- 1Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Graz, Graz, Austria

- 2AlgoNomics, Applied Protein Services, Lonza Biologics PLC, Cambridge, United Kingdom

- 3Antagonis Biotherapeutics GmbH, Graz, Austria

Introduction: Chronic inflammatory processes are characterized by the infiltration of chemokine-activated leukocytes into inflamed tissues. Chemokines interact with their respective G protein-coupled receptors (GPCR) on target immune cells as well as with glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), displayed as part of proteoglycans, on the surface of endothelial cells to exert their function. Excessive levels of CXCL8 are associated with several chronic inflammatory diseases, which are characterized by a rich neutrophil influx. The CXCL8-GAG axis therefore represents a new therapeutic route to target these diseases.

Methods: An anti-inflammatory CXCL8-based, dominant-negative mutant chemokine (termed dnCXCL8) with increased GAG binding affinity and knocked out GPCR activity, was generated and was proven to be active in various in vivo models in previous studies. To investigate the immunogenic potential of this dominant-negative mutant in comparison to its wild-type form, an in vitro T-cell activation study was performed.

Results: Both proteins induced immunogenic responses, with dnCXCL8 showing a slightly higher response than wild-type CXCL8. An increased number of responsive donors for the mutant was detected, but no significant differences were observed at the population level. Concerning protein-derived peptides, the mutant-derived ones showed an enhanced frequency of lymphocyte activation; however, the differences were not significant on the population level.

Discussion: This study provides first insights into the immunogenic potential of a chemokine-based drug candidate and paves the way for further optimization of chemokine-based therapy.

1 Introduction

Chemokines are a large class of small, mainly basic proteins with molecular weights ranging from 8–14 kDa (1). They play central roles in immune regulation, particularly in the coordination of leukocyte recruitment, activation, and migration during inflammatory and immune-mediated diseases (2). Structurally, all chemokines contain two or four conserved cysteine residues in their N-terminal regions that form characteristic disulfide bonds, which are required for their conformational stability and biological function (3). Based on the number and spacing of these cysteines, chemokines are divided into four families: CC, CXC, C, and CX3C, with the CC and CXC families representing the majority (4).

CXCL8, also known as interleukin-8 (IL-8), is a member of the CXC chemokine family and consists of 99 amino acids, including a 22-amino-acid signal peptide. After cleavage, two major isoforms (72 or 77 amino acids) are produced, with additional N-terminal processing yielding shorter variants. Importantly, chemotactic potency is inversely correlated with peptide length, with shorter isoforms exhibiting stronger activity (5–7). CXCL8 mediates multiple neutrophil functions, including chemotaxis, oxidative burst, granule enzyme release, and production of reactive oxygen species (8). These activities are initiated through binding to the G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) CXCR1 and CXCR2 with different affinities. CXCR1, initially described as CXCL8-selective, also recognizes CXCL6 as an agonist, whereas CXCR2 displays broader promiscuity, binding CXCL8 together with several other CXC chemokines (9, 10). Engagement of these receptors leads to neutrophil migration, angiogenesis, calcium mobilization, respiratory burst, and granule release, followed by receptor internalization, recycling, and resurfacing that sustain responsiveness (11, 12).

A key feature of chemokine biology is their interaction with glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), such as heparan sulfate and chondroitin sulfate. These negatively charged linear polysaccharides form proteoglycans upon attachment to core proteins and range in molecular weight from 10–100 kDa, dependent on the number of repeating disaccharide units (13). GAGs are classified into six types based on sugar composition, linkage geometry, and position (14). Their interactions with chemokines are mediated by electrostatic forces with positively charged amino acids, as well as hydrogen bonding and Van der Waals interactions (15). Sulfation at multiple positions (2-O, 3-O, 6-O, and N) further contributes to their high negative charge density (16). Chemokine–GAG interactions are essential for presentation, immobilization, and structural activation, but also for chemokine multimerization (e.g., CXCL8, CXCL4, CCL5), which enhances stability (17). CXCL8 is immobilized on GAGs and becomes thus locally concentrated and protected from sequestration and degradation. In this way, CXCL8 is immobilized and protected from degradation, allowing it to form molecular guideposts that direct neutrophil transmigration across the endothelium into inflamed tissues (7, 18, 19). While this process is critical for resolving infection, its dysregulation contributes to persistent or chronic inflammation.

Consistent with its functions, CXCL8 is a key modulator of leukocyte migration and angiogenesis in numerous pathological settings, including cancer, infectious diseases, pulmonary disorders, multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and other inflammatory conditions (9, 20–22). As a potent neutrophil chemoattractant, CXCL8 plays a central role in directing neutrophils rapidly to sites of infection and inflammation.

Given its pathological importance, CXCL8 has been targeted for therapeutic intervention. A dominant-negative CXCL8 mutant (dnCXCL8 = CXCL8 [Δ6 F17K F21K E70K N71K]) was engineered to completely inactivate GPCR-mediated signaling – by deleting the six N-terminal amino acids containing the ELR motif – while enhancing GAG binding affinity through specific amino acid substitutions in the GAG-binding domain (21, 23). As a result, dnCXCL8 can displace wild-type CXCL8 from endothelial GAG surfaces without activating neutrophils in the bloodstream (24). This approach has demonstrated potent anti-inflammatory effects by preventing neutrophil infiltration into chronically inflamed tissues. The anti-inflammatory and anti-migratory properties of dnCXCL8 have been validated in multiple in vivo models of acute and chronic inflammation, including models of cystic fibrosis (25, 26).

However, for biopharmaceuticals such as dnCXCL8, the intrinsic immunogenicity is a critical parameter that can influence both therapeutic efficacy and patient safety (27). After several fatal events, immunogenic assessment has become increasingly important. For example, a formulation change in erythropoietin alpha (Eprex®) provoked a severe immunological response, leading to pure red cell anaplasia in 250 patients with chronic renal failure. And even more severely, when in the TGN1412 (CD28-SuperMAB) trial a cytokine storm induction led to life-threatening events (28–31).

Based on these considerations, we investigated the potential of amino acid substitutions in dnCXCL8 to generate novel T-cell epitopes, thereby potentially altering its immunogenic profile compared to the wild-type protein. Since the display of drug-derived epitopes on MHC class II molecules of antigen-presenting cells is a prerequisite for initiating an immune response (30), we first employed an in silico prediction approach to identify potential CD4+ T-cell epitopes (32) in dnCXCL8 relative to wild-type CXCL8. The top-scoring predicted epitopes, together with the full-length proteins, were subsequently tested in vitro to determine their ability to elicit CD4+ T-cell responses through engagement of T-cell receptors (TCRs).

2 Materials and methods

This is a pure in silico and in vitro study, no animal experiments were undertaken.

