- 1Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Illinois College of Medicine, Chicago, IL, United States

- 2Center for Bioinformatics and Quantitative Biology, and Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Illinois Colleges of Engineering and Medicine, Chicago, IL, United States

- 3Research Informatics Core, Research Resources Center, University of Illinois, Chicago, IL, United States

Diverse Igh repertoires require successful V(D)J recombination allowing B cell receptor expression and Ig secretion for humoral immune responses. Igh locus contraction has been implicated in generating spatial proximity between distal VH segments and the recombination center via cohesin mediated loop extrusion. However, it remains unclear why some distal VH segments recombine with high frequency while other more proximal VH are rarely used. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) have emerged as regulators of cellular development, differentiation and gene expression. Here we report exceptionally high expression of lncRNAs at the Igh locus and other AgR loci engaged in V(D)J recombination. A tight correlation was found between positions of multi-exonic lncRNAs, Igh enhancers and chromatin loop anchors. We propose an integrated model of factors including lncRNAs and loop extrusion in determining Igh locus topology and VH gene usage during recombination.

1 Introduction

Adaptive immune responses use antigen receptors (AgRs) expressed on B and T lymphocytes to protect against a multitude of pathogens. Each mature B cell expresses a unique immunoglobulin (Ig) receptor containing two identical Ig heavy (H) chains and two identical light (L) chains (Igκ or Igλ). The variable regions of IgH and IgL chains are assembled from V, D, J and V, J segments, respectively, by V(D)J recombination in B cell progenitors (1, 2). This process is mediated by the lymphocyte-specific RAG1/2 recombinase that creates DNA breaks at recombination signal sequences (RSSs) flanking each V, D and J segment (1, 2). V(D)J recombination for the Igh locus involves a two-step process during which one of 8–12 DH and one of 4 JH gene segments are rearranged to generate a DJ element that is then recombined with one of ~100 functional VH genes in each pro-B cell (3). VH genes rearrange at very different intrinsic frequencies to produce a quasi-random VH gene usage profile (4–6). Evaluation of V germline transcript levels, chromatin accessibility, transcription factor (TF) binding, RSS quality, and epigenetic profiles indicates that no single variable fully accounts for skewed VH gene usage (4–6). The observation that VH gene families are clustered in the locus (3) and display characteristic features regarding the position of bound CTCF (7, 8), regionally distributed histone modifications, RNAPII and TF binding (4, 5) suggests that VH segment selection for each group may be differentially regulated. Nevertheless, the mechanisms underlying unequal VH gene rearrangement frequencies remain unresolved.

Mammalian chromosomes at the Mb scale are organized into topological associating domains (TADs) that span spatial neighborhoods of high frequency self-associating chromatin contacts (9–11). The Igh locus is contained within a 2.9-Mb TAD that is divided into three subTADs and VH gene families are regionally arrayed within this spatial genomic context (12, 13). TADs are frequently anchored by motifs bound by the CTCF architectural protein and its interaction partner, cohesin (14, 15). Cohesin maintains TAD structure by progressively extruding DNA loops until encountering a dominant obstacle such as a bound convergently oriented CTCF which halts movement and anchors DNA loops in mammalian cells (16, 17). The loop extrusion model explains how enhancers (Es) can processively track arrays of promoters (Prs) through the extruding chromatin loop over long genomic intervals (16–19).

The Igh locus is in an extended configuration in non-B cells and lymphoid progenitors and becomes contracted on both alleles in pro-B cells when V->DJ rearrangements occur (20, 21). Igh locus contraction is cohesin dependent as acute depletion of WAPL (Wings apart like protein), the cohesin release factor (22, 23), leads to both increased chromatin loop formation and locus contraction. Relatedly, TF PAX5 mediates locus contraction and distal VH gene recombination (20, 24) through its suppression of Wapl transcription (22) linking these processes. The Alt group has established the RAG scanning model to explain how distal VH segments in contracted Igh loci become spatially situated proximal to the V(D)J recombination center through a linear tracking mechanism with parallels to loop extrusion (reviewed in (25, 26)).

VH gene choice may depend on the dynamics of cohesin mediated loop extrusion which leads to variable loop lengths and different final end-points (27, 28). Impediments to loop extrusion are likely to influence the local-regional propensity for chromatin loop formation and VH segment engagement in recombination (25). Antisense RNA expression has been detected at discrete sites within the Igh locus (29), however, the extent to which this expression modulates Igh locus function is unknown. In this context, it is intriguing to consider the potential regulatory influence of long non-coding (lnc) RNAs that can originate from thousands of loci genomewide (reviewed in (30–32)). LncRNA functions include modulation of chromatin architecture, transcription, RNA processing and splicing (33–35), within the B cell lineage (36), and in processes such as V(D)J recombination and class switch recombination (CSR) (37, 38). Here we report highly elevated expression of lncRNAs in B- and T-cell progenitors undergoing V(D)J recombination. We document hundreds of Igh associated lncRNAs that cluster to TAD anchors and enhancers of pro-B cells. We provide a perspective on the interplay of Igh lncRNAs, locus structure and VH gene choice during V(D)J recombination.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Mice, pro-B cells and cell lines

Rag2-/- mice on the C57BL/6 background were purchased from Jackson Laboratories or maintained in colonies at the University of Illinois College of Medicine. All procedures involving mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care Committee of the University of Illinois College of Medicine in accordance with protocols approved by the UIC Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees. Mice were housed in sterile static microisolator cages with water bottles and on autoclaved corncob bedding. Irradiated food was (Envigo 7912), and autoclaved water were provided ad libitum. Mice receive autoclaved nesting material to enrich their environments. Cage bedding is changed in either a biosafety cabinet or a HEPA filtered animal transfer station at least weekly. Housing density and cage size are consistent with the recommendations of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Mouse rooms received the standard photoperiod of 14 hours of light and 10 hours of darkness. The ambient temperature and humidity of the rodent housing rooms are consistent with the recommendations of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Rag2-/- pro-B cells were isolated from BM using anti-CD19 coupled magnetic beads (Miltenyi, catalogue number 130-121-301, RRID: AB_2827612) and cultured in the presence of IL7 (1% vol/vol supernatant of a J558L cell line stably expressing IL7) for 4 days. The Abelson-MuLV transformed (Abl-t) pro-B cell line, 445.3 (Rag1-/-) on the C57Bl/6 background was kindly provided by Dr. B. Sleckman (University of Alabama at Birmingham) (39). The 445.3.11 subclone from the Abl-t 445.3 line was cultured in RPMI 1640 (Corning, 15040CV), 10% (v/v) FBS, 4mM glutamine (Gibco), 1mM sodium pyruvate (Gibco), 1X nonessential amino acid (Gibco), 5000 units/ml Penicillin and 5000 mg/ml Streptomycin (Gibco), 50 mM b-mercaptoethanol (Sigma) and maintained at approximately 5x10e5 cells/ml. Splenic T cells were isolated using Mouse T Cell Enrichment Columns (MTCC-5; R&D Systems) and cultured (5X10e5 to 1X10e6 cells/ml) in RPMI 1640 and glutamine (4 mM) with Penicillin- Streptomycin supplemented with FCS (10% v/v), and activated with Con A (5 ng/ml; 15324505; MP Biomedicals).

2.2 Genome-wide LncRNA annotation, ChIP-seq data sets and RT-PCR assays

2.2.1 LncRNA annotation

Published RNA-seq datasets from Rag1-/- pro-B cells (GEO accession numbers: GSM1897405, GSM1897406, GSM1897407) (40), pre-B cells from Rag1-/-μ+ mice bearing a rearranged Igμ transgene (GEO accession numbers: GSM1897411, GSM1897412, GSM1897412) (41), RAG-/-YY1f/f x Mb1-Cre pro-B cells (GEO accession numbers: GSM1897408, GSM1897409, GSM1897410) (41), Rag1-/- thymocytes bearing a TCRβ transgene (GEO accession numbers: GSM1701762, GSM1701763, GSM1701764) (42), Rag1-/- CD3 activated DP thymocytes (GEO accession numbers: GSM1701765, GSM1701766, GSM1701767) (42), Rag2-/- CD3 activated DP thymocytes (GEO accession numbers: GSM1701768, GSM1701769, GSM1701770) (42) were analyzed. Reads were concatenated from two-three independent samples and mapped reads were aligned to the genome (mm10) using STAR (version 2.5.2b, default settings). Transcript assembly was performed with StringTie (version 2.0, default settings) and transcripts (≥300 nucleotides, FPKM ≥0.3) were documented (Supplementary Data Sheets 1–6). LncRNAs derived from the Igh locus in Rag1-/- pro-B cells were annotated (Supplementary Data Sheet 7). The mouse genome (mm10) was subdivided into 100kb bins. Contiguous bins expressing lncRNA transcripts were merged into windows. Window boundaries were defined as occurring when >2 bins lacking lncRNA transcripts. Each window was analyzed for the number of aligned lncRNA transcripts (hits), transcript length, weighted coverage (total transcript length x expression (FKPM)) and an overall window score was calculated by taking the sum of the three criteria scores for each window (Supplementary Data Sheets 8–13). LncRNA transcript genomic coordinates were converted to mm9 for visualization. Supplementary Data Sheets 1–13 are available at: https://uofi.box.com/s/1lynmquf08ct0qtp4swxg713foaa34v5.

2.2.2 ChIP-seq data sets used to analyze the Igh locus in pro-B cells

Public ChIP-seq data sets were analyzed for Rag deficient pro-B cells: H3K27ac (GEO accession number: GSM2255552) (43); H3K4me1 (GEO accession number: GSM546527) (44); p300 (GEO accession number: GSM987808) (44); CTCF (GEO accession number: GSM1156665) (4); Rad21 (GEO accession number: GSM1156667) (4); E2A (GEO accession number: GSM546523 (44); RNA Pol II (GEO accession number: GSM1156660) (4).

