SP, Ward CM, Whalley D, and Hilmer SN. Atrial fibrillation, anticoagulant stroke prophylaxis and bleeding risk with ibrutinib therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and lymphoproliferative disorders. Br J Haematol. (2016) 175:359–64. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14321

41. Dhopeshwarkar N, Yang W, Hennessy S, Rhodes JM, Cuker A, and Leonard CE. Bleeding with concomitant ibrutinib and oral anticoagulant therapy: A population-based cohort study. Am J Hematol. (2023) 98:E49–e52. doi: 10.1002/ajh.26802

42. Series J, Garcia C, Levade M, Viaud J, Sié P, Ysebaert L, et al. Differences and similarities in the effects of ibrutinib and acalabrutinib on platelet functions. Haematologica. (2019) 104:2292–9. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2018.207183

43. Song Z, Jiang D, Yu L, Chen Y, Zhou D, Li Y, et al. Evidence-based expert consensus on clinical management of safety of Bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibitors (2024). Chin J Cancer Res. (2024) 36:240–56. doi: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2024.03.02

44. Liang Q, Liao X, Huang Y, Zeng J, Liang C, He Y, et al. Safety study on adverse events of zanubrutinib based on WHO-VigiAccess and FAERS databases. Expert Opin Drug Saf. (2024), 1–8. doi: 10.1080/14740338.2024.2416917

45. Ball S, Das A, Vutthikraivit W, Edwards PJ, Hardwicke F, Short NJ, et al. Risk of infection associated with ibrutinib in patients with B-cell Malignancies: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. (2020) 20:87–97.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2019.10.004

46. Tillman BF, Pauff JM, Satyanarayana G, Talbott M, and Warner JL. Systematic review of infectious events with the Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib in the treatment of hematologic Malignancies. Eur J Haematol. (2018) 100:325–34. doi: 10.1111/ejh.13020

Keywords: BTKis, FAERS, VigiBase, pharmacovigilance, real world study

Citation: Qu H, Jia Y, Liu Z, Li Z, Zhao X, Wu Z, Fan G and Lou Y (2025) A pharmacovigilance study of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors: a multidimensional analysis based on FAERS and VigiBase. Front. Immunol. 16:1636657. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1636657

Received: 28 May 2025; Accepted: 11 November 2025; Revised: 24 October 2025;

Published: 25 November 2025.

Edited by:

Jiyong Liu, Fudan University, ChinaReviewed by:

Fulei Wuchu, University of Michigan, United StatesYinpeng Xu, The Ninth People’s Hospital of Zhengzhou, China

Copyright © 2025 Qu, Jia, Liu, Li, Zhao, Wu, Fan and Lou. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yuefen Lou, bG91eXVlZmVuQHRvbmdqaS5lZHUuY24=; Guorong Fan, Z3VvcmZhbkAxNjMuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Han Qu

Han Qu Yuqi Jia2,3,4†

Yuqi Jia2,3,4† Zuan Li

Zuan Li Xin Zhao

Xin Zhao Zhenghua Wu

Zhenghua Wu Guorong Fan

Guorong Fan Yuefen Lou

Yuefen Lou