2.1 In silico T-cell epitope profiling

The Epibase® platform was used to predict and to screen for T-cell epitopes. This structure-based approach was capable of predicting peptide-MHC II interactions from various HLA allotypes of individuals of European, East Asian, Hispanic, and African American ancestry (33). The sequences of CXCL8 (Uni Prot ID P10145) and dnCXCL8 (Table 1) were scanned for the presence of putative HLA class II-restricted epitopes (T helper - epitopes) using the Epibase® T-cell epitope profiling platform. With this platform, the HLA binding specificities of all possible 15-mers derived from the target sequences were analyzed. Profiling was done at the allotype level for 48 HLA class II receptors, namely 20 DRB1, 7 DRB3/4/5, 14 DQ, and 7 DP receptors (see Supplementary Data 1). The Epibase® platform calculated a quantitative estimate of the free energy of binding ΔGbind of a peptide for each of the 48 HLA class II receptors. The free energies were then converted into dissociation constant (Kd) values through ΔGbind= RT ln(Kd). Peptides were classified as strong binders (Kd < 0.1µM), medium binders (0.1µM < Kd < 0.8µM) and non-binders (0.8µM < Kd) (33, 34).

Table 1. Amino acid sequences of wtCXCL8, dnCXCL8 (Δ6 F17K F21K E70K N71K), and CXCL8 derived peptides.

2.2 Proteins and peptides

CXCL8 and dnCXCL8 (Δ6, F17K F21K E70K N71K) were expressed in E.coli BL21 (Star™ DE3) and purified in three chromatographic steps: cation-exchange chromatography, reverse-phase C18 high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC), and a second cation-exchange step (23). The purified proteins were subsequently formulated by dialysis against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Endotoxin levels were determined using the Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) assay and complied with internal quality requirements of <0.06 EU/mL per batch. All peptides were custom-synthesized by Thermo Scientific at a purity level of >95 percent and delivered as trifluoroacetate (TFA) salts, representing the supplier’s standard formulation. Peptides (AP64, AP65, AP66, AP67, AP 68, AP69) were dissolved in DMSO, and all proteins/peptides were used at a 2.5 µg/ml concentration (corresponding to ~1.1–1.3 µM, depending on sequence-specific molecular weight). TFA at such high dilutions was not expected to raise any immunogenic-like effect. The amino acid sequences of all proteins and peptides are depicted in Table 1. The control peptides Tetanus toxoid (TT) were ordered from Statens Serum Institute and Keyhole Limpet Hemocyanin (KLH) from Calbiochem and used at 10 µg/mL concentration. AP3 (Kabat IGHG1), AP9 (Kabat IGHG1*011 CH2), AP70 (Pan DR sequence) were used at 2 µM and CEFT MHC II peptide mix at 1 µg/mL. Sequences of these peptides are depicted in Table 2.

2.3 PBMC preparation and stimulation

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were freshly prepared from whole blood obtained from healthy donors who had volunteered and provided informed consent. All blood donations were performed anonymously. Donors were screened according to internal criteria; however, no information regarding age, sex, or further demographics is available. Donor recruitment, informed consent, and ethical approval for the use of blood samples were managed by Algonomics in accordance with applicable regulatory standards (“No ethical approval is necessary as the study material is anonymous and voluntarily provided.” according to the Declaration of Helsinki). PBMCs were prepared from whole blood of healthy donors within 6 hours after withdrawal using Ficoll density-gradient centrifugation. The cells were cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen until use. A short-term polyclonal T-cell activation assay using anti-CD3 (0.03 μg/mL) was used to assess the quality of PBMC preparation. The Innogenetics InnoLIPA (Fujirebio Europe) HLA typing kit was used to determine DRB1 HLA allotypes at the 2-digit level for all donors. CD14+ cells were selected using the magnetic separation technique.

PBMCs were thawed and seeded at 1–3 × 105 cells per well in AIM-V medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with IFN-γ (100 IU/mL) in round-bottom 96-well plates. After a 3 h incubation at 37 °C, antigen solutions were added (six donors per run). Cells were incubated for 7 days in a CO2 incubator at 37 °C. For re-stimulation a total of 1–4 × 104 CD14+ cells were added per well together with fresh IFN-γ solution. Antigen solutions were re-applied after 3 h incubation at 37 °C. Two days after re-stimulation, cells were stained and analyzed on a FACS Canto II cytometer equipped with a High Throughput Sampler (HTS).

2.4 FACS analysis

Cell surface markers were stained using anti-CD3-APC-H7 (BD Biosciences), anti-CD4-Alexa488 (BD Biosciences), and 7-AAD (PerCP, BD Biosciences) for the selection of viable CD3+CD4+ cells. To evaluate activation, anti-CD25-PE (Miltenyi Biotec) and anti-CD137-APC (BD Biosciences) were used. All samples were analyzed on a FACS Canto II cytometer (BD Biosciences) equipped with a High Throughput Sampler (HTS).

Gating was performed in the first selection of CD3+CD4+ cells, and then the activated CD3+CD4+ cells were further selected for CD25+ or CD137 +. The latter cell population is used to set the threshold on the CD25 fluorescence that correlates with the activated status of the cells. The number of activated lymphocytes per well was calculated, normalizing the cell count to the number of beads added to each well. For each donor, three 96-well plates were processed. Each plate contained one blank control, 2–4 antigen conditions measured in 10 replicates, and two control antigens measured in 5 replicates. KLH was tested at 10 µg/mL. Sequence-related peptides were evaluated on the same plate.

2.5 Assessment of the immunogenicity profile

The comparison of T-cell activation in antigen-treated wells to untreated reference wells was used to assess intrinsic immunogenicity responses to an antigen. As the full-length protein usually has numerous epitopes, there’s a good chance to find an antigen-specific precursor T-cell in each of the 10-plicate analysis’ wells. As a result, for comparison of protein-treated wells to untreated wells, mean values of activated cells/well over 10-plicate wells (technical replicates) have been employed, resulting in a so-called stimulation index (SI). While the SI for whole-protein stimulation was assumed to follow a normal distribution - because multiple epitopes increase the likelihood of consistent responses across replicate wells - the responses to individual peptides were not assumed to be normally distributed, as peptide-specific precursor T cells are rare and replicate wells may contain either background or true stimulation values. A threshold value was set on the SI-value based on the stimulation index and the variation between replicates to determine if a donor/protein combination was positive or negative. Thus, the number of activated CD3+CD4+ T-lymphocytes in antigen-treated versus untreated wells was compared using SI-values.

Furthermore, comparing mutant protein-treated to wild-type protein-treated wells yields relative responses (RR), showing that both protein variations are immunogenic in a similar way. Positive control peptides of protein-induced immunogenicity, TT, and KLH were measured in 10-plicates to qualify the assay and statistical data interpretation. Peptide-mediated T-cell activation assays were qualified by the negative controls of a non-binding peptide AP3, and a predicted strong and promiscuous binding “self” peptide (germline IgG1) AP9. As positive controls, a mix of “recall” peptides from influenza, tetanus, and EBV (CEFT class II) and a “non-self” Pan DR sequence AP70 were incorporated in the peptide assay.

Standard statistical error tools were used (95% confidence interval) on the Δ-values between the mean values of the log (absolute numbers), which is related to the ratio (SI) of the absolute numbers. An identical procedure was used to calculate relative responses of mutant variants compared with wild-type proteins.