2.2.3 RT-PCR assays

RNA extraction was performed from BM Rag2-/- pro-B cells (2-3x106 cells) using TRIzol (Life Technologies) and then treated with DNase with the DNase I kit (Invitrogen) all according to manufacturer’s instructions. CDNA synthesis was performed using RNA (1 µg) and the SuperScript II Reverse Transcriptase kit (Invitrogen) per the manufacturer’s instructions. RT-PCR assays for lncRNA transcripts were carried out using 10x Platinum Taq reaction buffer (2.5.μl), 50mM MgCl2 (0.75μl), 10mM dNTPs (0.5μl), forward (0.5μl) and reverse (0.5μl) primer (10mM), cDNA (2μl), and 0.1μl Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) (5U/μl) in a 25μl reaction volume. A touchdown PCR was performed: 95C, 3’; 10 cycles (95C, 30” 64C, 45”; -1 degree C each cycle; 72C, 30”), 25 cycles (95C, 30”; 54C, 45”; 72C, 30”; 72C, 5’) 4C hold. PCR products were visualized on a 1.5-2% agarose gel electrophoresis. Primers are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

2.3 Hi-C library construction and analyses

Genome-wide in situ HiC libraries were constructed from Rag2-/- pro-B cells expanded in IL7 for 4–5 days using Arima Hi-C kits (Arima Genomics, San Diego, CA) as recommended by the manufacturer, as previously described (45). In situ Hi-C was performed using two biological replicates that yielded a minimum of 1.3 billion read pairs and 0.72 billion from pro-B cells of each genotype (GEO Accession No. GSE201357) (Supplementary Table 2). Published in situ Hi-C data sets for mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were constructed with Arima Hi-C kits (GEO Accession No. GSE113339) and data was handled in parallel with the pro-B cell data. In situ Hi-C data was processed using the Juicer pipeline (v.1.5), CPU version (46). Extraction of virtual 4C interaction matrices: Hic files derived using Juicer tools were used to generate virtual 4C viewpoints from dumped matrices generated in Juicebox. KR normalized observed read matrices were extracted at 10kb resolution. The biological replicates had stratum adjusted correlation coefficient (SCC) (47) greater than 0.9 and were merged. The interaction profile of virtual 4C were plotted by running a rolling window of 30kb with a 10kb slide. Generation of Hi-C difference maps: Experimentally measured Hi-C contact matrices of individual replicate and merged samples were quantile normalized against the Hi-C contact matrices of the uniformly sampled random ensemble of the corresponding cell type as previously described (45).

2.4 3C library construction and analysis.

3C chromatin was prepared from CD19+ IL7 expanded Rag2-/- pro-B cells, the Abl-t 445.3.11 line and ConA activated splenic T cells as previously described (45, 48). 3C library construction using Hind III and assays for the Igh locus were performed as described earlier (49, 50). Quantitative PCR (qPCR) in combination with 5’FAM and 3’BHQ1 modified probes (IDT) was used to detect of 3C products and primers were designed using Primer Express software (ABI) (Supplementary Table 3). Primer and probe optimization were carried out according to the manufacturer’s recommendations, (http://www3.appliedbiosystems.com/cms/groups/mcb_support/documents/generaldocuments/cms_042996.pdf). P values were calculated by using two-tailed Student’s t test. In all cases p values are shown.

2.5 ATAC-seq and analysis

ATAC-seq libraries were constructed from purified CD19+ Rag2-/- pro-B cells (5x104/sample) that had been expanded in IL7 for five days using the Nextera DNA Library Prep Kit (Illumina) according to the manufacturer’s instructions with the following exception. Cells were lysed in cold C1 buffer (50ml) (10 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 5 mM MgCl2, 11% sucrose, 1% Triton X-100) and incubated for 10 min on ice to generate nuclei. DNA was purified using the Zymo DNA Clean & Concentration Kit (D4013). DNA tagmentation fragments were amplified as specified (51) and used for Nextera library construction followed by NGS analysis. Adaptor sequences were trimmed using SeqPurge (v2019_11) and trimmed reads were mapped to mm10 mouse genome assembly using Bowtie2 (v2.2.9) with settings – very-sensitive -X 2000. PCR duplicates were removed using Picard (v2.21.8) MarkDuplicates REMOVE_DUPLICATES=true VALIDATION_STRINGENCY=LENIENT. Reads with MAPQ scores below 30 were purged using samtools (v1.9) view with settings -b -q 30 -f 2 -F 1804. The samples 1) Rag2KO_1 had 34923628 total paired-end reads of which 98.4% were mapped and 2) Rag2KO_2 had 68921951 total paired-end reads of which 97.2% were mapped. Peak calling and sample normalization were carried out as described (52). To facilitate comparison of peaks across samples, the MACS2 peak scores (-log10(p-value)) for each sample were converted to a score per million (SPM) by dividing each peak score by the sum of all of the peak scores in a sample divided by 1 million. Sample peak sets were merged, less significant overlapping peaks removed, and remaining peaks were filtered for those that were observed in at least two samples with an SPM value 2. To generate peak-by-sample count matrices, ATAC fragment counts within each peak were normalized by the number of inserts intersecting nucleosome-depleted promoter regions (-300 bp to +100 bp relative to transcriptional start-sites). ATAC-seq library data are available (GEO accession number: GSE214081). ATAC-seq files were converted to genome coordinates mm9 for visualization.

3.0 Results

3.1 Novel lncRNAs are highly enriched at the Igh locus in pro-B cells

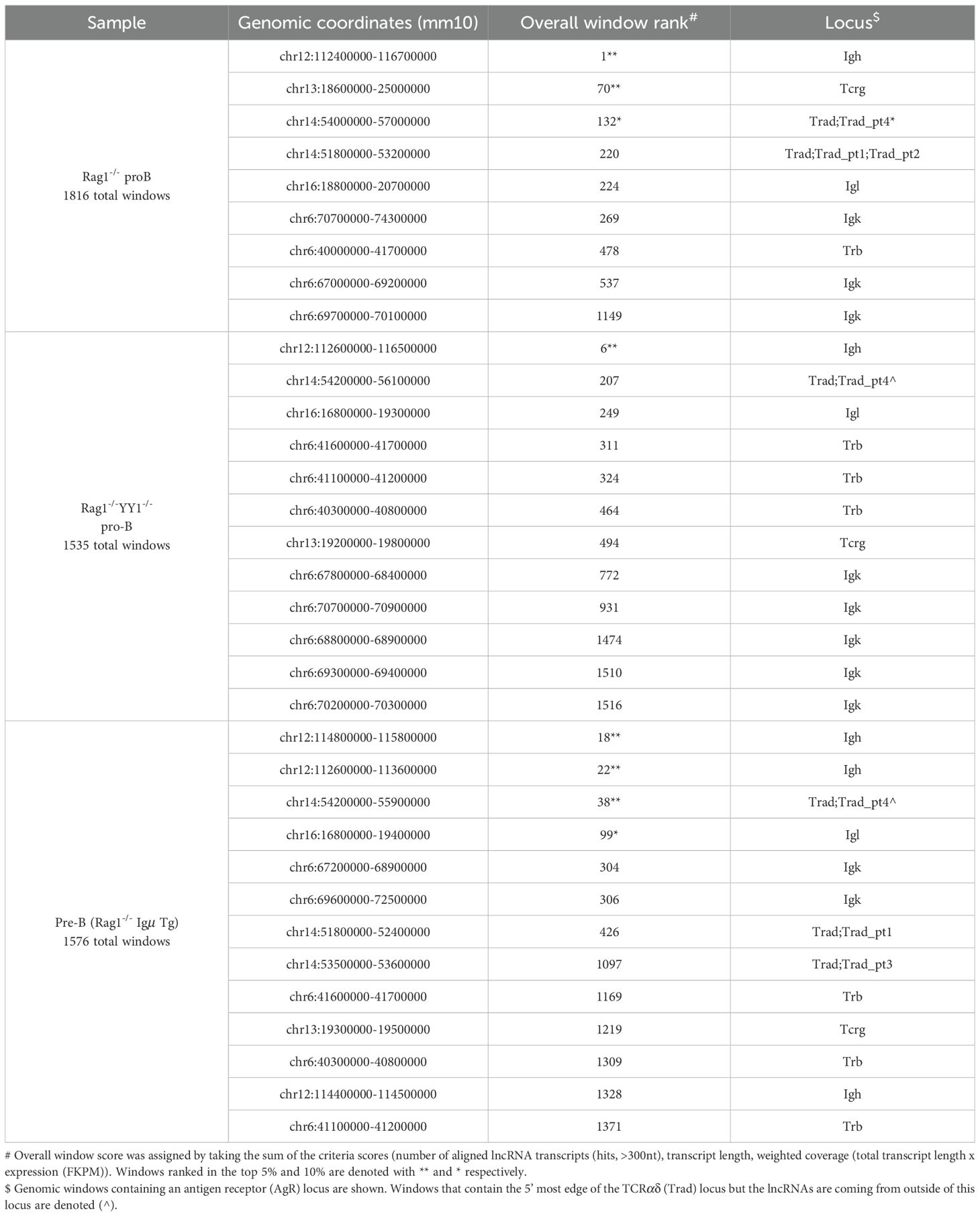

We analyzed RNA-seq datasets to identify novel lncRNA transcripts expressed in Rag1-/- pro B cells (Supplementary Data Sheet 1) (40). The mouse genome was subdivided into 100kb bins which were assessed for the number of unannotated aligned transcripts (hits, >300nt), transcript length, weighted coverage (total transcript length x expression (FKPM)). An overall bin score was calculated by taking the sum of the three criteria scores. Contiguous bins containing expressed lncRNA transcripts were merged into windows and window boundaries were defined as >2 consecutive 100kb bins lacking these transcripts. Windows were ranked for lncRNA expression genomewide using the three criteria scores. The Igh locus was encompassed in a single window and attained the top ranked overall score demonstrating that this region is exceptionally enriched with expressed lncRNAs in Rag1-/- pro-B cells (Table 1). In contrast, the Igλ and Igκ loci, which do not undergo rearrangement until the pre-B cell stage of development, attained window scores of 224 and 269, respectively suggesting a strong correlation between locus specific lncRNA expression and V(D)J recombination potential (Supplementary Data Sheet 2) (Table 1).