2.6 Statistical analysis

For each donor/protein combination, SI-values, 95% confidence intervals, and p-values were calculated. An antigen was assumed inducing an immunogenic response when the SI is ≥ 1.5. The criterion SI ≥1.5 supported by a p-value ≤0.05 to be listed as positive. Alternatively, significant decreases of immunogenic responses were considered when the SI value was ≤0.66, also supported by a p-value ≤0.05.

While the stimulation index (SI) for whole-protein stimulation was assumed to follow a normal distribution, the response to individual peptides was not. Depending on the underlying precursor frequencies, data from the 10-plicates of peptide-induced T-cell activation studies were not necessarily normally distributed, meaning some values were within the range of background, whereas others show stimulation. To address this, individual wells were classified as activated or not, and the frequency of positive wells was used for further statistical analysis. Linear discriminant analysis was performed to classify the status of each well automatically. This approach explored the discriminating power of each of the continuous variables separately and identified a set of response variables that showed a better discriminating power than each of the single variables. The list of variable parameters used in the automated classification tool was depicted in Supplementary Data 2.

To identify responsive donors for peptides, a pairwise comparison of proportions (Fisher’s Exact test) was performed for treatment and the untreated condition. Because peptide-specific precursor T cells are rare and responses may be sporadic across replicate wells, a less stringent threshold of p < 0.1 was applied in this exploratory screening assay to minimize false negatives. A donor was considered responsive when the frequency of the peptide treated condition was different from the untreated condition with a p-value <0.1.

At the population level, peptide-induced immunogenicity was analyzed using a linear mixed model with a fixed part (differences between conditions) and a random part accounting for donor and plate effects. Peptide averages were estimated in the presence of random effects for donor and plate, and all estimates of the peptide’s effects were computed within plate and donor. This statistical analysis allowed an assessment of the impact of the peptide treatments on the mean frequency of activated wells at the population level over all donors.

To evaluate the relative immunogenicity of mutant peptides compared with their wild-type counterparts, the wild-type peptide condition was taken as a reference level. This enabled investigation of the impact of site-specific mutations on peptide immunogenicity. The applied criteria correctly ranked the positive and negative control peptides and confirmed the expected frequency of positive donors for the control peptides.

3 Results

3.1 In silico screening

Only peptides that bind with a sufficiently high affinity to HLA class II receptors can be presented on the cell surface to initiate a T-helper (TH) response (30, 35). Therefore, determining peptides within a protein sequence that has a strong affinity for HLA class II receptors was the first step in assessing the immunogenic potential of CXCL8 and dnCXCL8. This was done using the Epibase® platform, which is based on a structure-based method taking into account the 3D structure of the binding groove of the HLA II molecules. DRA/DRB1 was in the primary focus of immunogenicity profiling, as its expression level is the highest (33, 34, 36).

Our in silico screening showed that both analyzed proteins contained moderate amounts of TH epitopes specific for a significant part of the population. These epitopes were located in two allocated clusters of the two molecules. The results provided the first prediction of potential immunogenic epitopes based on the primary amino acid sequence of these proteins. This suggests that some of these epitopes might be immunogenic upon high dosing or repeated administration of the proteins. However, factors such as formulation of the product, aggregation, or post-translational modifications could not be considered in this in silico approach. Therefore, peptides for in vitro T-cell activation studies were designed based on the results obtained from the in silico study (Table 3) and were then investigated in more detail in vitro.

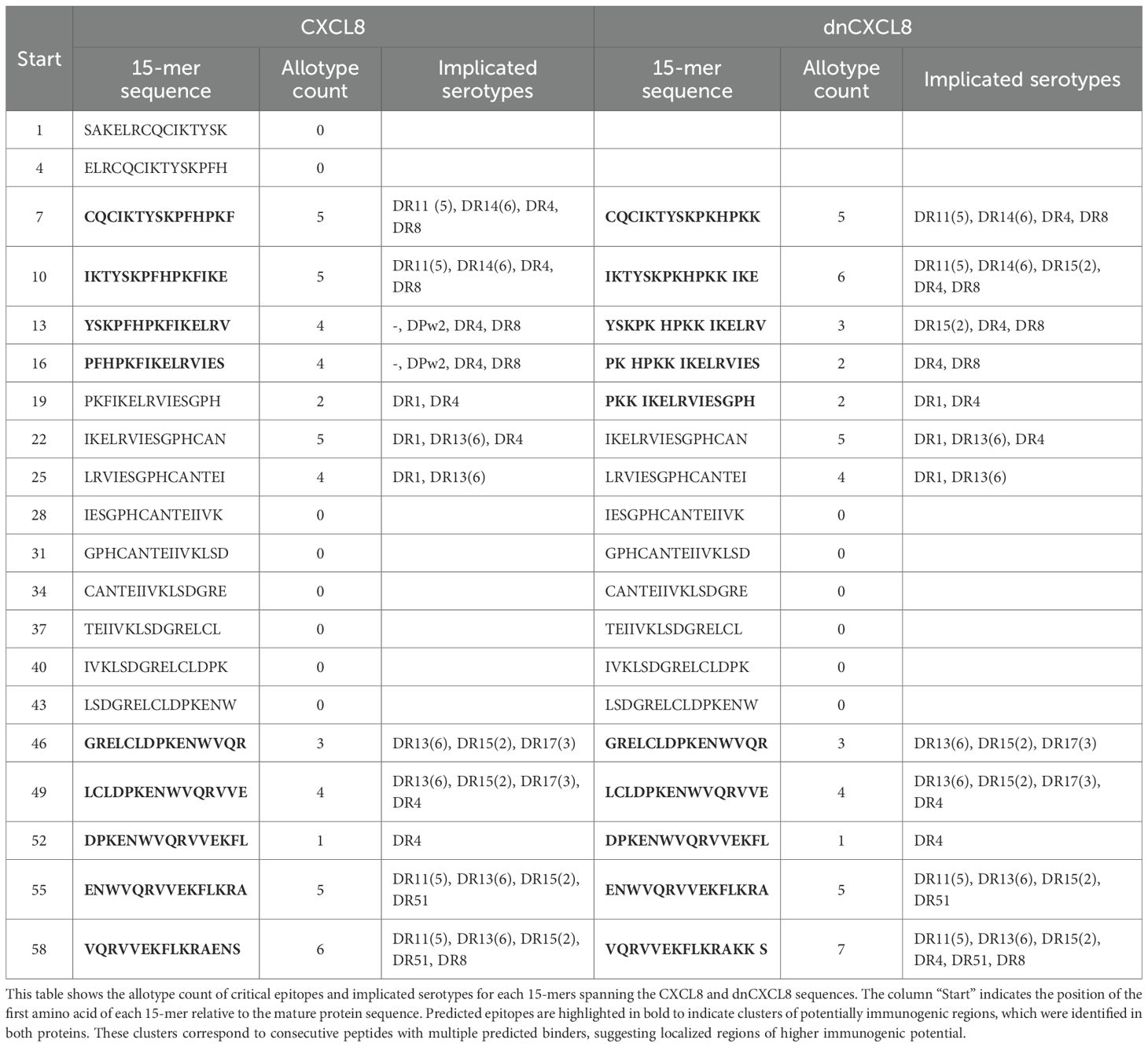

The summary of the in silico TH profiling of CXCL8 and dnCXCL8 is displayed in Table 3. The majority of binders were found for DRB1, which is in accordance with experimental evidence that allotypes belonging to the DRB1 are more potent peptide binders (37). CXCL8 contains 5 strong DRB1 binders, whereas dnCXCL8 contains 4 strong DRB1 binders. No promiscuity in strong DRB1 binders was observed. In addition, 9 medium-strength DRB1 binders were found within the CXCL8 sequence and 13 such peptides within dnCXCL8. CXCL8 contains 1 strong binder for DRB3/4/5, 1 for DP, and none for DQ. Respectively 2, 6, and 3 medium binders to DRB3/4/5, DQ, and DP were found. dnCXCL8 contains 3 strong binders for DRB3/4/5 and none for DP or DQR. Respectively 3, 5, and 2 medium binders to DRB3/4/5, DQ, and DP were found (Table 3). The allotype with the highest apparent immunogenic risk for CXCL8 was DRB1*0402 with 2 strong binders; the one for dnCXCL8 is DRB5*0101 with 3 strong binders (Supplementary Data 3). In both proteins, the potentially immunogenic epitopes were not distributed randomly but were concentrated in two discrete clusters along the amino acid sequence (Table 4).

In both proteins, the predicted immunogenic epitopes were not evenly distributed but instead concentrated in two discrete regions of the sequence. The first cluster was located in the N-terminal region, spanning residues 7–22, where consecutive 15-mers showed binding to multiple HLA class II serotypes (4–6 implicated serotypes each in both CXCL8 and dnCXCL8). The second cluster was located in the C-terminal region, spanning residues 49–58, again comprising consecutive peptides with high allotype counts (4–7 implicated serotypes). These clusters represent localized hot-spots of potential immunogenicity (Table 4 and Supplementary Data 3).

3.2 Protein in vitro immunogenicity

Protein in vitro immunogenicity responses were defined as an increase in the average number of activated (CD25 high) CD4+ cells per well for antigen-treated wells compared to untreated blank wells (contrast), expressed as stimulation index (SI). The SI-value with 95% confidence interval and p-value (SI = 1) was calculated for each antigen or reference. The results for the control antigens KLH and TT, as well as for CXCL8 and dnCXCL8, are summarized in Table 5, with the complete dataset including 95% CI available in Supplementary Data 4, 5.

An immunogenic response is defined as SI≥1.5 supported by a p-value (SI = 1) ≤0.05, whereas a significant reduction is defined as SI value ≤0.66 supported by a p-value (SI = 1) ≤0.05. The defined threshold was set to RR > 1,5 supported by p-value (RR = 1) ≤0.05 or RR<0.66 supported by p-value (RR = 1) <0.05 with the inclusion that at least for 1 of the proteins a significant enhanced or reduced SI for that donor was observed. RRs were calculated for each donor/contrast combination to compare mutant dnCXCL8 with wild-type CXCL8. For each RR value, 95% confidence intervals and p-values (RR = 1) were determined. This analysis indicates whether the immunogenic responses elicited by the mutant protein differ significantly from those of the wild-type. The results are summarized in Table 6, where a mean RR = 1 reflects similar immunogenicity of dnCXCL8 and CXCL8.

Table 6. The relative immunogenicity table indicates the relative responses of dnCXCL8 with wtCXCL8 per donor.

To exclude endotoxin-related artifacts, all recombinant protein batches were tested for endotoxin content using the Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) assay, with values confirmed to be below of an internal acceptance criterion of 0.06 EU/mL per batch.

Figure 1 summarizes the mean immunogenicity responses (SI) in a 51-donor population for all tested samples. TT and KLH, which both served as positive control antigens, showed an evident 71% and 80% immunogenic potency. Both antigens showed a clear shift in a frequency distribution, which was consistent with the single donor level. The mean SI of KLH was 2.1, and of TT 4.13 in the population, both with p-values (SI = 1) less than 0.0001 (Figure 1). The mean relative immunogenicity responses for all 51 donors could be determined by comparing the population level immunogenicity of dnCXCL8 to CXCL8. Figure 1 shows the mean RR values for protein variations and the associated p-value (RR = 1). The relative immunogenicity responses of KLH, TT, CXCL8, and dnCXCL8 compared to Blank, observed in all donors, is depicted in Supplementary Data 6-9. When assessing the whole donor SI distribution, the protein-mediated immunogenicity assays’ findings showed that all proteins are significantly immunogenic (p<0.05).

Figure 1. Mean intrinsic immunogenicity data for CXCL8 and dnCXCL8 compared to control antigens in a 51-donor population. Left: Bar graph representation of the mean stimulation index (SI) for Keyhole Limpet Hemocyanin (KLH), Tetanus Toxoid (TT), CXCL8, and dnCXCL8, together with the percentage of responsive donors (RD). Right: Tabular representation of mean SI values and corresponding p-values for the same antigens.

At the population level, dnCXCL8 displayed slightly higher immunogenicity than wild-type CXCL8, with mean SI values of 1.58 and 1.44, respectively. An increased number of responsive donors was obtained there, with 12 of the 14 CXCL8 responsive donors being positive for dnCXCL8. In ten of these donors, the response to the mutant protein was the same as it was to the wild-type protein. This suggests that T-cell activation in these donors was likely driven by epitopes present in the common regions of both proteins. In 9 donors, the mutant proteins had significantly higher relative responses than the wild-type proteins (RR>1.5 and p-value (RR = 1)<0.05), with only one of these donors being also responsive to CXCL8. But this difference in immunogenicity was not significantly different between dnCXCL8 and CXCL8. Donors with common characteristics may be more predisposed to respond significantly different to both proteins. Three donors showed a reduction in immunogenic response for dnCXCL8 compared to CXCL8. Only one donor sample, labeled as AIV00084, showed a significant decrease in T-cell activation, visible as reduced SI value. Still, in this sample, none of the control peptides induced a significant immunogenic response. Relative responses (RR) are calculated by comparison of the mean number of activated, CD25 high, CD4+ lymphocytes/well in CXCL8 versus dnCXCL8 samples for each donor. These RR values are summarized in Table 6, where a mean RR of 1 reflects comparable immunogenicity of mutant and wild-type proteins.