To test the specificity of lncRNA transcript expression in the Igh locus of pro-B cells we evaluated three independent RNA-seq datasets from double positive (DP) CD4+CD8+ thymocytes that are incapable of Igh rearrangements. LncRNA expression at the Igh locus was greatly diminished in DP thymocytes compared to that found in pro-B cells demonstrating lineage specificity (Supplementary Data Sheets 3–5) (Table 2). Furthermore, the Igh locus was split into several windows indicating a loss of window contiguity and underscoring the greatly diminished lncRNA expression at this locus in DP thymocytes (Tables 1, 2). These findings highlight a correlation between Igh locus activation and lncRNA expression in lymphocytes.

3.1.1 LncRNA expression at AgR loci is linked to V(D)J potential

To explore the proposition that elevated lncRNA expression may be a general feature of AgR loci engaged in V(D)J recombination we examined TCR loci in DP thymocytes and in B cell progenitors for lncRNA transcripts. RAG1/2 recombinase is first expressed in double negative (DN) CD4-CD8- thymocytes whereupon the Tcrg, Tcrd and Tcrb all undergo recombination (53, 54). Tcrb recombination facilitates assembly of the pre-TCR containing a rearranged β gene, commitment to the αβ T-cell lineage and differentiation into the DP stage of development (55). The Tcra locus is capable of V(D)J rearrangement in DP TCRβ Tg+ thymocytes (56). Using three independent RNA-seq data sets we examined lncRNA expression in DP CD3 stimulated thymocytes and in thymocytes expressing the TCRβ Tg. The large Tcrad locus achieved overall window scores of 2, 19 and 34 for lncRNA expression and was encompassed in single large windows (Table 2). In contrast, the Tcrad locus was ranked 220 overall and was split into several windows in pro-B cells where it does not recombine (Table 1). These observations suggest that elevated expression of lncRNA transcripts is a feature of AgR loci capable of engaging in V(D)J recombination. We conclude that expression of novel lncRNAs is elevated in AgR loci and correlated with V(D)J recombination potential in a lineage specific fashion.

3.1.2 Igh locus contraction is not required for elevated lncRNA expression

Igh locus contraction facilitates distal VH gene usage during V->DJ recombination and is dependent on expression of the B lineage determining TFs, PAX5 and YY1 (20, 57). In the absence of locus contraction only VH genes in close proximity to the recombination center located in the Eμ-D-J cluster engage in V->DJ recombination whereas VH segments at more distal positions remain unrearranged (58). Locus contraction may also influence gene expression by providing VH and lncRNA exons access to distal Igh enhancers spanning the locus (45). To test the proposition that elevated lncRNA expression requires locus contraction we evaluated RNA-seq data sets from Rag1-/-YY1-/- pro-B cells (Supplementary Data Sheet 6) (41). In this case, the Igh locus coalesced into a single window and achieved an overall window score of 6 suggesting that failure to undergo robust locus contraction does not significantly impair locus affiliated lncRNA expression and implies that lncRNA expression does not require proximity to Eμ (Table 1).

3.2 Igh associated lncRNAs are both mono- and multi-exonic

Numerous Igh associated noncoding (nc) RNAs are detected in Rag1-/- pro-B cells when no minimum length requirement is applied (Supplementary Data Sheet 7). Characterization of Igh associated lncRNAs (>300 nt) indicates that most are mono-exonic (218/242) and are arrayed in both the sense (120/218) and antisense (98/218) orientations with little overlap (Supplementary Data Sheet 7). In contrast, most multi-exonic lncRNAs (24/242) are in the antisense orientation (20/24) (Supplementary Data Sheet 7). Ample evidence indicates that some lncRNAs direct chromatin remodeling complexes to specific genes and regulate pluripotency, neurogenesis and brain development (59–64). Therefore, we asked whether lncRNAs overlap with- or are in proximity (within 500 bp) to-VH genes and thereby influence VH usage during V(D)J recombination. We first considered VH-lncRNA overlap, as this configuration is most likely to influence chromatin accessibility. We find that 144/180 VH are used in V(D)J recombination (45). However, only 40/180 VH genes overlap with lncRNAs and of these 32/144 are used in V(D)J recombination indicating no overall correlation between VH-lncRNA overlap with VH gene usage. Nevertheless, those minority VH genes overlapped with lncRNAs are predisposed for usage in recombination. Additionally, no correlation was found between lncRNA proximity within 500 bp of VH genes leading to VH usage in V->DJ recombination leaving open the question of lncRNA function in the Igh locus.

3.3 Multi-exonic lncRNAs cluster to Igh architectural anchors and enhancers

NcRNAs often colocalize with structural elements within TADs (reviewed in (30, 65). We examined Hi-C datasets from Rag2-/- pro-B cells to explore the relationship of Igh locus conformation with lncRNAs. Rag deficiency ensures that the Igh locus remains in a germline configuration and is comparable to other cell types. Hi-C difference maps were constructed by subtracting mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) from Rag2-/- contacts to identify pro-B specific interactions (12, 45). The Hi-C difference map for Rag2-/- pro-B cells shows a subTAD structure that is essentially identical to that found in Rag1-/- pro-B cells indicating a high degree of reproducibility (Figure 1B) (45). The Igh TAD is structurally divided into three subTADs and two additional mini-subTADs A.1 and B.1 that are anchored at Eμ, IGCR1, Sites I, II, II.5, III, Friend of Site Ia (FrOStIa) and FrOStIb and distal VH enhancers (Supplementary Figures 1A, B) (12, 45). Seven Igh enhancers include three at the 3’ end (3’Eα, Eγ and Eμ) and four VH distal enhancers (EVH1-4) (45). EVH1 and EVH2 are located within FrOStIa and FrOStIb, respectively (Figure 1A) (Supplementary Figure 1). EVH3.1 marks the boundary between the clustered and interspersed VHJ558 family genes and EVH4 is adjacent to Pax5-activated intergenic repeats (PAIR) 4 (Figure 1A). PAIR comprise a series of fourteen elements located in subTAD C that bind TF PAX5, E2A, and CTCF in pro-B cells (66, 67). PAIR6 and PAIR 11 co-locate with Sites II.5 and III, respectively (Figure 1A)(Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 1. Igh multi-exonic lncRNAs focus to architectural loop anchors. Genomic coordinates, mm10. (A) Diagram of the Igh locus. Regulatory elements shown are annotated on the HiC heatmap below. (B) Hi-C difference heatmap (chr12:113220000-116010000)(10kb resolution) with regulatory elements (colored dots) from Rag2-/- pro-B cells (n=2). DNA elements (3’Eα, red dot; CBEs, purple arrows; Eγ, teal dot; Eµ, gray oval; EVH1 (chr12:114182400-114183200), EVH2 (chr12:114609100-114609900), EVH3 (chr12:115023400-115024300), EVH4 (chr12:115257500-115258400); CH region genes (green bars); DH and JH exons (black bars); selected VH genes. Annotated lncRNAs are arrayed below the Hi-C heatmap and clusters i-v highlighted. (C) Igh enhancer-promoter hub. Virtual 4C interactions (mm10) were extracted from KR normalized Hi-C data sets from Rag2-/- pro-B cells (black lines) and murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEF) (blue lines). Top: Genomic coordinates with EVH1 and Sites (S) I, II, II.5 and III. EVH1 4C anchor (dashed vertical line) in a 30 kb running window analysis with 10 kb steps from merged biological replicates with EVH1 interactions (black arcs). Stars (top 15%) of locus-wide interactions. Putative distal enhancer (red arrow). Upper panel: EVH1 viewpoint. Lower panel: Eμ viewpoint. (D) Putative distal enhancer, termed EVH3.2 characterized for histone modifications, Pol II co-activators and TF binding in ChIP-seq assays and lncRNA expression derived from RNA-seq analyses.

The Hi-C difference heatmaps from Rag2-/- pro-B cells reveal asymmetric architectural stripes (blue arrowheads) and dots (black circles) representing loop domains that combine to define the conformational state of the Igh TAD (Figure 1B) (45). Stripes originating from 3’Eα, IGCR1 and from EVH1 are particularly evident (Figure 1B). Topological stripes are generated by loop extrusion when one subunit of dimeric cohesin stalls while the second subunit proceeds along chromatin in an ATP dependent fashion to form multiple contacts (14, 16, 17, 68). In addition to distinct chromatin loops visualized as dots (black circles), loops can also be folded into domains containing a plethora of intra-loop contacts (black arrows) such as found between Site I (S.I)-EVH1, EVH1-VHJ606 (a VH subfamily), and VHJ606-EVH2, EVH2-S.II, S.II-EVH3.1, EVH3.1-EVH4/PAIR4, and EVH4/PAIR4-PAIR6/SII.5 and that structure the locus (Figure 1B). Igh associated lncRNAs are arrayed below the Hi-C map to highlight the disposition of architectural elements with lncRNA expression in cis (Figure 1B). Five prominent clusters of mono-exonic and spliced lncRNAs are evident including those that span from Cγ2b and Eγ through Eμ and the DH-JH segments (cluster i), VHJ606 gene family (cluster ii), S.II (cluster iii), PAIR4-PAIR6 (S.II.5) (cluster iv) and PAIR11 (cluster v) and highlight a remarkable correlation between major Igh architectural elements and nested lncRNA positions (Figure 1B).