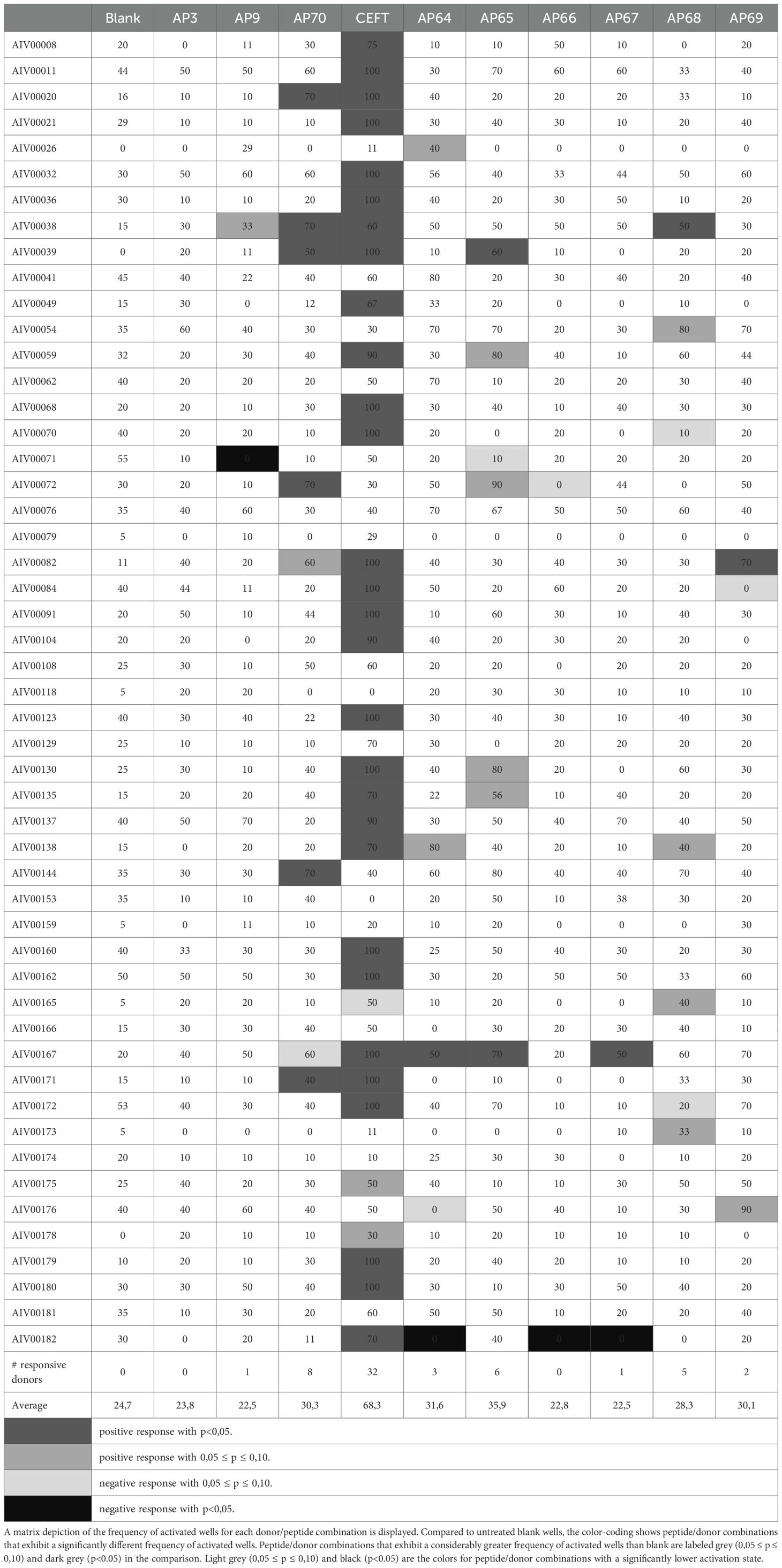

3.3 The peptides’ in vitro immunogenicity

Pairwise comparison of proportions of frequency of activated wells in the peptide-treated condition and the untreated condition was performed (Table 5). The untreated control (blank) depicted greater values than 0, which is attributed to donor-dependent random, non-specific activation in the absence of exogenous antigen that is presented to the T-cells. When compared to “untreated” activation, there was a lower overall activation level in the presence of peptides in the assay. In most cases, the decrease in frequency is not statistically significant, however for some peptide/donor combinations, the negative difference (decrease) in frequency is statistically significant with p<0.1 or even p<0.05. This categorization into responsive and non-responsive donors rejects borderline responses. A graphical representation of the range of activation frequencies across donors is provided in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The frequency of activated wells for control peptides in a 51-donor population. Box-and-whisker plots showing the frequency of activated wells (%) for blank, control peptides (AP3, AP9, AP70, CEFT), and CXCL8/dnCXCL8-derived peptides (AP64–AP69). Median, interquartile range, and full range of values are displayed. The p-values shown above the plots indicate the statistical comparison between peptide-treated and untreated (blank) conditions.

The negative control peptides AP3 and AP9 induced minimal responses, with <2% of donors responding. The positive control peptides showed higher responsiveness: AP70 (Pan-DR) induced activation in ~16% of donors, while the CEFT peptide pool triggered responses in >60% of donors.

Strong immunogenic responses at the population level were detected for 1 of the 3 CXCL8-derived self-peptides, which corresponded to the significant immunogenicity observed for CXCL8. Even though the number of responsive donors was less than 6%, there is a considerable rise in the average frequency of activated wells in the population, indicating the contribution of donor samples with immunogenic reactions at the detection threshold. Although the wild-type based peptide AP68 induced responses in almost 10% of donors, the amplitude of the response was not drastically affecting the average frequency of activated wells in the total population (Table 6). The average frequency of activated wells was stronger for the non-self-peptides from dnCXCL8 compared to CXCL8. AP65 showed the highest immunogenic potency with almost 12% of positive donors. This peptide was found in the same N-terminal region as AP64 but with the two phenylalanine to lysine alterations present only in dnCXCL8. However, comparing the relative immunogenicity of AP65 and AP64 at the population level showed no substantial difference between the two peptides.

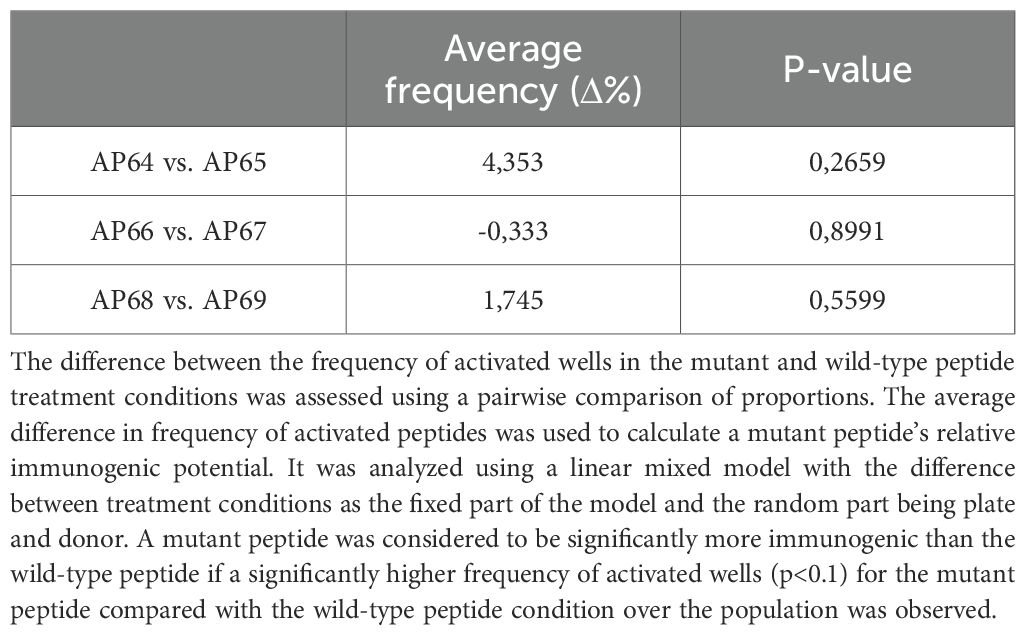

Furthermore, no significantly different immunogenicity was observed between mutated peptides derived from dnCXCL8 and their wild-type counterparts on the population level. For the peptides AP66 and AP67, only a limited number of donors showed a statistically significant decrease. However, other donor samples contributed to the negative difference in average frequency at the population level, resulting in this overall lower activation status (respectively 7 and 11 donors, a decrease of percent activated wells of more than 20 percent was observed). However, this diminished immunogenic response could not be classified as significant at the population level (Table 7). The observation was similar to the effect of the negative control peptide AP9.