3.3.1 VH distal enhancers and PAIR elements participate in an enhancer interactome

Our earlier studies in the Rag1-/- genetic background demonstrated the presence of an Igh enhancer hub (45) that is thought to help balance dynamic transcription (69). Deletion of EVH1 was found to alter the composition of the enhancer interactome as well as to reduce VH gene usage in a defined chromatin domain (45). Here virtual 4C analyses were used to visualize Eμ and EVH1 centered chromatin contacts over long genomic distances and to further assess the relationship of these enhancers with lncRNA expression in Rag2-/- pro-B cells. High frequency interactions defined as the top 15 (star) percent of all contacts anchored at EVH1 and Eμ in both biological replicates for Rag2-/- (black symbols) pro-B cells were identified (Figure 1C). Virtual 4C contact maps indicate that the EVH1 viewpoint interacts with Eμ and the distal enhancers, EVH2, EVH3.1, EVH4 in Rag2-/- pro-B cells (black trace) and are absent in MEF (blue trace) and a similar contact profile was detected for the Eμ viewpoint indicating pro-B cell specificity (Figure 1C). Both EVH1 and Eμ interact with a new element (red arrow) which we term EVH3.2 (see below) in Rag2-/- pro-B cells and not in MEF (Figures 1C, D). Earlier DNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) studies detected Eμ-EVH1-EVH2 interactions directly demonstrating the presence of a multi-way enhancer hub (45). The Igh enhancer interactome may serve to stabilize locus contraction by virtue of E-E-E interactions generated through cohesin mediated loop extrusion.

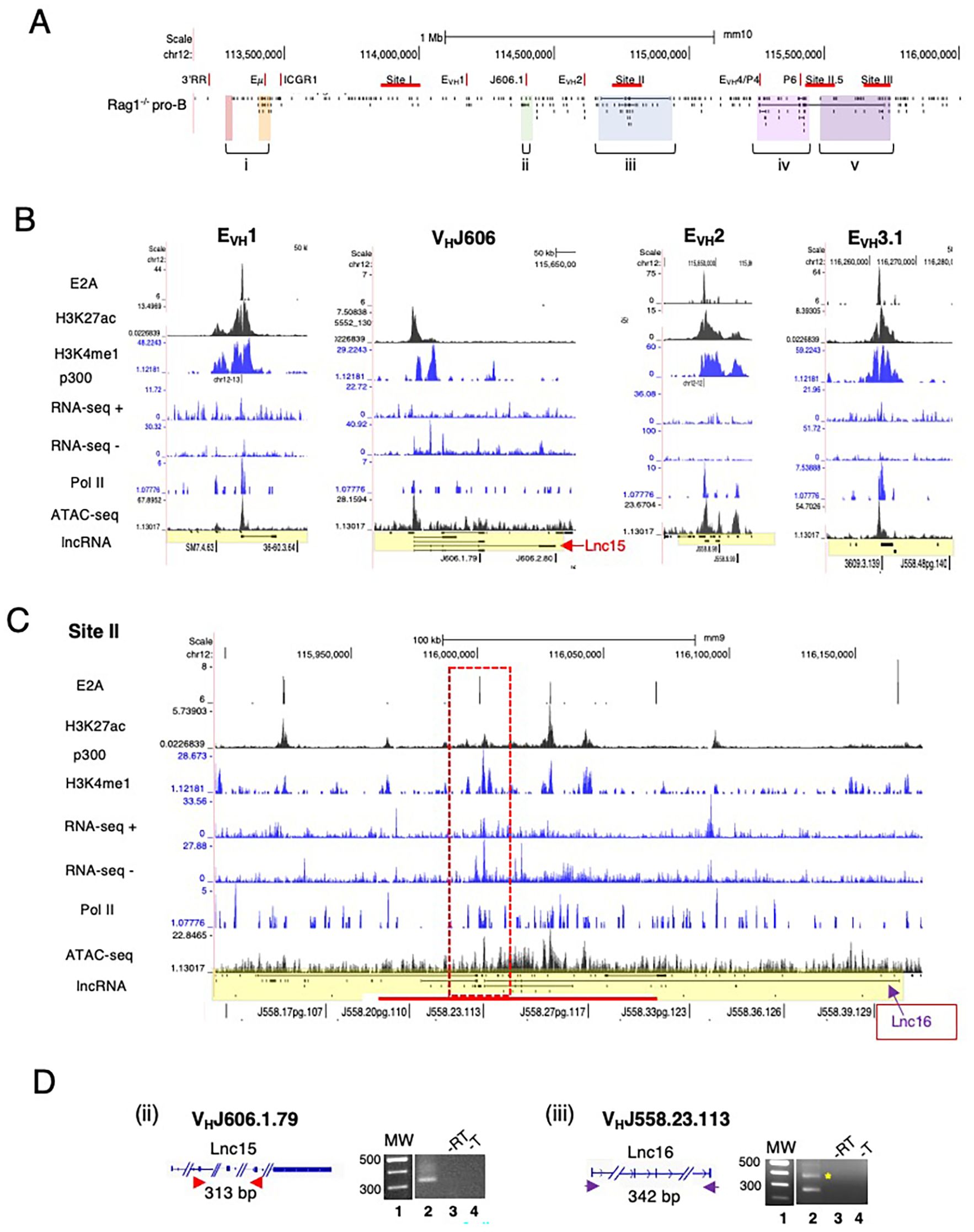

3.3.2 Spliced lncRNAs are expressed from Igh enhancers and a subset of VH promoters

To better appreciate the positional specificity of the multi-exonic lncRNA clusters we visualized these regions at high resolution using the UCSC Genome browser and provided an overall locus schematic for reference (Figure 2A). We observe that nearly all spliced lncRNAs are located at positions marked with H3K4me1 and H3K27ac which in combination is often indicative of active enhancer elements (70, 71). We performed ATAC-seq assays on Rag2-/- pro-B cells to assess degrees of chromatin accessibility genome-wide. ATAC-seq signals indicate that multi-exonic lncRNAs TSSs are hyper-accessible in the Igh locus (Figures 2B, C, 3B). We find that essentially all spliced and some mono-exonic lncRNAs are localized to Igh enhancers (Eγ, Eμ, EVH1, EVH2, EVH3.1, EVH3.2, EVH4) and occasionally at VH promoters (Figures 2B, 3A, B) (Supplementary Figures 2A, B). EVH3.2 and EVH4 exhibit an additional characteristic as they overlap with VH promoters; VH8-6 (VH3609.5.147) adjacent to PAIR2, and VH8.7 (VH3609.6pg.151) near PAIR4, respectively (Figure 1D) (45). EVH3.1 is coincident with the TSS of a mono-exonic lncRNA that fully overlaps VH8-4 (VH3609.3.139). Spliced and nested lncRNAs also locate with other VH promoters including VH6-3 (VHJ606.1.79) and in S.II centered on VH1-23 (VHJ558.23.113) (Figures 2B, C). High-throughput sequencing assays for enhancer activity have detected enhancer-like promoters that are located proximal to or overlapping with core promoters (72–74), anchor chromatin loops and function as bona fide enhancers (75). Our analyses highlight a convergence of lncRNAs with Igh enhancers and a subset of VH promoters that harbor enhancer-like features.

Figure 2. Spliced lncRNA are expressed from Igh enhancers and VH promoters. (A) Schematic of the Igh locus shown with mono- and mutli-exonic lncRNAs arrayed below the map. (B, C) Multi-exonic lncRNAs in subTAD B (EVH1, VHJ606.1.79 (V6-3), EVH2) and in Site II VHJ558.23.113 (V1-23) of subTAD C are shown with lanes from ChIP-seq and RNA-seq, all from Rag deficient pro-B cells (UCSC browser mm9). (D) RT-PCR assays were performed. CDNA were derived from Rag2-/- pro-B cells. MW 100bp ladder, no reverse transcriptase (-RT), no template (-T). Amplicons are diagrammatically indicated for each lncRNA. The predicted amplicon in panel iii is marked by the asterisk.

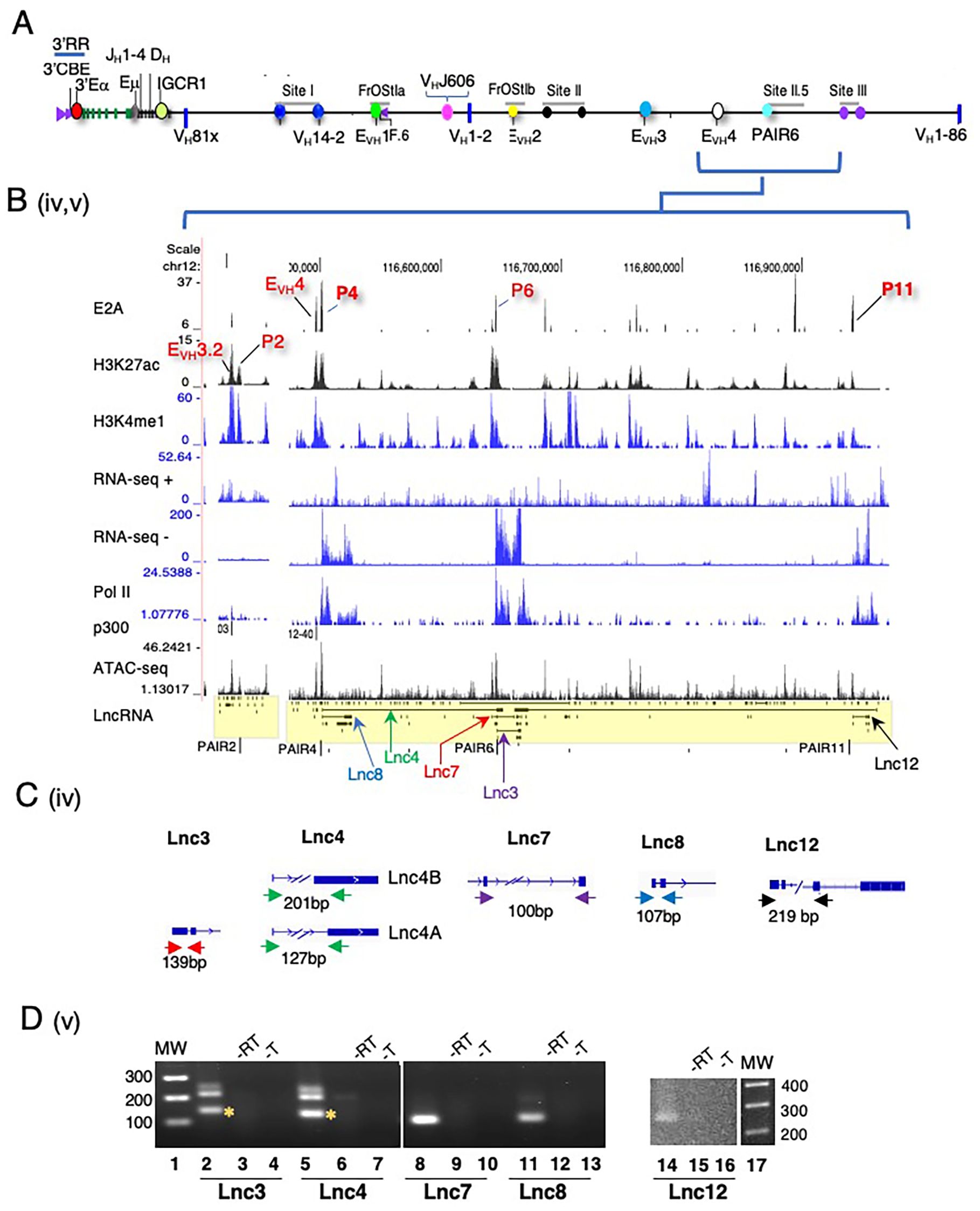

Figure 3. Multi-exonic lncRNA transcripts span the PAIR2-PAIR4-PAIR6-PAIR11 regions. (A) Schematic of the Igh locus. (B) Newly annotated multi-exonic lncRNAs centered on PAIR2, EVH4/PAIR4, PAIR6 at Site II.5 and PAIR11 at Site III are shown with lanes from ChIP-seq and RNA-seq from Rag deficient pro-B cells (UCSC browser mm9). (C) Amplicons are diagrammatically indicated for each lncRNA. (D) RT-PCR assays were performed. CDNA was synthesized using oligo dT and derived from Rag2-/- pro-B cells. MW 100bp ladder, no reverse transcriptase (-RT), no template (-T). The predicted amplicon is marked by an asterisk.

3.3.3 Spliced lncRNAs are actively transcribed in pro-B cells

We analyzed normalized expression (TPM) of mono-exonic and multi-exonic lncRNAs and found that many multi-exonic lncRNAs were expressed at levels significantly higher than for mono-exonic lncRNAs, (Supplementary Figure 2C). We verified expression of nine Igh associated multi-exonic lncRNAs (TPM >1.0) beginning with transcripts in the CH domain including Cμ, μ0 (lnc1), Cγ2b, γ2b GLT (lnc9) in Rag2-/- pro-B cells (Supplementary Figure 2D) (Supplementary Table 1). The novel multi-exonic lncRNAs, lnc15, from cluster ii (VH6-3, VHJ606.1.79) and lnc16 in cluster iii (VH1-23, VHJ558.23.113) were also confirmed (Figure 2D). The robust pattern of RNA-seq minus strand signals and Pol II binding at PAIR4, PAIR6 and PAIR11 closely corresponds with the exon layout for lnc8, lnc7 and lnc12 suggesting active transcription (Figures 3A, B).

LncRNAs are often expressed as RNA isoforms which are produced via alternative transcription start and poly(A) sites and by alternative splicing (76, 77) resulting in varied transcripts (78). Many of the Igh associated multi-exonic lncRNAs are nested and appear to originate from alternative transcription starts and/or from alternative splicing (Figures 2A, B, 3B). Using polyA+ RNA for cDNA synthesis we demonstrate here that lnc3, lnc4, lnc7, lnc8 and lnc12 are polyadenylated in RT-PCR assays of pro-B cells (Figures 3C, D). LncRNAs lnc4 and lnc8, are splice variants located at PAIR4 and initiate from a single TSS (Figures 3C, D). The additional PCR product found for lnc4 originates from an overlapping mono-exonic transcript. Polyadenylation of lnc8 originating from PAIR4 was previously shown (66). PAIR6 associated lnc3 and lnc7 are isoforms with different TSSs and lnc12 is located at PAIR11 (Figures 3C, D). The primers for Lnc3 amplification overlap with a mono-exonic lncRNA and PCR generates two products, one 127bp (indicated by the asterisk) and a second larger product (Figure 3D). Lnc7 initiates downstream of VH8-8-1 (VH3609.8pg.160) and completely overlaps this gene whereas lnc3 initiates at PAIR6. Our studies have confirmed the expression of several newly Igh associated nested lncRNA transcripts.

3.4 Site II anchors long range interactions with other Igh structural elements

To examine the relationship of lncRNA expression with chromatin loop anchors in greater detail we analyzed S.II for Igh looping interactions in 3C assays. The spatial organization of Igh subTADs A and B is sculpted in part by interactions between the S.I VH14–2 promoter with Eμ, and with FrOStIa EVH1 and F.6 (Supplementary Figure 1) (45). VH14–2 is the most highly transcribed VH gene in the locus (4, 5) and is located on the S.I.3 3C fragment (45). EVH1 is a modulator of regional VH transcription and gene usage during V->DJ recombination and is a structural anchor of subTAD B (45). F.6 is bound by CTCF, is located ~15 kb upstream of EVH1 and interacts with VH14-2 (Figure 4A) (45). Using anchor probes S.I.3 and F.6 located in subTADs A and B, respectively, we characterized points of chromatin contact at S.II in chromatin from Rag2-/- pro-B cells, the Abelson transformed (Abl-t) pro-B cell line, 445.3, and ConA activated splenic T cells (Figure 4A). We anticipated that long range contacts between S.II and interaction partners in subTADs A and B, will occur in Rag2-/- pro-B cells which engage in robust Igh locus contraction, less in Abl-t 445.3 pro-B-cells that are partially deficient in locus contraction and will be absent in T cells (21, 58). To facilitate detection of extremely long-range contacts 3C chimeric fragments underwent a pre-amplification PCR step which was then used to program 3C assays.

Figure 4. Identification of Site II loop anchors locations. (A) Schematic of the Igh locus with genomic coordinates (chr12, mm10) the directionality of which follows chromosome showing DNA elements (CBEs, purple arrows, EVH1, EVH2, EVH3, EVH4 (red ovals). 3C primer sites are indicated for Site I and FrOStIa (middle panel). Site II is expanded, 3C Hind III fragments are delineated (vertical teal lines) and primer sites named (bottom panel). 3C fragments IIa, IIa.d and IIa.e and the lncRNAs that reside within them are marked by asterisks. (B-D) 3C assays. Arcs (3C assays), primers are identified below the graphs, 3C probes (anchor symbol). Average crosslinking frequencies are from independent chromatin samples as indicated. Statistical comparisons are to T cells. P values from two-tail Student’s t test and SEMs are shown. (B, C) 3C assays analyzing Site II anchored at Site I.3 (B) and FrOStIa F.6 CBE (C). Chromatin samples for Abl-t 445.3.11 line, n=3; Rag2-/- pro-B cells, n=3; T cells: n=3. (D) 3C assays analyzing Site I and FrOStIa anchored at Site II (D). Chromatin samples for Abl-t 445.3.11line, n=3; Rag2-/- pro-B cells, n=3; T cells: n=3.

Several points of statistically significant chromatin contact were detected for the S.I.3 and F.6 anchor probes with S.II in Rag2-/- pro-B cells but not in the 445.3 cell line or in splenic T cells indicating that these interactions depend on locus contraction (Figures 4B, C). S.I.3 and F.6 anchors prominently and reproducibly interact with fragments S.IIa and S.IIa.b and more sporadically with other fragments throughout this region (Figures 4B, C). S.II fragments IIa, IIa.d and IIa.e contain the TSSs and/or termination points of four nested lncRNAs (marked by red, green and purple asterisks), including lnc16, that is centered on V1-23 (VHJ558.23.113) (Figures 2C, 4A lower panel). Next, we assessed the S.IIa anchor contacts with S.I and FrOStIa and found a series of statistically significant interactions across these regions that were robustly present in in Rag2-/- pro-B cells, absent in splenic T cells and present at low levels in the 445.3 pro-B cell line highlighting the importance of locus contraction for formation of very long-range contacts (Figure 4D). The S.IIa probe contact patterns were particularly robust for S.I.2 and S.I.3, and FrOStIa F.3 (EVH1) and F.6, in pro-B cells recapitulating earlier studies identifying these sites as major loop tethers (Figure 4D) (45). We conclude that S.II anchors long range interactions at positions coincident with multi-exonic lncRNA expression. We note that lncRNAs are also expressed at EVH1 and within the SI.3 3C fragment. Thus, lncRNAs are positionally correlated with chromatin loop anchors that support locus topology. A limitation of our study is that analysis of mutations that would define the precise lncRNA gene elements required for chromatin loop function has not yet been carried out. Nevertheless, the correlation of lncRNA position with chromatin anchors is tight.

4 Discussion

LncRNAs are diverse transcriptional products emerging from thousands of loci with numerous functions and the potential to regulate gene expression at varying distances from their targets (reviewed in (30–32, 79)). Antisense intergenic and genic transcripts in the VH domain of the Igh locus were previously detected and their expression was concomitant with V->DJ recombination in pro-B cells (80). More recently the involvement of lncRNAs was shown in early B cell development, V(D)J recombination and class switch recombination (CSR) (37, 38). Our interrogation of unannotated sense and antisense transcripts (>300nt) genome-wide revealed a remarkable enrichment of previously unannotated lncRNAs in the Igh locus of pro-B cells and high cell specific expression in AgR loci that is correlated with the onset of V(D)J recombination. We find that Igh associated lncRNAs are far more pervasive than originally contemplated. Multi-exonic lncRNAs are focused to Igh enhancers, a subset of VH promoters with enhancer-like features and which appear to function as chromatin loop anchors that define locus topology.