The frequency of peptide-induced T-cell activation across donors was further analyzed. Several peptides elicited significantly higher activation frequencies compared with blank conditions (p < 0.1) and were therefore classified as immunogenic (Table 8). These results complement the stimulation index data by identifying specific peptide sequences that contributed most strongly to the observed immunogenic responses.

To compare dnCXCL8 and wild-type CXCL8 directly, relative peptide responses were calculated on a donor-by-donor basis. Most peptides exhibited similar activation frequencies between the two proteins, while selected peptides displayed modest differences in immunogenic potential (Table 9). These relative comparisons provide additional evidence for the largely comparable immunogenicity profiles of dnCXCL8 and CXCL8.

Table 9. The relative immunogenicity of three pairs of peptides was assessed using flow cytometry in a 51 healthy donor samples.

4 Discussion

Intrinsic immunogenicity is a critical parameter that directly impacts the therapeutic efficacy and safety of biopharmaceuticals. In this study, we investigated the immunogenic potential of a chemokine-based dominant-negative mutant, dnCXCL8, in comparison to its wild-type counterpart CXCL8, using both full-length proteins and peptide-derived epitopes. A panel of positive and negative control proteins and peptides, including Keyhole Limpet Hemocyanin (KLH), Tetanus toxoid (TT), AP3, AP9, CEFT, and AP70, confirmed the validity of the experimental approach and provided reference for interpretation of the responses.

4.1 Protein immunogenicity

Both CXCL8 and dnCXCL8 elicited measurable T-cell activation in vitro. While dnCXCL8 tended to induce slightly stronger responses than wild-type CXCL8, this difference was not statistically significant at the population level. This suggests that dnCXCL8 does not possess an intrinsically higher immunogenic potential compared with its progenitor molecule.

The detection of immunogenic responses against wild-type CXCL8 may initially appear unexpected, as tolerance to self-proteins would normally be anticipated. However, this finding is consistent with reports of anti-chemokine autoantibodies in healthy individuals, including antibodies against CXCL8, IL-1, IL-2, TNFα, IFNγ, IL-6, and CCL2 (38, 39). These autoantibodies may circulate as immune complexes or as free immunoglobulins (IgG, IgM, IgA), and their concentrations can increase under inflammatory conditions such as gastritis or rheumatoid arthritis (40, 41). Moreover, the assay conditions employed here differ from physiological settings, as supraphysiological protein concentrations (µM range vs. nM–pM in vivo) were used, which may amplify detectable responses (5). Additional factors such as protein purity, formulation, aggregation, and glycosylation status could also contribute to the observed immunogenicity (42). Taken together, these considerations provide a rationale for why immunogenic responses were observed even for wild-type CXCL8.

4.2 Peptide immunogenicity

At the peptide level, only two epitopes (AP64 and AP65) reached significance at the population level. These two peptides share the same sequence but are derived from CXCL8 and dnCXCL8, respectively. AP65, which incorporates the F17K/F21K substitutions, showed the strongest response, suggesting that the lysine substitutions may influence peptide–HLA binding affinity (34). Nevertheless, the difference in relative immunogenicity between AP65 and AP64 was not statistically significant. Interestingly, the relative donor-level differences between CXCL8 and dnCXCL8 proteins were not always mirrored at the peptide level. This discrepancy may reflect differences in antigen processing: intact proteins are subject to endosomal processing, generating a broad repertoire of epitopes, while synthetic peptides present only predefined sequences. Additionally, some protein regions not represented in the peptide panel may contribute to the higher overall donor reactivity observed for full-length proteins, despite their lower molar concentrations compared to peptides (43).

4.3 Mechanistic considerations

The modest increase in immunogenicity observed for AP65 could be mechanistically explained by the introduction of positively charged lysine residues at positions 17 and 21. These substitutions may alter peptide–MHC interactions, modify local protein solubility, or impact glycosaminoglycan (GAG) binding and multimerization, thereby indirectly affecting antigen presentation (44, 45). Further studies such as HLA-binding assays or structural modeling will be required to delineate these mechanisms.

4.4 Clinical relevance

From a translational perspective, the observation that dnCXCL8 does not display significantly increased immunogenicity compared to wild-type CXCL8 is encouraging. For biologics intended for chronic administration, even small increases in immunogenicity can be of concern. Our data indicate that dnCXCL8 maintains an immunogenic profile comparable to CXCL8, supporting its continued development as a therapeutic candidate. The broader finding that chemokines can induce measurable immune responses aligns with the concept that they naturally predispose to humoral autoreactivity. This underscores the importance of monitoring autoantibody and T-cell responses in clinical trials of chemokine-based therapeutics (46).

4.5 Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be mentioned. Recombinant proteins were expressed in E. coli, and even trace amounts of endotoxin can act as strong adjuvants through TLR4 signaling (47). All protein preparations were confirmed by Limulus Amebocyte Lysate (LAL) testing to contain <0.06 EU/mL, in line with internal specifications. Endotoxin contaminations can be avoided if protein expression is accomplished for example in yeast (Pichia Pastoris). In addition to endotoxins, high levels of TFA could influence immune cell activation. And although the manufacturer’s standard specifications were met, we cannot exclude that residual TFA contributed to some of the peptide responses. Finally, for peptide responses, a less stringent statistical threshold (p < 0.1) was applied to reduce false negatives, reflecting the exploratory nature of the assay. While suitable for early-stage screening, confirmatory studies under stricter criteria will be needed to validate these findings.

4.6 Future perspectives

Future work will extend this approach to additional engineered chemokines, which represent a promising novel class of anti-inflammatory biotherapeutics (5, 24). With respect to extending the indication range of our protein engineering approach, we are planning to extend our studies to CCL2 (monocyte/macrophage-mobilizing) and CXCL12 (T-cell/stem-cell mobilizing) dominant-negative mutants. Comparative studies with naturally occurring chemokine isoforms may provide further insights into determinants of immunogenicity. Moreover, mechanistic investigations into how specific amino acid substitutions influence epitope processing, HLA binding, and T-cell recognition will be critical to guide the rational design of safer and more effective chemokine-based therapeutics.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

For donated blood, from which cells were freshly prepared, the Declaration of Helsinki applies: “No ethical approval is necessary as the study material is anonymous and voluntarily provided.” The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

ET: Investigation, Writing – original draft. TG: Investigation, Writing – original draft. PS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Writing – review & editing. CT: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. TA: Investigation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. AK: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. The authors acknowledge the financial support by the University of Graz. Open access funding provided by the University of Graz.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Open Access Funding by the University of Graz.