Two forms of transcription products originating from enhancers have been detected, enhancer RNAs (eRNAs) and lncRNAs. Active enhancers display characteristic chromatin marks including H3K37ac, H3K4me1, bind CBP/p300, coincide with DNase hypersensitive sites (81) and exhibit extensive transcription leading to the production of eRNAs which are typically short, unstable, non-polyadenylated and unspliced (82–86). RNAPII binding and bidirectional eRNA expression are now considered hallmarks of active enhancers (84, 85). Unlike eRNA, lncRNAs are generally stable, spliced and polyadenylated (85, 87) as are many Igh associated multi-exonic transcripts. Enhancers containing conserved, directional splicing signals that promote lncRNA production often exhibit elevated activity and implicate lncRNA processing as a factor determining enhancer function (88). Genomewide annotation studies have shown that 30-60% of lncRNAs are transcribed from positions with characteristic enhancer features (85, 89). Notably, Igh associated spliced lncRNAs are overlapping with or immediately adjacent to seven Igh enhancers (Eγ, Eμ, EVH1, EVH2, EVH3.1, EVH3.2, EVH4) which also anchor loop domains. Comparative studies indicate that lncRNA associated enhancers comprise a subgroup with stronger enhancer activity than those unaffiliated with lncRNAs (88) implying that Igh enhancers operate at an elevated activity level. Interestingly, recent studies reported that splicing of coding and noncoding RNA transcripts could increase expression of nearby genes (72, 90). Extrapolation of these findings to the Igh locus suggests that expression of lncRNAs could influence nearby VH gene expression and perhaps their usage in V(D)J recombination.

Multi-exonic lncRNA genes are also associated with a subset of VH genes including VH6–3 in subTAD B and at S.II centered on VH1–23 which exhibit elevated chromatin accessibility and H3K4me1 and H3K27ac marks, an epigenetic signature of enhancers. The distal enhancers EVH3.1, EVH3.2 and EVH4 are co-located with VH promoters and all overlap lncRNAs. Accordingly, enhancer activity has been detected at a subgroup of promoters with enhancer-like characteristics that are positioned at or near core promoters (72–74), and function as bona fide enhancers and chromatin loop anchors (75). Our chromosome conformation capture studies presented here and in earlier work (45) have shown that the Igh enhancers and enhancer-like promoters are configured in a long-range multiway hub that contributes to locus conformation and is topologically linked with Eμ (45). Deletion of EVH1, an enhancer hub constituent, led to altered locus topology and regional loss of VH gene transcription and reduced VH usage in V->DJ recombination (45). Our findings indicate that a subset of Igh associated lncRNAs are embedded in an enhancer cluster with likely importance to locus function. Our findings raise the question of how lncRNA expression might influence genome architecture. Accordingly, studies indicate that lncRNAs can influence chromatin function and regulate membraneless nuclear bodies, for example (91).

Genome folding is catalyzed through cohesin mediated loop extrusion, a major contributor toward shaping the spatial organization of the genome (16, 17, 19, 28, 92–95). Cohesin maintains TADs by progressively extruding DNA loops until it becomes encumbered by an obstacle which halts movement and anchors DNA loops in mammalian cells (16, 17). The loop extrusion model explains how Es can processively track arrays of Prs that are separated by long genomic intervals (16, 17, 96). Loop extrusion can be blocked by chromatin binding proteins leading to the generation of cohesin dependent loops.

CTCF is the most prominent loop extrusion barrier (28, 94, 95) and RNAPII and R-loops play similar roles at active promoters (97, 98). For example, RNAPII depletion leads to the establishment of longer chromatin loops (99) and reorganization of contacts between cohesin mediated CTCF anchored loops (100) indicating a dynamic relationship of RNAPII with loop extrusion. The Igh VH domain contains 144 CTCF binding elements (CBEs) that are occupied by CTCF in pro-B cells (8, 101) implying a substantial role for CTCF in specifying locus structure. Indeed, deregulation of CBE impediments in primary pro-B cells promotes V(D)J recombination mediated by loop extrusion (23). Likewise, RNAP II can directly tether chromatin loops (100, 102) and contribute to cohesin pausing (103, 104). Exuberant expression of lncRNAs in the Igh locus of pro-B cells and the pile-up of both mono- and multi-exonic lncRNAs at loop anchors implies that clustered RNAPII binding may cumulatively impede cohesin mediated loop extrusion and create logjams leading to emergence of major loop anchors.

VH gene families are clustered in the locus (3) and display distinct epigenetic signatures defined by histone modifications, RNAPII and TF binding (4, 5) and the position of bound CTCF (7, 8). Clustering of Igh associated lncRNA genes will produce foci of RNAPII binding which could obstruct loop extrusion as has been found in other loci (98). We propose that the dynamic interplay of loop extrusion with its barriers, CTCF, and RNAPII including those loaded at lncRNA promoters may modulate the contact probability of VH genes with the recombination center and influence VH gene usage during recombination.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material.

Ethics statement

The animal study was approved by Institutional Animal Care Committee of the University of Illinois College of Medicin. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

Author contributions

ED: Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Investigation, Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Visualization. SN: Formal analysis, Visualization, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. XQ: Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. KB: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. HF: Visualization, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. MM-C: Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis. JL: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. AK: Supervision, Writing – review & editing, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Project administration.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by grants from the NIH to AK. (R01AI121286, R01AI177507). These NIH grants provided salary support and resources to perform this research.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. A. Koh for normalizing the ATAC-seq data and M.T. Khan helpful discussions.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1678105/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Teng G and Schatz DG. Regulation and evolution of the rag recombinase. Adv Immunol. (2015) 128:1–39. doi: 10.1016/bs.ai.2015.07.002

2. Bassing CH, Swat W, and Alt FW. The mechanism and regulation of chromosomal V(D)J recombination. Cell. (2002) 109 Suppl:S45–55. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00675-x

3. Chevillard C, Ozaki J, Herring CD, and Riblet R. A three-megabase yeast artificial chromosome contig spanning the C57bl mouse igh locus. J Immunol. (2002) 168:5659–66. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5659

4. Choi NM, Loguercio S, Verma-Gaur J, Degner SC, Torkamani A, Su AI, et al. Deep sequencing of the murine igh repertoire reveals complex regulation of nonrandom V gene rearrangement frequencies. J Immunol. (2013) 191:2393–402. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301279

5. Bolland DJ, Koohy H, Wood AL, Matheson LS, Krueger F, Stubbington MJ, et al. Two mutually exclusive local chromatin states drive efficient V(D)J recombination. Cell Rep. (2016) 15:2475–87. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.05.020

6. Kleiman E, Loguercio S, and Feeney AJ. Epigenetic enhancer marks and transcription factor binding influence vkappa gene rearrangement in pre-B cells and pro-B cells. Front Immunol. (2018) 9:2074. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02074

7. Degner SC, Verma-Gaur J, Wong TP, Bossen C, Iverson GM, Torkamani A, et al. Ccctc-binding factor (Ctcf) and cohesin influence the genomic architecture of the igh locus and antisense transcription in pro-B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2011) 108:9566–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019391108

8. Degner SC, Wong TP, Jankevicius G, and Feeney AJ. Cutting edge: developmental stage-specific recruitment of cohesin to ctcf sites throughout immunoglobulin loci during B lymphocyte development. J Immunol. (2009) 182:44–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.44

9. Dixon JR, Selvaraj S, Yue F, Kim A, Li Y, Shen Y, et al. Topological domains in mammalian genomes identified by analysis of chromatin interactions. Nature. (2012) 485:376–80. doi: 10.1038/nature11082

10. Sexton T, Yaffe E, Kenigsberg E, Bantignies F, Leblanc B, Hoichman M, et al. Three-dimensional folding and functional organization principles of the drosophila genome. Cell. (2012) 148:458–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.010

11. Nora EP, Lajoie BR, Schulz EG, Giorgetti L, Okamoto I, Servant N, et al. Spatial partitioning of the regulatory landscape of the X-inactivation centre. Nature. (2012) 485:381–5. doi: 10.1038/nature11049

12. Montefiori L, Wuerffel R, Roqueiro D, Lajoie B, Guo C, Gerasimova T, et al. Extremely long-range chromatin loops link topological domains to facilitate a diverse antibody repertoire. Cell Rep. (2016) 14:896–906. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.12.083

13. Benner C, Isoda T, and Murre C. New roles for DNA cytosine modification, erna, anchors, and superanchors in developing B cell progenitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2015) 112:12776–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1512995112

14. Rao SS, Huntley MH, Durand NC, Stamenova EK, Bochkov ID, Robinson JT, et al. A 3d map of the human genome at kilobase resolution reveals principles of chromatin looping. Cell. (2014) 159:1665–80. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.021

15. Rowley MJ and Corces VG. Organizational principles of 3d genome architecture. Nat Rev Genet. (2018) 19:789–800. doi: 10.1038/s41576-018-0060-8

16. Sanborn AL, Rao SS, Huang SC, Durand NC, Huntley MH, Jewett AI, et al. Chromatin extrusion explains key features of loop and domain formation in wild-type and engineered genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2015) 112:E6456–65. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518552112

17. Fudenberg G, Imakaev M, Lu C, Goloborodko A, Abdennur N, and Mirny LA. Formation of chromosomal domains by loop extrusion. Cell Rep. (2016) 15:2038–49. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.04.085

18. Banigan EJ and Mirny LA. Loop extrusion: theory meets single-molecule experiments. Curr Opin Cell Biol. (2020) 64:124–38. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2020.04.011

19. Yatskevich S, Rhodes J, and Nasmyth K. Organization of chromosomal DNA by smc complexes. Annu Rev Genet. (2019) 53:445–82. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-112618-043633

20. Fuxa M, Skok J, Souabni A, Salvagiotto G, Roldan E, and Busslinger M. Pax5 induces V-to-dj rearrangements and locus contraction of the immunoglobulin heavy-chain gene. Genes Dev. (2004) 18:411–22. doi: 10.1101/gad.291504

21. Kosak ST, Skok JA, Medina KL, Riblet R, Le Beau MM, Fisher AG, et al. Subnuclear compartmentalization of immunoglobulin loci during lymphocyte development. Science. (2002) 296:158–62. doi: 10.1126/science.1068768

22. Hill L, Ebert A, Jaritz M, Wutz G, Nagasaka K, Tagoh H, et al. Wapl repression by pax5 promotes V gene recombination by igh loop extrusion. Nature. (2020) 584:142–7. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2454-y

23. Dai HQ, Hu H, Lou J, Ye AY, Ba Z, Zhang X, et al. Loop extrusion mediates physiological igh locus contraction for rag scanning. Nature. (2021) 590:338–43. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-03121-7

24. Hesslein DG, Pflugh DL, Chowdhury D, Bothwell AL, Sen R, and Schatz DG. Pax5 is required for recombination of transcribed, acetylated, 5’ Igh V gene segments. Genes Dev. (2003) 17:37–42. doi: 10.1101/gad.1031403

25. Kenter AL, Priyadarshi S, and Drake EB. Locus architecture and rag scanning determine antibody diversity. Trends Immunol. (2023) 44:119–28. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2022.12.005

26. Lin SG, Ba Z, Alt FW, and Zhang Y. Rag chromatin scanning during V(D)J recombination and chromatin loop extrusion are related processes. Adv Immunol. (2018) 139:93–135. doi: 10.1016/bs.ai.2018.07.001

27. Dekker J and Mirny LA. The chromosome folding problem and how cells solve it. Cell. (2024) 187:6424–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2024.10.026

28. Li Y, Haarhuis JHI, Sedeno Cacciatore A, Oldenkamp R, van Ruiten MS, Willems L, et al. The structural basis for cohesin-ctcf-anchored loops. Nature. (2020) 578:472–6. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1910-z

29. Bolland DJ, Wood AL, Johnston CM, Bunting SF, Morgan G, Chakalova L, et al. Antisense intergenic transcription in V(D)J recombination. Nat Immunol. (2004) 5:630–7. doi: 10.1038/ni1068

30. Mattick JS, Amaral PP, Carninci P, Carpenter S, Chang HY, Chen LL, et al. Long non-coding rnas: definitions, functions, challenges and recommendations. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2023) 24:430–47. doi: 10.1038/s41580-022-00566-8

31. Ferrer J and Dimitrova N. Transcription regulation by long non-coding rnas: mechanisms and disease relevance. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2024) 25:396–415. doi: 10.1038/s41580-023-00694-9

32. Gil N and Ulitsky I. Regulation of gene expression by cis-acting long non-coding rnas. Nat Rev Genet. (2020) 21:102–17. doi: 10.1038/s41576-019-0184-5

33. Morrissy AS, Griffith M, and Marra MA. Extensive relationship between antisense transcription and alternative splicing in the human genome. Genome Res. (2011) 21:1203–12. doi: 10.1101/gr.113431.110

34. Romero-Barrios N, Legascue MF, Benhamed M, Ariel F, and Crespi M. Splicing regulation by long noncoding rnas. Nucleic Acids Res. (2018) 46:2169–84. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky095

35. Pisignano G and Ladomery M. Epigenetic regulation of alternative splicing: how lncrnas tailor the message. Noncoding RNA. (2021) 7(1):21. doi: 10.3390/ncrna7010021

36. Brazao TF, Johnson JS, Muller J, Heger A, Ponting CP, and Tybulewicz VL. Long noncoding rnas in B-cell development and activation. Blood. (2016) 128:e10–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-11-680843

37. Rothschild G, Zhang W, Lim J, Giri PK, Laffleur B, Chen Y, et al. Noncoding rna transcription alters chromosomal topology to promote isotype-specific class switch recombination. Sci Immunol. (2020) 5(44). doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aay5864

38. Laffleur B, Batista CR, Zhang W, Lim J, Yang B, Rossille D, et al. Rna exosome drives early B cell development via noncoding rna processing mechanisms. Sci Immunol. (2022) 7:eabn2738. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abn2738

39. Kumar S, Wuerffel R, Achour I, Lajoie B, Sen R, Dekker J, et al. Flexible ordering of antibody class switch and V(D)J joining during B-cell ontogeny. Genes Dev. (2013) 27:2439–44. doi: 10.1101/gad.227165.113

40. Verma-Gaur J, Torkamani A, Schaffer L, Head SR, Schork NJ, and Feeney AJ. Noncoding Transcription within the Igh Distal V(H) Region at Pair Elements Affects the 3d Structure of the Igh Locus in Pro-B Cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2012) 109:17004–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208398109

41. Kleiman E, Jia H, Loguercio S, Su AI, and Feeney AJ. Yy1 plays an essential role at all stages of B-cell differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2016) 113:E3911–20. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606297113

42. Teng G, Maman Y, Resch W, Kim M, Yamane A, Qian J, et al. Rag represents a widespread threat to the lymphocyte genome. Cell. (2015) 162:751–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.07.009

43. Smeenk L, Fischer M, Jurado S, Jaritz M, Azaryan A, Werner B, et al. Molecular role of the pax5-etv6 oncoprotein in promoting B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. EMBO J. (2017) 36:718–35. doi: 10.15252/embj.201695495

44. Lin YC, Jhunjhunwala S, Benner C, Heinz S, Welinder E, Mansson R, et al. A global network of transcription factors, involving E2a, ebf1 and foxo1, that orchestrates B cell fate. Nat Immunol. (2010) 11:635–43. doi: 10.1038/ni.1891

45. Bhat KH, Priyadarshi S, Naiyer S, Qu X, Farooq H, Kleiman E, et al. An igh distal enhancer modulates antigen receptor diversity by determining locus conformation. Nat Commun. (2023) 14:1225. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-36414-2

46. Durand NC, Shamim MS, Machol I, Rao SS, Huntley MH, Lander ES, et al. Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution hi-C experiments. Cell Syst. (2016) 3:95–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2016.07.002

47. Yang T, Zhang F, Yardimci GG, Song F, Hardison RC, Noble WS, et al. Hicrep: assessing the reproducibility of hi-C data using a stratum-adjusted correlation coefficient. Genome Res. (2017) 27:1939–49. doi: 10.1101/gr.220640.117

48. Wuerffel R, Wang L, Grigera F, Manis J, Selsing E, Perlot T, et al. S-S synapsis during class switch recombination is promoted by distantly located transcriptional elements and activation-induced deaminase. Immunity. (2007) 27:711–22. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.09.007

49. Feldman S, Wuerffel R, Achour I, Wang L, Carpenter PB, and Kenter AL. 53bp1 contributes to igh locus chromatin topology during class switch recombination. J Immunol. (2017) 198:2434–44. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601947

50. Feldman S, Achour I, Wuerffel R, Kumar S, Gerasimova T, Sen R, et al. Constraints contributed by chromatin looping limit recombination targeting during ig class switch recombination. J Immunol. (2015) 194:2380–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401170

51. Buenrostro JD, Wu B, Chang HY, and Greenleaf WJ. Atac-seq: A method for assaying chromatin accessibility genome-wide. Curr Protoc Mol Biol. (2015) 109:21 9 1– 9 9. doi: 10.1002/0471142727.mb2129s109

52. Corces MR, Granja JM, Shams S, Louie BH, Seoane JA, Zhou W, et al. The chromatin accessibility landscape of primary human cancers. Science. (2018) 362(6413). doi: 10.1126/science.aav1898

53. Capone M, Hockett RD Jr., and Zlotnik A. Kinetics of T cell receptor beta, gamma, and delta rearrangements during adult thymic development: T cell receptor rearrangements are present in cd44(+)Cd25(+) pro-T thymocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (1998) 95:12522–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12522

54. Hayday AC and Pennington DJ. Key factors in the organized chaos of early T cell development. Nat Immunol. (2007) 8:137–44. doi: 10.1038/ni1436

55. Krangel MS. Mechanics of T cell receptor gene rearrangement. Curr Opin Immunol. (2009) 21:133–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.03.009

56. Guidos CJ, Williams CJ, Wu GE, Paige CJ, and Danska JS. Development of cd4+Cd8+ Thymocytes in rag-deficient mice through a T cell receptor beta chain-independent pathway. J Exp Med. (1995) 181:1187–95. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.3.1187

57. Liu H, Schmidt-Supprian M, Shi Y, Hobeika E, Barteneva N, Jumaa H, et al. Yin yang 1 is a critical regulator of B-cell development. Genes Dev. (2007) 21:1179–89. doi: 10.1101/gad.1529307

58. Lee YN, Frugoni F, Dobbs K, Walter JE, Giliani S, Gennery AR, et al. A systematic analysis of recombination activity and genotype-phenotype correlation in human recombination-activating gene 1 deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. (2014) 133:1099–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.10.007

59. Ang CE, Ma Q, Wapinski OL, Fan S, Flynn RA, Lee QY, et al. The novel lncrna lnc-nr2f1 is pro-neurogenic and mutated in human neurodevelopmental disorders. Elife. (2019) 8. doi: 10.7554/eLife.41770

60. Cajigas I, Chakraborty A, Lynam M, Swyter KR, Bastidas M, Collens L, et al. Sox2-evf2 lncrna-mediated mechanisms of chromosome topological control in developing forebrain. Development. (2021) 148(6). doi: 10.1242/dev.197202

61. Hou L, Wei Y, Lin Y, Wang X, Lai Y, Yin M, et al. Concurrent binding to DNA and rna facilitates the pluripotency reprogramming activity of sox2. Nucleic Acids Res. (2020) 48:3869–87. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa067

62. Ng B, Avey DR, Lopes KP, Fujita M, Vialle RA, Vyas H, et al. Spatial expression of long non-coding rnas in human brains of alzheimer’s disease. bioRxiv. (2025). doi: 10.1101/2024.10.27.620550

63. Ng SY, Johnson R, and Stanton LW. Human long non-coding rnas promote pluripotency and neuronal differentiation by association with chromatin modifiers and transcription factors. EMBO J. (2012) 31:522–33. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.459

64. Samudyata, Amaral PP, Engstrom PG, Robson SC, Nielsen ML, Kouzarides T, et al. Interaction of sox2 with rna binding proteins in mouse embryonic stem cells. Exp Cell Res. (2019) 381:129–38. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2019.05.006

65. Khosraviani N, Ostrowski LA, and Mekhail K. Roles for non-coding rnas in spatial genome organization. Front Cell Dev Biol. (2019) 7:336. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2019.00336