Conflict of interest

PS is employed by Algonomics. TA is advisor of Antagonis. AK is founder and shareholder of Antagonis.

The remaining author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2025.1679409/full#supplementary-material

Glossary

APC: Antigen-presenting cell

CEFT: CMV, EBV, Flu, Tetanus peptide mix

CXCL8: C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 8

CXCR1/CXCR2: C-X-C Motif Chemokine Receptor ½

dnCXCL8: Dominant-negative CXCL8 mutant

DRB1: DRB3/4/5, DQ, DP, HLA class II loci

FACS: Fluorescence-activated cell sorting

FSC: Forward scatter

GAG: Glycosaminoglycan

GPCR: G protein–coupled receptor

HLA: Human Leukocyte Antigen

IFNγ: Interferon-gamma

IL-8: Interleukin 8

KLH: Keyhole Limpet Hemocyanin

LAL: Limulus Amebocyte Lysate

MFI: Mean Fluorescence Intensity

MHC: Major Histocompatibility Complex

PBS: Phosphate-buffered saline

PBMC: Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells

RP-HPLC: Reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography

RR: Relative Response

SI: Stimulation Index

SSC: Side scatter

TFA: Trifluoroacetic acid

TH (T-helper): CD4⁺ T-helper cell

TLR4: Toll-like receptor 4

TT: Tetanus Toxoid

wtCXCL8: Wild-type CXCL8

References

1. Bonecchi R, Galliera E, Borroni EM, Corsi MM, Locati M, and Mantovani A. Chemokines and chemokine receptors: an overview. Front Bioscience. (2009) 540–51. doi: 10.2741/3261

2. Zlotnik A YO. Chemokines: A new classification system and their role in immunity. Immunity. (2012) 12:705–16. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80165-x

3. Hughes CE and Nibbs RJ. A guide to chemokines and their receptors. FEBS J. (2018) 285:2944–71. doi: 10.1111/febs.14466

4. Khan MA, Khurana N, Ahmed RS, Umar S, Abu H, and Sarwar. M. Chemokines: A potential therapeutic target to suppress autoimmune arthritis. (2019) 25:2937–46. doi: 10.2174/1381612825666190709205028

5. Metzemaekers M, Vandendriessche S, Berghmans N, Gouwy M, and Proost P. Truncation of CXCL8 to CXCL8(9-77) enhances actin polymerization and in vivo migration of neutrophils. J Leukocyte Biol. (2020) 107:1167–73. doi: 10.1002/JLB.3AB0220-470R

6. Frevert CW, Kinsella MG, Vathanaprida C, Goodman RB, Baskin DG, Proudfoot A, et al. Binding of interleukin-8 to heparan sulfate and chondroitin sulfate in lung tissue. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. (2003) 28:464–72. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0084OC

7. Handel TM and Dyer DP. Perspectives on the biological role of chemokine: glycosaminoglycan interactions. J Histochem Cytochem. (2021) 69:87–91. doi: 10.1369/0022155420977971

8. Russo RC, Garcia CC, Teixeira MM, and Amaral FA. The CXCL8/IL-8 chemokine family and its receptors in inflammatory diseases. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. (2014) 10:593–619. doi: 10.1586/1744666X.2014.894886

9. Liu Q, Li A, Tian Y, Wu JD, Liu Y, Li T, et al. The CXCL8-CXCR1/2 pathways in cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. (2016) 31:61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2016.08.002

10. Nasser MW, Raghuwanshi SK, Grant DJ, Jala VR, Rajarathnam K, and Richardson RM. Differential activation and regulation of CXCR1 and CXCR2 by CXCL8 monomer and dimer. J Immunol. (2009) 183:3425–32. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900305

11. Samanta AK, Oppenheim JJ, and Matsushima K. Interleukin 8 (monocyte-derived neutrophil chemotactic factor) dynamically regulates its own receptor expression on human neutrophils. J Biol Chem. (1990) 265:183–9. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)40213-5

12. Balkwill FR. The chemokine system and cancer. J Pathol. (2012) 226:148–57. doi: 10.1002/path.3029

13. Joseph PR, Sawant KV, Iwahara J, Garofalo RP, Desai UR, and Rajarathnam K. Lysines and Arginines play non-redundant roles in mediating chemokine-glycosaminoglycan interactions. Sci Rep. (2018) 8:12289. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-30697-y

14. Rudd TR, Skidmore MA, Guerrini M, Hricovini M, Powell AK, Siligardi G, et al. The conformation and structure of GAGs: recent progress and perspectives. Curr Opin Struct Biol. (2010) 20:567–74. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2010.08.004

15. Ori A, Wilkinson MC, and Fernig DG. A systems biology approach for the investigation of the heparin/heparan sulfate interactome. J Biol Chem. (2011) 286:19892–904. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.228114

16. Lindahl U, Couchman J, Kimata K, and Esko JD. Proteoglycans and sulfated glycosaminoglycans. Essentials Glycobiology. (2017). doi: 10.1101/glycobiology.3e.017

17. Proudfoot AE, Johnson Z, Bonvin P, and Handel TM. Glycosaminoglycan interactions with chemokines add complexity to a complex system. Pharm (Basel). (2017) 10:70. doi: 10.3390/ph10030070

18. Gschwandtner M, Strutzmann E, Teixeira MM, Anders HJ, Diedrichs-Möhring M, Gerlza T, et al. Glycosaminoglycans are important mediators of neutrophilic inflammation in vivo. Cytokine. (2017) 91:65–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2016.12.008

19. von Hundelshausen P, Agten SM, Eckardt V, Blanchet X, Schmitt MM, Ippel H, et al. Chemokine interactome mapping enables tailored intervention in acute and chronic inflammation. Sci Transl Med. (2017) 10:70. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aah6650

20. Deshmane SL, Kremlev S, Amini S, and Sawaya BE. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1): an overview. J Interferon Cytokine Res. (2009) 29:313–26. doi: 10.1089/jir.2008.0027

21. Adage T, Del Bene F, Fiorentini F, Doornbos RP, Zankl C, Bartley MR, et al. PA401, a novel CXCL8-based biologic therapeutic with increased glycosaminoglycan binding, reduces bronchoalveolar lavage neutrophils and systemic inflammatory markers in a murine model of LPS-induced lung inflammation. Cytokine. (2015) 76:433–41. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2015.08.006

22. Falsone A, Wabitsch V, Geretti E, Potzinger H, Gerlza T, Robinson J, et al. Designing CXCL8-based decoy proteins with strong anti-inflammatory activity in vivo. Biosci Rep. (2013) 33:e00068. doi: 10.1042/BSR20130069

23. Piccinini AM, Knebl K, Rek A, Wildner G, Diedrichs-Möhring M, and Kungl AJ. Rationally evolving MCP-1/CCL2 into a decoy protein with potent anti-inflammatory activity in vivo. J Biol Chem. (2010) 285:8782–92. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.043299

24. Adage T, Konya V, Weber C, Strutzmann E, Fuchs T, Zankl C, et al. Targeting glycosaminoglycans in the lung by an engineered CXCL8 as a novel therapeutic approach to lung inflammation. Eur J Pharmacol. (2015) 748:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.12.019

25. McElvaney OJ, O’Reilly N, White M, Lacey N, Pohl K, Gerlza T, et al. The effect of the decoy molecule PA401 on CXCL8 levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with cystic fibrosis. Mol Immunol. (2015) 63:550–8. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2014.10.013

26. Brinks V, Weinbuch D, Baker M, Dean Y, Stas P, Kostense S, et al. Preclinical models used for immunogenicity prediction of therapeutic proteins. Pharm Res. (2013) 30:1719–28. doi: 10.1007/s11095-013-1062-z

27. McKoy JM, Stonecash RE, Cournoyer D, Rossert J, Nissenson AR, Raisch DW, et al. Epoetin-associated pure red cell aplasia: past, present, and future considerations. Transfusion. (2008) 48:1754–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01749.x

28. Attarwala H. TGN1412: from discovery to disaster. J Young Pharm. (2010) 2:332–6. doi: 10.4103/0975-1483.66810

29. Suntharalingam G, Perry MR, Ward S, Brett SJ, Castello-Cortes A, Brunner MD, et al. Cytokine storm in a phase 1 trial of the anti-CD28 monoclonal antibody TGN1412. (2006) 355:1018–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063842

30. Weaver JM, Lazarski CA, Richards KA, Chaves FA, Jenks SA, Menges PR, et al. Immunodominance of CD4 T cells to foreign antigens is peptide intrinsic and independent of molecular context: Implications for vaccine design. J Immunol. (2008) 3039:3039–48. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3039

31. Sabine L. Lessons from Eprex for biogeneric firms. Nat Biotechnol. (2003) 21:956–8. doi: 10.1038/nbt0903-956

32. Stas P and Lasters I. Immunogénicité de protéines d’intérêt thérapeutique les anticorps monoclonaux thérapeutiques. Med Sci (Paris). (2009) 25:1070–7. doi: 10.1051/medsci/200925121070

33. Desmet IL J. Method for predicting the binding affinity of mhc/peptide complexes. Google Patents. (2004).

34. Desmet J, Meersseman G, Boutonnet N, Pletinckx J, De Clercq K, Debulpaep M, et al. Anchor profiles of HLA-specific peptides: Analysis by a novel affinity scoring method and experimental validation. PROTEINS: Structure Function Bioinf. (2005) 58:53–69. doi: 10.1002/prot.20302

35. Alexander J, Sidney J, Southwood S, Ruppert J, Oseroff C, Maewal A, et al. Development of high potency universal DR-restricted helper epitopes by modification of high affinity DR-blocking peptides. Immunity. (1994) 1:751–61. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(94)80017-0

36. Desmet J, Wilson I, Joniau M, De Maeyer M, and Lasters I. Computation of the binding of fully flexible peptides to proteins with flexible side chains. FASEB J. (1997) 11:164–72. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.11.2.9039959

37. Kilian M, Sheinin R, Tan CL, Friedrich M, Krämer C, Kaminitz A, et al. MHC class II-restricted antigen presentation is required to prevent dysfunction of cytotoxic T cells by blood-borne myeloids in brain tumors. Cancer Cell. (2023) 41:235–251.e9. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2022.12.007

38. Watanabe M, Uchida K, Nakagaki K, Trapnell BC, and Nakata K. High avidity cytokine autoantibodies in health and disease: pathogenesis and mechanisms. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. (2010) 21:263–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2010.03.003

39. Watanabe M, Uchida K, Nakagaki K, Kanazawa H, Trapnell BC, Hoshino Y, et al. Anti-cytokine autoantibodies are ubiquitous in healthy individuals. FEBS Lett. (2007) 581:2017–21. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.029

40. Peichl P, Pursch E, Bröll H, and Lindley IJ. Anti-IL-8 autoantibodies and complexes in rheumatoid arthritis: polyclonal activation in chronic synovial tissue inflammation. Rheumatol Int. (1999) 18:141–5. doi: 10.1007/s002960050073

41. Crabtree JE, Peichl P, Wyatt JI, Stachl U, and Lindley IJ. Gastric interleukin-8 and IgA IL-8 autoantibodies in Helicobacter pylori infection. Scand J Immunol. (1993) 37:65–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1993.tb01666.x

42. Jawa V, Cousens LP, Awwad M, Wakshull E, Kropshofer H, and Groot AS. T-cell dependent immunogenicity of protein therapeutics: Preclinical assessment and mitigation. Clin Immunol. (2013) 149:534–55. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2013.09.006

43. Molero-Abraham M, Lafuente EM, and Reche P. Customized predictions of peptide–MHC binding and T-cell epitopes using EPIMHC. New York: Humana Press (2014). p. 586.

44. Kuschert GS, Coulin F, Power CA, Proudfoot AE, Hubbard RE, Hoogewerf AJ, et al. Glycosaminoglycans interact selectively with chemokines and modulate receptor binding and cellular responses. Biochemistry. (1999) 38:12959–68. doi: 10.1021/bi990711d

45. Southwood S, Sidney J, Kondo A, del Guercio MF, Appella E, Hoffman S, et al. Several common HLA-DR types share largely overlapping peptide binding repertoires. J Immunol. (1998) 160:3363–73. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.160.7.3363

46. Sauerborn M, Brinks V, Jiskoot W, and Schellekens H. Immunological mechanism underlying the immune response to recombinant human protein therapeutics. Trends Pharmacol Sci. (2010) 31:53–9. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.11.001

Keywords: chronic inflammatory, chemokines, CXCL8, glycosaminoglycans, drug candidate, in silico screening, immunogenicity

Citation: Talker E, Gerlza T, Stas P, Trojacher C, Adage T and Kungl AJ (2025) Immunogenicity of a CXCL8-based biopharmaceutical drug candidate in comparison to its wildtype form. Front. Immunol. 16:1679409. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2025.1679409

Received: 04 August 2025; Accepted: 30 November 2025; Revised: 14 November 2025;

Published: 16 December 2025.

Edited by:

Rasheed Ahmad, Dasman Diabetes Institute, KuwaitReviewed by:

Mirja Harms, Ulm University Medical Center, GermanyJustyna Agier, Medical University of Lodz, Poland

Sean P. Giblin, Imperial College London, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2025 Talker, Gerlza, Stas, Trojacher, Adage and Kungl. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Andreas J. Kungl, YW5kcmVhcy5rdW5nbEB1bmktZ3Jhei5hdA==

Elisa Talker

Elisa Talker Tanja Gerlza

Tanja Gerlza Philippe Stas2

Philippe Stas2 Christina Trojacher

Christina Trojacher Andreas J. Kungl

Andreas J. Kungl