66. Ebert A, McManus S, Tagoh H, Medvedovic J, Salvagiotto G, Novatchkova M, et al. The distal V(H) gene cluster of the igh locus contains distinct regulatory elements with pax5 transcription factor-dependent activity in pro-B cells. Immunity. (2011) 34:175–87. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.02.005

67. Hill L, Jaritz M, Tagoh H, Schindler K, Kostanova-Poliakova D, Sun Q, et al. Enhancers of the pair4 regulatory module promote distal V(H) gene recombination at the igh locus. EMBO J. (2023) 42:e112741. doi: 10.15252/embj.2022112741

68. Vian L, Pekowska A, Rao SSP, Kieffer-Kwon KR, Jung S, Baranello L, et al. The energetics and physiological impact of cohesin extrusion. Cell. (2018) 173:1165–78 e20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.072

69. Lim B and Levine MS. Enhancer-promoter communication: hubs or loops? Curr Opin Genet Dev. (2021) 67:5–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2020.10.001

70. Heintzman ND, Hon GC, Hawkins RD, Kheradpour P, Stark A, Harp LF, et al. Histone modifications at human enhancers reflect global cell-type-specific gene expression. Nature. (2009) 459:108–12. doi: 10.1038/nature07829

71. Creyghton MP, Cheng AW, Welstead GG, Kooistra T, Carey BW, Steine EJ, et al. Histone H3k27ac separates active from poised enhancers and predicts developmental state. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2011) 107:21931–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016071107

72. Engreitz JM, Haines JE, Perez EM, Munson G, Chen J, Kane M, et al. Local regulation of gene expression by lncrna promoters, transcription and splicing. Nature. (2016) 539:452–5. doi: 10.1038/nature20149

73. Kowalczyk MS, Hughes JR, Garrick D, Lynch MD, Sharpe JA, Sloane-Stanley JA, et al. Intragenic enhancers act as alternative promoters. Mol Cell. (2012) 45:447–58. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.12.021

74. Paralkar VR, Taborda CC, Huang P, Yao Y, Kossenkov AV, Prasad R, et al. Unlinking an lncrna from its associated cis element. Mol Cell. (2016) 62:104–10. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.02.029

75. Dao LTM, Galindo-Albarran AO, Castro-Mondragon JA, Andrieu-Soler C, Medina-Rivera A, Souaid C, et al. Genome-wide characterization of mammalian promoters with distal enhancer functions. Nat Genet. (2017) 49:1073–81. doi: 10.1038/ng.3884

76. Pan Q, Shai O, Lee LJ, Frey BJ, and Blencowe BJ. Deep surveying of alternative splicing complexity in the human transcriptome by high-throughput sequencing. Nat Genet. (2008) 40:1413–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.259

77. Harrow J, Denoeud F, Frankish A, Reymond A, Chen CK, Chrast J, et al. Gencode: producing a reference annotation for encode. Genome Biol. (2006) 7 Suppl 1:S4 1–9. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-s1-s4

78. Belchikov N, Hsu J, Li XJ, Jarroux J, Hu W, Joglekar A, et al. Understanding isoform expression by pairing long-read sequencing with single-cell and spatial transcriptomics. Genome Res. (2024) 34:1735–46. doi: 10.1101/gr.279640.124

79. Werner A, Kanhere A, Wahlestedt C, and Mattick JS. Natural antisense transcripts as versatile regulators of gene expression. Nat Rev Genet. (2024) 25:730–44. doi: 10.1038/s41576-024-00723-z

80. Bolland DJ, Wood AL, Afshar R, Featherstone K, Oltz EM, and Corcoran AE. Antisense intergenic transcription precedes igh D-to-J recombination and is controlled by the intronic enhancer emu. Mol Cell Biol. (2007) 27:5523–33. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02407-06

81. Calo E and Wysocka J. Modification of enhancer chromatin: what, how, and why? Mol Cell. (2013) 49:825–37. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.038

82. Koch F, Fenouil R, Gut M, Cauchy P, Albert TK, Zacarias-Cabeza J, et al. Transcription initiation platforms and gtf recruitment at tissue-specific enhancers and promoters. Nat Struct Mol Biol. (2011) 18:956–63. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2085

83. Li W, Notani D, and Rosenfeld MG. Enhancers as non-coding rna transcription units: recent insights and future perspectives. Nat Rev Genet. (2016) 17:207–23. doi: 10.1038/nrg.2016.4

84. Kim TK, Hemberg M, Gray JM, Costa AM, Bear DM, Wu J, et al. Widespread transcription at neuronal activity-regulated enhancers. Nature. (2010) 465:182–7. doi: 10.1038/nature09033

85. De Santa F, Barozzi I, Mietton F, Ghisletti S, Polletti S, Tusi BK, et al. A large fraction of extragenic rna pol ii transcription sites overlap enhancers. PloS Biol. (2010) 8:e1000384. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000384

86. Djebali S, Davis CA, Merkel A, Dobin A, Lassmann T, Mortazavi A, et al. Landscape of transcription in human cells. Nature. (2012) 489:101–8. doi: 10.1038/nature11233

87. Ulitsky I and Bartel DP. Lincrnas: genomics, evolution, and mechanisms. Cell. (2013) 154:26–46. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.020

88. Gil N and Ulitsky I. Production of spliced long noncoding rnas specifies regions with increased enhancer activity. Cell Syst. (2018) 7:537–47 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2018.10.009

89. Vucicevic D, Corradin O, Ntini E, Scacheri PC, and Orom UA. Long ncrna expression associates with tissue-specific enhancers. Cell Cycle. (2015) 14:253–60. doi: 10.4161/15384101.2014.977641

90. Tan JY, Biasini A, Young RS, and Marques AC. Splicing of enhancer-associated lincrnas contributes to enhancer activity. Life Sci Alliance. (2020) 3(4). doi: 10.26508/lsa.202000663

91. Statello L, Guo CJ, Chen LL, and Huarte M. Gene regulation by long non-coding rnas and its biological functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. (2021) 22:96–118. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-00315-9

92. Alipour E and Marko JF. Self-organization of domain structures by DNA-loop-extruding enzymes. Nucleic Acids Res. (2012) 40:11202–12. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks925

93. Haarhuis JHI, van der Weide RH, Blomen VA, Yanez-Cuna JO, Amendola M, van Ruiten MS, et al. The cohesin release factor wapl restricts chromatin loop extension. Cell. (2017) 169:693–707 e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.04.013

94. Nora EP, Caccianini L, Fudenberg G, So K, Kameswaran V, Nagle A, et al. Molecular basis of ctcf binding polarity in genome folding. Nat Commun. (2020) 11:5612. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19283-x

95. Pugacheva EM, Kubo N, Loukinov D, Tajmul M, Kang S, Kovalchuk AL, et al. Ctcf mediates chromatin looping via N-terminal domain-dependent cohesin retention. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2020) 117:2020–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1911708117

96. Dekker J and Mirny L. The 3d genome as moderator of chromosomal communication. Cell. (2016) 164:1110–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.007

97. Zhang H, Shi Z, Banigan EJ, Kim Y, Yu H, Bai XC, et al. Ctcf and R-loops are boundaries of cohesin-mediated DNA looping. Mol Cell. (2023) 83:2856–71 e8. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2023.07.006

98. Valton AL, Venev SV, Mair B, Khokhar ES, Tong AHY, Usaj M, et al. A cohesin traffic pattern genetically linked to gene regulation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. (2022) 29:1239–51. doi: 10.1038/s41594-022-00890-9

99. Zhang S, Ubelmesser N, Josipovic N, Forte G, Slotman JA, Chiang M, et al. Rna polymerase ii is required for spatial chromatin reorganization following exit from mitosis. Sci Adv. (2021) 7:eabg8205. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abg8205

100. Zhang S, Ubelmesser N, Barbieri M, and Papantonis A. Enhancer-promoter contact formation requires rnapii and antagonizes loop extrusion. Nat Genet. (2023) 55:832–40. doi: 10.1038/s41588-023-01364-4

101. Ciccone DN, Namiki Y, Chen C, Morshead KB, Wood AL, Johnston CM, et al. The murine igh locus contains a distinct DNA sequence motif for the chromatin regulatory factor ctcf. J Biol Chem. (2019) 294:13580–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.007348

102. Barshad G, Lewis JJ, Chivu AG, Abuhashem A, Krietenstein N, Rice EJ, et al. Rna polymerase ii dynamics shape enhancer-promoter interactions. Nat Genet. (2023) 55:1370–80. doi: 10.1038/s41588-023-01442-7

103. Banigan EJ, Tang W, van den Berg AA, Stocsits RR, Wutz G, Brandao HB, et al. Transcription shapes 3d chromatin organization by interacting with loop extrusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. (2023) 120:e2210480120. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2210480120

Keywords: progenitor B cells, V(D)J recombination, IgH locus, chromatin folding, long non-coding RNA

Citation: Drake EB, Naiyer S, Qu X, Bhat K, Farooq H, Maienschein-Cline M, Liang J and Kenter AL (2025) Exuberant long noncoding RNA expression may sculpt Igh locus topology. Front. Immunol. 16:1678105. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1678105

Received: 01 August 2025; Accepted: 21 October 2025;

Published: 24 November 2025.

Edited by:

Dinah S. Singer, National Cancer Institute (NIH), United StatesReviewed by:

Richard L. Frock, Stanford University, United StatesBrice Laffleur, INSERM UMR1236 Microenvironnement, Différenciation cellulaire, Immunologie et Cancer, France

Copyright © 2025 Drake, Naiyer, Qu, Bhat, Farooq, Maienschein-Cline, Liang and Kenter. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Amy L. Kenter, c3RhcjFAdWljLmVkdQ==

†Present addresses: Sarah Naiyer, Department of Biomedical Science, The University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, United States Xinyan Qu, Medpace, Cincinnati, OH, United States Khalid Bhat, SKUAST Kashmir, Division of Basic Science and Humanities, Faculty of Horticulture, Srinagar, India

Ellen B. Drake

Ellen B. Drake Sarah Naiyer

Sarah Naiyer Xinyan Qu1†

Xinyan Qu1† Jie Liang

Jie Liang Amy L. Kenter

Amy L. Kenter